Abstract

The L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) participates in neuronal development. Mutations in the human L1 gene can cause the neurological disorder CRASH (corpus callosum hypoplasia, retardation, adducted thumbs, spastic paraplegia, and hydrocephalus). This study presents genetic data that shows that L1-like adhesion gene 2 (LAD-2), a Caenorhabditis elegans L1CAM, functions in axon pathfinding. In the SDQL neuron, LAD-2 mediates dorsal axon guidance via the secreted MAB-20/Sema2 and PLX-2 plexin receptor, the functions of which have largely been characterized in epidermal morphogenesis. We use targeted misexpression experiments to provide in vivo evidence that MAB-20/Sema2 acts as a repellent to SDQL. Coimmunoprecipitation assays reveal that MAB-20 weakly interacts with PLX-2; this interaction is increased in the presence of LAD-2, which can interact independently with MAB-20 and PLX-2. These results suggest that LAD-2 functions as a MAB-20 coreceptor to secure MAB-20 coupling to PLX-2. In vertebrates, L1 binds neuropilin1, the obligate receptor to the secreted Sema3A. However, invertebrates lack neuropilins. LAD-2 may thus function in the semaphorin complex by combining the roles of neuropilins and L1CAMs.

Introduction

During nervous system development, complex neural networks and connections are formed to ensure proper connections at appropriate times. An important aspect in the construction of these neural networks is directed migration of axons, a process that depends on the ability of the axons to sense and respond to environmental cues that include semaphorins, netrins, and slits (for review see Chilton, 2006). Axonal response to these cues is dependent on how the different receptors for these molecules integrate the variety of signals the axons encounter.

Semaphorins are a large family of secreted or membrane-associated glycoproteins that can act as both repellents and attractants to direct axon migration (for review see Kruger et al., 2005). The transmembrane semaphorins bind directly to plexins, the predominant family of semaphorin receptors that transduces semaphorin signaling, which results in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement via proteins that include collapsin response mediator protein and Rac GTPases. In contrast to the membrane-bound semaphorins, the Sema3 class of secreted semaphorins generally does not bind plexins. Instead, they bind directly to neuropilins, transmembrane proteins that are required to link Sema3 to plexin receptors, which transduce Sema3 signaling (for review see Kruger et al., 2005).

The L1 family of cell adhesion molecules (L1CAMs), which is composed of L1, NrCAM, neurofascin, and CHL1, has been implicated in mediating axon guidance via the semaphorin pathway. In vertebrates, mutations in the X-linked L1 gene can result in the neurological CRASH disorder (corpus callosum hypoplasia, retardation, adducted thumbs, spastic paraplegia, and hydrocephalus; for review see Kenwrick et al., 2000). Analysis of L1 knockout mice revealed axon guidance defects in the corticospinal tract (Cohen et al., 1998). Cortical neurons cultured from L1 knockout mice are unresponsive to Sema3A (Castellani et al., 2000), which suggests a role for L1 in Sema3 signaling. L1 was subsequently shown to physically interact with neuropilin1. Although it is not clear in vivo how L1 functions in Sema3A signaling, cell culture assays reveal that the L1–neuropilin1 interaction may result in Sema3A-induced endocytosis of neuropilin1, which raises the possibility that L1 may regulate axon sensitivity to Sema3A (Castellani et al., 2000, 2004). Recently, NrCAM was similarly shown to bind Nrp2 to mediate Sema3B signaling (Falk et al., 2005).

L1CAMs, semaphorins, and plexins are conserved in both Caenorhabitis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster but they lack a neuropilin, raising the possibility that neuropilins may have evolved more recently in vertebrates. The C. elegans semaphorins are comprised of the transmembrane Sema1 proteins encoded by the smp-1 and smp-2 genes and the secreted Sema2 protein encoded by mab-20 (Roy et al., 2000; Ginzburg et al., 2002). These semaphorins function in epidermal morphogenesis via the plexins encoded by plx-1 and plx-2 (Fujii et al., 2002; Ikegami et al., 2004) but their roles in axon guidance are not known. The C. elegans L1CAMs are encoded by L1-like adhesion gene 1 (lad-1)/sax-7 and lad-2. The LAD-1/SAX-7 protein was previously characterized as having roles in maintaining neuronal positioning (Sasakura et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005).

This study demonstrates that the C. elegans L1CAM homologue LAD-2 functions in axon pathfinding. LAD-2 mediates the functions of the secreted MAB-20/Sema2 and its plexin receptor PLX-2 to control axon navigation of the SDQL neuron, which responds to MAB-20 as a repulsive cue. Biochemical data show that LAD-2 (a) forms protein complexes independently with MAB-20 and PLX-2 and (b) acts to reinforce coupling of MAB-20 to PLX-2, which can interact by themselves, albeit weakly. These results suggest that LAD-2 may function similarly to neuropilin by acting as a MAB-20 coreceptor to secure MAB-20 with PLX-2 in a protein complex required for semaphorin signaling, revealing an ancient role of L1CAM in the conserved process of semaphorin signaling in axon pathfinding.

Results

LAD-2 is a neuronal-specific noncanonical L1CAM

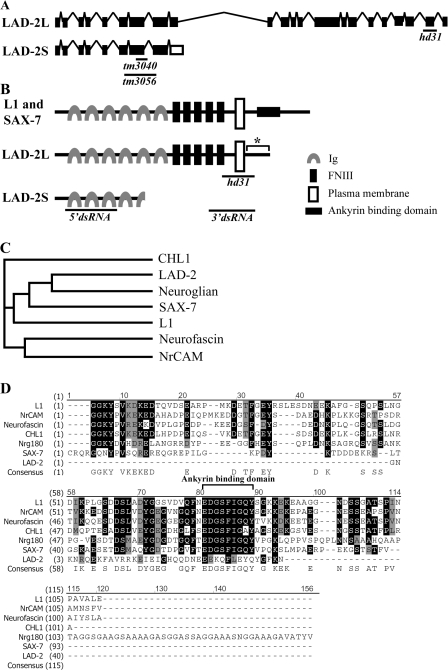

The Y54G2A.25 gene that is located on linkage group IV was previously reported to show homology to L1CAMs (Aurelio et al., 2002); we have named the gene lad-2. We performed both 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends and isolated two alternatively spliced lad-2 isoforms (Fig. 1 A). One isoform is predicted to encode a 56.3-kD protein containing four immunoglobulin repeats that is likely to be secreted extracellularly (LAD-2S, available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession no. EF584657), whereas the larger isoform is predicted to encode a 135.9-kD single-pass transmembrane protein (LAD-2L, available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession no.EF584655; Fig. 1 B). The LAD-2L extracellular domain contains six immunoglobulin domains and five fibronectin type III repeats, structural motifs that are also present in vertebrate L1CAMs as well as the C. elegans L1CAM LAD-1/SAX-7 (hereafter referred to as SAX-7; for review see Kenwrick et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2001). A phylogenetic analysis of the L1CAM extracellular domain suggests that LAD-2 is most closely related to the D. melanogaster L1CAM neuroglian (Fig. 1 C). In contrast to the extracellular domain, the LAD-2L cytoplasmic tail is completely divergent from SAX-7, neuroglian, and the vertebrate L1CAMs. The LAD-2L cytoplasmic tail contains only 40 amino acids and no known motifs such as the ankyrin-binding motif that is conserved in SAX-7 and vertebrate L1CAM cytoplasmic tails (Fig. 1, B and D). Hence, unlike SAX-7, we consider LAD-2 a noncanonical L1CAM.

Figure 1.

The lad-2 gene encodes a noncanonical L1CAM homologue in C. elegans. (A) Genomic organization of the alternatively spliced isoforms (not drawn to scale). The black boxes represent exons; the inverted Vs represent introns; and the open boxes represent an alternatively spliced exon. Black bars mark the end points of the hd31, tm3040, and tm3056 deletions. (B) A schematic of the protein structure of L1, SAX-7, and the LAD-2 isoforms LAD-2L and LAD-2S. Anti–LAD-2 antibodies were generated against the LAD-2 cytoplasmic tail (asterisk). Black bars mark the LAD-2 regions that are removed by the hd31 deletion or targeted by the dsRNAs in RNAi experiments. 5′ dsRNA targets the 5′ sequence that is shared by both LAD-2L and LAD-2S, whereas 3′ dsRNA targets the 3′ sequence that is unique to LAD-2L. (C) A phylogenetic tree of the L1CAM extracellular domains shows that LAD-2 is most closely related to the D. melanogaster neuroglian. (D) An amino acid sequence alignment of the L1CAM cytoplasmic tails reveals that LAD-2 has a divergent cytoplasmic tail.

