Abstract

A population of human T cells expressing an invariant Vα24JαQ T cell antigen receptor (TCR) α chain and high levels of CD161 (NKR-P1A) appears to play an immunoregulatory role through production of both T helper (Th) type 1 and Th2 cytokines. Unlike other CD161+ T cells, the major histocompatibility complex–like nonpolymorphic CD1d molecule is the target for the TCR expressed by these T cells (Vα24invt T cells) and by the homologous murine NK1 (NKR-P1C)+ T cell population. In this report, CD161 was shown to act as a specific costimulatory molecule for TCR-mediated proliferation and cytokine secretion by Vα24invt T cells. However, in contrast to results in the mouse, ligation of CD161 in the absence of TCR stimulation did not result in Vα24invt T cell activation, and costimulation through CD161 did not cause polarization of the cytokine secretion pattern. CD161 monoclonal antibodies specifically inhibited Vα24invt T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in response to CD1d+ target cells, demonstrating a physiological accessory molecule function for CD161. However, CD1d-restricted target cell lysis by activated Vα24invt T cells, which involved a granule-mediated exocytotic mechanism, was CD161-independent. In further contrast to the mouse, the signaling pathway involved in Vα24invt T cell costimulation through CD161 did not appear to involve stable association with tyrosine kinase p56Lck. These results demonstrate a role for CD161 as a novel costimulatory molecule for TCR-mediated recognition of CD1d by human Vα24invt T cells.

Keywords: CD1d, CD161, costimulation, Vα24JαQ, T cells

cell subsets which express CD161 (NKR-P1) are found in humans and mice. In rodents there are three NKR-P1 molecules, NKR-P1A, -B, and -C, which are “NK locus”–encoded C-type lectins (1–4). Murine NK1 (NKR-P1C)+ T cells are either CD4+ or double negative (DN)1 and constitutively express a range of additional markers, such as Ly-49C and B220, which are not found on conventional T cells (5–10). They also express a highly restricted TCR repertoire consisting of an invariant Vα14Jα281 α chain in association with a restricted repertoire of Vβ genes (7, 10–12). Genetic and reconstitution studies demonstrated that NK1+ T cells are positively selected by and recognize the MHC-unlinked β2-microglobulin–associated protein, CD1d (5, 6, 11, 13). Of human T cell populations expressing the single known human NKR-P1 molecule, NKR-P1A (CD161), the subset that is analogous to murine NK1+ T cells expresses an invariant Vα24JαQ TCR α chain paired predominantly with Vβ11 (14–20). These human T cells, referred to here as Vα24invt T cells, have been shown to specifically recognize CD1d (19).

TCR-mediated stimulation of human Vα24invt T cells results in simultaneous production of large amounts of both IL-4 and IFN-γ, and hence they have been described as Th0 cells (18–20). Similarly, murine NK1+ T cells can produce large amounts of cytokines, notably IL-4, early in immune responses (9, 21), and a role for NK1+ T cells in promoting Th2 responses has been proposed (22). However, the murine NK1+ T cell population is clearly not essential for all Th2 responses, since β2-microglobulin–deficient mice, which lack detectable NK1+ as well as most CD8+ T cell populations, can still mount such responses (23, 24). CD1d knockout mice, which similarly lack NK1+ T cells, are also able to generate model Th2 responses, such as nonspecific production of IgE (25–27). Murine NK1+ T cells have also been shown to have NK-like cytotoxic activity (8, 9, 12, 28). This NK-like activity is induced by IL-12 (29) and appears to play a role in IL-12–mediated tumor rejection, a Th1-like cell-mediated response (30). Although the precise functions of human Vα24invt T cells remain to be defined, quantitative and qualitative defects in these T cells or the corresponding murine population are predictive of progression in certain human and murine autoimmune conditions (28, 31–35).

It has been established that NK locus–encoded C-type lectins can mediate NK cell activation, and that rodent NK1, but not human CD161, acts as an autonomous NK cell stimulatory structure (3, 4, 36–38). Direct stimulation of murine NK1+ T cells through NK1 rather than the TCR results in a cytokine switch to IFN-γ (13, 39, 40), suggesting that precisely how these cells are activated may contribute to determining the composition of the immune response. In this study, the role of the human NK1 homologue CD161 and other candidate accessory molecules in regulation of human DN Vα24invt T cell responses to CD1d was assessed. The results demonstrated that CD161 functions as a costimulatory receptor for CD1d recognition by Vα24invt T cells. However, in contrast to murine NK1+ T cells, ligation of human CD161 on Vα24invt T cells did not directly activate cytokine secretion, and CD161 costimulation did not result in the selective production of IFN-γ. Our results identify CD161 expressed by Vα24invt T cells as a costimulatory molecule for this unique T cell population.

Materials and Methods

T Cell Clones and Cell Lines.

Vα24invt T cell clones were derived and phenotypic analysis was performed as described (17, 19). In brief, a panel of DN Vα24+Vβ11+ human peripheral blood T cell clones was established by sequential negative magnetic bead (Dynal, Inc., Lake Success, NY) and positive FACS® sorting of human peripheral blood T cells, followed by stimulation with PHA-P (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI) and IL-2 (1.5 nM, equivalent to ∼70 IU/ml; Ajinomoto, Yokohama, Japan) in the presence of irradiated (5,000 rads) peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vα24invt T cell clones were then established by limiting dilution. CD4+ Vα24invt TCR− Vα24+Vβ11+ control T cells were established in a similar manner. Human CD1d-transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and human HLA-A, -B negative C1R B cells (41) were generated as described (19). The murine Vα14invt TCR+ CD1d-specific T-T hybridoma DN32.D3 (7) was provided by Dr. A. Bendelac (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ).

Antibodies.

Antibodies used were anti-Vα24 (C15B2) and anti-Vβ11 (C21D2), both provided by Dr. A. Lanzavecchia (Institute for Immunology, Basel, Switzerland); anti-TCR αβ (BMA031; gift of Dr. R.G. Kurrle, Boehringwerke, Marburg, Germany); anti-CD3 (SPV-T3b [provided by Dr. H. Spits, Netherlands Cancer Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands] and OKT3 [American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD]); anti-CD4 (OKT4; American Type Culture Collection); anti-CD8α (OKT8; American Type Culture Collection); anti-CD8β (2ST8-5H7; provided by Dr. E. Reinherz, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA); anti-CD28 (9.3 [gift of Dr. J. Hansen, Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA] and CD28.2 [PharMingen, San Diego, CA]); anti-CD69 (FN50; PharMingen); anti-CD94 mAb (DX-22 [gift of Dr. L. Lanier, DNAX, Palo Alto, CA], HP-3D9 [PharMingen], HP-3B1 [Coulter Corp., Miami, FL], and IgA NKH3 [provided by Drs. M. Robertson, Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN, and J. Ritz, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA]); anti-CD161 (DX-1 and DX12 [also provided by Dr. Lanier], HP-3G10 [provided by Dr. M. Lopez-Botet, Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, Spain], and 191.B8 [gift of Dr. A. Poggi, Instituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Genoa, Italy]); anti-p40 (NKTA255; provided by Dr. A. Poggi); p38 (C1.7; Coulter Corp.), Fifth Leukocyte Workshop, NK Section, mAb against killer inhibitory receptors p58 (GL183, EB6, CH-L, and HP-3E4) and p70 (DX-9; provided by Dr. Lanier); anti-MHC class I (W6/32; American Type Culture Collection), anti-CD1b (4A7.6.5, IgG2a; gift of Dr. D. Olive, Institut Nationale de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Marseilles, France), and isotype control mAbs (P3, IgG1; MPC-11, IgG2b; American Type Culture Collection); rat anti–murine NK1.1 (PK136; PharMingen); and normal mouse and rat sera. p56Lck was detected with a mixture of antibodies (#42 rabbit serum [provided by Drs. B. Krise and J. Rose, Yale University, New Haven, CT] and 3A5 mAb [Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA]). Multiple independent CD1d-specific mAbs were raised using CD1d–IgG fusion protein as immunogen (reference 19, and S. Porcelli and S. Balk, unpublished). CD1d mAbs were purified from culture supernatants of hybridomas grown in medium supplemented with ultra-low IgG fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) by protein G (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) chromatography. Fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–murine IgG antibody was obtained from DAKO Corp. (Carpinteria, CA) and Biosource International (Camarillo, CA).

Functional Analysis of T Cells.

