Abstract

Rat alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) in primary culture transdifferentiate from a type II (AT2) toward a type I (AT1) cell-like phenotype, a process that can be both prevented and reversed by keratinocyte growth factor (KGF). Microarray analysis revealed that these effects of KGF are associated with up-regulation of key molecules in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. To further explore the role of three key MAPK (i.e., extracellular signal–related kinase [ERK] 1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK] and p38) in mediating effects of KGF on AEC phenotype, primary rat AEC cultivated in minimal defined serum-free medium (MDSF) were treated with KGF (10 ng/ml) from Day 4 for intervals up to 48 hours. Exposure to KGF activated all three MAPK, JNK, ERK1/2, and p38. Inhibition of JNK, but not of ERK1/2 or p38, abrogated the ability of KGF to maintain the AT2 cell phenotype, as evidenced by loss of expression of lamellar membrane protein (p180) and increased reactivity with the AT1 cell-specific monoclonal antibody VIIIB2 by Day 6 in culture. Overexpression of JNKK2, upstream kinase of JNK, increased activation of endogenous c-Jun in association with increased expression of p180 and abrogation of AQP5, suggesting that activation of c-Jun promotes retention of the AT2 cell phenotype. These results indicate that retention of the AT2 cell phenotype by KGF involves c-Jun and suggest that activation of c-Jun kinase may be an important determinant of maintenance of AT2 cell phenotype.

Keywords: alveolar epithelium, mitogen-activated protein kinase, c-Jun, keratinocyte growth factor, microarray

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

This article reports the novel finding that the effect of keratinocyte growth factor to reverse alveolar epithelial phenotype change is c-Jun N-terminal kinase–dependent. Thus the work links a specific signal transduction pathway to the phenotypic change in these cells.

Lung alveolar epithelium, composed of type I (AT1) and type II (AT2) cells, forms a tight functional barrier that limits the leakage of solutes and water from the interstitial and vascular compartments into the alveolar spaces, while actively transporting sodium in a vectorial fashion (1–3). An intact epithelial barrier is essential for maintaining relatively dry alveolar spaces and normal gas exchange. In addition to their roles in surfactant production and active ion transport, AT2 cells are believed to serve as progenitors for restoration of alveolar epithelium in the adult lung during normal maintenance and repair following injury, with AT2 cells either giving rise to new AT2 cells or transdifferentiating into AT1 cells (4, 5). Despite its importance to understanding mechanisms of lung repair, little is known regarding the signal transduction pathways that regulate phenotypic transitions between AT2 and AT1 cells.

Freshly isolated rat AT2 cells grown in culture for several days have served as a useful in vitro model with which to investigate mechanisms regulating alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) function and differentiation. AT2 cells cultured over a period of 3 to 4 days gradually lose their characteristic phenotypic hallmarks and change morphologically to resemble AT1 cells. Concurrently, levels of surfactant lipids, apoproteins, and other AT2 cell markers decline and cells increasingly acquire phenotypic markers specific for AT1 cells in situ (e.g., aquaporin-5 [AQP5] and T1α/RTI40) as well as reactivity with the AT1 cell-specific monoclonal antibody (VIIIB2), suggesting that these cells are transdifferentiating toward an AT1 cell-like phenotype resembling the process in vivo (1, 4, 5).

Transition between AT2 and AT1 cell differentiated phenotypes in vitro appears to be highly regulable, and various experimental conditions have been identified that promote retention of the AT2 cell phenotype (4, 5). In this regard, transdifferentiation toward the AT1 cell phenotype can be both prevented and reversed by treatment with keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) (2). Addition of KGF to serum-free media from Day 0 maintains the AT2 cell phenotype, whereas addition from Day 4 (by which time AEC exhibit AT1 cell-like characteristics) reverses AEC transition back toward AT2 cell-like phenotype on Day 8 (2). Specifically, KGF both inhibits and reverses expression of T1α and AQP5 and maintains and re-induces expression of surfactant apoproteins (2). However, the mechanisms whereby KGF maintains the AT2 cell phenotype and modulates the process of transdifferentiation between AT2 and AT1 cell phenotypes have not been elucidated.

KGF is a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, which function as growth factors by activating cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors (6). KGF, or FGF-7, is an epithelial-specific mitogen that mediates interactions between mesenchymal and epithelial cells acting through a unique KGF receptor, FGFR-2IIIB, with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (6, 7). KGF has been shown to be protective against a variety of lung injuries (e.g., radiation, bleomycin, and hyperoxia) (8–11). Effects of KGF on the lung are associated with activation of various downstream intracellular proteins such as Akt/Fas (8, 12), ERK (13), sterol-regulatory element–binding protein (SREBP)-1c, and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) α and δ (14). However, the specific signal transduction pathways that mediate effects of KGF on AEC transdifferentiation have not been elucidated. In this study, we explored the mechanisms by which KGF modulates AEC transdifferentiation. Microarray analysis demonstrated up-regulation of several molecules in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway following treatment with KGF, suggesting that MAPK signal transduction pathways may be involved in AEC transdifferentiation. Our results demonstrate that retention of AT2 cell phenotype and reversal of AEC transdifferentiation from AT2 to AT1 cell-like phenotype by KGF involves c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated activation of c-Jun.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Isolation and Culture

AT2 cells were isolated from the lungs of adult male, specific pathogen-free, Sprague-Dawley rats (150–200 g) by disaggregation with elastase (2.0–2.5 U/ml) (Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, NJ), followed by differential adherence on IgG-coated bacteriologic plates as previously described (1–3). Enriched AT2 cells were plated in a minimal defined serum-free medium (MDSF) onto tissue culture-treated polycarbonate (Nuclepore) filter inserts (Transwell; Corning-Costar, Cambridge, MA) at 1 × 106/cm2 and grown to confluence, forming high-resistance monolayers (1–3). Media were changed on the second day after plating and every other day thereafter. Cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. AT2 cell purity (> 85%) of freshly isolated cells was assessed by staining for lamellar bodies with tannic acid or by immunofluorescent staining with 3C9, an antibody (Ab) against p180 lamellar membrane protein (Covance, Berkeley, CA) (15), while viability (> 95%) of cells was measured by trypan blue dye exclusion.

