Abstract

Two new types of boronate affinity solid phases were synthesized and characterized. The materials were prepared by silylation of porous silica gel with monochlorosilane derivatives containing synthetic sulfonyl- and sulfonamide-substituted phenylboronic acids. The new solid phases were evaluated for boronate affinity chromatography with aryl and alkyl cis-diol compounds, and found suitable for the retention of cis-diols under acidic conditions. Significant correlations between the retention factor (K) and the pH of the mobile phase demonstrate that the binding of cis-diols to the solid phases is best rationalized by chelation. Based on the low ionization constant, caused by the electron-withdrawing effects of the sulfonyl and sulfonamide groups, these media display an enhanced affinity for cis-diols as compared to unsubstituted phenylboronic acid. Utilizing Isocratic elution, a mixture of various biologically relevant L-tyrosines, L-DOPA and several catecholamines were resolved with a mobile phase composed of 0.05 M, pH5.5 phosphate buffer. Mono-, di- and triphosphates of adenosine were also separated at pH 6.0. Hence, the new boronate solid phase offers efficient affinity separation and purification of cis-diol containg molecules under rather mild pH regions.

Keywords: Boronate affinity, sulfonyl- and sulfonamide-phenylboronic acid, liquid chromatography

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that cis-diol containing compounds can reversibly form cyclic complexes with boronate ions in aqueous solution. The pH-dependent boronate binding has been developed as a specific affinity chromatographic technique for the selective separation of cis-diol containing biomolecules such as catechols, nucleotides, nucleosides, carbohydrates, glycoproteins and some enzymes [1-8]. One problem encountered in the application of boronate affinity chromatography is the requirement of slightly alkaline pH. In fact, the phenylboronic acid ligands commonly used for boronate phases, possess a relatively low ionization constant (pKa ~ 8.8), limiting their use for affinity chromatography under neutral conditions. Several analytes, such as catechols, are unstable under alkaline conditions [9]. To overcome this problem, several attempts have been made to lower the boronate pKa by introducing electron-withdrawing groups into the phenyl ring of phenylboronic acid. Among them are carboxyl- and nitro- substituted phenylboronic acids [10, 11]. The electron-withdrawing effect of the carboxyl group is relatively weak, and the boronate pKa of the 4-carboxyl-phenylboronic acid is approximately 8.0. The nitro group is more effective and can lower the boronate pKa of phenylboronic acid to 7.1. However, the use of the nitro-substituted phenylboronic acids is problematic due to hydrolytic deboronation [12] and their sensitivity towards light.

Affinity chromatography has grown rapidly as a complementary method for multidimensional separations in proteomics [3, 13]. Specifically for the enrichment of L-DOPA-containing peptides, a boronic acid phase effectively operating at pH < 7 would be desirable in order to avoid adventitious oxidation of the analytes on column. L-DOPA represents a common hydroxylation product of tyrosine under condition of oxidative stress [14]. In order to assess the biological significance of DOPA formation, the respective target proteins as well as target sequences on these proteins must be known. Boronate affinity chromatography would be the ideal first step towards the enrichment of DOPA-containing peptides from the DOPA-containing subproteome. As a step towards the rational design of boronate affinity phase with pKa’s near or below neutrality, we chose to synthesize sulfonyl- and sulfonamide substituted phenylboronic acids as ligands for immobilization on a solid phase. While sulfonamide phenylboronic acids have attracted attention as recognition moieties of sensors for sugars [15], sulfonyl- and sulfonamide-phenylboronic acids immobilized for affinity chromatography have not been reported. In this paper, we present the synthesis of the sulfonyl- and sulfonamide-phenylboronic acid ligands and their immobilization on porous silica gels by silylation. The physical-chemical properties of the ligands are characterized, and the affinity chromatography of the new solid phases is evaluated on the basis of the retention behavior of aryl and alkyl cis-diols.

Materials and Methods

General

The liquid chromatography system consisted of two Shimadzu LC-6A pumps, a Rheodyne 7413 injector equipped with a 20 μl loop, and a variable-wavelength UV detector. The column was a 50 × 4.6 (i.d.) mm stainless steel cylinder, packed with synthetic silica gels as described below. NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer and chemical shifts were calibrated with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. IR spectra were recorded on a Perking-Elmer infrared spectrophotometer. Melting points were determined on an Electrothermal® Melting Point apparatus (values are uncorrected).

Porous silica (Nucleosil 100-5, 5 μm, 100 Å) was obtained from Marcherey-Nagel, Düren, and dried for 2 days at 140°C before use. Tetrahydrofuran and toluene were distilled from Na/benzophone prior to use [Na/benzophone must be handled with the appropriate precautions]. Other solvents were of HPLC grade purity. 4-Bromobenzenesulfonyl chloride, allylamine, triisopropyl borate, 1.6 M n-butyllithium in hexane, N-methyl-diethanolamine, hexachloroplatinic acid and dimethylchlorosilane were from Aldrich and used as received unless otherwise indicated. Analytes including L-tyrosine, 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylanine (L-DOPA), 3-amino-L-tyrosine, (-)-epinephrine, (-)-norepinephrine, mono-, di- and tri-phosphates of adenosine, and uridine were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and were used without further purification.

