Abstract

The multifunctional protein, β-catenin, has essential roles in cell adhesion and, through the Wnt signaling pathway, in controlling cell differentiation, development, and generation of cancer. Could distinct molecular forms of β-catenin underlie these two functions? Our single-molecule force spectroscopy of armadillo β-catenin, with molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, suggests a model in which the cell generates various forms of β-catenin, in equilibrium. We find β-catenin and the transcriptional factor Tcf4 form two complexes with different affinities. Specific cellular response is achieved by the ligand binding to a particular matching preexisting conformer. Our MD simulation indicates that complexes derive from two conformers of the core region of the protein, whose preexisting molecular forms could arise from small variations in flexible regions of the β-catenin main binding site. This mechanism for the generation of the various forms offers a route to tailoring future therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, β-catenin, ICAT, MD simulation, Wnt signaling

β-Catenin is a multifunctional protein that is crucial for two important developmental processes, and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of common epithelial malignancies. It connects cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization with the regulation of gene expression through Wnt signaling (Klymkowsky 2005). The Wnt signaling pathway, in which β-catenin acts as a transcriptional coactivator, plays a key role in the control of cell differentiation and development, as well as malignancy (Peifer and Polakis 2000).

These roles of β-catenin require it to interact with several partners, and therefore, the accumulation, intracellular localization, and functions of this protein are tightly regulated. In its adhesive role, a soluble pool of β-catenin interacts with the cytoplasmic tail domains of cadherins and α-catenin (Huber and Weis 2001; Gooding et al. 2004). In its signaling role, in the absence of a Wnt signal, a distinct subcellular pool interacts with the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein (Rubinfeld et al. 1993; Eklof Spink et al. 2001; Ha et al. 2004; Xing et al. 2004) and axin (Spink et al. 2000; Xing et al. 2003), targeting it toward degradation. In the presence of a Wnt signal, the same pool interacts with members of the Lef/Tcf family of transcription factors (Behrens et al. 1996; Graham et al. 2000, 2001; Poy et al. 2001). In a typical cell, the interplay between its interactions with the cytoplasmic tail of transmembrane cadherin adhesion proteins and APC is crucial to keep the balance between a relatively stable pool of β-catenin associated with intercellular adheren junctions and a small and rapidly degraded pool of β-catenin. How the distribution of these two pools is regulated and the nature of the relationship between the two functions of β-catenin remains to be elucidated. Recently, it has been proposed that β-catenin exists in distinct molecular forms with different binding properties (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004a). A cadherin-selective conformation that can target to adhesive complexes and a Tcf-selective form that is targeted to transcription complexes could provide a mechanism by which cells are able to separate these two roles of β-catenin. Furthermore, structural and mutagenesis studies showed that Tcf4 binds to β-catenin using several distinct conformations in the central region of its binding site (Graham et al. 2001; Poy et al. 2001). These findings are in agreement with the “new view” of protein structure and function in which conformational diversity allows multifunctionality and provides a mechanism to regulate protein activity (James and Tawfik 2003).

The interaction between Tcf4 and β-catenin takes place when the cytosolic levels of β-catenin increase and the protein translocates into the nucleus, where upon binding to transcription factors activates the transcription of developmentally important genes as well as proto-oncogenes (Behrens and Lustig 2004). Mutations in APC or β-catenin are responsible for greater than 90% of colorectal cancers and result in the accumulation of nuclear β-catenin and overexpression of Tcf/β-catenin target genes (Giles et al. 2003). This makes the Tcf/β-catenin complex a very attractive target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. A physiological inhibitor of Tcf4/β-catenin interaction, ICAT, was initially described (Tago et al. 2000; Tutter et al. 2001) as a selective inhibitor of the interaction between β-catenin and Tcf/Lef family transcription factors in vivo (Graham et al. 2002), but recently it has been shown to inhibit the cadherin/β-catenin interaction in vivo under certain circumstances (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004b).

In this work, we studied the complex formation of transcriptional factor Tcf4 with β-catenin at the single-molecule level by atomic force microscopy (AFM) to gain insight into the molecular plasticity of this multifunctional protein. Using dynamic force spectroscopy, we found two distinct populations of the armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complex. The fractional occupancy of these two complexes seems to be modified by the presence of ICAT that may be predicted, from our experiments, to block the low-strength population. Furthermore, using molecular dynamics (MD) simulation we provide a rational explanation of how β-catenin may populate two different conformational states, and thus achieve the required specificity for its different ligands and its multifunctional aspect in the cell.

These findings will play an important role in rational drug design, since they show that the dynamic properties of the protein, and hence the existence of various populations of conformers, are important for binding and achieving specificity for different ligands.

Results

Binding of Tcf4 to armadillo β-catenin

The interaction between human Tcf4 and β-catenin has been well characterized at the structural level (Omer et al. 1999; Graham et al. 2001; Knapp et al. 2001; Poy et al. 2001; Fasolini et al. 2003), and involves an elongated structure of Tcf4 that extends along the positively charged superhelical groove of the β-catenin armadillo region, followed by a C-terminal helix formed upon binding to its partner (Knapp et al. 2001). The binding region of Tcf4 (residues 1–57) was expressed with an N-terminal His-tag for noncovalent coupling to the AFM cantilever tip via bifunctional crosslinkers. The C terminus is free for structuring upon complex formation with armadillo β-catenin. A C-terminal His-tag attached to armadillo β-catenin allowed us to control its immobilization onto the mica surface.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was employed to check the interaction of these two partners in solution before the immobilization step. Tcf4 was titrated into a solution of armadillo β-catenin at 25°C (Supplemental Fig. S1A). The reaction is exothermic, and the last injections correspond to the dilution heat effects only (Supplemental Fig. S1A, inset). The binding of Tcf4 to armadillo β-catenin is characterized by a K D of 41 nM, ΔH = −18.8 kcal/mol and complex stoichiometry of 1:1, which reflects the similarity between the X-ray structures and the solution complex structure. The binding constant shows a good agreement with the published values (Knapp et al. 2001; Choi et al. 2006).

The integrity of binding activity of the armadillo β-catenin upon immobilization on the surface was checked by ELISA binding assays (Hinterdorfer et al. 1998; Lepourcelet et al. 2004). Purified armadillo β-catenin was either nonspecifically coated on microtiter plates or specifically attached on mica surfaces via a short EGS-NTA linker (see below) and sequentially incubated with GST–Tcf4, anti-GST antibody, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (▶). The absorbance was two times higher in the wells or mica sheets incubated with armadillo β-catenin and Tcf4 than in the control ones (data not shown). The test showed the immobilization on polysterene or NTA-functionalized mica does not interfere with the ability of armadillo β-catenin to recognize and bind specifically to Tcf4.

