Abstract

Interferon-γ (IFNγ) is important in regulating the adaptive immune response, and most current evidence suggests that it exerts a negative (proapoptotic) effect on CD8+ T cell responses. We have developed a novel technique of dual adoptive transfer, which allowed us to precisely compare, in normal mice, the in vivo antiviral responses of two T cell populations that differ only in their expression of the IFNγ receptor. We use this technique to show that, contrary to expectations, IFNγ strongly stimulates the development of CD8+ T cell responses during an acute viral infection. The stimulatory effect is abrogated in T cells lacking the IFNγ receptor, indicating that the cytokine acts directly upon CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during acute viral infection.

IFNγ is produced by effector CD8+ T cells, Th1 CD4+ T cells, NK, and NK T cells. Its receptor, which is expressed on many cell types, is a heterodimer of IFNγR1 and IFNγR2, both of which are required for IFNγ signaling (1). IFNγ is essential for the control of many microbial infections, acting very early to reduce the infectious burden; mutations in either the cytokine or its receptor lead to recurrent bacterial or parasitic infections in humans (2). The important role of IFNγ in immune defense is further highlighted by the fact that several viruses encode proteins designed to interfere with IFNγR signaling (3, 4). IFNγ also modulates the adaptive immune response. It has several indirect effects on CD8+ T cell activity: for example, IFNγ induces expression of the immunoproteasome, the TAP transporter proteins and MHC class I molecules, thus rendering intracellular pathogens more visible to the CD8 wing of the adaptive immune response. These indirect effects of IFNγ should generally enhance CD8+ T cell activity but, conversely, its direct effects on T cells are thought to be negative (suppressive). T cells treated with IFNγ show reduced proliferation and/or increased apoptosis (5, 6), and mice lacking IFNγ generate greater numbers of Listeria-specific CD8+ T cells than do wild-type mice (7); IFNγ also is thought to eliminate Mycobacterium-specific CD4 T cells by inducing apoptosis (8). IFNγ favors Th1 cell differentiation of CD4 T cells, and inhibits Th2 cell differentiation, apparently through down-regulation of the IFNγR on Th1 cells, which protects them from the suppressive effects of IFNγ; whereas Th2 cells continue to express the receptor, and are suppressed by the cytokine (9, 10). Therefore, current understanding holds that the direct effects of IFNγ on T cells are suppressive, and possibly proapoptotic.

Our laboratory has recently reported that IFNγ produced by CD8+ T cells plays a key role in establishing the differences in abundance between dominant and subdominant CD8+ T cell populations (i.e., IFNγ is required for immunodominance; 11). Furthermore, we have found that the rapidity of IFNγ expression by CD8+ T cells correlates with their ultimate abundance; fast-expressing cells become more numerous than slow expressers (12). These data could be explained by either positive or negative effects of IFNγ (i.e., IFNγ could regulate the relative abundances of different T cell populations either by actively stimulating some cell populations, or by actively suppressing others); and these regulatory effects on T cell abundance could be indirect (for example, via antigen-presenting cells) or direct. The present study was designed to determine (a) whether the effect of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells was stimulatory or suppressive; and (b) whether the cytokine acted directly on T cells, or indirectly.

