Abstract

Cys-loop receptor neurotransmitter-gated ion channels are pentameric assemblies of subunits that contain three domains: extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular. The extracellular domain forms the agonist binding site. The transmembrane domain forms the ion channel. The cytoplasmic domain is involved in trafficking, localization, and modulation by cytoplasmic second messenger systems but its role in channel assembly and function is poorly understood and little is known about its structure. The intracellular domain is formed by the large (>100 residues) loop between the α-helical M3 and M4 transmembrane segments. Putative prokaryotic Cys-loop homologues lack a large M3M4 loop. We replaced the complete M3M4 loop (115 amino acids) in the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3A (5-HT3A) subunit with a heptapeptide from the prokaryotic homologue from Gloeobacter violaceus. The macroscopic electrophysiological and pharmacological characteristics of the homomeric 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 receptors were comparable to 5-HT3A wild type. The channels remained cation-selective but the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 single channel conductance was 43.5 pS as compared with the subpicosiemens wild-type conductance. Coexpression of hRIC-3, a protein that modulates expression of 5-HT3 and acetylcholine receptors, significantly attenuated 5-HT–induced currents with wild-type 5-HT3A but not 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 receptors. A similar deletion of the M3M4 loop in the anion-selective GABA-ρ1 receptor yielded functional, GABA-activated, anion-selective channels. These results imply that the M3M4 loop is not essential for receptor assembly and function and suggest that the cytoplasmic domain may fold as an independent module from the transmembrane and extracellular domains.

INTRODUCTION

At fast chemical synapses, ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) transduce chemical signals into electrical signals. Cys-loop receptors, a major superfamily of LGICs, include receptors for acetylcholine (nAChR), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAAR, GABACR), glycine (GlyR), and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine type 3, 5-HT3). These channels are either cation (nAChR, 5-HT3) or anion selective (GABAAR, GABACR, GlyR) (Macdonald and Olsen, 1994; Karlin, 2002; Lester et al., 2004). Cys-loop receptors are pentameric assemblies of homologous subunits arranged pseudosymmetrically around the central ion-conducting pore. All Cys-loop receptor subunits have a similar transmembrane topology and contain three domains: extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular. The extracellular, ligand-binding domain is formed by the ∼200–amino acid N-terminal domain that contains the eponymous 15–amino acid disulfide-linked Cys-loop. The four α-helical transmembrane segments (M1, M2, M3, M4) form the ion channel. They are connected by two short loops, one is intracellular between M1 and M2, and the other extracellular between M2 and M3 and a long cytosolic loop between M3 and M4. The intracellular domain is formed by the long M3M4 loop. The short C terminus is extracellular. The structures of the extracellular and transmembrane domains have been defined by x-ray crystallography and cryoelectron microscopy (Brejc et al., 2001; Unwin, 2005). Their roles in channel assembly and function have been extensively studied. In contrast, the structure of the cytoplasmic domain and its role in channel assembly and function is less well understood. In the 4-Å model based on cryoelectron microscopic images of the AChR the only part of the M3M4 loop that was resolved was an α-helix immediately preceding M4; the so-called membrane-associated (MA) helix (Unwin, 2005). The majority of the M3M4 loop was unresolved and therefore referred to as disordered.

Cys-loop receptor superfamily members were only known from multicellular animals (metazoans) until recent iterative sequence searches identified homologous proteins in prokaryotes (Tasneem et al., 2005). Comparative sequence–structure analysis of the prokaryotic and metazoan LGICs showed that most of the highly conserved positions in the ligand-binding domain stabilize the hydrophobic core of the β-sandwich (Tasneem et al., 2005). Major differences are the lack of the eponymous Cys-loop in bacterial representatives as well as a comparatively short loop of <15 amino acids between M3 and M4 in bacterial LGICs as compared with >100 amino acids in most metazoan subunits. The prokaryotic Cys-loop homologue from Gloeobacter violaceus (Glvi) is a proton-gated cation channel (Bocquet et al., 2007) with a 7–amino acid M3M4 loop.

In metazoan Cys-loop subunits the long hydrophilic M3M4 loop is the least conserved region in terms of length and sequence. The M3M4 loop has been implicated in interactions with proteins involved in clustering, sorting, targeting, trafficking, membrane insertion, and interactions with functional partners (P2X receptors) (Williams et al., 1998; Temburni et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). It also plays a role in the regulation of ion flow through the channel and channel kinetics (Kelley et al., 2003; Hales et al., 2006).

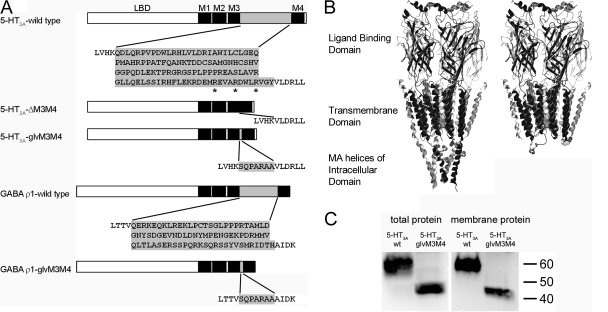

We hypothesized that the entire intracellular domain represented by the large M3M4 loop in metazoan subunits is not necessary for Cys-loop receptor channel function. To investigate this we truncated the M3M4 loop in 5-HT3A and GABA ρ1 subunits, which assemble as homopentamers. We replaced all amino acids between the M3 and M4 segments, 115 amino acids in 5-HT3A and 82 in GABA ρ1, with the putative 7–amino acid M3M4 loop from Glvi, to obtain 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and GABAρ1-glvM3M4 (Fig. 1 A). We found that both truncated receptors expressed functional channels similar to wild type but interactions of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 with the human resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase type 3 protein (hRIC-3) were significantly attenuated. Our results demonstrate that the M3M4 loop is not essential for assembly or function of cationic or anionic Cys-loop receptors.

Figure 1.