For activation of T cells (105/ well), anti-CD3 mAb OKT3 was bound overnight in PBS (50 μl/well) to 96-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plates, and unbound antibody was washed off. Coating mAb concentrations were 1 μg/ml OKT3 for subsequent incubations with no PMA and 0.1 μg/ml for incubations with PMA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 1 ng/ml, unless otherwise indicated. Plate-bound (50 μl/well) or soluble costimulatory mAbs at 10 μg/ml or indicated concentrations were then added for at least 4 h. Subsequently, rested T cells at 2–4 wk after PHA stimulation were incubated with plate-bound mAb and IL-2 at 0.3 nM. In the case of soluble mAb, an equal amount of cross-linking anti–murine IgG antibody was added after the T cells had been allowed to settle on the limiting plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb. For CD1d responses, equal numbers of CD1d+ human C1R B cell transfectants or control mock-transfected C1R cells were incubated with the rested T cells, PMA (1 ng/ml unless otherwise stated), and IL-2 at 0.3 nM, as described previously (19).

Released cytokine levels at 48 h were determined in triplicate by ELISA with matched antibody pairs in relation to cytokine standards (PharMingen; Endogen, Inc., Cambridge, MA) and converted to nanograms or picograms per milliliter using the Softmax program (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Similarly, T cell proliferation between 48 and 72 h was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation (1 μCi/well), using target cells pretreated with mitomycin C (0.09 mg/ml) for 1 h. Results are shown with SEM.

Cytolytic activity of Vα24invt T cells was assessed by conventional 51Cr-release assays as described previously (42, 43). The assay was performed during the T cell growth phase 7–14 d after PHA stimulation. Spontaneous, specific, and total (Triton X-100) 51Cr released at 4 h were measured.

Assessment of Protein Interactions of NK Locus Molecules.

Interaction of membrane and cytosolic proteins was assessed as described previously (44). In brief, Vα24invt T cell clone DN2.B9 or the murine Vα14invt TCR+ CD1d-reactive T-T hybridoma DN32.D3 was lysed with 1% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline with protease inhibitors. Specific and associated proteins were precipitated with Con A agarose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.) or antibodies prebound to protein A/G bead mixture (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). After washing, bound material was eluted under nonreducing conditions for C-type lectin Western blotting. Protein analyzed by SDS-PAGE was blotted onto nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) and probed with antibodies. mAb HP-3G10 reacted in Western blotting with nonreduced CD161 (80-kD band). No activity was detected with the reduced antigen or with other CD161 mAbs in Western blots. p56Lck was immunoblotted with #42 serum and 3A5, followed by second antibody–peroxidase conjugates (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and chemiluminescence detection (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.).

Results

Potent Costimulation of Vα24invt T Cells by CD161 mAb.

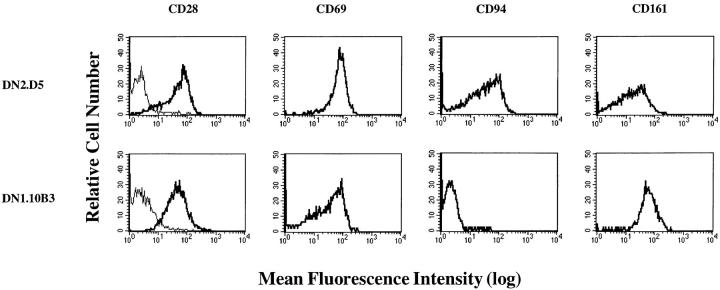

Human Vα24invt T cells express high levels of CD161 and variable levels of other members of the NK locus C-type lectin family (14–20). FACS® profiles of two representative Vα24invt T cell clones, DN2.D5 and DN1.10B3, are shown in Fig. 1. CD161 (NKR-P1A) was strongly expressed by these two clones derived from two different donors (Fig. 1), as well as by all of six additional CD1d- reactive Vα24invt T cell clones (19). CD69, another C-type lectin encoded in the NK locus, was also expressed by all of the Vα24invt T cell clones (Fig. 1; reference 19). Although transiently expressed after activation of conventional T cells, CD69 showed prolonged expression on Vα24invt T cell clones for at least several months after PHA stimulation (data not shown). CD94, a third NK locus–encoded C-type lectin, was expressed by seven out of eight Vα24invt T cell clones (not DN1.10B3; Fig. 1). Analysis of other potential Vα24invt T cell accessory molecules showed that p40 (45) and p38 C1.7 proteins (46), both previously found on NK cells and some cytolytic T cells, were expressed by some Vα24invt T cell clones. However, these molecules were also found on several control Vα24+ noninvariant cells and other T cell clones not belonging to this subset (data not shown). Vα24invt T cells had variable expression of CD28, from barely detectable on some clones to levels comparable to conventional T cells (Fig. 1, and data not shown). Finally, as shown previously, the Vα24invt T cells did not express the NK cell–associated p58 or p70 killer inhibitory receptors or the other NK cell markers CD16, CD56, and CD57 (19). Thus, established CD1d-reactive Vα24invt T cell clones were consistently CD161+CD69+, with more variable expression of other candidate accessory molecules.

Figure 1.

Expression of NK cell–associated proteins by Vα24invt T cells. Representative FACS® analysis of DN Vα24invt T cell clones DN2.D5 (top) and DN1.10B3 (bottom) ∼3 wk after stimulation with PHA and irradiated feeders. T cells were stained with mAb against the antigens shown and with anti-IgG FITC conjugate before gating on live cells. Left to right, Normal mouse serum (outline) and CD28 (solid line); CD69; CD94; CD161.

