Abstract

Influenza virus entry occurs in endosomes, where acidification triggers irreversible conformational changes of the hemagglutinin glycoprotein (HA) that are required for membrane fusion. The acid-induced HA structural rearrangements have been well documented, and several models have been proposed to relate these to the process of membrane fusion. However, details regarding the role of specific residues in the initiation of structural rearrangements and membrane fusion are lacking. Here we report the results of studies on the HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus (H3 subtype), in which mutants with changes at several ionizable residues in the vicinity of the “fusion peptide” were analyzed for their effects on the pH at which conformational changes and membrane fusion occur. A variety of phenotypes were obtained, including examples of substitutions that lead to an increase in HA stability at reduced pH. Of particular note was the observation that a histidine to tyrosine substitution at HA1 position 17 resulted in a decrease in pH at which HA structural changes and membrane fusion take place by 0.3 relative to WT. The results are discussed in relation to possible mechanisms by which HA structural rearrangements are initiated at low pH and clade-specific differences near the fusion peptide.

Keywords: influenza, hemagglutinin, membrane fusion, fusion peptide, HA structure, conformational change

Introduction

Membrane fusion is a biological process required for a variety of fundamental viral and cellular functions. Developments in recent years have significantly expanded the understanding of the fusion mechanisms for both class I and class II viral fusion glycoproteins (Barnard, Elleder, and Young, 2006; Colman and Lawrence, 2003; Doms, 2004; Dutch, Jardetzky, and Lamb, 2000; Earp et al., 2005; Earp LJ, 2005; Eckert and Kim, 2001; Harrison, 2005; Huang et al., 2003; Kielian, 2006; Lamb, Paterson, and Jardetzky, 2006; Sieczkarski and Whittaker, 2005; Skehel and Wiley, 2000; Smith and Helenius, 2004). Among the class I viral fusion proteins, related mechanisms for fusion have evolved in which a metastable form of the molecule is converted into a highly thermostable conformation during the fusion process. These thermostable structures are rodlike in appearance and all contain a central trimeric α-helical coiled coil and antiparallel polypeptide chains that pack against it. As a consequence of the refolding events, the hydrophobic transmembrane and fusion peptide domains of the glycoproteins, which are postulated to associate with the viral and cellular membranes respectively as part of the fusion process, are brought into close proximity with one another. For the class I viral fusion proteins there are a number of mechanisms by which such conformational changes can be triggered to initiate the fusion process. These include receptor binding with the involvement of coreceptors, receptor binding and interaction with separate viral fusion proteins, and activation of a viral fusion protein by acidification following endocytosis.

Influenza A is a well characterized example of a virus that enters the host cell via the endocytic pathway, and structural studies spanning the past three decades have made the HA glycoprotein a valuable paradigm for studies on viral membrane fusion in general (Bullough et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1998; Wilson, Skehel, and Wiley, 1981). Similar to other class I viral fusion proteins, the polypeptide chains of the HA precursor (HA0) associate as homotrimers in the endoplasmic reticulum during biosynthesis. Each monomer of HA0 is subsequently cleaved at a surface loop into the disulfide-linked polypeptides HA1 and HA2. This generates hydrophobic HA2 N-terminal fusion peptide domains and transforms the molecule into its metastable conformation to activate the membrane fusion potential of HA. As a consequence, HA0 cleavage is required for virus infectivity (Appleyard and Maber, 1974; Klenk et al., 1975; Lazarowitz and Choppin, 1975). After attachment to host cells and internalization, HA undergoes irreversible conformational changes due to the acidification of the endosomal environment, and membrane fusion is induced.

The current study focuses on the analysis of residues near the fusion peptide of cleaved HA that may be involved in the initiation of the acid-induced HA conformational changes required for fusion. While it is known that amino acid substitutions at various locations in the HA trimer are capable of destabilizing the native structure leading to an increase in the pH of fusion, the possibility that protonation of specific residues provide the initial trigger for conformational changes remains unresolved. The region surrounding the fusion peptide in the native HA structure is of interest regarding potential triggers for fusion for several reasons. Among the many mutants with elevated fusion pH identified in studies based on amantadine resistance, site-directed mutagenesis, and reverse genetics, those involving amino acid substitutions in and around the fusion peptide are particularly well represented (Cross et al., 2001; Daniels et al., 1985; Lin et al., 1997; Steinhauer, 1993). In fact, nearly all amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal region of the fusion peptide that have been analyzed to date lead to increased fusion pH, regardless of the HA position or the amino acid introduced (Cross et al., 2001; Gething et al., 1986; Steinhauer et al., 1995). Studies on double mutant HAs also indicate that amino acid substitutions in and around the fusion peptide are dominant in dictating the pH of fusion when expressed in combination with substitutions elsewhere in the molecule (Steinhauer et al., 1996). Other studies using anti-peptide antibodies to detect changes in HA structure also suggest that conformational changes involving the fusion peptide and proximal residues precede the de-trimerization of the HA1 head domains (White and Wilson, 1987).