Results and Discussion

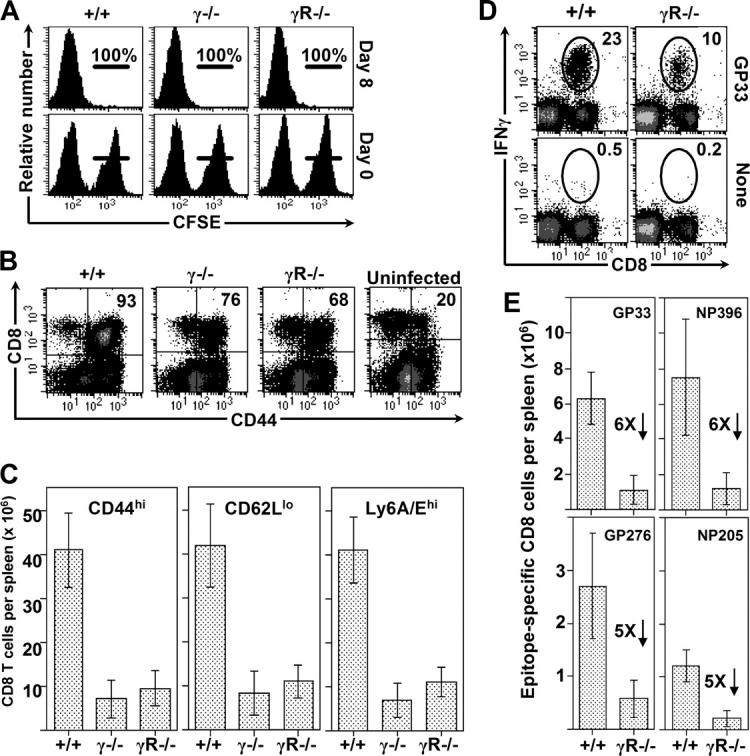

CD8+ T cell abundance is markedly reduced in the absence of IFNγ or IFNγR

The primary CD8+ T cell responses to acute LCMV infection were compared in mice genetically deficient in either IFNγ (γ2/−) or IFNγR1 (γR−/−). After infection, the mice displayed strong in vivo virus-specific cytotoxicity (Fig. 1 A), consistent with earlier in vitro reports (13, 14), and they retained the capacity to reduce viral burden by several orders of magnitude (unpublished data). However, as judged by CD44 expression, lower proportions of CD8+ T cells were activated in γ2/− and γR−/− mice (Fig. 1 B), and this reduction was magnified by an ∼3-fold reduced cellularity in the spleens; as a result, mice deficient in the IFNγ pathway had 5- to 10-fold fewer activated T cells (Fig. 1 C). This 80–90% reduction occurs in the virus-specific population, as revealed by ICCS analyses in wild-type and IFNγR−/− mice: there was a two- to threefold lower frequency of responding (IFNγ+) cells in the receptor-deficient mice (Fig. 1 D) which, together with the reduced cellularity, resulted in a profound reduction in antigen-specific T cell numbers (Fig. 1 E). These data indicate that (contrary to current dogma) IFNγ strongly stimulates CD8+ T cell responses.

Figure 1.

CD8+ T cell abundance is markedly reduced in the absence of IFNγ or IFNγR. (A) The CTL response induced in IFNγ2/−, IFNγR−/−, and control C57BL/6 mice 8 d after infection was measured in vivo by injecting GP33-coated CFSEhi and uncoated CFSElo target cells into mice. The numbers indicate the percentage of peptide-coated cells deleted in the recipient mice. (B) Dot plots show CD44 expression by splenocytes at 8 d after infection. An uninfected C57BL/6 mouse is shown for comparison. (C) Bar graphs depict the number of activated cells that are CD44hi, CD62Llo, or Ly6A/Ehi in infected mice. (D) The virus-specific responses in wild-type and IFNγR− mice were quantified at day 8 after infection by ICCS. GP33–41-specific cells are identified by ovals, and the numbers indicate the percentage of specific cells among all CD8+ T cells. (E) The numbers of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells, based on the spleen cell count and intracellular staining, are shown, along with the fold reductions between +/+ and γR1−/− mice. The bars represent the average ± SD from five or six mice per group, from four independent experiments. For each group, the p-value compared with +/+ mice is <0.001 (unpaired Student's t test).

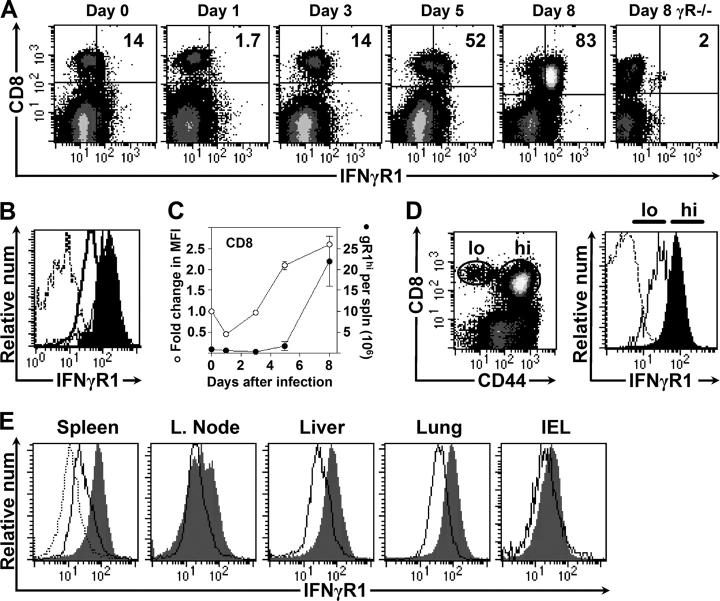

Expression of the IFNγR1 on CD8+ T cells varies over the course of viral infection

