Abstract

In a Pavlovian conditioning situation, unsignaled outcome presentations interspersed among cue-outcome pairings attenuate conditioned responding to the cue (i.e., the degraded contingency effect). However, if a nontarget cue signals these added outcomes, responding to the target cue is partially restored (i.e., the cover stimulus effect). In 2 conditioned suppression experiments using rats, the effect of posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus was examined. Experiment 1 found that this treatment yielded reduced responding to the target cue. Experiment 2 replicated this finding, while demonstrating that this basic effect was not due to acquired equivalence between the target cue and the cover stimulus. These results are consistent with the extended comparator hypothesis interpretation of the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects.

Keywords: Pavlovian conditioning, degraded contingency, cover stimulus, contingency, comparator hypothesis

The degraded contingency effect, originally reported by Rescorla (1966, 1968), is observed when unsignaled presentations of an unconditioned stimulus (US) are administered during training sessions in which a conditioned stimulus (CS) and a US are paired. These added US presentations diminish responding to the CS, independent of baseline responding in the context. The critical finding of these experiments was that responding to the CS was reduced by a manipulation that did not reduce the contiguity between the CS and the US. Early accounts of classical conditioning assumed that contiguity between stimuli was both necessary and sufficient for classical conditioning to occur (e.g., Bush & Mosteller, 1955). Therefore, the degraded contingency effect seemed inconsistent with pure contiguity accounts of classical conditioning that required only that the CS be consistently closely followed by the US.

Initial explanations of the degraded contingency effect posited that attention to, or learning about, the CS was attenuated by contextual stimuli that became excitatory during the unsignaled presentations of the US, thereby preventing subjects from learning the association between the CS and the US (e.g., Mackintosh, 1975; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). These sorts of accounts are similar to those offered for blocking (Kamin, 1968), but with the training context acting as the blocking cue. For example, the Rescorla-Wagner model of learning explains blocking by assuming there is a finite amount of associative strength supportable by a given US, and the majority of this associative strength is absorbed by the blocking CS during the elemental training phase (A-US), leaving little for the blocked CS at the time of subsequent compound training (XA-US). Applied to the degraded contingency preparation, US-alone presentations make the training context highly excitatory so it comes to block acquisition of the CS-US association. Essentially, this account of the degraded contingency effect assumes that the training context and the target CS compete for the limited amount of associative strength supportable by the US on the CS-US trials. Consistent with this view, Durlach (1983) demonstrated that the degraded contingency effect could be attenuated by preceding the added presentations of the US (i.e., those that were not preceded by the target CS) with another punctate stimulus, which is referred to hereafter as a cover stimulus. Her data were interpreted as resulting from subjects acquiring a stronger target CS-US association because the association between the cover stimulus and the US successfully overshadowed acquisition of the context-US association, thereby preventing the context from competing so successfully with the target CS.

The Rescorla-Wagner model and sometimes opponent process (SOP; Wagner, 1981) both assume that the performance deficit observed after degraded contingency training reflects weakened associative strength acquired between the CS and the US. Furthermore, these accounts assert that the presentation of a cover stimulus prior to intertrial USs prevents the training context from acquiring associative strength with the US, thereby encouraging formation of an association between the target CS and US. We refer to these accounts of the degraded contingency and the cover stimulus effects as acquisition-focused accounts.

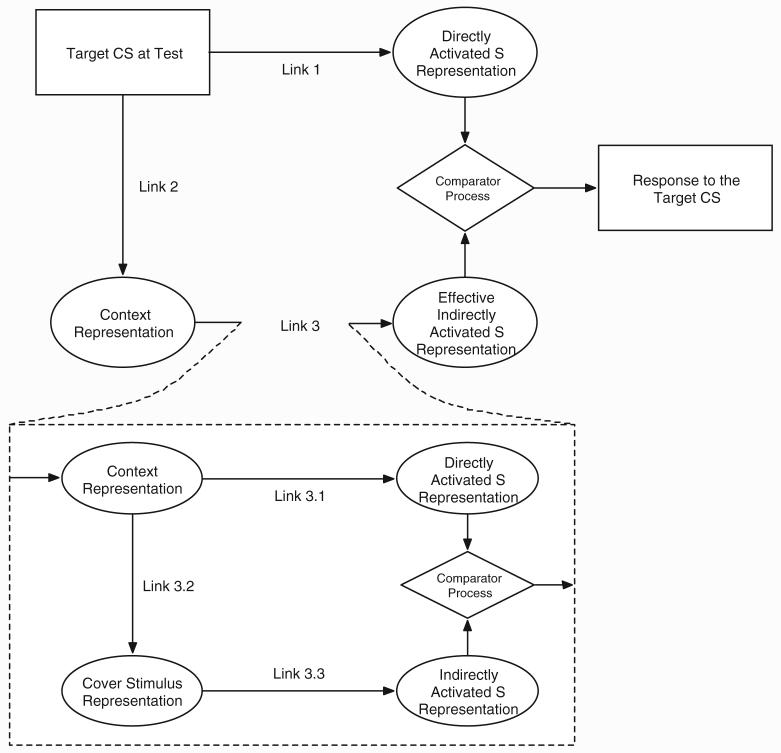

In contrast to acquisition-focused accounts of cue competition, performance-focused accounts of cue competition (e.g., Cooper, 1991; Denniston, Savastano, & Miller, 2001; R. R. Miller & Matzel, 1988; Stout & Miller, 2007) assert that reduced conditioned responding to the CS occurs because of a deficiency in expression of the association between the CS and the US at the time of test. The extended comparator hypothesis (ECH; Denniston et al., 2001) explains the degraded contingency effect by assuming that, at test, the presentation of the CS directly activates two representations (see Figure 1). First, because of the CS’s association with the US (Link 1), the CS directly activates a representation of the US. Second, because of the CS’s association with the training context (Link 2), the CS activates a representation of the training context (the CS’s so-called comparator stimulus), which in turn indirectly activates a second representation of the US (Link 3). However, because degraded contingency treatment involves unsignaled presentations of the US in the training context, the strength of the association between the context and the US (Link 3) is stronger than it would otherwise be, which enhances the strength of the US representation indirectly activated by the CS at test. The US representation directly activated by the CS is compared to the US representation that is indirectly activated by the CS, and this comparison determines the strength of the conditioned response elicited by the target stimulus. According to the ECH, the indirect US representation activated at test by the target cue (X) through X’s association with the training context is compared in a subtractive fashion to the US representation directly activated by X (Stout & Miller, 2007).

Figure 1.

The extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston, Savastano, & Miller, 2001) account of the role of a cover stimulus in a degraded contingency preparation. Ovals depict stimulus representations; solid rectangles depict physical events; diamonds represent the comparator process. In accordance with the comparator hypothesis’s account of the relationship between the cover stimulus and the target stimulus, the only second-order comparator stimulus depicted is that for Link 3. CS = conditioned stimulus; S = surrogate outcome.

Within the framework of the ECH, not only can Link 1 be down-modulated by Links 2 and 3 but Link 3 can also be down-modulated by associations to comparator stimuli (see Figure 1). Applied to the cover stimulus effect, the ECH asserts that the cover stimulus serves as a comparator stimulus for the context-US association (Link 3), which makes it a second-order comparator stimulus for the target stimulus. Moreover, the strength of the indirectly activated US representation is affected not only by the strength of the association between the training context and the US (Link 3.1; see Figure 1) but also by the training context’s association with the cover stimulus (Link 3.2; see Figure 1) and the cover stimulus’s association with the US (Link 3.3; see Figure 1). The association between the training context and the cover stimulus, and the association between the cover stimulus and the US, conjointly activate an indirect US representation at test, which is compared in a subtractive fashion to the US representation directly activated through the training context (Stout & Miller, 2007). The net result of this comparator process determines the indirectly activated US representation that is compared to the US representation directly activated by X at test. Thus, the extended comparator hypothesis anticipates both the degraded contingency effect and the cover stimulus effect.

The present experiments sought to dissociate between acquisition-focused and the ECH accounts of the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects. The ECH predicts that posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus should reduce responding to the target stimulus (X) at test, because this treatment should reduce the strength of Link 3.3. Thus, the indirectly activated outcome representation that is compared to the representation of the outcome directly activated by X should be stronger. In other words, posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus should effectively reinstate the degraded contingency effect. The Rescorla-Wagner model and SOP assert that the presentation of a cover stimulus prior to intertrial outcomes allows the animal to acquire an association between X and the outcome, which is expressed at test as enhanced conditioned responding to X. In contrast to the ECH, these models predict no change in responding to X without actually presenting X. Consequently, according to the aforementioned acquisition-focused models, posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus should not affect responding to X at test. (Other acquisition-focused models are considered in the General Discussion.)

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we sought to replicate the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects as well as determine the effect of posttraining cover stimulus extinction on conditioned responding to the target stimulus. Thus, this experiment involved a posttraining manipulation of a cue that was only indirectly associated with the target stimulus (through cover stimulus-context and context-target stimulus associations) with the expectation, based on the extended comparator hypothesis, that it would result in a decrease in responding to the target stimulus. However, prior findings from our laboratory suggest that, after a cue has come to elicit conditioned responding, the cue is resistant to posttraining manipulations of competing cues that theoretically should yield a decrement in responding to that cue (e.g., R. R. Miller & Matute, 1996; Oberling, Bristol, Matute, & Miller, 2000). This suggests that animals are conservative in decreasing conditioned responding in that they undervalue indirect evidence that suggests conditioned responding is inappropriate. Therefore, the treatments in the current experiments were embedded in a sensory-preconditioning procedure, thereby permitting training and subsequent revaluation of an indirect associate prior to giving the target cue any biological significance. This involved pairing both the target stimulus (X) and the cover stimulus (A) with a surrogate outcome (S) that was paired with the US in a subsequent phase of the experiment (see Table 1). Thus, X and A did not acquire biological significance until S was paired with the US. A one-way, between-subjects design tested the hypothesis that posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus would yield an attenuation of conditioned responding to the target stimulus at test.

Table 1.

Design Summary of Experiment 1

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Test X |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acq | 10 X-S / 20 A | 400 B | 8 S-US | CR |

| Degrade | 10 X-S / 20 A / 20 S | 400 B | 8 S-US | cr |

| Cover | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 B | 8 S-US | CR |

| Cover-Ext | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 A | 8 S-US | cr |

Note. Conditioned stimuli (CSs) A and B were a 10-s white noise and a 10-s tone, counterbalanced within groups. CS X was a 30-s click train exposure. S was a 5-s flashing light exposure that served as an outcome (a surrogate unconditioned stimulus [US]) in Phase 1. The US was a 0.5-s, 0.7-mA footshock exposure. Slashes denote interspersed trials within each session. Based on sometimes competing retrieval simulations of the extended comparator hypothesis, CR denotes a strong expected conditioned response; cr denotes a weak expected conditioned response. Phases 1 and 2 were conducted in Context 1, whereas acclimation, Phase 3, reacclimation, and testing were conducted in Context 2. Acq = Acquisition; Degrade = Degraded Contingency; Cover = Cover Stimulus; Cover-Ext = Cover Stimulus-Extinction.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 24 female (195-253 g) and 24 male (290-353 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naive young adult rats, bred in our colony. Subjects were individually housed and maintained on a 16:8 light-dark cycle with experimental sessions occurring roughly midway through the light portion. All subjects were handled for 30 s three times per week from weaning until the initiation of the study. Subjects had free access to food in the home cage. One week prior to initiation of the experiment, water availability was progressively reduced to 20 min per day, which on treatment days was given 1-4 hr following treatment.

Apparatus

Two distinctly different types of enclosures served as the training and test contexts (Contexts 1 and 2, respectively), the physical identities of which were counterbalanced within groups. Enclosure R was a clear Plexiglas chamber in the shape of a rectangular box 22.75 × 8.25 × 13.0 cm (length × width × height) with a floor constructed of 0.48-cm diameter rods 1.5 cm apart, center to center, connected by NE-2 neons, which allowed a 0.5-s, 0.7-mA constant-current footshock to be delivered by means of a high-voltage AC circuit in series with a 1.0-MΩ resistor. Each of six copies of Enclosure R had its own environmental isolation chest and was dimly illuminated by a 2-W (nominal at 120 volts of alternating current [VAC]) bulb driven at 80 VAC mounted on an inside wall of the environmental isolation chest approximately 30 cm from the center of the animal enclosure. The background noise level (primarily from a ventilation fan) was 74 dB (C scale). A visual stimulus that consisted of a flashing light (0.25 s on/0.25 s off) could be presented. The flashing light was provided by a 25-W bulb (nominal at 120 VAC, but driven at 60 VAC). The light was located approximately 30 cm from the center of the chamber.

