Abstract

Objectives

The UMLS constitutes the largest existing collection of medical terms. However, little has been published about the users and uses of the UMLS. This study sheds light on these issues.

Design

We designed a questionnaire consisting of 26 questions and distributed it to the UMLS user mailing list. Participants were assured complete confidentiality of their replies. To further encourage list members to respond, we promised to provide them with early results prior to publication. Sector analysis of the responses, according to employment organizations is used to obtain insights into some responses.

Results

We received 70 responses. The study confirms two intended uses of the UMLS: access to source terminologies (75%), and mapping among them (44%). However, most access is just to a few sources, led by SNOMED, MeSH, and ICD. Out of 119 reported purposes of use, terminology research (37), information retrieval (19), and terminology translation (14) lead. Four important observations are that the UMLS is widely used as a terminology (77%), even though it was not designed as one; many users (73%) want the NLM to mark concepts with multiple parents in an indented hierarchy and to derive a terminology from the UMLS (73%). Finally, auditing the UMLS is a top budget priority (35%) for users.

Conclusions

The study reports many uses of the UMLS in a variety of subjects from terminology research to decision support and phenotyping. The study confirms that the UMLS is used to access its source terminologies and to map among them. Two primary concerns of the existing user base are auditing the UMLS and the design of a UMLS-based derived terminology.

Introduction

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) sponsors the Unified Medicine Language System (UMLS) 1,2,3 project. The UMLS project addresses pre-existing, fundamental barriers of communication, and the lack of a standard machine-readable terminology in medicine. 3 The UMLS has a large user population. Users are licensed by NLM and are supported by a UMLS user mailing list. 4 The UMLS serves to bridge the conceptual gap between user questions and the effective retrieval of relevant machine-readable biomedical information. The UMLS is a set of machine-readable knowledge sources. It comprises the UMLS Metathesaurus 5,6 which contains 1.3 million concepts derived from a variety of more than 100 existing biomedical vocabularies and classifications; the Semantic Network 7 is a reference representing Semantic Types and sensible relationships among them; and the SPECIALIST lexicon, which provides the lexical information needed for the SPECIALIST Natural Language Processing System. 8 An expected UMLS application, from the time of its creation, was to support interface programs that emulate the function of an expert reference librarian, to help users access a broad range of information. According to Humphreys et al., 2 the basic uses of the UMLS include: the controlled vocabulary function of the Metathesaurus and the Semantic Network; enhancing information retrieval from various sources as well as mapping among them; and support for Natural Language Processing.

Over the past two decades, the UMLS has grown steadily to become the largest existing collection of medical terms. From a computer science perspective in the context of ontologies, the UMLS is viewed as a well-developed, usable, very large ontology with a long lifespan, making it useful in multiple projects. 9,10 The UMLS has been distributed to many health care organizations. Every year, a substantial number of papers are published about the UMLS. 11,12,13 However, it is difficult to find a literature description of what the UMLS is actually used for, by whom, and how. Was the UMLS used as initially expected? Which features proved useful? What extra features are desired by users?

Hollis 14 addressed some issues of UMLS usage briefly in her survey composed of seven questions that required free-text answers. None of the questions concerned expectations and possible improvements of the UMLS. As in the present study, Hollis’ survey was distributed through the UMLS user mailing list. 4 Only ten responses were received by Hollis, which makes it hard to discern UMLS users’ general opinions. The present study attempted to shed additional light on the user population of the UMLS, how the UMLS is used and users’ preferences.

In particular, we are interested in examining the intended use of the UMLS versus actual use reported by the respondents. For example, the UMLS was designed as an ontology supporting access to and mappings among over 100 medical source terminologies. 2 To what extent is the UMLS used for these purposes?

Furthermore, starting with the first of its 2004 releases, the Metathesaurus’s Rich Release Format (RRF) 15 represented sources “transparently.” That is, both users and applications can access UMLS source vocabularies’ content without loss of information. The concept-based abstractions in the Original Release Format (ORF) prevented the complete and reliable extraction of a few sources because of differences between the Metathesaurus concept-based representation and the code-based nature of those sources. This small loss of information has been eliminated in RRF. For instance, a distinction between a source’s inter-term or inter-code relationships and the information added in the creation of the Metathesaurus is made. 16 Do users utilize the transparent access to sources? Which sources are accessed most? Which subject areas of the UMLS are extensively used and for which areas do UMLS users wish to extend the coverage? The UMLS was not designed to be a terminology. However, following messages posted to the UMLS user mailing list, 4 anecdotal evidence emerged documenting UMLS use as if it were a terminology. What percentages of the users use the UMLS as a terminology? If this percentage is indeed high, as we had hypothesized, 17 would those users like the NLM to design a terminology derived from the UMLS? In this derived terminology, the information about the occurrence of terms in source terminologies would be removed. Thus, inconsistencies found in the UMLS could be removed from the derived terminology. Note that information regarding occurrence in source terminologies will still be available to a user in the UMLS, which will not change. For more ideas for such a terminology design, see Perl and Geller, 2003. 17

Due to the UMLS being integrated from many source terminologies as well as its size and complexity, it is unavoidable that some classification errors and inconsistencies have been introduced. Recent years have seen a surge in publications discussing techniques for auditing the UMLS. 18–26 Do users care about errors in the UMLS and which ones concern them most?

We examined users’ opinions regarding two interface features, one offered by NLM and the other suggested in the survey. To get a deeper understanding of the results, we used sector analysis for some questions. Finally, we asked users what percentages of a putative UMLS budget should be allocated to different tasks. In this report, we present important UMLS-related issues with the intention of providing the NLM and UMLS users with constructive feedback regarding future potential development of the UMLS. This study was neither initiated nor supported by the NLM to assure its independence.

Methods

We designed a 26-question survey, consisting of three parts. The first part ascertained demographics and employment information of UMLS users. The second part elicited various aspects of use of the UMLS. The last set of questions concerned the “UMLS agenda” and challenged the users to express their priorities. The third part, which is more complex and includes explanations, appears in Appendix II (available as a JAMIA online data supplement at www.jamia.org). To review the entire questionnaire, see www.cis.njit.edu/∼oohvr/new/umlsstudy.doc. For some questions, (e.g., user professions, highest educational degrees, mode of use and kind of host systems), multiple responses were allowed.

We sent the questionnaire to the UMLS user mailing list maintained by the NLM. 4 This mailing list had about 600 members at the time. Participants were assured complete confidentiality of their replies. To further encourage list members to respond, we promised to provide them with early results prior to publication. After an initial deadline, we extended the deadline and sent reminders.

