Abstract

Although cost-effectiveness is becoming the foremost evaluative criterion within health service management of spine surgery, scientific knowledge about cost-patterns and cost-effectiveness is limited. The aims of this study were (1) to establish an activity-based method for costing at the patient-level, (2) to investigate the correlation between costs and effects, (3) to investigate the influence of selected patient characteristics on cost-effectiveness and, (4) to investigate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of (a) posterior instrumentation and (b) intervertebral anterior support in lumbar spinal fusion. We hypothesized a positive correlation between costs and effects, that determinants of effects would also determine cost-effectiveness, and that posterolateral instrumentation and anterior intervertebral support are cost-effective adjuncts in posterolateral lumbar fusion. A cohort of 136 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain, who were surgically treated from January 2001 through January 2003, was followed until 2 years postoperatively. Operations took place at University Hospital of Aarhus and all patients had either (1) non-instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion, (2) instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion, or (3) instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion + anterior intervertebral support. Analysis of costs was performed at the patient-level, from an administrator’s perspective, by means of Activity-Based-Costing. Clinical effects were measured by means of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire and the Low Back Pain Rating Scale at baseline and 2 years postoperatively. Regression models were used to reveal determinants for costs and effects. Costs and effects were analyzed as a net-benefit measure to reveal determinants for cost-effectiveness, and finally, adjusted analysis (for non-random allocation of patients) was performed in order to reveal the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of (a) posterior instrumentation and (b) anterior support. The costs of non-instrumented posterolateral spinal fusion were estimated at DKK 88,285(95% CI 81,369;95,546), instrumented posterolateral spinal fusion at DKK 94,396(95% CI 89,865;99,574) and instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion + anterior intervertebral support at DKK 120,759(95% CI 111,981;133,738). The net-benefit of the regimens was significantly affected by smoking and functional disability in psychosocial life areas. Multi-level fusion and surgical technique significantly affected the net-benefit as well. Surprisingly, no correlation was found between treatment costs and treatment effects. Incremental analysis suggested that the probability of posterior instrumentation being cost-effective was limited, whereas the probability of anterior intervertebral support being cost-effective escalates as willingness-to-pay per effect unit increases. This study reveals useful and hitherto unknown information both about cost-patterns at the patient-level and determinants of cost-effectiveness. The overall conclusion of the present investigation is a recommendation to focus further on determinants of cost-effectiveness. For example, patient characteristics that are modifiable at a relatively low expense may have greater influence on cost-effectiveness than the surgical technique itself—at least from an administrator’s perspective.

Keywords: Economic evaluation, Cost-effectiveness, Lumbar spinal fusion, Methods, Low back pain

Introduction

Cost-effectiveness is becoming the foremost evaluative criterion for health service management in the treatment of chronic low back pain. In lumbar spinal fusion, the evidence for the effect of one surgical technique over another is not convincing [3, 4, 8, 10, 18, 23] and hence, from a health services management’s point of view, surgical techniques seem substitutable and the potential for prioritizing value for money is obvious.

Stochastic cost-effectiveness evaluations, the term often used for evaluations relating to patient-level data, rely upon methodology which is traditional to biomedical research [2, 19]. The term cost-effectiveness relates to allocative efficiency, which is a question about prioritizing value for money within a given budget; a treatment can be either more or less cost-effective, this is by definition, given its comparison to an alternative treatment. When this paper, to a wide extent, refers to costs and effects—in contrast to cost-effectiveness—it refers to a descriptive analysis of those parameters as separate parameters. In lumbar spinal fusion—where clinical differences among techniques are found to approach insignificance—the ratio statistics can be problematic because the estimate of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio then covers more than one quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane. This may be resolved by reporting the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio as an acceptability curve, which is a cumulative distribution function of the probability for cost-effectiveness within a given range of decision-makers’ willingness-to-pay [7, 16]. However, by aggregating both costs and effects into a group estimate, important subgroups may be overlooked. It might be that certain patient characteristics have greater influence on cost-effectiveness than the surgical technique itself. To allow for such analysis, cost data at the patient-level are necessary but, to our knowledge,such data have not been reported in the literature comparing different techniques for lumbar spinal fusion. Furthermore, in order to identify subgroups with significantly different cost-effectiveness ratios, the cost-effectiveness ratio needs to be transformed into a linear function amenable to regression analysis. Such an approach—the net-benefit framework—has recently been suggested by Stinnett and Mullahy, among others [11, 21].

Before performing sophisticated analysis with patient-level data, it may be worth investigating the co-variation between treatment costs and treatment effects—a logical but hereto not established relationship in lumbar spinal fusion. To the best of our knowledge, no stochastic analysis has investigated co-variation between costs and effects.

The first randomized cost-effectiveness evaluation in lumbar spinal fusion was recently reported by Fritzell et al. [9]. The authors concluded that the cost-effectiveness of lumbar spinal fusion depends on decision-makers’ willingness-to-pay. This conclusion reflects another problem in cost-effectiveness evaluation: at what level do we encounter the maximum level of decision-makers’ willingness-to-pay? This discussion is complicated by different choices of outcome parameters and instruments for their measurements, different study populations, and diversified study settings among others. Evidently, willingness-to-pay is a controversial issue and it may be difficult for politicians to navigate in a field with multiple combinations of health scientific and disease-specific parameters.

