Abstract

Few studies have demonstrated that innate lymphocytes play a major role in preventing spontaneous tumor formation. We evaluated the development of spontaneous tumors in mice lacking β-2 microglobulin (β2m; and thus MHC class I, CD1d, and CD16) and/or perforin, since these tumor cells would be expected to activate innate effector cells. Approximately half the cohort of perforin gene-targeted mice succumbed to spontaneous disseminated B cell lymphomas and in mice that also lacked β2m, the lymphomas developed earlier (by more than 100 d) and with greater incidence (84%). B cell lymphomas from perforin/β2m gene-targeted mice effectively primed cell-mediated cytotoxicity and perforin, but not IFN-γ, IL-12, or IL-18, was absolutely essential for tumor rejection. Activated NK1.1+ and γδTCR+ T cells were abundant at the tumor site, and transplanted tumors were strongly rejected by either, or both, of these cell types. Blockade of a number of different known costimulatory pathways failed to prevent tumor rejection. These results reflect a critical role for NK cells and γδTCR+ T cells in innate immune surveillance of B cell lymphomas, mediated by as yet undetermined pathway(s) of tumor recognition.

Keywords: immunosurveillance, effector, NK cell, tumor, perforin

Introduction

Immune surveillance against tumors has been debated for decades, although it has been well established using experimental tumor cell lines in mAb-treated and gene-targeted mice that the immune system recognizes and inhibits tumor growth (1–8). More recently, interest has shifted to determine whether the immune system can recognize precancerous cells, thus preventing tumor development. Mice deficient in key adaptive and innate immune effector molecules such as perforin (pfp) and IFN-γ have illustrated the importance of these molecules in tumor prevention in aging mice or when predisposing factors such as chemical carcinogens or loss of tumor suppressors drive carcinogenesis (5, 7, 9–11). The lymphomas arising in pfp-deficient mice were of B cell origin, extremely immunogenic, and all susceptible to CD8+ T cell–mediated attack when transplanted into syngeneic WT recipients (5). These data and others (12) supported the important role adaptive immune responses play in spontaneous tumor control.

The role of innate immune cells such as NK cells and γδTCR+ T cells in immune surveillance of tumors remains controversial. Both NK cells and γδTCR+ T cells express perforin (13, 14), mediate spontaneous cytotoxicity, and produce many antitumor cytokines such as IFN-γ, when they recognize target cells via one or more of several cell surface receptors (15, 16). NK cells can spontaneously kill MHC class I–deficient tumor cell lines in vivo (1, 6) and suppress experimental and spontaneous metastasis in mice, but there are few models where NK cells or γδTCR+ T cells prevent primary tumor formation (3, 17–19).

Mice gene targeted for β2-microglobulin (β2m) express little or no cell surface MHC class I, CD1d, or CD16 (Fcγ receptor III; reference 20), have greatly diminished CD8+ T cell numbers, and lack CD1d-restricted T cells. We investigated spontaneous tumor development in aging β2m-deficient mice compared with mice doubly deficient in pfp and β2m, to determine whether the latter mice would develop lymphomas and additional tumors, and whether innate effector cells, such as NK cells and γδTCR+ T cells, could recognize and eliminate such tumors given their lack of MHC class I molecules.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Inbred C57BL/6 WT mice were purchased from The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Melbourne, Australia). The following gene-targeted mice were bred at the Austin Research Institute Biological Research Laboratories (ARI-BRL; Heidelberg, Australia) and at the Peter Mac (East Melbourne, Australia): C57BL/6 perforin deficient (B6 pfp−/−); C57BL/6 β-2-microglobulin deficient (B6 β2m−/−); and C57BL/6 pfp−/− β2m−/− (21). All aging mice were bred, maintained, and monitored as described previously (5). Mean lifespan (age of onset of lymphoma detected) ± standard error of the mean was calculated and probability of significance determined using a Mann-Whitney Rank Sum U test. C57BL/6 RAG-1−/− (Animal Resources Centre, Canning Vale, Western Australia) and C57BL/6 Jα18−/− (backcrossed to C57BL/6 for 12 generations and provided by Dr. M. Taniguchi, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan) mice were bred and maintained at the Peter Mac. Congenic Ly-5.1+ B6 mice were purchased from the Animal Resources Centre and bred with B6 pfp−/− mice to generate a B6 Ly-5.1+pfp−/− line. Mice 6–15 wk of age were used in transplantation studies in accordance with the Peter Mac animal experimental ethics committee.

Flow Cytometry.

