Abstract

A microfluidic mixer is applied to study the kinetics of calmodulin conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding. The device facilitates rapid, uniform mixing by decoupling hydrodynamic focusing from diffusive mixing and accesses time scales of tens of microseconds. The mixer is used in conjunction with multiphoton microscopy to examine the fast Ca2+-induced transitions of acrylodan-labeled calmodulin. We find that the kinetic rates of the conformational changes in two homologous globular domains differ by more than an order of magnitude. The characteristic time constants are ≈490 μs for the transitions in the C-terminal domain and ≈20 ms for those in the N-terminal domain of the protein. We discuss possible mechanisms for the two distinct events and the biological role of the stable intermediate, half-saturated calmodulin.

Keywords: hydrodynamic focusing, multiphoton microscopy, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

Calmodulin (CaM) is a small (148 aa, 17 kDa) Ca2+-binding protein that exists in all eukaryotic cells. CaM plays essential roles in Ca2+ signaling, regulating numerous intracellular processes such as cell motility, growth, proliferation, and apoptosis. The protein has two homologous globular domains connected by a flexible linker. Each domain contains a pair of Ca2+-binding motifs called EF-hands and binds two Ca2+ ions cooperatively. Ca2+ binding to each globular domain alters interhelical angles in the EF-hand motifs, causing a change from a “closed” to an “open” conformation. This results in the exposure of hydrophobic sites that bind to and activate a large number of target proteins.

The kinetics of Ca2+ dissociation from CaM has been studied with 43Ca NMR (1) and fluorescence stopped-flow experiments (2). These experiments reported a fast off-rate (>500 s−1) from the N-terminal lobe and a slower off-rate (≈10 s−1) from the C-terminal lobe. However, measurements of Ca2+ association and subsequent conformational changes of CaM have been more challenging because of technical limitations in investigating rapid kinetics. There are studies on conformational fluctuations of CaM using 15N-NMR relaxation (3) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) (4) in equilibrium, and an unfolding study using a temperature-jump method (5). However, the kinetics of Ca2+-induced CaM activation, which has a direct implication in Ca2+ signaling, has not been resolved.

In addition to biological importance, understanding the kinetics of CaM upon Ca2+ binding is highly relevant to the ongoing developments of genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors. It is of great interest to image quantitatively the Ca2+ dynamics in living cells. The recent advent of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators, such as cameleon (6), G-CaMP (7), and camgaroo (8), have enabled in vivo experiments that had been challenging with conventional organic dyes. Typically, these Ca2+ probes are constructed by fusing fluorescent proteins to CaM. The large conformational change of CaM upon Ca2+ binding is exploited to turn on the reporting fluorescence. One of the criteria in engineering these indicators is the response time to Ca2+ levels. A faster response is desirable for reporting rapid events such as neuronal Ca2+ dynamics (9).

Here, we describe the kinetics of Ca2+-induced structural changes of CaM using a microfluidic implementation of rapid mixing. We developed and characterized a microfluidic mixer capable of microsecond-scale kinetic experiments (10). The five-inlet port device effectively reduces premixing present in previous hydrodynamic focusing mixers (11) and facilitates rapid, uniform mixing. We demonstrate the first application of this technology to studying protein conformational changes on a microsecond time scale under conditions far from equilibrium.

Labeling CaM with a polarity-sensitive dye, acrylodan, we distinguish three states of CaM: apo-CaM, Ca2·CaM (CaM binding two Ca2+ ions), and Ca4·CaM (CaM binding four Ca2+ ions). The kinetics of Ca2+ binding and subsequent conformational changes are investigated by combining the microfluidic continuous-flow mixer with a stopped-flow mixer. The microfluidic mixer is used in conjunction with multiphoton microscopy for the time range from ≈40 μs to 2 ms. Stopped-flow experiments cover times ranging from 1 ms to 2 s. We have identified two distinct events during Ca2+-induced activation of calmodulin with drastically different time constants, ≈490 μs and ≈20 ms, respectively. It is likely that each process represents the conformational transitions of the C- and N-terminal domains of the protein. We address the presence of a stable intermediate state and also discuss the biological implications thereof.

Results

Microfluidic Mixer for Fast Kinetic Studies.

The reaction of CaM in this study involves binding of Ca2+ ions followed by conformational changes. Before investigating this two-step reaction, we studied binding of Ca2+ ions to Calcium Green-5N, which emits fluorescence almost instantaneously after binding. We have already characterized diffusive mixing in our microfluidic device by means of a simple diffusion-limited process, collisional quenching of fluorescence by iodide ions (10). Ca2+ binding to a Ca2+-sensitive dye serves as a control for measuring extremely fast chemical reactions using the device. Studying this simple bimolecular reaction is also worthwhile to resolve more complicated kinetics of CaM.