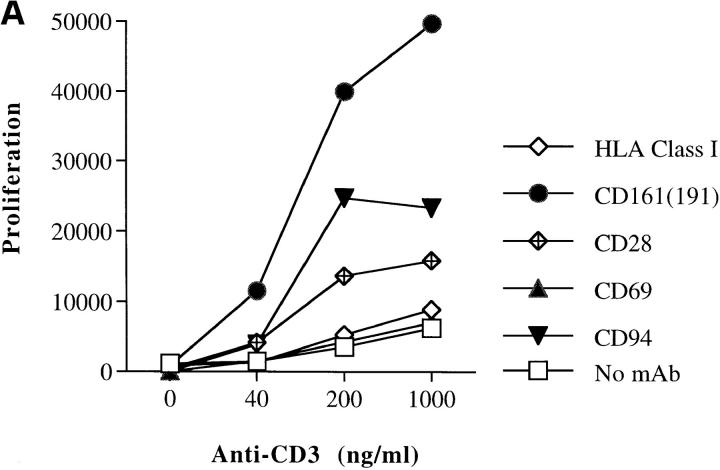

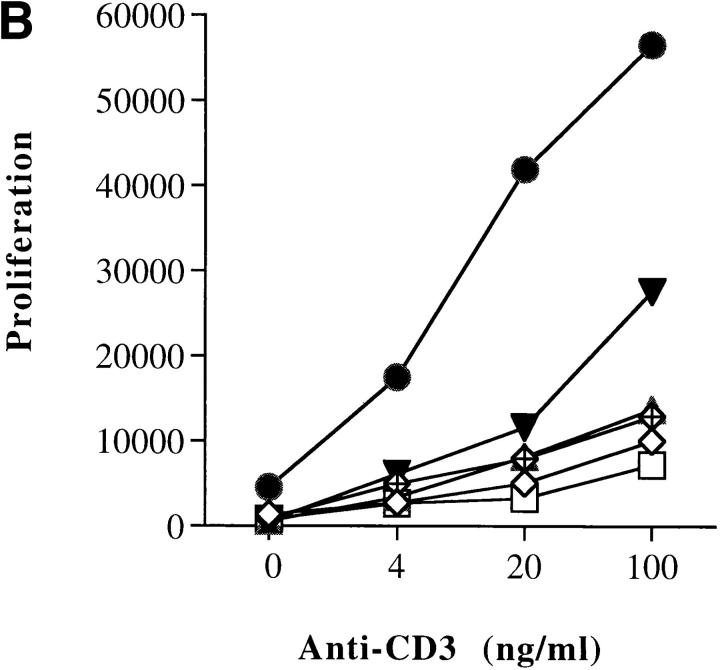

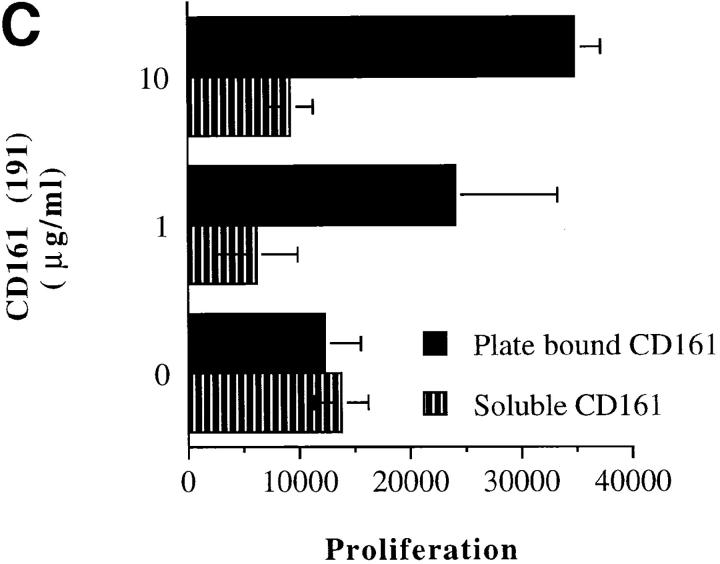

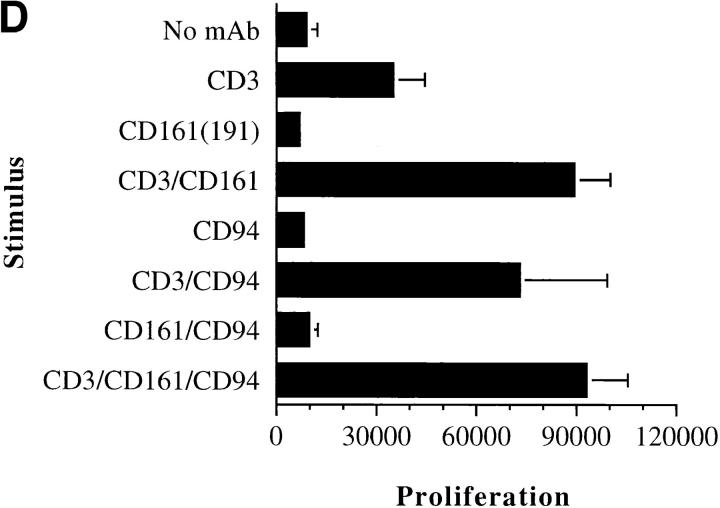

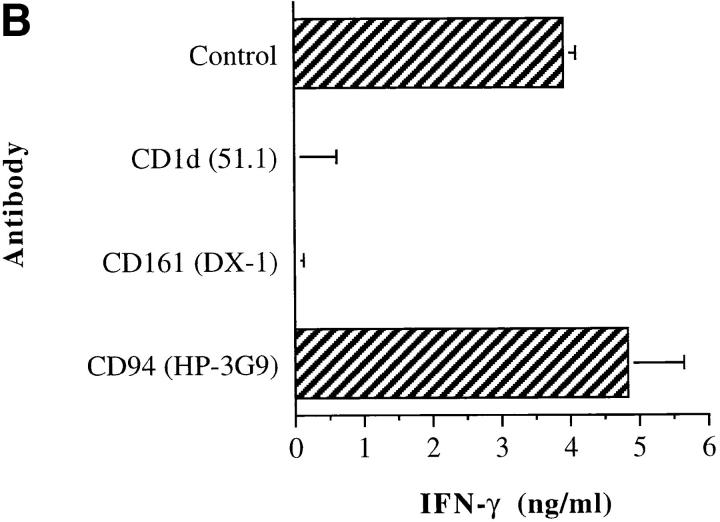

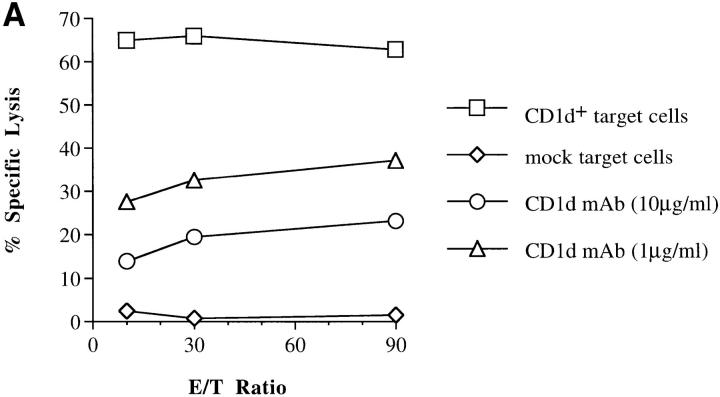

Ligation of murine NK1 (NKR-P1C) alone activates murine NK1+ T cells and, in contrast to TCR stimulation, results in an exclusively IFN-γ–secreting Th1-biased phenotype (13, 39, 40). Therefore, we examined the effect of direct ligation of CD161 on stimulation and costimulation of human Vα24invt T cells. Proliferative responses were measured in the presence of appropriate suboptimal concentrations of immobilized CD3 mAb. Proliferation of all Vα24invt T cell clones tested (DN2.D5, DN2.D6, DN2.D7, and DN1.10B3) and the Vα24invt T cell line DN2.Vβ11+ was substantially augmented by CD161 mAbs 191.B8 (47) and DX-1 (36) in the absence of PMA (Fig. 2 A, and data not shown). With the addition of phorbol ester, which is required for activation of these cells by CD1d+ targets in vitro (19), similar costimulation by CD161 ligation was also observed (Fig. 2 B). PMA lowered the concentrations of CD3 mAb required ∼10-fold (Fig. 2, A and B). Under both conditions, costimulation of Vα24invt T cells by CD161 was readily seen over a 25-fold range of anti-CD3 mAb concentrations (Fig. 2, A and B). Optimal costimulation via plate-bound CD161 required >1 μg/ml 191.B8 coating mAb and was not seen with soluble 191.B8, even at up to 10 μg/ml in the presence of a soluble cross-linking secondary antibody (Fig. 2 C). In no experiment was proliferation by human Vα24invt T cell clones observed in response to plate-bound CD161 mAb in the absence of CD3 mAb (Fig. 2, A, B, and D; Table 1; and data not shown). Similar lack of direct stimulation was observed using two different CD161 mAbs (DX-1 and 191.B8) at concentrations up to 20 μg/ml (Fig. 2, Table 1, and data not shown).

Figure 2.

Costimulation of Vα24invt T cells by NK locus–encoded C-type lectins. CD161+CD94+ Vα24invt T cell clone DN2.D6 (105/well, 2–4 wk after restimulation, except where shown) was stimulated with limiting quantities of plate-bound CD3 mAb (OKT3 at 1 μg/ ml without PMA, or 0.1 μg/ml with PMA at 1 ng/ml as shown) and/or plate-bound or soluble accessory mAb (10 μg/ml, except as shown). For soluble mAb, cross-linking anti-IgG was also added at molar equivalence. T cell proliferation measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation (cpm) was determined in triplicate at 72 h (SEM shown). Similar results were obtained by IL-4 and IFN-γ cytokine ELISA at 48 h (not shown). (A and B) Titration of anti-CD3 mAb in the presence of 10 μg/ml potential accessory molecule antibodies without (A) or with (B) PMA. (C) Titration of soluble and plate-bound CD161 costimulatory mAb 191.B8 with 0.1 μg/ml anti-CD3 mAb and PMA. (D) 1.0 μg/ml anti-CD3 mAb and/or 10 μg/ml CD161 and/or CD94 costimulation; no PMA. (E) Partially rested T cells at only 9 d after restimulation, with 1.0 μg/ml anti-CD3 mAb, 10 μg/ml CD161 and/or CD94 costimulation, and no PMA, or with PHA only.

Table 1.

Comparison of Vα24invt T Cell Responses to Mitogenic Antibody and CD1d

| Stimulus | Proliferation | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IL-4/IFN-γ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 8,951 | <100 | <100 | — | ||||

| CD3 | 35,077 | 3,320 | <100 | — | ||||

| CD161 | 6,930 | <100 | <100 | — | ||||

| CD3/CD161 | 89,525 | 10,670 | 734 | 0.069 | ||||

| CD94 | 8,199 | <100 | <100 | — | ||||

| CD3/CD94 | 73,020 | 8,963 | 497 | 0.055 | ||||

| CD161/CD94 | 9,824 | <100 | <100 | — | ||||

| CD3/CD161/CD94 | 93,072 | 11,250 | 626 | 0.056 | ||||

| C1R CD1d | 27,133 | 41,080 | 916 | 0.022 |

CD161+ Vα24invt T cell clone DN2.D6 (105cells/well) was stimulated with limiting quantities of plate-bound CD3 mAb (0.1 μg/ml; 1 ng/ml PMA) and plate-bound (10 μg/ml) accessory mAb (CD161 191.B8 or CD94 HP-3D9) as in Figs. 2 and 3. In the same experiment, additional DN2.D6 cells were stimulated with live CD1d+ C1R cell transfectants (105/well; 1 ng/ml PMA) as in Fig. 4. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments where both plate-bound and CD1d responses were measured in parallel. [3H]Thymidine incorporation was determined in triplicate at 72 h, shown as cpm. IL-4 and IFN-γ cytokine ELISA (pg/ml) were determined at 48 h. Cytokine detection limits were <100 pg/ml. —, Cytokine ratios not calculable due to undetermined cytokine levels below detection limits.