The aims of this study were (1) to establish an activity-based method for costing at the patient-level, (2) to investigate the correlation between costs and effects, (3) to investigate the influence of selected patient characteristics to cost-effectiveness and, (4) to investigate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of (a) posterior instrumentation and (b) anterior intervertebral support in lumbar spinal fusion.

Materials and methods

Study design and material

A cohort of consecutive patients, who had lumbar spinal fusion at University Hospital of Aarhus from January 2001 through January 2003, was followed until 2 years postoperatively. The patients were recruited from a clinical database of all lumbar spinal fusions conducted in the Spine Section. The extraction from the database was made by means of the eligibility criteria, which are specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the investigation of costs and effects in a cohort of consecutive patients who underwent lumbar spinal fusion

| 1. Severe, chronic low back- and leg pain due to localized segmental instability caused by |

| (a) Isthmic spondylolisthesis (grade I–II) or |

| (b) Primary disc degeneration (no previous surgery) or |

| (c) Secondary disc degeneration (due to earlier surgery or fractures) |

| 2. Level of instability within range of S1–L3 |

| 3. Age within range of 20–65 |

| 4. Index surgery performed from 01.01.2001 to 31.12.2002 |

Activity-Based-Costing

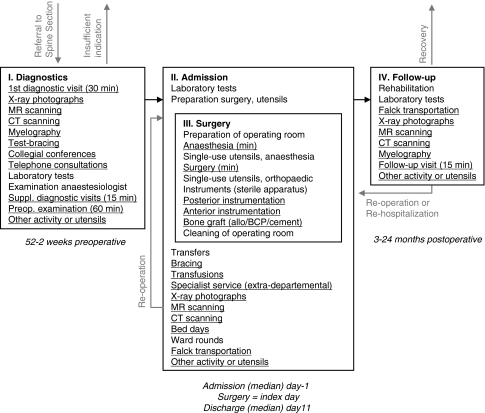

Total hospital costs (DKK) that incurred from the initial visit in the Spine Section (following referral) till the closing visit for the 2-year postoperative follow-up were measured from a hospital perspective. Costing was performed at the patient level by means of Activity-Based-Costing; for each patient activity and related consumption of utensils were measured and valuated. Figure 1 outlines the variables that were measured. To establish the algorithm presented in Figure 1 concurrent observations were conducted in random, similar patients (with respect to inclusion criteria) before starting present study. Several iterations were run until the algorithm succeeded in being able to recognize significant activity. Findings were continuously discussed (validated) with all possible personnel and, in particular, the spine surgeons. Having identified the significant activity and it’s related consumption of utensils, this algorithm was applied the consecutive patients included in present study; activities that are variable among patients were measured individually per patient by reviewing the patient’s medical record (general sequence history of all activity, description of radiological examinations, description of laboratory tests, list of implants/allograft/transfusions, anaesthetic sequence monitoring, postoperative monitoring, registration of complications and postoperative orthosis among others). Activities that are non-variable among patients were included into a base of fixed activity. Consumption of services from supportive departments, overheads, depreciation and capital costs were included in a bed day component; nursing, care and physiotherapy were included in the bed day component as well. Having measured all activities and the related consumption of utensils, valuation was conducted by a bottom-up approach. Table 2 lists unit’s costs and reflects an aggregated level of single item’s costs that was practically measurable in relation to activity; although it is possible to detail even further with respect to valuation (single item’s costs are available in more detail than listed) activities and consumption of utensils were not measurable in such a degree of detail, for example, we measured human recourses costs of a minute of surgery as a (median) total of personnel being present in the operating room during an operation. Single item costs were obtained from the hospital’s purchasing agents, medical suppliers or, in the case of intra-hospital and non-marketed services, cost estimates were provided by the respective departments supplying these services. All costs include value-added tax (VAT) and are reported in 2004 prices (DKK). The costs of human resources were estimated in terms of gross annual salaries in individual professional groupings. Costs are comprised of base salary, addition for extended range of functions or qualifications, contribution for holiday pay, contribution for AER (employers’ refund for trainees) and contribution for ATP (wage earners’ supplementary pension). In calculating the costs of a chief spine surgeon or a chief anaesthesiologist, the point of reference was a surgeon employed for elective surgery. The base salary is established via collective agreements between the medical societies and the employer. To acknowledge non-productive time, load-factors were estimated. Non-productive time denotes time that an employee cannot account for (transportation, breaks, administrative tasks etc.). The load-factor was empirically estimated at 1.28 for the spine surgeons and extrapolated to other medical doctors. Personnel other than doctors were assigned an estimated load-factor of 1.25. The estimate of a bed day cost was deduced from the hospital’s accounts. The economic focus of this study was blinded to patients and surgeons.

Fig. 1.

Activities and utensils measured in Activity-Based-Costing analysis of lumbar spinal fusion. A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 consecutive patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005

Table 2.

