Abstract

Many researchers are currently studying the distribution of genetic variations among diverse groups, with particular interest in explaining racial/ethnic health disparities. However, the use of racial/ethnic categories as variables in biological research is controversial. Just how racial/ethnic categories are conceptualized, operationalized, and interpreted is a key consideration in determining the legitimacy of their use, but has received little attention. We conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with 30 human genetics scientists from the US and Canada who use racial/ethnic variables in their research. They discussed the types of classifications they use, the criteria upon which they are based, and their methods for classifying individual samples and subjects. We found definitions of racial/ethnic variables were often lacking or unclear, the specific categories they used were inconsistent and context specific, and classification practices were often implicit and unexamined. We conclude that such conceptual and practical problems are inherent to routinely used racial/ethnic categories themselves, and that they lack sufficient rigor to be used as key variables in biological research. It is our position that it is unacceptable to persist in the constructing of scientific arguments based on these highly ambiguous variables.

Keywords: Race, Ethnic Groups, Human Genetics, Health Disparities, Bioethics, USA, Canada

Fueled in part by intense interest in understanding and controlling health disparities among racial/ethnic1 minority groups, one of the key goals of current human genetics research is to identify genetic variations that affect common diseases, and to develop therapeutic interventions that target those variations. A great many researchers are studying the distribution of genetic variations among diverse groups in order to understand underlying disease susceptibility and treatment response. Commonly, these efforts focus on racial and ethnic groupings, resurrecting a long-standing controversy over the use of such groupings in scientific research.

Some researchers argue that race/ethnicity provides rough, but valuable, information about genetic ancestry and thereby information about disease prevalence and risk. They argue that, until our understanding of the distribution of genetic variants is more refined, race/ethnicity provides a useful proxy for important variations.(Burchard, Ziv, Coyle, Gomez, Tang, Karter et al. 2003; Mountain & Risch, 2004; Jorde & Wooding, 2004; Collins, 2004)

Other researchers maintain that “race” is a social construct without biological basis, pointing out that there is more genetic difference within groups than between them. They argue that the use of race/ethnicity in medical research has limited utility, and produces arbitrary results, which reify a typological version of human variation that obscures social explanations and responsibility for health disparities (Goodman, 2000; Keita, Kittles, Royal, Bonney, Furbert-Harris, Dunston et al. 2004; Braun, 2004). In this view, using racial/ethnic groupings in genetic research is a questionable undertaking, without clear scientific legitimacy, which should be abandoned or approached with great caution.

How is it that such disparate views might exist amongst some of the most renowned researchers of an otherwise highly systematic and rigorous field of study? In part this may be because these arguments rely almost exclusively on abstract considerations and declarations, with each side revisiting the polemics already extant in the debate. In this paper, we attempt to move beyond these previous discussions, by considering the on-the-ground concepts and practices being employed by a group of researchers who are using these variables. We will consider the depth of the problem of using racial/ethnic categories as variables in genetics research, which we argue is rooted in the highly problematic nature of the categories themselves. Based on interviews we conducted with a group of human genetics researchers, we will examine how these researchers conceptualize, operationalize and interpret racial/ethnic differences, and the principles of classification they apply. We will argue that while the researchers’ use of commonplace racial/ethnic terminology may appear to be a matter-of-fact way of classifying objective identities, these categories are actually highly amorphous, promoting an illusion of coherence, where coherence is in fact quite suspect.

THE CONTROVERSY

Contemporary racial typologies remain relatively intact from their inception by taxonomists at the time of the major European colonial expansion, over 200 years ago, roughly corresponding to Linnaeus’ 1758 schema: Americanus rubescus (red), Europaeus albus (white), Asiaticus luridus (yellow), and Afer niger (black) (cited in: Lee, Mountain & Koenig, 2001). While the specific criteria for best classifying individuals has been a topic of much consternation, the notion that people can be placed into relatively discrete ancestral groups that have distinctive physical and cultural characteristics is an old one (Stocking, 1994).

Indeed, in the U.S. today, race is generally understood in terms of categories thought to correspond with the major continents: Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Many researchers have reported genetic variations which correspond to these groupings (Cavalli-Sforza, 1998; Jorde & Wooding, 2004; Jorgenson, Tang, Gadde, Province, Leppert, Kardia et al. 2005; Tang, Quertermous, Rodriquez, Kardia, Xiaofeng Z., Brown et al. 2005). This is attributed to past genetic isolation between continents: mountains, deserts, and oceans impeded human movement, resulting in relatively endogamous mating patterns. For this reason, it is argued, genetic differences between people in the U.S. correspond to geographic ancestry. Most of the evidence for these claims has been based on selective sampling from different continents, and the relationship to the U.S. population has been merely extrapolated. However, several researchers have recently reported that select genetic markers also cluster with the self-identified race of people in the U.S. (Risch, Burchard, Ziv & Tang, 2002; Burchard et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2005; Bamshad, 2005).

This model has come under severe criticism as misleading and based on misinterpretations and over-generalizations (Goodman, 2000; Brown & Armelagos, 2001; Braun, 2002; Kittles & Weiss, 2003; Dressler, Oths & Gravlee, 2005). Since Lewontin’s (1972) seminal work three decades ago, reporting that genetic diversity of traits such as blood groups and antigens is greatest between individuals and least between groups, it has become widely accepted that there is by far more genetic diversity within racial groups than between them (American Anthropological Association, 1997; Brown & Armelagos, 2001). Critics have argued that researchers who find genetic variation correlating well with race/ethnicity do so primarily as an artifact of their sampling procedures, which rely on sampling groups that are widely separated geographically and are relatively isolated. When samples are taken from individuals more evenly distributed geographically, differences are far less pronounced, and tend to be clinal, that is showing gradual variation across adjacent geographic areas (Race Ethnicity and Genetics Working Group, 2005).

Beyond the controversy over the correct design and interpretation of genetic variation studies, an urgent debate has emerged over the potential values and dangers of the growing body of research seeking to document genetic differences between racial/ethnic groups. Easily one of the most controversial and widely criticized genetics science undertakings in recent years has been the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP). First proposed in 1991 by Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues (Cavalli-Sforza, Wilson, Cantor, Cook-Deegan & King, 1991), the HGDP set out to collect DNA samples from hundreds of geographically isolated and culturally unique populations throughout the world, with the aim of documenting and preserving human genetic diversity. It has provoked a vociferous debate, resulting in a withdrawal of federal support, which all but ended the project (Resnik, 1999; Reardon, 2004; Cavalli-Sforza, 2005).

