Abstract

The thiol-based redox regulation of proteins plays a central role in cellular signaling. Here, we investigated the redox regulation at the Zn2+ binding site (HX5CX20CC) in the intracellular T1-T1 inter-subunit interface of a Kv4 channel. This site undergoes conformational changes coupled to voltage-dependent gating, which may be sensitive to oxidative stress. The main results show that internally applied nitric oxide (NO) inhibits channel activity profoundly. This inhibition is reversed by reduced glutathione and suppressed by intracellular Zn2+, and at least two Zn2+ site cysteines are required to observe the NO-induced inhibition (Cys-110 from one subunit and Cys-132 from the neighboring subunit). Biochemical evidence suggests strongly that NO induces a disulfide bridge between Cys-110 and Cys-132 in intact cells. Finally, further mutational studies suggest that intra-subunit Zn2+ coordination involving His-104, Cys-131, and Cys-132 protects against the formation of the inhibitory disulfide bond. We propose that the interfacial T1 Zn2+ site of Kv4 channels acts as a Zn2+-dependent redox switch that may regulate the activity of neuronal and cardiac A-type K+ currents under physiological and pathological conditions.

The highly conserved inter-subunit Zn2+ binding motif (HX5CX20CC) in the intracellular T1 domain differentiates voltage-gated K+ channels such as Kv2, Kv3, and Kv4 from the Shaker Kv1 channels (1, 2). Zn2+ is coordinated by a cysteine from one subunit and a histidine along with two cysteines from the neighboring subunit (Fig. 1). In the absence of β-subunits, Zn2+ binding to the T1 site in non-Shaker K+ channels is thought to stabilize the tetrameric structure of the channels (3, 4). However, co-expression of Kv4 channels with KChIP3 (Kv4-specific β-subunit) overrides the essential role of Zn2+ binding in subunit assembly (5, 6), whereas KChIP1 binds to the Kv4-T1 domain without altering the structure of the Zn2+ site and the T1-T1 interface (7, 8). Furthermore, mutant Kv4 channels lacking the Zn2+ site retain nearly normal gating when co-expressed with auxiliary subunits KChIP1 and DPPX-S (5), and our previous studies showed that the cysteines in the Kv4-T1 Zn2+ site are unexpectedly accessible to thiol-specific reagents and that the T1-T1 interface at this location is dynamic and functionally coupled to voltage-dependent gating (5, 9). Although it is clear that this interface is not the gate that opens the channel, rearrangements in and around the interfacial Zn2+ site may regulate the conformational changes required for the opening of the intracellular activation gate (9). This scenario is structurally plausible because just above the Zn2+ site, the T1 domain is linked to the voltage-sensing domain via the T1-S1 linker, and the C-terminal cytoplasmic region immediately distal to the S6-tail, which may serve as the actual activation gate, may also interact with the T1-T1 interface (10). The intriguing conservation of an apparently non-essential Zn2+ binding site at this gating regulatory domain suggests that it may play a signaling function rather than a purely structural role. In support of this hypothesis, reactive cysteines involved in Zn2+ binding in proteins are often identified as critical components in redox signaling (11-14). To test this hypothesis, we asked the following questions: 1) Is the T1 Zn2+ site a target of nitrosative and oxidative regulation? 2) Are the Zn2+ coordinating residues in the T1 domain responsible for the redox regulation? 3) What is the role of Zn2+? 4) What interactions are involved and what is the mechanism of the regulation? To answer these questions, we investigated the modulation of a heterologously expressed Kv4.1 channel by nitric oxide (NO) and intracellular Zn2+ and the underlying molecular mechanism. This modulation is significant, because many studies support the physiologically relevant relationship between NO and Zn2+ homeostasis in excitable tissues (12, 14-17). Particularly, various studies have reported redox modulation of Kv4-related A-type currents in neurons and muscles (15, 18-22). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms have remained unsolved. This study strongly suggests that the functionally active T1-T1 intersubunit interface of Kv4 channels is a Zn2+-dependent redox switch, which may play a central modulatory role in excitable tissues.

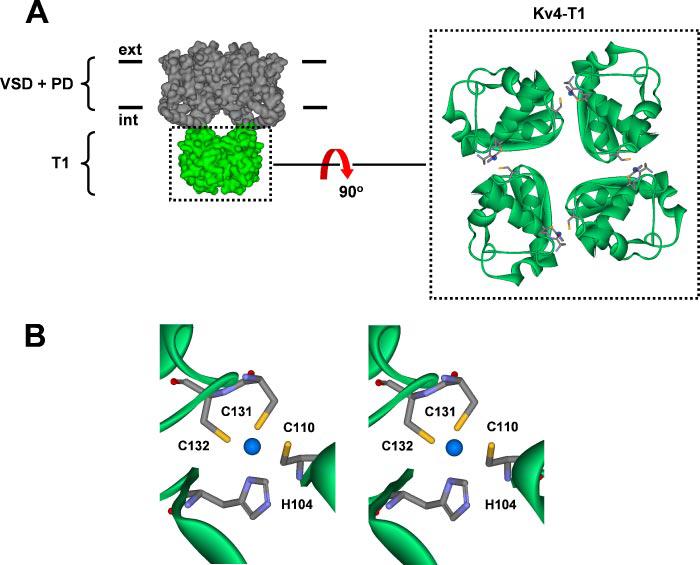

FIGURE 1. A structural model of the Kv4 channel.

A, left, side view of the Kv4 tetramer consisting transmembrane voltage-sensor domain (VSD) and pore domain (PD) and the intracellular T1 domain. For clarity, the auxiliary subunits KChIP1 and DPPX-S are not shown. Right, top view of the Kv4.2-T1 domain. Four blue spheres represent the location of Zn2+ atoms in the T1-T1 inter-subunit interfaces as found in the crystal structure of the isolated Kv4.2-T1 domain (2). B, stereo close-up of the Zn2+ binding site in the T1 domain. His-104, Cys-131, and Cys-132 are from the same subunit, and Cys-110 is from the neighboring subunit. A standard color scheme is used to represent the relevant atoms (sulfur atoms in yellow). The atomic distances between Zn2+ and His-104, Cys-110, Cys-131, and Cys-132 are 2.1, 2.4, 2.2, and 2.2 Å, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Reagents

H2O2 (30% w/v), dl-dithiothreitol (DTT), CuSO4, ZnCl2, 1,10-o-phenanthroline, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), and GSH were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. 1,10-o-Phenanthroline was solubilized in ethanol. (Z)-1-(N-Methyl-N-[6-(N-methylammoniohexyl)amino]) diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (MAHMA-NONOate) and sodium 2-(N,N-dimethylamino)diazenolate-2-oxide (DEA-NONOate) were purchased from Axxora Biosciences, San Diego, CA. Methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents (2-trimethylammonium ethyl methanethiosulfonate bromide (MTSET), 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate hydrobromide (MTSEA), and methylmethanethiolsulfonate (MMTS)) were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, Ontario, Canada) and stored in a desiccator at −20 °C. Tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl ethylenediamide) (TPEN) was purchased from Molecular Devices (Eugene, OR). As reported by the manufacturer, TPEN has an apparent binding affinity for Zn2+ of the order of 3 × 10−16 m. All working solutions of DTT, GSH, 1,10-o-phenanthroline, MAHMA-NONOate, SNAP, DEA-NONOate, and MTS reagents were made just before use.

Molecular Biology and Heterologous Expression

Kv4.1 (mouse) and DPPX-S were maintained in pBluescript II KS and pSG5 (Stratagene), respectively. KChIP1 was maintained in a modified pBluescript vector, pBJ/KSM. KChIP1 and DPPX-S are gifts from M. Bowlby (Wyeth-Ayerst Research, Princeton, NJ) and B. Rudy (New York University, New York, NY), respectively. All mutants were produced by using the QuikChange™ site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene and confirmed by automated sequencing (Nucleic Acid Facility of the Kimmel Cancer Institute, Thomas Jefferson University). The capped cRNAs for Xenopus oocyte expression were synthesized by using the in vitro transcription kit, Message Machine (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). For all the experiments, we co-expressed Kv4.1 WT and mutants with KChIP1 and DPPX-S. The expression of the Kv4.1 ternary complex was necessary because mutations in the putative Zn2+ site yielded non-functional channels or inhibited expression profoundly. Previous studies showed that the apparently lethal phenotype of Zn2+ site mutants can be corrected by co-expression of the channels with KChIPs (5, 6), and we have found that DPPX-S boosts the expression of the channels even further (5), which made possible the recordings from inside-out macropatches.