Tyrosinase-catalyzed hydroxylation of angiotensin I

DOPA-containing angiotensin I peptide was used to evaluate the enrichment of a DOPA-containing peptide by the synthetic boronate affinity solid phases. The peptide was obtained by tyrosinase-catalyzed hydroxylation of angiotensin I (DRVYIHPFHL) (Bachem; MW = 1296.5) according to a published procedure [24]. Briefly, 1 mg angiotensin I was dissolved at room temperature in 1.0 mL of 100 mM phosphate by the pH 7.4 containing 25 mM ascorbic acid, to which 50 μg tyrosinase (Aldrich, 1,530 units/mg solid) was added. The mixture was constantly aerated and vortexed and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h, and terminated by addition of 10 uL 6 N HCl. The reaction mixture was stored in the refrigerator before use.

Synthesis of 4-(N-allylsulfamoyl)phenylboronic acid 3

To a stirred solution of 4-bromobenzenesulfonyl chloride 1 (12.8 g, 50 mmol) (Scheme 1) and 5 ml of triethylamine in a total volume of 100 ml acetonitrile in an ice-bath was slowly added 10 ml of allylamine. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 50 ml of chloroform, washed with water and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford pale yellow solids. The solid compound was recrystallized from a mixture of ethanol and water to give 12.4 g (90% yield) of the pure N-allyl-4-bromobenzenesulfonamide 2 as colorless crystals: mp 58-60°C; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ7.75 (d, 2H), 7.66 (d, 2H), 5.72 (m, 1H), 5.19 (q, 2H), 5.08 (q, 2H), 3.62 (d, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ139.8, 132.7, 132.4, 128.7, 127.6, 117.9, 45.7.

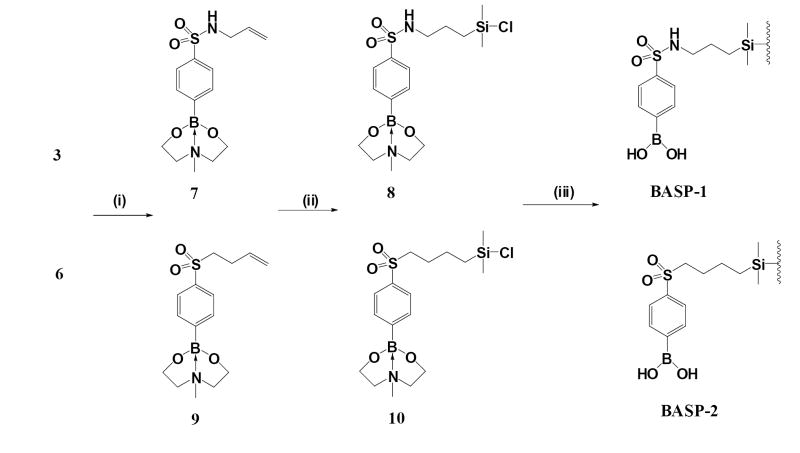

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of sulfonyl and sulfonamide-substituted phenylboronic acids. Reagents and conditions: (i) Allylamine, TEA, acetonitrile; (ii) 1. 4-Bromo-1-butene, 0.5 M NaOMe/MeOH, 2. 3-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid (2:1 mole ratio), CH2Cl2; (iii) Triisopropyl borate/n-butyllithium, THF/toluene (1:4 v/v), -78°C.

To a stirred solution of N-allyl-4-bromobenzenesulfonamide 2 (11.0 g, 40 mol) in 100 ml of a dry mixture of THF and toluene (4/1, v/v) in a dry ice-acetone bath was slowly added triisopropyl borate (48 ml, 0.20 mol) under argon. A solution of 1.6 M n-butyllithium in hexane (100 ml, 0.16 mol) was then added dropwise over a period of 60 min (n-butyllithium must be handled with the appropriate precautions). The mixture was further stirred for 1 h in a dry-ice bath, and then allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred overnight. To the reaction mixture was added 100 ml of water, the mixture was stirred for 30 min, and the pH adjusted to 6.5 with 2 M HCl. The separated organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was stirred with 30 ml of chloroform, from which a white powder was precipitated that was filtered, washed with diethyl ether, and dried to afford 6.8 g of 4-(N-allylsu12/28/2007lfamoyl)phenylboronic acid 3 (70% yield). mp: 116-118°C; IR (KBr): 3510, 3410, 3270, 1600, 1405, 1320, 1270, 1155, 1120, 1090 cm-1; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.75 (d, 2H), 7.66 (d, 2H), 5.75 (m, 1H), 5.19 (q, 1H), 5.12 (q, 1H), 3.62 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ133.8, 133.6, 125.4, 115.8, 45.1.

Synthesis of 4-(3-butenylsulfonyl)phenylboronic acid 6

4-Bromobenzenethiol 4 was alkylated with 4-bromo-1-butene in a methanolic solution of 0.5 M sodium methanolate, affording (4-bromophenyl)(3-butenyl)sulfide (yield: 95%). To a rigorously stirred solution of this sulfide (6.1 g, 25 mmol in 60 ml of dichloromethane) cooled in an ice-water bath was slowly added 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (15 g, 50 mmol) (3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid must be handled with the appropriate precautions). The mixture was stirred in the ice-water bath for 4 h and quenched by the addition of 50 ml of 1 M NaOH. The organic layer was recovered and washed with water, dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 6.5 g (98% yield) of 4-bromophenyl-3-butenylsulfone 5 as a white crystalline solid. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.78 (d, 2H), 7.74 (d, 2H), 5.75 (m, 1H), 5.10 (dd, 1H), 5.06 (dd, 1H), 3.17 (m, 2H), 2.48 (m, 2H).

