Abstract

Receptor-interacting protein (RIP) has been reported to associate with tumor necrosis–associated factor (TRAF)2 and TRAF6. Since TRAF2 and TRAF6 play important roles in CD40 signaling and TRAF6 plays an important role in TLR4 signaling, we examined the role of RIP in signaling via CD40 and TLR4. Splenocytes from RIP−/− mice proliferated and underwent isotype switching normally in response to anti-CD40–IL-4 but completely failed to do so in response to LPS–IL-4. However, they normally up-regulated TNF-α and IL-6 gene expression and CD54 and CD86 surface expression after LPS stimulation. RIP−/− splenocytes exhibited increased apoptosis and impaired Akt phosphorylation after LPS stimulation. These results suggest that RIP is essential for cell survival after TLR4 signaling and links TLR4 to the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase–Akt pathway.

Keywords: NFκB, IκB, p38 MAP kinase, IL-6, TNF-α

Introduction

Receptor-interacting protein (RIP) is a death domain kinase that associates with tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)1 (1). RIP binds TNFR-associated factor (TRAF)2 (2) and is essential for TNF-induced NFκB activation and protection from cell death (3). RIP also interacts with IkB kinase (IKK)γ (NEMO) (4), which plays a critical role in activation of the IKK complex, IκB phosphorylation, and NFκB activation and expression of antiapoptotic genes. RIP interacts with TRAF6 through the p62 adaptor protein to potentiate the activation of the IKK complex by TRAF6 (5).

RIP−/− mice die at 1–3 d of age with apoptosis of lymphoid and adipose tissues (3). Their viability is partially rescued by breeding on the TNFR1−/− background (6). RIP−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) fail to activate NFκB in response to TNF-α and have enhanced sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death (3). RIP−/− thymocytes show increased death, which is rescued by breeding on the TNFR2−/− background in an NFκB-independent manner (6).

Ligation of CD40 or TLR4 on B cells leads to proliferation, isotype switching and up-regulation of the surface expression of costimulatory molecules (7). B cell activation via CD40 requires binding of TRAF2 and/or TRAF3 (8). Binding of TRAF6 controls affinity maturation and the generation of long-lived plasma cells (9). TLR4 signaling by LPS activates two major signal transduction pathways. The first is mediated by MyD88–IRAK–TRAF6 and leads to the activation of IKK, JNK, and p38. The second, MyD88-independent pathway, is mediated by TRAM–TRIF–IRF3 and leads to the expression of type I interferons and up-regulation of expression of costimulatory molecules (10). Both pathways are required for optimal activation of NFκB and induction of NFκB-dependent genes (11, 12) and may intersect at the level of TRAF6, as TRIF interacts with TRAF6 (13).

Other members of the RIP family include RIP2, which has been implicated in TLR signaling (14, 15), RIP3, which is not essential for NFκB activation by Toll receptors (16), and RIP4, which plays an essential role in B cell development and activation (17). The fact that RIP interacts with TRAF2 and TRAF6 prompted us to investigate the potential role of RIP in CD40 and TLR4 signal transduction. To address this question, we took advantage of the availability of RIP−/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Previously generated RIP+/−/TNFR1−/− mice (6) were crossed to obtain RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− double mutant mice. The pups were chosen at 2–5 d of age as the runts of the litter. RIP+/+ homozygous and RIP+/− heterozygous littermates were used as controls. Genotype was confirmed by PCR as described previously (6). Same strain (129 Svev/C57Bl6), age-matched, WT controls were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Experiments and animal care were performed according to institutional guidelines.

FACS® Analysis.

Single cell suspensions were stained with FITC-PE–conjugated mAbs or with annexin-FITC as described previously (8). Quadrants were drawn according to isotype control staining. FITC- or PE-conjugated mAbs used in these studies were: anti-CD3, anti-B220, anti-IgM, anti-CD86, and anti-CD54 (BD Biosciences). For CD54 and CD86 expression, purified splenic B cells (>80% B220+) obtained by positive selection using MACS CD45R (B220) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) were cultured for 24 h with complete medium (RPMI 1640 from GIBCO BRL supplemented with 10% FBS from Sigma-Aldrich and 1% penicillin/streptomycin from Life Technologies), sCD40L (1:20 dilution of supernatants from muCD40L:muCD8-transfected J558L cells), or LPS (10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich).