Next, the expression of IFNγR1 on CD8+ T cells was evaluated over the course of virus infection (Fig. 2 A). 14% of CD8+ T cells expressed the receptor before infection and, 8 d after infection, 83% were γR1+. IFNγR1 expression also was up-regulated on CD8+ T cells after infection of IFNγ2/− mice (Fig. 2 B), consistent with IFNγ-independent, TCR-mediated, induction of the receptor, as suggested previously (15). The kinetic analysis of γR1 expression (Fig. 2 A) indicated that there was a brief decrease in the proportion of CD8+ T cells expressing γR1 at 1 d after infection. The mechanism underlying this event is unknown, but at this early time after infection, innate immune responses are predominant (16); however, a role for adaptive immunity cannot be excluded, because recent data have shown that naive T cells elaborate IFNγ within hours of first encountering cognate antigen (17). This transient down-regulation of γR1 is followed by progressively increased expression from days 3 to 8 of infection; and, as shown in Fig. 2 C, both the number of CD8+ T cells expressing the receptor (•), and their level of expression (MFI; ○), increase as the infection proceeds. Elevated γR1 expression was associated with activated, CD44hi cells (Fig. 2 D). Similar changes in γR1 expression were seen in other peripheral tissues (Fig. 2 E), indicating that the changes observed in the spleen probably represent cell-intrinsic alterations of expression, rather than changes in migratory patterns (for example, γR1+ cells entering and γR1− cells exiting the spleen).

Figure 2.

Expression of the IFNγR on CD8+ T cells varies over the course of viral infection. (A) Representative dot plots show changes in expression of IFNγR1 on T cells after infection. The percentages of CD8+ T cells expressing elevated amounts of the receptor are shown. (B) IFNγ2/− CD8+ T cells express normal amounts of IFNγR1 before infection (unshaded histogram), and up-regulate expression 8 d after infection (shaded histogram). Dotted line shows an isotype control antibody. (C) Changes over time in the geometric mean fluorescence of IFNγR1 on wild-type splenic CD8+ T cells (○) and the number of IFNγR1+ cells per spleen (•). (D) Resting (CD44lo) and activated (CD44hi) CD8+ T cells are identified by a dot plot (left) and expression of IFNγR1 among these cells is shown by the histograms (right). Dotted line shows an isotype control antibody. (E) IFNγR1 expression on CD8+ T cells in the indicated tissues of uninfected mice (unshaded) or of day 8 mice (shaded). The dotted histogram shows the decreased expression in spleen at one day after infection; in the other tissues, the change in fluorescence at this time was minimal.

