Abstract

Viral methyltransferases are involved in the mRNA capping process, resulting in the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine to capped RNA. Two groups of methyltransferases (MTases) are known: (guanine-N7)-methyltransferases (N7MTases), adding a methyl group onto the N7 atom of guanine, and (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferases (2′OMTases), adding a methyl group to a ribose hydroxyl. We have expressed and purified two constructs of Meaban virus (MV; genus Flavivirus) NS5 protein MTase domain (residues 1–265 and 1–293, respectively). We report here the three-dimensional structure of the shorter MTase construct in complex with the cofactor S-adenosyl-L-methionine, at 2.9 Å resolution. Inspection of the refined crystal structure, which highlights structural conservation of specific active site residues, together with sequence analysis and structural comparison with Dengue virus 2′OMTase, suggests that the crystallized enzyme belongs to the 2′OMTase subgroup. Enzymatic assays show that the short MV MTase construct is inactive, but the longer construct expressed can transfer a methyl group to the ribose 2′O atom of a short GpppAC5 substrate. West Nile virus MTase domain has been recently shown to display both N7 and 2′O MTase activity on a capped RNA substrate comprising the 5′-terminal 190 nt of the West Nile virus genome. The lack of N7 MTase activity here reported for MV MTase may be related either to the small size of the capped RNA substrate, to its sequence, or to different structural properties of the C-terminal regions of West Nile virus and MV MTase-domains.

Keywords: flavivirus, (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase, viral enzyme, RNA capping, S-adenosyl-L-methionine

mRNA capping is a cotranscriptional modification that adds a unique molecular structure at the 5′ end of viral and eukaryotic mRNAs. The added “cap” plays an essential role in the mRNA life cycle, being required for efficient pre-mRNA splicing, export, stability, and translation. Moreover, the cap can protect mRNA from enzymatic degradation (Parker and Song 2004). The capping process is generally started by the conversion of the 5′-triphosphate end of mRNA to a 5′-diphosphate by an RNA triphosphatase. A GMP unit is then added in a 5′–5′ phosphodiester bond by a guanylyltransferase. The cap is further decorated by the addition of methyl groups to the N7 position of the guanine (cap0; e.g., 7MeGppp-N), and to a ribose 2′-OH group of the first nucleotide of the mRNA (cap1; e.g., 7MeGppp-N2′OMe). These steps are catalyzed by (guanine-N7)-methyltransferase (N7MTase) and by (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase (2′OMTase), respectively, both transferring a methyl group from the cofactor S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) to the substrate RNA. In some cases, methylation of the guanine base may occur before guanylyltransfer (Ahola and Kaariainen 1995).

Many viruses replicate in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, whose mRNA capping machinery is located in the nucleus. Accordingly, some of these viruses have developed a strategy that does not require RNA capping, while others, such as flaviviruses, encode at least part of their own RNA capping enzymes that display structures and catalytic mechanisms different from those of eukaryotes. The viral RNA capping machinery is therefore held to be an important target for rational drug design, so far scarcely characterized or exploited.

Crystal structures have been reported for four different MTases involved in viral mRNA capping. These concern the VP39 2′OMTase from the double-stranded DNA vaccinia virus (Hodel et al. 1996) and the N7MTase and the 2′OMTase domains of the λ2 core protein from the double-stranded RNA Reovirus (Reinsch et al. 2000). Additionally, the structure of the MTase domain of Dengue virus NS5 protein (DVMTase) in complex with S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine (AdoHcy), the product of the methylation reaction, has been reported (Egloff et al. 2002). The crystal structures have shown that the core domain of RNA cap MTases is structurally related to that of other AdoMet-dependent MTases acting on different substrates (Faumann et al. 1999; Bugl et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2000). Such a core domain, hosting the catalytic center and a specific AdoMet recognition motif (Ingrosso et al. 1989), is based on a seven-stranded β-sheet surrounded by six α-helices. The protein regions flanking the core domain account for the different substrate specificities displayed by AdoMet-dependent MTases.

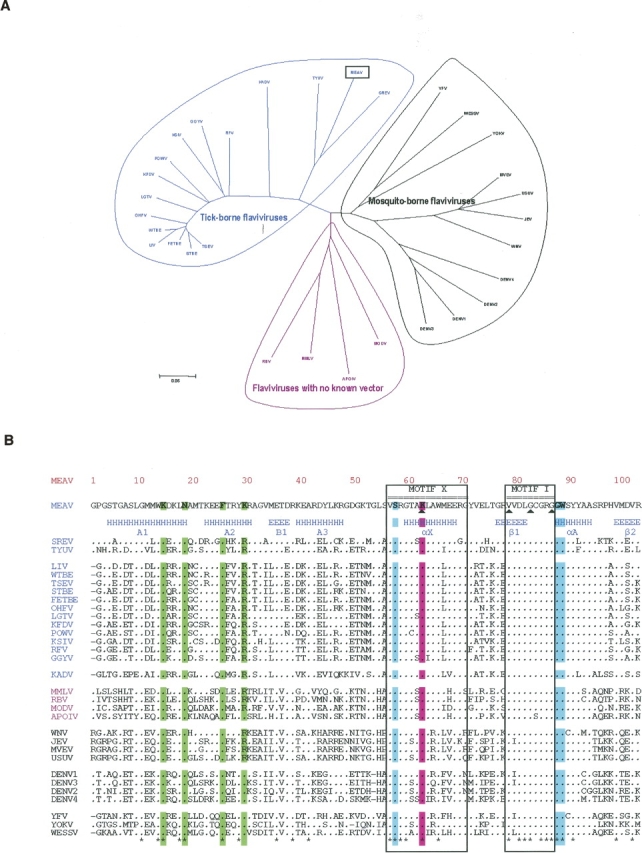

The genus Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae comprises over 70 viruses, many of which are important human pathogens. The flavivirus genome encodes a 370-kDa polyprotein precursor connected to the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. The polyprotein is processed by cellular and viral proteases to yield three mature structural proteins (C, M, and E), and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (Fields et al. 2001). Phylogenetic studies revealed that a common ancestor originated the presently known viruses, which schematically belong to three major evolutionary branches: tick-borne flaviviruses (TBFVs), mosquito-borne flaviviruses (MBFVs), and viruses with no known vector (NKVs, which are believed to be nonvectorized viruses infecting bats and rodents) (Fig. 1A).

