Abstract

In autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APS), several organ-specific autoimmune diseases are clustered. Although APS type I is caused by loss of central tolerance, the etiology of APS type II (APS-II) is currently unknown. However, in several murine models, depletion of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) causes a syndrome resembling human APS-II with multiple endocrinopathies. Therefore, we hypothesized that loss of active suppression in the periphery could be a hallmark of this syndrome. Tregs from peripheral blood of APS-II, control patients with single autoimmune endocrinopathies, and normal healthy donors showed no differences in quantity (except for patients with isolated autoimmune diseases), in functionally important surface markers, or in apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal. Strikingly, APS-II Tregs were defective in their suppressive capacity. The defect was persistent and not due to responder cell resistance. These data provide novel insights into the pathogenesis of APS-II and possibly human autoimmunity in general.

Keywords: suppressor cells, autoimmune polyendocrinopathies, Addison's disease, type I diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis

Introduction

Autoimmunity is largely prevented by central and peripheral mechanisms of immunological tolerance. Mechanisms of peripheral tolerance can be further divided into active and passive regulation (1). One prominent mechanism of active peripheral tolerance has recently been reappreciated; that is, suppression of autoreactivity by specialized lymphocytes (2). Although they have been preferentially called regulatory T cells (Tregs) instead of suppressor T cells, their primary function is to suppress. Among several suppressor cells, murine CD4+ CD25+ Tregs have recently been characterized extensively (2). They are naturally anergic in vitro, but can expand in vivo (3). They suppress innate (4) as well as adaptive immunity, including memory (5). Their mode of suppression is not yet fully delineated, but forkhead transcription factor FOXP3 is required (6–8). Mutations in FOXP3 cause a severe inflammatory syndrome in children called IPEX (immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked syndrome) or X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome (9).

The human counterparts comprise 5–15% of peripheral CD4+ T cells and are usually tested in in vitro coculture assays with CD4+ CD25− responder cells (10–13). They can mediate infectious tolerance (10, 13). They are highly susceptible to apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal (14), and their suppressive capacity is most potent in the CD25high-expressing fraction (15). Several other groups have also generated valid data on the physiology of human Tregs using conventional CD4+ CD25+ Tregs (5, 11, 12, 14, 16).

Murine Tregs have been associated recently with various beneficial or detrimental effects in different models (i.e., down-regulation of autoimmunity, allergy, graft-versus-host disease, but also of immunity to tumors and infections; references 2, 17). However, CD4+ CD25+ Tregs were initially discovered by Sakaguchi et al. in a distinct model of murine autoimmunity (18). After ex vivo depletion of CD4+ CD25+ T cells, mice developed autoimmunity to multiple organs. Remarkably, most of the target organs are endocrine glands; therefore, they largely resemble autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II (APS-II) in humans.

Human APS is characterized by multiple endocrine diseases initiated by an autoimmune process in the same patient (19, 20). Early onset APS-I (also called autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome or APECED) is caused by a defect in central tolerance due to mutations in the autoimmune regulator AIRE (21) and includes Addison's disease and hypoparathyroidism along with susceptibility to mucocutaneous candidiasis (19, 20). The hallmark of adult onset APS-II is the combined occurrence of two or more of the following autoimmune endocrinopathies: Addison's disease, type I diabetes, or autoimmune thyroid disease (19, 20). Aside from the association with polymorphisms in CTLA-4 and an HLA-extended haplotype, the pathogenesis of APS-II is currently unknown (19, 20, 22). Due to the striking similarities with the autoimmune phenotype of mice depleted of CD4+ CD25+ T cells (18), we hypothesized that a defect of these cells must be a central component of the human syndrome. Therefore, we analyzed CD4+ CD25+ T cells phenotypically and functionally from patients with APS-II, control patients, and normal healthy donors.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects.

