Abstract

C-1027 is an enediyne antitumor antibiotic composed of four distinct moieties: an enediyne core, a deoxy aminosugar, a β-amino acid, and a benzoxazolinate moiety. We now show that the benzoxazolinate moiety is derived from chorismate by the sequential action of two enzymes—SgcD, a 2-amino-2-deoxyisochorismate (ADIC) synthase and SgcG, an iron–sulfur, FMN-dependent ADIC dehydrogenase—to generate 3-enolpyruvoylanthranilate (OPA), a new intermediate in chorismate metabolism. The functional elucidation and catalytic properties of each enzyme are described, including spectroscopic characterization of the products and the development of a fluorescence-based assay for kinetic analysis. SgcD joins isochorismate (IC) synthase and 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate (ADC) synthase as anthranilate synthase component I (ASI) homologues that are devoid of pyruvate lyase activity inherent in ASI; yet, in contrast to IC and ADC synthase, SgcD has retained the ability to aminate chorismate identically to that observed for ASI. The net conversion of chorismate to OPA by the tandem action of SgcD and SgcG unambiguously establishes a new branching point in chorismate metabolism.

Keywords: 2-amino-2-deoxyisochorismate dehydrogenase, 2-amino-2-deoxyisochorismate synthase, 3-enolpyruvoylanthranilate

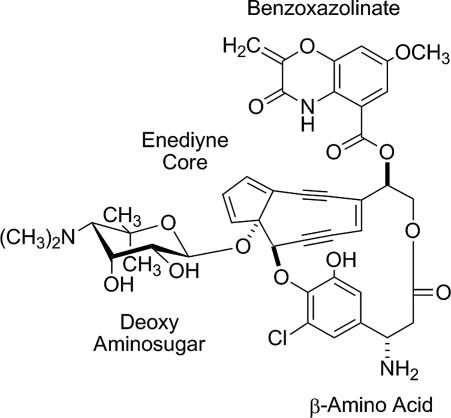

C-1027 is an enediyne antitumor antibiotic that is one of the most cytotoxic natural products ever discovered (1). It is isolated from Streptomyces globisporus as a noncovalent apo-protein (CagA)–chromophore complex (2), with the chromophore consisting of four distinct covalently appended moieties: an enediyne core, a deoxy aminosugar, a β-amino acid, and a benzoxazolinate moiety (Fig. 1) (3). Although the enediyne core is directly implicated in the generation of a benzenoid diradical that is capable of abstracting hydrogen atoms from DNA leading to double-stranded DNA breaks (4), the other moieties of C-1027 are critical in enhancing the bioactivity. This is clearly exemplified with the benzoxazolinate moiety, which specifically binds to CagA, hence providing stability to the enediyne core (5, 6), and is essential for both binding and intercalating the minor groove of DNA (7).

Fig. 1.

Structure of C-1027 with four distinct structural moieties.

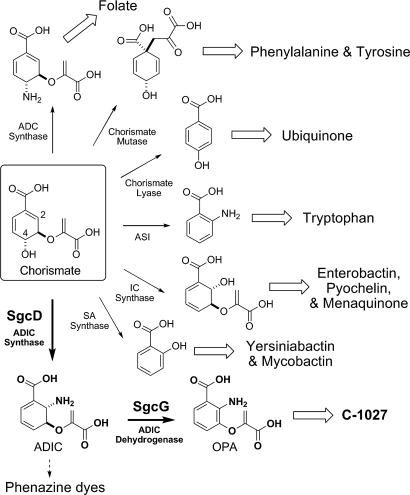

The biosynthetic precursor for the benzoxazolinate moiety of C-1027 was initially proposed to be chorismate based on the uncovering of proteins homologous to anthranilate synthase (AS) components I and II that are located within the biosynthetic gene cluster (8). ASI, typically annotated as TrpE, catalyzes the first committed step in Trp biosynthesis—the conversion of chorismate to anthranilate—whereas ASII (TrpG) provides the amine, using glutamate as the donor (9). In addition to the Trp biosynthetic pathway, chorismate is also the branch point for minimally five other pathways found in primary and secondary metabolism, the majority of which are initiated by ASI homologues (Fig. 2). This includes 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate (ADC) synthase (10), the first step in folate biosynthesis; isochorismate (IC) synthase (11, 12), the first step in enterobactin, pyochelin, and menaquinone biosynthesis; and salicylic acid (SA) synthase (13, 14), an enzyme family involved in the production of the yersiniabactin and mycobactin. Two distinct chorismate-using families that have no significant sequence homology to ASI are also known; chorismate lyase (15), the first enzyme in ubiquinone biosynthesis, and chorismate mutase (16), the first enzyme in Phe and Tyr biosynthesis.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic branching points from chorismate. ADC, 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate; ASI, anthranilate synthase component I; IC, isochorismate; SA, salicylic acid; ADIC, 2-amino-2-deoxyisochorismate; OPA, 3-enolpyruvoylanthranilate.