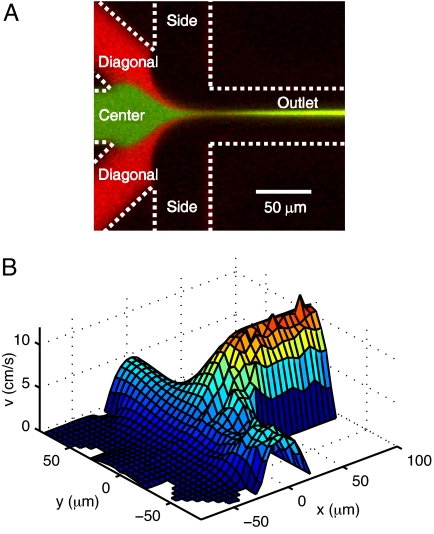

Fig. 1A presents a typical fluorescence image where Ca2+-sensitive dye from the center channel reacts with Ca2+ ions from two side channels in the device. The sheath flow from diagonal channels (shown in red) acts as a barrier to prevent mixing before the complete focusing of the sample and facilitates uniform abrupt mixing.

Fig. 1.

Microfluidic device for uniform mixing with microsecond time resolution. (A) Flow pattern in the mixer. The labels denote the six channels. Green pseudocolor is 10 μM Calcium Green-2 from the center channel, and red pseudocolor is 5 μM Rhodamine B from the diagonal channels while 10 mM CaCl2 is introduced from the side channels. (B) Flow-speed profile in the vertical center plane of the device. Experimental data measured with FCS (shown in y < 0) are in good agreement with simulation results (shown in y > 0). The flow rates are 13 nl/s in the center channel, 2.6 nl/s in the diagonal channels, and 130 nl/s in the side channels.

To retrieve the time constant of the reaction from a two-dimensional spatial image of the mixer, it is necessary to determine the precise flow-speed profile. We measured flow speeds in the mixer using confocal FCS. Fig. 1B shows the two-dimensional map of flow speeds in the mid-plane of the device, where imaging of the kinetic reaction takes place. The experimental measurements are plotted in one half of the symmetric device (y < 0), while the corresponding simulation predictions are presented in the other (y > 0). In the following analysis, the simulation results with the best fit to the experimental data are used to compute the flow speeds at individual pixels.

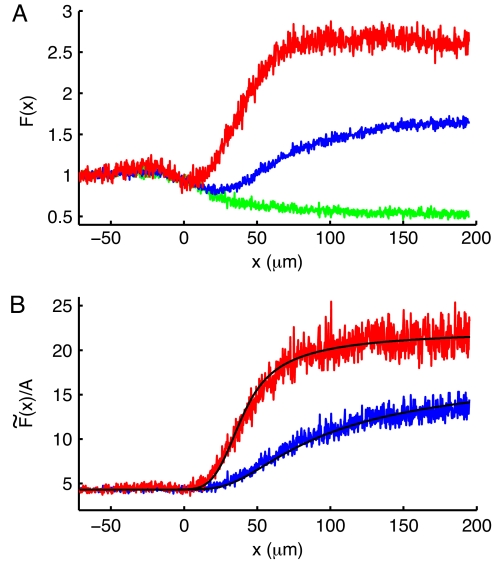

Equilibrium measurements show that the fluorescence intensity of Calcium Green-5N increases ≈24 times upon Ca2+ binding in 25 mM Mops/150 mM KCl at pH 7.0 and room temperature. The dissociation constant of the dye, KD, was determined to be 35 ± 1 μM from Ca2+ titration experiments. Fig. 2A depicts the fluorescence intensity of the jet, where 10 μM Calcium Green-5N dyes are mixed with Ca2+ ions. A control experiment was performed by injecting Calcium Green-5N in 1 mM CaCl2 into the center channel and 1 mM CaCl2 into the diagonal and side channels to evaluate the decreasing dye concentration in the jet by diffusion without further Ca2+ binding (Fig. 2A, green line). The effect of dye diffusion is taken into account by a calibration in our analysis (Fig. 2B). Two cases of mixing with different Ca2+ concentrations are illustrated, 100 μM CaCl2 (blue line) and 1 mM CaCl2 (red line), respectively. The increase in fluorescence intensity of Ca2+-sensitive dye can be described as a function of Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound dye concentrations, [Dye] and [Ca·Dye]:

