Abstract

Purpose

To examine whether compliance with underage sales laws by licensed retail establishments is related to underage use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, and alcohol use.

Methods

In 2005, alcohol purchase surveys were conducted at 403 off-premise licensed retail establishments in 43 Oregon school districts. A survey also was administered to 3,332 11th graders in the districts. Multi-level logistic regression analyses were used to examine relationships between the school district-level alcohol sales rate and students' use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, past-30-day alcohol use and heavy drinking.

Results

The school district-level alcohol sales rate was positively related to students' use of commercial alcohol sources and perceived alcohol availability, but was not directly associated with use of social alcohol sources and drinking behaviors. Additional analyses indicated stronger associations between drinking behaviors and use of social alcohol sources relative to other predictors. These analyses also provided support for an indirect association between the school district-level alcohol sales rate and alcohol use behaviors.

Conclusions

Compliance with underage alcohol sales laws by licensed retail establishments may affect underage alcohol use indirectly, through its effect on underage use of commercial alcohol sources and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol. However, use of social alcohol sources is more strongly related to underage drinking than use of commercial alcohol sources and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol.

Keywords: commercial alcohol availability, alcohol sources, alcohol use, underage youth

Understanding and reducing underage drinking remains a public health priority as rates of underage alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking (five or more consecutive drinks) have changed little in the past decade [1]. According to the 2005 Monitoring the Future survey of secondary school students, 17% of 8th graders, 33% of 10th graders, and 47% of 12th graders consumed alcohol at least once in the past 30 days, while 10%, 21%, and 28% of students in these respective grades reported heavy episodic drinking at least once in the past two weeks [2]. Results of the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicated that 50% of 18-20 year olds consumed any alcohol in the past month, while 37% reported binge or heavy episodic drinking at least once in the same period (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005 [3]. The annual social cost of underage drinking in the U.S. was conservatively estimated to be $61.9 billion in 2001 [4]. Reducing underage alcohol use in general, and heavy episodic drinking in particular, are both stated as Healthy People 2010 Objectives [5].

Reducing the availability of alcohol to youth from commercial sources is frequently recommended as one necessary component of a comprehensive strategy for preventing underage drinking [1]. Despite a national minimum drinking age of 21 years, research indicates that 30 to 70 percent of alcohol outlets may sell to underage buyers, depending in part on their geographic location [6-10]. A survey of youth in Minnesota and Wisconsin [11], for example, indicated that 3% of 9th graders, 9% of 12th graders, and 14% of 18-20 year olds obtained alcohol from a commercial source prior to their last drinking occasion. The survey also revealed that respondents thought it would be somewhat easier to obtain alcohol from grocery stores than from liquor stores or bars. A recent survey of 11th graders in Oregon revealed that 30% of drinkers obtained alcohol from a commercial source (e.g., grocery, convenience, or drug store) within the past 30 days [12].

Recognizing the potential influence of commercial availability of alcohol on underage drinking, many state alcohol regulatory and local law enforcement agencies now conduct decoy operations using minors or require responsible beverage service training. Each of these strategies is designed to increase compliance with underage sales laws and thereby reduce commercial alcohol availability to underage youth. However, little is known about the relationships between compliance with underage sales laws, the use of different alcohol sources by underage youth, the perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, and underage drinking.

Dent et al. [12] recently used survey data from a sample of 11th graders in Oregon to address this question. A school district-level measure of commercial alcohol availability was created by aggregating student survey responses to questions about how often they obtained alcohol from various commercial sources (e.g., grocery and convenience stores). The district-level measure of commercial alcohol availability was linked with student-level measures of past-30-day alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking, as well as their use of commercial and social alcohol sources. Results of multi-level analyses indicated a positive association between district-level commercial alcohol availability and student-level measures of past-30-day alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking. Additionally, the study suggested that a higher level of commercial alcohol availability strengthened the association between use of commercial alcohol sources and drinking behavior, while diminishing the association between use of social alcohol sources (e.g., friends > 21 years old) and drinking behavior.

