Abstract

Antibody class switching is mediated by somatic recombination between switch regions of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene locus. Targeting of recombination to particular switch regions is strictly regulated by cytokines through the induction of switch transcripts starting 5′ of the repetitive switch regions. However, switch transcription as such is not sufficient to target switch recombination. This has been shown in mutant mice, in which the I-exon and its promoter upstream of the switch region were replaced with heterologous promoters. Here we show that, in the murine germline targeted replacement of the endogenous γ1 promoter, I-exon, and I-exon splice donor site by heterologous promoter and splice donor sites directs switch recombination in activated B lymphocytes constitutively to the γ1 switch region. In contrast, switch recombination to IgG1 is inhibited in mutant mice, in which the replacement does not include the heterologous splice donor site. Our data unequivocally demonstrate that targeting of switch recombination to IgG1 in vivo requires processing of the Iγ1 switch transcripts. Either the processing machinery or the processed transcripts are involved in class switch recombination.

Keywords: class switch, recombination, splicing, switch transcript, B lymphocytes

Bcells can exchange, by immunoglobulin class switch recombination, the isotype of the antibody they express during an immune response. Upon activation, gene segments of a particular constant region (CH) are fused to the variable region exons of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) gene. This DNA recombination occurs between switch (s) regions located upstream of each constant region gene (for review see references 1–3).

Switch recombination is directed to particular Ig classes by cytokines (for review see reference 4) which induce transcripts of individual unrearranged switch regions, the switch transcripts, before recombination (5–8). A common switch recombinase machinery may then recognize the committed heavy-chain gene segments. Targeting of class switch recombination becomes independent of cytokines if the promoter of a particular unrearranged IgH gene segment is replaced by a constitutively active promoter (7, 8).

Switch transcription initiates from the IH-exon, located upstream of the switch regions, and proceeds through the switch region and the CH exons. The switch region and the CH introns are spliced out of the switch transcript pre-mRNA.

Little is known about the mechanism by which these switch transcripts control class switch recombination. Neither the process of switch transcription alone nor the production of a stable transcript is sufficient to direct switch recombination (7–10). Switch transcripts seem not to encode for polypeptides involved in recombination.

It has been suggested that in addition to transcription, the processing of switch transcripts might be necessary for class switch recombination (7, 8). In mice that lack a 114-bp fragment spanning the 3′ part of the Iγ1-exon and the 5′ part of the sγ1 region, including the splice donor site, class switch to IgG1 was abolished, whereas the switch transcription, driven by the human metallothionein (hMT) promoter, was not affected. This result led to speculations on the relevance of the splice donor site. However, an alternative explanation for this finding could be the presence of a recombination control element within the 114-bp fragment.

To clarify the relevance of the endogenous Iγ1-exon splice donor site for switch recombination, we describe here the targeted replacement of the entire endogenous Iγ1-exon by an artificial I-exon and an adenoviral (Ad) splice donor site. We show unambiguously that processing of switch transcripts, or the processed switch transcripts themselves, are required for switch recombination.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice used in this study were bred and kept in the animal facility of the Institute of Genetics (University of Cologne, Germany). CD1 female mice for preparation of morulae were obtained from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with institutional and state guidelines.

Construction of the Ad-hMT Gene-targeting Vector.

We amplified the Ad splice donor site as an XhoI fragment (sequence data are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession number X02996, positions 6062 to 6241) from the plasmid pH3E-5 (a gift from Dr. K. Hilger-Eversheim, Institute of Genetics), containing the Ad type V–HindIII E insert cloned into the HindIII site of pBR322. The splice donor fragment contained 28 nucleotides of the first exon of the tripartide leader from the Ad-major–late region (11), plus 151 nucleotides of the first intervening sequence (12). The Ad-hMT vector has been constructed by cloning the XhoI fragment of the Ad splice donor site into the SalI site of the hMT targeting vector directly downstream of the neomycin resistance gene (neo)–hMT promoter cassette, which includes a bacterial sequence replacing the Iγ1-exon. The hMT vector has been described in detail (7). The Ad-hMT construct consisted of an 8-kb homologous sequence to the 5′sγ1 region, the replacement cassette containing neo in reverse orientation, the hMT promoter, a bacterial sequence, and the Ad splice donor site, and 0.8-kb homology to the sγ1 region. A thymidine kinase gene (TK) for negative selection was introduced at the 5′ end of the construct.