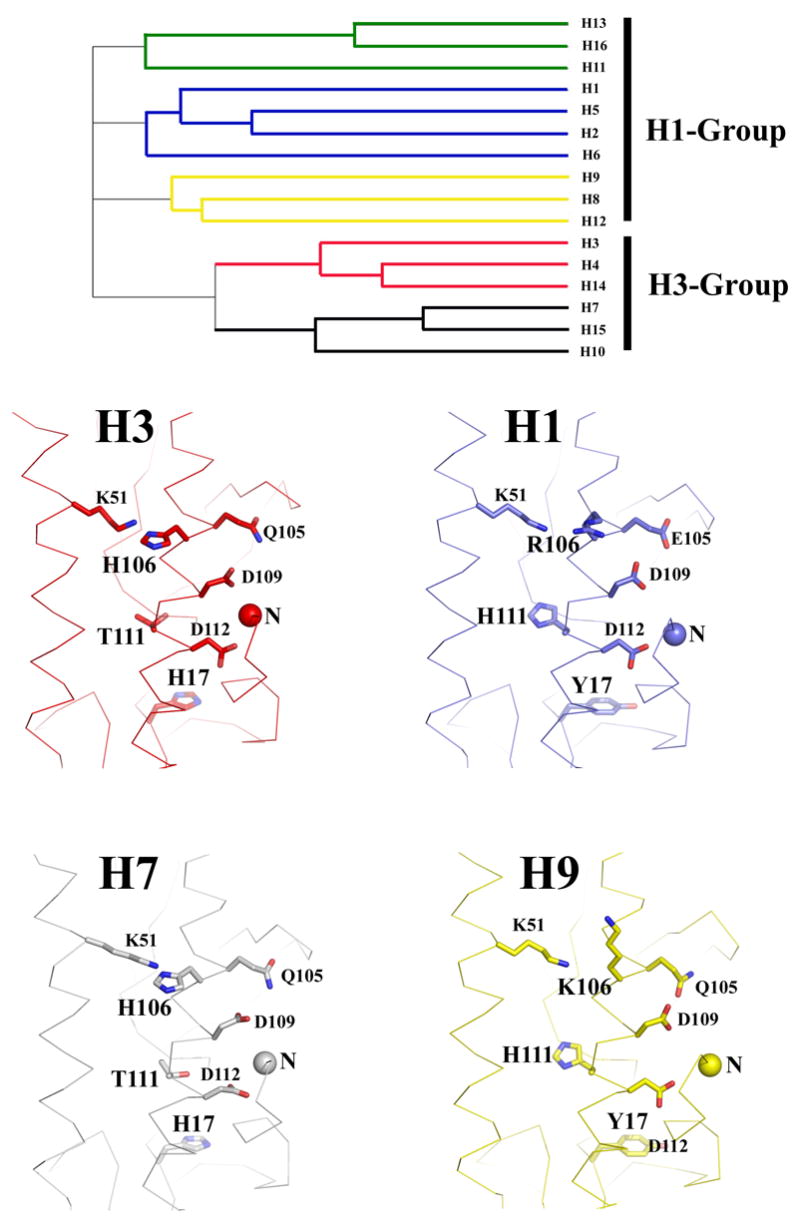

When HA0 is cleaved into HA1 and HA2 to prime membrane fusion potential, only six residues at the C-terminus of HA1 and 12 residues at the N-terminus of HA2 are relocated (Chen et al., 1998). As the conformational changes that accompany cleavage are restricted to this region, the accessibility to solvent is altered for of only a selected number of ionizable residues in the trimer. A comparison of the structures of different subtype HAs show that some of the ionizable residues that are buried by the fusion peptide after cleavage are completely conserved, while others vary strictly along clade-specific lines (Gamblin et al., 2004; Ha et al., 2002; Russell et al., 2004; Wilson, Skehel, and Wiley, 1981). The recently determined H13 subtype HA structure (Russell et al., unpublished) now divides the HAs into five clades, and when structural characteristics of the fusion peptide region are compared the five clades can be separated into two groups as depicted in Figure 2. The H1 group includes H1-, H9-, and H13-like viruses, and the H3 group includes the H3 and H7 clades. In all HAs HA2 residues K51, D109, and D112 are completely conserved, whereas the residues at positions HA1 17, and HA2 106, and 111 are group-specific. Among H3 group HAs, such as the Aichi HA analyzed in this study, HA1 17 and HA2 106 are always histidine, and HA2 111 is threonine. In the H1 group HAs, HA1 17 is tyrosine, HA2 111 is histidine, and HA2 106 is either a basic lysine or arginine residue (Fouchier et al., 2005; Kawaoka et al., 1990; Nobusawa et al., 1991; Rohm et al., 1996).

Figure 2.

The top panel shows a phylogenetic tree showing the HA subtype clades as defined by sequence and structural analyses (Russell et al., 2004). The clades are divided into the H1 and H3 groups based on structural considerations in the fusion peptide region. Panels at the bottom show a structural comparison of H3, H7, H1, and H9 HAs focusing on the region near the fusion peptide. The HA2 N-termini are labeled by colored balls. The locations of residues addressed in this study are indicated and the three positions that segregate in clade-specific groupings, HA1 17, HA2 106, and HA2 111, are labeled in bold font (all HA numbering in this paper is based on the H3 subtype).

We postulate that these residues are involved in modulating the stability of cleaved HA, and that the introduction of substitution mutations at these positions will have a tendency to alter the pH at which conformational changes are induced. Changes to positions that result in increased stability (reduced pH of fusion) could possibly help identify residues that are involved in the triggering of conformational changes when protonated. To examine the possible role of specific residues in the initiation of fusion upon acidification, we generated a series of single, double, and triple amino acid substitution mutants in an H3 subtype HA. The mutant HAs were analyzed for folding, cell-surface transport, acid-induced structural changes, the pH at which they take place, and membrane fusion properties. A variety of phenotypes were detected, including examples that undergo conformational changes and mediate membrane fusion at reduced pH. A possible role for particular ionizable residues in the initiation of the fusion process is discussed. Furthermore, we compare the structures of this region among HA subtypes and discuss clade-specific differences with regard to acid-induced activation of membrane fusion.

RESULTS

A series of single, double, and triple amino acid substitution mutants were constructed in the HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus at position 17 of the HA1 subunit and at positions 51, 105, 106, 109, 111 and 112 of the HA2 subunit, and recombinant vaccinia viruses were generated for their expression. The structural locations of these positions are indicated in Figure 2. These include residues that become occluded from access to bulk solvent following cleavage of HA0 and transition to the metastable neutral pH conformation. For these, the chemical environment and potential for protonation may change following cleavage activation of HA. The mutants that were analyzed involved alanine substitutions, and changes in which the ionization properties of side chains were altered using amino acids of similar dimension. In addition, we made mutants in which the residues of the H3 HA at positions 17 of HA1 and positions 105, 106, and 111 of HA2 were exchanged for residues at the equivalent structural locations in the H1 group HAs.

Cell surface expression by ELISA

The mutants that were generated and analyzed in this study are listed in Table 1, along with ELISA data for antibody reactivity to cell-surface expressed HAs. A panel of six monoclonal antibodies and a rabbit polyclonal antiserum were used to assess HA expression and protein folding following infection of HeLa cell monolayers with recombinant vaccinia viruses. The monoclonal antibodies utilized are known to bind to a range of sites on the HA structure based on the locations of changes mapped in neutralization-resistant virus mutants (Daniels et al., 1983), and electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography studies of HA-antibody complexes (Bizebard et al., 2001; Wrigley et al., 1983). The monoclonal antibodies HC3 and HC100 recognize the neutral as well as the low pH conformation of HA. The other monoclonal antibodies are specific for the neutral pH structure of HA, but lose reactivity as a result of acid-induced HA conformational changes. The α-X31 antibody is a rabbit polyclonal serum raised against the bromelain-solubilized ectodomain (BHA) of the WT HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus. Table 1 shows the data for expression of the mutants as a percentage of the WT reactivity (designated as 100%). The data show that with the exception of the double and triple mutants (H1062R, T1112H), (D1092A, D1122A) (H171A, H1062A, T1112A), and (H171Y, H1062R, T1112H), all mutants reacted with the antibodies at levels similar to WT HA (subscripts denote the HA polypeptide). Of these, the mutant (D1092A, D1122A) reacted poorly with all of the monoclonal antibodies and the polyclonal serum, indicating that it is probably not transported to the cell surface. The other three reacted well only with the antibodies that recognize both the native and low pH conformations of HA (HC3, HC100 and the polyclonal serum), but not the neutral pH-specific antibodies, indicating that they express at the cell surface in conformations that are more characteristic of low pH HA than the neutral pH structure.

Table 1.

Antibody reactivity of cell-surface HAs by ELISA (% WT)

| HA | HC3 | HC31 | HC67 | HC68 | HC100 | HC263 | α-X31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| H171A | 100 | 85 | 99 | 82 | 105 | 81 | 104 |

