Abstract

Secondary lymphoid tissue organogenesis requires tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and lymphotoxin α (LTα). The role of TNF in B cell positioning and formation of follicular structure was studied by comparing the location of newly produced naive recirculating and antigen-stimulated B cells in TNF−/− and TNF/LTα−/− mice. By creating radiation bone marrow chimeras from wild-type and TNF−/− mice, formation of normal splenic B cell follicles was shown to depend on TNF production by radiation-sensitive cells of hemopoietic origin. Reciprocal adoptive transfers of mature B cells between wild-type and knockout mice indicated that normal follicular tropism of recirculating naive B cells occurs independently of TNF derived from the recipient spleen. Moreover, soluble TNF receptor–IgG fusion protein administered in vivo failed to prevent B cell localization to the follicle or the germinal center reaction. Normal T zone tropism was observed when antigen-stimulated B cells were transferred into TNF−/− recipients, but not into TNF/LTα−/− recipients. This result appeared to account for the defect in isotype switching observed in intact TNF/LTα−/− mice because TNF/LTα−/− B cells, when stimulated in vitro, switched isotypes normally. Thus, TNF is necessary for creating the permissive environment for B cell movement and function, but is not itself responsible for these processes.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor, lymphotoxin, B cell movement, germinal center, follicular structure

he arrangement of lymphocytes into T and B cell zones within secondary lymphoid tissue is designed to optimize interactions between these cells (1). Of particular importance for the shaping of the B cell repertoire are the events that occur at the interface between the two zones, which involve three types of B cells. The first comprises newly generated B cells derived from the bone marrow competing for selection into the recirculating pool. Although the mechanism remains uncertain, this point of selection is critical because the number of such B cells exceeds the number required to maintain homeostasis of the recirculating repertoire (2–4). The second consists of mature naive B cells recirculating through follicles. Third, B cells stimulated by antigen above a critical concentration threshold undergo arrest in the outer periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS)1 (the T zone), where the chance of cognate T cell help is optimal (5, 6). If T cell help is provided, the B cells differentiate into antibody-forming cells, which aggregate within extrafollicular proliferative foci, and intrafollicular germinal centers (GCs [5, 7]). Conversely, should T cell help be absent, as occurs in the case of self-reactive B cells, they die in the outer PALS, leading to tolerance (8, 9).

Mice lacking both membrane-bound and soluble lymphotoxin (LT)α exhibit marked disorganization of the splenic white pulp, and fail to form either LNs or Peyer's patches (10, 11). An even more striking defect has been observed in the spleens from mice with combined deficiencies of TNF and LTα in which virtually no microarchitectural B or T cell aggregation takes place (12, 13). By contrast, LNs do develop in TNF−/− and TNFR-1−/− (p55) mice, but the microarchitecture of their LNs and splenic white pulp is abnormal (13, 14). Members of the TNF and TNFR families also contribute to the events underlying antigen-induced B cell activation and differentiation. Thus, splenic GCs fail to develop in mice lacking either LTα, LTβ, TNF, or TNFR-1 (13–17). Although TNF and LT are critical for normal lymphoid organogenesis, the mechanism whereby they signal the specific migration of lymphocyte subsets remains uncertain. In this paper, the role of TNF compared with LT in regulating movement and positioning of naive and antigen-activated B cells has been investigated in a unique set of inbred C57BL/6-TNF−/− and TNF/LTα−/− mice. The results indicate that TNF derived from a hemopoietic precursor plays a crucial role in development of splenic white pulp, including the T–B interface, but is not itself responsible for correct B cell movement and function within the follicle.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

TNF−/− and TNF/LTα−/− mice were generated using C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells, as described previously (13, 18). Ig transgenic (Tg) B cells were obtained from anti–hen egg lysozyme (HEL) Tg mice (MD4 line [19]). All three lines were established and maintained on an inbred C57BL/6 background. Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 and C57BL/6-Ly5.1 congenic mice were obtained from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia). Mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen–free conditions in the animal facility of the Centenary Institute, Sydney. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee, University of Sydney.

Antibodies and Reagents.

