Abstract

To address the biochemical mechanisms underlying the coordination between the various proteins required for nucleotide excision repair (NER), we employed the immobilized template system. Using either wild-type or mutated recombinant proteins, we identified the factors involved in the NER process and showed the sequential comings and goings of these factors to the immobilized damaged DNA. Firstly, we found that PCNA and RF-C arrival requires XPF 5′ incision. Moreover, the positioning of RF-C is facilitated by RPA and induces XPF release. Concomitantly, XPG leads to PCNA recruitment and stabilization. Our data strongly suggest that this interaction with XPG protects PCNA and Polδ from the effect of inhibitors such as p21. XPG and RPA are released as soon as Polδ is recruited by the RF-C/PCNA complex. Finally, a ligation system composed of FEN1 and Ligase I can be recruited to fully restore the DNA. In addition, using XP or trichothiodystrophy patient-derived cell extracts, we were able to diagnose the biochemical defect that may prove to be important for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: DNA resynthesis, nucleotide excision repair, XPG

Introduction

Cells have developed different repair mechanisms such as nucleotide excision repair (NER) to maintain the integrity of the DNA, which is exposed to endogenous and exogenous genotoxic attacks (Hoeijmakers, 2001). This repair pathway eliminates the damage induced by UV and by antitumoral chemicals among others. The primary importance of NER is underlined by the existence of autosomal recessive syndromes known as xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) and trichothiodystrophy (TTD) (Kraemer et al, 2007). These syndromes are genetically complex with at least eight complementation groups for XP (XP-A to XP-G and variant) and three for TTD (XP-B, XP-D and TTD-A). The products of the XP genes are proteins involved in the different steps of NER and comprise three damage-recognition proteins, two helicases and two endonucleases (de Laat et al, 1999). Mutations in specific repair factors have been shown to affect genome stability (Lehmann, 2003). The broad range of clinical features as well as the variability in the severity of each phenotype cannot be explained by only a deficiency in DNA repair. Thus, it was demonstrated that some of the NER factors play a role in the DNA replication (Johnson et al, 1999) and transcription processes (Compe et al, 2005; Ito et al, 2007). Furthermore, in the sole context of global genome NER (GG-NER), the relationship between the mutations and the phenotypes displayed by patients is further complicated by the network of interactions between NER factors that can modulate their stability, positioning on the damaged DNA and enzymatic activities. Therefore, it is not surprising that a mutation in a given protein such as in XPB/fs740 will disturb the activity of another one like the XPF endonuclease, which acts in a later step of NER (Araujo et al, 2000; Coin et al, 2004).

Considerable progress has been made in recent years toward determining the function of each of the NER components starting from the recognition of the DNA damage with XPC, to the excision of the damaged oligonucleotide and DNA resynthesis (Aboussekhra et al, 1995; Shivji et al, 1995). However, little is known about the intricate network that regulates the comings and goings of the 11 NER factors onto the damaged DNA template and about the protein/protein interactions that lead to the formation of the various intermediate DNA repair complexes (Araujo and Wood, 1999; Riedl et al, 2003). While the first steps leading to the removal of the DNA damage have been described (Araujo et al, 2000; Volker et al, 2001; Riedl et al, 2003), little is known on the link between the dual incision and the resynthesis (Gillet and Scharer, 2006). How are PCNA, RF-C and DNA polymerase recruited? Do the dual incision factors play a role in the formation of the resynthesis complex? What is the fate of XPG, XPF and RPA?

To obtain a more detailed picture of the NER mechanism, we used an immobilized template. We thus were able to recruit and identify from HeLa nuclear extracts (NE) all the NER factors that participate in the three steps of the NER: dual incision, resynthesis and ligation. Moreover, by using either wild type and mutated recombinant proteins or XP- and TTD-patient-derived cell extracts, we were able to show how the NER factors were sequentially coming on and going off the immobilized damaged DNA in a ‘ballet' similar to what was observed by confocal microscopy in the cell. We also document how a mutation in a single NER factor can disturb the formation of the successive intermediate complexes and their enzymatic activities. Indeed, the understanding of the mechanistic defects leading to the XP or TTD has been beneficial in unravelling the NER reaction and vice versa. From this combined data emerged an unexpected role for XPG, which is as important as RPA in initiating the resynthesis step of the NER.

Results

Sequential arrival of NER factors on local UV-irradiated DNA

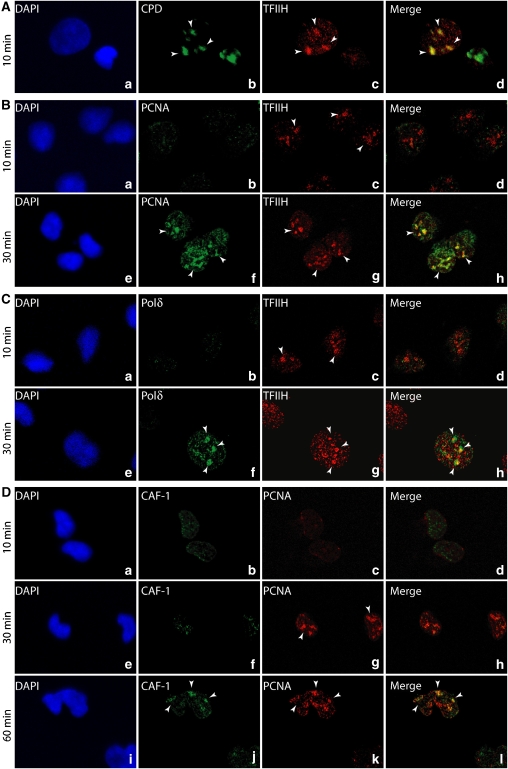

We studied the dynamics of the NER factors in living cells, using local UV irradiation technology combined with fluorescent immunostaining (Volker et al, 2001). Confocal microscopy showed that 10 min post-UV irradiation, TFIIH, one of the first factors to target the damaged DNA (Figure 1A, panels a–d), colocalized with the cyclopyrimidine dimers (CPD) photoproduct (Riedl et al, 2003). At that time, neither PCNA nor the DNA polymerase delta (Polδ), which are involved in DNA resynthesis, was detected (Figure 1B and C, panels a–d). However, 30 min after UV irradiation, both PCNA (Miura, 1999) and Polδ accumulated at the irradiated sites (Figure 1C, panels e–h), supporting the sequential occurrence of the dual incision and the resynthesis. As local UV irradiation generates several hundreds of lesions, as visualized by CPD antibodies, the merging of TFIIH and either PCNA or Polδ signals results from the simultaneous and close presence of damaged DNA complexes at different stages of the repair reaction. At 60 min after UV irradiation, we also observed the arrival of the histone chaperone chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1), which colocalizes with PCNA (Figure 1D). CAF-1 is the key player involved in the dynamics of the nucleosome assembly process at UV-damage sites in vivo (Green and Almouzni, 2003; Polo et al, 2006).

Figure 1.

In vivo sequential recruitment of NER factors. Rescued XPCS2BA human fibroblasts were locally UV irradiated and labelled at 10, 30 and 60 min after UV irradiation with the indicated MAbs or PAbs. Colocalization of (A) CPD and TFIIH (XPB) (panels a–d), (B) TFIIH and PCNA (panels a–h), (C) TFIIH and Polδ (panels a–h) and (D) PCNA and CAF1 (panels a–l). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and pictures were merged.

