Abstract

The turnover of cholesterol in the brain is thought to occur via conversion of excess cholesterol into 24S-hydroxycholesterol, an oxysterol that is readily secreted from the central nervous system into the plasma. To gain molecular insight into this pathway of cholesterol metabolism, we used expression cloning to isolate cDNAs that encode murine and human cholesterol 24-hydroxylases. DNA sequence analysis indicates that both proteins are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, share 95% identity, and represent a new cytochrome P450 subfamily (CYP46). When transfected into cultured cells, the cDNAs produce an enzymatic activity that converts cholesterol into 24S-hydroxycholesterol, and to a lesser extent, 25-hydroxycholesterol. The cholesterol 24-hydroxylase gene contains 15 exons and is located on human chromosome 14q32.1. Cholesterol 24-hydroxylase is expressed predominantly in the brain as judged by RNA and protein blotting. In situ mRNA hybridization and immunohistochemistry localize the expression of this P450 to neurons in multiple subregions of the brain. The concentrations of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in serum are low in newborn mice, reach a peak between postnatal days 12 and 15, and thereafter decline to baseline levels. In contrast, cholesterol 24-hydroxylase protein is first detected in the brain of mice at birth and continues to accumulate with age. We conclude that the cloned cDNAs encode cholesterol 24-hydroxylases that synthesize oxysterols in neurons of the brain and that secretion of 24S-hydroxycholesterol from this tissue in the mouse is developmentally regulated.

Derivatives of cholesterol§ that contain hydroxyl groups on the side chain are known as oxysterols. Current interest in this class of sterols arises from several postulated roles in cholesterol metabolism. First, oxysterols regulate the expression of many genes involved in lipid and sterol biosynthesis (1, 2). Second, they are substrates for the formation of bile acids (3). Third, the synthesis and secretion of oxysterols by some tissues represents a mechanism of reverse cholesterol transport by which excess sterol is returned from the periphery to the liver for catabolism (4).

Several enzymatically synthesized oxysterols participate in these diverse pathways, including 24S-hydroxycholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol. Of these, potent regulatory properties are ascribed to 24S-hydroxycholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol (1, 2, 5). Both 25-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol are substrates for the formation of bile acids in the liver (6, 7), whereas the synthesis and secretion of 24S-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol are involved in reverse cholesterol transport (4, 8).

The cDNAs for enzymes that synthesize two of these three oxysterols have been isolated. Sterol 27-hydroxylase cDNAs encode mitochondrial cytochrome P450s that convert cholesterol into 27-hydroxycholesterol (9). The gene is expressed in multiple tissues and cell types, and deficiency of sterol 27-hydroxylase in humans results in abnormal bile acid synthesis and an accumulation of sterols in peripheral tissues (10). Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase cDNAs encode a microsomal enzyme that uses a diiron cofactor to catalyze the conversion of cholesterol into 25-hydroxycholesterol (11). Transfection of this cDNA into cultured cells represses cholesterol synthesis and the processing of transcription factors (sterol regulatory element binding proteins) required for the expression of lipid-metabolizing genes (11).

cDNAs encoding cholesterol 24-hydroxylase have not yet been isolated. This enzyme and its product are thought to be particularly important in the brain. A major pathway by which cholesterol homeostasis is maintained in peripheral tissues involves the transfer of excess cholesterol from cells to circulating lipoprotein particles, which subsequently are taken up and catabolized in the liver (12). The presence of the blood-brain barrier prevents this exchange from the central nervous system (13). Instead, an alternate pathway is used in which cholesterol is converted into 24S-hydroxycholesterol, which is readily secreted from the brain into the circulation (13, 14). In the current study, expression cloning and GC-MS are used to identify cDNAs encoding murine and human cholesterol 24-hydroxylases. The tissue distributions and catalytic properties of the encoded enzymes are consistent with a role for 24S-hydroxycholesterol in brain cholesterol homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression Cloning.

Construction of a murine liver cDNA library, preparation of pool DNA, transfection procedures, and assay conditions were as described (11). A positive primary pool containing ≈3,800 recombinants was subdivided into 20 subpools containing ≈750 recombinants each for secondary screening. Tertiary screening consisted of 40 subpools of 30 recombinants and quarternary screening analyzed pools of eight cDNAs derived from a matrix array of individual cDNAs. A single plasmid containing a 24-hydroxylase cDNA was identified and named pCMV-m24.

