Abstract

Polarization of the C. elegans embryo depends on the sperm-contributed centrosome, which cues a retraction of the actomyosin cortex to the opposite end of the embryo. New evidence reveals that the sperm donates a second polarizing cue that may locally relax the actomyosin cortex near the point of sperm entry.

One of the first job most animals tackle is breaking symmetry, as initially symmetrical eggs become embryos that will need to develop a distinct front end and back end. C. elegans has been a popular model for investigating symmetry breaking using a diverse array of experimental tools, including tools of genetics, molecular biology, live microscopic imaging and computational modeling. New work is beginning to fill longstanding gaps in the explanation of how symmetry is broken in the C. elegans embryo.

Early work on C. elegans embryos used genetic methods to identify many of the critical regulators of symmetry breaking, most notably the PAR proteins, which have since been found to be highly conserved regulators of cell polarity (see Schneider and Bowerman, 2003 for review). Certain PARs, including PAR-2, localize to the posterior end of the one-cell stage, while the other PARs, including PAR-3 and PAR-6, localize to the anterior end. Both the anterior and the posterior PAR proteins are essential for localization of cell fate determinants and spindle positioning during the first cell division. When the PAR proteins’ functions are disrupted, the embryo remains symmetrical and fails to develop normally.

What acts upstream to localize the PAR proteins to distinct domains? Manipulating the location of sperm entry showed that the sperm carries the cue that polarizes the embryo. Further experiments demonstrated that the sperm nucleus is dispensable for polarization (see Schneider and Bowerman, 2003 for review). Maturation of the sperm derived centrosome is essential for polarization (Cowan and Hyman, 2004; O’Connell et al., 2000), suggesting a centrosome or microtubule driven mechanism, although conflicting results have left uncertain the requirement for microtubules in polarization (Cowan and Hyman, 2004; Sonneville and Gonczy, 2004; Wallenfang and Seydoux, 2000).

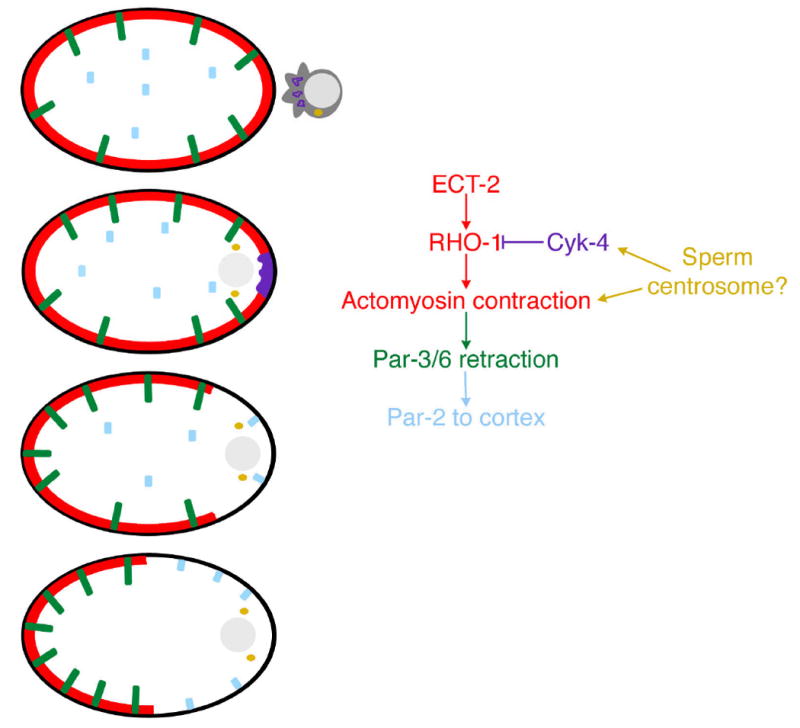

Several recent advances have shed light on how a sperm-derived cue may polarize the embryo (Munro et al., 2004). A network of actin and myosin II forms at the cortex of the egg. After fertilization and completion of meiosis, this network undergoes a myosin-dependent retraction toward the anterior of the embryo, coalescing in bundles of actin and myosin on the anterior side of the embryo. As it retracts, this cortical network takes with it the anterior PAR proteins such as PAR-6 and PAR-3, allowing PAR-2 to become cortically localized at the other end of the embryo, thereby setting up the initial polarized distribution of the PAR proteins (Figure 1). The myosin-driven cortical movements also result in opposing central movements that carry cytoplasmic determinants toward the site of sperm entry (Cheeks et al., 2004; Munro et al., 2004).

Figure 1. Sperm components drive anterior-posterior Par protein organisation through Rho mediated actin cytokeleton rearrangement.

At the time of fertilization by the sperm (pronucleus-grey, centrosome-yellow), Par3 and Par-6 (green) are uniformly distributed along the anterior-posterior axis of the C. elegans embryo, Par-2 is predominantly cytoplasmic, and there is an ECT-2 and RHO-1 dependent cortical actomyosin network (red). After sperm maturation and duplication, CYK-4 (purple) acts locally at the posterior of the embryo, downregulating Rho signaling, and disrupting the actin network. Actomyosin contraction causes retraction of the actin network, taking with it PAR-3/6, allowing PAR-2 (blue) to become cortically localized.

