Abstract

Mast cells secrete various substances that initiate and perpetuate allergic responses. Cross-linking of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcɛRI) in RBL-2H3 and bone marrow–derived mast cells activates sphingosine kinase (SphK), which leads to generation and secretion of the potent sphingolipid mediator, sphingosine-1–phosphate (S1P). In turn, S1P activates its receptors S1P1 and S1P2 that are present in mast cells. Moreover, inhibition of SphK blocks FcɛRI-mediated internalization of these receptors and markedly reduces degranulation and chemotaxis. Although transactivation of S1P1 and Gi signaling are important for cytoskeletal rearrangements and migration of mast cells toward antigen, they are dispensable for FcɛRI-triggered degranulation. However, S1P2, whose expression is up-regulated by FcɛRI cross-linking, was required for degranulation and inhibited migration toward antigen. Together, our results suggest that activation of SphKs and consequently S1PRs by FcɛRI triggering plays a crucial role in mast cell functions and might be involved in the movement of mast cells to sites of inflammation.

Keywords: sphingosine kinase, S1P receptors, RBL-2H3 cells, motility

Introduction

Mast cells play pivotal roles in immediate-type and inflammatory allergic reactions that can result in asthma. Cross-linking of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcɛRI) on these cells activates signaling pathways that lead to degranulation and the release of histamine and other preformed mediators, as well as de novo synthesis of the arachidonic acid metabolites, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins. Infiltration of airway smooth muscle by mast cells is associated with the disordered airway function found in asthma (1). Although mast cells also synthesize and release several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines capable of recruiting eosinophils, monocytes, and T cells, it is not well understood how mast cells themselves are recruited.

An addition to the recognized repertoire of FcɛRI-mediated signaling events is the activation of sphingosine kinase (SphK), which results in conversion of sphingosine to the novel sphingolipid mediator, sphingosine-1–phosphate (S1P; references 2–4). In rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cells, FcɛRI cross-linking leads to activation of SphK and formation of S1P, which acts as a second messenger to mobilize calcium from intracellular stores by an InsP3-independent pathway (2). Similarly, in human bone marrow–derived mast cells (BMMCs), aggregation of FcɛRI resulted in activation of phospholipase D, leading to activation of SphK1, which mediated rapid calcium release from intracellular stores (5).

Recently, the intracellular actions of S1P have been a matter of great debate due to the discovery that S1P is a ligand for a family of five specific G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) known as S1P1–5 (6). These S1PRs are differentially expressed and coupled to a variety of G proteins; they regulate diverse signaling pathways. In particular, S1PRs have been shown to play critical roles in cell migration (6). S1P1 is essential for lymphocyte trafficking and regulates egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs (7).

We showed previously that S1P levels were significantly increased in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from the lungs of asthmatics after challenge with an allergen (8) and, thus, it was of importance to examine the role of S1P formation and its receptors in mast cell function. Although expression of the S1P receptors, S1P1–4, has been detected in dendritic cells (9), to date, their expression in mast cells has not been reported, and previous studies with mast cells were not focused on the likely possibility of S1P receptor–mediated functions. In this paper, we show that FcɛRI triggering activates SphK type 1 in mast cells resulting in S1P secretion. In turn, S1P transactivates the cell surface receptors, S1P1 and S1P2, to modulate mast cell functions, such as migration toward antigen and degranulation, which are important for asthmatic and allergic responses.

Materials and Methods

Mast Cell Culture.

BMMCs were isolated from 8-wk-old SV129 × C57/bl6 wild-type and gene-disrupted mice and cultured as described previously (10). RBL-2H3 cells (CRL-2256; American Type Culture Collection) were grown as monolayer cultures in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM; Biofluids) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated FBS.

BMMCs were sensitized for 3 h with 1 μg/ml anti-DNP IgE in complete EMEM media without IL-3. RBL-2H3 cells were similarly sensitized for 12 h. Cells were washed and stimulated with 40 ng/ml or 100 ng/ml DNP-HSA (Ag) for BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells, respectively, or with 100 nM S1P unless specified otherwise.

Measurement of S1P.

Lipids were extracted from 5 × 106 RBL-2H3 cells, and supernatants and mass levels of S1P were determined as described previously (11).

SphK Assay.

SphK1 and SphK2 activities were measured as described previously (reference 12 and Supplemental Materials and Methods, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1).

Degranulation and Chemotaxis.

Degranulation of 106 mast cells was measured by assaying β-hexosaminidase release as described previously (13). Net degranulation is expressed as the percentage of total cellular β-hexosaminidase released to the medium after antigen stimulation minus that released spontaneously. Spontaneous release was always <5%. Chemotaxis was measured in a modified Boyden chamber using polycarbonate filters (25 × 80 mm, 8-μM pore size). Chemoattractants were added to the lower chamber, and 5 × 104 cells were added to the upper chamber. After 3 h, unless indicated otherwise, migrated cells were counted as described previously (14). Each data point is the average number of cells in four random fields (each counted twice) and is the mean ± SD of three individual wells.

RT-PCR and Ribonuclease Protection Assays (RPAs).

Total RNA was isolated from BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells with TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies) and digested with DNase (Promega). RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript II (Life Technologies). Sequences of oligonucleotide primers are provided in Table S1 (available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1).

For RPA, custom-made probe sets for mast cell lymphokines (50 ng) were labeled using the RiboQuant™ In Vitro Transcription Kit and hybridized with 10 μg RNA from 2 × 106 BMMCs using reagents provided in the RiboQuant™ RPA Kit (BD Biosciences) as described previously (13).

Transfection.

RBL-2H3 cells were electroporated with a Gene Pulser (BioRad Laboratories) at 250 mV and 500 μF using 25 μg DNA and 200,000 cells/μl in EMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. For transient expression, cells were allowed to recover for 24 h. For stable expression, cells were allowed to recover for 24 h. Cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were sorted with an argon dual laser flow cytometer (model 753; EPICS) and cultured in the presence of 1 mg/ml G418.

S1P2 cDNA was cloned from RBL-2H3 cells by PCR using the following primers: forward, 5′-CCCACCATGGGCGGTTTATACTCAGAG-3′; and reverse, 5′-CCACTGTGTTGCCCTCCAGAAATGTTG-3′. S1P1, S1P2, and SphK1 cDNAs were also cloned into pcDNA3.1-GFP for expression of the GFP fusion proteins.

SphK1 expression was down-regulated with sequence-specific small interfering (si) RNA. siRNA for rat SphK1, 5′-CUGGCCUACCUUCCUGUAGdTT-3′ and 5′-CUACAGGAAGGUAGGCCAGdTT-3′; rat SphK2, 5′-GCUGGGCUGUCCUUCAACCUdTT-3′ and 5′-AGGUUGAAGGACAGCCCAG-CdTT-3′; and control siRNA were synthesized at QIAGEN. 7 × 105 cells were transfected in six-well dishes for 3 h with the 21-nucleotide duplexes using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Expression of S1P1 and S1P2 were down-regulated by transfection with 18-mer phosphothioate oligonucleotides as described previously (15, 16). In brief, antisense S1P1, 5′-GACGCTGGTGGGCCCCAT-3′; sense S1P1, 5′-ATGGGGCCCACCAGCGTC-3′; scrambled S1P1, 5′-TGATCCTTGGCGGGGCCG-3′; antisense S1P2, 5′-CGAGTACAAGCTGCCCAT-3′; sense S1P2, 5′-ATGGGCAGCTTGTACTCG-3′; and scrambled S1P2, 5′-ACGTAGGGCTTGCCATTG-3′ were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. 7 × 105 cells were transfected with oligos at a final concentration of 1 μM in six-well dishes using Oligofectamine.

