Abstract

The ribonuclease III enzyme Dicer is essential for the processing of micro-RNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from double-stranded RNA precursors. miRNAs and siRNAs regulate chromatin structure, gene transcription, mRNA stability, and translation in a wide range of organisms. To provide a model system to explore the role of Dicer-generated RNAs in the differentiation of mammalian cells in vivo, we have generated a conditional Dicer allele. Deletion of Dicer at an early stage of T cell development compromised the survival of αβ lineage cells, whereas the numbers of γδ-expressing thymocytes were not affected. In developing thymocytes, Dicer was not required for the maintenance of transcriptional silencing at pericentromeric satellite sequences (constitutive heterochromatin), the maintenance of DNA methylation and X chromosome inactivation in female cells (facultative heterochromatin), and the stable shutdown of a developmentally regulated gene (developmentally regulated gene silencing). Most remarkably, given that one third of mammalian mRNAs are putative miRNA targets, Dicer seems to be dispensable for CD4/8 lineage commitment, a process in which epigenetic regulation of lineage choice has been well documented. Thus, although Dicer seems to be critical for the development of the early embryo, it may have limited impact on the implementation of some lineage-specific gene expression programs.

Small RNA molecules have important functions in gene regulation, chromatin structure, and chromosome maintenance in a wide range of organisms (1–7). The RNase III enzyme Dicer is required for the processing of short (21–22 nucleotides) micro-RNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from double-stranded RNA precursors. Dicer-generated RNAs trigger the destruction of complementary mRNAs or prevent their translation, and may recruit chromatin modifiers to sites of repetitive DNA sequences or to specific promoters (1–7). Each of several hundred miRNA genes may regulate multiple transcripts, so that one in three protein-coding transcripts could be subject to miRNA regulation (8, 9).

Defining the role of Dicer-generated RNAs in mammalian development is complicated by embryonic lethality of constitutive Dicer knockouts in mice (10, 11). Mouse embryonic stem cells that are selected for viability in the absence of Dicer fail to differentiate in vitro and do not contribute to mouse development in vivo (6); this may point to a role for siRNAs and miRNAs in the regulation of gene expression or differentiation.

An involvement of miRNAs in hematopoiesis is suggested by the position of miRNA genes near translocation breakpoints or deletions in human leukemias (12–14). Several miRNAs are restricted to hematopoietic cells and the enforced expression of miR-181 in progenitor cells favors the development of B over T cells; this indicates that miRNAs may contribute to the control of hematopoiesis (15).

Lymphocytes may be of use to investigate Dicer functions, because in contrast with cell lines and early embryos, lymphocytes spend extended periods in a resting state. Moreover, their differentiation is well-studied. Early T cell precursors, double negative (DN) for CD4 and CD8, proliferate while they progress through the CD44+CD25− (DN1) and the CD44+CD25+ (DN2) stages to the CD44−CD25+ (DN3) stage. Precursors of the TCRγδ lineage diverge at the DN stage (16). DN3 cells that are committed to the TCRαβ lineage remain in a nonproliferating (G1) state until productive TCR-β rearrangement occurs and preTCR signals trigger reentry into the cell cycle, loss of CD25 (DN4), and the acquisition of CD4 and CD8. Cell division that is driven by the preTCR stops soon after thymocytes become CD4 CD8 double positive (DP), and subsequent differentiation occurs without obligatory proliferation (16). DP thymocytes are bipotential progenitors of CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. In response to TCR engagement, DP thymocytes elevate the expression of the activation markers, CD5 and CD69; transiently down-regulate the lineage markers, CD4 and CD8; and silence genes that are involved in TCR rearrangement, including Rag and Tdt. They initiate lineage-specific gene expression programs and differentiate via a series of intermediates (DPlo, CD4+8lo) into CD4 or CD8 single positive (SP) thymocytes (16). We have constructed a conditional allele and used lineage-specific Cre expression to delete Dicer during T cell development in the thymus.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dicer deletion in thymocytes