In Vitro Proliferation and Isotype Switching of B Cells.

For proliferation, spleen cells or purified B cells (0.7 × 106/ml) were cultured in complete medium alone or in the presence of anti-CD40 (1 μg/ml, HM40-3; BD Biosciences) with or without IL-4 (25 ng/ml; R&D Systems), LPS (10 mg/ml) with or without IL-4, and CpG ODN1826 (10 μM; Invivogen) for 72 h, pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine for an additional 16 h, harvested, and scintillation was counted. For isotype switching, spleen cells (0.5 × 106/ml) were cultured in complete medium alone or in the presence of IL-4, anti-CD40 alone or with IL-4, LPS alone or with IL-4. Supernatants were collected after 6 d, and immunoglobulins were assayed by ELISA as described previously (8).

RT-PCR for ɛ and γ1 Germ Line Transcripts, Activation-induced Deaminase, b2-Microglobulin, and mTLR4.

RNA was extracted from 72-h cultured splenocytes using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and was reverse transcribed using Superscript II RT (Invitrogen). PCR reactions for ɛ and γ1 germ line transcripts (GLTs), activation-induced deaminase (AID), and β2-microglobulin and for mTLR4 were performed as described previously on various dilutions of cDNA to ensure that the products measured were in the linear range (8, 18). Amplified products were separated on 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Real-Time PCR for TNF-α and IL-6 Gene Expression.

RNA was prepared from splenocytes cultured for 16 h with medium or LPS (10 μg/ml) as above. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR reactions were run on an ABI Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems) sequence detection system platform. Sybr green chemistry was used for TNF-α (TNF-α forward, 5′-cccacgtcgtagcaaacc-3′ and TNF-α reverse, 5′-gcagccttgtcccttgaa-3′) and β-actin. For IL-6, Taqman primers with FAM-labeled probe (Applied Biosystems) were used. The relative gene expression among the different samples was determined using the method described by Pfaffl (19). Melt curve analysis was performed for products detected by sybr green to ensure purity of product.

Western Blotting.

Cell lysates were obtained from splenocytes (0.5 × 106 cells/condition) suspended in medium containing 1% FCS and stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml) or CpG ODN1826 (3 μM) for 15 min. Blots were incubated with antibodies specific for phospho-Akt, Akt (Becton Dickinson), phospho-p38, or phospho-IκB (Cell Signaling) followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–rabbit or goat anti–mouse antibodies (Becton Dickinson). Blots were scanned and OD of bands quantitated using NIH Image 16.2 software. Fold induction was calculated as the ratio of OD of the phosphoproteins in lysates of LPS-stimulated to unstimulated cells, each normalized for the OD of their Akt band.

Online Supplemental Material.

Fig. S1 shows cell lysates that were obtained from MEFs grown in DME (BioWhittaker) supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml of each) and left untreated or treated with 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) or 10 ng/ml IL-1β (R&D Systems). IKK activity in the cell lysates was detected using an anti-phospho-IκB–specific antibody (Cell Signaling). IKK levels were also compared in these lysates using an anti-IKKα rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Fig. S1 available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20040446/DC1.

Results and Discussion

RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− Mice Have Normal Percentages of B Cells in Their Spleens.

Splenocytes were taken from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates. Because in all experiments splenocytes from RIP+/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates behaved identically, we present data only on RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− controls. Total number of splenocytes was comparable between RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− and age-matched WT controls but was significantly lower in the double mutant mice (6.2 × 106 ± 2 versus 20 × 106 ± 6 in littermate controls and 2 × 106 ± 8 in WT controls). The three- to fourfold decrease in splenocyte number in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups is commensurate with the threefold reduction in the weight of these pups (3).