Enclosure V was a 25.5-cm-long box in the shape of a truncated V (28 cm high, 21 cm wide at the top, 5.25 cm wide at the bottom). Each of six copies of Enclosure V had its own environmental isolation chest. The floor and long sides were constructed of stainless steel sheets. The ceiling was clear Plexiglas, and the short sides were black Plexiglas. The floor consisted of two parallel metal plates, each 2 cm wide with a 1.25-cm gap between them, which could deliver a 0.7-mA, 0.5-s constant-current footshock. Enclosure V was dimly illuminated by a 7-W (nominal at 120 VAC) bulb driven at 80 VAC mounted on an inside wall of the environmental isolation chest approximately 30 cm from the center of the animal enclosure; the light entering the animal enclosure primarily reflected from the roof of the environmental chest. Due to differences in opaqueness of the enclosures, this level of illumination roughly matched that of Enclosure R. The background noise level (primarily from a ventilation fan) was 74 dB (C scale). A flashing light cue could be provided by a 100-W bulb (nominal at 120 VAC, but driven at 60 VAC). The bulb was mounted on an inside wall of the environmental chest, approximately 30 cm from the center of the experimental chamber. The brightness of the flashing light emitted by this bulb was similar to that of the flashing light in Enclosure R.

Each enclosure (R and V) was equipped with a water-filled lick tube that, when installed, extended 1 cm into a cylindrical niche on a short wall of the enclosure (axis perpendicular to the chamber wall); the niche was 4.5 cm in diameter, left-right centered with its bottom 1.75 cm above the floor of the apparatus, and 5.0 cm deep. There was a horizontal photobeam detector 1 cm in front of the lick tube. Three 45-Ω speakers were mounted on different interior walls of each environmental chest. One speaker was used to present 30-s click trains (6/s) at 6 dB (C scale) above background. Another speaker was used to administer 10-s presentations of an 1800-Hz tone, at 6 dB (C scale) above background. The third speaker was used to administer 10-s presentations of white noise, at 6 dB (C scale) above background. The clicks served as the target CS (X), and the white noise and tone, counterbalanced within groups, served as the cover stimulus (A) and control stimulus (B). The flashing light (5 s) served as the outcome (S; surrogate US) during sensory preconditioning (Phase 1) and was subsequently paired with the footshock US in Phase 3.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups (ns = 12): Acquisition (Acq), Degraded Contingency (Degrade), Cover Stimulus (Cover), and Cover Stimulus-Extinction (Cover-Ext). Subjects were exposed to target training and extinction treatment in one context (Context 1), and acclimation, first-order conditioning, reacclimation, and testing were conducted in a distinctly different context (Context 2). Switching contexts served to minimize possible group differences in fear of the test context due to differences in unsignaled S presentations, which could summate with fear of the CS at test.

Acclimation

Subjects were acclimated to the test context (Context 2) during daily 60-min sessions on Days 1 and 2. During these acclimation sessions, lick tubes were present in the experimental contexts. Acclimation sessions served to establish baseline drinking and reduce unconditioned fear to the test context.

Phase 1

On Days 3 and 4, subjects underwent Phase 1 training in daily 90-min sessions in Context 1. All groups were exposed to X-S presentations at 12.8, 30.3, 47.8, 68.0, and 85.0 min into each training session. X and S were paired serially, whereby the termination of X coincided with the onset of S. Subjects in Group Acq were additionally exposed to 10 A-alone trials per session. These A-alone trials occurred 6.8, 20.4, 24.4, 27.2, 37.0, 55.2, 65.2, 71.0, 74.5, and 82.0 min into each training session. Trials were arranged so that X-S and A-alone trials were pseudorandomly interspersed, with pseudorandomly selected intertrial intervals. Subjects in Group Degrade were exposed to the same X-S and A-alone trials as subjects in Group Acq plus 10 outcome-alone (S-alone) trials per session. The S-alone presentations occurred 3.2, 9.7, 17.4, 34.0, 40.4, 44.2, 52.2, 61.2, 79.4, and 88.8 min into the session. Group Cover was exposed to degraded contingency training similar to the training presented to Group Degrade; however, the S-alone presentations were preceded by presentations of the cover stimulus A, and the A-alone presentations were omitted. On the A-S trials, the onset of S corresponded to the termination of A. Phase 1 training of Group Cover-Ext was identical to the training of Group Cover.

Phase 2

Groups Acq, Degrade, and Cover received identical training in Phase 2, which occurred on Days 5 and 6 in Context 1 during daily 90-min sessions. These subjects were exposed to 200 unpaired presentations per day of a neutral stimulus (B). Subjects in Group Cover-Ext were exposed to 200 unpaired presentations per day of Stimulus A. The mean intertrial interval for Phase 2 sessions was 17 s (± 7s) for all subjects. Importantly, prior unpublished research from our laboratory has demonstrated that 180 min of context exposure does little to decrease the comparator value of a context in preparations like ours; at least 480 min appears necessary to obtain such effects (e.g., Schachtman, Brown, Gordon, Catterson, & Miller, 1987).

Phase 3

On Days 7 and 8, all subjects were exposed to four daily S-US delay-conditioning trials in Context 2, within the course of a daily 60-min session. These pairings caused S to accrue biological significance, making assessment of the X-S association possible. During these trials, the surrogate outcome (5-s flashing light) was paired with a 0.5-s, 0.7-mA footshock such that the footshock was initiated 0.5 s before the termination of the flashing light. All groups were exposed to S-US presentations 11.5, 27.0, 39.0, and 54.0 min into each of the two training sessions.

Reacclimation

On Days 9 and 10, all subjects were exposed to Context 2 for 60 min per day, with lick tubes present in order to restabilize drinking behavior.

Testing

On Day 11, Stimulus X was tested in Context 2 during a 16-min session. When each subject completed 5 cumulative seconds of drinking, CS X was presented. This ensured that all subjects were drinking at the time of CS X onset. Lick-suppression values were calculated based upon the amount of time required to complete an additional 5 cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of X. A 15-min ceiling was placed on suppression scores. As is the practice in our laboratory, all rats that failed to complete 5 cumulative seconds of drinking within the initial 60 s of the test trial were scheduled to be eliminated from the study for exhibiting excessive fear of the test context. In practice, 1 subject from Group Cover-Ext met this criterion. A log (base 10) transformation was performed to improve the within-group normality of the data, thereby allowing for parametric statistical analyses. An alpha value of .05 was adopted for all statistical analyses.