Analogous to the procedure for the preparation of 3 from 2, 6 was obtained from 5 as a white solid in 65% yield. Mp: 97 - 99°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.90 (d, 2H), 7.88 (d, 2H), 5.81 (m, 1H), 5.11 (dd, 1H), 5.01 (dd, 1H), 3.35 (m, 2H), 2.43 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 138.8, 134.6, 128.3, 116.4, 112.6, 75.4, 25.7.

Protection of boronic acids with N-methyl-diethanolamine

To a stirred solution of 3 (2.41 g, 10 mmol) (Scheme 2) in 10 ml of THF was added N-methyl-diethanolamine (1.42 g, 12 mmol) and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 1 h. The white crystalline precipitate formed was filtered, washed with diethyl ether, and dried under vacuum to afford 3.22 g (98%) of the desired product 7 as white powder: mp 200 ~ 202°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.78 (d, 2H), 7.76 (d, 2H), 5.64 (m, 1H), 5.16 (dd, 1H), 5.03 (dd, 1H), 4.18 (m, 4H), 3.48 (m, 2H), 3.42 (m, 2H), 3.00 (m, 2H), 2.19 (s, 3H).

Scheme 2.

Immobilization of substituted phenylboronic acids on porous silica gels. Reagents and conditions: (i) N-methyl-diethanolamine, THF; (ii) Dimethylchlorosilane, H2PtCl6, toluene, 140°C; (iii) Nucleosil 100-5 silica gel , pyridine/toluene, 120°C.

Compound 6 was protected with N-methyl-diethanolamine analogous to procedure described for 3, to give 9 as a white solid in 90% yield: mp 152 ~ 154°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.86 (d, 2H), 7.83 (d, 2H), 5.72 (m, 1H), 5.08 (dd, 1H), 5.00 (dd, 1H), 4.23 (m, 4H), 3.25 (m, 2H), 3.18 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H).

Hydrosilylation

To a stirred solution of 7 (2.63 g, 8 mmol) in 20 ml of toluene was added at room temperature 0.5 ml of hexachloroplatinic acid (0.1 mmol/L) solution in 2-propanol and 10 ml of dimethylchlorosilane. The mixture was heated to 140 °C and refluxed for 1 h. The solvent and excess silane were removed under reduced pressure and the residue was evaporated twice with chloroform to afford the desired silane 8 as a slightly brownish gum. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.76 (d, 2H), 7.73 (d, 2H), 3.95 (m, 4H), 3.45 (m, 2H), 3.30 (m, 2H), 3.00 (m, 2H), 2.67 (s, 3H), 2.2 (m, 2H), 1.3 (q, 2H), 0.1 (s, 6H). This product was used for the next synthetic step without further purification. The silane 10 was obtained from 9 by the same procedure: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.90 (d, 2H), 7.86 (d, 2H), 3.97 (m, 4H), 3.43 (m, 2H), 3.35 (m, 2H), 3.13 (m, 2H), 2.58 (s, 3H), 2.2 (m, 2H), 1.26 (m, 2H), 0.1 (s, 6H).

Modification of silica gel with 8 and 10

A suspension of 5.0 g of dry silica in 50 ml of dry toluene was concentrated to 25 ml under argon, and then cooled to room temperature. Silane 8 was dissolved in 8 ml of pyridine and added to the azeotropically dried silica slurry. The mixture was sonicated for 1 h, and then heated to 120 °C and refluxed for 24 h with exclusion of moisture. The silica gel was filtered, washed with chloroform, methanol, deionized water and acetone, and dried at 120 °C to give the boronate affinity solid phase BASP-1. Modification of silica gel with 10 gave BASP-2. The boron content of the solid phases was measured according to a published procedure [16]. The modified silica solid phases were slurry packed into 4.6 × 50 mm stainless steel columns by a conventional procedure, and eluted with 20 mM citric acid (pH 2.5) at 0.5 ml/min to remove the protecting group on the boronic acid ligand.

Nanoelectrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

Hydroxylated angiotensin I was separated by boronate affinity chromatography and analyzed by nanoelectrospray-MS/MS (NSI-MS/MS) on a Thermoelectron Classic ion trap mass spectrometer, equipped with a nanoelectrospray source (Thermoelectron). The mass spectrometer was operated using a static nanospray of analyte solution, infused by a picotip emitter (New Objective). The following instrument conditions were used for the mass spectrometer: number of microscans = 3, length of microscans = 200 ms, capillary temperature = 160°C, spray voltage = 41 V, tube lens offset = -10 V. The data acquisition was performed in a data-dependent manner such that an MS scan was followed by MS/MS scans of the three or four most intense peaks with the normalized collision energy for MS/MS set at 35% and the isolation width of 2.0 m/z. A minimal signal threshold of 2 ×106 was set for acquiring the MS/MS data.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of boronate affinity ligands

