Worldwide about 1 million people die every year by suicide.1 In Canada an estimated 3665 individuals commit suicide each year, about 500 of whom are 15–24 years old.2 The effects of youth suicide go beyond the victim, affecting the parents, friends and communities of the deceased. Furthermore, youth who survive a suicide attempt continue to be at risk for completed suicide, violent death and poor psychological outcomes. Youth suicide elicits strong reactions from the public, policy-makers and health care providers and has recently been identified as a public health issue by national and provincial initiatives.

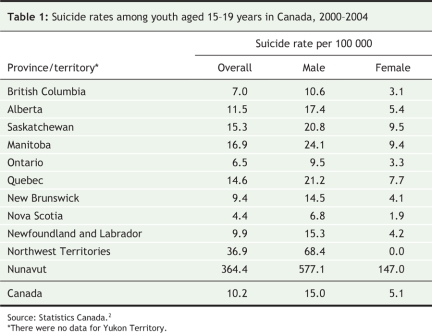

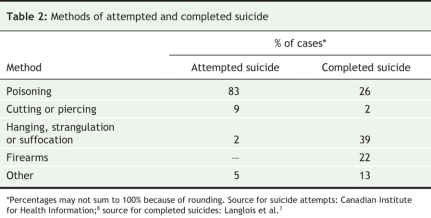

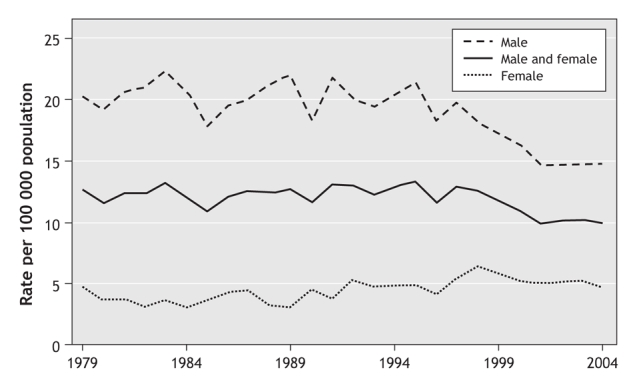

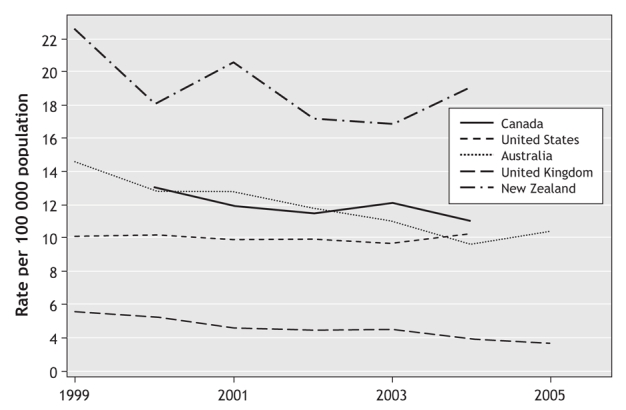

Comparatively, Canadian youth suicide rates, which have decreased in the past decade (Figure 1),2,3 are higher than the rates in the United States,4 Australia5 and the United Kingdom6 (Figure 2) and lower than the rate in New Zealand.7 However, there is substantial variability in regional rates across Canada (Table 1).2 The rate of suicide attempts has remained fairly stable, with youth making up 25% of associated hospital admissions.8 Data comparing rates of completed suicide and suicide attempts suggest that attempts are up to 12 times more common than completed suicides.3 There are sex-related differences in rates, with completed suicides being about 3–5 times more common among males and suicide attempts about twice as common among females.3 Table 2 shows the most common methods of attempted and completed suicide among Canadian youth.

Figure 1: Rates of suicide among youth aged 15–19 years in Canada, 1979–2004. Data source for 1979–1998: Langlois et al;3 data source for 2000–2004: Statistics Canada.2

Figure 2: Rates of suicide among people aged 15–24 years in Canada,2 the United States,4 Australia,5 the United Kingdom6 and New Zealand.7 Rates for Canada were calculated as weighted means for the combined age groups 15–19 and 20–24 years. Rates for the United Kingdom were calculated as weighted means for the combined male and female groups.