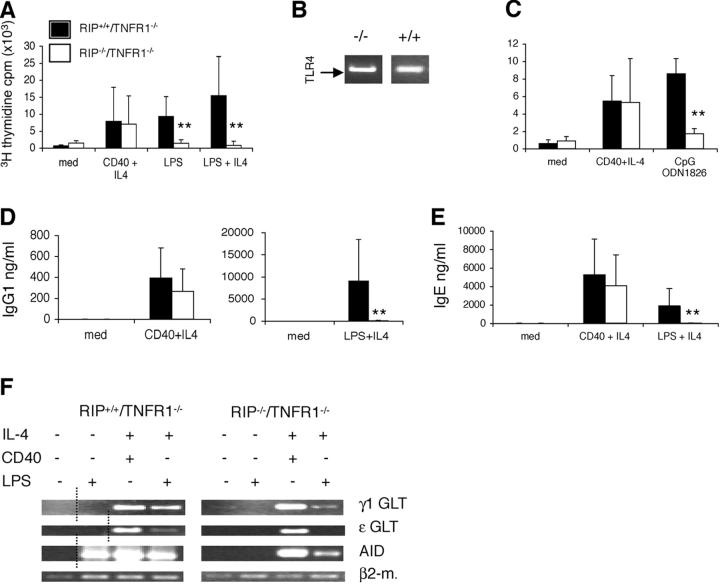

The percentages of B cells, B cell subsets, and T cells were assessed by FACS® analysis (Fig. 1). The percentage of B220+ cells was comparable in spleens from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates. This is consistent with normal B cell development in RIP−/− embryos (3) and with the observation that reconstitution of irradiated WT and RAG1−/− mice with fetal liver cells from RIP−/− embryos results in normal B cell development (6). More importantly, the percentages of mature B220+sIgM+ cells were comparable in splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates. The decreased percentage of CD3+ cells in spleens of RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups is consistent with the deleterious effect of RIP disruption on thymocyte development (6). Spleen cell populations of RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates were comparable to those present in age-matched WT controls (unpublished data). This is consistent with the observation that TNFR1−/− mice have normal B cell development (20).

Figure 1.

Splenocyte phenotype. FACS® analysis of B and T cell populations in total splenocytes from a RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− mouse and a RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermate, representative of three experiments performed. Percentages of total splenocytes are shown.

RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B Cells Fail To Proliferate Specifically in Response to LPS.

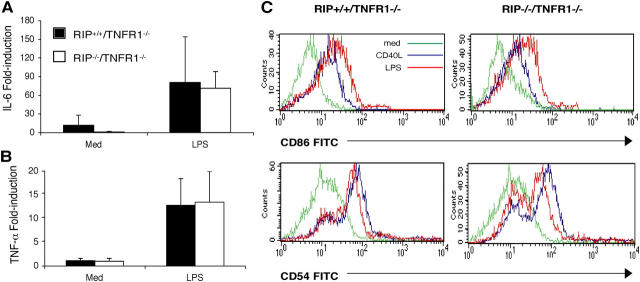

Splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− mice proliferated normally in response to anti-CD40 + IL-4, whereas they completely failed to proliferate in response to LPS. This failure was not rescued by IL-4 (Fig. 2 A). This result was confirmed in two separate experiments performed on purified B cells (unpublished data), suggesting that the failure to proliferate to LPS reflects an intrinsic defect in B cells. The failure of B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− to proliferate to LPS was not simply due to lack of TLR4 expression. RT-PCR analysis of mRNA revealed TLR4 expression in purified B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (Fig. 2 B). TLR9 engagement by the ligand CpG ODN 1826 also causes B cell proliferation (21). TLR9-induced proliferation was significantly impaired in splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− mice (Fig. 2 C).

Figure 2.

B cell proliferation and immunoglobulin synthesis. (A) Proliferation of splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups (n = 7) and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (n = 7) stimulated for 72 h with anti-CD40 mAb ± IL-4 and LPS ± IL-4. **P < 0.005. (B) Expression of mTLR4 in B220+ B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− mice. (C) Proliferation of splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups (n = 4) and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (n = 4) stimulated for 72 h with CpG ODN 1826. **P < 0.005 IgG1 (D) and IgE (E) in supernatants 6 d after stimulation of total splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups (n = 9) and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (n = 10). **P < 0.005. (F) Molecular events of isotype switching. Expression of Cγ1, Cɛ, and AID transcripts measured by RT-PCR in total splenocytes stimulated for 72 h with anti-CD40 mAb + IL-4 and LPS ± IL-4. The dotted lines show where irrelevant lanes were cut out. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B Cells Have Severely Impaired IgG1 and IgE Isotype Switching in Response To LPS 1 IL-4.