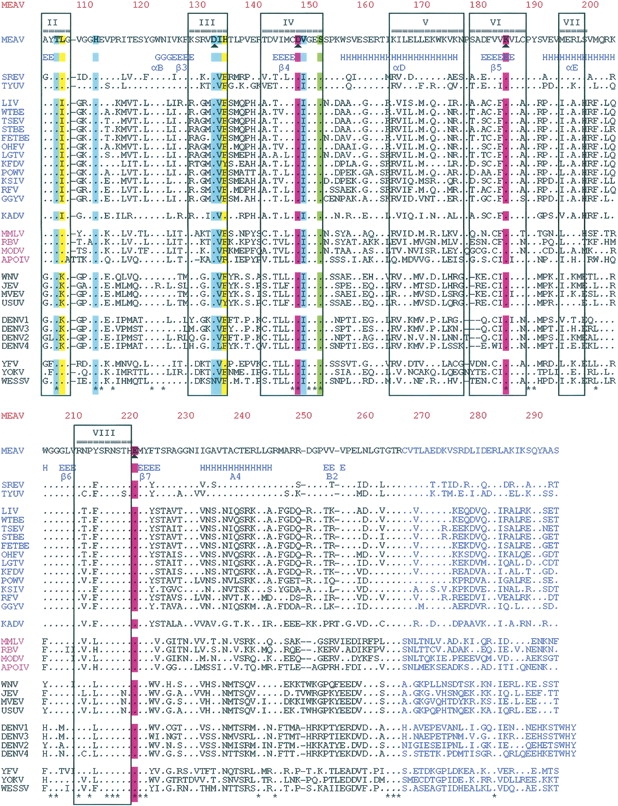

Figure 1.

(A) Phylogenetic tree built based on the MTase amino acid sequence alignments, using the p-distance and the Neighbor-Joining method implemented in the MEGA 3 program. All abbreviations are those of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. (B) Amino acid sequence alignments of MTase from Meaban virus (MEAV) with (1) other tick-borne flavivirus species: seabird tick-borne virus group, Tyuleniy virus (TYUV), Saumarez Reef virus (RSEV); mammalian tick-borne virus group, Loupig ill virus (LIV), Western, Siberian, and Far Eastern subtypes of the tick-borne encephalitis virus (WTBE, STBE, FETBE), Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (OHFV), Langat virus (LGTV), Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV), Powassan virus (POWV), Karshi virus (KSIV), Gadgets Gully virus (GGYV), Royal Farm virus (RFV), Kadam virus group, Kadam virus (KADV); (2) representatives of mosquito-borne flaviviruses: transmitted by culex mosquitoes, West Nile virus (WNV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Murray valley encephalitis virus (MVEV), Usutu virus (USUV); transmitted by culex mosquitoes, Yellow fever virus, Wesselsbron virus (WESSV). Yokose virus (YOKV) is a virus with no known vector genetically related to the Yellow fever virus group; (3) representatives of flaviviruses with no known arthropod vector: Montana myotis leukoencephalitis virus (MMLV), Rio Bravo virus (RBV), Modoc virus (MODV), Apoi virus (APOIV). In pink color: KDKE residues. In green (highly conserved) amino acids involved in the interaction with a GTP analog (Ribavirin triphosphate). In blue (well conserved) and yellow (poorly conserved) amino acids involved in the interaction with AdoMet. The position of conserved DNA MTase motifs I to X, except for motif IX, conserved only for (cytosine-5)DNA MTases (Posfai et al. 1989), are indicated (▴). The secondary structure elements stretches refer to MVMTaseSC. The 28 amino acids of MV MTase in blue characters are those building the C-terminal stretch of MVMTaseLC. Alignments were built with the help of the ClustalX program. (*) Strictly conserved positions. Secondary structure elements were assigned using the program dssp (Kabsch and Sander 1983). For better readability, strictly conserved residues have been indicated by dots.

The TBFV lineage is of special interest. A recent analysis of complete genomes of all TBFV species (Grard et al., in press) revealed three evolutionary groups, i.e., (1) the mammalian tick-borne virus group that encompasses major human pathogens such as the Tick-borne encephalitis virus, the BSL-4 Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus, and Kyasanur Forest disease virus; (2) the Kadam virus group; and (3) the seabird tick-borne virus group. The latter intriguing group includes the Meaban virus, which was isolated in 1985 in France from the soft tick Ornithodoros (Alectorobius) maritimus (Chastel et al. 1985) and never identified in other parts of the world. Other member viruses of this group are the Tyuleniy (Russia, Norway, Oregon) and Saumarez reef (Australia) viruses. Based on serological data, it has been suggested that these viruses may be mild human pathogens (St. George et al. 1977; Chastel 1980). In contrast with mammalian TBFVs, there is no evidence among seabird TBFVs for a close relationship between genetic evolution and geographic distribution. One can reasonably assume that they have been disseminated by independent migratory flights and that their observed genetic evolution reflects adaptation to the different ecological niches they have reached.

We present here a structural and functional study of the Meaban virus MTase domain (MVMTase), i.e., the N-terminal domain of the flaviviral NS5 protein (about 900 total residues) that, besides the MTase domain, displays a C-terminal region endowed with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) activity. Consistent with previous flavivirus sequence analysis (Koonin 1993), we identified the presence of the characteristic motif of AdoMet-dependent MTases within the N-terminal domain of Meaban virus NS5. Alignment of MVMTase with other flavivirus MTases (Fig. 1B) shows amino acid sequence identities of 27%–30% relative to other seabird TBFVs (mean value: 28%), 40%–44% relative to mammalian TBFVs (mean value: 42%), and 48%–55% with respect to other flaviviruses (mean value: 52%). Accordingly, it is expected that MVMTase may be the best available model for mammalian TBFVs to date, and may share important structural and functional characteristics with mosquito-borne flaviviruses.

Two constructs of MVMTase of different length (MVMTase short construct [MVMTaseSC], amino acids 1–265, and MVMTase long construct [MVMTaseLC], amino acids 1–293, respectively, both of the NS5 gene) have been expressed and purified in our laboratories. Extensive crystallization trials on both constructs yielded usable crystals of MVMTaseSC, allowing us to present here its 2.9 Å resolution crystal structure, in complex with AdoMet, as the first three-dimensional structure of a MTase from the TBFV lineage. Our results show that the MVMTaseSC core domain structure conforms to that of the catalytic domain of other AdoMet-dependent MTases (Faumann et al. 1999). Moreover, the high structural homology of MVMTase and DVMTase and the structural location of selected active site residues suggest that MVMTase may act as a 2′OMTase. We show that such a structure-based hypothesis is supported by measurement of MVMTase 2′OMTase activity using capped RNA short substrates. The experimental results presented here are discussed in the light of recent results on West Nile virus MTase (WNVMTase) that displays both guanine N7 and ribose 2′-O methylation (Ray et al. 2006).