Sequential arrival of NER factors on immobilized damaged DNA

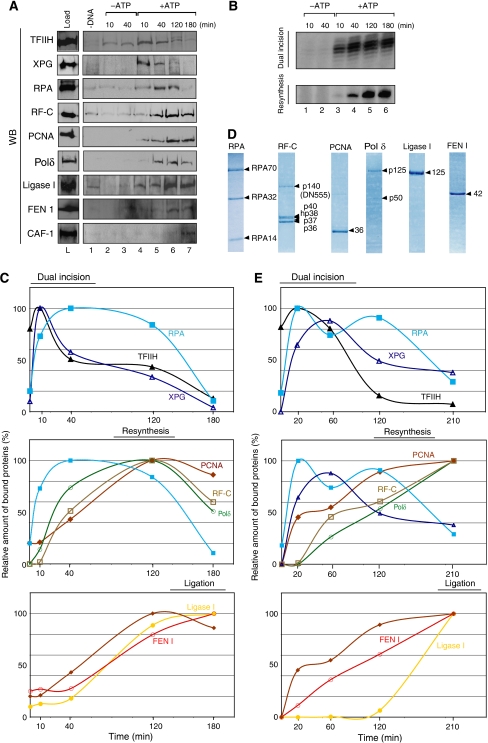

To better understand the transition steps between dual incision and resynthesis and to pinpoint the role of each factor, we followed their kinetics in vitro. The ‘comings and goings' of the NER factors on a DNA template were analysed by incubating NE with an immobilized damaged DNA containing a single 1,3 intrastrand d(GpTpG) cisplatin–DNA crosslink, also called the ‘immobilized template assay' (Lainé et al, 2006). At different time points, the immobilized DNA was washed with 0.05 M KCl and the recruitment of the repair factors was monitored by immunoblotting, while the release of the damaged oligonucleotide and the DNA resynthesis activity were analysed by autoradiography (Figure 2A and B; Supplementary data 1). In the absence of ATP, which does not allow the DNA unwinding by TFIIH (Riedl et al, 2003), neither the XPG endonuclease nor the other dual incision factors were recruited to the damaged DNA (Figure 2A, lanes 1–3; data not shown). In the presence of ATP, TFIIH (as revealed by its p62 subunit) and XPG were bound to the damaged DNA at 10 min and were gradually released from the DNA thereafter (Figure 2A, lanes 4–7; Figure 2C, upper panel). At 40 min, when the removal of the damaged oligonucleotide was optimal (Figure 2B, lane 5), the level of RPA increased (Figure 2A, lanes 4 and 5; Figure 2C, upper panel). In parallel, the resynthesis factors RF-C, PCNA and Polδ (Shivji et al, 1992, 1995) replaced the dual incision factors on the DNA template, reaching a maximum at 120 min (Figure 2A, lanes 4–6; Figure 2C, middle panel). At this time, the DNA resynthesis was optimal (Figure 2B, lane 6) and RPA was removed from the template (Figure 2A, lanes 6 and 7). Within the next 60 min, RF-C and Polδ were released, leaving PCNA on the DNA (Figure 2A, lanes 6–7; Figure 2C, middle panel). The recruitment of Ligase I and FEN 1 was initiated after 40 min (Figure 2A, lanes 6 and 7; Figure 2C). Once the newly synthesized DNA was ligated to the 3′ end of the excision, we observed the arrival of CAF-1 at 180 min, indicating the end of the repair process (Figure 2A, lane 7). It is also worthwhile to mention that this fishing method allowed us to identify RF-C, Polδ, FEN 1 and Ligase I as part of the NER system, being selectively and functionally recruited by the immobilized cisplatinated DNA from NE (Supplementary data 3A). In the absence of either ATP (lanes 2–4), none of these NER factors were specifically recruited.

Figure 2.

In vitro sequential recruitment of the NER factors. (A) The immobilized damaged DNA fragment was incubated with NE. At different time points, the immobilized DNA was washed with 0.05 M KCl and the remaining bound factors were further analysed by western blot. (B) The damaged fragment removal (Dual Incision) and the gap filling (Resynthesis) activities were also followed through time (Supplementary data 1). (C) The WB signals were quantified using Genetool (Syngene) and plotted on the graphs as a percentage of the maximal binding to the DNA. (D) Coomassie staining of the highly purified human NER resynthesis factors RPA, RF-C, PCNA, Polδ, Ligase I and FEN 1. (E) The same recruitment experiment as in (B) was carried out with our complete reconstituted system (dual incision, resynthesis and ligation factors). All these experiments were carried out at least two times.

To further assess and underline the role of each of the identified factors in the NER, we used purified DNA repair factors (Figure 2D), components of the reconstituted incision system (RIS: XPC-HR23B, TFIIH, XPA, RPA, XPG and ERCC1-XPF) the reconstituted resynthesis system (RRS: RF-C, PCNA and DNA Polδ) and the reconstituted ligation system (RLS: FEN 1 and Ligase I). Their enzymatic activities were checked with in vitro repair assays (Supplementary data 1). Our reconstituted system is close to the efficiency of the NE system, as the dual incision and resynthesis efficiencies are ∼87 and ∼70%, respectively (compared to 90 and 85%, respectively, with the NE; Supplementary data 2). The comings and goings of the repair factors present in RIS, RRS and RLS on the immobilized damaged DNA were comparable to those obtained with NE (Figure 2E): the recruitment of the dual incision factors occurs early and their release is concomitant with the coming of PCNA, RF-C and Polδ (upper and middle panels). It should be noted that the reaction is slower. For example, at 210 min, significant amounts of RPA and XPG are still present on the DNA template (middle panel). This might explain the late arrival of Ligase I (Figure 2E, lower panel). It is also likely that the variations in the kinetic curves might reflect differences in the stoichiometry, the post-translational modifications and specific activities between the endogenous and the recombinant NER factors. We cannot exclude the possibility that some additional proteins that are not yet identified could participate in the NER reaction.

XPG and RPA recruit PCNA and RFC to allow DNA resynthesis

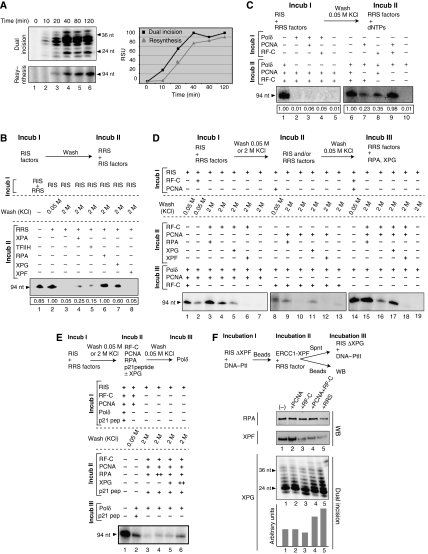

We next focused our attention on the transition between dual incision and DNA resynthesis. At different time points, we quantified dual incision and resynthesis activities. The removal of the damaged oligonucleotides strongly increased to reach a plateau at 40 min, while the gap filling was slightly delayed by 10 min (Figure 3A, upper panels). Both the kinetic curves exhibited a similar slope, suggesting a close coordination between these two steps (Figure 3A, graph).

Figure 3.

Molecular events during the resynthesis. (A) Time course of the dual incision (upper panel) and the resynthesis (middle panel). Signals were quantified (Genetool, Syngene) and plotted in a graph (square for dual incision; triangle for DNA resynthesis) (lower panel). (B) The immobilized DNA-Pt was incubated with RIS+/−RRS (Incub I). After washes at either 0.05 M KCl or 2 M KCl, DNA resynthesis were performed using RRS supplemented with some of the RIS factors as indicated (Incub II). The relative intensity of each signal is indicated at the bottom of the gel. (C) DNA-Pt was incubated with RIS either alone or in combination with the indicated RRS factors (Incub I). After 0.05 M KCl wash, the complementary RRS factors were added for DNA resynthesis (Incub II). The relative intensity of each signal is indicated at the bottom of the gel. (D) DNA-Pt was incubated with RIS either alone or with the indicated RRS factors (Incub I). After washes with either 0.05 M KCl or 2 M KCl, Pt-DNA was further incubated with the indicated RIS and/or the RRS factors (Incub II). Following a 0.05 M KCl wash, and the addition of the complementary RRS factors (Incub III), DNA resynthesis was checked. (E) The experiment was carried out similarly as described in (D), except that we added 2 nmol of a peptide corresponding to the domain of interaction between the p21 CDK inhibitor and PCNA as indicated. (F) RIS-ΔXPF and DNA-Pt were incubated with the RRS factors as indicated at the top of the panels. Following Incub I+Incub II, and a 0.05 M KCl wash, amounts of RPA (upper panel) and XPF (middle panel) remaining on the DNA fragment were checked by western blot. The released XPG (lower panel) was tested in dual incision with RIS-ΔXPG, containing DNA-PtII as a challenge template (Riedl et al, 2003). A graph depicts the relative intensity of each signal.