where F(x) and Fc(x) are fluorescence intensities in the mixing and control experiments, respectively. A is a scaling factor determined by [Ca·Dye]0, which is the initial concentration of dye molecules already bound with Ca2+ before mixing in the device.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+ binding to Calcium Green-5N measured in the microfluidic mixer. (A) Fluorescence intensity of 10 μM Calcium Green-5N mixed with 100 μM CaCl2 (blue line) and 1 mM CaCl2 (red line) as a function of distance along the jet. Control data (green line) were acquired after the addition of 1 mM CaCl2 to every channel to measure diffusion of Ca2+-saturated dye molecules without further Ca2+ binding. Each dataset is normalized to the intensity of the fluorescent dye in the center channel before mixing to monitor net fluorescence changes after hydrodynamic focusing. (B) Fluorescence intensities of dye mixed with Ca2+ (blue and red lines) are divided by the control data (green line in A) (see Eq. 1). Theoretical calculations (black lines) with the best fit to both 100 μM and 1 mM CaCl2 mixing data yield kon = (2.6 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1·s−1.

The kinetic constant of Ca2+ binding to Calcium Green-5N, kon, was extracted by using an analysis similar to one demonstrated by Salmon et al. (12). Diffusion coefficients used in the numerical calculation [see supporting information (SI) Methods] are DDye = DCa·Dye = 1.15 × 10−6 cm2·s−1 (measured by FCS) and DCa2+ = 7.92 × 10 −6 cm2·s−1 (13). kon and [Ca·Dye]0 remain as variables to find the best fit to the experimental data (Fig. 2B, black lines). From the best fit to both 100 μM CaCl2 data (blue line) and 1 mM CaCl2 data (red line), we obtain kon = (2.6 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1·s−1 and [Ca·Dye]0 = 1.44 ± 0.01 μM. koff is calculated as the product of KD and kon to be 9,100 ± 1,100 s−1. A previous measurement by Naraghi (14), using a temperature-jump method to determine these rates for Calcium Green-5N, yielded kon = (4.0 ± 0.14) × 108 M−1·s−1 and koff = 9,259 ± 190 s−1 in 8 mM NaCl/20–40 mM Hepes/100–140 mM CsCl at pH 7.20 and 22°C. The similar results confirm the reliability of kinetic measurements with our microfluidic mixer.

Steady-State Characteristics of CaMAcr.

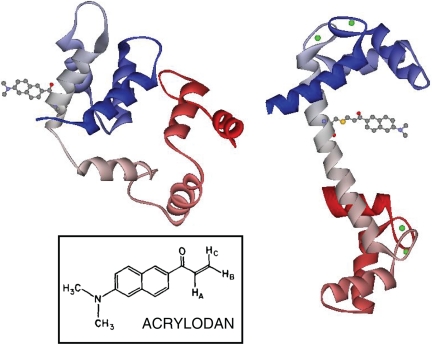

It previously has been established that CaM(C75)Acr (CaMAcr), which has a 6-acryloyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene (acrylodan) dye labeled on the Cys residue at amino acid position 75 of CaM (Fig. 3), reports conformational changes of CaM upon binding of Ca2+ ions and target peptides (15). It is necessary to verify that the mutation of Lys-75 into Cys and the subsequent labeling with acrylodan do not alter the biological function of CaM. For this purpose, the abilities of wild-type CaM (recombinant bacterial-expressed CaM) and CaMAcr to activate Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaM-kinase II) were compared as described in ref. 16. Our measurement confirmed that the acrylodan label does not significantly disturb the biological activity of the molecule (see SI Fig. 7).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of Ca2+-free (Left) and Ca2+-loaded (Right) CaMAcr. The crystal structures of Ca2+-free (PDB entry 1QX5) and Ca2+-loaded (PDB entry 1CLL) CaM were modified by using the program DS Viewer. (Inset) Structure of acrylodan.

The chemical structure of acrylodan is shown in Fig. 3 Inset. The conjugated electron distribution in the excited state extends beyond the naphthalene rings, and the dimethyl-amino and carbonyl group become electron donor and acceptor, respectively. Because of the large dipole moment produced as a result, the emission spectra of acrylodan demonstrate sensitivity to the polarity of the environment; substantial Stokes shifts are exhibited in the presence of polar solvent. This spectroscopic property of acrylodan can be exploited in identifying hydrophobic domains and dipolar relaxations (17). We observe such spectral shifts when we vary the Ca2+ concentration in the CaM solution (see SI Fig. 8). As Ca2+ is added, the emission peak is blue-shifted until the total Ca2+ concentration in the sample reaches ≈3 μM. The emission peak moves back toward red if more Ca2+ is added. Similar fluorescence characteristics have been observed for CaM labeled at Lys-75 with triazinylaniline (TA) dye (18).