Generation and Screening of Homologous Recombinant Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell Clones.

The NotI linearized Ad-hMT vector was transfected into 129/Ola derived E14-1 ES cells (13). ES cells were cultured on primary embryonic fibroblasts and manipulated as described in Torres and Kühn (14). Homologous recombinant ES clones were identified by Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and hybridized with the external 9-kb SspI-EcoRI fragment of the γ1 switch region (15). Homologous recombinant clones were confirmed by digestion with KpnI hybridizing with a 1,550-bp XhoI-EcoRV neomycin probe from pFRT2neo (9).

Generation of Targeted Ad-hMT Mice.

A correctly targeted ES cell clone was aggregated with CD1 morulae prepared from 6-wk-old superovulated mice and implanted into foster mothers as described previously (14). Male chimeric mice were crossed to female C57BL/6 mice to obtain heterozygous mutant mice. Offspring were analyzed for transmission of targeted and wild-type IgH alleles by PCR using as the 5′ primer 5′-TAGTCCCTGCCTTTGCTCTG-3′ (primer 1) and, for the Ad-hMT allele, the 3′ primer 5′-ATCGCCTTCTTGACGAGTTC-3′ (primer 2), and, for the wild-type allele, the 3′ primer 5′-GCCTCGTCAGAAAGATTGGT-3′ (primer 3). Homozygous mice were generated by intercross.

Analysis of IgG1 Serum Titers and Cytometric Analysis of LPS-stimulated Splenic B Cells.

Serum concentrations of IgG1a and total IgG1 of unimmunized mice were determined by allotype-specific ELISA as described (13). The frequency of IgG1 class switch was assayed by flow cytometric analysis of LPS- (Sigma Chemical Co., Steinheim, Germany) activated splenic B cells in vitro. Resting B cells were obtained by depletion of CD43+ cells from spleen cells prepared from 8–12-wk-old mice using anti-CD43 microbeads and high-gradient magnetic cell separation (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The efficiency of depletion was controlled by flow cytometric analysis with anti-CD43 antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec). B cells were cultured in RPMI, 10% FCS, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM glutamin, and 10 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin in a concentration of 106 cells/ml and stimulated on day 0 either with LPS alone (40 μg/ml) or with LPS and recombinant murine IL-4 (5 ng/ml; Genzyme Corp., Cambridge, MA). Cells were harvested on day 5, fixed in formaldehyde (2%; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), permeabilized by saponin (0.5%, Sigma Chemical Co.), (16), and stained for cytoplasmic IgG1 with digoxigenized monoclonal rat anti–mouse IgG1 (0.5 μg/ml; gift from Miltenyi Biotec) and antidigoxigenin (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) conjugated to Cy5 (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany). Cytometric analysis was performed using a FACScan® (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Results

Generation of Ad-hMT Targeted Mice.