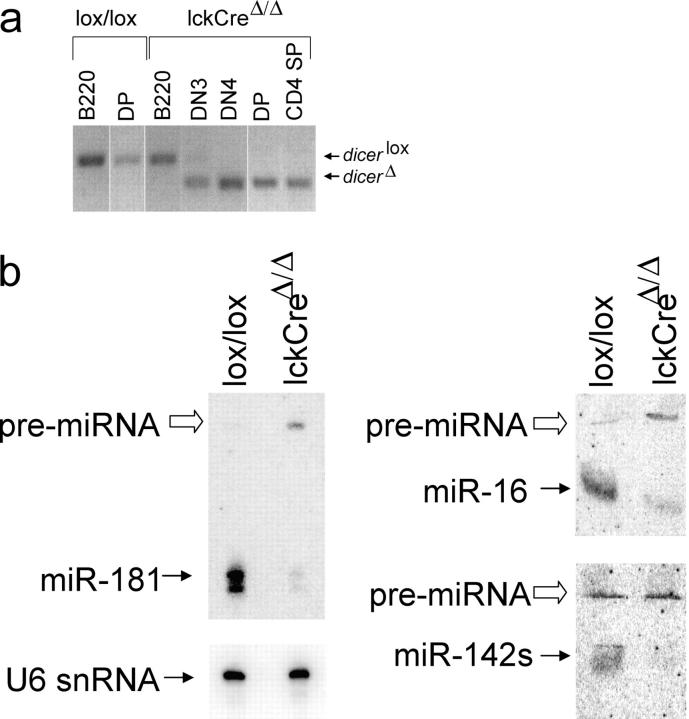

To explore the role of Dicer in T lymphocyte development, we flanked an essential RNaseIII domain (exons 20 and 21) with loxP sites to create Dicer lox (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20050572/DC1). Mice that were homozygous for this allele were viable, fertile, and had no obvious defects in lymphocyte development. When we introduced an lckCre transgene—which is active from the earliest stages of T cell development (17)—there was substantial deletion of Dicer by the CD44−CD25+ (DN3) stage and no undeleted alleles were detectable in CD44−CD25− (DN4), CD4+8+ DP, or CD4 SP cells (Fig. 1 a). Although designed primarily to interfere with function rather than expression, RT-PCR analysis showed that deletion of exons 20 and 21 also reduced steady-state Dicer mRNA levels (Fig. S1). Northern blotting showed that the abundance of several mature miRNAs was reduced substantially in LckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes. miR-181 was depleted 17- and 13-fold after normalization to U6 small nuclear RNA in total and DP lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes, respectively, whereas the unprocessed Dicer substrate, pre-miRNA, accumulated (Fig. 1 b). Mature miR-16 and miR-142s were depleted 6- and 20-fold, respectively (Fig. 1 b); this indicates that exon 20/21 deletion resulted in functional Dicer deficiency.

Figure 1.

Loss of Dicer activity. (a) Genomic PCR shows the Dicer lox allele in Dicer lox/lox B220+ lymph node B cells and DP thymocytes and in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ B220+ lymph node B cells. Only the Dicer Δ allele is seen in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes from the DN4 stage onwards. White lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out. (b) Loss of mature miR-181, miR-16, and miR-142s and accumulation of miR-181 and miR-16 pre-miRNAs in lckCre DicerΔ/Δ thymocytes. U6 small nuclear (snRNA) is a loading control.