The molecular structures and the synthesis of sulfonyl- and sulfonamide- phenylboronic acids 3 and 6 are shown in Scheme 1. Intermediate 2 was prepared in a high yield according to the procedure described in the experimental section, and 5 by alkylation of 4 with 4-bromobutene followed by oxidation with a two-fold excess of 3-chloroperbenzoic acid. The conversions of 2 and 5 to the corresponding boronic acids were accomplished via the known bromo-lithium exchange reaction [17, 18]. We initially followed a sequential procedure, which involved metallation of bromo-intermediates with n-butyllithium prior to treatment with triisopropyl borate. In this way, only a very small amount of the desired product was isolated from the reaction mixture. We then modified the procedure to a one-pot treatment of a mixture of bromo-intermediate and triisopropyl borate in dry THF/toluene (1:4, v/v) with an n-butyllithium solution, which afforded 3 and 6 in good yields (> 65%). This result is in accord with the published procedures for the efficient preparation of some arylboronic acids containing strong electron-withdrawing substitutes, such as 4-cyano- and 3-nitro-phenylboronic acids [18]. As an alternative a commercially available 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid was also chosen as a starting material. However, in the present work, attempts to convert the 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid to sulfonamide-phenylboronic acid 3 via a lithium sulfonyl phenylboronic acid intermediate [19] and to sulfonyl-phenylboronic acid 6 by oxidation of its sulfide intermediates with peroxide were unsuccessful, due to the deboronation and the conversion of phenylboronic acid to phenol.

Boronate pKa of 3 and 6

The pKa values of 4-(N-allylsulfamoyl)-phenylboronic acid 3 and 4-(3-butenesulfonyl)-phenylboronic acid 6 were measured by changes in the UV absorption following the titration of 1.0 mM of the respective boronic acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer with 0.1 M NaOH [20]. A comparison of the two synthetic substituted phenylboronic acids with phenylboronic acid is displayed in Figure 1. The pKa for 3 (7.4 ± 0.1) and 6 (7.1 ± 0.1) is shifted by 1.4 and 1.7 pH units relative to that of phenylboronic acid (8.8 ± 0.1), respectively. This result is in consistent with the Hamment correlation between the pKa of substituted phenylboronic acid and its substituents [20]. The introduction of electron withdrawing groups such as sulfonyl and sulfonamide into the ring of phenylboronic acid substantially lowers the boronate pKa, as expected. It is well known that the affinity of cis-diol to boronate is pH-dependent. However, primarily the intrinsic ionization characteristics of the boronic acid determine the binding constant. Accordingly, the sulfonyl- and sulfonamide-substituted phenylboronic acids, with their relatively low pKa, can be expected to bind cis-diols at near neutral pH. In addition, the polar nature of the substituents, especially of sulfonamide, appears to improve the interaction between the boronate ligands on the silica surface and analytes in aqueous solution.

Fig. 1.

Determination of pKa values of (1) sulfonamide-phenylboronic acid 3 (○), (2) sulfonyl phenylboronic acid 6 (∇) and (3) phenylboronic acid (□) by changes in absorbance at 272 nm as a function pH. 1.0 mM solution of boronic acid in 0.10 M sodium phosphate buffer was titrated with 2.0 M NaOH.

Immobilization of synthetic ligands on porous silica

The immobilization of synthetic boronic acids 3 and 6 on porous silica is shown in Scheme 2. The efficient surface modification of porous silica gels with highly reactive monochlorosilane derivatives as silylating reagents is well established [21]. In the designed boronate ligands 3 and 6, the terminal C=C bond provides the site for hydrosilylation with a dimethylchlorosilane in the presence of a catalytic amount of chloroplatinic acid. Prior to hydrosilylation, the synthetic boronic acids were protected with N-methyl-diethanolamine and then subjected to hydrosilylation. The monochlorosilane derivative 8 was obtained as expected. The modification of porous silica gel with 8 was carried out in a mixture of toluene and pyridine by refluxing at 120 °C for 24 h. This procedure for modification was reproduced in at least three independent experiments, where the modified silica gel was found to contain 0.54 ± 0.05 mmol/g of the boronic acid. The protected sulfonyl-phenylboronic acid 10 was also loaded onto porous silica gel by the same procedure, and the loading determined as 0.42 ± 0.05 mmol/ g of the boronic acid, slightly lower than the loading with 8.

