Abstract

Pancreatic carcinoma accounts for the most dismal survival among all malignancies with 5-year survival rates approaching 5%. The reason for this, besides the inherent biologic nature of the disease, is the fact that the patients tend to present late in the disease. We present a review of the current published data on cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, which though rare, constitute an important subgroup of pancreatic neoplasms that have a better prognosis and are potentially curable lesions.

Keywords: cystic tumours, pancreas, serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas (IPMN)

Introduction

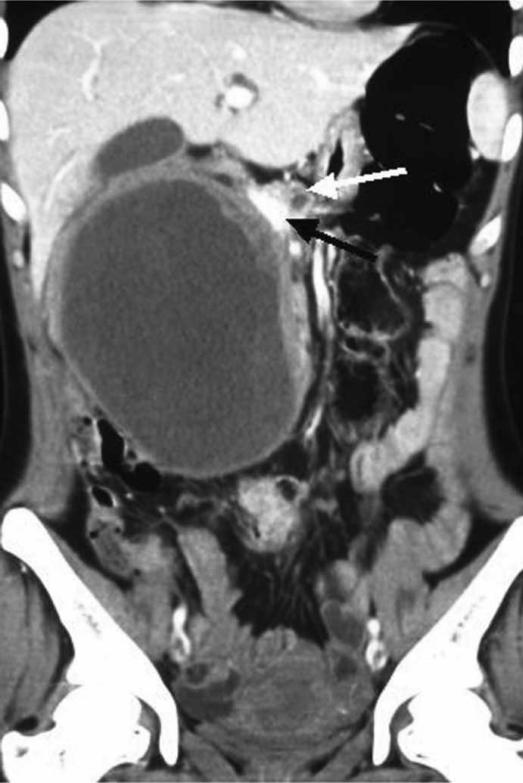

Cystic pancreatic neoplasms are tumours that have frequently been misdiagnosed or under-diagnosed. A commonly encountered folly has been the misdiagnosis of these tumours as pseudocysts and their consequent mismanagement. This has been due to the relative lack of awareness and also the lack of knowledge of the diagnostic and therapeutic modalities available. In the modern era of highly sensitive radiologic investigations, primary cystic neoplasms are increasingly being detected incidentally. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), helical computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and tumour markers (CEA, CA 19-9 and CA125), have enabled differentiation not only between the various types but also the subtypes of cystic pancreatic tumours. This attains significance from the perspective of radicality of surgery for mucinous and serous cystic neoplasms. The prognosis of primary cystic pancreatic neoplasms depends on the histologic type, as well as invasiveness of the tumour. The therapeutic principles are now well defined in this subset of pancreatic tumours.

Figure 1. .

Coronal reformation of contrast-enhanced abdominal MDCT showing a large cystic mass with well defined smooth walls. Also seen is an irregular solid component along the left lateral and superior walls. The mass is in close contact with the pancreatic head (white arrow) and the portal vein is seen medial to it (black arrow).

This review aims to provide an insight into the various types of primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms, their behaviour, treatment and prognosis, taking into account the fact that while they may be referred to under one big heading, each entity is actually unique in its pathology, presentation and management.

Incidence

Cystic tumours constitute 10% of cystic lesions of the pancreas, showing all stages of cellular differentiation from benign to highly malignant tumours 1. Benign (serous and mucinous) cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas constitute three-quarters of these cystic tumours 2. These cystic neoplasms account for 1–10% of all pancreatic malignancies 1,3,4. The incidence of radiologically detected pancreatic cystic neoplasms in screening varied from 0.2% 5 when ultrasonography was used to 0.7% 6 in a study using CT and MRI scans.

Serous cystic neoplasms predominantly affect women (65%), with an average age of 62 years (range 35–84 years) 7. They account for 32–39% of cystic tumours of the pancreas 8. Mucinous cystic neoplasms also affect predominantly women (>95%), with an average age of 53 years (range 19–82 years) 9,10. They constitute 10–45% of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Together with the above two, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMNs) accounting for 21–33%, comprise the three most commonly encountered tumours 8. IPMNs occur a little more commonly in males at an average age of 65 years. Solid papillary epithelial neoplasias (SPENs) are tumours that predominantly occur in females in the third to fourth decade of life 8,11. Non-functioning islet cell tumours (NFITs) with cystic degeneration occur at an average age of 53 years 12. Acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma most commonly occurs in males and constitutes < 1% of cystic tumours 8.