Results and Discussion

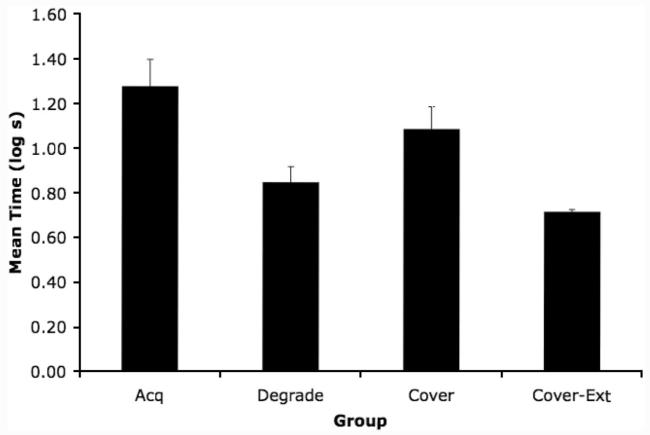

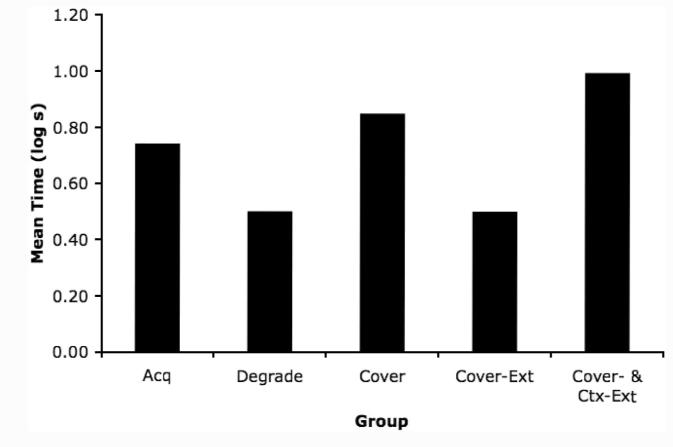

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the log latencies to complete the first 5 cumulative seconds of licking (i.e., prior to CS onset) found no significant effect of group (p = .62), suggesting that there were no appreciable differences between groups with respect to fear of the test context. Group means for suppression in the presence of X are depicted in Figure 2. Conditioned suppression to the test CS (X) was low in all groups relative to what is typically observed in our laboratory given similar treatments. However, a one-way ANOVA on log latencies to complete 5 cumulative seconds of drinking in the presence of the test CS revealed a main effect of group on lick suppression scores, F(3, 43) = 7.67 (see Figure 2). Cohen’s f was calculated to serve as an estimate of effect size (f = .65), which is consistent with a strong effect (see Myers & Well, 2003, p. 210). A planned comparison between Groups Acq and Degrade detected a difference, F(1, 43) = 11.54, which indicates the degraded contingency effect. A planned comparison between groups Degrade and Cover proved significant, F(1, 43) = 4.28, which indicates the cover stimulus effect. Most important, a planned comparison between Groups Cover and Cover-Ext revealed a difference, F(1, 43) = 9.08, indicating that posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus retro-actively decreased conditioned suppression, seemingly revealing a degraded contingency effect.

Figure 2.

Experiment 1: Mean time to complete 5 cumulative seconds of licking in the presence of the target CS (X) in Context 2. See Table 1 for treatments. Error bars denote standard error of means. Acq = Acquisition; Cover-Ext = Cover Stimulus-Extinction.

The data were consistent with prior observations of the degraded contingency effect (e.g., Rescorla, 1968; Urcelay & Miller, 2006) and the cover stimulus effect (e.g., Durlach, 1983; Gunther & Miller, 2000), as well as our expectations for posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus based on the ECH. In contrast, the Rescorla-Wagner model fails to anticipate the observed effect of extinguishing the cover stimulus. According to the ECH, the degraded contingency effect seen in the comparison between Groups Degrade and Acq occurred because the representation of the outcome directly activated by the target stimulus (X) at test was compared to the indirectly activated outcome representation, which was dependent upon the strength of Links 2 (the X-context association) and 3 (the context-S association; see Figure 1). Furthermore, the cover stimulus effect is assumed to have occurred because the cover stimulus acted as a first-order comparator stimulus for the context and hence as a second-order comparator stimulus for X. Presumably, the cover stimulus down-modulated the potential of the training context representation to activate a representation of the outcome (S). That is, Link 3.1 (the context-S association) was down-modulated by the strengths of Links 3.2 (the context-A association) and 3.3 (the A-S association). Alternatively stated, the strength of the representation of S indirectly activated by presentation of CS X seems to have been inversely related to the strengths of the context-A and A-S associations. Thus, overt responding to the target stimulus was augmented by the reduction in the strength of the first-order indirectly activated outcome representation that was compared to the outcome representation directly activated by X at test. Note that Link 2 in Figure 1 is simply the X-context association, because X and A were never paired.

The critical difference that we believe only the ECH can presently explain is the lower suppression of the Cover-Ext group relative to the Cover group. According to the ECH, posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus yielded reduced suppression to CS X because this manipulation attenuated Link 3.3. As a result of reducing the strength of the A-S association (Link 3.3), the indirectly activated representation of S resulting from the X-context and context-S association was stronger. It is important to note that the extinction manipulation occurred after the last CS X training trial.

One could, however, reasonably assert that the difference between Groups Cover and Cover-Ext was due to acquired equivalence. Some research suggests that when two stimuli are paired with a common outcome (e.g., interspersed presentations of X-US and A-US), organisms tend to exhibit enhanced generalization between the two stimuli (Honey & Hall, 1989; N. E. Miller & Dollard, 1941). A prototypical demonstration of acquired equivalence would involve interspersed presentations of X followed by the outcome and A followed by the same outcome. Research suggests that extinguishing A can induce a reduction in responding to X because of enhanced generalization between these two stimuli. Applied to the present situation, this view assumes that the X-S associative strength is reduced during extinction of A. Thus, the present results are explicable in terms of acquired equivalence between the target cue and cover stimulus, even though the physical stimuli corresponding to the target (a 30-s click train presentation) and the cover stimulus (a 10-s white noise or tone presentation) were made dissimilar to reduce the likelihood that this would occur. This account is a viable alternative to that offered by the ECH.

Experiment 2

The purpose of the second experiment was twofold. First, we sought to replicate the central finding of Experiment 1 by demonstrating that posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus yields a reduction in stimulus control by the target stimulus. Second, this experiment sought to dissociate between the acquired equivalence and ECH accounts of the results of Experiment 1. Toward this end, similar to Experiment 1, Experiment 2 involved a between-subjects comparison of degraded contingency treatment (Group Degrade), cover stimulus treatment (Group Cover), and posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus (Group Cover-Ext). In addition, a fourth group was exposed to posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus and subsequent context extinction (Group Cover&Ctx-Ext).