To further assess the response of B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups to LPS, we examined the ability of splenocytes from these mice and littermate controls to secrete IgG1 and IgE in response to stimulation with LPS + IL-4 or anti-CD40 + IL-4. Splenocytes from the double mutant mice secreted normal amounts of IgG1 and IgE in response to anti-CD40 + IL-4 but were severely impaired in their ability to secrete IgG1 and IgE in response to LPS + IL-4 (Fig. 2, D and E). The molecular events involved in isotype switching in naïve B cells include expression of GLTs and expression of the gene for AID, followed by deletional switch recombination and expression of mature post switch transcripts (7). LPS induces expression of the AID gene and synergizes with IL-4 in inducing the expression of Cγ1 and Cɛ GLTs to result in isotype switching to IgG1 and IgE. The ability of LPS to activate these events in B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and littermate controls was examined. LPS by itself induced AID gene expression in RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− B cells and synergized with IL-4 to induce Cγ1 and Cɛ GLTs in these cells (Fig. 2 F). In contrast, LPS failed to induce detectable AID gene expression in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B cells and synergized poorly with IL-4 in inducing expression of Cγ1 GLT and AID in these cells. LPS also failed to synergize with IL-4 in inducing detectable Cɛ GLT in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B cells. The defect in isotype switching of RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B cells in response to LPS is not due to a generalized defect in these cells because CD40 ligation synergized with IL-4 to induce expression of Cγ1 GLT, Cɛ GLT, and AID in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups that was comparable to that observed in littermate controls. Since LPS induction of isotype switching in B cells has been shown to be division linked (22), the failure of RIP-deficient B cells to undergo isotype switching in response to LPS may reflect their failure to proliferate.

LPS Induction of TNF-α and IL-6 Expression Is Normal in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− Splenocytes.

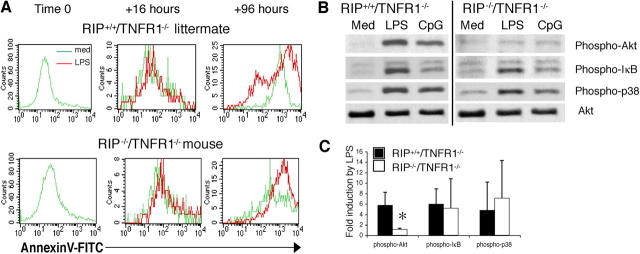

LPS stimulation of splenocytes induces the expression of several NFκB-dependent genes that include IL-6 and TNF-α, which are primarily expressed in macrophages and dendritic cells (23). LPS up-regulated IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression in splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− mice to an extent that was equivalent to that induced in splenocytes from RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (Fig. 3, A and B). This suggests that RIP is not essential for LPS-induced NFκB activation and is consistent with previous observations that LPS and IL-1 induce a normal NFκB response in RIP−/− thymocytes and MEFs (reference 3 and Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20040446/DC1). In contrast, RIP2 has been shown to be important for LPS activation of NFκB and induction of IL-6 and TNF-α gene expression (14, 15).

Figure 3.

Cytokine gene expression. Induction of mRNA for IL-6 (A) and TNF-α (B) by LPS in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups (n = 3) and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− controls (n = 3). Values show the fold induction over unstimulated control splenocytes cultured with medium as determined by real time PCR. (C) Up-regulation of CD86 and CD54 expression on B cells. B220+ cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP−/+/TNFR1−/− mice were left unstimulated (green) or were stimulated for 24 h with sCD40L (blue) or LPS (red). Similar results were obtained in four independent experiments (one using purified B cells).

Up-regulation of CD54 and CD86 Surface Expression Is Normal in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− B Cells.