Measurement of MCP-1 and MIP1β.

Secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 (MIP1) β into the medium upon Ag challenge of 2 × 107 IgE-sensitized BMMCs was determined as described previously (13).

Confocal Microscopy.

RBL-2H3 cells were treated as described in figure legends, fixed in 3% formaldehyde, and visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy (LSM model 510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) with a 60× oil immersion objective (Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Statistical Analysis.

Experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results. Statistics were performed using SigmaStat 2.0. Differences between groups were determined with the paired Student's t test, or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey post-Hoc; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Online Supplemental Material.

For details regarding antibodies, Western blotting, confocal microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and S1P and SphK determinations, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Table S1 shows the sequences of the primers used for RT-PCR. Fig. S1 demonstrates that S1P induces internalization of S1P1 and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Fig. S2 depicts translocation of GFP-SphK1 to the plasma membrane after FcɛRI cross-linking, in contrast to GFP-SphK2 or GFP-vector. Fig. S3 demonstrates that IgE triggering activates SphK1 but not SphK2. Fig. S4 shows that FcɛRI cross-linking–induced internalization of S1P1 requires SphK. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1.

Results

FcɛRI Cross-linking Induces S1P Formation and Release from Mast Cells.

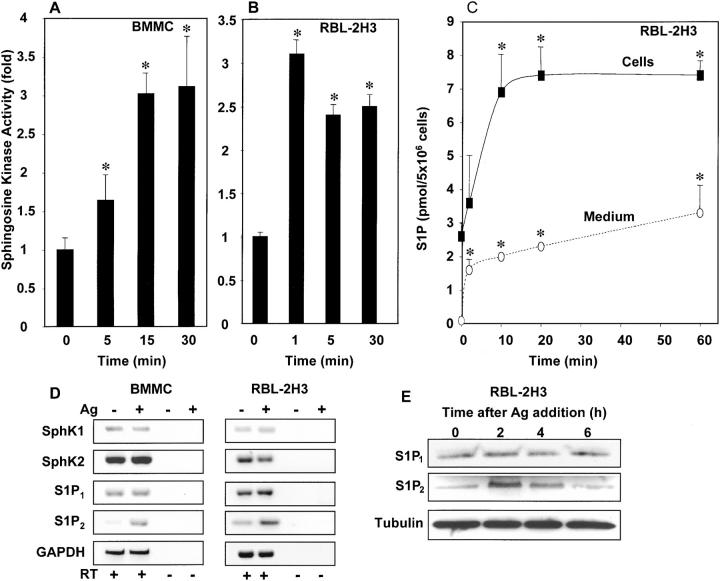

In agreement with previous papers (2, 4), FcɛRI cross-linking rapidly increased SphK activity in both BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 1, A and B). Consistent with the increased SphK activity measured in vitro, there was a concomitant rapid increase in intracellular levels of S1P that began to plateau within 10 min (Fig. 1 C). Direct mass measurements revealed that stimulated mast cells also secreted S1P into the medium. Significant secretion was detectable within 2 min and gradually increased after FcɛRI cross-linking (Fig. 1 C). These results are in agreement with a previous analysis showing that allergically activated CPII and BMMCs also release S1P into the supernatant (4). Importantly, IgE/Ag-activated RBL-2H3 cells do not secrete detectable levels of sphingosine, suggesting that the secreted S1P is indeed formed intracellularly and not extracellularly as has been suggested for other cell types (17).

Figure 1.

FcɛRI cross-linking stimulates SphK and increases S1P. BMMCs (A) and RBL-2H3 cells (B and C) were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE and treated with DNP-HSA as described in Materials and Methods. At the indicated times, cells were lysed, and SphK activity was measured in the presence of 0.25% Triton X-100. Data are presented as fold increase ± SD. SphK activity in unstimulated BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells were 1.5 ± 0.4 and 3.4 ± 0.4 pmol/min/mg, respectively. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (C) Mast cells secrete S1P. RBL-2H3 cells were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE, washed, and treated with DNP-HSA in serum-free medium containing 4 mg/ml BSA. Mass levels of S1P in RBL-2H3 cells (closed symbols) and media (open symbols) were measured at the indicated times. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (D and E) Expression of SphKs and S1PRs in mast cells. (D) RT-PCR analysis of expression of SphKs and S1PRs. Anti-DNP IgE-sensitized BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated without or with DNP-HSA (Ag). After 1 h at 37°C, RNA was extracted and SphKs, S1PRs, and glyceraldehyde-3–phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNAs were determined by RT-PCR. No PCR products were detected in the absence of RT. (E) IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells were treated with Ag for the indicated times, and cell lysates were examined by Western blotting with anti-S1P2 or anti-S1P1 (Exalpha) and subsequently with antitubulin antibody to show equal loading as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Expression of SphKs and S1PRs in Mast Cells.

Recently, two distinct isoforms of SphK, designated SphK1 and SphK2, have been cloned and characterized (12, 18). Although human BMMCs have been reported to express only SphK1 (5), murine BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells express both SphK1 and SphK2 (Fig. 1 D). There were no significant changes in their mRNA expressions after FcɛRI cross-linking, supporting the notion that SphK activity is increased by posttranslational events.

Previous papers demonstrated that FcɛRI cross-linking leads to activation of SphK and formation of S1P, which acts intracellularly to mobilize calcium from intracellular stores by an InsP3-independent pathway (2, 5). However, the best characterized actions of S1P are as an extracellular ligand for the S1PRs (6). Although the five S1PRs are ubiquitously expressed, their expression in mast cells has not been examined previously. RT-PCR analysis of untreated BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells revealed that S1P1 and S1P2 were expressed (Fig. 1 D), but not S1P3, S1P4, or S1P5 (unpublished data). Interestingly, S1P2 expression in both BMMCs and RBL-2H3 cells was increased after FcɛRI cross-linking (Fig. 1 D). The presence of S1P1 and S1P2 proteins was also examined with specific antibodies in crude membrane fractions of RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 1 E). In agreement with mRNA analysis, levels of S1P2 but not S1P1 were increased after cross-linking of FcɛRI with Ag (Fig. 1 E).

The Role of S1P in Mast Cell Chemokine and Cytokine Expression.