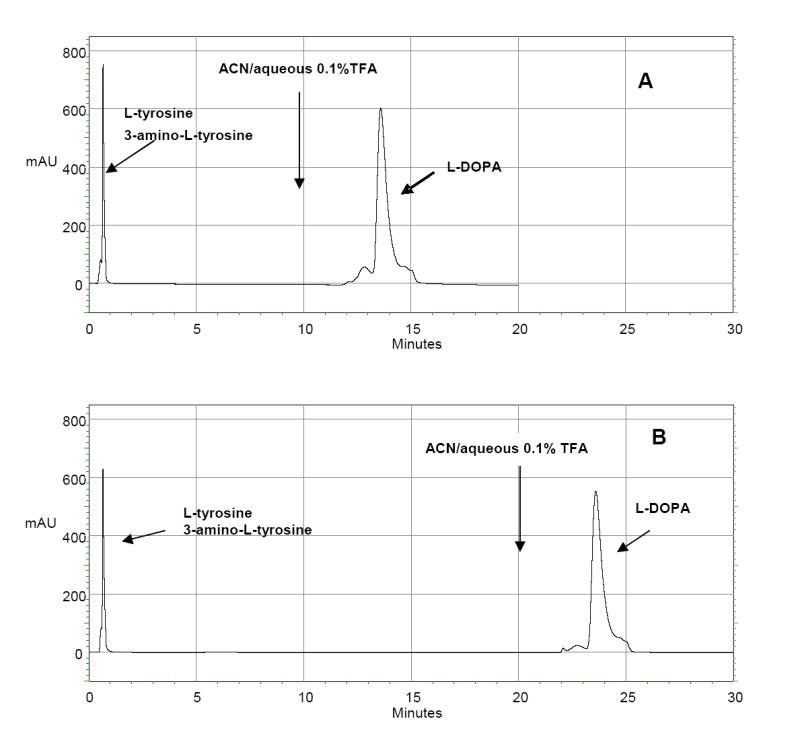

HPLC evaluation of boronate affinity

The two materials were slurry packed into 4.6 (i.d.) × 50 mm stainless columns under a pressure of 8000 p.s.i. with an air-driven fluid pump (Haskel). A synthetic mixture containing L-tyrosine, L-DOPA, 3-amino-L-tyrosine, (-)-epinephrine and (-)-norepinephrine was separated under isocratic conditions on the two synthetic boronate affinity columns at pH 5 and 5.5, respectively. The chromatograms are displayed in Figures 2A and 2B. For comparison, the separation on a commercially available column (Alltech, Prosphere Boronate 1000A, 10μ, 7.5 i.d. × 75 mm) containing immobilized unsubstituted phenylboronic acid is displayed in Fig. 2C. The corresponding retention factors of the analytes as a function of the mobile phase pH on the two synthetic columns are shown in Figure 3. Between pH 5.0 and 7.0, L-tyrosine and 3-amino-L-tyrosine did not show any retention while the diol components were well separated on both synthetic columns. Among the aryl cis-diols the elution order was L-DOPA < (-)-norepinephrine < (-)-epinephrine. Based on the substitution at the 3-position of L-tyrosine, it can be concluded that the boronate affinity of the aryl cis-diol function is responsible for the observed retention behaviors, and that hydrophobic interaction and hydrogen bonding have little effect. It is generally believed that boronic acids with lower pKa values show greater affinity binding for diols. Compared with the commercial column, the two synthetic columns displayed enhanced retention for diols. For the two synthetic columns containing substituted phenylboronic acid with comparative pKa, BASP-1 showed higher retention factors. The result is probably related to the loading amount of boronic acid on silica. It should be noted that many other factors, such as the solubility of boronic acid and the nature of buffer, etc, could also affect the boronate-diol binding [20, 22].

Fig. 2.

Isocratic separation of synthetic mixture containing catechols and L-DOPA on (A) BASP-1, (B) BASP-2 and (C) commercial column. Elution phase: 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer with pH 5.0 (-------) and 5.5 (–––––), Flow rate: 1 mL/min; Detection: UV at 280 nm; 1, 1’ = L-tyrosine; 2, 2’ = 3-amino-L-tyrosine; 3, 3’ = L-DOPA; 4, 4’ = (-)-norepinephrine; 5, 5’ = (-)-epinephrine. Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; Detection: UV at 280 nm.

Fig. 3.

Retention factors for L-tyrosine (*), 3-amino-L-tyrosine (○), L-DOPA (Δ), (-)-norepinephrine (◊) and (-)-epinephrine (□) on synthetic columns (A) BASP-1 and (B) BASP-2. Elution phase: 50 mM NaH2PO4 buffer (pH was adjusted with 6.0 M NaOH); Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; Detection: UV at 280 nm.

The separation of catechols on boronate affinity columns has been reported, where solid phases immobilized with phenylboronic acid (pKa ~ 8.8) were found to have poor retention for catechols at pH < 7 [10]. In contrast, our new immobilized boronic acids show very high retention capacities for aryl diols even in the pH range between 5 and 7 (Fig. 4). Singhal et al [10] compared the separation of L-DOPA, (-)-norepinephrine and (-)-epinephrine on two columns with different boronate affinity capacity, and found that the positive charge on the primary and secondary amines, as well as the negative charge associated with the carboxylate function could lead to the loss of the retention on solid boronate phases. In this work, separations were performed at pH in the range from 5 to 7 under which the primary amine (pKa 8.6) and secondary amine (pKa 9.9) are positively charged. However, very little effect of charge on retention was observed.