As opposed to Hollis’ UMLS study, we kept the number of open-ended questions to a minimum, in order to minimize the efforts and response time of respondents and to increase the number who would respond. All but four questions allowed the respondents to choose among a few given options, although a choice “Other” was given. For the four remaining questions, we did not want to bias the respondents, and allowed them to enter their own free-text responses.

For some questions, we used sector analysis, where we analyze the answers by the employment types of the respondents, to gain better insights into the responses.

We used tables to display the absolute values (and in parentheses the percentages) of the options for the various questions. This duality of the numerical data is especially helpful in cases of multiple answers where the percentages add up to more than 100%. For displaying results of a sector analysis, both segmented (stacked) bar charts 27 and tables were used. They helped to visually highlight the options where some sectors display a digression from the results for the overall population of the study.

Results

There were 70 respondents to our questionnaire. A 50% increase of initial submissions was achieved by sending a reminder and extending the deadline.

Demographics and Employment

The majority of respondents, 70%, are from the USA, followed by 20% from Europe, 4.3% from Canada, and the rest from other continents. ▶ (in the Appendix I) shows users’ age distribution. The largest age group is 51–60. The users’ highest education level is shown in ▶. About 21% of users have 2 highest degrees (i.e., not in the same field), out of which, 9% have Ph.D. and M.D. degrees, 9% have Master’s and M.D., and 3% have Master’s and Ph.D. degrees. Hence, among those who have 2 degrees, 86% have M.D. degrees. The average number of degrees reported per user is 1.2.

Table 1.

Table 1 Highest Education Level

| Degree | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Master | 27 (39%) |

| Ph.D. | 23 (33%) |

| M.D. | 23 (33%) |

| Bachelor | 5 (7%) |

| Others | 3 (4%) |

The first employment question was on users’ professions, as shown in ▶. On average, a user listed 1.8 professions, with 37% listing multiple professions. About 23% listed 2 professions. One respondent listed 5 professions: engineer, manager, professor, programmer, and researcher. We further asked for the employment sectors in which they are active (see ▶). ▶ shows the sector distribution of the 36% employed in industry. About half of industry employees are from software vendors. As for the organization size, more than half of the organizations, mainly universities, have over 1,000 employees (see ▶).

Table 2.

Table 2 Professions

| Profession | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Researcher | 33 (47%) |

| Programmer | 16 (23%) |

| Physician | 15 (21%) |

| Professor | 12 (17%) |

| Student | 11 (16%) |

| Manager | 8 (11%) |

| Nurse | 5 (7%) |

| Librarian | 4 (6%) |

| Administrator | 4 (6%) |

| Engineer | 3 (4%) |

| Other | 12 (17%) |

Table 3.

Table 3 Employment Sectors

| Organization | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| University | 34 (49%) |

| Industry | 25 (36%) |

| Government | 6 (9%) |

| Self-Employed | 2 (3%) |

| Research Institution | 1 (1%) |

| Others | 2 (3%) |

Table 4.

Table 4 Industry (36%, see ▶) Sectors

| Employer Type | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| SW Vendor | 11 (44%) |

| Hospital | 6 (24%) |

| Health Information Processing | 3 (12%) |

| Insurance | 2 (8%) |

| Doctor’s Office | 1 (4%) |

| Pharmaceutical Company | 0 (0%) |

| Others | 2 (8%) |

The Uses of the UMLS

-

1 Length of Experience with UMLS

More than 1/3 (37%) of users have used the UMLS less than a year, 24% and 22% have used the UMLS 2∼4 years and 5∼7 years, respectively, while 17% have been users for 8 years or more.

