Abstract

Over the past century, understanding the mechanisms underlying muscle fatigue and weakness has been the focus of much investigation. However, the dominant theory in the field, that lactic acidosis causes muscle fatigue, is unlikely to tell the whole story. Recently, dysregulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release has been associated with impaired muscle function induced by a wide range of stressors, from dystrophy to heart failure to muscle fatigue. Here, we address current understandings of the altered regulation of SR Ca2+ release during chronic stress, focusing on the role of the SR Ca2+ release channel known as the type 1 ryanodine receptor.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle contraction is initiated by depolarization of the surface membrane (the sarcolemma) of muscle cells. Depolarization of the sarcolemma leads to the formation of cross-bridges between myosin and actin and shortening of the basic contractile unit of muscle, the sarcomere, a process known as excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. Ca2+ released from intracellular stores is the second messenger that links membrane depolarization to muscle contraction during E-C coupling. Sarcolemmal depolarization propagates down the transverse tubules (T-tubules), which are deep invaginations of the sarcolemma, and activates voltage-gated Cav1.1 Ca2+ channels (also known as L-type Ca2+ channels) on the T-tubules. Voltage-induced conformational changes in Cav1.1 activate closely apposed Ca2+ release channels known as type 1 ryanodine receptors (RyR1s) on the terminal cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (1). Ca2+ release from the SR through RyR1 channels results in a large and rapid rise in the amount of cytoplasmic Ca2+, which binds to troponin C and allows myosin and actin to form cross-bridges leading to the sliding of actin and myosin filaments with respect to each other and the shortening of the sarcomere. The result is muscle contraction and generation of force (2–5). The elucidation of the sequence of events during E-C coupling was one of the great advances in physiology in the twentieth century (6).

In conditions of prolonged muscular stress (e.g., during the running of a marathon) or in a disease such as heart failure, both of which are characterized by chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), skeletal muscle function is impaired, possibly due to altered E-C coupling. In particular, the amount of Ca2+ released from the SR during each contraction of the muscle is reduced, aberrant Ca2+ release events can occur, and Ca2+ reuptake is slowed (7–9). These observations suggest that the deleterious effects of chronic activation of the SNS on skeletal muscle might be due, at least in part, to defects in Ca2+ signaling.

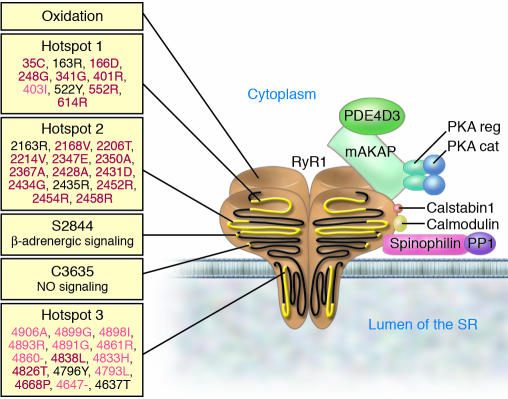

SR Ca2+ release channels form an enormous macromolecular signaling complex comprising four approximately 565-kDa RyR1 monomers and several enzymes that are targeted to the cytoplasmic domain of the RyR1 channel, including calstabin1 (also known as FKBP12), cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), and phosphodiesterase 4D3 (PDE4D3). A-kinase anchor protein (mAKAP) targets PKA and PDE4D3 to RyR1, whereas spinophilin targets PP1 to the channel (10–12) (Figure 1). The catalytic and regulatory subunits of PKA, PP1, and PDE4D3 regulate PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2843 (Ser2844 in the mouse) (7, 12). We showed that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2844 increases the sensitivity of the channel to cytoplasmic Ca2+, reduces the binding affinity of calstabin1 for RyR1, and destabilizes the closed state of the channel (7, 13). In contrast, Meissner and colleagues reported that PKA phosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2843 did not reduce the binding of calstabin1 to the channel; however, interpretation of these data is complicated by the fact that the authors did not control for the amount of calstabin1 present in the binding reactions (14). We reported that the concentration of calstabin1 in skeletal muscle is approximately 200 nM and that PKA phosphorylation of the RyR1 channel reduces the binding affinity of calstabin1 for RyR1 from approximately 100–200 nM to more than 600 nM (7). Thus, under physiologic conditions, reduction in the binding affinity of calstabin1 for RyR1, resulting from PKA phosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2843, is sufficient to substantially reduce the amount of calstabin1 present in the RyR1 complex (7). Chronic PKA hyperphosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2843 (defined as PKA phosphorylation of 3 or 4 of the 4 PKA Ser2843 sites present in each RyR1 homotetramer) results in “leaky” channels (i.e., channels prone to opening at rest), which contribute to the skeletal muscle dysfunction that is associated with persistent hyperadrenergic states such as occurs in individuals with heart failure (7). Depletion of PDE4D3 from the RyR1 complex contributes to PKA hyperphosphorylation of the RyR1 channel during chronic hyperadrenergic stress (ref. 7 and unpublished observations, A.M. Bellinger and A.R. Marks).

Figure 1. The RyR1 macromolecular complex.

RyR1 forms a macromolecular complex with PDE4D3, A-kinase anchor protein (mAKAP), the catalytic (cat) and regulatory (reg) subunits of PKA, calstabin1, calmodulin, PP1, and spinophilin. Components of the RyR1 complex are represented schematically bound to one monomer of the homotetrameric RyR1 channel. On the left, stress signals targeting RyR1 are shown, including the three hotspots on RyR1 where disease-causing mutations cluster (34, 114). MH-associated mutations are in red, CCD-associated mutations are in pink, mixed mutations or those associated with multi-minicore disease or nemaline rod disease are shown in black. –, deletion mutation.

Regulation of RyR1 by posttranslational modifications other than phosphorylation, such as by nitrosylation of free sulfhydryl groups on cysteine residues (S-nitrosylation), has been reported to increase RyR1 channel activity (15, 16). S-nitrosylation of RyR1 reduces calstabin1 binding to RyR1, and both S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation of RyR1 reduce the affinity with which calmodulin binds the channel (17). Cysteine residues in RyR1 are S-nitrosylated, S-glutathionylated, or oxidized under distinct physiological conditions (18, 19). It has been proposed that S-nitrosylation might, in some cases, protect against the inhibitory effects of oxidation (20, 21). However, it remains to be determined precisely how posttranslational modifications of cysteine residues in RyR1 regulate the function of the channel in vivo. In addition to direct S-nitrosylation of RyR1, indirect effects of NO on the channel have been reported (22). NO-dependent guanylyl cyclase–mediated generation of cGMP can activate protein kinase G, which, in turn, can phosphorylate RyR1, with functional consequences that remain to be elucidated (22).

