Abstract

Natural killer (NK) T cells are activated by synthetic or self-glycolipids and implicated in innate host resistance to a range of viral, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens. Despite the immunogenicity of microbial lipoglycans and their promiscuous binding to CD1d, no pathogen-derived glycolipid antigen presented by this pathway has been identified to date. In the current work, we show increased susceptibility of NK T cell–deficient CD1d−/− mice to Leishmania donovani infection and Leishmania-induced CD1d-dependent activation of NK T cells in wild-type animals. The elicited response was Th1 polarized, occurred as early as 2 h after infection, and was independent from IL-12. The Leishmania surface glycoconjugate lipophosphoglycan, as well as related glycoinositol phospholipids, bound with high affinity to CD1d and induced a CD1d-dependent IFNγ response in naive intrahepatic lymphocytes. Together, these data identify Leishmania surface glycoconjugates as potential glycolipid antigens and suggest an important role for the CD1d–NK T cell immune axis in the early response to visceral Leishmania infection.

Keywords: Trypanosomatidae, glycoconjugates, CD1d antigen, natural immunity

Introduction

Protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania are responsible for a spectrum of diseases collectively termed leishmaniasis, that afflict millions of people worldwide (1). Depending on parasite species and host immune response, Leishmania infection ranges from self-healing cutaneous lesions, destructive skin, and mucosal disease to the fatal visceral infection caused, for example, by Leishmania donovani. No clinically effective vaccine exists.

Leishmania is transmitted by the bite of infected Phlebotomine sand flies that inoculate highly infective metacyclic promastigotes into the mammalian host, where they differentiate inside macrophage phagolysosomes into the replicative amastigote form. The remarkable resistance of Leishmania to hydrolytic environments, encountered in both the insect and mammalian hosts, is conferred by a dense surface glycocalyx, formed by related glycoinositol phospholipids (GIPLs) and lipophosphoglycan (LPG), and proteins such as the parasite surface protease gp63, proteophosphoglycans and gp46. LPG is the major component of the surface glycocalyx and is composed of a [Galα1-4Manα1-PO4] repeat unit that is attached to the parasite membrane through a heptasaccharide core and a 1-O-alkyl-2-lyso-phosphatidylinositol lipid anchor (2). LPG is an important virulence determinant implicated in many aspects of parasite pathogenicity (3). It confers resistance to lytic complement (4), scavenges toxic host cell oxygen radicals (4, 5), and inhibits phagolysosomal fusion (4, 6), thereby inactivating several important innate host defense mechanisms.

Mammalian hosts have evolved pathways of natural immunity that recognize pathogen-derived glycolipids such as LPG of Leishmania, and can initiate appropriate antimicrobial immune responses. One potential pathway for host responses to pathogen-derived glycolipids involves the CD1 system of MHC class I–like proteins (7). CD1d, the only CD1 isoform expressed in the mouse, is the ligand for the TCRs of a subset of innatelike lymphocytes, which are referred to as NK T cells and are classified according to their reactivity and TCR usage. Many of these cells express a canonical Vα14Jα18 TCRα-chain and are referred to as invariant NK T cells (iNK T cells). The iNK T cell population is also characterized by its uniform reactivity with a specific form of α-galactosylceramide (αGC) known as KRN7000, a synthetic analogue of a marine sponge glycolipid considered to be a prototype NK T cell ligand (8). However, considerable variability occurs within the TCRβ-chain repertoire of iNK T cells, which may extend their range of glycolipid recognition beyond αGC (9). In contrast, a smaller subset of NK T cells with more diverse TCRs (dNK T cells) do not respond to αGC but to other, unknown ligands in the context of CD1d (10).

As a surrogate antigen, αGC has been very useful in determining the contribution of iNK T cells to antitumor activity and autoimmune disease (11). A potential role for iNK T cells in antimicrobial resistance has been postulated based on the increased resistance of αGC-treated mice during experimental infection with hepatitis B virus (12), cytomegalovirus (13), Mycobacteria (14), murine malaria (15), and Trypanosoma cruzi (16). Likewise, CD1d-deficient mice, which lack both iNK T cells and dNK T cells, show increased susceptibility to various bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections (17), suggesting that CD1d-restricted lymphocytes are an important component in the response to pathogens. However, the use of αGC provides serious limitations for the study of CD1d-restricted T cells during infection, as neither the stimulus nor the robust induction of IFNγ and IL-4 may accurately replicate what occurs in natural infection. Also, to the best of our knowledge, no microbial glycolipid antigen presented by CD1d or capable of activating NK T cells has been defined to this date, even though microbial lipoglycans can be bound by CD1d (18, 19–21).

Here, we demonstrate that CD1d is required for full host resistance to L. donovani in liver and spleen during mouse infection, and for normal development of the granulomatous response characteristic of visceral leishmaniasis. We identified the major Leishmania surface glycoconjugate LPG as a potential glycolipid antigen, which binds to CD1d and stimulates robust IFNγ production in naive hepatic lymphocytes. Although NK T cells play only a minor role at most in the peripheral immune response during experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis (22–24), our results indicate that intrahepatic CD1d-restricted lymphocytes contribute significantly to resistance to visceral leishmaniasis.

Materials and Methods

Leishmania Culture.

Promastigotes of L. donovani LD1S clone 2D (designation MHOM/SD/62/1S-CL2D by the WHO; reference 25) were grown at 26°C in medium M199 containing 10% FBS as described previously (26).

Mouse Strains and Infection.

Female CD1d-deficient C.129S2-Cd1tm1Gru (backcrossed for 11 generations on a BALB/c background), IL-12p40–deficient B6.129S1-IL12btm1Jm/J, and their respective congenic controls were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. For mouse infections, 107 promastigote parasites from day 4 of stationary culture or splenic amastigotes (1 Sudan strain) obtained from infected hamsters were inoculated in a volume of 200 μl into mice via tail vein injection (27). Parasite burden in liver and spleen was assessed microscopically at regular intervals between 1 and 8 wk after inoculation by tissue imprints and Giemsa staining, and parasite burden was estimated by counting the number of amastigotes per 1,000 cell nuclei times the organ weight in milligrams (Leishman Donovan Units). For anti-CD1d antibody-treatment, 0.5 mg of affinity-purified anti-CD1d mAb isolated from hybridoma 1B1 culture supernatant was injected i.p. 1 d before L. donovani infection (hybridoma was provided by M. Kronenberg, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, San Diego, CA; reference 28). Granuloma formation was assessed by haematoxylin staining of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Granulomas were scored as immature (developing, no, or only few lymphocytes associated) or mature (more than five lymphocytes associated), or if devoid of visible intracellular amastigotes, as “cured” (29).

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from infected unperfused liver tissue with the TRIzol reagent (GIBCO BRL) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, resuspended in RNase-free water, and stored at −80°C. Reverse transcription and PCR was performed with the Taqman one-step RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) using 20 μg total RNA. Specific probes for Leishmania 18S rRNA (forward primer 5′-CGTAGGCGCAGCTCATCAA-3′, reverse primer 5′-AACGACGGGCGGTGTGTA-3′, and probe 5′-TGTGCCGATTACGTCCCTGCCA-3′) and eukaryotic 18S rRNA (Applied Biosystems) labeled with both a reporter and a quencher dye was added into the RT-PCR mix at the beginning of the reaction. Relative parasite burden was determined according to the formula 2−ΔΔCt, where Ct is the threshold cycle number, ΔCt = Ctleishmania 18S rRNA − Cteukaryotic 18S rRNA, and ΔΔCt = ΔCtuninfected − ΔCtinfected. Analysis was performed using the ABI Prism 7900HT apparatus (PerkinElmer).