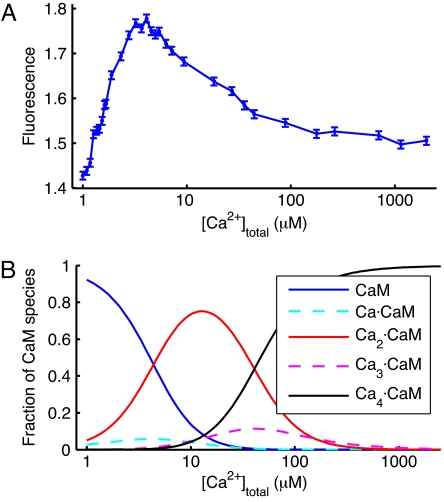

Ca2+ binding to CaM not only induces changes in the emission spectrum but also alters the quantum yield. Fig. 4A shows the fluorescence intensity of CaMAcr integrated from 400- to 600-nm emission wavelength as a function of Ca2+ concentration. To correlate the fluorescence signal with the fraction of CaM species binding zero to four Ca2+ ions, we measured the four macroscopic calcium binding constants of wild-type CaM (wtCaM) using a titration method developed by Linse et al. (19). The absorbance of 5,5′-Br2BAPTA [BAPTA, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid] at 263 nm decreases when the chelator binds Ca2+, and this was used to quantify the free Ca2+ concentration in solution. By titrating Ca2+ into a solution containing both wtCaM and 5,5′-Br2BAPTA, we derived the affinity of Ca2+ to wtCaM. Because the absorbance of CaMAcr at 263 nm slightly increases upon Ca2+ binding and interferes with the signal from 5,5′-Br2BAPTA, the same method could not be applied to the labeled CaM. The binding constants of wtCaM were obtained from least-squares fitting using the program CaLigator (20) (log K1 = 4.48 ± 0.03, log K2 = 6.28 ± 0.04, log K3 = 3.8 ± 0.2, and log K4 = 5.0 ± 0.1), which are in reasonable agreement with the published data (19). The fractions of CaM species were calculated from the measured binding constants and are plotted in Fig. 4B. The observed increase of fluorescence in Fig. 4A when Ca2+ is added up to 3 μM is likely due to accumulation of Ca2·CaM. The decrease in fluorescence with further addition of Ca2+ is due to the consecutive binding of two more Ca2+ ions. It appears that Ca2·CaM and Ca4·CaM species fluoresce >1.7 and ≈1.5 times, respectively, more than Ca2+-free CaMAcr. The fractions of Ca1·CaM and Ca3·CaM are negligible because of the positive cooperativity of Ca2+ binding in each globular domain. Because it is well known that the C-terminal domain of CaM has an ≈10-fold higher Ca2+ affinity than the N-terminal domain, the two Ca2+ ions present in the Ca2·CaM species are likely associated with the C-lobe (21).

Fig. 4.

Steady-state Ca2+ binding to CaM. From the comparison of A and B, the fluorescence increase of CaMAcr upon addition of Ca2+ is attributed to accumulation of Ca2·CaM, and the fluorescence decrease is associated with population of Ca4·CaM. (A) Fluorescence intensity of CaMAcr versus Ca2+ concentration. CaMAcr was diluted to 200 nM in decalcified CaM dilution buffer and titrated with CaCl2. The sample was excited at 375 nm at room temperature (≈20°C). The intensity was corrected for dilution of CaMAcr and normalized to the intensity of Ca2+-free CaMAcr, which was measured by adding 500 μM EGTA. (B) Fractions of CaM species binding different numbers of Ca2+ ion versus total Ca2+ concentration. The fractions were calculated from the macroscopic calcium binding constants of wtCaM.

Kinetics of Ca2+ Binding and Conformational Change of CaM.

We measured the fluorescence intensity change of CaMAcr molecules upon Ca2+ binding on two different time scales. A stopped-flow mixer was used to observe changes in the millisecond range, and the microfluidic mixer was used to resolve kinetics on microsecond time scales.

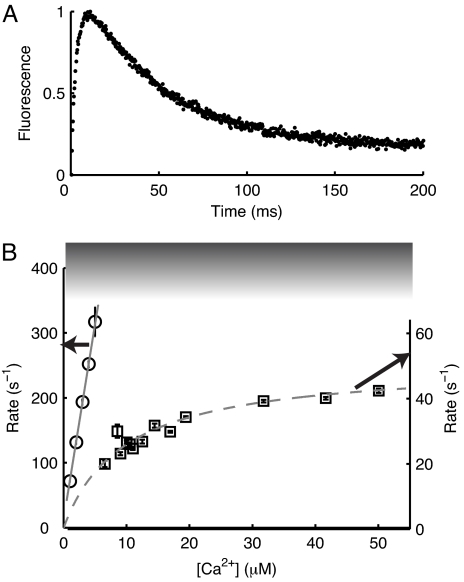

Stopped-flow experiments were performed with excitation at 375 nm, and fluorescence was detected by using a 400-nm long-pass filter. Fig. 5A depicts a representative fluorescence intensity change as a function of time when 400 nM CaMAcr was mixed with 10 μM CaCl2 in a stopped-flow mixer at 25°C. The signal increases abruptly, within ≈20 ms, due to the formation of Ca2·CaM. The fluorescence subsequently decreases because CaM saturates with Ca2+ at a much slower rate.