The reaction catalyzed by ASI is the composite of two enzymatic steps: a reversible 1,5-substitution involving amine addition at C2 of chorismate with concomitant loss of the hydroxyl group at C4 to yield trans-6-amino-5-[1-carboxyethenyl)oxy]-1,3-cyclo-hexadiene-1-carboxylic acid, commonly known as 2-amino-2-deoxyisochorismate (ADIC), followed by irreversible pyruvate elimination to form anthranilate. The overall reaction coordinate is known to proceed with ADIC as an enzyme bound intermediate, as deduced from (i) the conversion of synthetic ADIC to anthranilate (17, 18) and (ii) transient accumulation of small amounts of ADIC from a Salmonella typhimirium ASI (H398M) mutant (19). Although the crystal structures for ASI (20–22), SA synthase (13, 23), IC synthase (24), and ADC synthase (25) in combination with mechanistic studies on ASI, ADC synthase, and IC synthase (26–28) have provided clear insights into the nature of the nucleophile addition/elimination step (e.g., the ADIC synthase activity of ASI), the identification of the catalytic residues essential for pyruvate lyase activity have remained enigmatic. For instance, although the ASI (H398M) mutant accumulated ADIC, the conversion reached a maximum of only 15 mol % of the starting chorismate, activity was decreased to ≤1% of wild-type activity, and ultimately all ADIC was converted to anthranilate (19).

Here, we report the functional assignment of the first two enzymes involved in the benzoxazolinate biosynthesis: the ASI homologue SgcD and a putative iron–sulfur ([Fe–S]) flavin-dependent oxidoreductase SgcG. The results establish SgcD as a naturally occurring ADIC synthase and that SgcD completely lacks pyruvate lyase activity, results that were not readily predicted from sequence comparisons and homology-based structural modeling. Despite proposals for such an activity during phenazine dye biosynthesis (29, 30), to our knowledge this is the first biochemical characterization for such an enzyme. In addition, SgcG is shown to be an ADIC dehydrogenase, converting ADIC to a new metabolite, 3-O-enolpyruvoylanthranilic acid (OPA), thereby providing additional evidence to support the functional assignment of SgcD and establishing that the pyruvate is likely retained during the biosynthesis of the benzoxazolinate. Thus, the tandem action of SgcD and SgcG to afford OPA represents a new branching point in chorismate metabolism, bringing the total to minimally seven divergent pathways (Fig. 2). Finally, the results have enabled us to revise the biosynthetic events leading to the benzoxazolinate moiety of C-1027, and the newly formulated pathway is presented.

Results

Bioinformatics Analysis.

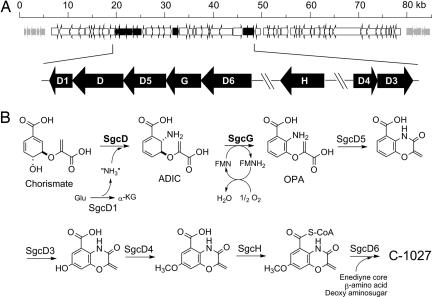

The sgcD gene resides in a putative operon containing five subclustered ORFs predicted to be involved in benzoxazolinate biosynthesis (Fig. 3A). SgcD has ≤38% sequence identity to several putative ASI enzymes that are annotated primarily from genome sequencing projects. The closest functionally characterized homologues are S. typhimirium ASI (28/39; percentage of identity/percentage of similarity) (9, 20), Escherichia coli ASI (27/38) (31), and Serratia marcescens ASI (26/38) (21). Based on the structure analysis of S. marcescens and S. typhimirium ASI (20, 21), the active site amino acids involved in binding of benzoate, pyruvate, and Mg2+ and the aforementioned H398 residue are conserved in SgcD [supporting information (SI) Figs. 6 and 7 and SI Table 1]. In contrast, residues found essential for Trp feedback inhibition in S. typhimirium ASI (32) are not conserved, with three substitutions found in SgcD (E39A, S40E, and C465A; numbering refers to S. typhimirium ASI) that likely compromise feed-back inhibition (see below).