Glycolipids and Glycolipid Purification.

Purified sulfatide (galacto-cerebroside sulfate) from bovine brain was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The preparation of αGC used in this work was synthesized using a method developed by the authors that will be described elsewhere (unpublished data). The structure of the αGC used in the current work was identical to that previously published for KRN7000 (30), except that the fatty acid chain length was two carbons shorter (C24:0 instead of C26:0). Synthetic αGC was purified to homogeneity, and the structure was validated by mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. LPG from log phase promastigote cultures was extracted in solvent E (H2O/ethanol/diethyl ether/pyridine/NH4OH; 15:15:5:1:0.017) as described previously (31). The solvent E extract was dried by N2 evaporation, resuspended in 0.1 N acetic acid/0.1 M NaCl, and applied to a column of 2 ml phenyl-sepharose, equilibrated in the same buffer, and eluted with solvent E. Promastigote GIPLs were extracted and purified as described previously (32). In brief, cell pellets were extracted twice in five volumes of chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:0.8, by volume), and the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (5,000 g, 15 min). Water was added to the combined supernatants to give a final chloroform/methanol/water ratio of 4:8:5.6 (by volume), and the two phases were separated by centrifugation (14,000 g, 1 min). The upper aqueous phase was dried under nitrogen, and nonlipidic material was removed by chromatography on a small column of 2 ml octyl-sepharose, eluted first with 0.1 M NH4OAc, 5% (vol/vol) 1-propanol (10 ml) followed by 40% 1-propanol (5 ml). The LPG was depolymerized with mild acid (0.02 N HCl, 100°C, 5 min), and the water-soluble fragments were removed by water-saturated butanol partitioning (33). The phosphorylated glycan core-PI was dephosphorylated with alkaline phosphatase in 15 mM Tris HCl, pH 9.0 (1 U, 16 h, 37°C), and treated with green coffee bean α-galactosidase in 0.1 M citric acid, 0.2 N sodium phosphate, pH 6.9 (1 U, 16 h, 25°C) as described previously (34).

Liver-Lymphocyte Preparation, Intracellular Cytokine Staining, and Flow Cytometry.

Livers were perfused with ice-cold PBS, pressed through a 70-mm cell strainer, and cell suspensions were centrifuged twice at 200 g for 2 min to remove cell debris and hepatic parenchymal cells. Supernatants were resuspended in a 40% isotonic Percoll solution (Amersham Biosciences), underlayed with 60% isotonic Percoll solution, and centrifuged for 20 min at 900 g. Liver lymphocytes were recovered from the 40/60% interface, washed once with cold RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies), and resuspended in FACS buffer containing 1% BSA and 0.02% NaN3. Cell staining was performed in a volume of 50 μl in 96-well plates. In brief, 105 cells were incubated for 15 min at 4°C with 2.4G2 anti-FcγR mAb (BD Biosciences) to block nonspecific antibody binding and incubated for a further 20 min at 4°C with FITC or PerCP-conjugated 145-2C11 anti-CD3ɛ mAb (BD Biosciences) and PE-conjugated αGC-loaded mCD1d tetramers (35) and unloaded controls. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed on CD1d-tetramer labeled cells using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences) in combination with FITC-conjugated XMG1.2 anti-IFNγ mAb and allophycocyanin-conjugated 11B11 anti–IL-4 mAb (BD Biosciences). Background fluorescence was controlled using fluorophore-conjugated isotype-specific antibodies and unloaded tetramer. Fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry with a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument (excitation, 455 and 635 nm).

Dendritic Cell Isolation, Infection, and T Cell Activation Assay.

Bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (hence referred to as BM-DCs) from female C57BL/6 mice were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 30% conditioned supernatant from myeloma cell line Ag8653-expressing mouse GM-CSF (36). DC differentiation was verified by measuring CD11c expression by flow cytometry. After 6 d of culture, cells were detached by treatment with PBS/200 μM EDTA at 4°C, and 104 BM-DCs/well were seeded in 96-well plates (BD Biosciences). Infection of BM-DCs was performed using cultured LD1S promastigotes from day 2 of stationary growth at a ratio of 10 parasites per host cell. Uningested parasites were removed 2 h after incubation at 37°C by washing. For T cell activation, BM-DCs were pulsed for 2 h with 100 ng/ml αGC or 5 μM of purified LPG for 12 h at 37°C. 5 × 104 cells of mouse iNK T cell hybridoma DN34A-1.2 (37) or 104 liver lymphocytes from naive C57BL/6 mice were added per well and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in RPMI 1640 10% FCS. Thereafter, murine IL-2 and IFNγ production were assessed by standard capture ELISA (BD Biosciences). All culture media were endotoxin free by the Pyrotell Limulus Amebocyte Lysate test (Associates of Cape Cod Inc.).

LPG-binding and Competition Assay.

Mouse recombinant CD1d proteins were prepared using a baculovirus expression system as described previously (37). Purified L. donovani GIPLs or LPG, and sulfatide (Sigma-Aldrich) at various molar excesses were preincubated with 0.5 μM (25 μg/ml) soluble CD1d proteins in 15 μl for 1 h at 37°C. The lipid–CD1d complexes were diluted with PBS to a final concentration of 0.05 μM (2.5 μg/ml), and triplicate wells of a microtiter plate were coated with 50 μl aliquots. Unbound glycolipids and CD1d proteins were removed by washing with PBS, and complexes were further incubated with 2 nM αGC for various times. After washing with PBS to remove unbound αGC, mouse NK T hybridoma DN32D3 cells (5 × 104/well; reference 19) were added and incubated for 20 h in 200 μl of complete media at 37°C. Levels of murine IL-2 were measured by the standard capture ELISA (BD Biosciences). Displacement of prebound glycolipid was analyzed using CD1d-coated 96-well plates (0.05 μM CD1d in 50 μl for 1 h at 37°C), which were sequentially incubated with 33 nM αGC and 33 nM of purified LPG (or vice versa), each for 1 h at 37°C. For competition assay, 33 nM αGC was added along with increasing concentrations of LPG ranging between 1 and 333 nM, and αGC binding was determined by IL-2 production of mouse NK T hybridoma DN32D3 (5 × 104) 16 h later.

Results

Increased Susceptibility to Visceral Leishmania Infection in CD1d-deficient Mice.