Electrophysiology

Inside-out patch clamp recordings were made using an asymmetrical KCl solution. Patch electrodes contained (mm) 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 Hepes (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH), and the bath solution consisted of (mm) 98 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES (pH 7.2, adjusted with KOH). The internal solution containing ZnCl2 had no EGTA. Passive leak and capacitive transients from macropatch currents were subtracted on-line by using a P/4 procedure. The currents were filtered at 1.5–5 kHz. All the experiments were carried out at room temperature (22±1 °C), and reagents were applied to the intracellular side of the patches. MAHMA-NONOate and DEA-NONOate were prepared just after forming the inside-out patch and establishing a stable current level. The powder was promptly solubilized in 10 mm NaOH at 100 mm. Several doses of stock solution were immediately stored below −70 °C. The final working solution at 0.1 mm was applied to the intracellular side of the channel. At room temperature, these two reagents generate 2NO with a half-life of ∼3 min and ∼15 min at pH 7.4, respectively (23). For disulfide cross-linking experiments, we used a mild oxidizing solution containing 50 μm CuSO4 and 200 μm 1,10-o-phenanthroline (Cu/P) (24). To promote the formation of the disulfide bond between a cysteine pair in the T1-T1 interface, the cytoplasmic side of the inside-out patches was treated for ∼5 min with fresh Cu/P. After Cu/P washout, 20 mm DTT was used to reduce the disulfide bond (5), or 400 μm MTSET was employed to test for the presence of free thiolate groups.

Protein Biochemistry

The Kv4.2-T1 domain with a poly-His tag at the N terminus was expressed in bacteria and purified by a standard Ni2+ column protocol as described previously (4). The T1 protein was in a Tris-buffered saline solution of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mm NaCl. The protein was incubated with 2 mm GSH for at least ∼20 min at room temperature. After reaction with GSH, the sample was prepared either for atomic absorption measurements or for fast protein liquid chromatography analysis as described previously (3). Atomic absorption spectroscopy was performed on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences AAAnalyzer 600 in the Chemistry Department of Rice University (Houston, TX). Zn2+ absorption was read at 213.9 nm with a slit width set at 0.7 nm. Commercially available Zn2+ standards to quantify the Zn2+ content in dilute nitric acid were used to make a standard curve. Spiked Zn2+ standards in the phosphate-buffered saline background were also prepared to calibrate the standard curve for the protein samples. No difference was found between the diluted nitric acid and the phosphate-buffered protein background matrix. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm and corrected for light scattering, if necessary, with an extinction coefficient of 1 A280 unit per ml/mg of protein.

To confirm the formation of the disulfide bond across the T1-T1 interface, T293 cells were grown in 6-well plates (35-mm wells) in Opti-MEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells at ∼70% confluence were transfected with cytomegalovirus promoter plasmids for Kv4.1 constructs plus KchIP3 and enhanced green fluorescent protein (1 μg:1 μg:0.5 μg) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were placed in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline with divalents (Invitrogen) at room temperature. For NO treatment, 1 ml of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solution with 1 mm MAHMA-NONOate was added twice to the bath for 10 min each. The solution was removed, and cells were solubilized in 100 μl of SDS sample buffer. Half of each sample was treated with 200 mm DTT prior to running on a 6% SDS-PAGE gel. Gels were transferred to Immobilon (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and Western blotted with anti-Kv4.1 (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel) at 1:400 and detected with goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (Pierce) at 1:5000. Exposures were 10 s in Pico ECL (Pierce) on BIOMAX MR film (Kodak, New Haven, CT).

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Voltage clamp protocols and data acquisition were controlled by a Pentium-4 class desktop computer interfaced to a 12-bit analog/digital converter (Digidata 1200) or a 16-bit analog/digital converter (Digidata 1322) and driven by Clampex 8.0 or 9.0 (Axon Instruments). Clampfit 8.0 or 9.0 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 7.0 (Origin Lab Inc.) were used for data reduction and analysis. The time courses of peak current inhibition were evaluated quantitatively by assuming exponential decays to estimate the time constants and fractional currents at steady state. Data from at least three patches for each measurement are presented as mean ± S.E. The one-way analysis of variance test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences between two groups of data.

RESULTS

Zn2+ Site Cysteines Are Major Targets of Nitrosative Modulation in a Kv4 Channel Complex