The following reagents used for flow cytometry were purchased from BD Biosciences: anti–αβTCR-FITC or APC (H57–597); anti–NK1.1-PE (PK136); anti–Ly5.2-FITC (104); and anti–γδTCR-biotin or FITC (clone GL3). Anti-Fc receptor (2.4G2) was used to prevent nonspecific binding by mAb. Intracellular staining was performed using the Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences) as per their instructions. Analysis was performed on a FACScalibur® using CellQuest software or LSR II using FACsDIVA® software (Becton Dickinson).

Tumor Transplantation Experiments.

Three representative (of many) B cell lymphomas from B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice, β2mNPN-2, β2mNPN-8, and β2mNPN-10 (B220+Ig+ TCRαβ−) were transferred into WT, gene-targeted, and antibody-treated mice. Groups of three to five WT or gene-targeted mice were injected i.p. with increasing numbers of lymphoma cells and observed daily for tumor growth for over 150 d. Some groups of WT and gene-targeted mice were depleted of NK1.1+, asialo-GM1+, or γδTCR+ T cells in vivo by treatment with 200 μg anti-NK1.1 mAb (PK136), rabbit anti–asialo-GM1 antibody (Wako Chemicals), or anti-γδTCR mAb (GL3), respectively, on days −2, 0 (day of tumor inoculation), and then either once or twice a week to deplete subsets as described previously (6, 17, 22, 23).

Peritoneal Challenge and Peritoneal Exudate Lymphocytes (PEL) Cytotoxicity.

The number of cells migrating to the peritoneum was evaluated as described previously (2) in groups of five B6 WT, pfp−/−, or RAG-1−/− mice that had received PBS or tumor cells (104)/0.2 ml i.p. as indicated. Some groups of B6 WT mice were pretreated with 200 μg of one or both of anti-NK1.1 (PK136) and anti-γδTCR (GL3). Peritoneal contents were analyzed for proportions of NK1.1+, γδTCR+, and other leukocytes by flow cytometry as above. The cytolytic activity of the PEL was measured against a series of different target cells (as indicated) at various effector/target ratios using a 4-h 51Cr release assay as described previously (2).

Online Supplemental Material.

Figs. S1–S4 and associated methods are available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20031981/DC1.

Results and Discussion

Spontaneous B Cell Lymphomas Develop in β2m−/− pfp−/− Mice.

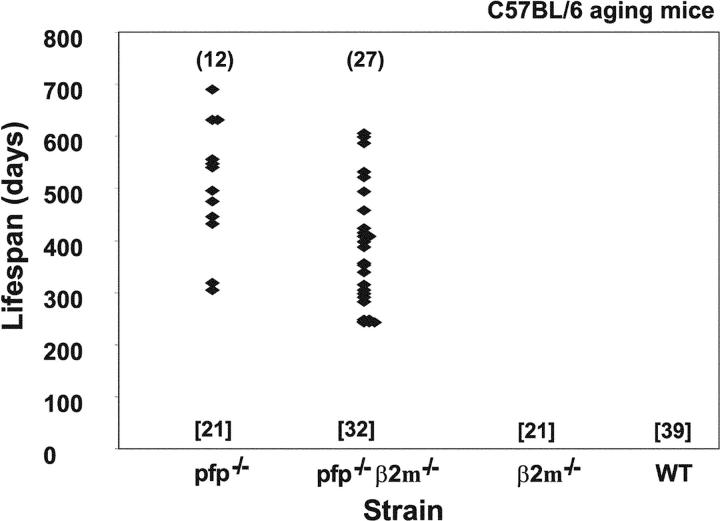

We undertook to monitor spontaneous tumor development in WT C57BL/6 (B6) or those that were deficient in β2m and/or pfp. B6 pfp−/− mice died from aggressive disseminated lymphomas affecting the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes from 300 d onwards, with 57% (12/21) succumbing by the end of the experiment [mean lifespan = 495 ± 35 d] (Fig. 1). B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice developed more disseminated lymphomas (27/32, 84%) and statistically earlier onset (mean lifespan 387 ± 24 d, P = 0.0136). No other tumor types were detected and WT B6 mice (0/39 mice) and mice deficient in β2m (0/21) did not develop any tumors over the same observation period (Fig. 1). The reduced incidence and later onset of lymphomas in B6 pfp−/− mice suggested that in these mice additional nonperforin effector mechanisms mediated by a β2m-dependent recognition process (e.g., by CD8+ T cells or CD1d-restricted NKT cells) might compensate for the loss of pfp. The NK cell compartment of B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice is somewhat “anergic” in response to MHC class I–deficient tumors or cells (21, 24) and this may also explain the earlier onset and greater incidence of lymphoma in these mice. As described previously, all of the disseminated lymphomas in B6 pfp−/− mice were of B cell origin (B220+ sIg+ CD4− CD8− TCR−), or less frequently, plasmacytomas (B220+ CD4− CD8− TCR− sIglow and histological appearance) (10). All the disseminated lymphomas from B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice were also of B cell origin (B220+ sIg+ CD4− CD8− TCR−; Fig. S1). In contrast to the high level of MHC class I expressed by lymphomas emerging in B6 pfp−/− mice (5, 10), those arising in B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice expressed I-Ab, but lacked H-2Kb, H-2Db, and CD1d (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Perforin protects mice from spontaneous B cell lymphomas. Groups of mice (number in square brackets) were evaluated twice weekly and when moribund, a full autopsy was performed and tumor type recorded against time of sacrifice. The lifespan of each pfp−/− and β2m−/−pfp−/− mouse developing a disseminated lymphoma is depicted by a symbol and the total number succumbing shown in round brackets. The lifespan (detected age of onset of lymphoma) of the β2m−/−pfp−/− mice was significantly reduced when compared with that of pfp−/− mice (P = 0.0136, Mann-Whitney).

