Abstract

Brains from subjects who have Alzheimer's disease (AD) express inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). We tested the hypothesis that iNOS contributes to AD pathogenesis. Immunoreactive iNOS was detected in brains of mice with AD-like disease resulting from transgenic expression of mutant human β-amyloid precursor protein (hAPP) and presenilin-1 (hPS1). We bred hAPP-, hPS1-double transgenic mice to be iNOS+/+ or iNOS−/−, and compared them with a congenic WT strain. Deficiency of iNOS substantially protected the AD-like mice from premature mortality, cerebral plaque formation, increased β-amyloid levels, protein tyrosine nitration, astrocytosis, and microgliosis. Thus, iNOS seems to be a major instigator of β-amyloid deposition and disease progression. Inhibition of iNOS may be a therapeutic option in AD.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a chronic degenerative and inflammatory brain disorder that leads to neuronal dysfunction and loss that are linked to accumulation of fragments (Aβ[1–42/43]) of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). A leading possibility to explain how Aβ accumulation leads to neurotoxicity is that Aβ triggers oxidative and/or nitrosative injury. Fibrillogenic Aβ elicits the production of reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNIs) and reactive oxygen intermediates from microglia, astrocytes, neurons, and monocytes, alone or synergistically with cytokines, in vitro and when injected into the brain, in part by way of induction of the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; NOS2) (1–3). AD lesions display biochemical and histochemical hallmarks of oxidative and nitrosative injury, including nitration of protein tyrosine residues (4–9), which can report the vicinal production of peroxynitrite from NO and superoxide. However, a functionally important source of AD-associated oxidative or nitrosative brain injury has not been identified that is a plausible target for pharmacologic inhibition.

In 1996, iNOS was identified in AD lesions (10). Collectively, that report and seven confirmatory studies identified iNOS immunoreactivity in neurons (7, 8, 10–12) and astrocytes (7, 12–14) in brains of 75 patients who had AD, but at far lower incidence, extent, and intensity in brains from age-matched controls. Although NOS1 (neuronal NOS) and NOS3 (endothelial NOS) are expressed constitutively in normal brain, widespread expression of iNOS in the central nervous system is pathologic, and has been observed in multiple sclerosis (15), HIV-associated dementia (16), stroke (17), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (18), and Parkinson's disease (19). Because of its independence of elevated intracellular Ca2+ (20), iNOS catalyzes a high-output pathway of NO production (21) that is capable of causing neuronal damage and death (16). Multiple mechanisms of NO-dependent cytotoxicity have been identified. For example, inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain by RNI (22) increases mitochondrial production of superoxide anion, and spurs formation of peroxynitrite, which can exacerbate mitochondrial damage (23). RNI can inhibit proteasomal degradation pathways (24), and perhaps contribute to the markedly decreased proteasome function that was documented in affected regions of brains from patients who had AD (25). Decreased proteasome function is likely to promote further accumulation of Aβ and advanced glycation products, which leads to increased induction of iNOS (13). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that inhibition of iNOS might slow the progression of neuronal damage in individuals in whom levels of intracerebral Aβ are elevated. To test the foregoing hypothesis, we used a genetic approach by breeding disrupted iNOS alleles into mice transgenic for mutant human genes associated with AD.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of strains

First, we backcrossed the original iNOS−/− C57BL/6×129 mice (26) to C57BL/6 for six generations. Descendants of brother–sister matings of the latter mice were crossed with the SJL strain, and their progeny were interbred to derive iNOS−/− C57BL/6×SJL mice. This step was based on evidence that that modifier genes from the SJL background were critical to avoid premature mortality in C57BL/6 mice bearing a mutant (K670N, M671L) human APP (hAPP) transgene (27). We bred the iNOS−/− C57BL/6×SJL mice with a strain called Tg2576, in which a hamster prion promoter drives the K670N, M671L APP transgene in the C57Bl/6×SJL background (28), and with transgenics in which the Thy1 promoter drives human presenilin–1 (hPS1) with the A246E mutation in the C57Bl/6×SJL background (29). We interbred the progeny to establish three C57BL/6×SJL sublines from littermates: (a) WT mice (iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0); (b) mice with WT iNOS alleles and the APP and PS1 transgenes, each of which was inherited from only one parent so as to avoid overdose (iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0); and (c) mice with disrupted iNOS alleles and the APP and PS1 transgenes (iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0). Genotypes were determined in all 3,691 mice that were required to generate and populate the experimental cohorts, and were confirmed in all mice used in the study after the last observation on each individual was recorded.