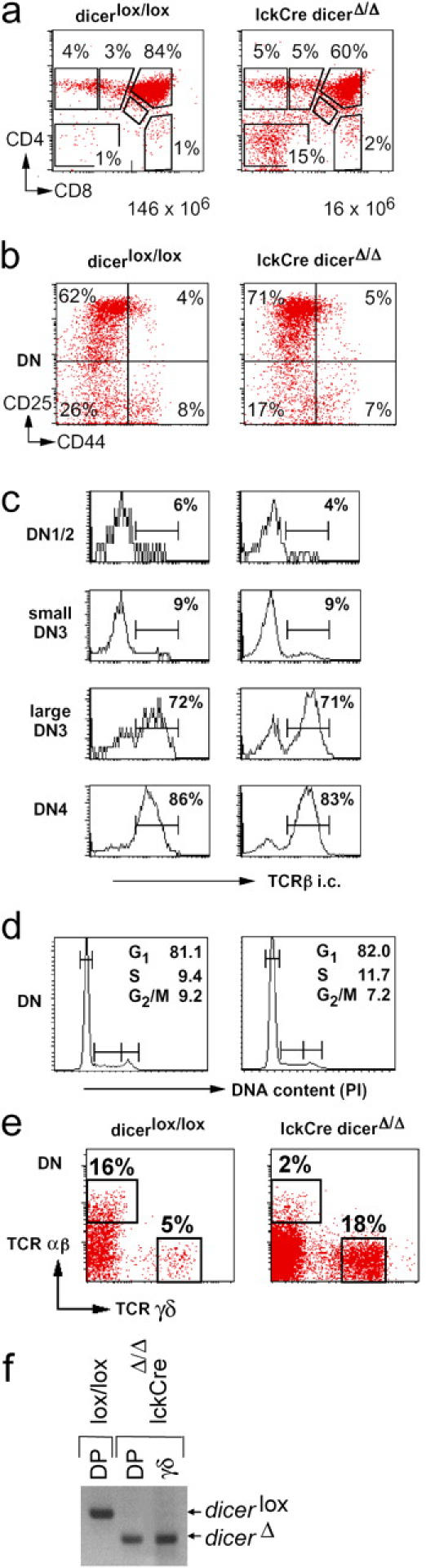

Cell numbers in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymi were reduced nearly 10-fold relative to Dicer lox/lox (16 ± 7 × 106, n = 9, versus 146 ± 43 × 106, n = 8; Fig. 2 a). There were normal numbers of DN cells in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymi (2.6 ± 0.8 × 106 compared with 3.2 ± 0.6 × 106 in Dicerlox/lox, n = 9), so that their percentage was elevated (Fig. 2 a). The distribution of CD44/25 subsets gave no indication of a developmental block (10 ± 2% DN1, 4 ± 1% DN2, 46 ± 11% DN3, 39 ± 9% DN4 in Dicer lox/lox; 10 ± 2% DN1, 6 ± 1% DN2, 57 ± 9% DN3, 28 ± 6% DN4 in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ; Fig. 2 b). In the αβ T cell lineage, progression from DN3 to DN4 and the DP stage requires the productive rearrangement and expression of TCRβ (16). Expression of TCRβ was not compromised by Dicer deletion, and intracellular staining showed the expected increase in TCRβ expression between the small and the large DN3 stage (Fig. 2 c). Correspondingly, analysis of DNA content showed similar proportions of actively cycling Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DN thymocytes (Fig. 2 d).

Figure 2.

Reduced cellularity of lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymi, but no developmental block at the DN stage. (a) Thymocyte numbers and subset distribution defined by CD4 and CD8 expression in Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ littermates. The representation of thymocyte subsets and the total number of thymocytes are indicated. Note reduced cellularity in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymi. (b) Expression of CD44 and CD25 on DN cells indicates normal DN subset distribution in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes. (c) Intracellular staining of DN thymocyte subsets indicates normal TCR-β expression in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DN thymocytes. (d) DNA content as assessed by propidium iodide (PI) staining indicates that lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DN thymocytes proliferate normally. (e) TCR γδ-expressing cells are overrepresented in the absence of Dicer. (f) Genomic PCR shows that Dicer deletion is comparable, and virtually complete, in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ γδ-expressing thymocytes.

An unusually high percentage of lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes expressed TCRγδ (6.7 ± 2.7%, n = 4) compared with 0.4 ± 0.2% in Dicer lox/lox (n = 3), and γδ cells were prevalent in the DN compartment (Fig. 2 e). As in DP thymocytes, Dicer deletion was virtually complete in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ γδ cells (Fig. 2 f); however, in contrast to αβ cells, γδ cell numbers were not reduced in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymi (7.3 ± 1 × 105 per lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymus, n = 4; 5.7 ± 3 × 105 per Dicer lox/lox thymus, n = 3). This abundance of γδ cells might be explained, paradoxically, by the limited expansion of γδ relative to preTCR-expressing αβ precursors (16). Fewer cell divisions could mean preferential survival in the absence of Dicer. Alternatively, Dicer-dependent mechanisms may control αβ/γδ lineage choice directly. Deficient Notch/RBP-J signaling favors γδ relative to αβ cells (18, 19) and Notch signaling components are among predicted miRNA targets (9).

