Abstract

Transphosphorylation by Src family kinases is required for the activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk). Differences in the phenotypes of Btk−/− and lyn−/− mice suggest that these kinases may also have independent or opposing functions. B cell development and function were examined in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice to better understand the functional interaction of Btk and Lyn in vivo. The antigen-independent phase of B lymphopoiesis was normal in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice. However, Btk−/−lyn−/− animals had a more severe immunodeficiency than Btk−/− mice. B cell numbers and response to T cell–dependent antigens were reduced. Btk and Lyn therefore play independent or partially redundant roles in the maintenance and function of peripheral B cells. Autoimmunity, hypersensitivity to B cell receptor (BCR) cross-linking, and splenomegaly caused by myeloerythroid hyperplasia were alleviated by Btk deficiency in lyn−/− mice. A transgene expressing Btk at ∼25% of endogenous levels (Btklo) was crossed onto Btk−/− and Btk−/−lyn−/− backgrounds to demonstrate that Btk is limiting for BCR signaling in the presence but not in the absence of Lyn. These observations indicate that the net outcome of Lyn function in vivo is to inhibit Btk-dependent pathways in B and myeloid cells, and that Btklo mice are a useful sensitized system to identify regulatory components of Btk signaling pathways.

Keywords: B cell receptor, B cell development, Src family kinases, transgenic mice, immunodeficiency

The development of a diverse repertoire of B cells and the maintenance of self-tolerance depend on signals transduced by the B cell antigen receptor (BCR).1 The outcome of BCR engagement varies from proliferation and differentiation to deletion depending on the developmental stage of the B cell, concurrent signals, and the degree of BCR cross-linking (for review see reference 1). A complex signaling network translates BCR-mediated signals into the appropriate response given the context in which they are received. One of the initial biochemical consequences of BCR engagement is the sequential activation of a cascade of tyrosine kinases belonging to the Src, Btk/Tec, and Syk/ Zap70 families. The phosphorylation of multiple substrates by these kinases leads to signaling events which include stimulation of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, phosphoinositide hydrolysis, Ca2+ flux, and the activation of PI3-kinase α (for review see reference 2). B cell development is generally blocked at the proB to preB transition in the absence of preB receptor or BCR subunits (3–6). syk−/− mice have a similar phenotype (7, 8), but B lymphopoiesis is less severely affected in mice lacking other molecules downstream of the BCR such as Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk; references 9–11), Lyn (12–14), Fyn (15, 16), PKCβ (17), and Vav (18, 19). This suggests that, although Syk plays a unique role early in B cell development, there may be a significant degree of redundancy among some components of BCR signaling pathways.

Src family kinases, including Lyn, Blk, Fyn, Lck, and Fgr, are activated rapidly upon BCR cross-linking (2). Among Src family kinases, only mutations in Lyn have been described as affecting BCR signaling (12–16, 20). Intriguingly, Lyn appears to be involved in both the initiation of BCR signals and their subsequent downregulation (14, 20). Anti-IgM-mediated cross-linking of the BCR results in slightly delayed and reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of Igα, Syk, shc, and several other substrates in B cells from lyn−/− mice (13, 14). The residual phosphorylation is probably catalyzed by other Src family kinases present in these cells. Despite delayed signal initiation, lyn−/− murine B cells are hypersensitive to anti-IgM stimulation (14, 20). This results from impaired downregulation of BCR signaling via both FcγRIIb-dependent and -independent mechanisms (14).

Mutations in Lyn also affect B cell development. The frequency of peripheral B cells is reduced approximately twofold in lyn−/− mice (12–14, 20). The remaining cells have an immature cell surface phenotype and a shorter life span than do wild-type B cells (14). Serum IgM and IgA levels are increased (12, 13). Aged lyn−/− animals develop autoantibodies and exhibit splenomegaly due to extramedullary hematopoiesis and the expansion of IgM-secreting B lymphoblasts (12–14). The phenotype of lyn−/− mice is strikingly similar to that of motheaten (me) mice (21), which are deficient in the negative regulator of BCR signaling SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP1). This suggests that other Src kinases cannot compensate for Lyn in the termination of BCR signals.

Several lines of evidence indicate that Btk is downstream of Src family kinases in a BCR signaling pathway. Coexpression of Btk and Lyn in fibroblasts leads to the transphosphorylation of Btk on Y551 and activation of Btk kinase activity (22, 23). Btk is also phosphorylated on Y551 in response to BCR cross-linking (22, 24). The ability of an activated form of Btk to transform fibroblasts is dependent on both the activity of Src family kinases and the presence of Y551 (25, 26). Mutation of Y551 also prevents Btk from mediating BCR-induced Ca2+ flux in B cells (27, 28). These combined observations indicate that transphosphorylation by Src kinases is critical for Btk function.

Mutations in Btk result in the B cell immunodeficiencies X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) in humans (29, 30) and X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) in mice (31, 32). XLA patients have a block at the preB stage of development, resulting in a severe deficit of circulating B cells and serum Ig (for review see reference 33). Both xid and Btk−/− (9–11) mice have a more subtle phenotype (for review see reference 33). They have a 30–50% decrease in the number of peripheral B cells, with the most profound reduction in the mature IgMloIgDhi subset. xid mice have reduced levels of serum IgM and IgG3 and do not respond to type II T cell–independent antigens. They also lack B1 cells. Responses to the engagement of several cell surface receptors including BCR, IL-5R, IL-10R, and CD38 are impaired in the absence of Btk. B cells expressing reduced levels of Btk are hyposensitive to anti-IgM (34), suggesting that Btk is limiting for the transmission of signals from the BCR.

Despite the biochemical evidence that Lyn and Btk operate sequentially in common signaling pathways, the different phenotypes of Btk−/− and lyn−/− mice (low versus high serum IgM, hypo- versus hypersensitivity to BCR cross-linking) suggest that these kinases may also have opposing roles in BCR signaling. To clarify this issue, we examined B cell development in mice lacking both Btk and Lyn. If Btk and Lyn oppose each other, Btk deficiency might be expected to rescue the lyn−/− phenotype, analogous to the rescue of the me B cell phenotype by CD45 deficiency (35). If Lyn is the sole upstream activator of Btk, then effects on B cell development should be no more severe in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice than in lyn−/− mice alone. Increased severity of phenotype would indicate that Btk and Lyn are partially redundant components of one signaling pathway or participants in independent pathways. A combination of these possibilities was observed, indicating that Lyn both opposes Btk-mediated signals and plays a positive signaling role independent of or partially redundant with Btk.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Btk−/− (10) and lyn−/− mice (14), each on a mixed C57B/6 × 129/Sv genetic background, were crossed to generate Btk +/− lyn +/− F1 progeny. These F1 animals were mated resulting in wild-type (wt), Btk-deficient, Lyn-deficient, and Btk/Lyn-deficient progeny. Genotypes were determined by Southern blot (10) or PCR (14) analysis of tail biopsy DNA as described. For the analysis of limiting Btk dosage in Fig. 5, crosses were performed as above starting with Btk−/− mice carrying an Ig heavy chain enhancer/ promoter–driven Btk transgene expressing ∼25% of endogenous Btk levels in B cells (34). The resulting progeny were on a mixed C57B/6 × 129/Sv × Balb/c background. The presence of the Btk transgene was determined by Southern blot as previously described (34).