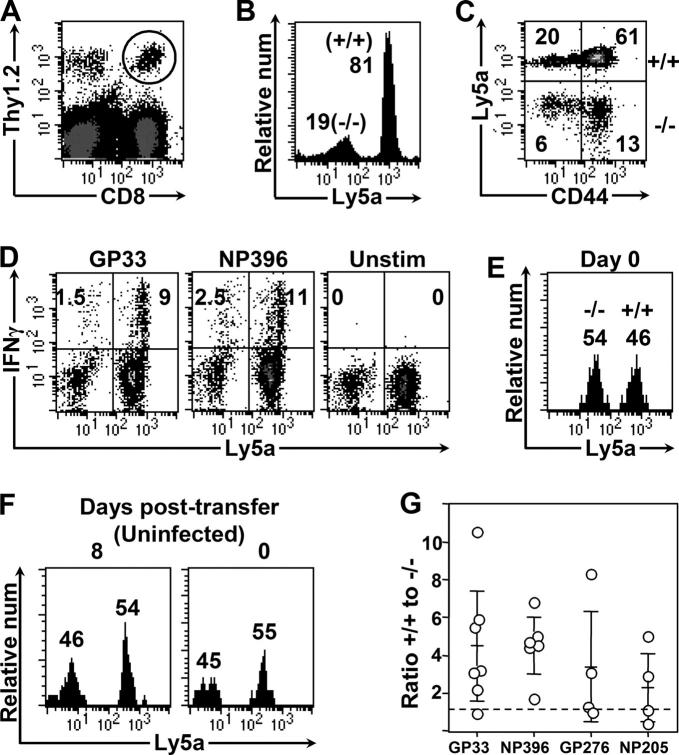

IFNγ exerts its effect directly on CD8+ T cells

The observation that IFNγR levels on CD8+ T cells change over the course of infection (Fig. 2) is consistent with the hypothesis that IFNγ acts directly on CD8+ T cells to modulate their abundance. The diminished abundance of CD8+ T cells in IFNγR− mice (Fig. 1) also is consistent with this hypothesis; however, since none of the cells in these knockout mice express the receptor, it remains possible that the effect of IFNγ on T cells is indirect. Furthermore, the interpretation of T cell data after infection of IFNγ or IFNγR mice is difficult, because these mice show altered clearance of virus, and the increased viral burden and/or antigen load might alter the T cell response. To determine whether the effects of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells are direct, and to circumvent the issues relating to virus/antigen load, we have developed a novel dual adoptive transfer model. Spleen cells from wild-type mice congenic for the Ly5a marker (Thy1.2, Ly5a) were mixed with spleen cells from γR−/− (Thy1.2, Ly5b) mice, so that the number of CD8+ T cells in each group was equal. The cells were transferred into unirradiated, wild-type mice (Thy1.1, Ly5b) that were infected 1–2 d later. These recipient mice are fully immunocompetent, and eradicate the virus infection with normal kinetics. 8 d after infection, the responding CD8+ donor cells (all Thy1.2) can be readily identified (Fig. 3 A). Among these donor CD8+ T cells, wild-type cells (Ly5a+) responded more vigorously to infection than IFNγR1−/− cells (Ly5b+), indicating that IFNγ directly stimulates CD8+ T cells, leading to their increased abundance (Fig. 3 B). The activation status of wild-type and IFNγR−/− donor populations was similar, as indicated by increased expression of CD44 (Fig. 3 C), and both populations made IFNγ in response to ex-vivo antigen stimulation (Fig. 3 D). The increased abundance of IFNγR+ CD8+ T cells in response to infection was not due to differences in “take” immediately after adoptive transfer, because the relative proportion of cells transferred to the same mice was approximately equal immediately before infection (Fig. 3 E). Furthermore, these changes were due specifically to infection (and not preferential rejection of γR−/− cells) because mice given these cells but not infected showed no change in the proportion of wild-type to γR−/− donor cells at day 0 and 8 d later (Fig. 3 F). In this experimental model, both populations of donor cells are exposed to the same environment, so the differences in abundance are not due to differences in APC activation, IL-2 production, lymphoid architecture, or antigen load; we conclude that IFNγ acts directly on CD8+ T cells, thereby up-regulating the primary CD8+ T cell response to infection. As noted above, previous analyses using IFNγ2/− mice indicated that the immunodominance hierarchy is influenced by IFNγ. To address whether IFNγ signaling affected the abundance of CD8+ T cells specific for a variety of epitopes, epitope-specific responses were measured in these mice (Fig. 3 G). As was seen for GP33–41 (presented by H-2Db), differences of two- to sixfold also were observed for CD8+ T cells specific to NP396–404 (H-2Db), GP276–286 (H-2Db), and NP205–212 (H-2Kb) indicating that both dominant and subdominant responses, and responses restricted to different MHC molecules, are increased when the T cells express IFNγR1. To investigate whether IFNγ signaling in CD8+ T cells was autocrine in nature, a second dual adoptive transfer was performed, this time mixing Thy1.2,Ly5b IFNγ2/− cells (which express IFNγR) and Thy1.2,Ly5a wild-type cells. IFNγ2/− CD8+ T cells expanded to the same extent as the cotransferred wild-type cells (unpublished data), indicating that autocrine production of IFNγ is not required for normal CD8+ T cell responses.

Figure 3.