As with proliferative responses, and unlike in the mouse, there was no IL-4 or IFN-γ secretion by human Vα24invt T cell clones in response to plate-bound CD161 mAb in the absence of CD3 mAb, either in the presence or absence of PMA (Fig. 2 D, Table 1, and data not shown). However, both IL-4 and IFN-γ production by Vα24invt T cell clones induced by limiting anti-CD3 mAb were substantially augmented by CD161 mAbs 191.B8 and DX-1 in both the presence and absence of PMA (Table 1, and data not shown). Antibody-mediated CD161 ligation did not alter the pattern of cytokines produced by suboptimal TCR stimulation. IL-4 to IFN-γ secretion ratios between the CD161-costimulated and CD1d-specific responses varied by only approximately threefold, and indicated that there was no polarization of cytokine secretion toward IFN-γ production induced by CD161 costimulation of the human Vα24invt T cells (Table 1).

Similarly to CD161 mAb, CD94 mAb HP-3D9 also produced significant costimulation of Vα24invt T cell proliferation (Fig. 2, A and B) and IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion (Table 1) in both the absence and presence of PMA. Vα24invt T cell clone DN1.10B3, which expressed CD161 but no detectable cell surface CD94 (Fig. 1 A), was strongly costimulated by CD161 mAb, but not by CD94 mAb (not shown). However, as with CD161, there was no direct activation of Vα24invt T cell proliferation or cytokine secretion through CD94 alone or in combination with CD161, using several different antibodies (Fig. 2, A, B, and D; Table 1; and data not shown). In no case was synergistic or even additive costimulation of proliferation by CD161 and CD94 mAbs seen (Fig. 2 D, and Table 1), and in no case was significant alteration of cytokine secretion observed with simultaneous addition of both mAbs (Table 1). This was true even at lower levels of CD3 mAb and suboptimal levels of costimulation of proliferation by more recently activated Vα24invt T cells (Fig. 2 E). Anti-CD28 mAb (CD28.2), which potently costimulated control conventional T cell clones (not shown), showed only weak costimulation of the proliferation and cytokine secretion of the CD28+ Vα24invt T cell clones, and only in the absence of PMA (Fig. 2, A and B). Anti-p40 mAb NKTA255 was also costimulatory for Vα24invt T cells, but only in the absence of PMA (not shown). CD69 mAb (Fig. 2, A and B), p38 C1.7 mAb (not shown), MHC class I mAb, and isotype-matched nonbinding control mAb had no costimulatory or direct stimulatory activity (Fig. 2, A and B, and data not shown). Therefore, human Vα24invt CD1d-reactive T cells differed from their murine counterparts in lack of direct activation in response to CD161, or indeed, other C-type lectin ligation, whereas both CD161 and CD94 mAbs were specifically costimulatory.

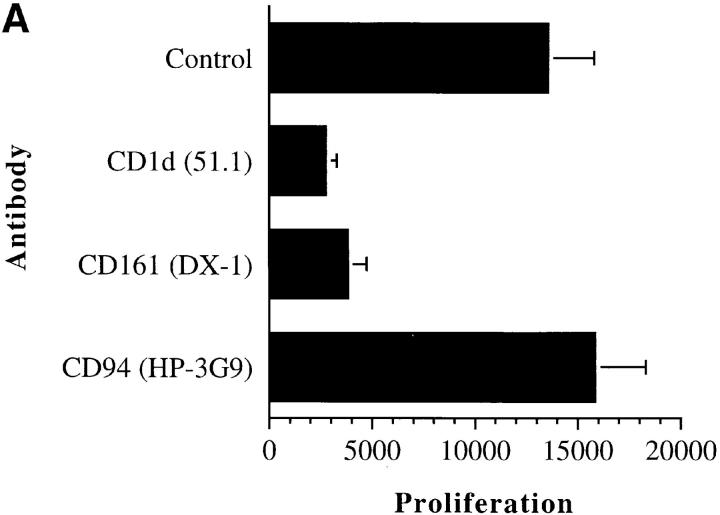

Role of CD161 in CD1d-dependent Activation of Vα24invt T Cells.