Fig. 3.

Biosynthesis of the benzoxazolinate moiety of C-1027. (A) Schematic of the C-1027 genetic locus with the eight putative ORFs identified by using BLAST analysis, including the sgcD/sgcG subcluster. (B) The enzymatic steps for the conversion of chorismate to the benzoxazolinate moiety. Highlighted in bold are the two reactions characterized in this study. Glu, glutamate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; FMN, flavin-mononucleotide; other abbreviations are defined in Fig. 2.

Within the putative operon and separated from sgcD by a single ORF is sgcG, the gene product of which is most similar to the Isf family of iron–sulfur flavoproteins (33). The function of these proteins remains unclear, however, the closely related WrbA family, which also have high sequence similarity but lack the iron–sulfur motif, have been shown to be functional as NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases (34). The N terminus of Isf and WrbA proteins contain a flavodoxin-like domain, and this motif is conserved in SgcG. In addition, like Isf, SgcG is predicted to contain a [Fe–S] cluster with all four Cys found in SgcG involved in iron coordination (SI Fig. 8).

Overproduction and Properties of SgcD and SgcG.

The genes for SgcD and SgcG were cloned into pET-30 Xa/LIC and expressed in E. coli. The recombinant proteins were partially soluble and obtained in good yields after purification using Ni-affinity chromatography. Denaturing SDS/PAGE yielded protein band sizes consistent with the predicted molecular mass of SgcD (58.5 kDa) and SgcG (29.1 kDa) (SI Fig. 9).

SgcG was purified as a yellow-brown solution. The ultraviolet–visible (UV/Vis) spectrum of the purified protein was reminiscent of a flavin cofactor (SI Fig. 10A), and HPLC analysis of heat denatured protein revealed FMN copurified with SgcG (SI Fig. 10B). The ratio varied from 1:20 to 1:50 (mol FMN:mol SgcG) between enzyme preparations. In addition, SgcG was routinely copurified with Fe2+ at a stoichiometry of 1:2 (mol Fe2+:mol SgcG) based on the colorimetric assay with ferrozine (35). Preliminary attempts to detect inorganic sulfide yielded an identical stoichiometry of 1:2 (mol S2−:mol SgcG) (36).

Activity of SgcD.

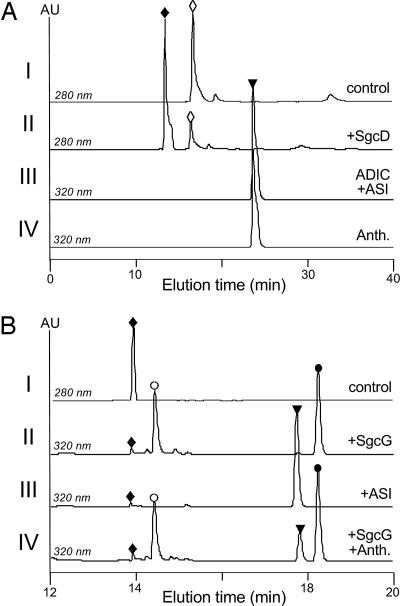

Initial activity tests of SgcD were performed with standard conditions used for ASI (31). HPLC was used to monitor SgcD activity, and a new peak appeared eluting before chorismate (Fig. 4A). Importantly, no anthranilate was detected by HPLC. The new peak was collected and analyzed by ESI-MS to give a [M+H]+ ion at m/z = 226.0 (calculated m/z = 226.1), consistent with the molecular formula C10H11NO5. In addition, UV/Vis and NMR spectroscopic analysis revealed identical spectra to that observed for synthetic and enzymatically prepared ADIC (SI Text) (19).

Fig. 4.

HPLC analysis of SgcD and SgcG reactions. (A) HPLC profiles of chorismate incubated with boiled SgcD (I), chorismate incubated with SgcD (II), the purified SgcD product ADIC incubated with E. coli ASI (III), and anthranilate standard (IV). (B) HPLC profiles of authentic ADIC (I), ADIC incubated with SgcG (II), ADIC incubated with ASI (III), and ADIC incubated with SgcG and spiked with authentic anthranilate (IV). Open diamonds, chorismate; filled diamonds, ADIC; open inverted triangles, anthranilate; open circles, FMN; filled circles, OPA. Anth., anthranilate; other abbreviations are defined in Fig. 2.