All APS-II and control patients were diagnosed by clinical and laboratory parameters, including autoantibodies against target tissues after long-standing disease. In addition, all patients were followed up for possible occurrence of additional autoimmune endocrine diseases. Specifically, control patients with Addison's disease had TSH values within the normal range during their last visit (TSH 0.75 μU/ml for patient 3 and TSH 1.56 μU/ml for patient 6; normal values for TSH are 0.3–3.5 μU/ml). Screening for antithyroid peroxidase, antithyroglobulin, and antiislet antibodies were negative. All patients were well controlled on hormone replacement therapy, which was their only medication during the study period. None of the APS-II patients exhibited hypoparathyroidism, skin or gastrointestinal comorbidity, immunodeficiency, candidiasis, or enamel hypoplasia clearly differentiating them from APS-I. IPEX could also be excluded due to onset, clinical differences, and female preponderance of our patients. Patients' age, combinations of endocrine diseases, and duration of each disease are shown in Table I. Normal healthy subjects from the area were recruited for voluntary blood donations. The age range of normal healthy donors was 24–60 yr with a mean age of 36 yr. Any normal donor or patient with signs or symptoms of infection or systemic immune activation was excluded before the study. All study subjects agreed on blood donation solely for the purpose of research according to guidelines of the university's ethical committee.

Table I.

Patients' Sex, Age, and Duration of Each Autoimmune Endocrine Diseasea

| Patient | Sex | Age | Addison's disease |

Type I diabetes |

Autoimmune thyroiditis |

Gonadal insufficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yr | yr | yr | yr | yr | ||

| 1 | F | 30 | 1 | – | 12 | – |

| 2 | F | 33 | – | 24 | 24 | – |

| 3 | F | 35 | 24 | – | 21 | 19 |

| 4 | F | 62 | 15 | 23 | 15 | – |

| 5 | F | 31 | 17 | – | 17 | – |

| 6 | F | 30 | 8 | – | 8 | – |

| 7 | F | 34 | 5 | – | 8 | – |

| 8 | M | 63 | 31 | 31 | – | – |

| 1 | F | 36 | – | – | 3 | – |

| 2 | F | 43 | – | 5 | – | – |

| 3 | M | 34 | 3 | – | – | – |

| 4 | F | 22 | – | 8 | – | – |

| 5 | F | 51 | – | – | 1 | – |

| 6 | M | 40 | 7 | – | – | – |

| 7 | F | 30 | – | 26 | – | – |

| 8 | F | 65 | – | 41 | – | – |

APS-II patients (top). Control patients with single autoimmune endocrinopathies (bottom). Refer to the Study Subjects section of Materials and Methods for further clinical details.

F, female; M, male.

Antibodies and Reagents.

Culture medium, OKT-3, and PHA were used as described previously (23). 1 μg/ml anti-CD28 mAb 9.3 was a gift from Bristol Myers Squibb. For FACS® analysis, the following conjugated antibodies were used: CD4 and HLA-DR (Immunotech); CD28, CD25, CTLA-4, and CD95 (BD Biosciences); and PD-1 (eBioscience). TGFβ was obtained from IQ Products, and glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor (GITR) was obtained from R&D Systems. Isotype controls (IgG1 and IgG2a) were also obtained from Immunotech. FITC-conjugated annexin V (Roche) in propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) containing buffer was used for quantification of apoptosis.

Isolation of CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− T Cells.

PBMCs were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque (BAG) density gradient centrifugation. CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs with a negative CD4+ T cell isolation kit obtained from Miltenyi Biotec according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purity was routinely confirmed by flow cytometric analysis (>95% CD4+) and also by the lack of proliferation to 1 μg/ml PHA. Similarly, CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− T cells were separated from pure, untouched CD4+ T cells using CD25 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

Isolation of CD4+ CD25high T Cells.

CD4+ T cells were isolated as aforementioned. The CD25high-expressing fraction was further separated from the CD25low and CD25− cells by flow cytometric sorting using CD4-FITC– and CD25-PE–labeled antibodies. Sorting was performed with a MoFlo machine (DakoCytomation). Purity of CD25high-expressing CD4+ T cells was 100%.

Cell Proliferation Assays.