RNA Extraction and Microarray Analysis

RNA sample preparation.

RNA was harvested in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), followed by purification with RNeasy columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quantity was assessed by absorbance at 260 nm, and purity was assessed by absorbance at 260 and 280 nm, in a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Rockland, DE). RNA integrity and concentration were analyzed by microanalysis in an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA).

Whole genome cDNA synthesis.

Total RNA was used as a template to generate cDNA probes for hybridization according to an Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) protocol. Ten micrograms of RNA was combined with 100 pmol of T7-dT-primer and incubated at 70°C for 10 minutes, followed by first-strand synthesis (4 μl of 5× first-strand synthesis buffer, 2 μl of 0.1M DTT, and 1 μl of 10 mM dNTP, incubated for 2 min at 42°C, followed by reaction in 2 μl [200 U/ml] of reverse transcriptase for 1 h at 42°C). Second-strand synthesis was accomplished by addition of 91 μl of DEPC water, 30 μl of 5× second-strand synthesis buffer, 3 μl of 10 mM dNTP mix (200 mM each), 1 μl (2U) Rnase H, 4 μl (40 U) of T4 DNA polymerase, 1.0 μl (10 U) of DNA ligase (Escherichia coli 10 U/ml), incubated at 16°C for 2 hours, followed by 2 μl (20 U) of DNA polymerase for an additional 5 minutes at 16°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 10 μl of 0.5 M EDTA. Reaction product was purified by absorption over a Phase Lock Gel light spin column (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY).

Biotinylation and amplification of cDNA.

Biotinylation and amplification of cDNA were accomplished using an Enzo BioArray HighYield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (Affymetrix). Synthesized cDNA was added to 4 μl HighYield reaction buffer, 4 μl 10× biotin labeled ribonucleotides, 4 μl DTT, 4 μl 10× RNase inhibitor mix, 2.0 μl 20X T7 RNA polymerase, and DEPC-treated water in a total volume of 40 μl. The reaction was incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, and the cRNA product was purified by absorption over an RNeasy column (Qiagen).

Hybridization.

Before hybridization, 15 μg of cRNA was denatured by incubation for 35 minutes at 94°C. Expression analysis was performed on RGU34A whole genome chips (Affymetrix). Hybridization to the RGU34A chip was performed according to standard Affymetrix protocols. Fifteen micrograms of denatured cRNA was added to 3 μl of control oligonucleotide B2 (3 nM), 3 μl of 20× eukaryotic hybridization controls (bioB, bioC, bioD, and cre), 3 μl of herring sperm DNA (10 mg/ml), 150 μl of 2× hybridization buffer and H2O to a final volume of 300 μl. The hybridization cocktail was heated to 99°C for 5 minutes. An Affymetrix RGU34A array was prepared by wetting for 10 minutes at 45°C with 1× hybridization buffer. The hybridization cocktail was transferred to a 45°C heating block for 5 minutes and then clarified by centrifugation. Buffer solution was removed from the array and the clarified hybridization cocktail was added to the array cartridge. The array was hybridized for 16 hours in a 45°C rotisserie oven (60 rpm). The hybridized array was washed, labeled with phycoerythrin conjugated with streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and scanned with a GeneArray scanner (Affymetrix). Data analysis was performed using dChip and NETAFFX software (Affymetrix).

Antibodies and Reagents

3C9, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific for rat lamellar membrane protein p180 (Covance), was used at 1:200 for immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) and 1:500 for Western blotting. VIIIB2 is an mAb specific for rat AT1 cells in situ (16). Antibodies (Abs) for proteins in the MAPK pathway were all from Cell Signaling (Berkeley, CA), including phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of ERK1/2, c-Jun, p38, and JNKK2, which were all used at 1:1,000 for Western blotting. Among MAPK Abs, anti–phospho-p38 is a mouse mAb and the rest are rabbit polyclonal Abs against rat proteins. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against eIF2α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), actin (Santa Cruz), or cyclophilin B (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used at 1:500 in Western blotting for normalization of protein loading. KGF (10 ng/ml) was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Specific inhibitors for ERK1/2 (PD 98059), JNK (JNKI), and p38 (SB 203580) and a negative control for JNKI were all from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA) and were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Western Analysis

SDS-PAGE was performed using the buffer system of Laemmli (17) and immunoblotting followed procedures modified from Towbin (18). AEC grown on polycarbonate filters with or without KGF treatment were rinsed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) and solubilized directly into lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, and aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin at 1 μg/ml each). Protein concentrations were measured using the DC Protein Analysis System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). β-mercaptoethanol was added and samples boiled. Equal amounts of protein (10 μg for studies of protein phosphorylation and 5 μg for other analyses) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically blotted onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk and incubated with primary Abs at 4°C overnight. Blots were washed (×3) with TBS-T (20 mM Tris-7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.01% Tween-20), and incubated with respective horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary Abs for 45 minutes at room temperature. Antigen–Ab complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and analyzed with an Alpha Ease RFC Imaging System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

AEC monolayers grown on polycarbonate filters were fixed with ice-cold methanol for 15 minutes and blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour. AEC were then reacted with primary Abs (3C9 or VIIIB2) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by washing (×3) with PBS. AEC were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary Ab (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by washing (×3) with PBS. Finally, AEC were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated avidin (1:1,000; Vector, Burlingame, CA). Filters were mounted onto slides in Vectashield antifade mounting medium with propidium iodide (PI, red) for nuclear staining (Vector). Slides were viewed with an Olympus BX60 microscope equipped with epifluorescence optics (Olympus, Melville, NY). Images were captured separately using monochrome filters for FITC or rhodamine isothiocyanate with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Magnafire; Olympus). Images were imported into Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) as TIFF files.