The following reagents were used— mAbs: rat anti–mouse B220 (RA3.6B2, PE-conjugate; PharMingen, San Diego, CA), rat anti–mouse CD4 (RM4-4; PharMingen), rat anti–mouse CD8 (53-6.7; PharMingen), rat anti–mouse CD11b (Mac-1, M1/70; PharMingen), and rat anti-IgE mAbs (R1E4 and B1E3 [20]); specific polyclonal antisera: rabbit anti–hen egg lysozyme (HEL), rabbit IgG anti–Burkitt lymphoma receptor 1 (BLR1 [21]), and anti-IgM and -IgG subclasses (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL); control antibodies: rat IgG2a (PharMingen), biotinylated rat IgG2b (PharMingen), and purified rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA); conjugates: goat anti–rat Texas Red (Caltag Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), goat F(ab′)2 anti–rabbit FITC (Silenus, Melbourne, Australia), rabbit anti–rat horseradish peroxidase (DAKO Pty. Ltd., Botany, NSW, Australia), avidin-FITC (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR), avidin-fluoroblue (Biomedia, Foster City, CA), streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase (DAKO Pty. Ltd.), and peanut agglutinin (PNA)-biotin and PNA-FITC (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). The substrate for alkaline phosphatase was a mixture of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl phosphate (BCIP; Diagnostic Chemicals Ltd., Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada) and nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Horseradish peroxidase–labeled secondary antibodies were developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma Chemical Co.).

TNFR-1–IgG1 fusion protein (TNFR-Ig) consisted of a dimeric human γ1 heavy chain fused to human TNFR-1 (p55; reference 22). The efficacy of in vivo TNF blockade by TNFR-Ig was confirmed by giving groups of WT mice a single injection of 200 μg TNFR-Ig or PBS, followed 21 h later by a lethal combination of 100 μg LPS and 20 mg d-galactosamine. Mice receiving TNFR-Ig showed no effects of endotoxic shock and survived. Untreated mice were dead within 8.5 h (data not shown). Moreover, others have shown (23–25) that administration of TNFR-Ig or LTβR-Ig to adult mice at doses comparable to that used in the present studies (a) affects lymphoid tissue neogenesis and microarchitecture in the developing fetus as well as subsequent GC formation in the offspring (TNFR-Ig and LTβR-Ig), and (b) prevents GC formation in the adult mouse itself (LTβR).

Animal Manipulations.

B cells were prepared, 5-(and -6-)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) labeled, and transferred as described previously (5). For induction of T cell– dependent B cell responses in vivo, mice were immunized with 200 μl i.p. of SRBC (10% vol/vol; provided by Dr. D. Emory, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Sydney, Australia). Radiation bone marrow chimeras were generated as described previously (26). In brief, 2 × 107 bone marrow cells from C57BL/6-TNF−/− (Ly5.2) donors (TNF−/−→ WT) were injected into C57BL/6-Ly5.1 congenic recipients that had been irradiated (5.5 Gy-γ) on days −2 and 0 and vice versa (WT→ TNF−/−). 16 wk after reconstitution, >95% chimerism was confirmed by FACS® analysis of Ly5.1 expression by PBMCs. The mice were used 30 wk after chimera establishment.

Immunohistology.

Fluorescence immunohistology and immunocytochemistry were performed on frozen sections, as described previously (5). Immunohistochemistry double staining was developed using alkaline phosphatase substrate (BCIP/NBT) followed by the horseradish peroxidase substrate DAB. After the final wash, slides were mounted and examined by standard bright-field or epifluorescence microscopy (Leitz DMR BE; Leica AG, St. Gallen, Switzerland).

Flow Cytometry.

Cells were maintained on ice throughout all labeling procedures. 2–5 × 105 aliquots of cells were examined by flow cytometry using a FACScan® (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed with CellQuest software.

B Cell Proliferation and Ig Production In Vitro.

Small dense B cells were prepared from mouse spleen as described previously (27) except for the additional use of anti-CD8 (31M) in T cell depletion. B cells (5 × 105/ml) were incubated in 100 μl B cell medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS [Trace Biosciences Pty. Ltd., Castle Hill, NSW, Australia]) and combinations of T cell membrane (27), recombinant IL-4, membrane from baculovirus-infected Sf 9 cells expressing mouse CD40L (baculo-CD40L [28]), LPS (Salmonella typhosa; Sigma Chemical Co.), and mitogenic anti-IgM (b7.6) and anti-IgD (1.19). Cultures were incubated for 3 d, then pulsed with [3H]thymidine (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA) for 4 h before harvesting and measurement of proliferation by scintillation counting. Triplicate cultures containing baculo-CD40L and IL-4 were incubated for 7 d before supernatant was harvested for measurement of total IgM, IgG1, or IgE by ELISA.