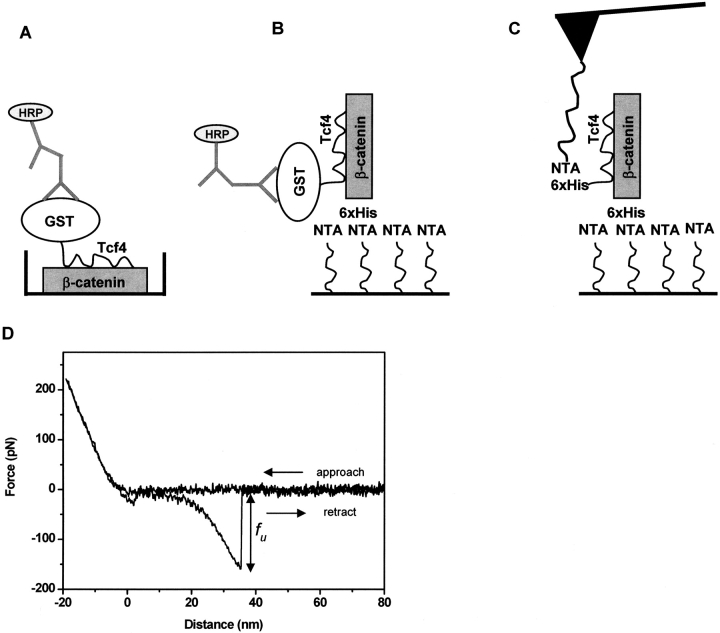

Figure 1.

Tcf4/armadillo β-catenin recognition. Purified armadillo β-catenin (residues 134–671) was allowed to interact either with GST-Tcf4 (residues 1–57) (A,B) or His-Tcf4 (C,D). The interaction in A and B was detected with goat anti-GST antibody, HRP-anti-goat IgG, and HRP substrate. (A) Purified armadillo β-catenin was adsorbed to ELISA plates. (B) Purified armadillo β-catenin was specifically attached to a mica substrate via flexible linkers. (C) In the AFM molecular recognition setup, His–Tcf4 was specifically attached to the cantilever tip via PEG linkers and brought into contact with armadillo β-catenin attached to the mica substrate via EGS linkers. (D) Raw data from a representative force–distance cycle measured at 0.5 Hz for armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 interaction. The functionalized tip was approached to the functionalized surface and then retracted while the deflection of the cantilever was monitored. The attractive force signal in the retrace curve reflects the unbinding event, its magnitude corresponding to the unbinding force, fu.

Armadillo β-catenin forms two complexes with Tcf4

We investigated the interaction between armadillo β-catenin and Tcf4 by single-molecule force spectroscopy attaching both partners noncovalently, via a polymer spacer, to a mica surface and an AFM tip, respectively (see Materials and Methods; ▶). This allows greater flexibility and better spatial orientation of surface-bound proteins. To minimize random errors such as variation in tip coverage and spring constant, the data was obtained using several functionalized tips. To achieve single-molecule recognition, both the ligand and the receptor were immobilized on tip and surface, respectively, at low concentration (Nevo et al. 2003, 2004). Typically, 8%–15% of the force distance curves showed unbinding events.

▶ shows a representative approach–retract cycle for the described experimental setup. To avoid disruption of the NTA–His6 bond (Kienberger et al. 2000a) and damage of the immobilized proteins, the contact loading force was limited to values between 50–300 pN. The unbinding force fu was measured from the maximum deflection signal prior to pulloff on the retraction curve; in the case of multiple-event retraces, only the last pulloff jump was considered.

As in ensemble experiments, the discrimination between specific and nonspecific interactions should be evaluated by control experiments. A careful study of the interactions at various stages during the tip and surface functionalization showed no interactions until both Tcf4 and armadillo β-catenin were present on the tip and mica substrate. We performed experiments where we measured the interaction between the NTA linker on the tip and NTA linker on the mica and between the fully functionalized tip and a sample surface, where just the last step, the coupling of armadillo β-catenin to the EGS linker, had not been carried out. Experiments with a noninteracting protein, such as lysozyme as a blocking agent, had no effect on the interaction. Applying free armadillo β-catenin to the solution to block the ligand on the tip decreased the number of unbinding events to 4%–6%.

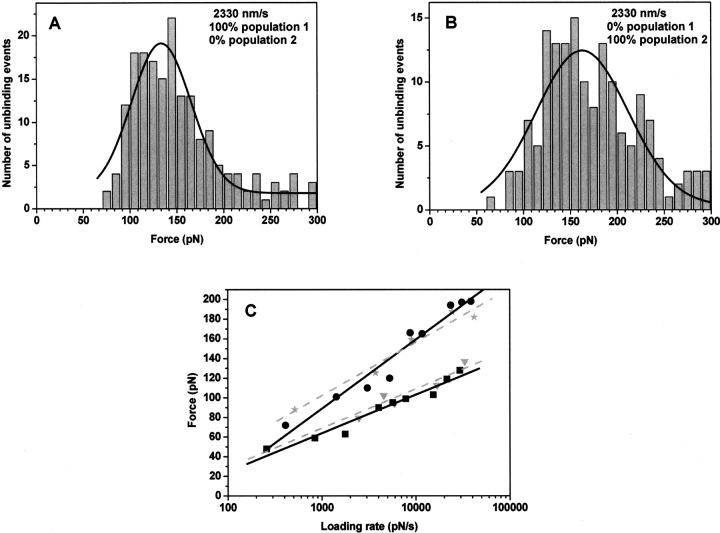

Experiments were performed at different pulling velocities varying between 40 and 2330 nm sec−1. Unbinding of Tcf4 from armadillo β-catenin gave rise to a set of force distributions presented in ▶. All these distributions, except the highest pulling rate (▶), show a bimodal behavior described previously by Nevo et al. (2003), corresponding to two distinct populations of molecular complexes independently leading to a force distribution. They shift to higher unbinding forces as the loading rates increase (see Equation 1 in Materials and Methods). A shift is also noticed in the relative size of the force distributions, the low-strength population occupancy increasing from 32% to 100% as the probe velocity increases from 40 to 2330 nm/sec. Further tests confirmed that the two populations are statistically independent, albeit the skewed appearance in the low force area (t-test P-value between 10−3 and 10−5).

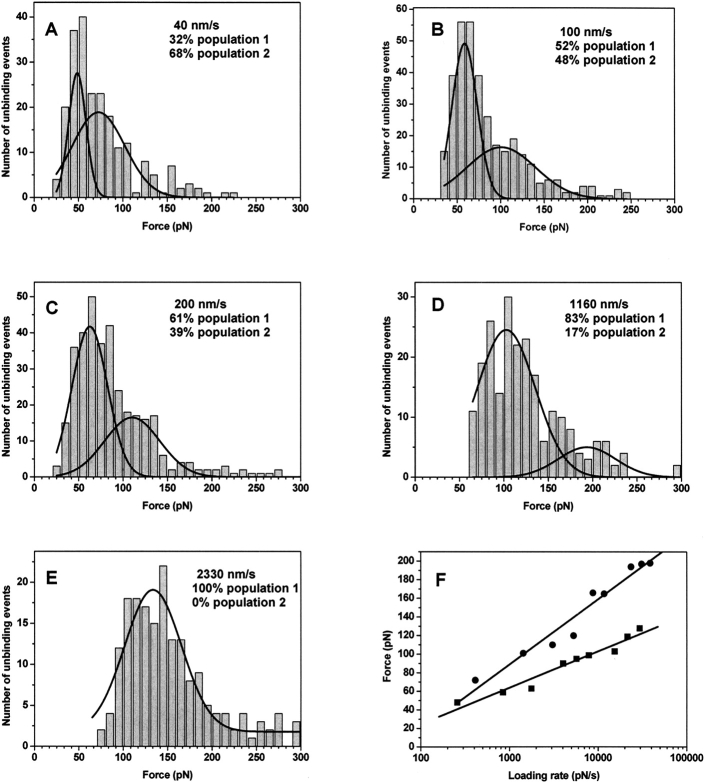

Figure 2.