Although the study by Dent et al. [12] suggests that commercial alcohol availability may affect underage drinking and its relationship to use of commercial versus social alcohol sources, their findings may overestimate the importance of commercial availability because of their reliance exclusively on student survey data to measure both availability and consumption. Moreover, Dent et al. did not directly examine the associations between district-level commercial alcohol availability, students' use of commercial and social alcohol sources, and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, leavening questions about the mechanisms through which commercial alcohol availability may affect underage drinking.

The present study addresses these limitations by using independent measures of underage alcohol sales compliance by licensed retail establishments that are based on results of alcohol purchase surveys conducted by underage-looking buyers. This study examines whether the school district-level underage alcohol sales rate is associated with students' self-reported use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, and drinking behaviors. We also examine the relative strength of association between alcohol use behaviors and student-level predictors (use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol), and possible indirect effects of the school district alcohol sales rate.

Methods

Student Survey Sample

Survey data were collected anonymously from 11th graders who participated in the Oregon Healthy Teens Survey (OHT)[13] in 43 Oregon school districts in the spring of 2005. These school districts are part of an ongoing study on the effects of community-based strategies that are designed to reduce underage drinking. The school districts were selected based on their prior and ongoing use of the OHT, their geographic representation of different Oregon regions, and their geographic separation to avoid contamination of control communities by prevention strategies in intervention communities.

The OHT survey was administered in schools that were part of a statewide random OHT sample or a CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey sample [13]. Surveys were administered by Oregon Research Institute staff or trained teachers to students in their classrooms and took one class period to complete. Of the 11th graders in the statewide OHT sample (N=5,415), two-thirds (N=3,598) were attending schools in the school districts selected for this study. The overall OHT response rate was 79.5%. Of 3,598 11th graders who participated in the OHT survey in the 43 districts, 3,332 (93%) provided complete data for all study variables. IRB approval for analysis of OHT data and other study activities (e.g., alcohol purchase surveys) was obtained prior to implementation of the study.

Survey Measures

Alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking

Students were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” Seven possible responses ranged from “0 days,” to “all 30 days”. Additionally, students were asked, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Seven possible responses ranged from “0 days,” to “20 or more days”. Because the majority of students did not report any alcohol use or heavy drinking, we created dichotomous measures indicating any past-30-day alcohol use or heavy drinking.

Use of commercial and social alcohol sources

Students were asked, “During the past 30 days, how many times did you get alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor) from each of the following (commercial) sources: (a) grocery stores, (b) convenience stores, (c) gas stations, (d) through the Internet, (e) liquor store, (f) bar, nightclub, or restaurant, and (social) sources: (g) friends 21 and older, (h) friends under 21, (i) from home without permission, (j) from a parent, (k) from a brother or sister, (l) by asking a stranger to buy it for you, (m) at a party?” Eight possible response options ranged from “None,” to “15 or more times”. Because the majority of students did not report any use of commercial sources or social sources, we created dichotomous measures indicating any past-30-day use of commercial or social alcohol sources.

Perceived ease of obtaining alcohol

Students were asked, “If you want to get some beer, wine, or hard liquor (for example, vodka, whiskey or gin), how easy would it be for you to get some?” Possible responses and corresponding values were “Very hard,” “Sort of hard,” “Sort of easy,” and “Very easy”. Because the majority of students thought alcohol would be very easy to obtain, we created a dichotomous variable to compare students who did and did not think alcohol would be very easy to obtain.

Demographics

Students reported their age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Because there was little variability in students' age and no association between age and either of the drinking behaviors, age was not included in the analyses. Race/ethnicity was treated as dichotomy (white vs. non-white) because the majority of students were white and the numbers of students in racial/ethnic minority groups were too small to obtain reliable estimates.