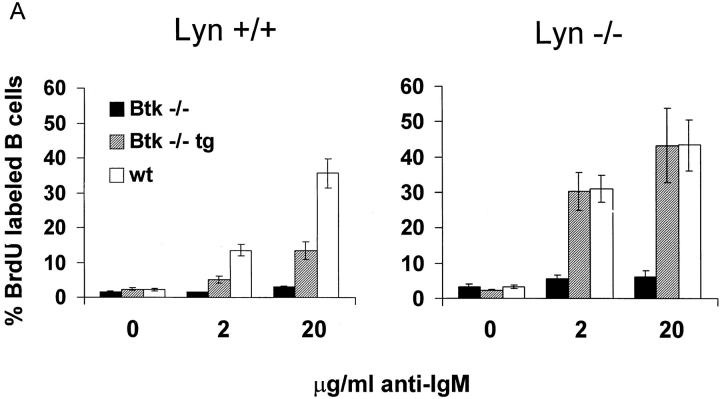

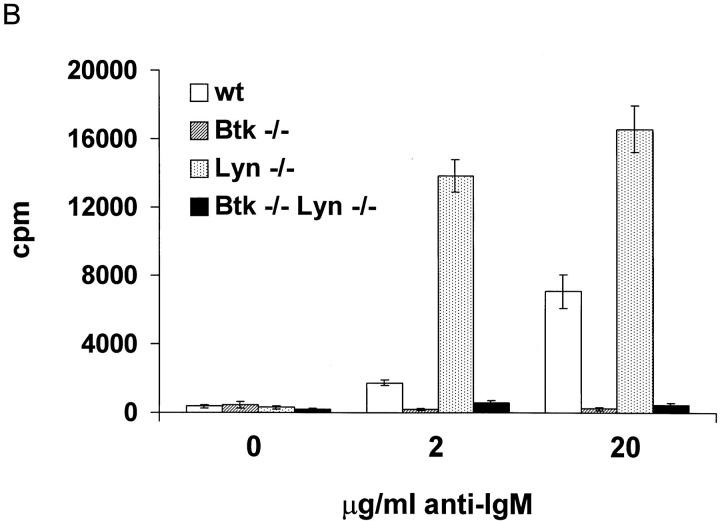

Figure 5.

Enhancement of Btk-dependent signaling in the absence of Lyn. (A) Single cell suspensions of spleens from eight to ten week old Btk −/−, Btk lo, and wt mice on a lyn +/+ (left) or lyn −/− (right) background were depleted of red blood cells and incubated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab)′2 fragments. Cells were labeled with BrdU for an additional 24 h and stained with anti-BrdU FITC and anti-B220 PE. The percentage of B220+ cells labeled with BrdU is indicated. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for transgenic mice, n = 5 for all other groups). (B) B220+ cells were purified from spleens from 8-wk-old wt, Btk −/−, lyn −/−, and Btk −/− lyn −/− mice using the Minimacs magnetic bead system. Cells were incubated in triplicate with the indicated concentrations of goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab)′2 fragments for 48 h and labeled with [3H]thymidine for a further 12–16 h. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (two independent mice per group, triplicate samples per mouse) and are from one of four experiments giving similar results.

Flow Cytometry

Phenotypic Analysis.

Single cell suspensions from spleen, bone marrow, or peritoneal wash were depleted of red blood cells and stained with combinations of the following antibodies (from PharMingen, San Diego, CA, unless otherwise noted): PE-conjugated (PE) anti-B220 (RA2-6B2); FITC-conjugated (FITC) anti-IgM (R6-60.2); anti-IgDa (AMS 9.1) PE; anti-IgDb (217-170) PE; anti-CD5 (53-7.3) FITC; anti–Thy-1.2 (53-2.1) FITC; anti-CD4 (H129.19) PE; anti-CD8 (53-6.7) FITC; anti-Ter119 (TER-119) PE; anti-Gr1 (RB6-8C5) PE; and anti-Mac1 (M1/ 70HL) FITC (Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, IN). Data was acquired on a FACScan® (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using LYSIS II software. Live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter. A gate characteristic of lymphoid cells based on forward and side scatter was used for acquisition of peritoneal cells.

Analysis of In Vivo Bromodeoxyuridine Incorporation.

Mice were fed 0.25 mg/ml bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and 2.5% glucose in their drinking water continuously for up to 15 d. Single cell suspensions of spleens and peripheral blood were depleted of red blood cells, stained with anti-BrdU FITC (Becton Dickinson) and anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) PE (PharMingen) as previously described (36), and analyzed as above.

Proliferation Assays

BrdU Labeling.

Total splenocytes were depleted of red blood cells and plated in RPMI with 10% heat-inactivated FCS at 106/ml. Where indicated, goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab′)2 fragments (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs., West Grove, PA) were added at either 2 or 20 μg/ml. At 24 h, BrdU (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 10 μM. Cells were harvested at 48 h and FACS® analysis was performed as above.

[3H]Thymidine Labeling.

B220+ spleen cells were isolated using the Minimacs magnetic bead system (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Single cell suspensions were depleted of red blood cells before incubation with magnetic beads. B cell–enriched populations were >90% B220+ by FACS® analysis. B220+ splenic B cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 5 × 105/ml in RPMI with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Where indicated, cells were incubated for 60 h with 2 or 20 μg/ml goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab′)2 fragments (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.). 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) was added per well for the final 12-18 h. Cells were harvested and counted on a scintillation counter.

ELISA

Serum Ig.

Plates were coated with 2 μg/ml goat anti–mouse Ig (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Huntington, AL) and blocked with 1% BSA in borate-buffered saline (BBS). Serum or Ig standards (mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA; Sigma Chemical Co.) were diluted serially into BBS and added to wells in duplicate. Plates were washed, incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti–mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, or IgA-alkaline phosphatase [ALPH], Southern Biotechnology Associates) diluted 1:500 in BBS/0.05% Tween 20/1% BSA and developed with an ALPH substrate kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). OD405 was read on a Vmax kinetic microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA).

Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin.

Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg of keyhole limpet hemocyanine (KLH) (Sigma Chemical Co.) in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), boosted on day 21 with 50 μg of KLH in PBS, and bled on day 28. ELISAs were performed as above with the following modifications: plates were coated with 8 μg/ ml of KLH, and secondary antibodies were goat anti–mouse IgM-ALPH and goat anti–mouse IgG1-ALPH.

2,4,6-Trinitrophenyl–Ficoll.

Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 10 μg of 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl (TNP)-Ficoll (a gift of Dr. John Inman, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and bled 6 d later. ELISA was performed as above with the following modifications: plates were coated with 25 μg/ml of TNP-BSA in PBS, and serum and secondary antibody (goat anti–mouse IgM-ALPH) were diluted into PBS/0.1% BSA, and 0.05% Tween 20.

dsDNA.

Unimmunized mice were bled at 16–20 wk of age. Serum antibodies to dsDNA were measured in triplicate by ELISA as previously described (14).

Immunofluorescence

Unimmunized mice were bled at 16–20 wk of age. Serum antibodies to nuclear antigens were measured by immunofluorescence as previously described (14).

Results

Generation of Btk−/−lyn−/− Mice.

We bred Btk +/− lyn +/− mice to generate wild-type, Btk−/−, lyn−/−, and Btk−/−lyn−/− progeny in order to examine the interaction of these kinases in B cell development and function. All genotypes occurred in the predicted Mendelian frequencies, indicating that embryonic development occurs normally in the absence of both Btk and Lyn. Btk−/−lyn−/− mice were healthy and fertile. lyn +/+ and lyn +/− animals were indistinguishable in the assays described below and were therefore used interchangeably. All mice were on a mixed C57B/6 × 129/Sv background. Although the phenotype of Btk deficiency has been described to differ according to genetic background (10, 37, 38), little variation was observed within each group of mice analyzed here.

