Abstract

The arterial system is subjected to cyclic strain because of periodic alterations in blood pressure, but the effects of frequency of cyclic strain on arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) remain unclear. Here, we investigated the potential role of the cyclic strain frequency in regulating SMC alignment using an in vitro model. Aortic SMCs were subject to cyclic strain at one elongation but at various frequencies using a Flexercell Tension Plus system. It was found that the angle information entropy, the activation of integrin-β1, p38 MAPK, and F/G actin ratio of filaments were all changed in a frequency-dependent manner, which was consistent with SMC alignment under cyclic strain with various frequencies. A treatment with anti-integrin-β1 antibody, SB202190, or cytochalasin D inhibited the cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment. These observations suggested that the frequency of cyclic strain plays a role in regulating the alignment of vascular SMCs in an intact actin filament-dependent manner, and cyclic strain at 1.25 Hz was the most effective frequency influencing SMC alignment. Furthermore, integrin-β1 and p38 MAPK possibly mediated cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment.

INTRODUCTION

Arterial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are aligned primarily in the circumferential direction in the media of artery. The circumferential orientation and structural network of the SMC layers are very important for maintaining the mechanical strength and function of the arterial wall and also provide the flexibility required for pulsatile blood flow (1–4). The distinct patterns of SMC orientation in the arterial wall should be a result of the complicated mechanical environment in vivo, especially the cyclic nature of vessel stretch resulting from arterial pressure waveforms generated by the left ventricle (5,6).

The mechanical stimuli from pulsatile blood flow were considered to be one of the key factors in regulating vascular remodeling during development and pathogenesis (7,8). Each pulsatile mechanical strain includes at least three elements: magnitude, frequency, and duration. Cultured SMCs in vitro can be induced to reorient to a uniform alignment almost perpendicular to the direction of principal uniaxial mechanical stretch (4,9,10). This response of cell reorientation depends on the stretching magnitude (11,12) and is consistent with the response found in other types of cells that also align in the direction of the minimum strain (12–14). These investigations provide useful information for understanding the role of cyclic strain in regulating the alignment of vascular SMCs. However, most previous studies focused on the magnitude and exposure time of mechanical stretch, and the effect of the frequency of cyclic strain on vascular cell alignment remains poorly understood.

Only several signaling pathways that were involved in regulating strain-induced cell alignment have been reported to date. Strain-induced SMC alignment is dependent on the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) but not S6 kinase (15), protein kinase (PK) A, or PKC (16). It has also been shown that cytoskeleton reorganization began before cell reorientation, and treatment with nocodazole or cytochalasin to disrupt the cytoskeleton could also attenuate stress-induced cell orientation (17,18). Integrins have been shown to regulate the transmission of substrate strain to the cytoskeleton (19). Extracellular matrix can interact with the extracellular domain of integrins, and their cytoplasmic domain links to cytoskeletal proteins and focal adhesion (FA) (20–22). Depending on their unique structural features, integrins are able to mediate outside-in and inside-out signaling. The integrin activation induced by extracellular stimuli results in the activation of intracellular signaling cascades. On the other hand, the activation of integrin can also be modulated by intracellular signals through FA (21,22). However, the function of these two pathways in the regulation of cyclic strain-frequency-dependent SMC alignment remains unknown, and the difference of mechanotransduction between the frequency and magnitude of strain-induced cell alignment still needs to be elucidated.

In our study, we investigated the role of the cyclic strain frequency in regulating the alignment of arterial SMCs and studied the function of integrin-β1, p38 MAPK, and actin filaments in mediating cyclic strain-frequency-dependent SMC alignment. These investigations may help to explain vascular remodeling induced by the mechanical stimuli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Vascular SMCs were isolated from the thoracic aorta of 250- to 300-g male Sprague-Dawley rats by collagenase and elastase digestion. Prepared cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco BRL), penicillin 100 U/ml, and streptomycin 100 μg/ml at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells from confluent primary cultures were digested with trypsin/EDTA and reseeded in DMEM/10% FBS. The identity of SMCs was verified by positive immunohistochemical testing with α-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). SMCs from passages 6 to 10 were used for experiments.

Application of cyclic strain

SMCs were seeded on an elastic silicone membrane coated with collagen I (BioFlex, Flexcell International, Hillsborough, NC) at a density of 3×105 cells/well (diameter 35mm) for culture. When reaching 80% confluence, the cultured cells were pretreated with serum-free DMEM for 24 h for synchronization and stretched using a Flexercell Tension Plus system (FX-4000T, Flexcell International). The silicone membranes with cultured cells were then placed on a vacuum manifold situated in an incubator. When a precise vacuum was applied to the bottoms, controlled by a computer, the silicone membranes were deformed to a prearranged elongation percentage and returned to their original conformation once the vacuum was released. After this procedure, the cells remain adherent, and the deformation of the membrane is directly transmitted to the SMCs. With a 25-mm loading post and Bioflex Plates, the system provides approximate equibiaxial extension in the central region of the membrane above the post and provides biaxial strain that has a major part in the radial and a minor one in the circumferential direction within the periphery membrane field away from the post (23). In the experiments presented here, the membranes were set in the computer to deform to 10% elongation in the central region, which was ∼14% of radial strain and 5% of circumferential strain in the periphery membrane field away from the post (23), at 30 cycles/min (0.5 Hz group, 1 s elongation alternating with 1 s relaxation), 60 cycles/min (1.0 Hz group, 0.5 s elongation alternating with 0.5 s relaxation), 90 cycles/min (1.5 Hz group, 0.33 s elongation alternating with 0.33 s relaxation), and 120 cycles/min (2.0 Hz group, 0.25 s elongation alternating with 0.25 s relaxation). As a control, the same elongation stretch was constantly applied throughout the experiment, with no variation in frequency (C group). Moreover, cells cultured statically on the same type of plates, without stretch, were also observed (S group).