Results and Discussion

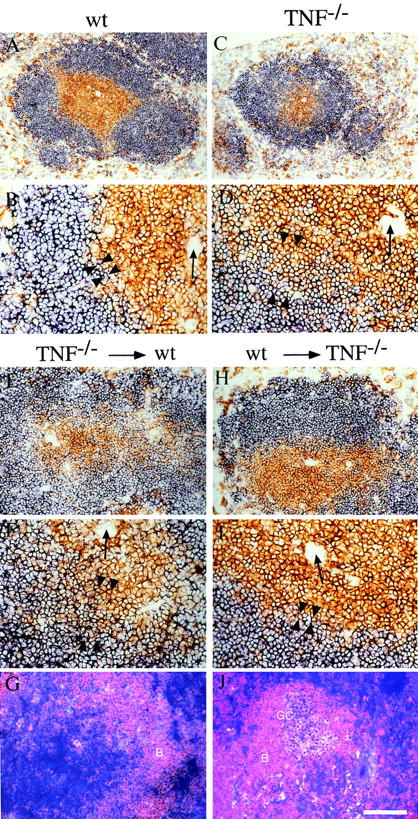

TNF from a Bone Marrow–derived Cell Controls Follicular Tropism of Naive Bone Marrow Emigrants.

Data from our own and other groups point to a role for TNF (and LTα) in establishment of B cell follicles. In TNF−/− mice, B cells are arranged in rim-like structures around the T cell aggregates, and segregation of red and white pulp as well as the interface between T and B cell zones is poorly preserved (13, 14; Fig. 1, A–D). In TNF/LTα−/− mice, the lymphoid aggregates (white pulp) are poorly organized, diminished in size, and overlapping so that clear demarcation between T and B cell zones is lost and there is a relative increase in proportion of lymphocytes within the red pulp (references 12, 13, and data not shown). To clarify the role of TNF in these changes, bone marrow chimeras were created by reconstituting WT animals with TNF−/− bone marrow and vice versa. The white pulp morphology of WT recipients of TNF−/− bone marrow (Fig. 1, E and F) had acquired the features of TNF−/− mice, including a loss of distinct follicles and a blurred T–B cell interface. By contrast, the TNF−/− recipients of WT bone marrow (Fig. 1, H and I) resembled WT mice. A cohort of bone marrow chimeras were immunized with SRBC. Spleens from these mice revealed well-defined PNA+ GCs within the follicles of TNF−/− recipients of WT bone marrow (Fig. 1 J), whereas most B cell aggregates in TNF−/−→ WT bone marrow chimeras showed no evidence of GC formation (Fig. 1 G).

Figure 1.

WT bone marrow restores correct follicular structure and GC reaction in lethally irradiated TNF−/− recipients. (A–D) Spleen sections from unmanipulated 6–10-wk-old animals were stained for a combination of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (brown) and B220+ B cells (blue). (E–J) TNF−/− bone marrow was injected into lethally irradiated WT recipients (E–G) and WT bone marrow into TNF−/− recipients (H–J). 30 wk later, spleen sections were stained by immunohistochemistry for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (brown) and B220+ B cells (blue) (E, F, H, and I), or sections obtained 8 d after immunization with SRBC were stained for B cells (red) and PNA+ GCs (blue/ purple) (G and J). Arrows, Central arterioles; arrowheads, T–B interface. Bar = 400 μm (A and C), 200 μm (E, G, H, and J), or 100 μm (B, D, F, and I).

Thus, TNF derived predominantly from hemopoietic precursors rather than radiation-resistant stromal elements is needed for the development of a normal white pulp capable of supporting subsequent antigen-dependent events within it, including GC formation. Experiments with LTα−/− bone marrow have yielded comparable results (29). Interestingly, the LTα−/−→ WT bone marrow reconstitution was shown to result in the loss of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and GCs but preservation of the demarcation between T and B cell zones (29), which points to an exclusive role for TNF in this latter feature of splenic organization. The results reported here complement the work of Tkachuk et al. (30) in TNFR-1−/− chimeric mice, indicating a requirement for TNFR-1 expression on nonhemopoietic cells in maintenance of splenic architecture and B cell location.

GC Reactions Are Not Dependent on TNF-mediated Signals.