Table 1

Table 2

In general, intentional self-harm and motor vehicle crashes (sometimes also intentional) account for almost 60% of deaths among youth in Canada.9 Although the rate of death from suicide varies across regions of the country, the national rate is about 10 per 100 000 among youth 15–19 years old and 14 per 100 000 among people 20–24 years old.9 Globally, suicide is one of the top 3 causes of death among people 15–34 years old.1 Suicide ranks as an important, potentially preventable cause of death among youth and thus merits substantial public health concern.

Suicide risk factors

Recent systematic reviews have highlighted the current knowledge pertaining to youth suicide.10,11 In Canada, youth who are older, male, Aboriginal or white are more likely to commit suicide than are younger adolescents, children, females and black youth. Besides male sex, characteristics of those who attempt suicide and those who complete it are generally similar.12 Suicide risk factors among Aboriginal youth may differ from those influencing non-Aboriginals; however, substantial scientifically valid data regarding these issues are lacking,13 and there is a great need for rigorous research in this area.

Psychiatric disorders are the most significant risk factor for youth suicide, with over 90% of victims found (sometimes post mortem) to have at least 1 mental health disorder.10 The most common psychiatric diagnoses include affective, conduct and substance use disorders. Multiple psychiatric diagnoses, family history of suicide and previous suicide attempts increase the risk of suicide. Because youth is the life stage associated with onset of major mental health disorders,14 it is not surprising that suicide rates also rise in this age group.

Genetic and neuroendocrine studies have pointed to a number of factors that may be involved in suicidal behaviour independent of the neurobiology of affective disorders. These include low concentrations of serotonin metabolites (e.g., 5-hydroxytryptamine) and variations in genes related to serotonin synthesis (tryptophan hydroxylase), transport (SERT), signaling (HTR1A, HTR2A and HTR1B) and catabolism (MAOA).15 The relative or interactive effects of these factors are not yet understood.

In addition, a number of studies have attempted to link socioeconomic factors and suicide risk. Sexual orientation, social disadvantage, non-intact family of origin, parental history of mental health disorders, family history of suicidal behaviour, personal history of childhood physical or sexual abuse, and dysfunctional parent–child relationship have all been studied as risk factors for youth suicide.10 The causality or effect size of these factors is uncertain.

Other factors include suicide contagion and suicide clusters. The spatial or temporal clustering of suicides is more common among youth than among people in other age groups. Suicide contagion, a term for the spread of suicidal activity usually with reference to media influences, may be associated with sensationalist media reporting of suicide events in the community.10

Interventions

Strategies for suicide prevention frequently focus on risk factors. Ideally these strategies should target risk factors that have been shown to be both causal and modifiable. The scientific evidence for effective interventions is weak, but some strategies show promise.10,11 Much research in this area has suffered from substantial methodological problems, including but not limited to nonrandomization of interventions, the use of surrogate outcome measures, inadequate sample sizes and short duration of evaluation.

Suicide awareness curricula are often used as part of school-based suicide prevention strategies. However, there is little substantial evidence to support their implementation.10 Promising school-based programs include screening students for mental health problems and referring them to mental health professionals and providing teachers with “gatekeeper” training to recognize depression and other mental health disorders in students and to learn the procedures for referral to mental health services. Two other school-based strategies popularly considered to be effective are peer helper programs and postvention (suicide prevention activities, such as crisis debriefing interventions, aimed at youth recently exposed to a suicide). However, these strategies are not supported by sufficient positive evidence to substantiate widespread or unqualified use.16,17

Community-based suicide prevention strategies often target access to methods for self-harm, a known and modifiable risk-factor for suicide. For example, construction of bridge safety barriers, detoxification of cooking gas and car exhaust, changes to packaging of analgesics and restriction of firearms have all been cited as possible prevention strategies.10,11 However, difficulty in measuring direct effects of interventions in the presence of secular trends in suicide rates, coupled with the potential for method substitution, contributes to controversy surrounding the long-term effectiveness of these strategies.