Results

Structure analysis

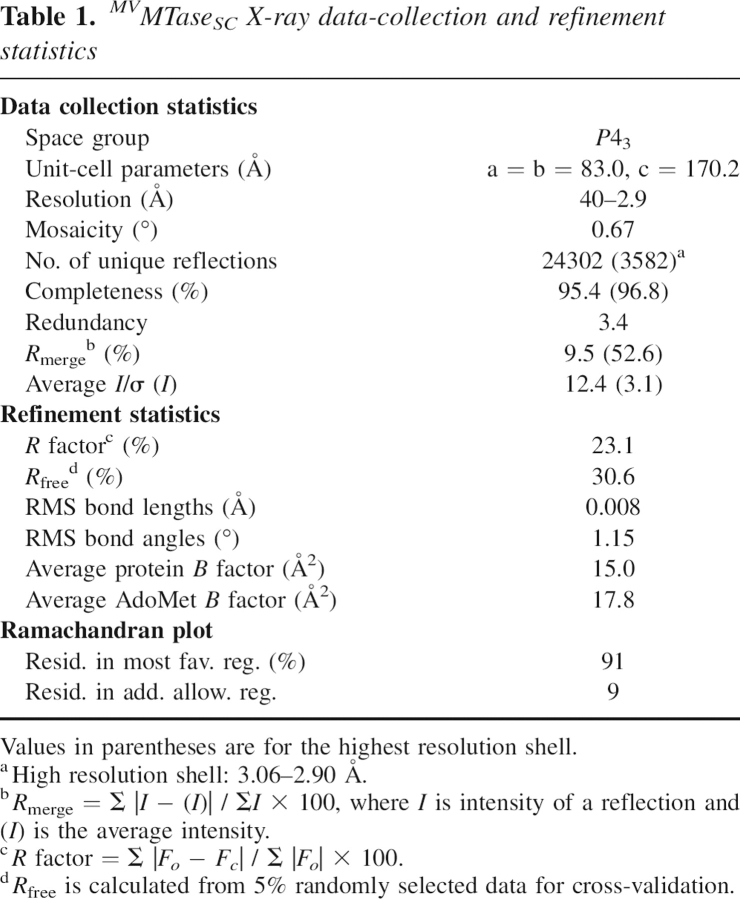

MVMTaseSC crystallized in the tetragonal space group P43, with four molecules per asymmetric unit. The protein structure was solved in complex with AdoMet using molecular replacement techniques and refined to 2.9 Å resolution. The final crystallographic R factor is 23.1%, and the R free is 30.6%, for the 40–2.9 Å resolution data (Table 1). Structural superposition of the four independent protein Cα backbones yields RMSD values in the 0.28–0.48 Å range. The four MVMTaseSC chains are assembled in two dimers displaying identical quaternary assembly; the subunit association interface in each dimer is about 770 Å2. In consideration of the gel-filtration behavior of the protein, which elutes as a monomer, the loose quaternary assemblies observed in the crystal are taken simply as indicative of a tendency to aggregate at the high concentrations achieved during crystal growth.

Table 1.

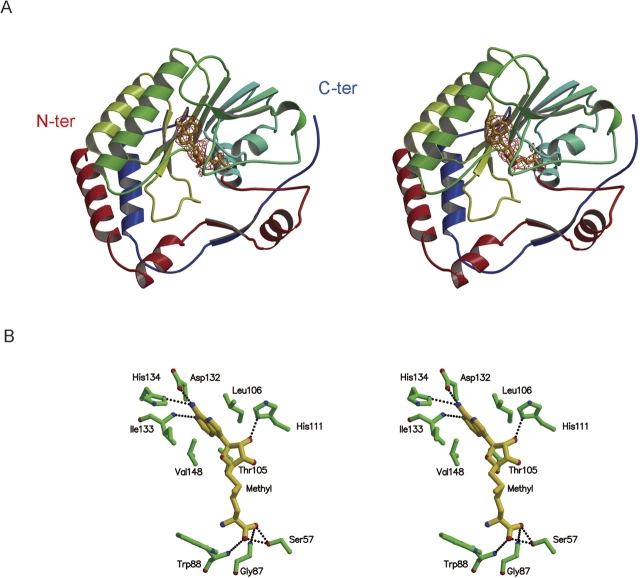

MVMTaseSC is composed of a core domain (residues 59–224) flanked by an N-terminal region (residues 1–58), and a C-terminal region (residues 225–265) (Fig. 2A). The core domain topology, consisting of a seven-stranded β-sheet surrounded by four α-helices and a 310 helix, closely resembles the topology observed in the catalytic domain of all other AdoMet-dependent MTases (Faumann et al. 1999; Egloff et al. 2002), where the seven-stranded mixed and twisted β-sheet is strictly conserved, while the number of flanking helices may vary between four and six (Hodel et al. 1996, Faumann et al. 1999, Egloff et al. 2002). The N-terminal segment comprises a helix–turn–helix motif followed by a β-strand and an α-helix. The C-terminal region consists of an α-helix and a β-strand (Fig. 2A). Relative to the AdoMet-dependent MTase consensus fold (7 strands/6 helices) the MVMTaseSC structure lacks an α-helix between β-strands 3 and 4 (Fig. 1B) and displays a short 310 helix (amino acids 122–124) in place of an α-helix between β-strands 2 and 3, immediately followed by the β-strand 3 (Figs. 1B, 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Stereo view of MVMTaseSC in complex with AdoMet. The central portion (59–224) of the polypeptide chain folds into a core subdomain in which a mixed seven-stranded β-sheet is surrounded by four α-helices and one 310 helix (green and cyan secondary structure elements). The central region hosts AdoMet (drawn as a yellow stick model). The red Fo − Fc map surrounding AdoMet was calculated after several refinement cycles carried over in the absence of the ligand. Tagged to the core are an N-terminal region (1–58), comprising a helix–turn–helix motif followed by a β-strand and an α-helix (in red), and a C-terminal region (225–265), consisting of an α-helix and a β-strand (in blue). (B) AdoMet recognition by MVMTaseSC. Stereo view of AdoMet bound to its specific site in the core domain of MVMTaseSC, showing the main residues involved in stabilizing interactions. The AdoMet molecule is yellow, while the protein residues are green; nitrogen atoms are shown in blue, oxygen in red. The main hydrogen bonds between MVMTaseSC and AdoMet are indicated by black dotted lines. The figures were generated using MolScript (Kraulis 1991).