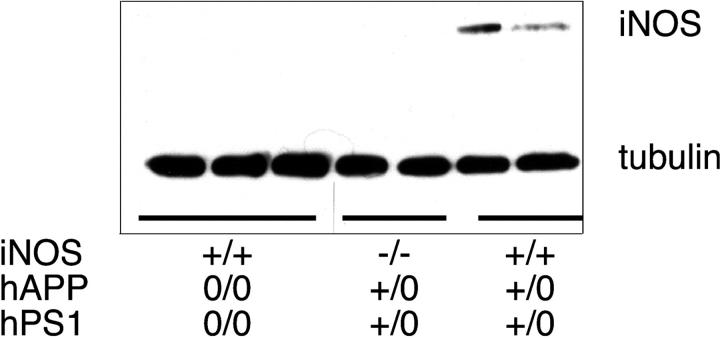

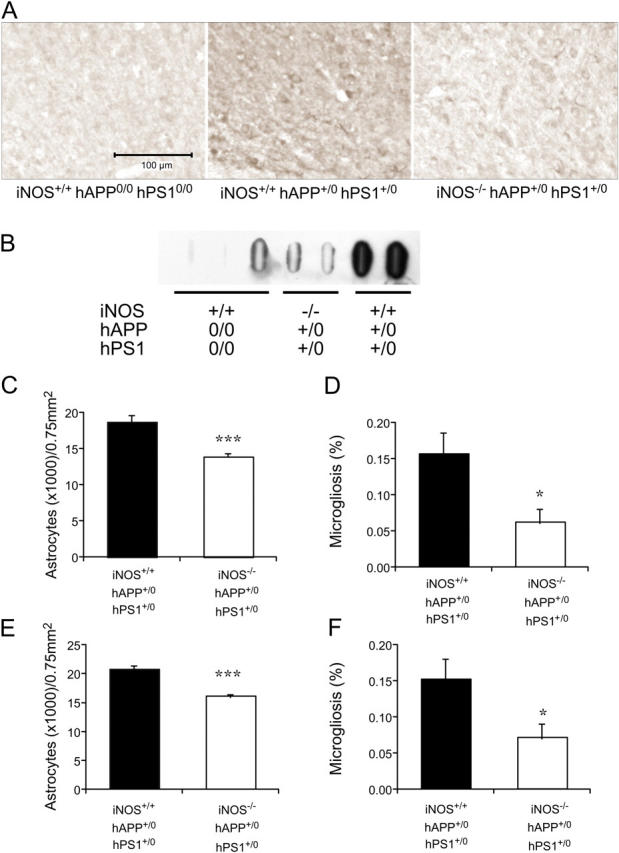

Anti-iNOS immunoblot detected the 130-kD iNOS protein in the brains of the new subline of double-transgenic mice with AD-like disease and WT iNOS alleles. The enzyme was not detected in brains of mice with AD-like disease whose iNOS alleles were disrupted, or in brains of mice with WT iNOS alleles and no AD transgenes (Fig. 1). We also detected immunohistologic reactivity for iNOS in the brains of our double-transgenic mice and four other mouse models of AD (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051529/DC1). Our findings confirm and extend reports in which immunohistology, immunoblot, and enzyme assays identified iNOS in brains of Tg2576 mice (28) and mice bearing the K670N, M671L human APP transgene driven by the Thy1 promoter in the C57BL/6 background (30).

Figure 1.

Expression of iNOS in brains of 60- to 64-wk-old mice with or without AD-related transgenes, as judged by immunoblot. Each lane is from a separate mouse of the genotypes indicated. Tubulin was immunostained as a loading control.

Impact of iNOS on AD transgene-dependent mortality

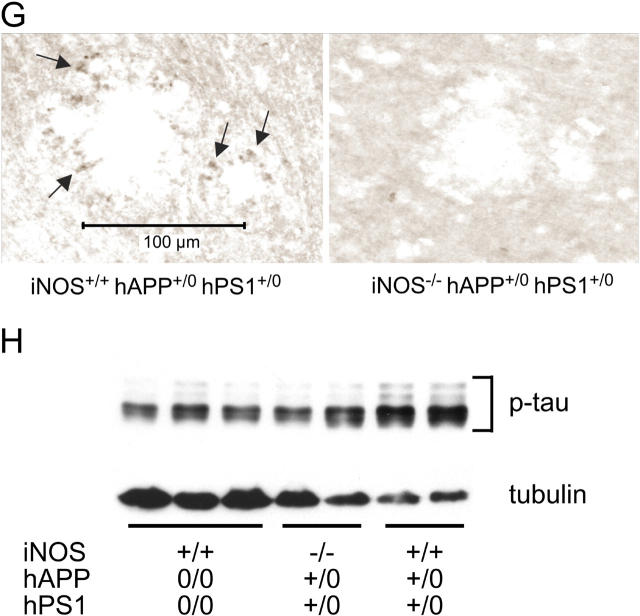

Comparison of the fate of the three congenic sublines allowed us to test the hypothesis that iNOS exacerbates AD. Mice with the AD-related transgenes and WT iNOS alleles died much earlier than did the WT congenic subline. Deficiency of iNOS exerted a marked protective effect against AD-related mortality, and extended the time at which 75% of the cohort remained alive from 143 d for iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice to 315 d for iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice—a 220% increase (P < 0.0001, logrank test) (Fig. 2 A). Even so, the iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice still died sooner than did congenic WT mice.

Figure 2.

Amelioration of early mortality of AD-transgenic mice by disruption of iNOS alleles without an impact on weight gain. (top, Survival) Individually genotyped mice (iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0, n = 133; iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 140; iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 112) were inspected 5 d per week throughout their lifetime, and their mortality was plotted as a function of age. Differences between any two curves were significant (P < 0.0001; logrank test). (middle) Weight gain in males (iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0, n = 43; iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 67; iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 48). (bottom) Weight gain in females (iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0, n = 41; iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 50; iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, n = 50).