We also investigated whether some of the RIS factors take part in DNA resynthesis. The immobilized damaged DNA was first incubated with RIS to allow dual incision (Figure 3B, Incub I) and then washed either at 0.05 M KCl to remove the nonspecifically bound proteins or at 2 M KCl to remove all proteins from the DNA. The gapped DNA was then incubated with RRS alone or in combination with one of the RIS factors (Incub II). In the absence of certain RIS factors, there is no DNA resynthesis (Figure 3B, lanes 3 and 2). However, the incubation of the 2 M KCl-washed DNA with RRS and either RPA or XPG led to an optimal DNA resynthesis (compare lanes 6 and 7 and lane 2). On the contrary, incubation of RRS with XPA, TFIIH or XPF did not allow resynthesis (lanes 4, 5 and 8), thus establishing their exclusive role in the dual incision step. This result suggests that XPG as well as RPA plays a key role in dual incision and in DNA resynthesis.

To document the role of XPG and RPA in the recruitment of certain RRS factors, we incubated the immobilized cisplatinated DNA with RIS and a combination of RRS factors (Figure 3C, Incub I). The resulting gapped DNA/protein complex was washed at 0.05 M KCl and further incubated with a combination of RRS factors (Incub II). In such a complementation assay, the level of the resynthesis activity demonstrates whether the various factors are correctly integrated in an active intermediary complex that depends on accurate protein/protein interactions. Incubation of the RIS with Polδ alone or in combination with PCNA or RF-C (Incub I) did not allow DNA resynthesis (lanes 2–4). The incubation of the RIS with either PCNA or RF-C resulted in a weak DNA resynthesis (lanes 7–8), unless they were added together, in which case, optimal recruitment of the Polδ and DNA resynthesis is observed (lane 9). It thus seems that XPG and RPA, together with RF-C and PCNA constitute the loading platform for Polδ.

The recruitment of RF-C/PCNA on the gapped DNA was examined by carrying out a three-step resynthesis complementation experiment (Figure 3D). The gapped DNA obtained after incubation with RIS (Incub I) was washed at 2 M KCl and incubated (Incub II) with a combination of XPG, RPA, XPF/ERCC1, RF-C and PCNA. After being washed at 0.05 M KCl, the immobilized DNA was incubated with RRS factors as indicated (Incub III) to complement the resynthesis reaction. RPA (Incub II) stimulated the recruitment and/or the stabilization of RF-C, whereas XPG and XPF weakened or even prevented its binding (Figure 3D, lanes 3–6). Both XPG and RPA were able to place and stabilize the PCNA molecules present around the gapped DNA (lanes 9–12). Accordingly, RF-C+PCNA were recruited and stabilized by XPG with the assistance of RPA (lanes 15–17). We noticed that the binding of RF-C+PCNA to the gapped DNA was prevented by the presence of XPF (lane 18). These data further illustrate that the recruitment and stabilization of RFC and PCNA, which are likely to be mediated by RPA and XPG, respectively, first require the release of XPF from the DNA substrate.

To further illustrate the new role of XPG in initiating DNA resynthesis, we carried out a similar assay as in Figure 3D in which we used a peptide corresponding to the p21 domain (p21-pep) that interacts with PCNA (Cooper et al, 1999). Indeed, the p21 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor is known to induce cell-cycle arrest by preventing the PCNA/Polδ interaction (Oku et al, 1998). Preincubation of p21-pep with the PCNA/RF-C/RPA complex bound to the gapped DNA (Incub II) does not allow Polδ (Incub III) to synthesize DNA (Figure 3E, compare lanes 3 and 4 to lane 1). DNA resynthesis was restored upon the addition of increasing amounts of XPG (lanes 5 and 6) but not RPA (lanes 3 and 4), demonstrating a competition between XPG and p21-pep for targeting PCNA. This underlines the role of XPG in stabilizing the replication complex.

To investigate the fate of XPF, RPA and XPG, we incubated the immobilized damaged DNA with XPC, TFIIH, XPA, RPA and XPG before addition of XPF/ERCC1 together with a combination of the RRS (Figure 3F). After a wash at 0.05 M KCl, RPA and XPF remaining on the DNA were analysed by western blot, and the supernatant was tested for dual incision activity to check the release of XPG. The release of RPA only occurred upon simultaneous addition of PCNA, RF-C and Polδ (Figure 3F, upper panel). This result showed that RPA is released as soon as the Polδ is recruited. Similarly, the recruitment of RF-C alone or combined with PCNA, promotes the release of XPF (middle panel). Dual incision assays carried out on the supernatant of the various fractions showed that the release of XPG was stimulated upon the addition of RF-C+PCNA together and evenmoreso in the presence of the complete RRS (lower panel and quantifications).

Altogether, our data strongly show that in the context of NER, XPG and RPA are the key players in initiating DNA resynthesis, a replication-like process. We have demonstrated that XPG recruits and stabilizes PCNA to the gapped DNA with its replicative partners RF-C and Polδ. Our results even suggest that this interaction could protect PCNA from inhibitors like p21.

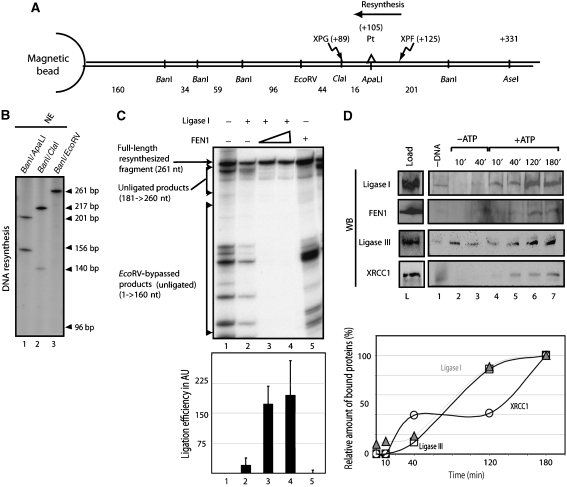

The ligation of the newly synthesized DNA fragment

Finally, we checked whether the newly synthesized DNA strand was ligated to the DNA template. After being incubated with NE and radiolabelled nucleotides (Supplementary data 3A), the immobilized DNA was digested by a combination of restriction enzymes (BanI and ApaLI or ClaI or EcoRV, see Figure 4A). Whether the digested fragments are radiolabelled or not is dependent on the number of radiolabelled dCTPs incorporated per DNA molecule and also on the position of the ligation site. For instance, (i) digestion by ApaLI and BanI, resulted in 156 and 201 bp labelled fragments demonstrating that DNA resynthesis encompassed the restored ApaLI site (Figure 4A and B, lane 1), (ii) digestion by BanI and ClaI resulted in the 140 and 217 bp labelled fragments (lane 2), and (iii) digestion by EcoRV and BanI resulted in a single labelled 261 bp DNA fragment, demonstrating that the ligation occurs between the EcoRV and ClaI sites (beyond the 3′ XPG incision site, which is located on the ClaI site) (lane 3). Therefore, the NER ligation occurred after a ‘nick translation' process originated by the ongoing Polδ (Ayyagari et al, 2003). Knowing the number of incorporated radiolabelled dCTPs in the 201 and 217 bp fragments and their intensity on the radiograph, it is possible to estimate the number of incorporated radiolabelled dCTPs in the ligated fragments and thus determine the position of the ligation site. This one is located around 10 nucleotides after the XPG incision site when using Ligase I and FEN1.