Vector Production and Virus Preparation

Recombinant lentivirus vector and packaging constructs were produced as previously described (3). The vector construct, pRRLsin.hCMV.IRES.EGFP, consists of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-based self-inactivating (SIN) replication-defective lentivirus transfer vector expressing an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter gene driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter. Human JNKK2 cDNA was inserted to replace EGFP to generate Lenti-JNKK2. Human 293T cells (80–90% confluence) were cotransfected by calcium phosphate precipitation with 12 μg of pRRLsin.hCMV.IRES.EGFP, 10 μg of pCMVΔR8.91 for viral packaging, and 8 μg of pMD.G for VSV-G pseudotyping. Virus-containing supernatant medium from the transfected cells was harvested and concentrated through a centrifugal concentrator (Macrosep; Pall Gelman Laboratory, Ann Arbor, MI) with a 300-kD molecular mass cutoff and stored at −80°C. Titers of vector stocks were determined on HeLa cells by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) with a Becton-Dickinson FACScan equipped with a 488-nm argon laser and were in the range of 2–5 × 106 transducing units (TU)/ml.

Viral Transduction of AEC

For lentivirus infection, medium was aspirated from the apical reservoir of AEC grown on Transwell filters cups, and fresh medium containing concentrated virus was added for 8 hours in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml). AEC grown on filters on Day 4 were transduced with lentivirus at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, which was previously shown to have a transduction efficiency of over 60% in AEC monolayers (3).

Experimental Protocol

On Day 4 in culture, cells were either maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF supplemented with KGF (10 ng/ml). At selected time points up to 48 hours after addition of KGF, monolayers were harvested for RNA or protein extraction or processed for IFM. Since the protective effect of KGF on lung and on AEC cell proliferation gradually reach a maximum within 2 to 3 days both in vivo (9) and in vitro (10), we chose time points between 1 and 48 hours during which to study the effects of KGF. For kinase inhibition studies, specific inhibitors for ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 at indicated concentrations were added together with KGF. A specific negative control was used for JNK inhibitor at the same molar concentration. DMSO was used as a negative control for ERK1/2 and p38.

Statistical Analysis

Densitometric analyses are shown as mean ± SEM from at least three separate experiments. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) of differences in means was assessed by unpaired Student's t tests between two groups or by ANOVA with post hoc comparisons using modified Newman-Keuls procedures among more than two groups.

RESULTS

Microarray Analysis of KGF-Treated Monolayers

We evaluated changes in patterns of gene expression using microarray analysis during transdifferentiation of AEC from AT2 cell toward AT1 cell-like phenotype and reversal of transdifferentiation after KGF treatment. From Day 4 to Day 5 in MDSF, there was a significant change (defined by microarray intensity changes of 1.5 fold or > 40 arbitrary units) in expression of 407 genes (245 up-regulated, 162 down-regulated). KGF prevented changes in expression of 375 of these genes (92%). In particular, between Day 4 and Day 5, several genes related to the MAPK pathways were down-regulated in cells maintained in MDSF (Table 1). Treatment with KGF from Day 4 to Day 5 largely prevented these reductions and, in the case of MAPK2, led to an overall increase in expression compared with baseline (Table 1, n = 2).

TABLE 1.

MICROARRAY RESULTS OF GENES RELATED TO MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE PATHWAYS UP-REGULATED BY KERATINOCYTE GROWTH FACTOR

| Gene | Probe ID | MDSF Day 4 | MDSF Day 5 | KGF 24 h Day 5 | MDSF Day 5/MDSF Day 4 | KGF 24 h Day 5/MDSF Day 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERK3 | M64301 | 204.47 | 51 | 103.23 | 0.25 | 2.02 |

| ERK5 | AJ005424 | 94.33 | 42.5 | 112.23 | 0.45 | 2.64 |

| C-Jun | rc_AA925556 | 56.98 | 3.2 | 49.66 | 0.06 | 15.52 |

| MAPK2 | rc_AA957896 | 12.43 | 12 | 58.90 | 0.96 | 4.91 |

| RAS | X02601 | 69.2 | 15.8 | 73.24 | 0.23 | 4.64 |

Definition of abbreviations: ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MDSF, minimal defined serum-free medium.

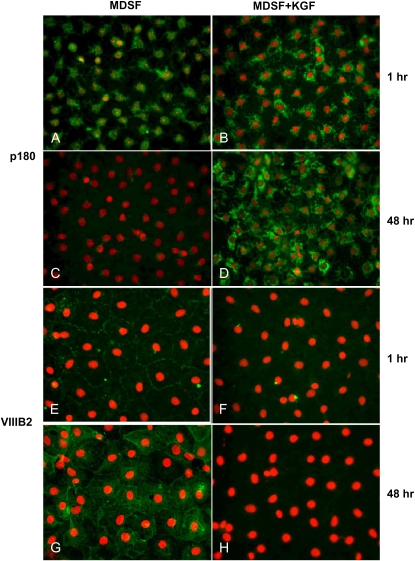

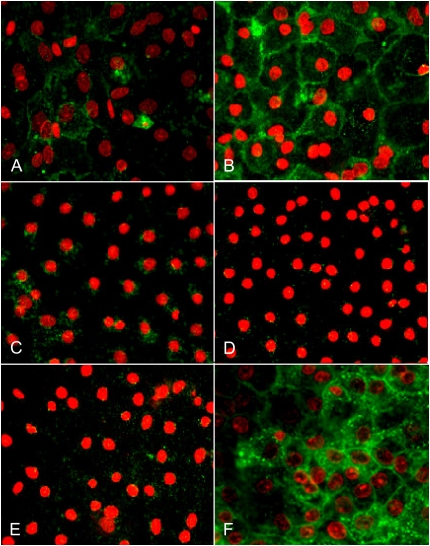

Effects of KGF on Expression of p180 and VIIIB2

Lamellar membrane protein, p180, is highly expressed in AT2 cells and recognized by mAb 3C9 (15). VIIIB2 is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes an epitope on the apical surface of rat AT1 cells (16). To confirm previously observed effects of KGF on AEC phenotype using other phenotypic markers (2), expression of p180 and reactivity with VIIIB2 were evaluated in AEC maintained in MDSF ± KGF from Day 4 for 48 hours. Compared with AEC in MDSF, expression of p180 is maintained in AEC in MDSF+KGF on Day 6, while VIIIB2 reactivity is abolished (Figure 1). These data indicate that KGF inhibits transdifferentiation of AT2 cells to an AT1 cell-like phenotype.