LPS and CD40 ligation up-regulate the expression of several surface markers on B cells including the adhesion molecule CD54 (ICAM-1) and the costimulatory molecule CD86 (B7.2) (24). The TRIF–IRF3 type I interferon pathway is essential for the up-regulation by LPS of the costimulatory molecule CD86, whose promoter contains STAT sites that are potential targets of type I interferon–activated STATs but no NFκB sites (25). LPS stimulation of purified splenic B cells caused comparable up-regulation in the surface expression of CD54 and CD86 on B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and control RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates (Fig. 3 C). B cells from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups also normally up-regulated CD54 and CD86 expression in response to CD40 ligation. These results suggest that TLR4 signaling via the TRAM–TRIF–IRF3 pathway is preserved in RIP-deficient B cells.

RIP Is Essential for Cell Survival After LPS Stimulation.

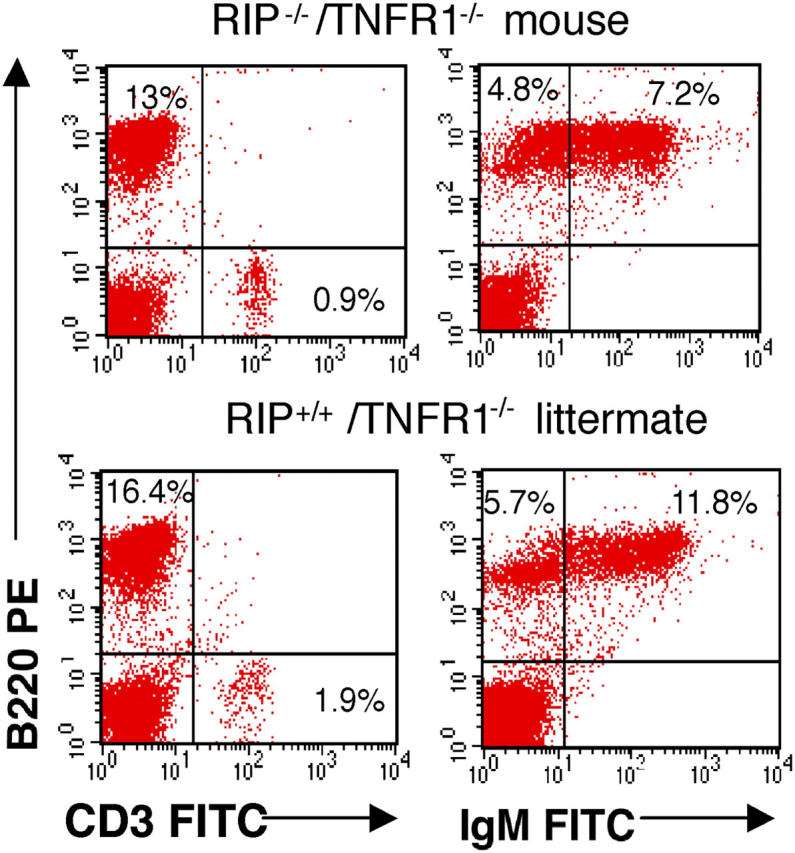

The observation that relatively early events after TLR4 signaling, e.g., up-regulation of surface markers and cytokine gene expression, were preserved, whereas later events, e.g., proliferation and isotype switching, were severely impaired in RIP-deficient splenocytes prompted us to examine the survival of these cells after sTLR4 ligation. Splenocytes were cultured with medium or LPS, and apoptosis was assessed at 0, 16, and 96 h by staining with annexin V–FITC and B220-PE. Fig. 4 A shows that the percentage of annexin V+–B220+ cells in unstimulated cultures and in cultures stimulated with LPS for 16 h was equivalent for RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− B cells. In contrast, the percentage of annexin V+–B220+ cells in cultures stimulated with LPS for 96 h was higher for RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− than RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− mice (92 versus 64%, n = 2). Conversely, the percentage of viable annexin V−–B220+ cells is lower in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− than in RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− B cells (8 versus 36%, n = 2). LPS stimulation of RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− splenocytes also caused increased apoptosis of B220− non–B cells. The percentage of annexin V+–B220− non–B cells at 96 h was 72.5% in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− splenocytes versus 28% in RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− splenocytes (n = 2). These results suggest that RIP plays an important role in cell survival after TLR4 ligation. The observation that TLR4 induced normal expression of NFκB-dependent genes in RIP-deficient splenocytes suggests that, as in thymocytes and MEFs (reference 3 and Fig. S1), RIP mediates survival signals in LPS-stimulated splenocytes independently of NFκB and that NFκB activation is not sufficient to promote the survival of LPS-stimulated B cells.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis and expression of Akt after LPS stimulation of splenocytes from RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups and RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− littermates. (A) Annexin V–FITC and B220-PE staining at 0, 16, and 96 h of splenocytes cultured with medium or LPS. Analysis was performed by gating on B220+ cells. Similar results were obtained in two separate experiments. (B) Akt, IκB, and p38 phosphorylation after stimulation of RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− and RIP−/+/TNFR1−/− splenocytes with LPS (n = 4) or CpG ODN 1826 (n = 2). Lysates were probed with Akt as loading control. (C) Fold induction of Akt, IκB, and p38 phosphorylation after LPS stimulation (n = 4) *P < 0.05.