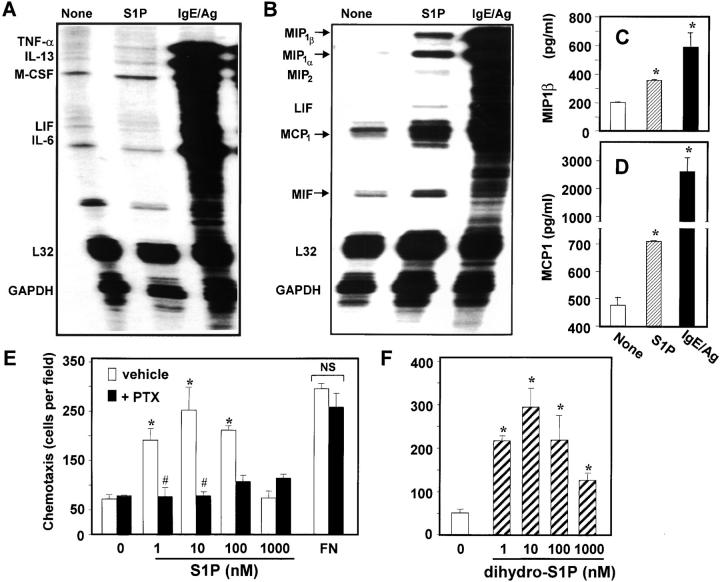

Activated mast cells produce and secrete cytokines and chemokines capable of modulating immune responses (19). S1P stimulated leukotriene synthesis in CPII mast cells (4) and induced release of Th2 cytokines from mature dendritic cells (9). Because RBL-2H3 cells secrete S1P, we examined its effects on cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression profiles. S1P had no significant effects on cytokines (Fig. 2 A), yet it markedly increased expression of the chemokines (Fig. 2 B), although much less potently than IgE/Ag. Expression of MCP-1, MIP1-α, MIP1-β, MIP2 (belonging to the CC-chemokine family), and MIF, all important modulators of monocyte and eosinophil recruitment and inflammation, were significantly increased by S1P. In agreement with the RPA profile, secretion of both MIP-1β (Fig. 2 C) and MCP-1 (Fig. 2 D) determined by ELISA was significantly increased by S1P, albeit less potently than IgE/Ag.

Figure 2.

S1P increases synthesis of proinflammatory chemokines. BMMCs were treated without (None) or with 100 nM S1P or IgE/Ag for 1 h, and total RNA was extracted. mRNA expression of the indicated cytokines (A) or chemokines (B), and L32 and GAPDH controls were determined by RPA. (C and D) BMMCs were stimulated with S1P or IgE/Ag for 4 h, and the secretion of MIP-1β (C) and MCP-1 (D) was measured by ELISA. *, P < 0.001 by Student's t test. (E and F) Chemotaxis of mast cells toward S1P. RBL-2H3 cells were allowed to migrate toward 20 μg/ml fibronectin (FN) or the indicated concentrations of S1P (E) or dihydro-S1P (F) for 2 h. Where indicated, cells were pretreated for 12 h with 200 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX). The data are mean ± SD of three individual wells. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. #, P < 0.05 by ANOVA. NS, not significant. Note that PTX had no effect on chemotaxis toward fibronectin.

S1P Stimulates Migration of Mast Cells.

Because S1P induces chemotaxis of many types of cells (6), it was of interest to determine whether movement of mast cells is also regulated by S1P. Using a modified Boyden chamber assay, we found that chemotaxis of RBL-2H3 cells was markedly stimulated by S1P, even at concentrations as low as 1 nM and showed a maximum response at a concentration of 10 nM (Fig. 2 E). These extremely low concentrations of S1P suggest the involvement of a S1PR. Moreover, pertussis toxin (PTX) ablated migration toward S1P, implicating a Gi-dependent pathway. Yet, as expected, migration toward fibronectin was not altered by PTX. To confirm that S1P-induced migration was mediated by binding to S1PRs, we used the S1P mimetic sphinganine-1–phosphate (dihydro-S1P), which has no known intracellular effects, but is able to bind to and signal through all of the S1PRs (6). RBL-2H3 cells migrated toward dihydro-S1P with very similar concentration-dependent effects as S1P (Fig. 2 F).

Cell migration is a complex process involving reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and formation of lamellipodia and/or filopodia at the leading edge. Because S1P1 is emerging as a critical component of migratory responses to S1P (6), we examined its role in mast cell cytoskeleton rearrangements. As with other GPCRs, GFP tagging of S1PRs has been extensively used to study receptor internalization after activation (6, 20). Moreover, we found previously that S1P1-GFP transduces intracellular signals in a manner indistinguishable from that of the wild-type receptor (20). S1P1-GFP was expressed mainly on the plasma membrane of RBL-2H3 cells with minimal membrane ruffling, and F-actin was localized to the cell cortex (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1). As expected, addition of S1P caused internalization of S1P1-GFP (Fig. S1 B). In addition, S1P induced dramatic remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton such that the cortical actin redistributed in protrusion-like structures reminiscent of lamellipodia, which were prominent in S1P1-transfected cells (Fig. S1 B).

FcɛRI Cross-linking Stimulates and Translocates SphK1, Not SphK2.

Previous studies with human BMMCs have shown that SphK1 is primarily cytosolic and is rapidly translocated to the plasma membrane after aggregation of FcɛRI (5). In agreement, confocal microscopy revealed that GFP-SphK1 is diffusely distributed in the cytosol of unstimulated RBL-2H3 cells and FcɛRI cross-linking induced its translocation within 1 min from the cytosol to the plasma membranes where its substrate sphingosine resides (Fig. S2 A, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1). Similarly, by immunoblotting analysis, GFP-SphK1 was expressed predominantly in the cytosol and was rapidly translocated to membrane fractions upon aggregation of FcɛRI (Fig. S2 B). In contrast, no translocation of GFP vector or GFP-SphK2 to the plasma membrane was detected (Fig. S2). Because mast cells express both SphK1 and SphK2 (Fig. 1 D), it was of interest to determine which of the endogenous isoforms is being activated by IgE cross-linking. SphK1 can be distinguished from SphK2 on the basis of differential activity measured when the substrate sphingosine is added as a BSA complex in the presence of high salt or in a micellar form with Triton X-100 (12). Although Triton X-100 stimulates SphK1 and strongly inhibits SphK2, high salt is optimal for SphK2 and drastically inhibits SphK1 (12, 21). IgE/Ag induced >10-fold increase in membrane-associated SphK activity measured in the presence of Triton X-100 (Fig. S3 A, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1), which was not evident when the activity was measured in the presence of high salt without Triton (Fig. S3 B), suggesting that only SphK1 is activated by IgE triggering. To further confirm this notion, we examined the effect of FcɛRI cross-linking on RBL-2H3 cells transfected with SphK1 and SphK2. Overexpression of SphK1 increased SphK activity from 6 ± 2 to 568 ± 32 pmol/min/mg (∼100-fold), whereas overexpression of SphK2 only increased activity to 100 ± 10 pmol/min/mg (∼15-fold), in agreement with previous observations that high levels of SphK2 are detrimental (22). IgE/Ag markedly activated overexpressed SphK1 by more than fivefold but did not stimulate overexpressed SphK2 (Fig. S3, C and D). Together, these results suggest that FcɛRI triggering activates and translocates SphK1 to mast cell membranes resulting in increased formation and subsequent secretion of S1P.

FcɛRI Cross-linking Transactivates S1P1 and S1P2.