Still, interest in documenting human genetic variation persists, and in 2002, informed by the criticism of the HGDP, the International HapMap project was launched. Heavily funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and an international group of other public and private funders, the project sets out to chart genetic differences among individuals and to ultimately uncover genetic contributors to common diseases. The groups from whom genetic data are being gathered, “Yoruba of Nigeria, Japanese, Han Chinese and U.S. Residents,” are described in the official communications of the project as “populations with African, Asian, and European ancestry” (International HapMap Project, 2005). The protocols for the HapMap have been quite carefully designed to avoid the ethical criticisms that the HGDP provoked. They have included a diligent effort to gain the informed consent of the targeted communities, and to avoid racialized terms in reporting findings, referring instead to specific geographic areas or groups.

Even so, deep concern persists regarding research designed to document genetic differences between racial/ethnic groups, even when labeled “geographic populations” or “ancestral groups” (Gannett, 2001). For example, four prominent research journals have recently published special issues devoted to the controversy, (Nature Genetics, November 2004; American Psychologist, January 2005; American Journal of Public Health, December 2005; and Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, Fall 2006.). These include articles that review the state of the science of research on genes, race and health; consider some of the ethical and social implications of using concepts of race in such research; and suggest ways of avoiding potential pitfalls in using race and ethnicity in studying genetic diversity. (For example see: Rotimi, 2004; Keita et al., 2004; Ossorio & Duster, 2005; Krieger, 2005; Lee, 2005; Shields, Fortun, Hammonds, King, Lerman, Rapp et al. 2005; Cho, 2006).

Race and ethnicity are widely recognized as highly fluid, social and cultural categories whose biological basis is tenuous at best, but nonetheless are valued as providing a fair indication of continental ancestry. Despite this controversy, race and ethnicity continue to be routinely used as variables in genetics research (Jones, LaVeist & Lilli-Blanton, 1991; Sankar, Cho, Condit, Hunt, Koenig, Marshall et al. 2004; Comstock, Castillo & Lindsay, 2004).

While debate over the pros and cons of using race in genetics research is becoming a familiar theme in the health literature, most often these discussions are based on abstract arguments. Those defending the practice for the most part are geneticists and physicians, who extrapolate very particularistic data to rather ambitious proclamations about broad geographic distributions. Criticisms of using race in genetic research have been generated by scholars from a broad cross-section of disciplines, including anthropologists, sociologists, public health professionals, epidemiologists, lawyers, ethicists, and a few geneticists and physicians, as well. These arguments have been almost exclusively editorial commentaries, or based on critical literature review. Analysis of empirical evidence of the actual concepts and practices at play are rare. (For notable exceptions see: McCann-Mortimer, Augoustinos & LeCouteur, 2004; Outram & Ellison, 2006.) In this paper, we present such an analysis, based on interviews with 30 genetic scientists. We found that these researchers routinely employ racial/ethnic classifications in their work in the absence of an explicit and systematic basis for their classification, relying instead on unexamined, broadly-held typological beliefs about human populations, resulting in classifications of questionable scientific merit.