-

2 Subject Areas

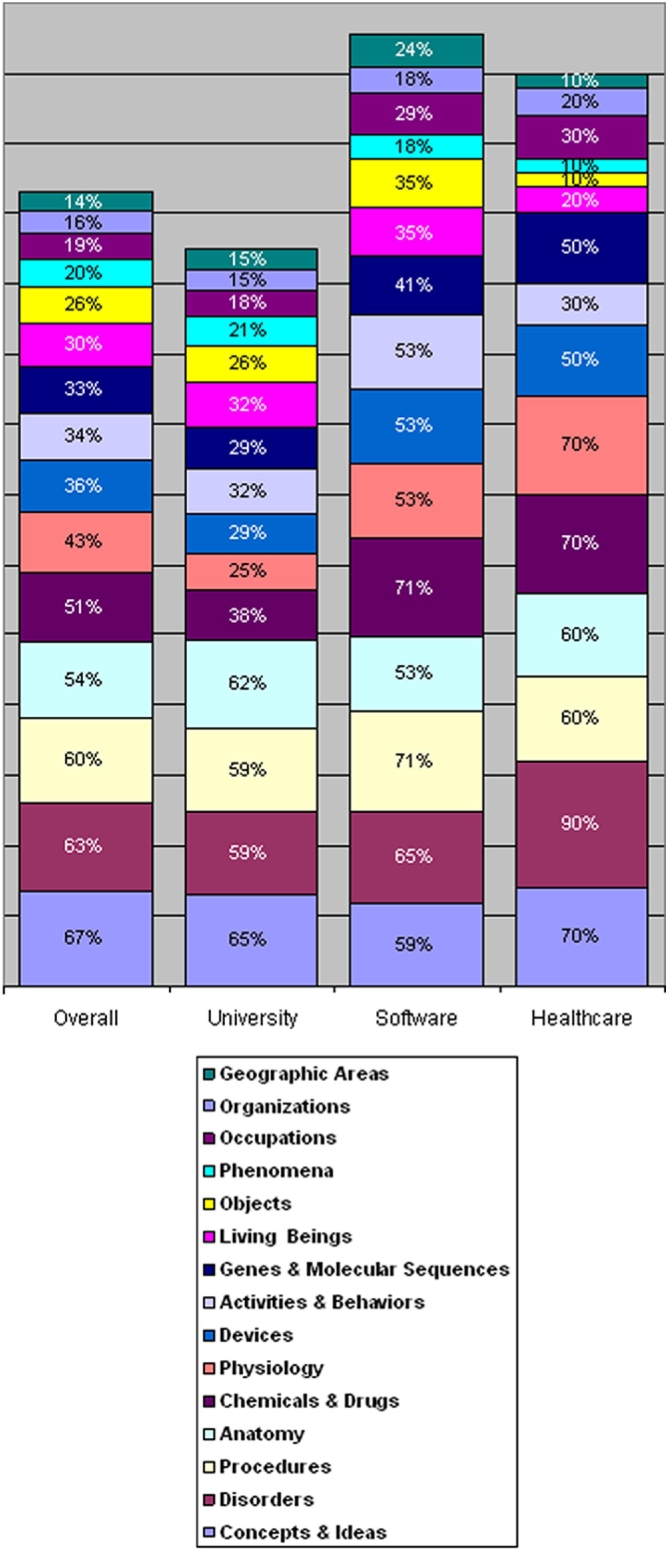

We listed 15 subject areas in the questionnaire, based on the partition of the Semantic Network in the NLM UMLS Web site.28▶ shows segmented bar charts with the subject area percentages of use for the overall study population and for the population of three kinds of employment organizations. On average, respondents reported using 5.7 areas, and each subject area is used by 47% of the users. The sector analysis shown in ▶ and ▶ distinguishes the use of the subject areas among those working in universities, software companies and health care organizations compared to the overall results. (Software companies consist of Software Vendors, Health Information Processing companies and Insurance companies while health care organizations consist of Hospitals and Doctor’s Offices.) The combination of similar employment organizations into the broader groups of software companies and health care organizations helps to obtain a clearer picture of the distribution by combining small groups like doctor’s offices into larger similar groups, like hospitals. ▶ shows the distribution of the user numbers according to the number of areas selected. Only seven users were interested in all 15 areas. The leading subject areas with over 60% interest across all sectors are Concepts and Ideas, Disorders, and Procedures.

-

3 Mode of Operation

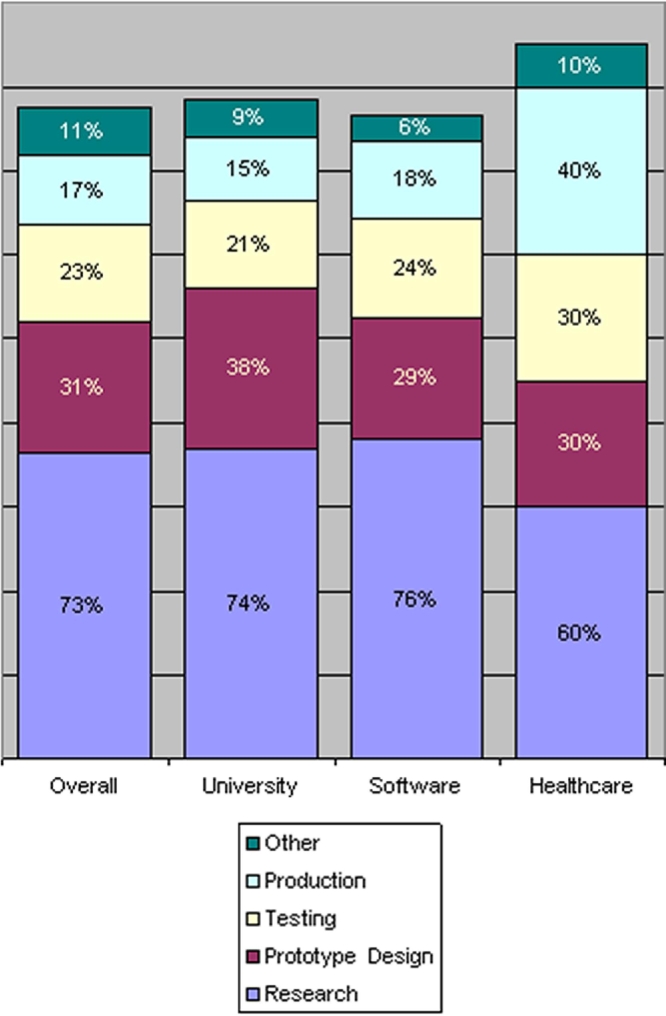

▶ illustrates the sector analysis for the modes of operations. Note that the percentages in each segmented bar add up to more than 100% since some users use the UMLS in multiple modes. The same phenomena appear for all three issues for which we conducted sector analysis (▶).▶▶ shows this information numerically.

-

4 Host Systems for UMLS Use

The UMLS is a collection of vocabularies and tools. It is not, by itself, a working software system. However, programmers may incorporate the information contained in the UMLS into other fully functional software systems. We refer to such a software system as the “host system” of the UMLS. ▶ shows the kinds of host systems in which the UMLS is used. An average of 1.9 kinds per respondent was reported. Half of the users use the UMLS in Medical Research Systems. Less common host systems were Clinical Information Systems and Terminological Systems, both with 40%.

-

5 Purposes of UMLS Use

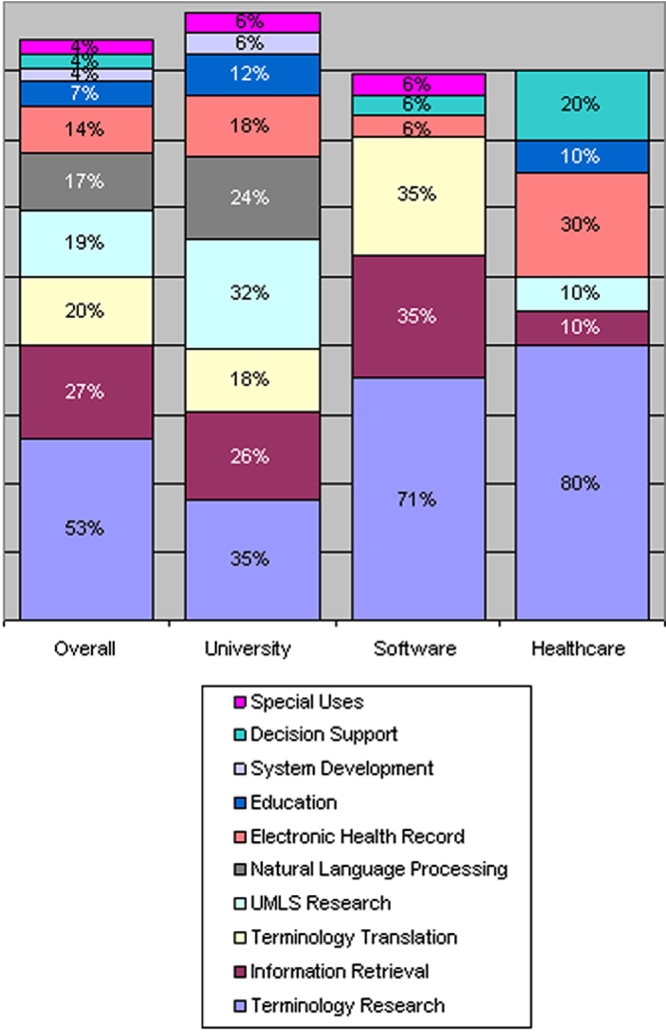

Many users reported multiple uses of the UMLS, resulting in a total of 119 uses. ▶ gives several examples of the original responses for each category. ▶ and ▶ show sector analysis of categories of use by user workplace. Note that the percentages may add up to more than 100%, since users listed multiple uses.