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of CaMAcr measured by stopped-flow fluorometry at 25°C. (A) Fluorescence change over time when 400 nM CaMAcr in decalcified buffer was mixed with 10 μM CaCl2. (B) Apparent rates of the first transition (circles) and the second transition (squares) as a function of the final Ca2+ concentration. The data represented by circles were measured by mixing CaMAcr in decalcified buffer with 2–10 μM CaCl2 and fit to a linear function (solid line). The rates for the second transition, represented by squares, were measured by mixing CaMAcr in 3 μM CaCl2 with 10–100 μM CaCl2 and fit with Eq. 2 (dashed line). The shaded area denotes the limit of the stopped-flow method.

The transitions into Ca2·CaM and Ca4·CaM were studied. Circles in Fig. 5B indicate the apparent rates of Ca2·CaM formation from apoCaM. Squares in Fig. 5B represent the accumulation rates of Ca4·CaM when the initial state was mostly populated by Ca2·CaM. Because the two reactions are not completely separated, a double exponential function is used in fitting each dataset to obtain the relevant rates. When 100 nM CaMAcr in decalcified buffer was mixed with 2–10 μM CaCl2, the rates (Fig. 5B, circles) increase in linear proportion to the Ca2+ concentration, indicating that Ca2+ binding to CaM is the rate-limiting process in the formation of Ca2·CaM at these low Ca2+ concentrations. A linear fit yields the kinetic constant of (6.03 ± 0.04) × 107 M−1·s−1, which we attribute to Ca2+ association with the C-lobe of CaMAcr. It is important to note that the fast transition into Ca2·CaM at Ca2+ concentrations above 5 μM was obscured within the dead time (≈1 ms) of the stopped-flow mixer.

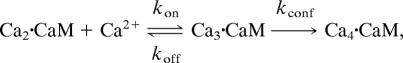

The complete saturation of CaM with two more Ca2+ ions was observed by mixing CaMAcr in 3 μM CaCl2 with 10–100 μM CaCl2. The second transition rates (Fig. 5B, squares) exhibit an asymptotic trend; the rate increases at higher Ca2+ concentrations but eventually reaches a maximum rate. The reaction can be approximated as a two-step process,

|

assuming that the fourth Ca2+ binding to CaM instantaneously follows the allosteric conformational change. The rate of the reaction, which is analogous to the Michaelis–Menten reaction, is derived from a steady-state approximation:

where Km = (kconf + koff)/kon, and [Ca2·CaM]0 is the initial concentration of the reactant. The best fit to the data with Eq. 2 yields kconf = 50 ± 2 s−1 and Km = 10 ± 1 μM. We associate the rate for the conformational change, kconf, with the transition of the N-terminal domain of CaMAcr after Ca2+ binding. Because kconf is much smaller than koff (>500 s−1) of the N-terminal domain (1, 2), Km is close to the Ca2+ dissociation constant of the domain. The value of Km is similar to the dissociation constant measured by Peersen et al. (22) using the flow-dialysis method.

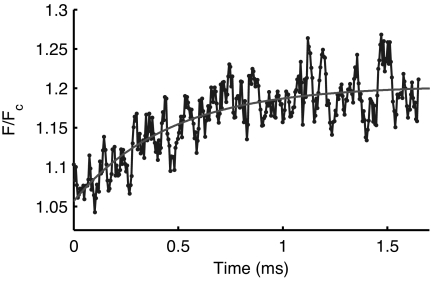

Notably, the conformational change in the C-terminal domain was too fast to be resolved by a stopped-flow mixer, because of the dead time of the technique, and required the microfluidic mixer to observe the kinetics on a microsecond time scale. The reaction was initiated by rapid mixing of 400 nM CaMAcr with 100 μM to 10 mM CaCl2. The time resolution of the kinetic measurements were estimated to be ≈40 μs by using the method described in ref. 10. Multiphoton microscopy was used to image the fluorescence change of the UV-excitable molecules in the mixer. The fluorescence signal in each mixing experiment was divided by the one from the control experiment where 1 mM CaCl2 was added in every channel.