To provide further evidence that ADIC was the product of SgcD, E. coli ASI was cloned and the gene product purified by using standard conditions. Upon incubation of the purified-SgcD product with recombinant ASI, the peak corresponding to the SgcD product disappeared, and a new peak was detected with an identical retention time and UV/Vis spectrum to authentic anthranilate (Fig. 4A). This reaction proceeded in an identical manner to that described in refs. 17–19, and thus the data suggest that SgcD is indeed an ADIC synthase.

Properties of SgcD Using an HPLC assay.

General characteristics of SgcD were determined by using HPLC end-point assays under initial velocity conditions. Similar to ASI, an exogenous amine source was necessary for product formation, and ammonium salts could readily substitute for the amidotransferase activity of ASII (19). Similarly to ASI, SgcD activity depended on the inclusion of Mg2+. Finally, in contrast to most ASI homologues (20, 37), Trp did not inhibit the formation of ADIC, a result that is not surprising considering the observed amino acid substitutions in SgcD that are necessary for feedback inhibition (32).

SgcG Activity and Product Characterization.

HPLC was used to assess SgcG activity with purified ADIC and excess FMN as the cosubstrate. A new peak appeared with the simultaneous loss of the ADIC peak, and this new peak had a similar retention time and UV/Vis profile to anthranilate (Fig. 4B). However, coinjections with authentic anthranilate revealed that SgcG formed a distinct product. The new peak was collected and analyzed by high-resolution (HR) electron spray ionization (ESI) mass spectra (MS) to yield an [M+H]+ ion of m/z = 224.0541 (calculated m/z = 224.0481), consistent with the formation of OPA. The UV/Vis spectrum of OPA exhibited two absorption maxima at λmax 218 and 335 nm with a shoulder at 245 nm in MeOH. The extinction coefficient was calculated as ε335 nm = 3,970 ± 50 M−1·cm−1. Analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum confirmed the presence of three aryl and two vinylic protons, and complete 2D spectroscopic experiments were consistent with the structural assignment of OPA as the product of SgcG (SI Text).

Properties of SgcG Using an HPLC Assay.

Time course analysis by using HPLC to monitor activity showed that the rate of OPA formation depended on the concentration of SgcG. Under anaerobic conditions, the reaction proceeded by using quantitative amounts of ADIC and FMN, consistent with FMN as the sole cosubstrate and is reoxidized by molecular oxygen under the standard reaction conditions. Finally, no changes in activity were observed during attempts to reconstitute the [Fe–S] cluster following the procedure described for Isf (38).

Assay Development for Kinetic Analysis.

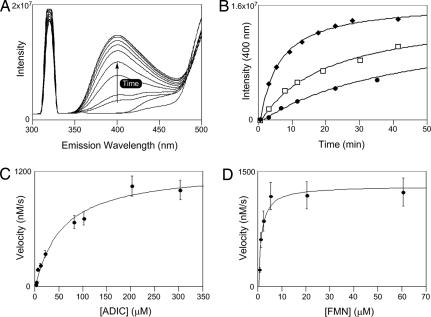

A continuous fluorescence-based assay was developed to obtain steady-state kinetic data for SgcG (Fig. 5). A hypsochromic shift for OPA was observed to λmax = 316 nm in aqueous solutions (pH 8.0); therefore, fluorescence was monitored by using an excitation wavelength of 316 nm and emission at 400 nm. A standard curve was prepared by using enzymatically prepared OPA, and real-time SgcG reactions revealed a time-dependent increase in emission at 400 nm as excepted (Fig. 5 A and B). This increase at 400 nm correlated well with HPLC-based detection (data not shown). Using this fluorescence assay, single-substrate kinetic constants were determined (Fig. 5 C and D). Activity assays with saturating FMN and variable ADIC displayed standard Michaelis–Menten kinetics yielding a KM = 56 ± 12 μM and kcat = 15 ± 3 s−1, whereas assays with saturating ADIC and variable FMN gave a KM = 1.2 ± 0.4 μM and kcat = 17 ± 4 s−1.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic analysis of SgcG. (A) Fluorescence-based assay development for SgcG with an excitation at 316 nm and emission at 400 nm. Each line represents a wavelength scan at different time points ranging from 0 to 50 min. (B) Time-course analysis of the SgcG reaction after the increase in emission intensity with different enzyme concentration: filled squares, 1× SgcG; open squares, 2× SgcG; filled circles, 4× SgcG. (C) Single-substrate kinetic analysis with variable ADIC and saturating FMN. (D) Variable FMN and saturating ADIC.

