Abstract

The X-ray crystal structure of the 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MCS) from Arabidopsis thaliana has been solved at 2.3 Å resolution in complex with a cytidine-5-monophosphate (CMP) molecule. This is the first structure determined of an MCS enzyme from a plant. Major differences between the A. thaliana and bacterial MCS structures are found in the large molecular cavity that forms between subunits and involve residues that are highly conserved among plants. In some bacterial enzymes, the corresponding cavity has been shown to be an isoprenoid diphosphate-like binding pocket, with a proposed feedback-regulatory role. Instead, in the structure from A. thaliana the cavity is unsuited for binding a diphosphate moiety, which suggests a different regulatory mechanism of MCS enzymes between bacteria and plants.

Keywords: plant enzymes, MEP pathway, isoprenoid-binding proteins, cytidine-5-monophosphate, zinc ions

Isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) are the universal five-carbon precursors of isoprenoids, one of the largest family of natural products accounting for more than 30,000 molecules of both primary and secondary metabolism (McGarvey and Croteau 1995; Sacchettini and Poulter 1997). After the discovery of the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway in yeast and animals, it was assumed that IPP was synthesized from acetyl-CoA via MVA and then isomerized to DMAPP in all organisms (McGarvey and Croteau 1995; Chappell 2002). However, an alternative MVA-independent pathway for the biosynthesis of IPP was later identified in bacteria (Flesch and Rohmer 1988; Rohmer et al. 1993) and plants (Lichtenthaler et al. 1997; Lichtenthaler 1999) and was named the MEP pathway according to its first committed precursor, 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (Rodriguez-Concepcion and Boronat 2002; Testa and Brown 2003).

In the synthesis of isoprenoids, the MEP pathway is the only one present in most eubacteria, including the causal agents for diverse and serious human diseases like leprosy, bacterial meningitis, various gastrointestinal and sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and certain types of pneumonia. The MEP pathway is the only one present in some protozoans, such as in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. In turn, the MEP pathway is absent from Archaea, fungi, and animals that synthesize their isoprenoids exclusively through the MVA pathway (Eisenreich et al. 1998; Rohmer 1999; Boucher and Doolittle 2000; Rodriguez-Concepcion and Boronat 2002; Testa and Brown 2003; Rohmer et al. 2004). Plants use both pathways, although they localize in different cellular compartments: the chloroplasts and the cytoplasm for the MEP and the MVA pathways, respectively (Rodriguez-Concepcion and Boronat 2002). Given the essential nature of the MEP pathway and its absence in mammals, the enzymes comprising the MEP pathway represent potential targets for the generation of selective antibacterial, antimalarial, and herbicidal compounds (Jomaa et al. 1999; Lichtenthaler et al. 2000; Rodriguez-Concepcion and Boronat 2002; Testa and Brown 2003; Rohmer et al. 2004).

As part of a general study about isoprenoid synthesis in plants, we have investigated the enzyme 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MCS, E.C. 4.6.1.12) from the fifth stage of the MEP pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. MCS converts 4-diphosphocytidyl 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2-phosphate (CDP-MEP) to 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MECDP) and cytidine-5-monophosphate (CMP). The MCS enzyme from Escherichia coli, encoded by the ispF gene, was the first to be identified (Herz et al. 2000), and since then homologs from a number of microorganisms and plants have been characterized (Rodriguez-Concepcion and Boronat 2002; Testa and Brown 2003; Gao et al. 2006; Hsieh and Goodman 2006).

The three-dimensional structures of five bacterial MCS enzymes have been reported: from E. coli (Kemp et al. 2002; Richard et al. 2002; Steinbacher et al. 2002), Haemophilus influenzae (Lehmann et al. 2002), the thermophile Thermus thermophilus (Kishida et al. 2003), Shewanella oneidensis (Ni et al. 2004), and the MCS domain of a bifunctional IspDF enzyme from Campylobacter jejuni (Gabrielsen et al. 2004). In this work, we present the X-ray crystal structure of the MCS enzyme from A. thaliana, the first determined from a plant. The main structural differences with respect to the bacterial enzymes reside in the organization of the large molecular cavity that forms between the three subunits of the MCS molecule. For bacteria, this cavity is proposed to be an isoprenoid diphosphate-like binding pocket (IPPbp) having a feedback-regulatory function (Richard et al. 2002; Ni et al. 2004; Kemp et al. 2005). In the MCS from A. thaliana, the cavity architecture impedes the binding of diphosphate-containing molecules due to the presence of several residues that are highly conserved in plants. Changes of the effectors that could bind to this cavity appear to imply a different regulatory mechanism of the MEP pathway between bacteria and plants.