| H171Y | 102 | 98 | 108 | 90 | 113 | 83 | 101 |

| K512A | 109 | 99 | 98 | 84 | 106 | 96 | 106 |

| K512E | 104 | 75 | 85 | 89 | 98 | 82 | 101 |

| Q1052A | 109 | 99 | 96 | 88 | 105 | 98 | 104 |

| Q1052E | 111 | 98 | 97 | 93 | 110 | 99 | 108 |

| H1062A | 106 | 113 | 102 | 100 | 107 | 93 | 105 |

| H1062F | 106 | 98 | 84 | 92 | 98 | 95 | 108 |

| H1062R | 99 | 78 | 99 | 85 | 106 | 83 | 112 |

| D1092A | 102 | 105 | 104 | 98 | 103 | 88 | 107 |

| T1112A | 110 | 125 | 104 | 105 | 117 | 99 | 105 |

| T1112H | 100 | 70 | 89 | 86 | 107 | 77 | 106 |

| T1112V | 99 | 78 | 81 | 88 | 101 | 88 | 109 |

| D1122A | 98 | 107 | 99 | 104 | 105 | 88 | 105 |

| H1062A, T1112A | 98 | 92 | 103 | 92 | 109 | 76 | 104 |

| H1062F, T1112V | 96 | 75 | 73 | 85 | 89 | 79 | 95 |

| H1062R, T1112H | 96 | 27 | 35 | 48 | 84 | 31 | 96 |

| D1092A, D1122A | 21 | 16 | 8 | 22 | 26 | 14 | 38 |

| H171A, H1062A, T1112A | 91 | 47 | 43 | 54 | 85 | 33 | 94 |

| H171Y, H1062A, T1112A | 100 | 98 | 104 | 87 | 107 | 81 | 107 |

| H171Y, H1062R, T1112H | 102 | 31 | 12 | 27 | 91 | 23 | 96 |

Values represent averages derived from a minimum of three separate experiments

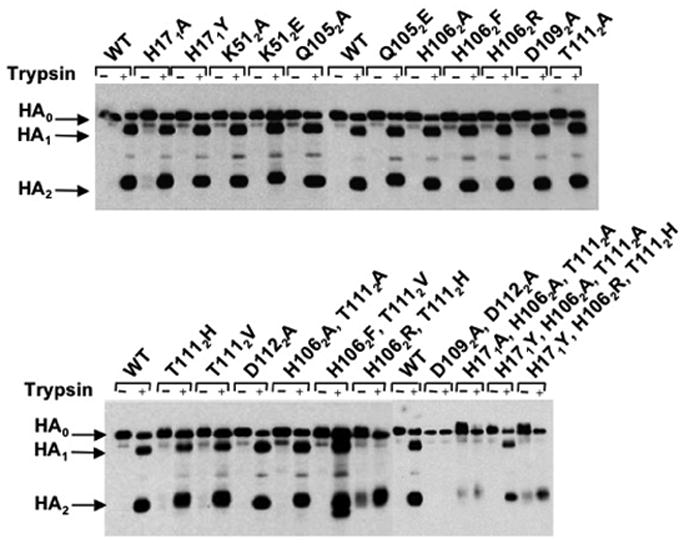

Analysis of cell surface expression by trypsin susceptibility

Influenza HA is expressed at the surface of recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in its uncleaved precursor form. Therefore, cleavage of HA0 into the HA1 and HA2 polypeptides by trypsin treatment of HA-expressing cell monolayers can be used as an assay for HA transport to the cell surface. In addition, the characteristic migration patterns of the trypsin cleavage products following polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions can provide an indicator that the HA is folded properly in the native conformation. Figure 3 shows a western blot analysis of WT and mutant HA-expressing cell lysates processed following the incubation of monolayers with or without trypsin. The results reveal that WT HA and all single residue substitution mutants can be cleaved into HA1 and HA2 polypeptides of characteristic size, confirming that they are expressed at the cell surface. Digestion of the double mutants (H1062A, T1112A) and (H1062F, T1112V) and the triple mutant (H171Y, H1062A, T1112A) also yielded HA1 and HA2 polypeptides that resembled in size those of WT HA, although the (H1062F, T1112V) HA2 band migrated as a doublet containing an additional product of lower apparent molecular weight. On the other hand, the results obtained following trypsin treatment of the double mutants (H1062R, T1112H) and (D1092A, D1122A), and the (H171A, H1062A, T1112A), and (H171Y, H1062R, T1112H) triple mutants differed significantly from those observed with WT HA. The (D1092A, D1122A) HA blot revealed only low intensity bands corresponding to HA0, with or without added trypsin. Presumably this HA does not fold correctly or express on the cell surface, as suggested by the lack of reactivity to any sera by ELISA in experiments described above. The other three mutant HAs, (H1062R, T1112H), (H171A, H1062A, T1112A), and (H171Y, H1062R, T1112H), produce bands corresponding to HA2 in molecular weight following trypsin digestion, but no HA1 bands can be detected. For these mutants, a slower migrating HA0 component is observed in the absence of added protease, suggesting aberrant glycosylation properties. The ELISA results described above demonstrate that polyclonal sera and antibodies that recognize both neutral and low pH HA can effectively bind these three mutant HAs, but they are recognized poorly with the neutral pH-specific antibodies. Taken together, the results of the two assays suggest that these mutants are likely to be transported to the cell surface in an altered conformation, perhaps resembling the low pH structure. The results and our interpretations of the ELISA and cell surface trypsin cleavage experiments are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Cell surface expression of HAs as assayed by trypsin cleavage of HA0 into HA1 and HA2. Recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing cell monolayers were incubated with or without trypsin and cell lysates were analyzed by western blot following SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

Table 2.

Overview of HA mutant expression results

| HA | Expression characteristicsa |

|---|---|

| WT, all single mutants, (H1062A, T1112A), (H1062F, T1112V), and (H171Y, H1062A, T1112A) | ELISA - react with non-specific antibodies, react with conformation-specific antibodies |

| Trypsin cleavage -HA0 cleaved

HA1 generated HA2 generated | |

| Interpretation - HA expressed on cell surface in native neutral pH conformation | |

|

| |

| (H1062R, T1112H), (H171A, H1062A, T1112A), and (H171Y, H1062R, T1112H) | ELISA - react with non-specific antibodies reduced reactivity with conformation-specific antibodies |

| Trypsin cleavage -HA0 doublet (CHO?) cleaved

HA1 degraded HA2 generated, also present in small quantities w/o trypsin treatment | |

| Interpretation - HA expressed on cell surface in non-native conformation, possibly resembling the lowpH structure | |

|

| |

| (D1092A, D1122A) | ELISA - Poor reactivity to all antibodies |

| Trypsin cleavage - HA0 bands only, with or without trypsin | |

| Interpretation - HA does not fold correctly or is very unstable, degraded in the ER or during transport to the cell surface | |

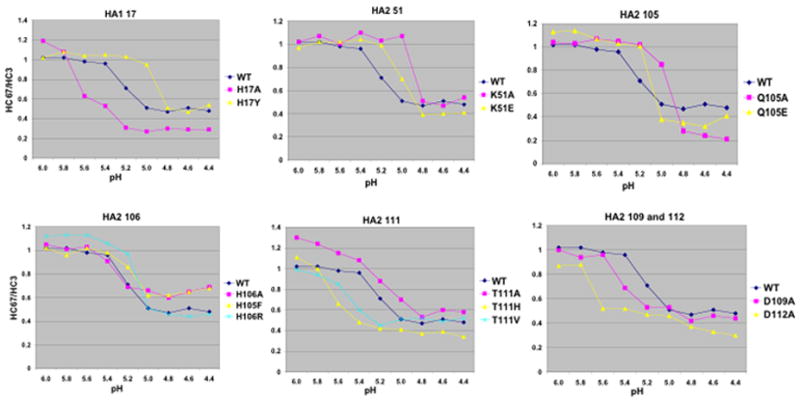

Analysis of the pH of conformational change by ELISA

Antibody HC3 recognizes residues located in a surface loop that does not change structure when HA is acidified (Bizebard et al., 1995; Wiley and Skehel, 1987), and therefore reacts well with both the neutral and low pH structures of HA. On the other hand, HC67 recognizes an antigenic site at a membrane distal trimeric interface that is lost when the HA head regions de-trimerize at low pH. Consequently, pH adjustment of HA-expressing cells followed by ELISA to compare the reactivity of these two antibodies can be used to estimate the pH at which conformational changes take place. Figure 4 shows the ELISA results for the single amino acid HA substitution mutants presented in graph form plotting the ratio of HC67 to HC3 reactivity as a function of pH. The midpoint of the curves shown in Figure 4 is designated as the pH of conformational change and the differences between these determinations for mutant HAs compared to WT (the ΔpH of conformational change) are shown as a component of Table 3. Several of the mutant HAs demonstrated a significantly elevated pH of conformational change, while others appeared more acid-stable. Most notable amongst the latter were the HA1 H17Y and the HA2 K51A mutants, which were observed to undergo conformational changes at a pH 0.3 lower than WT (pH 4.9 vs. pH 5.2).

Figure 4.