Constructs used in this study. (A) Schematic depiction of constructs. The N-terminal ligand binding domain is followed by transmembrane segments (black boxes). M1, M2, and M3 are connected by short loops. The cytoplasmic domain is mainly formed by a large loop (gray box) between M3 and M4. The amino acid sequence of the α-helical end of M3, the M3M4 loop (shaded gray) and the α-helical beginning of M4(Unwin, 2005), is shown. Amino acids that were removed/introduced are shaded gray. Arginines mutated in the 5-HT3A-QDA mutant are indicated by asterisks. (B) Homology models of the 5-HT3A wild type (left) and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 (right) based on nAChR model (Unwin, 2005). Arginines in the 5-HT3A MA helices and in the truncated M3M4 loop of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 are shown in spacefilling representation. The only part of the intracellular domain that is shown (left) are the MA helices because the rest of this domain is disordered in the nAChR structure. (C) SDS-PAGE/Western blot analysis of total and plasma membrane protein fractions from oocytes. 5-HT3A-V5-wt protein (53 kD) and 5-HT3A-V5-glvM3M4 protein (41 kD) bands are observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs and Xenopus Expression

The M3M4 loop coding region in mouse 5-HT3A and human GABA-ρ1 in the pGEMHE plasmid was deleted yielding 5-HT3A-ΔM3M4 and GABA-ρ1-ΔM3M4, respectively (Fig. 1 A). Insertions coding for the Glvi M3M4 loop (SQPARAA) were introduced to obtain 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and GABA-ρ1-glvM3M4. The V5 epitope tag (GKPIPNPLLGLDSTQ) was inserted near the N terminus, following the sequence QARDTTQ (after position Q36 from the initiation methionine), to yield 5-HT3A-V5. 5-HT3A and 5-HT3A-V5 were subcloned into pXOON for HEK293 cell expression (Jespersen et al., 2002). The truncated M3M4 loop was subcloned from the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 pGEMHE construct into 5-HT3A-V5-wt-pGEMHE and into the 5-HT3A-wt and 5-HT3A-V5-wt pXOON constructs. The complete coding region was sequenced in all constructs. pGEMHE plasmids were linearized with NheI and capped mRNA prepared using T7 RNA polymerase (mMessage mMachine, Ambion). Defolliculated oocytes were prepared as previously described (Jansen and Akabas, 2006). 1 d after isolation each oocyte was injected with 10 ng of mRNA unless stated otherwise. Oocytes were kept in SOS medium (in mM): 82.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, pH 7.5 with 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen) and 5% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Experiments were conducted 3–5 d after injection unless stated otherwise.

The cDNA encoding human RIC-3 in the pGEMH19 plasmid was a generous gift from M. Treinin (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel) (Halevi et al., 2003).

Western Blotting

Oocytes were washed with Ca2+-free frog Ringer buffer (CFFR; in mM): 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.5 with NaOH. Surface proteins were biotinylated with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce Chemical Co.) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Oocytes were washed with CFFR and Tris-NaCl-Buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5), triturated at 4°C in 20 μl/oocyte lysis buffer (Tris-NaCl-buffer plus 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 10 mM N-ethyl maleimide, and 100× HALT protease inhibitor cocktail [Pierce Chemical Co.]), solubilized by rotating at 4°C for 1 h, and spun twice at 16,000 g, 4°C, 20 min to remove debris and yolk. Biotinylated proteins were bound to streptavidin beads (Pierce Chemical Co.) by rotating for 3 h, 4°C. Beads were washed with lysis buffer and bound proteins eluted with 4× SDS-sample buffer for 10 min, 37°C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (4–15% PAGE gel) (Bio-Rad Laboratories), transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and processed according to standard procedures using primary mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen) and secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Pierce Chemical Co.) antibodies and ECL (Pierce Chemical Co.).

Electrophysiology

Currents were recorded by two-electrode voltage-clamp from oocytes continuously perfused at 5 ml/min with CFFR at RT. Holding potential −60 mV. A 3 M KCl/agar bridge connected the ground electrode to the bath. Glass microelectrode resistance was <2 MΩ when filled with 3 M KCl. Data were acquired at 200 Hz and analyzed using a TEV-200 amplifier (Dagan Instruments), a Digidata 1322A data interface and pClamp 8 software (Molecular Devices). Reversal potentials in GABA ρ1 and ρ1-glvM3M4–expressing oocytes were measured using a voltage ramp protocol. From a holding potential of −70 mV the voltage was ramped to +10 mV over a 1-s interval. Ramps were repeated every 3 s. Five consecutive ramps were averaged with and without 0.5 μM GABA. The average control ramp without GABA was subtracted from the average ramp with GABA. The reversal potential was the potential at I = 0. Oocytes were allowed to equilibrate in buffer for 3 min before recording the ramps. The 115 mM NaCl solution was the regular CFFR buffer. For the 57.5 mM and 28.75 mM NaCl solutions, the NaCl concentration was reduced and replaced by d-mannitol to maintain a constant solution osmolarity. The concentrations of the KCl, MgCl2, and HEPES were the same as in CFFR.

Single Channel Recordings

Transient Transfection.

HEK293 cells were seeded at low density on polylysine-coated, 12 mm, thin glass coverslips and transfected 24 h later using a modified calcium-precipitation technique with 500 ng DNA per well. After 12 h, cells were rinsed with fresh medium and incubated at 28°C. Cells were used 24–48 h later. The coverslips were mounted on an inverted Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc. IM microscope and continuously superfused with external solution at ∼2 ml/min at RT. Cells expressing the GFP reporter were selected for patch clamp experiments.

Patch Clamp Experiments.

Pipettes pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (GC120F-10 for whole cell and GC120TF-10 for outside-out, Harvard Apparatus Ltd.) had a tip resistance of 8–13 MΩ for outside-out and 4–7 MΩ for whole-cell recording when filled with intracellular solution. Solution exchange was via a gravity-driven manifold, with a 500-μl dead space. I1 pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 1.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with CsOH. E1 bath solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with NaOH. For ion dilution experiments, the same solutions were used as in Thompson and Lummis (2003). I2 pipette solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with NaOH. E2 external solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with NaOH. E3 contained 72.5 mM NaCl and E4 36.2 mM NaCl. The osmolarity was maintained by addition of d-mannitol. Data were acquired with an EPC9 amplifier using Pulse software, v8.65 (HEKA Instruments Inc.). For whole cell experiments, data were sampled at 1 kHz and low pass-filtered at 200 Hz. For outside-out patch experiments, data were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz. Data were analyzed using Pulse and Qub software (Qin et al., 1996).