Distributions of unbinding forces (A–E) and force spectra (F) for armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes. Histograms from 200–400 approach/retract cycles of the complex are presented at various probe velocities: (A) 40 nm/sec, (B) 100 nm/sec, (C) 200 nm/sec, (D) 1160 nm/sec, and (E) 2330 nm/sec. The maximum of each distribution was found by the Gaussian fit of the histograms. Two maxima are evident for most of the distributions, corresponding to the presence of two populations of molecules. Increasing the probe velocity and the loading rate results in the shift in the peak distributions to higher forces and the increase of the fractional occupancy of the low-strength population. (F) Most probable unbinding forces were plotted against the logarithm of the loading rate. Two plots are presented corresponding to the two populations of bound armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes.

The force spectra of the armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 interaction (▶) reveal two well-separated linear regimes corresponding to energy barriers of distinct conformations. These unconventional force spectra containing two independent curves have been observed experimentally before for the interaction between importin β1, similar in structure with armadillo β-catenin, and its ligand Ran (Nevo et al. 2003, 2004). The rupture force of the complexes increases gradually over three orders of magnitude in loading rate. The linear fit of the semilog force spectra yields the length dimension of the energy barrier along the dissociation path, x β. One complex is separated from the maximum barrier by x β of 0.55 nm and the second one by 0.31 nm. Only one barrier was detected for each complex within the range of loading rates used.

Armadillo β-catenin populates different conformations

The armadillo repeat domain of β-catenin consists of 550 amino acids and contains 12 armadillo repeats (R1–R12 in ▶), each repeat being made up of three helices: H1, H2, and H3. These armadillo repeats pack together to form a superhelix of helices, creating a positively charged groove that functions as a multiple ligand-binding domain for proteins such as Tcf/Lef, APC, axin, and E-cadherin. To characterize the structural differences between the apo form of armadillo β-catenin and its complex form with different ligands, we have performed a comparative analysis using 12 complex structures (▶; Supplemental Fig. S2).

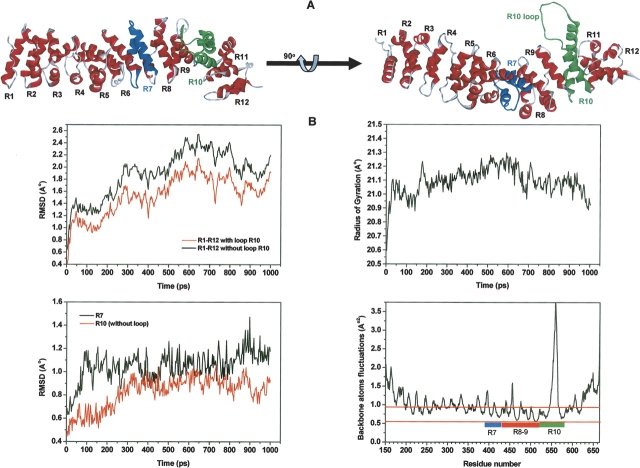

Figure 3.

Global analysis of MD trajectory of apo-armadillo β-catenin. (A) Ribbon representation of the minimized apo structure with the long loop of R10 (green) modeled. (B) Backbone RMSD of all repeats with and without the R10 loop (top left), the radius of gyration of all repeats (top right), backbone RMSD of R7 and R10 without the loop (bottom left), and backbone atom fluctuations of all repeats (bottom right).

Table 1.

Structural analysis and alignments of apo-armadillo β-catenin and complexes of armadillo β-catenin with different ligands

Structural alignments show root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) between 1.5 and 2.2 Å, which suggest that small differences between the backbone forms exist. However, the calculated radii of gyration show almost no difference in the shape of the protein between the apo and complex forms. In addition, a similar trend is found by counting the number of hydrogen bonds between backbone to backbone and side chain to backbone, in the context of experimental conditions and structure determination protocols. However, the number of unseen residues in the long loop in repeat 10 (R10 in ▶) decreased in the complex forms, except for the structures 1luj, 1i7w, and 1jpp. This suggests that the loop mobility decreases upon binding.

It has been reported that the lack of H1, the first helix of the usual armadillo repeat in the repeat 7 (R7 in ▶) might result in the increase of its dynamics (Huber et al. 1997). As our findings stress the decrease of unseen residues at the R10 loop upon binding, then the dynamics of R10 may be also affected. Thus, further comparative analysis was performed at, and adjacent to, R7 and R10 (Supplemental Fig. S2). While the angle between H2 and H3 helices of R7 increased between 5° to 10°, the same angle in R10 showed a mixture of increase and decrease with values lower than 5°. The torsion angle (χ) of R7 increased substantially between 5° to 15° (the mean value is about 10°), whereas globally χ−1 and χ+1 decreased with values <3.5°. However, for R10 the values of χ and χ+1 show a very small increase, <2°, and the χ−1 values show a mixture of small increase and decrease of <3°. Consequently, our comparison reveals that, upon binding, R7 is highly affected with a consistent trend of changes in these complexes, while R10 is less affected. Note that all the torsion angles of R7 and R10 increased in complexes, compared to the apo form.

The evidence of distinct β-catenin conformations in the cell (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004a), together with our force spectroscopy results showing the existence of two populations of armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes (▶) and our findings from the structural analysis (▶; Supplemental Fig. S2), indicated that the dynamic behavior of the apo form of armadillo β-catenin should be further studied using MD simulation.

Table 2.

Structural analysis and alignments of apo-armadillo β-catenina with its second crystal form and MD structures

Analysis of the MD trajectory shows that the overall shape of armadillo β-catenin remained unchanged and the backbone structural variations were minimal for such a large system if the long loop of R10 is excluded, as judged by the radius of gyration and RMSDs along the MD trajectory (▶). Indeed, the highly dynamic nature of the R10 loop is well captured in most of the reported X-ray structures (Huber et al. 1997; Eklof Spink et al. 2001; Huber and Weis 2001; Graham et al. 2002); however, in different complexes several residues may be less dynamic as seen in the electron density (▶). Indeed, backbone atom fluctuations of the loop show high flexibility at this region (▶). Complex structures of armadillo β-catenin with several ligands show the repeats R7 to R10 are directly involved in the binding, which suggests that R8 and R9 may undergo some structural rearrangement. Interestingly, our comparative analysis of the apo-armadillo β-catenin with other complexes reveals no substantial changes at R8 and R9 (data not shown). Furthermore, analysis of backbone atom fluctuations during our MD trajectory shows a substantial rigidity at R8 and R9 in comparison with the other repeats (▶). In addition, comparison of the backbone RMSDs between R7 and R10 without its loop shows that R7 has higher RMSD than R10, confirming earlier reports of the possible intradynamics of R7 due to the lack of helix H1 (Huber et al. 1997). Taking into account the potential dynamics of R7 discussed above, the involvement of R10 due to its long loop, and the substantial rigidity of R8–9, we focused our MD trajectory analysis within and around repeats R7 and R10.