Figure 1.

Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) modulates expression of alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) phenotypic markers. AT2 cell phenotype was identified by expression of lamellar membrane protein, p180, and AT1 cell phenotype was identified by reactivity with VIIIB2. AEC monolayers were plated in minimal defined serum-free medium (MDSF). From Day 4, media were changed to MDSF ± KGF (10 ng/ml). After 1 or 48 hours, monolayers were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM). p180 is present in AEC in MDSF on Day 4 (A) and undetectable on Day 6 (C). After addition of KGF on Day 4 for either 1 hour (B) or 48 hours (D), p180 is maintained. In MDSF, reactivity with VIIIB2 increases between Day 4 (E) and Day 6 (G). Reactivity with VIIIB2 is maintained at 1 hour (F) after addition of KGF on Day 4 but declines dramatically after 48 hours (H), consistent with prevention/reversal of transdifferentiation by KGF. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

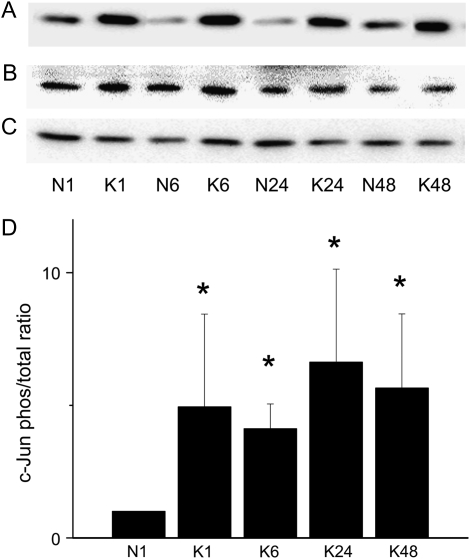

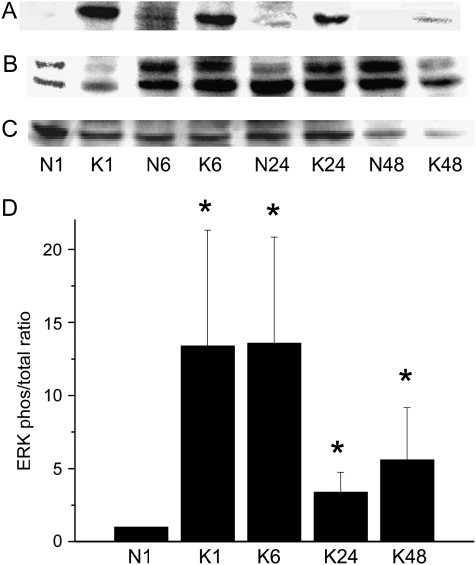

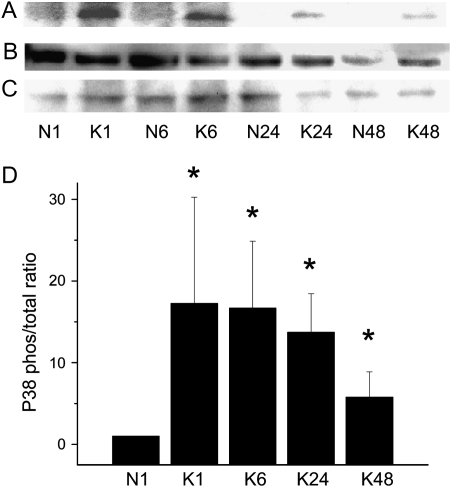

Activation of MAPK Pathways by KGF

Activation of three key kinases in the MAPK signal transduction pathway (JNK, ERK1/2, and p38) was assessed by detection of both phosphorylated (activated) and total protein as functions of time. KGF treatment activated all three kinases, as indicated by phosphorylation of c-Jun (Figure 2), ERK1 (Figure 3), and p38 (Figure 4). Activation of ERK1 and p38 increased by 1 hour, which was sustained through 6 hours and declined thereafter. JNK activation was evident by 1 hour and was sustained through 48 hours in the continuous presence of KGF.

Figure 2.

KGF induces phosphorylation of c-Jun. AEC monolayers were maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF + KGF (10 ng/ml) on Day 4. At 1, 6, 24, and 48 hours after treatment, protein samples were harvested for Western blot to detect levels of phosphorylated (A) and total (B) c-Jun. Cyclophilin B was used as a loading control (C). Densitometric analyses (mean ± SEM, n = 4) are expressed as phosphorylated ERK normalized to total ERK at 1 hour (D). N denotes negative control (MDSF). K denotes MDSF + KGF. *Significantly different from N at 1 hour.

Figure 3.

KGF induces phosphorylation of ERK. AEC monolayers were maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF + KGF (10 ng/ml) on Day 4. At 1, 6, 24, and 48 hours after treatment, protein samples were harvested for Western blot to detect levels of phosphorylated (A) and total (B) ERK1/2. eIF2α was used as a loading control (C). Densitometric analyses (mean ± SEM, n = 3) are expressed as phosphorylated ERK normalized to total ERK at 1 hour (D). N denotes negative control (MDSF). K denotes MDSF + KGF. *Significantly different from N at 1 hour.

Figure 4.