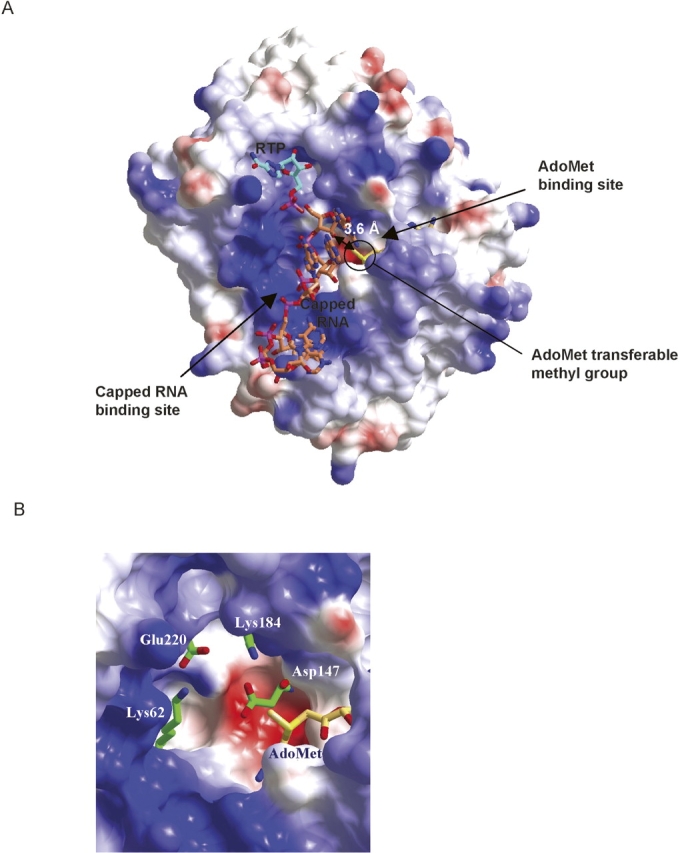

The MVMTaseSC core domain displays two obvious surface clefts. The deeper cleft is occupied by the AdoMet cofactor (see below), the other, by reference to the homologous DVMTase structure, is expected to act as the binding site for capped RNA (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Molecular surface color coded for the electrostatic potential (Red −39 kTe−1, Blue +39 kTe−1). MVMTaseSC crystal structure allows locating two clefts in the core domain region. The inner cleft is occupied by AdoMet (shown as a yellow stick model). The donor methyl group protrudes from the AdoMet pocket toward the center of the surface (second) cleft, where the positively charged region is shown in blue. The second cleft is the expected capped RNA binding site. We modeled the position of the capped RNA by superposition of MVMTaseSC with 7MeGpppGA5 (in coral) from VP39 (PDB entry 1AV6); the cap region not properly fitting the model has been omitted from the drawing. Ribavirin triphosphate (RTP, in light blue) was modeled through superposition with DVMTase (PDB entry 1R6A). The small double-headed arrow relates the locations of AdoMet exchangeable methyl group and of the methylable RNA adenine-ribose 2′OH group. Oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphor atoms are in red, blue, and pink, respectively. (B) Residue disposition in the K–D–K–E motif next to the AdoMet exchangeable methyl group, proposed as a structural fingerprint characteristic of RNA-specific 2′OMTase. The figures were generated using CCP4mg (Potterton et al. 2002).

The AdoMet binding site

During the refinement procedure, the Fo − Fc map revealed strong residual density in a protein region comprised between β-strands 1 and 4. Since AdoMet, the cofactor of the methyltransfer reaction, was added to the crystallization medium, and in view of the structural homology with DVMTase that binds AdoHcy in its crystal structure, an AdoMet molecule was modeled in such residual density and thoroughly refined (Fig. 2A,B). The AdoMet molecule is stabilized in the MVMTaseSC binding pocket by a network of hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts, generally matching those predicted as consensus interactions in AdoMet-dependent MTases (Faumann et al. 1999), and involving enzyme residues well conserved within the MTases flavivirus group (see Figs. 1B, 3A). The AdoMet ribose moiety is stabilized by a hydrogen bond linking His111Nδ1 to the 2′-OH; the adenine ring is accommodated within a hydrophobic pocket defined by the side chains of Thr105, Leu106, Ile133, and Val148, and stabilized by hydrogen bonds to the side chains of Asp132 and His134 and the main chain N atom of Ile133. The rest of the AdoMet molecule is stabilized by hydrogen bonds provided by the side chain Oγ atom of Ser57 and by the main chain N atoms of Gly87 and Trp88 (Fig. 2B). The overall AdoMet binding mode to the enzyme is essentially identical in the four MVMTaseSC chains present in the crystallographic asymmetric unit, with the exception of the (Met) amino and carboxy ends of the cosubstrate that tend to be disordered in all four molecules, as indicated by their high B-factor values relative to the rest of the AdoMet molecule. The binding mode of AdoMet to MVMTaseSC matches essentially that of AdoHcy in the homologous DVMTase crystal structure, both on the cofactor and on the protein sides, where structural adaptations related to the loss/presence of the exchangeable methyl group are not evident.

The large family of AdoMet-dependent MTases shows a high degree of structural homology that is, however, scarcely reflected in their amino acid sequences. Nevertheless, for DNA MTases, nine conserved sequence motifs involved in AdoMet binding and catalysis have been identified (Malone et al. 1995). In this respect, MVMTase sequence shows conservation of motif I (Val–Gly–Gly), the universal AdoMet-binding pocket (Koonin 1993), and of motif III (Asp132), which is involved in AdoMet hydrogen bonding (Malone et al. 1995) (Fig. 1B).

The active site

The MTase active site is primarily identified by the location of the AdoMet exchangeable methyl group. In MVMTaseSC such region falls close to a patch of charged residues comprising Lys62, Asp147, Lys184, and Glu220 (the K–D–K–E motif), which are conserved within Flavivirus RNA MTases. The residues fall within sequence motifs X, IV, VI, and VIII defined for DNA MTases (Malone et al. 1995) and, with the exception of motif X, are primarily involved in catalysis (Fig. 1B). In MVMTaseSC the donor methyl group protrudes from the AdoMet pocket toward the putative RNA binding cleft that shows an extended positive charge distribution (Fig. 3A). Notably, the spatial disposition of the K–D–K–E motif, next to the AdoMet methyl group (Fig. 3B), was proposed as characteristic of RNA-specific 2′OMTase (Bujnicki et al. 2001). Such structure-based observation is in line with the high sequence homology linking MVMTase to DVMTase that acts as a 2′OMTase (Egloff et al. 2002; Fig. 1B). Not excluding the possibility that MVMTase might perform N7-guanine methylation, the conservation of the four specific K–D–K–E residues in the active site strongly suggests the 2′OMTase role for MVMTase.

In order to assess the critical location of AdoMet methyl group relative to the acceptor ribose 2′-hydroxyl, we superposed the MVMTaseSC structure on the three-dimensional structure of VP39, a vaccinia virus 2′OMTase crystallized in complex with 7MeGpppGA5 and AdoHcy (Hodel et al. 1998; PDB 1AV6). The RMSD of such structural superposition (based on 155 Cα pairs) varies between 2.8 and 2.9 Å for the four different MVMTaseSC chains. Thus, based on such a structural comparison, we were able to position 7MeGpppGA5 in the putative capped-RNA binding site of MVMTaseSC. Such a modeling exercise snugly fits the first RNA guanine in the protein active site (not requiring any structure readjustment or minimization); the ribose 2′-OH is positioned next to the AdoMet methyl group (Fig. 3A), with the conserved K–D–K–E motif lining the cleft next to the guanine ribose. Such a mutual disposition of AdoMet and the capped RNA further suggests that the K–D–K–E motif may support the ribose 2′-OH deprotonation required for nucleophilic attack on the carbon atom of the AdoMet methyl group (Fig. 3B).