Measurement of SMC average oriented angle

After stretching for a prearranged time, four symmetrical eyeshots at the periphery of each culture well were located accurately with coordinates and photographed under a microscope (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan). The distance from the middle point of the photo to the center of the culture well membrane was set to be 13.2 mm, which was three-fourths of the radius of the culture well, and the middle vertical line of each photo was fixed consistently with the radial direction of the culture well. The outline of each cell was identified, and the angle of the cell was determined using Image-Pro Plus 4.5.1 software. The angle was defined as that between the long axis of the cell and the radial direction. The distribution of cell orientation was depicted by counting the number of cells that fell into six orientation regions, each covering 15° from 0° (with the cell parallel to the radial direction) to 90° (with the cell perpendicular to the radial direction).

Inhibition studies

To determine the effects of integrin-β1, phosphoinositide 3 (PI3)-kinase/Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), and p38 MAPK in the process of frequency-dependent SMC alignment, SMCs were incubated with 10 μg/ml specific anti-integrin-β1-blocking antibody (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), 10 μM SB 202190, an inhibitor of p38 MAPK, 10 μM PD 98059, an inhibitor of ERK, or 200 nM wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3-K/Akt (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), respectively, for an additional hour before being subjected to the mechanical strain. Then the SMCs were subjected to the cyclic strain at the frequency of 1.25 Hz for 12 h, with each inhibitor still in the medium (24). SMCs in a medium containing the same concentration of the solvent DMSO (Sigma) but without inhibitors mentioned above were also preincubated for 1 h and then stretched under the same strain condition.

To determine the effect of the filament system in the process of frequency-dependent SMC alignment, SMCs were incubated with 100 nM cytochalasin D (Sigma) for 1 h and subjected to cyclic strain with the frequencies of 1.25 Hz for 12 h with the cytochalasin D still in the medium or with frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz for 1, 6, and 12 h, respectively, in a medium without cytochalasin D. SMCs with DMSO (Sigma) but without cytochalasin D were also observed as mentioned above.

Western blot analysis

After being stretched at frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz, respectively, for 1 h, cells of the entire surface from each culture well were lysed and harvested for Western blotting as previously described (24). The protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method with BSA as a standard (Beckman Coulter, DU800, Fullerton, CA). Proteins (30 μg/lane) were immunoblotted with antibodies against phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Blots were then stripped and reprobed with antibodies against total-p38 MAPK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA), the signals were detected by nitroblue tetrazolium-bromochloroindolyl phosphate (Bio Basic, Mississauga, ON).

Flow cytometry

SMCs with integrin activation were tested by the flow cytometry technique. After having been stretched with frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz for 1, 6, and 12 h, respectively, SMCs of the entire surface were collected by trypsin digestion and incubated with an anti-integrin-β1 antibody (HUTS21, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, 2.5 μg/5 × 105 cells) at 37°C for 30 min and subsequently incubated with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with 1.5% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Vascular SMCs incubated only with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody were used as control.

F/G actin ratio assay

After SMCs had been stretched under the frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz for 1, 6, and 12 h, respectively, a lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5% Triton X-100 was gently added to the cell wells, and the cells were incubated with this buffer at 37°C for 5 min. The lysis buffer was then gently collected and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The lysates remaining in the wells were scraped into same volume of another lysis buffer containing 25 nM Tris-HCl, 0.4 M NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin and then also centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min after being redissolved for 30 min. The supernatants of the former and latter were collected separately as the cytosol protein and cytoskeleton, which also included membranes and nuclei protein.

The amounts of F-actin in the cytoskeleton and G-actin in the cytosol fraction were determined by immunoblotting. The two fractions were separated in one 10% SDS-PAGE at the same time. After incubation with an anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma) and subsequent incubation with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch), successively, the signals were detected by nitroblue tetrazolium–bromochloroindolyl phosphate (Bio Basic).

Immunocytochemistry

The attached SMCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 for 5 min, then blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA for 30 min. Integrin was stained with an anti-integrin-β1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch), and filamentous actin was stained with rhodamine phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The cell was visualized and photographed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71).

Statistical analysis

At least four independent experiments were performed for each study. Cell measurements were made in all photographs, and each of them contains more than 200 cells. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test was used to compare the data among groups using software SAS. P values of <0.05 and <0.01 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Frequency of cyclic strain-induced changes in SMC alignment

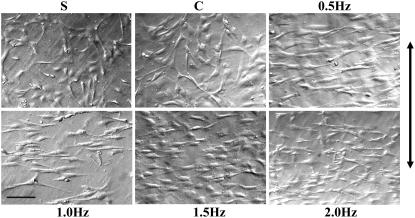

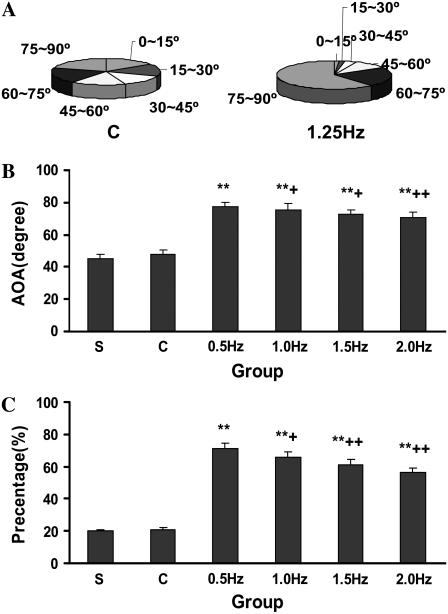

After exposure to cyclic stretch for 24 h under four different frequencies, the cells showed a more spindle-shaped appearance and a consistent orientation, which was nearly perpendicular to the radial direction, whereas the cells of the control and S groups still aligned randomly (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2 A, after exposure to frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 Hz, respectively, a higher percentage of the cells were observed in higher angle ranges, whereas the control and S groups showed almost average distributions in each angle range. A higher average oriented angle (AOA) was induced in the cells stretched with a frequency of 0.5 Hz than in the cells stretched with other frequencies (Fig. 2 B), and this group also had the highest percentage of cells in the angle range from 75° to 90°, which could be considered as perpendicular to the radial direction (Fig. 2 C).