Isolation of Human Cholesterol 24-Hydroxylase cDNAs.

Three human cDNAs spanning nucleotides 50–2138 were isolated from a fetal brain library (Stratagene, no. 936206) with a murine 24-hydroxylase cDNA probe using standard techniques (15). The 5′ end of the cDNA was isolated by digestion of a human genomic clone containing exon 1 (see below), and thereafter ligated to the 3′ end of the cDNA to produce an expressible, full-length cDNA (plasmid pCMV-h24).

Chemical Analyses.

GC–MS analyses of sterols were carried out as described (11). Concentrations of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in serum and brain were determined by isotope dilution-MS (16). Because 24S-hydroxycholesterol is not a recognized autoxidation product of cholesterol (17), rigorous precautions to exclude air during sample work-up were not taken. Deuterated oxysterol standard (I. Björkhem, Karolinska Institute, Huddinge, Sweden) was added to a defined volume of mouse serum (0.3–1.0 ml) or amount of homogenized brain tissue (250–500 μg protein). The samples were saponified in KOH/ethanol, extracted with chloroform, and purified on Isolute Silica columns. Purified sterols were derivatized to trimethylsilyl ethers and analyzed by electron ionization MS (11). Absolute amounts of 24S-hydroxycholesterol were determined by interpolation from a standard curve generated in each experiment.

Measurement of Cholesterol 24-Hydroxylase Activity in Cells.

Transfection of human embryonic kidney 293 cells, assays for oxysterol synthesis, and treatment with 2% (wt/vol) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin were performed as described (11).

Gene Mapping.

Cholesterol 24-hydroxylase gene sequences were isolated from a murine genomic library prepared from strain 129 SvEv DNA (A. Bradley, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston) and a human genomic library (Stratagene) by screening with mouse or human cDNA probes (15). Six human clones and three mouse clones were obtained. The chromosomal location of the human 24-hydroxylase gene was determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and by PCR amplification of radiation hybrid panel DNAs. FISH mapping was performed by SeeDNA Biotech (Downsview, Ontario, Canada). Two bacteriophage λ clones spanning the entire 24-hydroxylase gene were used as FISH probes. Of 100 mitotic figures analyzed, 94 showed hybridization signals on one pair of chromosomes 14. Comparison of the signal positions with bands generated by staining with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole indicated hybridization to band q32. Radiation hybrid mapping used the Stanford G-3 radiation hybrid panel (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). The primer pair for amplification was 5′-CGTGAGTGTCCGTTGACGTGACCAAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCCGGGCCCTGGGTGGGCACA-3′ (reverse), which, respectively, correspond to nucleotides 1932–1957 and 2042–2021 of the human cDNA sequence (GenBank accession no. AF094480). The thermocycler program consisted of 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 62°C for 15 s, and 70°C for 15 s on a Perkin–Elmer GeneAmp 9600 machine. Analysis of the radiation hybrid data through the Stanford Genome Center server indicated linkage of the 24-hydroxylase gene (CYP46) to the D14S1344 marker (logarithm of odds score = 9.5, cR_1000 = 25.51) on chromosome 14 in the vicinity of band q32.

RNA Blotting.

Murine and human RNA blots (CLONTECH) were hybridized overnight in 50% formamide buffer at 42°C (15). cDNA probes were synthesized by random nonamer priming or by primer extension on bacteriophage M13 subclones. Blots were washed at 65°C in 0.1× SSC containing 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS and exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film at −80°C with an intensifying screen.

Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were perfused through the left ventricle with PBS followed by 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The brain was dissected, fixed for 2–18 h in the same buffer at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 8-μm sections that were mounted on glass slides. An antipeptide antibody (T623) was raised in rabbits (18) against the sequence GKDWVQRRREALKRGED, representing amino acids 254–270 of the murine 24-hydroxylase, affinity-purified (18), and incubated at 10 μg/ml with slides for 2 h at 23°C. The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antiserum (diluted 1:50, Amersham Pharmacia). A TSA-Indirect kit (DuPont/NEN) was used for amplification, and visualization was via 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (red) or diaminobenzidine/metal (brown/black) kits (Pierce).

In Situ mRNA Hybridization.