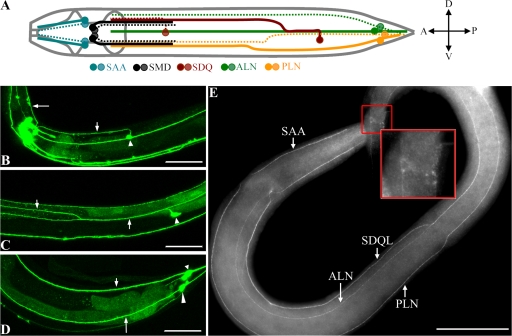

To determine LAD-2 expression and localization, we performed whole-mount immunostaining using two different affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies generated against the LAD-2 cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 1 B). Both antibodies, which recognize LAD-2L but not LAD-2S, revealed LAD-2 localization at the plasma membrane of 14 neurons and their associated axons (Fig. 2 E). These 14 neurons include the SAA, SMD, SDQ, PLN, and ALN neurons (Fig. 2 A), which is in agreement with the LAD-2 expression pattern inferred from a transcriptional GFP reporter (Fig. 2, B–D; Aurelio et al., 2002). LAD-2 staining is not detected in lad-2 mutant animals (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704178/DC1), which indicates antibody specificity. lad-2 expression, which can be detected when these neurons are born, persists throughout and after axon extension. Indeed, embryonically born ALN and SMD neurons (Sulston et al., 1983) as well as SDQL, SDQR, and PLN neurons, which are born in the L1 larval stage (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977), show lad-2 expression when they are born. This expression continues during axon migration, which is completed postembryonically, and persists in these neurons and their axons throughout adulthood.

Figure 2.

lad-2 is expressed in 14 neurons and associated axons. (A) A schematic depiction of lad-2–expressing neurons. Dark colored circles and solid lines represent cell bodies and axons on the left side of the animal. Light colored circles and dotted lines represent cell bodies and axons on the right side of the animal. (B–D) Confocal micrographs of adult wild-type animals expressing Plad-2∷gfp; left lateral view. (B) The SAA axon (long arrow), SDQR axon (short arrow), and SDQR cell body (arrowhead) are shown. (C) The arrows follow the anterior axon migration of the SDQL neuron (arrowhead). (D) The ALN neuron (small arrowhead) and axon (small arrow) and the PLN neuron (large arrowhead) and axon (long arrow) are shown. (E) A whole-mount immunostaining of a wild-type third-stage larva using the 1622 anti–LAD-2 antibody. Insets show LAD-2 localization on the surface of ALN and PLN cell bodies. Bars, 50 μm.

lad-2 is required for proper axon pathfinding

We performed a PCR-based ethyl methanesulfonate–induced mutagenesis screen and isolated a single mutation, hd31, in the lad-2 gene. We detected abnormal axon trajectories in the lad-2–expressing neurons SMD, PLN, SDQR, and SDQL; no defects were observed in non–lad-2–expressing neurons (unpublished data). These abnormalities can be categorized into guidance defects affecting (a) longitudinal migration of the SMD and PLN axons and (b) dorsal migration of the SDQR and SDQL axons.

In wild-type animals, SMD neurons, which are located near the nerve ring, extend axons posteriorly along the sublateral axon tracts (Figs. 2 A and 3 A). In lad-2 animals, we observed aberrant SMD axons that suggest general wanderings as well as ectopic dorsal or ventral turns (Fig. 3, B and J). PLN neurons, which are located in the tail of the animal, extend axons anteriorly into the nerve ring in wild-type animals (Figs. 2 A and 3 C). In lad-2 animals, PLN axons migrate posteriorly after an initial anterior extension (Fig. 3, D and J). In wild-type animals, SDQR and SDQL axons exhibit dorsal projections at specific points during their anterior migration along the lateral and sublateral axon tracts. The SDQR cell body sends out a single axon dorsally into the dorsal sublateral cord where it migrates anteriorly toward the nerve ring (Figs. 2 A and 3 E). In lad-2 animals, after a short migration along the sublateral cord, SDQR axons project ventrally to the ventral nerve cord (VNC), where they migrate along the VNC before terminating prematurely (Fig. 3, F and J). In wild-type animals, SDQL sends out a single axon dorsally into the lateral axon tract where it briefly extends anteriorly before turning dorsally again to join the dorsal sublateral cord, where it then migrates anteriorly toward the nerve ring (Figs. 2 A and 3 G). The SDQL axon in lad-2 animals exhibits abnormal ventral projections to the VNC, where it migrates along the VNC before terminating prematurely (Fig. 3 H). Approximately half of these neurons also exhibit bipolar axon outgrowths where a single process extends dorsally and prematurely terminates, whereas a second process extends ventrally and migrates anteriorly along the VNC before terminating prematurely (Fig. 3 I).

Figure 3.

lad-2 animals exhibit defective axon trajectories. (A–I) Confocal micrographs of wild-type and lad-2(hd31) axon trajectories of the SMD (A and B), PLN (C and D), SDQR (E and F), and SDQL (G, H, and I) neurons are shown. Arrows point to axons. Numbered arrows follow the sequential progression of axon extension from the cell body (arrowheads). Insets in G–I show schematics of wild-type (G) and lad-2(hd31) (H and I) SDQL migration. lad-2 animals (B) display aberrant ventral or dorsal (long arrow) turns and general wandering (short arrow) in SMD axons, abnormal ventral migration to the VNC of the SDQR (D) and SDQL axons (H), and a bipolar phenotype in the SDQL neuron (I) where one axon extends dorsally (long arrow) but terminates prematurely and a second axon extends ventrally (short arrow) into the VNC. SMDs were visualized with Pglr-1∷gfp (ventral view) and PLN, SDQR, and SDQL were visualized with Plad-2∷gfp (lateral view). Bar, 50 μm. (J) Quantitation of defective axons in wild-type, lad-2(hd31), lad-2(tm3056), and lad-2(tm3040) animals. These defects can be rescued by Plad-2∷lad-2 as seen in three independent transgenic lines, the first of which is shown. The quantitation of axon defects in the additional two transgenic lines are as follows: SMD, 5.1 ± 1.3% (line 2) and 6.4 ± 3.0% (line 3); PLN, 4.0 ± 2.1% (line 2) and 5.7 ± 2.9% (line 3); SDQR, 8.2 ± 1.5% (line 2) and 9.5 ± 2.0% (line 3); and SDQL, 9.4 ± 2.6% (line 2) and 8.6 ± 1.8% (line 3). Error bars show the standard error of the proportion of three sample sets, where in each set n = 93–112 (SMD); n = 103–135 (PLN); n = 79–108 (SDQR); and n = 76–128 (SDQL). **, P < 0.01 compared with wild-type animals.

Loss of sax-7 function was previously shown to result in abnormal axon trajectories and displaced neuronal cell bodies because of the inability of neurons to maintain their positions (Sasakura et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). To determine whether lad-2 also has a maintenance role, we chose to examine SMD neurons in lad-2 animals for an age-dependent increase in the number of animals showing axon abnormalities. In wild-type animals, extension and migration of the SMD axons occur at the L1 larval stage and continue through all the larval stages until adulthood. In lad-2 animals, we detected abnormal SMD axon trajectories as early as the L1 stage. In addition, the penetrance of this phenotype did not increase with the age of the animals (unpublished data). Moreover, unlike in sax-7 mutant animals, we did not detect displacement of the cell bodies of neurons exhibiting abnormal axons in lad-2 animals. Collectively, these results suggest the abnormal axon trajectories exhibited in lad-2 animals are a result of defective axon pathfinding rather than defective positional maintenance.

Axon guidance defects in lad-2 animals are caused by a loss of lad-2 function

The hd31 lesion is a 702-bp deletion that is predicted to result in an in-frame deletion of amino acids 1,080–1,162 removing part of the fifth FNIII repeat, the transmembrane domain, and half of the cytoplasmic tail of LAD-2L (Fig. 1, A and B). Because the hd31 mutation is located downstream of the LAD-2S coding region, it is not expected to affect LAD-2S (Fig. 1 A). Whole-mount antibody staining did not reveal LAD-2 staining in hd31 animals (Fig. S1). As hd31 deletes part of the cytoplasmic tail, it is conceivable that hd31 animals could produce a mutant form of LAD-2L that lacks the epitopes recognized by the LAD-2 antibodies. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of LAD-2L transcripts revealed equivalent levels of lad-2L transcripts between hd31 and wild-type animals (Fig. S2 B, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704178/DC1), which is suggestive of a stable pool of mutant lad-2L transcripts and possible mutant LAD-2L protein in lad-2 animals.