-

6 Access to UMLS Source Terminologies

We found that 80% of users access the UMLS source terminologies, such as CPT (Current Procedural Terminology), ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems), MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), SNOMED (Systematic Nomenclature of Medicine), NDF-RT (National Drug File-Reference Terminology), etc. About four fifths of answers from 104 responses are made up of just four terminologies, SNOMED (32), MeSH (23), ICD (21), and CPT (8), while LOINC (Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes) (4), and RxNORM (a standard terminology for drug products) (3) follow. Other terminologies mentioned twice are NANDA (North American Nursing Diagnosis Association Taxonomy), NCI (National Cancer Institute Thesaurus), NIC (Nursing Interventions Classification), and mentioned once are ALT (Alternative Billing Concepts), DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), GO (Gene Ontology), HL7 (Health Level Seven Vocabulary), MED (Medical Entities Dictionary), RUS2002 (Russian Translation of MeSH) and UWDA (University of Washington Digital Anatomist).

Effective with the first 2004 release, the Metathesaurus’ Rich Release Format represents sources “transparently.” Only 20% are using the UMLS transparency feature, while 56% of the respondents plan to use this feature in the future.

-

7 Using the UMLS as a Mapping Tool

About 44% of the respondents are using the UMLS as an ontology, supporting mappings between its various source terminologies.2

-

8 Use of the UMLS as a Terminology

A full 77% of respondents verified that they are using the UMLS as a terminology, even though it was not designed to be a terminology.

Figure 1.

Percentages of Subject Areas Usages by User Workplace.

Table 5.

Table 5 Percentages of Subject Areas Usages by Organizations

| Overall | University | Software | Healthcare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities & Behaviors | 34 | 32 | 53 | 30 |

| Anatomy | 54 | 62 | 53 | 60 |

| Chemicals & Drugs | 51 | 38 | 71 | 70 |

| Concepts & Ideas | 67 | 65 | 59 | 70 |

| Devices | 36 | 29 | 53 | 50 |

| Disorders | 63 | 59 | 65 | 90 |

| Geographic Areas | 14 | 15 | 24 | 10 |

| Genes & Molecular Sequences | 33 | 29 | 41 | 50 |

| Living Beings | 30 | 32 | 35 | 20 |

| Objects | 26 | 26 | 35 | 10 |

| Occupations | 19 | 18 | 29 | 30 |

| Organizations | 16 | 15 | 18 | 20 |

| Phenomena | 20 | 21 | 18 | 10 |

| Physiology | 43 | 25 | 53 | 70 |

| Procedures | 60 | 59 | 71 | 60 |

| Average | 38 | 36 | 45 | 43 |

Figure 2.

Percentages of Modes of Operation by User Workplace.

Figure 3.

Percentages of Purpose of UMLS Uses by User Workplace.

Table 6.

Table 6 Percentages of Modes of Operation by Organizations

| Overall | University | Software | Health Care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | 73 | 74 | 76 | 60 |

| Prototype Design | 31 | 38 | 29 | 30 |

| Testing | 23 | 21 | 24 | 30 |

| Production | 17 | 15 | 18 | 40 |

| Other | 11 | 9 | 6 | 10 |

| Average | 31 | 31 | 31 | 34 |

Table 7.

Table 7 Host Systems for the UMLS

| Host Systems | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Medical Research | 35 (50%) |

| Terminological | 28 (40%) |

| Clinical Information | 28 (40%) |

| Decision Support | 23 (33%) |

| Billing | 3 (4%) |

| Others | 12 (17%) |

Table 8.

Table 8 Original Response Examples

| Category (Total Number in Category) | Selected Example Original Text in this Category |

|---|---|

| Terminology Research (37) | General terminology browsing |

| Assure consistent use of terminology | |

| Procedure names | |

| Building medical ontologies | |

| Source of synonyms | |

| Foundation for Vocabulary Management and natural language processing of medical standard terminology for public health integrated systems | |

| Semantic network extract and modeling | |

| Provide concept search interface | |

| Information Retrieval (19) | Data content searches |

| Conceptual text indexing | |

| Text mining of biological literature | |

| Indexing medical documents | |

| Terminology Translation (14) | Mapping concepts across vocabularies |

| Match own terminology to commonly accepted codes | |

| Multilingual to English translations for queries to Entrez-PubMed | |

| UMLS Research (13) | Auditing the UMLS |

| Study mappings between terminological systems | |

| Study of Metathesaurus structure using Complex Network theory. | |

| Research on terminology coverage | |

| Electronic Health Record (10) | Building problem lists using UMLS concepts |

| Providing a unified method for storing information and knowledge in an EMR | |

| Relate UMLS vocabularies to EHR models associated attributes | |

| Natural Language Processing (8) | Collecting linguistic knowledge for Natural Language Processing |

| Parsing medical abstracts | |

| Create lexicon files for NLP | |

| Education (5) | Building an ontology for a medical education system |

| Educational resource for Informatics program | |

| Decision Support (3) | Decision support modeling |

| Mark up oncology guidelines | |

| System Development (3) | Creating a clinical trials scheduling system |

| Development of a speech ordering system for tests, meds, imaging, etc. | |

| Billing (1) | Drug-disease linkages for billing purposes |

| Definitions (1) | Source of Definitions and cross-maps used on Diseases Database Website |

| Adverse Events (1) | Coding Adverse event terms for clinical trials |

| Knowledge Management (1) | Storing, presentation and processing of knowledge |

| Phenotyping (1) | Phenotyping |

Table 9.

Table 9 Percentages of Purpose of UMLS Uses by Organizations

| Overall | University | Software | Health Care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 7 | 12 | 0 | 10 |

| Electronic Health Record | 14 | 18 | 6 | 30 |

| Information Retrieval | 27 | 26 | 35 | 10 |

| Natural Language Processing | 17 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| UMLS Research | 19 | 32 | 0 | 10 |

| System Development | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Terminology Research | 53 | 35 | 71 | 80 |

| Terminology Translation | 20 | 18 | 35 | 0 |

| Decision Support | 4 | 0 | 6 | 20 |

| Special Uses | 4 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| No answers | 16 | 15 | 24 | 10 |

| Average | 17 | 17 | 17 | 15 |

Agenda

-

1 Derived Terminology

Almost 73% of respondents stated that they would like the NLM to design a terminology derived from the UMLS.