Sense and antisense murine 24-hydroxylase RNA probes were synthesized by using a Riboprobe T7 Synthesis kit (Promega) with [33P]UTP (Amersham Pharmacia, >2,500 Ci/mmol) and [33P]CTP (DuPont/NEN, 2,000–4,000 Ci/mmol). The probe was hydrolyzed before hybridization (19). In situ mRNA hybridization was performed as described (20), except protease XXIV (Sigma) at a concentration of 300 μg/ml was substituted for proteinase K and the acetylation step was omitted. Protease digestion time was 8 min. Tissue sections were examined under light-field and dark-field illumination by using a Nikon Eclipse E-1000 microscope.

Immunoblotting.

Gel electrophoresis was carried out as described (21). Separated proteins were electroblotted to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes and incubated with T-623 antiserum (0.3 μg/ml for affinity-purified serum; 1:2,000–1:10,000 dilution for unpurified serum). A donkey anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Amersham Pharmacia) was used as secondary antibody. Visualization was via enhanced chemiluminescence kits (Amersham Pharmacia).

Ontogeny Studies.

Whole mouse brains (C57/Bl6–129SvEv mixed strain) were dissected and homogenized in 25 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4/0.25 M sucrose/1 mM EDTA, and membranes were prepared by sequential centrifugation. Samples (30 μg microsomal protein) were analyzed by immunoblotting. Human frontal lobe brain specimens (5–25 g) were obtained at autopsy and within 24 h of death from individuals ranging in age from 3 months to 72 years and of both sexes. A single specimen was obtained from a 20-week gestation fetus. Tissue containing both white and gray matter was homogenized in PBS, and aliquots (50 μg protein) were analyzed by immunoblotting.

RESULTS

To isolate a murine cDNA encoding cholesterol 24-hydroxylase, pools of cDNAs from a library constructed with hepatic mRNA from a sterol regulatory element binding protein 1a-transgenic mouse (22) were transfected into cultured 293 cells. This line of transgenic mice excretes large amounts of fecal oxysterols (unpublished observations) and was predicted to be an enriched source of mRNAs encoding oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes. cDNAs encoding an oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase enzyme and the adenovirus VA1 RNA were cotransfected with the cDNA library pools. The oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase cDNA was added to convert oxysterol products to their 7α-hydroxylated forms, which are readily separated from cholesterol by TLC (11). The VA1 gene was added to enhance expression of transfected cDNAs (23). After introduction of this plasmid mixture into cells, [14C]cholesterol was added to the medium for 60 h and conversion into 7α-hydroxylated 24S-hydroxycholesterol was determined. Screening of 106 cDNAs produced a single clone that encoded a putative cholesterol 24-hydroxylase activity.

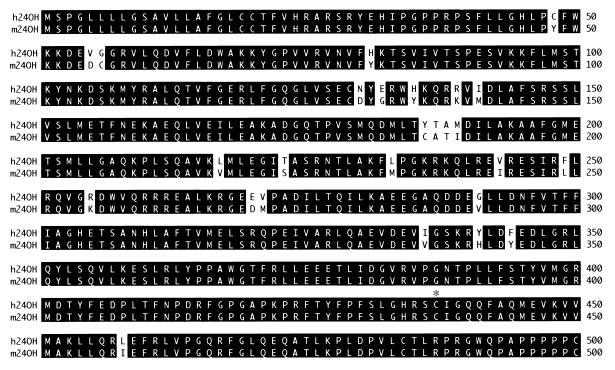

This murine cDNA was used as a hybridization probe to isolate the corresponding human cDNA from a fetal brain library. Fig. 1 shows an alignment of the cDNA-deduced sequences of the 24-hydroxylase enzymes. Both proteins contain 500 aa, share a high degree of sequence identity (95%), and are microsomal members of the cytochrome P450 superfamily. The 24-hydroxylases share less than 35% identity with other P450s and thus represent a new subfamily of these enzymes (24), designated Cyp46 in the mouse and CYP46 in the human (D. Nelson and D. Nebert, personal communication). Several expressed sequence tags corresponding to the murine cDNA (e.g., GenBank accession nos. R75216, AA096922, and R75217) and the human cDNA (e.g., GenBank accession nos. AA961615, AA760981, R36281, and H16164) were present in the database.

Figure 1.

Alignment of murine and human cholesterol 24-hydroxylase protein sequences. The cDNA-deduced sequences of the enzymes are shown in single-letter code with identical residues highlighted in black. Amino acids are numbered on the right. An asterisk above the alignment marks a cysteine residue (position 437) conserved in P450 enzymes. The GenBank accession numbers for the murine and human cDNAs are AF094479 and AF094480, respectively.