Selected unit’s costs; results of Activity-Based-Costing in a follow up study of 136 consecutive patients. All costs are in 2004-prices (DKK)

| Regimen | Activity or utensil | Cost (DKK) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics | Visits to outpatient clinic | |

| 15 min (diagnostic investigation) | 213 | |

| 30 min (1st visit) | 426 | |

| 60 min (final preoperative examination) | 852 | |

| Telephone consultations | 184 | |

| Collegial conferences | 208 | |

| Radiology | ||

| X-ray | 702 | |

| MRI | 1,404 | |

| CT | 936 | |

| Myelography | 1,404 | |

| Test bracing | 454 | |

| Other activities or utensils | ||

| Interpreter-assisted visit | 362 | |

| Admission for radiology (1 bed day at hospital’s hotel) | 1,659 | |

| Scintigraphy | 1,904 | |

| Activity non-variable among patients | ||

| Blood bank consensus | 208 | |

| Standard laboratory tests (blood samples + EKG) | 400 | |

| Examination anesthesiologist | 346 | |

| Admission and surgery | Bed day | 3,818 |

| Ward round (per patient) | 184 | |

| Anesthesia, per minute | 14 | |

| Surgery, per minute (incl. anesthesia) | 38 | |

| Posterior instrumentation (aggregated)a | 17,131 | |

| Anterior instrumentation (aggregated)a | 9,971 | |

| Bone graft | 3,250 | |

| Blood transfusion | 696 | |

| Postoperative radiology | ||

| X-ray | 806 | |

| MRI | 1,508 | |

| CT | 1,040 | |

| Brace for mobilization | 10,700 | |

| Transportation by dischargeb | 1,423 | |

| Other activities or utensils | ||

| Monitoring at intensive care (additional to bed day cost) | 4,435 | |

| Specialist investigations (other than dept. doctors) | 816 | |

| Ultra sound | 572 | |

| Interpreter-assistance | 362 | |

| Scintigraphy (various) | 1,904 | |

| Activity non-variable among patients | ||

| Utensils for anesthesia | 300 | |

| Catherization before operation | 218 | |

| Service assistants at call | 132 | |

| Transfer by hospital porter | 104 | |

| Surgeon present for bedding to OP table | 298 | |

| Preparation of operating room | 471 | |

| Utensils for surgery | 431 | |

| Cleaning of operating room | 497 | |

| Standard laboratory tests | 300 | |

| Follow-up | Transportation to 1st follow-up visitb | 1,423 |

| Visits to outpatient clinic | 213 | |

| Collegial conferences | 208 | |

| Radiology | ||

| X-ray | 702 | |

| MRI | 1,404 | |

| CT | 936 | |

| Myelography | 1,404 | |

| Other activities or utensils | ||

| Re-hospitalization (bed day) | 2,957 | |

| Specialist investigations (other than dept. doctors) | 816 | |

| Flexible brace | 4,200 | |

| Ultra sound | 572 | |

| Interpreter-assistance | 372 | |

| Activity non-variable among patients | ||

| Standard laboratory tests | 300 | |

Note: re-operations are measured and valuated similar to index surgery

aMarket prices of specific utensils were adapted; presented here, is a median cost

bCosts are depending on distance to hospital; presented here, is a median one-way cost

Effect measures

The primary measure of effects was change in functional disability from preoperatively through 2 years postoperatively, which was assessed by means of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire [15]. It should be emphasized that ‘effects’ refer to change in functional disability in the course of time and not solely to clinical-, treatment- or intervention effects. The Dallas Pain Questionnaire covers four areas of functional disability: in daily activities, in work/leisure activities, disability due to anxiety/depression, and in social life. As a secondary effect measure, change in degree of leg and back pain was measured by means of the Low Back Pain Rating Scale [17]. Global satisfaction was assessed by posing the question of ‘would you undergo the operation again, now that you know the outcome?’ at 2 years postoperative.

Statistical analysis

Treatment costs were reported in terms of means and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals drawn from bootstrapping. Bootstrapping refers to a non-parametric technique for estimating the precision of estimates; by means of multiple replications of drawings from the sample (assuming that the sample is representative of the population), the random variation is suggested [5]. The number of replications needed for bootstrapping was calculated by means of Andrews and Buchinsky’s method [1]. Paired observations of costs and effects were scattered and subjected to the bivariate correlation test of Kendall’s tau-b. Comparisons of surgical groups were conducted by means of Kruskal–Wallis’ test and possible determinants for cost-effectiveness were investigated by means of linear multiple regressions (ordinary least square) with bootstrapped confidence intervals for the coefficients. Prior to analysis, determinants were structured in correlation matrices (by pair wise correlations) and scatter diagrams to evaluate whether or not interaction of determinants required control; no controlling actions were found necessary. Model provisions were investigated by studying (1) residuals versus fitted values, (2) residuals versus possible determinants and (3) the normality of residuals. Prior to regression analysis, cost–effect pairs were transformed into net-monetary-benefits (NMB, hereafter net-benefit); NMBλ = λ × μEi − μCi, where λ is the value of a hypothetical willingness-to-pay for one effect unit; μ is mean incremental effect, respectively mean incremental costs [11, 21]. Imputation was conducted to replace missing values in single items of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. Syntax was programmed, which calculated the horizontal (intra-patient) mean of the non-missing values individually in each factor of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. This reasoning is in agreement with the theoretical model behind the Dallas Pain Questionnaire, which characterizes observations in these four clusters [15]. To allow for analysis of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, the study population was re-modelled into clinically relevant comparisons: (1) non-instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion (hereafter non-instrumented fusion) versus instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion (hereafter instrumented fusion), and (2) instrumented versus instrumented posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion + anterior intervertebral support (hereafter circumferential fusion). Adjustments for non-random allocation of patients were carried out by means of linear regression as described by Hoch et al. [11]. Acceptability curves were established by means of a non-parametric method as described by Löthgren and Zethraeus [16]. Analysis was performed using Intercooled STATA version 8.2 (Stata Corp.). Two-tailed tests and a 95% level of significance were employed. The present study is conducted with the approval of the Danish National Board of Health and The Danish Data Protection Agency.