Discussion

C-1027 in an enediyne antitumor antibiotic composed of a chromophore with four distinct chemical moieties (3). Upon cloning the biosynthetic gene cluster (8), it was revealed that these four moieties are likely derived from acyl-CoAs, chorismate, glucose-1-phosphate, and l-α-Tyr and that a convergent biosynthetic approach is used to piece together the final product. We have since established that (i) SgcA1, an α-d-glucopyranosyl-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase, catalyzes the first step in deoxy aminosugar biosynthesis (39); (ii) SgcC4, a methylideneimidazole-5-one dependent tyrosine aminomutase, generates the first intermediate in the biosynthesis of the β-amino acid (40, 41); and (iii) SgcE is a self-activating polyketide synthase that initiates the biosynthesis of the enediyne core. Presented here is the characterization of the first two enzymatic steps in the assembly of the remaining component, the benzoxazolinate moiety, establishing that chorismate is first converted by SgcD to ADIC, and ADIC is subsequently oxidized by SgcG to produce OPA (Figs. 2 and 3B).

Bioinformatics analysis revealed that SgcD is a member of the family of chorismate binding enzymes with closest sequence homology to ASI enzymes that catalyze the formation of anthranilate as the first committed step in Trp biosynthesis (SI Figs. 6 and 7) (28). Given that the two available Streptomyces genomes are each annotated with multiple putative ASI, we were concerned about genetic redundancy within S. globisporus and therefore opted to directly establish the catalytic function of SgcD by characterizing the enzyme in vitro. Preliminary experiments, using E. coli ASI as a control, revealed that SgcD was unexpectedly not an ASI. HPLC analysis clearly showed that SgcD converted chorismate to a product with identical spectral properties to ADIC, which has been identified as a bona fide intermediate of ASI by conversions of synthetic ADIC to anthranilate (17–19). This experiment was replicated in this study by confirming that SgcD-prepared ADIC is converted to anthranilate upon incubations with recombinant E. coli ASI, thereby providing definitive evidence to support the functional assignment of SgcD as an ADIC synthase.

Mutagenesis studies with S. typhimirium ASI and E. coli ADC synthase have hinted at the potential existence of a naturally occurring ADIC synthase. An S. typhimirium ASI (H398M) mutant was shown to transiently accumulate ADIC, although this mutant had <1% of the activity of the wild-type enzyme and produced only anthranilate during prolonged incubations (19). Interestingly, comparative modeling of SgcD with the S. typhimirium ASI structure suggest that SgcD is indeed an ASI, because all of the active site residues that have been described as essential for ASI catalysis are identical in SgcD (SI Fig. 6 and SI Table 1), including the His residue proposed to participate in pyruvate elimination. A different mutagenesis study, using E. coli ADC synthase, was also successful in generating an artificial ADIC synthase (27, 42). Based on structural analysis of ADC synthase (25, 27), it was predicted that the ε-amino group of an active site Lys is the nucleophile analogous to the free amine for ASI and SgcD that attacks C2 of chorismate, which, in the case of ADC synthase, then undergoes a second SN2″ addition at C4 with concomitant release of Lys to yield ADC. Indeed, when the K274A mutant was prepared, a pseudo rescue of activity was observed by addition of free amine at C2 to generate ADIC. Although this study had clear implications regarding the active site residues that dictate the regiospecificity of nucleophilic addition, and similar studies have expanded these findings to establish the controlling factors of nucleophile identity (24, 26), to date, the experimental results have fallen short of elucidating the residues responsible for pyruvate lyase activity of ASI. Having SgcD now available will undoubtedly facilitate such comparative analyses.

An ADIC synthase function has been proposed for PhzE, an ASI homologue required for phenazine biosynthesis (29, 30, 43). However, only indirect evidence has been provided for such a naturally occurring enzyme activity. This includes that (i) ADIC and not anthranilate is converted to phenazine metabolites from cell-free extracts of E. coli strains harboring the seven phenazine ORFs (30) and (ii) the activity of recombinant PhzD, catalysis by which is predicted to occur after PhzE, has been examined and the function assigned as an isochorismatase, i.e., hydrolysis of vinyl ethers (29). It was determined, however, that the PhzD enzyme had nearly identical second order rate constants with respect to ADIC and isochorismate. Further contradictory evidence to assign PhzE as an ADIC synthase has also been reported, including the ability of PhzE to complement an E. coli ASI mutant strain (44) and the interchangeability of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ASI homologues—one involved in the biosynthesis of Trp, the other in the phenazine pyocyanin (45), thus suggesting PhzE is an anthranilate synthase. Although our results have unambiguously established the activity of SgcD as an ADIC synthase, PhzE and SgcD have no significant sequence homology (<12% identity), and the aforementioned reports regarding phenazine biosynthesis are inconclusive, clearly preventing a functional assignment of PhzE with the currently available data.