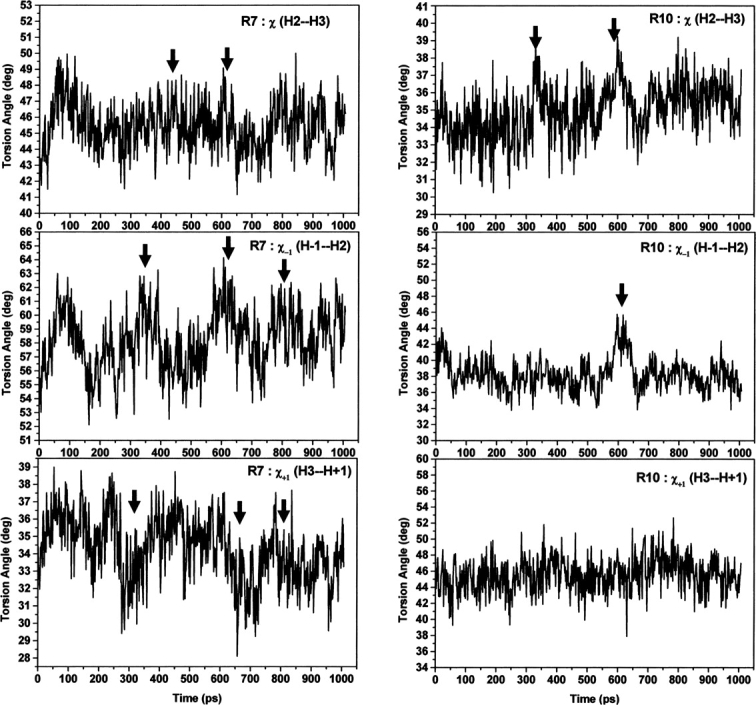

The angle between helices H2 and H3 as well as the angles with H−1 and H+1 (see Materials and Methods) vary slightly during the simulation, but no major events were noticed (Supplemental Fig. S3). The torsion angles exhibit slightly higher variations than the angles between helices H2 and H3, with a couple of events of about 50–100 ps duration occurring (▶; see arrows). It is worth noting that R10 has slightly higher variations than R7, which should be more dynamic, as has been reported (Huber et al. 1997) and revealed by our structural analysis. However, the torsion angles with helices H−1 and H+1 show that R7 has higher variations and several events (see arrows in ▶) have been seen with longer life times (>100 psec), while R10 exhibits no substantial variations and almost no events except with H−1 helix. These results may suggest that while the dynamic behavior of R7 is nearly similar to R10, the dynamics of the whole of R7 are substantially higher than that of R10 as revealed by the additional analysis of helices H+1 and H−1. Indeed, close inspection of the analysis using H−1 and H+1 shows the complementary behavior of the torsion angles; when changes increased using H−1, there is a decrease with H+1 (▶). This strongly suggests that R7 has substantial flexibility as a whole repeat when compared to R10.

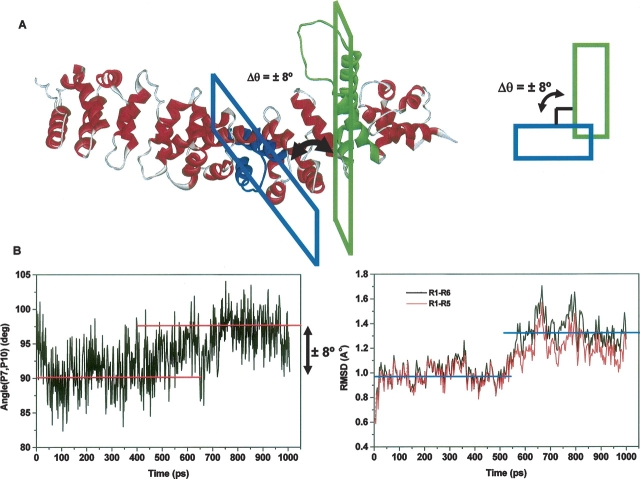

Figure 4.

Angle analysis within and adjacent to R7 and R10 of apo-armadillo β-catenin during the MD trajectory. From top to bottom and for either R7 (left) or R10 (right): time-dependent torsion angle between H2 and H3 helices, torsion angle between helices H−1 and H2, and torsion angle between helices H3 and H+1. The events are marked by arrows.

To further investigate the dynamics of the common binding site for several ligands of armadillo β-catenin (R7 to R10) and explore the possibility of movement coupling between R7 and R10, we have measured the angle changes between the planes formed by H2 and H3 in the repeats R7 and R10, called planes P7 and P10, respectively (see Materials and Methods). Indeed, close inspection of armadillo β-catenin structure revealed that these repeats sit in the molecule almost perpendicular to one another (Supplemental Fig. S4). Analysis of the angle changes between P7 and P10 during the MD trajectory revealed the existence of two populations of conformers with a long lifetime (∼300 psec) and separated by an angle change of ∼8° (▶); note that the second population appears in the MD trajectory around 600 psec. Furthermore, the backbone RMSD of either R1 to R5 (R1–R5) or R1 to R6 (R1–R6), which are away from R7 to R12, shows a sudden increase creating two separate plateaus, which occur at about the same time in the MD trajectory as the rotation between P7 and P10 takes place (∼600 psec; ▶).

Figure 5.

Existence of two molecular populations of apo-armadillo β-catenin. (A) Ribbon diagram of apo-armadillo β-catenin highlighting the perpendicular arrangement between planes formed by H2 and H3 helices within R7 and R10 (P7 and P10), which may change by 8°, resulting in two molecular populations. (B) Time-dependent angle change between P7 and P10 planes (left) and time-dependent RMSD of either repeats 1–6 or repeats 1–5 (right).

ICAT reduces the occupancy of the low-strength population

ICAT is a 9-kDa polypeptide that inhibits both Tcf4 and cadherin binding to β-catenin in vitro, but selectively inhibits formation of Tcf4/β-catenin in vivo (Graham et al. 2002). Recent in vivo studies suggest a broader role for ICAT, highlighting its primary role in β-catenin signaling inhibition and suggesting that it may inhibit β-catenin binding to cadherin under certain conditions (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004b). This raises the question as to whether this is related to β-catenin/cadherin binding affinities, which in turn, might depend on the phosphorylation state of these partners (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004b). Our in vitro experimental results show that armadillo β-catenin could indeed have different affinities for its other ligand, Tcf4. Furthermore, our computational results suggest that the core region of β-catenin could adopt different molecular conformations, possibly responsible for variations in ligand affinities. Consequently, we investigated the inhibitory effects of ICAT on the detected populations of armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes, hypothesizing that it would either show some selectivity toward one of these conformations or would inhibit them both.

In the same buffer conditions, the affinity of armadillo β-catenin for ICAT is 40 times higher than for Tcf4 (Supplemental Fig. S1B). The binding of ICAT to armadillo β-catenin is characterized by a K D of 1.2 nM, a ΔH of –15.4 kcal/mol (Choi et al. 2006), and complex stoichiometry of 1:1 as obtained from the fit, in line with the X-ray structure of armadillo β-catenin/ICAT complexes (Daniels and Weis 2002; Graham et al. 2002).

The force measurement experimental setup was identical to that described above. Experiments were again performed at different pulling velocities varying between 40 and 2330 nm sec−1 using several functionalized tips in the presence of saturating amounts of inhibitor (30 μM).

The force distributions showed a bimodal behavior and the force spectra showed two linear regimes corresponding to the same populations of armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes (▶). Even though ICAT did not completely disrupt the formation of receptor–ligand complexes or selectively disrupt the formation of one conformation of receptor–ligand complexes, the fractional occupancy of the low-strength population was reduced by 30%–40% at low loading rates (data not shown), and was zero at very high pulling speeds (2330 nm sec−1; ▶), where only one population is present. ▶ shows that ICAT completely removes population 1 (0%); instead, the high-strength population 2 is favored (100%).

Figure 6.