Male (Fig. 2 B) and female (Fig. 2 C) AD-transgenic mice gained weight more slowly than did the WT mice (P < 0.0001, repeated measures ANOVA). However, iNOS alleles had no effect on weight gain, and therefore, iNOS was unlikely to hasten death by impairing feeding or drinking. Moreover, time-lapse video camera recordings every 15 or 30 s over 24-h periods, covering 327 h of life of individually housed mice aged 3–5 mo, were scored by an observer who was blind to mouse genotype. The video recordings revealed no differences in feeding or other behavior between AD-transgenic mice with and without intact iNOS alleles. Both strains tended to sleep less (4.5 ± 0.9 and 5.4 ± 1.3 episodes per day totaling 519 ± 50 and 581 ± 115 min, respectively) than did WT mice (8.8 ± 1.3 episodes totaling 624 ± 21 min; means ± SD) and both rarely hung from the cage lid, in contrast to WT mice. Necropsies of nine AD-transgenic mice with or without intact iNOS alleles revealed a distinct extracerebral pathology in each of four mice that was judged to be incidental (see supplemental material). Thus, the cause of premature mortality in the iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 strain was not established.

Impact of iNOS on AD transgene-dependent brain pathology

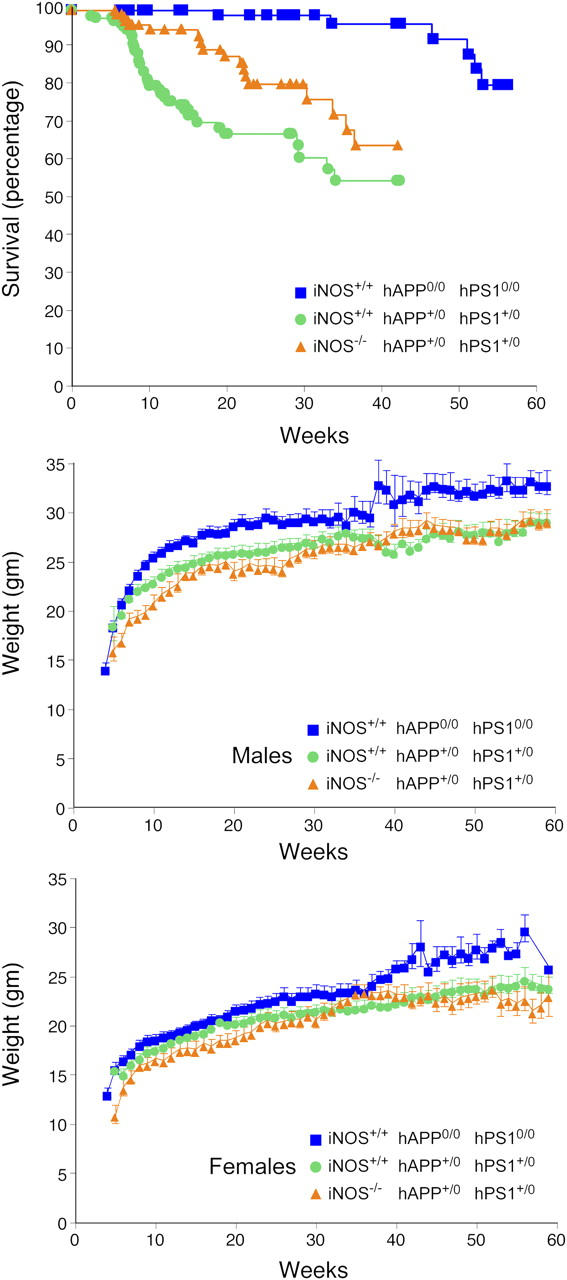

Cohorts of the three sublines were aged for 20, 40, and 60 wk. Brains from 10 mice per subline and time point were examined for histopathology. No abnormalities were observed in the WT controls. The double-transgenic mice had age-dependent accumulation of plaques in all areas examined: the cingulate, retrosplenial, and motor cortices and the hippocampus. Deficiency of iNOS had no effect on the accumulation of Aβ during the first 40 wk of life, but markedly inhibited further accumulation thereafter, so that plaque burden was reduced by 61% by week 60 (Fig. 3, A–E). Immunoblot (Fig. 3, F and G) and ELISA (Fig. 3 H) for Aβ were consistent with the immunohistologic findings; in immunoblot, Aβ signal intensity was reduced by 64% in the iNOS-deficient brains (P = 0.012, Student's t test), whereas in ELISA, Aβ reactivity was diminished by 43% (P = 0.04).

Figure 3.

Amelioration of late-stage plaque formation and Aβ deposition in AD-transgenic mice by disruption of iNOS alleles. (A) Representative sections from the neocortex and hippocampus of iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 and iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice immunostained with Aβ (1–42) antibody. (B–E) Plaque burden (percentage of area occupied by Aβ [1–42]-immunoreactive plaques) and plaque numbers per unit area as a function of age in cortex (B and C) and hippocampus (D and E). Means ± SEM for 10 mice per strain per time point. Statistically significant differences are marked (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.003). No immunoreactivity was detected in mice lacking AD transgenes. Solid green line, iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice. Dashed orange line, iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice. (F) Representative immunoblot for brain Aβ that was not extractable in physiologic saline or 0.5% Triton X-100, but was soluble in 6% SDS. Lane 1: iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice; lane 2: iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice; lane 3: iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0 mice. (G) Densitometry of four blots like that in F, each for different sets of mice, normalized to β-actin. The x axis sets to 1 the ratio of signal intensity for Aβ to that for β-actin in iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice (solid bar marked “+/+”); the corresponding ratios for iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice (hatched bar marked “−/−”) are given as of a proportion of the ratio for the “+/+” mice in each of the same four blots (mean ± SEM). (H) ELISA for Aβ in extracts prepared as in F. Aβ burden is indicated in μg/mg brain weight (mean ± SEM, n = 6) for the two strains with AD-related transgenes whose iNOS alleles are indicated as “+/+” (intact iNOS alleles, black bar) or “−/−“ (disrupted iNOS alleles, gray bar).