Using the Ca2+ association rate to the C-lobe of CaMAcr measured in stopped-flow experiments, we were able to simulate the Ca2+ binding process in the mixer as demonstrated with Calcium Green-5N. A location was identified in the jet where >90% of CaM molecules were predicted to bind Ca2+ ions. From that location, the fluorescence change along the flow direction was converted into a function of time by using the flow-speed profile verified by FCS measurements as shown in Fig. 1B. A representative graph of the increasing fluorescence intensity versus time when CaMAcr is mixed with 3 mM CaCl2 is shown in Fig. 6. A single exponential fit to the data provides 2,190 ± 230 s−1 for the conformational changes in the C-lobe of CaMAcr. Mixing with 1–10 mM CaCl2 resulted in the same exponential trend, confirming that the observed rate is independent of the Ca2+ concentration (see SI Fig. 9). The average rate from four independent measurements was 2,030 ± 190 s−1.

Fig. 6.

Kinetics of conformational changes in C-lobe of CaMAcr measured by the microfluidic mixer. Four hundred nanomolar CaMAcr in decalcified buffer was mixed with 3 mM CaCl2 at room temperature (≈25°C). The fluorescence change of CaMAcr was imaged with multiphoton microscopy. A single exponential fit yields 2,190 ± 230 s−1 for the rate of the conformation changes.

Discussion

Rapid kinetic methods such as temperature-jump or photochemical triggering permit temporal resolution as short as nanoseconds (23). However, the application of conventional fluid mixing techniques has been limited to the millisecond regime. To access shorter time scales, various mixer designs have been implemented (24). We introduced a hydrodynamic focusing mixer with sheath flow to achieve microsecond time resolution (10). In this article, we establish the utility of the device by studying Ca2+-induced conformational switching of calmodulin. Our microfluidic technique allows rapid kinetic studies with sample consumption rates as low as ≈10 nl/s (≈100 pg/s of protein). New kinetic results are provided with regard to the formation of the intermediate Ca2·CaM and fully Ca2+-saturated CaM.

From the spectroscopic measurements with Ca2+ titration, we conclude that the formation of Ca2·CaM results in the increased fluorescence and spectral shift of acrylodan. Because the C-terminal lobe is known to bind Ca2+ ions with a higher affinity than the N-terminal lobe, we attribute the fluorescence change to the transitions of the C-lobe. The decreased fluorescence and spectral red-shift with further Ca2+ binding is due to the conformational change of the N-lobe.

We have found that the rates for the transformations of the C- and N-lobes differ by more than an order of magnitude, despite the highly homologous structure of the two globular domains. The conformational change of the C-domain occurs with a time constant, τ ∼ 490 μs, whereas additional binding of two Ca2+ ions to the N-domain of CaM induces structural transitions with τ ∼ 20 ms. We separated the kinetics of conformational change from Ca2+-binding kinetics by investigating two extreme cases. At low Ca2+ concentrations, binding of Ca2+ ions to CaM is the rate-limiting step; thus, the rate increases linearly with the Ca2+ concentration. In the limit of very fast binding of Ca2+ to the protein at high Ca2+ concentrations, the rate of the conformational change governs the overall reaction time.

It is interesting to compare the time constant of ≈490 μs in the C-lobe with the previous report by Tjandra et al. (3). Using 15N-NMR relaxation methods, they observed conformational exchanges on the similar time scale of 350 ± 100 μs in the C-lobe of apo-CaM. Malmendal et al. (25) assigned the dynamics to the fluctuations between the open and closed conformations of the C-domain in equilibrium. According to a model where an allosteric regulation occurs by a shift of the preexisting equilibrium (26), our results suggest that Ca2+ ions bind preferentially to apo-CaM in the open conformation, stabilize the structure, and shift the equilibrium. However, we cannot determine the sequence of Ca2+ binding and the conformational change solely from the kinetic data (27).

In contrast, the binding of two Ca2+ ions to the N-terminal lobe induces a change with τ ∼ 20 ms, which implies a different scenario. Using a CaM mutant in which the N-domain is locked in the closed conformation by a disulfide bond, Grabarek (28) found that two Ca2+ ions are coordinated in the closed N-lobe. Based on the comparison of the mutant with other CaM structures, he proposed a two-step mechanism in which diffusion-limited Ca2+ binding is followed by the hinge rotation of the Ile residue in the eighth position of the loop.

The different time scales for the conformational changes of the two globular domains could be explained by a negative cooperativity between the two lobes. Open conformation of the C-terminal lobe may stabilize the structure of Ca2·CaM and slow down the conformational changes in the N-terminal lobe. Indeed there are numerous studies reporting strong evidences of interdomain communication. For example, Sorensen and Shea (29) showed that the isolated N-terminal domain fragment has a higher affinity for Ca2+ than the domain in whole CaM. Ca2+-induced stabilization of the residues in the interdomain linker mediates the structural coupling between the distant domains of CaM (30, 31).