Two other community-based strategies involve the education of media regarding responsible reporting of suicides and the provision of crisis hotlines. Media education programs have been associated with reduced suicide rates in Austria.18 As for crisis hotlines, there is little substantial evidence for their effectiveness in reducing suicide rates.11,19

One promising approach to suicide prevention using the health care system is the training of primary care physicians to recognize, treat and, if necessary, refer patients with mental illness, especially depression.20 Since the treatment of depression has been associated with decreased suicide rates and suicide attempts among youth,21,22 the effective early treatment of depression is an approach that targets a causal as well as a modifiable risk factor. In a national survey about mental health and illness in youth, most of the youth who participated reported that primary care physicians were their first choice for point of contact in case of distress.23 However, in a study assessing the standard of care for pediatric attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression in a region of Ontario, less than 12% of the family physicians surveyed reported comfort in their ability to recognize and treat depression in youth.24 Since training has been found to increase physician identification of suicidal patients25 and to improve treatment of depression and decrease suicide rates,26 it should be more widely available.

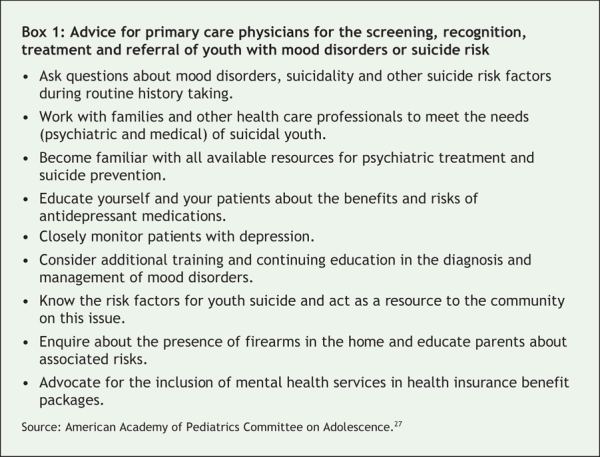

A recent clinical report published by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescents underscores the critical role of primary care physicians in the screening, recognition, treatment and referral of youth with mood disorders or suicide risk.27 This document recommends that pediatricians educate themselves and serve as a resource to the community about these issues (Box 1).

Box 1.

Conclusion

Youth suicide is an important public health issue. However, many of the prevention activities currently in place or identified in provincial strategies have not been shown to reduce suicide rates.28 Strategies proven effective in reducing suicide rates, such as early intervention for youth with mental health disorders, are often not available.29 As such, there is a misalignment between the suicide prevention approaches most often implemented and the approaches that have to date been shown to be most effective.

Unless suicide prevention strategies are developed and delivered on the basis of the best available evidence of effectiveness, health providers, parents, educators, politicians and the community may invest in programs that are ineffective or even harmful and deprive youth of programs that could help. The wish to do something should not override our responsibility to do the right thing.

Stanley P. Kutcher MD Department of Psychiatry Magdalena Szumilas HBSc Departments of Community Health and Epidemiology and of Psychiatry Dalhousie University Halifax, NS

Key points of the article

• Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth in Canada and one of the top 3 causes of death among youth worldwide.

• The suicide rate among Canadian youth aged 15–19 years is 10.2 per 100 000, with substantial variation across provinces and territories.

• The most substantial risk factors for youth suicide are mental health disorders, family history of suicide and previous suicide attempts.

• Other risk factors include genetic and neuroendocrine factors, socioeconomic factors, and environmental and contextual factors.

• Suggested prevention strategies are often school-based, with others being community- based or involving health care professionals.

• Scientific evidence for effective prevention strategies is weak, but some interventions, such as early identification and effective treatment of mental health disorders in youth, show promise.