Statistical distribution and force spectra of unbinding forces for the armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 interaction in the presence of ICAT. Histograms from 200–300 approach/retract cycles of the complex at 2330 nm/sec are presented. One maximum is evident for these distributions, corresponding to the presence of one population of molecules. In the absence of ICAT (A) the low-strength complex is populated but in the presence of ICAT (B) the high-strength population 2 is favored. (C) Four force spectra plots are presented corresponding to the two populations of bound armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes in the presence (▾,★, dashed lines) or absence of ICAT (▪, •, solid lines).

Discussion

Colorectal cancer is the third most common form of cancer, second only to lung and breast cancer among women, and lung and prostate cancer in men. Mutations in components of the Wnt signaling pathway (Polakis 2000), especially the APC complex and sometimes β-catenin itself, seem to be responsible for the formation of the vast majority of these cancers. Among the known components of this signaling pathway, the Tcf4/β-catenin complex is one of the most attractive targets for drug development purposes, because most of the mutations are found in APC, the key regulator of the cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin. As a consequence, only those elements downstream of APC in the pathway are rational targets for cancer therapy. However, targeting β-catenin presents a huge challenge for chemical biology due to the high level of complexity in its interaction with transcriptional factors, E-cadherin, and APC. As all have partially overlapping binding sites, drug-target selectivity might be difficult to achieve.

Recently, studies have identified small molecule compounds through natural product screening (Lepourcelet et al. 2004) that inhibit the Tcf4/β-catenin complex, but they also inhibit APC binding. A systematic and comprehensive study of β-catenin multiple interactions using peptide array methods identified specific and overlapping “hot spots” for different ligand interactions (Gail et al. 2005) that could be of great help in drug design. However, none of these studies have provided insights into the mechanism by which selectivity of this multifunctional protein is generated.

Our single-molecule studies of the Tcf4/β-catenin molecular complex, MD simulations of the dynamics of armadillo core region, and the inhibitory effects of ICAT may provide a better understanding of the molecular plasticity of this multifunctional protein, and hence, an explanation of how β-catenin may achieve its specificity. A deeper knowledge of the mechanism by which cells could separate adhesion and signaling functions would thus be of great help in the design of specific inhibitors of a particular molecular function.

Force measurements of intermolecular receptor–ligand binding strengths, where one partner is attached to AFM tips and the other partner to probe surfaces, provide insights into the molecular dynamics of the receptor–ligand recognition process (Nevo et al. 2003). By varying the loading rate of the force applied, the energy landscape of receptor–ligand bonds can be investigated (Merkel et al. 1999). In our study, by varying the loading rate over three orders of magnitude, we found two well-separated monologarithmical dependencies on the loading rate, indicating the existence of two distinct molecular complexes between armadillo β-catenin and Tcf4 (Nevo et al. 2003). The intercept of the force spectra with the y-axis suggests that the lifetimes of these molecular complexes are different, but of the same order of magnitude (▶). Thus, the two bound states easily interconvert and it appears that the low-strength bound state becomes progressively more populated as the loading rate increases.

The binding probability of the two partners under investigation varied between 8% and 15%. After adding 7 μM free β-catenin as a blocking agent, the number of curves displaying rupture events decreased to 4%–6%. The significant decrease in binding probability indicates the Tcf4 on the tip was blocked due to the binding of free β-catenin. Although the observed residual unbinding activity seems large in comparison to the binding probability, it is important to note that the persistence of residual unbinding activity of a similar magnitude is observed in almost all blocking experiments, even with the most efficient ones (Hinterdorfer et al. 1996; Wielert-Badt et al. 2002). Furthermore, the relatively inefficient blocking observed in our studies may also be ascribed to the presence of multiple armadillo β-catenin or/and Tcf4 conformers, which may silence some of the interactions while conserving other interactions.

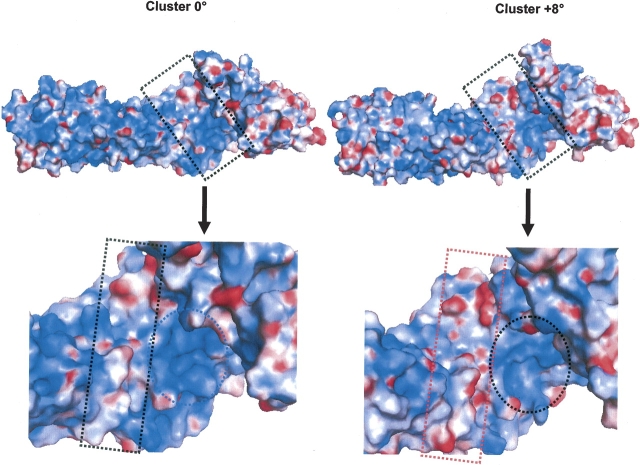

The structural differences between these two armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes are presently unknown. However, MD simulation revealed the existence of at least two conformers of the apo protein with 8° rotation shift between the planes formed by R7 and R10. Interestingly, Huber et al. (1997) have reported similar angle rotation (11.5°) between the structures of apo-armadillo β-catenin in their two crystal forms. Structural analysis comparison between crystal form A (PDB code 3bct) of the apo-armadillo β-catenin and crystal form B (2bct) used in this work revealed a striking result: RMSD plus the angle and torsion changes of the R7 and R10 are closely similar to those of armadillo β-catenin in complex with various ligands (▶). Furthermore, there are 12 unseen residues at the R10 loop compared to 13 for the structure 2bct, and the RMSDs of crystal form A with all the complexes are substantially low (▶). These similarities to the experimental complex forms strongly suggest that crystal form A of the apo-armadillo β-catenin has a preformed complex conformation. Indeed, several experimental and computational works have reported the existence of protein conformations in their free forms that resemble the complex form, as well as the low energy cost that may exist between these conformers (James et al. 2003; Wolf-Watz et al. 2004; Changeux and Edelstein 2005; Ma 2005; Tobi and Bahar 2005). To our knowledge, this is the first report about crystal form A adopting a preformed complex conformation of apo-armadillo β-catenin. Consequently, our MD simulation possibly reveals similar conformer populations. Indeed, if such conformers are populated enough, and hence observed experimentally, then MD simulation will reveal such behavior providing the driving forces behind the interconversion between these populations take place during the simulation time period as herein. Although these driving forces are unknown yet, our results suggest that the interconversion energy barrier is low enough to give rise to these populations, because our MD simulation is restraint free and not a targeted MD simulation (Schlitter et al. 1993). We speculate that, in combination with the dynamic nature of R7, the long loop of R10 may play a role in such interconversion process as a balancing weight between these conformers. However, there are two questions to address. First, is the second conformer population, with 8° rotation, similar to a preformed complex conformation? Second, how can a small rotation of 8° result in different binding affinity of armadillo β-catenin to its ligands? The answer to the first question is summarized in ▶. The cluster-0 conformer is closely similar to the apo form, as expected, but the cluster-8 has the hallmark of a preformed complex, as revealed by the RMSD and changes at R10 and R7. The answer to the second question is interestingly lying in the electrostatic potential surface (EPS) changes between cluster-0 and -8. Close inspection of the EPS at the major groove of armadillo β-catenin clearly reveals striking differences (▶). Rotation of 8° results in significant changes in cluster-8 EPS compared to cluster-0. While cluster-0 shows a highly positive EPS patch (the ellipsoid in ▶), an increase in negative EPS forming a channel is observed in cluster-8 (the rectangular form in ▶). Such changes in EPS will result in dramatic change in binding affinity and probably in specificity, since the electrostatic contribution is a major driving force in β-catenin binding to its ligands.

Table 3.

Structure alignments of both crystal forms of apo-armadillo β-catenin and its complexes

Figure 7.