FIGURE 1.

Change of SMC alignment after stretching at a variety of frequencies. SMCs were cultured on collagen I-coated elastic membranes and subjected to cyclic stretch with frequencies 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 Hz, respectively, for 24 h. Photographs were taken under microscopy, and their middle vertical lines were fixed consistently with the radial direction of the culture membrane. SMCs without stretch (S group) or statically stretched without variation in frequency (C group) were also observed. Bar, 200 μm, and the arrow indicates the radial direction.

FIGURE 2.

Change of SMC orientation after stretching at a variety of frequencies. The angle of SMCs (0–90°) was divided into six angle regions, each covering 15°. The percentages of SMCs within the C and 1.5-Hz groups were calculated after stretching for 24 h (A). The AOA (B) and the percentage of SMCs from 75° to 90° (C) were contrasted between groups. Results are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 versus the C group; +p < 0.05; ++p < 0.01 versus the 0.5-Hz group, n = 4.

Description of the time-dependent process of frequency-induced SMC alignment

To assess the change of SMC alignment as a whole system, Shannon's concept of information entropy was applied here. This describes the regular degree of all individuals within a certain system (25). The angle of SMCs, which were stretched for 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h with the strain frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 Hz, was divided into six orientation regions, and the proportion of cells in each region is indicated as Pi (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, and P6, respectively), with the total being 100%. Therefore, the angle information entropy (AIE) can be calculated from Eq. 1, where E is AIE:

|

(1) |

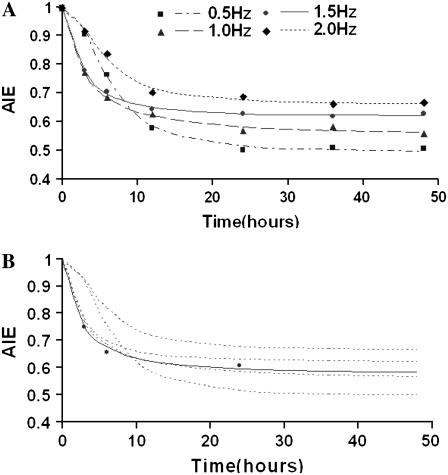

The value of AIE lies between 0 and 1, which means something more regular when the value is closer to 0. As shown in Fig. 3 A, the AIE showed a nonlinear dependence on frequency. The AIE of each group receiving cyclic strain decreased rapidly and then remained at a certain level, which was lowest in the 0.5 Hz group and highest in the 2.0 Hz group after 12–24 h. The frequency of 1.0 Hz had the fastest rate of decrease up to 12 h within four groups. However, in the C group, there was almost no change in the AIE.

FIGURE 3.

Time courses of AIE change with different frequencies of cyclic stretch from the experimental and mathematic models. (A) SMCs were stretched for 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h with frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 Hz, respectively, and the C group was also observed at the same time points. Based on the data of the percentage of cells in each angle interval, the AIE was calculated and contrasted. The time courses of AIE were fitted with a logistic curve, and the frequency and each parameter were then fitted again using the power function or binomial equation. The lines are fitted curves, and spots represent the corresponding experimental data; n = 4. (B). Prediction and experimental verification of AIE. The AIE under the cyclic stretch frequency of 1.2 Hz were predicted, and for experimental verification, SMCs were stretched with a frequency of 1.2 Hz for 3, 6, and 24 h, respectively. The dotted lines are fitted curves for each experimental group, the solid line is a predicted curve for 1.2 Hz, and spots represent experimental data; n = 7.

Mathematical fitting of AIE with logistic curves

After carefully analyzing the characteristics of AIE under the different frequency of cyclic strain, we found that the change of AIE could be fitted by a logistic curve using a software package (Originpro):

|

(2) |

where t is the time, A1, A2, t0, and p are state variables (Table 1), which are the functions of the frequency F (Hz) and can be expressed as follows:

|

(2.1) |

|

(2.2) |

|

(2.3) |

|

(2.4) |

Lines in Fig. 3 A showed the results of fitting the data and AIE.

TABLE 1.

State variables of AIE under different frequencies

| 0.5 Hz | 1.0 Hz | 1.5 Hz | 2.0 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.99320 | 0.99796 | 0.99784 | 0.99413 |

| A2 | 0.49208 | 0.54617 | 0.61485 | 0.65824 |

| T0 | 6.20255 | 2.95498 | 2.47225 | 5.78560 |

| P | 2.29435 | 1.17131 | 1.46147 | 2.08603 |

| R2 | 0.99791 | 0.9974 | 0.99838 | 0.99068 |

Prediction and experimental verification of AIE of SMCs

Based on the mathematical model above, the corresponding frequencies when parameters t0 and p reach their maxima can be obtained, which are 1.28 Hz for t0, and 1.27 Hz for p. Therefore, we chose 1.2 Hz to be the predicted frequency at which cells should exhibit a faster rate of change of AIE within the first 12 h than at the four frequencies used before and reach their maximum AIE, which lies between 1.0 and 1.5 Hz after 12–24 h. The predicted AIE under a frequency of 1.2 Hz at 3, 6, and 24 h are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison between predicted and experimental AIE

| 1.2 Hz, 3 h | 1.2 Hz, 6 h | 1.2 Hz, 24 h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.60 |

| From experiment | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.62 |

SMCs were cultured and stretched under the above-mentioned conditions, and the AIE was calculated (Table 2). Fig. 3 B shows that the predicted distributions under a frequency of 1.2 Hz and at the same elongation were not significantly different from the experimental distributions.