Alcohol Purchase Surveys

Purchase attempts were conducted from July through September 2005 at 403 licensed off-premise retail establishments (outlets) in the 43 school districts. These establishments were licensed to sell alcohol for consumption at some other location. Outlets were selected from the Oregon Liquor Control Commission's 2005 list of licensed off-premise retail alcohol outlets [14]. Purchase surveys were conducted in a census of all off-site outlets in districts with 20 or fewer outlets, and in a random sample of 20 outlets in districts with more than this number. Each outlet was visited once. Stores no longer in business or no longer selling alcohol were replaced with other randomly selected stores in districts with more than 20 outlets.

The decoy buyers were recruited through newspaper classified advertisements that sought young-appearing 21-year-olds. Photographs of potential buyers were reviewed by three people who work with youth and rated for apparent age. On the basis of these ratings three females and two males were retained as purchasers. The apparent age of the purchasers hired was estimated to be between 18 and 19 years in each case. Training for underage-looking buyers included instruction in the purchase survey protocol, role plays of purchase attempts, and practice attempts to purchase alcohol in non-study communities. The buyers were instructed not to try to look older or make any special efforts to convince outlet salesclerks to sell alcohol to them.

Purchase attempts were conducted on weekends and weekday evenings. Buyers dressed casually and carried money to purchase alcohol, but did not carry any identification. They attempted to purchase a six-pack of beer, and when asked for identification said they did not have it with them. They answered truthfully if clerks asked their age. On completion of the purchase attempt, the buyer returned to the car and completed the survey form, recording whether or not the purchase attempt was successful. Based on results of purchase attempts in each school district, an alcohol sales rate was calculated for each district.

Based on the distribution of the alcohol sales rate across the 43 school districts, we created three sales rate categories, representing relatively low (0-17%), medium (20-38%), and high (40-100%) sales rates.

Data Analysis

We first examined sample characteristics and unadjusted bivariate relationships between school district-level alcohol sales rate categories and measures of past-30-day alcohol use, heavy drinking, use of commercial and social alcohol sources, and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol. We then examined the use of different commercial and social alcohol sources among students who reported any past-30-day alcohol use or heavy episodic drinking, along with the perceived ease of obtaining alcohol among past-30-day drinkers and all students in the sample. Multi-level logistic regression analyses were then conducted using HLM version 6.02 to examine possible main or direct effects of the district-level alcohol sales rate on students' use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, and past-30-day alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking. These models included students' gender and race/ethnicity and the district-level alcohol sales rate as predictors. We also conducted multi-level logistic regression analyses to examine the relative strength of association between alcohol use behaviors, use of commercial and social alcohol sources, and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol. These analyses also allowed us to assess possible indirect effects of the district-level alcohol sales rate on alcohol use behaviors as indicated by reductions in associations (odds ratios) observed in main effects models. HLM provided adjustment for clustering of students within school districts and random variation in intercepts across districts [15].

Results

Sample characteristics are provided in Table 1 by category of the school district alcohol sales rate. As noted previously, the majority of students did not report any use of commercial or social alcohol sources, alcohol use, or heavy drinking in the past 30 days. However, over half of the students thought alcohol would be very easy to obtain. Past-30-day use of commercial alcohol sources was more prevalent among districts in the middle (20-38%) category than districts in the lowest (0-17%) and highest (40-100%) categories. The prevalence of using social alcohol sources and the percentage of students who thought alcohol is very easy to obtain were significantly higher in the 40-100% sales rate category relative to the lowest (0-17%) category. No significant differences in rates of past-30-day alcohol use and heavy drinking were observed across the three district alcohol sales rate categories, though prevalence rates for these behaviors were somewhat higher in the 20-38% and 40-100% categories relative to the 0-17% category.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (%) by School District-Level Alcohol Sales Rate Category

| Variable | Total Sample (N=3332) |

School District Alcohol Sales Rate1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-17% (n=1083) |