Pathological classification

The four main classes of cystic pancreatic tumours 10 include serous cystic, mucinous cystic, intraductal papillary mucinous, and the other unusual neoplasms, including SPENs. The WHO classification is listed in Table I13.

Table I. WHO classification of cystic pancreatic tumours 13.

| Serous microcystic adenoma |

| Serous oligocystic adenoma |

| Serous cystadenocarcinomas |

| Mucinous cystadenoma |

| Mucinous cystic neoplasm – borderline |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas |

| – Non-invasive |

| – Invasive |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm – borderline |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma |

| – Non-invasive |

| – Invasive |

Clinical presentation

Up to 40–75% of patients with cystic pancreatic tumours are asymptomatic 14, with the majority being detected incidentally on imaging modalities. Symptoms, when present, are a result of pressure effects and are more common in mucinous lesions – the incidence of symptoms correlating with the risk of malignancy 15. The most commonly encountered symptoms are abdominal pain, weight loss and nausea 16. The less common symptoms are constipation, diarrhoea, abdominal distension, fatigue, early satiety and, in the rare event of functioning tumours, the patient may show signs of hypoglycaemia 17. Jaundice, as a symptom, is uncommon in serous neoplasms even if the lesion is of a large size. In contrast, it is seen in 25–54% patients with mucinous tumours in the head of the gland 10,18. As such, a patient presenting with a large lesion in the head and neck of the pancreas without jaundice, should arouse the suspicion of a cystic neoplasm. A prior history of pancreatitis is largely confirmatory of pseudocysts, although the occasional cystic neoplasm may give rise to an attack of pancreatitis following partial duct obstruction 10. Bleeding-related complications secondary to gastric involvement, portal hypertension, haemobilia or haemosuccus pancreaticus, can be seen in malignant mucinous neoplasms 19,20. In rare cases of SPEN, patients have presented with acute abdominal pain due to rupture of the tumour 21. IPMNs, when symptomatic, present with signs of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, i.e. pain, steatorrhoea, weight loss, diabetes, etc. They can also present as acute or recurrent pancreatitis. The main distinguishing feature is the lack of aetiology for acute pancreatitis on obtaining a history in such a patient. Diabetes is found to be associated with mucinous tumours, especially those that are malignant 22. Rare associations with Peutz-Jeghers and Zollinger Ellison syndrome have been described 23,24. On examination, a palpable mass may be detectable in cases of malignant mucinous cystic lesions 18.

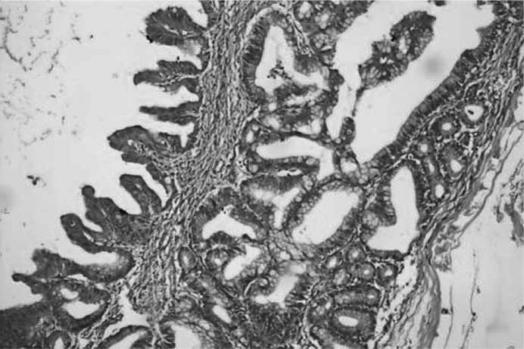

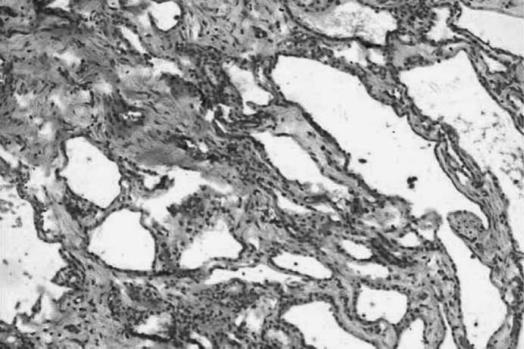

Pathology (Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2. .

Photomicrograph showing cystic mucinous neoplasm of pancreas with mild dysplasia (H&E stain, ×20).

Figure 3. .

Photomicrograph showing serous microcystic adenoma of pancreas (H&E stain,×20).

Serous cystadenomas (SCAs) vary in size from 6 to 10 cm, although cysts of even 25 cm have been reported. They are well demarcated and are lined by simple, glycogen-rich cuboidal epithelium and characterized by a dense, lace-like, honeycombed matrix of fibrous septae. They have been referred to as microcystic as they are made up of clusters of cysts that are filled with clear watery, non-mucinous and occasionally bloody fluid.