5 × 103 cells were incubated for 7 d. In all proliferation assays, irradiated (3,000 gray) PBMCs were used as feeder cells at a ratio of 10:1. [3H]Thymidine uptake and incorporation into genomic DNA were used to quantify cellular proliferation as described previously (23).

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

Detection of various markers and quantification of apoptosis as described in the Results and Discussion sections were performed using an EPICS XL™ flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Cells were stained with different combinations of FITC- and PE-conjugated mAbs and their appropriate isotype controls. T cells were incubated for 20–30 min at 4°C in the dark. After washing cells with PBS/1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. In all experiments, gates were set so that negative controls stained <1% false positive cells.

Quantification of Early Apoptosis, Late Apoptosis, and Necrosis.

2.5 × 104 CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− cells were kept in culture medium alone or supplemented with 10 U/ml of IL-2 for 2 d in flat-bottom microtiter plates. Features of cell death were detected by staining with FITC-conjugated annexin V in propidium iodide–containing staining buffer for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. After flow cytometric analysis, four populations can be distinguished as follows: viable cells (annexin V negative and propidium iodide negative), early apoptotic cells (annexin V positive and propidium iodide negative), late apoptotic cells (annexin V positive and propidium iodide intermediate), and primary necrotic cells (propidium iodide highly positive).

Semiquantitative Analysis of mRNA by RT-PCR.

To analyze the expression of human FOXP3 transcripts, 5 × 105 CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− T cells were lysed immediately after isolation. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini kit™ (QIAGEN) as described previously (23). Messenger RNA was reverse transcribed with oligo(dT) primers and amplified with gene-specific primers. Primer sequences can be obtained from the authors upon request. cDNA was amplified for 28 and 35 cycles for FOXP3, and for 21 and 28 cycles for GAPDH.

Statistical Analyses.

One-way analysis of variance with Tukey-Kramer posttest and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test were performed using InStat™ software (version 3.00; GraphPad).

Results and Discussion

Quantification and Functional Characterization of CD4+ CD25+ T Cells in Peripheral Blood.

First, we isolated PBMCs from normal healthy donors, APS-II, and control patients, and quantified CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells. The average percentage of CD4+ CD25+ T cells from our normal donors was 9.3% compatible with previous counts of human Treg numbers in healthy persons. The quantity of this subpopulation of CD4+ T cells was similar in patients with APS-II (9.0% on average), but generally reduced in blood from control patients (3.0% on average). No CD4 lymphopenia was noted in either study group. Following quantities over time, we found persistently reduced levels of Treg numbers from control patients (unpublished data), pointing toward a possible intrinsic defect in keeping normal quantities of natural Tregs in patients with single endocrinopathies.