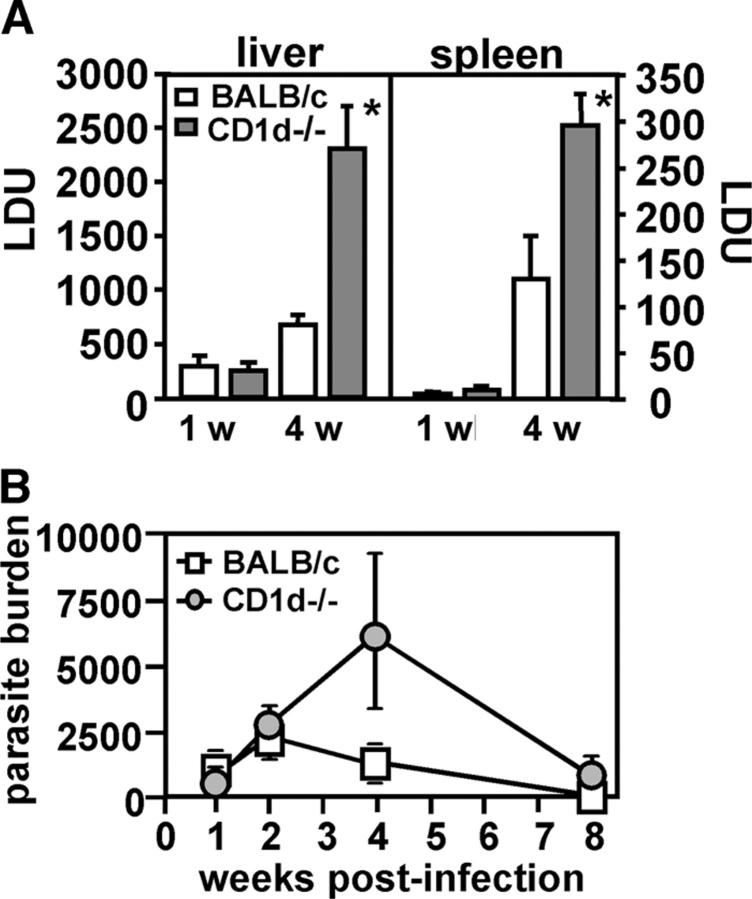

We tested the relevance of the CD1d–NK T cell immune axis in antileishmanial immunity by infection of NK T cell–deficient CD1d−/− mice and congenic BALB/c controls. Groups of mice were inoculated with splenic amastigotes, and parasite burden was assessed during 8 wk after infection in liver and spleen. 1 wk after the infection, the parasite burden was equally low in both mutant and control mice (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, at week 4, liver burdens were 3.5-fold and spleen burdens were 2.5-fold greater in CD1d-deficient animals versus control mice. These results suggest that CD1d-restricted lymphocytes do not eliminate parasites or infected host cells during the innate response, but rather contribute to the development of a protective immune response.

Figure 1.

Requirement for CD1d expression for normal antileishmanial resistance. (A) Mouse infection. Female CD1d-deficient BALB/c mice and congenic controls were inoculated with 107 splenic amastigotes by tail vein injection, and parasite burden in liver and spleen was assessed microscopically on Giemsa-stained tissue imprints, and expressed as Leishman Donovan Units (LDU; see Materials and Methods). Groups of three to five mice were analyzed per time point. One out of two independent experiments with similar outcome is shown. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences relative to Leishmania–infected BALB/c wild-type mice (P = 0.006 for liver and 0.02 for spleen; unpaired Student's t test). (B) Real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA from infected livers was extracted at the times indicated and reverse transcribed, and relative parasite burden was assessed by real-time PCR using specific probes for Leishmania 18S rRNA and mammalian 18S rRNA as described in Materials and Methods. Averages of three to five mice were plotted for each time point. Standard deviation is represented by the bars.

Assessment of parasite burden by real-time PCR confirmed the increased susceptibility of CD1d-deficient mice and established a peak parasite load at 4 and 8 wk in liver and spleen respectively (Fig. 1 B and not depicted). Despite increased parasite burden at week 4, CD1d−/− animals were able to control liver infection at week 8. Analysis of the liver lymphocyte populations by flow cytometry revealed a twofold increase of CD8+ T cells in CD1d-deficient mice 4–8 wk after parasite inoculation (unpublished data), which, together with innatelike lymphocytes in the liver, such as γδT cells, may partially compensate for the lack of CD1d-restricted T cells (38).

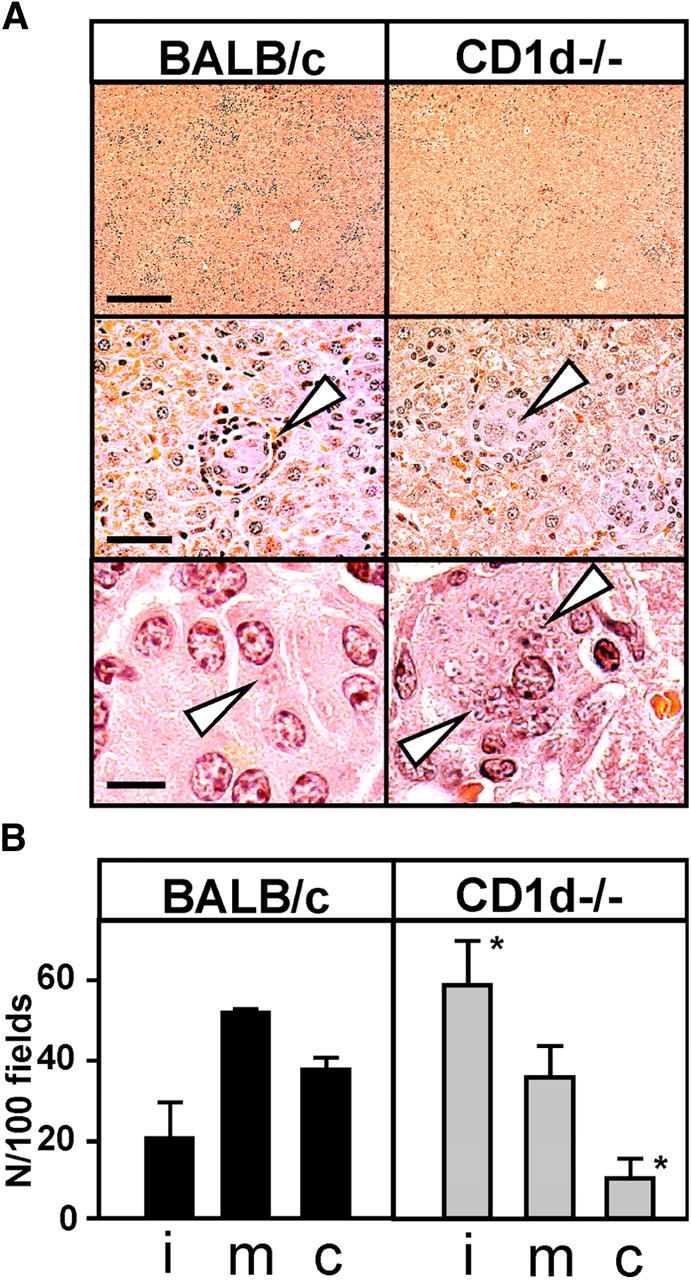

Defective Granulomatous Responses in CD1d− Mice.

In experimental visceral leishmaniasis, resistance to L. donovani depends on T cell–mediated formation of tissue granulomas, which are assembled around a core of fused, parasitized resident macrophages (29). We analyzed granuloma formation in CD1d−/− mice and controls 4 wk after infection. Compared with the response in control animals, liver sections of CD1d−/− mice showed a marked decrease of mononuclear cell infiltration (Fig. 2 A, top), and few or no mononuclear cells were associated with predominantly immature (∼60%) granulomas at sites of heavily parasitized Kupffer cells (Fig. 2 A, middle and bottom). Only ∼10% of parasite-free granulomas were present in livers of deficient mice. In contrast, BALB/c controls showed predominantly mature granulomas, and ∼50% of these collections were parasite-free and thus scored as “cured” (Fig. 2 B, left). The total number of infected foci, identified by the presence of >5 mononuclear cells associated with parasitized Kupffer cells (29), was not significantly altered in deficient mice. Together, these results implicate CD1d-dependent T cells in the granulomatous response during liver infection, and suggest that defective granuloma assembly likely contributes to the increased susceptibility of CD1d−/− mice to L. donovani.

Figure 2.