RyR1 activity is also regulated by Ca2+ and by the 17-kDa Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin, which binds RyR1 monomers with a stoichiometry of 1:1. The Ca2+-free form of calmodulin functions as a partial agonist of RyR1 at low cytoplasmic concentrations of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) (i.e., less than 200 nM), whereas the Ca2+-bound form is an inhibitor at high [Ca2+]cyt (i.e., greater than 1 μM) (23). For a more comprehensive discussion of signaling pathways and physiological regulators of RyR1 channel function, see ref. 12.

Muscle stress

RyR1 activity is modulated by stable posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, nitrosylation, and oxidation, all of which can be downstream effects of stress-dependent signaling pathways. Repetitive, strenuous muscle contraction imposes strain and sheer forces on muscle extracellular matrix, membranes, and cytoskeleton. Such repetitively stressed muscle must also withstand cyclical changes in [Ca2+]cyt, on the order of 10-fold changes (i.e., from approximately 100 nM to greater than 1 μM with each contraction), without sustaining cell damage or death. An unresolved question, and a challenge for future investigations, is to understand how muscle cells can avoid activation of deleterious Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways (e.g., those associated with apoptosis and proteolysis) in the face of repeated elevations of [Ca2+]cyt that are known to be sufficient in certain contexts to activate cell damage and death pathways.

At a simplistic level, it is evident that over prolonged periods, skeletal muscles sustain contractile function despite mechanical and metabolic stresses because protective mechanisms exist to limit stress-induced irreversible cell damage and death (24). Indeed, actively contracting muscles experience insults ranging from small membrane tears to depletion of energy reserves without suffering irreversible damage. Thus, to assess the consequences of muscle stress, one must consider not only the kind and amount of stress imposed on the muscle but also the protective mechanisms that determine the threshold of a muscle for stress-induced damage. A number of factors affect the threshold of a muscle fiber to mechanical stress. These include the fiber type, which is reflected in the number and oxidative content of the mitochondria of the fiber; the energy reserves of the fiber; the speed and strength of the contraction of the fiber; the size of the fiber; the relation of the fiber to its neighbors; and the way the fiber is used (25). Type IIb fibers (fast, glycolytic fibers) have low aerobic mitochondrial activity and fast kinetics of contraction, whereas type I fibers (slow, aerobic fibers) have greater mitochondrial capacity and are more resistant to fatigue. The variability of the threshold of a muscle for stress-induced damage can be inferred from the observation that distinct kinds of muscle fibers and muscles are affected in specific muscle diseases. Type II fibers in large proximal muscles are most affected in Cushing syndrome (26), type IIb fibers in the lower extremities are most affected in some muscular dystrophies (27), and small extraocular muscles are most affected in mitochondrial myopathies (28). Different muscle stressors cause tissue damage in distinct ways (Table 1); some directly stress the muscle, whereas others reduce the threshold of a muscle for stress-induced damage. One general observation is that abnormalities in Ca2+ homeostasis have been reported in muscle subjected to many types of stress. In this Review, we examine the evidence implicating dysregulation of RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release in both inherited and acquired conditions of muscle dysfunction.

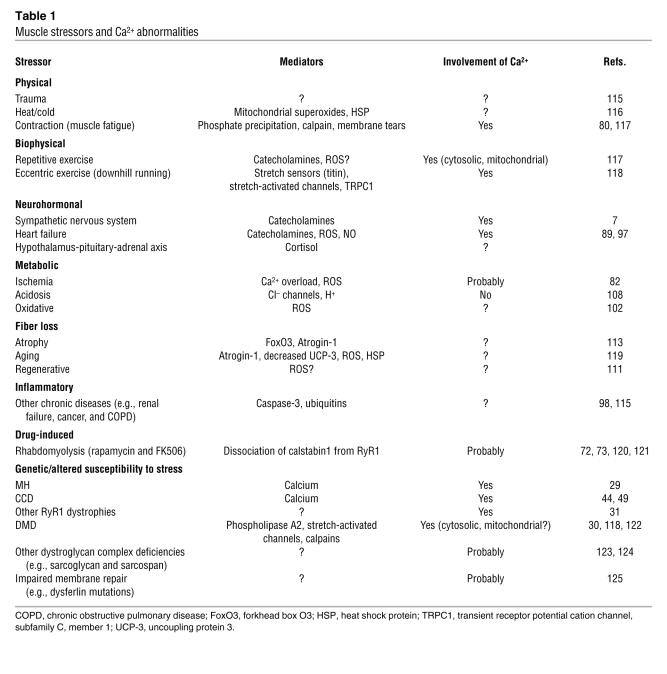

Table 1 .

Muscle stressors and Ca2+ abnormalities

Inherited stress-related muscle dysfunction has been linked to mutations in the RyR1 gene that result in altered Ca2+ release as well as to mutations in the genes encoding cytoskeletal and extracellular proteins, including those associated with muscular dystrophies, that result in increased myofiber membrane fragility (also altering Ca2+ homeostasis) (29, 30). Acquired stress-related muscle dysfunction has been linked to environmental factors and extreme exercise. This Review focuses on factors that limit exercise capacity during repetitive strenuous exercise and in chronic diseases such as heart failure. One common feature of repetitive strenuous exercise and certain chronic diseases (e.g., heart failure) is a persistent hyperadrenergic state.

Inherited forms of skeletal muscle dysfunction

Mutations in the gene encoding RyR1.

It is potentially informative to examine the consequences of missense mutations in the RyR1 gene that have been linked to skeletal myopathies, the basis for which is presumably altered Ca2+ homeostasis (31). These genetic disorders provide critically important insights into mechanisms of RyR1 dysregulation that result in impaired skeletal muscle function. The most extensively studied RyR1 mutations are those that cause malignant hyperthermia (MH), which is characterized by susceptibility to a severe, life-threatening rise in body temperature and muscle rigidity upon exposure to a fluorinated inhalation anesthetic such as halothane (29). The basis for this fatal disorder is the triggering of a rapid and sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+ in muscle due to hyperactivation of RyR1 channels (32).

Multiple MH-associated RyR1 mutations have been identified and found to cluster in three regions of RyR1, the amino terminus (aa 35–614), a central region (aa 1,787–2,458), and the carboxyl terminus (aa 4,796–4,973) (33). In general, MH mutant RyR1 channels exhibit a reduced threshold for Ca2+-dependent activation in the presence of a trigger of MH (34, 35). This causes a profound alteration in Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to metabolic catastrophe (36).