The stimulatory effect of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells requires that they express IFNγR. Equivalent numbers of wild-type (Thy1.2+, Ly5a+) and IFNγR−/− (Thy1.2+, Ly5a−) CD8+ T cells were mixed and adoptively transferred intravenously into unirradiated, Thy1.1 mice. The recipient mice were infected and the responses of the donor (Thy1.2+) cells were measured 8 d after infection. (A) Representative dot plot shows the expanded donor cell populations (Thy1.2+), and these cells were gated, and are analyzed in B–G. (B) IFNγR+ CD8+ T cells outnumber their IFNγR− counterparts by ∼4:1. (C) CD44 expression on donor cells; the percentage of cells within each quadrant is shown. (D) The antigen-specific response of the donor cells was measured by ICCS. The numbers represent the responding donor cells as percentage of all donor cells. (E) The proportion of wild-type and IFNγR1− donor CD8+ T cells in these same mice at day 0 (measured in the blood before infection) is shown. (F) The percentage of donor cells that are Ly5a+ or Ly5a− in an uninfected recipient mouse at day 0 (measured in blood) and 8 d later (measured in spleen). (G) The ratio of +/+ to γR−/− donor cells is shown for four epitopes, based on ICCS. Each point represents an individual animal, and the means ± SD are shown as horizontal lines. For each of four epitopes, the responses in +/+ and −/− cell populations were compared using unpaired Student's t test. The p-values are: 0.0039 (GP33); 0.0001 (NP396); 0.021 (GP276); and 0.038 (NP205).

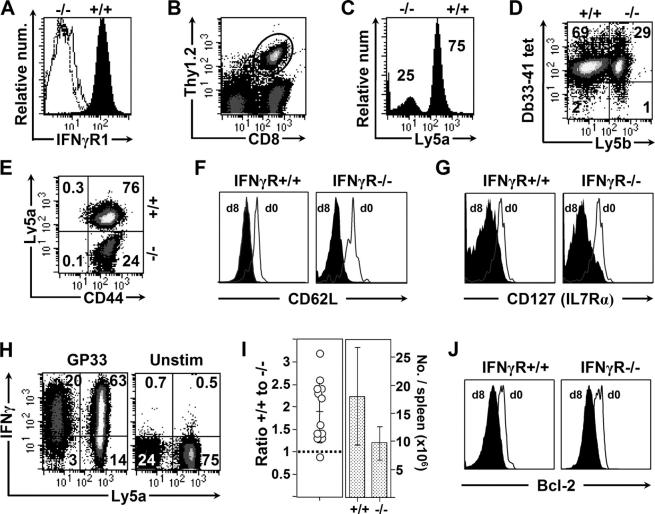

The stimulatory actions of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells occur during the course of virus infection

The reduced response of IFNγR− T cells to LCMV infection, shown above, most likely reflects the lack of IFNγ signaling during infection. Nevertheless, other explanations are conceivable; e.g., although equivalent numbers of IFNγR− and IFNγR+ CD8+ T cells were cotransferred into recipient mice, it is formally possible that the frequency of LCMV-specific precursors within each population might have been different. To ensure that equivalent numbers of LCMV-specific precursors were being transferred, we used TcR-transgenic mice. GP33–41 TcR-transgenic mice were backcrossed either to wild-type mice expressing Ly5a (to provide a source of TcR-transgenic IFNγR+, Thy1.2+, Ly5a+ CD8+ T cells), or to the IFNγR−/− mice (as a source of TcR-transgenic IFNγR−/−, Thy1.2+, Ly5b+ cells), and 3 × 104 CD8+ T cells from each population were mixed (Fig. 4 A) and adoptively transferred into a normal Thy1.1 recipient mouse. By day 8 after infection, the Thy1.2-transgenic cells had expanded dramatically, to 1–4 × 107 cells per spleen, and were easily identifiable as a large proportion of the CD8 response (Fig. 4 B). Consistent with our findings using nontransgenic T cells, the IFNγR+-transgenic T cells (Ly5a+) responded better than the IFNγR−/−-transgenic cells in the same host (Fig. 4 C). Tetramer staining reflected the numerical difference between IFNγR+/+ and IFNγR−/− cells (Fig. 4 D). At 8 d after infection, all of the transferred cells, regardless of their IFNγR status, showed a highly activated phenotype; they were CD44hi, and showed down-regulation of CD62L and IL-7Rα (Fig. 4, E–G) as well as increased expression of CD43 (1B11) and IL-2Rβ (CD122; unpublished data). The similarities in phenotypic markers were paralleled by equivalent antigen responsiveness: 85% of IFNγR− cells, and 82% of IFNγR+ cells, produced IFNγ in response to GP33 peptide (Fig. 4 H). Thus, the presence or absence of the IFNγR has little effect on CD8+ T cell activation or antigen-responsiveness, but it has a considerable effect on T cell abundance. The latter is summarized by results from 12 individual recipient mice (Fig. 4 I); IFNγR+ cells almost always outnumbered their IFNγR−/− counterparts. The abundance of CD8+ T cells is determined by the balance between cell proliferation and cell death. The latter is thought to be mediated largely by apoptosis, and we considered the possibility that IFNγ might increase the levels of antiapoptotic proteins in CD8+ T cells. Therefore, we evaluated the expression of the antiapoptotic protein bcl-2, and found it to be similar in IFNγR+ and IFNγR− CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4 J); the reduction observed at day 8 in wild-type cells is consistent with published data (18), and also occurs in IFNγR− cells.