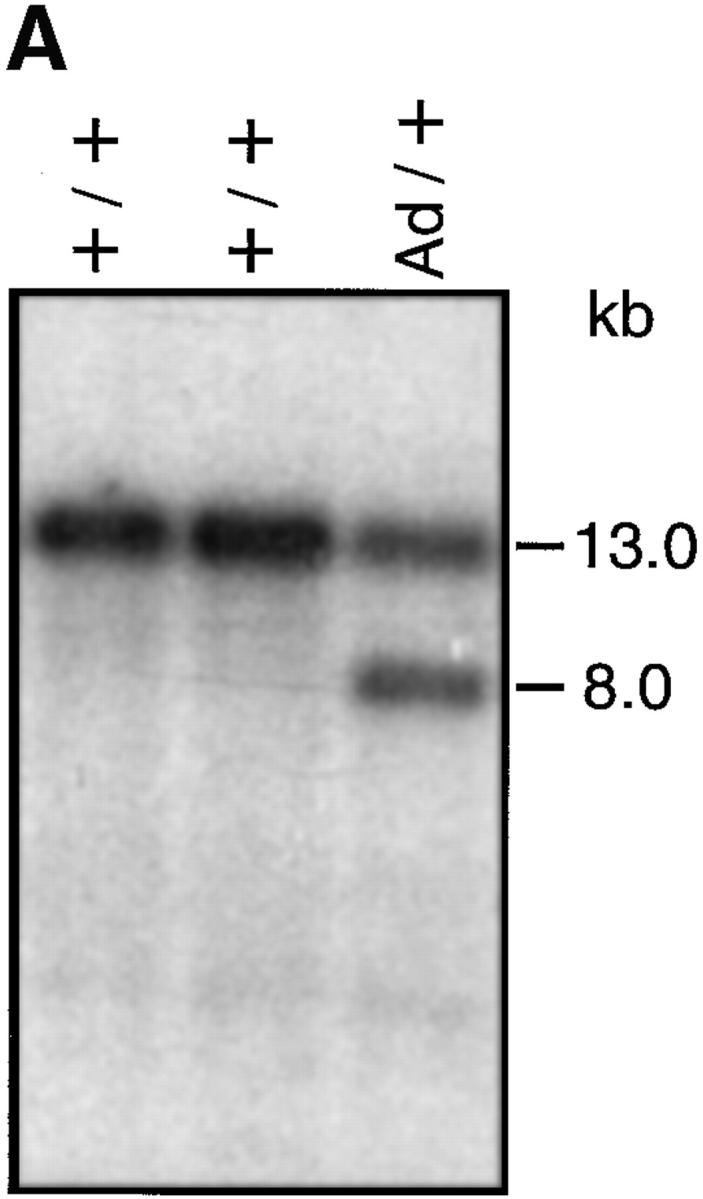

For the genetic modification of the IgG1 locus, we constructed an Ad-hMT targeting vector (Fig. 1 A). It contained a heterologous splice donor site inserted into the SalI site directly 3′ of the neo–hMT promoter cassette of the targeting vector, which we originally used to generate the hMT mutant mice as described previously (7). We chose an 179-bp fragment from Ad type V, which contains all cis elements needed for efficient splicing, and a 9-bp splice donor site (12). No coding sequence is present in this fragment. Both the sequence of the Ad splice donor site (GGG GTAGT) as well as the sequence of the endogenous γ1 splice donor site (GCG GTAAGT) are 78% homologous to the consensus sequence (17). The resulting Ad-hMT construct (Fig. 1 A) was targeted into wild-type E14-1 ES cells derived from 129/Ola mice (IgHa). Homologous integration was confirmed by Southern hybridization (Fig. 2 A, and data not shown). In the mutant Ad-hMT IgH locus the endogenous 1.7-kb 5′sγ1 region containing the γ1 promoter and the Iγ1-exon is replaced by an inversely oriented neo, the hMT promoter, a bacterial sequence replacing the I-exon and the Ad splice donor site. The correct insertion of the Ad splice donor site in the targeted ES cell clone was verified by sequencing. Thus, Ad-hMT mice and hMT mice differ only in the presence of the Ad splice donor site (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

Targeting of the murine γ1 wild-type locus using a modified hMT vector with an inserted Ad splice donor site (Ad-5′ss). (A) Genomic organization of the murine IgG1 wild-type locus, the targeting vector, and the targeted Ad-hMT allele. The sγ1 probe used for Southern screening of homologous recombinant ES cell clones is represented as a black bar. Filled triangles indicate the primers used for screening of chimeric offspring. H, HindIII; E, EcoRI; Sc, ScaI; Amp, ampicillin resistance gene; TK, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene; neo, neomycin resistance gene. (B) Detail of the γ1 wild-type and Ad-hMT targeted alleles. The genomic structure is compared with the hMT and s-hMT targeted loci (7). Sequences introduced by targeting vectors are shown in white: neo gene (neo), hMT promoter (hMT), artificial IhMT exon (IhMT); or in black: Ad splice donor site (Ad). The 114-bp fragment of wild-type sequence is represented as a hatched box. The phenotype of the mice is indicated with respect to transcription (transcription), splicing of the transcripts (processed transcripts), and class switch to IgG1 (class switch).