Results

Baseline and follow-up

The study population comprised 136 patients and the overall follow-up was 83% in relation to clinical outcome and 100% in relation to costs. Comparative tests of respondents and non-respondents with regard to patient characteristics and costs revealed no significant differences. The included patients were operated on by one of three surgical techniques: 17 patients had non-instrumented fusion, 74 patients had instrumented fusion, and 45 patients had circumferential fusion. Baseline characteristics distributed over surgical techniques are presented in Table 3. Apart from the fact that the patients who underwent circumferential fusion were significantly younger (P < 0.001) in comparison to other groups, no significant differences were identified. All groups demonstrated significant clinical improvement from baseline though 2 years postoperative (P < 0.05). Global improvement (patient satisfaction) was indicated by 80–85% of the patients.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics for 136 consecutive patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion. Spine Section of Aarhus, 2001–2002. Values are frequencies (%) unless stated otherwise

| Baseline characteristics | Surgical technique | All patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-instrumented fusion (n = 17) | Instrumented fusion (n = 74) | Circumferential fusion (n = 45) | ||

| Age, median (min–max) | 53 (26–64) | 51 (26–63) | 40 (21–53) | 47 (21–64)* |

| Females | 10 (59) | 43 (58) | 22 (49) | 75 (55) |

| Smokers (n = 116) | 11 (65) | 31 (52) | 20 (51) | 62 (53) |

| Not educated | 8 (47) | 31 (42) | 12 (27) | 51 (38) |

| Not working (n = 134) | 12 (75) | 50 (68) | 26 (59) | 88 (66) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Spondylolisthesis | 4(24) | 27(36) | 22(49) | 53(39) |

| Primary degeneration | 6(35) | 26(35) | 7(16) | 39(29) |

| Secondary degeneration | 7(41) | 21(28) | 16(36) | 44(32) |

| Disability daily activities (n = 121) median (min–max) | 66 (3–93) | 63 (80–102) | 69 (15–102) | 66 (0–102) |

| Disability work/leisure (n = 119) median (min–max) | 65 (10–100) | 70 (0–100) | 75 (85–100) | 70 (0–100) |

| Disability anxiety/depression (n = 119) median (min–max) | 25 (0–80) | 50 (0–100) | 55 (0–95) | 45 (0–100) |

| Disability social life (n = 121) median (min–max) | 35 (5–85) | 35 (0–100) | 35 (0–95) | 35 (0–100) |

*Significantly different among surgical groups at P < 0.001 by means of Kruskal–Wallis test

Costs of the regimen

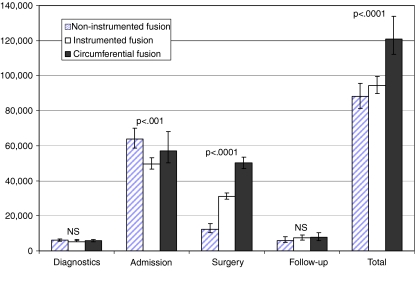

From the patient’s referral to the Spine Section until the 2-year postoperative clinical follow-up, the hospital costs totaled approximately 100,000 DKK. Not surprisingly, these costs differed among surgical techniques (P < 0.0001). Non-instrumented fusion cost DKK 88,285(81,369;95,546), instrumented fusion cost DKK 94,396(89,865;99,574) and circumferential fusion cost DKK 120,759(111,981;133,738). Treatment costs distributed among the main activity categories are illustrated in Fig. 2. Surgical complexity was not reflected in admission costs as the least invasive technique (non-instrumented fusion) generated the most costly admissions (P < 0.0001). This was partly due to postoperative orthosis being a part of the standard-regimen for non-instrumented fusion. With regard to other components of admission costs: bed days, complications or transportation to home upon discharge, the groups did not differ significantly. Not surprisingly, the costs of the perioperative regimen were proportional to the invasiveness of the procedure. Looking into components of the perioperative costs, a highly significant difference in the cost of surgical minutes (P < 0.0001) and implants (p < 0.0001) appeared. Neither the costs of anesthesia nor re-operations differed among groups.

Fig. 2.