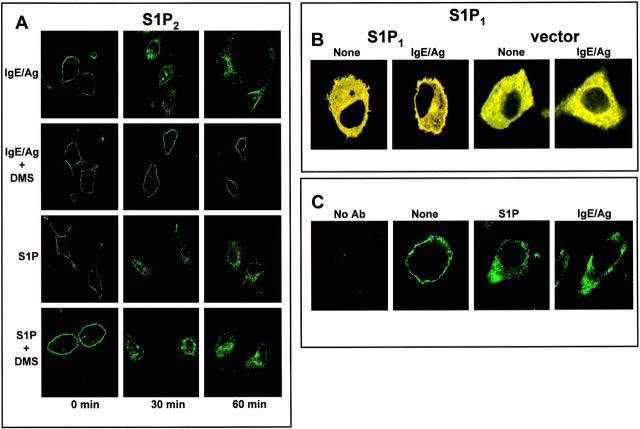

As S1P is secreted by mast cells upon FcɛRI cross-linking, it was important to determine whether this S1P could in turn activate S1PRs. S1P, like other ligands for GPCRs, induces internalization of S1PRs upon ligation and activation (Fig. S1 D). S1P2 similar to S1P1 is localized on the cell surface of unstimulated RBL-2H3 cells transfected with GFP fusion proteins (Fig. 3 A). Remarkably, IgE/Ag induced internalization of both S1P1 and S1P2 similar to exogenous S1P (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S4, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20030680/DC1). β-Arrestins are cytosolic adaptor proteins that bind with high affinity to agonist-activated, phosphorylated GPCRs, and their translocation to plasma membranes has been used to examine activation of various overexpressed receptors (23), including S1P1 (16). In agreement with the observation of S1PR internalization, FcɛRI cross-linking promoted rapid redistribution of β-arrestin2 tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane only in S1P1-expressing RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 3 B). The lack of such translocation in vector-transfected cells (Fig. 3 B) suggests that expression of S1P1 was required for this translocation and excludes the possibility that β-arrestin2 recruitment to the plasma membrane was caused by activation of unrelated GPCRs. These results further support the notion that IgE cross-linking stimulates production of the ligand for S1P1.

Figure 3.

FcɛRI cross-linking–induced internalization of S1P1 and S1P2. RBL-2H3 cells transfected with S1P2-GFP (A) were treated with 100 nM S1P or sensitized with IgE and treated with 100 ng/ml DNP-HSA (Ag) for the indicated times, fixed, and examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. Where indicated, cells were pretreated with 10 μM DMS for 20 min before addition of Ag. Representative cells from >100 examined. (B) Translocation of β-arrestin. RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing S1P1 or vector were transfected with β-arrestin2–YFP and plated on glass coverslips. The next day, cells were serum starved for 12 h and treated for 5 min with Ag. YFP fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy with the 514 nm argon laser. (C) Internalization of endogenous S1P1 by S1P and FcɛRI cross-linking. RBL-2H3 cells were treated with vehicle, 100 nM S1P, or 100 ng/ml DNP-HSA (Ag) for 60 min, fixed, incubated with S1P1 antibody (1:100), and examined by confocal microscopy after staining with Cy2-conjugated secondary antibody. Representative results from >30 cells were examined. No fluorescence was detected when the primary antibody was omitted, when the S1P1 antibody was preincubated with the peptide antigen, or in the absence of S1P1 expression.

To confirm that internalization of S1P1 and S1P2 induced by FcɛRI triggering was due to activation of SphK and the release of newly generated S1P, mast cells were pretreated with the specific SphK inhibitor N,N-dimethylsphingosine (DMS). DMS almost completely prevented internalization of S1P1 or S1P2 induced by FcɛRI cross-linking, but not by S1P (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S4), indicating that activation of SphK and production of S1P is a necessary event in transactivation of these S1PRs.

Although epitope-tagged S1P1 has been used extensively to study internalization and signaling upon ligation of S1P (20, 24) and functions in an analogous manner as the endogenous receptor (20), overexpression may not exactly reproduce the physiological distribution of endogenous receptors. Thus, we examined next whether endogenous S1P1 is also activated by its ligand produced by IgE/Ag triggering. In untreated cells, endogenous S1P1, visualized with a specific antibody, was prominently localized on the plasma membrane, as expected of unstimulated GPCRs, and internalized after treatment with exogenous S1P (Fig. 3 C). Moreover, FcɛRI aggregation also induced internalization of the endogenously expressed S1P1. Collectively, these results suggest that IgE triggering stimulates production of S1P, which transactivates S1P1 on the cell surface.

S1P2 Is Critical for IgE/Ag-induced Degranulation.

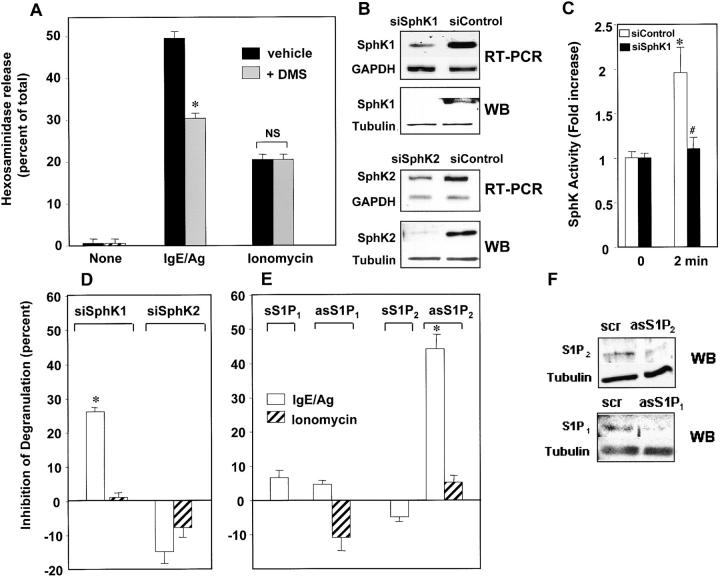

In agreement with a previous paper demonstrating that S1P induced degranulation of CPII mast cells (4), we found that S1P induces degranulation of BMMCs as determined by β-hexosaminidase release, albeit to a lesser extent than IgE/Ag (Fig. 4 A). It was of interest to investigate the possibility that S1P generated in response to IgE triggering might contribute to mast cell activation. To this end, we used DMS, which effectively inhibits SphK1 (18) and SphK2 (12) and has no effect on protein kinase C (25) or other signaling pathways (26). Treatment of BMMCs with DMS markedly reduced degranulation induced by FcɛRI cross-linking (Fig. 4 A). There was a close correlation between the dose-dependent inhibition of degranulation by DMS (IC50 ≈ 5 μM; unpublished data) and the known Ki for inhibition of SphK1 and SphK2 of 4 and 12 μM, respectively (12, 18). Moreover, in agreement with its inability to interfere with binding of S1P to its receptors (27), DMS did not significantly affect degranulation induced by exogenous S1P (Fig. 4 A).

Figure 4.

Role of S1P formation in degranulation of mast cells. (A and B) BMMCs were treated with vehicle, S1P, or anti-DNP IgE and DNP-HSA (IgE/Ag), and hexosaminidase release was determined. Where indicated, cells were pretreated with 10 μM N,N-dimethylsphingosine (DMS) or 10 μM d,l-threo-dihydrosphingosine (DHS) for 20 min or with 200 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX) for 2 h before stimulation. Data are expressed as percent of the total cellular amount after subtraction of spontaneous release, which was always <5%, and are means ± SD. *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01 by Student's t test. NS, not significant. (C and D) S1P2 deficiency markedly reduces mast cell degranulation. (C) IgE-sensitized wild-type BMMCs (white bars) and S1P2 −/− BMMC (black bars) were stimulated for 20 min with 10 and 30 ng/ml Ag or ATP (1 mM), and degranulation was determined as percentage of total hexosaminidase. (D) IgE-sensitized wild type (open symbols) and S1P2 −/− (closed symbols) BMMCs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml Ag for the indicated times, and degranulation was determined. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. #, P < 0.05 by ANOVA. NS, not significant.

These results suggest that S1P produced by FcɛRI triggering could play a role in mast cell activation by binding to its receptors, S1P1 or S1P2, present on mast cells. Because S1P1 is coupled solely to Gi (6), cells were pretreated with PTX to inactivate Gi. The inhibitory effect of PTX was lower than the inhibitory effects of DMS or d,l-threo-dihydrosphingosine, another SphK inhibitor (Fig. 4 B).