Figure 2.

(A) Analysis of homologous recombinant ES cell clones by Southern blot using an sγ1 probe. EcoRI digestion of genomic DNA yielded fragment sizes of 13.0 and 8.0 kb of the wild-type (+) and Ad-hMT (Ad) alleles, respectively. (B) Analysis of heterozygous and homozygous targeted mice and C57BL/6 wild-type littermates. Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products of tail DNA amplified with primers 1, 2, and 3.

We generated nine chimeric mice by aggregation of one ES cell clone with morulae prepared from female mice of the CD1 outbred strain. Heterozygous targeted mice were obtained by crossing the chimeras with C57BL/6 (IgHb). Heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice were identified by PCR of genomic DNA from tail biopsies using primers 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 2 B). The effect of the inserted splice donor site on IgG1 class switching was analyzed in mice heterozygous and homozygous for the mutation.

Mutant Ad-hMT Mice Produce Normal Titers of IgG1 In Vivo.

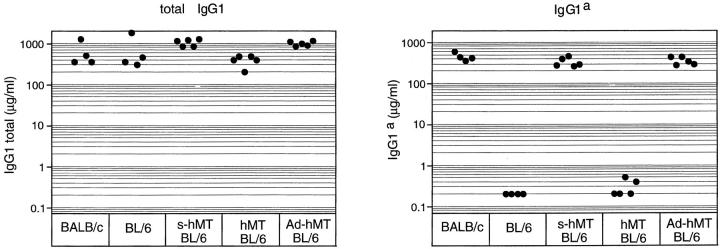

To analyze IgG1 class switching in vivo we measured the IgG1 titer in IgHAd-hMT/b mice by an allotype-specific ELISA. Since the C57BL/6 IgH allotype produces IgG1 of the b haplotype, analysis of the IgG1a titer directly determines the IgG1 level produced from the 129/Ola derived targeted Ad-hMT alleles (IgHa). In IgHAd-hMT/b mice, serum IgG1a concentrations were ∼1,000-fold above the titers of IgHhMT/b mice, which show a constitutive transcription of the IgG1a locus but lack the 114-bp endogenous fragment (Fig. 3). Titers comparable to IgHAd-hMT/b mice (mean, 365 μg/ml) were detected in sera of IgHs-hMT/b mice, which have retained the 114 bp of endogenous sequence (mean, 340 μg/ml) and in BALB/c mice (IgHa/a, mean, 453 μg/ml). IgHhMT/b mice produce very low levels of serum IgG1a (mean 0.4 μg/ml), whereas in C57BL/6 wild-type mice (IgHb/b) serum IgG1a was not detectable (<0.2 μg/ml). All animals had comparable titers of total IgG1 (IgG1a plus IgG1b).

Figure 3.

In vivo analysis of IgG1 production in heterozygous targeted F1 and wild-type control mice. Immunoglobulin levels of IgG1a and of total IgG1 (IgG1a and IgG1b) were determined in sera of 8–12-wk-old mice by ELISA. The detection limit was 0.2 μg/ml.

IgG1 Switch Frequency of Activated B Cells in Ad-hMT Mice.