Results and Discussion

Overall structure

The MCS enzyme from A. thaliana was heterologously expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) lacking 52 of the N-terminal end residues predicted to have typical features of plastid targeting peptides (PTP) by the ChloroP algorithm (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP). This prediction is consistent with the subcellular localization of the MEP pathway in chloroplasts (data not shown). The purified protein, including the MCS residues from 52 to 231 and a C-terminal His6 tag, gave cubic crystals that contained one polypeptide in the asymmetric unit of the crystal (▶). The final model, refined at 2.3 Å resolution, comprises residues from Thr72 to Lys231, one chloride ion, one Zn2+ metal ion, one CMP molecule, and 68 water molecules. The quality of the electron-density maps allowed the precise tracing of most residues' side chains, with the exception of the surface loop from Ser138 to Lys143 located near the active site. The 21 residues at the N-terminal end, from the MCS coding sequence, and the 8 C-terminal end residues, corresponding to the histidine tag used, were not defined in the electron density and consequently have not been included in the present model. The main-chain conformational angles of 91% of the residues fall within the most favorable region of the Ramachandran plot, with only Lys143 in the disallowed region.

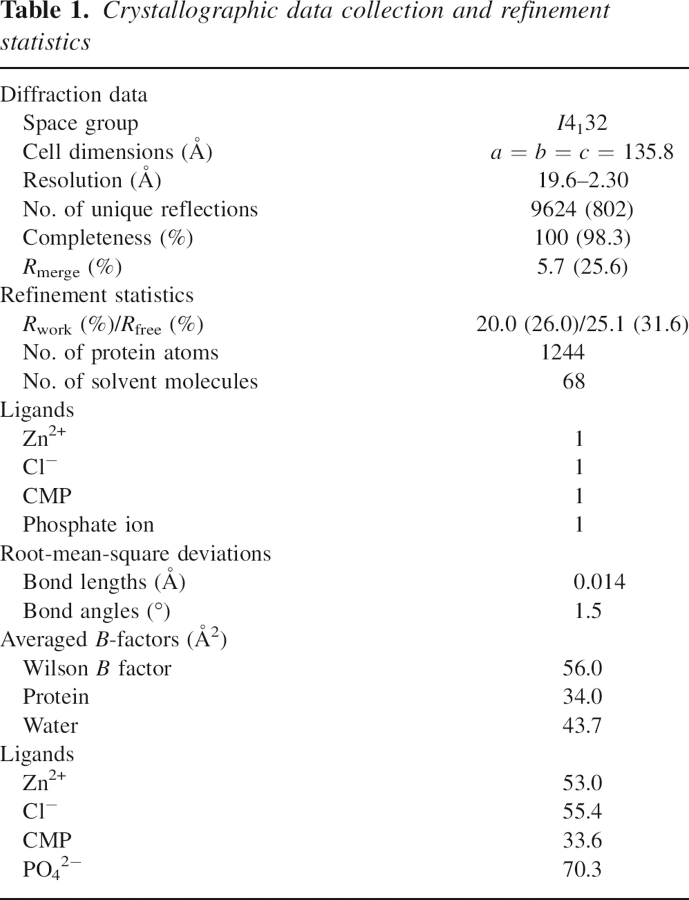

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

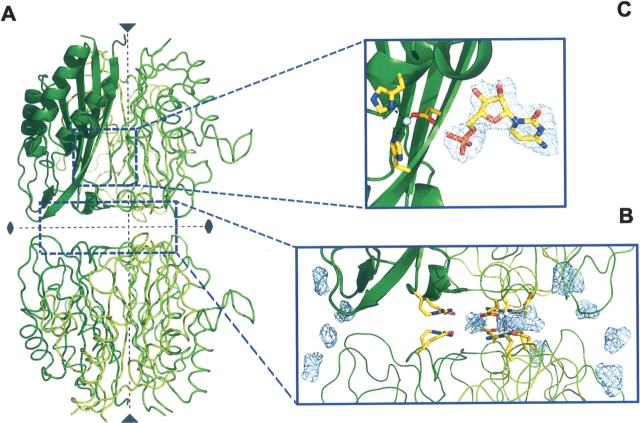

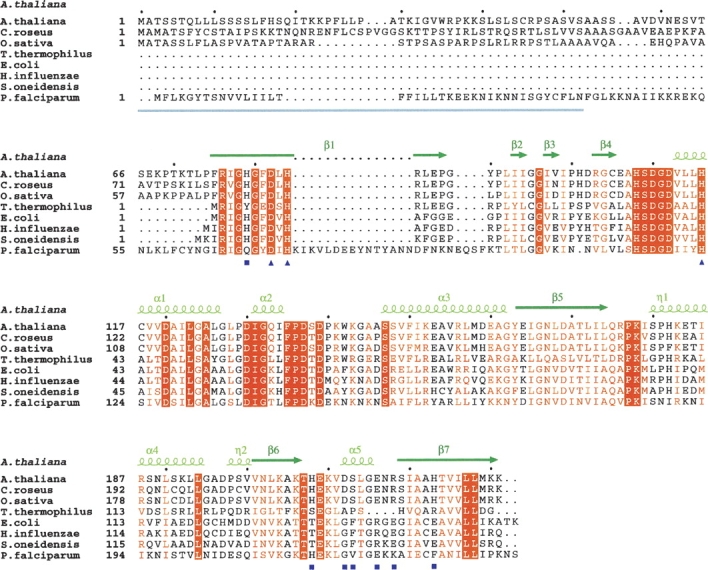

The superimposition of the structures from the MCS subunits of A. thaliana and E. coli, with a sequence identity of 32% (▶), gives a RMSD of only 0.99 Å for 155 (97%) structurally equivalent Cα atoms. The subunit is organized as a single structural domain, including a long four-stranded mixed β-sheet and three α-helices located on one side of the sheet (a cartoon representation of the monomer is shown in ▶). In the crystal of MCS from A. thaliana, six neighbor monomers with large contact surfaces are related by ternary and binary crystallographic symmetries with a D3 point group symmetry (▶). However, gel-filtration studies indicate that, in solution, the MCS molecule from A. thaliana is a trimer, similarly to what had been observed in the bacterial enzymes (data not shown). In fact, the three subunits that relate by the crystal threefold axis in the A. thaliana structure give a RMSD of only 1.07 Å when superimposed to the equivalent Cα atoms of the MCS molecular