If a mutant form of LAD-2L were produced in hd31 animals, the protein would be predicted to be secreted because of the loss of the transmembrane domain and thus may act in a dominant fashion to cause the observed axon abnormalities. Several pieces of evidence argue against this possibility and instead support the hypothesis that hd31 acts as a loss-of-function allele. First, hd31 is a recessive mutation; hd31/+ animals do not exhibit an axon phenotype and are indistinguishable from wild-type animals (unpublished data). Second, the axon pathfinding defect in lad-2 animals can be rescued by transgenic expression of wild-type genomic lad-2 (Fig. 3 J). Third, we performed lad-2(RNAi) in the eri-1(mg366);lin-15(n744) animals, which are hypersensitive to RNAi in the nervous system (Sieburth et al., 2005). We used double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) that target either the 5′ or 3′ end of the lad-2 gene, the former of which would reduce both lad-2S and lad-2L transcripts (Fig. 1 B). Examination of these RNAi-treated animals revealed that lad-2(RNAi) phenocopies hd31 animals with similar penetrance, which is consistent with hd31 as a loss-of-function allele (Fig. S2 A). To further demonstrate that hd31 animals do not produce a mutant form of LAD-2L harboring some function, we similarly performed lad-2(RNAi) in lad-2(hd31) animals that are hypersensitive to RNAi (lad-2 eri-1;lin-15). lad-2(RNAi) in these animals phenocopied hd31 animals with similar penetrance and did not suppress or enhance lad-2(hd31) defects (Fig. S2 A). lad-2(RNAi) was successful in dramatically reducing the level of lad-2 transcripts as analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR of lad-2 transcripts in RNAi-treated animals (Fig. S2 B). Collectively, these results suggest that the axon defects exhibited by lad-2(hd31) animals are a result of the loss of lad-2 function and not a mutant protein with a dominant or novel function. The lad-2(RNAi) results also indicate that reduction of LAD-2S along with mutant LAD-2L does not result in either enhanced axon defects or additional phenotypes relative to those seen with reduction of only LAD-2L.

Subsequent to our phenotypic analysis of lad-2(hd31) and genetic study of lad-2 in relation to previously identified axon guidance pathways (see Figs. 5 and Figs.6), we obtained from the Japanese National Bioresource Project two additional lad-2 alleles, tm3040 and tm3056. The tm3056 mutation is a 1,064-bp out-of-frame deletion that is predicted to result in a premature stop after the second Ig motif (Fig. 1 A) and is likely a null allele of lad-2, removing both LAD-2L and LAD-2S isoforms. Consistent with this prediction, we did not detect any LAD-2 staining in whole-mount antibody staining of tm3056 animals with anti–LAD-2 antibodies (Fig. S1). lad-2(tm3056) animals exhibit similar axon defects with similar penetrance as lad-2(hd31) animals (Fig. 3 J). Collectively, these data strongly support our findings, which suggest that lad-2(hd31) is a null allele and that LAD-2S does not have functions independent of LAD-2L. In contrast to hd31 and tm3056, tm3040 acts as a hypomorphic allele. Indeed, low levels of LAD-2 immunostaining can be detected in lad-2(tm3040) animals (Fig. S1) despite the fact that the tm3040 mutation is a 327-bp deletion that is predicted to result in a premature stop after the second Ig motif (Fig. 1 A). Moreover, the penetrance of the axon defects exhibited by tm3040 animals is lower than those seen in lad-2(hd31) and lad-2(tm3056) (Fig. 3 J).

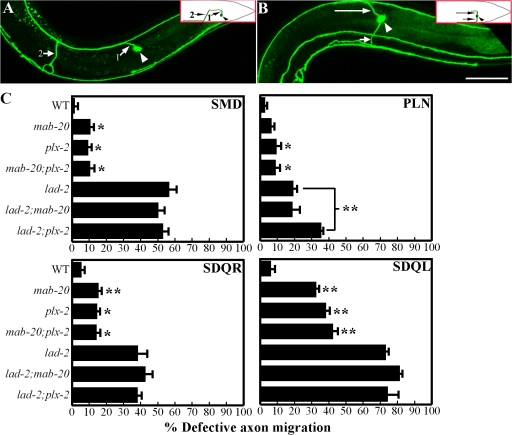

Figure 5.

mab-20 and plx-2 function in SDQL axon pathfinding. (A and B) Confocal micrographs of the SDQL neuron (arrowhead points to cell body) in mab-20(ev574) animals as visualized by Plad-2∷gfp showing abnormal ventral axon migration (A, numbered arrows show sequential progression of axon migration) and a bipolar phenotype (B) with one dorsal process (long arrow) and one ventral process (short arrow). Insets show a schematic of the corresponding phenotype. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Quantitation of axon migration defects. hd31 was the lad-2 allele used in this analysis. Interestingly, PLN defects are enhanced in lad-2;plx-2 animals (P < 0.01 compared with lad-2 animals). Error bars show standard error of the proportions of three sample sets where in each set n = 103–118 (SMD); n = 103–140 (PLN); n = 81–108 (SDQR); and n = 82–128 (SDQL). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 as compared with wild-type animals.

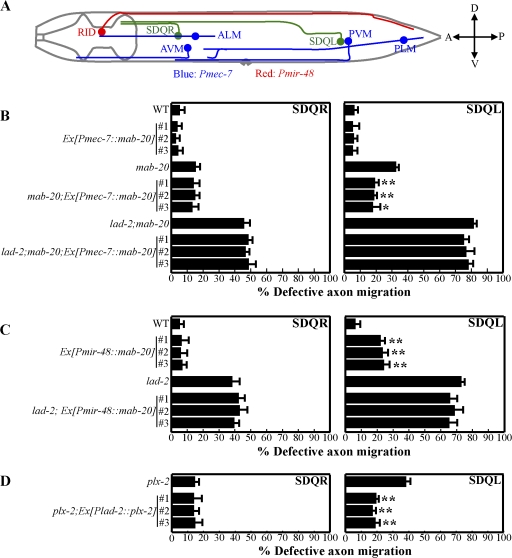

Figure 6.

The effects of ectopic mab-20 expression require lad-2 function. (A) A diagram showing the positions of SDQR and SDQL relative to the neurons and associated axons that ectopically express mab-20 as driven by Pmec-7 (AVM, ALM, PVM, and PLM neurons, blue) or Pmir-48 (RID neuron, red); lateral view. (B–D) Quantitation of SDQR and SDQL defects in animals of the respective genotypes. Error bars show standard error of the proportion of three sample sets where in each set n = 77–93 (SDQR) and n = 77–103 (SDQL). (B) Ectopic ventral expression of mab-20 with Pmec-7∷mab-20 can rescue SDQL defects in mab-20(ev574) but not lad-2(hd31);mab-20(ev574) animals. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 as compared with parent mab-20(ev574) animals. The percentage of those rescued was 41% (line 1), 43% (line 2), and 45% (line 3). (C) Ectopic dorsal expression of mab-20 with Pmir-48∷mab-20 induces the aberrant ventral migration of the SDQL axon in wild-type animals but does not enhance the SDQL defects already present in lad-2(hd31) animals. **, P < 0.01 as compared with parent wild-type animals. (D) plx-2 expression in the SDQL neuron with Plad-2∷plx-2, can partially rescue SDQL axon defects in plx-2(ev773) animals. **, P < 0.01 compared with parent plx-2(ev773) animals.

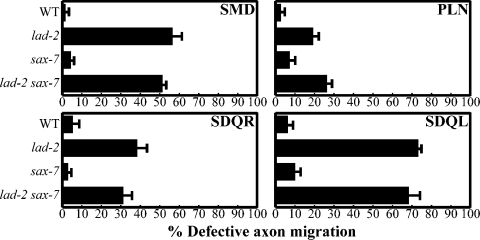

lad-2 function in axon guidance is sax-7 independent

Neurons that express lad-2 also express sax-7 (Chen et al., 2001; unpublished data). Because the axon defects in lad-2 animals are not fully penetrant, we asked whether sax-7 might function redundantly with lad-2. We determined that lad-2–expressing neurons in the genetic null sax-7(eq1) animals do not exhibit abnormal axon trajectories (Fig. 4). Moreover, the penetrance of the axon defects exhibited by lad-2 animals does not increase in lad-2 sax-7 double mutant animals (Fig. 4). These results indicate that sax-7 does not function in axon guidance in lad-2–expressing neurons. Similarly, lad-2 does not enhance sax-7 defects (unpublished data). Collectively, these results suggest that lad-2 and sax-7 do not have redundant functions.