Participation of CD1d in the granulomatous response to L. donovani. (A) Histological analysis. Female BALB/c mice were killed 4 wk after infection, and livers were fixed for 12 h in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin. The core of the granuloma containing infected Kupffer cells is denoted by arrowheads. The bars correspond to 500 μm (top), 100 μm (middle), and 20 μm (bottom). (B) Quantification of granuloma formation. The number of granulomas per 100 fields and the maturation state (i, immature; m, mature; c, cured) were analyzed microscopically. Experiments was performed in triplicate, and the bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences relative to Leishmania-infected BALB/c wild-type mice (P = 0.04 for cured, and 0.03 for immature granuloma; unpaired Student's t test).

Induction of IFNγ Production by L. donovani in CD1d-restricted Liver Lymphocytes.

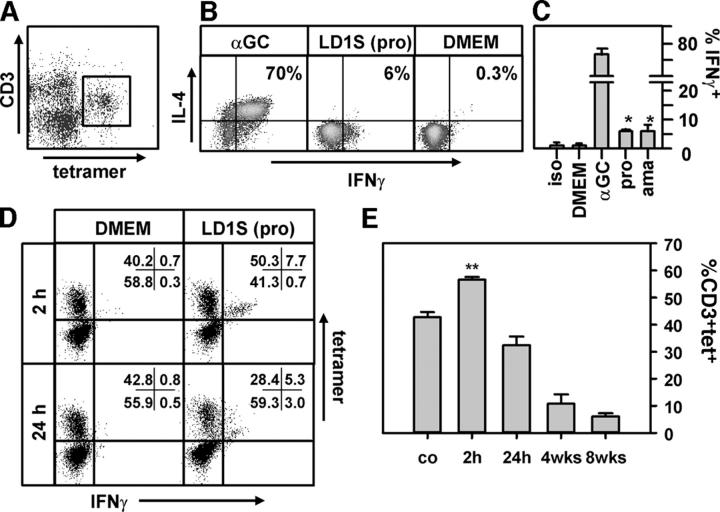

The granulomatous response during experimental visceral leishmaniasis is Th1 cell dependent and largely mediated by IFNγ (for review see reference 39). We tested if CD1d-restricted T cells produced IFNγ early during L. donovani infection by flow cytometry using αGC-loaded CD1d tetramers (Fig. 3 A). C57BL/6 mice were injected with medium (negative control), αGC (positive control), promastigotes from stationary culture, or amastigotes obtained from infected hamster spleens, and the response was assessed 2 h later by intracellular cytokine staining of liver lymphocytes. Unlike treatment with αGC, which induced IL-4 and IFNγ secretion in a majority of canonical iNK T cells (Fig. 3 B), inoculation of either promastigote or amastigote parasites resulted in induction of IFNγ without detectable IL-4 in 3–6% of the CD1d tetramer+ hepatic T cells (Fig. 3, B, middle, and C). No significant IFNγ induction occurred in the spleens of infected animals or controls injected with DMEM alone (Fig. 3 C and not depicted). Thus, intrahepatic CD1d-restricted iNK T cells rapidly produce IFNγ after Leishmania infection, which may modulate the antileishmanial immune response.

Figure 3.

IFNγ production in Leishmania-infected livers. (A) CD1d-tetramer staining. Liver lymphocytes from infected C57BL/6 mice were isolated by Percoll gradient centrifugation and stained with PeRCP-conjugated anti-CD3ɛ mAb and αGC-loaded PE-conjugated CD1d-tetramers. The tetramer positive, CD1d-reactive T cell subset is identified by flow cytometry and shows the characteristic intermediate CD3 expression. (B–E) Intracellular cytokine staining. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with medium (DMEM), 200 ng αGC, 107 stationary phase LD1S promastigotes (pro), or 107 amastigotes (ama) from infected hamster spleen, and lymphocytes were prepared and stained 2 h after the inoculation (B and C) or at the times indicated (D and E) as described before. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit from Becton Dickinson with FITC-conjugated anti-IFNγ and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti–IL-4. The analysis in B and C was gated on CD3(+)tet(+) cells. Staining with FITC-conjugated isotype-specific antibody was performed to control for background (iso). At least three independent triplicate experiments were performed, and one representative experiment is shown. For the analysis in D and E, cells were gated on CD3. One experiment was performed with three to five mice per time point. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences relative to DMEM-injected mice (*, P < 0.02; **, P < 0.01; unpaired Student's t test).

In addition to the early NK T cell activation, Leishmania had a profound effect on the NK T cell compartment throughout the entire infection period. We consistently observed an increase in tetramer+ liver lymphocytes 2 h after parasite inoculation, when robust IFNγ production was induced (Fig. 3, D and E). After 24 h, the number of IFNγ positive cells decreased, and a reduction of tet+ cells by 45% was observed, which were further reduced by 90% during the following 8 wk of infection (Fig. 3, D and E). Next, we focused on the mechanism of the early innate activation 2 h after infection. Furthermore, to avoid any concerns regarding injection of hamster-derived antigens, present in the splenic amastigote preparations, all the following studies were performed with culture promastigotes.

CD1d-dependent and IL-12–independent Activation of iNK T Cells during L. donovani Infection.

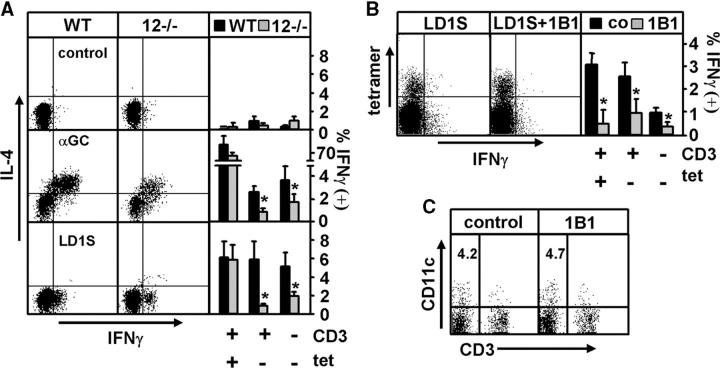

Minutes after murine L. donovani infection, large amounts of IL-12 are released from intracellular storage vesicles in DCs (40), which may enhance the response of iNK T cells to endogenous glycolipid antigens (41). We tested this possibility by following IFNγ induction during visceral infection of IL-12–deficient mice and their congenic C57BL/6 controls. Absence of IL-12 in the mutant mice had no effect on the induction of IFNγ in iNK T cells after either αGC treatment or L. donovani infection (Fig. 4 A). This result rules out that the initial activation of CD1d-restricted T cells to L. donovani was due to a direct response to IL-12. In contrast, CD3+tet− and CD3−tet− cell populations showed a strong decrease in IFNγ production in the IL-12–deficient animals upon αGC treatment or L. donovani infection (Fig. 4 A), confirming the importance of this cytokine in the activation of classical T cells and NK cells.

Figure 4.

Requirement for CD1d but not IL-12 for activation of CD3(+)tet(+) T cells in response to L. donovani. Liver lymphocytes obtained from IL-12p40−/− mice (12−/−) and congenic controls (A) or mice treated 24 h before the infection with 0.5 mg anti-CD1d blocking antibody 1B1 (B) were stained with PeRCP-conjugated anti-CD3ɛ mAb and αGC-loaded PE-conjugated CD1d tetramers, and intracellular IFNγ was revealed as described in Fig. 3. Percent IFNγ-producing cells 2 h after inoculation of αGC, 107 cultured promastigotes (LD1S), or medium (control) is shown. Results are representative of two independent triplicate experiments. (C) Quantification of CD11c(+) cells. Liver-lymphocyte preparations from untreated mice and mice treated with anti-CD1d mAb 1B1 were incubated with FcγR-blocking antibody 2.4G2 and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11c and PE-conjugated anti-CD3ɛ mAbs. Numbers indicate percent of CD11c(+)CD3(−) dendritic cells. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between wild-type and IL-12–deficient mice (*, P < 0.04; **, P < 0.01; unpaired Student's t test).