Electrostatic potential surfaces of representative structures from MD simulation of apo-armadillo β-catenin. The electrostatic potential surfaces (EPS) of representative structure from MD simulation at 0° rotation (Cluster-0) and at 8° rotation (Cluster-8) were colored blue for positive and red for negative EPS, respectively. Upper figure represents the EPS of the whole structure and lower figure the zoom on the major groove of armadillo β-catenin.

Recently, conformational diversity of β-catenin has been detected experimentally in vivo (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004a). Distinct molecular forms of β-catenin can be targeted selectively to E-cadherin or transcriptional factors, a mechanism by which the cell could potentially separate the adhesion and signaling functions of this protein. But how are these forms of β-catenin generated? It has been suggested that either the APC–axin–GSK3β-containing complex, which normally is involved in targeting β-catenin for degradation, induces them by post-translational modifications or that the cell is able to generate these forms and controls their relative proportion according to the biological needs of the cell in a Wnt signaling-dependent manner (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004a).

Our in vitro results, in the absence of any potential post-translational modifications, strongly suggest that these various forms preexist in the cell, generated by the dynamics of this molecular system. Although the structures of the apo and complex forms of armadillo region of β-catenin may appear similar, suggesting that this region does not adopt different conformations to accommodate different ligands, our comparative structural analysis revealed clear differences. Even if helical repeat proteins like the armadillo region provide a relatively rigid structural platform, our MD simulations show that subtle conformational variations in the flexible regions could generate the differential binding selectivity of β-catenin. Preexisting β-catenin pools with different binding affinities for ligands could thus help this multifunctional protein manage its interaction with many partners at the same binding site and exert different functions. This is in line with recent reports which favor the mechanism of preexisting equilibrium in which the ligand binds selectively to an active conformation among the existing ensemble of protein conformations (James and Tawfik 2003; Wolf-Watz et al. 2004; Tobi and Bahar 2005).

It is tempting to speculate that the “in vitro” populations of the armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complex correspond to the experimentally found “closed” and “open” full-length β-catenin conformations, which either bind transcriptional factors only or compete for both signaling or cadherin binding; these should have distinct affinities for Tcf4. Even though it has been proposed that the binding selectivity of the two forms is controlled by the C-terminal region of full-length β-catenin, which might fold over the last two armadillo repeats (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004a), recent thermodynamics studies have ruled out such a mechanism (Choi et al. 2006). We propose that small alterations into the armadillo core conformation could have significant consequences for binding instead.

The complexity of this molecular system is further increased by the conformational diversity observed in the Tcf family of armadillo β-catenin ligands (Graham et al. 2000, 2001; Poy et al. 2001). Consequently, the unstructured Tcf4 (Knapp et al. 2001) connected to the tip could also fold into distinct conformations upon interaction with armadillo β-catenin.

Interestingly, recent surface plasmon resonance studies of β-catenin binding to E-cadherin (Choi et al. 2006) suggested a heterogeneity of populations due to a possible equilibrium between two cis and trans isomers of a proline residue in E-cadherin. However, our findings suggest a β-catenin heterogeneity of populations as an alternative explanation.

Taking into account the complexity of this molecular system as suggested by our results and other groups, it is not surprising that ICAT did not have a dramatic inhibitory effect. Previous studies suggested that although ICAT's primary role is Tcf4 inhibition, it might inhibit cadherin binding to β-catenin in vivo under certain conditions, probably depending on β-catenin/cadherin binding affinities (Gottardi and Gumbiner 2004b). Our data suggests that ICAT is also able to modulate its interaction with Tcf4 in vitro, based on the same binding affinities, assumption. The occupancy of one population of armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes decreases in the presence of the inhibitor and under extreme force conditions completely disappears. We hypothesize that the absence of complete disruption of one or both populations of armadillo β-catenin/Tcf4 complexes is due either to the fact that this single-molecule method did not identify the molecular form(s) ready to be inhibited by ICAT or that a full inhibition process is difficult to achieve on a surface rather than in solution. Additional dynamic force spectroscopy investigations combined with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy would be needed to elucidate the mechanism of ICAT inhibitory process.

In conclusion, our study, using force spectroscopy and MD simulation, represents an important step in elucidation of the mechanism regulating the generation of different forms of β-catenin: It suggests that a preequilibrium exists between an ensemble of conformational isomers with similar folding but discrete energy levels and different affinities for ligands. Part of this has been revealed experimentally by the existence of two crystal forms representing the apo and a predefined complex form (Huber et al. 1997), as highlighted for the first time by our structural analysis. Thus, ligand binding will shift the equilibrium in favor of the high affinity isomer. Moreover, the various isomers will probably interconvert in response to cellular needs, ligand availability, or intracellular localization. Taking into account our MD simulation results, only modest conformational changes could be responsible for interconversions between isomers with a low energy barrier. Such a conformational diversity could explain the functional promiscuity of β-catenin and, more specifically, could provide an insight into the relationship of its two functions. Our data also suggests new avenues for the design of inhibitory drugs for medical use, taking into account the plasticity of this dynamic molecular system and the complex model of inhibition by the physiological inhibitor ICAT. Drug design strategies could also benefit from MD simulation to provide representative protein decoys from each population to be used in drug design.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of proteins

The armadillo repeat region of β-catenin (amino acid residues 134–671) was 6xHis tagged at the C terminus and subcloned into a pGEM 4Z vector (Promega) before cloning as a BamHI/NotI fragment into the pGEX-6P2 vector (Amersham Biosciences).

The binding site of Tcf4 (residues 1–57) containing a tryptophane residue at the C terminus (Fasolini et al. 2003) was 6xHis tagged at the N terminus and cloned as the NdeI/EcoRI fragment into the pET 21a vector (Novagen). The same protein fragment was cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites of the pGEX 2T vector (Amersham Biosciences) in frame with the GST–thrombin fusion domain for ELISA detection.

The Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with pGEX-6P2 armadillo β-catenin 6xHis, pET21–Tcf4, pGEX–2T–Tcf4, or pGEX–4T3–ICAT, and the expressed proteins purified as detailed in the Supplemental material.

Isothermal titration calorimetry and ELISA

A protocol similar to the one described in Lepourcelet et al. (2004) was followed to detect the interaction between GST–Tcf4 and armadillo β-catenin by ELISA. Details on the ITC and ELISA procedures are available in the Supplemental material.

Tip and substrate functionalization

A heterobifunctional polyethylene glycol (PDP–PEG–NHS) derivative of 18 units with an amine- and a thiol-reactive end (Haselgrubler et al. 1995) (a gift from Christian Riener, University of Linz, Austria) was used to covalently attach the thiol-reactive end to Microlever silicon nitride tips (Veeco) as described (Nevo et al. 2003) and the amine-reactive end to N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid to create a terminal nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) group. PDP–PEG–NHS was allowed to react for 3 h with 10 times molar excess of N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA before adding the AFM tips fictionalized with ethanolamine-HCl and N-succinimidyl-3-(acetylthio)propionate as described previously (Nevo et al. 2003). The PEG-modified tips were rinsed with 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM NiCl2, immersed for 10 min in this buffer, and incubated in 2 μM His–Tcf4 diluted in the same buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature.

Armadillo β-catenin was immobilized onto the mica discs (Agar Scientific) via a 2-nm long ethylene glycolbis (succinimidylsuccinate) linker (Pierce) using a 100 μg/mL armadillo β-catenin in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole. The mica was washed with the same buffer to remove unbound protein, and the experiments were performed in the same buffer.

