Abstract

We examined the relationship between deactivation and inactivation in Kv4.2 channels. In particular, we were interested in the role of a Kv4.2 N-terminal domain and accessory subunits in controlling macroscopic gating kinetics and asked if the effects of N-terminal deletion and accessory subunit coexpression conform to a kinetic coupling of deactivation and inactivation. We expressed Kv4.2 wild-type channels and N-terminal deletion mutants in the absence and presence of Kv channel interacting proteins (KChIPs) and dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like proteins (DPPs) in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents at positive and deactivation tail currents at negative membrane potentials were recorded under whole-cell voltage-clamp and analyzed by multi-exponential fitting. The observed changes in Kv4.2 macroscopic inactivation kinetics caused by N-terminal deletion, accessory subunit coexpression, or a combination of the two maneuvers were compared with respective changes in deactivation kinetics. Extensive correlation analyses indicated that modulatory effects on deactivation closely parallel respective effects on inactivation, including both onset and recovery kinetics. Searching for the structural determinants, which control deactivation and inactivation, we found that in a Kv4.2Δ2–10 N-terminal deletion mutant both the initial rapid phase of macroscopic inactivation and tail current deactivation were slowed. On the other hand, the intermediate and slow phase of A-type current decay, recovery from inactivation, and tail current decay kinetics were accelerated in Kv4.2Δ2–10 by KChIP2 and DPPX. Thus, a Kv4.2 N-terminal domain, which may control both inactivation and deactivation, is not necessary for active modulation of current kinetics by accessory subunits. Our results further suggest distinct mechanisms for Kv4.2 gating modulation by KChIPs and DPPs.

INTRODUCTION

Voltage-gated K+ channels related to the Shal gene of Drosophila (Kv4) mediate rapidly inactivating A-type currents (1,2). They underlie a component of transient outward current with fast recovery kinetics (ITO,f) in ventricular myocytes (3) and a subthreshold activating somatodendritic A-type current (ISA) in many neuronal cell types (4). Kv4 channels are absent from axonal membranes where A-type currents are mediated by Shaker-related Kv1 channels (5,6).

The inactivation mechanism of Kv4 channels differs in many aspects from the well-studied N- and C-type inactivation mechanisms found in Shaker-related Kv1 channels: N-terminal truncation, which completely abolishes the prominent Shaker N-type inactivation (7), only leads to a moderate slowing of Kv4 channel macroscopic inactivation (8–10). Moreover, high external K+ or external tetraethylammonium, both preventing Shaker C-type inactivation (11,12), leave Kv4 channel macroscopic inactivation kinetics largely unaffected (8,9,13). For Shaker and its close relative Kv1.4, very little inactivation occurs from closed states. Rather, channel opening is a prerequisite for Shaker channel inactivation. During long-lasting strong depolarizations, a large fraction of Shaker channels accumulates in open inactivated states, as reflected by their passage through the open state after repolarization (14,15). Consequently, the reopening tail current kinetics of Shaker channels observed in high external K+ mirror the kinetics of recovery from inactivation (14). Unlike Shaker, Kv4 channels show preferential closed-state inactivation at all physiologically relevant membrane potentials (8,16). Thus, moderate depolarizations may cause direct transitions from preopen-closed to closed-inactivated states (see state diagram in Fig. 11 A). After complete inactivation of Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents induced by long-lasting strong depolarizations, no reopening tail currents were observed in high external K+, indicative of absorbing closed-state inactivation also at positive potentials (8). It has been suggested that weakly forward-biased or even reverse-biased opening kinetics (i.e., kco ≤ koc; see also Fig. 11 A) of Kv4 channels may underlie closed-state inactivation at positive potentials. In support of such a model, it has been shown experimentally that changes in Kv4 channel deactivation kinetics parallel changes in macroscopic inactivation kinetics after experimental manipulation of channel closure. For instance, mutating a cysteine in the S4-S5 linker or two valines in the S6 segment causes a slowing of Kv4 channel deactivation and at the same time a slowing of macroscopic A-type current inactivation (16,17). Also, using the slower permeating ion Rb+ instead of K+ as charge carrier leads to a slowing of both tail current deactivation at negative and A-type current inactivation at positive potentials (8,13,16). These findings strongly suggest that the closing step plays a key role in Kv4 channel inactivation at positive potentials.

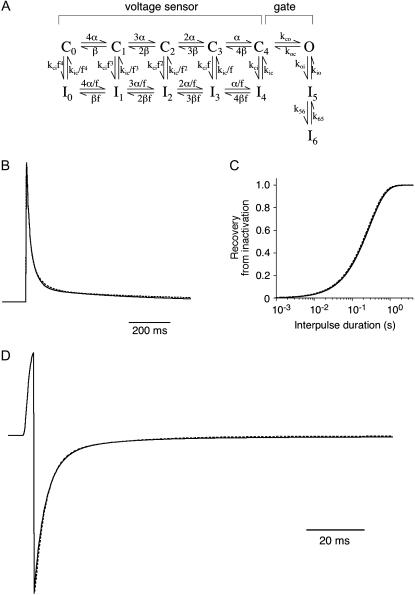

FIGURE 11.

Simulation of Kv4.2 channel gating with an allosteric model. (A) State diagram illustrating the transitions between closed (C), open (O), and inactivated (I) states, which define an allosteric model of Kv4.2 channel gating. (B–D) Experimentally determined key features of Kv4.2 macroscopic gating kinetics, including A-type current decay at +40 mV (B), recovery from inactivation at −80 mV (C), and tail current decay at −80 mV after activation at +40 mV (D) were reproduced by computer simulations using the wild-type rates in Table 3 (tail current simulation accounts for a fixed Rb+-factor of 0.37). Dotted lines, theoretical current and data templates representing mean values of macroscopic activation, inactivation, and deactivation parameters (see Materials and Methods).

Kv4 channel α-subunits coassemble with accessory Kv channel interacting proteins (KChIPs; 18) and dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-related proteins (DPPs; 19). Both types of accessory subunit modulate Kv4 channel macroscopic inactivation kinetics in a characteristic manner: KChIPs slow down the initial rapid inactivation phase but accelerate the slow inactivation phase of Kv4 channel-mediated A-type currents. At the same time, KChIPs speed up recovery from inactivation (18,20,21). DPPs accelerate both Kv4 channel-mediated A-type current decay and recovery from inactivation (19). Notably, both KChIPs (21) and DPPs (22) have been reported to accelerate Kv4 channel macroscopic deactivation kinetics. Very little is known so far about the nature of the Kv4/DPP interaction; however, the structural determinants of Kv4/KChIP interaction have been studied in great detail (23–27). One central aspect of KChIP-mediated gating modulation seems to be physical binding and immobilization of the Kv4 proximal N-terminus; and as a consequence, suppression of N-type inactivation features in Kv4 channels (17,26). In accordance with this idea, the effects of KChIP binding on the initial rapid phase of macroscopic Kv4 channel inactivation resemble the effects caused by N-terminal deletion. On the other hand, the effects of KChIP binding and N-terminal deletion, respectively, on Kv4 channel deactivation kinetics seem to diverge: Although KChIPs accelerate Kv4 channel tail current deactivation (21), there is experimental evidence that N-terminal truncation of Kv4.2 slows deactivation (8,17,28). The latter findings suggest that a Kv4.2 N-terminal domain plays a role in controlling both inactivation and deactivation. Physical binding of KChIPs may induce conformational changes of the Kv4 N-terminus that shift its functional role in favor of controlling deactivation. However, the mechanisms underlying the N-terminal modulation of deactivation and the acceleration of deactivation mediated by accessory KChIPs and DPPs have not been investigated.

Here we examined the role of a Kv4.2 N-terminal domain and accessory subunits in controlling macroscopic inactivation and deactivation. Our results demonstrate that modulatory effects on deactivation closely match respective effects on certain aspects of macroscopic inactivation, including both onset and recovery kinetics. Furthermore, they bear important mechanistic implications concerning Kv4.2 channel gating and its modulation by KChIPs and DPPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Heterologous channel expression

We used Kv4.2 cloned from a human cortex cDNA library (10). N-terminal deletion mutants of Kv4.2 (20) lacked 9 (Δ2–10), 19 (Δ2–20), or all 39 amino acids preceding the T1-domain (Δ2–40). We refer to the initial 40 amino acid portion of the Kv4.2 α-subunit as the proximal N-terminus. Kv4.2 channels were studied in the absence and presence of accessory subunits. For this purpose, we coexpressed the human KChIP2.1 splice variant (23) and the short splice variant of human DPPX (gift from Dr. Keiji Wada). All constructs were subcloned in a pcDNA3 eukaryotic expression vector and transiently expressed by lipofectamine transfection (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells as previously described (20). For each 35 mm culture dish we used either 1 μg Kv4.2 wild-type cDNA or 0.1 μg cDNA, coding for N-terminal deletion constructs. For accessory subunit coexpression, we used 0.1 μg Kv4.2 in combination with 1 μg KChIP2 cDNA (1:10) or 0.05 μg Kv4.2 in combination with 1 μg DPPX cDNA (1:20). For ternary complex expression, we reduced the amount of Kv4.2 cDNA to 0.025 μg (1:40:40). In all experiments 0.5 μg enhanced green fluorescent protein cDNA (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany) was coexpressed as a reporter plasmid. Fluorescent cells were selected for electrophysiological recordings 12 h after transfection. The Kv4.2 channel-mediated current kinetics and all modulatory effects of accessory subunit overexpression on Kv4.2 channel gating, previously described for other expression systems (19,21), could be reproduced in our experiments (see below).