Figure 4.

The stimulatory actions of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells occur during the course of virus infection. TcR-transgenic mice were bred as described in the text, to provide a source of IFNγR1+ TcR-transgenic CD8+ T cells (Thy1.2+, Ly5a+), and IFNγR1−/− TcR-transgenic CD8+ T cells (Thy1.2+, Ly5a−). (A) Equal numbers of these IFNγR1+ (shaded)- and IFNγR1−/− (unshaded)-transgenic CD8+ T cells were mixed and are shown (dotted line = isotype control). This 1:1 mix of IFNγR1+ and IFNγR1− cells was injected into Thy1.1 recipients (each host mouse received a total of 6 × 104 TcR-transgenic CD8+ T cells), and the following day the recipient mice were infected. 8 d later, the responses of the two donor cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The expanded Thy1.2 TcR-transgenic donor cells are enclosed in an oval, and only these cells are analyzed in C–J. (C) There are threefold more IFNγR+ (Ly5a+) cells than IFNγR− cells. (D) The higher number of IFNγR1+ cells is confirmed by Db33-41 tetramer staining. (E–G) The activation status of the day 8 donor cells is similar, regardless of their expression of IFNγR. The cells are CD44hi, and at day 8, both donor populations show similar reductions in CD62L and CD127. (H) A similar proportion of each donor cell population produces IFNγ upon GP33 peptide stimulation. (I) The ratio of +/+ to IFNγR−/−-transgenic donor cells is summarized from 12 mice analyzed from three independent experiments (left); 11 of the 12 animals showed a ratio >1 (dotted line). The numbers of IFNγR1+ and γR−/−-transgenic cells were calculated from 12 mice (right). The averages ± SD are indicated. The differences between the two groups was statistically significant, as indicated by a p-value of 0.0025, derived from a two-tailed paired Student's t test. (J) The antiapoptosis marker bcl-2 is reduced at day 8, to the same extent in the IFNγR+ and the IFNγR− populations.

In summary, we show here that IFNγ acts directly on CD8+ T cells, thereby increasing their abundance. Although the mechanism underlying the increase in T cell numbers remains to be determined, it is known that very early events can have a profound effect on the effector and memory phases of CD8+ T cell responses (19–21), and recent data indicate that IFNγ and its receptor play a key role in directing the very earliest stages of naive CD4+ cell commitment (22). Our data provide a possible explanation for the observations that (a) IFNγ modulates the immunodominance hierarchy of CD8+ T cell responses (7, 11), and (b) the rapid onset of IFNγ production by a CD8+ T cell may determine the ultimate abundance of its progeny (i.e., its immunodominance; 12). We propose that, early in the immune response, IFNγ produced by a CD8+ T cell can act directly upon the cell itself, or upon neighboring CD8+ T cells, enhancing their ultimate abundance. Consistent with this possibility, gene chip analyses of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from the acute phase of the response show induction of a number of IFNγ-activated genes (23). The conclusion that IFNγ serves as a growth factor/costimulatory molecule for T cell responses is at odds with previous studies showing that IFNγ suppresses T cell responses. Increased T cell responses occur in IFNγ2/− mice given rLM(ActA−) or Mycobacterium (7, 8), but this could reflect delayed pathogen clearance, resulting in a greater antigen load that stimulates continued T cell proliferation. Others have shown that CD8+ T cells in LCMV-infected IFNγR− mice are hyperproliferative; although in that model, there is a delay in virus clearance that may modify the T cell response (24). Can our findings be integrated with current dogma? The biological effects of several cytokines differ depending on the time at which they are expressed. For example, IL-2 can either enhance T cell responses or inhibit them, depending on when it is administered during virus infection (25, 26), and IFNα/β can enhance T cell responses (27) but also can induce T cell apoptosis (28). Perhaps the effect of IFNγ on CD8+ T cells also changes over the course of an ongoing immune response, as suggested by studies of transformed human T cells (29); its early effects may be stimulatory (as shown here), and its later effects suppressive. Our demonstration that IFNγ may stimulate, rather than abrogate, T cell responses may provide an explanation for the deleterious effects of this cytokine when used to treat multiple sclerosis (30), and counsels caution for its future use in autoimmune diseases, and in other circumstances in which immunostimulation might be harmful.