Both NK Cells and γδTCR+ T Cells Reject B Cell Lymphoma in pfp-dependent Manner.

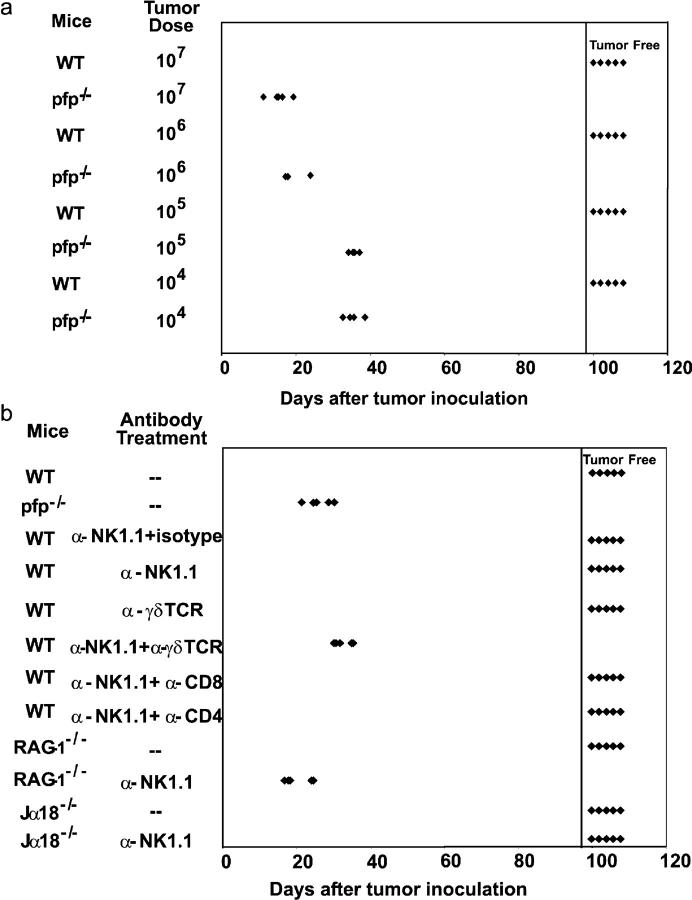

The primary B cell lymphomas arising in B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice grew in B6 pfp−/− mice at doses as low as 104 cells, but not in WT mice at 107 cells (Fig. 2 a). By contrast, mice deficient for one or more of TRAIL, TNF, or FasL rejected 107 tumor cells (Fig. S2), indicating that pfp was the major cytotoxic effector mechanism used in tumor rejection. Mice deficient in IFN-γ, IL-12, and/or IL-18 also rejected these lymphomas, demonstrating that secretion of these cytokines by NK cells or antigen-presenting cells was not critical for tumor rejection (Fig. S2). To establish the effector cell population(s) required for B cell lymphoma rejection, each lymphoma was transferred at 107 cells into a variety of gene-targeted, mutant, or lymphocyte subset–depleted mice (Fig. 2 b and Fig. S2). RAG-1−/− and other T cell–deficient mice rejected B cell lymphomas from B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice, as did nonobese diabetic (NOD) scid mice that lack T cells and have a partial defect in NK cell effector functions (25; and Fig. S2). Only RAG-1−/− mice depleted of NK1.1+ (NK) cells or WT mice depleted of both NK1.1+ cells and γδTCR+ T cells succumbed to lymphoma (Fig. 2 b). Importantly, Jα18−/− mice (deficient in NKT cells) alone or additionally depleted of NK1.1+ cells also rejected the lymphomas, further proving that NKT cells were not critical for tumor rejection (Fig. 2 b). Mice depleted of NK cells or γδTCR+ T cells alone did not develop lymphomas, consistent with the ability of each subset to mediate tumor rejection in the absence of the other (Fig. 2 b). In concert with our previous data (5, 10), all MHC class I–expressing B cell lymphomas from B6 pfp−/− mice grew in B6 pfp−/− mice, but were avidly rejected when transferred into B6 WT mice by CD8+ T cells (unpublished results).