The discovery of ADIC synthase activity of SgcD provided the impetus to search for an oxidoreductase that would furnish the aromatic ring of the benzoxazolinate moiety. Just downstream of sgcD is sgcG, the gene product of which is a predicted [Fe–S] flavin-dependent oxidoreductase. Although the closest homologues (the Isf protein family) do not have a defined catalytic function (33, 38, 46), SgcG was the most logical candidate to perform the desired oxidation/reduction chemistry, especially considering the sequence similarities to the WrbA family of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases that have the flavodoxin domain but lack the [Fe–S] cluster found in Isf and SgcG (SI Fig. 8) (34). As expected, SgcG quantitatively converted ADIC to OPA with FMN as the cosubstrate, thus establishing SgcG as an ADIC dehydrogenase. The development of the fluorescence-based assay described here allowed for initial kinetic studies with SgcG and has set the stage for detailed mechanistic studies on SgcG, including deciphering the role of [Fe–S] cluster in catalysis.

By elucidating the function of SgcD and SgcG, the biosynthetic pathway of the benzoxazolinate moiety leading to C-1027 is now known to proceed through OPA, a metabolite that to our knowledge has not been observed in biosynthetic pathways. Of significance, the functional assignment of these two enzymes has allowed us to modify the previously proposed pathway (8); subsequent steps require amide bond formation (SgcD5), hydroxylation (SgcD3), O-methylation (SgcD5), thio-esterification (SgcH), and acyl transfer (SgcD6) (Fig. 3B). Thus, the overall pathway proceeds with retention of the enolpyruvoyl moiety of chorismate as a vinyl ether. Because this is not observed for other metabolites descended from chorismate, the biosynthesis of C-1027 evidently involves a unique branching point in chorismate metabolism.

In conclusion, delineation of the biosynthetic pathway for C-1027 has hitherto uncovered a number of biochemical novelties. This report is in essence a continuation of this recurrent theme, because we have now identified the first naturally occurring ADIC synthase that—when coupled with SgcG—initiates a new branching point in chorismate metabolism. The discovery of SgcD clearly underscores the versatility of the ASI scaffold for evolving new cellular functions, and the results will undoubtedly help clarify the bifunctional catalysis of ASI and provide the inspiration to search for other variations of chorismate-using enzymes. In addition, the characterization of SgcD and SgcG will ultimately facilitate studies of downstream enzymes and the genetic engineering and combinatorial biosynthetic approaches aimed at harnessing the inherent power of the C-1027 scaffold.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Instrumentation.

Buffers, salts, and reagents were from standard commercial sources. Chorismate and FMN were from Sigma–Aldrich. HPLC was performed on a Waters system equipped with 515 pumps and a 996 diode array detector with the provided Millennium software. Fluorescence spectrometry was performed with a FluorMax-3 (Horiba Jobin Yvon). NMR data were obtained by using a Varian Unity Inova 400 or 500-MHz NMR Spectrometer (Varian). Routine LC-APCI-MS was carried out on an Agilent 1000 HPLC-MSD SL instrument (Agilent Technologies), using a C18 reverse-phase nanobore column and an 80% MeOH isocratic mobile phase. High resolution-electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy (HR-ESI-MS) was done at the Biotechnology Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with an Agilent 1100 HPLC-MSD TOF mass spectrometer.

Generation of E. coli Expression Constructs.

The genes for sgcD and sgcG were amplified by PCR with pBS1005 as a template (47). The gene for ASI was PCR-amplified from E. coli DH5α genomic DNA. PCRs were performed by using the Expand Long Template PCR System from Roche, using the provided protocol. Reactions were performed with the following primers: sgcD, 5′-GGTATTGAGGGTCGCATGACCGACCAGTGCGTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCTCACAGCAACTCCTCTCCG-3′ (reverse); sgcG, 5′-GGTATT G A G GGTCGCATGTTCTCCCCCGCCGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGA GGAGAGTTAGAGCCTCAGTACGCCTGGTGGGC-3′ (reverse); and ASI, 5′-GGTATTGAGGGTCGCATGCAAACACAAAAACCGACTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCTCAGAAAGTCTCCTGTGCATG-3′ (reverse). The gel-purified PCR products were inserted into pET-30 Xa/LIC by using ligation-independent cloning as described by Novagen, affording pBS1089 (for sgcD), pBS1090 (for sgcG), and pBS1091 (for ASI) and sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity.