Graphs of ELISA data showing the pH of conformational change for various mutant and WT HAs. Graphs plot the ratios of HC67/HC3 reactivity as a function of pH. HC67 binds well with neutral pH HA, but poorly to the low pH structure. HC3 binds equally well with both HA conformations.

Table 3.

Summary of mutant data on ΔpH of conformational change relative to WT

| ΔpHa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Trypsin | Polykaryon | Average | |

| H171A | + 0.4 | + 0.4 | + 0.4 | + 0.4 |

| H171Y | − 0.3 | − 0.4 | − 0.3 | − 0.3 |

| K512A | − 0.3 | − 0.1 | − 0.1 | − 0.2 |

| K512E | − 0.2 | − 0.1 | − 0.1 | − 0.1 |

| Q1052A | − 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − 0.1 |

| Q1052E | − 0.1 | + 0.1 | + 0.1 | 0.0 |

| H1062A | + 0.1 | + 0.2 | + 0.1 | + 0.1 |

| H1062F | − 0.1 | − 0.1 | − 0.2 | − 0.1 |

| H1062R | − 0.1 | + 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| D1092A | + 0.2 | + 0.4 | + 0.3 | + 0.3 |

| T1112A | + 0.1 | 0.0 | + 0.1 | + 0.1 |

| T1112H | + 0.6 | + 0.6 | + 0.6 | + 0.6 |

| T1112V | + 0.3 | + 0.3 | + 0.3 | + 0.3 |

| D1122A | + 0.5 | + 0.5 | + 0.5 | + 0.5 |

| H1062A, T1112A | + 0.4 | + 0.4 | −b | + 0.4 |

| H1062F, T1112V | + 0.4 | + 0.4 | +/−c | + 0.0 |

| H171Y, H1062A, T1112A | + 0.1 | 0.0 | + 0.1 | + 0.1 |

The values given for each assay represent the average from a minimum of three experiments. In all cases the range among replicates was less than 0.1 pH units.

No polykaryon formation detected at any pH.

Only low levels of fusion detected, and only at pH 0.1 or more lower than WT

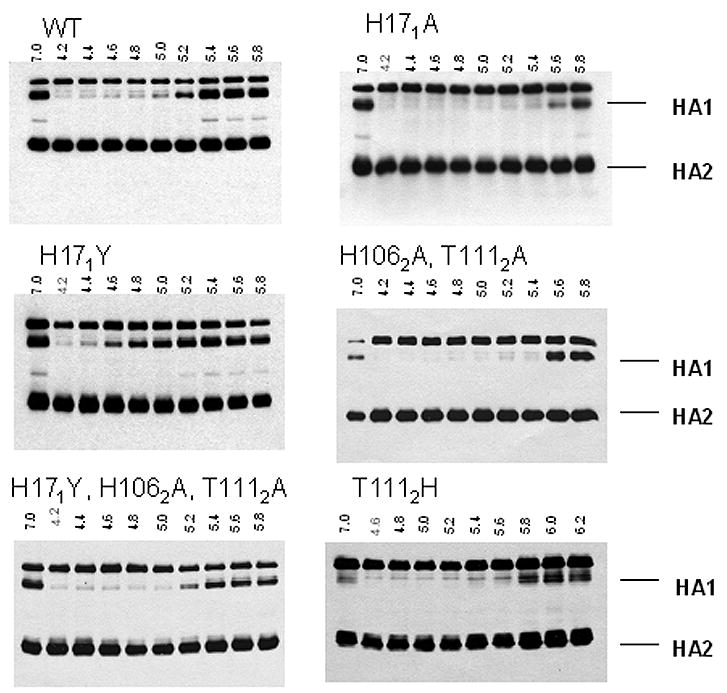

Analysis of the pH of conformational change by trypsin susceptibility

Once HA0 has been cleaved into HA1 and HA2, the neutral pH structure is highly resistant to further proteolytic digestion by trypsin and several other proteases. However, the molecular rearrangements induced by acidification render the HA1 subunit susceptible to digestion by trypsin (Skehel et al., 1982). Therefore, we used trypsin susceptibility as an alternative assay to determine the pH at which the structural changes take place for mutant HAs. CV1 cells were infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses and the HA-expressing cell monolayers were trypsin treated to cleave HA0, the pH was adjusted in decreasing increments of 0.2, and HA digestion was analyzed following a second trypsin digestion. Cell lysates were then processed using reducing conditions and analyzed by western blot. The digestion profiles for a selection of the HAs as a function of pH are shown in Figure 5. Band intensities were quantified to estimate the pH of HA1 digestion as an indicator of the pH of conformational change, and the ΔpH values relative to WT are shown in Table 3. Overall, the results are in general agreement with those obtained by ELISA, with only a few examples of minor variation in the values obtained for ΔpH of conformational change.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis for the determination of the pH of conformational change by trypsin susceptibility. HA expressing cells were treated with trypsin to cleave HA0, washed, pH was adjusted as indicated, and monolayers were again treated with trypsin. Lysates were then analyzed by western blot following SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. The disappearance of HA1 bands indicates the pH of conformational change.

Analysis of the pH of membrane fusion by polykaryon formation

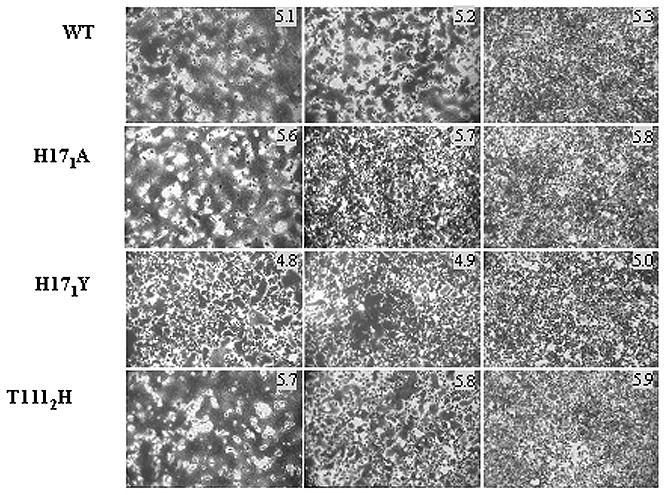

The fusion properties of recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells expressing WT or mutant HAs were analyzed using an assay for polykaryon formation. BHK-21 cells were infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses, trypsin treated, the pH was reduced incrementally from one well to the next, and the pH of monolayers was neutralized. Cells were then incubated in complete medium and monitored for evidence of fusion by light microscopy. The results of polykaryon formation as a function of pH are shown for selected mutants in Figure 6, and the ΔpH results for all mutants are summarized in Table 3. The results for pH of polykaryon formation are consistent with those obtained by ELISA and trypsin susceptibility for pH of conformational change. The only clear discrepancy involved the double mutants at HA2 positions 106 and 111. The (H1062A, T1112A) and (H1062F, T1112V) mutants were both observed to undergo structural changes at pH 0.4 above WT, but in both cases the capacity to mediate polykaryon formation was found to be inhibited. No fusion activity was observed with (H1062A, T1112A) HA-expressing cells, and with cells expressing the (H1062F, T1112V) mutant, low levels of polykaryon formation were detected only at pH 0.1 or more below WT HA. HA 2 residues 106 and 111 are at the ends of the peptide segment of the neutral pH coiled coil that undergoes a helix-to-loop transition upon acidification. Therefore, the changes at these positions may affect this particular molecular rearrangement or the formation of a low pH structure that is optimal for fusion in addition to causing decreased stability of HA and increased pH of conformational change as detected by ELISA and trypsin assays. No fusion activity was detected for trypsin treated non-recombinant vaccinia viruses, or for non-trypsin treated HA–expressing cells (data not shown). The results demonstrate that relative to WT HA, the pH of fusion as measured by polykaryon formation is consistent with the ΔpH data obtained using the conformational change assays (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Polykaryon formation by HA-expressing BHK cells following incubation at the indicated pH.