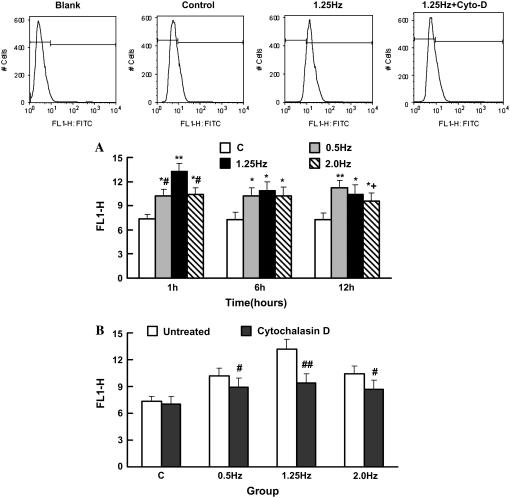

Activation of integrin-β1 under different frequencies of cyclic strain

To investigate a role of the frequency of cyclic strain in regulating integrin-β1 activation in SMCs, the HUTS21 antibody, which recognizes the active conformation of integrin-β1, was used for the flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the expression of integrin-β1 was enhanced in every group with the frequency. The 1.25-Hz group showed maximal activation of integrin-β1 at 1 h, whereas the 0.5 Hz group showed the highest activation at 12 h (see Fig. 9).

FIGURE 4.

Activation of integrin-β1 in SMCs under different frequencies of cyclic strain analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) SMCs were analyzed by flow cytometry after stretched for 1, 6, and 12 h with frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz, respectively. Results are mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus C group of the same time point; +p < 0.05 versus 0.5-Hz group of the same time point; #p < 0.05 versus 1.25-Hz group of the same time point; n = 4. (B) Activation of integrin-β1 in SMCs stretched for 1 h without cytochalasin D after pretreatment with cytochalasin D for 1 h. Results are mean ± SD. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 versus the untreated group of the same time point; n = 4.

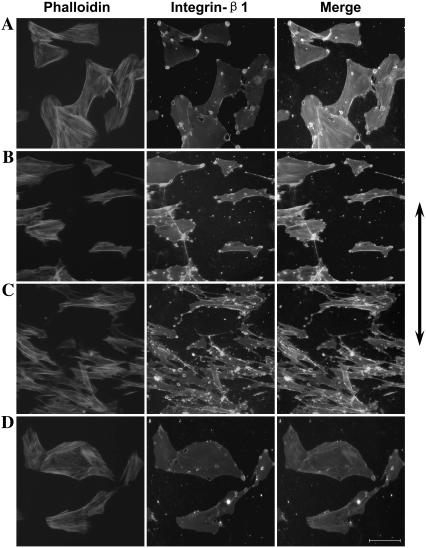

FIGURE 9.

Immunocytochemistry result of actin and integrin-β1. (A) C group, in which SMCs were stretched without frequency. (B) SMCs were stretched at 1.25 Hz for 6 h. (C) SMCs were stretched at 1.25 Hz for 12 h. (D) SMCs were stretched at 1.25 Hz for 6 h after pretreatment with cytochalasin D for 1 h. The cells were fixed, and actin filament was stained with red rhodamine-phalloidin, and integrin-β1 was stained with an anti-integrin-β1 antibody and green FITC-IgG, respectively. Photographs were taken with the fluorescence microscope. Bar, 100 μm, and the arrow indicates the radial direction.

P38 MAPK, but not ERK or PI3-K/AKT, is involved in cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment

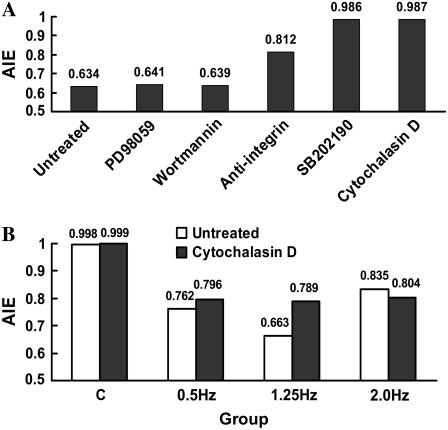

To explore which signaling molecule mediated cyclic strain-induced SMC alignment, specific inhibitors of p38 MAPK, ERK, or PI3-K/Akt were used to block corresponding pathways. The results reveal that 10 μM SB 202190, 10 μM PD 98059, or 200 nM wortmannin could specifically block the strain-mediated activation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, or Akt measured by their phosphorylation forms, respectively (24). But only inhibition of the p38 MAPK pathway significantly prevented decreasing of AIE by the various frequencies of strain, whereas the inhibition of ERK1/2 or Akt had no discernible effect on AIE (Fig. 5 A).

FIGURE 5.

Change of AIE of SMCs under cyclic strain after pretreatment with specific inhibitors. (A) SMCs were stretched after pretreatment with different inhibitors for 1 h and stretched at 1.25 Hz for 12 h with specific inhibitors in the medium. (B) Change of AIE of SMCs stretched at different frequencies for 6 h without cytochalasin D in the medium after pretreatment with cytochalasin D for 1 h, n = 4.

To investigate the effect of the cyclic strain frequency on p38 MAPK activation in SMCs, proteins from each group were immunoblotted with antibody against phospho-p38 MAPK. p38 MAPK phosphorylation was enhanced in each frequency group, and the 1.25-Hz group showed maximal phosphorylation after having been stretched for 1 h (see Fig. 8 A).

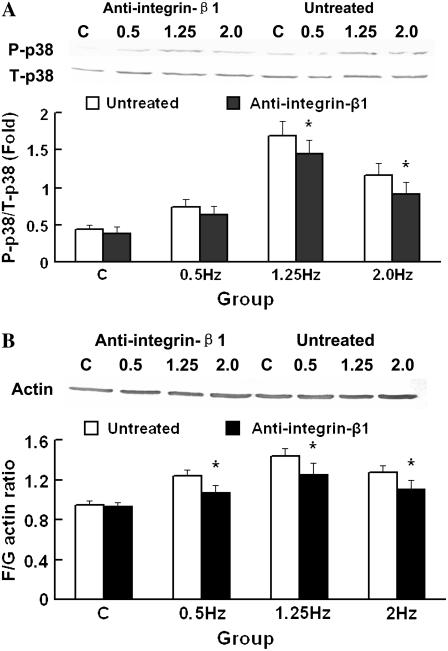

FIGURE 8.