Mucinous neoplasms are made up of cysts that are larger in size than the serous neoplasias and are usually up to 25 cm. The cyst contains clear, mucinous, viscid fluid. The main features that help in distinguishing it from other cystic neoplasias are the presence of a dense mesenchymal ovarian-like stroma and the lack of communication with the main pancreatic ductal system 25,26. Furukawa et al. 27 had earlier divided mucus-hypersecreting tumours into four types based on their gross features, i.e. (1) uniformly dilated main duct; (2) focally dilated main duct; (3) cystic sub-branches; and (4) dilated sub-branches. The Mayo Clinic has recently divided these tumours, for purposes of treatment, into three subgroups 28: (a) mucinous cystadenomas (MCAs) (65%); (b) non-invasive proliferative MCNs (30%), with and without dysplasia; and (c) mucinous cystadenocarcinomas.

IPMNs are characterized by papillae (intestinal, hepatobiliary, gastric, or rarely, oncocytic) 29,30,31,32 arising from the intraductal proliferation of neoplastic mucinous cells. It is associated with the dilatation of the pancreatic duct and/or the ductal side branches that contain mucin. They have been seen to possess four predominant patterns 14: (1) diffuse main pancreatic duct ectasia; (2) segmental main pancreatic duct ectasia; (3) side-branch duct ectasia (‘branch-duct’ type); (4) unifocal and multifocal cysts with pancreatic duct communication.

Solid and cystic papillary and epithelial neoplasias (SPENs) have a variegated appearance with solid, cystic and papillary areas with foci of necrosis and haemorrhages. The degenerative areas have been attributed to vascular ischaemia 33. The most useful markers are alpha-1-antitrypsin, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, neuron specific enolase (NSE) and vimentin 34.

Lew et al. 35 in their recent publication have raised the issue of mucinous ductal ectasia (MDE) as a less known entity often confused with mucinous cystic neoplasms. According to them, MDEs are characterized by dilated primary and secondary ducts filled with thick mucus that appear as a mass or cyst on imaging 35. The existence of MDE as an entirely separate entity has been strongly contested by Rivera et al. 36, who had suggested that this may actually be a subgroup of intraductal papillary neoplasms (IPNs). They felt that the introduction of the term IPMN should broadly encompass the entire spectrum of these neoplasms.

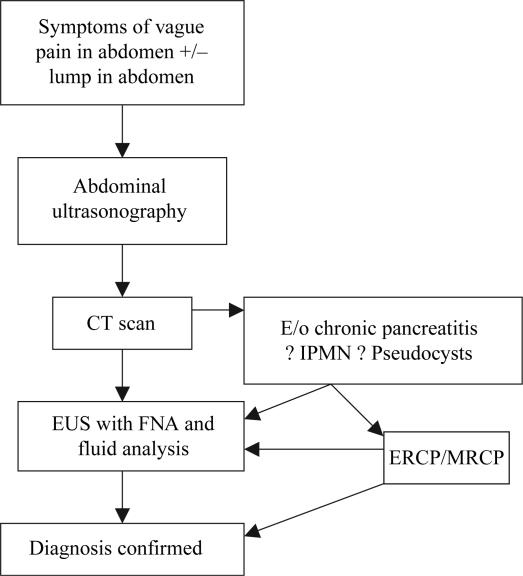

Diagnosis (Algorithm 14)

Algorithm 1. Diagnostic algorithm for cystic pancreatic tumours.

Ultrasonography is a useful basic investigation as it can help differentiate a solid from a cystic lesion but it does not permit a complete characterization due to the presence of bowel gas that often obscures vision.

CT scan is the most favoured initial diagnostic test for cystic tumours of the pancreas. It is not only useful in the diagnosis but also helps in characterization of the lesion based on calcification of the cyst wall, septa, mural nodules and the findings suggestive of pancreatitis 37,38,39. Enhanced CT with bolus injection of contrast medium and thin collimation is useful in differentiating SCA from mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs).

Appearances

SCA – water, soft tissue or mixed density; poorly defined to thin, well defined capsule; multiple, small (<2 cm) well-defined cysts, central calcifications, and enhancement around microcysts after contrast administration.