Discussion

A number of HA mutants that undergo acid-induced conformational changes and mediate membrane fusion at elevated pH have been reported (Cross et al., 2001; Daniels et al., 1985; Doms et al., 1986; Gething et al., 1986; Lin et al., 1997; Steinhauer, 1993; Steinhauer et al., 1995). The mutations responsible for this phenotype have been mapped to various locations throughout the length of the trimer, where they generally reside at interfaces between monomers, at HA1 and HA2 subunits within a monomer, or at regions between adjacent domains within a monomer that rearrange upon acidification. Presumably, such mutations cause localized changes between domains that rearrange during fusion, and destabilize the overall structure of the neutral pH HA.

The results reported here involve mutant HAs with changes at positions that reside in the vicinity of the fusion peptide of neutral pH HA which become altered with respect to solvent accessibility and chemical environment as a result of HA precursor cleavage. Compared to cleaved HA, the HA0 precursor is unresponsive to decreases in pH based on the assays described here, suggesting that changes in environment or newly formed contacts involving these residues may be critical for the induction of fusion. A total of 21 single, double, or triple mutant HAs were analyzed and a variety of phenotypes were observed with respect to the pH of acid-induced conformational changes and membrane fusion properties.

Among the residues chosen for analysis here were HA2 Asp 109, Asp 112, and Lys 51, which are completely conserved among all HA subtypes. Individual alanine substitutions for aspartic acid residues at HA2 positions 109 and 112 were found to increase the pH of fusion by 0.3 and 0.5 respectively. These results are in agreement with previous reports regarding the mutants D1092G, D1092E, D1122G, D1122E, and D1122N, which also lead to elevated fusion pH (Daniels et al., 1985; Hoffman, Kuntz, and White, 1997; Steinhauer, 1992; Steinhauer et al., 1996). In WT HA D1092 forms hydrogen bonds to Q1052 via a water molecule and also hydrogen bonds to the main chain amide group of residue 2 of the fusion peptide. The carboxylate oxygens of WT residue D1122 form four hydrogen bonds with the amide nitrogens of HA2 residues 3, 4, 5, and 6. The five hydrogen bonds formed by these aspartic acids to the fusion peptide are present in all HAs analyzed as illustrated for H1 and H3 subtype HAs in Figure 7. Presumably these interactions with the fusion peptide are important for stabilizing the neutral pH structure. Our results suggest that the additive effects created by double mutation (D1092A, D1122A) destabilize HA to such an extent that its are folding and transport to the cell surface is prohibited.

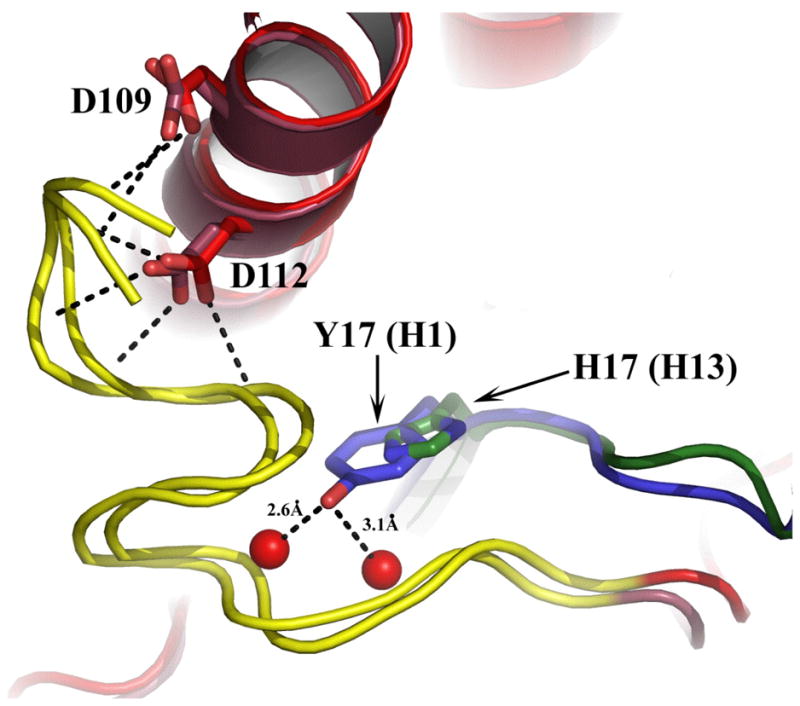

Figure 7.

Overlapping structural representation of H1 and H3 subtype HAs in the region of the fusion peptide. Fusion peptides are shown in yellow and long helices in red. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds. A single H-bond to the fusion peptide is formed by D109 in each HA (two shown, one for each HA subtype). Residue D112 forms four H-bonds in each case. The position of HA 1 His17 in the H3 HA is shown in green and the Tyr at the equivalent position in H1 HAs is shown in blue. The two direct H-bonds formed by Tyr to main chain oxygens of fusion peptide residues 10 and 12 are indicated.

HA2 position 51 is situated near the middle of the shorter of the two prominent α-helices of the neutral pH HA hairpin structure. In all HAs the conserved lysine side chain of HA2 51 is positioned similarly, extending into the solvent-occluded cavity towards HA2 residue 106 (Figure 2). In the H3 group HAs, HA2 106 is histidine, which forms a hydrogen bond with HA2 Lys 51. In H1 group HAs, HA2 106 is either lysine or arginine, with the side chains oriented away from HA2 Lys 51. When HA2 106 is Arg a hydrogen bond with HA2 Asp 109 of the adjacent monomer is formed (Russell et al., 2004). Our results with alanine and glutamic acid substitutions for HA2 Lys 51 indicate that these changes stabilize the neutral pH structure to some extent. Perhaps this results from the loss of repulsive interactions between this K512 and H1062 side chains that may develop during acidification (see Figure 2). This interpretation is consistent with results obtained with the HA2 106 His-to-Phe mutant, which also results in a marginal decrease in fusion pH. However, this effect is not observed with mutant HAs containing substitution of arginine or alanine at HA2 106, possibly due to other structural constraints.

Although it is not an ionizable residue, HA2 Gln 105 was chosen for analysis due to its position in the structure and based on phylogenetic considerations. Glutamine is present at this position in the H3 group HAs, and also in H9 clade HAs, whereas in other subtypes there is an acidic residue (usually glutamic acid). This is notable because for other positions in this region containing residues that segregate along group-specific lines, the H9 clade HAs fall into the H1 group (Figure 2). In WT H3 HAs the glutamine at HA2 position 105 forms a hydrogen bond with the amide nitrogen of HA1 residue 29 and has van der Waals contact with HA2 His 106 from an adjacent monomer, as well as forming hydrogen bonds to HA2 Asp 109 via water. Previously, a Q1052R mutation was shown to elevate fusion pH by 0.3, possibly by forming a salt bridge with the aspartic acid side chain of HA2 109 and altering its interactions with the fusion peptide. In the examples reported here, the glutamic acid substitution appears to have little effect on fusion pH when taking all three assays into consideration. However, the ELISA results in particular, suggest that an alanine substitution at HA2 position 105 may stabilize the structure of neutral pH HA to a small degree, possibly due to the packing of its methyl side chain against the hydrophobic isoleucine at HA1 position 29.