Within the ECH framework, the degraded contingency effect is the result of a comparison between a strong, indirectly activated, contextually mediated outcome representation and a strong, directly activated outcome representation. The ECH posits that posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus results in the recovery of the degraded contingency effect because this treatment reduces the down-modulation of the contextually mediated outcome representation. Therefore, according to this approach, after posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus, one would expect that extinguishing the context would yield an increase in responding to the target stimulus. In contrast, according to the acquired equivalence account of the results of Experiment 1, extinction of the context following extinction of the cover stimulus would not be expected to result in a change in responding to the target stimulus.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 24 female (197-342 g) and 24 male (203-415 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naive, young adult rats, maintained in the same manner as in Experiment 1.

Apparatus

The equipment and parameters used in Experiment 2 were identical to those used in Experiment 1, except for the following changes. Overall, conditioned suppression was low in Experiment 1. One possible reason for this was that S (the flashing light) served as an outcome in Context 1 during Phase 1, and as a cue in Context 2 during Phase 3. Generally, we have found that visual cues do not transfer well between contexts. Hence, the flashing light was replaced with the white noise in serving as outcome S, and a buzzer 8 dB (C scale) above background replaced the white noise in serving as A or B, counterbalanced with the tone within groups. Additionally, to enhance overall suppression, the intensities of the clicks and tone were increased in Experiment 2, from the 6 dB (C scale) above background used in Experiment 1, to 8 dB (C scale) above background. The US intensity was also increased from 0.7 mA to 0.8 mA.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups (ns = 12): Degraded Contingency (Degrade), Cover Stimulus (Cover), Cover Stimulus-Extinction (Cover-Ext), and Cover Stimulus and Context Extinction (Cover&Ctx-Ext). Subjects were acclimated to drink water, given first-order conditioning, reacclimated, and tested in Context 2 in the same way as in Experiment 1. Subjects in Groups Degrade, Cover, and Cover-Ext were treated the same in both experiments during Phases 1 and 2 (see Table 2). Subjects in Group Cover&Ctx-Ext were treated the same as subjects in Group Cover-Ext during the first two phases of the current experiment.

Table 2.

Design Summary of Experiment 2

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Test X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degrade | 10 X-S / 20 A / 20 S | 400 B | 20 min | 8 S-US | cr |

| Cover | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 B | 20 min | 8 S-US | CR |

| Cover-Ext | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 A | 20 min | 8 S-US | cr |

| Cover&Ctx-Ext | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 A | 480 min | 8 S-US | CR |

Note. Conditioned stimuli (CSs) A and B were a 10-s tone and a 10-s buzzer, counterbalanced within groups. CS X was a 30-s click train exposure. S was a 5-s white noise exposure that served as an outcome (a surrogate unconditioned stimulus [US]) in Phase 1. The US was a 0.5-s, 0.8-mA footshock exposure. The number of minutes in Phase 3 indicates the amount of context extinction. Slashes denote interspersed trials within each session. Based on sometimes competing retrieval simulations of the extended comparator hypothesis, CR denotes a strong expected conditioned response; cr denotes a weak expected conditioned response. Phases 1, 2, and 3 were conducted in Context 1, whereas acclimation, Phase 4, reacclimation, and testing were conducted in Context 2. Degrade = Degraded Contingency; Cover = Cover Stimulus; Cover-Ext = Cover Stimulus-Extinction; Ctx-Ext = Context Extinction.

Phase 3

Days 7-10 consisted of context extinction treatment for Group Cover&Ctx-Ext, and a handling control treatment for Groups Cover-Ext, Cover, and Degrade. Group Cover&Ctx-Ext was exposed to 2 hr of exposure to Context 1 during each daily training session, for a total of 480 min of context exposure. This manipulation was intended to extinguish the association between the context and the surrogate outcome (S). The handling and retention interval control treatment for the other three groups consisted of placing subjects in the training context (Context 1) for 5 min per session, for a total of 20 min of context exposure during Phase 3. During these context exposure sessions, no nominal stimuli were presented.

Phase 4

On Days 11 and 12, in Context 2, all subjects were exposed to 4 daily S-US conditioning trials over the course of daily 60-min sessions, just as in Phase 3 of Experiment 1.

A log transformation of the test latency scores was performed as in Experiment 1. No subject met the elimination criterion described in Experiment 1.

Results and Discussion

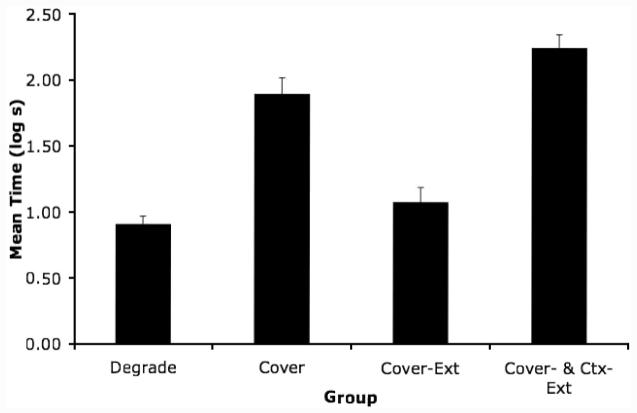

A one-way ANOVA of group on latencies to complete the first 5 cumulative seconds of licking (i.e., prior to onset of X) revealed no significant effect (p = .98), indicating that there were no appreciable differences between groups with respect to fear of the test context. Group means for conditioned suppression during presentation of the test CS are depicted in Figure 3. Clearly, suppression was greater in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1 (note the change in scaling of the ordinate between Figures 2 and 3), consistent with the goal of the procedural changes that were made. A one-way ANOVA of group lick-suppression scores in the presence of X detected an effect of group, F(3, 44) = 44.32. As in Experiment 1, an estimate of effect size was calculated (f = 1.65). Notice that the size of the effect of Group on suppression in the presence of X was far greater in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, which suggests that the between-experiment parameter changes allowed greater sensitivity to an effect of group. A planned comparison between Groups Degrade and Cover revealed a difference, F(1, 44) = 52.84, which indicates the cover stimulus effect. A planned comparison between Groups Cover and Cover-Ext proved significant, F(1, 44) = 36.55, which indicates an effect of extinguishing the cover stimulus. Finally, a planned comparison between Groups Cover-Ext and Cover&Ctx-Ext revealed a difference, F(1, 44) = 73.16, which indicates that extinction of the training context restored responding that had been attenuated by extinguishing the cover stimulus. This result was anticipated by the ECH. The pattern of responding in Groups Degrade, Cover, and Cover-Ext were consistent with the results of Experiment 1. More importantly, the results of Experiment 2 were consistent with the predictions of the ECH, but were inconsistent with an acquired equivalence account of the effect of posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus.