Because the other mast cell S1P receptor, S1P2, can couple to many G proteins, next we examined degranulation responses in BMMCs derived from S1P2 −/− mice, which develop normally. We found that degranulation in these cells was significantly impaired when compared with wild-type BMMCs in response to FcɛRI cross-linking (Fig. 4, C and D). The dramatic reduction of almost 50% was observed at several concentrations of Ag. This defect is not a reflection of a developmental defect in maturation of the secretory compartment because total granule content and kinetics of degranulation (Fig. 4 D) were the same as in wild-type cells. However, we noted that degranulation induced by ATP was also significantly reduced in S1P2 null BMMCs (Fig. 4 C). This might reflect the possible need to transactivate S1P2 by purinergic receptors. Alternatively, the loss of S1P2 during development might alter expression of signaling proteins that contribute to mast cell degranulation.

To confirm and extend the involvement of SphK1 and S1P and its receptors in degranulation, similar experiments were performed with RBL-2H3 cells. DMS, at a concentration that effectively inhibited SphK1 and S1P production, markedly blocked hexosaminidase release in IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells, but did not affect ionomycin-induced degranulation (Fig. 5 A). We also used a molecular approach to decrease SphK1 expression in fully developed cells by siRNA targeted to SphK1. siSphK1 not only markedly reduced SphK1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5 B), it blocked IgE-stimulated SphK activity (Fig. 5 C), supporting the conclusion that SphK1 is the isoenzyme activated by IgE. In agreement with the SphK inhibitor results, transfection of RBL-2H3 cells with siSphK1 markedly inhibited Ag-induced degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 5 D), whereas transfection with control siRNA had no effect, and siRNA targeted to SphK2 slightly increased degranulation. In agreement with the lack of effect of DMS on degranulation induced by calcium ionophore, siSphK1 did not influence ionomycin-induced degranulation (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Role of SphKs and S1PRs in antigen-induced degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells. (A) RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated with IgE/Ag or ionomycin (1 μM) for 30 min in the absence or presence of pretreatment with 10 μM DMS, and hexosaminidase release was determined. *, P < 0.01 by Student's t test. NS, not significant. (B–D) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with control siRNA or siRNAs specific to SphK1 or SphK2 for 48 h. Cells were lysed, and mRNA and proteins were analyzed by RT-PCR or Western blotting (WB) with SphK-specific antibodies as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. (C) SphK activity was measured in membrane fractions of IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells after stimulation with Ag for 2 min. (D) In duplicate cultures, degranulation by IgE/Ag (white bars) or ionomycin (diagonally striped bars) was measured. Data are expressed as percent inhibition of degranulation relative to control siRNA. (E and F) RBL-2H3 cells were transfected with S1P1 or S1P2 antisense (as), sense (s), or scrambled (scr) oligonucleotides for 48 h and stimulated with IgE/Ag or ionomycin for 60 min, and degranulation was measured. Data are expressed as percent inhibition of degranulation relative to scrambled controls. (F) Representative Western blots showing reduction of S1P1 and S1P2 protein expression by antisense oligonucleotides as determined with specific antibodies are shown. Blots were stripped and probed with antitubulin to show equal loading. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. NS, not significant.

To further confirm the role of S1PRs in IgE-induced degranulation, S1P1 and S1P2 expression in RBL-2H3 cells was down-regulated with specific antisense RNA (Fig. 5 F), similar to previous analyses in other cell types (15, 16). Antisense, but not sense, oligonucleotides for S1P2 specifically inhibited IgE-induced degranulation, but did not affect ionomycin-induced degranulation (Fig. 5 E). In contrast, neither sense nor antisense S1P1 had any effect on hexosaminidase release induced by IgE cross-linking (Fig. 5 E), suggesting that S1P2 and not S1P1 is involved in degranulation.

SphK and S1P1 Are Required for Migration of Mast Cells toward Ag.

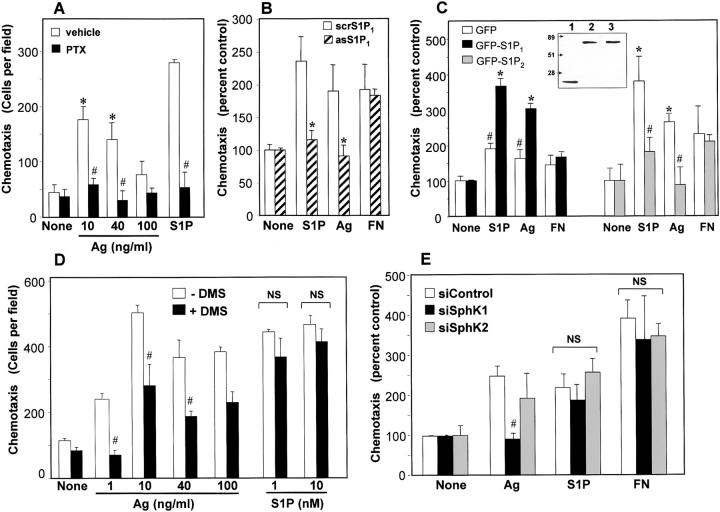

Although it has long been appreciated that asthmatics have more mast cells in their pulmonary tissue than nonasthmatics, how these mast cells arrive at inflammatory sites in the lung is not known. Given that IgE triggering can transactivate S1PRs, and S1PRs are known to regulate cell movement (6), next we examined their roles in motility of mast cells. A recent paper suggested that Ag is not only a stimulant of allergic mediators release by IgE-sensitized MC-9 mast cells, it is also a chemotactic factor (28). In agreement, RBL-2H3 cells also migrated toward Ag in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A). Interestingly, not only was chemotaxis toward S1P blocked by PTX, Ag-induced migration was completely inhibited by PTX (Fig. 6 A), suggesting the involvement of a Gi-mediated signaling pathway in migration of mast cells toward Ag. In concordance, down-regulation of S1P1, which is coupled solely to Gi, abrogated migration toward Ag (Fig. 6 B), although it did not affect Ag-induced degranulation (Fig. 5 E). This was not a general effect on motility because migration toward fibronectin was not affected (Fig. 6 B). Moreover, overexpression of S1P1 increased random motility or chemokinesis, probably due to constitutive activation of S1P1 receptors as has been found for many GPCRs (20). Nevertheless, overexpression of S1P1 significantly enhanced chemotaxis toward both S1P and Ag (Fig. 6 C). In contrast to S1P1, the other S1P receptor expressed on mast cells, S1P2, is a repellant receptor that inhibits migration in diverse cell types (29). Similarly, overexpression of S1P2 in mast cells significantly impaired migration toward S1P and Ag, but not fibronectin (Fig. 6 C).

Figure 6.