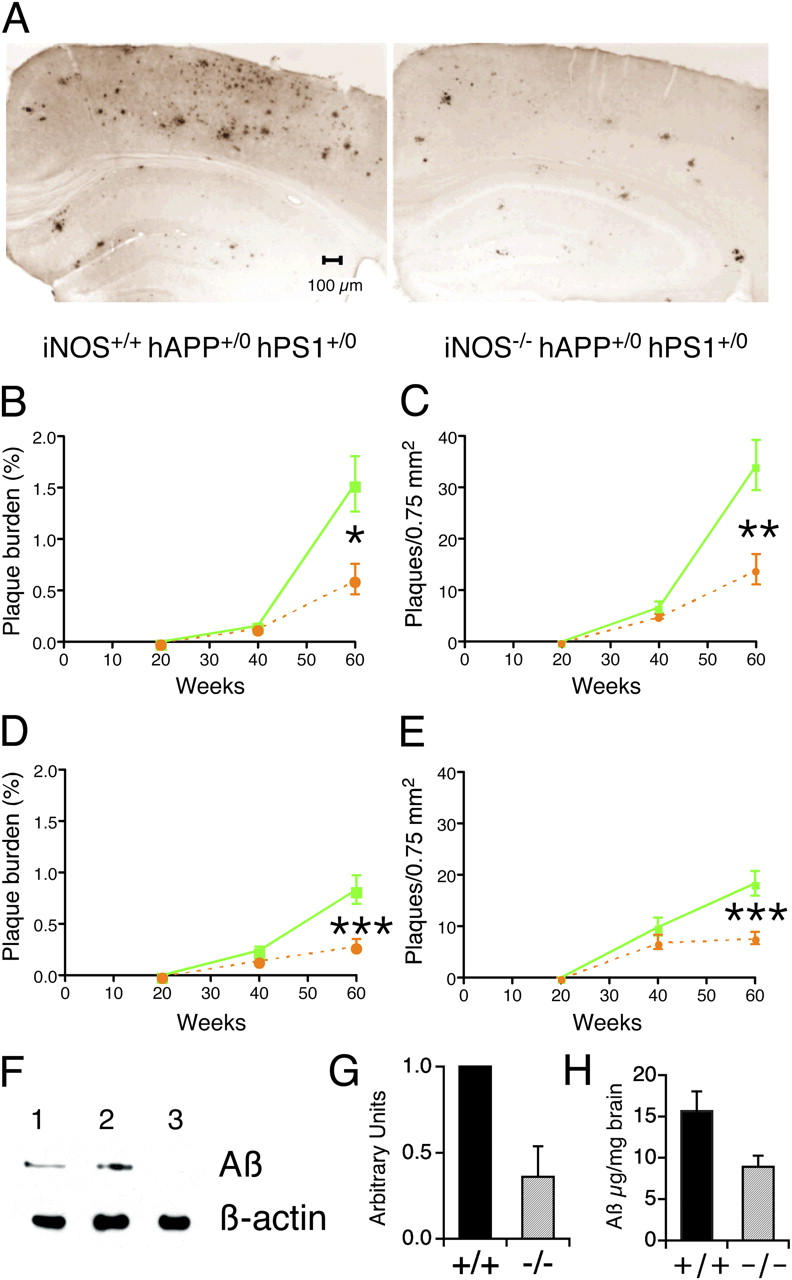

Deficiency of iNOS also reduced the extent of protein tyrosine nitration in the brains of the AD-transgenic mice markedly, as shown by immunostaining (Fig. 4 A) and slot-blot (Fig. 4 B) using two different antibodies. Further, iNOS deficiency afforded substantial protection against gliosis, as judged by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) staining for reactive astrocytes and CD40 staining for activated microglia (Fig. 4, B–E; Fig. S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051529/DC1). Finally, deficiency of iNOS led to a reduction in accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein around plaques as judged by immunostaining (Fig. 4 G) and immunoblot (Fig. 4 H). By densitometric analysis of immunoblots, the ratio of phospho-tau staining/tubulin staining used as a loading control averaged 0.7 ± 0.1 for WT mice, 1.2 ± 0.6 for mice with AD-related transgenes and disrupted iNOS alleles, and 2.7 ± 0.0 for mice with AD-related transgenes and intact iNOS alleles. Thus, iNOS deficiency seemed to reduce tau phosphorylation by 56%.

Figure 4.

Amelioration of late-stage nitrosative/oxidative injury, astrogliosis, microgliosis, and phospho-tau accumulation in AD-transgenic mice by disruption of iNOS alleles. (A) Nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in the cingulate cortex of iNOS+/+ hAPP0/0 hPS10/0, iNOS+/+ hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0, and iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice. (B) Nitrotyrosine immunoblot. Brain extract proteins (150 μg) were immobilized on a filter with a slot-blot apparatus and were immunoblotted with anti-nitrotyrosine mAb. (C–F) Reduction of GFAP staining indicative of astrocytosis (C and E) and of CD40 staining indicative of microgliosis (D and F) in the cortex (C and D) and hippocampus (E and F) of iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice. Statistically significant differences are marked (***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05). (G) Reduction of phospho-tau immunoreactivity around plaques in iNOS−/− hAPP+/0 hPS1+/0 mice. Arrows highlight positive staining. (H) Anti–phospho-tau (p-tau) immunoblot with anti-tubulin as a loading control. Each lane is from a separate mouse of the genotypes indicated. See text for quantitative analysis.