Figure 2.

Spontaneous lymphomas arising in β2m−/−pfp−/− were malignant and rejected by NK and γδ T cells. Groups of five B6 WT and gene-targeted mice were inoculated i.p. with primary lymphomas arising in B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice. Some groups of mice were depleted of NK1.1+ or γδTCR+ cells using Ab or a hamster isotype Ig control as indicated. Transplant of β2mNPN-8 lymphoma cells (104 to 107 cells in 0.2 ml PBS) is representative of all the lymphomas transferred. Individual tumor-free mice remaining after 150 d are represented right of the inserted vertical line and are represented by each symbol. (a) Pfp−/− mice were at least 1,000-fold more susceptible to β2mNPN-8 lymphoma than WT mice. (b) Either NK cells and/or γδ T cells mediated lymphoma rejection.

B Cell Lymphomas Prime NK Cell and γδ+T Cell Activation In Vivo.

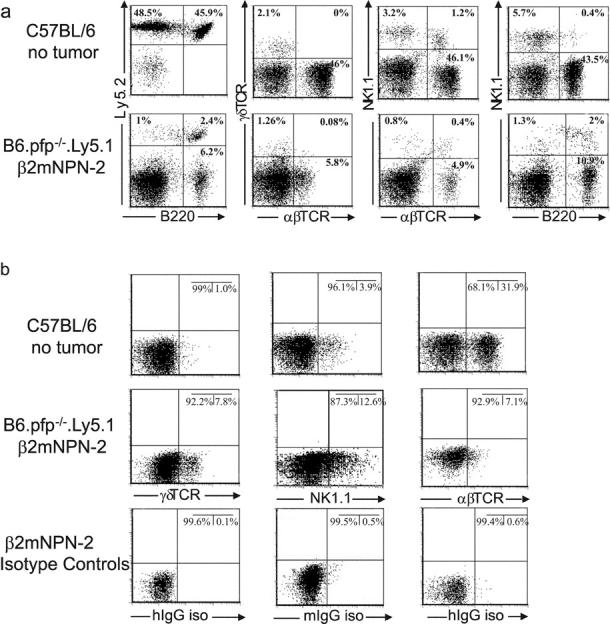

To specifically examine the response of NK cells and γδ+ T cells to B cell lymphomas, we transplanted Ly-5.2+ β2mNPN-8 from B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice into B6.Ly-5.1+pfp−/− mice. 21 d later the cellularity of tumor-burdened spleens was 10–50-fold greater than control B6 mice (unpublished data), with a general increase in most populations (other than B cells), whereas B220+Ly5.2+ cells (2.5%) defined the tumor burden of the B6.Ly-5.1+pfp−/− mice (Fig. 3 a). By cell surface labeling there was no specific increase in the proportion of NK1.1+ or γδTCR+T cells in lymphoma-burdened mice (Fig. 3 a), although an increase in the proportion of NK1.1+B220+ cells (0.40 to 1.58%) was noted. Consistent with internalization of TCR and NK cell receptors upon activation (26, 27), intracellular staining revealed an approximately eightfold and two- to threefold increase in the proportions of γδTCR+ and NK1.1+ cells, respectively, in lymphoma-burdened mice compared with control mice (Fig. 3 b), and thus represented a tremendous increase in the number of γδTCR+T cells and NK1.1+ cells in lymphoma-inoculated mice. The specific internalization of γδTCR and NK1.1 antigens suggested that these cells were being specifically stimulated by the presence of the B cell lymphoma, whereas αβTCR+ T cells were increased in number, but not proportion, and their TCR had not been internalized. The accumulation of NK1.1+ and γδTCR+ cells was further confirmed by their detection around masses of B220+ (and Ly-5.2+) tumor cells (Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

B cell lymphomas induce NK cell and γδ+T cell accumulation in vivo. (a) β2mNPN-2 (Ly5.2+) lymphoma cells (107) were transplanted into B6.Ly-5.1+pfp−/− mice and 21 d later B220+, NK1.1+, γδTCR+, and αβTCR+ populations in tumor-burdened spleens were compared with the spleens of control B6 (Ly5.2+) mice by flow cytometry as indicated. B220+Ly5.2+ cells define the lymphoma amongst spleen cells of the B6.Ly-5.1+pfp−/− mice. (b) Spleen cells prepared in a similar manner to panel a were permeabilized and stained intracellularly. Isotype controls are included.