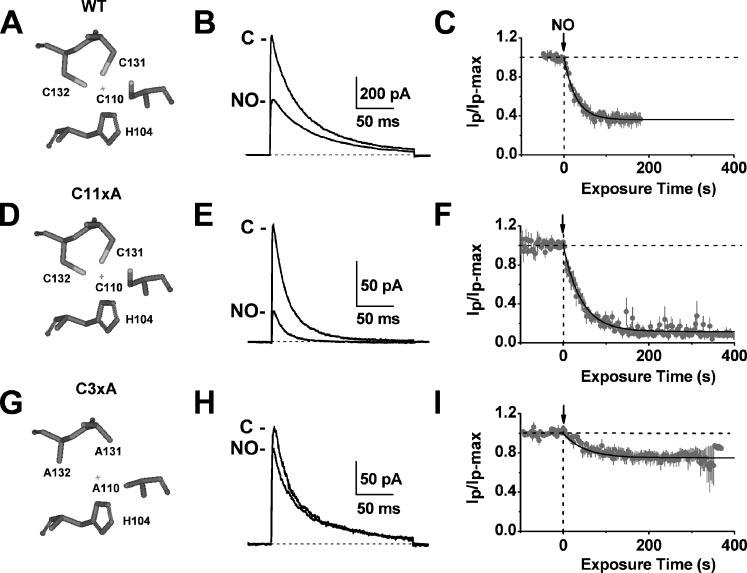

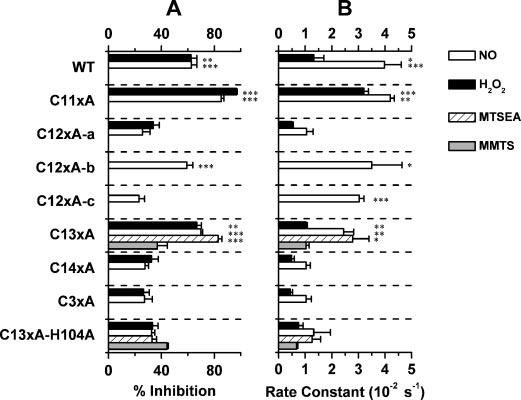

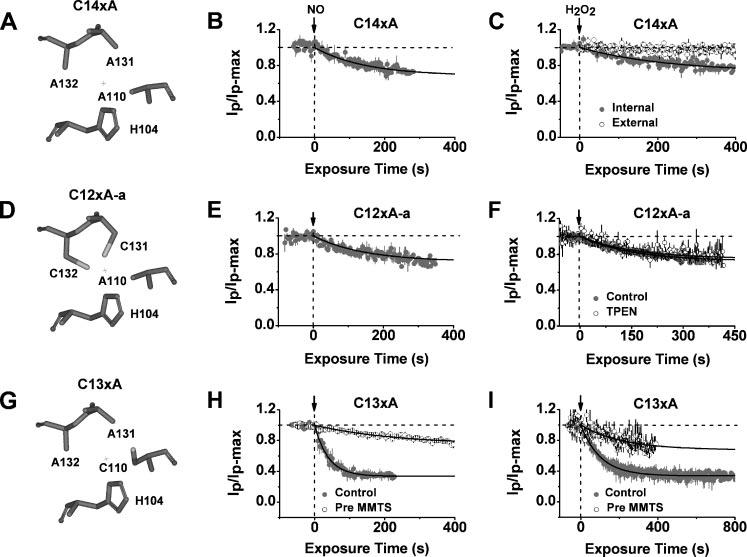

Upon application of the fast NO donor MAHMA-NONOate (100 μm) to the cytoplasmic side of inside-out patches of Xenopus oocyte expressing the ternary wild-type (WT) Kv4 channel complex (Kv4.1 + KChIP1 + DPPX-S, see “Experimental Procedures”), the outward K+ currents were inhibited quickly and profoundly (Figs. 2, A-C, and 6). The time course of this inhibition was approximately exponential with the following best-fit rate constant (ko = 1/τ) and % inhibition at steady-state (I%): 0.040 ± 0.006 s−1 and 63 ± 4%, respectively. The inhibition was similarly fast (0.042 ± 0.001 s−1) but more profound (85 ± 2%) when all intracellular cysteines but the three in the T1 Zn2+ site (Cys-110, Cys-131, and Cys-132) were mutated to alanines in the C11xA mutant (Figs. 2, D-F, and 6). DEA-NONOate, a slower NO donor (see “Experimental Procedures”) produced a similar result (data not shown). In sharp contrast, the inhibition was greatly suppressed when the three Zn2+ site cysteines were mutated to alanines in the C3xA mutant (Figs. 2, G-I, and 6) or when all 14 internal cysteines were mutated to alanines in a C14xA mutant (“Cys-less”; Figs. 3, A and B, and 6). Both the ko and I% were reduced ∼3-fold relative to values from the C11xA mutant. The residual slow response may arise from nonspecific nitrosation or oxidation of non-cysteine residues (e.g. Met, Ser, and Tyr) in the Kv4 channel complex (25), because gating of the C14xA mutant co-expressed with KChIP1 and DPPX-S was not affected by thiol-specific reagents (5). In this study, this small and slow cysteine-independent response was not investigated further, and we regard it as background inhibition. The specific inhibition was not caused by a by-product of MAHMA-NONOate or DEA-NONOate decomposition upon NO release, because washout did not reverse it and application of the exhausted NO-donor had no effect on the Kv4 current (data not shown). Once released from its donor, NO is highly labile; therefore, internally applied H2O2, which is relatively stable, was also used in several experiments as a control reagent to verify the functional role of the cysteines in the T1 Zn2+ site. Under identical conditions, high concentrations of H2O2 yielded results that were qualitatively similar to those obtained with NO: the rate and degree of inhibition of the Kv4 channel complex depended sharply on the presence of cysteines in the T1 Zn2+ site (Fig. 3C, and see Fig. 6, and supplemental Fig. S1). Lower concentrations of H2O2 were also attempted; however, the slow rate to the inhibition under these conditions made these experiments generally impractical for quantitative analysis due to the limited lifetime of the inside-out patches. The role of external cysteines in these responses is unlikely, because, in agreement with previous studies, the external application of H2O2 had no effect on the Kv4 current (Fig. 3C) (26, 27).

FIGURE 2. Inhibition of the Kv4.1 channel by NO.

Left, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in WT (A), C11xA (D), and C3xA (G). The “+” represents the location of the Zn2+ atom as found in the crystal structure of the isolated Kv4.2-T1 domain (2). Middle, WT (B), C11xA (E), and C3xA (H) currents from inside-out patches before and after the internal application of 100 μm MAHMA-NONOate. All channels were co-expressed with DPPX-S and KChIP-1 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Currents were evoked by a step depolarization from a holding potential of −100 mV to +80 mV (start-to-start interval was 3 s). Right, the normalized peak currents plotted against time for WT (C), C11xA (F), and C3xA (I). Solid lines are best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 28 s (0.36), 42 s (0.12), and 50 s (0.75) for WT, C11xA, and C3xA, respectively.

FIGURE 6. Summary of the modulation of Kv4.1 wild-type and mutant channels by reagents that target the T1 Zn2+ site.

A, percent inhibition; B, best-fit inhibition rate constant. For H2O2 and NO, the differences against C14xA are statistically significant at p < 0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), and <0.001 (***) (one-way analysis of variance test, n = 4–8). For MMTS and MTSEA, the control is C13xA-H104A.

FIGURE 3. Inhibition of Kv4.1 Zn2+ site mutants by NO and H2O2.

Left, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in C14xA (A), C12xA-a (D), and C13xA (G). Middle, time-dependent inhibition of C14xA (B), C12xA-a (E), and C13xA (H) by internally applied MAHMA-NONOate (100 μm). Solid lines are best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 145 s (0.69), 146 s (0.71), and 39 s (0.35), for C14xA, C12xA-a, and C13xA, respectively. When pretreated with MMTS (hollow symbols; H), the inhibition of the C13xA mutant channel was suppressed (best-fit time constant and fractional current were 240 s and 0.74, respectively). Right, time-dependent inhibition of C14xA (C), C12xA-a (F), and C13xA (I) by internally applied H2O2 (58 mm). Solid lines are best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 238 s (0.70), 152 s (0.72), and 102 s (0.34) for C14xA, C12xA-a, and C13xA, respectively. External application (hollow symbols) had not effect (C). The presence of 20 μm TPEN (hollow symbols) did not affect the inhibition of the C12xA-a mutant channel (F). When pretreated with 1 mm MMTS (hollow symbols; I), the inhibition of the C13xA mutant channel was suppressed (best-fit time constant and fractional current are 217 s and 0.68, respectively. All plots were generated as explained in Fig. 2 legend.

Cys-110 Plays a Central Role in Redox Modulation of the Kv4 Channel Complex

To determine which Zn2+ site cysteine in the T1-T1 interface may underlie the nitrosative modulation, we probed two additional mutants: C12xA-a and C13xA. The former has two internal cysteines (Ala-110, Cys-131, and Cys-132) from one side of the interface (Fig. 3D), and the latter has one internal cysteine only (Cys-110, Ala-131, and Ala-132) from the other side of the interface (Fig. 3G). Thus, no disulfide bridges can be formed across the interface upon oxidation. Like mutants C13xA and C14xA, the C12xA-a mutant only exhibited a background response when MAHMA-NONOate or H2O2 were applied internally (Figs. 3, E and F, and 6); but the C13xA mutant, which carries Cys-110 only was inhibited rapidly and more severely by MAHMA-NONOate (ko = 0.025 ± 0.004 s−1 and I% = 70 ± 1%) or H2O2 (ko = 0.010 ± 0.001 s−1 and I% = 67 ± 4%) than C12xA-a (p < 0.005; Figs. 3, H and I, and 6). Any additional sensitivity of the C12xA-a mutant could not be uncovered even by chelating any possible protective Zn2+ with 20 μm TPEN, a high affinity Zn2+ chelator (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that Cys-110 plays a unique and critical role in redox modulation of the Kv4 channel complex. Supporting this conclusion, Cys-110 was protected by pre-forming a thiol-specific adduct with MMTS (a non-polar methanethiosulfonate reagent) in the C13xA mutant (see “Experimental Procedures”). This treatment reduced the subsequent responses to MAHMA-NONOate and H2O2 to levels that were close to background (Fig. 3, H and I).

Combined Presence of Cys-110 and His-104 Is Sufficient to Observe Nitrosative Modulation of the Kv4 Channel Complex

The above findings were surprising, because modification of any cysteine in the Kv4.1-T1 Zn2+ site by MTSET induces profound inhibition of the channel, which may result from steric and/or electrostatic interactions in the T1-T1 interface (5). The selective inhibition of the C13xA mutant (Cys-110 only) by nitrosation and oxidation suggests that modification of any individual Zn2+ site cysteine is not always sufficient to produce the robust inhibition; therefore, it is necessary to consider more specific interactions that require a particular location and orientation of the groups involved. In the C13xA mutant, two Zn2+-coordinating residues, Cys-110 and His-104, are located in vicinal subunits across the T1-T1 interface (Fig. 4A). Although the thil group (-SH) of Cys-110 cannot form a strong H-bond with His-104, Cys-110 that is oxidized by NO or H2O2 could provide a strong proton donor (S-NO or S-OH) or acceptor (S-NO, SO−2 or SO−3) to form an H-bond with the imidazole group of His-104, which is a strong proton donor or acceptor at physiological pH (28). Thus, mutation of either Cys-110 or His-104 to alanine should suppress the inhibition, because the non-polar side chain of alanine cannot serve as a strong proton donor or acceptor to form the H-bond (28). Accordingly, the mutants C14xA (Cys-less; His-104 is the sole Zn2+ ligand remaining) and C13xA-H104A (Cys-110 only) exhibited responses to NO or H2O2 that were indistinguishable from background (ko = 0.007- 0.013 s−1 and I% = 27%; Figs. 4, C and D, and 6). Similar results were obtained with C13xA-H104Q and C13xA-H104L (data not shown).