Force measurements

Measurements were carried out in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole using a Multimode equipped with a Picoforce module (Veeco). Spring constants of the cantilevers varied between 0.015 and 0.04 N m−1 as determined by the thermal noise method. Unbinding forces between tip-bound Tcf4 and mica-bound armadillo β-catenin were monitored by force–distance cycles at 100 nm amplitude and at frequencies ranging from 0.2 to 12 Hz. The approach and retraction speeds were identical, varying between 40 and 2300 nm sec−1. Cantilever deflection versus distance curves were analyzed using the commercially available SPIP software (Image Metrology). The cantilever deflection measurements are converted to force values using the deflection sensitivity of the cantilever on a mica surface in liquid and the cantilever spring constant, and hence the unbinding forces were estimated. An average of 300 rupture events were recorded at each speed and then cumulated into histograms, using a bin width of 10 pN corresponding to the estimated thermal noise of the cantilever. The Gaussian fits of the histograms were carried out using Origin. The fit with two Gaussian functions showed r 2 values typically >0.9. An additional t-test showed the two Gaussians are statistically independent with P-value between 10−3 and 10−5. The most probable force for unbinding, f*, taken as the maximum of these force distributions, was plotted against the logarithm of the loading rate, rf, according to the equation:

|

where x β describes the location of the energy barriers relative to the bound state, k off is the dissociation rate of the molecular complex, kB the Boltzman constant, and T the absolute temperature (Evans and Ritchie 1997).

The loading rates were corrected for linker compliance using an effective spring constant 1/k eff = 1/k cantilever + 1/k PEG (Riener et al. 2003). The spring constant of the PEG molecule, k PEG, was calculated from the derivative of the Marko-Siggia worm-like chain model (Kienberger et al. 2000b) using the persistence length and the contour length from the fit of all force distance curves with this model.

Molecular dynamics simulations and structural analysis

The apo structure of β-catenin used in the simulation was taken from PDB entry 2btc (Huber et al. 1997). The missing residues at the long loop in repeat 10, R550 to G563, were added, and full structure minimization was performed, using the Amber program (Case et al. 2004). The MD simulation of the fully immersed apo-β-catenin in a rectangular box, 110.1 Å × 118.3 Å × 82.2 Å, filled with TIP3P water was performed using the Amber program. The simulated system consists of 516 residues, 5 Cl− ions, and 27,267 water molecules, making a total of 89,822 atoms. The time step was 1.5 fsec, with all bonds fixed to their equilibrium values by SHAKE; the formal charge of the protein of +5e was neutralized by adding Cl− ions, the temperature was 300 K, van der Waals interactions were truncated at 10.0 Å, while electrostatic interactions were fully calculated with the Particle Mesh Ewald method. After performing energy minimization only on the water molecules, 50 psec of solvent equilibration at 300°K were calculated after including the Cl− ions. Following equilibration, a trajectory of 1 nsec was calculated. The electrostatic potential was calculated using the Divcon program with a PM3 Hamiltonian (Gogonea and Merz 1999), and the EP mapped at the surface of the proteins using the PyMOL program (DeLano 2002).

Comparison of the apo structure of β-catenin with 12 of its complex structures (with Tcf4, xTcf3, E-cad, phosphorylated E-cad, ICAT, APC, and Axin) was performed using the PDB entries: 1jdh, 1jpw, 1m1e, 1luj, 1g3j, 1i7x, 1i7w, 1jpp, 1q7z, 1t08, 1th1, and 1v18. The structural alignments between the apo structure and the complex form of β-catenin were performed using the CE program (Shindyalov and Bourne 1998). The torsion angles (χ) between helix H2 and H3 of repeat 7 and repeat 10, as well as the torsion angles (χ−1 and χ+1), with the preceding and subsequent helices of their adjacent repeats called “H−1” and “H+1” helices were defined by the following residues either using their Cα and/or center of mass; Repeat 7: (H2–H3) L401–G410–N415–C429, (H−1–H2) R376–D390–L401–G410, (H3−H+1) N415–C429–I444–A454; Repeat 10: (H2–H3) P534–T547–E568–A581, (H−1–H2) P505–L517–P534–T547, (H3–H+1) E568–A581–P597–Y604. The planes formed by helices H2 and H3 in R7 and R10, P7 and P10, respectively, were defined by the following residues, using either their Cα and/or center of mass; R7: L405–N415–Y432; R10: L527–T547–I569.

Electronic supplemental material

Details of the cloning and isothermal titration calorimetry procedures (Supplemental materials and methods) and four figures showing the isothermal titration calorimetry curves and additional information on the MD simulation are published online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Riener for providing the PDP–PEG–NHS linker and for helpful advice on tip and substrate functionalization, Stefan Knapp for providing the cDNA for armadillo β-catenin and Tcf4, Cara Gottardi for the cDNA of human ICAT, and John Ladbury for providing access to the ITC equipment. We also thank Adrian Vonsovici for mathematical support in data analysis, Reinat Nevo, Christian Rankl, and Peter Hinterdorfer for helpful discussions, and Marshall Stoneham, FRS, for critical reading of the manuscript. A.A. wishes to thank K. Merz for allowing us to use his Amber and Divcon programs. This work was supported by the Interdisciplinary Research Collaboration (IRC) in Nanotechnology, UK.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Michael Horton, London Centre for Nanotechnology and Department of Medicine, University College London, 5 University Street, London WC1E 6JJ, UK; e-mail: m.horton@ucl.ac.uk; fax: 44-020-7679-6219.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.072773007.

References

- Behrens J. and Lustig, B. 2004. The Wnt connection to tumorigenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J., von Kries, J.P., Kuhl, M., Bruhn, L., Wedlich, D., Grosschedl, R., and Birchmeier, W. 1996. Functional interaction of β-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 382 638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case D.L., Darden, T.A., Cheatham, T.E., Simmerling, C.L., Wang, J., Duke, R.E., Luo, R., Merz, K.M., Wang, B., Pearlman, D.A., et al. 2004. AMBER 8. University of California, San Francisco, CA.

- Changeux J.P. and Edelstein, S.J. 2005. Allosteric mechanisms of signal transduction. Science 308 1424–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.J., Huber, A.H., and Weis, W.I. 2006. Thermodynamics of β-catenin–ligand interactions: The roles of the N- and C-terminal tails in modulating binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 281 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D.L. and Weis, W.I. 2002. ICAT inhibits β-catenin binding to Tcf/Lef-family transcription factors and the general coactivator p300 using independent structural modules. Mol. Cell 10 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA.