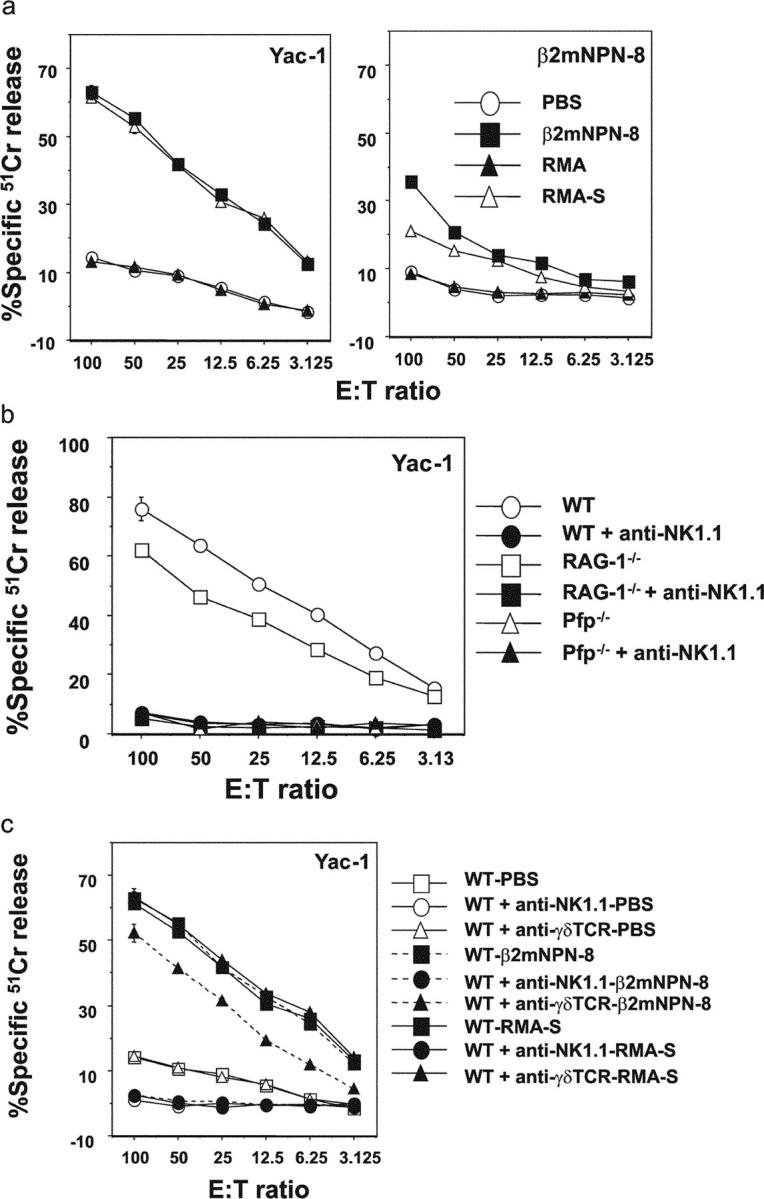

Consistent with previous observations after intraperitoneal challenge with MHC class I–deficient RMA-S tumor cells (2, 28), after 72 h cell number in the peritoneum was enhanced three- to fourfold in all mice inoculated with any of the B cell lymphomas (unpublished data). Importantly, PEL that had been primed by RMA-S or β2mNPN-8 tumor challenge were capable of rapid lysis of either Yac-1 or β2mNPN-8 tumor targets (Fig. 4 a). By contrast, RMA tumor challenge did not stimulate PEL cytotoxicity against Yac-1 or β2mNPN-8 tumor cells and PEL from PBS-inoculated B6 WT mice were only weakly lytic toward β2mNPN-8 and NK cell–sensitive Yac-1 target cells (Fig. 4 a). In addition, freshly isolated spleen mononuclear cells did not significantly lyse β2mNPN-8 tumor cells in 4 or 16 h cytotoxicity assays (unpublished data). PEL from RAG-1−/− mice that had been primed by β2mNPN-8 tumor challenge were capable of rapid lysis of either Yac-1 (Fig. 4 b) or β2mNPN-8 tumor targets (unpublished data). By contrast, despite effective cellular recruitment in pfp−/− mice (unpublished data), PEL from pfp−/− mice that had been primed by β2mNPN-8 tumor challenge were incapable of lysing either Yac-1 (Fig. 4 b) or β2mNPN-8 tumor targets (unpublished data). Furthermore, PEL from β2mNPN-8–primed pfp−/−, RAG-1−/−, or WT mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells were unable to lyse Yac-1 (Fig. 4 c) or β2mNPN-8 target cells (unpublished data). PEL from β2mNPN-8–primed WT mice depleted of γδTCR+ cells were somewhat reduced in their specific ability to lyse Yac-1 (Fig. 4 c). Although NK cells were activated and did mediate enhanced perforin-dependent cytotoxicity against these tumor cells and Yac-1 after priming in vivo, the relatively minor role of γδTCR+T cells in mediating cytotoxicity in this assay may not necessarily correlate with their activation and role in tumor rejection.