Cap binding site

From the above described structural superposition of VP39/7MeGpppGA5 and MVMTaseSC it was, however, not possible to extrapolate a reliable orientation for the 7MeGppp (cap) part of the substrate, since this fragment, as modeled, displays unfavorable contacts with several amino acids of the MVMTaseSC cap binding pocket. In order to model protein/cap interactions more reliably, we then superposed MVMTaseSC on the crystal structure of DVMTase in its complex with AdoHcy and ribavirin triphosphate, (RTP), a GTP analog mimicking the cap (Benarroch et al. 2004; PDB 1R6A); the generated superposition was based on 48% amino acid sequence identities relating the two enzymes. The RMSD of such a superposition (calculated on 250 Cα pairs) varies between 0.8 and 0.9 Å for the four different MVMTaseSC chains. In the resulting model of the putative MVMTaseSC/RNA cap interaction (Fig. 3A), the RTP triazole ring stacks on the aromatic ring of Phe25, which had previously been shown to play an essential role in guanine binding (Egloff et al. 2002), Lys29 and Ser151 being the residues closest to the RTP α-phosphate. The model also suggests that the MVMTaseSC GTP specificity (vs. dGTP specificity) may rely on the achievement of specific hydrogen bonds involving the ribose 2′-OH group and residues Lys14 and Asn18 (conserved among flavivirus MTases; Fig. 1B).

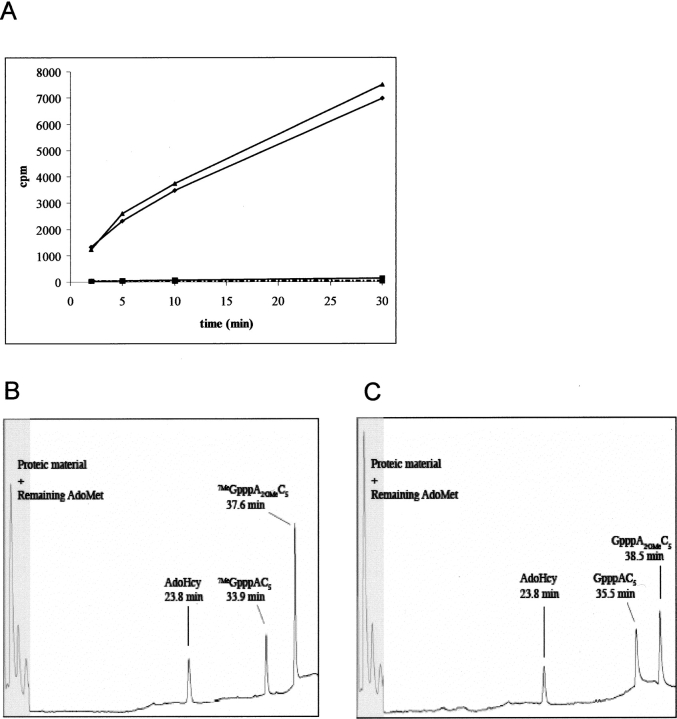

The activity of MVMTaseSC and MVMTaseLC

The Flavivirus RNA genome starts in 5′ with the sequence GpppAGN…, where the first 2 nt after the cap, namely A and G, are strictly conserved. To assess the activity of both MVMTaseSC and MVMTaseLC, we measured the transfer of a radiolabeled methyl group from AdoMet to two short, capped RNA substrates, GpppAC5 and 7MeGpppAC5 (see Materials and Methods). These substrates contain the conserved adenosine but not the guanine on the second position of the RNA. Both substrates had been previously employed to assay the 2′OMTase activity of DVMTase (Egloff et al. 2002); here they are used in a highly purified form. Noncapped pppAC5 was used as a control. The activity assays show that MVMTaseLC could effectively transfer a methyl group to the capped RNA substrates, but not to the noncapped RNA substrate (Fig. 4A). In particular, the extent of methyl transfer was the same for GpppAC5, which in principle can be methylated both at the N7 position of the capping guanine and at the 2′O position of the adenosine, and for the 7MeGpppAC5 substrate, where only methylation at the adenine ribose 2′O site is expected to take place. Our results, therefore, suggest that methyl transfer occurs only at the 2′O position of both substrates.

Figure 4.

MTase activity assay and product analysis. (A) Time course of methyltransfer from [3H]AdoMet to three different RNA substrates followed by filter binding and liquid scintillation counting. The extent of methyltransfer from AdoMet to three different RNA substrates by MVMTaseSC and MVMTaseLC is plotted as a function of time. Data points represent the averages of three (for each MTase) independent experiments and are presented as counts per minute (cpm). In continuous line the MVMTaseLC; in dashed line the MVMTaseSC. (▴) 7MeGpppAC5; (♦) GpppAC5; (▪) pppAC5. (B) HPLC analysis of reaction mixture after 1 h of methyltransfer from AdoMet to 7MeGpppAC5 using MVMTaseLC. (C) HPLC analysis of reaction mixture after 1 h of methyltransfer from AdoMet to GpppAC5 using MVMTaseLC.

To further support such an interpretation, we performed HPLC experiments using two capped RNA substrates and MVMTaseLC (Fig. 4B,C). Analysis of the reaction mixture containing 7MeGpppAC5 and MVMTaseLC allowed separating three peaks (Fig. 4B). The peaks at 23.8 min and 33.9 min (retention times) correspond to AdoHcy and 7MeGpppAC5, respectively, as assessed in parallel runs using standard compounds (not shown). The peak at 37.6 min is attributed to 7MeGpppA2′OMeC5, in analogy with the methyl-transfer reaction catalyzed by the DVMTase domain, which was proved to methylate the adenosine ribose 2′O position by product digestion and subsequent nucleoside-product analysis by TLC and HPLC (Peyrane et al. 2007). The reaction mixture containing GpppAC5 and MVMTaseLC, similarly yielded three peaks (Fig. 4C), the product peak at 38.5 min being attributed to GpppA2′OMeC5. Formation of 7MeGpppAC5 and 7MeGpppA2′OMeC5 single- or double-methyl-transfer products can be excluded in view of their different retention times (Fig. 4B). Additionally, and as stated above, methyl transfer by the highly homologous DVMTase to the adenosine ribose 2′O atom has been previously characterized for this substrate. Taken together, the functional tests complement the structural considerations drawn above, indicating that MVMTaseLC displays a 2′O-MTase activity on the capped short substrates 7MeGpppAC5 and GpppAC5.