-

2 Expanding the UMLS Coverage

We found that users would like the NLM to expand the UMLS coverage in 25 areas. The leading requested areas are Genomics, Biology and Finding with 6, 5 and 4 respondents respectively. Three users requested the following areas: Drugs, Mapping, Globalization, Procedures, Signs and Symptoms, Sociology and Therapy, while two requested Coding Systems, Diseases and Disorders. Eleven other areas, not listed, were from just one respondent.

-

3 Modeling Errors

▶ shows the average level of (users) concerned with different kinds of modeling errors. Six kinds of modeling errors were offered, namely concept redundancy,18 concept polysemy (also called ambiguity),19 wrong hierarchical relationships,19,20 wrong associative relationships, wrong semantic type assignments21,22 and redundant semantic type assignments.23,24 We listed “not at all,” “a little,” “moderately” and “a lot” as the choices indicating the level of concern. When analyzing the data, we assigned an integer score 0, 1, 2 or 3 to each choice, respectively. The average concern level for all modeling errors is 1.72. The leading errors for which users are moderately concerned are wrong semantic type assignment and wrong associative relationships.

-

4 Missing Terminological Knowledge Elements

▶ shows the average concern level for missing knowledge elements such as missing concepts,25,26 missing definitions, missing synonyms,26 missing hierarchical relationships,25,26 missing associative relationships26 and missing semantic type assignments.25 The average concern level for all missing knowledge elements is 1.57. The combined average concern level for both wrong and missing knowledge elements is 1.65.

-

5 Interface

Our results show that 73% of participating users would want the NLM to enhance the UMLSKS META interface to mark a concept with multiple parents with a “*” in the indented hierarchy (similar to the way MS Windows marks a directory with children by a “+”), 19% chose “No.” There were 74% of the respondents who wanted to see the Semantic Navigator maintained for future releases,† while 16% answered “No.” We challenged the users to suggest other enhancements they might want to see. Only 10% of the respondents answered this question and their replies varied widely. Some suggested a better interface without offering specifications. Some requests were for better integration of foreign languages, transparent mapping, and software to assist those who want to contribute groups of new/missing terms to fill gaps in the UMLS. Some answers were irrelevant.

-

6 Goals for UMLS Development

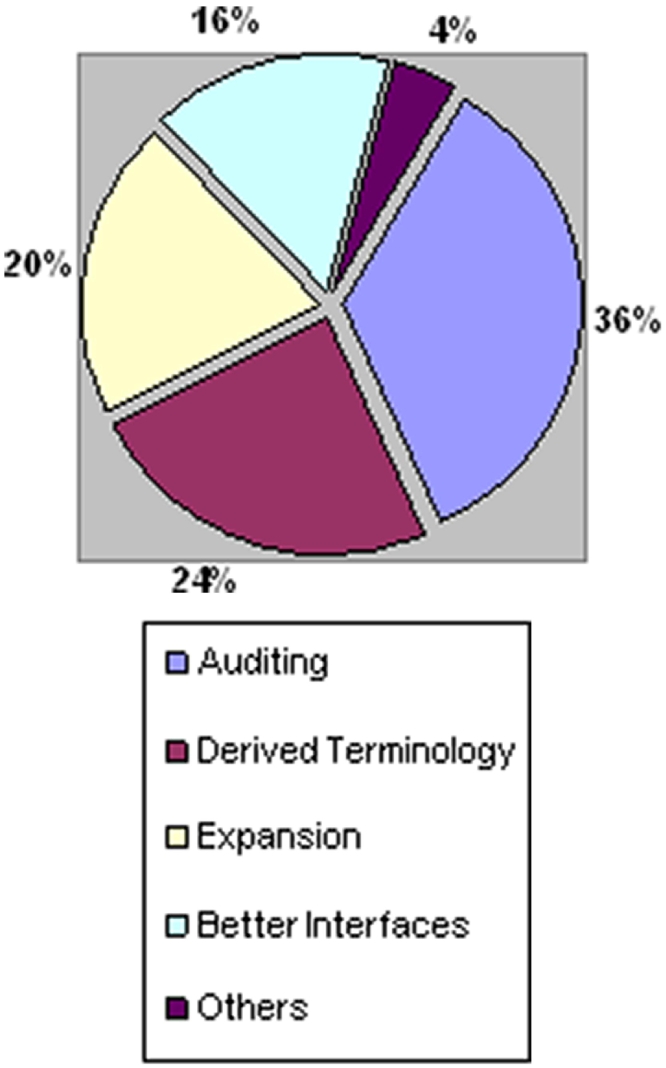

UMLS users expressed what percentages of a putative NLM budget for the UMLS should be allocated to Auditing, Derived Terminology Development, Expansion of New Subject Areas, Better Interfaces, and Others (▶).

Table 10.

Table 10 Average Concern Levels about Modeling Errors ∗

| Wrong Semantic Type Assignments | 2.14 |

| Wrong Associative Relationships | 2.11 |

| Wrong Hierarchical Relationships | 1.97 |

| Concept Redundancy | 1.53 |

| Redundant Semantic Type Assignments | 1.3 |

| Concept Polysemy | 1.26 |

∗ 3 = A lot, 2 = Moderately, 1 = A little, 0 = Not at all.

Table 11.

Table 11 Average Concern Levels about Missing Knowledge Elements ∗

| Missing Hierarchical Relationships | 1.86 |

| Missing Semantic Type Assignments | 1.76 |

| Missing Synonyms | 1.51 |

| Missing Concepts | 1.45 |

| Missing Associative Relationships | 1.45 |

| Missing Definitions | 1.43 |

∗ 3 = A lot, 2 = Moderately, 1 = A little, 0 = Not at all.

Figure 4.

Desired Budget Allocation.

Discussion

Demographics and Employment

The vast majority of UMLS users are from the USA (45 respondents), followed by Germany (6), Canada (3), and France (2). In spite of the efforts to supply multi-language support for the UMLS, only limited interest (30%) was shown outside of the USA. About 60% of UMLS users are above 40 years old. As a group, UMLS users are highly educated with 59% holding Ph.D. or M.D. degrees. This is consistent with the result that the top profession of respondents is researcher, followed by programmer, physician, professor, and student. We understand the heavy use of “researcher” to mean that some users interpret “researcher” in a broad way. This is especially true when some users considered themselves to be in multiple professions.