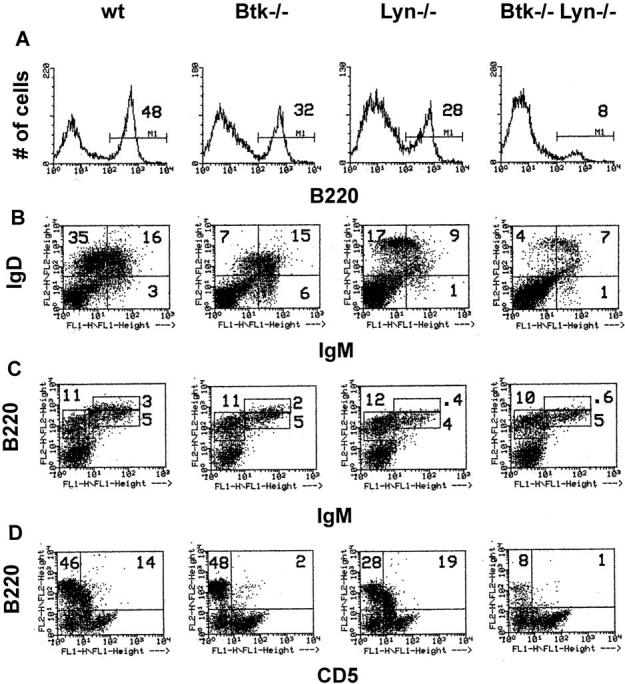

Reduced Numbers of Peripheral B Cells In Btk−/−lyn−/− Mice.

To understand whether Lyn and Btk are components of a common signaling pathway or function independently in B cells, we examined B cell development in the absence of Btk alone, Lyn alone, or both Btk and Lyn. Both the frequency and number of splenic B cells in 8-wk-old Btk−/−lyn−/− mice was reduced two- to fourfold relative to either Btk−/− or lyn−/− animals and four- to sixfold compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1 A and Table 1). The remaining B cells had an immature IgMhiIgDlo phenotype similar to Btk−/− B cells (Fig. 1 B). This decrease was specific to the B lineage. No significant difference in myeloid cell numbers was observed in the spleens of young mice, and T cell numbers were reduced less than twofold compared with wild-type controls (Table 1). The frequency of conventional (B220+CD5−) B cells in the peritoneum was also diminished in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice compared with single knockouts alone (Fig. 1 D, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Reduced number of peripheral B cells in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice. (A and B) Single cell suspensions of spleen cells from 8-wk-old mice were depleted of red blood cells and stained with anti-B220 PE (A), anti-IgM FITC (B, x-axis), and anti-IgDa+b PE (B, y-axis). Live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter. The variation in intensity of IgD staining is due to the mixed genetic background of the animals. Both the a and b haplotypes of IgD are represented in the population of F2 mice analyzed in this study, and the antibodies against these haplotypes fluoresce with different intensities. (C) Single cell suspensions of bone marrow cells from 8-wk-old mice were depleted of red blood cells and stained with anti-IgM FITC (x-axis) and anti-B220 PE (y-axis). Cells in a lymphoid gate are represented. The percentage of total cells falling in each region is indicated. (D) Peritoneal cells from 8-wk-old mice were depleted of red blood cells and stained with anti-CD5 FITC (x-axis) and anti-B220 PE (y-axis). Cells in a lymphoid gate are represented. The percentage of lymphoid cells falling in each region is indicated.

Table 1.

Reduced Numbers of Peripheral B Cells in Btk− /−lyn− /− Mice

| wt | Btk −/− | Lyn −/− | Btk −/− Lyn −/− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | ||||||||

| Total cells (× 107) | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 0.98 | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | ||||

| Percentage of B cells | 48 ± 5.0 | 35 ± 8.1 | 27 ± 7.5 | 13 ± 4.6 | ||||

| No. of B cells (× 107) | 2.8 ± 0.74 | 1.9 ± 0.68 | 1.2 ± 0.37 | 0.46 ± 0.32 | ||||

| Percentage of T cells | 39 ± 5.2 | 38 ± 2.7 | 44 ± 9.4 | 52 ± 15 | ||||

| No. T cells (× 107) | 2.2 ± 0.45 | 2.0 ± 0.36 | 2.0 ± 0.55 | 1.6 ± 0.44 | ||||

| Percentage of myeloid cells | 12 ± 2.6 | 18 ± 4.4 | 22 ± 2.7 | 22 ± 4.9 | ||||

| No. of myeloid cells (× 107) | 0.65 ± 0.25 | 0.93 ± 0.19 | 1.1 ± 0.60 | 0.80 ± 0.48 | ||||

| Bone marrow | ||||||||

| Total cells (× 107) | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 3.6 ± 0.97 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | ||||

| Percentage of B220+IgM− | 11 ± 3.0 | 9.9 ± 3.5 | 12 ± 4.6 | 10 ± 3.7 | ||||

| Percentage of B220intIgM+ | 5.6 ± 0.79 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | ||||

| Percentage of B220hiIgM+ | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 1.2 ± 0.63 | 0.84 ± 0.62 | ||||

| Peritoneum | ||||||||

| Percentage of B220+CD5− | 41 ± 6.8 | 40 ± 7.9 | 20 ± 5.0 | 13 ± 4.7 | ||||

| Percentage of B220+CD5+ | 22 ± 8.4 | 7.3 ± 3.4 | 19 ± 8.5 | 5.8 ± 2.5 |

Single cell suspensions of spleen, bone marrow, or peritoneal cells from 8-wk-old mice were depleted of red blood cells and stained with the following combinations of antibodies: bone marrow, anti-IgM FITC versus anti-B220 PE; spleen, anti-IgM FITC versus anti-B220 PE, anti-Thy-1.2 FITC versus anti-B220 PE, anti-CD8 FITC versus anti-CD4 PE, and anti-Mac1 FITC versus anti-Gr-1 PE; peritoneum, anti-CD5 FITC versus anti-B220 PE. Live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter. The frequency and absolute number of B (B220+), T (Thy-1.2+ or CD4+ and CD8+), and myeloid (Mac1+ and/or Gr1+) cells are indicated for spleen. The frequency of proB and preB cells (B220+IgM−), immature B cells (B220intIgM+), and recirculating B cells (B220hiIgM+) in bone marrow is shown. The frequency of CD5− and CD5+ B cells in the peritoneum was determined for cells in a lymphoid gate. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6).

Either a block in the bone marrow phase of B cell development or reduced half life of peripheral B cells could be responsible for the small number of splenic B cells in Btk−/− lyn−/− mice. Both the B220+IgM− population, consisting of proB and preB cells, and B220intIgM+ immature B cells were present in similar frequencies in bone marrow from wild-type, Btk−/−, lyn−/−, and Btk−/−lyn−/− mice (Fig. 1 C and Table 1). Therefore, the antigen-independent phase of B cell development proceeds normally in the absence of both Btk and Lyn. B220hiIgM+ recirculating B cells were three- to fourfold less frequent in both lyn−/− (as previously reported in references 12 and 13) and Btk−/−lyn−/− mice than in wild-type controls (Fig. 1 C and Table 1). This is consistent with the significant reduction in mature B cell numbers in the periphery.