20-38% (n=1128) |

40-100% (n=1121) |

||

| Male | 48.2 | 48.7 | 50.4a | 45.6 |

| White | 84.5 | 84.2 | 86.2 | 83.0 |

| Any use of commercial alcohol sources, past 30 days |

10.7 | 10.0 | 12.6a,b | 9.5 |

| Any use of social alcohol sources, past 30 days |

40.6 | 37.8 | 41.9 | 42.1c |

| Alcohol is very easy to obtain | 53.1 | 51.4 | 51.9 | 55.9c |

| Any alcohol use, past 30 days | 44.4 | 42.0 | 45.5 | 45.8 |

| Any heavy drinking, past 30 days | 29.9 | 28.1 | 30.6 | 31.0 |

The average district alcohol sales rate was 33%; 13 districts had a sales rate in the 0-17% range, while 15 had a sales rate in the 20-38% range and 15 had a sales rate in the 40-100% range.

p<.05 for difference between middle (20-38%) and highest (40-100%) sales rate categories.

p<.05 for difference between lowest (0-17%) and middle (20-38%) sales rate categories.

p<.05 for difference between lowest (0-17%) and highest (40-100%) sales rate categories.

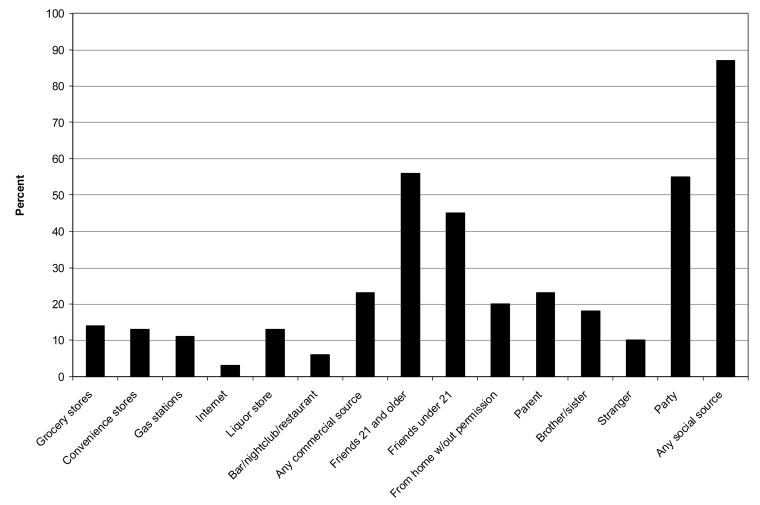

Figure 1 indicates that 23% of past-30-day drinkers obtained alcohol from at least one commercial source, while 87% obtained alcohol from at least one social source. The most common commercial alcohol sources were grocery stores, convenience stores, gas stations, and liquor stores. The most common social alcohol sources were friends over the age of 21, parties, and friends under the age of 21. The majority of past-30-day drinkers (63%) thought that alcohol would be very easy to get if they wanted some, as did 53% of students in the total sample.

Figure1.

Percentage of Student Drinkers Who Obtained Alcohol From Commercial and Social Sources at Least Once in the Past 30 Days.

Table 2 includes results of multi-level logistic regression analyses to assess the possible main or direct effects of school district-level commercial alcohol availability on student's use of commercial and social alcohol sources, perceived ease of obtaining alcohol, and past-30-day alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking. Districts in the lowest (0-17%) sales rate category served as the referent group for these analyses. Controlling for student-level gender and race/ethnicity, the middle (20-38%) district alcohol sales rate category was positively associated with any past-30-day use of commercial alcohol sources (odds ratio [OR]=1.63, p<.01), while the highest (40-100%) alcohol sales rate category was not (OR=1.21, p>.05). Neither the middle nor the highest district alcohol sales rate category was significantly associated with past-30-day use of social alcohol sources at the .05 level. The highest district alcohol sales rate category was positively associated with the perception that alcohol is very easy to obtain (OR=1.22, p<.05), but no association with perceived alcohol availability was observed for the middle district alcohol sales rate category. Past-30-day alcohol use and heavy drinking also were not associated with either the middle or the highest district alcohol sales rate categories at the .05 level.