MH episodes can also in rare instances be triggered in susceptible individuals by exposure to the depolarizing muscle relaxant succinylcholine and strenuous exercise, as well as overheating in infants, suggesting that other environmental stressors can lower the activation threshold of MH mutant RyR1 channels and cause pathologic SR Ca2+ release (37, 38). It should be noted that rare mutations in the gene encoding Cav1.1 can also cause MH, suggesting that impaired coupling between Cav1.1 and RyR1 can similarly lead to increased sensitivity to RyR1-activating agents (39). Treatment for an acute MH episode currently consists of administration of dantrolene, which reduces RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release (40), although the mechanism by which it mediates this effect is not fully understood.

In contrast to MH, which presents as an acute crisis in an otherwise normal individual, another group of RyR1 mutations cause central core disease (CCD), a congenital myopathy that presents in infancy and is characterized by poor muscle tone, muscle weakness, and musculoskeletal abnormalities (41–44). A number of RyR1 mutations linked to CCD are associated with leaky RyR1 channels (44, 45). The resulting chronic leak of SR Ca2+ elevates myoplasmic Ca2+ levels, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, myofibrillar disorganization, and muscle damage (44–46). The disease is characterized by lesions in the center of type I myofibers (so-called core lesions), a deficiency of oxidative enzymes, myofibrillary disorganization, variable interstitial fibrosis, and a deficiency of type II fibers (47). CCD-associated RyR1 mutations in the pore region of RyR1 lead to uncoupling of SR Ca2+ release from excitation of the sarcolemma (48).

There is no clear division between MH and CCD, either clinically or in terms of RyR1 function (31, 33, 45), and interestingly, some RyR1 mutations have been linked to a combined MH and CCD phenotype (31). A comprehensive explanation for the phenotypic differences between MH and CCD is currently lacking. However, it has been suggested that a functional classification based on the leakiness of RyR1 might be informative, with modest “compensated leak” (i.e., a Ca2+ leak that is balanced by Ca2+ reuptake at steady state) resulting in an MH phenotype and “decompensated leak” (i.e., a Ca2+ leak that is not effectively balanced by Ca2+ reuptake) resulting in a mixed MH and CCD phenotype (33, 49).

To complicate matters further, rare recessive mutations in RyR1 have been identified in families presenting with a spectrum of myopathies. These myopathies range from multi-minicore disease, which is characterized by muscle weakness associated with multiple areas of myofibrillary disorganization and loss of oxidative enzymes similar to CCD (50), to a phenotype characterized by more severe generalized muscle weakness that is possibly associated with defects in either the assembly or stability of RyR1 leading to a reduction in RyR1 SR Ca2+ release channels in the SR (31).

Mutations that cause muscular dystrophies.

Altered Ca2+ homeostasis is probably central to the pathogenesis of the most common forms of muscular dystrophy caused by either a lack or only partial expression of dystrophin, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), respectively. Absence of dystrophin leads to disruption of a large dystroglycan complex that spans the muscle membrane and connects the intracellular actin cytoskeleton to the ECM. Disruption of the dystroglycan complex causes increased membrane fragility and indirectly impairs Ca2+ homeostasis (51, 52), although the precise mechanisms involved in the latter remain to be fully elucidated. Increased flux of Ca2+ across the sarcolemma and activation of cell death pathways has been proposed as a mechanism that contributes to the pathogenesis of DMD (52). Interestingly, alterations in SR Ca2+ stores and release have recently been observed in the mdx (dystrophin-deficient) mouse model of DMD (30, 53–55). Increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake resulting in cell death has been proposed as a contributing factor to the muscle weakness associated with DMD (53). How alterations in RyR1 function might contribute to abnormalities in Ca2+ homeostasis in muscular dystrophies remains to be determined.

Acquired muscle stress

SR Ca2+ release and skeletal muscle fatigue.

A defect in E-C coupling that resulted in a reduction in the amount of Ca2+ released from the SR during a contraction could impair muscle contraction and force generation. In 1963, Eberstein and Sandow suggested that inhibition of Ca2+ release contributes to muscle fatigue (56). Reduction in SR Ca2+ release during repeated tetanic stimulation occurs in single muscle fibers from mice (9, 57), single whole (58) and cut (59) fibers from frogs, whole muscle from bullfrogs (60), and rats run to exhaustion (61). The decrement in force production resulting from fatiguing stimulation can be largely, though temporarily, reversed by the RyR1 activator caffeine (62), although administering sufficient caffeine to a living animal to improve muscle fatigue would probably be toxic. Moreover, T-tubule function is intact and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity normal during fatigue (63), suggesting that indeed SR Ca2+ release defects play a role in muscle fatigue. Preceding the decline in SR Ca2+ release during repetitive tetanic stimulation, characteristic changes in Ca2+ cycling occur, including a prolongation of the decay phase of Ca2+ release (which is determined by the rate of SR Ca2+ reuptake) and a progressive rise in resting [Ca2+]cyt (62). Prolongation of the decay phase of Ca2+ release is consistent with continued release of Ca2+ after the initial opening event and with impaired function of the SR Ca2+ reuptake pump, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1 (SERCA1a), possibly due to oxidation (64). Elevated [Ca2+]cyt has been suggested as another mechanism that might inhibit SR Ca2+ release during fatigue, perhaps through impaired coupling between Cav1.1 and RyR1 or through direct inhibitory effects on RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release (65, 66).

One argument against purely metabolic mechanisms of muscle fatigue, and in favor of an important role for defects in SR Ca2+ release, is the finding that after strenuous exercise, human muscle exhibits a sustained depression in force generation that can persist for up to several days (67). This period of time corresponds to the period over which prolonged inhibition of SR Ca2+ release is observed (68). A component of the decrease in SR Ca2+ release during fatiguing exercise can be explained by a reduction in the free Ca2+ in the SR due to precipitation of Ca2+ phosphate salts (69, 70).

Strenuous fatiguing exercise induces spontaneous Ca2+ release events through clusters of RyR1 channels at a higher frequency than observed in either resting muscle or mildly exercised muscle (71). As the frequency of these quantal Ca2+ release events, known as sparks, depends on RyR1 activity, these data suggest that RyR1 channels may be leaky in fatigued muscle.