Uses of the UMLS

Five of the top six areas used are biomedical subjects, as expected, since the UMLS covers the medical field. The leading interest in the abstract subject of Concepts and Ideas is surprising. First, the UMLS is used mainly for medical knowledge, so an interest in a non-medical subject is surprising in this context. Second, one might expect UMLS users to typically have interest in concrete knowledge rather than ideas and conceptual knowledge. Health care employees lead the interest in Disorders, Physiology, Concepts and Ideas, and Genes & Molecular Sequences. University employees lead in Anatomy and Phenomena. Software companies lead in interest in all other subjects and are especially interested in Procedures as well as Chemicals and Drugs.

We found that in all sectors, the UMLS mode of operation is mainly for research, by a wide margin. Of special interest is that overall, 17% report using the UMLS in production, where health care employees report 40%.

In terms of the purposes of using the UMLS, Terminology Research is the primary purpose for all of the organization categories. Universities lead in most categories, such as Education, Natural Language Processing (NLP), UMLS research, and System Development; software companies lead in Information Retrieval and Terminology Translation while health care organizations use Electronic Health Record (EHR) and Terminology Research most.

Three-quarters of users access the UMLS source terminologies as originally intended. In view of this result one would expect that users are extensively utilizing the transparent access to source terminologies added in 2004. This feature enables a user to obtain, through the UMLS, a source terminology, as originally created. However, use of transparent access is spreading slowly. Only about 20% from the 75% of the users accessing source terminologies use transparent access, although more than 50% intend to use it. Perhaps more aggressive advertising by NLM, of this recent feature, will make it more popular. Software company employees lead in accessing the UMLS source terminologies transparently.

Actual access that was reported was limited to just 17 source terminologies, and just four, SNOMED, MeSH, ICD, and CPT, accounted for 80% of the responses. Users do not seem to review the other source terminologies’ internal representations of UMLS concepts, as speculated in Perl and Geller, 2003. 17

A main finding of our study is that the UMLS is used more as a terminology, an unintended use, than as a mapping mechanism between sources, an intended use, 3 by a ratio of 7:4. Universities lead in using the UMLS as a mapping tool (47%). Health care employees are most likely to use the UMLS as a terminology (90%).

Future Agenda

We found that 49 out of the 53 users using the UMLS as a terminology, and two others, want the NLM to derive a terminology from the UMLS. Health care and university employees are most interested and software companies are least interested in the derived terminology. Genomics is leading in the request for expanded coverage, showing users’ preference for more genomic concepts. To achieve this, the NLM needs to integrate more genomic source terminologies into the UMLS, beyond the integration of GO. 30,31 Most other requested subjects are already represented in the UMLS, except for mapping and globalization.

Wrong or missing semantic type assignments, hierarchical relationships, and associative relationships concern users more than other errors. Missing knowledge elements concern users less than modeling errors.

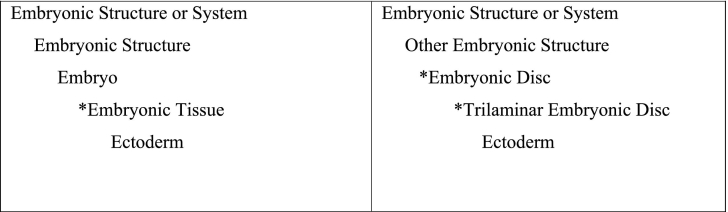

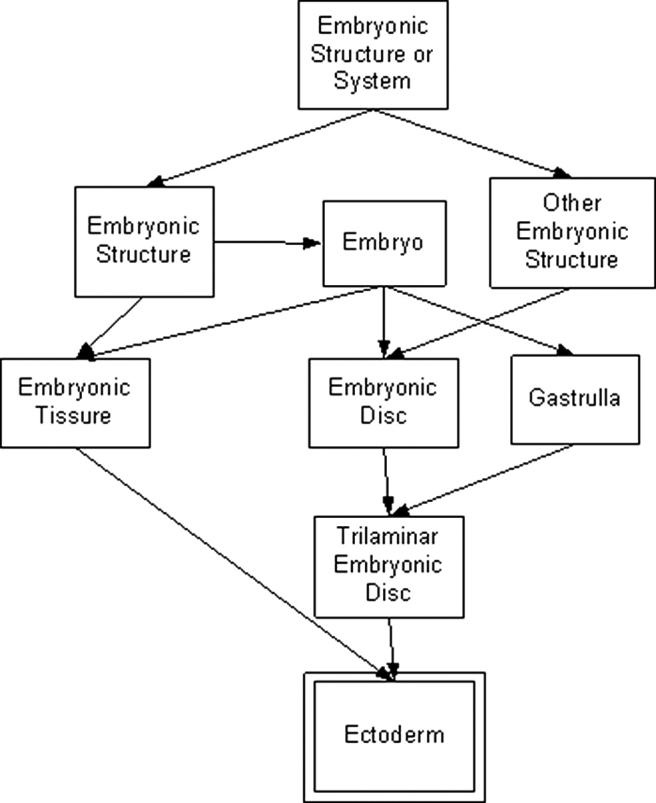

Users show substantial interest in the Semantic Navigator and in the need for an interface indicating multiple parents. It would definitely be helpful if the META interface were improved to support such a feature in the indented hierarchy display. Let us further illustrate the benefit of indicating ancestors with multiple parents in the indented list showing ancestors in the META interface. The existing UMLSKS META Web interface suffers from overwhelming redundancy. First, the parents and ancestors are listed for each UMLS source terminology, causing a lot of repetition. Even though it makes sense to describe the hierarchy for each UMLS source, for a user who does not care about the sources, the repetition is overwhelming. Second, even for each source separately, each different ancestral path is listed and parents are listed multiple times in the parent list according to their appearances in the ancestral paths. To illustrate this, we show the data for just one source terminology, the NCI for the concept Ectoderm. ▶ shows the ancestors of Ectoderm, limited to NCI, using the style of the Semantic Navigator interface. As we see, Ectoderm has two parents Trilaminar Embryonic Disc and Embryonic Tissue. Each of these parents in turn has two parents. Furthermore, Embryonic Disc, a grandparent has also two parents. Altogether there are five ancestral paths from Ectoderm to Embryonic Structure or System in ▶. Each of these paths is fully displayed in the UMLSKS interface. Furthermore these repetitions appear when listing the five parents. Moreover the same four children of Ectoderm are listed five times according to the five(!) paths. Note that all this information is given even though the user asked only about Ectoderm.

Figure 5.