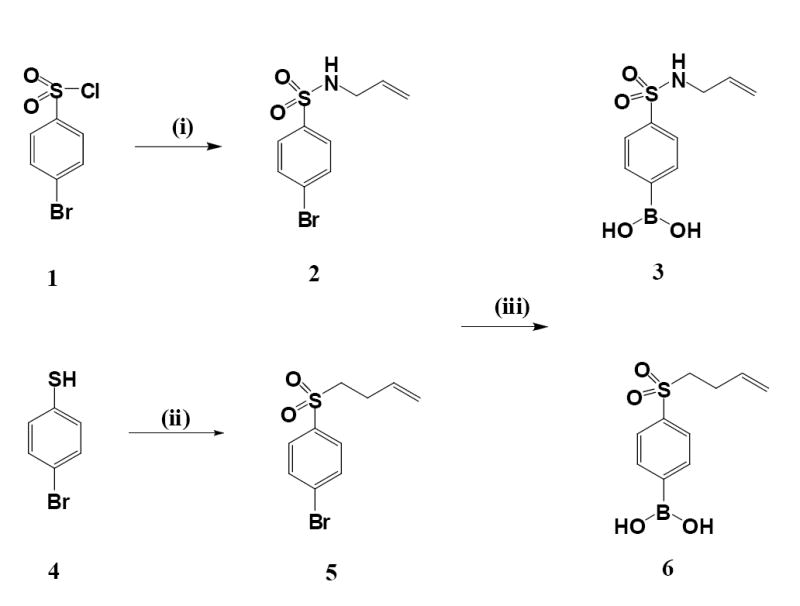

Fig. 4.

Isocratic separation of tri-, di- and mono-phosphates of adenosine on synthetic columns (A) BASP-1 and (B) BASP-2. Elution phase: 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0); Flow rate: 0.5 mL/min; Detection: UV at 260 nm.

A specially designed boronate affinity solid phase, immobilized 3-amino-phenyl boronic acid, has been developed by Glad et al. to achieve complete separation of adenosine phosphates at pH 7.5 [23]. On our synthetic columns, the three phosphates of adenosine are well resolved at a significantly lower pH. Figure 4 and 5 show the chromatography of the three adenosine phosphates on our boronate affinity column at pH6.0 and the pH-dependent change in retention factors, respectively. Because alkyl cis-diols show much lower affinity towards boronic acids than aryl diols [20], the lower retention for alkyl cis-diols is expected compared to L-DOPA, (-)-norepinephrine and (-)-epinephrine. Based on the differences in adenosine phosphate retention, the number of negative charges on the analytes shows a significant influence on the association of analyte to the boronate ligand. At pH > 6.5, the influence of negative charge even suppresses the pH-dependent increase of boronate affinity, displaying a weaker retention with increasing pH. For comparison, Figure 6 shows the pH-dependent retention behavior of the neutral analyte uridine on our synthetic column, where the retention increases proportionally with pH.

Fig. 5.

Retention factors for tri- (○), di- (□) and mono- (Δ) phosphate of adenosine on (A) BASP-1 and (B) BASP-2. Elution phase: 50 mM NaH2PO4 buffer (pH was adjusted with 6.0 M NaOH); Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; Detector: UV 260 nm.

Fig. 6.

Retention of uridine on BASP-1 at pH 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 and 7.0. Elution phase: 50 mM phosphate (pH was adjusted with 6.0 M NaOH); Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; Detection: UV at 260 nm.

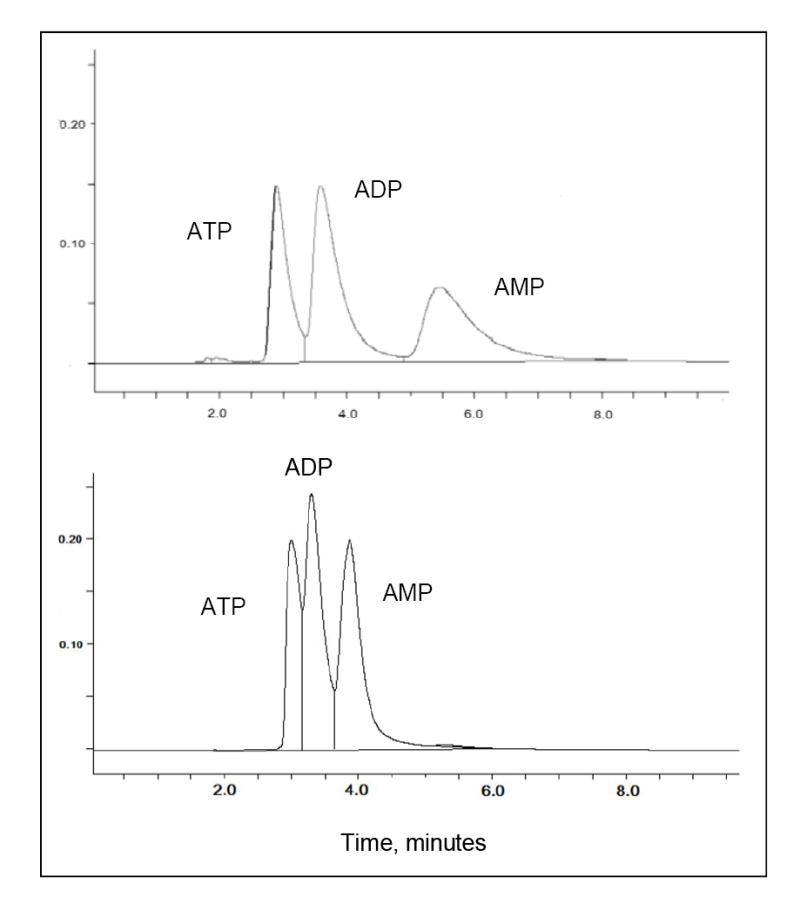

Separation and Enrichment of L-DOPA Containing Compounds

To demonstrate the practicality of these synthetic boronate affinity columns for the separation and enrichment of diol compounds, the boronate affinity chromatography was performed using a 50:50 v/v ACN/50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) as a mobile phase for binding of diol compounds and subsequently a 50:50 v/v ACN/aqueous 0.1% TFA for elution. A synthetic mixture containing L-tyrosine, 3-amino-tyrosine and L-DOPA was loaded on the BASP-1 and eluted with binding buffer, during which L-DOPA was retained on the column and the L-tyrosine and 3-amino-tyrosine were eluted. L-DOPA was then eluted as the mobile phase was changed to ACN/aqueous 0.1% TFA. The result is shown in Figure 7. The elution time of L-DOPA was changed with the switching of mobile phases for binding and elution.