The association of calstabin1 with RyR1 stabilizes the closed state of the channel (72) and facilitates coupled gating between neighboring channels (13). Dissociation of calstabin1 from RyR1 has been associated with a loss of depolarization-induced contraction in intact skeletal muscle (73). Depletion of calstabin1 from the RyR1 channel complex can impair E-C coupling with reduced maximal voltage-gated SR Ca2+ release (without a change in SR Ca2+ store content) (74). Genetic deletion of calstabin1 in the mouse induced no gross histological or developmental defect in skeletal muscle, although severe developmental cardiac defects were observed that resulted in heart failure (75). Skeletal muscle–specific deletion of calstabin1 resulted in reduced Cav1.1-evoked SR Ca2+ release and increased Cav1.1 current in isolated myotubes (76). The extensor digitorum longus muscle, but neither the soleus muscle nor diaphragm, had reduced muscle strength at higher stimulation frequencies (76). It has also been reported that dissociation of calstabin1 from RyR1 relieves channel inhibition by Mg2+, H+, and high [Ca2+]cyt (73, 76). In general, as is the case with many gene deletion models, compensatory adaptations in the animals might account for the relatively modest phenotype observed in the absence of calstabins.

The myosin ATPase and SERCA1a consume a large fraction of the energy expended by muscle cells (78, 79). Indeed, the energy consumption of skeletal muscle cells can increase 100-fold during high-intensity exercise (80). The energetics of Ca2+ cycling is a principal characteristic of muscle fibers and varies among fiber types, affecting regulation of metabolism, cell growth and damage, and cellular stress. One potential deleterious consequence of SR Ca2+ leak through RyR1 channels could be to increase ATP consumption due to compensatory SERCA1a ATPase activity (81).

In addition, skeletal muscle contains calpains, Ca2+-activated neutral proteases that are implicated in numerous muscle damage pathways (82). Calpains contribute to proteolytic cleavage of cytoskeletal and Ca2+-handling proteins (83). Inhibition of calpains in a murine dystrophic model reduced muscle damage (84). It is not known whether SR Ca2+ release via leaky RyR1 channels activates calpains.

Skeletal muscle manifestations of heart failure.

During heart failure, patients experience profoundly impaired exercise capacity that cannot be explained by the degree of cardiac dysfunction (85, 86). The fatigue can be so marked, and its correlation with decreased cardiac output and peripheral arterial perfusion so poor, that it has been hypothesized that there is an intrinsic defect in the skeletal muscle during heart failure (7, 87). The effects of heart failure on intrinsic skeletal muscle function and Ca2+ handling have been assessed in animal models at several levels, from whole muscle to isolated single fibers, with relatively consistent results. In muscle bundles from rats with heart failure, reduced force production was accompanied by reduced quantitative Ca2+ release during contraction, prolonged decay phase of Ca2+ release, and accelerated fatigue (88, 89). Slowed kinetics of Ca2+ release and reuptake were also observed in single type I and type II fibers (8) and in in situ perfused muscles (90) from rats with heart failure, without substantial changes in SR or sarcolemmal protein expression.

In heart failure, individual spontaneous Ca2+ sparks exhibit an increase in temporal and spatial width with an associated decrease in amplitude compared with the spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in the skeletal muscle of healthy animals (7, 89). In addition, an increased frequency of wavelets, nonpropagating Ca2+ release events larger than sparks, was observed (7). In planar lipid bilayer experiments, single skeletal muscle RyR1 channels from animals with heart failure were more sensitive to activation by nanomolar concentrations of Ca2+, indicating that the channels are leaky (91). In summary, skeletal muscle from animals with heart failure demonstrates increased Ca2+ spark frequency, decreased Ca2+ spark amplitude, and increased Ca2+ spark duration consistent with leaky SR Ca2+ release and with decreased SR Ca2+ content.

Heart failure is associated with high levels of circulating catecholamines and with chronic activation of adrenergic signaling pathways in many tissues (92). Acute β-adrenergic signaling in the heart increases contractility and heart rate (93), and in skeletal muscle, it increases the force of contraction, regulates blood flow, and alters glucose metabolism (94, 95). Chronic adrenergic signaling, however, can lead to maladaptive activation of intracellular stress pathways in both the heart and skeletal muscle, impairing muscle function and even leading to myocyte death (96). PKA hyperphosphorylation of RyR1 at Ser2843 and subsequent dissociation of calstabin1 from RyR1 destabilizes the closed state of the RyR1 channel, resulting in leaky channels (7). In rats with heart failure, the level of RyR1 PKA phosphorylation correlates with early fatigue in isolated soleus muscle during repetitive tetanic contractions (7). Furthermore, preventing the dissociation of calstabin1 from the RyR1 complex and fixing the RyR1 channel leak in heart failure skeletal muscle using novel small molecules (known as rycals) can improve muscle fatigue in mice with heart failure (97). These data have led us to propose (97) that heart failure is a generalized E-C coupling myopathy in which PKA hyperphosphorylation of RyR2 and RyR1 results in Ca2+ leak in cardiac and skeletal muscle, impairing cardiac function and exercise capacity (Figure 2).

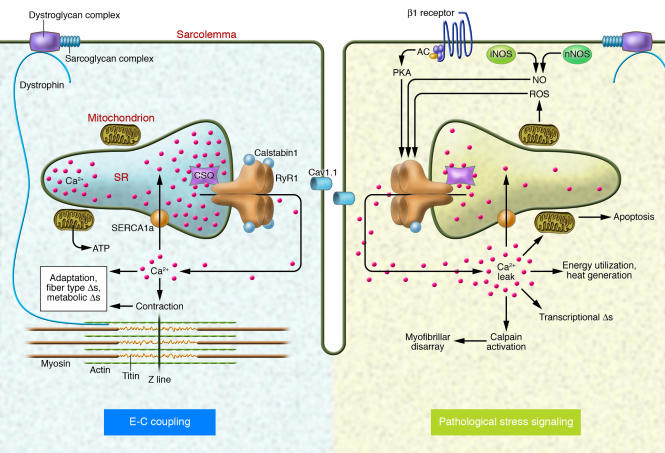

Figure 2. Stress responses in skeletal muscle during E-C coupling.

Depolarization of the T-tubule membrane activates Cav1.1, triggering SR Ca2+ release through RyR1 and leading to sarcomere contraction, a process known as E-C coupling. Intracellular signaling pathways activated in skeletal muscle by pathological stress affect RyR1 function and alter E-C coupling. Stress-induced RyR1 dysfunction can result in SR Ca2+ leak, which potentially activates numerous Ca2+-dependent cellular damage mechanisms. AC, adenylate cyclase.