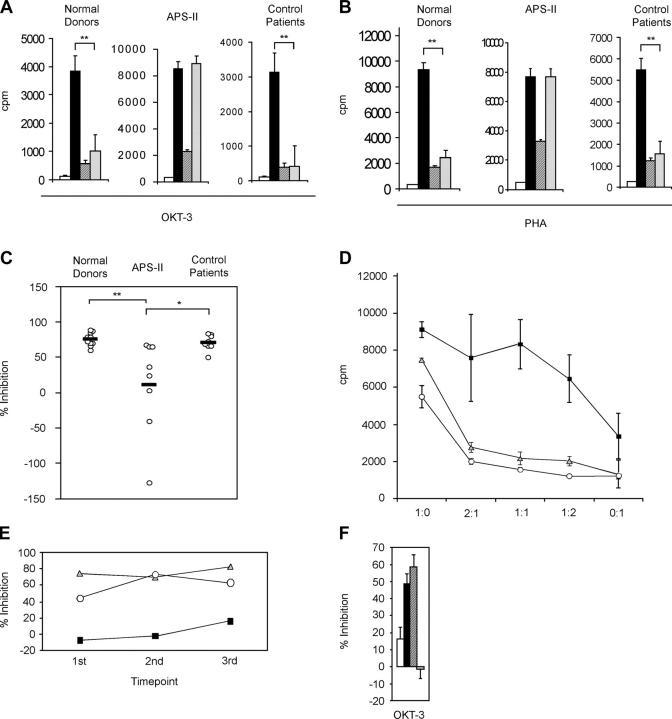

To functionally analyze Tregs, we separated CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− T cell fractions. Mixing both populations from normal donors at a ratio of 1:1 induced profound suppression of CD25− T cell proliferation in response to OKT-3 (Fig. 1 A) or PHA (Fig. 1 B), respectively. Similar results were obtained from cells of control patients (Fig. 1, A and B). Strikingly, the suppressive capacity of CD4+ CD25+ T cells from APS-II patients was consistently impaired (Fig. 1, A and B). Tregs from APS-II patients were also dysfunctional after costimulation with soluble anti-CD28 plus OKT-3 compared with normal donors or control patients (unpublished data). Comparing percentages of inhibition of proliferation from each study subject indicated that coculture of cells from some APS-II patients even induced proliferation instead of inhibition (Fig. 1 C), reflecting a complete loss of suppressor function. The defect was partially reversible if higher numbers of Tregs were titrated to responders (Fig. 1 D), whereas Tregs from normal donors and control patients strongly suppressed in a cell number–dependent manner (Fig. 1 D). To test whether Tregs from APS-II patients were still responsive to IL-2, we added IL-2 to the cocultures in addition to OKT-3 stimulation. Tregs were not hyporesponsive any longer, and inhibition of proliferation was abolished in all three groups (unpublished data). To examine if lack of suppressor function is also stable over time, we performed identical coculture experiments at several time points in three subjects. Loss of suppressor function in APS-II as well as intact function in normal donor and control patient were conserved over a time period of several months in each of the three study subjects (Fig. 1 E).

Figure 1.

Functional analysis of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs. (A and B) Background proliferation of irradiated feeder cells (white bars), proliferation of CD4+ CD25− responder cells (black bars), CD4+ CD25+ Tregs (crosshatched bars), or of both populations added in a 1:1 ratio (diagonally striped bars) from normal healthy donors (n = 10), APS-II (n = 8), or control patients (n = 8) in response to OKT-3 or PHA stimulation, respectively. p-values for OKT-3 stimulation were as follows (A): ** = 0.0078 (normal donors), ** = 0.0078 (control patients); and for PHA stimulation: ** = 0.002 (normal donors), ** = 0.0078 (control patients). (C) Percentages of inhibition of proliferation of CD4+ CD25− responder cells by CD4+ CD25+ Tregs at a 1:1 ratio from normal healthy donors (n = 10), APS-II (n = 8), or control patients (n = 8), respectively. Values were calculated from proliferation assays with PHA stimulation. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. (D) Inhibition of proliferation of CD4+ CD25− responder cells by CD4+ CD25+ Tregs at different ratios (responders to suppressors) from normal donors (gray triangles, n = 7), APS-II (black squares, n = 6), or control patients (white circles, n = 6). Error bars represent SEM. (E) Percentages of inhibition of proliferation of CD4+ CD25− responder cells by CD4+ CD25+ Tregs at a 1:1 ratio from a representative normal donor (gray triangles), APS-II (black squares), or control patient (white circles) over a period of >1 yr. Values were calculated from proliferation assays with OKT-3 stimulation. Blood drawn from each study subject (indicated by each time point) were separated by several weeks to months. (F) Determination of the origin of defective suppression. Percentages of inhibition of proliferation of CD4+ CD25− responder cells by CD4+ CD25+ Tregs at a 1:1 ratio. Responders and suppressors from either normal donors or APS-II patients were mixed in the following combinations: APS responders + APS suppressors (white bar), APS responders + normal donor suppressors (black bar), normal donor responders + normal donor suppressors (crosshatched), and normal donor responders + APS suppressors (diagonally striped bar). Each bar represents an average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM.