It has been implied in the literature that the stable intermediate Ca2·CaM has distinct roles in the activation of some target proteins. The x-ray structure of CaM bound to an adenylyl cyclase reveals that the C-domain of CaM is Ca2+-loaded, whereas the N-domain is Ca2+-free (32). Furthermore, the affinities of CaM-kinase II and myosin light chain kinase for the partially Ca2+-saturated CaM have been shown to be a potentially important factor in Ca2+ signaling pathways (33, 34). Our kinetic study illustrates the lifetime of the potentially important intermediate of Ca2·CaM.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and Labeling of Calmodulin.

A single Cys residue was introduced at amino acid position 75 by site-directed mutagenesis and labeled with acrylodan as described in ref. 15. Characterization of the fluorescently labeled protein was done to determine its ability to activate CaM-kinase II as described in ref. 16 (for details, see IS Methods).

Decalcification of Buffer and Labware.

For Ca2+ titration and kinetic experiments, CaM dilution buffer [25 mM Mops (pH 7.0), 150 mM KCl, 0.1 mg/ml BSA] was decalcified over a column of Calcium Sponge (Invitrogen) as described in ref. 35. All cuvettes, syringes, and other labware were rinsed with 0.1 M HCl and deionized water to remove Ca2+, and trace-metal-free pipette tips were used. CaMAcr or wtCaM stock solution was diluted in decalcified buffer before immediate use. Residual Ca2+ in buffer and CaM samples was determined by using Indo-1 (Invitrogen). The total calcium concentration was <200 nM in decalcified buffer and <800 nM in 400 nM CaMAcr solution.

Steady-State Ca2+ Binding.

Macroscopic Ca2+ binding constants of wtCaM were determined by using the competitive binding assay described by Linse et al. (19). CaCl2 was titrated into 15 μM wtCaM and 15 μM 5,5′-Br2BAPTA in decalcified CaM buffer. After each addition of CaCl2, the absorbance was measured at 263 nm by using a Cary/Varian 300 spectrophotometer. The binding constants were obtained by using the CaLigator software with a Levenberg–Marquardt nonlinear least-squares fitting routine (20).

Stopped-Flow Measurements.

Stopped-flow measurements were carried out on a KinTek SF-2004 instrument with a dead time of 1 ms. Excitation was at 375 nm, and emitted light was collected by using a 400-nm long-pass filter. Data from 5–10 injections were averaged and then fit with a double exponential function. All stopped-flow measurements were made at 25°C.

Imaging of Kinetics in the Microfluidic Mixer.

Microfluidic devices were fabricated and characterized as described in ref. 10 (see SI Methods for details). Fluorescence images were obtained by using multiphoton microscopy. An ≈100-fs pulsed Ti:Sapphire laser mode-locked at 780 nm was used to image the kinetic reactions in the microfluidic mixer. For Calcium Green-5N (Invitrogen), a ×20/0.7 N.A. water-immersion objective (Olympus) was used in conjunction with a 670UVDCLP dichroic beam splitter, a D525/50 band-pass filter (Chroma Technology), and bi-alkali photomultiplier tubes (Hamamatsu). For CaMAcr, a ×20/0.95 N.A. water-dipping objective (Olympus) was used with a 670LP dichroic beam splitter, a BGG22 emission filter (Chroma Technology), and GaAsP photomultiplier tubes (Hamamatsu). External syringe pumps (Harvard Apparatus) were used to inject 10 μM Calcium Green-5N or 400 nM CaMAcr into the center channel at 1 μl/min, blank buffer into the diagonal channels at 0.5 μl/min, and 1 mM CaCl2 into the side channels at 10 μl/min. For control data, a sample in 1 mM CaCl2 was introduced into the center channel, and 1 mM CaCl2 was infused into the diagonal and side channels. Fluorescence intensity along the focused jet in each image was background-subtracted, normalized to the intensity in the upstream of the center channel before mixing, and averaged for 50–100 images.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Mark A. Williams for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Cornell Nanobiotechnology Center, a Science and Technology Center Program of the National Science Foundation, under Agreement ECS-9876771; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/National Institutes of Health Grant 9 P41 EB001976; and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant P01-GM066275. All fabrication work was done at the Cornell NanoScale Science and Technology Facility, which is supported by the National Science Foundation, Cornell University, and industrial affiliates.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710810105/DC1.