Other hormones and inflammatory mediators, including Ang II, TNF-α, ROS, and NO, have been implicated in the skeletal muscle defect in heart failure (98–100). Increases in ROS in hind-limb muscles from failing animals (101) and resultant oxidation of myofibrillar proteins (102) as well as other targets have been reported. Interestingly, the frequency of Ca2+ sparks in permeabilized skeletal muscle inversely correlates with the mitochondrial content and redox potential of the muscle fiber, suggesting that ROS scavenging mechanisms in the mitochondria might play an important protective role in preventing pathological Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle (103), perhaps due to protection from oxidation of RyR1. Changes in expression of eNOS (also known as NOS1) have been reported, and skeletal muscle expression of iNOS (also known as NOS2) is elevated in heart failure (99). ROS and NO have been shown to modify RyR1 channel function (15, 19, 20, 22) and are potentially implicated in the Ca2+ handling defects in heart failure. Further studies are required to identify direct roles for ROS and NO in altering RyR1 function and inducing skeletal muscle dysfunction in heart failure.

Leaky RyR1: a common mechanism for stress-induced impairment of exercise capacity?

Are there similar mechanisms underlying the impaired exercise capacity of heart failure patients and of healthy individuals during prolonged strenuous exercise? Lunde et al. suggested that although Na+ and K+ accumulation contributes to muscle fatigue during exercise in healthy individuals, abnormalities in Ca2+ release from the SR might play a more important role in limiting exercise capacity in heart failure patients (104). Recent data have suggested that “classic” causes of muscle fatigue (e.g., lactic acidosis) (105) might not contribute to muscle fatigue (106–108). In the context of exploring alternative explanations for fatigue and impaired exercise capacity, we have focused on the possibility that, in heart failure patients and athletes participating in prolonged strenuous exercise, sustained activation of the β-adrenergic system could have similar pathophysiological effects on SR Ca2+ release (Figure 3). Indeed, both heart failure and strenuous exercise are characterized by an elevation in circulating catecholamines and increased production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (92, 99, 102).

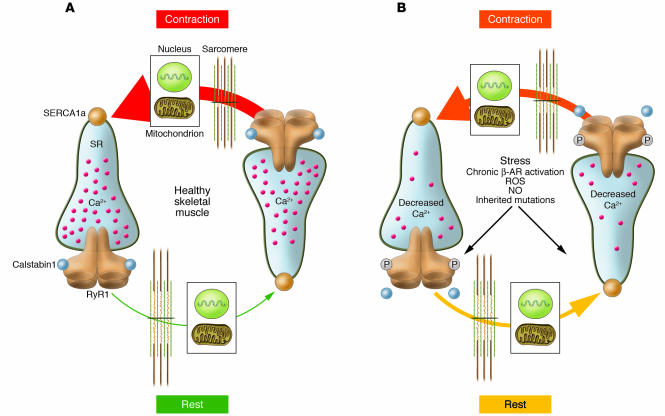

Figure 3. Ca2+ cycling in normal and stressed muscle.

(A) In healthy muscle, Ca2+ release occurs in a coordinated fashion during contraction, and [Ca2+]cyt is low at rest. Organelles (e.g., the nucleus and mitochondria) sense changes in [Ca2+]cyt, which regulates cellular functions including transcription and energy metabolism. (B) Stress-induced PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR1 alters the way skeletal muscle handles Ca2+ during contraction and relaxation. PKA hyperphosphorylation of RyR1, resulting in calstabin1 depletion from the channel complex, leads to an SR Ca2+ leak in the resting muscle, potentially influencing nuclear and mitochondrial function. Ca2+ leak also decreases SR load, and less Ca2+ is available for release during contraction. β-AR, β-adrenergic receptor.

There are important and obvious differences between healthy athletes and heart failure patients. However, heart failure and strenuous exercise are both characterized by reduced SR Ca2+ release (89, 109). Leaky RyR1 channels have been shown in heart failure skeletal muscle (7, 71) and in dystrophic muscle (71). In exercise, Ca2+-dependent proteolytic pathways mediated by calpains are also activated (110). That similar mechanisms are activated in stress conditions that primarily (muscle fatigue) or secondarily (heart failure) affect skeletal muscle suggests that therapeutic strategies designed to repair defective Ca2+ signaling might improve exercise capacity in heart failure patients and in patients with other chronic diseases associated with impaired exercise capacity (e.g., cancer, AIDS, renal failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]).

Therapeutic implications

Efforts to develop therapeutics that improve exercise capacity have met with limited success. A big focus has been to activate muscle regeneration pathways, either by recruiting bone marrow–derived muscle progenitor cells or by inducing satellite cells (resident in mature skeletal muscle) to proliferate (111, 112). Another important approach has been to inhibit the muscle atrophy that occurs in aging and in chronic diseases (113). We have explored an alternative approach focused on limiting the damage that might be caused by a pathologic leak of Ca2+ from the SR. The contribution of leaky SR Ca2+ release to stress-induced muscle damage is the subject of ongoing studies in our laboratory. We propose that rycals, which inhibit the SR Ca2+ leak by preventing the depletion of calstabin1 from the RyR1 complex and stabilize the closed state of the channel, might reduce the myofiber damage and death associated with stress signaling pathways targeting RyR1 (Table 1).

In heart failure, the quality of life of patients is limited by skeletal muscle fatigue, which impairs exercise capacity and might contribute to shortness of breath (due to fatigue of the diaphragm). Inhibiting SR Ca2+ leak through RyR1 could be a novel therapeutic approach to improve exercise capacity and decrease shortness of breath in patients with heart failure. The fatigue associated with other chronic diseases might also be ameliorated by reducing SR Ca2+ leak, although this is highly speculative at this point. In CCD, which is caused by RyR1 mutations that cause leaky channels, fixing the leak in RyR1 channels with a rycal could reduce myofiber death and sarcopenia. Since this debilitating disease currently has no treatment, stabilization of RyR1 function could provide a potentially life-saving therapy.

Summary

Insights gained from the study of genetic disorders such as MH suggest that leaky RyR1 channels can cause skeletal muscle pathology. RyR1 leak also occurs in chronic diseases associated with stress, such as heart failure, as a consequence of persistent PKA hyperphosphorylation of the channel and depletion of the stabilizing protein calstabin1. In other genetic disorders, such as DMD, secondary defects in RyR1 might contribute to or modify disease severity by altering Ca2+ homeostasis.