Fig. 7.

Boronate affinity chromatography of a synthetic mixture of L-tyrosine, 3-amino-L-tyrosine and L-DOPA on BASP-1. Mobile phase: 50:50 v/v ACN/50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH7.0). At (A) 10 min and (B) 20 min, the mobile phase was changed to 50:50 v/v ACN/aqueous 0.1% TFA. Flow rate: 1 mL/min; Detection: UV at 280 nm;

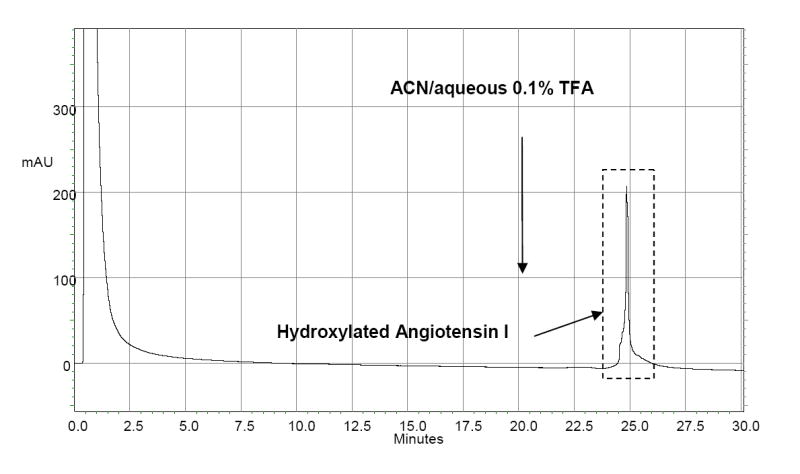

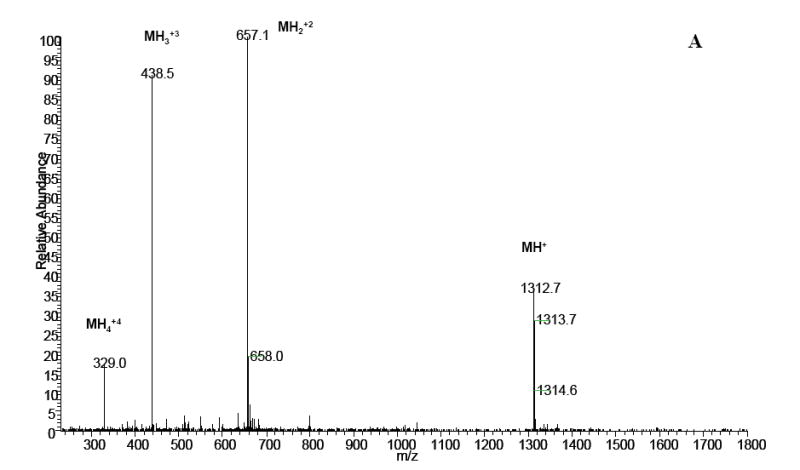

Tyrosinase-catalyzed hydroxylation of angiotensin I led to the conversion of the tyrosine residue in the peptide to DOPA. The DOPA-containing peptide was also found to bind tightly to BASP-1 under the same conditions as used for the amino acid L-DOPA. Figure 8 shows the boronate affinity chromatography of a reaction mixture of native and hydroxylated angiotensin I. Native angiotensin I showed no affinity for the column and was eluted with non-retained constituents in the reaction mixture by the binding buffer. The hydroxylated peptide remained bound to the column, and was eluted upon changing the mobile phase to ACN/aqueous 0.1% TFA. Figure 9 shows the mass spectrum of the fraction from the late eluted peak in Fig. 8, confirming that hydroxylation occurred specifically at the tyrosine residue in the peptide and that the DOPA-containing peptide was separated as a single peptide by boronate affinity chromatography. The results presented in Fig. 8 and 9 confirm that the new synthetic affinity phases can be used for the separation and enrichment of diol compounds at a relatively low pH, which would be particularly valuable for the prevention of oxidation and cross-linking of DOPA in proteins [25].

Fig. 8.

Boronate affinity chromatography of a reaction mixture after tyrosinase-catalyzed hydroxylation of angiotensin I on BASP-1. Mobile phase: 50:50 v/v ACN/50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH7.0), at 20 min the mobile phase was changed to 50:50 v/v ACN/aqueous 0.1% TFA. Flow rate: 1 mL/min; Detection: UV at 280 nm;

Fig. 9.