Next, we wanted to dissect defective suppressor cell function versus responder cell resistance in APS-II patients because defective regulation seen in the coculture assays from cells of APS-II patients could theoretically be attributed to either impaired suppressor function of Tregs (as proposed) or resistance of responder cells to Treg-mediated suppression (24). To test both possibilities, we mixed responder cells from APS-II patients with Tregs from normal donors and vice versa (Fig. 1 F). Although Tregs from normal donors appropriately suppressed responders from APS-II patients, APS-II Tregs could obviously not inhibit proliferation of responder cells from normal donors (Fig. 1 F), indicating that impaired suppression of proliferation is clearly due to defective Tregs instead of resistance of responders.

Finally, we also studied suppressor function in the CD4+ CD25high compartment of two representative patients with APS-II (one with consistent impairment and one with intact Treg function). FACS®-sorted, CD25high-expressing CD4+ T cells from the patient with dysfunctional Tregs were still impaired in their suppressor function compared with normal donor cells (32.4% vs. 78.8% for inhibition of PHA-induced proliferation and 18.6% vs. 68.4% for inhibition of OKT-3–induced proliferation) or APS-II cells from the patient with intact Tregs (unpublished data). In all three subjects, sorted cells rendered approximately similar results as MACS-separated total CD25+ cells.

Phenotypic Characterization of CD4+ CD25+ T Cells.