There are two explanations for the dependence of GC formation on TNFR-1 ligation. First TNFR-1 ligation may be required during the cellular interactions after exposure to antigen. Alternatively, it may act during organogenesis to create a permissive environment for later development of GC reactions. To distinguish between these two possibilities, WT mice were immunized with SRBC (day 0) and treated with TNFR-Ig (which binds TNF and soluble LTα3 [22]) on three occasions from day 2 after immunization until 1 d before killing and analysis of GC development. Despite TNF blockade in treated mice, GC reactions had developed normally on day 7 and were indistinguishable from those observed in WT mice treated with PBS (data not shown, but see also reference 25). Furthermore, GCs in the spleens of both types of mice contained organized clusters of FDCs (data not shown). Therefore, TNF-mediated interactions act during development of lymphoid structure to create a milieu wherein GC reactions can then proceed, rather than being involved in the cellular interactions responsible for GC formation per se. One caveat is that TNFR-Ig may not completely block the TNFR-1 signals necessary for GC formation in vivo. However, our own and others' experience argues against this possibility (see Materials and Methods).

Follicular Tropism of Mature Recirculating B Cells Is Dependent on Follicular Composition, not Direct TNF or LTα Signaling.

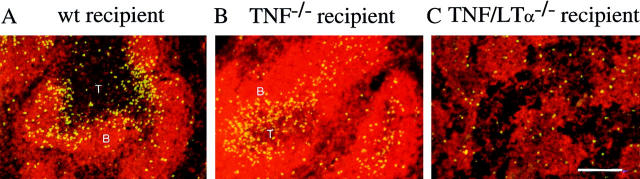

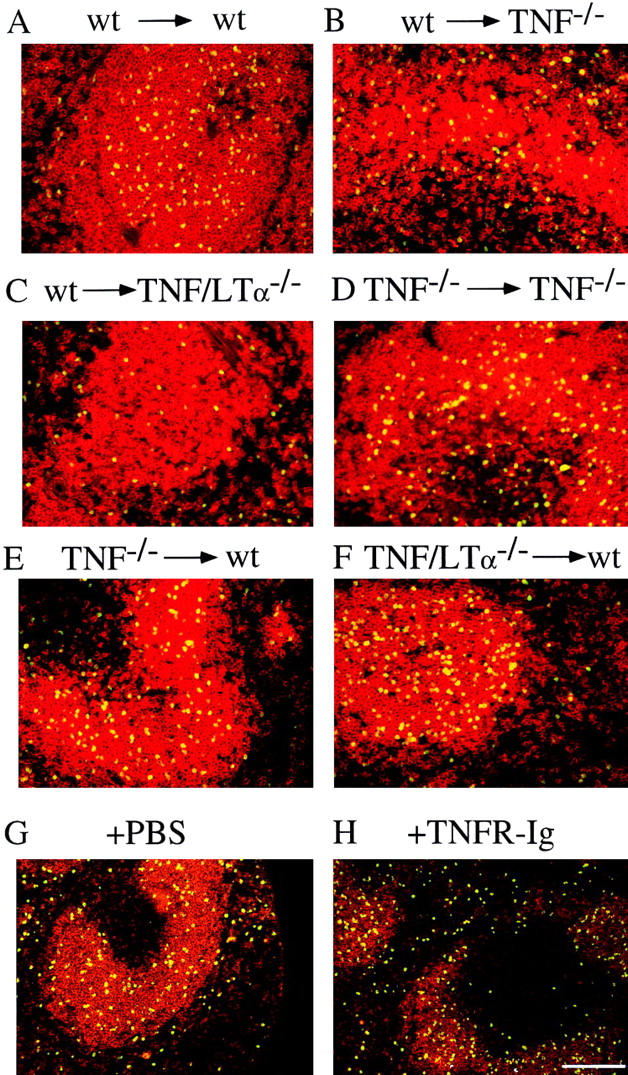

Mature recirculating B cells rapidly enter the follicles after adoptive transfer into nonirradiated WT mice (5, 6). To determine whether the absence of TNF or TNF/LTα perturbs this process, mature naive splenic B cells from WT or TNF−/− donors were labeled with CFSE and transferred into either WT, TNF−/−, or TNF/LTα−/− recipients. The vast majority of WT donor cells were located within WT follicles 24 h after transfer (Fig. 2 A). By contrast, follicular homing was compromised particularly in TNF/ LTα−/− recipients, presumably due to disruption of architecture of the follicle (Fig. 2 C). In TNF−/− recipients, B cells from either WT or TNF−/− donors were largely located in the vicinity of the follicles which were better preserved than in mice lacking both cytokine genes (Fig. 2, B and D). When the experiment was reversed and B cells from either TNF−/− or TNF/LTα−/− donors were transferred into WT recipients, precise B cell migration to the follicles was observed (Fig. 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

Localization of B cells is determined by the splenic environment. (A–E) Purified, CFSE-labeled B cells from WT and mutant mice were transferred into WT, TNF−/−, and TNF/LTα−/− recipients in combinations as indicated. (G and H) Anti– HEL-Ig Tg B cells were transferred at day 0 intravenously to WT recipients immediately after intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 ml PBS (control) or 200 μg TNFR-Ig in 0.5 ml PBS. Spleen sections were stained 20 h after cell transfer for splenic B cells (red) and transferred B cells (CSFE or HEL-specific Ig; yellow). Bar = 200 μm.