Data Analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SEM. Student's t test was used to compare the reversal potentials of the wild type and truncated constructs.

RESULTS

Membrane Expression of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and 5-HT3A wt

Using Western blotting from Xenopus oocytes we investigated the expression of wild-type 5-HT3A-V5 receptors and a truncated version, 5-HT3A-V5-glvM3M4 (Fig. 1, A and B). The V5 epitope tag was inserted near the N terminus and did not interfere with function as assessed by maximal 5-HT currents and EC50s (unpublished data). Homogenized oocytes were solubilized in Triton X-100/deoxycholate to generate a total protein fraction. For plasma membrane localization, oocytes were surface labeled with sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin before solubilization in Triton X-100/deoxycholate. Biotinylated plasma membrane proteins were purified using streptavidin-coated beads. On Western blots, bands corresponding to 5-HT3A-V5 and 5-HT3A-V5-glvM3M4, respectively, were detected via the V5 epitope tag in both the total and plasma membrane protein fractions (Fig. 1 C). Comparable results were obtained with the proteins expressed in HEK293T cells (unpublished data). The presence of HT3A-V5-glvM3M4 protein in the plasma membrane fraction implies that subunits lacking the large intracellular domain are capable of translocation to the plasma membrane.

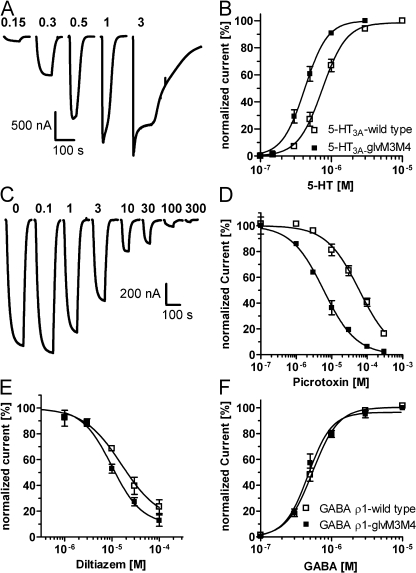

5-HT3A-glvM3M4 Receptors Are Functional

The function of truncated 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channels was assayed by two-electrode voltage clamp recording. 5-HT application induced rapid inward currents in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and 5-HT3A–expressing oocytes (Fig. 2 A), but not in water-injected or uninjected oocytes (not depicted). 5-HT concentration–response relationships were determined (Fig. 2 B). The 5-HT EC50 values for 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and 5-HT3A were 0.41 ± 0.03 μM (n = 8) and 0.76 ± 0.06 μM (n = 8), respectively. The HT3A-ΔM3M4 construct (Fig. 1 A) that lacked any amino acids between the putative ends of the M3 and M4 segments did not yield functional channels.

Figure 2.

The pharmacological characteristics of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 are comparable to 5-HT3A. (A) Application of increasing 5-HT concentrations elicits inward currents with increasing amplitudes in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4–expressing oocyte. 5-HT concentrations (μM) are above corresponding trace. (B) Concentration–response relationship for 5-HT activation of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 (closed squares) and 5-HT3A (open squares). Currents were normalized to the maximum response for individual oocytes (n = 8). (C) Coapplication of increasing picrotoxin concentrations with the 5-HT EC30 concentration to 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 inhibits 5-HT–activated currents. Picrotoxin concentrations (μM) are above corresponding trace. (D) Picrotoxin concentration–inhibition relationship for 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 (closed squares) and 5-HT3A (open squares) (n ≥ 3). (E) Diltiazem concentration–inhibition relationship. Experiments performed as in C except with diltiazem in place of picrotoxin (n ≥ 3). (F) GABA concentration–response curves for activation of GABA ρ1-glvM3M4 (closed squares) and GABA ρ1 (open squares) (n ≥ 3). In all panels, data points are mean ± SEM.

To examine the generality of the results for other Cys-loop receptors, we characterized the truncated GABA ρ1-glvM3M4 receptors (Fig. 1 A). They were functional with a GABA EC50 of 0.47 ± 0.05 μM (n = 3) as compared with 0.54 ± 0.03 μM (n = 3) for wt GABA ρ1 (Fig. 2 F). Thus, truncation of the M3M4 cytoplasmic loop in both cationic and anionic Cys-loop receptor superfamily members resulted in functional ligand-gated channels.

Pharmacological Equivalence of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and 5-HT3A-wt

To demonstrate the structural similarity of the channels formed by 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and 5-HT3A-wt receptors we examined the effects of a variety of competitive, noncompetitive, and mixed mode antagonists. Picrotoxin inhibits 5-HT3A and GABAA receptors (Das et al., 2003). At GABAA receptors, picrotoxin acts primarily as a noncompetitive, use-dependent, open-channel blocker (Newland and Cull-Candy, 1992; Yoon et al., 1993). Its binding site is near the cytoplasmic end of the channel-lining M2 segments at the 2’ level (fFrench-Constant et al., 1993; Xu et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2006) below the channel gate (Bali and Akabas, 2007). Using a 5-HT EC30 concentration, the picrotoxin IC50 value was 60 ± 10 μM (n = 3) and 6.8 ± 1.1 μM (n = 6) for 5-HT3A-wt and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4, respectively (Fig. 2, C and D). Diltiazem inhibits 5-HT3A receptors. Its mode of action includes open-channel block and other allosteric noncompetitive interactions (Gunthorpe and Lummis, 1999). Using 0.3 μM 5-HT, the diltiazem IC50 values were 16 ± 1 μM (n = 4) and 12 ± 3 μM (n = 3) for 5-HT3A and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4, respectively (Fig. 2 E). QX-222, a quaternary amine, is an open channel blocker of 5-HT3A and nAChR (Sepulveda et al., 1994). QX-222 binds in the nAChR channel between the M2 6’ and 10’ positions (Leonard et al., 1988). The binding site in 5-HT3A channels has not been determined. QX-222 (20 μM) inhibited 5-HT EC70 currents in 5-HT3A-wt and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 by 80 ± 4% (n = 6) and 79 ± 2% (n = 6), respectively.