Future studies will address such questions as: What is the role, if any, of leaky RyR1 channels in limiting exercise in healthy individuals? Can targeting leaky RyR1 channels improve exercise capacity in healthy individuals and in patients with chronic diseases? To what extent is Ca2+ leak responsible for activating Ca2+-dependent downstream signaling pathways resulting in muscle damage and death?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: [Ca2+]cyt, cytoplasmic concentration of Ca2+; CCD, central core disease; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; E-C, excitation-contraction; MH, malignant hyperthermia; PDE4D3, phosphodiesterase 4D3; PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase; PP1, protein phosphatase 1; RyR1, type 1 ryanodine receptor; SERCA1a, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; T-tubule, transverse tubule.

Conflict of interest: A.R. Marks is on the scientific advisory board and owns shares in ARMGO Pharma Inc., a start-up company that is developing novel therapeutics targeting the ryanodine receptor for heart failure, sudden cardiac death, and muscle fatigue. A.R. Marks is supported by a grant from DARPA.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 118:445–453 (2008). doi:10.1172/JCI34006.

References

- 1.Tanabe T., Beam K.G., Adams B.A., Niidome T., Numa S. Regions of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor critical for excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1990;346:567–569. doi: 10.1038/346567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fill M., Copello J.A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Serratos H., Valle-Aguilera R., Lathrop D.A., Garcia M.C. Slow inward calcium currents have no obvious role in muscle excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1982;298:292–294. doi: 10.1038/298292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rios E., Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;325:717–720. doi: 10.1038/325717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall W.A. Excitation-contraction coupling in vertebrate skeletal muscle: a tale of two calcium channels. Cell. 1991;64:871–874. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90309-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebashi S. Excitation-contraction coupling and the mechanism of muscle contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1991;53:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiken S., et al. PKA phosphorylation activates the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) in skeletal muscle: defective regulation in heart failure. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:919–928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunde P.K., et al. Contraction and intracellular Ca(2+) handling in isolated skeletal muscle of rats with congestive heart failure. Circ. Res. 2001;88:1299–1305. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westerblad H., Allen D.G. Changes of myoplasmic calcium concentration during fatigue in single mouse muscle fibers. J. Gen. Physiol. 1991;98:615–635. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeshima H., et al. Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1989;339:439–445. doi: 10.1038/339439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks A.R., et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the ryanodine receptor/junctional channel complex cDNA from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:8683–8687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalk R., Lehnart S.E., Marks A.R. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.094237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marx S.O., Ondrias K., Marks A.R. Coupled gating between individual skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors). Science. 1998;281:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stange M., Xu L., Balshaw D., Yamaguchi N., Meissner G. Characterization of recombinant skeletal muscle (Ser-2843) and cardiac muscle (Ser-2809) ryanodine receptor phosphorylation mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51693–51702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eu J.P., Xu L., Stamler J.S., Meissner G. Regulation of ryanodine receptors by reactive nitrogen species. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;57:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun J., Xin C., Eu J.P., Stamler J.S., Meissner G. Cysteine-3635 is responsible for skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor modulation by NO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:11158–11162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201289098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aracena P., Tang W., Hamilton S., Hidalgo C. Effects of S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation on calmodulin binding to triads and FKBP12 binding to type 1 calcium release channels. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:870–881. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghdasi B., Zhang J.Z., Wu Y., Reid M.B., Hamilton S.L. Multiple classes of sulfhydryls modulate the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3739–3748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aracena P., Sanchez G., Donoso P., Hamilton S.L., Hidalgo C. S-glutathionylation decreases Mg2+ inhibition and S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ activation of RyR1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42927–42935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favero T.G., Zable A.C., Bowman M.B., Thompson A., Abramson J.J. Metabolic end products inhibit sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and [3H]ryanodine binding. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995;78:1665–1672. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aghdasi B., Reid M.B., Hamilton S.L. Nitric oxide protects the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel from oxidation induced activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25462–25467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamler J.S., Meissner G. Physiology of nitric oxide in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:209–237. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripathy A., Xu L., Mann G., Meissner G. Calmodulin activation and inhibition of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor). Biophys. J. 1995;69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79880-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fluck M. Functional, structural and molecular plasticity of mammalian skeletal muscle in response to exercise stimuli. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:2239–2248. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitts R.H. Cellular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Physiol. Rev. 1994;74:49–94. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olafsson E., Jones H.R.J., Guay A.T., Thomas C.B. Myopathy of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome: a review of the clinical and electromyographic features in 8 patients. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:692–693. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webster C., Silberstein L., Hays A.P., Blau H.M. Fast muscle fibers are preferentially affected in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1988;52:503–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoser B.G.H., Pongratz D. Extraocular mitochondrial myopathies and their differential diagnoses. Strabismus. 2006;14:107–113. doi: 10.1080/09273970600701218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLennan D.H., Phillips M.S. Malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1992;256:789–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1589759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robert V., et al. Alteration in calcium handling at the subcellular level in mdx myotubes. . J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:4647–4651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H., et al. Molecular mechanisms and phenotypic variation in RYR1-related congenital myopathies. Brain. 2007;130:2024–2036. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mickelson J.R., Louis C.F. Malignant hyperthermia: excitation-contraction coupling, Ca2+ release channel, and cell Ca2+ regulation defects. Physiol. Rev. 1996;76:537–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Priori S.G., Napolitano C. Cardiac and skeletal muscle disorders caused by mutations in the intracellular Ca2+ release channels. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2033–2038. doi: 10.1172/JCI25664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mickelson J.R., et al. Abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptor in malignant hyperthermia. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:9310–9315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter M., Schleithoff L., Deufel T., Lehmann-Horn F., Herrmann-Frank A. Functional characterization of a distinct ryanodine receptor mutation in human malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:5256–5260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Censier K., Urwyler A., Zorzato F., Treves S. Intracellular calcium homeostasis in human primary muscle cells from malignant hyperthermia-susceptible and normal individuals. Effect of overexpression of recombinant wild-type and Arg163Cys mutated ryanodine receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1233–1242. doi: 10.1172/JCI993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denborough M. Malignant hyperthermia. Lancet. 1998;352:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tobin J.R., Jason D.R., Challa V.R., Nelson T.E., Sambuughin N. Malignant hyperthermia and apparent heat stroke. JAMA. 2001;286:168–169. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart S.L., Hogan K., Rosenberg H., Fletcher J.E. Identification of the Arg1086His mutation in the alpha subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel (CACNA1S) in a North American family with malignant hyperthermia. Clin. Genet. 