Figure 4.

sax-7 does not participate in lad-2–related axon guidance. Quantitation of axon defects in lad-2(hd31), sax-7(eq1), and lad-2(hd31) sax-7(eq1) animals. Error bars indicate the standard error of proportion of three sample sets, where in each set, n = 103–118 (SMD); n = 99–133 (PLN); n = 84–108 (SDQR); and n = 85–128 (SDQL).

mab-20 and plx-2 participate in the same pathway in SDQL axon pathfinding

Guidance cues that direct axon migration include netrins, slits, and semaphorins, among others (for review see Chilton, 2006). We examined animals that are mutants for the unc-6 netrin, slt-1 slit, or mab-20 Sema2 genes for axon defects resembling those seen in lad-2 animals. Only mab-20 mutant animals exhibited lad-2–like axon defects. Specifically, SDQL axons in 41% of animals homozygous for the putative mab-20 null allele ev574 (Roy et al., 2000) displayed aberrant ventral projections into the VNC (Fig. 5, A and C) as well as bipolar axon outgrowths (Fig. 5 B).mab-20 animals also show modest SMD and SDQR axon defects (Fig. 5 C). These results indicate that, like lad-2, mab-20 participates in SMD, SDQR, and SDQL axon guidance.

Plexins act as semaphorin receptors in both vertebrates and invertebrates (for review see Kruger et al., 2005). Previous genetic analysis revealed that plx-2 functions in the same pathway as mab-20 in C. elegans epidermal morphogenesis (Ikegami et al., 2004). To determine if plx-2 also functions together with mab-20 in axon migration, we examined animals homozygous for the putative plx-2 null allele ev773 for axon guidance defects (Fig. 5 C). SDQL neurons in 40% of plx-2(ev773) animals exhibit similar guidance and bipolar axon phenotypes observed in mab-20 and lad-2 animals (Fig. 5 C), whereas SMD, PLN, and SDQR axons showed more modest defects. These phenotypes are not enhanced in mab-20;plx-2 double mutant animals (Fig. 5 C), which suggests that mab-20 and plx-2 function in the same pathway to direct axon migration.

Examination of smp-1(ev715) and smp-2(ev709) animals did not reveal axon defects in lad-2–expressing neurons, which suggests that the membrane-bound Sema1 proteins are not essential for SMD, SDQR, SDQL, and PLN axon guidance (unpublished data). The PLX-1 plexin functions as a receptor for SMP-1 and SMP-2 semaphorins in epidermal and vulval morphogenesis (Fujii et al., 2002; Dalpe et al., 2004, 2005). As expected, plx-1(ev724) animals also do not exhibit the described axon defects (unpublished data).

LAD-2 mediates axon guidance via MAB-20, which acts as a repulsive cue

The axon phenotypes shared by lad-2, mab-20, and plx-2 animals suggest that lad-2 may control SMD, SDQR, and SDQL axon guidance via the mab-20–plx-2 pathway. Consistent with this hypothesis, defects in these neurons are not enhanced in lad-2;mab-20 or lad-2;plx-2 double mutant animals (Fig. 5 C). Interestingly, PLN defects are enhanced in lad-2;plx-2 but not lad-2;mab-20 or mab-20;plx-2 animals (Fig. 5 C). These results imply that plx-2 may function in PLN axon guidance in a pathway that is distinct from lad-2 and independent of mab-20.

Semaphorins can function both as attractive and repulsive cues (Kruger et al., 2005). The broad embryonic expression of mab-20, as inferred by the Pmab-20∷gfp transcriptional reporter (Roy et al., 2000), does not reveal whether MAB-20 acts as an attractant or a repellent. Of the neurons described that display axon guidance defects in mab-20 animals, SDQL shows the most penetrant defects. We thus used SDQL as a system to determine how MAB-20 functions. If MAB-20 acts as a repulsive cue, the abnormal ventral trajectory of the SDQL axon in mab-20 animals would suggest a MAB-20 gradient in wild-type animals with higher ventral and lower dorsal levels of MAB-20. Ventral expression of mab-20 would thus be expected to rescue the defective ventral migration of the SDQL axon in mab-20 animals. To test this prediction, we used the mec-7 promoter (Kim et al., 1999) to express high, sustained levels of MAB-20 in the mechanosensory neurons in mab-20 animals. Of these neurons, PLM and PVM extend axons past and ventral to the SDQL cell body and axon (Fig. 6 A; White et al., 1986). Importantly, the postembryonically derived SDQL neuron is born after the embryonically derived PLM has completed axon extension so that ectopically expressed MAB-20 that is ventral to the SDQL neuron should be established by the time an SDQL is born and starts extending its axon. Consistent with the notion that MAB-20 acts as a repulsive cue to the SDQL axon, Pmec-7∷mab-20 expression partially rescues the SDQL axon guidance defect of mab-20 animals (Fig. 6 B). This ectopic MAB-20 expression in wild-type animals does not affect SDQL axon migration (Fig. 6 B).

To further test the hypothesis that MAB-20 acts as a repellent to SDQL, we assayed whether ectopic dorsal mab-20 expression would induce aberrant ventral migration of the SDQL axon. We used the mir-48 promoter (Li et al., 2005) to express sustained levels of mab-20 in the embryonically derived RID neuron, which extends a posteriorly directed axon dorsal to SDQL (Fig. 6 A). The mab-20 expression in the RID neuron and associated axon is expected to establish a dorsal mab-20 gradient by the time SDQL is born and starts extending its axon. Ectopic dorsal mab-20 expression in wild-type animals induced ventral migration defects in 17% of SDQL axons (Fig. 6 C). This result supports the hypothesis that MAB-20 acts as a repulsive cue to guide the SDQL axon to make dorsal turns at choice points to reach the dorsal sublateral nerve cord. The fact that SDQR axon migration was not affected by this ectopic MAB-20 expression is not too surprising, as SDQR defects are minimal in mab-20 animals.

If MAB-20 acts as a repellent, dorsal expression of mab-20 is predicted to enhance the SDQL phenotype in lad-2 animals unless lad-2 is required to mediate mab-20 function. Ectopic dorsal expression of mab-20 did not enhance SDQL defects in lad-2 animals (Fig. 6 C), which is consistent with our genetic data suggesting that lad-2 is required for mab-20–mediated SDQL axon pathfinding. As further support of lad-2 functioning together with mab-20 and plx-2, expression of PLX-2 in the SDQL neuron with the lad-2 promoter can partially rescue SDQL axon defects in plx-2 animals (Fig. 6 D), indicating that PLX-2 function is required in the same cell as LAD-2.

LAD-2 secures MAB-20/Sema2 coupling to PLX-2 plexin in a protein complex

L1 was previously shown to physically interact with neuropilin to regulate Sema3A function in mice (Castellani et al., 2000). C. elegans lacks a neuropilin. To address how LAD-2 mediates MAB-20 function in SDQL axon guidance, we assayed for biochemical interactions among LAD-2, MAB-20, and PLX-2. We cotransfected HEK293T cells with LAD-2 and either Myc∷MAB-20 or Myc∷PLX-2 and performed anti-Myc immunoprecipitations on the cell lysates. We detected the presence of LAD-2 in each immunoprecipitate by Western blot analysis using anti–LAD-2 antibodies (Fig. 7 A, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, LAD-2 was not detected in immunoprecipitates performed on cells cotransfected with a control Myc vector (Fig. 7 A, lane 3). To test that these LAD-2 interactions with MAB-20 and PLX-2 are not caused by nonspecific binding, we assayed for LAD-2 interaction with another axon guidance cue, SLT-1 slit, and the SAX-3 receptor (Huber et al., 2003). No LAD-2 was detected in the anti-Myc immunoprecipitates of cells coexpressing LAD-2 with either Myc∷SLT-1 or Myc∷SAX-3 (Fig. 7 B). Thus, we conclude that LAD-2 can interact with MAB-20 and PLX-2, although these results cannot distinguish whether LAD-2 binds MAB-20 and PLX-2 in a common complex.

Figure 7.