Figure 4.

B cell lymphomas prime NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity. (a) β2mNPN-8 lymphoma cells (104) were injected into the peritoneum of groups of 5 B6 pfp−/− mice, B6 WT mice, or WT mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells as indicated. As controls some groups of mice were challenged with either PBS, MHC class I-deficient RMA-S (104) or parental RMA (104) tumor cells. After 72 h, the cytotoxic potential of PEL was assessed in a 4-h 51Cr release assay against Yac-1 or β2mNPN-8 target cells. Results were recorded as the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples and are representative of three experiments. (b) The cytotoxic potential of PEL from WT, RAG-1−/−, or pfp−/− mice primed by β2mNPN-8 tumor challenge (as in A) was assessed in a 4-h 51Cr release assay against Yac-1 target cells. Some groups of mice were pretreated with anti-NK1.1 mAb (100 μg each on days −1 and 1). (c) The cytotoxic potential of PEL from WT mice primed by PBS, β2mNPN-8, or RMA-S tumor challenge (as in a) was assessed in a 4-h 51Cr release assay against Yac-1 target cells. Some groups of mice were pretreated with anti-NK1.1 or anti-γδTCR mAb (100 μg each on days −1 and 1). Results were recorded as the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples and are representative of two experiments performed.

A Novel Mechanism of Tumor Recognition by NK Cells and γδTCR+ T Cells?

All B cell lymphomas arising in B6 pfp−/− β2m−/− mice expressed abundant levels of CD40, CD48, CD70, CD80, and CD86, low levels of NKG2D ligands, and 4–1BBL, but not ICOSL or OX40L (Fig. S4 a). PEL from RAG-1−/− mice that had been primed by β2mNPN-8 tumor challenge remained capable of lysis of either Yac-1 (Fig. S4 b) or β2mNPN-8 tumor targets (unpublished data), even when mice had been pretreated with either a cocktail of neutralizing mAbs to CD40L, CD70, CD80, and CD86 or anti-NKG2D alone. Single or collective inhibition of the NKG2D/NKG2D ligand, CD40L/CD40, CD27/CD70, CD28/CD80, CD28/CD86, CD48/CD2, and CD48/2B4 costimulatory pathways did not prevent lymphoma rejection (Fig. S4 c). As NK cell and γδ+T cell activation may require the simultaneous engagement of stimulatory and costimulatory receptors, it remains to be demonstrated which receptor(s) present the primary signal to these effector cells.

Conclusions.

Evidence for a primary role for NK cells and γδTCR+T cells in tumor immune surveillance has remained scant (17, 19). 40 yr ago Hodgkin's-like B lymphomas spontaneously arising in aging C57L mice (25% incidence at 21 mo of age), were first reported, but only recently were these B cell lymphomas shown to express costimulatory molecules and be controlled by NK cells in syngeneic mice (29). Another study demonstrated that B cell lymphomas arose with higher frequency in Fas mutant lpr mice that were additionally deficient in γδ+T cells or αβ+T cells (30). These experiments were performed on a mixed C57BL/6/MRL background, but suggested that γδ+T cells contribute to the suppression of spontaneously arising B cell lymphomas. Herein, we have directly illustrated in a syngeneic C57BL/6 background an incredibly potent NK cell and γδ+T cell response capable of rejecting spontaneously arising MHC class I–deficient B cell lymphomas. γδTCR+T cells were shown in great numbers around B cell tumor masses in the spleens of B6 pfp−/− mice. Such a response of γδTCR+T cells has not been documented in previous disease models and most often γδTCR+T cells have been shown to inhibit tumors initiated in regions rich in γδTCR-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes such as skin epidermis and gut (19, 31, 32). In addition, the fact that these effector T cells internalized γδTCR suggests that these cells were activated via their TCR and highlights that such activated γδTCR+T cells might be missed if investigators only used staining for surface TCR. A recent study described the ability of γδTCR+T cells to provide an early source of IFN-γ in immune responses to carcinogen (33). Here we have shown that the cytotoxic function of γδTCR+T cells may also contribute to tumor rejection.