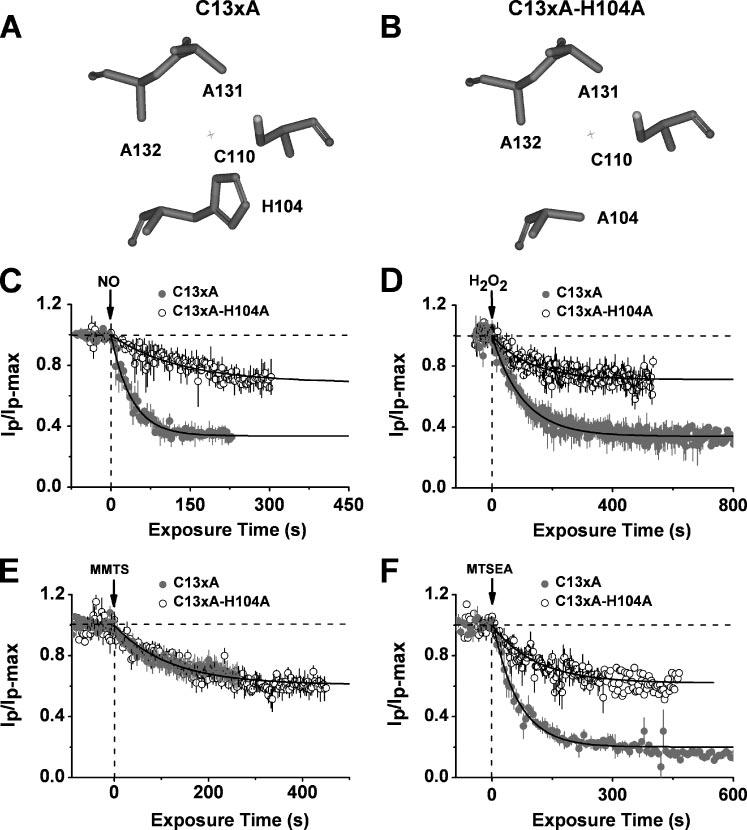

FIGURE 4. The presence of Cys-110 and His-104 is sufficient to observe the inhibition of Kv4.1 channels by NO, H2O2, and MTSEA.

Upper, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in C13xA (A) and C13xA-H104A (B). Below, time-dependent inhibition of C13xA (solid symbols) and C13xA-H104A (hollow symbols) mutants by internally applied 100 μm MAHMA-NONOate (C), 58 mm H2O2 (D), 1 mm MMTS (E), and 200 μm MTSEA (F). For C13xA, solid lines are best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 39 s (0.35) (C), 102 s (0.34) (D), 166 s (0.69) (E), and 63 s (0.20) (F). For C13xA-H104A mutant, solid lines are best-fit exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 147 s (0.66) (C), 126 s (0.71) (D), 166 s (0.69) (E), and 110 s (0.62) (F). All plots were generated as explained in the Fig. 2 legend.

The H-bond hypothesis predicts that any modification of Cys-110 that promotes the formation of an H-bond with the His-104 should inhibit the channel profoundly. Thus, we carried out additional experiments with two internally applied thiol-specific MTS reagents: MMTS, which adds a methyl group (−CH3) to the reacting cysteine but cannot serve as a strong proton donor or acceptor, and MTSEA, a strong proton donor, which adds the ammonium group (−NH3) to the reacting cysteine. As expected, MMTS inhibited the C13xA mutant less effectively than MTSEA (MMTS: ko = 0.010 ± 0.001 s−1 and I% = 37 ± 8%; MTSEA: ko = 0.016 ± 0.006 s−1 and I% = 83 ± 3%; Figs. 4, E and F, and 6), and furthermore, the H104A mutation prevented the inhibition by MTSEA but had no effect on the response induced by MMTS (Figs. 4, E and F, and 6). H104L and H104Q produced similar results (data not shown). Thus, a putative H-bond between a highly oxidized form of Cys-110 and the imidazole group of His-104 may be responsible for the nitrosative regulation of the mutant Kv4 channels that may favor the interaction between those residues (see “Discussion”).

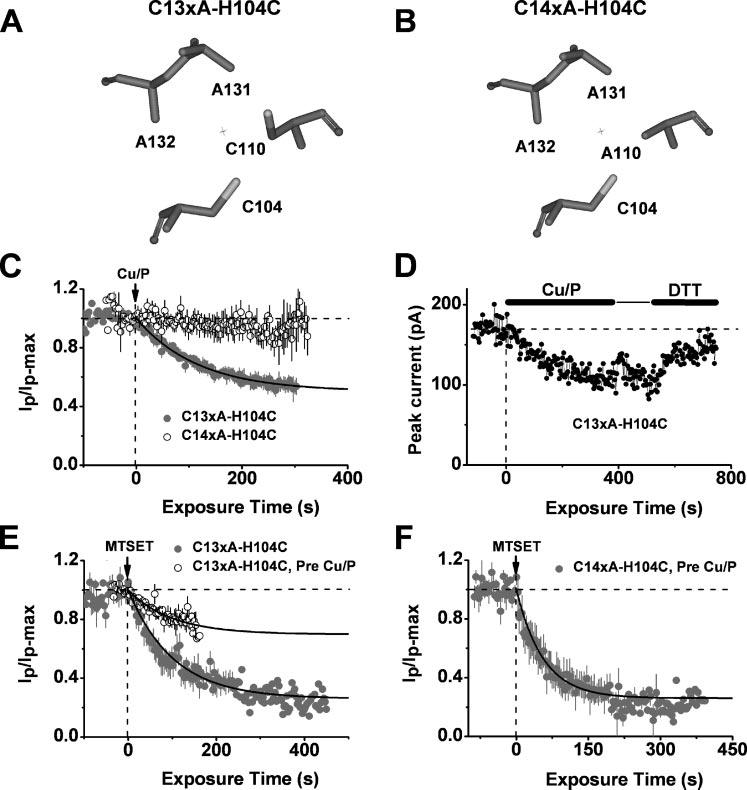

Are Cys-110 and His-104 sufficiently close to permit the formation of the putative H-bond? To answer this question, we tested whether a disulfide bond between Cys-110 and Cys-104 (i.e. H104C) can clamp the T1-T1 interface under mild oxidizing conditions and thereby inhibit the channel. Previously, we used this strategy to show that the T1-T1 interface is dynamic (9). Similarly, the current from the C13xA-H104C mutant (Fig. 5A) was inhibited upon exposing the cytoplasmic side of the patch to Cu-phenanthroline (Cu/P, a mild oxidizing agent, Fig. 5C). Consistent with the formation of a disulfide bond between Cys-110 and Cys-104, this inhibition was not observed when Cys-110 was mutated to alanine (Fig. 5, B and C) and was reversed by the application of 20 mm DTT (see “Experimental Procedures”) (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the robust inhibition of the C13xA-H104C mutant by MTSET was significantly suppressed upon pre-oxidation of the cysteine pair with Cu/P. This result suggests that pre-forming a disulfide bond with Cys-110 prevents the reaction with MTSET. Supporting this interpretation, the protective effect of a disulfide bond against MTSET was eliminated by the C110A mutation (Fig. 5, E and F).

FIGURE 5. Disulfide cross-linking across the T1-T1 inter-subunit interface inhibits the Kv4.1 channel.

Upper, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in C13xA-H104C (A) and C14xA-H104C (B). Below, C, inhibition of a Kv4.1 mutant (C13xA-H104C) by internally applied Cu/P. Solid line is the best-fit single exponential decay with the following time constant and fractional current level at steady-state (in parentheses): 115 s (0.50). The mutant C14xA-H104C exhibited no response. D, reversibility of the Cu/P-induced inhibition of the C13xA-H104C mutant by DTT (20 mm). E, pretreatment of C13xA-H104C with Cu/P reduced the fractional current level upon inhibition by MTSET from 0.27 to 0.77 without changing the time constant (∼91 s). F, for the mutant C14xA-H104C channel with Cys-104 only, pretreatment of Cu/P did not affect inhibition of the channel by MTSET. The best-fit single exponential decay gave the following time constant and fractional current level at steady-state (in parentheses): 56 s (0.26). All plots were generated as explained in the Fig. 2 legend, except the plot in panel D, which was not normalized.