Figure 3.

Experiment 2: Mean time to complete 5 cumulative seconds of licking in the presence of the target CS (X) in Context 2. See Table 2 for treatments. Error bars denote standard error of means. Degrade = Degraded Contingency; Cover = Cover Stimulus; Cover-Ext = Cover Stimulus-Extinction; Ctx-Ext = Context Extinction.

Experiment 3

The results of Experiments 1 and 2 were in accord with the predictions of the ECH. However, an alternative account of the present data might be formulated in terms of latent inhibition. Perhaps the 20 exposures to S alone given to Group Degrade during Phase 1 resulted in the formation of a less effective S-US association during Phase 3 relative to Group Acq of Experiment 1. This is a potential source of the low conditioned suppression observed in Group Degrade. Furthermore, latent inhibition is known to be attenuated if the preexposure treatment involves pairing the target cue (S in this case) with another stimulus, such as A in Group Cover (Lubow, Wagner, & Weiner, 1982). Thus, the latent inhibition account also anticipates the relatively strong suppression displayed by Group Cover. Moreover, research suggests that latent inhibition is not impaired if the signal for preexposure trials (e.g., A in Group Cover) is presented alone prior to compound preexposure (Reed, 1995). Though it has not been explicitly tested, it seems possible that nonreinforced presentations of the signal for preexposure trials could also reduce impairment of latent inhibition if they occur after compound preexposure. This could be viewed as analogous to the treatment that was administered to Group Cover-Ext in Experiments 1 and 2. Thus, a potential interpretation of the data from Experiments 1 and 2 is that the potential of Stimulus S to mediate responding to Stimulus X was impaired in Group Degrade because of S-alone trials, and in Group Cover-Ext because the nonreinforced presentations of A in Phase 2 reduced the recovery from latent inhibition that was caused by the presence of A during preexposure to S during Phase 1. Finally, context extinction can also induce a recovery from latent inhibition, which would be consistent with the elevated responding observed in Experiment 2 in Group Cover&Ctx-Ext (Grahame, Barnet, Gunther, & Miller, 1994). Therefore, a latent inhibition account of the prior experiments seems plausible.

The purpose of Experiment 3 was to determine if the relationships observed in Experiments 1 and 2 could be attributed to group differences in the conditionability of S. Specifically, if latent inhibition decreased the potential of S to mediate responding to X more in Groups Degrade and Cover-Ext than in Groups Acquisition and Cover, then one would expect that the response potential of S would likewise be impaired. Thus, Experiment 3 replicated the treatments presented to Groups Degrade, Cover, and Cover-Ext of Experiments 1 and 2 and Group Acq of Experiment 1. All subjects were tested on S rather than X so that we could assess the effectiveness of Phase 3 S-US pairings.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 24 female (172-224 g) and 24 male (237-324 g) Sprague-Dawley, experimentally naive, young adult rats, maintained in the same manner as in the prior experiments.

Apparatus

The equipment and parameters used in Experiment 3 were identical to those used in Experiment 2.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups (ns = 12): Acquisition Test S (Acq-S), Degraded Contingency Test S (Degrade-S), Cover Stimulus Test S (Cover-S), and Cover Stimulus-Extinction Test S (Cover-Ext-S). Subjects were acclimated to drink water, given first-order conditioning, and reacclimated in exactly the same way as in Experiment 2. Subjects in Groups Degrade-S, Cover-S, and Cover-Ext-S were treated identically during Phases 1, 2, and 3 to Groups Degrade, Cover, and Cover-Ext, respectively, from Experiment 2 (see Table 3). Subjects in Group Acq-S were treated the same as Group Acq in Experiment 1, except that the physical stimuli corresponding to X, S, and A were consistent with the parameters used in Experiment 2 (i.e., Stimulus X was the click train, Stimulus S was the white noise, and Stimuli A and B were the buzzer and tone, counterbalanced within groups). Also, subjects in Group Acq-S were exposed to either A-alone or B-alone trials in Phase 2, thereby creating two subgroups of equal size. The final difference between Experiment 3 and the previous experiments was that subjects were exposed to Stimulus S (white noise) rather than Stimulus X (click train) during testing. A log transformation of the test latency scores was performed as in Experiments 1 and 2. One subject in Group Cover-Ext-S met the elimination criterion described in Experiment 1.

Table 3.

Design Summary of Experiment 3

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Test S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acq-S | 10 X-S / 20 A | 400 A or B | 8 S-US | CR |

| Degrade-S | 10 X-S / 20 A / 20 S | 400 B | 8 S-US | CR |

| Cover-S | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 B | 8 S-US | CR |

| Cover-Ext-S | 10 X-S / 20 A-S | 400 A | 8 S-US | CR |

Note. Conditioned stimuli (CSs) A and B were a 10-s tone and a 10-s buzzer, counterbalanced within groups. CS X was a 30-s click train exposure. S was a 5-s white noise exposure that served as an outcome (a surrogate unconditioned stimulus [US]) in Phase 1. The US was a 0.5-s, 0.8-mA footshock exposure. Slashes denote interspersed trials within each session. Based on our expectation of robust conditioning to S, CR denotes a strong expected conditioned response. Phases 1 and 2 were conducted in Context 1, whereas acclimation, Phase 3, reacclimation, and testing were conducted in Context 2. Acq-S = Acquisition Test S; Degrade-S = Degraded Contingency Test S; Cover-S = Cover Stimulus Test S; Cover-Ext-S = Cover Stimulus-Extinction Test S.