Recording techniques

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C) on small cells (capacitance not exceeding 20 pF). For the recording of Kv4.2-mediated outward currents, cells were continuously superfused with a solution containing (in mM): NaCl 135, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, HEPES 5, and sucrose 10; pH 7.4 (NaOH). Recording pipettes, pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass had bath resistances between 2 and 2.5 MΩ when filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): KCl 125, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, EGTA 11, HEPES 10, K2ATP 2, and glutathione 2; pH 7.2 (KOH). Tail currents were recorded in nearly symmetrical Rb+. In these experiments cells were bathed with a solution containing (in mM): RbCl 135, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, HEPES 5, and sucrose 10; pH 7.4 (RbOH), and pipettes were filled with internal solution containing (in mM): RbCl 125, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, EGTA 11, HEPES 10, Na2ATP 2, and glutathione 2; pH 7.2 (RbOH). Under these ionic conditions, the reversal potential lay outside the voltage range of interest. Moreover, a general slowing of tail current decay due to the different permeant ion species (29) allowed adequate voltage-clamp under certain extreme conditions; e.g., in the presence of accessory subunits, where expression levels tended to be high and deactivation kinetics fast (see below). In some tail current measurements taken from Kv4.2 wild-type channels in the absence of accessory subunits, internal and external Rb+ was replaced by K+. All recordings were performed with an EPC9 patch-clamp amplifier combined with PULSE software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Series resistance compensation was maximal (usually between 85% and 95%). Kv4.2 channels were activated by voltage jumps from −100 mV to more depolarized potentials (e.g., +40 mV), and macroscopic inactivation was monitored for 2.5 s. Recovery from inactivation was studied using a double-pulse protocol (1500 and 25 ms, respectively, to +40 mV) with variable interpulse intervals at different potentials between −120 and −80 mV. Tail currents were recorded at potentials between −100 and −50 mV after brief (3–5 ms) activation at more depolarized potentials (e.g., +40 mV, but see insets in Fig. S3 of the Supplementary Material). The examination of all voltage-dependent processes occurred in 10 mV increments. Signals were filtered at 6.25 kHz with low-pass Bessel characteristics, amplified as required, and digitized at 350 μs (A-type currents) or 40 μs (tail currents) sample intervals. Capacitive current transients were compensated online, and a P/5 routine was used for leak subtraction.

Data analysis

The program PULSEFIT (HEKA) was used to analyze the acquired current traces. Inactivation kinetics of Kv4.2-mediated outward currents was fitted with the sum of three tail current deactivaton kinetics with the sum of two exponentials. Relative amplitudes of individual time constants were derived from extrapolated fitting curves starting at the time point of the voltage step. The obtained data were further processed using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Recovery of Kv4.2 channels from inactivation, deduced from fractional current amplitudes plotted against the interpulse interval, was described by a single-exponential function. Assuming that the time constants of deactivation and recovery from inactivation depended exponentially on voltage, respective data were fitted with the following equation: τ deact/rec(V) = τ deact/rec(0) exp(qapp V/25.28 mV), where τ deact/rec(V) is the deactivation/recovery time constant at a given membrane potential V and τ deact/rec(0) is a theoretical deactivation/recovery time constant at 0 mV. The voltage dependence of deactivation and recovery from inactivation is described by the apparent charge qapp, a fraction of the elementary charge qe, dependent on the Boltzmann constant kB and the absolute temperature T (kB T/qe = RT/F = 25.28 mV at room temperature; 30). Peak conductance-voltage (G-V) relationships were fitted with a Boltzmann function of the form G/Gmax = 1/{1 + exp[(V − V′)/k]}4, where the fraction of the maximal conductance G/Gmax at a given membrane potential V depends on V′ and the slope factor k. Instead of V′, the voltage for half-maximal activation of individual subunits, we give V1/2 values (see legend to Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material), which were determined manually and represent the potential where the above Boltzmann function has a value of 0.5. Pooled data are presented as mean ± SE, and Pearson's correlation analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Modeling and simulations

To simulate Kv4.2-mediated currents, a previously published fully allosteric model (8; see Fig. 11 A) was refined by adjusting rates and their voltage dependences (see Table 3) to reproduce data acquired in this study. The Markov model parameters and rates were implemented in a simulation routine operating under PULSESIM software (HEKA). Rate adjustment was done based on theoretical current traces, reflecting previously analyzed activation kinetics (8) combined with the mean inactivation and deactivation parameters from Tables 1 and 2 (see Fig. 11 and Table 3). The effect of Rb+ on tail current deactivation was modeled by a 2.7-fold reduction of the closing rate koc. This fixed “Rb+-factor” of 0.37 was maintained for each of five different modeled constellations, including Kv4.2 wild-type, Kv4.2Δ2–10, Kv4.2/KChIP2, Kv4.2/DPPX, and ternary Kv4.2/KChIP2/DPPX channels (see Fig. 12 and Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kv4.2 gating model parameters

| wt | Δ2–10 | wt + KChIP2 | wt + DPPX | wt + KChIP2 + DPPX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α0 (s−1) | 175 | 175 | 175 | 416 | 416 |

| zα | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| β0 (s−1) | 3.598 | 3.598 | 19.47 | 9 | 48.6 |

| zβ | 1.742 | 1.742 | 1.742 | 1.556 | 1.556 |

| kco(0) (s−1) | 347 | 320 | 347 | 347 | 347 |

| zco | 0.185 | 0.185 | 0.185 | 0 | 0 |

| koc(0) (s−1) | 1267/469* | 559/207 | 1670/618 | 1267/469 | 1670/618 |

| zoc | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0 | 0 |

| kci (s−1) | 23.92 | 23.92 | 30.61 | 38.07 | 48.73 |

| kic (s−1) | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.537 |

| f† | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| koi (s−1) | 194 | 141 | 43.08 | 300 | 66.9 |

| kio (s−1) | 36.86 | 174 | 109.9 | 14.24 | 42.46 |

| k56 (s−1) | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 |

| k65 (s−1) | 11.52 | 11.52 | 11.52 | 11.52 | 11.52 |

Rate constants defining transitions between closed states (α and β) and rate constants defining the opening/closing step (kco and koc) are assumed to depend exponentially on voltage according to the following equations: α(V) = α(0) exp [zα V/(RT/F)]; β(V) = β(0) exp [zβ V/(RT/F)]; kco(V) = kco(0) exp [zco V/(RT/F)]; koc(V) = koc(0) exp [zoc V/(RT/F)].

The effect of switching from standard recording solutions with external Na+ and internal K+ to symmetrical Rb+ (see Materials and Methods) was modeled by applying a fixed Rb+-factor of 0.37 to koc.

The allosteric factor f defines the voltage-dependent coupling between activation and inactivation pathways for closed channels.

TABLE 1.

Kv4.2 inactivation

| Kv4.2 | τ1 inact (ms) | % τ1 inact | τ2 inact (ms) | % τ2 inact | τ3 inact (ms) | % τ3 inact | τ rec (ms) | qapp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | 14 ± 1 (n = 8) | 68 ± 3 | 54 ± 4 | 25 ± 3 | 682 ± 97 | 7 ± 3 | 290 ± 43 (n = 3) | 1.06 |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 264 ± 21 (n = 4) | |||||||

| wt + KChIP2 | 22 ± 3 (n = 4) | 31 ± 7 | 53 ± 7 | 67 ± 7 | 452 ± 67 | 2 ± 1 | 39 ± 3 (n = 4) | |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 36 ± 1 (n = 3) | |||||||

| wt + DPPX | 7 ± 1 (n = 4) | 75 ± 4 | 28 ± 2 | 21 ± 4 | 933 ± 35 | 4 ± 1 | 91 ± 8 (n = 4) | |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 96 ± 8 (n = 5) | |||||||

| wt + KChIP2 + DPPX | 21 ± 3 (n = 10) | 63 ± 10 | 54 ± 7 | 34 ± 10 | 369 ± 70 | 3 ± 1 | 19 ± 10 (n = 10) | |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 26 ± 6 (n = 8) | |||||||

| Δ2–10 | 26 ± 2 (n = 5) | 64 ± 4 | 107 ± 13 | 26 ± 4 | 824 ± 102 | 10 ± 1 | 216 ± 35 (n = 3) | 1.05 |

| Δ2–10 + KChIP2 | 22 ± 2 (n = 8) | 55 ± 8 | 74 ± 7 | 36 ± 7 | 431 ± 27 | 9 ± 1 | 56 ± 14 (n = 3) | 0.93 |

| Δ2–10 + DPPX | 14 ± 1 (n = 9) | 56 ± 4 | 54 ± 4 | 25 ± 2 | 474 ± 31 | 19 ± 2 | 82 ± 6 (n = 8) | 0.88 |

| Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX | 18 ± 3 (n = 8) | 47 ± 10 | 41 ± 7 | 52 ± 10 | 398 ± 83 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 2 (n = 6) | 0.63 |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 30 ± 6 (n = 8) | |||||||

| Δ2–20 | 42 ± 3 (n = 10) | 40 ± 3 | 126 ± 8 | 52 ± 2 | 670 ± 81 | 8 ± 1 | 253 ± 16 (n = 3) | |

| Δ2–40 | 39 ± 4 (n = 3) | 33 ± 6 | 108 ± 5 | 60 ± 5 | 385 ± 24 | 7 ± 1 | 238 ± 47 (n = 3) | |

| Δ2–40 + DPPX | 12 ± 2 (n = 9) | 23 ± 3 | 87 ± 6 | 66 ± 4 | 237 ± 55 | 11 ± 2 | 72 ± 9 (n = 9) | |

| in Rb+/Rb+: | 88 ± 4 (n = 11) |

Inactivation time constants and relative amplitudes (sum of three exponentials) at +40 mV and recovery time constants (single-exponential function) at −80 mV. For some channels, the apparent charge qapp related to the recovery from inactivation (see Materials and Methods) was determined. As indicated, in some experiments recovery was measured in symmetrical Rb+.

TABLE 2.