Materials and Methods

Mice and virus.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) breeding facility. IFNγ2/− mice and IFNγR1−/− mice (both strains backcrossed 10 generations to C57BL/6), and C57BL/6 mice congenic for Thy1.1 were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory. C57BL/6.Ly5a mice were provided by Dr. Charlie Surh (TSRI). P14 TCR-transgenic mice specific for the LCMV epitope GP33–41 were crossed to C57BL/6.Ly5a mice to generate TcR-transgenic IFNγR+ Ly5a mice; and to C57BL/6 IFNγR1−/− mice to generate TcR-transgenic IFNγR− Ly5b mice. Mice were infected by intraperitoneal administration of 2 × 105 plaque forming units of LCMV, Armstrong strain. All experiments were approved by the TSRI Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry.

Spleen cells were stained directly ex vivo with anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.7), anti-Thy1.2 (CD90.2 clone 53–2.1), anti-CD44 (clone IM7), Ly6A/E (clone D7), and anti-Ly5.1 (Ly5a, clone A20; eBioscience). Antibodies used for staining IFNγR1 (rat, clone GR20) and the corresponding isotype control antibodies were purchased from BD-PharMingen. The intracellular staining (ICCS) assay was performed as described previously (11). In vivo cytotoxicity was assayed by labeling naive B6.Ly5a splenocytes with either 3 or 0.3μM CFSE (5,6-carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; Molecular Probes). The CFSEhi cells were coated with the GP33 peptide, and the CFSElo cells were left uncoated. After extensive washing, equal numbers of the CFSEhi and CFSElo cells were mixed, and transferred into either naive recipients or day 8–infected mice. After 8 h, Ly5a+ cells were identified by flow cytometry; the percent killing was calculated as 100−{[(% peptide coated in infected/ % uncoated in infected)/(% peptide coated in uninfected/% uncoated in uninfected)] × 100}. Cell staining was analyzed by four-color flow cytometry at the TSRI core facility using a BD Biosciences FACSCALIBUR and Cell Quest software.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annette Lord for excellent secretarial support. This is manuscript number 16687-NP from the Scripps Research Institute.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI-27028 and AI-52351.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Rodig, S., D. Kaplan, V. Shankaran, L. Old, and R.D. Schreiber. 1998. Signaling and signaling dysfunction through the interferon gamma receptor. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 9:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jouanguy, E., R. Doffinger, S. Dupuis, A. Pallier, F. Altare, and J.L. Casanova. 1999. IL-12 and IFN-γ in host defense against mycobacteria and salmonella in mice and men. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcami, A., and G.L. Smith. 1995. Vaccinia, cowpox, and camelpox viruses encode soluble gamma interferon receptors with novel broad species specificity. J. Virol. 69:4633–4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan, S., A. Zimmermann, M. Basler, M. Groettrup, and H. Hengel. 2004. A cytomegalovirus inhibitor of gamma interferon signaling controls immunoproteasome induction. J. Virol. 78:1831–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Refaeli, Y., L. van Parijs, S.I. Alexander, and A.K. Abbas. 2002. Interferon-γ is required for activation-induced death of t lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 196:999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramana, C.V., N. Grammatikakis, M. Chernov, H. Nguyen, K.C. Goh, B.R. Williams, and G.R. Stark. 2000. Regulation of c-myc expression by IFN-gamma through Stat1-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 19:263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badovinac, V.P., A.R. Tvinnereim, and J.T. Harty. 2000. Regulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell homeostasis by perforin and interferon-γ. Science. 290:1354–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton, D.K., L. Haynes, C.Q. Chu, S.L. Swain, and S. Wittmer. 2000. Interferon gamma eliminates responding CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection by inducing apoptosis of activated CD4 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 192:117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pernis, A., S. Gupta, K.J. Gollob, E. Garfein, R.L. Coffman, C. Schindler, and P. Rothman. 1995. Lack of interferon γ receptor β chain and the prevention of interferon γ signaling in TH1 cells. Science. 269:245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bach, E.A., S.J. Szabo, A.S. Dighe, A. Ashkenazi, M. Aguet, K.M. Murphy, and R.D. Schreiber. 1995. Ligand-induced autoregulation of IFN-γ receptor β chain expression in T helper cell subsets. Science. 