Results and Discussion

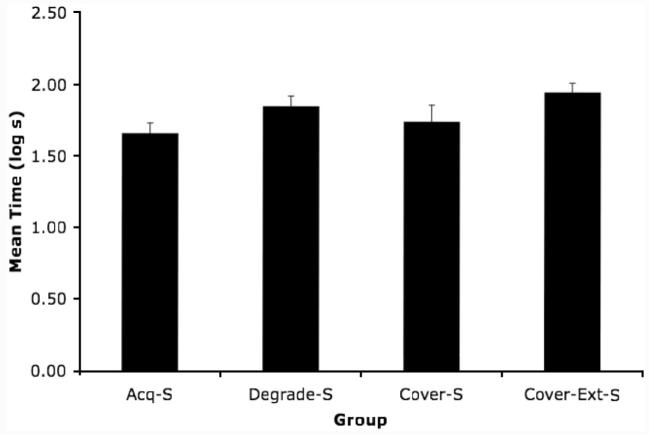

Group means for suppression in the presence of Stimulus S during the test session are depicted in Figure 4. A t-test between the two subgroups comprising Group Acq-S found that Phase 2 extinction of A as opposed to B had no effect on responding to S, t(10) < 0.67. Hence, for all subsequent analyses, these two subgroups were pooled. Clearly, group differences with respect to suppression in the presence of S were small compared to suppression to X seen in Experiments 1 and 2. Moreover, the pattern of responding does not parallel the pattern observed in Experiments 1 and 2. The following analyses were conducted to determine whether experimental treatments affected suppression to S. A one-way ANOVA on the log latencies to complete the first 5 cumulative seconds of drinking during the test session failed to detect an effect of group (p > .25). A similar analysis was used to assess potential differences between groups with respect to suppression in the presence of S. This analysis failed to detect a reliable effect of Group, F(3, 43) = 2.32, p > .08, which suggests that the experimental treatments did not reliably affect the potential of the surrogate outcome to become conditioned during Phase 3. An estimate of the effect size in Experiment 3 was computed (f = 0.28). Note that the effect size in Experiment 3 is considerably smaller than the prior experiments, which suggests that experimental manipulations affected X more than S. Even though this experiment yielded no differences between groups in responding to S, which is commonly viewed as inconclusive, the treatments here were identical to Experiments 1 and 2, which did yield significant differences in responding to X; the nonsignificant pattern of data here was opposite to the pattern of data in Experiments 1 and 2. Because this experiment failed to yield reliable differences between groups with respect to the response potential S, we find it implausible that group differences in the conditionability of S (i.e., latent inhibition) contributed to the pattern of data observed in Experiments 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

Experiment 3: Mean time to complete 5 cumulative seconds of licking in the presence of the surrogate outcome (S) in Context 2. See Table 3 for treatments. Error bars denote standard errors of mean. Acq-S = Acquisition Test S; Degrade-S = Degraded Contingency Test S; Cover-S = Cover Stimulus Test S; and Cover-Ext-S = Cover Stimulus-Extinction Test S.

General Discussion

The current experiments elucidated several important aspects of the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects. First, the observed recovery of the degraded contingency effect due to extinction of the cover stimulus and the observed restoration of suppression to the target cue as a result of also extinguishing the context are both inconsistent with traditional acquisition-focused accounts of the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects. Moreover, these treatments did not seem to impact the condition-ability of S. According to the Rescorla-Wagner (1972) model, posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus should not have affected responding to the target stimulus because this and similar models do not predict that changes in associative strength between a CS and an outcome can occur unless the CS is present.

The results of Experiment 1 are not even anticipated by acquisition-focused accounts of retrospective revaluation, such as those of Dickinson and Burke (1996) or Van Hamme and Wasserman (1994). Such models anticipate that posttraining manipulations of a nontarget stimulus that has been directly paired with the target stimulus will have an opposing effect on the target stimulus. One necessary condition for those changes is that the nontarget stimulus must have a within-compound association with the target stimulus. Notably, these models cannot account for the observed effects of posttraining manipulations of stimuli that are only indirectly associated with the target stimulus (e.g., De Houwer & Beckers, 2002; Denniston, Savastano, Blaisdell, & Miller, 2003; Urushihara, Wheeler, Pineno, & Miller, 2005). Specifically, the revised Rescorla-Wagner and revised SOP models proposed by Van Hamme and Wasserman (1994; also see Wasserman & Castro, 2005) and Dickinson and Burke (1996; also see Aitken & Dickinson, 2005), respectively, both assume that the associative strength between the CS and the outcome can change on trials on which the target CS is absent but is expected based upon the presence on that trial of other cues previously associated with the target. Through this mechanism, they account for the effects of posttraining extinction manipulations of associates of the target cue in situations such as blocking (Arcediano, Escobar, & Matute, 2001; Blaisdell, Gunther, & Miller, 1999) and overshadowing (Matzel, Schachtman, & Miller, 1985) which have been found to result in recovery from cue competition phenomena. Importantly, despite successfully predicting the effect of posttraining extinction of the treatment context following degraded contingency treatment, the effect of posttraining extinction of the cover stimulus is unanticipated by both the revised Rescorla-Wagner and SOP models. According to these models, the associative strength between the target cue and the outcome should not change during the posttraining manipulations of the cover stimulus because there is no within-compound association between the two cues (note that during training X and A were never presented in compound).

In contrast to acquisition-focused models of retrospective revaluation, the data were consistent with the ECH interpretation of the degraded contingency and cover stimulus effects. This prediction is illustrated in Figure 5, which depicts simulations of the response potential of the target CS after simple acquisition, degraded contingency treatment, cover stimulus treatment, posttraining cover stimulus extinction, and context extinction subsequent to cover stimulus extinction. For this simulation, we used Stout and Miller’s (2007) mathematical implementation of the extended comparator hypothesis, including their parameters and the number of trials used in the present series of experiments. Stout and Miller’s model uses contiguity-based simple associative learning equations (e.g., Bush & Mosteller, 1955) to establish the links within the ECH framework, and a subtractive comparator function to compute values for the response potential of a stimulus. The model clearly anticipated the pattern of results observed in the present experiments.

Figure 5.

Simulation of the groups from Experiments 1 and 2 after Stout and Miller’s (2007) implementation of the extended comparator hypothesis. All parameters were the same as those used by Stout and Miller, and the numbers of trials were the same as those used in Experiments 1 and 2 of the present experiments. Acq = Acquisition; Degrade = Degraded Contingency; Cover = Cover Stimulus; Cover-Ext = Cover Stimulus-Extinction; Ctx-Ext = Context Extinction.

In summary, Experiment 1 is explicable in terms of stimulus equivalence and the performance-focused ECH but not contemporary acquisition-focused models of learning including those explicitly designed to account for retrospective revaluation. In Experiment 2, the increased responding to X as a result of posttraining context extinction is explicable in terms of either acquisition-focused models of learning that were designed to address retrospective revaluation or the ECH, but not stimulus equivalence. This leaves the ECH as the only current model that appears able to anticipate the results of both experiments. However, it should be noted that the present experiments were embedded in a sensory preconditioning preparation. Although we have good reason to doubt that extinguishing the cover stimulus would restore the basic degraded contingency effect in first-order conditioning (e.g., R. R. Miller & Matute, 1996), many learning situations, particularly with human participants, depend on sensory preconditioning and second-order conditioning. Thus, the fact that the experiments were conducted in a sensory preconditioning preparation does not necessarily devalue the importance of the present findings.