Table 2.

Results of Multi-Level Analyses to Assess Main Effects of the School District-Level Alcohol Sales Rate, Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

| Predictor | Any use of commercial sources |

Any use of social sources |

Alcohol is very easy to obtain |

Any alcohol use, past 30 days |

Any heavy drinking, past 30 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student level | |||||

| Male | 1.49 (1.19, 1.87)a | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.10) | 1.06 (0.93, 1.22) | 1.38 (1.18, 1.60)a |

| White | 0.59 (0.45, 0.77) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) | 0.86 (0.71, 1.04) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.29) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) |

| School district level1 | |||||

| 40-100% alcohol sales rate | 1.21 (0.87, 1.69) | 1.16 (0.91, 1.48) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45)b | 1.15 (0.89, 1.48) | 1.14 (0.85, 1.52) |

| 20-38% alcohol sales rate | 1.63 (1.18, 2.27)a | 1.21 (0.95, 1.55) | 1.02 (0.85, 1.22) | 1.20 (0.93, 1.54) | 1.19 (0.89, 1.59) |

Districts in the lowest alcohol sales rate category (0-17%) are the referent group.

p<.01

p<.05

Additional multi-level logistic regression analyses were conducted to compare the relative strength of association between alcohol use behaviors and student-level predictors, and possible indirect effects of the district-level alcohol sales rate. As indicated in Table 3, use of commercial and social alcohol sources were both positively related to past-30-day alcohol use and heavy drinking, but the ORs for use of social alcohol sources were considerably larger than ORs for use of commercial alcohol sources. The perception that alcohol is easy to obtain also was positively associated with past-30-day alcohol use, but was only marginally associated with past-30-day heavy drinking at the .05 level. ORs for the middle and highest district alcohol sales rate categories were substantially reduced from ORs observed in main effects models (Table 2), suggesting possible indirect effects of school district-level commercial alcohol availability on alcohol use behaviors.

Table 3.

Results of Multi-Level Analyses to Assess Relative Effects of Predictors on Alcohol Use Behaviors, Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

| Predictor | Alcohol use, past 30 days |

Heavy drinking, past 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Student level | ||

| Male | 1.64 (1.26, 2.12)a | 1.98 (1.60, 2.46)a |

| White | 1.26 (0.87, 1.82) | 1.21 (0.89, 1.64) |

| Use of commercial alcohol sources | 5.93 (2.99, 11.74)a | 5.78 (4.03, 8.30)a |

| Use of social alcohol sources | 139.95 (104.47, 187.49)a | 35.33 (27.41, 45.54)a |

| Alcohol is very easy to obtain | 1.34 (1.04, 1.73)b | 1.23 (1.00, 1.53)b |

| School district level1 | ||

| 40-100% alcohol sales rate | 1.03 (0.69, 1.53) | 1.02 (0.72, 1.45) |

| 20-38% alcohol sales rate | 1.01 (0.68, 1.52) | 0.97 (0.68, 1.39) |

Districts in the lowest alcohol sales rate category (0-17%) are the referent group.

p<.001

p≤.05

Discussion

Although reducing the commercial availability of alcohol to underage youth is considered an important component of a comprehensive prevention strategy [1,16], research on the relationship between commercial alcohol availability and underage drinking is limited. In contrast to previous studies [12], our findings indicate that commercial alcohol availability is not directly related to underage alcohol use or heavy episodic drinking, but may have an indirect effect through underage use of commercial alcohol sources and the perception that alcohol is very easy to obtain. Our findings also indicated much greater reliance by students on social alcohol sources and strong positive associations between use of social alcohol sources and past-30-day drinking behaviors.