THE STUDY

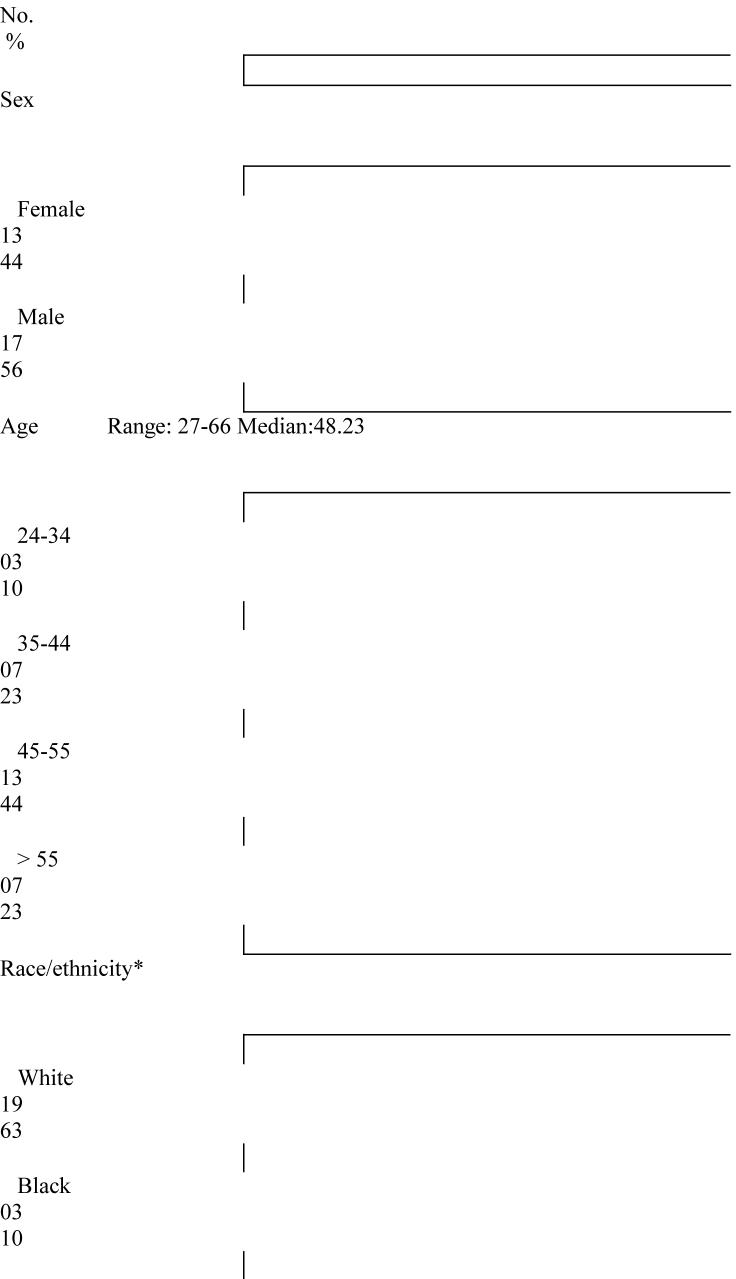

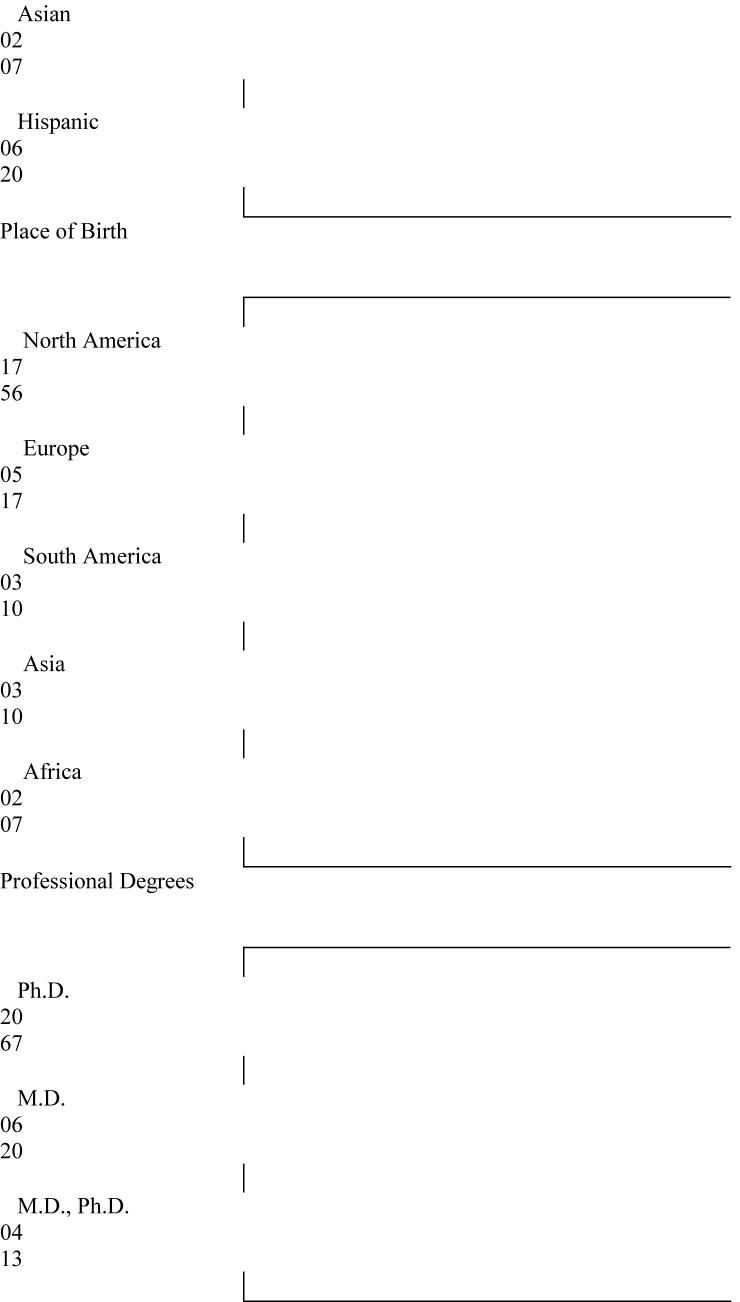

We conducted interviews with a purposive, snowball sample of human genetics researchers who use race and ethnicity as variables in their studies. We began by contacting researchers we already knew through various academic networks, then solicited scientists they recommended as possible subjects. We also contacted researchers who were publishing on related topics, or who had recently received federal funding for pertinent projects. We attempted to include researchers from a variety of disciplines, and members of diverse racial/ethnic groups. We contacted the researchers individually, by e-mail or telephone, asking if they would be willing to be interviewed for a study exploring how genetic scientists and clinicians integrate concepts of race and ethnicity into their work. Of the 60 scientists we contacted, 35 agreed to participate, 6 declined, 19 never responded, and 5 were not interviewed due to scheduling problems. We interviewed 30 genetic scientists (21 in person, and 9 by telephone), at 17 universities, hospitals and research institutes in 8 U.S. States and in Canada. These were all principle investigators, with Ph.D. and/or M.D. training, specializing in fields ranging from molecular biology, to bio-statistics, to human genetics. They discussed 45 research projects with us, involving racial/ethnic identifiers as a central variable in the research design, and for which they were either PI (Principal Investigator) or co-PI. While most subjects (17) only discussed one project in the interviews, 11 discussed two, and two discussed three projects. These included an assortment of types of studies including DNA sequencing, population modeling, and linkage studies, focusing on a variety of diseases including rare inherited diseases, common chronic diseases and mental disorders. Table 1 summarizes a number of characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Selected Characteristics of 30 Scientists Interviewed

|

|

|

|

Interviews followed a standardized set of open-ended questions, averaged about two hours, and were tape-recorded and transcribed. All subjects were asked the same questions, but were encouraged to answer as expansively as they chose. We were careful to probe for as much detail as possible regarding the core topics of interest to this study, such as which classifications were used, how they were defined, and techniques for classifying individual cases. All study participants gave their informed consent to be interviewed, following IRB approved protocols.

All phases of data processing and analysis were cross-checked in conference sessions wherein the research team discussed each case, reviewed emerging findings, honed analysis strategies, and reached consensus about the application of coding categories. In order to minimize investigator bias, throughout the project we conducted spot-checks for consistency in coding and classification procedures, addressing any anomalies as they emerged.

CONCEPTS AND PRACTICES

While our findings cannot be assumed to be generalizable beyond our small sample, analysis of the concepts and practices these researchers discuss clearly illustrate a number of deeply problematic aspects of using racial/ethnic variables in biological research. Consistent with the current common practice in health and clinical research, all of those we interviewed said they routinely collect racial/ethnic identifiers in their research. Most (n=24) used racial/ethnic identifiers as an important part of their research on genetic variation. These include 5 researchers studying population variation in the distribution of genetic markers, and 19 who were studying racial/ethnic variation in genetic characteristics associated with particular diseases. The remainder collected and reported racial/ethnic information, but were not interested in racial/ethnic variation per se. (Two collected the data only to meet federal guidelines, and four others were studying people in a specific geographic area, due to high prevalence of a disease of interest.)