The most provocative of the residues analyzed here with respect to the induction of acid-induced conformational changes and membrane fusion involve positions HA1 17, and HA2 positions 106 and 111. These are strictly conserved along group-specific lines, and the presence or absence of histidine residues at these positions may be significant for triggering fusion. As a result of HA0 cleavage, the solvent-accessible histidine HA1 residue 17 becomes completely buried by the relocation of the fusion peptide into the trimer interior. Upon acidification, the newly formed contacts made by residue 17 in the cleaved HA are then lost and the fusion peptide is extruded as part of the fusion process. HA2 residues 106 and 111 are in a short segment of the long central helix of neutral pH HA that undergoes a helix-to-loop transition following acidification. This component of the conformational changes is critical for the fusion process as it is necessary to allow the C-terminal portion of HA to reorient by 180° to pack against the newly-elongated central coiled coil of low pH HA. This jackknife action leads to the formation of the rod-like structure that contains the hydrophobic transmembrane and fusion peptide domains at one end and the HA2 106 and 111-containing loop at the other. In H3 group HAs, HA1 17 and HA2 106 and 111 are invariably His, His, and Thr respectively. By contrast, in H1 group HAs the residues at these three positions are always Tyr, either Arg or Lys, and His.

In the studies reported here, the histidine to arginine substitution at HA2 106 essentially had no effect on the HA fusion pH phenotype. An alanine substitution at this position caused a slight increase in fusion pH, whereas the phenylalanine mutant at HA2 106 resulted in a reduction of between 0.1 and 0.2 in the pH at which conformational changes and polykaryon formation was observed. These results are likely to be due to interactions involving residues HA2 51, 105, and 109 as discussed above.

The results of mutations at HA1 position 17 indicate that this histidine residue may play a critical role in the initiation of membrane fusion for HAs of H3 group viruses. As discussed earlier, this is one of the group-specific residues that is almost completely buried due to the relocation of the fusion peptide following cleavage. In the neutral pH HA residue 17 forms hydrogen bonds via a water molecule to carbonyl oxygens of HA2 residues 6 and 10, and also hydrogen bonds with HA1 His 18 (Daniels et al., 1985). In the H1 group HAs, this residue is tyrosine. Previous studies with H3 subtype HAs have shown that substitution of HA1 His 17 with arginine or glutamine results in an increase of between 0.7 and 0.9 in the pH of membrane fusion (Daniels et al., 1985; Rott, 1984; Steinhauer et al., 1996; Wharton, Skehel, and Wiley, 1986), which makes them among the least stable HAs that have been observed in infectious viruses. Our results with the H171A substitution demonstrate a similar high pH of fusion phenotype, as alanine will not be capable of forming the equivalent hydrogen bonds to the fusion peptide or the H181 carbonyl oxygen. In all probability, this loss of hydrogen bonds is responsible for the reduced stability of the mutant HA. By contrast, substitution of tyrosine for HA1 His 17 led to a reduction by 0.3 of the pH at which conformational changes and membrane fusion were detected. Modelling of tyrosine at this position and structural comparisons with the HAs of H1 group subtypes indicate that the longer side chain could allow the hydroxyl group to form hydrogen bonds directly to residues 10 and 12 of the fusion peptide (Figure 7). Presumably, these direct bonds would be stronger than those formed via water when histidine is present at HA1 position 17, thus helping to account for the increased stability of the H171Y mutant. In addition, unlike histidine, tyrosine at this position would not have the potential to change protonation state at a pH relevant for fusion. These results suggest that for H3 group HAs, protonation of the histidine at HA1 position 17 is involved in the activation of membrane fusion.

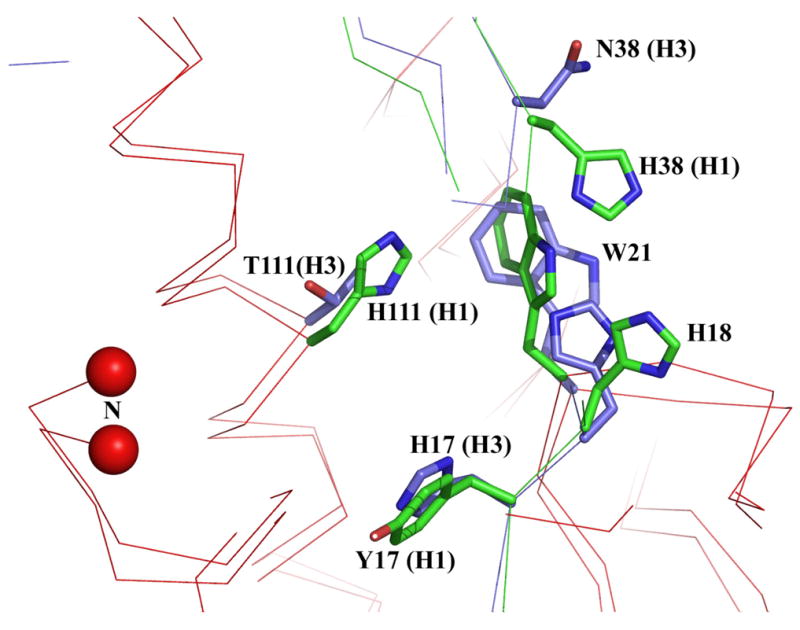

Substitutions at HA2 position 111 resulted in elevated fusion pH, by 0.6 for T1112H, 0.3 for T1112V, and 0.1 for T1112A, which suggests that this residue is also significant for the stability of the neutral pH structure. The identity of the residue at HA2 position 111 appears to dictate in part the group-specific structure of a four-residue complex composed of HA2 111, HA1 18, HA1 38, and HA2 Trp 21 (Russell et al., 2004). The orientation of the side chains of HA2 Trp 21 and HA1 18 are quite different depending on whether HA2 111 is threonine, as in the H3 group HAs, or histidine, as found in the H1 group (Figure 8). In HAs of the H3 group the Trp 21 and His 18 side chains are aligned with one another and oriented side-on towards Thr 111, and HA1 His 17 is positioned with the face of the imidazole directed toward Thr 111. In the H1 group HAs Trp 21 is located such that the indole side chain faces and completely buries the histidine at HA2 position 111. In these structures the HA1 His 18 side chain orients away from HA2 His 111. The structural differences in this region could indicate group-specific mechanisms for initiating fusion, and it is possible that protonation of HA2 His 111 may play a role similar to that suggested by our results for HA1 His 17 of H3 HA as a potential trigger residue. Our initial efforts to explore this possibility by mutagenesis of HA2 His 111 in the H2 subtype HA of A/Japan/305/57 virus have been inconclusive, as all single amino acid substitution mutants examined thus far fail to express on the cell surface in the native HA conformation (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Overlapping structural representation of H1 (green) and H3 (blue) subtype HAs in the region of HA1 residue 17 and HA2 residue 111. The location and side chain orientation of nearby residues HA1 18, HA1 38, and HA2 21 are positioned characteristically dependent on the residues present at HA1 17 and HA2 111. The HA2 N-terminus is indicated by the red balls.

Another indication that residues in this region of HA have evolved in coordinate fashion derives from our analysis of multiple mutants. For a number of these it is difficult to interpret the consequences for fusion of compound changes due to structural aberrations of the expressed proteins, which suggests that the cumulative effects of two or more changes in this region decreases HA stability to an extent that the proteins are misfolded or their conformations are altered during transport to the cell surface. Among the multiple mutants that expressed on cell surfaces appropriately, the results of mutants containing H1062A and T1112A were notable. Expressed individually, each mutation caused an increase in fusion pH of 0.1, and when expressed together, the double mutant (H1062A, T1112A) resulted in an increase in the pH of conformational change of 0.4 relative to WT. However, as components of a triple mutant containing the H171Y change, the pH of structural transition was nearly indistinguishable from WT. These results are consistent with observations on the stabilizing effects of the H171Y mutation and the additive contributions of mutations within localized regions (Steinhauer et al., 1996).