The differences in findings between our study and previous research may result, in part, from differences in methodology. In particular, the findings from previous studies may have been confounded because they used single sources of data (e.g., student surveys) for both commercial availability and consumption. Our measure for school district-level commercial alcohol availability was based on alcohol purchase surveys at local off-premise outlets, whereas earlier studies typically have created commercial availability measures by aggregating student responses to survey questions about use of commercial alcohol sources. As a result, these studies may over-estimate the effect of commercial alcohol availability on student-level drinking as both measures are based on data from the same individuals.

Findings of this study should be considered in light of several limitations. School districts in our sample may not be representative of all school districts in Oregon or the U.S., though the overall alcohol sales rate (33%) was comparable to the statewide alcohol purchase sales rate obtained by the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (29%) in 2004 [14]. Similarly, the 11th graders in the study sample may not be representative of all 11th graders or high school students in Oregon or the U.S. The cross-sectional design of the study limits our ability to make causal inferences about observed relationships between study variables. It is just as plausible that students' alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking are predictive of their use of commercial and social alcohol sources and perceived ease of obtaining alcohol. Finally, although the surveys were anonymous, the students' responses may have been subject to possible recall and social desirability biases, which may have led to under- or over-estimation of levels of alcohol use and use of different alcohol sources.

This study points to the challenge of reducing underage youths' access to alcohol, given the many potential sources at their disposal (Figure 1). Our findings suggest that reducing the availability of alcohol from commercial sources alone may have only a modest influence on underage drinking, as social sources of alcohol appear to be much more important than commercial sources. As indicated in Table 3, use of social alcohol sources was more strongly related to past-30-day alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking that use of commercial sources. This is not surprising, given the stronger reliance of underage youth on social sources of alcohol (87%) versus commercial sources (23%). Although some policy and law enforcement strategies are recommended for reducing alcohol availability from social sources (e.g., minor in possession and social host liability laws, controlled party dispersal), research on the effectiveness of these strategies is very limited. Research is therefore needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies, both singly and in combination, to reduce alcohol availability from both commercial and social sources. The ongoing study in Oregon school districts is designed for that purpose.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA Grant No. R01 AA014958).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine . Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2006. (NIH Publication No. 06-5882). 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2005. (NSDUH Series H-28, DHHS Publication No. SMA 05-4062). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller TR, Levy DT, Spicer RS, Taylor DM. Societal costs of underage drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:519–528. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster JL, McGovern PG, Wagenaar AC, Wolfson M, Perry CL, Anstine PS. The ability of young people to purchase alcohol without age identification in northeastern Minnesota, USA. Addiction. 1994;89:699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster JL, Murray DM, Wolfson M, Wagenaar AC. Commercial availability of alcohol to young people: Results of alcohol purchase attempts. Prev Med. 1995;24:342–347. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grube JW. Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: Results from a community trial. Addiction. 1997;92(suppl 2):S251–S260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preusser DF, Williams AF. Sales of alcohol to underage purchasers in three New York counties and Washington DC. J Public Health Policy. 1992;13:306–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz RH, Farrow JA, Banks B, Giesel AE. Use of false ID cards and other deceptive methods to purchase alcoholic beverages during high school. J Addict Dis. 1998;17:25–34. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Murray DM, Short BJ, Wolfson M, Jones-Webb R. Sources of alcohol for underage drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:325–333. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dent CW, Grube JW, Biglan A. Community level alcohol availability and enforcement of possession laws as predictors of youth drinking. Prev Med. 2005;60:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oregon Department of Human Services. Center for Health Statistics . Oregon Healthy Teens – Youth Surveys. Salem, Oregon: 2005. http://www.dhs.state.or.us/dhs/ph/chs/youthsurvey/ohteens/2005/methods.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oregon Liquor Control Commission . 2004 underage sales compliance check data were provided to the investigators by the Oregon Liquor Control Commission. Milwaukie, Oregon: 2005. http://www.olcc.state.or.us/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention . Regulatory Strategies for Reducing Youth Access to Alcohol: Best Practices. Center for Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws; Calverton, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]