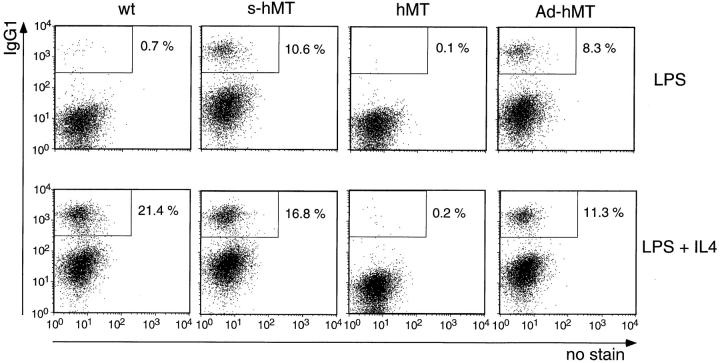

For the analysis of IgG1 class switching of B lymphocytes in vitro, we isolated resting B cells from homozygous Ad-hMT mice (IgHAd-hMT/Ad-hMT) and wild-type littermate controls by depletion of CD43+ cells from spleen. 99% pure CD43−, resting B cells were stimulated with LPS or with LPS and IL-4. On day 5, activated B cells were stained intracellularly for expression of IgG1 (Fig. 4). As expected, B cells from wild-type mice switched to expression of IgG1 only in the presence of LPS and IL-4. Due to constitutive activity of the hMT promoter in the targeted mice, recombination to sγ1 is independent of IL-4. Thus, differences between the various targeted alleles became evident in B cells stimulated only with LPS. IgHAd-hMT/Ad-hMT B cells, stimulated with LPS, switched to IgG1 at frequencies comparable to IgHs-hMT/s-hMT B cells (8.3% vs. 10.6%), whereas IgHhMT/hMT B cells did not switch to IgG1 at all (<0.1%). In the presence of LPS plus IL-4, the frequency of switched cells from IgHAd-hMT/Ad-hMT mice and IgHs-hMT/s-hMT mice was enhanced by a factor of 1.4 and 1.6, respectively, as compared to the cultures with LPS alone. This effect is probably due to the stronger proliferative induction of stimulated B cells by IL-4.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of LPS-stimulated splenic B cells of pooled homozygous targeted mice and their wild-type littermates. By depletion of CD43+ spleen cells using the MACS system, resting B cells (CD43−) were isolated and cultured with LPS or with LPS + IL-4. After 5 d cells were fixed and stained intracellularly for expression of IgG1. Due to constitutive activity of the hMT promoter, class switch to IgG1 is independent of IL-4 in B cells from targeted mice. A representative example of two independent experiments is shown. (Note that in all cultures with IgG1 switched B cells, there is a basal level staining of all B cells for IgG1, probably due to Fc-γR bound IgG1 on the surface.)

We conclude that processing of the Iγ1 switch transcripts is required for class switching to IgG1 in vivo and in vitro.

Discussion

Recent studies have suggested that in addition to transcription, processing of switch transcripts may be required to induce recombination of the corresponding switch region (7, 8). We have shown previously that a 114-bp fragment of Iγ1 wild-type sequence is necessary to target switch recombination to IgG1 (Fig. 1 B; 7). Whether the 114-bp fragment is required as a splice donor site, a recombination control element, or a transcriptional enhancer has not been clear so far.

In this study, we demonstrate unequivocally that it is the splice donor element which is required to target switch recombination to the sγ1 region in vivo. In mutant Ad-hMT mice, which contained an Ad splice donor site replacing the 114-bp fragment, serum concentrations of IgG1 were at the same level as in wild-type mice. In contrast, serum concentrations of IgG1 were reduced about three orders of magnitude in hMT mice (Fig. 1 B) lacking the Iγ1 splice donor site.

At first glance, our results contradict experiments published recently by Harriman et al. (8), who replaced the Iα promoter by the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter and the entire sequence of the Iα-exon by a human hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (hHPRT) minigene. Despite the deletion of the endogenous Iα splice donor site, mutant mice produce normal titers of IgA in the serum. sα switch recombination in these mice might be due to splicing within the intron of the hHPRT minigene 5′ of the α switch region, as suggested by the authors. However, the data also do not exclude splicing of primary transcripts between the splice donor site of the hHPRT minigene and the splice acceptor of the first Cα-exon, resulting in a situation comparable to B cells from Ad-hMT mice or wild-type B cells. In another study, deletion of the entire Iε-exon without replacement by splice signals nearly but not completely abolishes class switch recombination to Igε (10). Again, the residual frequency of switch recombination to Igε could be explained by alternative splicing between cryptic splice sites and Cε, which may occur according to the data shown by the authors.