References

- 1.Andersson T, Drakenberg T, Forsen S, Thulin E. Characterization of the Ca2+ binding sites of calmodulin from bovine testis using 43Ca and 113Cd NMR. Eur J Biochem. 1982;126:501–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayley PM, Ahlstrom P, Martin SR, Forsen S. The kinetics of calcium binding to calmodulin: Quin 2 and ANS stopped-flow fluorescence studies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tjandra N, Kuboniwa H, Ren H, Bax A. Rotational dynamics of calcium-free calmodulin studied by 15N-NMR relaxation measurements. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:1014–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slaughter BD, Allen MW, Unruh JR, Urbauer RJB, Johnson CK. Single-molecule resonance energy transfer and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of calmodulin in solution. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:10388–10397. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabl CR, Martin SR, Neumann E, Bayley PM. Temperature jump kinetic study of the stability of apo-calmodulin. Biophys Chem. 2002;101:553–564. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyawaki A, Griesbeck O, Heim R, Tsien RY. Dynamic and quantitative Ca2+ measurements using improved cameleons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2135–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca2+ probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Circular permutation and receptor insertion within green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11241–11246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Measuring calcium signaling using genetically targetable fluorescent indicators. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1057–1065. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park HY, et al. Achieving uniform mixing in a microfluidic device: Hydrodynamic focusing prior to mixing. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4465–4473. doi: 10.1021/ac060572n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight JB, Vishwanath A, Brody JP, Austin RH. Hydrodynamic focusing on a silicon chip: Mixing nanoliters in microseconds. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80:3863–3866. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon JB, et al. An approach to extract rate constants from reaction-diffusion dynamics in a microchannel. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3417–3424. doi: 10.1021/ac0500838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanýsek P. In: CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 85th Ed. Lide DR, editor. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 2006. pp. 5–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naraghi M. T-jump study of calcium binding kinetics of calcium chelators. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waxham MN, Tsai A, Putkey JA. A mechanism for calmodulin (CaM) trapping by CaM-kinase II defined by a family of CaM-binding peptides. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17579–17584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putkey JA, Waxham MN. A peptide model for calmodulin trapping by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29619–29623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prendergast FG, Meyer M, Carlson GL, Iida S, Potter JD. Synthesis, spectral properties, and use of 6-acryloyl-2-dimethylaminonaphthalene (acrylodan). J Biol Chem. 1983;258:7541–7544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowley DJ, McCormick JP. Triazinylaniline derivatives as fluorescence probes. Part 3. Effects of calcium and other metal ions on the steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence of bovine brain calmodulin labelled at lysine-75. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 1996:1677–1684. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linse S, Helmersson A, Forsen S. Calcium binding to calmodulin and its globular domains. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8050–8054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andre I, Linse S. Measurement of Ca2+-binding constants of proteins and presentation of the CaLigator software. Anal Biochem. 2002;305:195–205. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teleman A, Drakenberg T, Forsen S. Kinetics of Ca2+ binding to calmodulin and its tryptic fragments studied by 43Ca-NMR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;873:204–213. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peersen OB, Madsen TS, Falke JJ. Intermolecular tuning of calmodulin by target peptides and proteins: Differential effects on Ca2+ binding and implications for kinase activation. Protein Sci. 1997;6:794–807. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton WA, et al. Fast kinetics and mechanisms in protein folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:327–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roder H, Maki K, Cheng H. Early events in protein folding explored by rapid mixing methods. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1836–1861. doi: 10.1021/cr040430y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malmendal A, Evenas J, Forsen S, Akke M. Structural dynamics in the C-terminal domain of calmodulin at low calcium levels. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:883–899. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kern D, Zuiderweg ERP. The role of dynamics in allosteric regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson KA. Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. The Enzymes. 1992;20:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grabarek Z. Structure of a trapped intermediate of calmodulin: Calcium regulation of EF-hand proteins from a new perspective. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1351–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen BR, Shea MA. Interactions between domains of apo calmodulin alter calcium binding and stability. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4244–4253. doi: 10.1021/bi9718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin ZH, Squier TC. Calcium-dependent stabilization of the central sequence between Met76 and Ser81 in vertebrate calmodulin. Biophys J. 2001;81:2908–2918. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75931-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaren OR, Kranz JK, Sorensen BR, Wand AJ, Shea MA. Calcium-induced conformational switching of Paramecium calmodulin provides evidence for domain coupling. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14158–14166. doi: 10.1021/bi026340+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drum CL, et al. Structural basis for the activation of anthrax adenylyl cyclase exotoxin by calmodulin. Nature. 2002;415:396–402. doi: 10.1038/415396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shifman JM, Choi MH, Mihalas S, Mayo SL, Kennedy MB. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is activated by calmodulin with two bound calciums. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13968–13973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606433103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown SE, Martin SR, Bayley PM. Kinetic control of the dissociation pathway of calmodulin-peptide complexes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3389–3397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaertner TR, Putkey JA, Waxham MN. RC3/neurogranin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II produce opposing effects on the affinity of calmodulin for calcium. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39374–39382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.