Ondansetron, a 5-HT3A competitive antagonist, inhibits mouse 5-HT3A receptors with a high picomolar IC50 (Costall et al., 1987). Application of an EC30 concentration of 5-HT together with an ondansetron concentration that was 1/3 of the 5-HT concentration inhibited the 5-HT currents by 98.2 ± 0.4% (n = 3) and 98.8 ± 0.4% (n = 4) in 5-HT3A and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4, respectively.

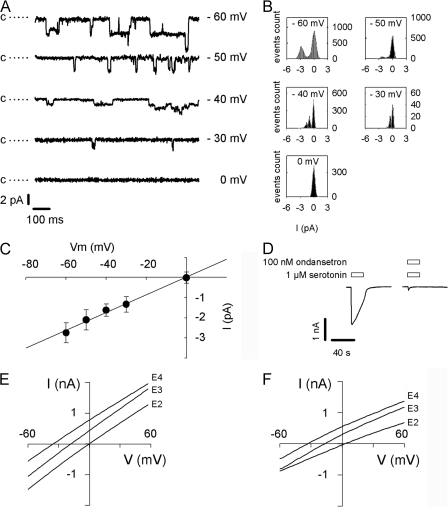

5-HT3A-glvM3M4 Ion Selectivity and Single Channel Conductance

5-HT (1 μM) evoked currents in HEK293T cells transiently expressing either 5-HT3A or 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 receptors. Whole cell currents ranged from 1 to 5 nA and were totally inhibited by 100 nM ondansetron (Fig. 3 D). No 5-HT–activated current was present in cells transfected with empty vector.

Figure 3.

5-HT3A-glvM3M4 is cation selective with increased single channel conductance. (A) Representative single channel recordings from an outside-out patch containing 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channels at different holding voltages in the presence of 1 μM 5-HT. The closed state level is indicated by c and dotted line; openings are downward deflections. Records filtered at 1 kHz for display purpose. (B) All-points histograms fitted with two or three Gaussian functions representing closed level and one or two open channels. (C) Mean current and standard deviation obtained from the fit in B plotted as a function of voltage. Chord conductance estimated by linear regression. (D) 100 nM ondansetron inhibits whole cell current induced by 1 μM 5-HT. (E) Change in reversal potential induced by reduction in external NaCl concentration (E2, E3, and E4 contain 145, 72.5, and 36.25 mM NaCl, respectively) for 5-HT3A and (F) for 5-HT3A-glvM3M4.

5-HT3A receptors form cation-selective channels (Maricq et al., 1991). We characterized the charge selectivity of the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channels by measuring the shift in reversal potential following a decrease in the external NaCl concentration. 500-ms voltage ramps were applied during a 1 μM 5-HT pulse. 5-HT–induced currents for 5-HT3A and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 were not significantly different from each other or from 0 mV in extracellular E2 buffer containing 145 mM NaCl (Table I). Decreasing the extracellular NaCl concentration leads to negative shifts of the reversal potential for both 5-HT3A-wt and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4, in agreement with the channels being cation selective (Table I). With the extracellular solution containing E4 buffer ([NaCl] = 36.25 mM), within the limitations of our measurements, the measured reversal potentials are not significantly different from the Nernst potential for Na+ (Table I). From the reversal potentials measured in E4 buffer, the PNa/PCl > 20. Because the cation to anion permeability ratios calculated from the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation are very sensitive to small changes in reversal potentials that are near ideal selectivity and because the measured reversal potentials are not significantly different from each other, we have not calculated separate selectivity ratios for the wild type and truncated channels. Rather, we infer that the M3M4 loop removal did not significantly alter the nearly ideal cation selectivity of the wild-type channel.

TABLE I.

Reversal Potentials of 5-HT–induced Currents in HEK293 Cells Expressing either Wild Type or Truncated 5-HT3A Receptors Are Similar following Reduction of the Bath Solution NaCl Concentration

| Extracellular Buffera | E2 | E3 | E4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| 5-HT3A | 2 ± 0.7 | −15 ± 0.4 | −32 ± 0.5 |

| 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 | −1 ± 1.5 | −12 ± 2.5 | −36 ± 4.5 |

| Na+ Nernst potentialb | −1 | −18 | −34 |

| Cl− Nernst potentialb | 0.3 | 18 | 34 |

Extracellular buffer composition defined in Materials and methods.

Theoretical reversal potential calculated from the Nernst Equation for an ideally selective channel.

Homomeric 5-HT3A receptors have a single channel conductance (γ) estimated to be ∼0.6 pS by noise analysis. Coexpressing 5-HT3B subunits to obtain heteromeric 5-HT3A/B receptors increases γ (Davies et al., 1999) as does replacing three arginines in the cytosolic, MA helix that are unique to 5-HT3A with the corresponding residues from the 5-HT3B subunit (Kelley et al., 2003). The 5-HT3A triple mutant R432Q/R436D/R440A (QDA mutant) has a γ of 21 pS, suggesting that cytoplasmic domain residues influence channel conductance. We determined the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 chord conductance from single channel event amplitudes recorded at different holding voltages (Fig. 3 A). The single channel currents were determined from the all-points histograms (Fig. 3 B) at each holding potential. The chord conductance in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4–expressing cells was 43.5 ± 1.5 pS (n = 5) (Fig. 3 C). We previously determined the 5-HT3A-QDA mutant slope conductance to be 38 ± 7.7 pS (Reeves et al., 2005).