Change of phospho-p38 MAPK (P-p38) induction and F/G-actin ratio of SMCs stretched after having been inhibited with anti-integrin-β1 blocking antibody. (A) Western blotting result from P-p38 after stretching for 1 h with anti-integrin-β1 blocking antibody, and total-p38 MAPK (T-p38) served as loading control. (B) The F/G-actin ratio of SMCs after stretching for 12 h with anti-integrin-β1 blocking antibody. Each column represents the mean ± SD. +p < 0.05; ++p < 0.01 versus the C group; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01 versus the 1.25 Hz group; *p < 0.05 versus the untreated group at the same frequency; n = 5.

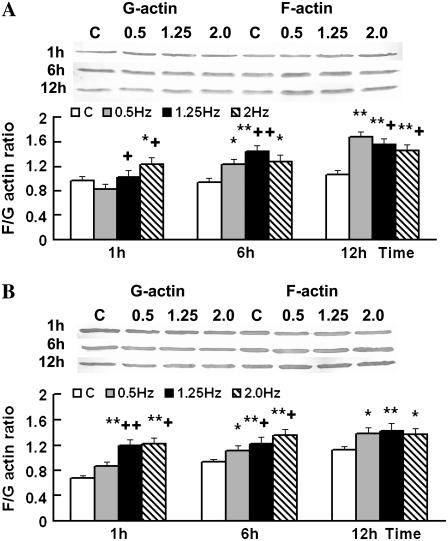

Different frequencies of cyclic strain affected the F/G-actin ratio

From our results above, we ascertained that 1.25 Hz might be the most effective frequency in the range tested. Our measurements of the F/G actin ratio of SMCs under the frequencies of 0.5, 1.25, and 2.0 Hz of cyclic strain for 1, 6, and 12 h show that the cyclic strain increased the F/G actin ratio significantly at 6 and 12 h, whereas almost no change was found in the control group. The 1.25-Hz group had the highest F/G ratio after being stretched for 6 h (Fig. 6 B), whereas after 12 h, a frequency of 0.5 Hz produced the highest ratio, and 2.0 Hz the lowest ratio, among the four groups (Fig. 7 A).

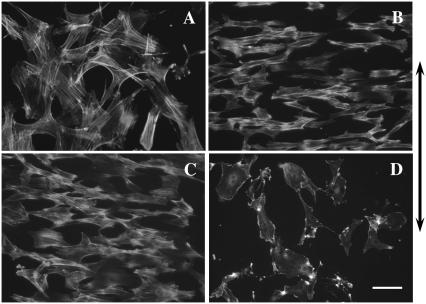

FIGURE 6.

Change of filament orientation after cyclic stretching. (A) Control group, which was statically stretched without frequency for 12 h. (B) SMCs stretched at the frequency of 1.25 Hz for 6 h. (C) SMCs stretched for 12 h at the frequency of 1.25 Hz after pretreatment with cytochalasin D for 1 h. (D) SMCs were stretched for 12 h at the frequency of 1.25 Hz with cytochalasin D in the medium throughout. Stained with rhodamine phalloidin. Bar, 100 μm, and the arrow indicates the radial direction of the culture membrane.

FIGURE 7.

F/G-actin ratio changed with different frequencies of cyclic strain while disturbed by cytochalasin D. SMCs were stretched for 1, 6, and 12 h (A) or stretched for the same time after pretreatment with cytochalasin D for 1 h (B). G-actin in cytosol protein and F-actin in cytoskeleton protein were immunoblotted with anti-β-actin antibody. Each column represents the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 versus the C group at the same time point; +p < 0.05; ++p < 0.01 versus the 0.5-Hz group at the same time point; n = 5.

To test the effect of the intact actin filament system on the F/G actin ratio induced by the different frequencies, SMCs were stretched without cytochalasin D after pretreatment with it for 1 h. The Western blotting results showed that all intervention groups increased their F/G actin ratios quickly, and SMCs stretched using the cyclic strain had higher F/G actin ratios than the control SMCs. But this result was different from that of the former experiment, in which the stretched cells were not pretreated with cytochalasin D, the F/G actin ratio showed a positive correlation with frequency at 6 h, and there was almost no difference among the 0.5-, 1.25-, and 2.0-Hz groups after stretching for 12 h (Figs. 6 C and 7 B). No difference could be found between the control and the static group either (data not shown). The AIE of SMCs in each frequency group, which were stretched for 6 h after treatment with cytochalasin D, did not decrease to the level in SMCs that had been stretched without cytochalasin D treatment, and almost no difference among frequencies could be found after treatment (Fig. 5 B). This result indicated that destroying the intact actin filament system could inhibit the effect of frequency on cyclic strain-induced filament polymerization and SMC alignment.

Blocking of integrin-β1 inhibits p38 MAPK phosphorylation, F/G-actin ratio, and AIE

After SMCs had been blocked with specific integrin-β1-blocking antibody and then stretched for 1 h, the Western blotting analysis showed that, though still higher than C group, phosoho-p38 MAPK decreased in each group, significantly contrasting with SMCs stretched under the same frequencies without antibody treatment (Fig. 8 A). After stretching for 12 h, the F/G-actin ratio in each group was also found to be lower than that without blocking antibody (Fig. 8 B). And the AIE of SMCs that were stretched under frequency 1.25 Hz for 12 h was found to be higher than that without blocking antibody (Fig. 5 A). These results indicated that blocking of integrin-β1 could inhibit the activation of p38 MAPK, filament polymerization, and SMC alignment.

Cytochalasin D inhibited cyclic strain-induced SMC alignment

To examine the effects of inhibiting F-actin reorganization on the alignment of SMCs under cyclic strain, 100 nM cytochalasin D was used to pretreat SMC monolayers for 1 h. The cells were then exposed to the cyclic strain under different frequencies for 12 h. As shown in Fig. 6 D, treatment with cytochalasin D effectively inhibited SMCs from aligning, whereas SMCs stretched in medium containing cytochalasin D-free DMSO still realigned.