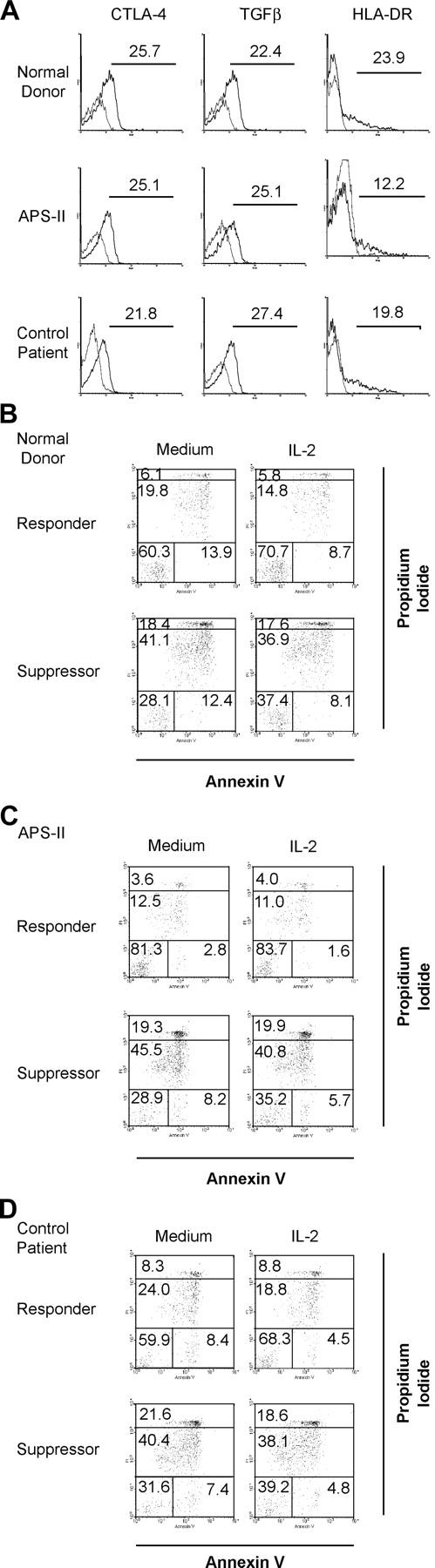

To further investigate the profound defect of Tregs from APS-II patients, we wanted to examine possible phenotypic changes of the Tregs. Surface CTLA-4 and membrane-bound TGFβ have been described as possible mediators of murine Treg function (2, 17, 25). Although we could confirm expression of these molecules on human Tregs (Fig. 2 A), we did not find significant changes of surface expression of CTLA-4 or TGFβ on APS-II Tregs compared with normal donors or control patients (Fig. 2 A). Also, the number of Tregs expressing these markers did not differ between groups (Fig. 2 A). Although not significantly expressed on resting Tregs, GITR is up-regulated upon activation and transmits negative signals into murine Tregs (26, 27). Therefore, we also wanted to determine if abnormally elevated levels of GITR on resting Tregs from patients with APS-II might be measurable. However, we did not detect significant expression of GITR on Tregs from any study group (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs. Cell surface expression of CTLA-4, TGFβ, and HLA-DR on CD4+ CD25+ Tregs after isolation from normal donors, APS-II, or control patients. Thin lines represent isotype controls. The data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments; values of each graph represent the percentage of positive cells. (B–D) Rate of apoptosis of CD4+ CD25− responder cells (Responder) and CD4+ CD25+ Tregs (Suppressor) from normal donors (B), APS-II (C), and control patients (D) after 2 d of culture in medium alone versus medium supplemented with IL-2. Four populations can be distinguished as described in Materials and Methods. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments; values represent the percentage of positive cells.

Besides these functionally relevant molecules, Tregs express several activation markers. We thought that one of them, HLA-DR, would be of special interest. Aside from being expressed on activated human T cells, HLA-DR is predominantly on the surface of Tregs compared with CD25− T cells (15). Because MHC class II molecules on T cells have been shown to be involved in T–T interactions, causing anergy in the target cells (28), we have chosen to screen for alterations in HLA-DR expression or density on Tregs. However, no significant differences have been found between Tregs from normal donors, APS-II, or control patients (Fig. 2 A). Similarly, analysis of CD28 and PD-1 (two important members of the costimulatory family), and of Fas (CD95) also revealed no differences (unpublished data). Because some phenotypic alterations might not become apparent before triggering cells, we also measured GITR and CTLA-4 on Tregs after activation. To this end, we stimulated cells with plate-bound OKT-3 and IL-2 for 7 d. But, again, no significant differences were detectable between groups (unpublished data).

Apoptosis of CD4+ CD25+ and CD25− T Cells after Growth Factor Withdrawal.

Taams et al. demonstrated that human Tregs rapidly die in vitro, whereas CD4+ CD25− T cells are substantially less susceptible to growth factor withdrawal (14). Adding IL-2 to the culture could increase the survival rate of Tregs to a limited extent (14). To exclude the possibility that Tregs from APS-II or control patients would die faster than normal donor Tregs, we measured the rate of apoptosis after 2 d of culture in medium with or without IL-2 (Fig. 2, B–D). Although we could confirm that suppressor cells die more quickly than responder cells in vitro (Fig. 2 B), we did not detect an increase of cell death in APS-II (Fig. 2 C) or control patient cells (Fig. 2 D). This was evident for early, late apoptotic, or necrotic cell death (Fig. 2, B–D). Furthermore, IL-2 could rescue both CD25− and CD25+ cells to a limited extent in our system (Fig. 2 B), but no lack of rescue was noted in cells from APS-II or control patients (Fig. 2, C and D).