Chemotaxis of mast cells toward Ag is dependent on SphK1, Gi, and S1P1. (A) RBL-2H3 cells were sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-DNP IgE in the absence (white bars) or presence of 200 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX, black bars) and allowed to migrate toward the indicated concentrations of Ag or S1P (1 nM) for 3 h. (B) RBL-2H3 cells were transfected with S1P1 antisense (diagonally striped bars) or scrambled oligonucleotides (white bars) for 48 h, sensitized with anti-DNP IgE, and allowed to migrate toward 10 nM S1P, 10 ng/ml Ag, or 20 μg/ml fibronectin. (C) RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing GFP-S1P1 (black bars) or GFP-vector (white bars) were sensitized with anti-DNP IgE and allowed to migrate for 1.5 h toward 10 nM S1P, 10 ng/ml Ag, or 20 μg/ml fibronectin. Random motilities of vector and S1P1 transfectants were 82 ± 11 and 219 ± 6, respectively. RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing GFP-S1P2 (gray bars) or GFP-vector (white bars) were allowed to migrate toward the same agents for 3 h. Random motilities of vector and S1P2 transfectants were 157 ± 9 and 174 ± 29, respectively. (inset) Western blot of cell lysates showing expression of GFP-S1P1 and GFP-S1P2 visualized by ECL with anti-GFP. Lanes 1, 2, and 3 are lysates of cells overexpressing GFP vector, GFP-S1P1, and GFP-S1P2, respectively. (D) IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells were treated without (white bars) or with 1 μM DMS (black bars) for 20 min before the addition of the indicated concentrations of Ag or S1P. (E) RBL-2H3 cells were transfected with control siRNA (white bars), siRNA targeted to SphK1 (black bars), or siRNA targeted to SphK2 (gray bars) as described in Materials and Methods, sensitized with 1 μg/ml anti-DNP IgE for 6 h, and allowed to migrate toward vehicle (None), 10 ng/ml Ag, 10 nM S1P, or 20 μg/ml fibronectin for 3 h. Results are expressed as means ± SD. *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. #, P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

Next, we examined the involvement of SphK1 in Ag-directed motility. Treatment of RBL 2H3 cells with the SphK inhibitor DMS blocked chemotaxis toward Ag at optimal and even higher concentrations of Ag (Fig. 6 D), without affecting S1P-induced chemotaxis (Fig. 6 D). In agreement, down-regulation of SphK1 expression completely blocked chemotaxis of RBL-2H3 cells toward Ag (Fig. 6 E), whereas transfection with control siRNA or siSphK2 had no effect. Importantly, SphK1-targeted siRNA did not inhibit chemotaxis toward S1P or fibronectin (Fig. 6 E). These results confirm that chemotaxis of mast cells toward Ag requires FcɛRI-triggered activation of SphK1 and formation of S1P, which in turn activates S1P1 and downstream signals important for motility.

Discussion

In RBL-2H3 mast cells, FcɛRI cross-linking stimulates SphK to generate S1P, which has been proposed to function intracellularly independent of InsP3 to mobilize calcium (2), a crucial event for mast cell function. In agreement, down-regulation of SphK1 expression demonstrated that IgE/Ag stimulation of SphK1 mediated fast and transient calcium release from intracellular stores in human BMMCs (5). In contrast, PLCγ1 induced a second slower wave of calcium release from intracellular stores leading to calcium influx (5). Interestingly, calcium responses in mast cells induced by S1P are sensitive to PTX and, therefore, mediated by a Gi-coupled receptor (3), whereas in contrast, FcɛRI-dependent calcium release is clearly PTX insensitive (3, 30). It has also been suggested that the decisive balance between sphingosine, the substrate for SphK, and S1P determines the allergic responsiveness of mast cells (4, 31). Although sphingosine acts as a potent inhibitor of IgE-triggered leukotriene synthesis and cytokine production, S1P counteracts the inhibitory effects of sphingosine (4). Moreover, sphingosine blocks the store-operated calcium release–activated calcium current (ICRAC) in RBL-2H3 cells (32). Hence, it was suggested that in the resting state, sphingosine could act as a blocker of ICRAC and upon depletion of internal stores, conversion of sphingosine to S1P catalyzed by SphK lowers sphingosine levels and would lead to dysinhibition of ICRAC (32).

A shortcoming of all of the previous studies is that they did not consider the possibility that S1P might also act by binding to a specific cell surface receptor. Similar to a previous analysis with human BMMCs (5), we found that FcɛRI cross-linking stimulates and translocates SphK1 to the plasma membrane of mast cells, but not the other isoform, SphK2. However, in contrast with the suggestion that S1P formed by activation of SphK in mast cells acts intracellularly (2, 5), our data indicate that this S1P also regulates important mast cell functions in an autocrine manner by binding to its receptors, S1P1 and S1P2, present on the cell surface. Several lines of evidence support the notion that FcɛRI cross-linking transactivates these S1PRs. First, S1P is secreted upon mast cell activation. Second, FcɛRI triggering induced activation and internalization of S1P1 and S1P2, a S1P-dependent process that was blocked by a specific inhibitor of SphK. Third, inhibition of mast cell SphK1 by pharmacological or molecular approaches drastically reduced their migration toward Ag. Moreover, PTX, which inactivates Gi, also blocked Ag-directed motility as well as mobility toward S1P, suggesting the involvement of Gi-coupled S1P1. In agreement, down-regulation of S1P1 reduced migration toward Ag. Finally, deletion of s1p2 or reduction of its expression severely impaired degranulation induced by IgE/Ag.

Previously, we have suggested a similar mechanism for crosstalk between the tyrosine kinase receptor PDGFR and S1PRs such as S1P1 (16). However, others have questioned the generality of this concept (33). For example, the tyrosine kinase receptor for IGF-1 activates S1P1 by Akt-dependent phosphorylation in a manner that does not require the SphK pathway (34). In another example, PDGFR and S1P1 were shown to form a complex that was cointernalized by PDGF as a functional signaling unit to regulate the ERK1/2 pathway (35). The results of these studies suggest ligand-independent activation of S1P1 and imply that activation of SphK1 and intracellular generation of S1P are not important for receptor crosstalk. In contrast, our data obtained after cross-linking of the IgE receptor strongly support the participation of SphK1 and formation of S1P, which in turn, in an autocrine and/or paracrine fashion, stimulates S1P1 or S1P2, leading to amplification of downstream signals important for mast cell activation, particularly those related to movement or degranulation. There are some precedents for similar mast cell autocrine amplification loops. For example, the release of preformed mast cell–associated TNF-α acts as a positive autocrine feedback signal to augment nuclear factor κB activation and production of further cytokines, including GM-CSF and IL-8 (36). In addition, human mast cells express the enzymes that catalyze the committed step in the biosynthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes and their cognate receptors, suggesting that these lipid mediators may be involved in autocrine signaling pathways regulating mast cell functions (37). Indeed, a recent paper demonstrates an autocrine amplification mechanism via the cysteinyl-leukotriene receptor for production of IL-5 and TNF-α in response to IgE receptor cross-linking (38).

Although it is well known that asthmatics have higher numbers of mast cells in their pulmonary mucosa (1), it is not clear how mast cells arrive at these sites. It was found previously that migration of MC9 mast cells toward antigen did not require polypeptide chemotactic factors produced by the cells themselves (28). Our observations that FcɛRI triggering induced RBL-2H3 cells to produce and secrete S1P, as well as the exquisite ability of mast cells to migrate toward vanishingly small concentrations of S1P (1 nM), prompted us to examine the involvement of S1PRs in antigen-induced chemotaxis of mast cells. The fact that PTX completely blocked migration not only toward S1P but also toward Ag implicated a Gi-mediated pathway and suggested that activation of S1P1 might be critical for Ag-induced chemotaxis. If so, inhibition of SphK1, which prevents formation of S1P and activation of its receptors, should block migration of mast cells toward Ag. Indeed, inhibition of SphK1 in mast cells by specific inhibitors or siRNA drastically reduced chemotaxis toward Ag. In sharp contrast, motility toward S1P was not affected, demonstrating that the loss of S1P formation was the cause of decreased migration toward Ag.