Kv4.2 deactivation

| Kv4.2 | τ1 deact (ms) | qapp | % τ1 deact | τ2 deact (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | 3.9 ± 0.18 (n = 7) | 0.50 | 87 ± 1 | 22.5 ± 1.3 |

| in K+/K+: | 1.5 ± 0.3 (n = 4) | 0.57 | 83 ± 8 | 15.4 ± 7.8 |

| wt + KChIP2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 (n = 5) | 0.93 | 89 ± 1 | 8.7 ± 3.3 |

| wt + DPPX | 3.0 ± 0.2 (n = 5) | 0.82 | 96 ± 1 | 55.1 ± 13.7 |

| wt + KChIP2 + DPPX | 1.1 ± 0.1 (n = 6) | 1.09 | 97 ± 1 | 5.4 ± 0.7 |

| Δ2–10 | 6.8 ± 0.4 (n = 8) | 0.62 | 69 ± 3 | 31.4 ± 1.8 |

| Δ2–10 + KChIP2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 (n = 7) | 1.02 | 96 ± 1 | 11.3 ± 2.5 |

| Δ2–10 + DPPX | 3.9 ± 0.4 (n = 8) | 0.79 | 93 ± 2 | 15.1 ± 1.5 |

| Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX | 1.3 ± 0.1 (n = 8) | 1.17 | 94 ± 2 | 4.5 ± 1.1 |

| Δ2–20 | 7.5 ± 0.4 (n = 5) | 0.51 | 74 ± 3 | 20.2 ± 1.3 |

| Δ2–40 | 9.6 ± 1.4 (n = 9) | 0.46 | 78 ± 3 | 35.6 ± 5.4 |

| Δ2–40 + DPPX | 3.7 ± 0.2 (n = 11) | 0.78 | 96 ± 1 | 40.1 ± 4.6 |

Tail current deactivation time constants from double-exponential fits including apparent charges qapp (see Materials and Methods) and relative amplitudes for the first time constant obtained in symmetrical Rb+ at −80 mV. As indicated, experiments with wild-type in the absence of accessory subunits were also conducted in symmetrical K+.

FIGURE 12.

Simulating effects of Kv4.2 channel gating modulation. By appropriate adjustment of rates based on the experimental results of this study (see Table 3), the effects of a nine amino acid N-terminal deletion (green), KChIP2 coexpression (dark gray), DPPX coexpression (light gray), and the coexpression of both KChIP2 and DPPX (magenta) on Kv4.2 channel gating were reproduced by computer simulations. (A) Effects on A-type current inactivation at +40 mV; (B) Effects on recovery from inactivation at −80 mV; (C) Effects on tail current decay kinetics at −80 mV taking into account a fixed Rb+-factor of 0.37 (see Table 3).

RESULTS

Modulation of Kv4.2 macroscopic inactivation by N-terminal deletion and KChIP2 coexpression

Kv4.2 channel constructs were expressed in HEK 293 cells in the absence and presence of accessory subunits and functionally characterized in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments. Depolarization-evoked currents mediated by Kv4.2 wild-type showed triple-exponential decay kinetics (8); and a typical crossover of normalized current traces was observed in the presence of KChIP2 (Fig. 1 A). This crossover was due to an increase in the first and a decrease in the third time constant of inactivation accompanied by a change in the relative amplitudes of all three-time constants (Fig. 1 C). At +40 mV, peak current activation was ≥90% (Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material), and the time constants of inactivation and their relative amplitudes did not show much change at more positive membrane potentials (Fig. S2 of the Supplementary Material). Therefore we focused our kinetic analyses of macroscopic inactivation on the data obtained at +40 mV. The recovery of Kv4.2 channels from inactivation was accelerated by KChIP2 (Fig. 1 D). The results obtained by fitting exponential functions to Kv4.2 inactivation and recovery kinetics are also shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of N-terminal truncation and KChIP2 coexpression on macroscopic Kv4.2 inactivation. (A) Normalized representative A-type currents mediated by Kv4.2 wild-type (wt) in the absence and presence of KChIP2 (black traces) and by the N-terminal deletion mutants Kv4.2Δ2–20 (Δ2–20; blue trace) and Kv4.2Δ2–40 (Δ2–40; red trace) in the absence of KChIP2. Note the typical crossover of wild-type current traces in the absence and presence of KChIP2. (B) Currents mediated by Kv4.2Δ2–10 (Δ2–10) in the absence and presence of KChIP2 (green traces) in comparison to wild-type (traces from A indicated as dotted lines). Voltage protocols for current activation are shown below the traces. Only half of the length of a 2.5 s test pulse to +40 mV is shown, and horizontal dotted lines represent zero current. (C) Results obtained by fitting the sum of three exponentials to the A-type current decay. Time constants of inactivation are represented by horizontal bars, and respective relative amplitudes of the total decay (in %) are indicated. Vertical dotted lines represent mean values for wild-type time constants in the absence of KChIP2. (D) Recovery from inactivation was studied at −80 mV. Relative peak amplitudes, obtained with different interpulse durations, are shown for wild-type (black) and Kv4.2Δ2–10 (green) in the absence (solid symbols) and presence (open symbols) of KChIP2. Fitting curves represent single-exponential functions, broken lines without symbols respective curves for Kv4.2Δ2–20 (blue) and Kv4.2Δ2–40 (red) in the absence of KChIP2. Note logarithmic x-scaling in C and D.

Similar to KChIP2 coexpression, N-terminal deletion of 39 (Δ2–40), 19 (Δ2–20), or 9 amino acids (Δ2–10) of the Kv4.2 α-subunit caused a slowing of the initial A-type current decay (Fig. 1, A and B) due to the prevention of N-type inactivation-related mechanisms (17). Notably, deleting 19 or 39 N-terminal amino acids caused similar effects on inactivation decay, and these effects were more pronounced than the effect of deleting only 9 amino acids (Fig. 1, A–C; Table 1). In contrast to Kv4.2Δ2–40 and Kv4.2Δ2–20 (KChIP2 coexpression data not shown), Kv4.2Δ2–10 channels were still able to functionally interact with KChIP2. This allowed us to study the KChIP2-mediated gating modulation in the absence of a significant contribution of N-type inactivation. Similar to wild-type the Kv4.2Δ2–10 mutant showed an acceleration of both the slow phase of A-type current inactivation and recovery from inactivation in the presence of KChIP2 (Fig. 1, B–D; Table 1). These data suggested that the KChIP2-induced slowing of the initial A-type current decay due to a suppression of N-type inactivation features (17), on the one hand, and the combined KChIP2-induced acceleration of the slow phase of A-type current decay and recovery from inactivation, on the other hand, depend on distinct mechanisms.

Effects of N-terminal deletion and KChIP2 coexpression on Kv4.2 deactivation

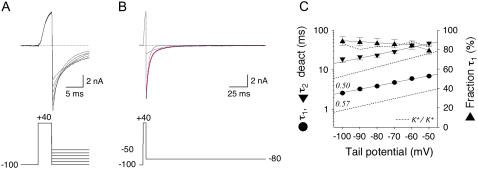

To compare the changes in inactivation kinetics caused by N-terminal deletion and KChIP2 coexpression with respective changes in deactivation kinetics, we studied Kv4.2 channel-mediated tail currents at different negative potentials between −100 and −50 mV (Fig. 2 A). Most of these experiments were done in symmetrical Rb+. The decay kinetics of tail currents mediated by Kv4.2 wild-type channels were adequately described by the sum of two exponentials (Fig. 2 B). At −80 mV the fast time constant of deactivation (∼4 ms) accounted for ∼90% of the total decay (Fig. 2, B and C). The results obtained by fitting exponential functions to Kv4.2 channel deactivation kinetics are also shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

Kinetic analysis of Kv4.2 channel-mediated tail current deactivation. Deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type channels studied in symmetrical Rb+. (A) Tail currents elicited at membrane potentials between −100 and −50 mV after brief activation. Weaker hyperpolarization resulted in smaller tail currents with slower decay kinetics. (B) Tail current recording at −80 mV from the same cell as in A on a different timescale and at full length. The fitting curve in magenta represents a double-exponential function, and dotted curves of the respective individual components describe the fast and slow deactivation time constant. Voltage protocols for current activation and deactivation are indicated below the traces, and horizontal dotted lines represent zero current. (C) Summary of tail current analysis for Kv4.2 wild-type: Mean values obtained for the fast (τ1 deact, circles) and slow (τ2 deact, inverted triangles) deactivation time constant are plotted on a log scale (left y axis) against the respective tail potential. Straight lines represent exponential functions describing the voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics; apparent charge qapp for τ1 deact is indicated. Relative amplitudes describing the fraction of the total tail current decay accounted for by τ1 deact (right y axis) are illustrated as upright triangles. Dotted lines without symbols represent respective data obtained in symmetrical K+.