GABA ρ1-glvM3M4 Are Anion Selective

To determine whether removal of the M3M4 loop from the GABA ρ1 receptor altered the anion to cation selectivity of the resultant channels we expressed the wild-type GABA ρ1 and the truncated GABA ρ1-glvM3M4 in Xenopus oocytes. We measured the reversal potentials following reduction of the NaCl concentration in the extracellular bath solution (Table II). There were no statistically significant differences between the measured reversal potentials for oocytes expressing ρ1-wild-type or ρ1-glvM3M4 when the extracellular bath contained CFFR ([NaCl] = 115 mM) or following reduction of the NaCl concentration to 57.5 or 28.75 mM. The internal concentrations of Cl− and monovalent cations are uncertain, making it difficult to calculate the precise chloride to cation permeability ratios. However, since the wild-type ρ1 channel was previously shown to be essentially impermeable to cations (Wotring et al., 1999) and in our experiments, the reversal potentials are not significantly different between ρ1-wild-type and ρ1-glvM3M4, we infer that deletion of the ρ1 M3M4 loop does not significantly alter the nearly ideal chloride to cation permeability ratio of the deletion construct.

TABLE II.

Reversal Potentials of GABA-induced Currents in Oocytes Expressing either Wild Type or Truncated GABA ρ1 Receptors Are Similar following Reductions in the Bath Solution NaCl Concentration

| 115 mM NaCla | 57.5 mM NaCla | 28.75 mM NaCla | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| GABA ρ1 wild type | −21.1 ± 1.2b (n = 5) | −8.5 ± 1.8 (n = 5) | 5.9 ± 2.0 (n = 5) |

| GABA ρ1-glvM3M4 | −19.9 ± 0.9 (n = 5) | −6.1 ± 1.3 (n = 4) | 6.7 ± 1.5 (n = 4) |

Concentration of NaCl in the extracellular buffer.

Data in mV are mean ± SEM (n = number of oocytes).

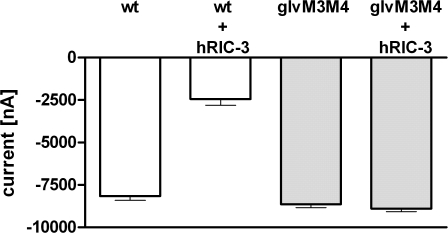

Interaction with hRIC-3 Abolished in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4

RIC-3 was identified as a requirement for the function of Caenorhabditis elegans acetylcholine receptors (DEG-3) (Halevi et al., 2002, 2003). Coexpression of human RIC-3 (hRIC-3) with mouse 5-HT3A-wt reportedly abolished 5-HT–induced currents in oocytes (Halevi et al., 2003). Topology predictions suggest that RIC-3 has two transmembrane domains that are separated by a proline-rich region, with the N terminus and the highly charged C-terminal coiled-coil domain in the cytoplasm. Coexpression of hRIC-3 and 5-HT3A reduced the 5-HT peak currents by 70 ± 4% (n = 8) as compared with currents from oocytes expressing 5-HT3A alone (Fig. 4). Coexpression of hRIC-3 and 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 did not have any effect on 5-HT–induced currents (103 ± 2% of the current size without hRIC-3, n = 5).

Figure 4.

Coexpression of hRIC-3 inhibits 5-HT3A but not 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 expression. Average peak currents elicited by a saturating 5-HT concentration recorded in oocytes injected with 10 ng mRNA for 5-HT3A or 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 either alone or together with 5 ng mRNA for hRIC-3.

DISCUSSION

The goal of these experiments was to determine whether the large cytoplasmic domain formed by the M3M4 loop was essential for folding, assembly, trafficking, and function in Cys-loop receptors. Replacing 115 amino acids wforming the entire 5-HT3A M3M4 loop with a heptapeptide (SQPARAA) corresponding to the M3M4 loop sequence in the Glvi prokaryotic homologue yielded receptors that trafficked to the plasma membrane and were functional. Similar results were obtained with the GABA ρ1 receptor, indicating that this is likely to be a general property of the Cys-loop receptor family. We infer that the M3M4 loop is not essential for the correct folding, assembly into pentamers, or trafficking from the ER to the plasma membrane.

A previous study showed that deletion of part of the GABAA α1 subunit M3M4 loop (the region aligned with the MA helix was still present in the truncated construct) yielded plasma membrane–localized receptors with an intact benzodiazepine binding site when coexpressed with full-length β3 and γ2s subunits. The channel function of these receptors was not investigated (Peran et al., 2006). These receptors displayed increased mobility in the membrane, suggesting that the deleted part of the M3M4 loop is involved in cytoskeletal interactions, but not assembly or surface targeting.

We infer that the overall topology, folding, and assembly of the extracellular and transmembrane domains were preserved in the truncated 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 receptors. This is supported by the detailed functional characterization of the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 construct that had functional properties similar to those of wild-type 5-HT3A channels. The absence of function for the 5-HT3A-ΔM3M4 construct, which lacked any connecting residues between the M3 and M4 segments, suggests that at least a few residues are required between the putative ends of M3 and M4 to allow M4 to reenter the membrane. A properly folded and oriented M4 segment may be required for function. In the nAChR, deletion of the α-subunit M4 segment resulted in nonfunctional receptors (Mishina et al., 1985).

The functional characteristics of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 receptors support our inference that the structure of the extracellular and transmembrane domains was preserved in the truncated construct. Consistent with the preservation of the binding site, the competitive antagonist ondansetron inhibited with similar efficacy in truncated and wild-type receptors. Furthermore, the lack of significant change in the 5-HT EC50 suggests that the binding sites and the transduction mechanism that couples agonist binding to channel gating were intact in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channels. We probed the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channel structure by characterizing the efficacy of putative channel blockers and by functional characterization of the channel's selectivity and conductance. For the drugs that are thought to bind in the channel, the mixed mode antagonists, QX-222 (Sepulveda et al., 1994) and diltiazem (Gunthorpe and Lummis, 1999), showed similar inhibition but the open channel blocker picrotoxin (Newland and Cull-Candy, 1992; fFrench-Constant et al., 1993; Yoon et al., 1993; Xu et al., 1995; Bali and Akabas, 2007) had a 10-fold lower IC50 in the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4, implying that there may be changes in its binding site within the channel or in the access pathway to the binding site. Elucidating the basis of this change will require further experiments. Pore geometry and the distribution of charges on the vestibule surfaces contribute to charge selectivity (Unwin, 2005). The cation selectivity of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 was similar to wild type, both discriminate to a similar extent between Na+ and Cl−. This implies that M3M4 loop residues do not play a role in the cation selectivity mechanism. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated a role for residues in the M1-M2 loop and in the M2 segment in the charge selectivity mechanism (Galzi et al., 1992; Keramidas et al., 2000; Gunthorpe and Lummis, 2001). We infer that the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 pore geometry is not significantly altered because (a) the charge selectivity is not influenced by removal of the M3M4 loop and (b) the pharmacological characterization with channel blocking agents was similar to wild type.