Full-length murine and human cDNAs were transfected into 293 cells, and the encoded enzymatic activities were measured. Incubation of transfected cells with radio-labeled cholesterol resulted in the time-dependent synthesis of two sterol products that migrated slower than cholesterol on TLC plates (Fig. 2A). Treatment of transfected cells with 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin before addition of radio-labeled cholesterol led to as much as a 10-fold increase in product formation (Fig. 2A). This compound is postulated to extract sterols from cellular membranes (25), and in these experiments may stimulate 24-hydroxylase enzyme activity by removing unlabeled cholesterol that otherwise competes with the exogenously added, radio-labeled substrate.

Figure 2.

Expression of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase cDNAs in cultured cells. (A) The indicated expression plasmid was transfected into 293 cells by lipofection. Some cells (+) were treated before substrate addition for 1 h with 20 mg/ml 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin to remove cholesterol from membranes. Thereafter, fresh medium containing radio-labeled substrate was added and the incubation continued for 4, 8, or 24 h. Sterols were extracted from the media and separated by TLC, and the plates were subjected to PhosphorImage analysis to determine the % conversion of substrate into products. A photograph of a typical experiment is shown in the center. Sterol standards are marked on the left. The calculated % conversion for each lane is shown at the bottom. (B) Chemical analyses of 24-hydroxylase products. Cultured 293 cells were transfected with vector alone or a murine 24-hydroxylase expression plasmid (pCMV-m24) as described above except that the posttransfection media was supplemented with 10 μg/ml cholesterol. After 48 h, sterols were extracted from the media, purified by silica chromatography, derivatized to trimethylsilyl ethers, and subjected to GC-MS. (Left) GC profiles of sterols extracted from the media of mock-transfected cells (Upper) or expression vector-transfected cells (Lower). (Right) Ionization spectra of authentic 24R/S-hydroxycholesterol standard (Upper) and the sterol product eluting at 22.33 min from the GC obtained with transfected cell medium (Lower).

The chemical structures of the products synthesized from cholesterol in transfected cells were determined by GC-MS. GC analysis revealed two compounds eluting from the column at 22.33 and 22.56 min that were not present in the medium of mock-transfected cells (Fig. 2B, Left). Ionizing MS analysis of the product eluting at 22.33 min produced a spectrum that was virtually identical to an authentic 24R/S-hydroxycholesterol standard (Fig. 2B, Right). The stereochemistry of the hydroxyl group at carbon 24 of the product was not determined but is assumed to be in the 24S configuration. The S-conformer is the only known naturally occurring (32) and active (5) isomer of 24-hydroxycholesterol. Analysis of the product eluting at 22.56 min generated a spectrum consistent with that determined previously for 25-hydroxycholesterol (ref. 11 and data not shown). The ratio of 24S-hydroxycholesterol to 25-hydroxycholesterol products in the transfected cells was ≈4:1 as calculated by PhosphorImage analyses.

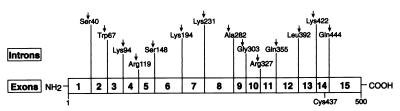

The murine and human cholesterol 24-hydroxylase genes were isolated from genomic DNA libraries by hybridization screening. DNA sequencing revealed that each gene contained 15 exons and 14 introns (Fig. 3). The positions of the introns relative to the predicted amino acid sequence of the proteins were exactly the same in both genes. Fluorescent in situ hybridization and radiation hybrid panel mapping localized the human gene (CYP46) to chromosome 14q32.1.

Figure 3.

Structure of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase gene. The positions of introns and exons in the gene are indicated on a schematic of the protein. A conserved amino acid (Cys-437) that is postulated to be the sixth ligand of the heme cofactor is shown below the drawing. Introns interrupt codons of the murine and human 24-hydroxylase genes at the same positions.