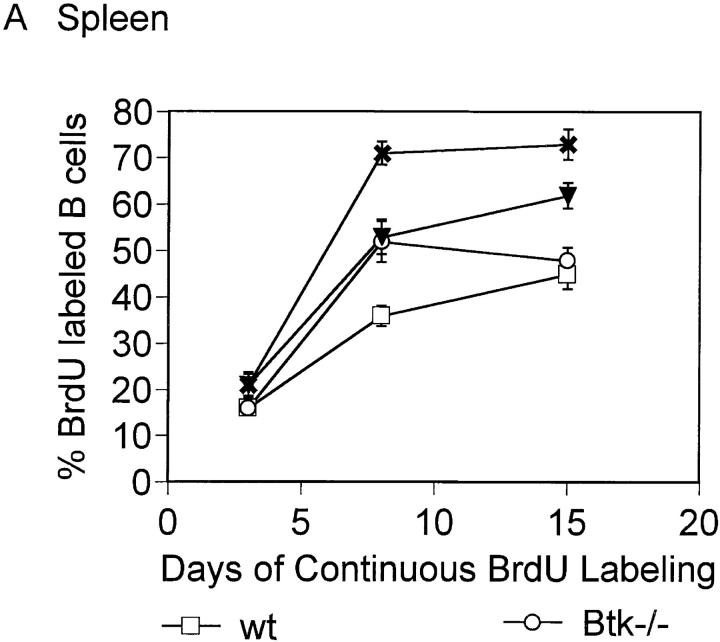

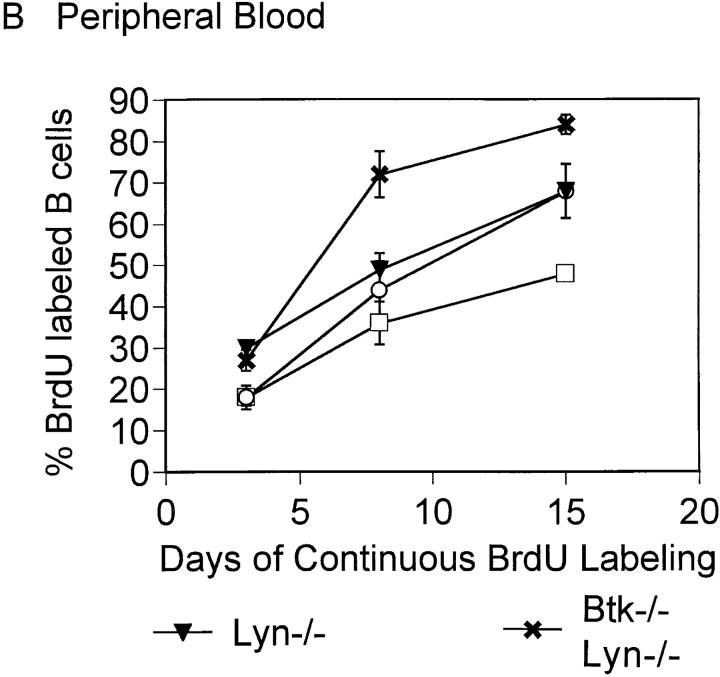

The turnover rate of the peripheral B cell population was assessed with in vivo BrdU labeling since an early developmental block did not account for the reduced number of splenic B cells in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice. Short-lived B cells in the periphery are replaced by newly generated cells that have incorporated BrdU, whereas long-lived resting cells remain unlabeled. Both splenic and peripheral blood B cells from Btk−/−lyn−/− mice turned over faster than wild-type, Btk−/−, or lyn−/− B cells (Fig. 2). Greater than 70% of Btk−/− lyn−/− B220+ cells were labeled with BrdU after 8 d, compared with ∼35% in wild-type mice and 50% in mice lacking either Btk or Lyn alone (Fig. 2). These observations indicate that the reduced number of B cells in mice lacking both Btk and Lyn is due to poor survival in the periphery rather than decreased production of B cells in the bone marrow.

Figure 2.

Increased turnover of Btk −/− lyn −/− peripheral B cells. 8–10-wk-old wt, Btk −/−, lyn −/−, and Btk −/− lyn −/− mice were fed BrdU in their drinking water continuously. Single cell suspensions were isolated from the spleen (A) and peripheral blood (B) of mice at the times indicated, depleted of red blood cells, and stained with anti-BrdU FITC and anti-B220 PE. The percentage of B220+ cells labeled with BrdU is represented. Data were collected in two independent experiments and are presented as mean ± SEM of at least four mice per group.

Serum Ig Levels and Immune Responses Are Decreased in Btk−/−lyn−/− Mice.

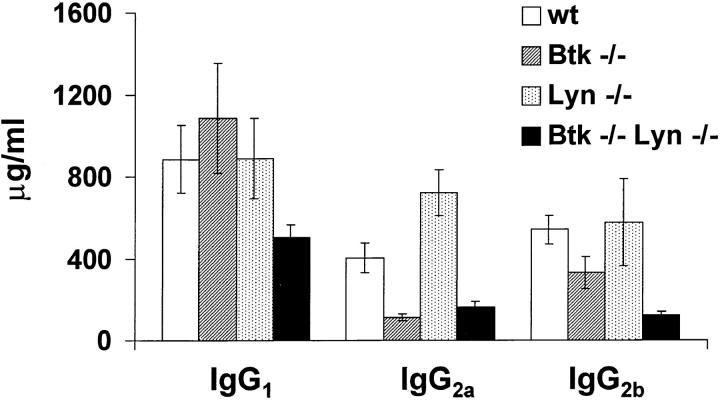

To determine whether the reduced number of peripheral B cells in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice was accompanied by alterations in serum Ig levels, the amount of each Ig isotype present in the serum of 6–8-wk-old wild-type, Btk−/−, lyn−/−, and Btk−/−lyn−/− mice was measured (Fig. 3). Btk−/− mice had a >10-fold reduction in IgM and IgG3 levels, and a 2–4-fold decrease in IgG2a and IgG2b. IgM and IgA levels were slightly elevated in lyn−/− mice compared with wild-type controls, although the 5–10-fold increase in these isotypes described in lyn−/− mice in two previous studies (12, 13) was not observed. This may be due to differences in the age of the animals at the time of analysis, since serum IgM levels in lyn−/− mice increase with time (12, 13). Btk−/−lyn−/− mice resembled Btk−/− mice with respect to IgM, IgG3, and IgG2a levels, and had increased IgA similar to lyn−/− animals. The amount of IgG2b and IgG1 was reduced in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice compared with all other genotypes, consistent with the low numbers of peripheral B cells in these animals.

Figure 3.

Serum Ig levels in Btk −/− lyn −/− mice. Serum levels of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, and IgA in 6–8-wk-old wt, Btk −/−, lyn −/−, and Btk −/− lyn −/− mice were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8).