Increased susceptibility to cell death

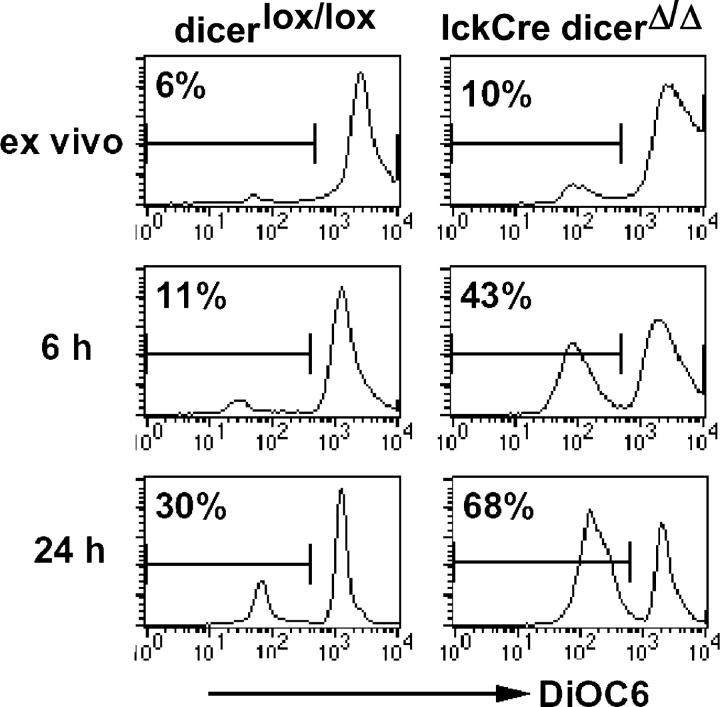

Because there was no indication for a developmental block at the DN stage, we looked at cell death as an alternative explanation for the reduced numbers of lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes. Ex vivo, few thymocytes stained with Annexin V (unpublished data) or showed reduced mitochondrial membrane potential as an early marker of apoptosis (20). In vitro culture revealed more dying lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes than controls (43% versus 11% at 6 h and 68% versus 30% after 24 h; Fig. 3). Dicer deficiency has been linked to heterochromatin defects (1, 5, 6) and centromere dysfunction in dividing cells (1, 5), which might result in checkpoint activation and/or missegregation of genetic material (1, 5). The generation of DP cells from the DN1/2 stage involves six to eight divisions (16). In contrast to lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ mice, CD4Cre Dicer Δ/Δ mice (where Cre is expressed slightly later; reference 17) have relatively normal thymocyte numbers (unpublished data); this suggests that the time or the number of cell divisions between the deletion of Dicer and the DP stage may affect thymocyte survival. Alternatively, Dicer-dependent RNAs might regulate survival directly (21).

Figure 3.

Increased cell death in the absence of Dicer. Thymocytes were stained for CD4, CD8, and DiOC6 as an indicator of mitochondrial membrane potential ex vivo or after culture. Histograms are gated on DP cells but not on light scatter.

Maintenance of constitutive and facultative heterochromatin

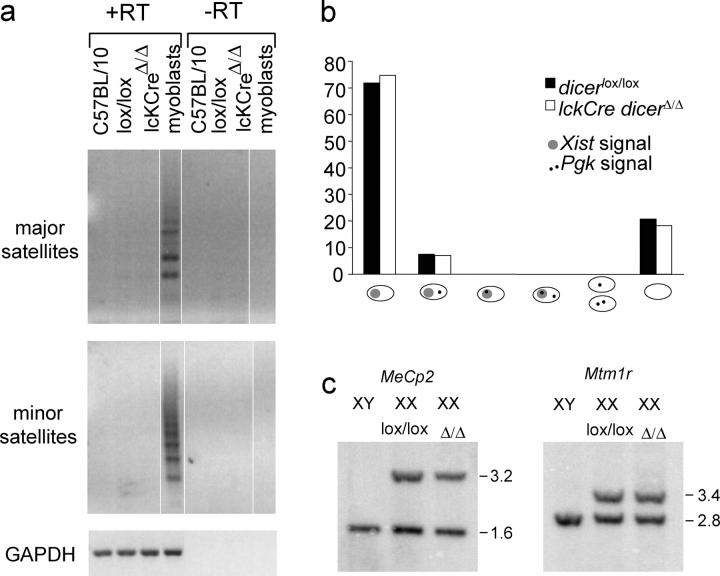

We used RT-PCR to evaluate heterochromatic silencing. Major and minor satellite transcripts were readily detectable in differentiating muscle cells, but not in control or Dicer deficient thymocytes (Fig. 4 a).

Figure 4.

Transcriptional repression of centromeric satellite repeats and features of facultative heterochromatin are maintained in the absence of Dicer. (a) RT-PCR (controlled by GAPDH) did not detect transcripts of major and minor satellite repeat in wild-type (C57BL/10), Dicer lox/lox or lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes, but did in differentiating myoblasts. White lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out. (b) RNA FISH using Xist and Pgk probes of female (XX) control fibroblasts and Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP thymocytes (see Fig. S2) shows monoallelic, but not biallelic, expression of Pgk. Pgk signals did not overlap with Xist signals. (c) DNA from control XY cells and XX Dicer lox/lox or lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes digested with Xba1/Nru1 (MeCp2) or Xba1/Mlu1 (Mtm1r), and probed for MeCp2 and Mtm1r CpG islands. Upper bands correspond to the methylated (inactive X) allele and lower bands to the unmethylated (active X) allele.