Production and Purification of SgcD, SgcG, and E. coli ASI.

Culturing conditions for BL21(DE3) expression strains were similar to a procedure described in ref. 48. The proteins were purified by affinity chromatography with a Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen). SgcD and ASI were dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 2,000 vol of 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM DTT. SgcG was desalted by using a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). After concentration with a Vivaspin ultrafiltration device (10K MWCO; Sartorius), the purified proteins were stored at −25°C as 40% glycerol stocks. Proteins were purified to near homogeneity as assessed by 12% SDS/PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bradford dye-binding procedure (Bio-Rad) or by using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce) with provided BSA standards. The concentration of SgcG was determined with the active protein in solution or by eliminating potential interfering components with TCA precipitation and resolubilizing in 6 M guanidium HCl or by using a Compat-Able protein assay kit (Pierce) before the Bradford or BCA procedure. Cofactor analysis is described in SI Text.

Activity Assays for SgcD and ASI.

Standard reactions consisted of 100 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 333 mM NH4Cl, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM chorismate, and 0.7 mg/ml SgcD. For analytical analysis, the reaction was terminated by the addition of cold TCA (5% final concentration), and, after centrifugation, the clarified supernatant was loaded onto an Apollo C18 reverse phase column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 mm; Grace Davison) equilibrated with 0.1% TFA and 10% acetonitrile in H2O (solvent A). A series of linear gradients were developed from solvent A to solvent A containing 90% acetonitrile (solvent B) in the following manner: (beginning time and ending time with linear increase to percentage of solvent B): 0–5 min, 5% B; 5–7 min, 20% B; 7–27 min, 50% B; 27–28 min, 80% B; 28–38 min, 80% B; and 38–40, 5% B. The flow rate was kept constant at 1.0 ml/min, and elution was monitored at 280 nm.

Activity Assays for SgcG.

Standard reactions consisted of 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM FMN, 0.5 mM ADIC, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mg/ml SgcG. For analytical analysis, the reaction was terminated by ultrafiltration with a Microcon YM-5 (Millipore), and the sample was loaded onto an Apollo C18 reverse phase column equilibrated with 20 mM ammonium acetate, 10% acetonitrile, and 0.1% triethylamine pH 6.0 (solvent C). A series of linear gradients were developed from solvent C to solvent C containing 80% acetonitrile in an identical manner as described for SgcD activity assays. The flow rate was kept constant at 1.0 ml/min and elution was monitored at 316 nm.

The steady state kinetic parameters for SgcG were determined by monitoring the activity by using fluorescence spectroscopy (excitation at 316 nm/emission at 400 nm). The kinetic constants of ADIC were determined from reactions containing 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 200 μM FMN, 1.0–300 μM ADIC, and 85 nM SgcG; the kinetic constants of FMN were determined from reactions containing 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 500 μM ADIC, 0.5–100 μM FMN, and 75 nM SgcG. Each data point represents the average of minimally three duplicates. Michaelis–Menten constants were determined by using nonlinear regression analysis of initial velocity versus substrate concentration, using Kaleidagraph software, Version 3.0 (Adelbeck).

Preparation of ADIC and OPA.

ADIC and OPA were prepared enzymatically and purified by using semipreparative C18 reverse phase HPLC. The concentration of ADIC was determined by using UV/Vis spectroscopy with ε280 nm = 11,500 M−1·cm−1 (19). The concentration of OPA was determined by using UV/Vis spectroscopy with ε335 nm = 3970 ± 50 M−1·cm−1 in MeOH. Full details of ADIC and OPA preparation with mass and NMR data are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Dr. Y. Li (Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing) for the wild-type S. globisporus strain and the Analytical Instrumentation Center of the School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin, for support in obtaining MS and NMR data. This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA78747 and CA113297 and National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship CA1059845 (to S.V.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0708750105/DC1.