trimers from E. coli. These MCS trimers have a length of ∼48 Å along the threefold symmetry axis and are shaped like extended trigonal prisms with a flat-bottom side, of ∼34 Å in diameter, and a narrower top side (▶). The β-sheets of the three subunits face one another, defining an internal β-barrel like structure that is surrounded by the α-helices on the external surface of the trimer. In the trimer, extensive inter-subunit interactions define a network of complementary hydrophobic contacts, electrostatic interactions, and specific hydrogen bonds, similarly to what was described for the bacterial MCS enzymes (Kemp et al. 2002; Lehmann et al. 2002; Richard et al. 2002; Steinbacher et al. 2002; Ni et al. 2004).

Figure 1.

Multiple alignment of plant and bacterial MCS proteins. Sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program (http://ebi.ac.uk/clustalw). The secondary-structure elements, assigned according to the A. thaliana MCS structure, are depicted with dark-green arrows for β-strands and light-green helices for η- and α-helices. The N-terminal region corresponding to the PTP absent from bacterial MCS proteins is underlined in gray. Residues that are identical in all sequences are highlighted against an orange background, and those that are highly homologous are written in orange. Active site residues are marked by dark-blue squares, and residues of the molecular cavity are marked by dark-blue triangles.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the A. thaliana MCS enzyme and details of the active site architecture. (A) MCS subunit from A. thaliana found in the crystal asymmetric unit (cartoon representation) together with five neighbor subunits (represented as ribbons) related by the two- and threefold crystal symmetries shown as dashed lines (see in the text). Molecules in solution correspond to the trimers formed by the three subunits that are related by the crystal threefold axis. (B) Close-up view of the interface of the two neighbor trimers with some fragments of unexplained electron density. The conserved residues at the cavity entrance, Glu216 and Arg218, together with the symmetry-related pairs are represented as atom-colored sticks. (C) Conserved active site residues Asp82, His84, and His116, coordinate tetrahedrally with a Zn2+ ion (shown as a light-blue sphere). The CMP molecule is shown as atom-colored sticks with its corresponding 2F o−F c electron density contoured at 1σ. The MCS orientation here is derived from the view in panel A following a 45° rotation around the vertical (threefold) axis.