Overall, the results presented here are compatible with the observation that the amino acids at positions HA1 17 and HA2 111 have segregated as a unit during evolution due to functional compatibility. Perhaps HA1 His 17 plays a role in the initial trigger for membrane fusion of H3 group HAs, and in the H1 group HAs that have tyrosine at HA1 17, the histidine at HA2 111 plays a similar role. Initial structural perturbations involving these residues may alter the chemical environment of additional residues initiating a cascade of molecular transitions involving structural intermediates (Bottcher et al., 1999; Korte et al., 1999; Korte et al., 1997; Puri et al., 1990; Remeta et al., 2002). Secondary trigger residues or stabilizing mutations elsewhere in the HA trimer (Godley et al., 1992; Hoffman, Kuntz, and White, 1997; Kemble et al., 1992; Steinhauer et al., 1991a) may modulate the relative stability of structural intermediates or regulate transitional “checkpoints”. A greater appreciation of the mechanisms by which the conformational changes of HA are triggered and the structural intermediates involved should aid in the further design and development of anti-influenza drugs that inhibit fusion (Bodian et al., 1993; Cianci et al., 1999; Combrink et al., 2000; Hoffman, Kuntz, and White, 1997; Luo et al., 1997; Yu et al., 1999).

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis and Expression of HAs

The cDNA clones of the influenza virus strain X-31 (containing the HA and NA genes from the H3N2 subtype virus A/Aichi/2/68 and other genes from the H1N1 subtype virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34) were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The presence of the desired mutations and the absence of extraneous mutations were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing of entire HA coding regions. The mutant cDNAs were expressed as recombinant vaccinia viruses using the plaque-selection system (Blasco and Moss, 1995). The generated viruses were propagated on CV1 cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

Cell Surface Expression

HA cell surface expression was analyzed using a trypsin cleavage assay with recombinant vaccinia-infected CV1 cells as described previously (Steinhauer et al., 1995) with a few modifications. The only difference is that blots were developed using chemiluminescence rather than radiolabeled second antibody. Following electrophoresis, blots were incubated with anti-HA rabbit polyclonal rabbit serum, washed, then incubated with a Protein A–HRP conjugate (Sigma cat# P8651). Blots were developed with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Reagent (Amersham Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative cell surface expression by ELISA was carried out on recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing HeLa cells using a panel of monoclonal antibodies that recognize distinct antigenic regions of wild type HA as described (Steinhauer et al., 1991b).

Conformational Change Assays

Trypsin susceptibility: Recombinant vaccinia virus-infected CV1 cells were used for trypsin susceptibility assays to determine the pH of conformational changes for WT and mutant HAs. Approximately 24 hrs post-infection, HA-expressing infected cells were treated with trypsin (Sigma) at 5 μg/ml, 10 min, 37°C, washed, and incubated at various pH values for 5 min at 37°C. The medium was then returned to neutral pH and the monolayer was incubated in the presence of trypsin (5 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS, and lysates were analyzed following SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions by immunoblot assay using anti-HA rabbit polyclonal primary antibody and a Protein A-HRP conjugate. Blots were developed using ECL and intensities of HA1 and HA2 bands were quantified on VersaDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad) with the Quantity One analysis software.

ELISA

Conformation change analysis by ELISA was performed on recombinant vaccinia-infected HeLa cell monolayers as described (Steinhauer et al., 1991b) using monoclonal antibodies HC3 and HC67. HC3 recognizes both native and low pH HA, while HC67 recognizes only the native conformation.

Fusion Assay

The pH of membrane fusion was assayed by polykaryon formation as described previously (Li et al., 2006; Steinhauer et al., 1991b), except that the pH was reduced for 30 seconds.

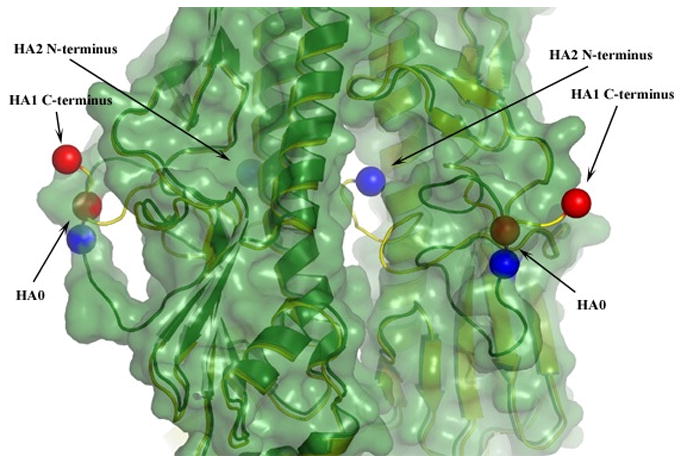

Figure 1.