In summary, iNOS, the catalyst of high-output pathway of NO production (21), is expressed in human AD and in many mouse models of AD. Mice with AD-like disease that were unable to express iNOS genetically lived longer than did their iNOS-expressing counterparts, formed fewer plaques, had lower levels of brain Aβ, suffered less protein tyrosine nitration, accumulated less phosphorylated tau protein, and harbored fewer reactive astrocytes and microglia.

It was shown that fibrillogenic Aβ promotes expression of iNOS (1). However, the striking protective effect of iNOS deficiency on plaque formation and accumulation of Aβ deposits now suggests that iNOS is a major factor that furthers the accumulation of Aβ. Thus, iNOS and fibrillogenic Aβ each seem to promote the other's accumulation. Selective iNOS inhibitors that can enter the brain should be tested for their ability to slow the progression of AD-like disease in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genotyping.

Mice were bred and studied according to institutionally approved protocols. The strains that were constructed for this study have been deposited with the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers for distribution to other investigators (http://www.mmrrc.org/catalog/StrainCatalogSearchForm.jsp). All 3,491 mice were genotyped by PCR before adulthood. Those of the three genotypes that were included in this study were genotyped again by PCR; 1 mouse failed to confirm and was excluded from analysis. The specificity of the PCR reactions was confirmed by Southern blot in a subset of the mice. There were no instances of discrepancy between PCR and Southern blot results. Each mouse was genotyped by PCR using KlenTaq1 DNA polymerase and the following primer pairs. For WT iNOS alleles, the common 5′ primer (NOS-A) corresponds to bp 730–749 of the published sequence (31), and is located upstream of the deletion in the knockout mice: 5′-ATCAGCCTTTCTCTGTCTCC-3′. The 3′ primer for WT iNOS (NOS-B) corresponds to bp 337–356 and with NOS-A will generate a 413-bp fragment: 5′-GGCTTTCTGTCTGTTCTCTC-3′. For disrupted iNOS alleles, the 3′ primer for the mutant allele is homologous to sequences in the neomycin gene and with NOS-A will generate a 268-bp fragment: 5′-GCCTGAAGAACGAGATCAGCAGCCTCTG-3′. For the hAPP transgene, a 300-bp fragment is generated by the following primers (32): 5′-GTGGATAACCCCTCCCCCAGCCTAGACCA-3′ and 5′-CTGACCACTCGACCAGGTTCTGGGT-3′. For hPS1 transgene, an ∼300-bp fragment is generated by the following primers: 5′-GTGAAGGAACCTTATTCTGTGGTG-3′ and 5′-GTCCTTGGGGTCTTCTACCTTTCTC-3′.

Southern blot.

Probes were amplified from genomic DNA using the following forward and reverse primers, respectively. For iNOS: 5′-GTCCAGGCTGGTACCTGACCTGACCTTAATGC-3′; 5′-TTGGAGTGCTTGGCTGAATTCTGTTAT-3′ (476 bp) (26). For the hAPP transgene: 5′-GTGGATAACCCCTCCCCCAGCCTAGACCA-3′ and 5′-CTGACCACTCGACCAGGTTCTGGGT-3′. (∼300 bp) (32). As a control, a probe also was used for the endogenous prion protein: 5′-GTGGATAACCCCTCCCCCAGCCTAGACCA-3′ and 5′-AAGCGGCCAAAGCCTGGAGGGTGGAACA-3′ (∼600 bp) (32). For the hPS1 transgene: 5′-GTGAAGGAACCTTATTCTGTGGTG-3′ and 5′-GTCCTTGGGGTCTTCTACCTTTCTC-3′ (∼300 bp). Probes were radiolabeled with Prime-a-Gene (Promega). Phenol-chloroform–extracted genomic DNA (10 μg) was restricted with KpnI for iNOS and with BamHI or EcoRI for hAPP and hPS1.

Preparation of brains.

For immunohistology, mice were anesthetized deeply with pentobarbital and perfused intracardially with ice-cold 0.9% saline followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 (PB). Brains were fixed <24 h in 10% neutral buffered formalin, washed in PB, and hemisected sagitally. One hemisphere was cryoprotected in 30% glycerol, 30% ethylene glycol/0.02 M PB and stored at −20°C for preparation of 35 micron frozen sections. The other hemisphere was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for <24 h, transferred to 70% ethanol, and paraffin embedded by standard methods. For Western blots, the perfusion omitted paraformaldehyde and the brains were placed directly in the cryoprotectant solution.

To prepare brain extracts for anti-iNOS and anti-nitrotyrosine immunoblots, 150 ml 0.9% NaCl was used for transcardial perfusion without fixative. Brain quarters were boiled for 10 min in 120 μl sample buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, and 20% glycerol), followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 30 min, and supernatant was stored at −80°C for immunoblot. Protein concentration was determined by BioRad assay.

Antibodies.