Treatment costs (DKK) in lumbar spinal fusion estimated by Activity-Based-Costing analysis in 136 consecutive patients. A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 consecutive patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005. Note: Error bars are 95% bias-corrected, bootstrapped confidence intervals from 7,319 replications and P-values are results of Kruskal–Wallis test

The relationship between costs and effects

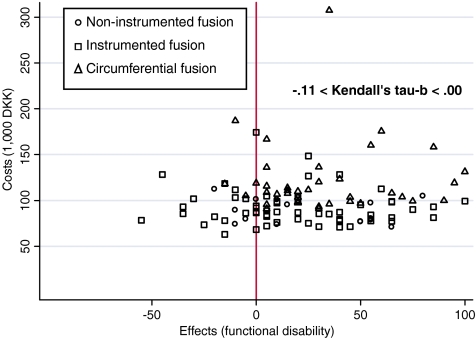

Surprisingly, very poor correlations were found between treatment costs and each of the four factors of the effect measure (−0.26 < Kendal’s tau-b ≤ 0.14). This also applied for sub-groupings of costs (−0.24 < Kendal’s tau-b ≤ 0.16) and in particular, costs affiliated with admission (in isolation) and costs of surgery (in isolation). Figure 3 shows paired observations of total hospital costs (DKK) and effects (reduction in functional disability related to work/leisure activities).

Fig. 3.

Treatment costs (DKK) and effects over surgical techniques in lumbar spinal fusion. A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 consecutive patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005. Note: Effects are change in status of functional disability in relation to work/leisure activities (points of in a 0–100 scale) measured by means of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire

Determinants of the net-benefit

Table 4 shows significant determinants for cost-effectiveness for selected values of decision-makers’ hypothetical willingness-to-pay. That is, should decision makers be willing to pay at least DKK 8,000 for a one-point reduction in functional disability, the average scenario is that smokers seem to reduce the net-benefit by approximately DKK 100,000 (at least in terms of the psychosocial factors) in comparison to non-smokers. Overall, and for increasing values of willingness-to-pay, net-benefit was significantly influenced as follows: (1) the fact of being a smoker reduces the net-benefit in psychosocial factors (column A and S), (2) the fact of being functionally disabled due to anxiety/depression surprisingly increases the net-benefit (column W and A), (3) the fact of being functionally disabled in social life showed bi-directional tendencies, and (4) having surgery at multiple levels—not surprisingly—decreases the net-benefit again, mainly with respect to psychosocial effect measures. The influence of surgical techniques was insignificant for values of willingness-to-pay above DKK 2,000. In other words, the more that decision makers are willing to pay per effect unit, the less important is the choice of surgical technique in relation to average net-benefit (or cost-effectiveness).

Table 4.

Adjusted net-monetary-benefit (NMBλ) for different values of hypothetical values of willingness-to-pay (λ/DKK) for a 1-point reduction in functional disability

| Determinants | NMB2,000 (SE) | NMB4,000 (SE) | NMB8,000 (SE) | NMB16,000 (SE) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | W | A | S | D | W | A | S | D | W | A | S | D | W | A | S | |

| Smoker | −45,706 (23,052) |

−100,258 (46,285) |

−96,743 (43,950) |

−209,360 (90,387) |

−202,299 (86,421) |

|||||||||||

| Anxiety/depressiona | 642 (288) | 941 (302) | 1,989 (242) | 1,001 (474) | 1,602 (529) | 3,704 (440) | 2,925 (1,040) | 7,133 (891) | 5,571 (2,068) | 13,992 (1,802) | ||||||

| Social lifea | −884 (267) | 998 (257) | −1,379 (512) | 2,386 (463) | −2,369 (1,030) | 5,161 (930) | −4,348 (2,082) | 10,712 (1,863) | ||||||||

| Multiple levels fused |

−36,101 (12,427) |

−39,037 (12,621) |

−50,456 (23,397) |

−56,315 (23,218) |

−90,872 (45,741) |

|||||||||||

| Circumferential fusionb | −45,004 (20,634) |

−48,731 (19,572) |

||||||||||||||

| n | 109 | 108 | 108 | 109 | 109 | 108 | 108 | 109 | 109 | 108 | 108 | 109 | 109 | 108 | 108 | 109 |

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.37 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.29 |

| RMSE (1,000) | 60 | 68 | 61 | 58 | 110 | 130 | 120 | 110 | 220 | 250 | 230 | 210 | 430 | 500 | 460 | 400 |

A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 consecutive patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005

Measured by means of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire (functional disability D = in daily activities, W = in work/leisure activities, A = due to anxiety/depression and S = in social life)

Note: only significant determinants (P < 0.05) are displayed from bootstrap regression (9,199 replications) with independents: age, gender, smoking, educational status, occupational status, functional disability due to anxiety/depression, functional disability in social life, diagnostic group, number of fused levels and surgical technique