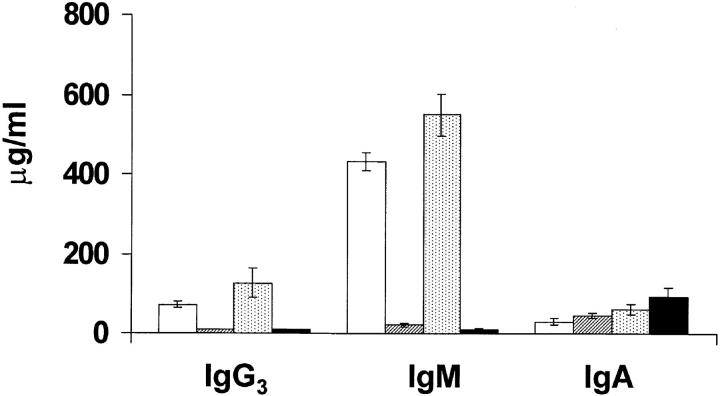

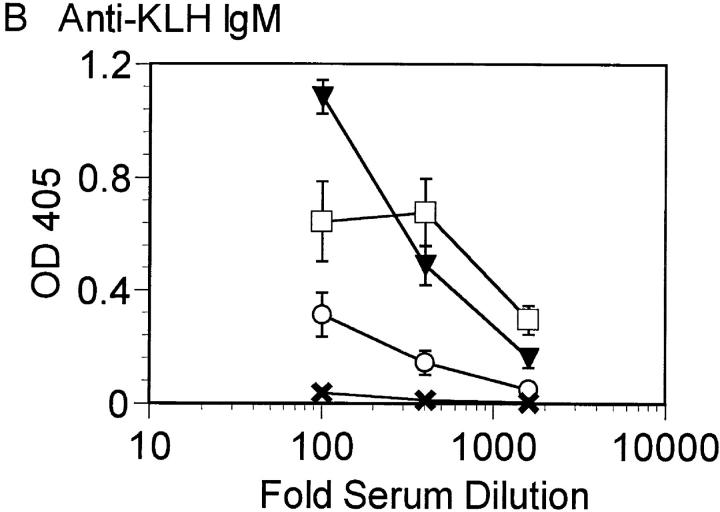

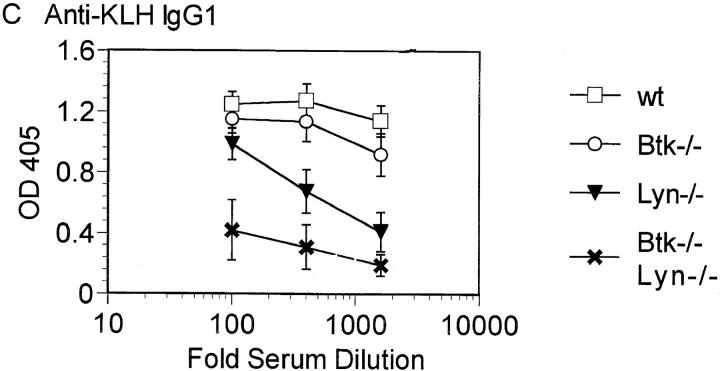

The dramatic effect of double Btk and Lyn deficiency on B cell numbers suggested that B cell function may also be more severely inhibited in the absence of both kinases. The ability of Btk−/−lyn−/− mice to mount an immune response to the T cell–independent antigen TNP-Ficoll and the T cell–dependent antigen KLH was assessed. Btk−/−lyn−/− mice failed to produce antibodies against TNP-Ficoll (Fig. 4 A), as expected, since this response requires Btk. Mice lacking either Btk or Lyn alone have relatively normal secondary responses to T cell–dependent antigens such as KLH (Fig. 4, B and C). Strikingly, anti-KLH IgM was not detectable in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice (Fig. 4 B). IgG1 titers against KLH were measurable but lower on average than in mice of all other genotypes (Fig. 4 C). Although the impaired IgG1 response could be attributed to low B cell numbers, the reduction in anti-KLH IgM was significant even when corrected for cell number. This indicates that Btk and Lyn are redundant for the production of IgM against T-dependent antigens.

Figure 4.

Impaired immune responses in Btk −/− lyn −/− mice. (A) 6–8-wk-old wt, Btk −/−, lyn −/−, and Btk −/− lyn −/− mice were immunized with 10 μg TNP-Ficoll and bled 6 d later. Anti-TNP IgM was measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). (B and C) 8–10-wk-old wt, Btk −/−, lyn −/−, and Btk −/− lyn −/− mice were immunized with 100 μg KLH at day 0 and boosted with 50 mg KLH at day 21. Mice were bled at day 28 and anti-KLH IgM (B) and IgG1 (C) were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The number of animals per group is as follows: wild type, 6; Btk −/−, 7; lyn −/−, 6; Btk −/− lyn −/−, 5.

Lyn Has a Net Inhibitory Effect on Btk-mediated BCR Signals.

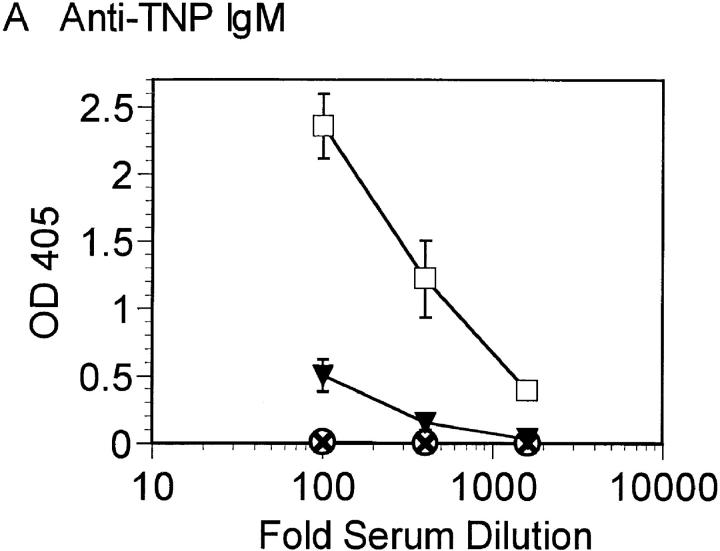

Several aspects of B cell function differ significantly between lyn−/− and Btk−/− mice despite the similar reduction in conventional B cell numbers. Most strikingly, lyn−/− B cells are hyperresponsive to BCR cross-linking (14, 20), whereas Btk−/− cells fail to proliferate in response to anti-IgM (10). A transgenic model, in which varying doses of a Btk transgene driven by the Ig heavy chain enhancer and promoter are expressed on an xid or Btk−/− background, has been used to demonstrate that Btk dosage is limiting for response to BCR cross-linking (34). B cells expressing low levels of transgenic Btk and no endogenous Btk (Btk lo) develop normally but have reduced sensitivity to BCR cross-linking (34). This system was used to determine whether the net effect of Lyn is to activate or inhibit Btk function. Low doses of Btk should be less effective in mediating mitogenic response to BCR engagement on a lyn−/− background if Lyn is an essential upstream activator of Btk during signal initiation. Alternatively, the ability of limiting amounts of Btk to transmit BCR signals should be enhanced in the absence of Lyn if the negative role of Lyn predominates.

A Btk transgene expressing ∼25% of endogenous Btk levels in splenic B cells (34) was crossed onto both Btk−/− (Btk lo) and Btk−/−lyn−/− (Btk lo lyn−/−) backgrounds. The frequency and absolute number of B220+ and IgMloIgDhi cells were increased two- to threefold in Btk lo spleens relative to Btk−/− spleens in both the presence and absence of Lyn (reference 34 and data not shown), indicating that the transgene restored Btk-dependent signals for maintenance of B cell numbers. Btk lo B cells were less sensitive to BCR engagement than were wild-type B cells (reference 34 and Fig. 5 A). In contrast, the BCR-induced proliferative response of Btk lo lyn−/− B cells was indistinguishable from that of lyn−/− B cells even at low doses of anti-IgM (Fig. 5 A). Btk−/−lyn−/− B cells failed to proliferate upon anti-IgM stimulation (Fig. 5 A). This was not due to altered T or myeloid cell function, as the same result was obtained with purified B cells (Fig. 5 B) and total splenocytes (Fig. 5 A). Lyn deficiency therefore enhances Btk-dependent signaling by the BCR but cannot bypass a requirement for Btk. These observations suggest that Lyn has a net inhibitory effect on Btk-dependent BCR signaling pathways.

Autoimmunity in lyn−/− Mice Is Dependent on Btk.

The development of autoimmunity in aged lyn−/− mice is another feature that distinguishes them from Btk−/− and xid mice (12–14). The xid mutation has been shown to prevent autoantibody production in both NZB×NZW mice (39, 40) and me mice (41). Although six out of six lyn−/− mice older than 16 wk developed IgM and IgG antibodies against both dsDNA and nuclear antigens, no Btk−/−lyn−/− animals of similar age displayed signs of autoimmunity (Table 2). Peritoneal B1 cells are believed to be a major source of anti-self antibodies in autoimmune strains of mice (42, 43). Btk−/−lyn−/− mice, like Btk−/− mice, have a reduced frequency of B220+CD5+ cells in the peritoneum relative to wild-type or lyn−/− animals (Fig. 1 D, Table 1).

Table 2.

Autoimmunity in lyn− /− Mice Is Btk Dependent

| wt | Btk −/− | Lyn− /− | Btk −/− Lyn −/− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies to nuclear antigens* | 1/7 (weak) | 0/5 | 6/6 | 0/7 | ||||

| Antibodies to dsDNA‡ | ||||||||

| IgM | 0.062 | 0.031 | 0.459 | 0.016 | ||||

| ± 0.018 | ± 0.013 | ± 0.281 | ± 0.006 | |||||

| IgG | 0.017 | 0.004 | 0.417 | 0.005 | ||||

| ± 0.006 | ± 0.002 | ± 0.274 | ± 0.002 |

Mice were 16–20-wk-old at the time of analysis.

Number of mice positive for antibodies against nuclear antigens/total mice tested by immunofluorescence.