Cytochalasin D inhibited the frequency of cyclic strain-induced integrin-β1 activation

To test whether the filament system can affect the activation of integrin-β1 in cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment, the activation state of the integrin-β1 in SMCs that have been pretreated with cytochalasin D and stretched for 1 h with cytochalasin D still in the medium was determined by flow cytometry. The results showed that integrin-β1 activation was down-regulated when the filament system was destroyed by cytochalasin D, and no significant frequency discrepancy could be found after treatment (Figs. 4 B and 9 D), which indicated that destroying filament systems could inhibit the effect of frequency on cyclic strain-induced integrin-β1 activation.

DISCUSSION

Role of cyclic strain frequency in regulating SMC alignment

At least three types of information are included within a cyclic stretch: magnitude, frequency, and duration. Many researchers have studied the effects of magnitude and exposure time of cyclic stretch on cells, including cell orientation, cytoskeleton modification, cell proliferation, and alteration in mRNA levels and protein synthesis (26–28). However, these studies did not address the effect of the frequency of cyclic stretch on the cells. Kaspar et al. (29) reported that proliferation of human-derived osteoblast-like cells increased with the increased number of applied stretch cycles until a certain maximum number of cycles was reached, and they concluded that the effect of frequency on cell proliferation was only small when the number of cyclic strains reached a constant. In our opinion, the effect of the number of stretch cycles is equivalent to the combined effect of a certain cyclic stretch frequency plus various exposure times or a certain exposure time plus various cyclic stretch frequencies. In other words, the strain frequency has not been separated as an independent influencing factor from the number of stretch cycles. In the study presented here, SMCs were stretched with the same magnitude and duration of cyclic strain, and only variation of the frequency induced the change of SMC alignment. A higher percentage of cells appeared in the angle range closest to the direction perpendicular to the radius. By contrast, the cells still aligned randomly while being statically stretched without a variation of frequency, as also occurred in the SMCs under the static condition. Based on our mathematical model, the strain frequency 1.25 Hz was found to influence SMC alignment most effectively after exposure to the cyclic strain over a short period of time (not more than 12 h). Once the maximum duration has been reached, SMC alignment will change more under lower frequency in a given frequency range. Our results clearly demonstrated that the frequency of cyclic strain is an important regulatory factor that is independent of magnitude and duration for cyclic strain-induced SMC alignment.

Mechanisms by which the cyclic strain frequency regulates the alignment of SMCs with integration of signaling molecules

The cytoskeleton is an important signal transducer in stress-induced cell responses (17,18,30). As one of the cytoskeleton elements, the filament system possesses a relatively large proportion of actin molecules in an unpolymerized globular (G-actin) form in addition to the polymerized fibrous (F-actin) form, and a balance between polymerization and depolymerization exists in these two forms of actin. The balance will be destroyed in response to a variety of environmental conditions, and a new equilibrium can be established after an accommodative process. Some cellular pseudopods, which mainly are related to filaments, came into being in the same direction as SMCs realignment (data not shown). Therefore, we suspected that actin filaments might play an important role in regulating cyclic strain-induced SMC realignment. This hypothesis was verified by use of cytochalasin D to disrupt the intact actin filaments and inhibit the transition from G-actin to F-actin. In the presence of cytochalasin D, SMC realignment disappeared, and the shape of the cell was maintained under cyclic stretch. We also noticed that the F/G actin ratio, which was used to represent the degree of filament polymerization, changed with different frequencies of cyclic strain, which was consistent with the tendency of SMC alignment under the same strain condition. A most sensitive frequency exists in the range corresponding to the change of F/G actin ratio, which also exists in AIE, indicating that different frequencies of cyclic strain change the degree of filament polymerization, and then affect SMC alignment. A more important finding was that, after cytochalasin D disrupted the intact filament system but permitted the G- and F-actin transition, the most sensitive frequency disappeared, whereas the reaction of the cyclic strain still existed except for the control. Our results indicated that the filament system should be one of the critical points in the chain of cyclic strain-induced signal transduction, and the effect of frequency on SMCs alignment depends on the integrity of the actin filament system. However, further study is still needed to elucidate the signal transduction induced by the frequency of cyclic strain, especially the link between the filament system and SMC reorientation.

Although the intracellular signaling mechanisms of mechanotransduction have not been well understood, the ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and PI3K/Akt pathways have been found implicated in stress-induced SMC responses (31–33). However, it remains unclear whether these kinases are involved in regulating SMC alignment induced by cyclic strains with various frequencies. We have indicated that with the same strain amplitude, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and PI3K/Akt all could be activated in a nonlinear frequency-dependent pattern, but only the p38 MAPK pathway was crucial in the frequency-dependent phenotypic modulation of SMCs, whereas ERK or PI3K/Akt activation were apparently not important (24). We also found that p38 MAPK inhibitor could block the alignment of SMCs under different frequencies of cyclic strain, indicating that p38 MAPK played a crucial role in the mechanotransduction of frequency-dependent SMC alignment.

The role of integrins in stress-induced cell responses has been demonstrated by many researchers (30,34–39). Here we found that different frequencies of cyclic strain with identical magnitude could clearly affect integrin-β1 activation, which was also consistent with SMC reorientation, indicating a role of mechanotransduction in cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment. Integrins can transmit mechanical signals, not only by altering biochemical properties such as the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of some complex proteins but also by reorganizing the cytoskeleton (30). This outside-in signal pathway was verified again with our results. When the outside-in signal of integrin-β1 was inhibited by a specific blocking antibody, the stretch-induced activation of p38 MAPK was clearly suppressed, and the F/G-actin ratio of filament system was also changed, both of which were proven to affect the cyclic strain-induced SMC alignment. On the other hand, the unique structural features of integrins enable them to mediate inside-out signaling through FA (22). We found that when the filament system was destroyed by cytochalasin D, the activation of integrin-β1, although not totally blocked, decreased, indicating that some signal must have been transmitted to integrin-β1 through the actin filaments. In addition, the effect of frequency on integrin-β1 activation was significantly inhibited with cytochalasin D. One potential explanation is that the integrin inside-out signaling pathway is likely to be involved in the cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment, and the signal it transferred might be the “frequency.”