Next, we used an anti-CD1d antibody-blocking approach to assess the role of CD1d–TCR ligation in Leishmania-induced IFNγ production. Antibody-treated mice showed a more than sixfold reduction in IFNγ-producing iNK T cells during visceral Leishmania infection (Fig. 4 B), whereas production of the cytokine was reduced by only threefold in the tetramer− CD3+ and CD3− lymphocyte populations (Fig. 4 B). A major concern associated with antibody-blocking experiment arises from depletion of antibody-reactive cells, in our case CD11c+DCs, which would result in generalized immunosuppression. However, as assessed by flow cytometry, the antibody treatment did not affect the amount of CD11c+ DCs in the liver (Fig. 4 C). Together, these data implicate Leishmania glycolipids in the activation of a subset of iNK T cells through CD1d, which may contribute (likely together with IL-12; Fig. 4 A) to the activation of classical T cells and CD3− NK cells.

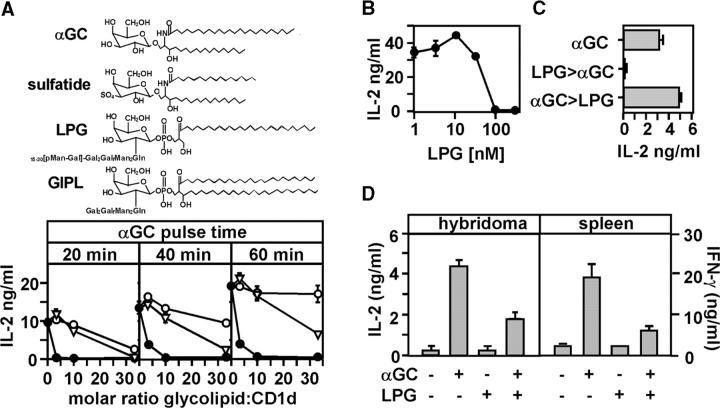

Leishmania LPG Binds to CD1d and Activates a Subset of Hepatic NK T Cells In Situ.

The Leishmania glycophospholipids LPG and GIPLs show striking structural similarity to the glycosphingolipids αGC and sulfatide, which are known CD1d-presented lipid antigens (Fig. 5 A, top and references 2, 32, 37, 42). We investigated whether purified LPG and related GIPLs bind to CD1d and, thus, may qualify as bona fide glycolipid antigens using a competitive αGC-binding assay. After incubation of soluble CD1d at increasing molar ratios with sulfatide and Leishmania glycolipids, plate-bound lipid–CD1d complexes were pulsed for various periods of time with αGC, and binding of the synthetic glycolipid was determined by measuring cytokine production of αGC-restricted NK T hybridoma cells. In the absence of parasite glycolipids, αGC stimulated a strong IL-2 response, which was increased at longer pulse periods (Fig. 5 A, bottom). Sulfatide, a known CD1 ligand (42), bound to CD1d and inhibited the αGC-dependent response with increasing concentrations. At prolonged αGC incubation periods, bound sulfatide was efficiently displaced as judged by partial restoration of the NK T cell response. Likewise, Leishmania GIPLs competed with αGC in a dose-dependent manner and were displaced at increasing αGC pulse times. In contrast, LPG abolished the αGC-dependent response even at the lowest concentration and could not be displaced by increasing periods of αGC treatment. These results suggest LPG and GIPLs as potential glycolipid antigens, which bind to CD1d with different affinities. However, LPG binding does not exceed the affinity of αGC, as a threefold molar excess of LPG was necessary to efficiently compete with αGC–CD1d binding when both glycolipids were simultaneously incubated (Fig. 5 B). Also, CD1d-bound αGC activated NK T cells even after subsequent incubation with LPG (Fig. 5 C), suggesting that LPG was unable to displace prebound αGC from CD1d. These data further show that competition occurred only when LPG was able to bind CD1d and, therefore, was independent from nonspecific effects of LPG on NK T cell function or the recognition of the CD1d–αGC complex.

Figure 5.

Binding of LPG to CD1d and competition with αGC. (A) Glycolipid structures (top) and CD1d-binding assay (bottom). Soluble mouse CD1d was incubated with sulfatide (▿), purified L. donovani GIPLs (○), or LPG (•) at the molar ratios indicated. Immobilized complexes were incubated with 200 nM αGC for 20, 40, and 60 min, and αGC-binding was determined by adding NK T cells (hybridoma DN32D3) and measuring IL-2 release after 24 h. (B) Competitive binding assay. Plate-bound CD1d was incubated with 33 nM αGC and increasing amounts of purified LPG. Binding was determined by NK T cell activation as described before. (C) αGC displacement. Plate-bound CD1d was treated with αGC alone (control) or sequentially incubated with LPG and αGC as indicated by the arrowhead. NK T cell activation was determined by IL-2 ELISA. Two independent duplicate experiments were performed, and one representative experiment is shown (mean ± SD). (D) NK T cell activation assay. Murine BM-DCs were incubated with 5 μM of purified L. donovani LPG for 2 h at 37°C and, thereafter, were treated with 100 ng/ml αGC for 12 h. DN34A-1.2 hybridoma cells or splenocytes from naive C57BL/6 mice were added, and IL-2 and IFNγ release were measured in the supernatant 2 d later. Three independent triplicate experiments were performed, and one representative experiment is shown. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Next, we tested if competition of LPG with αGC occurs also in a biologically more relevant setting using antigen-pulsed BM-DCs. Untreated controls and cells treated with 5 μM LPG were pulsed with αGC (37), and NK T hybridoma cells or splenocytes obtained from C57BL/6 mice were added, and NK T cell activation was determined by measuring IL-2 and IFNγ production, respectively. In both cases, treatment with LPG alone did not result in NK T cell activation, indicating that the CD1d–LPG complex was not recognized by these cells, or other lymphocyte populations present in the spleen. In contrast, LPG treatment strongly limited the otherwise robust response of these cells to αGC (Fig. 5 D), suggesting competitive binding of both glycolipids to CD1d in DCs.