These results suggest that TNF plays a role in generation of normal white pulp but does not directly influence homing of naive B cells. To explore this further, naive B cell migration was examined after administration of TNFR-Ig. On this occasion, anti-HEL Ig Tg mice were used as donors, enabling tracking of B cells by virtue of HEL binding to the transgene-encoded surface Ig (follicular tropism of naive Ig Tg B cells was shown previously to be identical to that of non-Tg B cells [5]). WT recipients were injected with either 200 μg i.v. TNFR-Ig or PBS 4 h before Ig Tg B cell transfer. 20 h later, the distribution of HEL-binding B cells in both TNFR-Ig–treated recipients and PBS-treated controls was identical (Fig. 2, G and H), demonstrating precise localization to the B cell follicles consistent with findings obtained in previous transfer experiments.

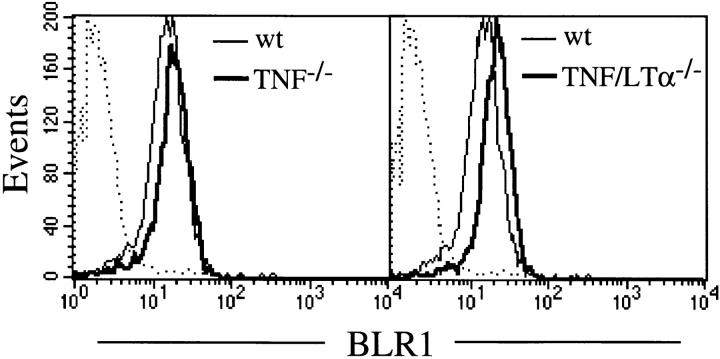

Expression of the BLR1 Chemokine Receptor Is Maintained in the Absence of TNF and LTα.

Once the follicles were established, B cell follicular tropism did not require TNF (Fig. 2 D) or LTα3 (Fig. 2, G and H). This made good sense, particularly given the ubiquitous expression of TNF and the need for a highly focused mechanism to direct intrafollicular B cell traffic. Nevertheless, the necessity for TNF in the recipient follicle suggested that B cell follicular tropism is mediated by a TNF-dependent factor. One attractive candidate was the chemokine receptor BLR1 because it is expressed on naive but not activated B cells (31) and the splenic white pulp of BLR1−/− mice resembles that of TNF−/− and TNFR-1−/− mice (31). Moreover, splenic follicular tropism of recirculating BLR1−/− B cells was shown to be perturbed, whereas migration of WT B cells into the B cell zones of BLR1−/− recipients was normal. To examine the role of BLR1, spleen cells were obtained from WT, TNF−/−, and TNF/LTα−/− mice, and BLR1 expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Dual staining of WT spleen cells for a range of phenotype markers revealed that 95% of B220+ cells expressed BLR1, whereas <3% of CD4+, CD8+, or Mac-1+ cells were positive (data not shown). When BLR1 expression on WT B220 cells was compared with that on the same cells from TNF−/− or TNF/LTα−/− mice, not only were levels maintained in the absence of TNF and LTα, but they also showed a consistent albeit small increase above the control (Fig. 3). Thus, although a role for BLR1 in mediating the effects of TNF (and LT) on primary B cell follicular structure was excluded, the increase in level of expression is consistent with reduced receptor internalization, possibly secondary to a deficit in its recently described ligand, BLC (32).

Figure 3.

BLR1 expression is maintained in the absence of TNF and LT. Spleen cells from WT C57BL/6, TNF−/−, and TNF/LTα−/− mice were dual labeled for B cells (PE anti-B220 mAb) and with either rabbit anti-BLR1 or as a control, rabbit IgG (10 μg/ml) followed by FITC anti– rabbit IgG. Histograms, BLR1 expression of B220+ cells. Dotted line, Rabbit IgG background staining of WT B220+ cells. Background staining of B cells from TNF−/− and TNF/LTα−/− mice was comparable to that of WT mice. Spleen cells derived from groups of three mice were examined individually, and similar results were obtained for each.