Zn2+ Site in the Kv4 T1-T1 Interface Is a Redox Switch

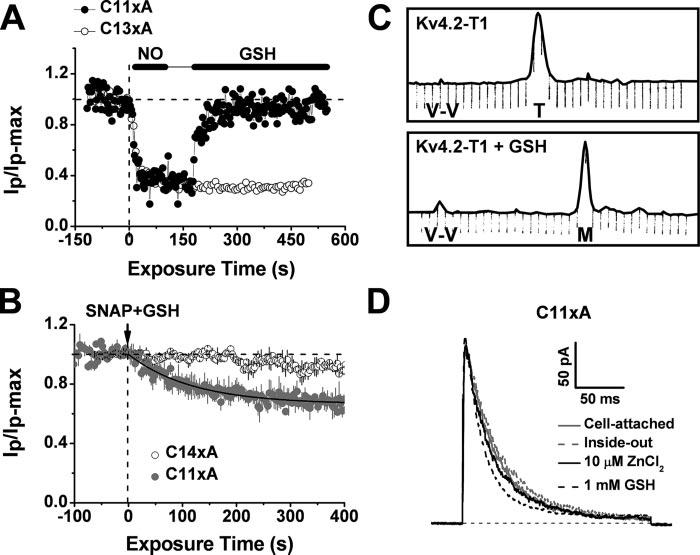

Previous studies showed that NO can induce the formation of a disulfide bond when the thiolate groups of two cysteines are in close proximity (14, 29). Once the first cysteine is nitrosylated, the sulfur atom becomes vulnerable to nucleophilic attack by a free thiol group from a nearby cysteine, causing release of the NO group and subsequent disulfide bond formation before the first cysteine becomes highly oxidized (29). In this case, the disulfide bond can be reversed by a reducing reagent, but the highly oxidized product cannot. As expected, application of 10 mm reduced GSH to the cytosolic side of a patch reversed the rapid NO-induced inhibition of the C11xA mutant quickly and completely. In contrast, the inhibition of the C13xA mutant, which retained Cys-110 and His-104 at the T1 Zn2+ site, was irreversible (Fig. 7A). GSH per se had little or no effect on the C11xA current (Fig. 7D). Preferentially, disulfide bonding may occur between Cys-132 and Cys-110 upon nitrosation because the C12xA-b mutant (Table 1) was significantly inhibited by exposure to MAHMA-NONOate (Fig. 6), and this inhibition was fully reversed by GSH (data not shown). Using a mild oxidizing reagent in a previous study, we also inferred the preferential disulfide bonding between Cys-110 and Cys-132 (9). The presence of GSH-reversible NO modulation argues for a functional redox switch at the T1 Zn2+ site of the Kv4 channel complex. Consistent with this hypothesis, a redox buffer consisting of 1 mm SNAP (a slow NO donor, see “Experimental Procedures”) and 1 mm GSH inhibited the C11xA mutant but had little or no effect on the Cys-less C14xA mutant (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7. Evidence of a redox switch in the T1 Zn2+ site of Kv4.1 channels.

A, time course of the normalized peak current from C11xA (solid symbols) and C13xA (hollow symbols) mutants. GSH (10 mm) reversed the inhibition of the C11xA mutant by NO. In contrast, the inhibition of the C13xA mutant was not reversed. B, time course of the normalized peak current from C11xA (solid symbols) and C14xA (hollow symbols) mutants. The combined presence of 1 mm SNAP and 1 mm GSH served as a redox buffer and thus reduced the fast inhibition of the C11xA channel by NO (Fig. 2, E-F). The best-fit single exponential decay gave the following time constant and fractional current level at steady-state (in parentheses): 119 s (0.66). The C14xA channel was not responsive. C, fast protein liquid chromatography profile of the Kv4.2-T1 protein before (upper) and after (below) treatment with reduced GSH (2 mm) for 20 min. Normalized absorbance units were used at 280 nm. The expected elutions of the T1 tetramer and the T1 monomer are marked as “T” and “M” below the peak, respectively. “V-V” represents the void volume. The T1 domain Zn2+ content was not changed upon GSH treatment, as determined by atomic absorbance spectroscopy (see “Experimental Procedures”). D, outward macropatch currents induced by the Kv4.1-C11xA ternary complex (see “Experimental Procedures”). From the same patch under the conditions indicated in the graph, these currents were evoked by a depolarizing pulse from −100 to +80 mV. The inside-out patch was first exposed to a saturating concentration (10 μm) of internally applied ZnCl2, and then to 1 mm GSH 5 min later.

TABLE 1.

Nomenclature and cysteine content of Kv4.1 constructs

| Kv4.1 construct |

Number of intracellular Cysa |

Cys at the Zn2+ siteb |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 14c | Cys-110, Cys-131, and Cys-132 |

| C3xA | 11d | None |

| C11xA | 3 | Cys-110, Cys-131, and Cys-132 |

| C12xA-a | 2 | Cys-131 and Cys-132 |

| C12xA-b | 2 | Cys-110 and Cys-132 |

| C12xA-c | 2 | Cys-110 and Cys-131 |

| C13xA | 1 | Cys-110 |

| C13xA-H104A | 1 | Cys-110 |

| C13xA-H104C | 2 | Cys-110 and Cys-104 |

| C14xA | 0 | None |

| C14xA-H104C | 1 | Cys-104 |

All constructs include four extracellular cysteines: Cys-209, Cys-223, Cys-233, and Cys-338.

Except for three instances, His-104 is left intact in most constructs.

Fourteen intracellular cysteines were available: Cys-105, Cys-110, Cys-131, Cys-132, Cys-257, Cys-322, Cys-392, Cys-467, Cys-484, Cys-490, Cys-532, Cys-533, Cys-589, and Cys-642.

Eleven intracellular cysteines were available: Cys-105, Cys-257, Cys-322, Cys-392, Cys-467, Cys-484, Cys-490, Cys-532, Cys-533, Cys-589, and Cys-642.

The thiol group of GSH can also bind to Zn2+ with significant affinity (30). Thus, GSH may compromise the quaternary structure of the isolated Kv4 T1 tetramer, which depends on inter-subunit Zn2+ binding (Fig. 1B) (3). As expected, GSH dissociated the purified Kv4.2-T1 tetramer into T1 monomers (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, however, a Zn2+ atom remains bound to the T1 monomer (Fig. 7C, legend). Conceivably, GSH competes off the weak Zn2+-coordinating thiolate group of Cys-110 and thus dissociates the tetramer but fails to release the tightly bound intra-subunit Zn2+ coordinated by His-104, Cys-131, and Cys-132. Supporting the presence of a weak interaction between Cys-110 and Zn2+ in the intact channel, the C11xA mutant induced robust voltage-dependent currents with similar kinetics under the following experimental conditions (consecutively, in the same patch): the cell-attached configuration (the intact oocyte cytoplasm may contain both Zn2+ and GSH), inside-out configuration exposed to a Zn2+-free intracellular solution, 10 μm ZnCl2, and 1 mm internal GSH (Fig. 7D). Thus, the weak intersubunit Zn2+ bridge, unlike the disulfide or H-bond, would allow the conformational change in T1-T1 interface that is tightly coupled to voltage-dependent gating (9).

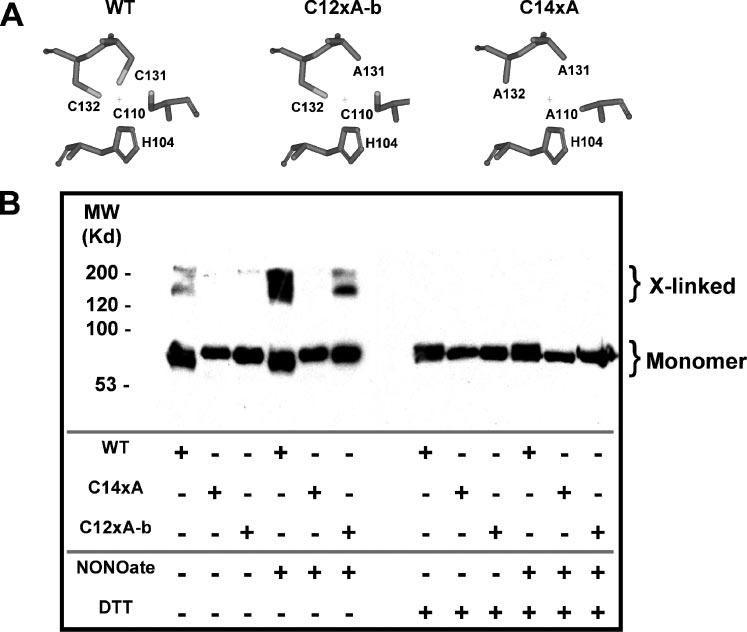

To confirm that the formation of a disulfide bond in the interfacial T1 Zn2+ site is the mechanism that underlies the modulation of the Kv4.1 channel by NO, we exposed intact T293 cells to MAHMA-NONOate and subsequently examined the oligomeric state of the channel by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Western blot analysis (Fig. 8B). Without MAHMA-NONOate, most of the protein from WT, C12xA-b, and C14xA (Fig. 8A) appeared as a monomer even in the absence of DTT. In contrast, when the cells were treated with MAHMA-NONOate a significant amount of the protein from WT and C12xA-b migrated as high molecular weight oligomeric complexes, but the C14xA protein remained monomeric. Furthermore, treating the WT and C12xA-b proteins with DTT shifted them to their monomeric configurations (Fig. 8B). Even a small amount of high molecular weight Kv4.1 protein, which is seen in both the WT and C12xA-b lanes under basal conditions, was eliminated by DTT treatment. Thus, the Kv4.1 subunits with all cysteines in the T1 Zn2+ site or two cysteines across the T1-T1 interface only (Cys-110 and Cys-132 in the Zn2+ site of the C12xA-b mutant) undergo disulfide cross-linking, which is significantly enhanced upon nitrosation, and as expected, NO-induced cross-linking does not happen when there are no intracellular cysteines. These results show that disulfide cross-linking between Cys-110 and Cys-132 occurs in intact mammalian cells and can be regulated dynamically by NO. Indirectly, these results also suggest that Zn2+ is not protecting Cys-132 in the intact cell; otherwise, Cys-132 would be involved in intra-subunit Zn2+ coordination, and therefore, unavailable to react with Cys-110.