KGF induces phosphorylation of p38. AEC monolayers were maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF + KGF (10 ng/ml) on Day 4. At 1, 6, 24, and 48 hours after treatment, protein samples were harvested for Western blot to detect levels of phosphorylated (A) and total (B) p38. eIF2α was used as a loading control (C). Densitometric analyses (mean ± SEM, n = 3) are expressed as phosphorylated p38 normalized to total p38 at 1 hour (D). N denotes negative control (MDSF). K denotes MDSF + KGF. *Significantly different from N at 1 hour.

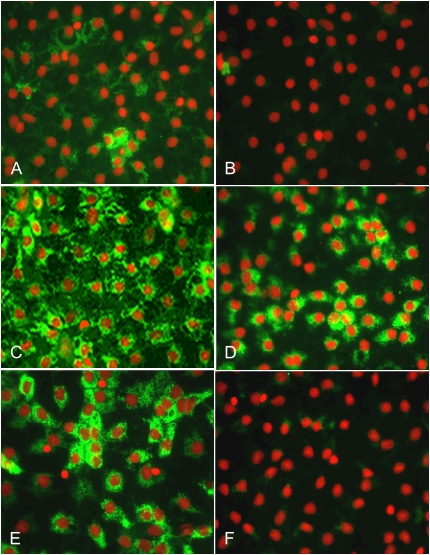

Effects of JNK Inhibition on Reversal of AEC Transdifferentiation by KGF

We determined the contribution of each of the three key MAPK to the ability of KGF to reverse AEC transdifferentiation using specific inhibitors for JNK, ERK1/2, and p38 (Figure 5). From Day 4 (Figure 5A) to Day 6 (Figure 5B) in MDSF, there was a gradual increase in VIIIB2 expression, consistent with transition to an AT1 cell-like phenotype. After addition of KGF on Day 4 for 48 hours, reactivity with VIIIB2 was markedly decreased (Figure 5C). Treatment of AEC from Day 4 with KGF together with ERK1/2 or p38 inhibitors did not reverse the ability of KGF to inhibit VIIIB2 expression (Figures 5D and 5E). However, when JNK inhibitor was added together with KGF for 48 hours (Figure 5F), VIIIB2 reactivity was maintained (Day 6). A specific negative control for JNKI did not affect VIIIB2 reactivity (data not shown). These results suggest that effects of KGF on AEC phenotype were antagonized by specific inhibition of JNK.

Figure 5.

Effects of KGF on VIIIB2 expression is reversed by JNK inhibition. On Day 4, AEC monolayers were either maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF+ KGF in the presence or absence of a specific MAPK inhibitor. After 48 hours, monolayers were processed for IFM. In MDSF, AEC increasingly acquire VIIIB2 reactivity between Day 4 (A) and Day 6 (B), which is inhibited by KGF (C). After inhibition of ERK1/2 (D) or p38 (E), KGF continues to inhibit VIIIB2 reactivity. However, JNK inhibition (F) completely abolishes the KGF effect. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

As shown in Figure 6, acquisition of VIIIB2 reactivity and transition to an AT1 cell–like phenotype in MDSF occurred concurrently with disappearance of the AT2 cell marker, p180 (Figure 6B). In the presence of KGF, p180 expression was maintained (Figure 6C). However, inhibition of ERK1/ERK2 (Figure 6D) and p38 (Figure 6E) did not inhibit the effects of KGF on p180 expression, while KGF failed to re-induce p180 expression in the presence of a specific JNK inhibitor (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Effects of KGF on p180 expression is reversed by JNK inhibition. On Day 4, AEC monolayers were either maintained in MDSF or changed to MDSF+ KGF in the presence or absence of a specific MAPK inhibitor. After 48 hours, monolayers were processed for IFM. In MDSF, AEC no longer express p180 on Day 6 (B) compared with AEC on Day 4 (A), an effect that was reversed by treatment with KGF (C). Inhibition of ERK1/2 (D) or p38 (E) did not prevent the KGF effect. However, JNK inhibition prevented the effects of KGF on p180 expression (F), suggesting that JNK inhibition interferes with the ability of KGF to promote the AT2 cell phenotype. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

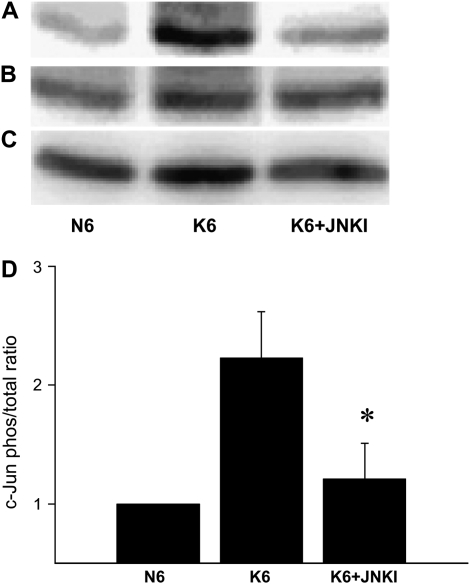

To confirm specificity of the JNK inhibitor, c-Jun phosphorylation was evaluated by Western analysis in AEC treated with KGF in the presence or absence of JNK inhibitor. JNK inhibitor suppressed phosphorylation induced by KGF (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

JNK inhibitor prevents KFG-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun. On Day 4, AEC monolayers were either maintained in MDSF (N6) or changed to MDSF+ KGF in the absence (K6) or presence (K6 + JNKI) of a specific JNK inhibitor (JNKI). After 6 hours, cell samples were processed for Western analysis of phosphorylated c-Jun (A) and total c-Jun (B). Cyclophilin B was used as loading control (C). Densitometric analyses (mean ± SEM, n = 3) are expressed as phosphorylated c-Jun relative to total c-Jun normalized to N6 (D). JNKI decreased phosphorylation of c-Jun in the presence of KGF. *Significantly different from K6.