The genome is subject to silencing during progressive lineage restriction (22) and the silent X chromosome in female cells provides a tractable model for facultative heterochromatin (23). We used RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to determine if the expression and localization of the noncoding RNA Xist, which is required for X inactivation (23), are affected in Dicer-deficient cells. In control XX somatic cells, Xist RNA highlights the territory of the inactive X chromosome in control Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP thymocytes (Fig. 4 b and Fig. S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20050572/DC1). We also assessed if there was reactivation of the X-linked Pgk-1 gene, which would result in the appearance of two foci per cell, or Pgk-1 foci within Xist domains. Although RNA FISH may not detect very low levels of expression, the results rule out substantial Pgk-1 reactivation in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP cells (n = 170) relative to controls (n = 135; Fig. 4 b).

Multiple, partially redundant mechanisms maintain X inactivation; disruption of only one of these may not be sufficient for X reactivation. Based on recent data that siRNAs can direct deoxycytosine-deoxyguanosine (CpG) island methylation (3, 4), we were interested in DNA methylation of X-linked CpG islands, which normally are unmethylated on active X chromosomes and fully methylated on the inactive X (unpublished data). Using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes to examine MeCp2 and Mtm1 CpG islands, we observed approximately equal levels of uncut (methylated) and cut (unmethylated) bands which corresponded to alleles on the active and the inactive X, respectively, in female control Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocyte DNA (Fig. 4 c). Hence, at this level of analysis, the maintenance of constitutive and facultative heterochromatin seemed to be unperturbed in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes.

CD4/CD8 lineage choice and differentiation

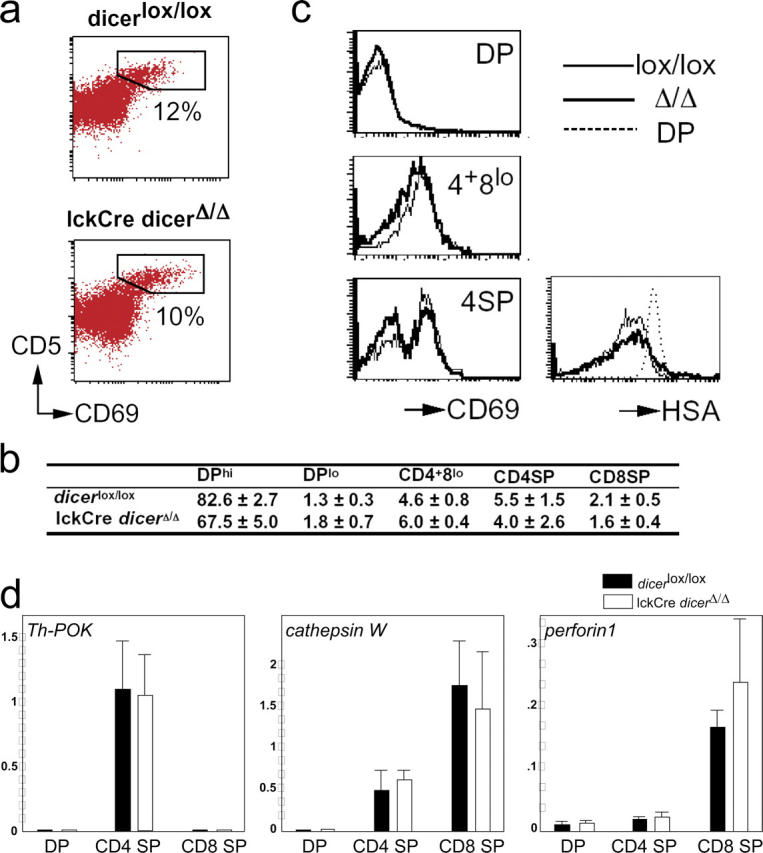

Given the role of siRNAs and miRNAs in the regulation of gene expression and differentiation in other systems (1–7), it was of interest to determine how the loss of Dicer at the DN stage would affect the sequence of events during the transition from the DP to the SP stage of thymocyte development. Despite the reduced cellularity of the DP thymocyte compartment, the frequency of CD5hi and CD69+ cells was similar to controls; this indicates that a normal proportion of DP thymocytes was recruited into the thymic selection process (Fig. 5 a and reference 24). DPlo and CD4+8lo cells in transit to the SP populations and CD4 and CD8 SP cells were present at the expected frequencies (Figs. 2 a and 5 b). As part of their intrathymic maturation, CD4SP cells gradually down-regulate CD69 and CD24 (HSA; reference 16); this was not perturbed in lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes (Fig. 5 c).