NK cells and γδTCR+ T cells potentially use a combination of receptors to detect stressed or transformed tumor cells and may recognize tumors directly with no requirement for antigen processing or presentation. In the past 5 yr we have begun to appreciate the activation receptors expressed by innate effector cells, such as NK cells and γδTCR+T cells (28, 34). Although these B cell lymphomas expressed abundant levels of the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD48, CD70, CD80, and CD86, but lacked NKG2D ligands, blockade of each or several of these pathways also failed to prevent tumor rejection. Although the B cell lymphomas may directly or indirectly stimulate NK cells and γδ+T cells by a soluble mediator, our preliminary analysis of candidate cytokines such as IL-12, IL-18, IFN-γ, and TNF does not support such a contention. Collectively, these data suggest the presence of another, as yet unrecognized, activation receptor that exists on either NK cells or γδTCR+T cells, or both cell types, and promotes perforin-mediated cytotoxicity. This putative receptor does not recognize a β2m-dependent ligand, further suggesting novel receptor/ligand pairs of biological significance remain to be discovered using this tumor model.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Rachel Cameron and the staff of the Peter Mac and ARI-BRL for their maintenance and care of the mice in this project. We also thank Jane Tanner for her production and purification of monoclonal antibodies used in this study.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia through a Dora Lush Scholarship to S.E.A. Street (Monash University, Victoria, Australia), and Research Fellowships and Program Grant to M.J. Smyth, A.M. Lew, and D.I. Godfrey. We also acknowledge the support of a Human Frontier Science Program grant to H. Yagita and M.J. Smyth, and a Cancer Research Institute Post-Doctoral Fellowship to Y. Hayakawa. Y. Zhan and A.M. Lew are supported by a Juvenile Diabetes Foundation Program grant.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