MS and MS/MS analysis of the late eluting peak from Fig.8, confirming DOPA-containing angiotensin I (DRVY*IHPFHL), (A) MS spectrum; (B) MS/MS spectrum of in (A).

Conclusion

A new type of boronate affinity phases containing immobilized sulfonamide- and sulfonyl-phenylboronic acids on porous silica has been synthesized. Based on the HPLC data with aryl and alkyl cis-diols, the new phases show an enhanced boronate affinity and operate well at neutral and slightly acidic pH. Such low pH environment is particularly suitable for oxidation-sensitive analytes of biological importance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the NIH (AG25350).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bergold A, Scouten WH. Borate chromatography. Chem Anal. 1983;66:149–187. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X-C, Scouten WH. Miscellaneous methods in affinity chromatography. Part I: boronic acids as selective ligands for affinity chromatography. Biochromatogr. 2002:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson NL, Karlsson NG, Packer NH. Enrichment and analysis of glycoproteins in the proteome. In: Smejkal GB, Lazareu A, editors. Separation Methods in Proteomics. CRC Press; LLC, Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hage DS. Clinical applications of high-performance affinity chromatography. Adv Chromatogr. 2003;42:377–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal RP, DeSilva S, Shyamali M. Boronate affinity chromatography. Adv Chromatogr. 1992;31:293–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miksik I, Deyl Z. Post-translational non-enzymic modification of proteins. II. Separation of selected protein species after glycation and other carbonyl-mediated modifications. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;699:311–345. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleicher E, Wieland OH. Protein glycation: measurement and clinical relevance. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1989;27:577–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bry L, Chen PC, Sacks DB. Effects of hemoglobin variants and chemically modified derivatives on assays for glycohemoglobin. Clin Chem. 2001;47:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Gerwick WH, Fenical W, Fritsch N, Clardy J. Stypotriol and stypoldione; ichthyotoxins of mixed biogenesis from the marine alga Stypopodium zonale. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;2:145–8. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen L, Qiu S, Chen Y, Zhang F, van Breemen RB, Nikolic D, Bolton JL. Alkylation of 2’-deoxynucleosides and DNA by the Premarin metabolite 4-hydroxyequilenin semiquinone radical. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:94–101. doi: 10.1021/tx970181r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhal RP, Ramamurthy B, Govindraj N, Sarwar Y. New ligands for boronate affinity chromatography: synthesis and properties. J Chromatogr. 1991;543:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardiner SJ, Smith BD, Duggan PJ, Karpa MJ, Griffin GJ. Selective fructose transport through supported liquid membranes containing diboronic acid or conjugated monoboronic acid-quaternary ammonium carriers. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:2857–2864. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matteson DS. Functional group compatibilities in boronic ester chemistry. J Organomet Chem. 1999;581:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitner A, Lindner W. Current chemical tagging strategies for proteome analysis by mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;813:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeuwenburgh C, Hansen P, Shaish A, Holloszy JO, Heinecke JW. Markers of protein oxidation by hydroxyl radical and reactive nitrogen species in tissues of aging rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R453–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeg-Jensen T, Ridderberg S, Havelund S, Schaeffer L, Balschmidt P, Jonassen IB, Vedso P, Olesen PH, Markussen J. Insulins with built-in glucose sensors for glucose responsive insulin release. J Peptide Sci. 2005;11:339–346. doi: 10.1002/psc.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron H. Simplified determination of boron in plants with 1,1’-dianthrimide. Z Anal Chem. 1954;143:339–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brikh A, Morin C. Boronated thiophenols: a preparation of 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid and derivatives. J Organomet Chem. 1999;581:82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Nelson DP, Jensen MS, Hoerrner RS, Cai D-W, Larsen RD, Reider PJ. An Improved Protocol for the Preparation of 3-Pyridyl-and Some Arylboronic Acids. J Org Chem. 2002;67:5394–5397. doi: 10.1021/jo025792p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vedso P, Olesen PH, Hoeg-Jensen T. Synthesis of sulfonyl chlorides of phenylboronic acids. Synlett. 2004;5:892–894. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan J, Springsteen G, Deeter S, Wang B. The relationship among pKa, pH, and binding constants in the interactions between boronic acids and diols-it is not as simple as it appears. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:11205–11209. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Andersson JT, Kaiser G. How to Freely Change the Polarity of the Stationary Phase in a Liquid Chromatographic Column. Anal Chem. 1997;69:636–642. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dobashi Y, Hara S. A chiral stationary phase derived from (R,R)-tartramide with broadened scope of application to the liquid chromatographic resolution of enantiomers. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2490–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Springsteen G, Deeter S, Wang B. A detailed examination of boronic acid-diol complexation. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:5291–5300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glad M, Ohlson S, Hansson L, Maansson M-O, Mosbach K. High-performance liquid affinity chromatography of nucleosides, nucleotides and carbohydrates with boronic acid-substituted microparticulate silica. J Chromatogr. 1980;200:254–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marumo K, Waite JH. Optimization of hydroxylation of tyrosine and tyrosine-containing peptides by mushroom tyrosinase, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 1986;872:98–103. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burzio LA, Waites JH. Reactivity of peptidyl-tyrosine to hydroxylation and cross-linking. Protein Sci. 2001;10:735–740. doi: 10.1110/ps.44201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]