In contrast to MVMTaseLC, MVMTaseSC was not able to methylate any of the two capped substrates. Thus, the C-terminal 28 residues of MVMTaseLC seem to be crucial for supporting the activity of the MVMTase domain on these short, capped RNA substrates. It remains to be seen whether or not such an observation applies to other Flavivirus MTase domain short constructs. Interestingly, the 28 C-terminal residues that are missing in MVMTaseSC are not visible in the DVMTase crystal structure, although mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of dissolved crystals showed that they were present in the crystallized protein (Egloff et al. 2002), indicating their structural flexibility even in the ternary complex of the enzyme with AdoHcy and RTP (Benarroch et al. 2004). Based on the present data, however, it is not possible to establish what kind of contribution to the active site structure or to substrate recognition/binding can be provided by these 28 C-terminal residues. Exploration of such a role will require several additional constructs and mutational analyses, which are in progress.

MVMTaseLC proteolytic cleavage

As described in Materials and Methods, we were not able to crystallize MVMTaseLC. Notable differences between the two expressed proteins were immediately evident after their purification: MVMTaseSC was more stable than MVMTaseLC, which showed a marked trend toward aggregation at room temperature. Moreover, MVMTaseLC precipitated partially after storage at −20°C. DLS experiments showed that both the constructs at high concentration (>10 mg/mL) were monodisperse enough (polydispersion 12%–15%) to justify crystallization trials, but that MVMTaseLC tended to aggregate with time (evident after 2–3 d).

Unexpectedly, SDS-PAGE analysis of the expressed MVMTaseLC displayed two distinct bands (of different intensity), both around a molecular weight of 30 kDa (not shown). N-terminal protein sequencing and MS analysis (MALDI-TOF) were performed in order to ascertain the nature of the two bands and assess the possibility of proteolytic events. N-terminal sequencing showed that the two bands result from MVMTaseLC. The most abundant component is the full-length protein, starting with the HHHHHHGPGSTG… sequence, as expected (Fig. 1B). The weaker band, instead, hosts a truncated protein, whose N terminus starts from residue 30 of the MVMTaseLC, with the RAGVMETDR… sequence (Fig. 1B). The MS analysis was in perfect agreement with the sequencing experiment, showing a peak corresponding to the full-length MVMTaseLC (m/z 33,727), and a smaller peak (m/z 29,714) corresponding to a MVMTaseLC protein whose 29 N-terminal residues have been deleted (data not shown).

Since the full-length protein bears the (His)6 N-tag, it was possible to separate the two components by means of a further Ni column run. Strikingly, although the less abundant (lower molecular weight) component was easily separated in the column flow-through, truncation of the isolated MVMTaseLC was subsequently observed again after a few days (data not shown).

Discussion

Two constructs of MVMTase differing by the deletion of a 28-residue C-terminal segment have been expressed and purified. The crystal structure of MVMTaseSC (amino acids 1–265) in complex with AdoMet allows us to localize the active site cleft, and by inference from homologous viral MTases, also the RNA cap binding site. We also have shown that MVMTaseLC (amino acids 1–293) is able to transfer a methyl group to the ribose 2′O atom of the GpppAC5 substrate, yielding GpppA2′OMeC5 as product. Such an observation, in agreement with the results from previous sequence analyses, shows that both TBFVs and MBFVs exert a capping activity that may constitute evolutionary characteristics of the flavivirus lineage, in contrast with the pestivirus and hepacivirus lineages of the Flaviviridae family, which use an internal ribosome entry site strategy for initiating RNA translation.

A recent communication by Ray et al. (2006) reported for the first time that WNVMTase (amino acids 1–300) displays both guanine N7 and ribose 2′O methylation activities, the cap methylation preceding the adenine ribose methylation. Both N7 and 2′O MTase activities, however, were observed only when the 5′-terminal 190 nt of the WNV genome were used as substrate, and disappeared when a generic capped RNA of the same length was employed (Ray et al. 2006).

In the present communication we show that a short capped RNA substrate (GpppAC5) is recognized by MVMTase, being methylated only at the ribose 2′O position. In agreement with our results, the NS5 DVMTase domain shows 2′O MTase activity when tested on the same RNA substrate (Egloff et al. 2002), while no N7MTase activity is observed for either MVMTase or DVMTase. The lack of N7MTase activity could be related to the insufficient size of the capped RNA used and/or to its incorrect nucleotide sequence, particularly for what concerns the presence of a C instead of the conserved G at the second position of Flavivirus genomic RNA.

Our results show that MVMTaseSC does not display any catalytic activity, suggesting that the C-terminal amino acids, deleted in this construct, may be crucial for recognition of the capped RNA. We could not investigate further the structural role played by such a C-terminal segment since MVMTasiLC, likely due to proteolytic event(s) modifying the N-terminal region, could not be crystallized. The WNV MTase domain displaying N7MTase activity is composed of 300 residues (Ray et al. 2006). Such size or sequence differences might also be responsible for the lack of N7MTase activity in MVMTaseLC and DVMTase. From sequence alignments of several Flavivirus MTase domains it can be noticed that their C-terminal ends display a higher level of residue variability relative to the preceding part of the protein (Fig. 1B). In agreement with the results here reported, and with the RNA substrate specificity shown by Ray et al. (2006) on WNV MTase, we propose that within the viral MTase family, the protein C-terminal region plays a role in capped RNA recognition and correct positioning of the guanine N7 methylation site first and of the ribose 2′O site subsequently.

As suggested by the relevance of residue Asp146 in the methylation process (Ray et al. 2006), guanine N7 methylation should occur at the same site described for ribose 2′O methylation. This would imply the achievement of two different capped RNA/enzyme binding modes: (1) The guanine cap binds to the active site for methyl transfer to N7 and (2) the guanine cap binds to the cap recognition site, locating the first RNA adenine in the active site for 2′O methylation. The transition between the two bound states may be driven by the N7-methylation/AdoMet-demethylation-release/AdoMet-binding. The role of the MTase C-terminal region in RNA recognition and the putative transition mechanisms between the two RNA binding modes remain to be investigated.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification

The expression and the purification of MVMTaseSC have been described (Mastrangelo et al. 2006). MVMTaseLC was expressed and purified following essentially the same experimental protocol. MVMTaseSC was concentrated to 17.4 mg mL−1 in a medium containing 800 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 50 mM bicine (pH 7.5) using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (cutoff 10 kDa), and employed as such for crystallization as well as biochemical assays. MVMTaseLC was concentrated to 11 mg mL−1 in the same medium and analogously used for crystallization screens and biochemical assays.

Dynamic light scattering

The purified proteins were centrifuged at 13.000g for 10 min prior to dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis; all measurements were carried out at 20°C in a DynaPro instrument (ProteinSolutions). The DLS data showed that both the proteins were 12%–15% polydisperse, thus suitable for crystallization experiments (Zulauf and D'Arcy 1992; Ferre-D'Amare and Burley 1994).

Crystallization and data collection

Vapor-diffusion crystallization experiments were prepared using an Oryx-6 crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments), as previously described (Mastrangelo et al. 2006); at this stage, however, no crystals were obtained after 2 mo at 21°C. Crystal screening trials were then set up adding 10 mM AdoMet to the protein stock solutions. Very few crystals of MVMTaseSC were obtained after 2 mo in 20% PEGMME 2000, NiCl2 0.01 M, Tris 0.1 M (pH 8.5). In contrast, no crystals were ever obtained for MVMTaseLC.