Geographic and Social Classifications

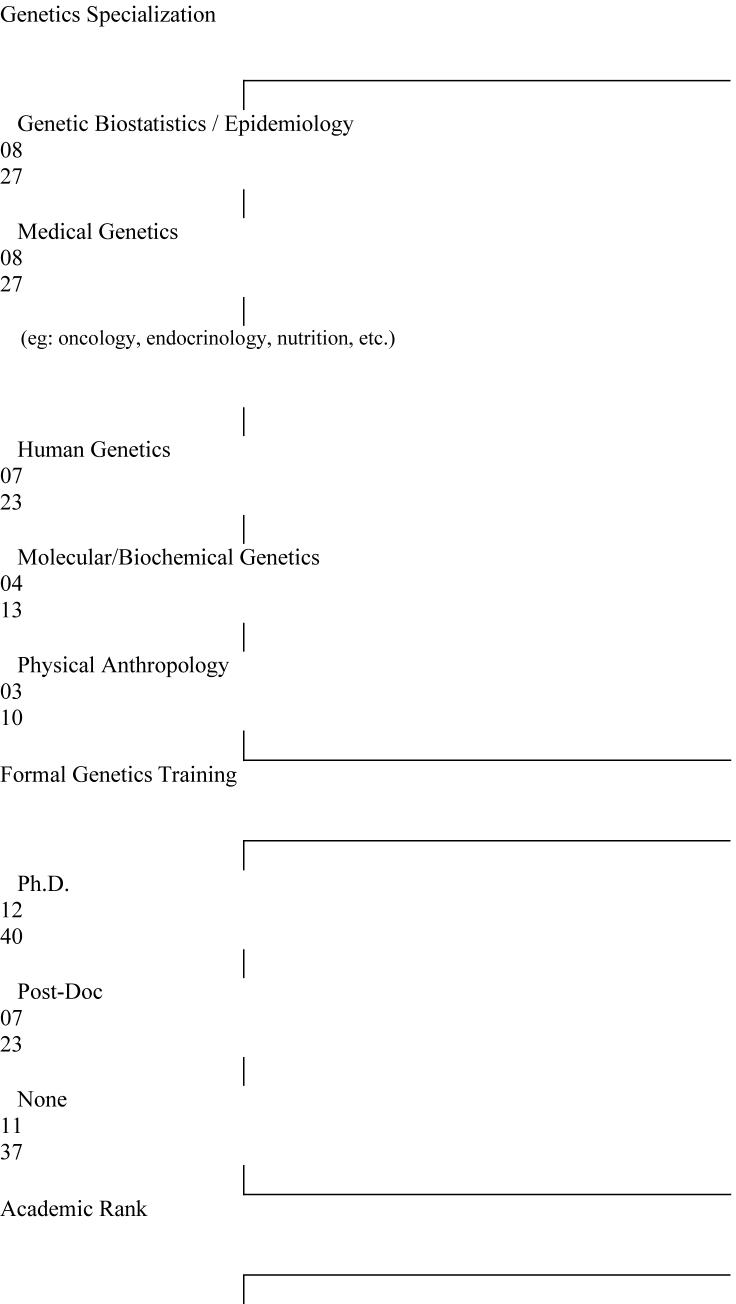

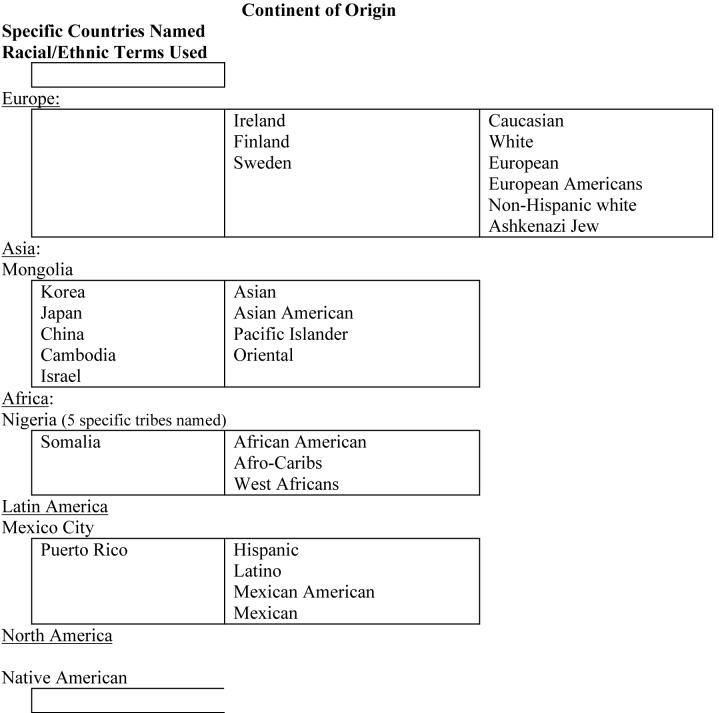

First, let us consider specifically how racial/ethnic groups were defined by these researchers. Several said they classified their samples primarily based on the geographic locations from which they were collected, for example, using labels such as “Chinese,” “Irish,” “Finnish” or “West African.” More commonly, the researchers said that they used the familiar racial/ethnic categories that corresponded to those used in the U.S. Census and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB): American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black (not Hispanic), White (not Hispanic), or Hispanic (OMB, 2000). In describing their samples, the researchers most often used everyday racial/ethnic labels such as “black”, “white,” “Europeans,” “African American,” and “Mexican American.” Table 2 presents all of the terms they used to describe the samples from their own research projects.

Table 2.

Geographic and Racial/ethnic Group Classifications Used by 30 Genetic Researchers

|

For the most part, the classifications they used were clearly rooted in the long-held social construct that presumes racial groupings correspond to major continental groups: European, Asian, African, North American. An important aspect of the conventional wisdom behind these particular categories is that geographically separated groups are taken to be equivalent, in terms of continental racial heritage, to socially defined groups whose specific familial migration histories are unknown. While not explicitly articulated as such by those we interviewed, the underlying presumption of racial group membership was clear. For example, samples collected from a relatively isolated village in rural China were described as “Asian”, as were those taken from individuals of partial Japanese heritage living in suburban Detroit. Or a person labeled as “black” in a study in San Francisco was classified as belonging to the same ancestral group as individuals being sampled in Nigeria.2

One researcher, a genetic epidemiologist, expressed the circular logic of a presumed “group” history underlying this ubiquitous practice, when discussing selection of groups for study:

Typically I think about geographical factors - who mates with who - and that’s a classic way population geneticists think about it. In our day-to-day lives, within a geographical area, there are different subgroups that really don’t cross paths and so there can be sub-populations within populations... I would say if we were 100 years ago, where there was less migration, then it would again be geographical location. But, with all of the movement of people, we’ve lost place as the signature of ancestry. And so now the signature of ancestry we focus on has to do with either what they tell us about their ancestry or their skin color.

While presuming that geographically defined groups and socially defined racial and ethnic groups are equivalent may seem relatively straightforward, this in fact requires an important but very weak assumption: that racial/ethnic groups are monolithic through time, and that racial intermarriage is a rather new and exceptional event. As one anthropologist described this problem to us:

People don’t think rigorously about ancestry. ...they trace the long lineage back 10 generations, you know, to 1750 or so. If I look at my own genetic composition, we can narrow that pool a little bit by tracing my mitochondria back and then that would be one of my 1023 ancestors. That leaves 1022 that I am equally related to, unaccounted for.

Between the views discussed by these two researchers, we see a very basic difference in perspective, like looking at a terrain through different ends of the same telescope. The epidemiologist, focusing on current populations, reasons that, due to the general effects of a racialized society, a racialized genetic science is an efficient and reasonable approach to understanding variation in disease distribution. The anthropologist, focusing on human ancestry in the very long term, is unconvinced of the value of assuming the genetic relatedness of current socially defined populations (see also: Sankar et al., 2004). To further examine this issue, let us turn our attention to the types of classifications used by the researchers we interviewed.

Disparate Criteria of Classification

A serious problem in using racial and ethnic classifications in scientific endeavors is that they are not used consistently, and the categories themselves are varied, shifting, and highly context specific (Keita & Kittles, 1997; Bhopal, 1998; Lee et al., 2001; Braun, 2002). A sound classification system should have three basic features: 1) consistent and unique principles of classification; 2) categories which are mutually exclusive, and 3) capacity to absorb all cases (Bowker & Star, 1999). To what extent do the racial/ethnic categories used by the genetic researchers we interviewed meet these criteria?