Our data clearly show that processing of switch transcripts is required for targeting of switch recombination in vivo. This argues against the original idea that switch transcription as such may simply improve accessibility of switch regions for the action of a switch recombinase (5, 18, and for review see reference 4).

A different picture arises from experiments using extrachromosomal or integrated switch recombination substrates in vitro (19–23). In all systems recombination between switch regions can be detected without active transcription. Some switch plasmids undergo recombination at high frequencies only if they are transcribed (24, 25). A requirement for splicing of those plasmid transcripts has not been described so far. However, in our own experiments, we have observed that the switch recombination frequency could be increased more than twofold on transcribed extrachromosomal switch substrates, transfected into activated, primary B cells if the plasmid transcripts are spliced (Petry, K., G. Siebenkotten, R. Christine, and A. Radbruch, manuscript submitted for publication). This suggests that a basic recombination frequency of extrachromosomal switch substrates may be due to recombination machines other than the switch recombinases, but for switch recombination, transcription and splicing of transcripts may be required.

Our study does not answer the question of how switch transcripts are involved in the process of switch recombination. An attractive idea is that the spliced switch transcripts or the spliced intronic switch regions would interact with the recombination machinery. Either in trans, as a component of the switch recombinase, or in cis, rehybridizing with the DNA template, thus stabilizing an RNA–DNA triple helix which then could be recognized by the recombination machinery. This idea is supported by findings that transcription of G-rich regions, present in switch regions or in mitochondrial DNA of yeast, can generate stable RNA–DNA hybrids in vitro (23, 26, 27). Proteins with RNA- as well as DNA-binding domains have been shown recently to be involved in the recombination of switch substrates (28).

An alternative hypothesis would be that components of the spliceosome are required for the process of recombination. Nucleophosmin and nucleolin, two of the identified components of the recently described switch region transfer activity (28) have been shown to be also involved in the processing of ribosomal RNA in the nucleolus (29, 30), which is dependent on the presence of small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins (snoRNPs) (31).

The link between splicing and recombination has been documented recently also in other transcription-based recombination systems such as the integration of yeast intron RNA into DNA via reverse splicing and the involvement of genes in double strand formation during the meiotic recombination and in RNA splicing in yeast (32, 33). The common basic chemistry involved in splicing of RNA and in recombination of DNA supports the upcoming idea that splicing may have more potential than only to process RNA.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kristina Hilger-Eversheim for generously providing us with the plasmid pH3E-5, to Ralf Kühn for the E14-1 ES cell line, to Klaus Rajewsky and other members of the ES cell club, especially to Thorsten Buch and Manfred Kraus, for advice, to Anke Roth and Angela Egert for technical support, and to Max Löhning for the critical reading of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Lorenz M, Radbruch A. Developmental and molecular regulation of immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;217:151–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-50140-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stavnezer J. Antibody class switching. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:79–146. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60866-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snapper CM, Marcu KB, Zelazowski P. The immunoglobulin class switch: beyond accessibility. Immunity. 1997;6:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snapper, C.M., and F.D. Finkelmann. 1998. Immunoglobulin class switching. In Fundamental Immunology. W.E. Paul, editor. 4th ed. Raven Press, New York. 831–861.