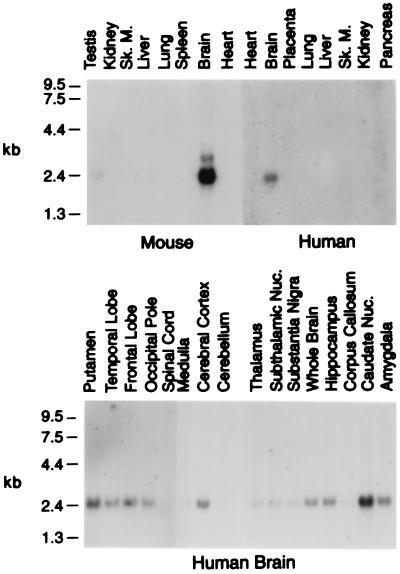

The tissue-specific expression patterns of the cholesterol 24-hydroxylase genes were determined by RNA blotting. In the mouse, the highest levels of mRNA were in the brain, with much lower levels detected in the testis and liver (Fig. 4). In agreement with this distribution, semiquantitative immunoblotting indicated that there was approximately 100 times more 24-hydroxylase protein per gram of brain than liver (data not shown). No 24-hydroxylase protein was found in testis extracts. Of 16 human tissues screened, only the brain exhibited detectable levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA (Fig. 4, and data not shown). Analysis of RNA isolated from different regions of the human brain (Fig. 4) indicated that the 24-hydroxylase mRNA was broadly distributed, with somewhat higher levels in zones rich in gray matter (e.g., putamen, cerebral cortex, and caudate nucleus) and lower levels in regions rich in white matter (e.g., corpus callosum).

Figure 4.

Tissue distribution of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase mRNAs in mouse and human. Multiple tissue blots containing 2 μg of polyadenylated RNA from the indicated organs were subjected to hybridization using radio-labeled 24-hydroxylase cDNA probes. The positions of RNA standards are shown on the left. The murine and human RNA blots were exposed to film for 5 and 7 days, respectively.

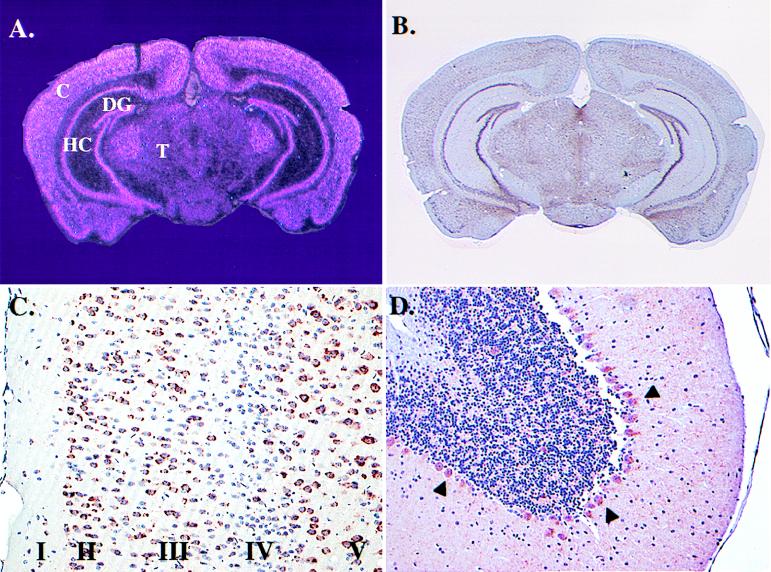

In situ mRNA hybridization and immunohistochemistry were used to determine which cell types express cholesterol 24-hydroxylase in the murine brain. Analysis of coronal sections revealed abundant 24-hydroxylase mRNA in neurons of the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, dentate gyrus, and thalamus (Fig. 5A). A similar distribution of 24-hydroxylase protein was detected in adjacent sections with an antipeptide antibody probe (Fig. 5B). Analysis of immunohistochemically stained sections at high magnification localized the 24-hydroxylase protein to neurons in all six layers of the cortex, with the highest levels in pyramidal cells of cortical layers II, III, and V (Fig. 5C), as well as layer VI (data not shown). Lower amounts of 24-hydroxylase protein were detected in cortical layer IV, which is rich in nonpyramidal cells (Fig. 5C). Although blotting of mRNA isolated from the cerebellum showed little 24-hydroxylase signal (Fig. 4), immunohistochemical analyses revealed extensive staining of cerebellar Purkinje cell bodies (Fig. 5D, arrowheads) and in neurons of deep cerebellar nuclei (data not shown). Expression in both of these cerebellar cell types was confirmed by in situ mRNA hybridization. At very high magnification, a majority of 24-hydroxylase immunoreactive material was detected in a perinuclear distribution within the nerve cell body consistent with a microsomal localization. Lower levels were present in dendritic trees of cerebellar Purkinje cells (Fig. 5D), as well as those of other neurons as judged by costaining with an antibody directed against a neurofilament protein (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Cell type specific expression patterns of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase in murine brain. Coronal sections were subjected to in situ mRNA hybridization analysis using a 33P-labeled RNA probe (A) or immunohistochemical analyses using an antipeptide antibody probe (B-D). (A) Light pink mRNA hybridization signals reveal an expression pattern consistent with neurons in the cortex (C), hippocampus (HC), dentate gyrus (DG), and thalamus (T). Magnification = ×0.5. (B) A similar pattern of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase protein is revealed at the same magnification by dark purple signal. (C) A photomicrograph of the cortical region of the brain taken at higher magnification (×10). Individual pyramidal neurons in layers I, II, III, and V contain dark red signal indicative of 24-hydroxylase protein. Smaller nonpyramidal cells concentrated in cortical layer IV contain little or no detectable signal. (D) Staining of 24-hydroxylase protein in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum (arrowheads). Signal is also present in the dendritic trees of Purkinje cells. Magnification = ×2.