Antibodies against dsDNA were measured by ELISA assay. OD450 values are shown as mean ± SEM. Triplicate samples were measured for each mouse, with the number of individual mice per group as follows: wild-type, 7; Btk −/−, 5; lyn −/−, 6; Btk −/− lyn −/−, 7.

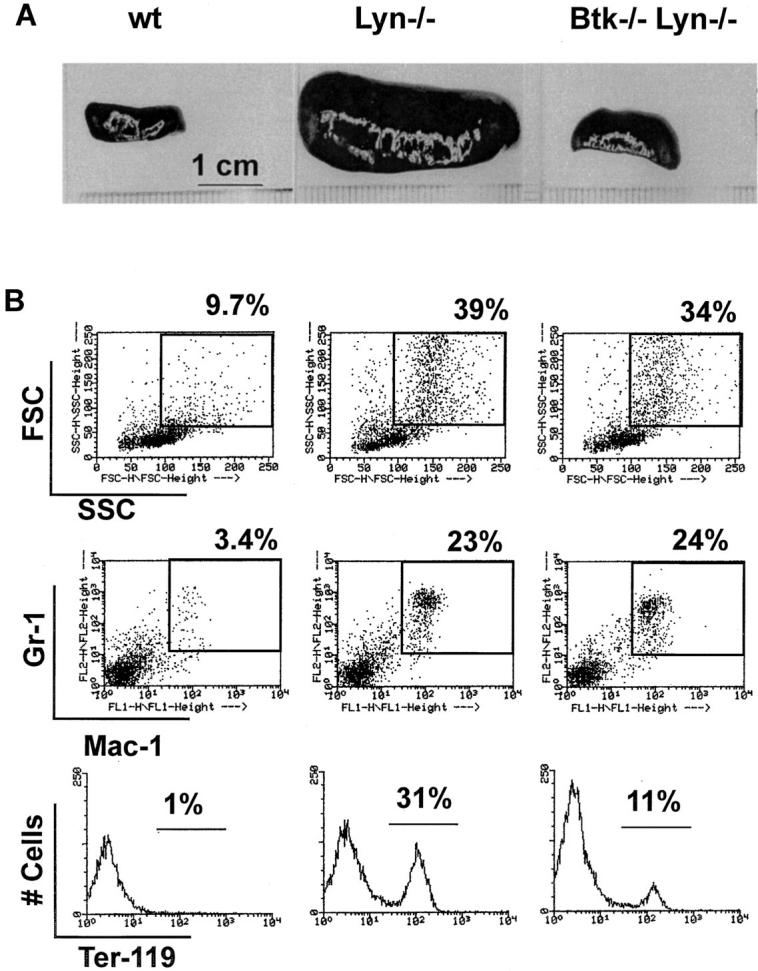

A Potential Role for Btk in Myeloid Expansion Is Revealed in the Absence of Lyn.

Splenomegaly resulting from extramedullary hematopoiesis occurs after 14 wk of age in the absence of Lyn (12–14). No myeloid phenotype has been described in xid or Btk−/− mice or in XLA patients, although a partial defect in FcεRI-mediated cytokine induction has been reported in xid and Btk−/− mast cells (44). Consistent with these observations, the increased frequency of myeloid and erythroid cells characteristic of lyn−/− spleens was also observed in old Btk−/−lyn−/− mice (Fig. 6 B). Surprisingly, splenomegaly did not occur in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice. Spleens of 10–11-mo-old Btk−/−lyn−/− mice were four- to fivefold smaller by both weight (0.208 ± 0.042 g vs. 1.1 ± 0.4 g, n = 2) and cell count (3.74 × 107 ± 2.5 × 107, n = 5, vs. 1.6 × 108 ± 0.72 × 108, n = 6, nucleated cells) than those of age-matched lyn−/− mice (Fig. 6 A). These results suggest that although extramedullary hematopoiesis does not require Btk, the subsequent expansion of myeloid and erythroid elements in lyn−/− mice is Btk dependent.

Figure 6.

Splenomegaly and extramedullary hematopoeisis in lyn −/− mice are uncoupled in the absence of Btk. (A) Spleens from 10–11-mo-old mice are shown. (B) Single cell suspensions from spleens from 10–11-mo-old mice were depleted of red blood cells and stained with anti-Mac1 FITC (middle; x-axis) versus anti–Gr-1 PE (middle; y-axis) and anti-Ter119 PE (bottom; x-axis). The percentage of total cells falling in the indicated regions is shown.

Discussion

Independent Roles for Btk and Lyn in the Maintenance of Peripheral B Cell Numbers.

A large body of evidence derived from biochemical and tissue culture–based experiments demonstrates that activation of Btk requires Src family kinases (22–28). However, the increased severity of the B cell phenotype in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice compared with lyn−/− mice alone indicates that Btk can still transmit signals in the absence of Lyn. In fact, the ability of limiting doses of Btk to signal is enhanced in lyn−/− B cells. This suggests either that Lyn is redundant with other Src family kinases for the activation of Btk in mature B cells or that Btk can be activated by Src family–independent mechanisms. Although activation of Btk is critically dependent on Src kinases in a fibroblast model (22, 23, 26), additional regulatory mechanisms cannot be ruled out in the B lineage.

Although Lyn may contribute to the activation of Btk in concert with other Src kinases, it also plays a Btk-independent role in the maintenance of the peripheral B cell population. lyn−/− mice have fewer B cells than did wild-type littermates (12–14). This has been suggested to result from increased negative selection of B cells that are hypersensitive to BCR cross-linking (14). Diminished B cell numbers in Btk−/−lyn−/− mice could be explained by the additive effect of reduced positive selection in the absence of Btk and increased negative selection in the absence of Lyn. However, this is unlikely since lyn−/− B cells do not respond to BCR engagement when they also lack Btk. Lyn is therefore likely to transmit a positive signal for B cell survival that is independent of Btk.

Reduced Life-span of B Cells in the Periphery of Btk−/−lyn−/− Mice.

B cells from both Btk−/− and lyn−/− mice have an increased turnover rate relative to wild-type B cells. The number of long-lived B cells is even further reduced in the absence of both Btk and Lyn. This could be secondary to a block in maturation as the long-lived B cell pool consists predominantly of mature B cells (45). However, this possibility is unlikely as Btk−/− and Btk−/−lyn−/− mice have a similar developmental block at the IgMhiIgDhi to IgMloIgDhi transition. The reduced half-life of Btk−/−lyn−/− B cells could also be a result of impaired positive BCR signaling due to the combined effects of Lyn deficiency on signal initiation and Btk deficiency on signal transmission. The BCR is required for survival of B cells in the periphery (46), and deletion of the cytoplasmic tail of Igα in mice results in a B cell phenotype (4) similar to that of Btk−/−lyn−/− mice. Independent roles for Btk and Lyn in BCR signaling are also supported by the recent demonstration that the Btk/Tec family kinase Itk and the Src family kinase Fyn have independent functions in TCR signaling (47). Alternatively, Btk and Lyn may be redundant for CD40 signaling. Btk−/− lyn−/− mice resemble mice deficient in both Btk and CD40 (48, 49). The impaired response to T cell–dependent antigens would also be explained by failure to transmit CD40 signals (50–52). Finally, defects in homing of Btk−/− lyn−/− B cells to the proper compartments in secondary lymphoid organs could contribute to their poor survival (53).

The Antigen-independent Phase of B Cell Development Is Normal in Btk−/−lyn−/− Mice.

Mice lacking the three Src family kinases Lyn, Blk, and Fyn have a block in development at the proB to preB transition (Tarakhovsky, A., personal communication) similar to that observed in Ig heavy chain– (5) or surrogate light chain–deficient (6) mice. These combined results imply that Src family kinases are redundant for the transmission of preB receptor signals. B lymphopoiesis is also blocked at the preB stage in XLA patients (33), suggesting that Btk is an essential substrate of Src family kinases in human preB receptor signaling. In contrast, the antigen-independent phase of B cell development is normal in Btk−/− mice even in the absence of Lyn. The critical target of Src family kinases in murine preB cells is probably Syk rather than Btk since the proB to preB transition is impaired in syk−/− mice (7, 8).