2001;59:178–184. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.590306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause T., Gerbershagen M.U., Fiege M., Weisshorn R., Wappler F. Dantrolene — a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabello A., Ricoy-Campo J.R. Congenital myopathies. Rev. Neurol. 2003;37:779–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quane K.A., et al. Mutations in the ryanodine receptor gene in central core disease and malignant hyperthermia. Nat. Genet. 1993;5:51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., et al. A mutation in the human ryanodine receptor gene associated with central core disease. Nat. Genet. 1993;5:46–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tilgen N., et al. Identification of four novel mutations in the C-terminal membrane spanning domain of the ryanodine receptor 1: association with central core disease and alteration of calcium homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2879–2887. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong J., McCarthy T.V., MacLennan D.H. Measurement of resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and Ca2+ store size in HEK-293 cells transfected with malignant hyperthermia or central core disease mutant Ca2+ release channels. . J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:693–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gommans I.M., Vlak M.H., de Haan A., van Engelen B.G. Calcium regulation and muscle disease. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2002;23:59–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1019984714528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu S., et al. Central core disease is due to RYR1 mutations in more than 90% of patients. Brain. 2006;129:1470–1480. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avila G., O’Connell K.M., Dirksen R.T. The pore region of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor is a primary locus for excitation-contraction uncoupling in central core disease. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;121:277–286. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dirksen R.T., Avila G. Distinct effects on Ca2+ handling caused by malignant hyperthermia and central core disease mutations in RyR1. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3193–3204. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mathews K.D., Moore S.A. Multiminicore myopathy, central core disease, malignant hyperthermia susceptibility, and RYR1 mutations: one disease with many faces? Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:27–29. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumura K., Ervasti J.M., Ohlendieck K., Kahl S.D., Campbell K.P. Association of dystrophin-related protein with dystrophin-associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature. 1992;360:588–591. doi: 10.1038/360588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deconinck N., Dan B. Pathophysiology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current hypotheses. . Pediatr. Neurol. 2007;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plant D.R., Lynch G.S. Depolarization-induced contraction and SR function in mechanically skinned muscle fibers from dystrophic mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C522–C528. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woods C.E., Novo D., DiFranco M., Vergara J.L. The action potential-evoked sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release is impaired in mdx mouse muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2004;557:59–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woods C.E., Novo D., DiFranco M., Capote J., Vergara J.L. Propagation in the transverse tubular system and voltage dependence of calcium release in normal and mdx mouse muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2005;568:867–880. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eberstein, A., and Sandow, A. 1963. Fatigue mechanisms in muscle fibers. E. Gutman, and P. Hink, editors. In Effect of use and disuse on neuromuscular functions. Elsevier. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allen D., Lee J., Westerblad H. Intracellular calcium and tension during fatigue in isolated single muscle fibres from Xenopus laevis. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 1989;415:433–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westerblad H., Lee J.A., Lamb A.G., Bolsover S.R., Allen D.G. Spatial gradients of intracellular calcium in skeletal muscle during fatigue. Pflugers Arch. 1990;415:734–740. doi: 10.1007/BF02584013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gyorke S. Effects of repeated tetanic stimulation on excitation-contraction coupling in cut muscle fibers of the frog. J. Physiol. 1993;464:699–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baker A.J., Longuemare M.C., Brandes R., Weiner M.W. Intracellular tetanic calcium signals are reduced in fatigue of whole skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C577–C582. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Favero T.G., Pessah I.N., Klug G.A. Prolonged exercise reduces Ca2+ release in rat skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Pflugers Arch. 1993;422:472–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00375074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allen D.G., Westerblad H. Role of phosphate and calcium stores in muscle fatigue. . J. Physiol. 2001;536:657–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Westerblad H., Duty S., Allen D.G. Intracellular calcium concentration during low-frequency fatigue in isolated single fibers of mouse skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;75:382–388. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.1.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scherer N.M., Deamer D.W. Oxidative stress impairs the function of sarcoplasmic reticulum by oxidation of sulfhydryl groups in the Ca2+-ATPase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1986;246:589–601. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chin E.R., Allen D.G. The role of elevations in intracellular [Ca2+] in the development of low frequency fatigue in mouse single muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1996;491:813–824. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamb G.D., Junankar P.R., Stephenson D.G. Raised intracellular [Ca2+] abolishes excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres of rat and toad. J. Physiol. 1995;489:349–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edwards R.H., Hill D.K., Jones D., Merton P.A. Fatigue of long duration in human skeletal muscle after exercise. J. Physiol. 1977;272:769–778. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westerblad H., Bruton J.D., Allen D.G., Lannergren J. Functional significance of Ca2+ in long-lasting fatigue of skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;83:166–174. doi: 10.1007/s004210000275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fryer M.W., Owen V.J., Lamb G.D., Stephenson D.G. Effects of creatine phosphate and P(i) on Ca2+ movements and tension development in rat skinned skeletal muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1995;482:123–140. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Westerblad H., Allen D.G. The effects of intracellular injections of phosphate on intracellular calcium and force in single fibres of mouse skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch. 1996;431:964–970. doi: 10.1007/s004240050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X., et al. Uncontrolled calcium sparks act as a dystrophic signal for mammalian skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:525–530. doi: 10.1038/ncb1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brillantes A.B., et al. Stabilization of calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function by FK506-binding protein. Cell. 1994;77:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lamb G.D., Stephenson D.G. Effects of FK506 and rapamycin on excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. . J. Physiol. 1996;494:569–576. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Avila G., Lee E.H., Perez C.F., Allen P.D., Dirksen R.T. FKBP12 binding to RyR1 modulates excitation-contraction coupling in mouse skeletal myotubes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22600–22608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shou W., et al. Cardiac defects and altered ryanodine receptor function in mice lacking FKBP12. Nature. 1998;391:489–492. doi: 10.1038/35146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tang W., et al. Altered excitation-contraction coupling with skeletal muscle specific FKBP12 deficiency. FASEB J. 2004;18:1597–1599. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1587fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Favero T.G. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and muscle fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;87:471–483. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rall J. Energetics of Ca2+ cycling during skeletal muscle contraction. Fed. Proc. 1982;41:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wahr P.A., Rall J.A. Role of calcium and cross bridges in determining rate of force development in frog muscle fibers. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1997;272:C1664–C1671. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.5.C1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Westerblad H., Allen D.G. Recent advances in the understanding of skeletal muscle fatigue. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2002;14:648–652. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer M., et al. Frequency-dependence of myocardial energetics in failing human myocardium as quantified by a new method for the measurement of oxygen consumption in muscle strip preparations. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:1459–1470. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gissel H. The role of Ca2+ in muscle cell damage. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1066:166–180. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tidball J.G., Spencer M.J. Calpains and muscular dystrophies. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2000;32:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spencer M.J., Mellgren R.L. Overexpression of a calpastatin transgene in mdx muscle reduces dystrophic pathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2645–2655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Minotti J.R., et al. Impaired skeletal muscle function in patients with congestive heart failure. Relationship to systemic exercise performance. . J. Clin. Invest. 1991;88:2077–2082. doi: 10.1172/JCI115537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sullivan M.J., Hawthorne M.H. Exercise intolerance in patients with chronic heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1995;38:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(05)80011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Minotti J.R., et al. Skeletal muscle response to exercise training in congestive heart failure. . J. Clin. Invest. 1990;86:751–758. doi: 10.1172/JCI114771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Perreault C.L., et al. Alterations in contractility and intracellular Ca2+ transients in isolated bundles of skeletal muscle fibers from rats with chronic heart failure. Circ. Res. 1993;73:405–412. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ward C.W., et al. Defects in ryanodine receptor calcium release in skeletal muscle from post-myocardial infarct rats. FASEB J. 2003;17:1517–1519. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1083fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lunde P.K., Verburg E., Eriksen M., Sejersted O.M. Contractile properties of in situ perfused skeletal muscles from rats with congestive heart failure. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 2002;540:571–580. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Szigeti G.P., et al. Alterations in the calcium homeostasis of skeletal muscle from postmyocardial infarcted rats. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0298-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lefkowitz R.J., Rockman H.A., Koch W.J. Catecholamines, cardiac beta-adrenergic receptors, and heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:1634–1637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fozzard H.A. Heart: excitation-contraction coupling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1977;39:201–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.39.030177.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Viguerie N., et al. In vivo epinephrine-mediated regulation of gene expression in human skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:2000–2014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saltin B. Capacity of blood flow delivery to exercising skeletal muscle in humans. Am. J. Cardiol. 1988;62:30E–35E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(88)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tan L.B., Burniston J.G., Clark W.A., Ng Y., Goldspink D.F. Characterization of adrenoceptor involvement in skeletal and cardiac myotoxicity Induced by sympathomimetic agents: toward a new bioassay for beta-blockers. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2003;41:518–525. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wehrens X.H., et al. Enhancing calstabin binding to ryanodine receptors improves cardiac and skeletal muscle function in heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:9607–9612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500353102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Supinski G., Callahan L.A. Free radical mediated skeletal muscle dysfunction in inflammatory conditions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:2056–2063. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01138.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Riede U.N., Förstermann U., Drexler H. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998;32:964–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shah K.R., Ganguly P.K., Netticadan T., Arneja A.S., Dhalla N.S. Changes in skeletal muscle SR Ca2+ pump in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction are prevented by angiotensin II blockade. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2004;82:438–447. doi: 10.1139/y04-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tsutsui H., et al. Enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species in the limb skeletal muscles from a murine infarct model of heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:134–136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dalla L.L., et al. Skeletal muscle myofibrillar protein oxidation in heart failure and the protective effect of Carvedilol. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;38:803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Isaeva E.V., Shkryl V.M., Shirokova N. Mitochondrial redox state and Ca2+ sparks in permeabilized mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2005;565:855–872. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lunde P.K., Verburg E., Vollestad N.K., Sejersted O.M. Skeletal muscle fatigue in normal subjects and heart failure patients. Is there a common mechanism? Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1998;162:215–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.0343f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hill A.V., Kupalov P. Anaerobic and aerobic activity in isolated muscle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1929;105:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Andrews M.A., Godt R.E., Nosek T.M. Influence of physiological L(+)-lactate concentrations on contractility of skinned striated muscle fibers of rabbit. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;80:2060–2065. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.6.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dutka T.L., Lamb G.D. Effect of lactate on depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in mechanically skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C517–C525. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pedersen T.H., Nielsen O.B., Lamb G.D., Stephenson D.G. Intracellular acidosis enhances the excitability of working muscle. Science. 2004;305:1144–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.1101141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gomez A.M., et al. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;276:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Belcastro A.N. Skeletal muscle calcium-activated neutral protease (calpain) with exercise. . J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:1381–1386. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.3.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Charge S.B., Rudnicki M.A. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cossu G., Sampaolesi M. New therapies for muscular dystrophy: cautious optimism. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sandri M., et al. PGC-1{alpha} protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jurkat-Rott K., Lehmann-Horn F. Muscle channelopathies and critical points in functional and genetic studies. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2000–2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI25525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Du J., et al. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:115–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zuo L., Christofi F.L., Wright V.P., Bao S., Clanton T.L. Lipoxygenase-dependent superoxide release in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;97:661–668. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00096.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rudolf R., Mongillo M., Magalhaes P.J., Pozzan T. In vivo monitoring of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria of mouse skeletal muscle during contraction. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:527–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Allen D.G., Whitehead N.P., Yeung E.W. Mechanisms of stretch-induced muscle damage in normal and dystrophic muscle: role of ionic changes. . J. Physiol. (Lond.). 2005;567:723–735. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Doran P., Gannon J., O’Connell K., Ohlendieck K. Aging skeletal muscle shows a drastic increase in the small heat shock proteins alphaB-crystallin/HspB5 and cvHsp/HspB7. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 2007;86:629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brooksbank R.L., Badenhorst M.E., Isaacs H., Savage N. Treatment of normal skeletal muscle with FK506 or rapamycin results in halothane-induced muscle contracture. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:693–698. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199809000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ahern G.P., Junankar P.R., Dulhunty A.F. Subconductance states in single-channel activity of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors after removal of FKBP12. Biophys. J. 1997;72:146–162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yeung E.W., et al. Effects of stretch-activated channel blockers on [Ca2+]i and muscle damage in the mdx mouse. J. Physiol. 2005;562:367–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Peter A.K., Miller G., Crosbie R.H. Disrupted mechanical stability of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex causes severe muscular dystrophy in sarcospan transgenic mice. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:996–1008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Michele D.E., et al. Post-translational disruption of dystroglycan-ligand interactions in congenital muscular dystrophies. Nature. 2002;418:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bansal D., et al. Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2003;423:168–172. doi: 10.1038/nature01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]