Active site architecture

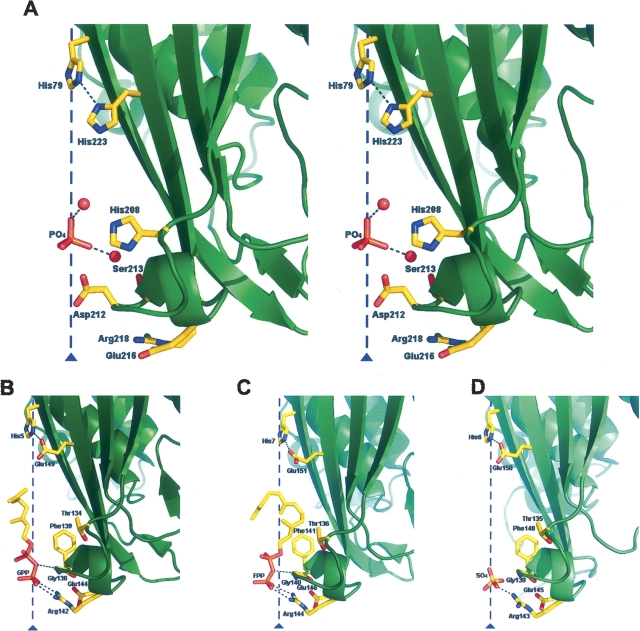

In the A. thaliana structure, active sites span into two adjacent monomers. This confirms the relevance of the trimer as the active biological assembly also in plants. A Zn2+ ion at the base of the active site pocket presents tetrahedral coordination with the highly conserved residues Asp82, His84, and His116 (A. thaliana numbering, ▶, ▶) and a solvent molecule or a phosphate ion with partial occupancy. The active site architecture of MCS appears extremely well conserved among bacteria and plants as reflected in the binding of CMP that retains strictly all the interactions with the MCS main chain. In the reaction catalyzed by MCS, CMP acts as the leaving group to give the cyclic diphosphate reaction product MECDP. The active site residues and the CMP molecule are very well defined in the electron density map of the A. thaliana structure, with a clear fit of the pyrimidine base and the ribose ring (▶). In the majority of the known MCS structures, solved in complex either with the reaction substrate or analogs or with products, a second divalent metal ion was found fixing the α and β phosphate groups of the CDP moiety (Kemp et al. 2002; Steinbacher et al. 2002; Kishida et al. 2003; Sgraja et al. 2005). No hints of a second bound metal were found in the A. thaliana structure complexed with CMP.

Inter-subunits' binding cavity

In the MCS homotrimer from A. thaliana, the β-sheets of the three subunits define an internal cavity ∼15 Å in length along the ternary symmetry axis (▶). An equivalent, somewhat larger, cavity was found in the bacterial enzymes and shown to be an isoprenoid diphosphate-like binding pocket (IPPbp) with a proposed product feedback regulatory function through a yet undetermined mechanism (Richard et al. 2002; Ni et al. 2004; Kemp et al. 2005), which might be related with the trimer stability. However, such a cavity is absent in the thermophilic MCS enzyme from Thermus thermophilus, where packing of subunits is tighter and likely more stable according to ultracentrifugation data (Kishida et al. 2003).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the molecular cavity found in MCS enzymes between the A. thaliana and the bacterial enzymes. Cartoon representations of MCS subunits from different organisms: (A) A. thaliana (stereoview), (B) E. coli, (C) S. oneidensis, and (D) H. influenzae. Representative residues from the molecular cavity, which extends along the molecular threefold axis, are explicitly shown as atom-colored sticks. In each structure, the ligand found inside the cavity is also shown. The singularity of the plant enzyme, mainly due to the presence and disposition of Asp212, suggests that the binding of isoprenoid diphosphate-like molecules would not occur in the plant enzymes, contrary to what had been demonstrated for the bacterial enzymes.