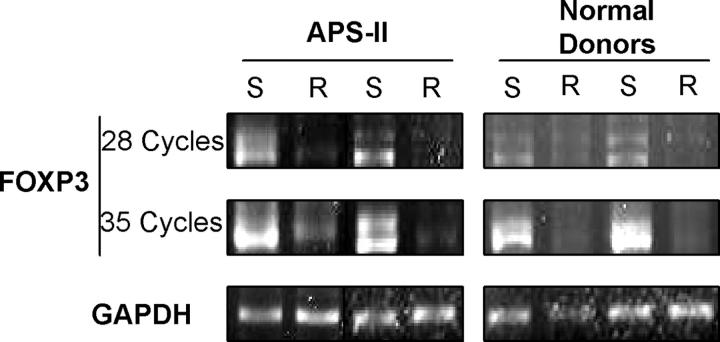

The pathogenesis of APS-II is largely unknown, and a common pathogenetic mechanism responsible for the combined occurrence of multiple endocrinopathies in these patients has not been elucidated. We found defective suppressor function of Tregs from the majority of patients with APS-II, whereas we could not detect overt quantitative or phenotypic abnormalities in Tregs from these patients. In addition, their apoptotic behavior to growth factor withdrawal was intact. However, an increase of contamination with recently activated CD25+ T cells could be excluded for the following reasons. Any study subject with signs or symptoms of infection was excluded. Autoimmune endocrine diseases do not go along with systemic immune activation due to their organ-specific nature. APS-II patients did not exhibit increased numbers of peripheral CD25+ T cells compared with normal donors. We also confirmed suppressor dysfunction by FACS®-sorted CD25high-expressing Tregs. Furthermore, Tregs from all study groups had similar phenotypic features and apoptotic behaviors. Tregs from APS-II patients showed identical functional features as Tregs from normal donors or control patients with the exception of defective suppressor function (i.e., they showed similar in vitro anergy and responsiveness to IL-2). Finally, in preliminary experiments, we semi-quantified two samples of FOXP3 messenger RNA from APS-II Tregs. Both contained similar levels of FOXP3 transcripts compared with normal donor Tregs (Fig. 3) despite defective suppressor function, clearly indicating that true Tregs were dysfunctional. Interestingly, Tregs from one additional patient exhibited reduced levels of FOXP3. However, further detailed experiments are needed to confirm and extend this finding.

Figure 3.

Levels of FOXP3 transcripts. FOXP3 messenger RNA was detected after RT-PCR in CD4+ CD25+ Tregs (S) or CD25− responder cells (R). Samples from two normal donors and APS-II patients, respectively, are shown. Amounts of GAPDH transcripts are shown (bottom).

Defective Treg function in humans with APS-II has wide implications for autoimmunity in general. Although depletion of murine CD4+ CD25+ T cells has initially been demonstrated to cause predominantly polyglandular autoimmunity (18), functional Tregs seem to also prevent disease in various other murine models (2). Therefore, defective human Treg cell function might also modulate other disease states, such as multiple sclerosis or systemic lupus erythematosus. With regard to APS-II, our data provide first advances in understanding the pathogenesis of this syndrome. Because strategies intervening early in the disease process have been proven to be effective in organ-specific autoimmunity (29), this might be of future importance.

In summary, we have demonstrated persistent defective suppressor activity of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs in APS-II, thereby contributing to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this syndrome and possibly autoimmunity in general. Once molecular mechanisms of suppressor function are better delineated, manipulations of human Tregs may eventually allow improvement of immunomodulatory strategies in diseases with impaired suppressor function.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study subjects for their participation. We are also grateful to Dr. W. Baum for assistance of the hybridoma antibody elution, to E. Scherb for excellent technical support, and to Bristol Myers Squibb for providing the anti-CD28 mAbs.

This work was supported by grants from the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF C13) and the German Research Association (Sonderforschungsbereich 263) to H.-M. Lorenz, and from the ELAN Fonds fuer Forschung und Lehre (grant 01.11.20.1) of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg to M. A. Kriegel and H.-M. Lorenz.