- 5.Stavnezer-Nordgren J, Sirlin S. Specificity of immunoglobulin heavy chain switch correlates with activity of germline heavy chain genes prior to switching. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1986;5:95–102. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esser C, Radbruch A. Rapid induction of transcription of unrearranged S gamma 1 switch regions in activated murine B cells by interleukin 4. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1989;8:483–488. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz M, Jung S, Radbruch A. Switch transcripts in immunoglobulin class switching. Science. 1995;267:1825–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7892607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harriman GR, Bradley A, Das S, Rogers-Fani P, Davis AC. IgA class switch in Iα exon–deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:477–485. doi: 10.1172/JCI118438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung S, Rajewsky K, Radbruch A. Shutdown of class switch recombination by deletion of a switch region control element. Science. 1993;259:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.8438159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottaro A, Lansford R, Xu L, Zhang J, Rothman P, Alt FW. I region transcription (per se) promotes basal IgE class switch recombination but additional factors regulate the efficiency of the process. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1994;13:665–674. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nevins JR. Regulation of early adenovirus gene expression. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:419–430. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.419-430.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang MTF, Gorman CM. Intervening sequences increase efficiency of RNA 3′ processing and accumulation of cytoplasmic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:937–947. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres, R.M., and R. Kühn. 1997. Laboratory protocols for conditional gene targeting. Oxford University Press, London.

- 15.Mowatt MR, Dunnick WA. DNA sequence of the murine γ1 switch segment reveals novel structural elements. J Immunol. 1986;136:2674–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assenmacher M, Schmitz J, Radbruch A. Flow cytometric determination of cytokines in activated murine T helper lymphocytes: expression of interleukin 10 in interferon-γ and in interleukin-4 expressing cells. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1097–1101. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MR. Biochemical mechanisms of constitutive and regulated pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alt FW, Blackwell TK, DePinho RA, Reth MG, Yancopoulus GD. Regulation of genome rearrangement events during lymphocyte differentiation. Immunol Rev. 1986;89:5–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1986.tb01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ott DE, Alt FW, Marcu KB. Immunoglobulin heavy chain switch region recombination within a retroviral vector in murine pre-B cells. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1987;6:577–584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott DE, Marcu KB. Molecular requirements for immunoglobulin heavy chain constant region gene switch–recombination revealed with switch-substrate retroviruses. Int Immunol. 1989;1:582–591. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung H, Maizels N. Transcriptional regulatory elements stimulate recombination in extrachromosomal substrates carrying immunoglobulin switch–region sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4154–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepse CL, Kumar R, Ganea D. Extrachromosomal eukaryotic DNA substrates for switch recombination: analysis of isotype and cell specificity. DNA Cell Biol. 1994;13:1151–1161. doi: 10.1089/dna.1994.13.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels GA, Lieber MR. RNA:DNA complex formation upon transcription of immunoglobulin switch regions: implications for the mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5006–5011. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung H, Maizels N. Regulation and targeting of recombination in extrachromosomal substrates carrying immunoglobulin switch region sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1450–1458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniels GA, Lieber MR. Strand specificity in the transcriptional targeting of recombination at immunoglobulin switch sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5625–5629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu B, Clayton DA. A persistent RNA–DNA hybrid is formed during transcription at a phylogenetically conserved mitochondrial DNA sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:580–589. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reaban ME, Griffin JA. Induction of RNA-stabilized DNA conformers by transcription of an immunoglobulin switch region. Nature. 1990;348:342–344. doi: 10.1038/348342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borggrefe T, Wabl M, Akhmedov AT, Jessberger R. A B cell-specific DNA recombination complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17025–17035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrera JE, Savkur R, Olson MO. The ribonuclease activity of nucleolar protein B23. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3974–3979. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.19.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginisty H, Amalric F, Bouvet P. Nucleolin functions in the first step of ribosomal RNA processing. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1998;17:1476–1486. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abou Elela, S., H. Igel, and M. Ares. RNAse III cleaves eukaryotic pre-ribosomal RNA at a U3 snoRNP- dependent site. Cell. 1996;85:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Zimmerly S, Perlman PS, Lambowitz AM. Efficient integration of an intron RNA into double-stranded DNA by reverse splicing. Nature. 1996;381:332–335. doi: 10.1038/381332a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa H, Johzuka K, Nakagawa T, Leem SH, Hagihara AH. Functions of the yeast meiotic recombination genes, MRE11 and MRE2. Adv Biophys. 1995;31:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(95)99383-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]