270:1215–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez, F., S. Harkins, M.K. Slifka, and J.L. Whitton. 2002. Immunodominance in virus-induced CD8+ T cell responses is dramatically modified by DNA immunization, and is regulated by interferon-γ. J. Virol. 76:4251–4259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, F., J.L. Whitton, and M.K. Slifka. 2004. The rapidity with which virus-specific CD8+ T cells initiate IFNγ synthesis increases markedly over the course of infection, and correlates with immunodominance. J. Immunol. 173:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tishon, A., H. Lewicki, G.F. Rall, M.G. von Herrath, and M.B.A. Oldstone. 1995. An essential role for type 1 interferon-γ in terminating persistent viral infection. Virology. 212:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, S., W. Hendriks, A. Althage, S. Hemmi, H. Bluethmann, R. Kamijo, J. Vilcek, R.M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1993. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-γ receptor. Science. 259:1742–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skrenta, H., Y. Yang, S. Pestka, and C.G. Fathman. 2000. Ligand-independent down-regulation of IFN-γ receptor 1 following TCR engagement. J. Immunol. 164:3506–3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cousens, L.P., R. Peterson, S. Hsu, A. Dorner, J.D. Altman, R. Ahmed, and C.A. Biron. 1999. Two roads diverged: interferon α/β- and interleukin 12-mediated pathways in promoting T cell interferon γ responses during viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 189:1315–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mempel, T.R., S.E. Henrickson, and U.H. von Andrian. 2004. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 427:154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grayson, J.M., A.J. Zajac, J.D. Altman, and R. Ahmed. 2000. Cutting edge: increased expression of bcl-2 in antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 164:3950–3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaech, S.M., and R. Ahmed. 2001. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naive cells. Nat. Immunol. 2:415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Stipdonk, M.J., E.E. Lemmens, and S.P. Schoenberger. 2001. Naive CTLs require a single brief period of antigenic stimulation for clonal expansion and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2:423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercado, R., S. Vijh, S.E. Allen, K. Kerksiek, I.M. Pilip, and E.G.P. Am. 2000. Early programming of T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 165:6833–6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maldonado, R.A., D.J. Irvine, R. Schreiber, and L.H. Glimcher. 2004. A role for the immunological synapse in lineage commitment of CD4 lymphocytes. Nature. 431:527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaech, S.M., S. Hemby, E. Kersh, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 111:837–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohman, B.L., and R.M. Welsh. 1998. Apoptotic regulation of T cells and absence of immune deficiency in virus-infected gamma interferon receptor knockout mice. J. Virol. 72:7815–7821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blattman, J.N., J.M. Grayson, E.J. Wherry, S.M. Kaech, K.A. Smith, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat. Med. 9:540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Parijs, L., Y. Refaeli, J.D. Lord, B.H. Nelson, A.K. Abbas, and D. Baltimore. 1999. Uncoupling IL-2 signals that regulate T cell proliferation, survival, and Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death. Immunity. 11:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tough, D.F., P. Borrow, and J. Sprent. 1996. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 272:1947–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNally, J.M., C.C. Zarozinski, M.Y. Lin, M.A. Brehm, H.D. Chen, and R.M. Welsh. 2001. Attrition of bystander CD8 T cells during virus-induced T-cell and interferon responses. J. Virol. 75:5965–5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernabei, P., E.M. Coccia, L. Rigamonti, M. Bosticardo, G. Forni, S. Pestka, C.D. Krause, A. Battistini, and F. Novelli. 2001. Interferon-γ receptor 2 expression as the deciding factor in human T, B, and myeloid cell proliferation or death. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70:950–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panitch, H.S., R.L. Hirsch, A.S. Haley, and K.P. Johnson. 1987. Exacerbations of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with gamma interferon. Lancet. 1:893–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]