• Canada's provinces and territories should implement prevention activities that have the best demonstrated scientific evidence of effectiveness.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. World health report: mental illness: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: The Organization; 2001.

- 2.Deaths, by selected grouped causes, age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories, annual [Table 102-0551; 269280 series]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2007. Available: http://cansim2.statcan.ca/cgi-win/cnsmcgi.exe?Lang=E&RootDir=CII/&ResultTemplate=CII/CII_pick&Array_Pick=1&ArrayId=102-0551 (accessed 2007 Nov 7).

- 3.Langlois S, Morrison P. Suicide death and attempts. Health Rep 2002;13:9-23. [PubMed]

- 4.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NCHS mortality table GMWK12: Death rates for 358 selected causes, by 10-year age groups, race, and sex: United States, 1999–2004. Atlanta: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

- 5.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Suicides. Table 4: Suicide, age-specific death rates (a)-10 year age groups. Canberra: The Bureau; 2005. Cat no 3309.0.

- 6.Office for National Statistics. Mortality statistics: cause. Table 4: Death rates per million population: selected underlying cause, sex and age-group, 1998–2005, England and Wales [Series DH2 no 26-3]. London (UK): The Office; 2005.

- 7.New Zealand Health Information Service. Suicide facts: 2004–2005 data. Table 5: Suicide deaths and age-specific rates, by sex, 15–24 years, 1948–2004. Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Health; 2006.

- 8.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospitalizations due to suicide attempts and self-inflicted injury in Canada, 2001–2002. In: National Trauma Registry Analytic Bulletin. Toronto: The Institute; 2004.

- 9.Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. The CASP blueprint for a Canadian national suicide prevention strategy. Edmonton: The Association; 2004. Available: www.thesupportnetwork.com/CASP/blueprintE.pdf (accessed 2007 Nov 7).

- 10.Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, et al. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention. Acting on what we know: preventing youth suicide in First Nations. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003.

- 14.Health Canada. A report on mental illnesses in Canada [report no 0-662-32817-5]. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2002.

- 15.Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003;4:819-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lewis MW, Lewis AC. Peer helping programs: Helper role, supervisor training, and suicidal behavior. J Couns Develop 1996;74:307-13.

- 17.Hazell P, Lewin T. An evaluation of postvention following adolescent suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:101-9. [PubMed]

- 18.Etzersdorfer E, Sonneck G. Preventing suicide by influencing mass-media reporting: the Viennese experience 1980–1996. Arch Suicide Res 1998;4:67-74.

- 19.Gould MS, Kalafat J, Harrismunfakh JL, et al. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 2: suicidal callers. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007;37:338-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Beautrais A, Fergusson D, Coggan C, et al. Effective strategies for suicide prevention in New Zealand: a review of the evidence. N Z Med J 2007;120:U2459. [PubMed]

- 21.Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, et al. The relationship between antidepressant medication use and rate of suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:165-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Simon GE, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1029-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Davidson S, Manion IG. Canadian Youth Mental Health and Illness Survey: survey overview, interview schedule and demographic cross tabulations. Ottawa: Canadian Psychiatric Association; 1993.

- 24.Kotowycz N, Crampton S, Steele M. Assessing the standard of care for pediatric ADHD and depression in Elgin County. Paper presented at the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry annual meeting; 2003 Nov 3; Halifax.

- 25.Pfaff JJ, Acres JG, McKelvey RS. Training general practitioners to recognise and respond to psychological distress and suicidal ideation in young people. Med J Aust 2001;174:222-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Rutz W, von Knorring L, Walinder J. Long-term effects of an educational program for general practitioners given by the Swedish Committee for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992;85:83-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Shain BN, Committee on Adolescence. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics 2007;120:669-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Breton JJ, Boyer R, Bilodeau H, et al. Is evaluative research on youth suicide programs theory-driven? The Canadian experience. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2002;32:176-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kirby MJL, Keon WJ. Out of the shadows at last: transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada. Ottawa: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2006.