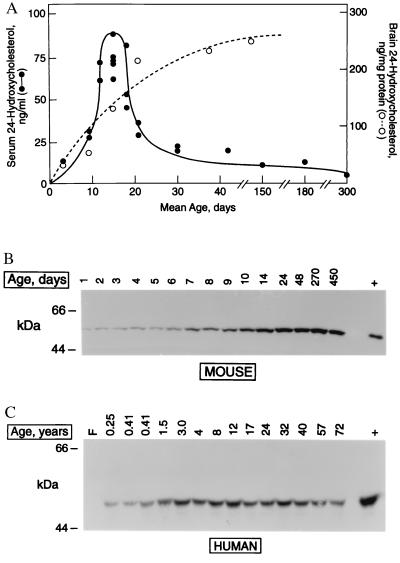

We examined the ontogeny of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase expression in the mouse by measuring product and enzyme levels in animals of different ages. Data from isotope dilution MS experiments indicated that serum 24S-hydroxycholesterol levels were low in newborn mice, reached peak concentrations of approximately 75 ng/ml during postnatal days 12–15, and thereafter decreased (Fig. 6A). In contrast, 24S-hydroxycholesterol levels in brain increased linearly between postnatal days 3 and 30 and thereafter reached a plateau of approximately 250 ng/μg brain protein (Fig. 6A). Immunoblotting of brain membrane fractions revealed that levels of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase protein also increased linearly with age (Fig. 6B) and closely matched the increase in brain 24S-hydroxycholesterol (compare Fig. 6 A with B).

Figure 6.

Expression of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase as a function of age. (A) Ontogeny of serum and brain 24S-hydroxycholesterol in mice. Sterol levels were measured by isotope dilution GC-MS in sera and tissues from animals of the indicated ages. For days 3–30, each point represents a separate measurement in pooled sera from multiple animals (n = 3–10). For days 42–300, each point represents a measurement in a single animal. Serum levels (●), brain levels (○). (B) Ontogeny of 24-hydroxylase protein expression in murine brain. Aliquots (30 μg) of membrane protein prepared from animals of the indicated ages were immunoblotted with an antipeptide antibody directed against 24-hydroxylase. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Size standards are indicated on the left. The lane marked + is a control containing lysate (5 μg protein) from 293 cells transiently transfected with a murine 24-hydroxylase expression plasmid (pCMV-m24). (C) Ontogeny of 24-hydroxylase protein expression in human brain. Aliquots of total cell protein (50 μg) were prepared from individuals of the indicated ages and analyzed by immunoblotting as described in B. Size standards are indicated on the left. The lane marked + is a control containing lysate (1 μg protein) from 293 cells transiently transfected with a human 24-hydroxylase expression plasmid (pCMV-h24) mixed with 50 μg of total cell protein from a frontal lobe specimen of a 24-year-old individual.