The advantages of using the AIE modeling approach to describe SMC alignment

The AOA and percentage of cells within a certain angle region were used as common parameters to describe the change of cell alignment under stress (40,41). But these two parameters have their own limitations. The first is that they lost much of the important information, i.e., the percentage of cells in other angle regions. Lee et al. (17) reported a better way to describe changes in cell alignment by calculating angle deviation, which might be useful in many fields. However, this method has limited use in this case because it should be calculated on a computer workstation. Furthermore, in the study presented here, some cells subjected to cyclic strain still did not align like the others. In other words, not all cells respond to cyclic strain in the same way, and the degree of alignment is related to the frequency of cyclic strain. Therefore, cells should not be regarded as a unity but as a combined system. More important is that almost no current device, including the one in our experiment, can be used to provide a pure uniaxial stretch (23). This limitation of the apparatus makes it difficult to define the orientation angle between the cell and stretch direction. We first applied Shannon's information entropy (AIE) to appraise the degree of cell disarray, which included information on the orientation of all cells within a cell system. It evaluated the regularity of cell alignment but omitted the numerical value of the angle and thereby simplified the calculation. In addition, when cells were stretched for more than 24 h, the difference in AOA among frequency groups was less than 4%, but the difference in AIE was more than 10%, indicating that AIE is a better parameter to distinguish two groups with respect to cell alignment. From the data on AIE, we were able to describe the cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment successfully, which indicates that AIE is an effective parameter to describe cell alignment.

It is very important for a functional tissue-engineered blood vessel to have natural morphology and structure. How to control SMC orientation in the media of a tissue-engineered vessel remains a difficult problem (42–45). In the current study, we observed the time course of cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment. The mathematical models fitting the AIE were successfully demonstrated, suggesting that the frequency of cyclic strain is very important in regard to the regularity of SMC alignment. Although our results may not apply to other cells or mechanical conditions, our present work provides new biomechanical insights into the control mechanisms of SMC alignment and vascular tissue engineering.

In summary, the frequency of cyclic strain is an important factor in regulating SMC alignment. Within a certain time period, an optimal frequency, ∼1.25 Hz, has been shown to most effectively influence SMC alignment. After sufficient exposure time, more regular alignment of SMCs could be obtained under a lower frequency of cyclic strain within a certain frequency range. Integrin-β1, p38 MAPK, and the actin filament system were involved in cyclic strain frequency-dependent SMC alignment. As an important signal acceptor, integrin-β1 was activated when it sensed the strain signal from extracellular ligands, transmitted the signal to the p38 MAPK protein, one of the key elements of the intercellular signal network, and activated p38 MAPK through increasing phosphorylation. Actin filament polymerization might be promoted by p38 MAPK through some signal cascades, followed by SMC realignment. Besides, the intact filament system might be the foundation to accept the signal of cyclic strain frequency and transmit it to integrin through the inside-out signaling pathway, thereby influencing integrin activation, p38 MAPK phosphorylation, filament polymerization, and SMC alignment successively. However, the work presented here only described a frame of signal transduction about the cyclic strain-frequency-dependent SMC alignment, and the exact signaling mechanisms remain to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

In particular, we thank Professor Shuqian Liu at Department of Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, for his various discussions and helpful suggestions.

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30570459, No. 10732070, and No. 10132020.

Editor: Elliot L. Elson.