Migration of Antigen-stimulated B Cells Is Preserved in TNF− /− but not TNF/LTα− /− Mice.

To follow the physiological migration of B cells to the T zone after antigen ligation of the B cell antigen receptor (5, 8), HEL-specific Ig Tg B cells (TNF and LTα–positive) were stimulated in vitro with 100 ng/ml HEL, and then injected into WT, TNF−/−, or TNF/LTα−/− recipients, where they were detected in the spleen using HEL-specific antiserum. In WT mice, B cells migrated to the outer PALS, where they remained for at least 24 h (Fig. 4 A). Similarly, when activated Ig Tg B cells were transferred into TNF−/− recipients, they arrested precisely in the outer PALS (Fig. 4 B). However, antigenic stimulation had no apparent influence on the migration pattern of B cells transferred into TNF/ LTα−/− recipients. Thus, B cells were distributed randomly throughout the red and white pulp of the recipients (Fig. 4 C), as had been observed previously after transfer of naive B cells into TNF/LTα−/− recipients (Fig. 2 C).

Figure 4.

Activated B cells migrate normally to the outer PALS in TNF−/− mice. Splenic HEL-Ig Tg B cells were isolated and stimulated in vitro for 60 min with 100 ng/ml HEL. Cells were washed and transferred intravenously into WT, TNF−/−, and TNF/LTα−/− recipients. Spleen sections were analyzed 20 h later by staining for B cells (red) and activated HEL-specific Ig Tg B cells (green/yellow). Bar = 200 μm.

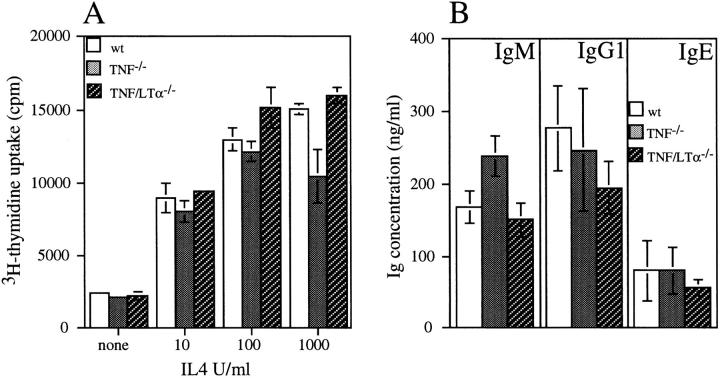

T Cell–dependent B Cell Stimulation In Vitro Is Independent of TNF or LTα.

T cell–dependent B cell responses are grossly impaired in TNF/LTα−/− mice, whereas only some aspects are deficient in the absence of TNF (13, 14). To investigate the possibility that the absence of TNF and/or LT from B cells prevents B cell proliferation and differentiation, purified small resting B cells were prepared from the spleens of both TNF−/− and TNF/LTα−/− mice and stimulated in vitro using protocols that reproduce T cell–dependent and –independent activation. Stimulation with either activated T cell membranes or recombinant CD40L resulted in comparable proliferation of B cells irrespective of whether they were obtained from TNF−/−, TNF/LTα−/−, or WT mice. In each case, proliferation was enhanced by the addition of IL-4 (Fig. 5 A). Similarly, production of IgM, IgG1, and IgE by B cells from both mutant strains was normal in the presence of IL-4 (Fig. 5 B). T cell–independent B cell activation with anti-IgM, anti-IgD, or LPS was also unaffected by either mutation (data not shown).

Figure 5.

B cell proliferation and Ig production after stimulation in vitro. Small dense B cells were prepared from the spleens of WT, TNF−/−, and TNF/LTα−/− mice and incubated in vitro with baculo-CD40L and varying doses of IL-4. (A) After 3 d, cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. (B) B cells were incubated for 7 d with baculo-CD40L and 100 U/ml IL-4. Concentrations of secreted IgM, IgG1, and IgE in the supernatant were measured by ELISA. Histograms in A and B depict mean ± 1 SD of triplicate determinations and are representative of two independent experiments.