The degraded contingency effect originally was viewed as inconsistent with contiguity accounts of associative learning. The contiguity between a CS and a US (as normally defined) is not affected during degraded contingency treatment; yet, there is a pronounced reduction in responding to the CS after such treatment relative to otherwise equivalent subjects lacking the unsignaled outcome presentations. Consequently, it was thought that factors other than contiguity were critical to learning. Different models accounted for the degraded effect by asserting that limited attentional or associative resources were distributed between the context and the CS, thereby producing impaired acquisition of the CS-outcome association. These models assert that simple contiguity is not sufficient for conditioning to occur. In contrast, the ECH asserts that simple contiguity is both necessary and sufficient for conditioning, and the current series of experiments lend support to this view. Of course, there are other observations that are problematic for the ECH (e.g., Melchers, Lachnit, & Shanks, 2004), but there is surely no contemporary model of learning that is free of problematic data. The effect of extinguishing the cover stimulus suggests that animals do acquire a context-outcome association during cover stimulus treatment, but this association is not retrieved when testing of X occurs without prior extinction of the cover stimulus. The majority of modern learning theories (e.g., Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Wagner, 1981) assume that contiguity is necessary but not sufficient for the acquisition of associations between event representations. However, the present experiments, in conjunction with a growing body of data (e.g., Blaisdell et al., 1999; Matzel et al., 1985), suggest that effects that were once assumed to reflect impaired acquisition may be the result of response deficits.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. 33881. We thank Danielle Beaumont, Jonah Grossman, David Guez, Bridget L. McConnell, Alyssa Orinstein, Wan See, Heather T. Sissons, Gonzalo P. Urcelay, Kouji Urushihara, and Daniel S. Wheeler for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

References

- Aitken MRF, Dickinson A. Simulations of a modified SOP model applied to retrospective revaluation of human causal learning. Learning & Behavior. 2005;33:147–159. doi: 10.3758/bf03196059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcediano R, Escobar M, Matute H. Reversal from blocking humans as a result of posttraining extinction of the blocking stimulus. Animal Learning & Behavior. 2001;29:354–366. [Google Scholar]

- Blaisdell AP, Gunther LM, Miller RR. Recovery from blocking through deflation of the blocking stimulus. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1999;27:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bush RR, Mosteller F. Stochastic models for learning. Wiley; New York: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LD. Temporal factors in classical conditioning. Learning and Motivation. 1991;22:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J, Beckers T. Higher-order retrospective revaluation in human causal learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2002;55B:137–151. doi: 10.1080/02724990143000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Savastano HI, Blaisdell AP, Miller RR. Cue competition as a retrieval deficit. Learning and Motivation. 2003;34:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Savastano HI, Miller RR. The extended comparator hypothesis: Learning by contiguity, responding by relative strength. In: Mowrer RR, Klein SB, editors. Handbook of contemporary learning theories. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2001. pp. 65–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, Burke J. Within-compound associations mediate the retrospective revaluation of causality judgements. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49B:60–80. doi: 10.1080/713932614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlach PJ. Effect of signaling intertrial unconditioned stimuli in autoshaping. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1983;9:374–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahame NJ, Barnet RC, Gunther LM, Miller RR. Latent inhibition as a performance deficit resulting from CS-context associations. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1994;22:395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gunther LM, Miller RR. Prevention of the degraded-contingency effect by signalling training trials. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2000;53B:97–119. doi: 10.1080/713932719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey RC, Hall G. The acquired equivalence and distinctiveness of cues. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1989;15:338–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin LJ. “Attention-like” processes in classical conditioning. In: Jones MR, editor. Symposium on the prediction of behavior: Aversive stimulation. University of Miami Press; Miami, FL: 1968. pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE, Wagner M, Weiner I. The effects of compound stimuli preexposure of two elements differing in salience on the acquisition of conditioned suppression. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1982;10:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh NJ. A theory of attention: Variations in the associability of stimuli with reinforcements. Psychological Review. 1975;82:276–298. [Google Scholar]

- Matzel LD, Schachtman TR, Miller RR. Recovery of an overshadowed association achieved by extinction of the overshadowed stimulus. Learning and Motivation. 1985;19:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Melchers KG, Lachnit H, Shanks DR. Within-compound associations in retrospective revaluation and in direct learning: A challenge for comparator theory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2004;57B:25–53. doi: 10.1080/02724990344000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NE, Dollard J. Social learning and imitation. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RR, Matute H. Biological significance in forward and backward blocking: Resolution of a discrepancy between animal conditioning and human causal judgment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1996;125:370–386. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RR, Matzel LD. The comparator hypothesis: A response rule for the expression of associations. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. 22. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1988. pp. 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JL, Well AD. Research design and statistical analysis. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oberling P, Bristol AS, Matute H, Miller RR. Biological significance attenuates overshadowing, relative validity, and degraded contingency effects. Animal Learning & Behavior. 2000;28:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Reed P. Enhanced latent inhibition following compound preexposure. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1995;48B:32–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Predictability and number pairings in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Psychonomic Science. 1966;4:383–384. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Probability of shock in the presence and absence of CS in fear conditioning. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1968;66:1–5. doi: 10.1037/h0025984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: Black AH, Prokasy WF, editors. Classical conditioning: II. Current theory and research. Appleton-Century Crofts; New York: 1972. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Schachtman TR, Brown AM, Gordon EL, Catterson DA, Miller RR. Mechanisms underlying retarded emergence of conditioned responding following inhibitory training: Evidence for the comparator hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1987;13:310–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout SC, Miller RR. Sometimes competing retrieval (SOCR): A formalization of the comparator hypothesis. Psychological Review. 2007;114:759–783. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urcelay GP, Miller RR. Counteraction between overshadowing and degraded contingency treatments: Support for the extended comparator hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:21–32. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushihara K, Wheeler DS, Pineno O, Miller RR. An extended comparator hypothesis account of superconditioning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2005;31:184–198. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.31.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hamme LJ, Wasserman EA. Cue competition in causality judgements: The role of nonpresentation of compound stimulus elements. Learning and Motivation. 1994;25:127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AR. SOP: A model of automatic memory processing in animal behavior. In: Spear NE, Miller RR, editors. Information processing in animals: Memory mechanisms. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman EA, Castro L. Surprise and change: Variations in the strength of present and absent cues in causal learning. Learning & Behavior. 2005;33:131–146. doi: 10.3758/bf03196058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]