The (NCI) Ancestors of Ectoderm Shown according to the Semantic Navigator Style.

According to our proposal, only two ancestral paths would be listed, one per parent (see ▶). In our view, this limited indented list of ancestors in which ancestors with multiple parents are indicated with a (*) will suffice for most users interested in the concept Ectoderm. Those who need more information will, for example, be able to click on the starred parent Trilaminar Embryonic Disc and find that its other parent is Gastrulla, which was missing in the two ancestral paths of ▶. Such a compact display of ancestors will be more effective for users. It will still enable users to obtain further information in a way which directly points to the missing information, e.g., finding that Gastrulla is a grandparent of Ectoderm, while currently the details are buried in the repetitive lists of ancestors. This example also demonstrates the power of the Semantic Navigator as a graphical interface, capturing the hierarchical environment of a concept.

Figure 6.

Indented ancestral paths with * indicating multiple parents.

Concerning goals for the future of the UMLS, auditing was the most important task, followed by design of a derived terminology. Interestingly, expansion of coverage, where most of a putative budget is spent by NLM, is just third. Those results suggest that NLM should reconsider the priorities concerning the UMLS project.

Limitations

The study’s main limitation is the small number of respondents. From the 600 members of the mailing list, the number of the respondents was limited to approximately 12%. The low percentage may indicate unwillingness or lack of time for filling in a questionnaire estimated to require 25–30 minutes. For comparison, during the first 11 months of 2004, only 128 (about 21%) members, excluding NLM staff, were involved in the discussions transacted by e-mail.

The low response rate may have followed from the method used to disseminate the questionnaire. Distribution mechanism was potentially biased, because the mailing list included 600 members, while many more UMLS users were not listed on the mailing list and didn’t receive the questionnaire. Representativeness of the members of the mailing list, e.g., according to various demographic and employment characteristics may have been biased by the small response rate. However, the mailing list is the major channel the NLM uses to contact the UMLS users. For example, new UMLS releases and problems with the UMLS server were regularly and solely announced via the UMLS user list.‡ Thus, this UMLS mailing list was a natural and effective way to recruit UMLS users for our study, especially, since the study was neither initiated nor supported by NLM, to assure its independence.

To get a perspective regarding the response rate obtained in our study, we looked for literature regarding e-mail survey response rates. A classic paper by Kim Sheehan 33 studied dependency of the response rate on five factors. The factors relevant to our study are: the year in which the study was undertaken, the number of questions, and the number of follow-up contacts. Sheehan’s study reviews 31 surveys conducted during 1986–2000, 25 of which were conducted during 1995–2000. It shows a clear trend of decline, in response rate, over time. Sheehan attributes this decline to the decrease in novelty of e-mail surveys with the spread of Internet use, the increase in solicitation e-mail in general, and over surveying in particular. The author predicts that the declining trend will continue. The review reports 46%, 31%, and 24% responses rate during the periods, 1995/6, 1998/9, and 2000. The question is what decline can be expected for 2004 when our study was conducted.

An approximation by linear regression of the 1995–2000 results of Sheehan 2001 33 suggests 10% for 2004. This estimate seems to be supported by recent publications. For example, in Norman and Russell 2006, 34 it is reported that only 9% of the original study sample responded. In a commercial marketing Web site of Beeliner Survey 2006, 35 an average response rate for electronic surveys is reported as 10%∼20%. Our study response rate of 12% fits within these results.

Sheehan 33 found the number of questions to be the second strongest predictor for the response rate. In our study there were many questions (Min et al., 2006) 26 and furthermore, the questions in the agenda part involved long explanations (see Appendix II, available as a JAMIA online data supplement at www.jamia.org). It is likely that the length of the questionnaire caused the reduced response rate. However, the authors wanted to receive responses for these complex questions, even at the price of a lower response rate.

Due to the limitation of the number of returned questionnaires, the respondents may not accurately represent the population of the mailing list. A bias may exist in that there may have been disproportional numbers from certain kinds of organizations. For example, there were no respondents from any pharmaceutical companies. Employees at pharmaceutical companies might be working under stricter rules concerning activities such as filling in a voluntary questionnaire during working hours. However, we looked at the e-mail addresses of users who posted e-mails to the UMLS mailing list during 2004. Many of those e-mails were from work addresses. Only one such user had an e-mail address indicating a pharmaceutical company subsidiary (in Europe). This anecdotal information is in line with our finding that UMLS users from the pharmaceutical industry did not respond to our questionnaire. Maybe it indicates a low number of UMLS users from the pharmaceutical industry.

A bias might also exist with regards to the questions about age and education level distribution. This may be due to a typical situation in a laboratory or research group where only the senior people may hold a UMLS license and subscribe to the UMLS mailing list. Other less senior UMLS users in such a group may use the same licenses. It is possible that such users were underrepresented in the study population.

Only a few responses, some of which were irrelevant, were obtained to the free text question about desired improvements in the UMLS interface. Maybe wording the question with “UMLS graphical user interface” would have been clearer.

Conclusions

In the final analysis, the present study confirmed that the UMLS is used to access its source terminologies and to map among them—two intended uses of the UMLS. However, we found that most users accessed just a few popular source terminologies. Users appear to be slow in their adoption of transparent access via the rich release format. Users reported many reasons for UMLS use. The leading categories were Terminology Research, Information Retrieval, Terminology Translation, UMLS Research, and Natural Language Processing. The survey also indicated that auditing the correctness of the UMLS and the design of a UMLS-based terminology are primary concerns of the existing user base. The latter is expected, since three quarters of the users actually use the UMLS as a terminology, even though it is not one. With regards to UMLS interfaces, many users agreed with the suggestion that an indented hierarchy should mark concepts with multiple parents.

Appendix I

Table A1.

Table A1 Age Group

| Age | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| 51∼60 yrs. Old | 21 (31%) |

| 41∼50 yrs. Old | 17 (24%) |

| 31∼40 yrs. Old | 15 (21%) |

| 30 yrs. Old or less | 9 (13%) |

| Above 60 yrs. Old | 4 (6%) |

| Unknown | 3 (4%) |

Table A2.

Table A2 Organization Size

| Size | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| 1,001∼5,000 | 20 (29%) |

| More than 5,000 | 18 (26%) |

| 501∼1,000 | 9 (13%) |

| 11∼50 | 8 (11%) |

| 10 or less | 5 (7%) |

| 51∼100 | 5 (7%) |

| 101∼500 | 3 (4%) |

| No answer | 2 (3%) |

Table A3.