References

- 1.Tranquillo, R. T., T. S. Girton, B. A. Bromberek, T. G. Triebes, and D. L. Mooradian. 1996. Magnetically orientated tissue-equivalent tubes: application to a circumferentially orientated media-equivalent. Biomaterials. 17:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finlay, H. M., P. Whittaker, and P. B. Canham. 1998. Collagen organization in the branching region of human brain arteries. Stroke. 29:1595–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.L'Heureux, N., L. Germain, R. Labbe, and F. A. Auger. 1993. In vitro construction of a human blood vessel from cultured vascular cells: a morphologic study. J. Vasc. Surg. 17:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standley, P. R., A. Cammarata, B. P. Nolan, C. T. Purgason, and M. A. Stanley. 2002. Cyclic stretch induces vascular smooth muscle cell alignment via NO signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283:H1907–H1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanda, K., and T. Matsuda. 1993. Behavior of arterial wall cells cultured on periodically stretched substrates. Cell Transplant. 2:475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson, E., F. Vives, T. Collins, and H. E. Ives. 1998. Strain-responsive elements in the PDGF-A gene promoter. Hypertension. 31:170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taber, L. A. 1998. A model for aortic growth based on fluid shear and fiber stresses. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 120:348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu, J. J., D. L. Wang, S. Chien, R. Skalak, and S. Usami. 1998. Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 120:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda, K., T. Matsuda, and T. Oka. 1992. Two-dimensional orientational response of smooth muscle cells to cyclic stretching. ASAIO J. 38:M382–M385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao, S., A. Suciu, T. Ziegler, J. E. Moore, E. Burki, J. J. Meister, and H. R. Brunner. 1995. Synergistic effects of fluid shear stress and cyclical circumferential stretch on vascular endothelial cell morphology and cytoskeleton. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15:1781–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dartsch, P. C., H. Hammerle, and E. Betz. 1986. Orientation of cultured arterial smooth muscle cells growing on cyclically stretched substrates. Acta Anat. (Basel). 125:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, H., W. Ip, R. Boissy, and E. S. Grood. 1995. Cell orientation response to cyclically deformed substrates: experimental validation of a cell model. J. Biomech. 28:1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, J. H., P. Goldschmidt-Clermont, N. Moldovan, and F. C. Yin. 2000. Leukotrienes and tyrosine phosphorylation mediate stretching-induced actin cytoskeletal remodeling in endothelial cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 46:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, J. H., P. Goldschmidt-Clermont, J. Wille, and F. C. Yin. 2001. Specificity of endothelial cell reorientation in response to cyclic mechanical stretching. J. Biomech. 34:1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, W., Q. H. Chen, I. Mills, and B. E. Sumpio. 2003. Involvement of S6 Kinase and p38 pathways in strain-induced alignment and proliferation of bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 195:202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills, I., C. R. Cohen, K. Kamal, G. Li, T. Shin, W. Du, and B. E. Sumpio. 1997. Strain activation of bovine aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation and alignment: study of strain dependency and the role of protein kinase A and C signaling pathways. J. Cell. Physiol. 170:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, A. A., D. A. Graham, S. Dela. Cruz, A. Ratcliffe, and W. J. Karlon. 2002. Fluid shear stress-induced alignment of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 124:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neidlinger-Wilke, C., E. S. Grood, J. H.-C. Wang, R. A. Brand, and L. Claes. 2001. Cell alignment is induced by cyclic changes in cell length: studies of cells grown in cyclically stretched substrates. J. Orthop. Res. 19:286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, N., J. P. Butler, and D. E. Ingber. 1993. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 5111:1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sastry, S. K., and A. F. Horwitz. 1993. Integrin cytoplasmic domains: mediators of cytoskeletal linkages and extra- and intracellular initiated transmembrane signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5:819–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz, M. A., M. D. Schaller, and M. H. Ginsberg. 1995. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:549–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, S., J. L. Guan, and S. Chien. 2005. Biochemistry and biomechanics of cell motility. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 7:105–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vande Geest, J. P., E. S. Di Martino, and D. A. Vorp. 2004. An analysis of the complete strain field within FlexercellTM membranes. J. Biomech. 37:1923–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu, M. J., B. Liu, H. Q. Wang, Z. Q. Yan, B. R. Shen, and Z. L. Jiang. 2007. Frequency-dependent phenotype modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells under cyclic mechanical strain. J. Vasc. Res. 44:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon, C. E. A. 1948. Mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27:379–423, 623–656. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrow, D., C. Sweeney, Y. A. Birney, P. M. Cummins, D. Walls, E. M. Redmond, and P. A. Cahill. 2005. Cyclic strain inhibits notch receptor signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Circ. Res. 96:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiger, R. C., W. Taylor, M. R. Glucksberg, and D. A. Dean. 2006. Cyclic stretch-induced reorganization of the cytoskeleton and its role in enhanced gene transfer. Gene Ther. 13:725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joung, I. S., M. N. Iwamoto, Y. T. Shiu, and C. T. Quam. 2006. Cyclic strain modulates tubulogenesis of endothelial cells in a 3D tissue culture model. Microvasc. Res. 71:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaspar, D., W. Seidl, C. Neidlinger-Wilke, A. Beck, L. Claes, and A. Ignatius. 2002. Proliferation of human-derived osteoblast-like cells depends on the cycle number and frequency of uniaxial strain. J. Biomech. 35:873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komuro, I. 2000. Molecular mechanism of mechanical stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Jpn. Heart J. 41:117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tock, J., V. Van Putten, K. R. Stenmark, and R. A. Nemenoff. 2003. Induction of SM-alpha-actin expression by mechanical strain in adult vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated through activation of JNK and p38 MAP kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:1116–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owens, G. K. 1995. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol. Rev. 75:487–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown, D. J., E. M. Rzucidlo, B. L. Merenick, R. J. Wagner, K. A. Martin, and R. J. Powell. 2005. Endothelial cell activation of the smooth muscle cell phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes differentiation. J. Vasc. Surg. 41:509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzima, E., M. A. del Pozo, S. J. Shattil, S. Chien, and M. A. Schwartz. 2001. Activation of integrins in endothelial cells by fluid shear stress mediates Rho-dependent cytoskeletal alignment. EMBO J. 20:4639–4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller, J. M., W. M. Chilian, and M. J. Davis. 1997. Integrin signaling transduces shear stress-dependent vasodilation of coronary arterioles. Circ. Res. 80:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jalali, S., M. A. del Pozo, K. Chen, H. Miao, Y. Li, M. A. Schwartz, J. Y. Shyy, and S. Chien. 2001. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction requires its dynamic interaction with specific extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1042–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki, M., K. Naruse, Y. Asano, T. Okamoto, N. Nishikimi, T. Sakurai, Y. Nimura, and M. Sokabe. 1997. Up-regulation of integrin beta 3 expression by cyclic stretch in human umbilical endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 239:372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson, E., K. Sudhir, and H. E. Ives. 1995. Mechanical strain of rat vascular smooth muscle cells is sensed by specific extracellular matrix/integrin interactions. J. Clin. Invest. 96:2364–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudhir, K., E. Wilson, K. Chatterjee, and H. E. Ives. 1993. Mechanical strain and collagen potentiate mitogenic activity of angiotensin II in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Invest. 92:3003–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, J. H., P. Goldschmidt-Clermont, and F. C. Yin. 2000. Contractility affects stress fiber remodeling and reorientation of endothelial cells subjected to cyclic mechanical stretching. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 28:1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kada, K., K. Yasui, K. Naruse, K. Kamiya, I. Kodama, and J. Toyama. 1999. Orientation change of cardiocytes induced by cyclic stretch stimulation: time dependency and involvement of protein kinases. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 31:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seliktar, D., R. A. Black, R. P. Vito, and R. M. Nerem. 2000. Dynamic mechanical conditioning of collagen-gel blood vessel constructs induces remodeling in vitro. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 28:351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seliktar, D., R. M. Nerem, and Z. S. Galis. 2001. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the remodeling of cell-seeded vascular constructs subjected to cyclic strain. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29:923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanda, K., T. Matsuda, and T. Oka. 1993. Mechanical stress induced cellular orientation and phenotypic modulation of 3-D cultured smooth muscle cells. ASAIO J. 39:M686–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, J. H., G. Yang, and Z. Li. 2005. Controlling cell responses to cyclic mechanical stretching. Ann. Biomed. Eng. (N.Y.). 33:337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]