Figure 5.

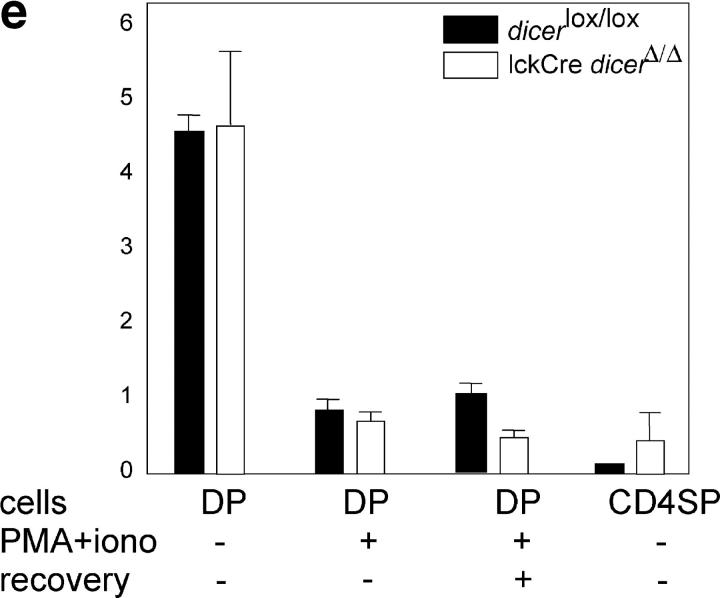

CD4/CD8 lineage choice, lineage-appropriate gene expression, and developmentally regulated gene silencing in the absence of Dicer. Similar percentages of Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes up-regulate CD5 and CD69 at the DP stage (a) and form transitional subsets that are defined by CD4 and CD8 expression (b, mean ± SD, n = 6, see Fig. 2 a), and the expression of CD69 and HSA follows the expected developmental sequence (c). (d) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of CD4 and CD8 lineage-specific transcripts in sorted DP, CD4 SP, and mature (TCRhi) CD8 SP thymocytes normalized to UBC and YWHAZ control loci (mean ± SD, n = 3). (e) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Tdt expression ex vivo, 10 h after phorbol ester and ionomycin stimulation (PMA+iono), or 10-h stimulation and 10-h recovery in fresh medium (normalized to UBC and YWHAZ, mean ± SEM, n = 2).

In addition to the mutually exclusive expression of CD4 and CD8, mature thymocyte subsets differentially express “signature” genes, such as Ph-POK in the CD4 lineage and perforin and cathepsin W in the CD8 lineage (25, 26). Quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5 d) confirmed the appropriate expression of Ph-POK in CD4 but not in DP or CD8 SP lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes (25). Perforin and cathepsin W were expressed more highly in CD8 SP than in DP or CD4 SP thymocytes (26).

Developmentally regulated gene silencing

Owing to TCR specificity and other constraints, only a relatively small proportion of DP thymocytes differentiate from the DP to SP stage, even in wild-type mice (16, 24). To address whether the entire population of lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP thymocytes is able to undergo early differentiation events, we used an in vitro differentiation model in which DP thymocytes that are exposed to surrogate TCR signals (phorbol ester and calcium ionophore) silence Tdt expression (27, 28). The great majority of control Dicer lox/lox and lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP cells up-regulated CD5 and CD69 (not depicted); Tdt RNA expression declined to levels that were comparable with Dicer lox/lox controls (Fig. 5 e). This indicates that most, if not all, lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP cells were competent to down-regulate Tdt.