In the A. thaliana structure, a network of hydrogen-bond interactions, involving residues His79 and His223 from the three subunits (▶), conforms the top of the cavity. The two histidine residues are highly conserved in plants, while the position corresponding to His223 varies in the bacterial enzymes, most often being a glutamate (▶, ▶). A network of interactions extends from His79 throughout residues Thr171*, Lys204*, and Asp120 (*residues from symmetry-related equivalent, A. thaliana numbering) bridging the cavity with the active site pocket.

In A. thaliana the walls of the cavity are lined with hydrophobic (Phe81, Leu83, Ile173, Leu214) and polar (His208, Asp212, Ser213) residues, not well preserved between plants and bacteria (▶). In the lower part of the cavity, Asp212 forms a narrow negatively charged ring with the corresponding carboxylate groups at only 2.54 Å from the threefold axis (▶). An aspartate in this position appears to be a highly conserved feature among the plant MCS enzymes, while in bacteria the position corresponds to residues with small side chains, such as Gly138 in E. coli (▶, ▶). The bottom of the cavity presents an aperture that is defined by a ring of salt bridges, involving residues Glu216 and Arg218 from the three subunits (▶). These charged residues are highly conserved in MCS sequences, although in bacteria their positions are interchanged (▶, ▶).

The A. thaliana cavity is occupied by bulky fragments of electron density whose interpretation appears to be complicated by the averaging effect of the threefold crystal symmetry. Electron density had also been found inside the cavities of other reported MCS structures (Kemp et al. 2002; Lehmann et al. 2002; Richard et al. 2002; Ni et al. 2004). For the bacterial structures from E. coli (Richard et al. 2002; Kemp et al. 2005), S. oneidensis (Ni et al. 2004), and C. jejuni (IspDF, a bifunctional enzyme); (Gabrielsen et al. 2004), the electron density inside the cavity was interpreted as GPP or as farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) with the diphosphate moieties positioned along the molecular threefold axis and the α-phosphate group interacting with the arginines at the cavity entrance (▶). For the H. influenzae structure (Ni et al. 2004), the density inside the cavity was interpreted as a sulfate ion interacting with the arginines at the cavity entrance (▶). In the A. thaliana structure, the first fragment of density inside the cavity is located above Asp212, far from the corresponding arginine (Arg218) at the cavity entrance. For this density a phosphate ion was modeled interacting, throughout water molecules, with the side chains of His208 and of its symmetry mates (▶). Therefore, the peculiarities of the cavity in the plant enzymes are suited for the binding of molecules with a monophosphate moiety, although they discard, in particular due to the presence of Asp212, the binding of diphosphate-containing molecules, such as isoprenoids GPP or FPP.

Conclusions

The first crystal structure from a plant MCS enzyme has been determined, in complex with a CMP molecule. The molecular trimeric organization and the overall structure of subunits, in particular the arrangement of the catalytically essential residues and of the Zn2+ ion in the active site, are closely related to the ones from the known structures of the bacterial enzymes. Main differences between the plant and the bacterial MCS structures concentrate in the cavity that exists between subunits along the molecular threefold axis and involve residues that are highly conserved among plants. These differences suggest that the binding of isoprenoid diphosphate-like molecules in the cavity of the plant MCS enzymes would not occur, contrary to what had been demonstrated for some bacterial enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of the IspF gene from A. thaliana

The coding sequence of the mature chloroplastic MCS from A. thaliana (Q9CAK8) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using high-fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) from the plasmid pET23b-MCS encoding the entire form of the protein. This plasmid was previously obtained by RT-PCR using a pool of mRNAs isolated from the wild-type ecotype Columbia 0 of A. thaliana. The 52 N-terminus amino acids that correspond to the transit peptide as predicted by the CloroP algorithm (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP) were truncated using the ygbBFor (5′-ATACATATGGCTGCTTCTTCCGCCGTCGACGTCA-3′) and the ygbBRev (5′-CAGCTCGAGTTTCTTCATGAGGAGAATAACAGTG-3′) oligonucleotides that introduce an NdeI and a XhoI restriction site (in italic), respectively. The sequence was inserted into a SmaI site in a pBluescript SK (Stratagene) cloning vector, and the resulting construct was double-digested with NdeI/XhoI and subcloned into a pET23b vector (Novagen), digested with the same restriction enzymes. This construct allowed the production of a recombinant form of the mature MCS protein in E. coli with a C-terminal extension of eight amino acids (LEHHHHHH).