Of particular interest, significant mast cell migration toward Ag was observed at 1 ng/ml, a concentration that was much lower than that required for optimal FcɛRI-triggered degranulation (100 ng/ml). Thus, a compelling in vivo scenario is that a gradient of antigen attracts mast cells. When they reach areas of higher Ag concentration, this causes them to stop moving and induces them to release their contents. Our finding that FcɛRI cross-linking increased S1P2 expression, which we showed inhibited migration of RBL-2H3 cells toward both S1P and Ag when overexpressed, is consistent with this hypothesis. Thus, the dynamic balance between S1P1 and S1P2 expression and signaling after their transactivation by FcɛRI cross-linking could regulate mast cell migration toward antigen. Furthermore, antagonistic actions of S1P1 and S1P2 on cell movement have been previously correlated with their opposing effects on activation of the small GTPases Rho and Rac, important for cell motility. Although S1P1 stimulated Rac-coupled cortical actin formation (16, 34) and cell migration, activation of S1P2 elicited Rho-coupled stress fiber assembly as well as negatively regulating Rac activity (39), thereby inhibiting cell migration.

The net effects of S1P are determined by both the expression profile of the various S1P receptors and by the activity of the intracellular pathways to which they are coupled. We envision that this contributes to the ability of mast cells to modulate their responses in both a temporal and spatial manner. The studies reported here provide the basis for a model whereby an S1P autocrine loop activating opposing signaling of S1P1 and S1P2 might orchestrate recruitment of mast cells to sites of inflammation. Moreover, early in an inflammatory process, S1P produced by mast cells can lead to heightened production of chemokines, necessary for the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as monocytes and eosinophils. We have shown previously that weak stimulation of mast cells with Ag preferentially elicited chemokines (13) and, thus, it is of interest whether this response to Ag is mediated by S1P production. Altered expression or activity of the various S1P receptors on the mast cells, with a shift from Gαi-coupled S1P1 to Gαq- and Gα12/13-linked S1P2 would be reversed upon restoration of homeostasis as the inflammation is resolved.

Mast cell degranulation is dependent on increased intracellular calcium, activation of protein kinase C, and changes in the actin cytoskeleton regulated by Rho family GTPases (40). Interestingly, deletion of S1P2, which has been linked to all of these signaling pathways, significantly decreased degranulation of mast cells induced by IgE/Ag. In contrast to BMMCs from Vav knockout mice, where decreased hexosaminidase release resulted from slower kinetics (41), the kinetics of hexosaminidase release were similar in wild type and S1P2 null BMMCs, though the extent of release was lower in the latter. These results imply that transactivation of S1P2 may play an important role downstream of FcɛRI in mast cell degranulation.