LAD-2 can enhance coupling of MAB-20 to PLX-2 as determined by Co-IP assays performed using anti-Myc antibodies. (A) LAD-2 interacts with MAB-20 and PLX-2 independently. Co-IP assays were performed on lysates of HEK293T cells coexpressing LAD-2 with Myc∷MAB-20 (lane 1), Myc∷PLX-2 (lane 2), and a control Myc vector (lane 3). The top two panels are Western blot analyses of the respective proteins in each lysate and the bottom panels are the Western blot of the Co-IP results. The asterisk points to a 170-kD band seen in lane 1 that may correspond to putative MAB-20 dimers. The bracketed bands in lane 2 are PLX-2 products; the lower band is a putative degradation product of PLX-2. (B) LAD-2 does not interact with SLT-1 or SAX-3. Co-IP assays were performed on cells coexpressing LAD-2 with Myc∷PLX-2 (lanes 1 and 3), Myc∷SLT-1 (lane 2), and Myc∷SAX-3 (lane 4). The top shows LAD-2 in each lysate as assayed by Western blotting; the bottom shows the Western blot analyses of the Co-IP results showing LAD-2 coimmunoprecipitates with PLX-2 (bracketed bands in lane 1 and 3) but not SLT-1 or SAX-3. (C) LAD-2 but not SAX-3 can enhance a weak interaction between mab-20 and PLX-2 as determined by Co-IP assays performed on cells coexpressing FLAG∷MAB-20 together with Myc∷PLX-2 and LAD-2 (lane 1), Myc∷PLX-2 and FLAG∷SAX-3 (lane 2), Myc∷PLX-2 (lane 3), or a control Myc vector (lane 4). Western blot analyses of the respective proteins in each lysate and Co-IP results are shown. Note that the low levels of FLAG∷MAB-20 CoIPs with Myc∷PLX-2 (lane 3) increases dramatically in the presence of LAD-2 (lane 1) but remains unchanged in the presence of SAX-3 (lane 2). (D) MAB-20 can form homodimers. Co-IP assays were performed on cells coexpressing FLAG∷MAB-20 with Myc∷MAB-20 (lane 1) and control Myc vector (lane 2). The top two panels are Western blot analyses of the respective proteins expressed in each lysate; the bottom shows Western blot analyses of the Co-IP results.

To determine whether MAB-20 and PLX-2 can interact, we performed similar anti-Myc immunoprecipitations on cells cotransfected with FLAG∷MAB-20 and Myc∷PLX-2. We observed low levels of FLAG∷MAB-20 in the anti-Myc immunoprecipitates, indicating that MAB-20 and PLX-2 can weakly interact (Fig. 7 C, lane 3). However, levels of FLAG∷MAB-20 dramatically increased in anti-Myc immunoprecipitates when LAD-2 was coexpressed in combination with FLAG∷MAB-20 and Myc∷PLX-2 (Fig. 7 C, lane 1), which indicates that LAD-2 enhances the coupling of MAB-20 and PLX-2. To further confirm the specificity of these LAD-2 interactions, we assayed for the ability of SAX-3, a transmembrane protein similar to LAD-2 in structure with multiple Ig and FNIII motifs (Zallen et al., 1998), to similarly enhance MAB-20–PLX-2 interactions. We did not detect increased levels of FLAG∷MAB-20 in anti-Myc immunoprecipitates of cells coexpressing FLAG∷SAX-3 with FLAG∷MAB-20 and Myc∷PLX-2 (Fig. 7 C, lane 2). These results suggest that LAD-2 secures coupling of MAB-20 and PLX-2 in a larger protein complex.

Homodimerization of many vertebrate semaphorins appear to be important for their function in axon repulsion (Klostermann et al., 1998; Koppel and Raper, 1998). In our Western blots of Myc∷MAB-20, we detected an additional faint band, the size of which was consistent with Myc∷MAB-20 dimers. To determine whether MAB-20 can form dimers, we performed anti-Myc immunoprecipitations on cells cotransfected with Myc∷MAB-20 and FLAG∷MAB-20. We detected FLAG∷MAB-20 in the immunoprecipitates by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody, which indicates that MAB-20 can oligomerize (Fig. 7 D, lane 1). This interaction is specific, as MAB-20∷FLAG was not immunoprecipitated in a similar pull-down assay with an anti-Myc antibody from cells expressing a control Myc vector (Fig. 7 D, lane 2).

Discussion

Significance of the restricted lad-2 expression

L1CAMs are highly conserved adhesion molecules that function in nervous system development. The C. elegans L1CAMs SAX-7 and LAD-2 have unique features in protein structure, expression, and function. SAX-7, which has the structural hallmarks of vertebrate L1CAMs, is widely expressed and required for maintaining neuronal positioning (Chen et al., 2001; Sasakura et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). In contrast, LAD-2 has a short and divergent cytoplasmic tail and is expressed in only 14 neurons.

It is striking that LAD-2 has such a restricted expression pattern. A common feature of these lad-2–expressing neurons is that their associated axons do not fasciculate with the major ventral and dorsal nerve cords. Instead, they migrate, either individually or together with a few other axons, along the “roads less traveled” by axons, i.e., the lateral midline or sublateral axon cords. Another common feature of these neurons is that axon outgrowth occurs postembryonically. The SDQL, SDQR, PLN, and ALN neurons are born postembryonically. The SMD neurons, although embryonically derived, have axons that extend and migrate throughout all larval stages. These characteristics of the lad-2–expressing neurons raise the possibility that LAD-2 may be required to keep these late-extending axons distinct and prevent them from merging with the main nerve cords. The functions of these neurons are not clear, although a recent study demonstrated that SDQL, SDQR, PLN, and ALN function in hyperoxia avoidance (A. Chang et al., 2006a). It is currently unknown whether hyperoxia avoidance is affected in lad-2 animals, which do not exhibit an obvious movement phenotype and are indistinguishable from wild-type animals apart from axon migration defects.

MAB-20/Sema2, which acts as a repellent, participates in axon guidance together with PLX-2

The inhibitory action of the Sema3 class of secreted semaphorins on axon outgrowth has been well demonstrated on multiple cultured vertebrate neurons. Yet, disruption of the Sema3 genes affects only a limited number of neuronal systems in vivo but revealed nonneuronal functions for Sema3 proteins that include vascular and heart development (for reviews see Nakamura et al., 2000;Kruger et al., 2005). Similarly, the C. elegans secreted semaphorin MAB-20/Sema2 appears to have a more prominent role in epidermal morphogenesis compared with axon guidance, which was described for certain motor neurons (Roy et al., 2000). Based on the mab-20 phenotypes, it was postulated that MAB-20 may function as a repellent. Our ectopic mab-20 expression experiments provide in vivo evidence that SDQL responds to MAB-20 as a repulsive cue or, alternatively, an inhibitor of an attractive cue with respect to axon pathfinding. These data also suggest that there may be a more localized ventral-to-dorsal MAB-20 gradient relative to the SDQL neuron that is not apparent according to the previously reported expression of mab-20∷gfp reporters (Roy et al., 2000).

Previous genetic studies revealed that plx-2 functions with mab-20 in epidermal morphogenesis of the male tail but a role in axon guidance had not been described (Ikegami et al., 2004). Our study shows that plx-2 does indeed function in axon pathfinding together with mab-20, which supports the idea that plexins function as semaphorin receptors. In contrast, plx-1 does not function with mab-20, which is consistent with a previous study showing that PLX-1 is the receptor for the membrane-bound Sema1 proteins SMP-1 and SMP-2 (Fujii et al., 2002).

That lad-2 functions with both mab-20 and plx-2 appears to be restricted to axon guidance. Examination of lad-2 animals did not reveal any morphogenetic defects in embryos or in the male tail (unpublished data), phenotypes that are prominent in mab-20 and plx-2 animals.

SDQL exhibits a bipolar axon phenotype in lad-2, mab-20, and plx-2 mutant animals

It is intriguing that the SDQL neuron can extend two axons that migrate in opposite directions in lad-2, mab-20, or plx-2 animals. This multipolar axon phenotype is similar to that seen in neurons overexpressing the actin regulatory pleckstrin homology domain protein MIG-10/lamellipodin in the absence of UNC-6 netrin and SLT-1 (Quinn et al., 2006). These studies point to guidance cues, such as slit and netrin, in orienting MIG-10 localization to the part of the neuron that will extend an axon (Adler et al., 2006; C. Chang et al., 2006; Quinn et al., 2006). Based on these MIG-10 studies, we hypothesize that in the absence of MAB-20 signaling, SDQL still responds to other guidance cues. However, the integration of these cues is deregulated, which results in a neuron that is in a “confused” state so that polarized MIG-10 localization is disrupted, leading to multiple processes growing out.