The preceding experiments indicate that the failure of isotype switching in TNF/LTα−/− mice is due to loss of T zone tropism by antigen-stimulated B cells in these mice (Fig. 4 C) rather than to an intrinsic defect in the switching mechanism imposed by the absence of these cytokines (Fig. 5). In contrast, the initial phase of the T cell–dependent response to antigen is normal in TNF−/− mice, even though GCs do not develop. The most likely explanation for this is the absence of an organized network of FDCs within the B cell areas. FDC networks have been reported to be absent not only from TNF−/− (13, 14), TNF/LTα−/− (12, 13), and TNFR-1−/− (15, 16, 30) mice but also from LTα−/− mice (16). On the other hand, TNF does not appear to be essential for production of FDCs per se, since TNF−/− mice contain isolated FDCs (13). Interestingly, the source of LTα required for formation of FDC networks has been shown to be the B cell itself, not the T cell (33, 34). Collectively, these findings raise the question of the respective roles played by TNF and LTα in formation of FDC networks and subsequently GC reactions. One possible scenario is that TNF secreted by a cell of hemopoietic origin interacts with TNFR-1+ nonhemopoietic cells, leading to release of the chemokine BLC. This chemokine could then bind to BLR1 on adjacent B cells, leading to both formation of structurally correct follicles (permissive for FDC clustering) and induction of LT expression on B cells, which in turn would facilitate development of FDC networks. The chimera experiments reported here support such a scenario. When LTα was available but TNF was not (TNF−/−→ WT), the extent of the GC reaction was significantly impaired compared with that seen in the presence of TNF (WT→ TNF−/−). That is, the environment was not permissive for FDC clustering because it had been formed in the absence of TNF. By contrast, after immunization, GCs developed normally after administration of TNFR-Ig to (TNF+/+) WT mice with structurally permissive B cell follicles. TNFR-Ig inhibits the activity of soluble LTα3 as well as TNF (22), but the functionally important form of B cell–produced LT for FDC clustering appears to be the membrane-bound LTα1β2 heterotrimer (33), which would have escaped neutralization by TNFR-Ig. Consistent with this is the absence of splenic GCs in LTβ−/− mice (17) despite secretion of soluble LTα3.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D. Godfrey, P. Lalor, B. Scallon, G. Klaus, M. Kehry, B. Castle, H. Briscoe, D. Tarlinton, and B. Fazekas de St. Groth for generously sharing reagents. We appreciate the assistance of Karen Knight, James Croser, J. Webster, D. Strickland, and Danielle Avery.

This work was funded by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society of Australia (to H. Körner and J.D. Sedgwick), a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (to A. Basten and J.D. Sedgwick), a University of Sydney Medical Foundation Program Grant (to P.D. Hodgkin) and postgraduate Scholarship (to M.C. Cook), a National Health and Medical Research Council postgraduate Scholarship (to D.S. Riminton), and a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Australia (to J.D. Sedgwick, held 1992–1996).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BLR1

Burkitt lymphoma receptor 1

- CFSE

5-(and -6-)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- FDC

follicular dendritic cell

- GC

germinal center

- HEL

hen egg lysozyme

- LT

lymphotoxin

- PALS

periarteriolar lymphoid sheath

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

- Tg

transgenic

- TNFR-Ig

TNFR-1–IgG fusion protein

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

M.C. Cook's present address is Department of Immunology, University of Birmingham, Medical School, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK. H. Körner's present address is Institute for Microbiology, Hygiene and Immunology, Wasserturmstrasse 3, D-91054 Erlangen, Germany.