Serum 24S-hydroxycholesterol levels in humans are highest in the first decade of life and then decline with age (8). To determine whether the expression of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase enzyme correlated with these measurements, membrane proteins prepared from forebrain were subjected to immunoblotting. The 24-hydroxylase protein was undetectable in a fetal sample, was present at low levels in subjects less than 1 year of age, and was detected at high levels between the ages of 1.5 and 72 years (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

The isolation and characterization of cDNAs encoding murine and human cholesterol 24-hydroxylases are reported in this paper. These enzymes contain 500 aa, share 95% sequence identity, and represent a new subfamily (CYP46) of cytochrome P450 proteins. Transfection of the cDNAs into cultured cells confers an ability to convert cholesterol into 24S-hydroxycholesterol, and to a lesser extent, 25-hydroxycholesterol. The genes that specify 24-hydroxylase in the mouse and human have identical intron-exon structures, and they are preferentially transcribed in the brain. 24-Hydroxylase is expressed in the neurons of many subregions of the brain, and this expression appears to begin at birth and to continue throughout life.

As cytochrome P450 enzymes, the cholesterol 24-hydroxylases share conserved features with other microsomal members of this superfamily, including a generalized hydrophobicity (46% of amino acids), a conserved cysteine ligand that binds the heme cofactor (residue 437), and an ability to hydroxylate a hydrophobic substrate (Fig. 2). However, the murine and human 24-hydroxylases are distinguished from other P450s by several unique attributes. First, they share 95% sequence identity, compared with an average of only 77% identity for 10 randomly chosen murine-human P450 orthologue pairs (1B1, 2E1, 4B1, 5A1, 7A, 7B, 11B2, 19A, 21, and 27). Second, the 24-hydroxylase genes each contain 15 exons, which is a large number of exons compared with other mammalian P450 genes (24). Third, unlike most P450s (26), 24-hydroxylase is present at very low levels in the liver and appears to be preferentially expressed in the brain as judged by RNA blotting (Fig. 4), in situ mRNA hybridization and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5), immunoblotting (Fig. 6), and enzyme activity (27).

Several current findings suggest the cloned cDNAs encode enzymes that synthesize 24S-hydroxycholesterol in brain. First, translation of the cDNA sequences predicts that the 24-hydroxylases are cytochrome P450s (Fig. 1), which is consistent with the requirements of NADPH and oxygen for the formation of 24S-hydroxycholesterol by brain microsomes (13, 28). Second, molecular and immunochemical probes reveal high-level expression of 24-hydroxylase in brain (Figs. 4 and 5). Third, ontogeny studies show a gradual accumulation of 24-hydroxylase in brain as a function of age (Fig. 6 B and C), which parallels a temporal increase of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in this tissue (Fig. 6A). Finally, we measured serum 24-hydroxycholesterol levels in the sera and brains of mice homozygous for an induced null allele in the 24-hydroxylase gene (Cyp46−/− genotype) (the generation and characterization of mice lacking Cyp46 will be reported elsewhere by E.G.L. and D.W.R.). On day 15, when circulating 24-hydroxycholesterol levels ranged between 60 and 90 ng/ml in wild-type mice (Fig. 6A), a level of 11 ng/ml was measured in the sera of Cyp46−/− animals. More importantly, brain 24-hydroxycholesterol levels were 131 ng/mg protein in wild-type mice on day 15 (Fig. 6A) but were undetectable in this tissue from age-matched Cyp46−/− animals. There were no differences in brain 25-hydroxycholesterol levels between wild-type and knockout mice, thus the observed in vitro production of this oxysterol in cells transfected with 24-hydroxylase cDNAs (Fig. 2) most likely reflects a consequence of overexpression rather than a physiologically relevant property of the enzyme. Taken together, these observations lead us to believe that the cloned cDNAs specify authentic brain cholesterol 24-hydroxylases.

The unique and conserved features of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase imply that the enzyme and its product play important roles in brain cholesterol metabolism. One such role may involve the conversion of excess cholesterol into 24S-hydroxycholesterol, which is readily secreted across the blood-brain barrier into the circulation (27). This hypothesis is supported by the tissue-specific accumulation and synthesis of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in brain (8, 28, 29), the observation that the rate of excretion of this compound into the plasma roughly equals the rate of cholesterol synthesis in the adult brain (13), and by the fact that once synthesized and excreted from the central nervous system, 24S-hydroxycholesterol is rapidly taken up by and metabolized in the liver (27). However, a more diverse role for 24-hydroxylase and its product are suggested by two findings reported here. First, the enzyme is expressed in neurons rather than the cholesterol-laden support cells or their lipid-rich myelin sheaths (Fig. 5, ref. 30). Second, 24-hydroxylase is produced in some, but not all, neurons (Fig. 5), implying a select function in certain subclasses of this cell type.