Expression and purification of MCS

The pET23b-MCS clone was heterologously expressed in E. coli BL21 (pLysS). One liter of bacterial cells was grown up to an OD600 of 0.5 at 37°C in LB broth. For optimal protein expression, the bacterial culture was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and incubated overnight at 22°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g (4°C), resuspended in 20 mL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 0.5 mM EDTA supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors [Roche]), and lysed by sonication (5 × 30 sec, 30 W). The lysate was then incubated with 1% (w/v) protamine sulfate, and the soluble fraction was obtained by centrifugation at 20,000g for 45 min at 4°C. The recombinant protein present in the cleared lysate was purified through a Ni2+ affinity chromatography column (GE Healthcare), and the total protein yield was ∼60 mg of recombinant protein per liter of culture. This protein sample was loaded into a Superdex 200 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) for further purification, and the protein was then concentrated to 6 mg/mL.

Crystal preparation and structure determination

Crystals of the MCS protein were obtained by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method at 20°C. Drops were assembled from 1 μL of protein solution (at a concentration of 6 mg/mL) containing 2 mM CMP and 2 mM MgCl2 in 40 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 1 μL of reservoir solution composed of 100 mM MES (pH 6.0), 200 mM NH4H2PO4, and 18% (w/v) PEG 3350. The crystals, belonging to the cubic space group I4132, contained one protein subunit per asymmetric unit and grew within 5 d to a maximum final size of 0.2 mm. Macroseeding was necessary for reproducible crystallization.

Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen in the presence of 20% (v/v) glycerol. Diffraction data, collected to 2.3 Å resolution in the ESRF beamline ID29, were indexed, integrated, and scaled using DENZO/SCALEPACK (▶ [Otwinowski and Minor 1997]). General data handling was carried out with programs from the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 1994). The structure was determined by molecular replacement with the program MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov 1997) using the E. coli MCS structure (PDB accession code 1GX1) as the search model. Model completion and rebuilding were performed interactively with the graphics program COOT (Emsley and Cowtan 2004). Solvent molecules, CMP, Zn2+, and Cl− were identified by inspection of electron density and difference density maps. Coordinates and temperature B factors were refined using REFMAC (▶; Murshudov et al. 1997).

Figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano 2002). Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited at the PDB under accession code 2PMP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to S.I. from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (BIO 2002-04419-C02-02), University of Barcelona (ACES-UB 2006), and Generalitat de Catalunya (2005SGR00914). We also acknowledge a grant to I.F. from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (BFU2005-08686-C02-01). B.C. acknowledges a predoctoral fellowship from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia (BES2006-11539).

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Ignacio Fita, Institut de Biologia Molecular de Barcelona-CSIC and Institut de Recerca Biomedica, Parc Cientific de Barcelona, Josep Samitier 1-5, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; e-mail: ifrcri@ibmb.csic.es; fax: +34-904-034-979.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.072972807.

References

- Boucher Y. and Doolittle, W.F. 2000. The role of lateral gene transfer in the evolution of isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 37 703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell J. 2002. The genetics and molecular genetics of terpene and sterol origami. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (CCP4) 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, http://www.pymol.org.