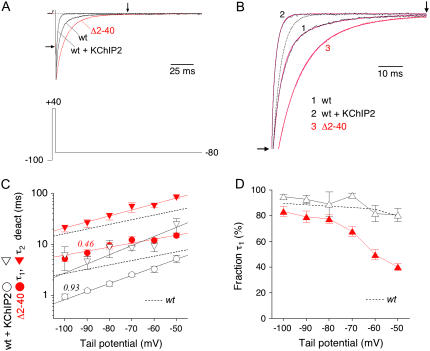

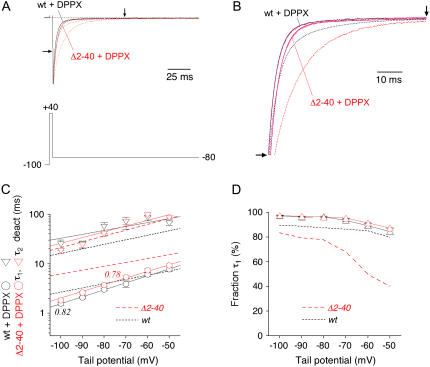

In accordance with previously published results obtained for Kv4.1 and Kv4.3 in the presence of KChIP1 (21), the coexpression of KChIP2 caused an acceleration of Kv4.2 tail current decay (Fig. 3, A and B) with a fast deactivation time constant of ∼2 ms accounting for ∼90% of the total decay at −80 mV (Fig. 3, C and D; Table 2). In contrast to this, a deletion of 39 amino acids from the N-terminal Kv4.2 sequence caused a significant slowing of tail current decay (Fig. 3, A and B), as has been observed previously (8,17,28). The fast time constant of deactivation obtained with Kv4.2Δ2–40 was ∼10 ms and accounted for <80% of the total decay at −80 mV, with a decrease of the relative amplitude at more depolarized potentials (Fig. 3, C and D; Table 2). These results suggested that the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus is involved not only in the control of macroscopic inactivation but also in the control of deactivation. Notably, unlike their effects on the initial A-type current decay kinetics, the effects of KChIP2 coexpression and a 39 amino acid N-terminal deletion on tail current deactivation kinetics are opposite.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of N-terminal deletion and KChIP2 coexpression on Kv4.2 deactivation kinetics. (A) Normalized tail current recordings at −80 mV obtained from three different cells expressing Kv4.2 wild-type (wt) in the absence or presence of KChIP2, or the N-terminal deletion mutants Kv4.2Δ2–40 (Δ2–40; red trace). Horizontal dotted line represents zero current, and outward currents during brief activation are truncated. (B) Zoomed view of tail current decay kinetics corresponding to the recordings shown in A (see arrows in A and B). Outward and instantaneous inward current components not illustrated. Fitting curves in magenta represent double-exponential functions. Dotted curve represents the fast component of wild-type current decay kinetics (see also Fig. 2 B), which is slower than the decay kinetics obtained for wt + KChIP2. (C) Fast (τ1 deact; circles) and slow time constants of deactivation (τ2 deact; inverted triangles) obtained for Kv4.2 wild-type in the presence of KChIP2 (open symbols) and for Kv4.2Δ2–40 (solid red symbols) plotted against the tail potential. Lines represent exponential functions describing the voltage dependence of deactivation kinetics. Broken lines without symbols represent wild-type data in the absence of KChIP2. Note that KChIP2 coexpression accelerates, whereas the N-terminal deletion slows tail current decay kinetics. Unlike N-terminal deletion, KChIP2 coexpression influences the voltage dependence of deactivation time constants (apparent charges qapp for τ1 deact are indicated). (D) Fraction of the total tail current decay accounted for by τ1 deact plotted against the tail potential. Broken line without symbols represents wild-type data in the absence of KChIP2. Note that in contrast to wt + KChIP2 (black) the relative amplitudes of τ1 obtained for Kv4.2Δ2–40 (red) show a decrease at less negative tail potentials.

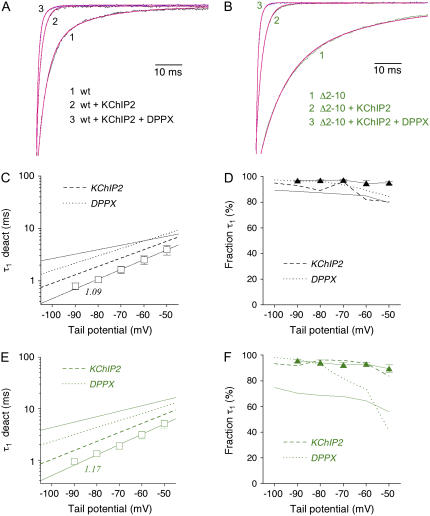

We asked if smaller N-terminal deletions were sufficient to cause a slowing of Kv4.2 channel deactivation. Our experimental results showed that, similar to Kv4.2Δ2–40, the Δ2–20 mutation resulted in a slowing of tail current decay (Fig. 4 A). The fast deactivation time constant was ∼8 ms and accounted for ∼75% of the total decay at −80 mV (Fig. 4 B; Table 2) and a decrease of relative amplitudes at more depolarized potentials. Even the smallest N-terminal deletion tested (Δ2–10) caused a comparable amount of slowing (Fig. 4 C), albeit with a smaller fraction of the initial time constant at −80 mV (∼7 ms; <70%) and, apparently, with a shallower voltage dependence of relative amplitudes (Fig. 4 D; Table 2). Again we exploited the fact that the Kv4.2Δ2–10 mutant was still able to functionally interact with KChIP2, which now allowed a combined examination of the two opposite effects of KChIP2 coexpression and N-terminal deletion on deactivation kinetics. The per se slowly deactivating Kv4.2Δ2–10 mutant exhibited accelerated tail current kinetics in the presence of KChIP2 (Fig. 4 C). Notably, the respective time constants and fractions of decay obtained by exponential fitting were indistinguishable from the values obtained for wild-type in the presence of KChIP2 (Fig. 4, C and D; Table 2). Our data show that a small N-terminal deletion can affect Kv4.2 channel deactivation. However, the modulation of deactivation by KChIP2 appears to be dominant.

FIGURE 4.

Tail current kinetics of Kv4.2 N-terminal deletion mutants in the absence and presence of KChIP2. Kinetic analysis of tail current kinetics including their voltage dependence was performed for Kv4.2Δ2–20 (blue symbols; deactivation time constants in A and relative amplitudes of τ1 deact in (B) and for Kv4.2Δ2–10 (green symbols; deactivation time constants in C and relative amplitudes of τ1 deact in D). (A and B) Red and black broken lines without symbols represent data obtained for Kv4.2Δ2–40 and wild-type, respectively. Note that deleting 19 or 39 N-terminal amino acids results in similar effects on Kv4.2 deactivation kinetics. (C and D) Red and black broken lines without symbols represent data obtained for Kv4.2Δ2–40 and for wild-type + KChIP2, respectively. Note that deleting only nine N-terminal amino acids (green solid symbols) is sufficient to induce slowed deactivation kinetics. However, coexpressing Kv4.2Δ2–10 with KChIP2 induces deactivation kinetics indistinguishable from the ones obtained for wild-type + KChIP2, including a steeper voltage dependence of τ1 deact (see apparent charges qapp).

Interestingly, the apparent charge qapp associated with the fast deactivation component increased ∼2-fold in the presence of KChIP2 (Table 2), as reflected by a steepening of respective τ-V relationships (Figs. 3 C and 4 C). N-terminal deletions, on the other hand, left qapp values largely unaffected (Table 2; Figs. 3 C and 4, A and C), very similar to the effect of switching permeant ion species (see Fig. 2 C and Table 2).

Modulation of Kv4.2 current kinetics by DPPX

Next we studied the effects of DPPX on Kv4.2 channel inactivation and deactivation. In particular, we asked if the proximal N-terminus plays an important role in DPPX-mediated gating modulation. Again we examined A-type current kinetics (Fig. 5) and tail current kinetics (Fig. 6) of wild-type and N-terminal deletion constructs, now in the absence and presence of DPPX. The effects of DPPX coexpression on the inactivation properties of Kv4.2 wild-type, Δ2–40, and Δ2–10 channels were qualitatively similar. In all cases DPPX accelerated the decay kinetics of A-type currents (Fig. 5, A and B) as well as the kinetics of recovery from inactivation (Fig. 5 D), as has been described for wild-type channels previously (19). However, the apparent acceleration of A-type current decay, mainly due to a decrease in the first and second time constant of inactivation (Fig. 5 C), was moderate for Kv4.2Δ2–40. This result may be related to the small relative amplitude of the first time constant of inactivation found for Kv4.2Δ2–40, both in the absence and in the presence of DPPX (Fig. 5 C; see also Table 1). Quantitative differences in macroscopic inactivation kinetics for the three tested channel constructs were preserved in the presence of DPPX (Fig. 5 C). In contrast to this, DPPX exerted a streamlining effect on the recovery kinetics of the respective constructs (Fig. 5 D).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of DPPX coexpression on macroscopic inactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and N-terminal deletion mutants. (A) Normalized A-type currents mediated by Kv4.2 wild-type (black traces) and the N-terminal deletion mutant Kv4.2Δ2–40 (red traces) in the absence and presence of DPPX. (B) Currents mediated by Kv4.2Δ2–10 in the absence and presence of DPPX (green traces) in comparison to respective wild-type traces (black dotted). (C) Results obtained by fitting the sum of three exponentials to the A-type current decay. Vertical dotted lines represent mean values for wild-type time constants in the absence of DPPX. (D) Recovery from inactivation was studied at −80 mV for Kv4.2 wt (black open symbols), Kv4.2Δ2–10 (green open symbols), and Kv4.2Δ2–40 (red open symbols) in the presence of DPPX. Fitting curves represent single-exponential functions, curves without symbols respective data in the absence of DPPX. Note logarithmic x-scaling in C and D.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of DPPX coexpression on deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and N-terminal deletion mutant. (A) Normalized tail current recordings at −80 mV obtained from two different cells expressing Kv4.2 wild-type (black) or the N-terminal deletion mutant Kv4.2Δ2–40 (red) in the presence of DPPX. Dotted curves represent respective data in the absence of DPPX. Note that DPPX exerts a much stronger effect on Kv4.2Δ2–40 deactivation. (B) Zoomed view of tail current decay kinetics corresponding to the recordings shown in A (see arrows in A and B). Fitting curves (magenta) represent double-exponential functions. (C) Fast (τ1 deact; circles) and slow time constants of deactivation (τ2 deact; inverted triangles) for Kv4.2 wild-type (open black symbols) and Kv4.2Δ2–40 (open red symbols) in the presence of DPPX are plotted against the tail potential. Apparent charges qapp from exponential functions describing the voltage dependence of deactivation are indicated for τ1 deact. Broken lines without symbols represent respective data in the absence of DPPX. (D) Fraction of the total tail current decay accounted for by τ1 deact plotted against the tail potential for Kv4.2 wild-type (open black triangles) and Kv4.2Δ2–40 (open red triangles) in the presence of DPPX. Broken lines without symbols represent respective data in the absence of DPPX.