The marked differences that we observe between circulating 24-hydroxycholesterol levels and expression of the biosynthetic enzyme may be related to a more extended role for 24-hydroxylase in the brain. At a time when serum levels of this sterol are high in the mouse (postnatal days 12–15, Fig. 6A), the synthesis of cholesterol and other lipids involved in myelination is elevated (31). The increase in production and secretion of 24-hydroxycholesterol at this time may reflect a dual role for the oxysterol as both a vehicle for reverse cholesterol transport and as a mediator of intercellular signaling between neurons and support cells. Similarly, the lack of correlation between enzyme and serum product levels in adults may indicate an exclusive role for the oxysterol as a localized regulator of cholesterol homeostasis or of brain function.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Davis, M. McKelvey, and K. Richardson-Hagen for technical assistance and H. Hobbs, J. Goldstein, and R. Estabrook for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL 20948), the Robert A. Welch Foundation (I-0971), the Henning and Johan Throne-Holst Foundation for Nutrition Research, and the Foundation BLANCEFLOR Boncompagni-Ludovisi, nee Bildt.

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AF094479 and AF094480).

Trivial names used are: cholesterol, 5-cholesten-3β-ol; 24-hydroxycholesterol, cholest-5-ene-3β,24-diol; 25-hydroxycholesterol, cholest-5-ene-3β,25-diol; 27-hydroxycholesterol, cholest-5-ene-3β,27-diol.

References

- 1.Kandutsch A A, Chen H W. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6057–6061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M S, Goldstein J L. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7306–7314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danielsson H. Adv Lipid Res. 1963;1:335–385. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9937-5.50015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björkhem I, Andersson O, Diczfalusy U, Sevastik B, Xiu R, Duan C, Lund E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8592–8596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janowski B A, Willy P J, Devi T R, Falck J R, Mangelsdorf D J. Nature (London) 1996;383:728–731. doi: 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toll A, Wikvall K, Sudjana-Sugiaman E, Kondo K, Björkhem I. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin K O, Budai K, Javitt N B. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lütjohann D, Breuer O, Ahlborg G, Nennesmo I, Siden A, Diczfalusy U, Björkhem I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9799–9804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson S, Davis D L, Dahlbäck H, Jörnvall H, Russell D W. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8222–8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cali J J, Hsieh C, Francke U, Russell D W. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7779–7783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund E G, Kerr T A, Sakai J, Li W-P, Russell D W. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34316–34348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glomset J A. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björkhem I, Lütjohann D, Breuer O, Sakinis A, Wennmalm A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30178–30184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Y Y, Smith L L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;348:189–196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(74)90230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzeletovic S, Breuer O, Lund E, Diczfalusy U. Anal Biochem. 1995;225:73–80. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith L L. Chem Phys Lipids. 1987;44:87–125. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(87)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan B, Beddington R, Costantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating The Mouse Embryo. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman D M, Russell D W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9359–9363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakai J, Nohturfft A, Cheng D, Ho Y K, Brown M S, Goldstein J L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20213–20221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimano H, Horton J D, Hammer R E, Shimomura I, Brown M S, Goldstein J L. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1575–1584. doi: 10.1172/JCI118951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider R J, Shenk T. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:317–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson D R, Koymans L, Kamataki T, Stegeman J J, Feyereisen R, Waxman D J, Waterman M R, Gotoh O, Coon M J, Estabrook R W, et al. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:1–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilsdonk E P C, Yancey P G, Stoudt G W, Bangerter F W, Johnson W J, Phillips M C, Rothblat G H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17250–17256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedlund E, Gustafsson J-A, Warner M. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:82–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Björkhem I, Lütjohann D, Diczfalusy U, Stahle L, Ahlborg G, Wahren J. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1594–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhar A K, Teng J I, Smith L L. J Neurochem. 1973;21:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb04224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ercoli A, De Ruggieri P. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:3284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Susuki K. In: Basic Neurochemistry. Siegel G J, Albers R W, Katzman R, Agranoff B W, editors. Brown, Boston: Little; 1976. pp. 308–328. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uzman L L, Rumley M K. J Neurochem. 1958;3:170–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1958.tb12624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saucier S E, Kandutsch A A, Gayen A K, Swahn D K, Spencer T A. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6863–6869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]