Lyn Negatively Regulates Btk-dependent Signaling Pathways.

Hypersensitivity to BCR cross-linking in lyn−/− B cells indicates that Lyn plays a critical role in the negative regulation of BCR signaling. Both the failure of Btk−/− lyn−/− B cells to proliferate in response to anti-IgM and the observation that Btk is no longer limiting for response to BCR engagement in the absence of Lyn suggest that Lyn downregulates Btk-dependent signaling pathways. The ability of Btk to promote depletion of intracellular calcium stores in response to BCR cross-linking is prevented by FcγRIIb signaling (27). This inhibition may be mediated by Lyn since FcγRIIb function is partially impaired in lyn−/− B cells (14). The negative regulatory role of Lyn is not limited to Btk-dependent pathways, as BCR-induced activation of the classical mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway does not require Btk (54, 55) but is enhanced in lyn−/− B cells (14).

The transgenic mice expressing low levels of Btk (34) are shown here (Fig. 5 A) to be a useful sensitized system with which to identify negative regulatory components of Btk signaling pathways. Similarly, molecules that contribute positively to Btk signaling could be defined by mutations that further impair BCR signaling in Btklo mice. It will be interesting to determine the effect of mutations in the remaining Src family kinases, BCR signal threshold modulators, and other B cell signaling molecules on the transmission of BCR signals by limiting amounts of Btk.

A Role For Btk in Myeloid Expansion.

A distinguishing characteristic of older lyn−/− mice is the development of splenomegaly due to extramedullary hematopoiesis (12– 14). Surprisingly, although splenomegaly did not occur in old Btk−/−lyn−/− mice, these animals had a similar increase in the frequency of myeloid and erythroid cells as lyn−/− mice. This suggests that the splenomegaly in lyn−/− mice is caused by two separate defects. The first, in which the frequency of splenic myeloid and erythroid cells is increased, is independent of Btk. This phase could result from either a shift in the site of hematopoiesis to the spleen or simply “space filling” (56) secondary to a reduction in the number of lymphoid cells. Myeloid and erythroid elements that are present in lyn−/− spleens then expand in a Btk-dependent manner. Lyn deficiency may render myeloid cells hypersensitive to cytokines, analogous to the reduction of BCR signaling thresholds in B cells. This enhanced response may be attenuated in the absence of Btk. Btk has been implicated as a component of the IL-5 (25, 57, 58), IL-6 (59), and IL-10 (60) cytokine pathways in B cells. However, no alterations in myeloid or erythroid cell development have been reported in xid mice, Btk−/− mice, or XLA patients except for some defects in FcεRI signaling in mast cells (44).

Btk may serve in a general capacity to regulate mitogenic responses and cell survival. These functions would normally be observed only in B cells because of redundant signaling pathways in other lineages. Variation in genetic context or the mutation of other signaling molecules on a Btk−/− background may reveal additional roles for Btk in the development and function of hematopoietic cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Palmer, Fiona Willis, and Prim Kanchanastit for excellent technical assistance and Vivien Chan for technical advice. We are grateful to Dr. John Inman for his gift of TNP-Ficoll. We also thank Julia Shimaoka and Jamie White for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- ALPH

alkaline phosphatase

- BBS

borate-buffered saline

- BCR

B cell antigen receptor

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- Btk

Bruton's tyrosine kinase

- Btklo

mice lacking the endogenous Btk gene and expressing 25% of endogenous levels of Btk in B cells from an Ig heavy chain enhancer/promoter–driven transgene

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- TNP

2,4,6-trinitrophenyl

- me

motheaten

- wt

wild-type

- xid

X-linked immunodeficiency

- XLA

X-linked agammaglobulinemia

Footnotes

Anne Satterthwaite was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Irvington Institute for Immunological Research. Paschalis Sideras is supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (MFR). Owen Witte and Frederick Alt are Investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was partially funded by a US Public Health Service grant (CA-12800; Principal Investigator Randy Wall).

Wasif Khan's current address is Department of Microbiology and Immunology, School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37232-2363.