Figure 4.

The ligation in NER. (A) Scheme of the substrate used with the position of the lesion, the restriction sites and the endonucleases cut sites. The sense of resynthesis is indicated. (B) DNA-Pt was incubated with a NE. The repaired DNA was then digested with indicated restriction enzymes. The absence of the 96 nt signal proved that the ligation occurred between ClaI and EcoRV (lane3). (C) The ligation activity was investigated by incubating the DNA with the RIS+RRS and combinations of the ligation system (RLS) before digestion by EcoRV and BanI. The unligated DNA due to the absence of ligation could be easily discriminated from the unligated DNA due to nick translation process, bypassing the EcoRV site. To evaluate the ligation efficiency, the ratio between the full-length resynthesized DNA and all the forms of unligated DNA was calculated. (D) The recruitment of Ligase III and XRCC1 on the damaged DNA was investigated with a method described in Figure 2. Western blot (WB) signals (upper panel) were quantified and plotted (lower panel) (open circle: XRCC1; open triangle: Ligase III).

We identified LigaseI/FEN1 (Figure 2A) as candidates to carry out the ligation once DNA resynthesis was performed on the damaged DNA (Shivji et al, 1995; Araujo et al, 2000). The immobilized DNA was then incubated with RIS+RRS in addition to Ligase I and FEN1 as indicated in Figure 4D, before digestion by EcoRV and BanI. We observed that (i) the DNA fragments of a size smaller than 160 nt result from the nick translation process, bypassing the EcoRV restriction site (lane 1) and escaping ligation; (ii) the products between 180 and 250 nt are characteristic of unligated DNA between the damage site and the EcoRV site; (iii) the ligated DNA corresponds to the 261 nt signal (lanes 1–5). Addition of Ligase I did not allow a proper ligation of the newly synthesized DNA (lane 2) unless associated with FEN1 (lanes 3 and 4). Indeed, FEN1 works in association with the Polδ and Ligase I to limit the nick translation process and, therefore, stimulates the ligation. However, FEN1 does not block the ongoing Polδ or promote the ligation by itself (lane 5) (Ayyagari et al, 2003).

Ligase III and XRCC1 are known to be involved in base-excision repair and single-strand break repair pathways (Mortusewicz et al, 2006; Almeida and Sobol, 2007). Recent data suggest that both factors are also involved in the NER ligation (Moser et al, 2007). Therefore, we checked over the ligation activity of Ligase III and XRCC1 after a Polδ-dependent resynthesis. We have found that these two factors, coming from a NE, were recruited to the damaged DNA following a kinetic close to that of LigaseI and FEN1 (Figure 4D); however, their ligation activities were much lower (Supplementary data 3).

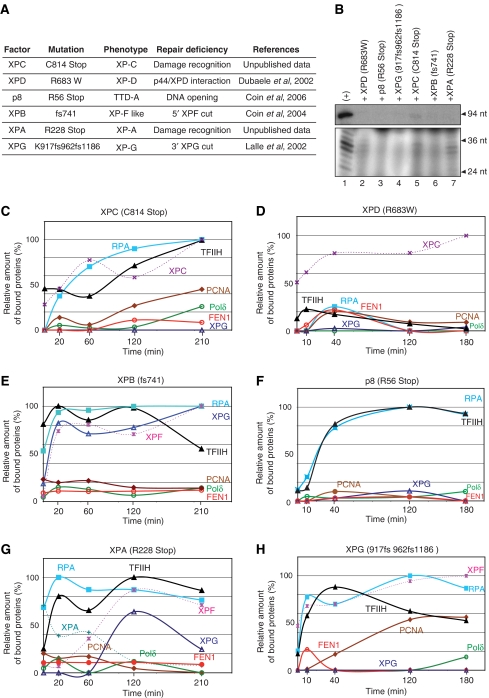

Biochemical defects originating from mutations in NER factors

To unravel the sequential interactions between the NER factors and to determine the exact role of XPG in recruiting the replicative complex, we investigated how mutations found within XP and TTD patients (Figure 5A) disturb NER at the molecular level. The following experiments were performed (as described in Figure 2) using NE from the XP, XP/CS or TTD patients or using recombinant NER proteins. Each of these mutated proteins prevents the elimination of the DNA damage, as we could not generate any dual incision or resynthesis activity (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Recruitment of the NER machinery involving mutated factors. (A) Data concerning the mutated factors used and references. (B) Dual incision and resynthesis assays were carried out with each mutant (lanes 2–8). WT factors were used for the positive control (lane 1). The recruitment analysis of the NER factors was carried out as described previously with mutated forms of (C) XPC, (E) XPB and (G) XPA used in a reconstituted system and (D) XPD, (F) p8 and (H) XPG coming from patient cell extracts.

By using a mutated XPC in which the C-terminus was deleted (XPC/C814st), we observed a delay and a decrease in the binding of this mutant, TFIIH and RPA to the damaged DNA. We detected minimal opening of the DNA when XPC+TFIIH were bound in the presence of ATP (Figures 2C and 5C; unpublished results). Under those conditions, XPG cannot be recruited (Figure 5C), which explains the absence of dual incision and why PCNA and the other factors cannot target the DNA despite the presence of RPA. This demonstrates how crucial the simultaneous presence of RPA and XPG are for recruiting PCNA, which is essential for DNA resynthesis (as also observed Figure 3D).

TFIIH containing the XPB/fs740, which was shown to prevent the removal of the damaged oligonucleotide (Araujo et al, 2000), was incubated with the complete reconstituted system (Figure 5E). Although the recruitment of TFIIH/XPB/fs740, RPA, XPG and XPF dual incision factors is the same as with TFIIHwt (Figures 2E and 5E), their release from the immobilized DNA does not occur (Oh et al, 2007). Although this XPB mutation allows DNA opening as well as the recruitment of XPF and XPG, we only observed the 3′ cut performed by XPG (Coin et al, 2004) with XPF being present but inactive (Figure 5E). As a consequence, the recruitment of PCNA (and partners such as Polδ and RF-C) that requires the XPF release from the damaged DNA, does not occur. These data (Figures 2E and 5E) demonstrate that the recruitment of PCNA is dependent not only on the presence of both XPG and RPA on the damaged DNA but also on the 5′ incision by XPF.

We next focused our attention on the XPD/R683W mutation that weakens the XPD/p44 interaction within TFIIH and inhibits the XPD helicase activity (Dubaele et al, 2003). XPCwt that was bound to the immobilized damaged DNA is unable to recruit and/or stabilize TFIIH/XPD/R683W, explaining the absence of the other NER factors (Figure 5D). It thus can be concluded that preserving the protein/protein interactions as well as the optimal XPD helicase activity of TFIIH is a prerequisite for the formation of the ternary XPC/TFIIH/damaged DNA complex and the recruitment of the other NER factors.

TFIIH containing the TTD-A/p8/R56st mutated subunit present in cell extracts from patients can still bind to the XPC/damaged DNA complex (Figure 5F). Neither XPG nor the resynthesis factors can be recruited. Interestingly, we noticed that RPA binds to the damaged DNA already targeted by TFIIH (Figure 5E–H), suggesting the presence of a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) region (Bochkareva et al, 2001). It thus seems that the p8 defect in stimulating the XPB ATPase activity (Coin et al, 2006) impairs not only the proper damaged DNA opening but also the further recruitment of NER factors.

XPA/R228st does not efficiently bind to the damaged DNA already targeted by XPC, TFIIH and RPA (Figure 5G). As XPA/R228stop is unable to maintain the opened damaged DNA (Tapias et al, 2004; unpublished results), the recruitment of XPF is delayed and not optimal (Figure 5G) in agreement with published data (Volker et al, 2001; Oh et al, 2007). XPG has been recently shown to be tightly associated to TFIIH (Ito et al, 2007) explaining its early recruitment in vivo (Volker et al, 2001). By using highly purified TFIIH, it could be explained why we observed an XPG recruitment in an XPA-dependent manner (Riedl et al, 2003; Figure 5G). The delayed recruitment of the endonucleases might explain the deficiency in the NER activity (Figure 5B, lane 7). In such conditions, although XPG and RPA are present on the damaged DNA, neither PCNA nor Polδ can be recruited.