LAD-2 mediates axon guidance via mab-20–independent pathways

Consistent with the notion that SDQL axon guidance relies on multiple cues in addition to MAB-20, the SDQL defects in lad-2, mab-20, and plx-2 animals are not fully penetrant. Moreover, we hypothesize that LAD-2 also mediates SDQL axon guidance via a MAB-20–independent pathway, as the penetrance of the SDQL axon pathfinding defect in lad-2 mutant animals is significantly higher than in mab-20 and plx-2 mutants. In fact, our data indicates that LAD-2 mediates axon guidance via MAB-20–independent pathways in SMD, PLN, and SDQR. This raises the possibility that L1CAMs in vertebrates may also mediate axon guidance via semaphorin-independent pathways that may include L1 functioning as a direct receptor to a guidance cue or as a regulatory protein in the guidance pathways.

LAD-2 functions as a coreceptor to MAB-20/Sema2 to mediate axon repulsion

Our study provides in vivo evidence that an L1CAM in C. elegans participates in axon guidance by mediating the action of secreted semaphorins. In vertebrates, L1 is shown to bind neuropilin to mediate axon guidance via the secreted semaphorin Sema3A (Fig. 8; Castellani et al., 2004). Neuropilin is not conserved in D. melanogaster or C. elegans, which suggests that this coreceptor is a recent addition to the evolutionarily older semaphorin guidance system. Our biochemical data suggest that L1CAMs may be the original coreceptors for secreted semaphorins controlling axon navigation. Our results show that MAB-20 and PLX-2 can weakly interact, which is consistent with a recent published study that found that the ability for MAB-20 to bind to the surface of HEK293T cells requires PLX-2 expression in the cells (Nakao et al., 2007). Our results further show that the weak MAB-20–PLX-2 interaction is dramatically enhanced in the presence of LAD-2, which can form protein complexes independently with MAB-20 and PLX-2. These results suggest that LAD-2 functions as a MAB-20 coreceptor that anchors MAB-20 to PLX-2 to mediate MAB-20 signaling (Fig. 8). Consistent with this hypothesis, expression of PLX-2 in the SDQL neuron in the plx-2 animal can partially rescue the SDQL axon defects (Fig. 6 D), indicating that PLX-2 function is required in the same cell as LAD-2.

Figure 8.

A model of how LAD-2 functions as a MAB-20 coreceptor to mediate axon guidance. In C. elegans, mab-20/Sema2 acts as a diffusible, repulsive guidance cue in vivo to guide the dorsal migration of the SDQL axon. We hypothesize that LAD-2 binds MAB-20 homodimers and PLX-2 to a secure coupling of MAB-20 and PLX-2, which can interact weakly by themselves. This protein complex initiates a signal transduction cascade to induce actin cytoskeletal changes that lead to axon repulsion. L1CAMs are also implicated in semaphorin-dependent axon repulsion in vertebrates. However, neuropilin instead of L1 is the obligate semaphorin receptor that couples Sema3 to plexin. We hypothesize that in vertebrates, the functions of LAD-2 are executed by L1 and neuropilin, potentially providing an additional level of regulation. The depicted conserved motifs are as follows: Sema, Sema domain; Ig, Ig domain; FNIII, fibronectin type III repeat; C1, conserved region 1; C2, conserved region 2; CUB, complement binding domain.

It is intriguing that the LAD-2 cytoplasmic tail is not only divergent from that of canonical L1CAMs but is also short. Strikingly, the LAD-2 and neuropilin cytoplasmic tails are both 40 amino acids long, although they do not share significant sequence homology, which is consistent with neuropilin being a recently evolved protein. Underscoring this notion is the fact that the neuropilin cytoplasmic tail does not appear to be required in Sema3 signaling (for review see Bielenberg et al., 2006); the requirement for the LAD-2 cytoplasmic tail has yet to be determined. It is conceivable that the function of LAD-2 as an L1CAM and possible semaphorin receptor may have evolved in vertebrates into two separate proteins, neuropilin and L1, which may provide an additional layer of regulation required in navigating axon migration in a more complex nervous system.

This study has revealed that the role of L1CAM in axon guidance is conserved in both C. elegans and vertebrates. We have shown that LAD-2 mediates axon guidance via both semaphorin-dependent and -independent pathways. Additional studies to determine the semaphorin-independent pathways LAD-2 mediates or whether LAD-2S functions with LAD-2L in axon pathfinding will further reveal L1CAM mechanisms in the process of axon navigation. Loss of LAD-2 results in abnormal ventral migration of the SDQL axon, revealing a default guidance pathway that is concealed by semaphorin signaling. This phenotype is not fully penetrant in lad-2 animals, which indicates an additional pathway that compensates for the loss of MAB-20 signaling. Future studies will use the SDQL as a simple yet powerful genetic system to elucidate how the different guidance pathways crosstalk and dissect the process by which a neuron integrates the signals of different guidance cues to execute axon steering.

Materials and methods

Strains

C. elegans strains were grown on nematode growth medium plates at 20°C as described by Brenner (1974). N2 bristol served as the wild-type strain. The alleles used are listed by linkage groups as follows. LGI: mab-20(ev574) (Roy et al., 2000), smp-1(ev715), and smp-2(ev709) (Ginzburg et al., 2002); LGII: plx-2(ev773) (Ikegami et al., 2004) and muIs32(Pmec-7∷gfp) (Pujol et al., 2000); LGIII: rhIs4(Pglr-1∷gfp) (Lim et al., 1999); LGIV: lad-2(hd31), lad-2(tm3040), lad-2(tm3056), sax-7(eq1) (Wang et al., 2005), and eri-1(mg360) (Sieburth et al., 2005). lad-2(tm3040) and lad-2(tm3056) were backcrossed twice to remove secondary mutations. LGX: lin-15(n744) (Sieburth et al., 2005), slt-1(eh15) (Hao et al., 2001), unc-6(ev400) (Kim et al., 1999), and oxIs12(Punc-47∷gfp) (McIntire et al., 1997); and extrachromosomal GFP marker otEx331(Plad-2∷gfp; pha-1[+]) (Aurelio et al., 2002).

C. elegans expression vectors

Plad-2∷lad-2 (lad-2 genomic DNA, pLC358).

The lad-2 promoter (7.3 kb upstream of the start codon) and lad-2 genomic DNA (14 kb) were cloned from YAC Y54G2A (Coulson et al., 1988) in pWKS30 (Wang and Kushner, 1991) between SacII and ApaI.

Pmir-48∷mab-20 (pLC401).

mab-20 cDNA was amplified from E1SIIN.F (a gift from J. Culotti, Mt. Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada; Roy et al., 2000) and subcloned between the 1-kb promoter fragment of the mir-48 gene (Li et al., 2005) and the unc-54 3′ untranslated region in pBluescript backbone (Stratagene).

Pmec-7∷mab-20 (pLC402).

mab-20 cDNA with an intron inserted at the SmaI site was amplified from pLC401 and subcloned into pPD96.41 (a gift from A. Fire, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA) between KpnI and XhoI.

Plad-2∷plx-2 (pLC456).

plx-2 genomic DNA was cloned under the lad-2 promoter in pBluescript.

Mammalian cell expression vectors

Pcmv∷lad-2 (pLC424).

lad-2 cDNA was amplified from yk394b9 (a gift from Y. Kohara, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1(−) (Invitrogen) between BamHI and KpnI.

Pcmv∷FLAG∷mab-20 (pLC448).

mab-20 cDNA was amplified from E1SIIN.F and subcloned into p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1 (Sigma-Aldrich) between NotI and KpnI.

Pcmv∷FLAG∷sax-3 (pLC517).

sax-3 cDNA was cloned by RT-PCR from N2 total RNA and subcloned into p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1 KpnI and XbaI.

Pcmv∷ Myc∷mab-20 (pLC433).

mab-20 cDNA was amplified from E1SIIN.F and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/MycHis B (Invitrogen) between KpnI and XhoI.

Pcmv∷ Myc∷slt-1 (pLC505).

slt-1 cDNA was provided by C. Bargmann (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY; Hao et al., 2001) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Myc-His B between KpnI and BamHI.

Pcmv∷sax-3∷Myc (pLC518).

sax-3 cDNA was cloned by RT-PCR from N2 total RNA and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Myc-His B between KpnI and XbaI. The Myc-plx-2 expression vector was kindly provided by S. Takagi (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan; Fujii et al., 2002).