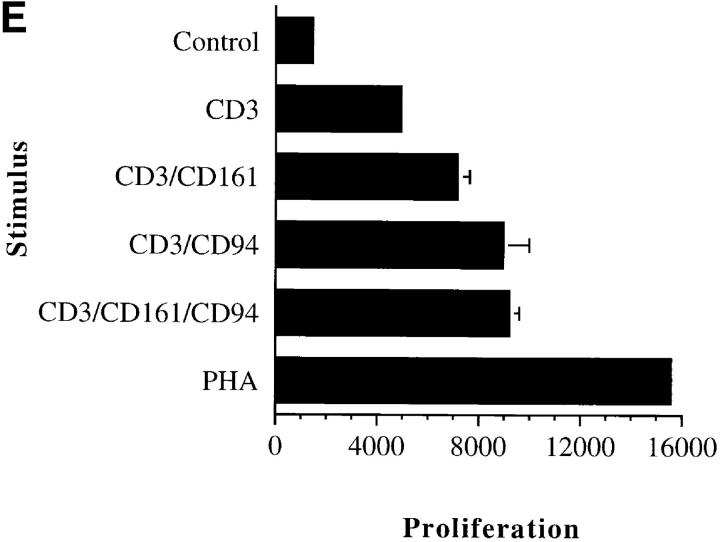

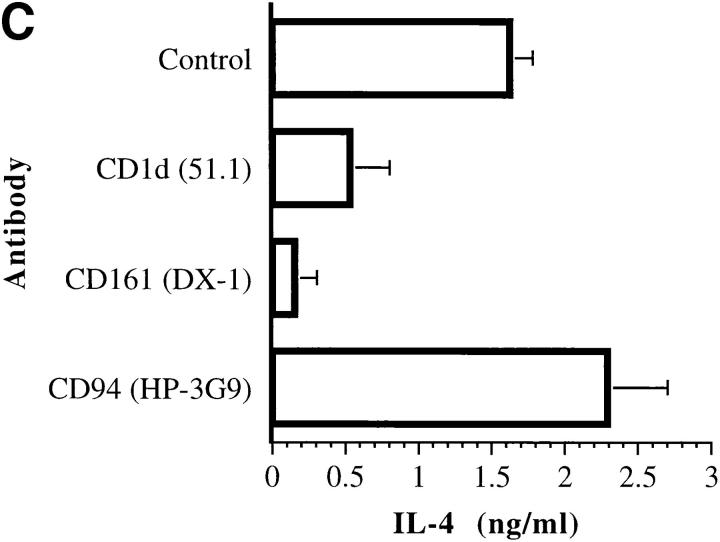

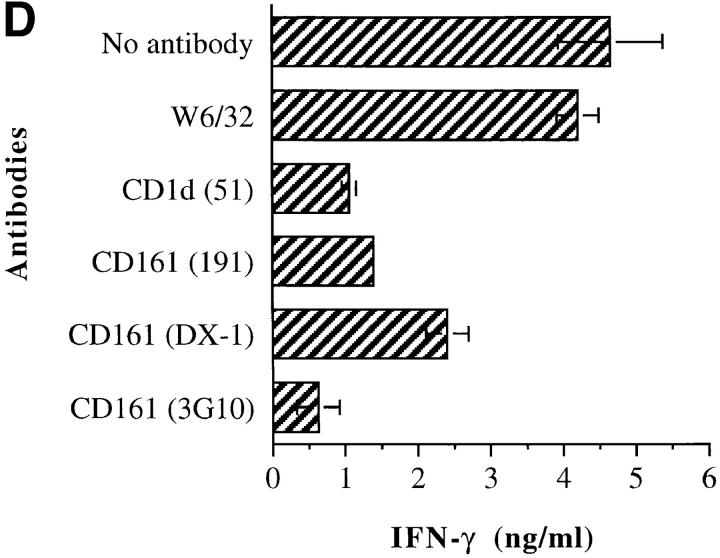

Since CD1d is a natural ligand of Vα24invt T cells, it was important to determine whether CD161 or other molecules contributed to T cell activation in response to CD1d+ target cells. Vα24invt T cells were incubated with CD1d transfectants, and proliferation and cytokine responses were measured. Recognition of CD1d+ human B cell transfectants by Vα24invt T cells, measured as proliferation, or IFN-γ or IL-4 cytokine secretion, was inhibited by CD1d mAbs 51.1 (Fig. 3, A–C) and 42.1 (not shown). Proliferation in response to CD1d was comparably inhibited with CD161 mAb DX-1 (Fig. 3 A). Similarly, secretion of both IFN-γ and IL-4 was inhibited by CD161 mAb DX-1 (Fig. 3, B and C). Each of three different CD161 mAbs tested inhibited proliferative and cytokine secretion responses to CD1d recognition, with HP-3G10 consistently the most potent, followed by 191.B8, and then DX-1 (Fig. 3, D and E, and data not shown). Inhibition of proliferation and cytokine secretion in response to CD1d by CD161 mAb was seen over a wide range of PMA concentrations (0.05–5 ng/ml; Fig. 3, and data not shown) and not just under suboptimal conditions (<1 ng/ml PMA).

Figure 3.

CD1d and CD161 mAbs specifically inhibit Vα24invt T cell response to CD1d. Vα24invt T cells (105/well) were stimulated with mitomycin C–treated CD1d+ C1R cell transfectants (105/well) and 1 ng/ml PMA. Control, CD1d-specific, and other mAbs were included in incubations at 10 μg/ ml. Representative results from five independent experiments are shown. (A) DN2.D6 T cell proliferation (cpm) was determined in triplicate at 72 h. (B) IFN-γ cytokine ELISA was determined at 48 h from the same experiment as in A. (C) IL-4 determined as for IFN-γ. Control mock C1R-containing wells had background proliferation of 6,000 cpm, 6.4 ng/ml IFN-γ, and 2.4 ng/ml IL-4. In a further experiment with two Vα24invt T cell clones, three different CD161 mAbs were used. (D) DN2.D6. (E) DN2.D5.

In contrast to these results with CD161 mAb, the costimulatory CD94 mAb HP-3D9 did not inhibit T cell proliferation or cytokine secretion in response to CD1d (Fig. 3, A–C). Other mAbs specific for CD94 (DX-22 and HP-3B1), CD69 (FN50), p38 (C1.7), and the weakly costimulatory p40 mAb (NKTA255) had no consistent inhibitory effect on CD1d-dependent T cell proliferation or cytokine secretion (not shown). The HLA class I control mAb (W6/32) had a small inhibitory effect (Fig. 3, D and E), which was also seen using CD1d+ CHO cells as targets (not shown). Since the class I mAb does not bind to cells of hamster origin, this result appears to reflect mAb binding directly to the T cells in the assay.

Involvement of molecules other than CD1d on the target cell and CD161 on the T cell was tested by incubation with mAbs against various molecules preferentially expressed on resting and activated B and/or T cells. mAbs against CD19, CD20, CD22, CD23, CD24, CD25, or CD28 did not affect activation of invariant TCR+ T cells by CD1d+ B cells, whether measured as proliferation, or IFN-γ or IL-4 secretion (not shown). Consistent with lack of effect of CD28 mAb, CTL-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4)–Ig fusion protein, which blocks both B7-1 and B7-2 costimulation, had no significant effect on CD1d-dependent T cell stimulation (S.B. Wilson, personal communication). Therefore, of the molecules studied, only CD1d itself and CD161 were found to contribute to Vα24invt T cell responses to CD1d+ target cells.

Lack of CD161 Dependence of CD1d-specific Cytolysis by Vα24invt T Cells.

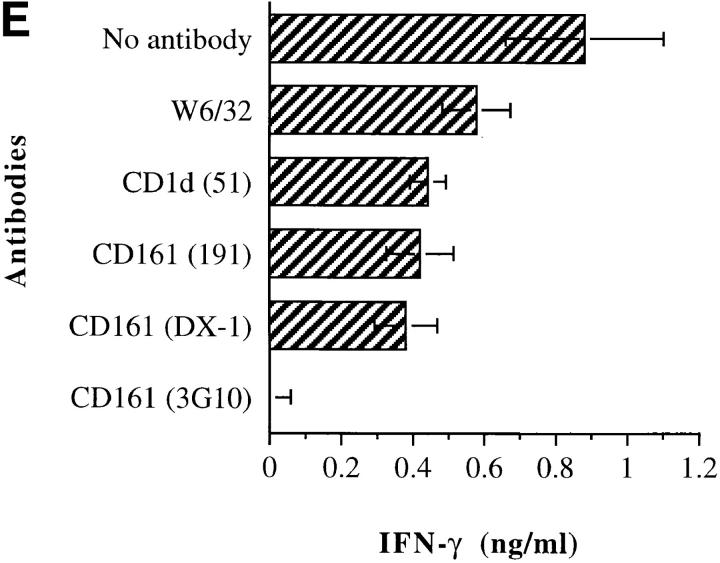

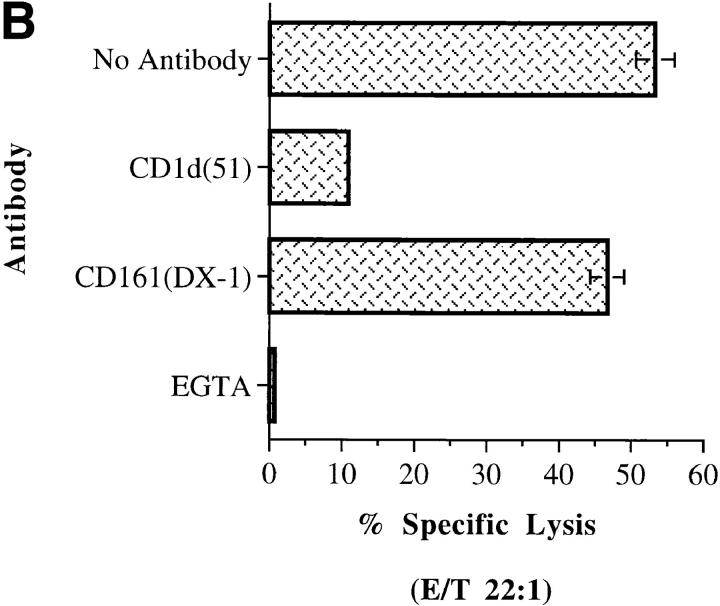

Recently activated Vα24invt T cell clones displayed potent and specific cytolytic activity against C1R CD1d+ transfectants (Fig. 4). Vα24invt T cell clones induced 20–70% of maximal 51Cr release from CD1d+ C1R cells at E/T ratios of 10:1 (Fig. 4 A, and data not shown). Cytotoxicity of the same T cell clones against C1R mock transfectants was <10% at these E/T ratios, demonstrating CD1d specificity of cytolysis. As seen for proliferative and cytokine secretory responses above, the CD1d-specific cytolytic effector response of the T cell clones was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by CD1d-specific mAbs 42.1 and 51.1. These CD1d mAbs had an IC50 of ∼1 μg/ml (Fig. 4 A) and could reduce cytolysis to nearly background levels at higher concentrations of mAb (Fig. 4, A and B). This confirmed that cytolytic activity, like proliferation and cytokine secretion, was a response to the intact CD1d molecule. The cytolytic activity of Vα24invt T cells was abolished by EGTA, indicating a Fas-independent mechanism requiring release of cytolytic granules (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Cytolytic responses of Vα24invt T cells to CD1d+ target cells. Vα24invt DN2.D6 T cells were stimulated with 51Cr-loaded CD1d+ or mock C1R cell transfectants. (A). E/T ratio titration. CD1d (51.1) antibody inhibition of target cell lysis (1 and 10 μg/ml). (B) Antibody inhibition of target cell lysis. CD1d (51.1) at 10 μg/ml or CD161-specific mAb (DX-1) with 51.1 at 0.08 μg/ml were included in incubations.