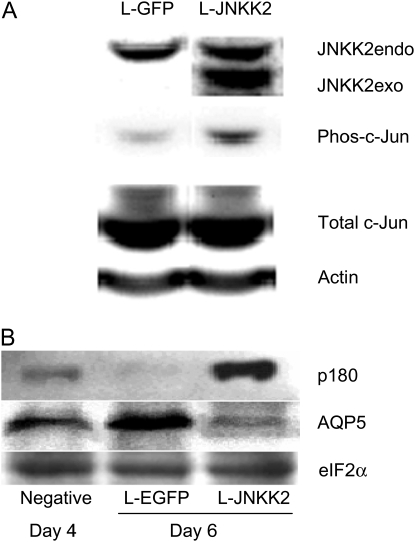

Effects of JNKK2 Overexpression on c-Jun Phosphorylation and AEC Phenotype

To further investigate the effects of c-Jun activation on AEC phenotype, we overexpressed JNKK2, an upstream kinase of JNK, in AT2 cells on Day 4 in culture using a lentivirus vector (Figure 8). Forty-eight hours after transduction with Lenti-JNKK2, we confirmed that exogenous JNKK2 was expressed in AEC (Figure 8A). Overexpression of JNKK2 was accompanied by an increased level of phosphorylation of c-Jun. Compared with cells transduced with Lenti-EGFP, c-Jun phosphorylation increased from 1.63 ± 0.53 to 4.62 ± 1.13 densitometric units (n = 4, P < 0.01) (Figure 8A). AEC transduced with Lenti-EGFP for 48 hours underwent transdifferentiation, as reflected by loss of p180 and up-regulation of AQP5. These data indicate that lentivirus transduction itself did not alter transdifferentiation. AQP5 replaced VIIIB2 as the AT1cell phenotype marker in this experiment because VIIIB2 cannot be used for Western blotting (16). However, in AEC overexpressing JNKK2, c-Jun activation led to an increase in p180 and decrease in AQP5 levels (Figure 8B), suggesting that activation of c-Jun in AEC maintains AT2 cell phenotype.

Figure 8.

Effects of JNKK2 overexpression on AEC phenotype. Primary rat AEC were transduced (MOI of 10) with a lentivirus construct encoding either EGFP as negative control or JNKK2 on Day 4. Forty-eight hours after transduction, protein samples were harvested for Western analysis. (A) Immunoblot showing levels of both endogenous and exogenous (i.e., transfected) JNKK2 (JNKK2endo and JNKK2exo, respectively), phosphorylated c-Jun (phos-c-Jun) and total c-Jun. Overexpression of JNKK2 resulted in increased phosphorylation of c-Jun compared with Lenti-EGFP transfection, while total c-Jun remained unchanged, suggesting increased c-Jun activation after JNKK2 overexpression. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Effect of JNKK2 overexpression on AEC phenotype. After transduction of AEC with Lenti-EGFP, p180 expression is virtually undetectable, while AQP5 expression is increased. These data indicate that Lenti-EGFP transduction alone did not alter AEC transdifferentiation. Forty-eight hours after JNKK2 overexpression, p180 expression became prominent, while AQP5 expression was significantly reduced. These data indicate that overexpression of JNKK2 activates c-Jun and induces phenotypic characteristics of AT2 cells. eIF2α was used as a loading control. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the signal transduction pathways involved in regulation of AEC phenotype by KGF. We first confirmed our previous observations (2) that KGF can reverse the process of AEC transdifferentiation using additional phenotype-specific markers for AT1 and AT2 cells that had not been previously evaluated under these conditions. We demonstrated that lamellar membrane protein p180 is retained while reactivity with the AT1 cell–specific mAb VIIIB2 is abolished after KGF treatment. Using microarray analysis, we evaluated changes in the pattern of gene expression associated with AEC transdifferentiation in the presence and absence of KGF. Microarray analysis revealed that multiple genes in the MAPK pathway were up-regulated by KGF, leading us to focus on this pathway. We demonstrated phosphorylation of three key kinases in the MAPK pathway, namely, ERK1/ERK2, JNK, and p38, by KGF. After addition of KGF, phosphorylation of ERK and p38 increased by 1 hour and declined after 6 hours; in contrast, phosphorylation of c-Jun was increased by 1 hour and continued to increase through 48 hours. We investigated the relative importance of each kinase in mediating the effects of KGF on AEC phenotype using specific kinase inhibitors, concluding that only inhibition of JNK, but not of ERK1/ERK2 or p38, abolishes the ability of KGF to reverse AEC transdifferentiation.

AEC can be identified by panels of phenotype-specific markers. AT1 cells are identified by their expression of AQP5 and T1α/RTI40 as well as reactivity with the AT1 cell–specific monoclonal antibody VIIIB2 (4, 5, 16), whereas AT2 cells are identified by expression of surfactant apoproteins. 3C9, a mAb specific for rat lamellar membrane protein, p180, is a recent addition to the armamentarium of AT2 cell markers (15). We first studied reactivity of AEC with this Ab during the process of transdifferentiation. On Day 4 in culture, when transdifferentiation is well advanced based on previous reports using surfactant proteins (2), weaker but clearly detectable levels of p180 were still present by both IFM and Western blotting. However, by Day 6, p180 was no longer detectable. The time course is consistent with the original report describing this Ab (15).

AEC transdifferentiation toward an AT1 cell–like phenotype can be both prevented and reversed by treatment with KGF (2). Addition of KGF to serum-free media from Day 0 maintains the AT2 cell phenotype, while addition at Day 4 (by which time AEC begin to exhibit AT1 cell characteristics) reverses the transition and re-induces expression of AT2 cell phenotypic markers on Day 8. Specifically, KGF reverses expression of T1α and AQP5 and re-induces expression of surfactant apoproteins (2). KGF has long been known to enhance surfactant synthesis (14), consistent with the notion that KGF preserves AT2 cell characteristics. However, the mechanisms whereby KGF maintains the AT2 cell phenotype and modulates transdifferentiation between AT2 and AT1 cell phenotypes are not well understood. KGF is a member of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family which function as growth factors by activating cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors (6, 8). KGF, or FGF-7, is an epithelial-specific mitogen that mediates interactions between mesenchymal and epithelial cells through a unique KGF receptor (KGFR, FGFR2IIIb) (6). Evidence exists that binding of KGF to KGFR activates MAPK pathways in AEC (6, 13, 19, 20), but it was not known whether activation of MAPK is involved in AEC transdifferentiation.