FIGURE 8. Western blot analysis of Kv4.1 sensitivities to disulfide cross-linking upon exposure to NO.

A, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in WT, C12xA-b, and C14xA. B, Kv4.1 cDNAs (WT, C12xA-b, and C14xA) were co-transfected into T293 cells with KChIP3 and enhanced green fluorescent protein plasmids. Transfected cells were incubated with or without MAHMA-NONOate for 20 min immediately before solubilization in SDS sample buffer, SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, and Western blotting for Kv4.1 protein (anit-Kv4.1 antibody; see “Experimental Procedures”). The solubilized sample was divided in two equal portions, and half of each sample was reduced with DTT prior to loading the gel. The Kv4.1 construct used and treatment received for each sample are indicated by “+” signs above the respective lanes. Under reduced film exposure conditions a reduction in the monomer band intensity is clearly evident following NO-induced cross-linking (data not shown).

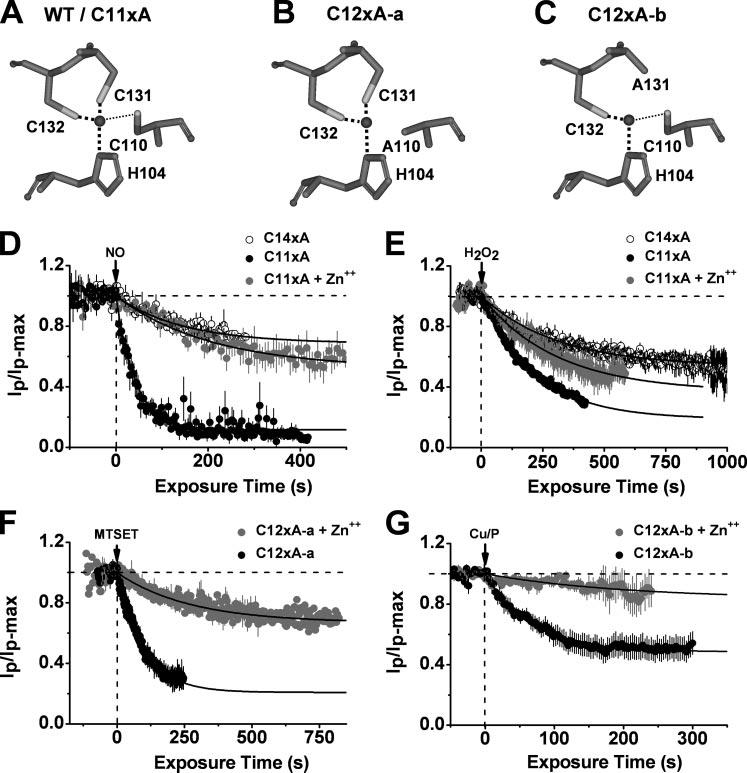

Zn2+ Protects the Kv4 Channel Complex against Nitrosative or Oxidative Inhibition

Although Zn2+ binding is not required for channel gating (Fig. 7D) (5, 6), intra-subunit Zn2+ binding could protect against the formation of an inhibitory disulfide bond induced by nitrosation. Accordingly, saturating concentrations of internal Zn2+ suppressed the inhibition of the C11xA mutant (Fig. 9A) by NO (Fig. 9D) and H2O2 (Fig. 9E), and the inhibition of the C12xA-a mutant (Table 1 and Fig. 9B; Cys-131, Cys-132, and His-104 are available) by MTSET (Fig. 9F). Even when Cys-110, Cys-132, and His-104 were left intact and Cys-131 was mutated to Ala (C12xA-b, Fig. 9C), the inhibition by Cu/P was greatly reduced in the presence of internal Zn2+ (Fig. 9G). These observations suggest that Zn2+ binding to the Kv4 T1 domain (involving Cys-131, Cys-132, and His-104) may protect the channel against nitrosative or oxidative inhibition by preventing the formation of the inhibitory interfacial disulfide bridge. Contrary to the other Zn2+ site cysteines, Cys-110 would be more susceptible to NO, because it is weakly bound to Zn2+. Supporting this hypothesis, the C11xA mutant was first slightly inhibited upon co-application of MAHMA-NONOate and ZnCl2 as seen before (background inhibition, Fig. 9D). During this period the unprotected Cys-110 may become nitrosylated; therefore, subsequent washout of both reagents quickly inhibited the mutant channel, because the removal of Zn2+ allows the close interaction between nitrosylated Cys-110 and the free thiol group of Cys-132 to form the disulfide bond (supplemental data, Fig. S2).

FIGURE 9. Zn2+-dependent modulation of the Kv4.1 channel inhibition by NO and H2O2.

Upper, simplified views of the T1 Zn2+ site residues in WT/C11xA (A), C12xA-a (B), and C12xA-b (C). The black spheres represent the Zn2+ atoms as found in the crystal structure of the isolated Kv4.2-T1 domain (2). The thick and thin dash lines represent strong and weak bond, respectively. Below, time-dependent inhibition of C11xA (solid) and C14xA (hollow symbols) by internally applied MAHMA-NONOate (100 μm) (D) or H2O2 (5.8 mm) (E) in the presence (gray) or absence (black) of a saturating concentration ZnCl2 (10 μm). C14xA is a control mutant without any intracellular cysteines. D, Zn2+ dependence of the inhibition of Kv4.1 Zn2+ site mutants by MAHMA-NONOate. The solid lines are the best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 42 s (0.12), 117 s (0.59), and 146 s (0.69) for C11xA, C11xA+Zn2+, and C14xA, respectively. E, Zn2+ dependence of the inhibition of Kv4.1 Zn2+ site mutants by H2O2. The solid lines are the best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 142 s (0.19), 217 s (0.36), and 308 s (0.58) for C11xA, C11xA+Zn2+, and C14xA, respectively. F, inhibition of the C12xA-a channel by MTSET (200 μm) in the absence (black) and presence (gray) of 10 μm ZnCl2. The solid lines are the best-fit single exponential decays with the following time constants and fractional current levels at steady-state (in parentheses): 39 s (0.21) and 108 s (0.67) for C11xA and C11xA+Zn++, respectively. G, Zn2+ dependence of the Cu/P-induced inhibition of the Kv4.1 mutant C12xA-b with Cys-110, Cys-132, and His-104 in the Zn2+ site only. The presence of Zn2+ increases the fractional current level from 0.52 to 0.83 and the time constant from 65 s to 202 s. All plots were generated as explained in the Fig. 2 legend.