In contrast, as expected, the single channel conductance of 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 channels was significantly larger than that of wild type. Previous studies using 5-HT3A/5-HT3B chimeras identified three arginines in the MA helix unique to 5-HT3A that when replaced by their 5-HT3B counterparts (QDA mutant) increased the single channel conductance (Davies et al., 1999). Mutations at aligned positions in neuronal ACh receptor subunits had similar effects on conductance (Hales et al., 2006) but similar experiments have not been performed in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor subunit. In the nAChR structural model the five MA helices assemble to form a cytosolic conical vestibule to the ion channel with five lateral portals framed by the MA helices providing access to the cytosol (Miyazawa et al., 1999; Unwin, 2005). The portal diameter is sufficient to allow permeation of Na+ or K+ ions with their first hydration shell (∼8 Å). The arginines replaced in the 5-HT3A-QDA mutant are likely to be part of the portal lining, thus limiting cation translocation into and out of the vestibule by electrostatic and steric interactions (Unwin, 2005). The three arginines are removed in 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 and are replaced by just one arginine in the heptapeptide Glvi loop. The 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 single channel conductance was ∼70-fold greater than 5-HT3A and comparable to 5-HT3A-QDA. We infer that no additional features in the whole M3M4 loop besides the three arginines are involved in limiting the 5-HT3A single channel conductance.

The extent to which the limited cytoplasmic domain structure in the Torpedo ACh receptor structure and the existence of the portals that allow entry into the cytoplasmic vestibule can be generalized to anion-selective Cys-loop receptor family members is, at present, unknown. The finding that removal of the GABA ρ1 M3M4 loop did not alter the anion selectivity of the resultant channels suggests that as for the 5-HT3A receptor, this domain is not important in determining charge selectivity. Further experiments will be necessary to elucidate the role of this domain, if any, in the functional properties of GABA ρ1 channels.

The M3M4 loop was implicated in receptor targeting in a variety of Cys-loop receptors, including the nAChR (Williams et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2006), the GABAA (Chen and Olsen, 2007), and the 5-HT3 receptor (Castillo et al., 2005). Several groups have studied the role of RIC-3 in 5-HT3 receptor trafficking (Castillo et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2005). RIC-3 was originally identified in C. elegans where it facilitates nAChR cell surface expression (Halevi et al., 2002, 2003). RIC-3 coexpression with 5-HT3 receptors has yielded conflicting results. Coexpression of hRIC-3 and mouse 5-HT3A abolished 5-HT3A cell surface expression (Castillo et al., 2005), whereas another study suggested that hRIC-3 coexpression with human 5-HT3A increased surface expression in COS7 cells, where RIC-3 was localized to the ER (Cheng et al., 2005). In the former study the RIC-3 potentiation of nAChR α7 expression was attributed to residues in the intracellular amphipathic preM4 MA helix, whereas a single extracellular preM1 residue was implicated in the RIC-3 mediated inhibition of α7/5-HT3A chimera expression (Castillo et al., 2005). One interpretation of these disparate results is that the effect of RIC-3 coexpression with Cys-loop receptors may depend on the animal species from which both proteins—RIC-3 and Cys-loop subunit—are derived, as well as the specific Cys-loop subunit investigated (Halevi et al., 2002; Halevi et al., 2003; Castillo et al., 2005). Our results demonstrate that hRIC-3 reduced whole cell currents, probably by inhibiting cell surface expression, of mouse 5-HT3A receptor and that removal of the M3M4 loop, in the 5-HT3A-glvM3M4 construct, eliminated the inhibitory effect of hRIC-3 coexpression. The detailed nature of how RIC-3 interferes with 5-HT3 subunit expression remains to be elucidated. Our present work strongly suggests that for the attenuation of mouse 5-HT3A receptor expression by hRIC-3 in oocytes, the presence of at least some residues in the M3M4 loop is essential.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Cys-loop receptors are modular proteins formed by linking together two domains. Functional chimeras of the N- and C-terminal domains of ACh α7 and 5-HT3A subunits and glycine and GABA ρ1 subunits support this view (Eisele et al., 1993; Mihic et al., 1997). We now suggest that the Cys-loop receptors actually are formed from three separate modules, the extracellular domain, the transmembrane domain, and a third domain formed by the cytoplasmic M3M4 loop. The ability of the 5-HT3A and GABA ρ1 constructs lacking the long M3M4 loop to fold, assemble, traffic to the plasma membrane, and function as ligand-gated ion channels suggests that the cytoplasmic M3M4 loop may be a separate folding domain from the rest of the protein.