Significant changes in patterns of gene expression would be expected during the dramatic phenotypic changes that accompany AEC transdifferentiation. Using a microarray approach, we have previously identified genes of known function that are preferentially expressed in AEC of an AT1 cell–like phenotype (1). In the current study, microarray analysis revealed changes in expression of multiple genes in the MAPK pathway during transdifferentiation and after KGF treatment, suggesting a role for this pathway in mediating phenotypic changes in response to KGF. Results of microarray analysis led us to focus further on the MAPK pathway to determine whether these kinases were being activated in response to KGF. Activation of the MAPK pathway is characterized by phosphorylation of the three key kinases. We determined the phosphorylation status of these kinases using specific antibodies for phosphorylated and total proteins of each kinase. Western blotting demonstrated increased phosphorylation of the three key kinases of the MAPK pathway, namely, JNK, ERK1/2, and p38, following treatment with KGF. Phosphorylation of both ERK and p38 are characterized by an early peak at 1 to 6 hours followed by decline to basal level by 48 hours. Comparable patterns for ERK and p38 activation in AEC have been reported. In particular, Portnoy and coworkers (13) reported that KGF at higher concentrations (20 μg/ml) activated ERK1/2, peaking in 5 to 15 minutes and declining thereafter. In contrast, phosphorylation of c-Jun, representing activation of JNK, was observed by 1 hour and remained increased for 48 hours in the present study. In a previous report, JNK activation was not observed after KGF treatment in AEC for a shorter period (13). However, AEC culture conditions were different, in that serum was continuously present in the earlier experiments (13), while in the present study AEC were cultured in serum-free conditions. It is well known that numerous growth factors are present in serum (5) and could induce baseline activation of MAPK. Recently, it was reported that KGF can activate JNK, which in turn induces lipogenesis in H292 cells, a process considered to simulate surfactant production in AT2 cells (14). Thus, it seems clear that cellular mechanisms exist in AEC by which KGF causes JNK activation.

MAPK pathways are important in cell proliferation and differentiation (21, 22). Inhibition of downstream MAPK such as Akt (12) and ERK (13) can block the proliferation of AT2 cells induced by KGF. Activated JNK (and p38) are associated with induction of apoptosis, whereas activation of ERK is linked to cell growth in many cell types, including A549 cells of lung epithelial origin (7, 12, 20). Activation of JNK directly phosphorylates or up-regulates expression of various transcription factors, including c-Jun (21, 22). In the present study, we took advantage of specific inhibitors for each of the three key MAPK (p38 [23, 24], ERK1/2 [25, 26], and JNK [27, 28]) and identified the specific pathway within the MAPK cascade that is responsible for KGF effects on AEC transdifferentiation. Our study indicates clearly that activation of JNK, but not ERK1/2 and p38, is specifically involved in KGF effects on AEC differentiation.

The JNK family comprises JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3. JNK1 and JNK2 show a broad tissue distribution, whereas JNK3 is expressed predominantly in neurons, cardiac muscle, and testes (28, 29). Although in the present work we did not determine the subtype of JNK activated by KGF, the inhibitory effect seen in this study is probably predominantly associated with JNK1, since the negative control used for JNKI has a mild inhibitory effect on JNK2 and JNK3 (27–29), and yet it had no effect on AEC phenotypic changes after KGF treatment. Our results are consistent with previous reports that KGF activates JNK1 (30).

Activation of ERK1/2 and p38 were transient, while the activation of c-Jun was sustained throughout the entire observation period. A difference in the time course of phosphorylation in the three MAPK has been observed in other studies (31). Prolonged activation of JNK has been repeatedly reported (32–34). For example, activation of JNK can persist for days in renal cells after injury, leading to tubulointerstitial fibrosis through proliferation or apoptosis in native renal cells (35). A sustained effect is probably necessary for a process such as cellular phenotypic change. For example, p38 was not activated in nicotine-induced, MAPK-mediated up-regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase, while ERK1/2 activation was short and not required (32). By contrast, JNK phosphorylation was required for tyrosine hydroxylase activation in PC12 cells, albeit delayed and prolonged (with a similar time course to that seen in the present study) (32). The upstream kinases in the JNK pathway include JNKK 1 and 2 (36, 37). JNKK1 activates both JNK1 and p38, while JNKK2 is highly specific for JNK with no activation of p38 (36, 37). Overexpression of exogenous JNKK2 resulted in phosphorylation of c-Jun. This was accompanied by reduced expression of the AT1 marker AQP5 and induction of the AT2 cell marker p180, similar to the effects observed after KGF treatment, further supporting the notion that KGF modulates AEC transdifferentiation through activation of c-Jun. In summary, our results indicate that c-Jun activation is a critical pathway through which KGF mediates phenotypic transitions in AEC and is likely one of the mechanisms by which KGF mediates protective effects after injury and during repair of the lung.

Acknowledgments

The authors note with appreciation the expert technical assistance of Hui Yang and Juan Ramon Alvarez.