References

- 1.Wang X-W, Xie H. Drugs of the Future. 1999;24:847–852. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu JL, Xue YC, Xie MY, Zhang R, Otani T, Minami Y, Yamada Y, Marunaka T. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1988;41:1575–1579. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iida K-I, Fukuda S, Tanaka T, Hirama M, Imajo S, Ishiguro M, Yoshida K-I, Otani T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4997–5000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu YJ, Zhen YS, Goldberg IH. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5947–5954. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuno Y, Otsuka M, Sugiura Y. J Med Chem. 1994;37:2266–2273. doi: 10.1021/jm00041a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto T, Okuno Y, Sugiura Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:659–666. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu L, Mah S, Otani T, Dedon P. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8877–8878. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W, Christenson SD, Standage S, Shen B. Science. 2002;297:1170–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.1072110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamir H, Srinivasan PR. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6507–6513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye QZ, Liu J, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9391–9395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaille C, Reimmann C, Haas D. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16893–16898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Quinn N, Berchtold GA, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1417–1425. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison AJ, Yu M, Gardenborg T, Middleditch M, Ramsay RJ, Baker EN, Lott JS. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6081–6091. doi: 10.1128/JB.00338-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerbarh O, Ciulli A, Howard NI, Abell C. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5061–5066. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5061-5066.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols BP, Green JM. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5309–5316. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5309-5316.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmit JC, Zalkin H. Biochemistry. 1969;8:174–181. doi: 10.1021/bi00829a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teng CYP, Ganem B. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:2463–2464. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Policastro PP, Au KG, Walsh CT, Berchtold GA. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:2443–2444. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morollo AA, Bauerle R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9983–9987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morollo AA, Eck MJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2001;8:243–247. doi: 10.1038/84988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spraggon G, Kim C, Nguyen-Huu X, Yee MC, Yanofsky C, Mills SE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6021–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111150298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knochel T, Ivens A, Hester G, Gonzalez A, Bauerle R, Wilmanns M, Kirschner K, Jansonius JN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9479–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwahlen J, Kolappan S, Zhou R, Kisker C, Tonge PJ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:954–964. doi: 10.1021/bi060852x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolappan S, Zwahlen J, Zhou R, Truglio JJ, Tonge PJ, Kisker C. Biochemistry. 2007;46:946–953. doi: 10.1021/bi0608515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons JF, Jensen PY, Pachikara AS, Howard AJ, Eisenstein E, Ladner JE. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2198–2208. doi: 10.1021/bi015791b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerbarh O, Ciulli A, Chirgadze DY, Blundell TL, Abell C. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:622–624. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Z, Stigers Lavoie KD, Bartlett PA, Toney MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2378–2385. doi: 10.1021/ja0389927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh CT, Liu J, Rusnak F, Sakaitani M. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1105–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons JF, Calabrese K, Eisenstein E, Ladner JE. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5684–5693. doi: 10.1021/bi027385d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald M, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow LS, Floss HG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9459–9460. doi: 10.1021/ja011243+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles EW, Bauerle R, Ahmed SA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;142:398–414. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(87)42051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caligiuri MG, Bauerle R. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8328–8335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrade SLA, Cruz F, Drennan CL, Ramakrishnan V, Rees DC, Ferry JG, Einsle O. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3848–3854. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3848-3854.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patridge EV, Ferry JG. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3498–3506. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3498-3506.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fish WW. Methods Enzymol. 1988;158:357–364. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)58067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovenberg W, Buchanan BB, Rabinowitz JC. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:3899–3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang XF, Ezaki S, Atomi H, Imanaka T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:858–865. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Latimer MT, Painter MH, Ferry JG. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24023–24028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murrell JM, Liu W, Shen B. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:206–213. doi: 10.1021/np0340403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christenson SD, Wu W, Spies MA, Shen B, Toney MD. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12708–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi035223r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christenson SD, Liu W, Toney MD, Shen B. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6062–6063. doi: 10.1021/ja034609m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Z, Toney MD. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5019–5028. doi: 10.1021/bi052216p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mavrodi DV, Blankenfeldt W, Thomashow LS. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2006;44:417–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.013106.145710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierson LS, Gaffney T, Lam S, Gong F. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Essar DW, Eberly L, Hadero A, Crawford IP. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:884–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.884-900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao T, Cruz F, Ferry JG. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6225–6233. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6225-6233.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu W, Shen B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:382–392. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.382-392.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Lanen SG, Dorrestein PC, Christenson SD, Liu W, Ju J, Kelleher NL, Shen B. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11594–11595. doi: 10.1021/ja052871k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.