Next, we examined the effect of DPPX on the deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and Kv4.2Δ2–40 channels. For both channel types we observed an acceleration of tail current decay; however, this effect was much more pronounced for the N-terminal deletion mutant, such that in the presence of DPPX the deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and Kv4.2Δ2–40 differed only slightly (Fig. 6, A and B). The fast deactivation time constants were between 3 and 4 ms (Fig. 6 C) and accounted for ∼95% of the total decay at −80 mV (Fig. 6 D; Table 2). Comparable results were obtained with Kv4.2Δ2–10 in the presence of DPPX (data shown in Fig. 8, E and F; see also Table 2). Apparently, DPPX exerted a streamlining effect on both recovery and deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 channels (but see Fig. 8 F, which indicates a decrease in the fractional amplitude of the fast deactivation time constant for Kv4.2Δ2–10 in the presence of DPPX). Similar to KChIP2, DPPX increased the apparent charge qapp associated with the fast deactivation time constant (Table 2; Fig. 6 C), albeit to a smaller extent.

FIGURE 8.

Combined effects of KChIP2 and DPPX coexpression on deactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and N-terminal deletion mutant. (A and B) Zoomed view of normalized tail current recordings at −80 mV obtained from cells expressing Kv4.2 wild-type (A) or the N-terminal deletion mutant Kv4.2Δ2–10 (B) in the absence of accessory subunits, in the presence of only KChIP2, and in the presence of both KChIP2 and DPPX. Fitting curves (magenta) represent double-exponential functions. (C and E) Only fast time constants of deactivation (τ1 deact) for Kv4.2 wild-type and Kv4.2Δ2–10 in the presence of both KChIP2 and DPPX (open circles) are plotted against the tail potential. Straight lines represent exponential functions describing the voltage dependence of deactivation (apparent charges qapp for τ1 deact in the presence of both KChIP2 and DPPX are indicated). Lines without symbols represent data in the absence of accessory subunits (continuous lines), in the presence of only KChIP2 (dashed lines), and in the presence of only DPPX (dotted lines). (D and F) Fraction of the total tail current decay accounted for by τ1 deact (open triangles) plotted against the tail potential for Kv4.2 wild-type (D) and Kv4.2Δ2–10 (F) in the presence of both KChIP2 and DPPX. Lines without symbols represent data in the absence of accessory subunits (continuous lines) in the presence of only KChIP2 (dashed lines) and in the presence of only DPPX (dotted lines).

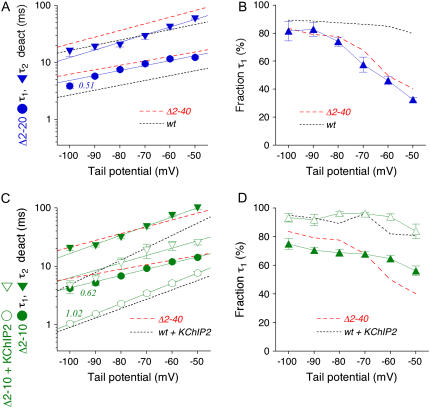

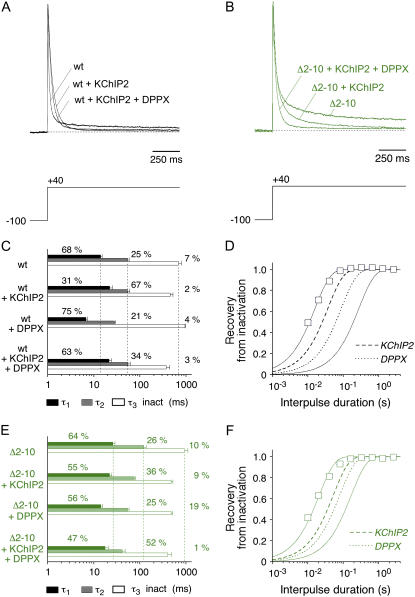

Current kinetics of ternary Kv4.2/KChIP2/DPPX complexes

Native Kv4 channel complexes may be associated with both KChIPs and DPPs (19,31). Therefore, we asked two further questions: 1) Are the effects of KChIP2 and DPPX on Kv4.2 channel gating additive? 2) Does the simultaneous gating modulation by both accessory subunits depend on the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus? For this purpose we tested Kv4.2 wild-type and Kv4.2Δ2–10, now coexpressed with saturating amounts of both KChIP2 and DPPX (see Materials and Methods). For Kv4.2 wild-type channels the KChIP2-induced slowing of the initial A-type current decay was partially reversed; however, the crossover of normalized current traces caused by KChIP2 was preserved in the presence of DPPX (Fig. 7, A and C; see also Table 1). On the other hand, the acceleration of inactivation caused by DPPX was reversed in the presence of KChIP2, whereas the typical KChIP2-mediated acceleration of the slow phase of A-type current inactivation was preserved in the presence of DPPX (Fig. 7 C; Table 1). These data indicated an apparent additivity of the effects caused by KChIP2 and DPPX on Kv4.2 inactivation. This apparent additivity became even more evident when we tested the combined effects of KChIP2 and DPPX on the macroscopic inactivation kinetics of Kv4.2Δ2–10 (Fig. 7 B). In this case the growing acceleration of A-type current decay in the presence of only one or both accessory subunits, respectively, was mainly due to an acceleration of the intermediate phase of macroscopic inactivation (Fig. 7 E; Table 1). The apparent additivity of the effects mediated by KChIP2 and DPPX was best reflected by the kinetic analysis of recovery from inactivation (Fig. 7, D and F). Recovery kinetics were accelerated for both wild-type and Δ2–10 mutant channels, but for either channel type the effect of KChIP2 was stronger than the effect of DPPX (Fig. 7, D and F; Table 1). On the other hand, the effect of either accessory subunit was weaker on Kv4.2Δ2–10 than on Kv4.2 wild-type recovery kinetics (Fig. 7, D and F; Table 1). This result may be related to the faster recovery kinetics obtained for the N-terminal deletion mutant (see Fig. 1 D and Table 1).

FIGURE 7.

Combined effects of KChIP2 and DPPX coexpression on macroscopic inactivation kinetics of Kv4.2 wild-type and N-terminal deletion mutant. (A) Normalized A-type currents mediated by Kv4.2 wild-type in the absence of accessory subunits, in the presence of KChIP2, and in the presence of both KChIP2 and DPPX. (B) Respective currents mediated by Kv4.2Δ2–10. (C and E) Results obtained by fitting the sum of three exponentials to the A-type current decay (C, Kv4.2 wild-type; E, Kv4.2Δ2–10). Vertical dotted lines represent mean values for respective time constants in the absence of accessory subunits. (D and F) Recovery from inactivation at −80 mV (D: Kv4.2 wild-type + KChIP2 + DPPX; F: Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX; open squares). Fitting curves represent single-exponential functions. Curves without symbols represent respective recovery data in the absence of accessory subunits (continuous lines) in the presence of only KChIP2 (dashed lines) and in the presence of only DPPX (dotted lines). Note logarithmic x-scaling in C–F.

Finally, we studied tail current decay kinetics for Kv4.2 wild-type and Kv4.2Δ2–10 coexpressed with both KChIP2 and DPPX to find out if the apparent additivity of accessory subunit effects on macroscopic inactivation also applied to their modulatory effect on deactivation. Our kinetic analysis showed that, similar to the combined effects on recovery from inactivation, DPPX caused only a moderate acceleration of tail current kinetics on top of a large KChIP2 effect (Fig. 8, A–C and E). In the presence of both accessory subunits the fast time constant of deactivation at −80 mV was decreased to ∼1 ms (Fig. 8, C and E) and the relative amplitude was ∼95% for both Kv4.2 wild-type and Δ2–10 mutant channels (Fig. 8, D and F). The ternary complexes showed the largest values for the apparent charge qapp associated with the fast component of deactivation (Table 2; Fig. 8, C and E).

Since the voltage dependence of Kv4.2 channel activation may be influenced by mutation or accessory subunit coexpression (Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material), the starting conditions for tail current measurements (i.e., the fraction of open and/or open inactivated channels) may be different when repolarizing the membrane from a fixed prepulse potential of +40 mV. Therefore we performed, for a number of different channel constructs, tail current measurements following variable prepulse potentials between −20 and +80 mV. The results ruled out a significant contribution of the prepulse potential to the observed effects on tail current kinetics (Fig. S3 of the Supplementary Material).

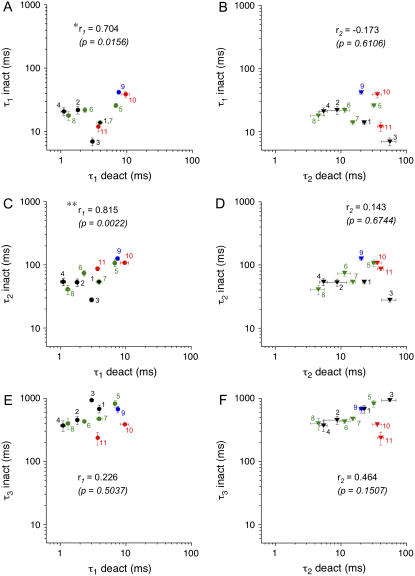

Correlation analysis of modulatory effects on inactivation and deactivation

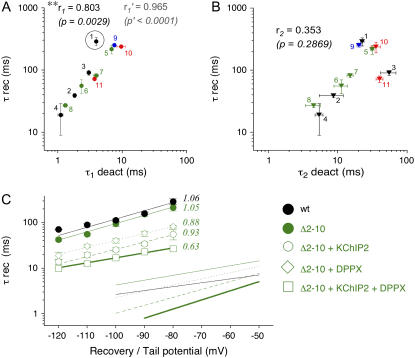

We have analyzed the kinetics of macroscopic Kv4.2 channel inactivation and deactivation, respectively, by fitting the sum of three exponentials to the inactivation phase of A-type currents and the sum of two exponentials to the decay phase of tail currents. Recovery data were analyzed with a single-exponential function. Inactivation and deactivation kinetics were experimentally modified by N-terminal deletions of different extent, by different accessory subunit coexpression, or by a combination of the two maneuvers. This resulted in 11 different Kv4.2 channel complexes with distinct inactivation and deactivation properties (see Tables 1 and 2). To find any hints for a possible mechanistic deactivation-inactivation coupling in Kv4.2 channels, we plotted the respective mean inactivation and deactivation time constants from Tables 1 and 2, respectively, pairwise against each other and applied Pearson's correlation analysis (Figs. 9 and 10, A and B).