The M3M4 loop structure is poorly resolved in the 4-Å resolution Torpedo AChR structure (Miyazawa et al., 2003; Unwin, 2005). The only part of the M3M4 loop that is resolved is the MA helix just proximal to M4. We hypothesize that the failure of most of the M3M4 loop to be well resolved in the 4-Å resolution nAChR structure is due to the fact that it may contain intrinsically disordered regions. Efforts to crystallize a protein with the AChR δ subunit M3M4 loop sequence failed and circular dichroism and NMR data of the protein suggest that it is largely unstructured (Kottwitz et al., 2004). Also, green fluorescent protein has been inserted into the M3M4 loop of several Cys-loop receptors without significant effects on function (Gensler et al., 2001; Li et al., 2002; Ilegems et al., 2004). This suggests that the M3M4 loop might have disordered regions that can accommodate the insertions. Furthermore, recent evidence has suggested that the cytoplasmic domains of ion channels involved in protein–protein interactions that mediate cytoskeletal protein binding or posttranslational modification by kinases and phosphatases may involve intrinsically unstructured regions. In potassium channels containing a C-terminal PDZ binding motif the adjacent region of the C terminus is unstructured (Magidovich et al., 2007). The unstructured regions may undergo transitions to more defined structures following protein binding or posttranslational modification. The cytoplasmic C terminus of the connexin43 gap junction protein is largely unstructured but undergoes a transition to a more structured state following c-Src binding (Duffy et al., 2002). To investigate the existence of disordered regions in the 5-HT3A M3M4 loop we used the DISOPRED2 computational algorithm to predict disordered regions (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/disopred/) (Schlessinger et al., 2007). The only part of the 5-HT3A protein that had a significant disorder probability was the unresolved part of the M3M4 loop. It is intriguing to suggest that binding of RIC-3 to the unstructured M3M4 loop may initiate a transition from unstructured to structured segments for both proteins. RIC-3 possesses a large coiled-coil domain besides its two transmembrane domains (Halevi et al., 2003). Many coiled-coil proteins feature an unfolded monomeric state, whereas more defined structural features are obtained after homo- or heterodimerization (Uversky et al., 2000). The existence of the M3M4 loop in metazoans and its absence in prokaryotes indicates that its function may be to facilitate Cys-loop receptor localization at specific synapses and to allow covalent modification through phosphorylation to alter trafficking and internalization. Elucidating the structure of this third domain will be essential for understanding how these critical protein–protein interactions are formed that allow the localization of Cys-loop receptors that is essential for their role in fast synaptic transmission.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Millet Treinin for providing the human RIC-3 construct in the pGEMH19 expression vector. We thank Dr. David Reeves for generating the 5-HT3A-V5 epitope-tagged construct and for helpful advice with the patch clamp experiments, and Jarrett Linder for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants NS030808 and GM077660 (to M.H. Akabas) and by K99-NS059841 (to M. Jansen).

The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or NIH.

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor. served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CFFR, Ca2+-free frog Ringer buffer; 5-HT3A, 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3A; LGIC, ligand-gated ion channel; MA, membrane-associated; RT, room temperature.