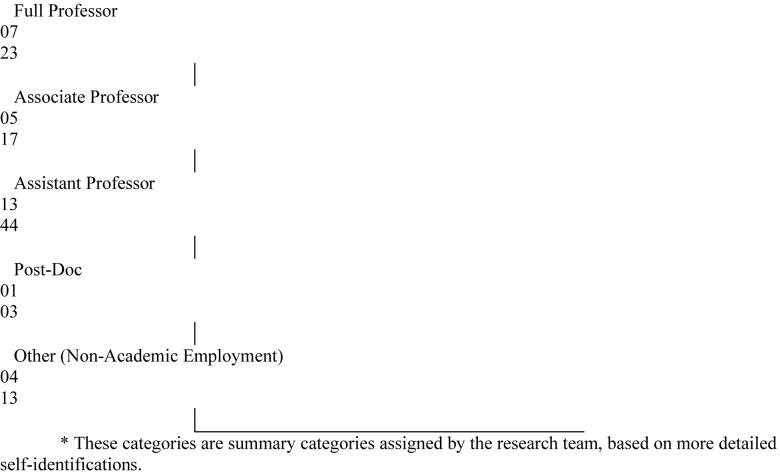

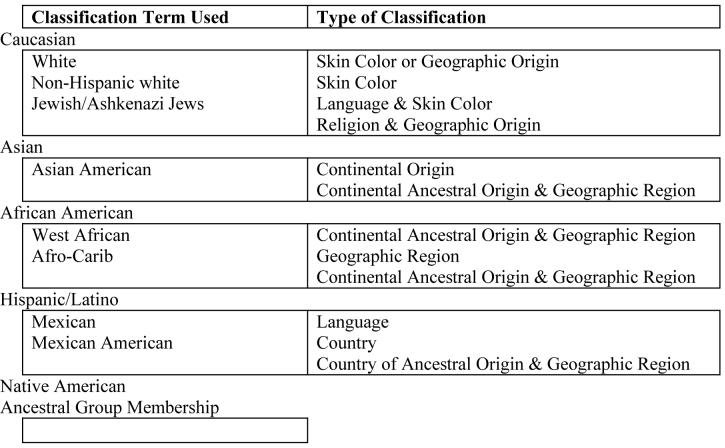

The researchers, for the most part, did not use specialized language to describe the racial/ethnic groups they were studying, but instead used colloquial racial/ethnic labels that are quite familiar in our society. In Table 3 we have listed the terms the researchers most commonly used in describing their own research projects. This table also includes a list of “Types of Classifications” which we propose to describe the apparent basis of each term.

Table 3.

Racial/Ethnic Classification Terms Most Commonly Used by 30 Genetic Researchers and Types of Classification they Appear to Represent.*

|

Terms were included in Table 3 if they were mentioned by at least 4 different researchers in interviews when describing their own research projects. The labels used for “Types of Classification” are meant to be descriptive, and are based on a consensus amongst our project team, in consultation with the Random House Unabridged English Dictionary, 2006.

Laid out this way, the arbitrariness of these categories is striking. There are no fewer than ten distinct types of classifications being used, which consider a wide variety of characteristics ranging from physical appearance, to religious and linguistic groups to geographic location. Clearly, when considered in this light, these seem almost capricious criteria for drawing boundaries around different “populations.” Clearly, such vaguely and inconsistently conceived categories do not begin to meet the basic standards for a classificatory system.

Because these are particularly common and familiar group labels, it may not be immediately obvious why they are deeply problematic when used to organize scientific analysis. However, these categories are not mutually exclusive and no clear principles exist to apply them. Confusion about how to classify individual patients or samples was frequently discussed by those we interviewed. For example, one clinical geneticist commented:

I have a hard time with the term “African American.” Many of the samples we receive from individuals who maybe we would put in that category, would not necessarily check that category themselves. If for example, we get a sample from someone who is from Africa, then they have a problem if you say “African American.” Because they are not American... In fact, we have samples from some that say “I’m black Canadian,” you know, not “African American.”

Because the classifications are overlapping, in order to place individuals somewhere in this system, a choice must often be made between competing criteria. In the absence of principles to guide these decisions, it seems that tacit social constructs may be implicitly driving how identities are prioritized in assigning classifications. A medical doctor, conducting research on the genetic basis of a chronic disease in African Americans, made this observation:

Everybody’s mixed up in reality I mean there are no pure races, it’s not just blacks admixed with Indian and whites. It’s whites admixed with blacks. But, the way we classify people sort of minimizes the admixture of whites. You don’t get considered “white” if you look too much black or you look too much phenotypically non-white or if you have certain type of hair - you don’t get called just plain “white.” There is a whole lot of heterogeneity within black and within white that just goes unappreciated and under-recognized and there a lot of different kinds of people other than just blacks and whites.

In discussing a study of Mexican American families affected by diabetes, another researcher, a medical geneticist, illustrates how such identity-trumping can get played out in research designs:

(In our study) the probands are Mexican-American. And the great majority, I think 95% of the family members, meet the definition [we use for Mexican American]. But, you know, there’s no way to prevent inter-marriage. I mean, there are cases in which we went to first, second, and third degree relatives. In some cases the spouses were not Hispanic, you know, they’re what we call the “marry-ins.”

Thus, in this model, certain members of the family are categorized as “Mexican-American,” and those outside that definition are essentially classified as interlopers on an otherwise pure type, rather than as legitimate genetic contributors to the family. Although such intermarriage is in fact by no means exceptional in the U.S., in these interviews researchers were clearly committed to the opposite view, treating “admixture” as an exceptional event, which did not require rethinking the classification categories.

It is noteworthy that, while nearly all of those we interviewed found the standard racial/ethnic categories to be inadequate in many ways, and felt that they are especially problematic for mixed-race people, none reported a systematic way of dealing with these problems. Indeed, several researchers said that individuals reporting more than one category would be simply excluded from their analyses.

Procedures for Assigning Classifications

Now we turn our attention to the specific practices these researchers reported using for assigning racial/ethnic labels to subjects in the 45 research projects they discussed with us. A handful of projects (n=5) involved analysis of secondary data, and the researchers said they had not found out specifically how the race/ethnicity of the samples had been assigned. For several projects (n=8), the researchers said they labeled their sample based on the geographic location from which they were collected, for example “Finland” or “Central Asia.” By far, the most prevalent classificatory practice the researchers described was using “self-identification.” For nearly three-fourths of the projects (32/45) they said that the subjects themselves chose the racial/ethnic identifiers. This pronounced reliance on self-identification is problematic in several ways, compounding the problems of the classification system itself.

In a few cases (n=5) self-identification was treated as an open-ended question, and subjects’ volunteered responses were simply recorded. Of course, at some point these responses will be reclassified into pertinent categories, depending on the reporting needs of the researcher. However, when asked how these open-ended responses would be converted into racial/ethnic categories, none of the researchers could explain exactly how this would be done.