For immunohistology, rabbit anti-iNOS antiserum (anti-holoiNOS) was raised against pure, native mouse iNOS (21), and subjected to extensive documentation of monospecificity after ultracentrifugation. These tests included, as a positive control, reactivity with cells in sections of footpads from WT mice infected with Leishmania major (gift from R. Almeida, (Federal University of Bahia, Bahia, Brazil) and livers from WT mice injected with Propionobacterium acnes followed 6 d later by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. As negative controls, we used livers from untreated WT mice and livers from P. acnes– and LPS-treated iNOS knock-out mice. The antiserum was positive with the positive controls, and negative with the negative controls. The positive samples were negative using nonspecific rabbit IgG in place of anti-iNOS or omitting primary antibody. Moreover, preimmune rabbit serum gave no reaction with sections of brains from AD-transgenic mice expressing iNOS. For further specificity controls, antibody to mouse NOS1 (Santa Cruz K-20) was used to document reaction with NOS1 in cerebellum of WT mice under the same conditions where the anti-iNOS antiserum was negative with cerebellum. Antibody to mouse NOS3 (Santa Cruz N-20) was used to document reaction with NOS3 in heart of WT mice under the same conditions where the anti-iNOS antiserum was negative with heart. Finally, all results with immunohistochemistry were confirmed by immunoblot. Thus, anti-iNOS antiserum was monospecific for iNOS in mouse, and did not react with mouse NOS1, mouse NOS3, or any other detectable moiety in inflamed organs of iNOS-knock out mice. This anti-iNOS antiserum was furnished to Upstate Biotechnology. Equivalent results were obtained using the original antiserum and samples that we subsequently purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. We have reported similar documentation of specificity for anti-iNOS mAbs 1E8B8 and 5BE36 (Research & Diagnostic Antibodies) (33). For Western blot, we used rabbit anti-iNOS amino terminal domain (Upstate Biotechnology). Aβ was stained with an affinity-purified rabbit antibody specific to the COOH terminus of the Aβ(1–42) peptide (5 μg/ml; cat. no. AB5078P; Chemicon). The following antibodies also were used: rabbit anti-GFAP (1:1,000; DakoCytomation), rat anti–mouse CD40 (1:100; Serotec), rabbit antinitrotyrosine (1:50; Upstate Biotechnology), and rabbit polyclonal antibody against tau (phospho T205; 1:100; Abcam Inc.). Antinitrotyrosine slot-blots used mAb 1A6 (0.5 μg/ml) from Upstate Biotechnology.

Immunohistology.

Specimens were provided by M. Sporn (Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH); K. Hsiao (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN); J. Clemens (E. Lilly, Inc., Indianapolis, IN); P. Davies and L. Van Der Ploeg (Merck, Inc., Rahway, NJ); K. Duff and Y. Masugi (New York University, New York, NY); and S. Fu and J. Merrill (Aventis, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ). Staining for iNOS was performed on paraffin-embedded sections as follows. For sections shown in Fig. S1, A–D, brains in cryoprotectant solution (30% ethanol [EtOH], 30% ethylene glycol, 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2) were washed in sodium phosphate buffer and put on a Tissue-Tek V.I.P. automated tissue processor with the following cycles: 70% EtOH 45 min, 95% EtOH 45 min, 95% EtOH 45 min, 100% EtOH 45 min, 100% EtOH 45 min, xylene 45 min, xylene 60 min, xylene 60 min, paraffin 60 min, paraffin 60 min, paraffin 120 min (total processing time 10.5 h). Those shown in Fig. S1, E–F were processed for paraffin microtomy using standard vacuum paraffin infiltration. Sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized and blocked for endogenous biotin using the Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (Biocare). Antigen retrieval was performed in Borg solution (Biocare) in a pressure cooker for 5 min. Sections were stained with biotinylated mAbs, using the MM Biotinylation Strep/HRT kit (Biocare), or rabbit polyclonal iNOS II (see above), using the Ultratek Strep/HRP (ScyTek). Stains were developed using Carassian DAB (Biocare) and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

Sections for Aβ (1–42) immunohistology were pretreated with 90% formic acid for 5 min at room temperature before immunostaining. A modified avidin-biotin peroxidase technique was used. In brief, sections were treated with 3% H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase. Sections were incubated sequentially in 1% BSA/0.2% Triton, primary antibody, appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody, and avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories). The immunoreaction was visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride dihydrate (DAB) with nickel intensification (Vector Laboratories) as the chromogen. The sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped.

Aβ deposits were visualized and quantitated using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope with a video camera attached to a computer. The Aβ (1–42)-immunostained sections were viewed with a 10× objective, and digital images were captured using the Stereo Investigator 4.35 software program (Microbrightfield). Images of brain areas (0.75 mm2) were saved as tagged image format files. The regions analyzed included the retrosplenial/motor cortex and CA1/dentate region of the hippocampus. The retrosplenial/motor cortex was analyzed in five sections (350 μm apart) per mouse beginning at the level of bregma −1.06. The CA1/dentate region was analyzed in five sections (350 μm apart) per mouse beginning at the level of bregma −1.34. Quantitative analysis was performed using the NIH Image 1.63 software. The threshold was set at 50. The data were exported to Microsoft Excel for calculating the amyloid burden and mean number of plaques/0.75 mm2. Amyloid burden was calculated as the percentage of area occupied by the Aβ deposits in each region. The same procedure was used for quantifying microgliosis. The percentage of CD40-immunolabeled area in each region was determined. For quantitation of astrocytes, the optical fractionator was used to estimate the number of GFAP-immunoreactive cells within the areas used for quantification of Aβ plaque burden and number.

Immunoblots and ELISA.