Superimposed ribbon diagrams of uncleaved HA0 (green) and cleaved HA (yellow), which deviate only at positions 323–329 of HA1 and 1–12 of HA2. To highlight the structural relocations that occur upon cleavage, for two of the monomers the positions of the C-termini of HA1 and the N-termini of HA2 are indicated by red and blue balls respectfully. The structure of uncleaved HA0 is also shaded to indicate van-der-Waals radii. This highlights the loop structure of HA0 and the central cavity into which the N-terminal portion of the HA2 fusion peptide relocates following cleavage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Konrad Bradley, Jenna Froelich, and Dana Shaw for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grants AI66870 and AI/EB53359 to D.A.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Appleyard G, Maber HB. Plaque formation by influenza viruses in the presence of trypsin. J Gen Virol. 1974;25(3):351–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-25-3-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard RJ, Elleder D, Young JA. Avian sarcoma and leukosis virus-receptor interactions: from classical genetics to novel insights into virus-cell membrane fusion. Virology. 2006;344(1):25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizebard T, Barbey-Martin C, Fleury D, Gigant B, Barrere B, Skehel JJ, Knossow M. Structural studies on viral escape from antibody neutralization. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;260:55–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05783-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizebard T, Gigant B, Rigolet P, Rasmussen B, Diat O, Bosecke P, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Knossow M. Structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with a neutralizing antibody. Nature. 1995;376(6535):92–4. doi: 10.1038/376092a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco R, Moss B. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene. 1995;158(2):157–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodian DL, Yamasaki RB, Buswell RL, Stearns JF, White JM, Kuntz ID. Inhibition of the fusion-inducing conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin by benzoquinones and hydroquinones. Biochemistry. 1993;32(12):2967–78. doi: 10.1021/bi00063a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottcher C, Ludwig K, Herrmann A, van Heel M, Stark H. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at neutral and at fusogenic pH by electron cryo-microscopy. FEBS Lett. 1999;463(3):255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371(6492):37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lee KH, Steinhauer DA, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell. 1998;95(3):409–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianci C, Yu KL, Dischino DD, Harte W, Deshpande M, Luo G, Colonno RJ, Meanwell NA, Krystal M. pH-dependent changes in photoaffinity labeling patterns of the H1 influenza virus hemagglutinin by using an inhibitor of viral fusion. J Virol. 1999;73(3):1785–94. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1785-1794.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman PM, Lawrence MC. The structural biology of type I viral membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(4):309–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrink KD, Gulgeze HB, Yu KL, Pearce BC, Trehan AK, Wei J, Deshpande M, Krystal M, Torri A, Luo G, Cianci C, Danetz S, Tiley L, Meanwell NA. Salicylamide inhibitors of influenza virus fusion. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10(15):1649–52. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross KJ, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Steinhauer DA. Studies on influenza haemagglutinin fusion peptide mutants generated by reverse genetics. Embo J. 2001;20(16):4432–42. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RS, Douglas AR, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Analyses of the antigenicity of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH optimum for virus-mediated membrane fusion. J Gen Virol. 1983;64(Pt 8):1657–62. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-8-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RS, Downie JC, Hay AJ, Knossow M, Skehel JJ, Wang ML, Wiley DC. Fusion mutants of the influenza virus hemagglutinin glycoprotein. Cell. 1985;40(2):431–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doms RW. Unwelcome guests with master keys: how HIV enters cells and how it can be stopped. Top HIV Med. 2004;12(4):100–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doms RW, Gething MJ, Henneberry J, White J, Helenius A. Variant influenza virus hemagglutinin that induces fusion at elevated pH. J Virol. 1986;57(2):603–13. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.603-613.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutch RE, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA. Virus membrane fusion proteins: biological machines that undergo a metamorphosis. Biosci Rep. 2000;20(6):597–612. doi: 10.1023/a:1010467106305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp LJ, Delos SE, Park HE, White JM. The many mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;285:25–66. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp LJDS, Park HE, White JM. The many mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;285:25–66. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D, Rimmelzwaan GF, Olsen B, Osterhaus AD. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from blackheaded gulls. J Virol. 2005;79(5):2814–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2814-2822.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Russell RJ, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Vasisht N, Steinhauer DA, Daniels RS, Elliot A, Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science. 2004;303(5665):1838–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1093155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething MJ, Doms RW, York D, White J. Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion: site-specific mutagenesis of the hemagglutinin of influenza virus. J Cell Biol. 1986;102(1):11–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley L, Pfeifer J, Steinhauer D, Ely B, Shaw G, Kaufmann R, Suchanek E, Pabo C, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, et al. Introduction of intersubunit disulfide bonds in the membrane-distal region of the influenza hemagglutinin abolishes membrane fusion activity. Cell. 1992;68(4):635–45. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus haemagglutinin structures: possible origin of influenza subtypes. Embo J. 2002;21(5):865–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SC. Mechanism of membrane fusion by viral envelope proteins. Adv Virus Res. 2005;64:231–261. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(05)64007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LR, Kuntz ID, White JM. Structure-based identification of an inducer of the low-pH conformational change in the influenza virus hemagglutinin: irreversible inhibition of infectivity. J Virol. 1997;71(11):8808–20. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8808-8820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Sivaramakrishna RP, Ludwig K, Korte T, Bottcher C, Herrmann A. Early steps of the conformational change of influenza virus hemagglutinin to a fusion active state: stability and energetics of the hemagglutinin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka Y, Yamnikova S, Chambers TM, Lvov DK, Webster RG. Molecular characterization of a new hemagglutinin, subtype H14, of influenza A virus. Virology. 1990;179(2):759–67. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90143-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemble GW, Bodian DL, Rose J, Wilson IA, White JM. Intermonomer disulfide bonds impair the fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 1992;66(8):4940–50. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4940-4950.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian M. Class II virus membrane fusion proteins. Virology. 2006;344(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk HD, Rott R, Orlich M, Blodorn J. Activation of influenza A viruses by trypsin treatment. Virology. 1975;68(2):426–39. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte T, Ludwig K, Booy FP, Blumenthal R, Herrmann A. Conformational intermediates and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 1999;73(6):4567–74. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4567-4574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte T, Ludwig K, Krumbiegel M, Zirwer D, Damaschun G, Herrmann A. Transient changes of the conformation of hemagglutinin of influenza virus at low pH detected by time-resolved circular dichroism spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(15):9764–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RA, Paterson RG, Jardetzky TS. Paramyxovirus membrane fusion: lessons from the F and HN atomic structures. Virology. 2006;344(1):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowitz SG, Choppin PW. Enhancement of the infectivity of influenza A and B viruses by proteolytic cleavage of the hemagglutinin polypeptide. Virology. 1975;68(2):440–54. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Li ZN, Yao Q, Yang C, Steinhauer DA, Compans RW. Murine leukemia virus R Peptide inhibits influenza virus hemagglutinin-induced membrane fusion. J Virol. 2006;80(12):6106–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02665-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YP, Wharton SA, Martin J, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Steinhauer DA. Adaptation of egg-grown and transfectant influenza viruses for growth in mammalian cells: selection of hemagglutinin mutants with elevated pH of membrane fusion. Virology. 1997;233(2):402–10. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G, Torri A, Harte WE, Danetz S, Cianci C, Tiley L, Day S, Mullaney D, Yu KL, Ouellet C, Dextraze P, Meanwell N, Colonno R, Krystal M. Molecular mechanism underlying the action of a novel fusion inhibitor of influenza A virus. J Virol. 1997;71(5):4062–70. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4062-4070.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobusawa E, Aoyama T, Kato H, Suzuki Y, Tateno Y, Nakajima K. Comparison of complete amino acid sequences and receptor-binding properties among 13 serotypes of hemagglutinins of influenza A viruses. Virology. 1991;182(2):475–85. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri A, Booy FP, Doms RW, White JM, Blumenthal R. Conformational changes and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin of the H2 and H3 subtypes: effects of acid pretreatment. J Virol. 1990;64(8):3824–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3824-3832.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remeta DP, Krumbiegel M, Minetti CA, Puri A, Ginsburg A, Blumenthal R. Acid-induced changes in thermal stability and fusion activity of influenza hemagglutinin. Biochemistry. 2002;41(6):2044–54. doi: 10.1021/bi015614a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohm C, Zhou N, Suss J, Mackenzie J, Webster RG. Characterization of a novel influenza hemagglutinin, H15: criteria for determination of influenza A subtypes. Virology. 1996;217(2):508–16. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rott R, Orlich M, Klenk H-D, Wang ML, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies on the adaptation of influenza viruses to MDCK cells. EMBO J. 1984;3:3329–3332. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Skehel JJ. H1 and H7 influenza haemagglutinin structures extend a structural classification of haemagglutinin subtypes. Virology. 2004;325(2):287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Viral entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;285:1–23. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel JJ, Bayley PM, Brown EB, Martin SR, Waterfield MD, White JM, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. Changes in the conformation of influenza virus hemagglutinin at the pH optimum of virus-mediated membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(4):968–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304(5668):237–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1094823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer D, Sauter NK, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and cell entry by influenza viruses. Seminars in Virology. 1993;3:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA. Receptor binding and cell entry by influenza viruses. Sem Virology. 1992;3:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA, Martin J, Lin YP, Wharton SA, Oldstone MB, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies using double mutants of the conformational transitions in influenza hemagglutinin required for its membrane fusion activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(23):12873–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies of the membrane fusion activities of fusion peptide mutants of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 1995;69(11):6643–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6643-6651.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Hay AJ. Amantadine selection of a mutant influenza virus containing an acid-stable hemagglutinin glycoprotein: evidence for virus-specific regulation of the pH of glycoprotein transport vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991a;88(24):11525–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA, Wharton SA, Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. Deacylation of the hemagglutinin of influenza A/Aichi/2/68 has no effect on membrane fusion properties. Virology. 1991b;184(1):445–8. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90867-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies of influenza haemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion. Virology. 1986;149(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Wilson IA. Anti-peptide antibodies detect steps in a protein conformational change: low-pH activation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(6 Pt 2):2887–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. The structure and function of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:365–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature. 1981;289(5796):366–73. doi: 10.1038/289366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley NG, Brown EB, Daniels RS, Douglas AR, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Electron microscopy of influenza haemagglutinin-monoclonal antibody complexes. Virology. 1983;131(2):308–14. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu KL, Ruediger E, Luo G, Cianci C, Danetz S, Tiley L, Trehan AK, Monkovic I, Pearce B, Martel A, Krystal M, Meanwell NA. Novel quinolizidine salicylamide influenza fusion inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9(15):2177–80. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]