In most projects (n=12), the researchers said that they ask subjects to choose a label from a simple list of racial/ethnic categories, more or less based on the list of OMB classifications described above: African American, white, Hispanic, etc. Although this may seem a rather straightforward approach, there is no way to know how individuals make this decision. The basis of their choosing any given category is completely unknown. Racial and ethnic identities are formed in a myriad of ways. Subjects may take any number of factors into consideration and weight them differently in choosing their own identity. A compelling illustration of this conundrum is provided by one of the researchers in our study, mulling through how to respond to our question: “How would you describe your own racial/ethnic background?”

So I’ve got one grandparent from Cape Verde, I’ve got grandparents from Portugal. I was born in Mozambique; my parents were living there when I was born. So I grew up speaking Portuguese. But if you go back a few generations, I’ve got people from all over the place. So, I usually go for “Other,” or something. But if I say “Other” then someone might look at me and say, “You’re not ‘Other,’ you’re ‘White.’” I don’t know. At some point, I thought maybe I should put myself as “Hispanic.” But then, if you look at the definition of “Hispanic” it says “Spanish, South American, Mexican.” It’s got a long list, but it doesn’t include Mozambique or Portugal, and so I think - “No, I don’t really want to say I’m Spanish,” so.... Then I think, “Well I have the one grandparent - I could go for that. But on the other hand I was born in Mozambique, so...

For several projects (n=12), in addition to selecting a category from a list, self-identification included questions such as the subject’s birthplace and their parents’ and grandparents’ place of birth and ethnicity. These were primarily studies focusing on Hispanics or Jews. Notably, while the researchers discussed 21 studies that included African Americans, questions about subjects’ heritage were never reported to be used with this group. This raises the disturbing question of why race and ethnicity are assigned using different procedures, depending on the racial/ethnic category in question. Some might argue that this reflects a notion of hypodescent3 imbedded in the way people are classified as African Americans. Consider, for example, the following exchange with a genetic epidemiologist, in which the African American identity is taken to be self-evident and unequivocal.

-

Researcher: We were studying African-Americans.

Interviewer: How did you know that they were African-Americans? How was that determined?

-

Researcher: Well, that was determined because they were born in this country and they were African descended. So...

Interviewer: So, you would ask them their descent, or---?

Researcher: First, I was not the one that was recruiting this. [This was a secondary analysis.]... The [original] PI was a geneticist, and was African American, and she was recruiting African-Americans.... 100% of the samples came from the African-American population. That was, by design, what she was looking for...

In contrast, of the 18 studies that included Hispanic subjects, several augmented self-identification protocols with a series of questions regarding the birthplaces, surnames, and preferred ethnic identities of the subjects, their parents and sometimes their grandparents. In the abstract, this may seem a more thorough and accurate method of classifying subjects than those discussed above. However, it is not clear how much is gained by including such questions. We could discern no clear principles behind which specific questions were asked or how responses would be classified, and as a result, there was no apparent consistency between these studies in how the Hispanic classification was being constructed or applied. One study, described here by an endocrinologist, illustrates the arbitrariness of these schema:

Basically, there’s some kind of a list of a list of 8,000 Spanish surnames. Which is actually computerized, and you can just enter them, and see “yes” or “no,” whether it’s on the list. And we took the view that if you have a Hispanic surname you’re Hispanic until proven otherwise. What is proven otherwise? Well, if you are a non-Hispanic woman who married a Mexican-American man - So, we were conscious of those. ... We got the names of people’s parents, the maiden name, and the names of their grandparents. So, if you’re Rodriguez, but your father and your mother’s maiden name is Smith and Jones and you’re husband is Rodriguez and his parents are Rodriguez, you know...

As illustrated by this quote, there are very important limitations to categorizing ethnicity based on seemingly detailed information about heritage. Obviously, presuming that naming conventions are a good indicator of genetic heritage is an ambitious assumption. But, in addition to this, a deeper problem exists in applying this approach to classification of individuals. The data collected with questions about birthplace and ancestry will produce a continuous variable. Individuals would be plottable along a continuum of “Hispanic-ness,” depending on unique combinations of their own and their forebearers’ names, birthplaces, etc. However, in practice, this is treated as a dichotomous variable: in the end, individuals are either classified as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. When asked to describe specific criteria for converting this continuous variable into a dichotomous one, none of the researchers seemed to know exactly how this would be accomplished.

But were we to resolve this problem by developing standardized sets of questions and criteria for identifying ancestry, would we then be able to appropriately classify race and ethnicity? We would argue “no,” both because the categories themselves are highly problematic, and because group identity is fluid, dependent on time and context. One population geneticist cogently observed:

Ethnicity, what does it mean genetically, tell me? I mean, people use “Hispanics,” but Hispanic includes lots of people, right? You’ve got Caribbeans, you’ve got Mexicans, you’ve got Peruvians. I mean, it’s a label that we use for our own convenience... I will give you another example. “Black” in terms of Africans. The typology is black skin, curly hair, you know, big noses. But, it’s not true. You go to Africa and start from east to west or go from north to south, you’ll find extreme variability. So you would have to know the background of each and every ethnic group before you make these judgments. ... Even within America they say “African,” but there’s an extreme genetic mixture.

By focusing on the tremendous variability that is buried in the common terms “Hispanic” and “African American,” we thus are confronted with the central problem of attempting to classify people into racial/ethnic groups: the groups themselves are inherently arbitrary and context specific. Population groups simply do not have clear boundaries: group identity is by its very nature fluid and changing, genetic and phenotypic variations are widely shared, and individuals are quite commonly members of more than one group (Race Ethnicity and Genetics Working Group, 2005). Thus, procedures attempting to classify people into clearly bounded groups necessarily will require arbitrary and context specific decisions - whether by the researcher’s judgments, the rules of an algorithm or choices of the individual subjects themselves.

DISCUSSION

A number of serious problems with using race/ethnicity as a variable in genetics research have emerged in our analysis of our interviews with this group of genetic scientists. At the most basic level, the common racial/ethnic classifications they routinely use are of questionable value for delineating genetically related groups. The ubiquitous OMB categories in fact were designed for political and administrative purposes; they were not designed for use as scientific variables (Kertzer & Arel, 2002; Shields et al., 2005). These are notably ambiguous and arbitrary categories, based on strikingly diverse criteria such as skin color, language, or geographic location. They do not compose clear classifications, but instead are overlapping and not mutually exclusive. In the absence of clear principles for applying the labels, in practice, different aspects of an individual’s identity are arbitrarily prioritized, in order to fit individual cases into the schema.