Initially, Tdt silencing is reversible, so that Tdt is reexpressed when TCR stimulation ceases (28). Only after several hours of continued signaling does Tdt silencing become a stable trait, which in normal thymocytes—but not in certain thymoma cell lines—persists even after removal of the stimulus (28). To address whether lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP thymocytes silence Tdt in a stable fashion, we initiated silencing by culture with phorbol ester and calcium ionophore, removed the stimulus, and recultured the cells for 10 h. Neither Dicer lox/lox nor lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ DP cells reexpressed Tdt; this indicates that Dicer-deficient cells are competent to establish stable gene silencing (Fig. 5 e). Developmentally regulated silencing of Tdt during the in vivo differentiation of DP thymocytes also was intact, because lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ and Dicer lox/lox CD4 SP thymocytes showed equivalent levels of Tdt down-regulation ex vivo (Fig. 5 e).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a requirement for Dicer in the generation and survival of normal numbers of αβ T cells. In contrast, Dicer apparently is not essential for the maintenance of transcriptional silencing of pericentromeric satellite sequences (constitutive heterochromatin), the maintenance of X chromosome inactivation and cytosine methylation in female cells (facultative heterochromatin), or the stable shutdown of a developmental stage-specific gene (developmentally regulated gene silencing) in the T cell lineage. These results do not question the general involvement of Dicer in the maintenance of heterochromatin (1, 5), but suggest that Dicer may not be required continually for heterochromatin maintenance in thymocytes. We have not investigated centromere structure and function directly, but our RT-PCR analysis of major and minor satellite transcripts gives no indication of transcriptional derepression. It is likely that epigenetic marks, such as CpG methylation—once established during development—allow for Dicer-independent maintenance of heterochromatin. Current estimates suggest that as many as one in three mRNAs are targets of miRNA regulation (9). Given the important roles that are ascribed to small, double-stranded RNAs in the regulation of gene expression and differentiation (1–7), it is remarkable that Dicer appears to be dispensable for CD4/8 lineage commitment and the implementation of lineage-specific gene expression programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Dicer targeting vector.

Details of the targeting vector are shown in Fig. S1. The vector was electroporated into ES cells and homologous recombination was assayed by the Southern strategy that is outlined in Fig. 1. One of several correctly targeted ES cell clones (clone 96.2) was used for the production of chimeric mice by blastocyst injection.

Mouse strains, cell sorting, and culture.

Animal work was performed according the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, UK. Dicer lox/lox mice were crossed with LckCre transgenic mice (17) to generate lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ mice. Thymocytes were stained, analyzed, and sorted by flow cytometry as described previously (24). Where indicated, thymocytes were incubated with 40 nM DiOC6 (Molecular Probes) for 10 min at 37°C as described previously (20). To down-regulate Tdt expression, DP thymocytes were cultured with 7.5 ng/ml PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 180 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously (28).

RNA FISH.

RNA FISH for Xist and Pgk was done as described previously (29) with minor modifications. FACS-sorted DP thymocytes were prefixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min on ice. 100 μl of cell suspension (∼6 × 104) was cytospun onto glass slides, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in ice-cold cytoskeletal buffer for 5 min, and postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min on ice. Slides were stored in 70% ethanol.

CpG methylation analysis.

DNA from control XY cells, XX Dicer lox/lox, and XX lckCre Dicer Δ/Δ thymocytes was digested with XbaI and NruI (MeCp2) or XbaI and MluI (MtmIr), electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels, Southern blotted, and hybridized using standard procedures.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using RNAbee (Tel-Test) and reverse transcribed. Real-time PCR analysis was performed on a OpticonDNA engine (MJ Research Inc.) and normalized as described previously (30). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available on request.

Online supplemental material

Figs. S1 and S2 desribe the construction of the targeted Dicer alelle and depict RNA FISH data on Xist expression. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20050572/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. C.-Z. Chen for advice on miRNA northerns, R. Terranova for cDNAs and help with the detection of centromeric transcripts, and Z. Webster and J. Mardon-Srivastava for help with ES cells and cell sorting.