Brain extracts (150 μg/mouse for iNOS blot; 50 μg/mouse for nitrotyrosine blot) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and blotted with antibodies against iNOS (see above) or phospho-T205 of tau (1:1,000, ab4841, Abcam Inc.). Blots were developed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated second antibody, visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence with a substrate kit (Pierce Chemical Co.), and exposed to Kodak BioMax M r film. Relative loading among samples was assessed by reblotting the same membrane with anti–α-tubulin (1 μg/ml, ICN Biomedicals). For detecting nitrotyrosine proteins, brain extracts (150 μg/mouse) were mixed with 150 μl Tris-glycine buffer (25 mM Tris-OH, 190 mM glycine, pH 8.3 plus 20% MeOH), and loaded onto a nitrocellulose membrane using a Hoefer PR648 slot blot. The filter was blotted with anti-nitrotyrosine mAb and visualized as described before.

For Aβ immunoblots, unfixed brains were stored in cryoprotectant at −20°C. The anterior third of the right hemisphere (50–70 mg) was lysed by sonication (Branson Sonifier 250, 80% duty cycle, output 6) and sequentially extracted in 10 volumes each of 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (138 mM NaCl), pH 7.0 (PBS), followed by 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, and then 6% SDS in water. All solutions contained a protease cocktail (Roche, Complete Protease Inhibitor, 1 tablet/50 ml). Centrifugations were in a Beckman TA15-1.5 rotor at 15,000 rpm (25,200 g) for 270 min, at 4°C. The final 6% SDS extract was used for Aβ analysis. Protein concentration was determined by a detergent-compatible Lowry technique (Biorad, DC Protein Assay). 10 μg of protein was subjected to 10–20% Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE and transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were boiled in PBS for 5 min to expose epitopes, and then immunoblotted with 6E10, a mouse IgG1 mAb raised against human Aβ residues 1–17 (1:1,000; Signet Laboratories). Bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Image intensity was quantified with Scion Image 4.02 software, and normalized to β-actin immunostaining on the same blots.

Aβ ELISAs were performed on the same homogenates that were used for Aβ Western blotting with a colorimetric kit (Biosource International), using mAb 6E10 as above. Measurements were normalized to brain weight.

Video camera recordings.

Mice were housed individually in cages whose water bottles were replaced with gel packs located under the food bin for improved visibility from above. The mice were kept in the standard dark/light cycle, except that a very faint light for the dark cycle was supplied by way of reflection from a 10-W shielded bulb pointed at the wall. Recordings were made with an iSight camera (Apple Computer Inc.) connected to a G4 PowerMacintosh (Apple Computer Inc.). The sensitivity of the camera was increased ∼10-fold during the dark cycle. In the first period of recordings, images were taken at 30-s intervals. Subsequently, the frequency was increased to 15-s intervals. Images were collected by way of EvoCam 3.5 software (Evological Inc., www.evological.com). Recordings were analyzed by one observer, who was blind to the strain of the mice. The observer looked for seizures (none was detected); logged periods of sleep; and characterized motor activity, such as ambulation and hanging from the cage lid. Sleep was defined as an interval of 8 min or longer during which the mouse did not relocate its center of mass and was not engaged in feeding. An interval of sleep was counted as one episode of sleep if it included no more than one excursion lasting <1 min that was preceded and followed by at least 8 min of immobility.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 provides immunohistologic evidence for expression of iNOS in brains of mice with or without AD-related transgenes. Fig. S2 illustrates CD40 staining in the cortex. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051529/DC1.

Acknowledgments

For hAPP+/0 and hPS1+/0 mice, we thank H. Zheng. For help with husbandry, assays, or reagents, we thank R. Arriola, S. Brown, M. Crabtree, M. Diaz, K. Flanders, C. Hickey, F. Homberger, N. Lipman, Y. Maldonado, M. Quimson, N. Roberts, S. Sprague, and R. Thurlow (Weill Medical College); E. Genova; and W. Smith.