Three papers now show that these actomyosin contractions are regulated by the small GTPase Rho, which activates myosin, most likely through a Rho-associated kinase (Jenkins et al., 2006; Motegi and Sugimoto, 2006; Schonegg and Hyman, 2006). In embryos lacking RHO-1, myosin activation fails to occur, the actomyosin network fails to form normally, and anterior PAR proteins remain uniformly distributed along the anteroposterior axis of the embryo. Rho family GTPases are commonly regulated by two classes of proteins: RhoGEFs, which activate Rho signaling by triggering GDP/GTP exchange, and RhoGAPs, which inactivate Rho signaling by catalyzing GTP hydrolysis. The C. elegans RhoGEF ECT-2 likely activates RHO-1 during the formation of the actin network at this time, since removal of ECT-2 phenocopies RHO-1 removal, resulting in failure of myosin activation, cortical contraction, and PAR-6 localization.

The Mango lab has studied the C. elegans RhoGAP CYK-4 for its role in epithelial cell polarization in the C. elegans foregut, and they report now that CYK-4 is also associated with membranous organelles of the sperm (Jenkins et al., 2006). Sperm-derived CYK-4 is deposited in the egg at fertilization, and it remains for some time in a bolus at the point of sperm entry. RNAi experiments show that CYK-4 is important for polarizing the one-cell embryo, and by generating embryos in which the CYK-4 is contributed only by the egg or only by the sperm, Jenkins and colleagues can demonstrate that polarization depends critically on the sperm-contributed CYK-4. The results suggest that the sperm-contributed bolus of CYK-4 may act as a localized cue for polarization (Figure 1). CYK-4’s RhoGAP domain may allow it to locally relax the actin cytoskeleton, by acting antagonistically to the Rho signaling that activates actomyosin contractility in the rest of the cell cortex. In support of this, Jenkins et al show that the actomyosin network in cyk-4(RNAi) embryos fails to retract to one side of the embryo even though it coalesces into large bundles, suggesting that the network is contractile but not polarized in the absence of CYK-4.

The new results, together with previous work, suggest a model in which a contractile actomyosin network is stretched around the cortex of the embryo, and sperm donated CYK-4 locally disassembles the network by locally downregulating Rho-mediated myosin activation, leaving a gap in the network near the site of sperm entry. Contraction of the punctured network to the opposite end of the embryo draws with it the anterior PARs, allowing the posterior PARs to bind to the posterior cortex, and also driving central cytoplasmic determinants to the posterior in an opposing flow. CYK-4 is a key player in this model, generating the initial gap that sets the cortex in motion.

What then does the sperm centrosome do? Centrosome-nucleated microtubules have been implicated in locally disassembling an actin network in a number of systems, although exactly how this works has never been completely clear. In C. elegans embryo polarization, the centrosome or associated microtubules might act in parallel with CYK-4 or, they might act as an integral part of a CYK-4 mechanism. For example, CYK-4 is known to be recruited to microtubules during cytokinesis by the kinesin-like protein ZEN-4 (Mishima et al., 2002). While ZEN-4 is not required in polarization, it is possible that alternative or redundant partners may link CYK-4 to microtubules after fertilization. This might enable centrosomes to temporally regulate polarization of the embryo, waiting to drive polarization until meiosis completes by delaying delivery of CYK-4 to the cell cortex until centrosome maturation.

Rho activity and centrosomes have both been recognized as important players in cell polarization in a variety of systems. With two symmetry-breaking cues contributed by the sperm in C. elegans, which one acts as a positional cue, or do both share this job? Does one act as a positional cue and the other as a temporal cue? The new results suggest that changing the position or timing at which both centrosomes and CYK-4 function in C. elegans may provide answers.

References

- Cheeks RJ, Canman JC, Gabriel WN, Meyer N, Strome S, Goldstein B. C. elegans PAR proteins function by mobilizing and stabilizing asymmetrically localized protein complexes. Curr Biol. 2004;14:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CR, Hyman AA. Centrosomes direct cell polarity independently of microtubule assembly in C. elegans embryos. Nature. 2004;431:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N, Saam JR, Mango SE. CYK-4/GAP Provides a Localized Cue to Initiate Anteroposterior Polarity upon Fertilization. Science. 2006 doi: 10.1126/science.1130291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Kaitna S, Glotzer M. Central spindle assembly and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity. Dev Cell. 2002;2:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motegi F, Sugimoto A. Sequential functioning of ECT-2/RhoGEF, RHO-1 and CDC-42 establishes cell polarity in C. elegans embryos. Nature Cell Biology. 2006 doi: 10.1038/ncb1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro E, Nance J, Priess JR. Cortical flows powered by asymmetrical contraction transport PAR proteins to establish and maintain anterior-posterior polarity in the early C. elegans embryo. Dev Cell. 2004;7:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell KF, Maxwell KN, White JG. The spd-2 gene is required for polarization of the anteroposterior axis and formation of the sperm asters in the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote. Dev Biol. 2000;222:55–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SQ, Bowerman B. Cell polarity and the cytoskeleton in the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote. Annu Rev Genet. 2003;37:221–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonegg S, Hyman AA. CDC-42 and RHO-1 coordinate acto-myosin contractility and PAR protein localization during polarity establishment in C. elegans embryos. Development. 2006 doi: 10.1242/dev.02527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville R, Gonczy P. Zyg-11 and cul-2 regulate progression through meiosis II and polarity establishment in C. elegans. Development. 2004;131:3527–3543. doi: 10.1242/dev.01244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenfang MR, Seydoux G. Polarization of the anterior-posterior axis of C. elegans is a microtubule-directed process. Nature. 2000;408:89–92. doi: 10.1038/35040562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]