XPG/917fs962fs1186 present in the XP3BR patient cell extract (Lalle et al, 2002), did not bind to the damaged DNA already opened by TFIIH and XPA (Figure 5H; Evans et al, 1997). We also noticed the presence of RPA and XPF. Despite the absence of XPG and the lack of the 3′ incision, PCNA is partially recruited. At this point, the absence of Polδ and the partial recruitment of PCNA corroborate the role of XPG in stabilizing PCNA to the gapped DNA.

Discussion

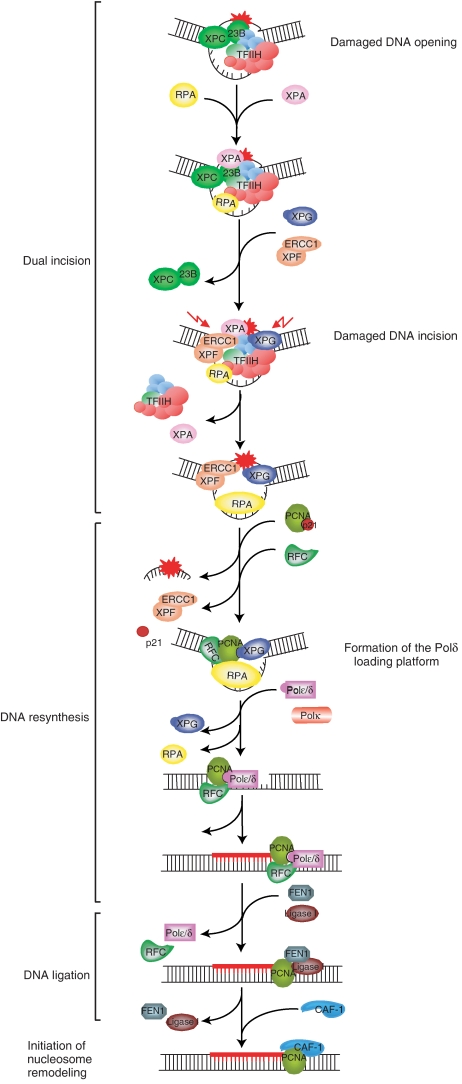

To address the biochemical mechanisms underlying the coordination between the various proteins required for NER, we employed the immobilized template assay. This approach combines the recruitment of the factors with functional enzymatic assays allowing NER to occur. Having identified the main components of the NER, we thus were able to follow the NER reaction in which 11 highly purified factors (representing 33 polypeptides) repair the immobilized damaged DNA, thereby mimicking the in vivo situation. In addition, using NER factors that contain mutations found in XP and TTD patients, we were able to pinpoint the biochemical defects. Finally, the present study provides new insights into the mechanisms by which dual incision and repair synthesis factors work together to fill the gap formed after dual incision, which contributes to a more detailed understanding of the first steps of NER (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sequential complexes in NER from the damage recognition to the ligation of newly synthesized DNA fragment. The function of the damaged DNA/XPC–HR23B/TFIIH complex was previously described by Riedl et al (2003) and Coin et al (2004, 2006, 2007). After the recruitment of XPA, RPA, XPG and finally XPF, the incision by the endonucleases allows the removal of the patch and the recruitment of the resynthesis factors. RF-C is stabilized by RPA and induces the release of XPF, whereas PCNA is stabilized by XPG and RPA. The presence of XPG could protect PCNA from the inhibitory effect of p21. The further recruitment of the Polδ is then possible and provokes the release of XPG (which protective effect is not any more needed) and RPA. After gap filling, we suggest that FEN1 and Ligase I stop the ongoing Polδ due to interactions with PCNA and allow ligation. Finally, the nucleosome assembly is carried out with by CAF-1.

From damage recognition to DNA incision

The distortion induced by the lesion is first recognized by the XPC/HR23B complex (Sugasawa et al, 1998; Mocquet et al, 2007), which then recruits TFIIH (Volker et al, 2001; Riedl et al, 2003). Here, we observed the essential role of XPC in positioning TFIIH (Tapias et al, 2004), allowing it to unwind the damaged DNA.

In the presence of ATP, p44 stimulates the XPD helicase activity (Dubaele et al, 2003), whereas p52, upon p8 mediation, stimulates the XPB ATPase activity (Coin et al, 2006, 2007). This allows the opening of the damaged DNA, a prerequisite for the recruitment of the other factors. Mutations in either XPD or in p8/TTD-A, disturb the opening, thus underlining their specific roles—XPD/R683W mutation prevents TFIIH recruitment, p8/TTD-A allows the recruitment of TFIIH and RPA—which suggest that the presence of TFIIH per se is sufficient to promote the recruitment of RPA. Corroborating these observations, we also found that the use of XPA/R228st does not impair the arrival of RPA (Figure 5G; Rademakers et al, 2003), that is likely to be devoted to single-stranded-DNA protection (Bochkareva et al, 2001). We do not exclude the possibility that XPA and RPA might bind to the DNA synergistically; the stabilization of the opened DNA by XPA may favour the positioning of the RPA molecules.

XPA then stabilizes the ternary complex and increases the local DNA unwinding around the lesion (Evans et al, 1997; Tapias et al, 2004), allowing the recruitment of both endonucleases XPG and ERCC1-XPF, which incise the damaged oligonucleotide at the 3′ and 5′ sides, respectively (O'Donovan et al, 1994; Sijbers et al, 1996). During the course of the dual incision, XPC is recycled concomitantly with the positioning of XPG, respectively (Riedl et al, 2003). TFIIH and XPA are most likely released after the incision/excision of the damaged oligonucleotide, as a 40 aa residue of XPB is necessary for the ERCC1-XPF cut (Figure 5B), and XPA stimulates the activities of endonucleases (Bartels and Lambert, 2007).

RPA and XPG mediate the transition between dual incision and resynthesis

At this point, it is worthwhile to note that not only RPA but also the 5′ endonuclease XPG plays a central role in initiating the DNA resynthesis step, a ‘replication-like process'. Our data demonstrate that dual incision and DNA resynthesis are closely coordinated and that such a transition requires (i) the DNA opening by TFIIH (Figures 2C and 5E), (ii) the XPF incision (Figure 5E) and (iii) the simultaneous presence of RPA and XPG on the damaged DNA (Figure 5). Furthermore, XPG then would be responsible for recruiting PCNA either alone or together with RF-C (Gary et al, 1999; Miura, 1999) to the vicinity of the gap (Figure 3). Simultaneously with the recruitment of PCNA by XPG, RF-C interacts with (Yuzhakov et al, 1999) and is recruited by RPA onto the 30 nt gap (Figure 3). This would consequently lead to position RF-C together with PCNA at the 3′ primer template junction, as the loading of RF-C+PCNA is associated with the release of the XPF endonuclease as well as to the damaged oligonucleotide (Figures 3D, F; data not shown).

A phospho/dephosphorylation process occurring after UV stress, may direct RPA towards either the repair or replication pathways (Henricksen et al, 1996). Similarly, the phosphorylation of XPG (Winkler et al, 2001) could modulate its own activity and the recruitment of the resynthesis factors. This kind of partnership promoted by potential post-translational modifications (Araujo and Wood, 1999) would speed up the transition between dual incision and DNA resynthesis and, thus, the efficiency of the global repair. Additionally, this would avoid the persistence of multiple small ssDNA gaps, which could lead to double-strand breaks, as already observed in XP/CS cells (Berneburg et al, 2000; Theron et al, 2005).