DISCUSSION

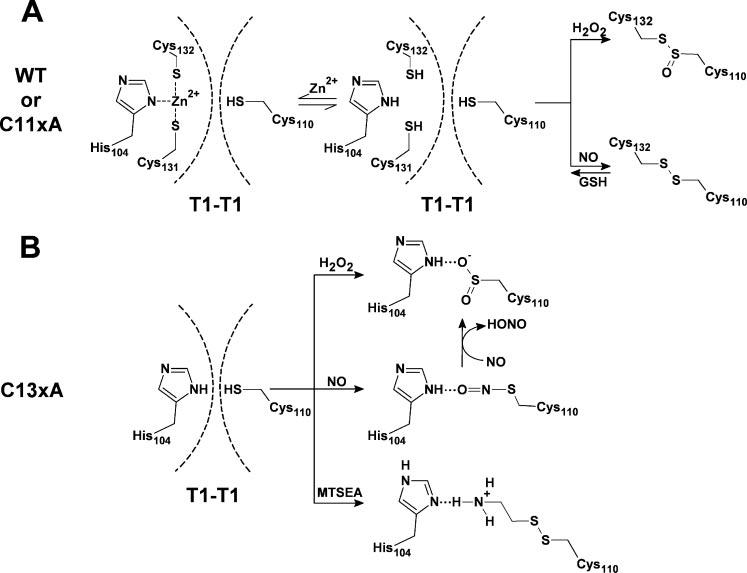

The intracellular T1 domain of Kv channels is a multitasking region that is responsible for subfamily-specific assembly, docking of auxiliary subunits, and gating (1, 2, 7, 9, 10). The role of the T1 domain in gating is puzzling, because the membrane spanning regions that constitute the Kv channel core control voltage-dependent gating and K+-selective permeation. Nevertheless, the T1-T1 intersubunit interface appears to undergo a conformational change coupled to voltage-dependent gating (9). In intact Kv4 channels, restriction of this conformational change by modification of specific T1 Zn2+ site cysteines hinders activation (5, 9). The T1-T1 conformational change may correspond to the cooperative introduction of a permissive closed state that precedes the opening of the pore. Thus, the T1-T1 interface would be a site where intracellular signaling molecules can modulate Kv4 channel gating effectively. The presence of the reactive cysteines in the T1 Zn2+ site of Kv4 channels makes this special location an attractive target for redox modulation. The results showed that the Kv4.1 channel is quickly and profoundly inhibited by intracellular NO in a Zn2+-dependent manner. This inhibition may involve two distinct and mutually exclusive interactions: 1) a disulfide bridge across the T1-T1 interface (Cys-110 to Cys-132) (Fig. 10A), which may be physiologically significant because a reducing agent (GSH) readily reverses the inhibition by NO, and 2) a putative H-bond between two interfacial Zn2+ site determinants, His-104 and Cys-110 (Fig. 10B). Given that the interfacial T1 Zn2+ site is highly conserved, it may act as a Zn2+-dependent redox switch in neuronal and cardiac tissues where Kv4 channels are key regulators of membrane excitability.

FIGURE 10. Working hypothesis of the Kv4 channel inhibition by three oxidants.

For WT and C11xA (A), Zn2+ is bound to Cys-131, Cys-132, and His-104 in the T1 domain of the intact Kv4.1 channel. Cys-110 interacts with Zn2+ weakly and thus the T1-T1 interface is dynamic. Dashed lines represent the boundaries of the T1-T1 interface. Even if Cys-110 is oxidized by H2O2 or NO, failure to form an H-bond or a disulfide bond across the T1-T1 interface prevents the modulation of the channel. However, once Zn2+ is released, nitrosylation of Cys-110 induces the formation of a disulfide bridge with Cys-132. High concentration of H2O2 may highly oxidize Cys-110 and thus form a thiolsulfinate with Cys-132, which cannot be reversed by GSH (33). In any case, straightjacketing the interface causes channel inhibition, as reported previously (9). For C13xA (B), oxidation of Cys-110 by H2O2 or NO or MTSEA induced an inter-subunit H-bond with the imidazole group of His-104 and thus inhibited the channel activity. The nitrosylated Cys-110 may be oxidized further by NO to sulfinic acid. The presence of GSH can only reverse the disulfide bond and the nitrosylation of Cys-110.

Molecular Interactions Responsible for the Redox Modulation at the T1 Zn2+ Site of a Kv4 Channel

In the Kv4.1 T1-T1 interface, Cys-131, Cys-132, and His-104 form a metal coordination complex with structural Zn2+ in a reduced intracellular environment (Fig. 10A). Patch excision may induce the release of Zn2+, and Cys-110 may be oxidized by H2O2, by MTSEA, or nitrosylated by NO. The modified or highly oxidized Cys-110 would then form an H-bond with the imidazole group of His-104 when Cys-131 and Cys-132 are not available (Figs. 4C, 4D, 4F, and 10B). Because the inhibition by NO and H2O2 is not reversed by GSH, we propose that the thiol group of Cys-110 is highly oxidized from (Cys-S-NO) or (Cys-S-OH) to (Cys-S-O2H) or (Cys-S-O3H) (Fig. 10B) (29, 31, 32). However, when Cys-132 and Cys-131 are available, the nitrosylated Cys-110 may prefer to form a disulfide bridge with the thiol group of Cys-132 (Fig. 10A). This event would, however, depend on the occupancy of the Zn2+ site, as discussed below. GSH did not reverse the inhibition by high concentrations of H2O2 even when the Zn2+ site cysteines are available (supplemental data, Fig. S1D). We propose that a highly oxidized Cys-110 forms a thiolsulfinate with the thiol group of Cys-132 (Fig. 10A) (33).

Supporting the proposed mechanisms (Fig. 10), structural studies have demonstrated that either hydrogen bonding or disulfide bridging at the active sites of enzymes are important interactions associated with modulation by oxidation. The former involves a single cysteine and a nearby non-cysteine residue, but the latter is formed between two adjacent cysteines. In any case, the reaction of NO and H2O2 with reactive thiols results in a local structural rearrangement that promotes enzyme activation or inactivation. For example, the Oδ3 atom of the oxidized Cys-25 forms H-bonds with His-159-Nδ1 in an inactive form of papain (34). In the flavoprotein NADH peroxidase with its native Cys-42-sulfenic acid redox center, Cys-42 Oδ is H-bonded to His-10 Nε2 (35, 36). H-bonding interactions involving oxidized cysteines are also found in human glutathione reductase (37), protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (38), and the photosensitive nitrile hydratase (39). In addition to the H-bonding interactions, disulfide bridging is also found in thiol-based regulatory switches with (RsrA, PerR, and Hsp33) or without (OxyR, OhrR, and CrtJ) metal involvement (12, 33, 40).

Although the proposed H-bond appears to be sufficient to straitjacket the T1-T1 interface and thus to inhibit channel activity, it may only be formed in the C13xA mutant. More likely, the native Kv4 channel complex employs thiol-disulfide exchange reactions at the Zn2+ site to regulate the channel's activity in response to reactive nitrosative or oxidative species under physiological conditions. However, nitrosative or oxidative stress could also produce irreversible thiolsulfinate or thiolsulfonate at the Zn2+ site under pathological conditions (33).

The Role of Zn2+ Binding in the Interfacial T1 Zn2+ Site of Kv4 Channels

Unlike the disulfide bridge or the H-bond, the intersubunit Zn2+ bridge involving Cys-110 may be weak and thus fails to inhibit channel activity by straightjacketing the dynamic T1-T1 interface. Previously, this possibility was considered likely because at least one cysteine at the Kv4-T1 Zn2+ site is free to react with MTSET in a Zn2+-independent manner (5). The new results reported here strongly suggest that Cys-110 is the free reactive cysteine. First, GSH appears to disrupt the interfacial Zn2+ bridge without affecting Zn2+ content and the Kv4.1 current (Fig. 7, C and D). Second, the presence of Zn2+ protects Cys-131 and Cys-132 from MTSET modification when His-104 is available (Fig. 9F). Third, the presence of Zn2+ appears to prevent the inhibitory interfacial disulfide bonds or thiolsulfinate induced by NO, Cu/P, or H2O2 (Fig. 9, D-F). Fourth, the presence of Zn2+ cannot prevent oxidation of Cys-110 by NO (supplemental data, Fig. S2). Finally, the Kv4.1 current is independent of Zn2+, GSH (Fig. 7D), Zn2+-binding cysteines, or TPEN (5) but tightly coupled to the conformational change in the T1-T1 interface (9). Therefore, Cys-110 is free or coordinates Zn2+ weakly to keep the T1-T1 interface functionally active and dynamic. A similar case was also found in latent human fibroblast collagenase whose activation depends on the dissociation of Cys-73 from a zinc-binding site (41). In contrast to the weak interfacial binding between Cys-110 and Zn2+, the coordination of Zn2+ by Cys-131, Cys-132, and His-104 is stronger, and therefore, elevated intracellular Zn2+ may prevent the nitrosative regulation (see below). Zn2+ protection against the effects of oxidation was also found in transcription factor proteins (33) and dimethylargininase-1, which is inhibited by Cys-S-nitrosylation (42).