aPreoperative score of functional disability in respective factors

bIn comparison to instrumented posteolateral fusion

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

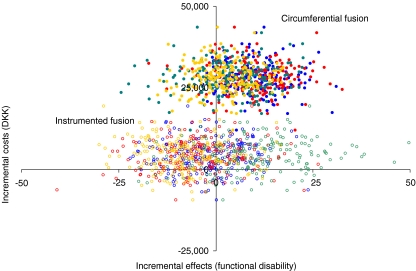

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio is usually defined as incremental costs divided by incremental effects. In the present study, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios denote the additional costs for a one-point reduction in functional disability either when the surgical technique is (a) instrumented fusion in comparison to non-instrumented fusion, or (b) circumferential fusion in comparison to instrumented fusion. The incremental costs of instrumented fusion (when adjusted for age, gender, smoking, educational status, occupational status, functional disability due to anxiety/depression, functional disability in social life, diagnostic group and number of fused levels) are estimated at DKK 4,684(−4,779;14,545) which is obviously not significant. The incremental costs of circumferential fusion (adjusted) are estimated at DKK 28,382(18,884;38,208), which is obviously highly significant. The incremental effects of both instrumented fusion and circumferential fusion were not significant. Figure 4 illustrates the cost-effectiveness plane for 800 bootstrap replicates (200 of each factor in the Dallas Pain Questionnaire) of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for (a) instrumented fusion and (b) circumferential fusion. Overall, the replications of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for instrumented fusion suggest that this technique is equally effective and slightly more costly compared to non-instrumented fusion (majority of circles spreading around the y-axis with approximately two thirds of circles in the Northern part of the plane and one third in the Southern part). The replications of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of circumferential fusion suggest that this technique is slightly more effective and significantly more costly than instrumented fusion (approximately two thirds of the dots lie in the Northeast quadrant of the plane and one third in the Northwest quadrant).

Fig. 4.

Bootstrap replications of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of a instrumented posteolateral fusion and b circumferential fusion. A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 consecutive patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005. Note: If the incremental ratio is significantly located in the Northwest quadrant (more costly and less effective) the intervention at hand is definitely not cost-effective. If the incremental ratio is significantly located in the Southeast quadrant (more effective and less costly) the intervention at hand is definitely cost-effective. If estimates are located in the Northeast (more effective but more costly as well) or the Southwest quadrants (less effective but less costly as well) the intervention at hand is cost-effective only if decision-maker’s willingness-to-pay are > the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

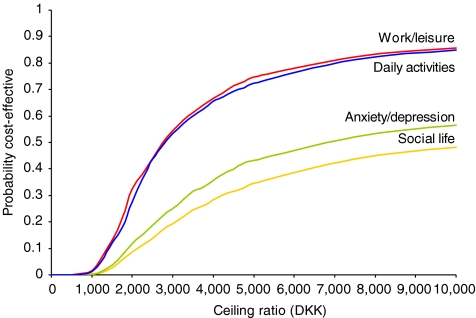

Figure 5 illustrates the acceptability curve for circumferential fusion (in comparison to instrumented fusion). The principle of an acceptability curve is that for different hypothetical values of willingness-to-pay for an effect unit, the probability of the intervention being cost-effective can be read from the y-axis. Usually, when a new intervention is more effective and more costly, the curve will show an increasing probability for increasing values of willingness-to-pay, the curve will cut the y-axis in zero, and it will asymptote to one. The curves of circumferential fusion show increasing probabilities with increasing values of decision-makers’ willingness-to-pay. The curves cut the y-axis at 0 since no replicates involve cost savings, but the curves do not asymptote to one because some replicates involve negative effects. Negative effects occur in less than 10% of the replicates related to daily activities and work/leisure whereas approximately one third of replicates in psychosocial factors are negative.

Fig. 5.

Acceptability curve for circumferential fusion (in comparison to instrumented posteolateral fusion) over four factors of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. A cohort study with a 2-year follow-up in 136 patients. Aarhus, 2001–2005. Note: For given values of decision-makers maximum willingness-to-pay (the ceiling ratio at the x-axis) the probability of cost-effectiveness (y-axis) can be read from the curves. E.g. should decision-makers be willing to pay up to 8,000 DKK per effect unit (point reduction of functional disability) and decide from the dimensions of work/leisure or daily activities, a probability above 80% for circumferential fusion being cost-effective can be read from the y-axis

Discussion

This study reveals hitherto unknown information both about cost-patterns at the patient-level and determinants for cost-effectiveness. We established a valid and easily applicable method for costing at the patient-level. One advantage of costing at the patient-level is the creation of opportunities for identifying subgroups; by means of a net-benefit approach, subgroups reflecting significantly different ratios of cost-effectiveness can be identified. This approach may very well prove to be useful in other areas of orthopedic research, not necessarily limited to spinal surgery.

The validity of costs may be discussed in the light of other relevant costing systems. A recent Danish study compared different costing systems applied in the treatment of stable angina pectoris and described the expected responses [14]. For short hospitalizations (relative to national means in groups in the case-mix system of Diagnosis-Related-Grouping), the costing systems would relate as follows: estimate of Diagnosis-Related-Grouping > estimate of Activity-Based-Costing analysis > hospital charge. For long hospitalizations, the relationship would be: hospital charge > estimate of Activity-Based-Costing analysis > estimate of Diagnosis-Related-Grouping. This mode of ranking systems can be explained in terms of costs of bed days; if we regard costs as a function of a hospitalization, the estimate of Diagnosis-Related-Grouping will basically be independent of length of stay1; the hospital charge, because it encompasses implicit activity in the cost of a bed day, will often be proportional to length of stay; and finally, the estimate of Activity-Based-Costing analysis acknowledges variations in activity density at different stages of a hospitalization. The mean length of hospitalization in the present study was 3 days above the national mean in non-instrumented fusion whereas in instrumented fusion and circumferential fusion, the mean length of hospitalization was equal to the national mean [22]. Referring to the work of Larsen et Skjoldborg [14], we would expect hospital charge to be > estimate of Activity-Based-Costing analysis > estimate of Diagnosis-Related-Grouping in non-instrumented fusion, whereas in both instrumented fusion and circumferential fusion, we would expect the three estimates to approach each other. This was the exact picture apart from a deviation of hospital charges in instrumented and circumferential fusion. Such deviation is plausible, because hospital charges are not discriminated between chronic low back pain and diagnoses involving deformities (often subject to more complex surgery). We may also compare our incremental costs to those of the recent Swedish cost-effectiveness evaluation in chronic low back pain [9]. Both the Swedish study and our findings estimate the incremental costs of circumferential fusion at approximately DKK 28,000 whereas our estimate of the costs of instrumented fusion is DKK 4,684 and the corresponding Swedish estimate is DKK 52,284. We have not been able to identify the reason for this difference because the Swedish analysis builds on a group-estimate that is not reported in a manner sufficiently detailed to allow comparisons of activities and costs of single components.