To determine the role of CD161 in cytolytic activity, CD161 mAbs were also included. No effects of any of the three CD161 mAbs on CD1d-specific cytolytic activity were seen at up to 10 μg/ml. This was true even when a limiting amount of CD1d mAb (0.08 μg/ml) was included to amplify any inhibition (Fig. 4 B), after preliminary experiments showed no inhibition by CD161 alone. Cytolytic responses were also PMA-independent. These results demonstrated that costimulatory pathways activated by CD161 ligation and PMA were not required for CD1d-specific cytolytic activity of Vα24invt T cells. These observations parallel conventional CTLs, for which costimulatory molecules such as CD28 are not required to induce cytolysis by recently activated T cells.

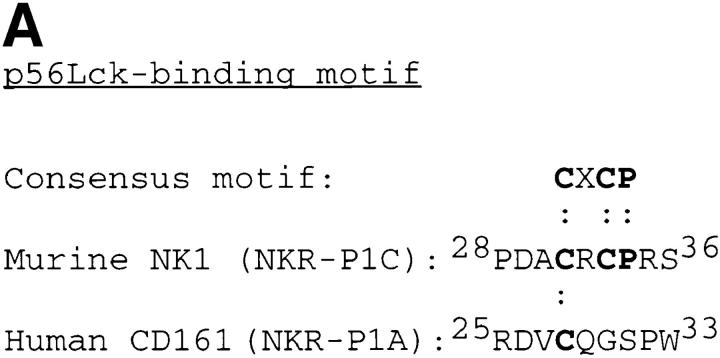

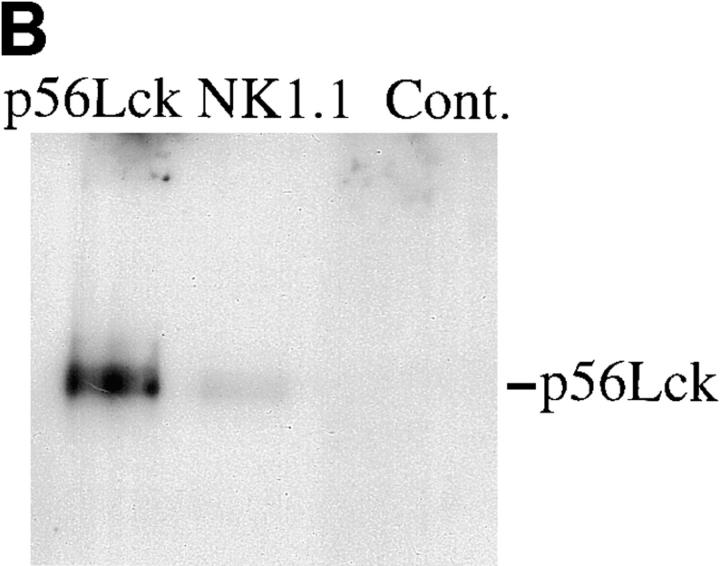

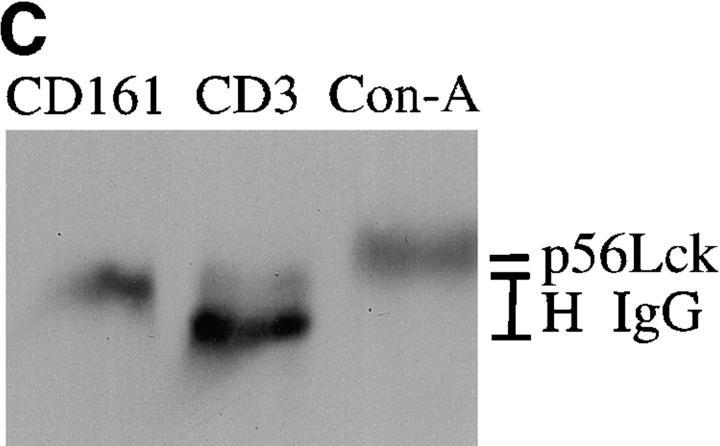

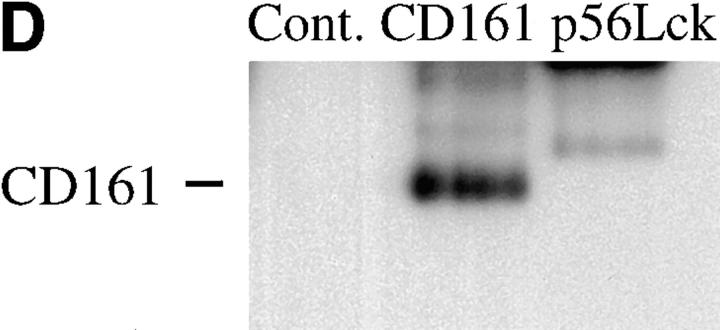

Lack of Association of Vα24invt T Cell p56Lck and Human CD161.

Because DN Vα24invt T cells lack CD4 and CD8αβ, which are essential for physiological activation of conventional T cells through p56Lck, an association between Vα24invt T cell p56Lck and certain accessory molecules might be expected. Association between murine NK1 and p56Lck has been described (48), but human CD161 (36) does not contain the cytoplasmic tail p56Lck binding motif found in CD4 and CD8 (49) and in all of the murine NKR-P1 molecules (1) (see Fig. 5 A). Therefore, we directly tested for interaction of CD161 with Vα24invt T cell p56Lck by immunoprecipitation and subsequent Western blotting.

Figure 5.

Association of p56Lck with murine NK1, but not human Vα24invt T cell CD161. (A) Comparison of human (reference 36) and murine NKR-P1 (references 1 and 2) amino acid sequences around the functional p56Lck binding motif (reference 47) found in murine NKR-P1C. (B) p56Lck immunoblot of nonreduced murine p56Lck, NK1.1, and control immunoprecipitations from Vα14invt T-T hybridoma DN32.D3. (C) p56Lck immunoblot of CD3, CD161, and Con A precipitations from Vα24invt T cell clone DN2.B9. (D) CD161 (HP-3G10) immunoblot of nonreduced p56Lck, CD161 (DX-1), or control mAb (Cont.) immunoprecipitations from Vα24invt T cell clone DN2.B9.

In preliminary experiments, it was confirmed that murine NK1+ T cell hybridoma DN32.D3 (7) did show association of NK1.1 with p56Lck (Fig. 5 B). Human p56Lck was also expressed by DN Vα24invt T cells, and Con A precipitation of Triton X-100 lysates followed by Western blot showed that p56Lck was constitutively associated with glycoprotein(s) (Fig. 5 C). However, CD161 immunoprecipitates did not contain detectable p56Lck (Fig. 5 C). Furthermore, in the reciprocal experiment in which Triton X-100 lysates were immunoprecipitated with p56Lck antibody and immunoblotted with CD161 mAb, there was also no detectable association of CD161 with p56Lck (Fig. 5 D). We conclude that p56Lck was not stably associated with CD161 in Vα24invt T cells. Taken together, the results presented support the model that human CD161 functions as a novel costimulatory molecule for human Vα24invt T cells.

Discussion

CD161+ Vα24invt T cells are likely to play an important immunoregulatory role (28, 31–35), presumably through interactions with CD1d+ target cells (19). However, it is unclear how activation and effector functions of this T cell population in response to CD1d recognition are regulated. By analogy with conventional MHC-restricted T cells, it appears likely that activation of Vα24invt T cells is regulated by the engagement of accessory molecules on the T cell surface by specific ligands expressed by appropriate target cells. In the absence of CD4 and CD8αβ and with highly variable levels of CD28, therefore, CD161 and other related molecules were investigated as potential costimulatory or accessory molecules for Vα24invt T cells. The results reported here indicate that CD161–ligand interactions positively regulate CD161+ Vα24invt T cell activation.

CD161, the single known human NKR-P1 molecule, which was first characterized on NK cells and some T cell populations (36), is expressed at high levels by Vα24invt T cells (18–20). In contrast to results in the mouse (39), anti-CD161 mAb did not directly activate human Vα24invt T cells. However, activation with limiting quantities of anti-CD3 mAb revealed costimulatory activity of CD161 ligation for CD1d-reactive Vα24invt T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion. Phorbol ester lowered the threshold for CD3 activation, but did not substitute for CD161 costimulation, implying that the latter activity was not solely protein kinase C–dependent. Furthermore, unlike with murine NK1+ T cells, CD161 ligation did not alter the pattern of cytokines produced by Vα24invt T cells. Antibody-mediated blocking showed that CD161 costimulation was necessary for CD1d-dependent Vα24invt T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion, as both of these activities were specifically inhibited by all three CD161 mAbs tested. Thus, a direct role was demonstrated for CD161 in the response of Vα24invt T cells to a physiological ligand, CD1d.