References

- 1.Walker, L.S., and A.K. Abbas. 2002. The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shevach, E.M. 2002. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamazaki, S., T. Iyoda, K. Tarbell, K. Olson, K. Velinzon, K. Inaba, and R.M. Steinman. 2003. Direct expansion of functional CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells by antigen-processing dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:235–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maloy, K.J., L. Salaun, R. Cahill, G. Dougan, N.J. Saunders, and F. Powrie. 2003. CD4+CD25+ T(R) cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 197:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levings, M.K., R. Sangregorio, and M.G. Roncarolo. 2001. Human CD25+ CD4+ T regulatory cells suppress naive and memory T cell proliferation and can be expanded in vitro without loss of function. J. Exp. Med. 193:1295–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontenot, J.D., M.A. Gavin, and A.Y. Rudensky. 2003. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hori, S., T. Nomura, and S. Sakaguchi. 2003. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 299:1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khattri, R., T. Cox, S.A. Yasayko, and F. Ramsdell. 2003. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett, C.L., J. Christie, F. Ramsdell, M.E. Brunkow, P.J. Ferguson, L. Whitesell, T.E. Kelly, F.T. Saulsbury, P.F. Chance, and H.D. Ochs. 2001. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat. Genet. 27:20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieckmann, D., C.H. Bruett, H. Ploettner, M.B. Lutz, and G. Schuler. 2002. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory, contact-dependent T cells induce interleukin 10–producing, contact-independent type 1–like regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieckmann, D., H. Plottner, S. Berchtold, T. Berger, and G. Schuler. 2001. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J. Exp. Med. 193:1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonuleit, H., E. Schmitt, M. Stassen, A. Tuettenberg, J. Knop, and A.H. Enk. 2001. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 193:1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonuleit, H., E. Schmitt, H. Kakirman, M. Stassen, J. Knop, and A.H. Enk. 2002. Infectious tolerance: human CD25+ regulatory T cells convey suppressor activity to conventional CD4+ T helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taams, L.S., J. Smith, M.H. Rustin, M. Salmon, L.W. Poulter, and A.N. Akbar. 2001. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baecher-Allan, C., J.A. Brown, G.J. Freeman, and D.A. Hafler. 2001. Cd4(+)cd25(high) regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 167:1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annunziato, F., L. Cosmi, F. Liotta, E. Lazzeri, R. Manetti, V. Vanini, P. Romagnani, E. Maggi, and S. Romagnani. 2002. Phenotype, localization, and mechanism of suppression of CD4+CD25+ human thymocytes. J. Exp. Med. 196:379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakaguchi, S., N. Sakaguchi, J. Shimizu, S. Yamazaki, T. Sakihama, M. Itoh, Y. Kuniyasu, T. Nomura, M. Toda, and T. Takahashi. 2001. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 182:18–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi, S., N. Sakaguchi, M. Asano, M. Itoh, and M. Toda. 1995. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devendra, D., and G.S. Eisenbarth. 2003. 17. Immunologic endocrine disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111:S624–S636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson, M.S. 2002. Autoimmune endocrine disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson, M.S., E.S. Venanzi, L. Klein, Z. Chen, S.P. Berzins, S.J. Turley, H. von Boehmer, R. Bronson, A. Dierich, C. Benoist, and D. Mathis. 2002. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. 298:1395–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallaschofski, H., A. Meyer, U. Tuschy, and T. Lohmann. 2003. HLA-DQA1*0301-associated susceptibility for autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II and III. Horm. Metab. Res. 35:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank, N., M. Kriegel, T. Hieronymus, T. Geiler, S. Winkler, J.R. Kalden, and H.M. Lorenz. 2001. CD45 tyrosine phosphatase controls common gamma-chain cytokine-mediated STAT and extracellular signal-related kinase phosphorylation in activated human lymphoblasts: inhibition of proliferation without induction of apoptosis. J. Immunol. 166:6034–6040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasare, C., and R. Medzhitov. 2003. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science. 299:1033–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura, K., A. Kitani, and W. Strober. 2001. Cell contact–dependent immunosuppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface–bound transforming growth factor β. J. Exp. Med. 194:629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHugh, R.S., M.J. Whitters, C.A. Piccirillo, D.A. Young, E.M. Shevach, M. Collins, and M.C. Byrne. 2002. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity. 16:311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu, J., S. Yamazaki, T. Takahashi, Y. Ishida, and S. Sakaguchi. 2002. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 3:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaSalle, J.M., P.J. Tolentino, G.J. Freeman, L.M. Nadler, and D.A. Hafler. 1992. Early signaling defects in human T cells anergized by T cell presentation of autoantigen. J. Exp. Med. 176:177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herold, K.C., W. Hagopian, J.A. Auger, E. Poumian-Ruiz, L. Taylor, D. Donaldson, S.E. Gitelman, D.M. Harlan, D. Xu, R.A. Zivin, and J.A. Bluestone. 2002. Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1692–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]