The recruitment of Polδ is associated with the release of XPG and RPA

During NER, RFC and PCNA form a complex similar to what occurs during replication with the sliding clamp (Tsurimoto and Stillman, 1991) and dependent on the RF-C ATPase activity (Gomes et al, 2001). Together with RPA and XPG, these proteins constitute a stable platform ready to be targeted by Polδ (Nishida et al, 1988; Zeng et al, 1994). It is worthwhile to point out the role of XPG in both stabilizing and recruiting PCNA on the gapped DNA, which might prevent inhibition of DNA resynthesis by p21 (Shivji et al, 1998). Then the release of XPG (Figure 3) parallels the initiation of DNA resynthesis. As the DNA synthesis proceeds, RPA, which protects ssDNA (Bochkareva et al, 2001), is also released. We do not exclude the possibility that other DNA polymerases could substitute for Polδ in the NER process. Despite the fact that Polɛ and Polκ are suggested to be candidates for NER in vivo (Shivji et al, 1995; Ogi and Lehmann, 2006), our confocal microscopy experiments (Figure 1) as well as the immobilized template assay with NE (Figure 2) clearly identified Polδ at the sites of damage. Recent findings corroborate this point (Moser et al, 2007).

PCNA mediates the transition between resynthesis and ligation

The last phase of the NER pathway starts with the arrival of FEN 1 and Ligase I (Prigent et al, 1994; Araujo et al, 2000), which occurs concomitantly with the release of RF-C and Polδ (Figure 4B). PCNA, still present on the DNA, would bridge the resynthesis and the ligation steps, in a pathway similar to what occurs during the maturation of the Okazaki fragments (Montecucco et al, 1998). As Polδ, FEN1 and Ligase I target the same PCNA domain (Warbrick, 2000), it is likely that they are sequentially recruited onto PCNA and that their presence is mutually exclusive. In a manner similar to RPA, PCNA is subjected to post-translational modifications such as ubiquitination after UV irradiation (Essers et al, 2005).

It has recently been shown that Ligase III associated with XRCC1 could be involved in the ligation step of NER in a cell-cycle-dependant manner and following DNA resynthesis by Polδ (Moser et al, 2007). With our non-synchronized cell extracts, we indeed observed their recruitment in the later times of the reaction. Nevertheless in our hands, using Polδ, their ligation efficiency is lower than the one performed with Ligase I and FEN1. It is possible that the Ligase III/XRCC1 efficiency could be improved with other DNA polymerases such as Polɛ (Shivji et al, 1995) or Polκ (Ogi and Lehmann, 2006). It thus can be hypothesized that different resynthesis and ligation systems can coexist in the cell and their involvement in DNA repair would depend on their availability at the time of repair.

Finally, we observed the late arrival of CAF-1, likely through PCNA, once the ligation had occurred (Figures 1 and 2A). Indeed, the naked repaired DNA has to be re-chromatinized and the chaperone CAF-1 can recruit histones H3 and H4 (Gaillard et al, 1996; Green and Almouzni, 2003; Polo et al, 2006). Its presence on the DNA would suggest that nucleosome reassembly or repositioning on the naked DNA starts as soon as the DNA repair process has finished.

While some of the steps of NER-like damage recognition, DNA opening or incision by the endonucleases have been described many times, the transition between the dual incision and the resynthesis, which is as important as the previous steps for an accurate, quick and errorless DNA restoration, had never been described before (Gillet and Scharer, 2006). Thus, our work underlines the complexity of the network of interactions between NER factors that can modulate their stability, positioning on the damaged DNA and their respective enzymatic activities. Moreover, it allows us to establish and locate the biochemical defects associated with mutations found in patients suffering from repair syndromes.

Materials and methods

Local irradiation and immunofluorescence

XPCS2BA fibroblasts (T293C (F99S) transition), derived from XPCS patients and corrected (Riou et al, 1999), were grown in F10 (Ham) media (Gibco-BRL), 12% FCS and 10 mg/ml gentamicyn in 5% CO2 for 2 days in two chambers slides (Labtek® II chamber slide w/Cover 2 wells). Cells were rinsed in PBS, individually covered with an Isopore 3.0 μm filter (Millipore) and irradiated locally at 254 nm with 70 J m−2 (Volker et al, 2001). Following incubation at 37°C, cells were treated as described by Green and Almouzni (2003) to perform immunofluorescence analysis.

Proteins

XPC/HR23B, TFIIH, XPA, RPA, XPG and ERCC1-XPF recombinant proteins involved in dual incision (Aboussekhra et al, 1995) have been produced and highly purified as described previously (Araujo et al, 2000; Tapias et al, 2004). PCNA (Biggerstaff and Wood, 2006), DNA Ligase I (Mackenney et al, 1997) and FEN1 (Robins et al, 1994) have been purified from Escherichia coli. Polδ (Xie et al, 2002) as well as RFC (Podust and Fanning, 1997) were produced in insect cells and purified accordingly. Mutated forms of recombinant XPC (C814st), XPA (R228st) and XPB (fs741) as well as extracts from TTDA (p8/R56st), XPD (R683W) and XPG (917fs962fs1186) patients were also used in Figure 5.

DNA substrates

The damaged DNA substrates contain a single 1,3-intrastrand d(GpTpG) cisplatin–DNA crosslink (Shivji et al, 1999) and are based on the 105.TS plasmid (Frit et al, 2002) known as DNA-Pt. The immobilized damaged substrate was prepared as explained by Lainé et al (2006): the DNA was first digested by FokI and then biotin was incorporated to the DNA by incubation of 1 mM of each biotin-dUTP (USB), dCTP and dGTP with Kleenow enzyme (New England Biolabs). Finally, the DNA was digested by AseI and the 722-bp fragment was further purified. A 3 μl volume of Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin were mixed with each 100 ng of DNA in buffer A (10 mM Tris–HCl pH7.2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, 0.02% and NP-40) for 20 min at room temperature. The immobilized damaged DNA was washed two times in buffer B (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol and 0.02% NP-40) before being used.

Protein-binding studies on immobilized DNA

A 100 ng portion of immobilized DNA was incubated with cells extracts [Hela(wt), TTD1BR(TTD-A), XP3BR(XP-G), HD2(XP-D)] or with the purified DNA repair factors mutated or not, as indicated. Magnetic beads were collected and supernatants removed. Beads were then washed three times in 200 μl of cold buffer B containing either 50 mM or 2 M KCl and either resuspended in SDS–PAGE loading buffer for western blotting or in a reaction mixture for functional analysis of bound proteins. Studies were carried out with the equivalent of four dual incision reactions for western blotting analysis and with the equivalent of one dual incision reaction for the functional protein-binding assay. Each experiment as been carried out at least two times.

Dual incision and DNA resynthesis assays

Reconstituted dual incision reactions (25 μl) were carried out in a buffer B (Araujo et al, 2000; Lainé et al, 2006). The dual incision factors XPC-HR23B (50 ng), TFIIH (100 ng), XPA (30 ng), RPA (200 ng), XPG (150 ng) and XPF-ERCC1 (50 ng) were incubated with 100 ng of the immobilized damaged DNA, for indicated times at 30°C in the presence of 2 mM ATP.

Reconstituted resynthesis reactions were carried out in identical buffers as dual incision assay with RIS in addition to PCNA (70 ng), RF-C (150 ng) and Polδ (300 ng). Ligase I (200 ng) and FEN 1 (50 ng) were added when indicated. Proteins were incubated with a mixture of 20 μM of each dATP, dGTP, dTTP, 5 μM of cold dCTP and 2.5 μCi α32P dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) at 30°C for 2 h. The DNA was washed with buffer A and digested with EcoRI and NdeI, resulting in a 94-nt fragment containing the resynthesized DNA patch. Restriction reactions were loaded on a denaturating 8% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. Resynthesis with HeLa NE (50 μg) (Dignam et al, 1983) was performed in the same conditions as dual incision (Shivji et al, 1995) with 20 μM of each dATP, dGTP, dTTP, 5 μM of cold dCTP and 2.5 μCi α 32P dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol). The mixture was incubated at 30°C for the indicated times. The DNA fragment was then purified and digested by EcoRI and NdeI as described above.