M.C. Cook and H. Körner contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Liu Y-J. Sites of B lymphocyte selection, activation, and tolerance in spleen. J Exp Med. 1997;186:625–629. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lortan JE, Roobottom CA, Oldfield S, MacLennan ICM. Newly produced virgin B cells migrate to secondary lymphoid organs but their capacity to enter follicles is restricted. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1311–1316. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray D. Population kinetics of rat peripheral B cells. J Exp Med. 1988;167:805–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyster JG. Signaling thresholds and interclonal competition in pre-immune B-cell selection. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:87–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook MC, Basten A, Fazekas de St B, Groth Outer periarteriolar lymphoid sheath arrest and subsequent differentiation of both naive and tolerant immunoglobulin transgenic B cells is determined by receptor occupancy. J Exp Med. 1997;186:631–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyster J, Goodnow CC. Antigen-induced exclusion from follicles and anergy are separate and complementary processes that influence peripheral B cell fate. Immunity. 1995;3:691–701. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu YJ, Zhang J, Lane PJ, Chan EY, MacLennan ICM. Sites of specific B cell activation in primary and secondary responses to T cell-dependent and T cell- independent antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyster JG, Hartley SB, Goodnow CC. Competition for follicular niches excludes self-reactive cells from the recirculating B-cell repertoire. Nature. 1994;371:389–395. doi: 10.1038/371389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulcher DA, Lyons AB, Korn SL, Cook MC, Kolerda C, Parish C, Fazekas de St B, Groth, Basten A. The fate of self-reactive B cells depends primarily on the degree of antigen receptor engagement and the availability of T cell help. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2313–2328. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S, Smith SC, Carlson R, Shornick LP, Strauss-Schoenberger J, et al. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks TA, Rouse BT, Kerley MK, Blair PJ, Godfrey VL, Kuklin NA, Bouley DM, Thomas J, Kanangat S, Mucenski ML. Lymphotoxin-α-deficient mice: effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J Immunol. 1995;155:1685–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eugster H-P, Müller M, Karrer U, Car BD, Schnyder B, Eng VM, Woerly G, Le Hir M, di Padova F, Auget M, et al. Multiple immune abnormalities in tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin α double-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 1996;8:23–36. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Körner H, Cook M, Riminton DS, Lemckert FA, Hoek RM, Ledermann B, Köntgen F, Fazekas de St B, Groth, Sedgwick JD. Distinct roles for lymphotoxin-α and tumor necrosis factor in organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2600–2609. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF-α–deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF-α in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Hir M, Blüthmann H, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Müller M, di Padova F, Moore M, Ryffel B, Eugster HP. Differentiation of follicular dendritic cells and full antibody responses require tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 signaling. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2367–2372. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto M, Mariathasan S, Nahm MH, Baranyay F, Peschon JJ, Chaplin DD. Role of lymphotoxin and the type I TNF receptor in the formation of germinal centres. Science. 1996;271:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koni PA, Sacca R, Lawton P, Browning JL, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxins α and β revealed in lymphotoxin β-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemckert FA, Sedgwick JD, Körner H. Gene targeting in C57BL/6 ES cells. Successful germ line transmission using recipient BALB/c blastocysts developmentally matured in vitro. . Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:917–918. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keegan AD, Fratazzi C, Shopes B, Baird B, Conrad DH. Characterization of new rat anti-mouse IgE monoclonals and their use along with chimeric IgE to further define the site that interacts with Fc epsilon RII and Fc epsilon RI. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:1149–1154. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90030-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt KN, Hsu CW, Griffin CT, Goodnow CC, Cyster JG. Spontaneous follicular exclusion of SHP1-deficient B cells is conditional on the presence of competitor wild-type B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:929–937. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scallon BJ, Trinh H, Nedelmann M, Brennan FM, Feldmann M, Ghrayeb J. Functional comparisons of different tumour necrosis factor receptor/IgG fusion proteins. Cytokine. 1995;7:759–767. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Mebius R, Mackay F, Hochman PS. Surface lymphotoxin α/β complex is required for the development of peripheral lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1999–2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Selective disruption of lymphotoxin ligands reveals a novel set of mucosal lymph nodes and unique effects on lymph node cellular organization. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1627–1639. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, Hochman PS, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2033–2042. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riminton DS, Körner H, Strickland DH, Lemckert FA, Pollard JD, Sedgwick JD. Challenging cytokine redundancy: inflammatory cell movement and clinical course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis are normal in lymphotoxin-deficient but not TNF-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1517–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgkin PD, Yamashita LC, Coffman RL, Kehry MR. Separation of events mediating B cell proliferation and Ig production by using T cell membranes and lymphokines. J Immunol. 1990;145:2025–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kehry MR, Castle BE. Regulation of CD40 ligand expression and use of recombinant CD40 ligand for studying B cell growth and differentiation. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:287–294. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto M, Lo SF, Carruthers CJ, Min J, Mariathasan S, Huang G, Plas DR, Martin SM, Geha RS, Nahm MH, Chaplin DD. Affinity maturation without germinal centres in lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:462–466. doi: 10.1038/382462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tkachuk M, Bolliger S, Ryffel B, Pluschke G, Banks TA, Herren S, Gisler RH, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Crucial role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 expression on nonhematopoietic cells for B cell localization within the splenic white pulp. J Exp Med. 1998;187:469–477. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Förster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunn MD, Ngo VN, Ansel KM, Ekland EH, Cyster JG, Williams LT. A B-cell homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt's lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu YX, Huang G, Wang Y, Chaplin DD. B lymphocytes induce the formation of follicular dendritic cell clusters in a lymphotoxin α–dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1009–1018. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez M, Mackay F, Browning JL, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Noelle RJ. The sequential role of lymphotoxin and B cells in the development of splenic follicles. J Exp Med. 1998;187:997–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]