References

- Bali, M., and M.H. Akabas. 2007. The location of a closed channel gate in the GABAA receptor channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:145–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet, N., L. Prado de Carvalho, J. Cartaud, J. Neyton, C. Le Poupon, A. Taly, T. Grutter, J.P. Changeux, and P.J. Corringer. 2007. A prokaryotic proton-gated ion channel from the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor family. Nature. 445:116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc, K., W.J. van Dijk, R.V. Klaassen, M. Schuurmans, J. van Der Oost, A.B. Smit, and T.K. Sixma. 2001. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 411:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, M., J. Mulet, L.M. Gutierrez, J.A. Ortiz, F. Castelan, S. Gerber, S. Sala, F. Sala, and M. Criado. 2005. Dual role of the RIC-3 protein in trafficking of serotonin and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27062–27068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., K.A. Durkin, and J.E. Casida. 2006. Structural model for γ-aminobutyric acid receptor noncompetitive antagonist binding: widely diverse structures fit the same site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:5185–5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.W., and R.W. Olsen. 2007. GABAA receptor associated proteins: a key factor regulating GABAA receptor function. J. Neurochem. 100:279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A., N.A. McDonald, and C.N. Connolly. 2005. Cell surface expression of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors is promoted by RIC-3. J. Biol. Chem. 280:22502–22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costall, B., A.M. Domeney, R.J. Naylor, and M.B. Tyers. 1987. Effects of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, GR38032F, on raised dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic system of the rat and marmoset brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 92:881–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, P., C.L. Bell-Horner, T.K. Machu, and G.H. Dillon. 2003. The GABA(A) receptor antagonist picrotoxin inhibits 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 44:431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.A., M. Pistis, M.C. Hanna, J.A. Peters, J.J. Lambert, T.G. Hales, and E.F. Kirkness. 1999. The 5-HT3B subunit is a major determinant of serotonin-receptor function. Nature. 397:359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, H.S., P.L. Sorgen, M.E. Girvin, P. O'Donnell, W. Coombs, S.M. Taffet, M. Delmar, and D.C. Spray. 2002. pH-dependent intramolecular binding and structure involving Cx43 cytoplasmic domains. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36706–36714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele, J.L., S. Bertrand, J.L. Galzi, A. Devillers-Thiery, J.P. Changeux, and D. Bertrand. 1993. Chimaeric nicotinic-serotonergic receptor combines distinct ligand binding and channel specificities. Nature. 366:479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- fFrench-Constant, R.H., T.A. Rocheleau, J.C. Steichen, and A.E. Chalmers. 1993. A point mutation in a Drosophila GABA receptor confers insecticide resistance. Nature. 363:449–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galzi, J.L., A. Devillers-Thiery, N. Hussy, S. Bertrand, J.P. Changeux, and D. Bertrand. 1992. Mutations in the channel domain of a neuronal nicotinic receptor convert ion selectivity from cationic to anionic. Nature. 359:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensler, S., A. Sander, A. Korngreen, G. Traina, G. Giese, and V. Witzemann. 2001. Assembly and clustering of acetylcholine receptors containing GFP-tagged ε or γ subunits: selective targeting to the neuromuscular junction in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:2209–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe, M.J., and S.C. Lummis. 1999. Diltiazem causes open channel block of recombinant 5-HT3 receptors. J. Physiol. 519:713–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe, M.J., and S.C. Lummis. 2001. Conversion of the ion selectivity of the 5-HT(3a) receptor from cationic to anionic reveals a conserved feature of the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10977–10983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales, T.G., J.I. Dunlop, T.Z. Deeb, J.E. Carland, S.P. Kelley, J.J. Lambert, and J.A. Peters. 2006. Common determinants of single channel conductance within the large cytoplasmic loop of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 and α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8062–8071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi, S., J. McKay, M. Palfreyman, L. Yassin, M. Eshel, E. Jorgensen, and M. Treinin. 2002. The C. elegans ric-3 gene is required for maturation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. EMBO J. 21:1012–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi, S., L. Yassin, M. Eshel, F. Sala, S. Sala, M. Criado, and M. Treinin. 2003. Conservation within the RIC-3 gene family. Effectors of mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34411–34417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilegems, E., H.M. Pick, C. Deluz, S. Kellenberger, and H. Vogel. 2004. Noninvasive imaging of 5-HT3 receptor trafficking in live cells: from biosynthesis to endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:53346–53352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, M., and M.H. Akabas. 2006. State-dependent cross-linking of the M2 and M3 segments: functional basis for the alignment of GABAA and acetylcholine receptor M3 segments. J. Neurosci. 26:4492–4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen, T., M. Grunnet, K. Angelo, D.A. Klaerke, and S.P. Olesen. 2002. Dual-function vector for protein expression in both mammalian cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biotechniques. 32:536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, A. 2002. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, S.P., J.I. Dunlop, E.F. Kirkness, J.J. Lambert, and J.A. Peters. 2003. A cytoplasmic region determines single-channel conductance in 5-HT3 receptors. Nature. 424:321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramidas, A., A.J. Moorhouse, C.R. French, P.R. Schofield, and P.H. Barry. 2000. M2 pore mutations convert the glycine receptor channel from being anion- to cation-selective. Biophys. J. 79:247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottwitz, D., V. Kukhtina, N. Dergousova, T. Alexeev, Y. Utkin, V. Tsetlin, and F. Hucho. 2004. Intracellular domains of the delta-subunits of Torpedo and rat acetylcholine receptors–expression, purification, and characterization. Protein Expr. Purif. 38:237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, R.J., C.G. Labarca, P. Charnet, N. Davidson, and H.A. Lester. 1988. Evidence that the M2 membrane-spanning region lines the ion channel pore of the nicotinic receptor. Science. 242:1578–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester, H.A., M.I. Dibas, D.S. Dahan, J.F. Leite, and D.A. Dougherty. 2004. Cys-loop receptors: new twists and turns. Trends Neurosci. 27:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, P., E.M. Slimko, and H.A. Lester. 2002. Selective elimination of glutamate activation and introduction of fluorescent proteins into a Caenorhabditis elegans chloride channel. FEBS Lett. 528:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, R.L., and R.W. Olsen. 1994. GABAA receptor channels. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 17:569–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidovich, E., I. Orr, D. Fass, U. Abdu, and O. Yifrach. 2007. Intrinsic disorder in the C-terminal domain of the Shaker voltage-activated K+ channel modulates its interaction with scaffold proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:13022–13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq, A.V., A.S. Peterson, A.J. Brake, R.M. Myers, and D. Julius. 1991. Primary structure and functional expression of the 5HT3 receptor, a serotonin-gated ion channel. Science. 254:432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic, S.J., Q. Ye, M.J. Wick, V.V. Koltchine, M.D. Krasowski, S.E. Finn, M.P. Mascia, C.F. Valenzuela, K.K. Hanson, E.P. Greenblatt, et al. 1997. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABA(A) and glycine receptors. Nature. 389:385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina, M., T. Tobimatsu, K. Imoto, K. Tanaka, Y. Fujita, K. Fukuda, M. Kurasaki, H. Takahashi, Y. Morimoto, T. Hirose, et al. 1985. Location of functional regions of acetylcholine receptor α-subunit by site-directed mutagenesis. Nature. 313:364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa, A., Y. Fujiyoshi, M. Stowell, and N. Unwin. 1999. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4.6 Å resolution: transverse tunnels in the channel wall. J. Mol. Biol. 288:765–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa, A., Y. Fujiyoshi, and N. Unwin. 2003. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 423:949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland, C.F., and S.G. Cull-Candy. 1992. On the mechanism of action of picrotoxin on GABA receptor channels in dissociated sympathetic neurones of the rat. J. Physiol. 447:191–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peran, M., H. Hooper, H. Boulaiz, J.A. Marchal, A. Aranega, and R. Salas. 2006. The M3/M4 cytoplasmic loop of the α1 subunit restricts GABAARs lateral mobility: a study using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 63:747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, F., A. Auerbach, and F. Sachs. 1996. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophys. J. 70:264–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, D.C., M. Jansen, M. Bali, T. Lemster, and M.H. Akabas. 2005. A role for the β1-β2 loop in the gating of 5-HT3 receptors. J. Neurosci. 25:9358–9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger, A., J. Liu, and B. Rost. 2007. Natively unstructured loops differ from other loops. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3:e140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, M.I., J. Baker, and S.C. Lummis. 1994. Chlorpromazine and QX222 block 5-HT3 receptors in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. Neuropharmacology. 33:493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasneem, A., L.M. Iyer, E. Jakobsson, and L. Aravind. 2005. Identification of the prokaryotic ligand-gated ion channels and their implications for the mechanisms and origins of animal Cys-loop ion channels. Genome Biol. 6:R4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temburni, M.K., R.C. Blitzblau, and M.H. Jacob. 2000. Receptor targeting and heterogeneity at interneuronal nicotinic cholinergic synapses in vivo. J. Physiol. 525:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.J., and S.C. Lummis. 2003. A single ring of charged amino acids at one end of the pore can control ion selectivity in the 5-HT3 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140:359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, N. 2005. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 346:967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V.N., J.R. Gillespie, and A.L. Fink. 2000. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 41:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.M., M.K. Temburni, M.S. Levey, S. Bertrand, D. Bertrand, and M.H. Jacob. 1998. The long internal loop of the α3 subunit targets nAChRs to subdomains within individual synapses on neurons in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 1:557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotring, V.E., Y. Chang, and D.S. Weiss. 1999. Permeability and single channel conductance of human homomeric rho1 GABAC receptors. J. Physiol. 521(Pt 2):327–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J., Y. Zhu, and S.F. Heinemann. 2006. Identification of sequence motifs that target neuronal nicotinic receptors to dendrites and axons. J. Neurosci. 26:9780–9793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M., D.F. Covey, and M.H. Akabas. 1995. Interaction of picrotoxin with GABAA receptor channel-lining residues probed in cysteine mutants. Biophys. J. 69:1858–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K.W., D.F. Covey, and S.M. Rothman. 1993. Multiple mechanisms of picrotoxin block of GABA-induced currents in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 464:423–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]