RIP Is Important for Akt Phosphorylation After TLR4 Signaling.

Phosphatidylinositol (PI)3 kinase is activated after TLR4 signaling, leading to the phosphorylation and activation of Akt, which plays an important role in B cell survival (26). More importantly, p85α-deficient B cells have impaired proliferation and increased apoptosis after LPS stimulation (27). We used a phosphospecific antibody to examine Akt phosphorylation after LPS stimulation in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− splenocytes and control RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− splenocytes. LPS stimulation caused Akt phosphorylation in RIP+/+/TNFR1−/− splenocytes. In contrast, LPS induced virtually no Akt phosphorylation in RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− splenocytes (Fig. 3, B and C; n = 4). The decrease in Akt phosphorylation was specific because LPS induced normal phosphorylation of IκB and p38 in these cells (Fig. 3, B and C; n = 4). RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− splenocytes also had severely impaired Akt phosphorylation after CpG stimulation, but CpG induced IκB and p38 phosphorylation in these cells (Fig. 3 B; n = 2). These results suggest that RIP links TLR4 and TLR9 signaling to PI3 kinase activation. Analysis of Akt phosphorylation in subpopulations of purified cells was precluded by the decreased splenic cellularity and young age of RIP−/−/TNFR1−/− pups.

LPS-induced PI3 kinase activation is dependent on TAK1 (28), which interacts with RIP (29). Our data suggests that RIP is essential for TAK1-dependent TLR4 and TLR9 activation of PI3 kinase. The role of RIP in Akt activation by other TLR ligands and the exact molecular link between RIP and Akt remain to be elucidated. Although our data on splenocytes and MEFs suggests that RIP is not essential for TLR4 activation of NFκB, recent work indicates that RIP interacts with TRIF and is important for NFκB activation by TLR3 (30), as it is for NFκB activation by TNFR1. This suggests that RIP plays different roles in signaling by individual TLRs.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank S. Brodeur, H. Jabara, E. Castigli, P. Bryce, A.G. Ugazio, and M. Castello for their invaluable help.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI31136 and by a grant from the March of Dimes.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Stanger, B.Z., P. Leder, T.H. Lee, E. Kim, and B. Seed. 1995. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell. 81:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu, Z.G., H. Hsu, D.V. Goeddel, and M. Karin. 1996. Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-kappaB activation prevents cell death. Cell. 87:565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelliher, M.A., S. Grimm, Y. Ishida, F. Kuo, B.Z. Stanger, and P. Leder. 1998. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 8:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, S.Q., A. Kovalenko, G. Cantarella, and D. Wallach. 2000. Recruitment of the IKK signalosome to the p55 TNF receptor: RIP and A20 bind to NEMO (IKKgamma) upon receptor stimulation. Immunity. 12:301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanz, L., M.T. Diaz-Meco, H. Nakano, and J. Moscat. 2000. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J. 19:1576–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cusson, N., S. Oikemus, E.D. Kilpatrick, L. Cunningham, and M. Kelliher. 2002. The death domain kinase RIP protects thymocytes from tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2-induced cell death. J. Exp. Med. 196:15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manis, J.P., M. Tian, and F.W. Alt. 2002. Mechanism and control of class-switch recombination. Trends Immunol. 23:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabara, H., D. Laouini, E. Tsitsikov, E. Mizoguchi, A. Bhan, E. Castigli, F. Dedeoglu, V. Pivniouk, S. Brodeur, and R. Geha. 2002. The binding site for TRAF2 and TRAF3 but not for TRAF6 is essential for CD40-mediated immunoglobulin class switching. Immunity. 17:265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahonen, C., E. Manning, L.D. Erickson, B. O'Connor, E.F. Lind, S.S. Pullen, M.R. Kehry, and R.J. Noelle. 2002. The CD40-TRAF6 axis controls affinity maturation and the generation of long-lived plasma cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda, K., and S. Akira. 2003. Toll receptors and pathogen resistance. Cell. Microbiol. 5:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai, T., O. Adachi, T. Ogawa, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 11:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto, M., S. Sato, H. Hemmi, K. Hoshino, T. Kaisho, H. Sanjo, O. Takeuchi, M. Sugiyama, M. Okabe, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2003. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 301:640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato, S., M. Sugiyama, M. Yamamoto, Y. Watanabe, T. Kawai, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2003. Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta (TRIF) associates with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and TANK-binding kinase 1, and activates two distinct transcription factors, NF-kappa B and IFN-regulatory factor-3, in the Toll-like receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 171:4304–4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi, K., N. Inohara, L.D. Hernandez, J.E. Galan, G. Nunez, C.A. Janeway, R. Medzhitov, and R.A. Flavell. 2002. RICK/Rip2/CARDIAK mediates signalling for receptors of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Nature. 416:194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin, A.I., P.W. Dempsey, K. Bruhn, J.F. Miller, Y. Xu, and G. Cheng. 2002. Involvement of receptor-interacting protein 2 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nature. 416:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton, K., X. Sun, and V.M. Dixit. 2004. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1464–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cariappa, A., L. Chen, K. Haider, M. Tang, E. Nebelitskiy, S.T. Moran, and S. Pillai. 2003. A catalytically inactive form of protein kinase C-associated kinase/receptor interacting protein 4, a protein kinase C beta-associated kinase that mediates NF-kappa B activation, interferes with early B cell development. J. Immunol. 171:1875–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagai, Y., S. Akashi, M. Nagafuku, M. Ogata, Y. Iwakura, S. Akira, T. Kitamura, A. Kosugi, M. Kimoto, and K. Miyake. 2002. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat. Immunol. 3:667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaffl, M.W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Hir, M., H. Bluethmann, M.H. Kosco-Vilbois, M. Muller, F. di Padova, M. Moore, B. Ryffel, and H.P. Eugster. 1996. Differentiation of follicular dendritic cells and full antibody responses require tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 183:2367–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieg, A.M., A.K. Yi, S. Matson, T.J. Waldschmidt, G.A. Bishop, R. Teasdale, G.A. Koretzky, and D.M. Klinman. 1995. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 374:546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deenick, E.K., J. Hasbold, and P.D. Hodgkin. 1999. Switching to IgG3, IgG2b, and IgA is division linked and independent, revealing a stochastic framework for describing differentiation. J. Immunol. 163:4707–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 109:S81–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop, G.A., and B.S. Hostager. 2001. Signaling by CD40 and its mimics in B cell activation. Immunol. Res. 24:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoebe, K., E.M. Janssen, S.O. Kim, L. Alexopoulou, R.A. Flavell, J. Han, and B. Beutler. 2003. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat. Immunol. 4:1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venkataraman, C., G. Shankar, G. Sen, and S. Bondada. 1999. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induced B cell activation is mediated via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dependent signaling pathway. Immunol. Lett. 69:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fruman, D.A., S.B. Snapper, C.M. Yballe, L. Davidson, J.Y. Yu, F.W. Alt, and L.C. Cantley. 1999. Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85alpha. Science. 283:393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irie, T., T. Muta, and K. Takeshige. 2000. TAK1 mediates an activation signal from toll-like receptor(s) to nuclear factor-kappaB in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. FEBS Lett. 467:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han, K.J., X. Su, L.G. Xu, L.H. Bin, J. Zhang, and H.B. Shu. 2004. Mechanisms of TRIF-induced ISRE and NF-kappa B activation and apoptosis pathways. J Biol Chem. 279:15652–12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meylan, E., K. Burns, K. Hofmann, V. Blancheteau, F. Martinon, M. Kelliher, and J. Tschopp. 2004. RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat. Immunol. 5:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]