The present study is the first to have conducted Activity-Based-Costing analysis in spinal fusion. We broke the production process down into a large number of activities, each of which was measured individually per patient. Although such effort is rewarded by superior accuracy, the weak link of Activity-Based-Costing analysis, applied to hospital activities, is the validity of the bed day cost, because it covers activities that are not directly allocative to the patient-level. It is not practically possible to measure, for example, minutes of postoperative nursing. Evidently, present costs estimates are characterized by superior accuracy in comparison to those provided by analyses taking a broad, societal perspective. In addition to this superior accuracy, it is important to recognize the limitations of present perspective, that is, societal consequences as, for example, production losses are not considered. This material is not intended to influence national health policy decisions but rather, to gain knowledge about the pathogenesis of costs and effects and potentially, form the basis of the design of future randomized trials.

Determinants for cost-effectiveness were revealed by means of the net-benefit approach. The net-benefit in lumbar spinal fusion was found to be significantly affected by smoking and functional disability in psychosocial life areas. Considering such determinants to be modifiable presents us with a potential for improving outcome (in terms of cost-effectiveness) by means of, for example, providing supportive interventions for the patients preoperatively. Another alternative—perhaps debatable with respect to ethics—would be to discuss the selection of candidates on the basis of knowledge about patient-individual cost-effectiveness. In any case, the investigation of determinants becomes central to decision-making in spine surgery as, for example, patient characteristics may have far greater influence on cost-effectiveness than the surgical technique itself. It should be emphasized that the perfect scenario for investigating determinants would have been analysis of determinants for incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (incremental net-benefit rather than average net-benefit). Such analysis is possible as a second step to our analysis as described by, among others, Hoch et al. [11]. In any event, the procedure would be to add treatment-interaction variables to our regression model. The coefficients of such would then be the estimated magnitude of determinants for incremental cost-effectiveness ratio but clearly, such extension would call for a much larger sample size.

We conducted incremental analysis despite a non-random allocation of patients. Using the methodology provided by Hoch et al. [11] we adjusted for a series of relevant patient characteristics to compensate for the non-random allocation of patients. Whether this is an act stretching the scope of the Hoch et al. methodology to the limit is debateable because this methodology was originally launched as a tool against imperfect randomization. Conversely, the consecutive nature of this cohort provides strength with respect to external validity and we feel that this analysis can contribute as a generation of hypotheses. We leave it up to the reader to judge the usefulness and accordingly, we do not draw conclusions to the investigation of the ICER. Our analysis suggested that the probability of instrumented fusion being cost-effective is not convincing because replicates of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio were more or less evenly distributed in all four quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane. The probability of circumferential fusion being cost-effective was estimated to increase with increasing values of willingness-to-pay. If, for example, we regard 0.8 as a reasonable probability for accepting the circumferential fusion as a cost-effective technique in comparison to instrumented fusion, the required WTP is approximately DKK 7,000 per point of functional ability gained (when looking at the two physical factors of the effect measure; the corresponding WTP looking at the psychosocial factors approaches infinite). Indeed, it would have been nice to be able to compare these WTPs with those of, for example, the Fritzell et al. evaluation [9], however, the effect measures are not comparable as Fritzell et al. uses the Oswestry Disability Index [6] and further, they do not report incremental cost–effect ratios among surgical techniques but, only between conservative and surgical treatment. The latest economic evaluation published, the Riviero-Arias et al. study [20] presents their effects as Quality-Adjusted-Life-Years and further, the authors compares conservative treatment to surgery and, do not differentiate among surgical techniques.

The validity of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios fully depends on whether candidates selected for one technique systematically differ from their counterparts selected for other techniques. Although adjusted for important patient characteristics—as discussed above also in relation to the Hoch et al. methodology [11]—our findings are by definition biased from the non-random selection of candidates and for that reason we can not draw conclusion about ICERs but indeed, we recommend this relationship being tested in future trials.