Together with the previous observation that S1P levels were significantly elevated in the asthmatic lung after challenge with an allergen (8), S1P and its receptors have the ability to augment the allergic response on a broad scale not only in mast cell activation as shown by our results but also in activation of airway smooth muscle cells (8, 42), monocytes (43), neutrophils (44), and endothelial cells (14, 15, 45), as well as by enhancing lymphocyte infiltration (46). Thus, this paper highlights new potential therapeutic directions for treatment of asthma and other inflammatory disorders aimed at decreasing S1P production or antagonizing the actions of specific S1P receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. L. Barak for providing β-arrestin2 GFP, Dr. Y. Igarashi for providing anti-SphK1 antibody, and Dr. S. Goparaju for preparation of SphK antibodies.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AIS0094 to S. Spiegel. Flow cytometry was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant P30 CA16059.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMMC, bone marrow–derived mast cell; dihydro-S1P, S1P mimetic sphinganine-1–phosphate; DMS, N,N-dimethylsphingosine; EMEM, Eagle's minimal essential medium; FcɛRI, high-affinity receptor for IgE; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; ICRAC, calcium release–activated calcium current; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; MIP1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1; PTX, pertussis toxin; RPA, ribonuclease protection assay; S1P, sphingosine-1–phosphate; si, small interfering; SphK, sphingosine kinase; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1.Brightling, C.E., P. Bradding, F.A. Symon, S.T. Holgate, A.J. Wardlaw, and I.D. Pavord. 2002. Mast-cell infiltration of airway smooth muscle in asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1699–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi, O.H., J.-H. Kim, and J.-P. Kinet. 1996. Calcium mobilization via sphingosine kinase in signalling by the FcɛRI antigen receptor. Nature. 380:634–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinet, J.P. 1999. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:931–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prieschl, E.E., R. Csonga, V. Novotny, G.E. Kikuchi, and T. Baumruker. 1999. The balance between sphingosine and sphingosine-1–phosphate is decisive for mast cell activation after Fc epsilon receptor I triggering. J. Exp. Med. 190:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melendez, A.J., and A.K. Khaw. 2002. Dichotomy of Ca2+ signals triggered by different phospholipid pathways in antigen stimulation of human mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17255–17262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel, S., and S. Milstien. 2003. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matloubian, M., C.G. Lo, G. Cinamon, M.J. Lesneski, Y. Xu, V. Brinkmann, M.L. Allende, R.L. Proia, and J.G. Cyster. 2004. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 427:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammit, A.J., A.T. Hastie, L.C. Edsall, R.K. Hoffman, Y. Amrani, V.P. Krymskaya, S.A. Kane, S.P. Peters, R.B. Penn, S. Spiegel, and R.A. Panettieri, Jr. 2001. Sphingosine 1-phosphate modulates human airway smooth muscle cell functions that promote inflammation and airway remodeling in asthma. FASEB J. 15:1212–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idzko, M., E. Panther, S. Corinti, A. Morelli, D. Ferrari, Y. Herouy, S. Dichmann, M. Mockenhaupt, P. Gebicke-Haerter, F. Di Virgilio, et al. 2002. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces chemotaxis of immature and modulates cytokine-release in mature human dendritic cells for emergence of Th2 immune responses. FASEB J. 16:625–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitoh, S., R. Arudchandran, T.S. Manetz, W. Zhang, C.L. Sommers, P.E. Love, J. Rivera, and L.E. Samelson. 2000. LAT is essential for Fc(epsilon)RI-mediated mast cell activation. Immunity. 12:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edsall, L.C., and S. Spiegel. 1999. Enzymatic measurement of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Anal. Biochem. 272:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, H., M. Sugiura, V.E. Nava, L.C. Edsall, K. Kono, S. Poulton, S. Milstien, T. Kohama, and S. Spiegel. 2000. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel mammalian sphingosine kinase type 2 isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19513–19520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Espinosa, C., S. Odom, A. Olivera, J.P. Hobson, M.E.C. Martinez, A. Oliveira-dos-Santos, L. Barra, S. Spiegel, J.M. Penninger, and J. Rivera. 2003. Preferential signaling and induction of allergy-promoting lymphokines upon weak stimulation of the high affinity IgE receptor on mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 197:1453–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, F., J.R. Van Brocklyn, J.P. Hobson, S. Movafagh, Z. Zukowska-Grojec, S. Milstien, and S. Spiegel. 1999. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates cell migration through a G(i)-coupled cell surface receptor. Potential involvement in angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35343–35350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, M.J., S. Thangada, K.P. Claffey, N. Ancellin, C.H. Liu, M. Kluk, M. Volpi, R.I. Sha'afi, and T. Hla. 1999. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 99:301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobson, J.P., H.M. Rosenfeldt, L.S. Barak, A. Olivera, S. Poulton, M.G. Caron, S. Milstien, and S. Spiegel. 2001. Role of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG-1 in PDGF-induced cell motility. Science. 291:1800–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ancellin, N., C. Colmont, J. Su, Q. Li, N. Mittereder, S.S. Chae, S. Steffansson, G. Liau, and T. Hla. 2002. Extracellular export of sphingosine kinase-1 enzyme: Sphingosine 1-phosphate generation and the induction of angiogenic vascular maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6667–6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohama, T., A. Olivera, L. Edsall, M.M. Nagiec, R. Dickson, and S. Spiegel. 1998. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine sphingosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23722–23728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burd, P.R., H.W. Rogers, J.R. Gordon, C.A. Martin, S. Jayaraman, S.D. Wilson, A.M. Dvorak, S.J. Galli, and M.E. Dorf. 1989. Interleukin 3–dependent and –independent mast cells stimulated with IgE and antigen express multiple cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 170:245–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, C.H., S. Thangada, M.J. Lee, J.R. Van Brocklyn, S. Spiegel, and T. Hla. 1999. Ligand-induced trafficking of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG-1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10:1179–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billich, A., F. Bornancin, P. Devay, D. Mechtcheriakova, N. Urtz, and T. Baumruker. 2003. Phosphorylation of the imunomodulatory drug FTY720 by sphingosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278:47408–47415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, H., R.E. Toman, S. Goparaju, M. Maceyka, V.E. Nava, H. Sankala, S.G. Payne, M. Bektas, I. Ishii, J. Chun, et al. 2003. Sphingosine kinase type 2 is a putative BH3-only protein that induces apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:40330–40336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claing, A., S.A. Laporte, M.G. Caron, and R.J. Lefkowitz. 2002. Endocytosis of G protein-coupled receptors: roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and beta-arrestin proteins. Prog. Neurobiol. 66:61–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohno, T., A. Wada, and Y. Igarashi. 2002. N-glycans of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor Edg-1 regulate ligand-induced receptor internalization. FASEB J. 16:983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edsall, L.C., J.R. Van Brocklyn, O. Cuvillier, B. Kleuser, and S. Spiegel. 1998. N,N-Dimethylsphingosine is a potent competitive inhibitor of sphingosine kinase but not of protein kinase C: modulation of cellular levels of sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide. Biochemistry. 37:12892–12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alemany, R., D. Meyer zu Heringdorf, C.J. van Koppen, and K.H. Jakobs. 1999. Formyl peptide receptor signaling in HL-60 cells through sphingosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3994-3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Brocklyn, J.R., M.J. Lee, R. Menzeleev, A. Olivera, L. Edsall, O. Cuvillier, D.M. Thomas, P.J.P. Coopman, S. Thangada, T. Hla, and S. Spiegel. 1998. Dual actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate: extracellular through the Gi-coupled orphan receptor edg-1 and intracellular to regulate proliferation and survival. J. Cell Biol. 142:229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishizuka, T., F. Okajima, M. Ishiwara, K. Iizuka, I. Ichimonji, T. Kawata, H. Tsukagoshi, K. Dobashi, T. Nakazawa, and M. Mori. 2001. Sensitized mast cells migrate toward the antigen: a response regulated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and Rho-associated coiled-coil-forming protein kinase. J. Immunol. 167:2298–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugimoto, N., N. Takuwa, H. Okamoto, S. Sakurada, and Y. Takuwa. 2003. Inhibitory and stimulatory regulation of Rac and cell motility by the G(12/13)-Rho and G(i) pathways integrated downstream of a single G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor isoform. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1534–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer, T., D. Holowka, and L. Stryer. 1988. Highly cooperative opening of calcium channels by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Science. 240:653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumruker, T., and E.E. Prieschl. 2000. The role of sphingosine kinase in the signaling initiated at the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcepsilonRI) in mast cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 122:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathes, C., A. Fleig, and R. Penner. 1998. Calcium release-activated calcium current (ICRAC) is a direct target for sphingosine. J. Biol. Chem. 273:25020–25030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kluk, M.J., C. Colmont, M.T. Wu, and T. Hla. 2003. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced chemotaxis does not require the G protein-coupled receptor S1P1 in murine embryonic fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 533:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, M., S. Thangada, J. Paik, G.P. Sapkota, N. Ancellin, S. Chae, M. Wu, M. Morales-Ruiz, W.C. Sessa, D.R. Alessi, and T. Hla. 2001. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of the G protein-coupled receptor edg-1 is required for endothelial cell chemotaxis. Mol. Cell. 8:693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waters, C., B.S. Sambi, K.C. Kong, D. Thompson, S.M. Pitson, S. Pyne, and N.J. Pyne. 2003. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and platelet-derived growth factor act via platelet-derived growth factorbeta receptor-sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor complexes in airway smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:6282–6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coward, W.R., Y. Okayama, H. Sagara, S.J. Wilson, S.T. Holgate, and M.K. Church. 2002. NF-kappa B and TNF-alpha: a positive autocrine loop in human lung mast cells? J. Immunol. 169:5287–5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sjostrom, M., P.J. Jakobsson, M. Juremalm, A. Ahmed, G. Nilsson, L. Macchia, and J.Z. Haeggstrom. 2002. Human mast cells express two leukotriene C(4) synthase isoenzymes and the CysLT(1) receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1583:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellor, E.A., K.F. Austen, and J.A. Boyce. 2002. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and uridine diphosphate induce cytokine generation by human mast cells through an interleukin 4–regulated pathway that is inhibited by leukotriene receptor antagonists. J. Exp. Med. 195:583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamoto, H., N. Takuwa, T. Yokomizo, N. Sugimoto, S. Sakurada, H. Shigematsu, and Y. Takuwa. 2000. Inhibitory regulation of Rac activation, membrane ruffling, and cell migration by the G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG5 but not EDG1 or EDG3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:9247–9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner, H., and J.P. Kinet. 1999. Signalling through the high-affinity IgE receptor Fc epsilonRI. Nature. 402:B24–B30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manetz, T.S., C. Gonzalez-Espinosa, R. Arudchandran, S. Xirasagar, V. Tybulewicz, and J. Rivera. 2001. Vav1 regulates phospholipase cgamma activation and calcium responses in mast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3763–3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeldt, H.M., Y. Amrani, K.R. Watterson, K.S. Murthy, R.A. Panettieri, Jr., and S. Spiegel. 2003. Sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates contraction of human airway smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 17:1789–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuvillier, O., G. Pirianov, B. Kleuser, P.G. Vanek, O.A. Coso, S. Gutkind, and S. Spiegel. 1996. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 381:800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacKinnon, A.C., A. Buckley, E.R. Chilvers, A.G. Rossi, C. Haslett, and T. Sethi. 2002. Sphingosine kinase: a point of convergence in the action of diverse neutrophil priming agents. J. Immunol. 169:6394–6400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia, J.G., F. Liu, A.D. Verin, A. Birukova, M.A. Dechert, W.T. Gerthoffer, J.R. Bamberg, and D. English. 2001. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J. Clin. Invest. 108:689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stam, J.C., F. Michiels, R.A. Kammen, W.H. Moolenaar, and J.G. Collard. 1998. Invasion of T-lymphoma cells: cooperation between Rho family GTPases and lysophospholipid receptor signaling. EMBO J. 17:4066–4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]