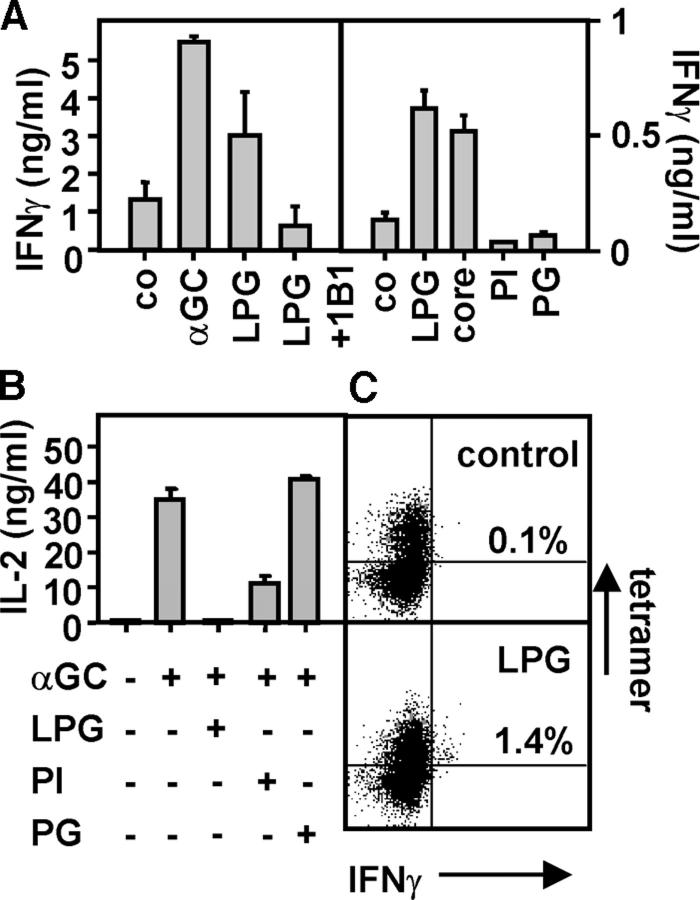

Activation of IFNγ Production by LPG in Naive Liver Lymphocytes through CD1d.

We observed during our in vivo studies that IFNγ is predominantly induced in the infected liver, but absent in spleen (Fig. 3 and not depicted), suggesting the presence of liver-enriched lymphocytes with specificity to Leishmania glycolipids. We tested for the presence of this responsive subset of liver lymphocytes in vitro using LPG-treated BM-DCs. Hepatic lymphocytes from naive mice were incubated with αGC- or LPG-treated BM-DCs in the absence or presence of the CD1d-blocking antibody 1B1. LPG-pulsed BM-DCs induced robust IFNγ at levels that were at least 50% of those induced by αGC-treated cells, and this was reduced to background levels in the presence of anti-CD1d antibody (Fig. 6 A, left).

Figure 6.

Induction of IFNγ in CD1d-restricted T cells by LPG. (A) Activation assay. Murine BM-DCs were treated with αGC and Leishmania glycolipids as described in Fig. 5, and 104 liver lymphocytes from naive C57BL/6 mice were added. Anti-CD1d antibody 1B1 was added as indicated. Core, Gal2GalfMan2GlcN-PI; PI, 1-O-alkyl-2-lyso-phosphatidylinositol lipid anchor, PG, [P-Gal-Man]-phosphoglycan repeats. (B) Competitive binding assay. Plate-bound CD1d was incubated with 33 nM αGC and a 10-fold excess of purified glycolipids. Binding was determined by NK T cell activation as described in Fig. 5. (C) Flow cytometry. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were injected with 50 μg of purified LPG and staining with PeRCP-conjugated anti-CD3ɛ mAb, αGC-loaded PE-conjugated CD1d-tetramers, and FITC-conjugated anti-IFNγ was performed 2 h later. The total lymphocyte population (containing both CD3(+) and CD3(−) cells) is shown. The experiment was performed with three mice per condition, and the number indicates the mean of IFNγ-producing cells in the tetramer positive cell population. One out of two independent experiments performed is shown.

During experimental infection, LPG is released from the surface of the parasite into the host cell where the glycolipid may be processed and intersect with CD1d (4, 43). Therefore, we tested truncated fragments of LPG for their ability to induce an IFNγ response. Significantly, hydrolyzed LPG lacking the [P-Gal-Man] repeats was still able to induce IFNγ in naive liver lymphocytes similar to untreated LPG (Fig. 6 A, right). In contrast, the PI anchor alone was not able to induce a response, despite binding to CD1d and efficient competition with αGC (Fig. 6 B). As expected from the absence of a lipid anchor, the [P-Gal-Man]-phosphoglycan repeats alone had no effect on either IFNγ production or αGC binding. Together, these data further confirmed the CD1d dependence of the IFNγ response to LPG, which required both the lipid and the glycan portion of the molecule. LPG-mediated activation of iNK T cells was further confirmed in vivo in LPG-treated C57BL/6 mice. 2 h after intraperitoneal injection of LPG, ca. 1.4% of tetramer+ iNK T cells isolated from the liver showed IFNγ production (Fig. 6 C), suggesting that LPG, along with related GPI anchors and GIPLs present during Leishmania infection, may contribute to the early antileishmanial immune response.

Discussion

CD1d-deficient mice are susceptible to a variety of microbial pathogens, suggesting glycolipid antigen presentation as an important part of the innate response to infection. Although CD1d binds promiscuously to a variety of microbial lipoglycans (18–21), the immunological significance of this phenomenon has not been established firmly, and no pathogen-associated glycolipid has yet been shown to stimulate a T cell response in the context of CD1d. By using a murine model of visceral leishmaniasis in combination with CD1d-deficient mice, we revealed a requirement for CD1d in the establishment of a protective, Th1-driven granulomatous response, and identified a subset of liver lymphocytes, which showed a CD1d-dependent burst of IFNγ in response to L. donovani infection. Our data support a model whereby Leishmania glycolipids may activate CD1d-restricted T cells, either directly in the context of CD1d or indirectly by induction of altered self-glycolipids, which could participate in the polarization of the early immune response and control parasite burden in the viscera.

Recently, a unique activation mechanism of iNK T cells has been described during infection with Salmonella typhimurium. Brigl et al. (41) demonstrated that the CD1d-dependent response to S. typhimurium did not require recognition of foreign antigens, but was driven by IL-12 produced in response to microbial lipopolysaccharides, which enhanced the recognition of self-glycolipids by autoreactive iNK T cells. A similar scenario could be applicable to the Leishmania-induced activation of CD1d-restricted T cells. Like S. typhimurium, L. donovani induces robust amounts of IL-12 in DCs during visceral infection, which determines the development of the protective Th1 immune response (27, 44–46) and may participate in the activation of iNK T cells (41). However, our data do not fit the S. typhimurium model for several reasons. First, S. typhimurium–induced IL-12 production leads to broad activation of >35% of tetramer+ T cells (41). In contrast, infection with splenic L. donovani amastigotes or cultured promastigotes activated only 3–6% of tetramer+ T cells, even in IL-12–deficient mice (Fig. 4 A). These data rule out a role for this cytokine in early NK T cell activation. However, we cannot exclude a potential effect of other cytokines in this response, although activation by direct cell–cell interaction seems more likely given the small subset of responsive cells. Second, S. typhimurium products were able to activate αGC-responsive canonical iNK T cell clones in vitro. On the contrary, LPG did not activate NK T cell hybridomas or iNK T cells in the spleen, but limited the response of these cells to αGC (Fig. 5). Finally, infection with Leishmania, but not S. typhimurium, was associated with a dramatic decrease of CD1d-reactive T cells, which remained absent for at least 8 wk after infection (Fig. 3). The impact of this altered lymphocyte homeostasis on host immunity and the question, if these cells are depleted by activation-induced cell death or down-regulate the TCR and loose tetramer reactivity is currently under investigation.