MVMTaseSC crystals, flash cooled to 100 K following transfer in the crystallization mother liquor supplemented with 20% glycerol for cryoprotection, diffracted to 2.9 Å resolution using synchrotron radiation (ID 29 beamline, ESRF-Grenoble, France). The diffraction data were processed with MOSFLM (Steller et al. 1997), and intensities were merged with SCALA (CCP4 1994), showing that the MVMTaseSC crystals belong to the tetragonal space group P43 (or enantiomorph), with unit cell parameters a = b = 83.0 Å, c = 170.2 Å. The calculated crystal packing coefficient (VM = 2.5 Å3 Da−1) suggests the presence of four MVMTaseSC molecules per asymmetric unit.

Structure determination and refinement

The crystal structure of MVMTaseSC was solved by molecular replacement (program MOLREP; Vagin and Teplyakov 1997) using the DVMTase structure as a search whole model (PDB code 1R6A; residues not identical in the two sequences were trimmed to Ala). Four enzyme molecules were promptly located in the crystal asymmetric unit (R-gen 46.3%, at 2.9 Å resolution). The four MVMTaseSC molecules were then subjected to rigid-body refinement, and refined using REFMAC5 (Winn et al. 2001). A random set comprising 5% of the data was omitted from refinement for R free calculation. Inspection of difference Fourier maps at this stage showed a strong residual density feature compatible with one AdoMet molecule (not present in the search model) for each protein in the asymmetric unit, which was accordingly model built. Simulated annealing refinement (Brünger et al. 1998), followed by manual rebuilding and additional refinement, was subsequently performed (R gen 24.7%, R free 33.0%). Water molecules were manually located and fitted to difference electron density using the program O (Jones et al. 1991). TLS refinement was used in the final refinement stages (Schomaker and Trueblood 1968) (R gen 23.1%, R free 30.6%). Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The stereochemical quality of the model was checked using the program Procheck (Laskowski et al. 1993). Analysis of the Ramachandran plot showed that 91% of the nonglycine residues fall in the most favorable region, and 9% are in the additionally allowed regions (Table 1). Atomic coordinates and structure factors for MVMTaseSC have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al. 2000), with accession code 2OXT.

MTase activity assays

The methyltransferase activity assays were performed in 50-μL samples containing 40 mM Tris (pH 7.5) 5 mM DTT, 5 μM AdoMet (2 μCi [3H]AdoMet; Amersham Biosciences), 1 μM enzyme (MVMTaseLC or MVMTaseSC), and 2 μM of RNA substrate. RNA substrates GpppAC5 and 7MeGpppAC5 were prepared as described (Peyrane et al. 2007). The pppAC5 control substrate was produced using the same protocol and ATP instead of cap analogs. Reactions were incubated at 30°C. At given time intervals 12-μL samples were drawn and spotted into 96-well sample plates containing 100 μL of 20 μM AdoHcy per well to stop the reaction. The samples were then transferred to glass-fiber filtermats (DEAE filtermat, Wallac) by a Filtermat Harvester (Packard Instruments). Filtermats were washed twice with 0.01 M ammonium formate (pH 8.0), twice with water, and once with ethanol, dried, and transferred into sample bags. Liquid scintillation fluid was added, and methylation of RNA substrates was measured in counts per minute (cpm) using a Wallac MicroBeta TriLux Liquid Scintillation Counter. For reactions analyzed by HPLC radiolabeled AdoMet was omitted. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 1 h and then stopped in dry ice. Twenty-five microliters of the reaction mix were injected in a Waters model 600 gradient HPLC. As reference solution we used the reaction mix without the enzyme. A precolumn (Delta-pak C18 100 Å. 5 μm, 3.9 × 20 mm) and a column (Nova-pak C18, 4 μm, 3.9 × 150 mm) were installed in parallel on a two 7000 Rheodyne valve system (Interchim). HPLC eluents were prepared daily: Eluent A was a 0.05 M solution of triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) (pH 7.4) and eluent B was a 1:1 mixture of CH3CN and TEAB (final concentration 0.05M, pH 7.4). The experiment was run at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and started with 3-min elution (100% eluent A) on the precolumn to remove the protein material. The analytical gradient started after 5 min at 100% eluent A with an increase to 10% eluent B after 25 min, to 20% after 35 min, to 30% after 45 min, and to 50% after 50 min.

N-terminal protein sequencing

About 250 pmol of three different preparations of MVMTaseLC were loaded onto two 4%–20% Tris–glycine gels (Invitrogen) and electrophoresed at 150 V for 45 min in the running buffer (Tris 25 mM, glycine 192 mM, SDS 3.5 mM). After electrophoresis, one gel was stained with Coomassie Blue for the control; the other, sandwiched between a sheet of PVDF membrane (Immobilion™-P, Millipore) and several sheets of blotting paper, was assembled into a blotting apparatus (Biorad) and electroeluted for 30 min in transfer buffer (10 mM CAPS, 10% [v/v] MeOH). The PVDF membrane was then stained with Coomassie Blue and the two bands were cut out with a clean razor. N-terminal sequences of the two bands were determined using an automated Protein Sequencer (Applied Biosystems Model 492 Procise) (Matsudaira 1987).

Mass spectrometry analysis

Matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI–TOF) mass spectrometry was performed using a Bruker Daltonics Reflex IV instrument equipped with a nitrogen laser (337 nm) and operated in linear mode with a matrix of sinapinic acid. External standards were used for calibration (Bruker peptide calibration standard). Each spectrum was accumulated for at least 200 laser shots.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nadege Brisbarre (University of Marseille, France), Karen Dalle, Violaine Lantez, Marie-Pierre Egloff, and Bruno Coutard (CNRS, Marseille, France), and Ernest Gould and Naomi Forrester (CEH Oxford, UK), for collaboration during the early stages of this study. We are particularly grateful to Dr. Gabriella Tedeschi (Milano, Italy) for help in N-terminal protein sequencing and mass spectrometry. This work is supported by the EU IP Project Vizier (CT 2004- 511960, to B.C., X.D.L., and M.B.), by the Région Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur (B.C.), and by the Italian Ministry for University and Scientific Research FIRB grant “Biologia Strutturale” (M.B.). M.B. is grateful to CIMAINA (University of Milano), and to Fondazione CARIPLO (Milano, Italy) for continuous support.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Martino Bolognesi. Department of Biomolecular Sciences and Biotechnology, University of Milano, Via Celoria, 26, I-20133 Milano, Italy; e-mail: martino.bolognesi@unimi.it; fax: 39 0250314895.