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal (MAb) and rabbit polyclonal (PAb) antibodies were used as primary antibodies by Riedl et al (2003). Following antibodies were used in this study: TFIIH (p62): MAb 3C9 and (p89) S-19: sc-293 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); RPA32/70: PAb N2.2 (Henricksen et al, 1994); XPG: MAb 1B5 raised against peptide amino acids 1167–1186; XPF: MAb Ab-5 (NeoMarkers); PCNA: MAb (PC10): sc-56 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and PAb ab2426 (AbCam) (Green and Almouzni, 2003); RF-C: PAb (H-183): sc-20996 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Beckwith et al, 1998); DNA Polymerase δ: MAb (A-9): sc-17776 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Zeng et al, 1994); FEN 1: PAb (H-300): sc-13051 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Waga et al, 1994); Ligase I PAb raised against amino acids 901–919; CAF-1: MAb (SS1 1–13): NB 500–207 (NeoMarkers) (Green and Almouzni, 2003); CPD: MAb TDM2 D194-1 (MBL) (Coin et al, 2006).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 3

Acknowledgments

We thank F Coin, R Velez Cruz and B Bernardes de Jesus for fruitful discussions and critical reading of the paper. We thank C Braun and I Kolb for invaluable assistance. We thank also B Stillman for the RF-C p140 antibody, RD Wood for the PCNA expression vector, W Bohr for the FEN1 expression vector, J Hurwitz for the RF-C baculoviruses expression vectors, T Lindahl for the ligase I and III expression vector and P Radicella for XRCC1 expression plasmid. This study has been supported by funds from ‘La Ligue contre le Cancer' (équipe labellisée, contract no EL2004), the ‘Ministère de l'Education National et de la Recherche', the ACI grants (BCMS no 03 2 535) and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-05-MRAR-005-01). M Lee's lab was supported by Phillip Morris USA Inc., Phillip Morris Inernational. VM has been supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM/region Alsace fellowship), la Ligue contre le Cancer et l'Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer. JPL was granted by the Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer and EEC grant (QLRT-1999-2002).