A serious conceptual problem that reinforces the use of these questionable categories is that many of the researchers presume racial admixture is relatively rare and recent, and that specific geographically defined groups, such as Finnish or Japanese, can unproblematically be equated with broad socially designated racial/ethnic groups, such as white or Asian. However, this logic relies on several unsubstantiated assumptions: that historically there were pure racial types associated with particular geographic locations; that migrations were sporadic and relatively rare; and that racial/ethnic groups are primarily endogamous. (A recent study of the views of genetics journals editors reports similar findings: Outram & Ellison, 2006.) These assumptions are contrary to much of what is known about human population history. Genetic isolation among humans is in fact quite rare: human populations have always exchanged mates across broad geographic areas throughout time, producing clinal variation (gradual variation between places), rather than clearly distinct genetic stocks. Furthermore, racial admixture is not an exceptional event; indeed, there has been significant intermarriage between socially designated groups throughout history (Weiss, 1998; Harry & Marks, 1999; Race Ethnicity and Genetics Working Group, 2005). Compounding these conceptual problems is the practical fact that assigning these labels to individuals is often done in the absence of any specific knowledge of their actual familial migration histories.

Heavy reliance on self-identification, as reported by these researchers, further amplifies the imprecision to these variables. Despite its popularity, this method for classifying cases is extremely problematic. Racial/ethnic identities are inherently amorphous constructs; they are multiple and fluid, and may change as a person moves between social, economic and geographic contexts (Berry, 1993; Hunt, Schneider & Comer, 2004). There is no way to know what criteria an individual may apply when classifying their own racial/ethnic identity, and the criteria is likely to vary dramatically from person to person. Although some researchers collect additional information about parents and grandparents, this is only done for certain racial/ethnic groups, and never with others, and there appears to be no standard criteria for assigning group membership based on the additional information.

Thus our analysis presents a compelling picture of the serious problems inherent in the concepts and practices of classifying racial/ethnic identity in genetics research. However, our study is limited in several ways. Although we attempted to include a diverse cross-section of human genetics researchers, this was a small, convenience sample, and we cannot draw broad conclusions about genetic research practices in general. We also are relying on the geneticists’ self-reports of their own behaviors in applying categories, rather than observations of their actual practices. We have no way to assess the accuracy of these self-reports, or whether this has introduced any systematic bias into our findings. Furthermore, because this was an exploratory study relying on open-ended answers, making comparisons between subjects is cumbersome at best. Future research would be needed to test whether the problems we have identified are indeed unresolved amongst researchers throughout the field. Still, this study has raised some very basic and important considerations, which should be carefully considered when debating the value of using socially defined racial/ethnic categories as variables in genetics research.

Currently, race/ethnicity is among the most commonly used variables in health research, and is of particular interest to researchers studying the genetic basis of variation in human health (Comstock et al., 2004; Dressler et al., 2005; Shanawani, Dame, Schwartz & Cook-Deegan, 2006). What is routinely forgotten, and what this study illuminates, is that racial and ethnic categories are created and classified arbitrarily, based on colloquial notions of similarity and difference. We have argued elsewhere that, without rigor in defining terms and criteria in research on minority groups, widely held stereotypes may be allowed to drive the research (Hunt et al., 2004).

So, if current practices are unacceptable, what should be done instead? A variety of suggestions have been made in the literature. Some argue that genetic variation between populations is important, and that researchers should continue studying such variation, but use very specific local labels to describe their samples rather than the flawed racial/ethnic labels common today (Sankar & Cho, 2002; Kittles & Weiss, 2003; Keita et al., 2004; Shields et al., 2005). Others suggest including careful analysis of the environmental, social and cultural contexts that affect gene expression, which, they argue, will discourage the biological reductionism that results from more simplistic uses of racial/ethnic labels in genetics research (Krieger, 2005; Smedley & Smedley, 2005; Shields et al., 2005). While these practices may help ameliorate the more egregious misinterpretations and overgeneralizations that might result from such studies, we are not convinced that the deeply rooted tendency toward categorical thinking that underlies the problematic nature of racial/ethnic variables will be resolved.

Other empirical research examining how these concepts are used and interpreted in practice by geneticists would seem to concur with our skepticism. Outram and Ellison (2006) found that the editors of genetics journals they studied failed to see how critiques of using race in genetics research are relevant to what they do. Similarly, McCann and co-authors (2004) conducted an exhaustive analysis of current academic and popular texts addressing race and the Human Genome Project. They found that the public and scientists alike resist giving up notions of the biological legitimacy of race, regardless of how groups are defined, or how small reported differences may be.

It is our position that, despite claims to scientific neutrality, we do in fact live in a racialized society, and prevalent notions of group differences will drive interpretations of racialized data, no matter what labels are used, or what additional variables are included. Persisting in constructing scientific arguments based on highly ambiguous variables that are clearly laden with dubious social meanings, is of deep concern. It is not innocuous to tolerate the logical fallacy of using race to infer genetic background (Krieger, 2005). This unjustifiably promotes the notion that scientific research verifies the existence of biological differences between racial/ethnic groups. Genetic explanations for racial differences in health may in effect create a conceptual barrier to developing integrated research about social inequality and health (Cooper, Kaufman & Ward, 2003; Sankar et al., 2004), and add additional burdens of stigma and negative identity for already marginalized groups (Lee et al., 2001). As Shields and co-authors (2005) have observed, despite claims to the contrary, with these problems unaddressed, this line of research does not hold great promise for addressing health disparities:

The use of such scientifically imprecise variables in genetic studies as a stand-in for measurement of genetic heterogeneity or differential exposure to measurable environmental or social exposures... is methodologically unacceptable, given the availability of more precise measures, and provides little help in elucidating the underlying causes of health disparities. (P. 89)

It is surely troubling that, in an otherwise rigorous field of research, where genetic and disease variables are carefully defined and systematically classified, racial/ethnic variables are not held to the same scientific criteria as are other classification systems (See also: Stanfield, 1993). Despite their routine use, racial/ethnic categories simply lack sufficient rigor to be used as key variables in biological research. Rather than retain them simply because they seem to capture some kind of important variation, we should strive toward a higher standard of scientific integrity: One that carefully explores the actual basis of that variance, and does not tolerate reliance on vaguely defined, inconsistent categories and classification practices. Genetics research, at the cutting edge of technology and science, surely merits a concerted effort to fully address this shortcoming.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health National Center for Human Genome Research through grant #HG2299-05. We wish to thank the researchers we interviewed, whose kind cooperation made this research possible. James Bielo, Daniel Vacanti, Nicole Truesdell provided invaluable assistance with a variety of data analysis and literature review tasks. Mr. Vacanti also made important contributions to the development of the argument we present here.

Footnotes

Generally speaking, “race” refers to inherited biological characteristics and is often based on physical appearance, while “ethnicity” refers to shared origin, shared language, and shared cultural traditions. However, because race and ethnicity are routinely conflated in their common usage in health research, in this paper we will treat them a single construct, “race/ethnicity.”

Some details have been changed for case examples throughout the paper, to preserve anonymity.

The rule of hypodescent classifies the offspring of a mating between members of different races or socioeconomic groups to the less privileged group.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- American Anthropological Association [Accessed: June 2007];Response to OMB Directive 15: Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administrative Reporting. 1997 < http://www.aaanet.org/gvt/ombdraft.htm>.