Physiopathological Implications

Thiol-based redox cellular regulation in response to nitrosative, oxidative, or disulfide signaling has received significant attention (11, 12, 29, 33, 40, 43). In particular, several studies have suggested that the physiopathology of degenerative brain disorders is linked to intracellular Zn2+ homeostasis and oxidative/nitrosative stress (13, 17, 44-46). Therefore, the modulation of the neuronal Kv4 channel complex by nitrosative/oxidative stress is especially relevant. This channel complex underlies the somatodendritic A-type K+ current (ISA) (47-49), which regulates different aspects of neuronal excitability such as frequency of repetitive firing, dampening of back-propagating action potentials, and compartmentalization of dendritic action potentials. Therefore, ISA ultimately impacts somatodendritic signal integration (47, 50).

Under basal physiological conditions, Zn2+-buffering systems keep the concentration of free Zn2+ in the subnanomolar range (11, 51), and probably, there is an equilibrium between the Zn2+-bound and Zn2+-free species of the Kv4 channel. Thus, the Zn2+ site may undergo nitrosative redox modulation, which would induce a disulfide bond across the T1-T1 interface and thereby inhibit Kv4 channel gating. As a result, distal dendrites would become hyperexcitable. This modulation may depend on the concentrations of intracellular Zn2+. For instance, elevated intracellular Zn2+ resulting from intracellular Zn2+ overload or mobilization induced by enhanced synaptic activity or NO, respectively, may target the Kv4 Zn2+ site (11). Zn2+ binding may thus protect against nitrosation/oxidation by preventing disulfide bond formation across the T1-T1 interface or excessive cysteine oxidation. A local and rapid Zn2+ overload in dendritic spines may occur during excitotoxic activity, and NO signaling may mobilize Zn2+ by cysteine nitrosylation of critical Zn2+-buffering proteins (metallothioneins) (11, 46). Conceivably, protecting the activity of Kv4 channels by Zn2+ is an acute compensatory mechanism that helps to regulate electrical excitability under physiological and pathological conditions. This mechanism may account for nitrosative/oxidative modulation of the A-type K+ currents in neurons, heart, and smooth muscle (15, 18, 19, 21, 22). Furthermore, it may also confer Zn2+-dependent redox modulation to Kv2 and Kv3 channels, which share the T1-T1 Zn2+ site. Zn2+ protection and strong reducing conditions in normal cells may explain the resistance of the Kv4 channel to externally applied reactive oxygen species (26, 27, 52). This Zn2+-dependent redox regulation is distinct from that found in Kv1 channel complexes, where the Kv1-β subunits act as redox enzymes (53).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Bowlby (Wyeth Research, Princeton, NJ) for providing KChIP1 cDNA and Dr. Bernardo Rudy (New York University, New York, NY) for providing DPPX-S cDNA. Also, we thank members of the Covarrubias laboratory (Aditya Bhattacharji, Kevin Dougherty, and Thanawath Harris) for constructing Kv4.1 mutants for expression in mammalian T293 cells and verification of functional expression, and Dr. Toshinori Hoshi for suggesting SNAP as an alternative NO donor.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grants R01 NS032337 (to M. C.), P01 NS037444 (to P.J.P.), and Training Grant T32 AA07463 (to G. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

The abbreviations used are: KChIP, Kv channel-interacting protein; DPPX-S, dipeptidylaminopeptidase-like protein, isoform S; DTT, dl-dithiotreitol; SNAP, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine; MAHMA-NONOate, (Z)-1-(N-methyl-N-[6-(N-methylammoniohexyl)amino])diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate; DEA-NONOate, sodium 2-(N,N-dimethylamino)diazenolate-2-oxide; MTS, methanethiosulfonate; MTSET, 2-trimethylammonium ethyl methanethiosulfonate bromide; MMTS, methyl methanethiolsulfonate; MTSEA, 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate hydrobromide; TPEN, tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylendiamide; WT, wild type; Cu/P, copper-phenanthroline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bixby KA, Nanao MH, Shen NV, Kreusch A, Bellamy H, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:38–43. doi: 10.1038/4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanao MH, Zhou W, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8670–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432840100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strang C, Kunjilwar K, DeRubeis D, Peterson D, Pfaffinger PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31361–31371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahng AW, Strang C, Kaiser D, Pollard T, Pfaffinger P, Choe S. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:47885–47890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G, Shahidullah M, Rocha CA, Strang C, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;126:55–69. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunjilwar K, Strang C, DeRubeis D, Pfaffinger PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:54542–54551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor DL., Jr. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Yan Y, Liu Q, Huang Y, Shen Y, Chen L, Chen Y, Yang Q, Hao Q, Wang K, Chai J. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:32–39. doi: 10.1038/nn1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G, Covarrubias M. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;127:391–400. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long SB, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Science. 2005;309:897–902. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maret W. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2006;8:1419–1441. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paget MS, Buttner MJ. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao Q, Maret W. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:161–170. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton SA, Choi YB, Takahashi H, Zhang D, Li W, Godzik A, Bankston LA. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:474–480. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller W, Bittner K. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2990–2995. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gow A, Ischiropoulos H. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;282:L183–L184. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00424.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bossy-Wetzel E, Talantova MV, Lee WD, Scholzke MN, Harrop A, Mathews E, Gotz T, Han J, Ellisman MH, Perkins GA, Lipton SA. Neuron. 2004;41:351–365. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han NL, Ye JS, Yu AC, Sheu FS. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2167–2178. doi: 10.1152/jn.01185.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad M, Goyal RK. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:C671–C682. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00137.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruschenschmidt C, Chen J, Becker A, Riazanski V, Beck H. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:675–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozanski GJ, Xu Z. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1623–1632. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozanski GJ, Xu Z. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;282:H2346–H2355. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00894.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzhugh AL, Keefer LK. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:1463–1469. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Neuron. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoshi T, Heinemann S. J. Physiol. 2001;531:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serodio P, Kentros C, Rudy B. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1516–1529. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duprat F, Guillemare E, Romey G, Fink M, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:11796–11800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ippolito JA, Alexander RS, Christianson DW. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:457–471. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stamler JS, Hausladen A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:247–249. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neculai AM, Neculai D, Griesinger C, Vorholt JA, Becker S. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2826–2830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole LB, Karplus PA, Claiborne A. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claiborne A, Yeh JI, Mallett TC, Luba J, Crane EJ, III, Charrier V, Parsonage D. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15407–15416. doi: 10.1021/bi992025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox DE, Schenk AD, Feldman BM, Xu Y. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2001;3:549–564. doi: 10.1089/15230860152542925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamphuis IG, Kalk KH, Swarte MB, Drenth J. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;179:233–256. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crane EJ, III, Vervoort J, Claiborne A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8611–8618. doi: 10.1021/bi9707990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh JI, Claiborne A, Hol WG. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9951–9957. doi: 10.1021/bi961037s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker K, Savvides SN, Keese M, Schirmer RH, Karplus PA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Montfort RL, Congreve M, Tisi D, Carr R, Jhoti H. Nature. 2003;423:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nature01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noguchi T, Nojiri M, Takei K, Odaka M, Kamiya N. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11642–11650. doi: 10.1021/bi035260i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ilbert M, Graf PC, Jakob U. Antioxid, Redox. Signal. 2006;8:835–846. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springman EB, Angleton EL, Birkedal-Hansen H, Van Wart HE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:364–368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knipp M, Braun O, Gehrig PM, Sack R, Vasak M. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3410–3416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida T, Inoue R, Morii T, Takahashi N, Yamamoto S, Hara Y, Tominaga M, Shimizu S, Sato Y, Mori Y. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:596–607. doi: 10.1038/nchembio821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frederickson CJ, Koh JY, Bush AI. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:449–462. doi: 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capasso M, Jeng JM, Malavolta M, Mocchegiani E, Sensi SL. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:93–108. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda A. Biometals. 2001;14:343–351. doi: 10.1023/a:1012982123386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jerng HH, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:343–369. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jerng HH, Kunjilwar K, Pfaffinger PJ. J. Physiol. 2005;568:767–788. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Amarillo Y, de Miera EV, Ma Y, Mo W, Goldberg EM, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Neubert TA, Rudy B. Neuron. 2003;37:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birnbaum SG, Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Sweatt JD, Schrader LA. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:803–833. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colvin RA, Fontaine CP, Laskowski M, Thomas D. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;479:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akar FG, Wu RC, Deschenes I, Armoundas AA, Piacentino V, III, Houser SR, Tomaselli GF. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:H602–H609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00673.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Sci. STKE 2006. 2006:e33. doi: 10.1126/stke.3502006pe33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.