Prior to the design of this study, confronting the issue of statistical power was not straightforward. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have estimated costs at patient-level and the average estimates available (hospital charges) are all publicized in American studies [12, 13]. The power issue was two-sided; for the descriptive analysis (identification of determinants), the question concerns the ability to detect a minimally relevant influence of a determinant, while in the comparative analysis, the question concerns the ability to classify the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio as either cost-effective or not cost-effective. Determinants for cost-effectiveness were identified by means of the net-benefit approach and the scaling of this net-benefit parameter clearly depends on decision makers’ willingness-to-pay and hence, power is dependent on the minimally relevant influence relative to the values of willingness-to-pay. A traditional power calculation is bivariate and would not return the power to detect a true determinant, as variation in data would relate not only to the potential determinant at hand but also to the influence from other patient characteristics. Since the handling of four stochastic variables (C0, C1, E0 and E1) is problematic, traditional power calculations for comparative analysis of cost-effectiveness, are insufficient, but there are newer methodologies that are useful when variation in costs and effects pairs are known [24]. Unfortunately, we had no estimate of the variation in costs and effects pairs prior to this study and hence, we did not calculate any requirements for sample sizes. But we do recognize that the response of such calculations would constitute a sample size much larger than the one chosen for this (pilot scale) study. Employing patient-level estimates and statistics will function as a safeguard against underpowered trials.

The overall conclusion of the present investigation is a recommendation to focus further on determinants for cost-effectiveness for the identification of subgroups. Patient characteristics that are modifiable at a relatively low expense may have greater influence on cost-effectiveness than the surgical technique itself. The true incremental cost-effectiveness of instrumented fusion and respectively circumferential fusion should rely on randomized patient allocation, because the selection of patients for specific surgical techniques is often related to specific comorbidity.

Footnotes

With the exception of hospitalizations exceeding a specific trimming point, which rarely has direct application (26 days in non-instrumented fusion and 23 days in instrumented and circumferential fusion).

References

- 1.Andrews DWK, Buchinsky M. A three-step method for choosing the number of bootstrap repetitions. Econometrica. 2000;68:23–51. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black WC. The CE plane: a graphic representation of cost-effectiveness. Med Decis Making. 1990;10:212–214. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9001000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen FB, Hansen ES, Eiskjaer SP, Hoy K, Helmig P, Neumann P, et al. Circumferential lumbar spinal fusion with Brantigan cage versus posterolateral fusion with titanium Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation: a prospective, randomized clinical study of 146 patients. Spine. 2002;27:2674–2683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen FB, Hansen ES, Laursen M, Thomsen K, Bunger CE. Long-term functional outcome of pedicle screw instrumentation as a support for posterolateral spinal fusion: randomized clinical study with a 5-year follow-up. Spine. 2002;27:1269–1277. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenwick E, O’Brien BJ, Briggs A. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves–facts, fallacies and frequently asked questions. Health Econ. 2004;13:405–415. doi: 10.1002/hec.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischgrund JS, Mackay M, Herkowitz HN, Brower R, Montgomery DM, Kurz LT. Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis, a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine. 1997;22:2807–2812. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Jonsson D, Nordwall A. Cost-effectiveness of lumbar fusion and nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain in the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine. 2004;29:421–434. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000102681.61791.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine. 2002;27:1131–1141. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoch JS, Briggs AH, Willan AR. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: a framework for the marriage of health econometrics and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2002;11:415–430. doi: 10.1002/hec.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Lew RA, Grobler LJ, Weinstein JN, Brick GW, et al. Lumbar laminectomy alone or with instrumented or noninstrumented arthrodesis in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Patient selection, costs, and surgical outcomes. Spine. 1997;22:1123–1131. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuntz KM, Snider RK, Weinstein JN, Pope MH, Katz JN. Cost-effectiveness of fusion with and without instrumentation for patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis. Spine. 2000;25:1132–1139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen J, Skjoldborg US. Comparing systems for costing hospital treatments, the case of stable angina pectoris. Health Policy. 2004;67:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawlis GF, Cuencas R, Selby D, McCoy CE. The development of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. An assessment of the impact of spinal pain on behavior. Spine. 1989;14:511–516. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198905000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lothgren M, Zethraeus N. Definition, interpretation and calculation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Econ. 2000;9:623–630. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200010)9:7<623::AID-HEC539>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manniche C, Asmussen K, Lauritsen B, Vinterberg H, Kreiner S, Jordan A. Low back pain rating scale: validation of a tool for assessment of low back pain. Pain. 1994;57:317–326. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: part 2. Spine. 2000;25:1716–1721. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien BJ, Drummond MF, Labelle RJ, Willan A. In search of power and significance: issues in the design and analysis of stochastic cost-effectiveness studies in health care. Med Care. 1994;32:150–163. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivero-Arias O, Campbell H, Gray A, Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J. Surgical stabilisation of the spine compared with a programme of intensive rehabilitation for the management of patients with chronic low back pain: cost utility analysis based on a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:1239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38441.429618.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:S68–S80. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Danish National Board of Health [Internet database] (2004) The Danish National Board of Health: Landspatientregistret. c2004—[cited 2004 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.sstdk

- 23.Thomsen K, Christensen FB, Eiskjaer SP, Hansen ES, Fruensgaard S, Bunger CE. Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. The effect of pedicle screw instrumentation on functional outcome and fusion rates in posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion, a prospective, randomized clinical study. Spine. 1997;22:2813–2822. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willan AR, O’Brien BJ. Sample size and power issues in estimating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios from clinical trials data. Health Econ. 1999;8:203–211. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199905)8:3<203::AID-HEC413>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]