Abbreviations: N7MTase, (guanine-N7)-methyltransferase; 2′OMTase, (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase; AdoMet, S-adenosyl-L-methionine; AdoHcy, S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine; DV, Dengue virus; WNV, West Nile virus; MV, Meaban virus; TBFV, tick-borne flavivirus; MBFV, mosquito-borne flavivirus; NKV, virus with no known vector.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.072758107.

References

- Ahola T. and Kaariainen, L. 1995. Reaction in alphavirus mRNA capping: Formation of a covalent complex of nonstructural protein nsP1 with 7-methyl-GMP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 17: 507–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch D., Egloff, M.P., Mulard, L., Guerreiro, C., Romette, J.L., and Canard, B. 2004. A structural basis for the inhibition of the NS5 dengue virus mRNA 2′-Omethyltransferase domain by ribavirin 5′-triphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 35638–35643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugl H., Fauman, E.B., Staker, B.L., Zheng, F., Kushner, S.R., Saper, M.A., Bardwell, J.C., and Jakob, U. 2000. RNA methylation under heat shock control. Mol. Cell 6: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujnicki J.M., Feder, M., Radlinska, M., and Rychlewski, L. 2001. mRNA:guanine-N7 cap methyltransferases: Identification of novel members of the family, evolutionary analysis, homology modeling, and analysis of sequence–structure–function relationships. BMC Bioinformatics 2: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastel C. 1980. Tick-borne arboviruses associated with marine birds; a general review (author's transl.). Med. Trop. 40: 535–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastel C., Main, A.J., Guiguen, C., le Lay, G., Quillien, M.C., Monnat, J.Y., and Beaucournu, J.C. 1985. The isolation of Meaban virus, a new Flavivirus from the seabird tick Ornithodoros (Alectorobius) maritimus in France. Arch. Virol. 83: 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Comutational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Cryst. D 50: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff M.P., Benarroch, D., Selisko, B., Romette, J.L., and Canard, B. 2002. A structural basis for the inhibition of the NS5 dengue virus mRNA 2′-O-methyltransferase domain by ribavirin 5′-triphosphate. EMBO J. 21: 2757–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faumann E.B., Blumental, R.M., and Cheng, X. 1999. The emergence of fruiting bodies in Basidiomycetes. In S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase: Structure and functions (eds. X. Cheng and R.M. Blumenthal), pp. 1–38. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore.

- Ferre-D'Amare A.R. and Burley, S.K. 1994. Use of dynamic light scattering to assess crystallizability of macromolecules and macromolecular assemblies. Structure 25: 357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields B.N., Howley, P.M., Griffin, D.E., Lamb, R.A., Martin, M.A., Roizman, B., Straus, S.E., and Knipe, D.M. 2001. Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippicott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- Grard G., Moureau, G., Charrel, R.N., Lemasson, J.-J., Gonzalez, J.-P., Gallian, P., Gritsun, T.S., Holmes, E.C., Gould, E.A., and de Lamballerie, X. 2006. Genetic characterization of tick-borne flaviviruses: New insights into evolution, pathogenetic determinants and taxonomy. Virology DOI 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hodel A.E., Gershon, P.D., Shi, X., and Quiocho, F.A. 1996. The 1.85 Å structure of vaccinia protein VP39: A bifunctional enzyme that participates in the modification of both mRNA ends. Cell 85: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel A.E., Gershon, P.D., and Quiocho, F.A. 1998. Structural basis for sequence nonspecific recognition of 5′-capped mRNA by a cap-modifying enzyme. Mol. Cell 1: 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingrosso D., Fowler, A.V., Bleibaum, J., and Clarke, S. 1989. Sequence of the D-aspartyl/L-isoaspartyl protein methyltransferase from human erythrocytes. Common sequence motifs for protein, DNA, RNA, and small molecule S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 20131–20139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou, J.Y., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard, M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. and Sander, C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22: 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E.V. 1993. Computer-assisted identification of a putative methyltransferase domain in NS5 protein of flaviviruses and λ 2 protein of reovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 74: 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24: 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26: 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Malone T., Blumenthal, R.M., and Cheng, X. 1995. Structure-guided analysis reveals nine sequence motifs conserved among DNA amino-methyltransferases, and suggests a catalytic mechanism for these enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 253: 618–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo E., Bollati, M., Milani, M., de Lamballerie, X., Brisbare, B., Dalle, K., Lantez, V., Egloff, M.P., Coutard, B., Canard, B., et al. 2006. Preliminary characterization of (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase crystals from Meaban and Yokose flaviviruses. Acta Crystallogr. F 62: 768–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira P.T. 1987. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. and Song, H. 2004. The enzymes and control of eukaryotic mRNA turnover. Nat. Struct. Biol. 11: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrane F., Selisko, B., Decroly, E., Vasseur, J.J., Benarroch, D., Canard, B., and Alvarez, K. 2007. High-yield production of short GrppA- and 7MeGpppA-capped RNAs and HPLC-monitoring of methyltransfer reactions at the guanine-N7 and adenosine-2′ O positions. Nucleic Acids Res. DOI doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl 1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Posfai J., Bhagwat, A.S., Posfai, G., and Roberts, R.J. 1989. Predictive motifs derived from cytosine methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 17: 2421–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton E., Nicholas, M.C.S., Krissinel, E., Cowtan, K., and Noble, M. 2002. The CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr. D 58: 1955–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D., Shah, A., Tilgner, M., Guo, Y., Zhao, Y., Dong, H., Deas, T.S., Zhou, Y., Li, H., and Shi, P.Y. 2006. West Nile virus 5′-cap structure is formed by sequential guanine N-7 and ribose 2′-O methylations by nonstructural protein 5. J. Virol. 80: 8362–8370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinsch K.M., Nibert, M.L., and Harrison, S.C. 2000. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 404: 960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomaker V. and Trueblood, K.N. 1968. On the rigid-body motion of molecules in crystals. Acta Crystallogr. B 24: 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Steller I., Bolotovsky, R., and Rossmann, M. 1997. An algorithm for automatic indexing of oscillation images using Fourier analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30: 1036–1040. [Google Scholar]

- St. George T.D., Standfast, H.A., Doherty, R.L., Carley, J.G., Fillipich, C., and Brandsma, J. 1977. The isolation of Saumarez Reef virus, a new flavivirus, from bird ticks Ornithodoros capensis and Ixodes eudyptidis in Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci 55: 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A. and Teplyakov, A. 1997. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30: 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Boisvert, D., Kim, K.K., Kim, R., and Kim, S.H. 2000. Crystal structure of a fibrillarin homologue from Methanococcus jannaschii, a hyperthermophile, at 1.6 Å resolution. EMBO J. 19: 317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M.D., Isupov, M.N., and Murshudov, G.N. 2001. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D 57: 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulauf M. and D'Arcy, A. 1992. Light scattering of proteins as a criterion for crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 122: 102–106. [Google Scholar]