This work was supported by an American Lung Association of California Research Grant, National Institutes of Health Research Grants DE10742, DE14183, HL38578, HL38621, HL38658, HL62569, and HL64365, and by the Hastings Foundation. E.D.C. is Hastings Professor of Medicine and Kenneth T. Norris Jr. Chair of Medicine.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0172OC on September 13, 2007

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Qiao R, Zhou B, Liebler J, Li X, Crandall ED, Borok Z. Identification of three genes of known function in type I alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borok Z, Lubman RL, Danto SI, Zhang XL, Zabski SM, King LS, Lee DM, Agre P, Crandall ED. Keratinocyte growth factor modulates alveolar epithelial cell phenotype in vitro: expression of aquaporin 5. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;18:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiao R, Zhou B, Harboe-Schmidt E, Kasahara N, Kim KJ, Liebler JM, Crandall ED, Borok Z. Subunit-specific coordinate upregulation of sodium pump activity in alveolar epithelial cells by lentivirus-mediated gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther 2004;15:457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams MC, Cao Y, Hinds A, Rishi AK, Wetterwald A. T1 alpha protein is developmentally regulated and expressed by alveolar type I cells, choroid plexus, and ciliary epithelia of adult rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1996;14:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borok Z, Hami A, Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Rat serum inhibits progression of alveolar epithelial cells toward the type I phenotype in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1995;12:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finch PW, Rubin JS. Keratinocyte growth factor/fibroblast growth factor 7, a homeostatic factor with therapeutic potential for epithelial protection and repair. Adv Cancer Res 2004;91:69–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panos RJ, Rubin JS, Csaky KG, Aaronson SA, Mason RJ. Keratinocyte growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor are heparin-binding growth factors for alveolar epithelial type II cells in fibroblast-conditioned medium. J Clin Invest 1993;92:969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray P. Protection of epithelial cells by keratinocyte growth factor signaling. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005;2:221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulrich K, Stern M, Goddard ME, Williams J, Zhu J, Dewar A, Painter HA, Jeffery PK, Gill DR, Hyde SC, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor therapy in murine oleic acid-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol 2005;288:L1179–L1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F, Nielsen LD, Lucas JJ, Mason RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta antagonizes alveolar type II cell proliferation induced by keratinocyte growth factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Keratinocyte and hepatocyte growth factors in the lung: roles in lung development, inflammation, and repair. Am J Physiol 2002;282:L924–L940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao S, Wang Y, Sweeney P, Chaudhuri A, Doseff AI, Marsh CB, Knoell DL. Keratinocyte growth factor induces Akt kinase activity and inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis in A549 lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 2005;288:L36–L42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portnoy J, Curran-Everett D, Mason RJ. Keratinocyte growth factor stimulates alveolar type II cell proliferation through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase pathways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Y, Wang J, Lu X, Thewke DP, Mason RJ. KGF induces lipogenic genes through a PI3K and JNK/SREBP-1 pathway in H292 cells. J Lipid Res 2005;46:2624–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zen K, Notarfrancesco K, Oorschot V, Slot JW, Fisher AB, Shuman H. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to alveolar type II cell lamellar body membrane. Am J Physiol 1998;275:L172–L183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Reactivity of alveolar epithelial cells in primary culture with type I cell monoclonal antibodies. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1992;6:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970;227:680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Towbin HH, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedures and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979;76:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta PB, Robson CN, Neal DE, Leung HY. Keratinocyte growth factor activates p38 MAPK to induce stress fibre formation in human prostate DU145 cells. Oncogene 2001;20:5359–5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldys A, Pande P, Mosleh T, Park SH, Aust AE. Apoptosis induced by crocidolite asbestos in human lung epithelial cells involves inactivation of Akt and MAPK pathways. Apoptosis 2007;12:433–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAPK kinases. Cell 2000;103:239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002;298:1911–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiel A, Heinonen M, Rintahaka J, Hallikainen T, Hemmes A, Dixon DA, Haglund C, Ristimaki A. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 is regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2006;281:4564–4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandrasekar B, Mummidi S, Valente AJ, Patel DN, Bailey SR, Freeman GL, Hatano M, Tokuhisa T, Jensen LE. The pro-atherogenic cytokine interleukin-18 induces CXCL16 expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells via MyD88, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6, c-Src, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and activator protein-1 signaling. J Biol Chem 2005;280:26263–26277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langlois WJ, Sasaoka T, Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Negative feedback regulation and desensitization of insulin- and epidermal growth factor-stimulated p21ras activation. J Biol Chem 1995;270:25320–25323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang L, Sawada T, Decker SJ, Saltiel AR. Inhibition of MAP kinase kinase blocks the differentiation of PC-12 cells induced by nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem 1995;270:13585–13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin M, Yan C, Boyd YD. An inhibitor of c-jun aminoterminal kinase (SP600125) represses c-Jun activation, DNA-binding and PMA-inducible 92-kDa type IV collagenase expression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002;1589:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O'Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:13681–13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Z, Boyle DL, Chang L, Bennett B, Karin M, Yang L, Manning AM, Anderson GS. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest 2001;108:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derijard B, Hibi M, Wu IH, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis RJ. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell 1994;76:1025–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan X, Xu C, Pan Z, Keum YS, Kim JH, Shen G, Yu S, Oo KT, Ma J, Kong AN. Butylated hydroxyanisole regulates ARE-mediated gene expression via Nrf2 coupled with ERK and JNK signaling pathway in HepG2 cells. Mol Carcinog 2006;45:841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gueorguiev VD, Cheng SY, Sabban EL. Prolonged activation of cAMP-response element-binding protein and ATF-2 needed for nicotine-triggered elevation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene transcription in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 2006;281:10188–10195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajiguchi T, Yamamoto K, Iida S, Ueda R, Emi N, Naoe T. Sustained activation of c-jun-N-terminal kinase plays a critical role in arsenic trioxide-induced cell apoptosis in multiple myeloma cell lines. Cancer Sci 2006;97:540–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morfini G, Pigino G, Szebenyi G, You Y, Pollema S, Brady ST. JNK mediates pathogenic effects of polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptor on fast axonal transport. Nat Neurosci 2006;9:907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SJ, Jeong KS. Cell-type-specific activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in PAN-induced progressive renal disease in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;323:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng C, Xiang J, Hunter T, Lin A. The JNKK2–JNK1 fusion protein acts as a constitutively active c-Jun kinase that stimulates c-Jun transcription activity. J Biol Chem 1999;274:28966–28971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bubici C, Papa S, Pham CG, Zazzeroni F, Franzoso G. The NF-kappaB-mediated control of ROS and JNK signaling. Histol Histopathol 2006;21:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]