References

- Aboussekhra A, Biggerstaff M, Shivji MK, Vilpo JA, Moncollin V, Podust VN, Protic M, Hubscher U, Egly JM, Wood RD (1995) Mammalian DNA nucleotide excision repair reconstituted with purified protein components. Cell 80: 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida KH, Sobol RW (2007) A unified view of base excision repair: lesion-dependent protein complexes regulated by post-translational modification. DNA Repair (Amst) 6: 695–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo SJ, Tirode F, Coin F, Pospiech H, Syvaoja JE, Stucki M, Hubscher U, Egly JM, Wood RD (2000) Nucleotide excision repair of DNA with recombinant human proteins: definition of the minimal set of factors, active forms of TFIIH, and modulation by CAK. Genes Dev 14: 349–359 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo SJ, Wood RD (1999) Protein complexes in nucleotide excision repair. Mutat Res 435: 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari R, Gomes XV, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM (2003) Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. I. Distribution of functions between FEN1 AND DNA2. J Biol Chem 278: 1618–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels CL, Lambert MW (2007) Domains in the XPA protein important in its role as a processivity factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 356: 219–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith WH, Sun Q, Bosso R, Gerik KJ, Burgers PM, McAlear MA (1998) Destabilized PCNA trimers suppress defective Rfc1 proteins in vivo and in vitro. Biochemistry 37: 3711–3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berneburg M, Lowe JE, Nardo T, Araujo S, Fousteri MI, Green MH, Krutmann J, Wood RD, Stefanini M, Lehmann AR (2000) UV damage causes uncontrolled DNA breakage in cells from patients with combined features of XP-D and Cockayne syndrome. EMBO J 19: 1157–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggerstaff M, Wood RD (2006) Repair synthesis assay for nucleotide excision repair activity using fractionated cell extracts and UV-damaged plasmid DNA. Methods Mol Biol 314: 417–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkareva E, Belegu V, Korolev S, Bochkarev A (2001) Structure of the major single-stranded DNA-binding domain of replication protein A suggests a dynamic mechanism for DNA binding. EMBO J 20: 612–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin F, Auriol J, Tapias A, Clivio P, Vermeulen W, Egly JM (2004) Phosphorylation of XPB helicase regulates TFIIH nucleotide excision repair activity. EMBO J 23: 4835–4846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin F, Oksenych V, Egly JM (2007) Distinct roles for the XPB/p52 and XPD/p44 subcomplexes of TFIIH in damaged DNA opening during nucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell 26: 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin F, Proietti De Santis L, Nardo T, Zlobinskaya O, Stefanini M, Egly JM (2006) p8/TTD-A as a repair-specific TFIIH subunit. Mol Cell 21: 215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compe E, Drane P, Laurent C, Diderich K, Braun C, Hoeijmakers JH, Egly JM (2005) Dysregulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor target genes by XPD mutations. Mol Cell Biol 25: 6065–6076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MP, Balajee AS, Bohr VA (1999) The C-terminal domain of p21 inhibits nucleotide excision repair in vitro and in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 10: 2119–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat WL, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH (1999) Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev 13: 768–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Martin PL, Shastry BS, Roeder RG (1983) Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol 101: 582–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubaele S, Proietti De Santis L, Bienstock RJ, Keriel A, Stefanini M, Van Houten B, Egly JM (2003) Basal transcription defect discriminates between xeroderma pigmentosum and trichothiodystrophy in XPD patients. Mol Cell 11: 1635–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers J, Theil AF, Baldeyron C, van Cappellen WA, Houtsmuller AB, Kanaar R, Vermeulen W (2005) Nuclear dynamics of PCNA in DNA replication and repair. Mol Cell Biol 25: 9350–9359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Moggs JG, Hwang JR, Egly JM, Wood RD (1997) Mechanism of open complex and dual incision formation by human nucleotide excision repair factors. EMBO J 16: 6559–6573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frit P, Kwon K, Coin F, Auriol J, Dubaele S, Salles B, Egly JM (2002) Transcriptional activators stimulate DNA repair. Mol Cell 10: 1391–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard PH, Martini EM, Kaufman PD, Stillman B, Moustacchi E, Almouzni G (1996) Chromatin assembly coupled to DNA repair: a new role for chromatin assembly factor I. Cell 86: 887–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary R, Kim K, Cornelius HL, Park MS, Matsumoto Y (1999) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen facilitates excision in long-patch base excision repair. J Biol Chem 274: 4354–4363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet LC, Scharer OD (2006) Molecular mechanisms of mammalian global genome nucleotide excision repair. Chem Rev 106: 253–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes XV, Schmidt SL, Burgers PM (2001) ATP utilization by yeast replication factor C. II. Multiple stepwise ATP binding events are required to load proliferating cell nuclear antigen onto primed DNA. J Biol Chem 276: 34776–34783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CM, Almouzni G (2003) Local action of the chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 at sites of nucleotide excision repair in vivo. EMBO J 22: 5163–5174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricksen LA, Carter T, Dutta A, Wold MS (1996) Phosphorylation of human replication protein A by the DNA-dependent protein kinase is involved in the modulation of DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 3107–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricksen LA, Umbricht CB, Wold MS (1994) Recombinant replication protein A: expression, complex formation, and functional characterization. J Biol Chem 269: 11121–11132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JH (2001) Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature 411: 366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Kuraoka I, Chymkowitch P, Compe E, Takedachi A, Ishigami C, Coin F, Egly JM, Tanaka K (2007) XPG stabilizes TFIIH, allowing transactivation of nuclear receptors: implications for Cockayne syndrome in XP-G/CS patients. Mol Cell 26: 231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Kondratick CM, Prakash S, Prakash L (1999) hRAD30 mutations in the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum. Science 285: 263–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KH, Patronas NJ, Schiffmann R, Brooks BP, Tamura D, DiGiovanna JJ (2007) Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: a complex genotype–phenotype relationship. Neuroscience 145: 1388–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lainé JP, Mocquet V, Egly JM (2006) TFIIH enzymatic activities in transcription and nucleotide excision repair. Methods Enzymol 408: 246–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalle P, Nouspikel T, Constantinou A, Thorel F, Clarkson SG (2002) The founding members of xeroderma pigmentosum group G produce XPG protein with severely impaired endonuclease activity. J Invest Dermatol 118: 344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann AR (2003) DNA repair-deficient diseases, xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy. Biochimie 85: 1101–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenney VJ, Barnes DE, Lindahl T (1997) Specific function of DNA ligase I in simian virus 40 DNA replication by human cell-free extracts is mediated by the amino-terminal non-catalytic domain. J Biol Chem 272: 11550–11556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura M (1999) Detection of chromatin-bound PCNA in mammalian cells and its use to study DNA excision repair. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 40: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocquet V, Kropachev K, Kolbanovskiy M, Kolbanovskiy A, Tapias A, Cai Y, Broyde S, Geacintov NE, Egly JM (2007) The human DNA repair factor XPC-HR23B distinguishes stereoisomeric benzo[a]pyrenyl-DNA lesions. EMBO J 26: 2923–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucco A, Rossi R, Levin DS, Gary R, Park MS, Motycka TA, Ciarrocchi G, Villa A, Biamonti G, Tomkinson AE (1998) DNA ligase I is recruited to sites of DNA replication by an interaction with proliferating cell nuclear antigen: identification of a common targeting mechanism for the assembly of replication factories. EMBO J 17: 3786–3795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortusewicz O, Rothbauer U, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H (2006) Differential recruitment of DNA Ligase I and III to DNA repair sites. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 3523–3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser J, Kool H, Giakzidis I, Caldecott K, Mullenders LH, Fousteri MI (2007) Sealing of chromosomal DNA nicks during nucleotide excision repair requires XRCC1 and DNA ligase III alpha in a cell-cycle-specific manner. Mol Cell 27: 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida C, Reinhard P, Linn S (1988) DNA repair synthesis in human fibroblasts requires DNA polymerase delta. J Biol Chem 263: 501–510 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan A, Davies AA, Moggs JG, West SC, Wood RD (1994) XPG endonuclease makes the 3′ incision in human DNA nucleotide excision repair. Nature 371: 432–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogi T, Lehmann AR (2006) The Y-family DNA polymerase kappa (pol kappa) functions in mammalian nucleotide-excision repair. Nat Cell Biol 8: 640–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh KS, Imoto K, Boyle J, Khan SG, Kraemer KH (2007) Influence of XPB helicase on recruitment and redistribution of nucleotide excision repair proteins at sites of UV-induced DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 6: 1359–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku T, Ikeda S, Sasaki H, Fukuda K, Morioka H, Ohtsuka E, Yoshikawa H, Tsurimoto T (1998) Functional sites of human PCNA which interact with p21 (Cip1/Waf1), DNA polymerase delta and replication factor C. Genes Cells 3: 357–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podust VN, Fanning E (1997) Assembly of functional replication factor C expressed using recombinant baculoviruses. J Biol Chem 272: 6303–6310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo SE, Roche D, Almouzni G (2006) New histone incorporation marks sites of UV repair in human cells. Cell 127: 481–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent C, Satoh MS, Daly G, Barnes DE, Lindahl T (1994) Aberrant DNA repair and DNA replication due to an inherited enzymatic defect in human DNA ligase I. Mol Cell Biol 14: 310–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademakers S, Volker M, Hoogstraten D, Nigg AL, Mone MJ, Van Zeeland AA, Hoeijmakers JH, Houtsmuller AB, Vermeulen W (2003) Xeroderma pigmentosum group A protein loads as a separate factor onto DNA lesions. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5755–5767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl T, Hanaoka F, Egly JM (2003) The comings and goings of nucleotide excision repair factors on damaged DNA. EMBO J 22: 5293–5303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou L, Zeng L, Chevallier-Lagente O, Stary A, Nikaido O, Taieb A, Weeda G, Mezzina M, Sarasin A (1999) The relative expression of mutated XPB genes results in xeroderma pigmentosum/Cockayne's syndrome or trichothiodystrophy cellular phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1125–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins P, Pappin DJ, Wood RD, Lindahl T (1994) Structural and functional homology between mammalian DNase IV and the 5′-nuclease domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. J Biol Chem 269: 28535–28538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivji KK, Kenny MK, Wood RD (1992) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is required for DNA excision repair. Cell 69: 367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivji MK, Ferrari E, Ball K, Hubscher U, Wood RD (1998) Resistance of human nucleotide excision repair synthesis in vitro to p21Cdn1. Oncogene 17: 2827–2838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivji MK, Moggs JG, Kuraoka I, Wood RD (1999) Dual-incision assays for nucleotide excision repair using DNA with a lesion at a specific site. Methods Mol Biol 113: 373–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivji MK, Podust VN, Hubscher U, Wood RD (1995) Nucleotide excision repair DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase epsilon in the presence of PCNA, RFC, and RPA. Biochemistry 34: 5011–5017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbers AM, de Laat WL, Ariza RR, Biggerstaff M, Wei YF, Moggs JG, Carter KC, Shell BK, Evans E, de Jong MC, Rademakers S, de Rooij J, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH, Wood RD (1996) Xeroderma pigmentosum group F caused by a defect in a structure-specific DNA repair endonuclease. Cell 86: 811–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugasawa K, Ng JM, Masutani C, Iwai S, van der Spek PJ, Eker AP, Hanaoka F, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH (1998) Xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex is the initiator of global genome nucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell 2: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapias A, Auriol J, Forget D, Enzlin JH, Scharer OD, Coin F, Coulombe B, Egly JM (2004) Ordered conformational changes in damaged DNA induced by nucleotide excision repair factors. J Biol Chem 279: 19074–19083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theron T, Fousteri MI, Volker M, Harries LW, Botta E, Stefanini M, Fujimoto M, Andressoo JO, Mitchell J, Jaspers NG, McDaniel LD, Mullenders LH, Lehmann AR (2005) Transcription-associated breaks in xeroderma pigmentosum group D cells from patients with combined features of xeroderma pigmentosum and Cockayne syndrome. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8368–8378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurimoto T, Stillman B (1991) Replication factors required for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. II. Switching of DNA polymerase alpha and delta during initiation of leading and lagging strand synthesis. J Biol Chem 266: 1961–1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volker M, Mone MJ, Karmakar P, van Hoffen A, Schul W, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JH, van Driel R, van Zeeland AA, Mullenders LH (2001) Sequential assembly of the nucleotide excision repair factors in vivo. Mol Cell 8: 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waga S, Bauer G, Stillman B (1994) Reconstitution of complete SV40 DNA replication with purified replication factors. J Biol Chem 269: 10923–10934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warbrick E (2000) The puzzle of PCNA's many partners. BioEssays 22: 997–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler GS, Sugasawa K, Eker AP, de Laat WL, Hoeijmakers JH (2001) Novel functional interactions between nucleotide excision DNA repair proteins influencing the enzymatic activities of TFIIH, XPG, and ERCC1-XPF. Biochemistry 40: 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Mazloum N, Liu L, Rahmeh A, Li H, Lee MY (2002) Reconstitution and characterization of the human DNA polymerase delta four-subunit holoenzyme. Biochemistry 41: 13133–13142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzhakov A, Kelman Z, Hurwitz J, O'Donnell M (1999) Multiple competition reactions for RPA order the assembly of the DNA polymerase delta holoenzyme. EMBO J 18: 6189–6199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng XR, Jiang Y, Zhang SJ, Hao H, Lee MY (1994) DNA polymerase delta is involved in the cellular response to UV damage in human cells. J Biol Chem 269: 13748–13751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 3