Isolation of lad-2(hd31)

An ethyl methanesulfonate–induced deletion library of animals (Jansen et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1999) was screened with the following lad-2–specific primers, resulting in the identification and isolation of the hd31 mutation: Y54_dx1 (GAAAGCTCAAAAACATGGTTCC) and Y54_dx2 (CACTTTTCACGACAGCTTTTTG). The isolated lad-2(hd31) strain was backcrossed eight times to remove secondary mutations.

Generation of LAD-2 antibodies

Guinea pigs were immunized with LAD-2 cytoplasmic tail expressed in bacteria in frame with glutathione S-transferase in a pGEX vector (GE Healthcare). Sera were preadsorbed over a glutathione S-transferase column (GE Healthcare) and affinity purified using an antigen fusion protein column. The resulting purified antibodies, 1622 and 1623, are specific to LAD-2L and effective in whole-mount staining (Figs. 2 E and S1). LAD-2 was not detected in whole animal lysate by Western blot analysis, probably because of low levels of LAD-2, which was present in only 14 cells. Indeed, these antibodies are effective on Western blots on HEK293T cells expressing LAD-2 (Fig. 7).

Whole-mount immunofluorescence

Animals were fixed and stained for indirect immunofluorescence using protocols adapted from Finney and Ruvkun (1990). Fixed animals were washed, incubated with 1622 or 1623 (1:100 dilution) at 4°C overnight, washed again, and incubated in secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti–guinea pig IgG; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, worms were mounted and examined using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Images were acquired using an AxioCam MRm and AxioVision 4.5 software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). The numerical aperture of the 63× and 100× objective lenses is 1.40 and 1.45, respectively.

lad-2 rescue and ectopic mab-20 expression

lad-2 rescue.

10 ng/μl pLC358 was injected with 70 ng/μl pRF4(rol-6[su1006]) into lad-2(hd31);otEx331 to generate transgenic array Ex(Plad-2∷lad-2;rol-6[su1006]).

Ectopic mab-20 expression.

10 ng/μl pLC402 was injected with 70 ng/μl pRF4(rol-6[su1006]) into otEx331, mab-20(ev574);otEx331, and lad-2(hd31);mab-20(ev574);otEx331 to generate Ex(Pmec-7∷mab-20;rol-6[su1006]). 10 ng/μl pLC401 was injected with 70 ng/μl pRF4(rol-6[su1006]) into otEx331 and lad-2(hd31);otEx331 to generate Ex(Pmir-48∷mab-20;rol-6[su1006]).

plx-2 rescue.

10 ng/μl pLC456 was injected with 70 ng/μl pRF4(rol-6[su1006]) into plx-2(ev773);otEx331 to generate Ex(Plad-2∷plx-2).

Phenotypic analysis of SMD, PLN, SDQR, and SDQL axons

Young adult animals were mounted on 2% agarose pads and scored for axon defects using fluorescence microscopy. SMD axonal migration was observed using the integrated Pglr-1∷gfp transgene rhIs4(III). The SMD axon was scored as a mutant if it failed to extend posteriorly in a direct path. PLN, SDQR, and SDQL axons were observed using the extrachromosomal Plad-2∷gfp transgene otEx331. The PLN axon was scored as a mutant if it migrated back toward the posterior end of the animal; the SDQR axon was scored as a mutant if it migrated ventrally; and the SDQL axon was scored as a mutant if it migrated ventrally or exhibited a bipolar phenotype. Three sample sets were analyzed for each genetic strain, where, on average, n = 100 for each sample set (see corresponding legends for specifics on n for each experiment). Statistical significance was calculated using the t test to compare the proportion of abnormalities between two genetic strains. Images of all the axon guidance phenotypes were taken with a confocal microscope (Eclipse E800; Nikon) and processed with the EZ-C1 viewer Gold 3.2 software (Nikon). The numerical aperture of the 40× objective lens is 1.30.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were maintained in DME (Mediatech, Inc.) with 10% newborn bovine serum. HEK293T cells were transfected with LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the standard procedure provided by the manufacturer. 40 h after transfection, cells were collected and washed with PBS.

Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays

200–500 μl of cell lysate was incubated with NETN buffer (20 mmol/liter Tris, pH 8, 100 mmol/liter NaCl, 1 mmol/liter EDTA, and 0.5% NP-40) containing a Myc antibody at 4°C for 4 h followed by an incubation with 20 μl of protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 2 h or overnight. The beads were washed three times with NETN lysis buffer.

Western blot analysis and reagents

Cell lysates were prepared in NETN buffer containing 1 mmol/liter NaF, 2.5 mmol/liter β-glycerophosphate, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in PBST (137 mmol/liter NaCl, 2.7 mmol/liter KCl, 10 mmol/liter Na2HPO4, 2 mmol/liter KH2PO4, and 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% milk for at least 40 min. Blots were probed with primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti–mouse or anti–rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Blots were then developed on film using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primary antibodies used included anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Myc (9E10; Covance), and anti-LAD-2 (1622).

lad-2 RNAi

dsRNA lad-2 RNA was generated by in vitro transcription (MEGAscript kit; Ambion) using yk394b9 as a template. 5′ dsRNA corresponds to 206–1,002 bp of lad-2L cDNA; 3′ dsRNA corresponds to 2,715–3,523 bp of lad-2L cDNA. dsRNAs were injected at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in young adult animals of respective genetic backgrounds and their progenies were scored.

Analyzing lad-2L transcripts

Total RNA was purified from animals of the following backgrounds: wild-type, lad-2(hd31), eri-1;lin-15;lad-2(RNAi5′), and eri-1 lad-2(hd31);lin-15;lad-2(RNAi5′). Reverse transcription was performed with 2 μg RNA using Superscript II reverse transcription (Invitrogen) using lad-2– and ama-1–specific primers. PCR was performed with the lad-2 primers LC523 and LC524, which flank the hd31 deletion, and the ama-1 primers A3 and B2 as a control (Spike et al., 2001). The sequence for LC523 is 5′-CAGAATGAGAAAAACGAAACC-3′ and the sequence for LC524 is 5′-CTCAAACAATGCACTTTATATTAATG-3′.

PCR products were gel purified and sequenced to confirm that they were lad-2L transcripts. To compare levels of lad-2L transcripts among wild-type, lad-2(hd31), and lad-2(RNAi) animals, RT-PCR was performed with the same primers with increasing cycle numbers (from 25 to 30 cycles) to evaluate the linearity of the reactions.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows LAD-2 staining with LAD-2 antibody 1622 in wild-type and lad-2 animals. Fig. S2 shows that RNAi-hypersensitive animals in an otherwise wild-type or lad-2(hd31) background that, when treated with lad-2(RNAi), display phenotypes of similar penetrance as untreated lad-2(hd31) animals. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704178/DC1.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Coulson, Yoji Kohara, Joseph Culotti, and Shin Takagi for various reagents, including cDNAs and strains; the Japanese National Bioresource Project for lad-2 alleles; the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center for strains used in this study; and the University of Minnesota C. elegans community for intellectual exchange. We thank John Yochem, Ann Rougvie, and David Greenstein in particular for experimental and editorial advice.

W. Zhang is supported by the University of Minnesota grant-in-aid award (20631). This work was supported in part by the Max Planck Society, a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant (within Sonderforschungsbereich 488) to H. Hutter, a Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant (RGPIN/312498-2006) to H. Hutter, and a National Institutes of Health grant (R01-NS045873) to L. Chen.

Abbreviations used in this paper: Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; LAD, L1-like adhesion gene; LICAM, L1 cell adhesion molecule; VNC, ventral nerve cord.