References

- 1.van den Broek, M.F., D. Kagi, R.M. Zinkernagel, and H. Hengartner. 1995. Perforin dependence of natural killer cell-mediated tumor control in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:3514–3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth, M.J., J.M. Kelly, A.G. Baxter, H. Korner, and J.D. Sedgwick. 1998. An essential role for tumor necrosis factor in natural killer cell-mediated tumor rejection in the peritoneum. J. Exp. Med. 188:1611–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyth, M.J., K.Y. Thia, S.E. Street, E. Cretney, J.A. Trapani, M. Taniguchi, T. Kawano, S.B. Pelikan, N.Y. Crowe, and D.I. Godfrey. 2000. Differential tumor surveillance by natural killer (NK) and NKT cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth, M.J., M. Taniguchi, and S.E. Street. 2000. The anti-tumor activity of IL-12: mechanisms of innate immunity that are model and dose dependent. J. Immunol. 165:2665–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smyth, M.J., K.Y. Thia, S.E. Street, D. MacGregor, D.I. Godfrey, and J.A. Trapani. 2000. Perforin-mediated cytotoxicity is critical for surveillance of spontaneous lymphoma. J. Exp. Med. 192:755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smyth, M.J., K.Y. Thia, E. Cretney, J.M. Kelly, M.B. Snook, C.A. Forbes, and A.A. Scalzo. 1999. Perforin is a major contributor to NK cell control of tumor metastasis. J. Immunol. 162:6658–6662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street, S.E., E. Cretney, and M.J. Smyth. 2001. Perforin and interferon-gamma activities independently control tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis. Blood. 97:192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cretney, E., K. Takeda, H. Yagita, M. Glaccum, J.J. Peschon, and M.J. Smyth. 2002. Increased susceptibility to tumor initiation and metastasis in TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 168:1356–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan, D.H., V. Shankaran, A.S. Dighe, E. Stockert, M. Aguet, L.J. Old, and R.D. Schreiber. 1998. Demonstration of an interferon gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:7556–7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Street, S.E., J.A. Trapani, D. MacGregor, and M.J. Smyth. 2002. Suppression of lymphoma and epithelial malignancies effected by interferon gamma. J. Exp. Med. 196:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enzler, T., S. Gillessen, J.P. Manis, D. Ferguson, J. Fleming, F.W. Alt, M. Mihm, and G. Dranoff. 2003. Deficiencies of GM-CSF and interferon gamma link inflammation and cancer. J. Exp. Med. 197:1213–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankaran, V., H. Ikeda, A.T. Bruce, J.M. White, P.E. Swanson, L.J. Old, and R.D. Schreiber. 2001. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 410:1107–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth, M.J., J.R. Ortaldo, Y. Shinkai, H. Yagita, M. Nakata, K. Okumura, and H.A. Young. 1990. Interleukin 2 induction of pore-forming protein gene expression in human peripheral blood CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 171:1269–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakata, M., M.J. Smyth, Y. Norihisa, A. Kawasaki, Y. Shinkai, K. Okumura, and H. Yagita. 1990. Constitutive expression of pore-forming protein in peripheral blood gamma/delta T cells: implication for their cytotoxic role in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 172:1877–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan, K., N. Dimasi, J. Wang, R.A. Mariuzza, and D.H. Margulies. 2002. Structure and function of natural killer cell receptors: multiple molecular solutions to self, nonself discrimination. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:853–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerwenka, A., and L.L. Lanier. 2001. Ligands for natural killer cell receptors: redundancy or specificity. Immunol. Rev. 181:158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth, M.J., N.Y. Crowe, and D.I. Godfrey. 2001. NK cells and NKT cells collaborate in host protection from methylcholanthrene-induced fibrosarcoma. Int. Immunol. 13:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth, M.J., D.I. Godfrey, and J.A. Trapani. 2001. A fresh look at tumor immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girardi, M., D.E. Oppenheim, C.R. Steele, J.M. Lewis, E. Glusac, R. Filler, P. Hobby, B. Sutton, R.E. Tigelaar, and A.C. Hayday. 2001. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science. 294:605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zijlstra, M., M. Bix, N.E. Simister, J.M. Loring, D.H. Raulet, and R. Jaenisch. 1990. Beta 2-microglobulin deficient mice lack CD4-8+ cytolytic T cells. Nature. 344:742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyth, M.J., and M.B. Snook. 1999. Perforin-dependent cytolytic responses in beta2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Cell. Immunol. 196:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajan, A.J., Y.L. Gao, C.S. Raine, and C.F. Brosnan. 1996. A pathogenic role for gamma delta T cells in relapsing-remitting experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in the SJL mouse. J. Immunol. 157:941–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann, S.H., C. Blum, and S. Yamamoto. 1993. Crosstalk between alpha/beta T cells and gamma/delta T cells in vivo: activation of alpha/beta T-cell responses after gamma/delta T-cell modulation with the monoclonal antibody GL3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:9620–9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao, N.S., M. Bix, M. Zijlstra, R. Jaenisch, and D. Raulet. 1991. MHC class I deficiency: susceptibility to natural killer (NK) cells and impaired NK activity. Science. 253:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shultz, L.D., P.A. Schweitzer, S.W. Christianson, B. Gott, I.B. Schweitzer, B. Tennent, S. McKenna, L. Mobraaten, T.V. Rajan, D.L. Greiner, et al. 1995. Multiple defects in innate and adaptive immunologic function in NOD/LtSz-scid mice. J. Immunol. 154:180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowe, N.Y., A.P. Uldrich, K. Kyparissoudis, K.J. Hammond, Y. Hayakawa, S. Sidobre, R. Keating, M. Kronenberg, M.J. Smyth, and D.I. Godfrey. 2003. Glycolipid antigen drives rapid expansion and sustained cytokine production by NK T cells. J. Immunol. 171:4020–4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung, M.M., S. Melgar, V. Baranov, A. Oberg, A. Danielsson, S. Hammarstrom, and M.L. Hammarstrom. 2000. Characterisation of mucosal lymphoid aggregates in ulcerative colitis: immune cell phenotype and TcR-gammadelta expression. Gut. 47:215–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diefenbach, A., E.R. Jensen, A.M. Jamieson, and D.H. Raulet. 2001. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature. 413:165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erianne, G.S., J. Wajchman, R. Yauch, V.K. Tsiagbe, B.S. Kim, and N.M. Ponzio. 2000. B cell lymphomas of C57L/J mice; the role of natural killer cells and T helper cells in lymphoma development and growth. Leuk. Res. 24:705–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng, S.L., M.E. Robert, A.C. Hayday, and J. Craft. 1996. A tumor-suppressor function for Fas (CD95) revealed in T cell-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 184:1149–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girardi, M., E. Glusac, R.B. Filler, S.J. Roberts, I. Propperova, J. Lewis, R.E. Tigelaar, and A.C. Hayday. 2003. The distinct contributions of murine T cell receptor (TCR)γδ1 and TCRαβ1 T cells to different stages of chemically induced skin cancer. J. Exp. Med. 198:747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groh, V., R. Rhinehart, H. Secrist, S. Bauer, K.H. Grabstein, and T. Spies. 1999. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:6879–6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao, Y., W. Yang, M. Pan, E. Scully, M. Girardi, L.H. Augenlicht, J. Craft, and Z. Yin. 2003. γδT cells provide an early source of interferon γ in tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 198:433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerwenka, A., J.L. Baron, and L.L. Lanier. 2001. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:11521–11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]