Our results are more consistent with a model where components of the Leishmania glycocalyx are recognized by the host immune system and stimulate a CD1d-dependent T cell response. Despite the robust immune response to LPG, and the presence of LPG-responsive T cells in infected mice and patients suffering from visceral leishmaniasis (33, 47–49), presentation of microbial glycolipids by CD1d to NK T cells has not been described in experimental leishmaniasis or any other infection model. Our data, for the first time, link CD1d-dependent antimicrobial immunity during liver infection to the potential presentation of microbial lipoglycans by CD1d. We found that purified Leishmania LPG binds CD1d in vitro (Fig. 5) and induces IFNγ in hepatic lymphocyte preparations from naive mice in a CD1d-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A). Treatment of mice with purified LPG activated a subset of CD1d tetramer+ iNK T cells, but no other lymphocyte population in the liver (Fig. 6 C), ruling out the involvement of other innate immune pathways, such as the toll-like receptors. However, our data do not exclude the possibility that LPG or related glycoconjugates may interact with TLRs in other experimental systems (50, 51). Furthermore, both the glycan and the lipid portions of LPG were required to induce IFNγ in our system, further supporting the model of a CD1d-mediated, TCR-dependent response (Fig. 6 A). Our results are compatible with an alternative model, where Leishmania infection or LPG treatment induces structurally altered endogenous glycolipids similar to tumor gangliosides (52), which may stimulate NK T cells in a CD1d-dependent manner. However, to the best of our knowledge, the presence of altered glycolipids during Leishmania infection has not been described to date.

The phenotype of the responsive NK T cells eludes us so far. These cells are preferentially expressed in the liver and show a polarized IFNγ response (Fig. 3), which is critical for granuloma formation and parasite killing (Figs. 1 and 2). Ablation of the NK T cell response by anti-CD1d antibody blocking experiments strongly reduced IFNγ production in CD3+ and CD3− lymphocytes (Fig. 4) and, hence, Leishmania-responsive NK T cells may modulate early immunity during visceral infection toward establishment of a protective Th1 response. In vivo, these cells react with αGC tetramers and, thus, are considered canonical iNK T, yet Vα14Jα18 NK T hybridoma cells and splenic iNK T cells failed to respond to CD1d-bound LPG. How can we explain this paradoxical result? It is possible that iNK T cell activation during Leishmania infection may be indirect and in response to activation of diverse NK T cells in the liver, which may recognize CD1d-bound microbial or endogenous glycolipid but do not react with αGC-loaded tetramers (CD3+tet− subset; Fig. 4). Alternatively, a subset of iNK T cells may exist in the liver that recognize the glycolipid antigen and are cross-reactive with αGC-loaded CD1d tetramers. αGC activates a heterogenous population of iNK T cells, which show invariant usage of the Vα14 chain, but have a diverse repertoire of Vβ gene segments and may display CDR3 region diversity (9, 10). It is conceivable that some of these iNK T cell subsets may provide specificity to glycolipid antigens other than αGC, which are physiologically more relevant. So far, isolation of these cells using LPG-loaded tetramers has been unsuccessful, possibly because the TCR of the putative LPG-restricted T cells do not recognize full-length LPG but rather a yet unknown processed version of the molecule (Fig. 6 A). During intracellular infection, LPG is shed from the parasite surface into the lumen of the host cell phagosome (4, 43), where it may intersect with the endolysosomal compartment and be processed by various hydrolases and glycosidases for binding to CD1d and TCR recognition. Determining the fine structure of processed LPG in future studies may allow us to identify the putative LPG-reactive T cell population by tetramer staining and elucidate parasite-specific immunodominant glycolipid epitopes. These epitopes may be born on lipoglycans of other pathogens, such as Mycobacterium bovis, Trypanosoma brucei, or pathogenic fungi, providing a molecular pattern for innate immune recognition through CD1d.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Kronenberg for NK T cell hybridoma DN34A-1.2 and A. Bendelac for NK T cell hybridoma DN32D3. We thank G. Eberl and M. Calvo-Calle for critical reading of the text and M. Tsuji for his support.

This work was supported by the STARR Foundation (G.F. Späth), National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant nos. GM07739 (J.L. Amprey) and AI 16963 (H.W. Murray), and NIH/NIAID grants RO1 AI45889 and RO1 AI48933 (to S.A. Porcelli). CD1 tetramers used in this work were produced with support from the Tetramer Core Facility at AECOM supported by NIH/NIAID grant PO1 AI51392. Flow cytometry studies were carried out with assistance provided by the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of the Center for AIDS Research at AECOM.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

J.L. Amprey and J.S. Im contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used in this paper: αGC, α-galactosylceramide; GIPL, glycoinositol phospholipid; iNK, invariant NK; LPG, lipophosphoglycan.