- Bamshad M. Genetic influences on health: does race matter? JAMA. 2005;294(8):937–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Ethnic Identities in Plural Societies. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and Other Minorities. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1993. pp. 271–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal R. White, European, Western, Caucasian, or what? Inappropriate labeling in research on race, ethnicity, and health. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(9):1303–1307. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker GC, Star SL. Sorting things out: classification and its consequences. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Braun L. Race, Ethnicity, and Health. Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(2):159–174. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2002.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun L. In: Singer E, Antonucci T, editors. Genetics and Health disparities: What is at Stake?; Proceedings of the Workshop on Genetics and Health Disparities; Survey Research Center, Institute for Social, University of Michigan. 2004.pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Armelagos GJ. Apportionment of Racial diversity: A Review. Evol Anthropol. 2001;10:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, Mountain JL, Perez-Stable EJ, Sheppard D, Risch N. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1170–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL. The DNA revolution in population genetics. Trends in Genetics. 1998;14(2):60–65. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL. The Human Genome Diversity Project: past, present and future. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2005;6(4):333–340. doi: 10.1038/nrg1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Wilson AC, Cantor CR, Cook-Deegan RM, King MC. Call for a worldwide survey of human genetic diversity: a vanishing opportunity for the Human Genome Project. Genomics. 1991;11(2):490–491. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90169-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MK. Racial and ethnic categories in biomedical research: there is no baby in the bathwater. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2006;34(3):497–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS. What we do and don’t know about ‘race’, ‘ethnicity’, genetics and health at the dawn of the genome era. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S13–S15. doi: 10.1038/ng1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock RD, Castillo EM, Lindsay SP. Four year review of the use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic and public health research. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:611–619. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Ward R. Race and genomics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1166–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb022863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler WW, Oths KS, Gravlee CC. Race and ethnicity in public health research: models to explain health disparities. Ann Rev Anthropol. 2005;34:231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gannett L. Racism and Human Genome Diversity Research: The Ethical Limits of “Population Thinking”. Philosophy of Science. 2001;68(Supp):S479–S492. doi: 10.1086/392930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AH. Why genes don’t count (for racial differences in health) Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1699–1702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry D, Marks J. Human population genetics versus the HGDP. Politics & the Life Sciences. 1999;18(2):303–305. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400021535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(5):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Project [Accessed: June 2007];International HapMap Project. 2005 < http://www.hapmap.org/thehapmap.html.en>.

- Jones CP, LaVeist T, Lilli-Blanton M. “Race” in the epidemiological literature: an examination of the American Journal of Epidemiology, 1921-1990. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1079–1084. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorde LB, Wooding SP. Genetic variation, classification and ‘race’. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S28–S33. doi: 10.1038/ng1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson E, Tang H, Gadde M, Province M, Leppert M, Kardia SLR, Schork NJ, Cooper R, Rao DC, Boerwinkle E, Risch N. Ethnicity and human genetic linkage maps. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:276–290. doi: 10.1086/427926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keita SOY, Kittles RA. The persistence of racial thinking and the myth of racial divergence. Am Anthropol. 1997;99(3):534–544. [Google Scholar]

- Keita SOY, Kittles RA, Royal CD, Bonney GE, Furbert-Harris P, Dunston GM, Rotimi CN. Conceptualizing human variation. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S17–S20. doi: 10.1038/ng1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzer D, Arel D. Census, Identity Formation, and the Struggle for Political Power. In: Kertzer D, Arel D, editors. Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity and Identity in National Censuses Cambridge. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kittles RA, Weiss KM. Race, ancestry, and genes: Implications for Defining Disease Risk. Ann Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4(1):33–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Stormy weather: race, gene expression, and the science of health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(12):2155–2160. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS-J. Racializing drug design: implications of pharmacogenomics for health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(12):2133–2138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS-J, Mountain J, Koenig BA. The meaning of “race” in the new genomics: Implications for Health Disparities Research. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2001;1:33–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin R. The apportionment of human diversity. J Evol Biol. 1972;6:381–398. [Google Scholar]

- McCann-Mortimer P, Augoustinos M, LeCouteur A. ‘Race’ and the Human Genome Project: Constructions of Scientific Legitimacy. Discourse & Society. 2004;15(4):409–432. [Google Scholar]

- Mountain JL, Risch N. Assessing genetic contributions to phenotypic differences among ‘racial’ and ‘ethnic’ groups. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S48–S53. doi: 10.1038/ng1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMB (Office of Management and Budget) [Accessed: June 2007];Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. 2000 Feb 11; < http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/Ombdir15.html>.

- Ossorio P, Duster T. Race and genetics: controversies in biomedical, behavioral, and forensic sciences. American Psychologist. 2005;60(1):115–128. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outram SM, Ellison GTH. Anthropological insights into the use of race/ethnicity to explore genetic contributions to disparities in health. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2006;38:83–102. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race Ethnicity and Genetics Working Group The Use of Racial, Ethnic, and Ancestral Categories in Human Genetics Research. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77(4):519–532. doi: 10.1086/491747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon J. Race to the Finish. Princeton University Press; Princeton, N.J.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik DB. The Human Genome Diversity Project: ethical problems and solutions. Politics & the Life Sciences. 1999;18(1):15–23. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, Tang H. Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome Biology. 2002;3(7):1–12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi CN. Are medical and nonmedical uses of large-scale genomic markers conflating genetics and ‘race’? Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11 Suppl):S43–S47. doi: 10.1038/ng1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar P, Cho MK. Genetics. Toward a new vocabulary of human genetic variation. Science. 2002;298(5597):1337–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1074447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar P, Cho MK, Condit CM, Hunt LM, Koenig B, Marshall P, Lee SS, Spicer P. Genetic research and health disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(24):2985–2989. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanawani H, Dame L, Schwartz DA, Cook-Deegan R. Non-reporting and inconsistent reporting of race and ethnicity in articles that claim associations among genotype, outcome, and race or ethnicity. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2006;32:724–728. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields AE, Fortun M, Hammonds EM, King PA, Lerman C, Rapp R, Sullivan PF. The use of race variables in genetic studies of complex traits and the goal of reducing health disparities: a transdisciplinary perspective. American Psychologist. 2005;60(1):77–103. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley A, Smedley BD. Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real. American Psychologist. 2005;60(1):16–26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield JH. A History of Race Relations Research: First Generation Recollections. Sage; Newbury Park: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stocking GW. The Turn-of-the-Century Concept of Race. Modernism/Modernity. 1994;1(1):4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriquez B, Kardia SLR, Xiaofeng Z, Brown A, Pankow JS, Province MA, Hunt SC, Boerwinkle E, Schork NJ, Risch N. Genetic structure, self identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;76:268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss KM. Coming to terms with human variation. Ann Rev Anthropol. 1998;27:273–300. [Google Scholar]