FIGURE 9.

Correlation analysis of macroscopic inactivation and deactivation parameters. Mean values of inactivation time constants from Table 1 were plotted against respective mean values of the fast (τ1 deact; solid circles) and the slow (τ2 deact; inverted triangles) deactivation time constant from Table 2 on logarithmic scales. (A and B) τ1 inact; (C and D) τ2 inact; (E and F) τ3 inact. Groups of paired data points for individual channel constructs are represented by different colors (black, Kv4.2 wild-type; green, Kv4.2Δ2–10; blue, Kv4.2Δ2–20; red, Kv4.2Δ2–40), and each type of channel complex is indicated by a number; 1: Kv4.2 wild-type; 2: Kv4.2 wild-type + KChIP2; 3: Kv4.2 wild-type + DPPX; 4: Kv4.2 wild-type + KChIP2 + DPPX; 5: Kv4.2Δ2–10; 6: Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2; 7: Kv4.2Δ2–10 + DPPX; 8: Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX; 9: Kv4.2Δ2–20; 10: Kv4.2Δ2–40; 11: Kv4.2Δ2–40 + DPPX. Correlation coefficients r1 and r2 from Pearson's correlation analysis for τ1 deact and τ2 deact, respectively, are indicated together with respective p-values of significance: * significant correlation with p < 0.05; **significant correlation with p < 0.01.

FIGURE 10.

Correlation analysis of recovery from inactivation and deactivation. Mean values of time constants of recovery from inactivation (τ rec) from Table 1 were plotted against respective mean values of the fast (τ1 deact; A) and slow deactivation time constant (τ2 deact; B) from Table 2 on logarithmic scales. Groups of paired data points for individual channel constructs are represented by different colors (black, Kv4.2 wild-type; green, Kv4.2Δ2–10; blue, Kv4.2Δ2–20; red, Kv4.2Δ2–40), and each type of channel complex is indicated by a number: 1, Kv4.2 wild-type; 2, Kv4.2 wild-type + KChIP2; 3, Kv4.2 wild-type + DPPX; 4, Kv4.2 wild-type + KChIP2 + DPPX; 5, Kv4.2Δ2–10; 6, Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2; 7, Kv4.2Δ2–10 + DPPX; 8, Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX; 9, Kv4.2Δ2–20; 10, Kv4.2Δ2–40; 11, Kv4.2Δ2–40 + DPPX. Correlation coefficients r1 and r2 from Pearson's correlation analysis for τ1 deact and τ2 deact, respectively, are indicated together with respective p-values of significance: *significant correlation with p < 0.05; **significant correlation with p < 0.01. Idealized correlation parameters r1′ and p′ obtained after exclusion of encircled data point (1 in A) are indicated in gray. (C) Voltage dependence of recovery from inactivation. Recovery time constants obtained by single-exponential fitting for Kv4.2 wild-type (black solid circles), Kv4.2Δ2–10 (green solid circles), Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2 (open circles), Kv4.2Δ2–10 + DPPX (open diamonds), and Kv4.2Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX (open squares) were plotted on a semilog scale against the recovery potential. Straight lines represent exponential functions describing the voltage dependence of recovery from inactivation. Apparent charges qapp are indicated. Included in the same plot are corresponding deactivation data: Lines without symbols represent the voltage dependences of the fast time constant of deactivation for the same Kv4.2 channel complexes (wt, continuous black line; Δ2–10, continuous green line; Δ2–10 + KChIP2, dashed green line; Δ2–10 + DPPX, dotted green line; Δ2–10 + KChIP2 + DPPX, bold green line; data from Figs. 2 C, 4 C, and 8 E).

Analyzing our kinetic data this way revealed significant correlations between the fast time constant of deactivation (τ1 deact) and certain inactivation parameters (Figs. 9, A and C, and 10 A), whereas no significant correlation was found between the slow component of tail current decay (τ2 deact) and any of the inactivation parameters tested (Figs. 9, B, D, and F, and 10 B). All significant correlations involving τ1 deact had a positive correlation coefficient, implying that accelerated deactivation kinetics may be coupled to both faster transitions leading to inactivation at positive potentials (Fig. 9, A and C) and faster recovery from inactivation (Fig. 10 A). Data involving the initial A-type current decay phase (τ1 inact) yielded a correlation coefficient of 0.704 (Fig. 9 A). However, stronger correlations were found for the intermediate phase of macroscopic inactivation (τ2 inact; r = 0.815; Fig. 9 C) and for the recovery from inactivation (τ rec; r = 0.803; Fig. 10 A). Intriguingly, the latter parameter seems to be distorted only by the results obtained with wild-type alone (data point 1 in Fig. 10 A), which may reflect the control of deactivation by the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus without a significant effect on recovery from inactivation. Excluding this single data point from our analysis increased the correlation coefficient to 0.965 (Fig. 10 A).

It has been shown previously for Kv4.2 channels in the absence of accessory subunits that the kinetics of recovery from inactivation are strongly voltage dependent, similar to their deactivation kinetics (8). To directly compare the voltage dependences of recovery from inactivation and deactivation, we now measured recovery kinetics for a number of Kv4.2 channel constructs at different membrane potentials and fitted respective τ-V plots assuming exponential voltage dependences (Fig. 10 C; see Materials and Methods). This analysis yielded qapp-values for the kinetics of recovery from inactivation comparable to the ones obtained for the deactivation kinetics; however, no positive correlation of voltage dependences was observed for the two parameters (Fig. 10 C; Tables 1 and 2). Rather, ternary Kv4.2/KChIP2/DPPX complexes with the steepest voltage dependence of deactivation exhibited the shallowest voltage dependence of recovery from inactivation (Fig. 10 C; see also Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We examined the effects of N-terminal deletion and accessory subunit coexpression on Kv4.2 macroscopic inactivation and deactivation kinetics. Our data show that modulatory effects on the major component of Kv4.2 channel deactivation correlate well with respective effects on inactivation, including an intermediate onset component and recovery. We demonstrate that, in the absence of KChIP2, the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus may control both the rapid phase of inactivation and a weakly voltage-dependent component of deactivation. KChIP2 bound to Kv4.2 acts “passively” by immobilizing an N-terminal inactivation domain but also via a separate “active” mechanism to accelerate, in an apparently additive manner with DPPX, a highly voltage-dependent component of deactivation, the cumulative phase of macroscopic inactivation and recovery from inactivation.

Gating transitions underlying Kv4.2 macroscopic inactivation

Most if not all Kv channels undergo a process of inactivation when the membrane is depolarized. Such gating behavior can be formally described by kinetic schemes in which a series of closed states (C) and one or more open states (O) are connected to inactivated states (I; Fig. 11 A).

Initial attempts to mathematically explain non-Shaker gating kinetics have utilized a kinetic scheme with two inactivated states, one connected to the open state and another connected to an intermediate closed state (32). A gating model which allows transitions between multiple closed and closed-inactivated states, similar to the gating behavior of fast voltage-gated Na+ channels (33), has been suggested for ITO channels of the ferret heart (34). Guided by these landmark studies, fully allosteric models have been developed to describe the gating behavior of cloned Kv4 channels (8,16,35–37), and similar models have also been used to describe Kv2 and N-type Ca2+ channel gating (38,39). All of these models, including the one which was used in this study (Fig. 11 A), have in common a prominent closed-state inactivation such that even at moderately depolarized membrane potentials the channels can enter inactivated states. A major implication of these models is that Kv4 channels can only reach the conducting state if the depolarization is strong enough to make the activation pathway reasonably fast. This special case, which results in the generation of A-type currents, was studied in this work. An important question arises in this context: Which gating transitions related to inactivation do Kv4 channels undergo once they have reached the open state?

Kv4 channels may enter open-inactivated states, which leads to the observation of reopening tail currents under certain experimental conditions (17). However, various kinetic considerations support a model in which during long-lasting depolarizations Kv4 channels accumulate in closed-inactivated states: First, the recovery of Kv4.2 channels from inactivation shows equal monoexponential kinetics with equal voltage dependences, whether inactivation has been induced by moderate depolarization below the activation threshold or by strong depolarization, which results in the generation of A-type currents (8). Also, N-terminal deletion, which does influence the onset kinetics of macroscopic inactivation, leaves Kv4.2 channel recovery kinetics and their voltage dependence largely unaffected (8; see also Figs. 1 and 10 C). Finally, isochronal Kv4.3 inactivation curves show different midpoint voltages and slope factors depending on the prepulse length: Protocols with shorter prepulses yield more positive values and shallower curves; protocols with longer prepulses yield more negative values and steeper curves. “Early” shallow curves in a depolarized voltage range and “later” steep curves in a more negative voltage range are indicative of inactivation being transiently coupled to the open state(s) but with longer-lasting depolarization to closed states (37). These time-dependent features of Kv4.3 channel inactivation, but not our Kv4.2 tail current and recovery kinetics (J. Barghaan and R. Bähring, unpublished observation), could be reproduced by a gating model in which the opening step is forward biased (kco > koc) and open-inactivated channels were allowed to close indirectly (37). In other Kv4 gating models, like the one used in this study, the absorbing closed-state inactivation at depolarized potentials is implemented by assuming reverse-biased opening kinetics (kco < koc; Fig. 11 A; Table 3; 8,16). With such a model we were able to simulate experimentally observed typical features of isochronal Kv4.2 inactivation curves (data not shown), which were similar to the ones described previously for Kv4.3 (37).