References

- 1.Ashfrord, R., P. Desjeux, and P. Raadt. 1996. Estimation of population at risk of infection and number of cases of Leishmaniasis. Parasitol. Today. 8:104–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turco, S.J., and A. Descoteaux. 1992. The lipophosphoglycan of Leishmania parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:65–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Späth, G.F., L. Epstein, B. Leader, S.M. Singer, H.A. Avila, S.J. Turco, and S.M. Beverley. 2000. Lipophosphoglycan is a virulence factor distinct from related glycoconjugates in the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:9258–9263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Späth, G.F., L.A. Garraway, S.J. Turco, and S.M. Beverley. 2003. The role(s) of lipophosphoglycan (LPG) in the establishment of Leishmania major infections in mammalian hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9536–9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, J., T. Fujiwara, P. Brennan, M. McNeil, S.J. Turco, J.C. Sibille, M. Snapper, P. Aisen, and B.R. Bloom. 1989. Microbial glycolipids: possible virulence factors that scavenge oxygen radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:2453–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjardins, M., and A. Descoteaux. 1997. Inhibition of phagolysosomal biogenesis by the Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. J. Exp. Med. 185:2061–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porcelli, S.A., and M.B. Brenner. 1997. Antigen presentation: mixing oil and water. Curr. Biol. 7:R508–R511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawano, T., J. Cui, Y. Koezuka, I. Toura, Y. Kaneko, K. Motoki, H. Ueno, R. Nakagawa, H. Sato, E. Kondo, et al. 1997. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 278:1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendelac, A., M.N. Rivera, S.H. Park, and J.H. Roark. 1997. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:535–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behar, S.M., and S. Cardell. 2000. Diverse CD1d-restricted T cells: diverse phenotypes, and diverse functions. Semin. Immunol. 12:551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson, S.B., and T.L. Delovitch. 2003. Janus-like role of regulatory iNKT cells in autoimmune disease and tumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakimi, K., L.G. Guidotti, Y. Koezuka, and F.V. Chisari. 2000. Natural killer T cell activation inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 192:921–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dommelen, S.L., H.A. Tabarias, M.J. Smyth, and M.A. Degli-Esposti. 2003. Activation of natural killer (NK) T cells during murine cytomegalovirus infection enhances the antiviral response mediated by NK cells. J. Virol. 77:1877–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chackerian, A., J. Alt, V. Perera, and S.M. Behar. 2002. Activation of NKT cells protects mice from tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:6302–6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza, G., C. de Oliveira, M. Tomaska, S. Hong, O. Bruna-Romero, T. Nakayama, M. Taniguchi, A. Bendelac, L. Van Kaer, Y. Koezuka, and M. Tsuji. 2000. alpha-galactosylceramide-activated Valpha 14 natural killer T cells mediate protection against murine malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:8461–8466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duthie, M.S., and S.J. Kahn. 2002. Treatment with alpha-galactosylceramide before Trypanosoma cruzi infection provides protection or induces failure to thrive. J. Immunol. 168:5778–5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skold, M., and S.M. Behar. 2003. Role of CD1d-restricted NKT cells in microbial immunity. Infect. Immun. 71:5447–5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Procopio, D.O., I.C. Almeida, A.C. Torrecilhas, J.E. Cardoso, L. Teyton, L.R. Travassos, A. Bendelac, and R.T. Gazzinelli. 2002. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucin-like glycoproteins from Trypanosoma cruzi bind to CD1d but do not elicit dominant innate or adaptive immune responses via the CD1d/NKT cell pathway. J. Immunol. 169:3926–3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benlagha, K., A. Weiss, A. Beavis, L. Teyton, and A. Bendelac. 2000. In vivo identification of glycolipid antigen-specific T cells using fluorescent CD1d tetramers. J. Exp. Med. 191:1895–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burdin, N., L. Brossay, Y. Koezuka, S.T. Smiley, M.J. Grusby, M. Gui, M. Taniguchi, K. Hayakawa, and M. Kronenberg. 1998. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: alpha-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates V alpha 14+ NK T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 161:3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joyce, S., A.S. Woods, J.W. Yewdell, J.R. Bennink, A.D. De Silva, A. Boesteanu, S.P. Balk, R.J. Cotter, and R.R. Brutkiewicz. 1998. Natural ligand of mouse CD1d1: cellular glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Science. 279:1541–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overath, P., and D. Harbecke. 1993. Course of Leishmania infection in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Immunol. Lett. 37:13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Z.E., S.L. Reiner, F. Hatam, F.P. Heinzel, J. Bouvier, C.W. Turck, and R.M. Locksley. 1993. Targeted activation of CD8 cells and infection of beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice fail to confirm a primary protective role for CD8 cells in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 151:2077–2086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa, H., H. Hisaeda, M. Taniguchi, T. Nakayama, T. Sakai, Y. Maekawa, Y. Nakano, M. Zhang, T. Zhang, M. Nishitani, et al. 2000. CD4(+) v(alpha)14 NKT cells play a crucial role in an early stage of protective immunity against infection with Leishmania major. Int. Immunol. 12:1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shakarian, A.M., S.L. Ellis, D.J. Mallinson, R.W. Olafson, and D.M. Dwyer. 1997. Two tandemly arrayed genes encode the (histidine) secretory acid phosphatases of Leishmania donovani. Gene. 196:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapler, G.M., C.M. Coburn, and S.M. Beverley. 1990. Stable transfection of the human parasite Leishmania major delineates a 30-kilobase region sufficient for extrachromosomal replication and expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:1084–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray, H.W. 1997. Endogenous interleukin-12 regulates acquired resistance in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1477–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roark, J.H., S.H. Park, J. Jayawardena, U. Kavita, M. Shannon, and A. Bendelac. 1998. CD1.1 expression by mouse antigen-presenting cells and marginal zone B cells. J. Immunol. 160:3121–3127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray, H.W. 2001. Tissue granuloma structure-function in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 82:249–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi, E., K. Motoki, T. Uchida, H. Fukushima, and Y. Koezuka. 1995. KRN7000, a novel immunomodulator, and its antitumor activities. Oncol. Res. 7:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orlandi, P.A., Jr., and S.J. Turco. 1987. Structure of the lipid moiety of the Leishmania donovani lipophosphoglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 262:10384–10391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConville, M.J., T.A. Collidge, M.A. Ferguson, and P. Schneider. 1993. The glycoinositol phospholipids of Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Evidence for the presence of three distinct pathways of glycolipid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 268:15595–15604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McConville, M.J., A. Bacic, G.F. Mitchell, and E. Handman. 1987. Lipophosphoglycan of Leishmania major that vaccinates against cutaneous leishmaniasis contains an alkylglycerophosphoinositol lipid anchor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:8941–8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soares, R.P., M.E. Macedo, C. Ropert, N.F. Gontijo, I.C. Almeida, R.T. Gazzinelli, P.F. Pimenta, and S.J. Turco. 2002. Leishmania chagasi: lipophosphoglycan characterization and binding to the midgut of the sand fly vector Lutzomyia longipalpis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 121:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda, J.L., O.V. Naidenko, L. Gapin, T. Nakayama, M. Taniguchi, C.R. Wang, Y. Koezuka, and M. Kronenberg. 2000. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J. Exp. Med. 192:741–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockinger, B., T. Zal, A. Zal, and D. Gray. 1996. B cells solicit their own help from T cells. J. Exp. Med. 183:891–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naidenko, O.V., J.K. Maher, W.A. Ernst, T. Sakai, R.L. Modlin, and M. Kronenberg. 1999. Binding and antigen presentation of ceramide-containing glycolipids by soluble mouse and human CD1d molecules. J. Exp. Med. 190:1069–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray, H.W., and J. Hariprashad. 1995. Interleukin 12 is effective treatment for an established systemic intracellular infection: experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 181:387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray, H.W. 1999. Granulomatous inflammation: host antimicrobial defense in the tissues in visceral leishmaniasis. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. R.S. J. Gallin, D. Fearon, B. Haynes, C. Nathan, editors. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. pp. 977–994.

- 40.Quinones, M., S.K. Ahuja, P.C. Melby, L. Pate, R.L. Reddick, and S.S. Ahuja. 2000. Preformed membrane-associated stores of interleukin (IL)-12 are a previously unrecognized source of bioactive IL-12 that is mobilized within minutes of contact with an intracellular parasite. J. Exp. Med. 192:507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brigl, M., L. Bry, S.C. Kent, J.E. Gumperz, and M.B. Brenner. 2003. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat. Immunol. 4:1230–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shamshiev, A., H.J. Gober, A. Donda, Z. Mazorra, L. Mori, and G. De Libero. 2002. Presentation of the same glycolipid by different CD1 molecules. J. Exp. Med. 195:1013–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tolson, D.L., S.J. Turco, and T.W. Pearson. 1990. Expression of a repeating phosphorylated disaccharide lipophosphoglycan epitope on the surface of macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani. Infect. Immun. 58:3500–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorak, P.M., C.R. Engwerda, and P.M. Kaye. 1998. Dendritic cells, but not macrophages, produce IL-12 immediately following Leishmania donovani infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engwerda, C.R., M.L. Murphy, S.E. Cotterell, S.C. Smelt, and P.M. Kaye. 1998. Neutralization of IL-12 demonstrates the existence of discrete organ-specific phases in the control of Leishmania donovani. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:669–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guler, M.L., J.D. Gorham, C.S. Hsieh, A.J. Mackey, R.G. Steen, W.F. Dietrich, and K.M. Murphy. 1996. Genetic susceptibility to Leishmania: IL-12 responsiveness in TH1 cell development. Science. 271:984–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moll, H., G.F. Mitchell, M.J. McConville, and E. Handman. 1989. Evidence of T-cell recognition in mice of a purified lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 57:3349–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Handman, E., and G.F. Mitchell. 1985. Immunization with Leishmania receptor for macrophages protects mice against cutaneous leishmaniasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82:5910–5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kemp, M., T.G. Theander, E. Handman, A.S. Hey, J.A. Kurtzhals, L. Hviid, A.L. Sorensen, J.O. Were, D.K. Koech, and A. Kharazmi. 1991. Activation of human T lymphocytes by Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. Scand. J. Immunol. 33:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kropf, P., M.A. Freudenberg, M. Modolell, H.P. Price, S. Herath, S. Antoniazi, C. Galanos, D.F. Smith, and I. Muller. 2004. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to efficient control of infection with the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 72:1920–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Debus, A., J. Glasner, M. Rollinghoff, and A. Gessner. 2003. High levels of susceptibility and T helper 2 response in MyD88-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major are interleukin-4 dependent. Infect. Immun. 71:7215–7218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu, D.Y., N.H. Segal, S. Sidobre, M. Kronenberg, and P.B. Chapman. 2003. Cross-presentation of disialoganglioside GD3 to natural killer T cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]