Support was provided by National Institutes of Health grants AG19520 and AG20729, the Alice Bohmfalk Charitable Trust, and the Robert Leet and Clara Patterson Trust. The Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Weill Cornell Medical College, acknowledges the support of the William Randolph Hearst Foundation.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Rossi, F., and E. Bianchini. 1996. Synergistic induction of nitric oxide by beta-amyloid and cytokines in astrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 225:474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barger, S.W., and A.D. Harmon. 1997. Microglial activation by Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein and modulation by apolipoprotein E. Nature. 388:878–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishii, K., F. Muelhauser, U. Liebl, M. Picard, S. Kuhl, B. Penke, T. Bayer, M. Wiessler, M. Hennerici, K. Beyreuther, et al. 2000. Subacute NO generation induced by Alzheimer's beta-amyloid in the living brain: reversal by inhibition of the inducible NO synthase. FASEB J. 14:1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith, M.A., P.L. Richey Harris, L.M. Sayre, J.S. Beckman, and G. Perry. 1997. Widespread peroxynitrite-mediated damage in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 17:2653–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hensley, K., M.L. Maidt, Z. Yu, H. Sang, W.R. Markesbery, and R.A. Floyd. 1998. Electrochemical analysis of protein nitrotyrosine and dityrosine in the Alzheimer brain indicates region-specific accumulation. J. Neurosci. 18:8126–8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tohgi, H., T. Abe, K. Yamazaki, T. Murata, E. Ishizaki, and C. Isobe. 1999. Alterations of 3-nitrotyrosine concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid during aging and in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 269:52–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luth, H.J., G. Munch, and T. Arendt. 2002. Aberrant expression of NOS isoforms in Alzheimer's disease is structurally related to nitrotyrosine formation. Brain Res. 953:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Vizarra, P., A.P. Fernandez, S. Castro-Blanco, J.M. Encinas, J. Serrano, M.L. Bentura, P. Munoz, R. Martinez-Murillo, and J. Rodrigo. 2004. Expression of nitric oxide system in clinically evaluated cases of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 15:287–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castegna, A., V. Thongboonkerd, J.B. Klein, B. Lynn, W.R. Markesbery, and D.A. Butterfield. 2003. Proteomic identification of nitrated proteins in Alzheimer's disease brain. J. Neurochem. 85:1394–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vodovotz, Y., M.S. Lucia, K.C. Flanders, L. Chesler, Q.W. Xie, T.W. Smith, J. Weidner, R. Mumford, R. Webber, C. Nathan, et al. 1996. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in tangle-bearing neurons of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Exp. Med. 184:1425–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, S.C., M.L. Zhao, A. Hirano, and D.W. Dickson. 1999. Inducible nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in the Alzheimer disease hippocampus: association with Hirano bodies, neurofibrillary tangles, and senile plaques. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58:1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heneka, M.T., H. Wiesinger, L. Dumitrescu-Ozimek, P. Riederer, D.L. Feinstein, and T. Klockgether. 2001. Neuronal and glial coexpression of argininosuccinate synthetase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60:906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong, A., H.J. Luth, W. Deuther-Conrad, S. Dukic-Stefanovic, J. Gasic-Milenkovic, T. Arendt, and G. Munch. 2001. Advanced glycation endproducts co-localize with inducible nitric oxide synthase in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 920:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsuse, O., E. Iseki, and K. Kosaka. 2003. Immunohistochemical study of the expression of cytokines and nitric oxide synthases in brains of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuropathology. 23:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagasra, O., F.H. Michaels, Y.M. Zheng, L.E. Bobroski, S.V. Spitsin, Z.F. Fu, R. Tawadros, and H. Koprowski. 1995. Activation of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase in the brains of patients with multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:12041–12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamson, D.C., B. Wildemann, M. Sasaki, J.D. Glass, J.C. McArthur, V.I. Christov, T.M. Dawson, and V.L. Dawson. 1996. Immunologic NO synthase: elevation in severe AIDS dementia and induction by HIV-1 gp41. Science. 274:1917–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster, C., H.B. Clark, M.E. Ross, and C. Iadecola. 1999. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human cerebral infarcts. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.). 97:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki, S., N. Shibata, T. Komori, and M. Iwata. 2000. iNOS and nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 291:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knott, C., G. Stern, and G.P. Wilkin. 2000. Inflammatory regulators in Parkinson's disease: iNOS, lipocortin-1, and cyclooxygenases-1 and -2. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 16:724–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho, H.J., Q.W. Xie, J. Calaycay, R.A. Mumford, K.M. Swiderek, T.D. Lee, and C. Nathan. 1992. Calmodulin is a subunit of nitric oxide synthase from macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 176:599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie, Q.W., H.J. Cho, J. Calaycay, R.A. Mumford, K.M. Swiderek, T.D. Lee, A. Ding, T. Troso, and C. Nathan. 1992. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science. 256:225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncada, S., and J.D. Erusalimsky. 2002. Does nitric oxide modulate mitochondrial energy generation and apoptosis? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beal, M.F. 2000. Energetics in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 23:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung, K.K., B. Thomas, X. Li, O. Pletnikova, J.C. Troncoso, L. Marsh, V.L. Dawson, and T.M. Dawson. 2004. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin's protective function. Science. 304:1328–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller, J.N., K.B. Hanni, and W.R. Markesbery. 2000. Impaired proteasome function in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 75:436–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacMicking, J.D., C. Nathan, G. Hom, N. Chartrain, D.S. Fletcher, M. Trumbauer, K. Stevens, Q.W. Xie, K. Sokol, N. Hutchinson, et al. 1995. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 81:641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiao, K., P. Chapman, S. Nilsen, C. Eckman, Y. Harigaya, S. Younkin, F. Yang, and G. Cole. 1996. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 274:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigo, J., P. Fernandez-Vizarra, S. Castro-Blanco, M.L. Bentura, M. Nieto, T. Gomez-Isla, R. Martinez-Murillo, A. MartInez, J. Serrano, and A.P. Fernandez. 2004. Nitric oxide in the cerebral cortex of amyloid-precursor protein (SW) Tg2576 transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 128:73–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian, S., P. Jiang, X.M. Guan, G. Singh, M.E. Trumbauer, H. Yu, H.Y. Chen, L.H. Van de Ploeg, and H. Zheng. 1998. Mutant human presenilin 1 protects presenilin 1 null mouse against embryonic lethality and elevates Abeta1-42/43 expression. Neuron. 20:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luth, H.J., M. Holzer, U. Gartner, M. Staufenbiel, and T. Arendt. 2001. Expression of endothelial and inducible NOS-isoforms is increased in Alzheimer's disease, in APP23 transgenic mice and after experimental brain lesion in rat: evidence for an induction by amyloid pathology. Brain Res. 913:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie, Q.W., R. Whisnant, and C. Nathan. 1993. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon gamma and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 177:1779–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsiao, K.K., D.R. Borchelt, K. Olson, R. Johannsdottir, C. Kitt, W. Yunis, S. Xu, C. Eckman, S. Younkin, D. Price, et al. 1995. Age-related CNS disorder and early death in transgenic FVB/N mice overexpressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 15:1203–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholson, S., G. Bonecini-Almeida Mda, J.R. Lapa e Silva, C. Nathan, Q.W. Xie, R. Mumford, J.R. Weidner, J. Calaycay, J. Geng, N. Boechat, et al. 1996. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 183:2293–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]