Reverse-biased Kv4 gating models are based on the idea that open channels, after transiently visiting open-inactivated states (I5 and I6 in Fig. 11 A), have to reopen and close to finally accumulate in closed-inactivated states (at +40 mV mainly I4; Fig. 11 A; 8). This assumption was tested in experiments with Kv4 channels in which delayed channel closure was induced, either by mutations in the region of the cytoplasmic gate (16,17) or by the use of ions with a longer residency time in the Kv channel pore, like Rb+ (8,13). Both manipulations caused a slowing of both tail current deactivation and macroscopic inactivation. Since mutations in the cytoplasmic gate region may in principle also influence conformational changes that allow open-inactivated channels to close, the respective experimental results do not strictly exclude a model which allows this gating transition. However, experiments under biionic conditions have clearly shown that only when actually passing through the pore are Rb+ ions able to influence current decay kinetics (13). In the case of Kv4 channel-mediated A-type currents at positive potentials, this means that open-conducting rather than open-inactivated states are rate limiting during the multiphasic onset of macroscopic inactivation. We used Rb+ only as a tool to allow proper tail current acquisition and analysis by inducing a general slowing of deactivation. For simplicity this effect was implemented in our model by a fixed Rb+-factor applied to the closing rate koc (Fig. 11 A; Table 3). This factor, when applied on top of more specific changes in kinetic parameters (Table 3; see below), was sufficient to reproduce experimentally observed tail current kinetics for each channel type modeled (Figs. 11 D and 12 C).

Kv4.2 tail current deactivation kinetics may reflect different aspects of Kv4.2 inactivation

We examined modifications other than the use of Rb+ and pore mutations, which also lead to a modulation of both deactivation and inactivation of Kv4.2 channels. These included N-terminal deletions, the coexpression of accessory subunits, or a combination of the two maneuvers. As an unbiased way to obtain any hints of a putative kinetic coupling between deactivation and macroscopic inactivation, we performed an extensive correlation analysis (Figs. 9 and 10, A and B), similar to previous considerations concerning the coexpression of Kv4.2 with different DPPs (40). Our results showed that, with the exception of the slow component of inactivation (τ3 inact), the kinetic parameters of macroscopic inactivation significantly and positively correlated with the major component of tail current deactivation τ1 deact. We cannot exclude the possibility that the small relative amplitudes of τ3 inact caused curve fitting inaccuracies which precluded the detection of a positive correlation with deactivation kinetics.

It should be noted that in all experiments the sum of two exponentials was necessary to adequately describe Kv4.2 tail current kinetics. Temporary reopening due to recovery from N-type inactivated states has been considered a possible mechanism underlying the slow component of tail current decay. This idea was based on the apparent absence of double-exponential kinetics in Kv4.2Δ2–40 tail currents when measured in symmetrical K+ (17). However, when symmetrical Rb+ was used in this study two components of tail current decay were also resolved for N-terminal deletion mutants. Occupancy of open-inactivated states unrelated to N- or C-type mechanisms or the occupancy of multiple open states may precede deactivation in Kv4.2 channels, thereby causing double-exponential tail current decay kinetics. The fact that all tested Kv4.2 channel constructs, including N-terminal deletion mutants and Kv4.2/KChIP2 complexes, showed triple-exponential A-type current decay kinetics supports the idea that mechanisms other than N-type inactivation may be involved in Kv4.2 open-state inactivation. In our model I5 and I6 (Fig. 11 A) may account for the existence of distinct open-inactivated states. Multiple open states, although likely, were not implemented in this study. Here we focused mainly on the time constant of the fast component of tail current decay (τ1 deact), which was not dependent on the prepulse potential; i.e., the fractional occupancy of open and/or open-inactivated states did not influence τ1 deact (see Figs. S1 and S3 of the Supplementary Material). What could underlie the correlation between τ1 deact and inactivation parameters? In principle, the initial tail current decay may directly reflect rapid inactivation, which already starts during the prepulse in a more or less voltage-independent manner and proceeds when the membrane is repolarized. However, the strong voltage dependence of τ1 deact (qapp-values between 0.5 and 1.17) and opposite effects of KChIP2 coexpression on rapid inactivation (τ1 inact) and deactivation (τ1 deact; data points 2, 4, 6, and 8 in Fig. 9 A) do not support this explanation.

Most interestingly, without data exclusion we obtained the highest correlation coefficient and the highest degree of significance for our correlation analysis between τ1 deact and the intermediate time constant of macroscopic inactivation (τ2 inact; see Fig. 9 C). Although care should be taken when assigning individual phases of current kinetics to certain channel gating transitions, we consider the possibility that τ2 inact at least in part may reflect the reopening of open-inactivated channels, i.e., the transition from I5 to O in our model (Fig. 11 A). Transient reopening at positive membrane potentials may underlie the typical hold in current decay preceding the cumulative phase of macroscopic Kv4.2 inactivation. The significant positive correlation shown in Fig. 9 C, which is the base for this speculation, can be interpreted as follows: The faster channel closure occurs, the less time channels reside in the intermediate reopened state during macroscopic inactivation. Notably, testing a previously suggested forward-biased model which allows the indirect closure of open-inactivated channels (37), we found double-exponential A-type current decay kinetics (J. Barghaan and R. Bähring, unpublished observation).

A significant correlation with τ1 deact was observed not only for the fast and intermediate onset kinetics of macroscopic inactivation but also for the kinetics of recovery from inactivation (τ rec; Fig. 10 A). Apparently, our correlation analysis reflects at least two different aspects of deactivation-inactivation coupling in Kv4.2 channels. A more detailed and separate examination of the effects caused by accessory subunit coexpression and N-terminal deletions, respectively, strengthens this view: First, the major component of deactivation (τ1 deact), although accelerated by the coexpression of KChIP2 and DPPX, was slowed by N-terminal deletions. Second, tail current kinetics showed altered voltage dependences after accessory subunit coexpression, whereas the voltage dependences were unaffected by N-terminal deletions. This may indicate that KChIP2 and DPPX interactions with Kv4.2 channels affect mainly the highly voltage-dependent transitions between closed states in the deactivation pathway (“voltage sensor” in Fig. 11 A), whereas N-terminal deletions may affect the actual closing step, which is thought to be weakly voltage dependent (“gate” in Fig. 11 A). The adjustment of rates to simulate the respective effects on Kv4.2 channel gating kinetics was done according to these findings (see Table 3). Similar to deleting parts of the proximal N-terminus, measuring tail currents in symmetrical Rb+ instead of K+ slowed tail current decay kinetics but had negligible effects on the apparent charge qapp associated with the deactivation process (see Fig. 2 C and Table 2). Consequently, neither Rb+ nor N-terminal deletions had major effects on the kinetics of recovery from inactivation (Table 1). In contrast to this, KChIP2 and DPPX critically influenced both qapp of deactivation and the kinetics of recovery from inactivation. Our experimental and simulation data are in accordance with a structural model in which uncoupling between voltage sensor and gate is critically involved in inactivation (41). In such a model acceleration of voltage sensor deactivation is expected to also accelerate restorage of coupling, i.e., recovery from inactivation.

The Kv4.2 N-terminus and passive gating modulation by KChIPs

In parallel to the formal description of channel gating based on theoretical models, it is important to define the structural determinants of gating mechanisms and their modulation. We focused on the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus. In some Kv channels, this part of the cytoplasmic N-terminus contains a peptide sequence which may act as an inactivation domain, and the respective mechanism is therefore referred to as “N-type inactivation”. The well-studied Shaker N-type inactivation resembles a “ball-and-chain” reaction (7), where the tethered N-terminal inactivation peptide blocks the channel once it has opened (42). The hydrophobicity of the initial part of the Shaker N-terminus is important for its binding in the open channel cavity (43,44). Positively charged amino acids next to the N-terminal hydrophobic domain may support the inactivation reaction by long-range electrostatic interactions (43,45) or by direct interaction with parts of the channel protein outside the pore (46).

Kv4 channels, void of C-type inactivation (9,13), do undergo a form of open-state inactivation, which is related to the Shaker N-type inactivation mechanism (17). Thus, a 20 amino acid soluble Kv4.2 N-terminal peptide is capable of inactivating Kv4.2Δ2–40 channels, and the proximal Kv4.2 N-terminus induces rapid inactivation when genetically engineered onto the N-terminus of Kv1.5 channels (17). However, the coupling coefficients for a putative ball-receptor interaction in the Kv4.2 channel pore obtained with double mutant cycle analysis (17) were much lower than the ones obtained for the Shaker N-type inactivation (44). Also, although numerous positively charged amino acids can be found in the Shaker N-terminus, only one such residue can be found in Kv4.2 (R13), the mutation of which does not significantly influence inactivation (17). Taken together, N-type inactivation seems to play a minor role in Kv4.2 channel gating. Moreover, the binding of KChIP to the Kv4.2 N-terminus further suppresses N-type inactivation features (17,21,26). This suppression is thought to be due to an immobilization of the Kv4.2 N-terminus when KChIP is bound, and we like to refer to this mechanism as “passive” gating modulation. It is implemented in our model by changing the entry and exit rates for open-inactivated states and by changing the closing rate (Fig. 11 A; Table 3). However, with these passive components of gating modulation alone, which in fact resemble an N-terminal deletion (Table 3), our model does not predict any effects on recovery from inactivation (Fig. 12 B).