This research was supported by the Medical Research Council, UK, and the National Institutes of Health, USA.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Volpe, T.A., C. Kidner, I.M. Hall, G. Teng, S.I. Grewal, and R.A. Martienssen. 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 297:1833–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel, D.P. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawasaki, H., and K. Taira. 2004. Induction of DNA methylation and gene silencing by short interfering RNAs in human cells. Nature. 431:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris, K.V., S.W. Chan, S.E. Jacobsen, and D.J. Looney. 2004. Small interfering RNA-induced transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Science. 305:1289–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukagawa, T., M. Nogami, M. Yoshikawa, M. Ikeno, T. Okazaki, Y. Takami, T. Nakayama, and M. Oshimura. 2004. Dicer is essential for formation of the heterochromatin structure in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanellopoulou, C., S.A. Muljo, A.L. Kung, S. Ganesan, R. Drapkin, T. Jenuwein, D.M. Livingston, and K. Rajewsky. 2005. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 19:489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuwabara, T., J. Hsieh, K. Nakashima, K. Taira, and F.H. Gage. 2004. A small modulatory dsRNA specifies the fate of adult neural stem cells. Cell. 116:779–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis, B.P., C.B. Burge, and D.P. Bartel. 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 120:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim, L.P., N.C. Lau, P. Garrett-Engele, A. Grimson, J.M. Schelter, J. Castle, D.P. Bartel, P.S. Linsley, and J.M. Johnson. 2005. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 433:769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein, E., S.Y. Kim, M.A. Carmell, E.P. Murchison, H. Alcorn, M.Z. Li, A.A. Mills, S.J. Elledge, K.V. Anderson, and G.J. Hannon. 2003. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat. Genet. 35:215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang, W.J., D. Yang, S. Na, G. Sandusky, Q. Zhang, and G. Zhao. 2004. Dicer is required for embryonic angiogenesis during mouse development. J. Biol. Chem. 280:9330–9335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calin, G.A., C.D. Dumitru, M. Shimizu, R. Bichi, S. Zupo, E. Noch, H. Aldler, S. Rattan, M. Keating, K. Rai, et al. 2002. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:15524–15529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauwerky, C.E., K. Huebner, M. Isobe, P.C. Nowell, and C.M. Croce. 1989. Activation of MYC in a masked t(8;17) translocation results in an aggressive B-cell leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:8867–8871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagos-Quintana, M., R. Rauhut, W. Lendeckel, and T. Tuschl. 2001. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 294:853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, C.Z., L. Li, H.F. Lodish, and D.P. Bartel. 2004. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 303:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisielow, P., and H. von Boehmer. 1995. Development and selection of T cells: facts and puzzles. Adv. Immunol. 58:87–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, P.P., D.R. Fitzpatrick, C. Beard, H.K. Jessup, S. Lehar, K.W. Makar, M. Perez-Melgosa, M.T. Sweetser, M.S. Schlissel, S. Nguyen, et al. 2001. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 15:763–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanigaki, K., M. Tsuji, N. Yamamoto, H. Han, J. Tsukada, H. Inoue, M. Kubo, and T. Honjo. 2004. Regulation of αβ/γδ T cell lineage commitment and peripheral T cell responses by Notch/RBP-J signalling. Immunity. 20:611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washburn, T., E. Schweighoffer, T. Gridley, D. Chang, B.J. Fowlkes, D. Cado, and E. Robey. 1997. Notch activity influences the alphabeta versus gammadelta T cell lineage decision. Cell. 88:833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamzami, N., P. Marchetti, M. Castedo, D. Decaudin, A. Macho, T. Hirsch, S.A. Susin, P.X. Petit, B. Mignotte, and G. Kroemer. 1995. Sequential reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and generation of reactive oxygen species in early programmed cell death. J. Exp. Med. 182:367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu, P., M. Guo, and B.A. Hay. 2004. MicroRNAs and the regulation of cell death. Trends Genet. 20:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher, A.G. 2002. Cellular identity and lineage choice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:977–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brockdorf, N. 1998. The role of Xist in X-inactivation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8:328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merkenschlager, M., D. Graf, M. Lovatt, U. Bommhardt, R. Zamoyska, and A.G. Fisher. 1997. How many thymocytes audition for selection? J. Exp. Med. 186:1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He, X., X. He, V.P. Dave, Y. Zhang, X. Hua, E. Nicolas, W. Xu, B.A. Roe, and D.J. Kappes. 2005. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature. 433:826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, X., and R. Bosselut. 2004. Duration of TCR signaling controls CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 5:280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown, K.E., J. Baxter, D. Graf, M. Merkenschlager, and A.G. Fisher. 1999. Dynamic repositioning of genes in the nucleus of lymphocytes preparing for cell division. Mol. Cell. 3:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su, R.-C., K.E. Brown, S. Saaber, A.G. Fisher, M. Merkenschlager, and S.T. Smale. 2004. Assembly of silent chromatin at a developmentally regulated gene. Nat. Genet. 36:502–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heard, E., F. Mongelard, D. Arnaud, and P. Avner. 1999. Xist yeast artificial chromosome transgenes function as X-inactivation centers only in multicopy arrays and not as single copies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3156–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandesompele, J., K. De Preter, F. Pattyn, B. Poppe, N. Van Roy, A. De Paepe, and F. Speleman. 2002. Accurate normalisation of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol, 3:7. Epub 2002 Jun 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]