Table A3 The Distribution of User Numbers according to Number of Areas Selected (See ▶)

| # of areas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| # of users | 4 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Footnotes

Carolyn Tilley of NLM UMLS Support provided helpful feedback for an early version of the questionnaire. However, this study was neither initiated nor supported by the NLM to assure its independence.

Dr. George Hripsack of Columbia University provided valuable advice regarding the methodology of the study and the paper.

The Semantic Navigator is available every year only for the first (AA) release of the UMLS and is made available with a delay while later releases of the UMLS are already available. 29 At the time when we sent out the survey, only versions of the Semantic Navigator from 1998-2003 were available.

As of August 2005, the NLM maintains two separate UMLS mailing lists, one for official announcements 32 and the other for announcements and discussions. When we conducted our study, there was just one unified list.

References

- 1.Bodenreider O. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology Nucleic Acids Res. 2004:D267-D270(Database issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Humphreys B, Lindberg DAB, Schoolman HM, Barnett GO. The Unified Medical Language System: An informatics research collaboration JAMIA 1998;5:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg DAB, Humphreys BL, McCray AT. The Unified Medical Language System Meth Inform Med 1993;32:281-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UMLS User Mailing List. Available at: umls-users@umlsinfo.nlm.nih.gov (it was changed to UMLSUSERS-L@list.nih.gov on September 1, 2005).

- 5.Schuyler PL, Hole WT, Tuttle MS, Sherertz DD. The UMLS Metathesaurus: representing different views of biomedical concepts Bull Med Libr Assoc 1993;81:217-222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuttle MS, Sherertz DD, Olson NE, Erlbaum MS, Sperzel WD, Fuller LF, et al. Using META-1, the first version of the UMLS Metathesaurus. In: Proceedings of the 14th Annual SCAMC, 1990;131–5.

- 7.McCray AT. Representing biomedical knowledge in the UMLS semantic networkIn: Broering NC, editor. High-performance Medical Libraries: Advances in Information Management for the Virtual Era. Westport, CT: Mekler; 1993.

- 8.UMLS Home Page. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/ Accessed July 7, 2006.

- 9.Noy NF, Carole D, Hafner CD. The State of the Art in Ontology Design: A Survey and Comparative Review AI Magazine Fall 1997;18:53-74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuinness D. Ontologies Come of AgeIn: Fensel D, Hendler J, Lieberman H, Wahlster W, editors. Spinning the Semantic Web: Bringing the World Wide Web to Its Full Potential. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002.

- 11. Making the conceptual connections: The UMLS after a decade of research and developmentMcCray AT and Miller RA (eds.) J Am Med Inform Assoc 1998;5:129-130[Special Issue]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health. PubMed. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?DB=pubmed. Accessed January 19, 2007.

- 13. Research on structural issues of the UMLS J Biomed Inform 2003;36:409-413[Special issue]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollis KF. The Unified Medical Language System from the National Library of Medicine: A review of practical uses for a biomedical information access system. Available at: http://leep.lis.uiuc.edu/publish/kfultz/451LE/UMLSproject.htm. Accessed February 27, 2005.

- 15.White Paper: UMLS Metathesaurus Rich Release Format. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/white_paper.html. Accessed July 7, 2006.

- 16.Hole WT, Carlsen BA, Tuttle MS, Srinivasan S, Lipow SS, Olson NE, Sherertz DD, Humphreys BL. Achieving “source transparency” in the UMLS Metathesaurus Medinfo 2004;11(Pt 1):371-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perl Y, Geller J. Guest Editor’s Introduction to the Special Issue: Research on Structural Issues of the UMLS—Past, Present, Future J Biomed Inform 2003;36:409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cimino JJ. Battling Scylla and Charybdis. The search for redundancy and ambiguity in the 2001 UMLS Metathesaurus. In: S Sakken, editor. Proc 2001 AMIA Annual Symposium. Washington, DC; 2001;120–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bodenreider O. Circular hierarchical relationships in the UMLS: etiology, diagnosis, treatment, complications and prevention. In: Bakken S, editor. Proc 2001 AMIA Annual Symposium. Washington, DC; 2001:57–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cimino JJ, Min H, Perl Y. Consistency across the hierarchies of the UMLS Semantic Network and Metathesaurus J Biomed Inform 2003;36:450-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu H, Perl Y, Geller J, Halper M, Liu L, Cimino JJ. Representing the UMLS as an OODB: modeling issues and advantages JAMIA 2000;7:66-80Selected for repint in R. Haux, C. Kulikowski, eds.: Yearbook of Medical Informatics, International Medical Informatics Association, Rotterdam, 2001:271–85.10641964 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu H, Perl Y, Elhanan G, Min H, Zhang L, Peng Y. Auditing concept categorizations in the UMLS Art Intell Med 2004;31:29-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng Y, Halper M, Perl Y, Geller J. Auditing the UMLS for redundant classification: In: Proc. 2002 AMIA Annual Symposium. San Antonio, TX; 2002:612–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.McCray AT, Nelson SJ. The representation of meaning in the UMLS Methods Inf Med 1995;34:193-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geller J, Gu H, Perl Y, Halper M. Semantic refinement and error correction in large terminological knowledge bases Data & Knowledge Engineering 2003;45:1-32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min H, Perl Y, Chen Y, Hapler M, Geller J, Wang Y. Auditing as part of the terminology design life cycle JAMIA 2006;13:676-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang D, Stolte C, Bosch R. Design Choices when Architecting Visualizations Inform Visualiz 2004;5:65-79. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCray AT, Burgun A, Bodenreider O. Aggregating UMLS semantic types for reducing conceptual complexity. In: Proceedings of Medinfo 2001, London, UK, September 2001;171–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Bodenreider O. Personal communication.

- 30.Lomax J, McCray AT. Mapping the Gene Ontology into the Unified Medical Language System Comp Func Genom 2004;5:345-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium GO. Creating the Gene Ontology resource: Design and implementation Genome Res 2001;11:1424-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UMLS Announcements Mailing List. umls-announces-l@list.nih.gov .

- 33.Sheehan K. E-mail Survey Response Rates. Rev J Comp Med Comm [serial online]. 2001;6(2). Available at: http://jcmc.indian.edu/vol6/issue2/sheehan.html. Accessed December 6, 2006.

- 34.Norman AT, Russell CA. The pass-along effect: Investigating word-of-mouth effects on online survey procedures J Comp-Med Comm 2006;11:1085-1103[serial online]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beeliner Survey Software. Available at: http://www.beelinersurveys.com/newsroom/mediafaqs.html. Accessed October 5, 2006.