References

- Adler, C.E., R.D. Fetter, and C.I. Bargmann. 2006. UNC-6/Netrin induces neuronal asymmetry and defines the site of axon formation. Nat. Neurosci. 9:511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurelio, O., D.H. Hall, and O. Hobert. 2002. Immunoglobulin-domain proteins required for maintenance of ventral nerve cord organization. Science. 295:686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg, D.R., C.A. Pettaway, S. Takashima, and M. Klagsbrun. 2006. Neuropilins in neoplasms: expression, regulation, and function. Exp. Cell Res. 312:584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans.Genetics. 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, V., A. Chedotal, M. Schachner, C. Faivre-Sarrailh, and G. Rougon. 2000. Analysis of the L1-deficient mouse phenotype reveals cross-talk between Sema3A and L1 signaling pathways in axonal guidance. Neuron. 27:237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, V., J. Falk, and G. Rougon. 2004. Semaphorin3A-induced receptor endocytosis during axon guidance responses is mediated by L1 CAM. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26:89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.J., N. Chronis, D.S. Karow, M.A. Marletta, and C.I. Bargmann. 2006. A distributed chemosensory circuit for oxygen preference in C. elegans.PLoS Biol. 4:e274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C., C.E. Adler, M. Krause, S.G. Clark, F.B. Gertler, M. Tessier-Lavigne, and C.I. Bargmann. 2006. MIG-10/lamellipodin and AGE-1/PI3K promote axon guidance and outgrowth in response to slit and netrin. Curr. Biol. 16:854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., B. Ong, and V. Bennett. 2001. LAD-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans L1CAM homologue, participates in embryonic and gonadal morphogenesis and is a substrate for fibroblast growth factor receptor pathway–dependent phosphotyrosine-based signaling. J. Cell Biol. 154:841–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, J.K. 2006. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Dev. Biol. 292:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N.R., J.S. Taylor, L.B. Scott, R.W. Guillery, P. Soriano, and A.J. Furley. 1998. Errors in corticospinal axon guidance in mice lacking the neural cell adhesion molecule L1. Curr. Biol. 8:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, A., R.H. Waterston, J.E. Kiff, J.E. Sulston, and Y. Kohara. 1988. Genome linking with yeast artificial chromosomes. Nature. 335:184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpe, G., L.W. Zhang, H. Zheng, and J.G. Culotti. 2004. Conversion of cell movement responses to Semaphorin-1 and Plexin-1 from attraction to repulsion by lowered levels of specific RAC GTPases in C. elegans.Development. 131:2073–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpe, G., L. Brown, and J.G. Culotti. 2005. Vulva morphogenesis involves attraction of plexin1-expressing primordial vulva cells to semaphorin 1a sequentially expressed at the vulva midline. Development. 132:1387–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J., A. Bechara, R. Fiore, H. Nawabi, H. Zhou, C. Hoyo-Becerra, M. Bozon, G. Rougon, M. Grumet, A.W. Puschel, et al. 2005. Dual functional activity of semaphorin 3B is required for positioning the anterior commissure. Neuron. 48:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney, M., and G.B. Ruvkun. 1990. The unc-86 gene product couples cell lineage and cell identity in C.elegans.Cell. 63:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T., F. Nakao, Y. Shibata, G. Shioi, E. Kodama, H. Fujisawa, and S. Takagi. 2002. Caenorhabditis elegans PlexinA, PLX-1, interacts with transmembrane semaphorins and regulates epidermal morphogenesis. Development. 129:2053–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg, V.E., P.J. Roy, and J.G. Culotti. 2002. Semaphorin 1a and semaphorin 1b are required for correct epidermal cell positioning and adhesion during morphogenesis in C. elegans.Development. 129:2065–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.C., T.W. Yu, K. Fujisawa, J.G. Culotti, K. Gengyo-Ando, S. Mitani, G. Moulder, R. Barstead, M. Tessier-Lavigne, and C.I. Bargmann. 2001. C. elegans slit acts in midline, dorsal-ventral, and anterior-posterior guidance via the SAX-3/Robo receptor. Neuron. 32:25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, A.B., A.L. Kolodkin, D.D. Ginty, and J.F. Cloutier. 2003. Signaling at the growth cone: ligand-receptor complexes and the control of axon growth and guidance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26:509–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami, R., H. Zheng, S.H. Ong, and J. Culotti. 2004. Integration of semaphorin-2A/MAB-20, ephrin-4, and UNC-129 TGF-beta signaling pathways regulates sorting of distinct sensory rays in C. elegans.Dev. Cell. 6:383–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, G., E. Hazendonk, K.L. Thijssen, and R.H. Plasterk. 1997. Reverse genetics by chemical mutagenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans.Nat. Genet. 17:119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenwrick, S., A. Watkins, and E. De Angelis. 2000. Neural cell recognition molecule L1: relating biological complexity to human disease mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., X.C. Ren, E. Fox, and W.G. Wadsworth. 1999. SDQR migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans are controlled by multiple guidance cues and changing responses to netrin UNC-6. Development. 126:3881–3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann, A., M. Lohrum, R.H. Adams, and A.W. Puschel. 1998. The chemorepulsive activity of the axonal guidance signal semaphorin D requires dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7326–7331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppel, A.M., and J.A. Raper. 1998. Collapsin-1 covalently dimerizes, and dimerization is necessary for collapsing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15708–15713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, R.P., J. Aurandt, and K.L. Guan. 2005. Semaphorins command cells to move. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, M., M.W. Jones-Rhoades, N.C. Lau, D.P. Bartel, and A.E. Rougvie. 2005. Regulatory mutations of mir-48, a C. elegans let-7 family MicroRNA, cause developmental timing defects. Dev. Cell. 9:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.S., S. Mallapur, G. Kao, X.C. Ren, and W.G. Wadsworth. 1999. Netrin UNC-6 and the regulation of branching and extension of motoneuron axons from the ventral nerve cord of Caenorhabditis elegans.J. Neurosci. 19:7048–7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.X., J.M. Spoerke, E.L. Mulligan, J. Chen, B. Reardon, B. Westlund, L. Sun, K. Abel, B. Armstron, G. Hardiman, et al. 1999. High-throughput isolation of Caenorhabditis elegans deletion mutants. Genome Res. 9:859–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire, S.L., R.J. Reimer, K. Schuske, R.H. Edwards, and E.M. Jorgensen. 1997. Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature. 389:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, F., R.G. Kalb, and S.M. Strittmatter. 2000. Molecular basis of semaphorin-mediated axon guidance. J. Neurobiol. 44:219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, F., M.L. Hudson, M. Suzuki, Z. Peckler, R. Kurokawa, Z. Liu, K. Gengyo-Ando, A. Nukazuka, T. Fujii, F. Suto, et al. 2007. The PLEXIN PLX-2 and the ephrin EFN-4 have distinct roles in MAB-20/Semaphorin 2A signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans morphogenesis. Genetics. 176:1591–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, N., P. Torregrossa, J.J. Ewbank, and J.F. Brunet. 2000. The homeodomain protein CePHOX2/CEH-17 controls antero-posterior axonal growth in C. elegans.Development. 127:3361–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, C.C., D.S. Pfeil, E. Chen, E.L. Stovall, M.V. Harden, M.K. Gavin, W.C. Forrester, E.F. Ryder, M.C. Soto, and W.G. Wadsworth. 2006. UNC-6/netrin and SLT-1/slit guidance cues orient axon outgrowth mediated by MIG-10/RIAM/lamellipodin. Curr. Biol. 16:845–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.J., H. Zheng, C.E. Warren, and J.G. Culotti. 2000. mab-20 encodes Semaphorin-2a and is required to prevent ectopic cell contacts during epidermal morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans.Development. 127:755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakura, H., H. Inada, A. Kuhara, E. Fusaoka, D. Takemoto, K. Takeuchi, and I. Mori. 2005. Maintenance of neuronal positions in organized ganglia by SAX-7, a Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of L1. EMBO J. 24:1477–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, D., Q. Ch'ng, M. Dybbs, M. Tavazoie, S. Kennedy, D. Wang, D. Dupuy, J.F. Rual, D.E. Hill, M. Vidal, et al. 2005. Systematic analysis of genes required for synapse structure and function. Nature. 436:510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike, C.A., J.E. Shaw, and R.K. Herman. 2001. Analysis of sm-1, a gene that regulates the alternative splicing of unc-52 pre-mRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans.Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4985–4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J.E., and H.R. Horvitz. 1977. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans.Dev. Biol. 56:110–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J.E., E. Schierenberg, J.G. White, and J.N. Thomson. 1983. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.Dev. Biol. 100:64–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.F., and S.R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli.Gene. 100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., J. Kweon, S. Larson, and L. Chen. 2005. A role for the C. elegans L1CAM homologue lad-1/sax-7 in maintaining tissue attachment. Dev. Biol. 284:273–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J.G., E. Southgate, J.N. Thomson, and S. Brenner. 1986. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegansPhilosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 314:1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen, J.A., B.A. Yi, and C.I. Bargmann. 1998. The conserved immunoglobulin superfamily member SAX-3/Robo directs multiple aspects of axon guidance in C. elegans.Cell. 92:217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.