Active Kv4.2 channel gating modulation by accessory subunits

We show that small N-terminal deletions (only nine amino acids) in Kv4.2 lead to a slowing of deactivation. Thus, this part of the proximal N-terminus, which represents the “ball” domain in Shaker (43,44), may control deactivation in Kv4.2 channels. A Kv4.2 site homologous to a previously suspected receptor site for the Shaker N-terminal inactivation domain located in the S4-S5 linker (47) may represent a functional interface for the proximal N-terminus to control deactivation. The binding of KChIP to Kv4.2 may induce conformational changes that redirect the proximal N-terminus to this binding site, thereby shifting its functional role from N-type inactivation to an allosteric deactivation control. Our Kv4.2/KChIP2 simulations (Fig. 12; dark gray) account for this idea by a KChIP2-induced change in the closing rate (Table 3). However, our experimental results with a Kv4.2Δ2–10 deletion mutant argue against Kv4.2 deactivation control mediated exclusively via the first 10 amino acids of the proximal N-terminus, since coexpression of this mutant with KChIP2 produced identical effects on tail current kinetics, as observed with wild-type channels. These results suggest an additional mechanism, other than immobilizing and redirecting the proximal N-terminus, as a structural correlate of KChIP-mediated gating modulation of Kv4.2 channels. Notably, a region in Kv4.2 between amino acid 10 and 20 seems to be crucial for inactivation gating since the kinetics of A-type currents mediated by Kv4.2Δ2–10 and Kv4.2Δ2–20, respectively, differ profoundly, whereas those of Kv4.2Δ2–20 and Kv4.2Δ2–40 are very similar (Fig. 1). The region between amino acids 10 and 20 also constitutes the major KChIP interaction site on the proximal N-terminus (23,24,26). In addition, other regions of the Kv4.2 α-subunit, including the T1-domain and the cytoplasmic C-terminus (9,48,49), may also be critically involved in KChIP-mediated gating modulation (23,24,26).

In accordance with previously reported results on Kv4.3 channels (22), we found that the DPPX-mediated acceleration of tail current decay was modest only for Kv4.2 wild-type channels. The DPPX effect was more pronounced for Kv4.2Δ2–40, reminiscent of previous findings with a tarantula gating modifier toxin, which is thought to directly interact with the Kv4.2 voltage sensor (28). Known Kv channel gating modifier toxins favor the closed state and therefore cause an acceleration of tail current kinetics and a shift of the voltage dependence of activation to more depolarized potentials (28,50). However, it is known that DPPX shifts the voltage dependence of Kv4.2 channel activation to more hyperpolarized potentials (19; Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material), suggesting a different mode of interaction. A detailed analysis of gating current measurements suggested that DPPX does interact with the Kv4.2 voltage sensing module, but it seems to support both forward (activation) and backward motions of the voltage sensor (deactivation; 51). Our model accounts for this finding by increased rates with lower voltage dependence for transitions between closed states, and the small voltage dependence of channel opening and closing has been removed (Table 3). The results are illustrated in Fig. 12 (light gray). The transmembrane domain of DPP10 has been shown to interact with S1 and S2 of Kv4.3 (52). The likelihood of a similar mode of interaction for DPPX with the Kv4.2 voltage sensing module needs to be tested. The cytoplasmic N-terminus of accessory DPP subunits is thought to be involved in the acceleration of inactivation onset kinetics (40,53), but the exact mechanism is still unknown. Our Kv4.2/DPPX model accounts for a possible modulation of both closed- and open-state inactivation (Table 3).

Ternary complex formation of Kv4, KChIP, and DPP subunits has been shown in certain brain regions (19,31) and may also occur in the heart (54). The observed effects on Kv4 channel gating after combined coexpression of KChIP and DPP seem to depend critically on the exact types of subunit under study (19,31,54). The results obtained in this study with ternary Kv4.2/KChIP2/DPPX complexes compared to the results obtained with respective binary complexes indicate an apparent additivity of the effects exerted on inactivation and deactivation. Our model simulations for ternary Kv4.2/KChIP2/DPPX complexes account for this apparent additivity by treating respective rates appropriately, i.e., multiplying the individual effects to obtain rates for ternary complexes (see Table 3). The results, which are illustrated in Fig. 12 (magenta), support independent mechanisms of action; however, a more detailed thermodynamic analysis is necessary to draw any decisive conclusions concerning the combined modulation of Kv4.2 gating by KChIP and DPP. The cytoplasmic DPPX N-terminus may indeed influence the functional interaction of KChIP2 with the Kv4.2 cytoplasmic N-terminus. Such interactions may provide an explanation for a shortcoming of our model, which reproduced additive effects of KChIP2 and DPPX on recovery kinetics (Fig. 12 B) but failed to reproduce the same additivity of experimentally observed effects on tail current deactivation kinetics (Fig. 12 C).

Physiological significance of deactivation-inactivation coupling in native Kv4 channel complexes

Moderate depolarizations, as imposed by subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potentials, may cause direct transitions of Kv4.2 channels from preopen-closed to closed-inactivated states. Here the refractory state itself may serve the function of neuronal coincidence detection. During long-lasting strong depolarizations, like the heart action potential or dendritic plateau potentials, Kv4 channel-mediated A-type currents serve the partial repolarization of the membrane potential. In either case, rapid and electrically silent recovery from inactivation in a highly voltage-dependent manner is desirable. Especially in neurons with regular discharge patterns of moderate frequency, a KChIP-regulated Kv4 channel-mediated transient K+ conductance with rapid and voltage-dependent silent recovery may cause shallow voltage ramps between individual spikes (55).

From the extremely fast deactivation kinetics measured in symmetrical Rb+, it may be anticipated that native ternary Kv4 channel complexes under physiological conditions deactivate on a submillisecond timescale. At the same time both onset of macroscopic inactivation and recovery from inactivation are complete in tens of milliseconds. Rapid A-type channel gating kinetics caused by a suppression of N-type inactivation and an acceleration of deactivation provides a K+ conductance which shows an almost instantaneous resetting of the activatable state by hyperpolarization. As our results suggest, accessory KChIP and DPP subunits act synergistically and make the underlying Kv4 channels behave this way.

A high affinity pore-blocking N-type inactivation domain may have evolved to enable the Kv channels in axons and especially in axon terminals to undergo longer lasting refractoriness. In contrast to this, Kv4-related channel proteins have not changed much during evolution, from Caenorhabditis elegans to mammals, underscoring the importance of Kv4-specific gating properties as a basic demand for neuronal and muscular activity. The A-type current has been initially identified in the marine mollusk Anisodoris, where it underlies rhythmic firing (56,57). These features are mediated by the typical subthreshold activation and inactivation combined with rapid recovery from inactivation in a highly voltage-dependent and silent manner. We are now beginning to understand how these features are accomplished on a molecular level.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keiji Wada for the generous gift of the human DPPX clone and Prof. Dr. Christiane K. Bauer for critical comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported by grants Ba 2055/1-1,2 and Ba 2055/1-3 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to R.B.

Editor: Richard W Aldrich.

References

- 1.Baldwin, T. J., M. L. Tsaur, G. A. Lopez, Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 1991. Characterization of a mammalian cDNA for an inactivating voltage-sensitive K+ channel. Neuron. 7:471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pak, M. D., K. Baker, M. Covarrubias, A. Butler, A. Ratcliffe, and L. Salkoff. 1991. mShal, a subfamily of A-type K+ channel cloned from mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:4386–4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon, J. E., W. Shi, H. S. Wang, C. McDonald, H. Yu, R. S. Wymore, I. S. Cohen, and D. McKinnon. 1996. Role of the Kv4.3 K+ channel in ventricular muscle. A molecular correlate for the transient outward current. Circ. Res. 79:659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serodio, P., C. Kentros, and B. Rudy. 1994. Identification of molecular components of A-type channels activating at subthreshold potentials. J. Neurophysiol. 72:1516–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng, M., Y. J. Liao, Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 1993. Presynaptic A-current based on heteromultimeric K+ channels detected in vivo. Nature. 365:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheng, M., M. L. Tsaur, Y. N. Jan, and L. Y. Jan. 1992. Subcellular segregation of two A-type K+ channel proteins in rat central neurons. Neuron. 9:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshi, T., W. N. Zagotta, and R. W. Aldrich. 1990. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 250:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bähring, R., L. M. Boland, A. Varghese, M. Gebauer, and O. Pongs. 2001. Kinetic analysis of open- and closed-state inactivation transitions in human Kv4.2 A-type potassium channels. J. Physiol. 535:65–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerng, H. H., and M. Covarrubias. 1997. K+ channel inactivation mediated by the concerted action of the cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains. Biophys. J. 72:163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu, X.-R., A. Wulf, M. Schwarz, D. Isbrandt, and O. Pongs. 1999. Characterization of human Kv4.2 mediating a rapidly-inactivating transient voltage-sensitive K+ current. Receptors Channels. 6:387–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi, K. L., R. W. Aldrich, and G. Yellen. 1991. Tetraethylammonium blockade distinguishes two inactivation mechanisms in voltage-activated K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:5092–5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Barneo, J., T. Hoshi, S. H. Heinemann, and R. W. Aldrich. 1993. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors Channels. 1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahidullah, M., and M. Covarrubias. 2003. The link between ion permeation and inactivation gating of Kv4 potassium channels. Biophys. J. 84:928–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demo, S. D., and G. Yellen. 1991. The inactivation gate of the Shaker K+ channel behaves like an open-channel blocker. Neuron. 7:743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruppersberg, J. P., R. Frank, O. Pongs, and M. Stocker. 1991. Cloned neuronal IK(A) channels reopen during recovery from inactivation. Nature. 353:657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerng, H. H., M. Shahidullah, and M. Covarrubias. 1999. Inactivation gating of Kv4 potassium channels: molecular interactions involving the inner vestibule of the pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:641–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gebauer, M., D. Isbrandt, K. Sauter, B. Callsen, A. Nolting, O. Pongs, and R. Bähring. 2004. N-type inactivation features of Kv4.2 channel gating. Biophys. J. 86:210–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An, W. F., M. R. Bowlby, M. Betty, J. Cao, H. P. Ling, G. Mendoza, J. W. Hinson, K. I. Mattsson, B. W. Strassle, J. S. Trimmer, and K. J. Rhodes. 2000. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 403:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]