- Eisenreich W., Schwarz, M., Cartayrade, A., Arigoni, D., Zenk, M.H., and Bacher, A. 1998. The deoxyxylulose phosphate pathway of terpenoid biosynthesis in plants and microorganisms. Chem. Biol. 5 R221–R233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. and Cowtan, K. 2004. COOT: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch G. and Rohmer, M. 1988. Prokaryotic hopanoids: The biosynthesis of the bacteriohopane skeleton. Formation of isoprenic units from two distinct acetate pools and a novel type of carbon/carbon linkage between a triterpene and d-ribose. Eur. J. Biochem. 175 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsen M., Bond, C.S., Hallyburton, I., Hecht, S., Bacher, A., Eisenreich, W., Rohdich, F., and Hunter, W.N. 2004. Hexameric assembly of the bifunctional methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase and protein—protein associations in the deoxy-xylulose–dependent pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279 52753–52761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Lin, J., Liu, X., Deng, Z., Li, Y., Sun, X., and Tang, K. 2006. Molecular cloning, characterization and functional analysis of a 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase gene from ginkgo biloba. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39 502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz S., Wungsintaweekul, J., Schuhr, C.A., Hecht, S., Luttgen, H., Sagner, S., Fellermeier, M., Eisenreich, W., Zenk, M.H., Bacher, A., et al. 2000. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: YgbB protein converts 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2-phosphate to 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 2486–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M.H. and Goodman, H.M. 2006. Functional evidence for the involvement of Arabidopsis IspF homolog in the non-mevalonate pathway of plastid isoprenoid biosynthesis. Planta 223 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa H., Wiesner, J., Sanderbrand, S., Altincicek, B., Weidemeyer, C., Hintz, M., Turbachova, I., Eberl, M., Zeidler, J., Lichtenthaler, H.K., et al. 1999. Inhibitors of the non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285 1573–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp L.E., Bond, C.S., and Hunter, W.N. 2002. Structure of 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase: An essential enzyme for isoprenoid biosynthesis and target for antimicrobial drug development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 6591–6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp L.E., Alphey, M.S., Bond, C.S., Ferguson, M.A., Hecht, S., Bacher, A., Eisenreich, W., Rohdich, F., and Hunter, W.N. 2005. The identification of isoprenoids that bind in the intersubunit cavity of Escherichia coli 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase by complementary biophysical methods. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida H., Wada, T., Unzai, S., Kuzuyama, T., Takagi, M., Terada, T., Shirouzu, M., Yokoyama, S., Tame, J.R., and Park, S.Y. 2003. Structure and catalytic mechanism of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MECDP) synthase, an enzyme in the non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid synthesis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann C., Lim, K., Toedt, J., Krajewski, W., Howard, A., Eisenstein, E., and Herzberg, O. 2002. Structure of 2C-methyl-d-erythrol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase from Haemophilus influenzae: Activation by conformational transition. Proteins 49 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H.K. 1999. The 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 47–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H.K., Schwender, J., Disch, A., and Rohmer, M. 1997. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids in higher plant chloroplasts proceeds via a mevalonate-independent pathway. FEBS Lett. 400 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H.K., Zeidler, J., Schwender, J., and Muller, C. 2000. The non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis of plants as a test system for new herbicides and drugs against pathogenic bacteria and the malaria parasite. Z. Naturforsch. C 55 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey D.J. and Croteau, R. 1995. Terpenoid metabolism. Plant Cell 7 1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin, A.A., and Dodson, E.J. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S., Robinson, H., Marsing, G.C., Bussiere, D.E., and Kennedy, M.A. 2004. Structure of 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase from Shewanella oneidensis at 1.6 Å: Identification of farnesyl pyrophosphate trapped in a hydrophobic cavity. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 1949–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor, W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S.B., Ferrer, J.L., Bowman, M.E., Lillo, A.M., Tetzlaff, C.N., Cane, D.E., and Noel, J.P. 2002. Structure and mechanism of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase. An enzyme in the mevalonate-independent isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277 8667–8672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Concepcion M. and Boronat, A. 2002. Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 130 1079–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M. 1999. The discovery of a mevalonate-independent pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria, algae and higher plants. Nat. Prod. Rep. 16 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M., Knani, M., Simonin, P., Sutter, B., and Sahm, H. 1993. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria: A novel pathway for the early steps leading to isopentenyl diphosphate. Biochem. J. 295 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M., Grosdemange-Billiard, C., Seemann, M., and Tritsch, D. 2004. Isoprenoid biosynthesis as a novel target for antibacterial and antiparasitic drugs. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5 154–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchettini J.C. and Poulter, C.D. 1997. Creating isoprenoid diversity. Science 277 1788–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgraja T., Kemp, L.E., Ramsden, N., and Hunter, W.N. 2005. A double-mutation of Escherichia coli 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase disrupts six hydrogen bonds with, yet fails to prevent binding of, an isoprenoid diphosphate. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61 625–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbacher S., Kaiser, J., Wungsintaweekul, J., Hecht, S., Eisenreich, W., Gerhardt, S., Bacher, A., and Rohdich, F. 2002. Structure of 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase involved in mevalonate-independent biosynthesis of isoprenoids. J. Mol. Biol. 316 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa C.A. and Brown, M.J. 2003. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway and its significance as a novel drug target. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 4 248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A. and Teplyakov, A. 1997. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]