References

- 1.Goodnow CC. Balancing immunity and tolerance: deleting and tuning lymphocyte repertoires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2264–2271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFranco AL. The complexity of signaling pathways activated by the BCR. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:296–308. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong S, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of an early developmental checkpoint in the B cell pathway by Igβ. Science. 1996;272:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres RM, Flaswinkel H, Reth M, Rajewsky K. Aberrant B cell development and immune response in mice with a compromised BCR complex. Science. 1996;272:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin μ chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitamura D, Kudo A, Schaal S, Muller W, Melchers F, Rajewsky K. A critical role of lambda 5 protein in B cell development. Cell. 1992;69:823–831. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90293-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AM, Rowley B, Pao W, Hayday A, Bolen JB, Pawson T. Syk tyrosine kinase required for mouse viability and B-cell development. Nature. 1995;378:303–306. doi: 10.1038/378303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner M, Mee PJ, Costello PS, Williams O, Price AA, Duddy LP, Furlong MT, Geahlen RL, Tybulewicz VL. Perinatal lethality and blocked B-cell development in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase Syk. Nature. 1995;378:298–302. doi: 10.1038/378298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerner JD, Appleby MW, Mohr RN, Chien S, Rawlings DJ, Maliszewski CR, Witte ON, Perlmutter RM. Impaired expansion of mouse B cell progenitors lacking Btk. Immunity. 1995;3:301–312. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan WN, Alt FW, Gerstein RM, Malynn BA, Larsson I, Rathbun G, Davidson L, Muller S, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA, et al. Defective B-cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–299. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendriks RW, de Bruijn MF, Maas A, Dingjan GM, Karis A, Grosveld F. Inactivation of Btk by insertion of lacZ reveals defects in B cell development only past the pre-B cell stage. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:4862–4872. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hibbs ML, Tarlinton DM, Armes J, Grail D, Hodgson G, Maglitto R, Stacker SA, Dunn AR. Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell. 1995;83:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishizumi H, Taniuchi I, Yamanashi Y, Kitamura D, Ilic D, Mori S, Watanabe T, Yamamoto T. Impaired proliferation of peripheral B cells and indication of autoimmune disease in Lyn-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:549–560. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan VW, Meng F, Soriano P, DeFranco AL, Lowell CA. Characterization of the B lymphocyte populations in Lyn-deficient mice and the role of Lyn in signal initiation and down-regulation. Immunity. 1997;7:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appleby MW, Kerner JD, Chien S, Maliszewski CR, Bondada S, Perlmutter RM. Involvement of p59fyn Tin interleukin-5 receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 1995;182:811–820. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sillman AL, Monroe JG. Surface IgM-stimulated proliferation, inositol phospholipid hydrolysis, Ca2+ flux, and tyrosine phosphorylation are not altered in B cells from p59fyn−/− mice. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;56:812–816. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leitges M, Schmedt C, Guinamard R, Davoust J, Schaal S, Stabel S, Tarakhovsky A. Immunodeficiency in protein kinase Cβ–deficient mice. Science. 1996;273:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarakhovsky A, Turner M, Schaal S, Mee PJ, Duddy LP, Rajewsky K, Tybulewicz VL. Defective antigen receptor–mediated proliferation of B and T cells in the absence of Vav. Nature. 1995;374:467–470. doi: 10.1038/374467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang R, Alt FW, Davidson L, Orkin SH, Swat W. Defective signaling through the T- and B-cell antigen receptors in lymphoid cells lacking the vav proto- oncogene. Nature. 1995;374:470–473. doi: 10.1038/374470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Koizumi T, Watanabe T. Altered antigen receptor signaling and impaired Fas-mediated apoptosis of B cells in Lyn-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:831–838. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C negatively regulates antigen receptor signaling in B cells and determines thresholds for negative selection. Immunity. 1995;2:13–24. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawlings DJ, Scharanberg AM, Park H, Wahl MI, Lin S, Kato RM, Fluckiger AC, Witte ON, Kinet JP. Activation of Btk by a phosphorylation mechanism initiated by Src family kinases. Science. 1996;271:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan S, Fargnoli J, Burkhardt AL, Kut SA, Saouaf SJ, Bolen JB. Src family protein tyrosine kinases induce autoactivation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5304–5311. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahl MI, Fluckiger AC, Kato RM, Park H, Witte ON, Rawlings DJ. Phosphorylation of two regulatory tyrosine residues in the activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase via alternative receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11526–11533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li T, Tsukada S, Satterthwaite A, Havlik MH, Park H, Takatsu K, Witte ON. Activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) by a point mutation in its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Immunity. 1995;2:451–460. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afar DE, Park H, Howell BW, Rawlings DJ, Cooper J, Witte ON. Regulation of Btk by Src family tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3465–3471. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fluckiger A-C, Li Z, Scharenberg AM, Kato RM, Wahl MI, Ochs H, Kinet J-P, Longecker R, Witte ON, Rawlings DJ. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+following B cell receptor activation. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurosaki T, Kurosaki M. Transphosphorylation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase on tyrosine Y551 is critical for B cell antigen receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15595–15598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukada S, Saffran DC, Rawlings DJ, Parolini O, Allen RC, Klisak I, Sparkes RS, Kubagawa H, Mohandas T, Quan S, et al. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vetrie D, Vorechovsky I, Sideras P, Holland J, Davies A, Flinter F, Hammarstrom L, Kinnon C, Levinsky R, Bobrow M, et al. The gene involved in X-linked agammaglobulinemia is a member of the src family of protein- tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1993;361:226–233. doi: 10.1038/361226a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawlings DJ, Saffran DC, Tsukada S, Largaespada DA, Grimaldi JC, Cohen L, Mohr RN, Bazan JF, Howard M, Copeland NG, et al. Mutation of the unique region of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient xid mice. Science. 1993;261:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas JD, Sideras P, Smith CIE, Vorechovsky I, Chapman V, Paul WE. Colocalization of X-linked agammaglobulinemia and X-linked immunodeficiency genes. Science. 1993;261:355–358. doi: 10.1126/science.8332900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satterthwaite AB, Witte ON. Lessons from human genetic variants in the study of B-cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:454–458. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satterthwaite AB, Cheroutre H, Khan WN, Sideras P, Witte ON. Btk dosage determines sensitivity to B cell antigen receptor crosslinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13152–13157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pani G, Siminovitch KA, Paige CJ. The motheaten mutation rescues B cell signaling and development in CD45-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1997;186:581–588. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley SB, Cooke MP, Fulcher DA, Harris AW, Cory S, Basten A, Goodnow CC. Elimination of self-reactive B lymphocytes proceeds in two stages: arrested development and cell death. Cell. 1993;72:325–335. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bona C, Mond JJ, Paul WE. Synergistic genetic defect in B lymphocyte function. I. Defective responses to B cell stimulants and their genetic basis. J Exp Med. 1980;151:224–234. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.1.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bykowsky MJ, Haire RN, Ohta Y, Tang H, Sung SS, Veksler ES, Greene JM, Fu SM, Littman GW, Sullivan KE. Discordant phenotype in siblings with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taurog JD, Moutsopoulos HM, Rosenberg YJ, Chused TM, Steinberg AD. CBA/N X-linked B cell defect prevents NZB B cell hyperactivity in F1 mice. J Exp Med. 1979;150:31–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinberg BJ, Smathers PA, Frederiksen K, Steinberg AD. Ability of the xid gene to prevent autoimmunity in (NZB × NZW)F1mice during the course of their natural history, after polyclonal stimulation, or following immunization with DNA. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:587–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI110651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scribner CL, Hansen CT, Klinman DM, Steinberg AD. The interaction of the xid and megenes. J Immunol. 1987;138:3611–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayakawa K, Hardy RR, Honda M, Herzenberg LA, Steinberg AD, Herzenberg LA. Ly-1 B cells: functionally distinct lymphocytes that secrete IgM autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2494–2498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami M, Yoshioka H, Shirai T, Tsubata T, Honjo T. Prevention of autoimmune symptoms in autoimmune-prone mice by elimination of B-1 cells. Int Immunol. 1995;7:877–882. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hata D, Kawakami Y, Inagaki N, Lantz CS, Kitamura T, Khan WN, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Miura T, Han W, Hartman SE, et al. Involvement of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in FcεRI-dependent mast cell degranulation and cytokine production. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fulcher DA, Basten A. Influences on the lifespan of B cell subpopulations defined by different phenotypes. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1188–1199. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lam K-P, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao XC, Littman DR, Weiss A. Itk and Fyn make independent contributions to T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2069–2073. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oka Y, Rolink AG, Andersson J, Kamanaka M, Uchida J, Yasui T, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H, Melchers F. Profound reduction of mature B cell numbers, reactivities and serum Ig levels in mice which simultaneously carry the XID and CD40 deficiency genes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1675–1685. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.11.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan WN, Nilsson A, Mizoguchi E, Castigli E, Forsell J, Bhan AK, Geha R, Sideras P, Alt FW. Impaired B cell maturation in mice lacking Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) and CD40. Int Immunol. 1997;9:395–405. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renshaw BR, Fanslow WC, III, Armitage RJ, Campbell KA, Liggitt D, Wright B, Davison BL, Maliszewski CR. Humoral immune responses in CD40 ligand–deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu J, Foy TM, Laman JD, Elliott EA, Dunn JJ, Waldschmidt TJ, Elsemore J, Noelle RJ, Flavell RA. Mice deficient for the CD40 ligand. Immunity. 1994;1:423–431. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castigli E, Alt FW, Davidson L, Bottaro A, Mizoguchi E, Bhan AK, Geha RS. CD40-deficient mice generated by recombination-activating-gene-2–deficient blastocyst complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12135–12139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cyster JG, Hartley SB, Goodnow CC. Competition for follicular niches excludes self-reactive cells from the recirculating B-cell repertoire. Nature. 1994;371:389–395. doi: 10.1038/371389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takata M, Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor–mediated activation of phospholipase C-γ2. J Exp Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brorson K, Brunswick M, Ezhevsky S, Wei DG, Berg R, Scott D, Stein KE. Xid affects events leading to B cell cycle entry. J Immunol. 1997;159:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorshkind K, Keller GM, Phillips RA, Miller RG, Bosma GC, O'Toole M, Bosma MJ. Functional status of cells from lymphoid and myeloid tissues in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. J Immunol. 1984;132:1804–1808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hitoshi Y, Sonoda E, Kikuchi Y, Yonehara S, Nakauchi H, Takatsu K. IL-5 receptor positive B cells, but not eosinophils, are functionally and numerically influenced in mice carrying the X-linked immune defect. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1183–1190. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koike M, Kikuchi Y, Tominaga A, Takaki S, Akagi K, Miyazaki J, Yamamura K, Takatsu K. Defective IL-5-receptor–mediated signaling in B cells of X-linked immunodeficient mice. Int Immunol. 1995;7:21–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsuda T, Takahashi-Tezuka M, Fukada T, Okuyama Y, Fujitani Y, Tsukada S, Mano H, Hirai H, Witte ON, Hirano T. Association and activation of Btk and Tec tyrosine kinases by gp130, a signal transducer of the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Blood. 1995;85:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Go NF, Castle BE, Barrett R, Kastelein R, Dang W, Mosmann TR, Moore KW, Howard M. Interleukin 10, a novel B cell stimulatory factor: unresponsiveness of X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency B cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1625–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]