Other NK locus–encoded C-type lectin molecules, CD69 and CD94, were also expressed by most but not all (in the case of CD94) of the Vα24invt CD1d-reactive T cell clones derived from two individual donors. CD94 expression by Vα24invt T cells appears to be variable between donors, and may be relatively uncommon in vivo (18). The Vα24invt T cell clones in this study retained expression of CD69 up to 4 mo after stimulation. CD69 expression of freshly isolated Vα24invt T cells from several donors was low (18), and might also be elevated by in vitro culture. Alternatively, expression may vary between different donors, since multiple independently raised Vα24invt T cell clones from additional donors were also constitutively CD69+ and variable with respect to CD94 expression (S.B. Wilson, personal communication). Conversely, another NK cell marker, CD56, may be expressed on Vα24invt T cells in situ (20), although it is absent from the established clones we have studied (19).

Those Vα24invt T cells that expressed CD94 showed costimulation with CD94 mAb. An mAb against a third recently cloned molecule, p40 (45, 50), was mildly costimulatory in the absence of PMA for both Vα24invt and control T cells expressing this antigen. Similarly, CD28, the classic costimulatory molecule of conventional T cells, was consistently only weakly costimulatory on CD28+ Vα24invt T cells in the absence of PMA, and had no detectable effect in the presence of PMA. In contrast to the results with CD161, neither CD94, p40, nor several other candidate accessory molecules tested appeared central to Vα24invt T cell activation in response to CD1d. None of the three CD94 mAbs tested had consistent effects on CD1d-dependent Vα24invt T cell proliferation or cytokine secretion. CD28 mAb did not block CD1d-dependent Vα24invt T cell responses, even of those clones that expressed significant levels of this molecule. Furthermore, CTLA4–Ig fusion protein did not block CD1d-dependent T cell activation (S.B. Wilson, personal communication). However, the requirement for PMA in the CD1d recognition assay suggests that additional costimulatory signals must be provided concurrently with CD161 ligation for activation of resting Vα24invt T cells in response to CD1d. It is known that human CD1b- and CD1c-restricted T cells use a CD28-independent costimulatory pathway (51), and this appears to be independent of CD161 (M. Exley and S. Porcelli, unpublished observations).

The primary effector function associated with Vα24invt T cells has been production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Murine hepatic NK1+ T cells have also been shown to have NK-like cytolytic activity (29), but whether they can mediate CD1d-restricted cytolysis has not been determined. Furthermore, murine NK1+ T cells directly mediate antitumor effects through a cytotoxic mechanism that appears to be CD1d-independent (30). This report demonstrates that an additional effector function for human Vα24invt T cells is direct CD1d-restricted cytolysis. The major mechanism of this effector activity appears to be cytolytic granule release, based on Ca2+ dependence. Significantly, this activity was PMA-independent and was not affected by CD161 mAb. These results likely reflect the less stringent requirements for triggering of the cytolytic effector function of activated T cells than for full activation of resting cells. The inability of CD161 mAb to block cytolytic activity provides evidence against CD161 functioning as a coreceptor for CD1d recognition, analogous to the role of CD4 and CD8, since CD8 mAb routinely inhibits conventional cytolytic T cells. In contrast, this suggests a parallel with other costimulatory molecules such as CD28, which are not required for cytotoxic T cell lysis of target cells. Alternatively, the Vα24invt TCR could have very high affinity for CD1d, which can eliminate the need for coreceptor ligation for cytolysis, as has been described for some CD8-independent cytolytic T cells (52).

To further assess how CD161 contributes to activation of Vα24invt T cells, association between CD161 and p56Lck was assessed. Rodent NKR-P1C (NK1) is directly stimulatory for both NK cells and NK1+ T cells (3, 13, 39, 40) and can associate with p56Lck via a cytoplasmic tail motif CXCP/S/T (47), as used by CD4 and CD8 (48). However, human CD161 does not contain this motif, and mAbs against this molecule do not directly activate nor do they block classical human NK cell cytolysis (36). Human Vα24invt T cell CD161 did not detectably associate with p56Lck using detergent conditions (1% Triton X-100), which readily confirmed the murine NK1.1–p56Lck interaction. Based on lack of association of human CD161 with Vα24invt T cell p56Lck, and by functional analogy with the classical costimulatory molecule CD28, we propose that human CD161 ligation results in activation of another signaling molecule. Interestingly, the response of Vα24invt T cells to CD1d transfectants in vitro is PMA-dependent, and CD161 can still provide a costimulatory signal in the presence of PMA, suggesting that the CD161 costimulatory signal does not depend solely on classical protein kinase C molecules. Murine NK1 also associates with the FcR γ chain in both NK cells and NK1+ T cells (40), providing an alternate mechanism for recruitment of signal transducing complexes. Further characterization of CD161-associated signal-transducing molecules should provide a molecular mechanism for the involvement of CD161 in positive regulation of human Vα24invt T cell responses to CD1d.

The blocking of Vα24invt T cell responses to CD1d+ target cells by CD161 antibodies indicates that these target cells and their physiological CD1d+ counterparts in vivo can express CD161 ligand(s). Although CD161 is a member of the C-type lectin superfamily, it is not clear that carbohydrate alone can be the ligand. As discussed above, one possible CD161 ligand is CD1d itself. In this model, CD161 contributes to CD1d recognition directly as a coreceptor (8), as CD4 and CD8 bind MHC class II and I molecules, respectively. An alternative suggested above is that human CD161 acts like CD28 and binds a true costimulatory ligand on physiological CD1d+ target cells. CD1d on CHO cells is insufficient to activate Vα24invt T cells without mild glutaraldehyde fixation (19), which has been found in other systems to artificially substitute for costimulatory signals (51, 53). Similarly, fixation markedly increases Vα24invt T cell response to CD1d+ Hela transfectants, but not to the B lymphoblastoid cells used in this study (M. Exley, unpublished observations). Therefore, such a CD161 costimulatory ligand may only be expressed by certain cell types.

In summary, we have found that human CD161 functions not as a direct stimulatory structure but as a costimulatory molecule for human Vα24invt T cell responses to their physiological ligand, CD1d. Activation of resting CD161+ Vα24invt T cells via the TCR in combination with signals mediated by CD161 ligation led to proliferation, and both Th1- and Th2-type cytokine secretion. However, the potent granule-mediated CD1d-restricted cytotoxic activity of preactivated Vα24invt T cells was CD161-independent. The costimulation of CD1d recognition through CD161 appears to reflect a different mechanism for activation of human Vα24invt T cells compared with rodent NK cells and NK1+ T cells, for both of which NKR-P1 is directly stimulatory and associated with p56Lck (3, 4, 37, 38, 48).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI-40135 (to S. Porcelli) and AI-33911 (to S. Balk), and by grants from the Arthritis Foundation (Investigator Award, to S. Porcelli) and the American Cancer Society (to S. Porcelli).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- DN