- Eklof Spink K., Fridman, S.G., and Weis, W.I. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of β-catenin recognition by adenomatous polyposis coli revealed by the structure of an APC–β-catenin complex. EMBO J. 20 6203–6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E. and Ritchie, K. 1997. Strength of a weak bond connecting flexible polymer chains. Biophys. J. 76 2439–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasolini M., Wu, X., Flocco, M., Trosset, J.Y., Oppermann, U., and Knapp, S. 2003. Hot spots in Tcf4 for the interaction with β-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 278 21092–21098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail R., Frank, R., and Wittinghofer, A. 2005. Systematic peptide array-based delineation of the differential β-catenin interaction with Tcf4, E-cadherin, and adenomatous polyposis coli. J. Biol. Chem. 280 7107–7117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles R.H., van Es, J.H., and Clevers, H. 2003. Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1653 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogonea V. and Merz, K.M.J. 1999. Fully quantum mechanical description of proteins in solution. Combining linear scaling quantum mechanical methodologies with the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Phys. Chem. A 103 5171–5188. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding J.M., Yap, K.L., and Ikura, M. 2004. The cadherin–catenin complex as a focal point of cell adhesion and signalling: New insights from three-dimensional structures. Bioessays 26 497–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi C.J. and Gumbiner, B.M. 2004a. Distinct molecular forms of β-catenin are targeted to adhesive or transcriptional complexes. J. Cell Biol. 167 339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi C.J. and Gumbiner, B.M. 2004b. Role for ICAT in β-catenin-dependent nuclear signaling and cadherin functions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286 C747–C756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham T.A., Weaver, C., Mao, F., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. 2000. Crystal structure of a β-catenin/Tcf complex. Cell 103 885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham T.A., Ferkey, D.M., Mao, F., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. 2001. Tcf4 can specifically recognize β-catenin using alternative conformations. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham T.A., Clements, W.K., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. 2002. The crystal structure of the β-catenin/ICAT complex reveals the inhibitory mechanism of ICAT. Mol. Cell 10 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha N.C., Tonozuka, T., Stamos, J.L., Choi, H.J., and Weis, W.I. 2004. Mechanism of phosphorylation-dependent binding of APC to β-catenin and its role in β-catenin degradation. Mol. Cell 15 511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrubler T., Amerstorfer, A., Schindler, H., and Gruber, H.J. 1995. Synthesis and applications of a new poly(ethylene glycol) derivative for the crosslinking of amines with thiols. Bioconjug. Chem. 6 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterdorfer P., Baumgartner, W., Gruber, H.J., Schilcher, K., and Schindler, H. 1996. Detection and localization of individual antibody–antigen recognition events by atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 3477–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterdorfer P., Schilcher, K., Baumgartner, W., Gruber, H., and Schindler, H. 1998. A mechanistic study of the dissociation of individual antibody–antigen pairs by atomic force microscopy. Nanobiology 4 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Huber A.H. and Weis, W.I. 2001. The structure of the β-catenin/E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by β-catenin. Cell 105 391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A.H., Nelson, W.J., and Weis, W.I. 1997. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of β-catenin. Cell 90 871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James L.C. and Tawfik, D.S. 2003. Conformational diversity and protein evolution—A 60-year-old hypothesis revisited. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James L.C., Roversi, P., and Tawfik, D.S. 2003. Antibody multispecificity mediated by conformational diversity. Science 299 1362–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienberger F., Kada, G., Gruber, H.J., Pastushenko, V.P., Riener, C., Trieb, M., Knauss, H.G., Schindler, H., and Hinterdorfer, P. 2000a. Recognition force spectroscopy studies of the NTA–His6 bond. Single Mol 1 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kienberger F., Pastushenko, V.P., Kada, G., Gruber, H., Riener, C., Schindler, H., and Hinterdorfer, P. 2000b. Static and dynamical properties of single poly(ethylene glycol) molecules investigated by force spectroscopy. Single Mol 1 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky M.W. 2005. β-catenin and its regulatory network. Hum. Pathol. 36 225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S., Zamai, M., Volpi, D., Nardese, V., Avanzi, N., Breton, J., Plyte, S., Flocco, M., Marconi, M., Isacchi, A., et al. 2001. Thermodynamics of the high-affinity interaction of TCF4 with β-catenin. J. Mol. Biol. 306 1179–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepourcelet M., Chen, Y.N., France, D.S., Wang, H., Crews, P., Petersen, F., Bruseo, C., Wood, A.W., and Shivdasani, R.A. 2004. Small-molecule antagonists of the oncogenic Tcf/β-catenin protein complex. Cancer Cell 5 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. 2005. Usefulness and limitations of normal mode analysis in modeling dynamics of biomolecular complexes. Structure 13 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel R., Nassoy, P., Leung, A., Ritchie, K., and Evans, E. 1999. Energy landscapes of receptor–ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature 397 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo R., Stroh, C., Kienberger, F., Kaftan, D., Brumfeld, V., Elbaum, M., Reich, Z., and Hinterdorfer, P. 2003. A molecular switch between alternative conformational states in the complex of Ran and importin β1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10 553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo R., Brumfeld, V., Elbaum, M., Hinterdorfer, P., and Reich, Z. 2004. Direct discrimination between models of protein activation by single-molecule force measurements. Biophys. J. 87 2630–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer C.A., Miller, P.J., Diehl, R.E., and Kral, A.M. 1999. Identification of Tcf4 residues involved in high-affinity β-catenin binding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256 584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M. and Polakis, P. 2000. Wnt signaling in oncogenesis and embryogenesis—A look outside the nucleus. Science 287 1606–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis P. 2000. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes & Dev. 14 1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poy F., Lepourcelet, M., Shivdasani, R.A., and Eck, M.J. 2001. Structure of a human Tcf4–β-catenin complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riener C., Stroh, C., Ebner, A., Klampfl, C., Gall, A.A., Romanin, C., Lyubchenko, Y.L., Hinterdorfer, P., and Gruber, H. 2003. Simple test system for single-molecule recognition force spectroscopy. Anal. Chim. Acta 479 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld B., Souza, B., Albert, I., Muller, O., Chamberlain, S.H., Masiarz, F.R., Munemitsu, S., and Polakis, P. 1993. Association of the APC gene product with β-catenin. Science 262 1731–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlitter J., Engels, M., Kruger, P., Jacoby, E., and Wollmer, A. 1993. Targeted molecular dynamics simulation of conformational change—Application to the T-R transition in insulin. Mol. Sim. 10 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Shindyalov I.N. and Bourne, P.E. 1998. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 11 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spink K.E., Polakis, P., and Weis, W.I. 2000. Structural basis of the Axin–adenomatous polyposis coli interaction. EMBO J. 19 2270–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tago K., Nakamura, T., Nishita, M., Hyodo, J., Nagai, S., Murata, Y., Adachi, S., Ohwada, S., Morishita, Y., Shibuya, H., et al. 2000. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by ICAT, a novel β-catenin-interacting protein. Genes & Dev. 14 1741–1749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobi D. and Bahar, I. 2005. Structural changes involved in protein binding correlate with intrinsic motions of proteins in the unbound state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102 18908–18913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutter A.V., Fryer, C.J., and Jones, K.A. 2001. Chromatin-specific regulation of LEF-1–β-catenin transcription activation and inhibition in vitro . Genes & Dev. 15 3342–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielert-Badt S., Hinterdorfer, P., Gruber, H.J., Lin, J.T., Badt, D., Wimmer, B., Schindler, H., and Kinne, R.K. 2002. Single-molecule recognition of protein binding epitopes in brush border membranes by force microscopy. Biophys. J. 82 2767–2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf-Watz M., Thai, V., Henzler-Wildman, K., Hadjipavlou, G., Eisenmesser, E.Z., and Kern, D. 2004. Linkage between dynamics and catalysis in a thermophilic–mesophilic enzyme pair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 945–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Clements, W.K., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. 2003. Crystal structure of a β-catenin/axin complex suggests a mechanism for the β-catenin destruction complex. Genes & Dev. 17 2753–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Clements, W.K., Le Trong, I., Hinds, T.R., Stenkamp, R., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. 2004. Crystal structure of a β-catenin/APC complex reveals a critical role for APC phosphorylation in APC function. Mol. Cell 15 523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]