CD4/ CD8 double negative

- Vα24invt

Vα24JαQ TCR-expressing

Footnotes

For antibody and/or cell reagents, we wish to thank Drs. A. Bendelac, J. Hansen, R. Kurrle, L. Lanier, A. Lanzavecchia, M. Lopez-Botet, D. Olive, A. Poggi, E. Reinherz, M. Robertson, and J. Ritz. We would also like to thank Drs. S.B. Wilson, S. Kent, R. Blumberg, and our colleagues in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology, and Allergy, Brigham and Women's Hospital, especially J. Gumperz and D.B. Moody, for unpublished results, advice, or comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Giorda R, Weisberg E, Ip T, Trucco M. Genomic structure and strain-specific expression of the natural killer cell receptor NKR-P1. J Immunol. 1992;149:1957–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan J, Turck E, Niemi E, Yokayama W, Seaman W. Molecular cloning of the NK1.1 antigen, a member of the NKR-P1 family of natural killer cell activation markers. J Immunol. 1992;149:1631–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan J, Niemi E, Nakamura M, Seaman W. NKR-P1A is a target-specific receptor that activates NK cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1911–1915. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raulet D, Held W. Natural killer cell receptors: the offs and ons of NK cell recognition. Cell. 1995;82:697–700. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendelac A, Killeen N, Littman D, Schwartz R. A subset of CD4+thymocytes selected by MHC class I molecules. Science. 1994;263:1774–1778. doi: 10.1126/science.7907820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohteki T, MacDonald H. Major histocompatibility complex class I related molecules control the development of CD4+8− and CD4−8− subsets of natural killer 1.1+ T cell receptor-α/β+cells in the liver of mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:699–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor α chain is used by a unique subset of MHC class I–specific CD4+ and CD4−CD8− T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1097–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald H. NK1.1+ T cell receptor-α/β+cells: new clues to their origin, specificity, and function. J Exp Med. 1995;182:633–638. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendelac A, Rivera M, Park S, Roark J. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuda K, Makino Y, Cui J, Ito T, Tokuhisa T, Takahama Y, Koseki H, Tsuchida K, Koike T, Moriya H, et al. Phenotype and invariant αβ TCR expression of peripheral Vα14+NK T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2076–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby M, Yewdell J, Bennink J, Brutkiewicz R. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–865. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bix M, Locksley R. Natural T cells. Cells that co-express NKRP-1 and TCR. J Immunol. 1995;155:1020–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H, Paul W. Cultured NK1+ CD4+ T cells produce large amounts of IL-4 and IFN-γ upon activation by anti-CD3 or CD1. J Immunol. 1997;159:2240–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porcelli S, Yockey C, Brenner M, Balk S. Analysis of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) expression by human peripheral blood CD4−8−α/β T cells demonstrates preferential use of several Vβ genes and an invariant TCR α chain. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellabona P, Casorati G, Freidli B, Angman L, Sallusto F, Tunnacliffe A, Roosneek E, Lanzavecchia A. In vivo persistence of expanded clones specific for bacterial antigens within the human T cell receptor αβ+ CD4−CD8−subset. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1763–1771. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellabona P, Padovan E, Casorati G, Brockhaus M, Lanzavecchia A. An invariant Vα24JαQ Vβ11 T cell receptor is expressed in all individuals by clonally expanded CD4−CD8−T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1171–1180. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porcelli S, Gerdes D, Fertig A, Balk S. Human T cells expressing an invariant Vα24JαQ TCRα are CD4-negative and heterogeneous with respect to TCRβ expression. Hum Immunol. 1996;48:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(96)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Exley M, Garcia J, Balk S, Porcelli S. Requirements for CD1d recognition by human invariant Vα24JαQ+ NKR-P1A+T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:109–120. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davodeau F, Peyrat M, Necker A, Dominici R, Blanchard F, Leget C, Gaschet J, Costa P, Jacques Y, Godard A, et al. Close phenotypic and functional similarities between human and murine αβ T cells expressing invariant TCR α-chains. J Immunol. 1997;158:5603–5611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prussin C, Foster B. TCR Vα24 and Vβ11 coexpression defines a human NK1 T cell analog containing a unique Th0 subpopulation. J Immunol. 1997;159:5862–5870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshimoto T, Bendelac A, Watson C, Hu-Li J, Paul W. Role of NK1.1+T cells in a Th2 response and in immunoglobulin E production. Science. 1995;270:1845–1847. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bendelac A. Mouse NK1.1+T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown D, Fowell D, Corry D, Wynn T, Moskowitz N, Cheever A, Locksley R, Reiner S. β2-microglobulin–dependent NK1.1+T cells are not essential for T helper cell 2 immune responses. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1295–1298. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Rogers K, Lewis D. β2-microglobulin–dependent T cells are dispensable for allergen-induced T helper 2 responses. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1507–1511. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smiley S, Kaplan M, Grusby M. Immunoglobulin E production in the absence of IL-4-secreting CD1- dependent cells. Science. 1997;275:977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Chiu N, Mandal M, Wang N, Wang C. Impaired NK1+ T cell development and early IL-4 production in CD1-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendiratta S, Martin W, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda K, Lennert D. The development of autoimmunity in C57BL/6 lpr mice correlates with the disappearance of NK1+cells: evidence for their suppressive action on bone marrow stem cell proliferation, B cell immunoglobulin secretion, and autoimmune symptoms. J Exp Med. 1993;177:155–164. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi M, Ogasawara K, Takeda K, Hashimoto W, Sakihara H, Kumagai K, Anzai R, Satoh M, Seki S. LPS induces NK1.1+αβ T cells with potent cytotoxicity in the liver of mice via production of IL-12 from Kupffer cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2436–2444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, Sato H, Kondo E, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Koseki H, Kanno M, Taniguchi M. Requirement for Vα14 NK T cells in IL-12 mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278:1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumida T, Sakamoto A, Murata H, Makino Y, Takahashi H, Yoshida S, Nishioka K, Iwamoto I, Taniguchi M. Selective reduction of T cells bearing invariant Vα24JαQ antigen receptor in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1163–1168. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mieza M, Itoh T, Cui J, Makino Y, Kawano T, Tsuchida K, Koike T, Shirai T, Yagita H, Matsuzawa A, et al. Selective reduction of Vα14+NK T cells associated with disease development in autoimmune-prone mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:4035–4040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gombert J, Herbelin A, Tancrede-Bohin E, Dy M, Carnaud C, Bach J. Early quantitative and functional deficiency of NK1+-like thymocytes in the NOD mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2989–2998. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baxter A, Kinder S, Hammond K, Scollay R, Godfrey D. Association between αβ TCR+ CD4− CD8−T cell deficiency and IDDM in NOD/Lt mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:572–578. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson SB, Kent S, Patton K, Orban T, Jackson R, Exley M, Porcelli S, Schatz D, Atkinson M, Balk S, et al. Extreme Th1 bias of regulatory Vα24JαQ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 1998;391:177–179. doi: 10.1038/34419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanier L, Chang C, Phillips J. Human NKR-P1A. A disulfide-linked homodimer of the C-type lectin superfamily expressed by a subset of NK and T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:2417–2428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanier L. Natural killer cells: from no receptors to too many. Immunity. 1997;6:371–378. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long E, Seaman W. Natural killer cell receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:344–350. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arase H, Arase N, Saito T. Interferon γ production by natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+T cells upon CD161 cross-linking. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2391–2396. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arase N, Arase H, Park S, Ohno H, Ra C, Saito T. Association with FcRγ is essential for activation signal through NKR-P1 (CD161) in natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1957–1963. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zemmour J, Little A, Schendel D, Parham P. The HLA-A, -B negative mutant cell line C1R expresses a novel HLA-B35 allele which also has a point mutation in the translation initiation codon. J Immunol. 1992;148:1941–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porcelli S, Brenner M, Greenstein J, Balk S, Terhorst C, Bleicher P. Recognition of cluster of differentiation 1 antigens by human CD4−CD8−cytolytic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;341:447–450. doi: 10.1038/341447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porcelli S, Morita C, Brenner M. CD1b restricts the response of human CD4−CD8−T lymphocytes to a microbial antigen. Nature. 1992;360:593–597. doi: 10.1038/360593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Exley M, Varticovski L, Peter M, Sancho J, Terhorst C. Association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with a specific sequence of the T cell receptor ζ chain is dependent on T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15140–15146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poggi A, Pella N, Morelli L, Spada F, Revello V, Sivori S, Augugliaro R, Moretta L, Moretta A. p40, a novel surface molecule involved in the regulation of non-major histocompatibility complex-restricted cytolytic activity in humans. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:369–376. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valiente N, Trinchieri G. Identification of a novel signal transduction surface molecule on human cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1397–1406. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poggi A, Rubartelli A, Moretta L, Zocchi MR. Expression and function of NKRP1A molecule on human monocytes and dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2965–2970. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell K, Giorda R. The cytoplasmic tail of rat NKR-P1 receptor interacts with the N-terminal domain of p56Lckvia cysteine residues. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:72–77. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turner J, Brodsky M, Irving B, Levin S, Perlmutter R, Littman D. Interaction of the unique N-terminal region of tyrosine kinase p56lckwith cytoplasmic domains of CD4 and CD8 is mediated by cysteine motifs. Cell. 1990;60:755–765. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyaard L, Adema GJ, Chang C, Woollatt E, Sutherland GR, Lanier LL, Phillips JH. LAIR-1, a novel inhibitory receptor expressed on human mononuclear leukocytes. Immunity. 1997;7:283–290. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Behar S, Porcelli S, Beckman E, Brenner M. A pathway of costimulation that prevents anergy in CD28−T cells: B7-independent costimulation of CD1-restricted T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2007–2018. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eshima K, Suzuki T, Yamazaki H, Shinohara S. Co-receptor-independent signal transduction in a mismatched CD8+ major histocompatibility complex class II-specific allogeneic cytotoxic T lymphocyte. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:55–61. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhodes J, Chen H, Hall S, Beesley J, Jenkins D, Collins P, Zheng B. Therapeutic potentiation of the immune system by co-stimulatory Schiff-base-forming drugs. Nature. 1995;377:71–75. doi: 10.1038/377071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]