MCA – near water density unilocular or multilocular large cysts with enhancing walls and septa, and peripheral calcifications.

Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas (MCACs) – thick-walled (>2 mm) macrocysts, with septations, a solid component and a peripheral rim of calcifications.

IPMN – segmental or diffuse dilatation of the pancreatic ductal system. In side-branch IPMT, involvement is limited to segmental ducts, resulting in a solitary cystic mass with an otherwise normal ductal system 40.

NFIT and SPEN – hypervascular peripheral solid components and central cystic.

Atypical SCAs may appear as solid masses due to innumerable tiny cysts below the resolution of imaging equipment, or they may contain larger cysts similar to those of MCN. In this respect, some malignant cystic lesions mimic the appearance of a pseudocyst or other benign lesions.

MRCP

MRI provides a better characterization of the morphology of the cyst. In the case of IPMN it is being strongly advocated as the diagnostic modality of choice. Its advantage over ERCP stems from its ability to image the pancreatic duct anatomy/configuration and size 41, as filling of the side branch ducts may be obscured by intraductal mucin plugs in ERCP 42.

Taouli et al. 43 have shown that certain features of IPMN detected on MRI may actually indicate a higher probability of a malignancy, i.e. presence of a solid mass, main pancreatic duct dilatation (>10 mm), diffuse or multifocal involvement, and attenuating or calcified intraluminal content.

ERCP

ERCP plays a role in identifying the ductal anatomy and delineating the presence of any communication between the cyst and the duct that may be present in up to 65% cases 33. It is useful in differentiating an MCN for chronic pancreatitis from IPMN. The main indication was the diagnosis of IPMN based on the demonstration of the communication of the tumour with the main duct and the side branches, as well as discharge of mucin from the ampulla – an indication that is being strongly challenged by advocates of MRCP. It is still an important investigation in the exceptional case of a patient with a cystic mass in the head of the pancreas very close to the main duct of Wirsung and where a differentiation between IPMN and even a serous cyst adenocarcinoma appears difficult and necessitates the demonstration of the relationship between the mass and the duct 44.

Angiography

The vascularity of the tumour and the peripancreatic region can be studied with the help of angiography that can help to differentiate a hypervascular tumour from hypovascular pseudocysts 45. It has been seen though that cystic tumours may also be hypovascular simulating pseudocysts. With the availability of better non-invasive diagnostic tests, the need for angiography has reduced. Its influence on guiding treatment has been down-played by the fact that surgeons today have a better understanding of the anatomy and as such do not need an additional test to define the vascular status preoperatively.

EUS

The main role for EUS in cystic pancreatic neoplasias is to provide a detailed morphology of the cystic lesion (including the presence of intramural nodules in IPMN) and to guide fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the lesion 46,47. It has its limitations in differentiating mucinous from non-mucinous cystic lesions 48 due to its low sensitivity and specificity, i.e. 38.9% and 75.0%, respectively 16. This also causes difficulty in differentiating benign from malignant lesions 49.

Cyst fluid analysis

Today, the analysis of the cyst fluid obtained from an EUS-guided aspiration provides valuable information if analysed for biochemistry, tumour markers and not only cells as these aspirates tend to be paucicellular. In general, glycogen-rich cells are specific for serous cystadenoma, mucin-containing cells are seen in mucinous cystadenomas, and malignant cells are seen in mucinous cystadenocarcinomas 12. Potential complications of FNA include spillage of malignant cells into the peritoneum, haemorrhage and injury to adjacent organs.Table II shows the various components that are analysed and the quantities in which they are found in the various common neoplasias 8,10,50,51,52.

Table II. Cyst fluid analysis 8,10,42,43,44.

| Component | Serous cystadenoma | Mucinous cystadenoma | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia | Pseudocyst |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase (<250 U/l) | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| CEA (ng/ml) | <5 | >800 | >800 | 5–800 | <5 |

| CA 19-9 (U/ml) | <37 | Variable | Variable | Variable | <37 |

| CA 15-3 | Low | High | High | Low | Low |

| TAG 72 (U/ml) | <3 | 3–137 | >780 | High | <5.7 |

| Malignant cells | Absent | Absent | Present | Absent | Absent |

| CA 125 | Low | Variable | Variable | Low | Low |

| Viscosity | Low | High | High | High | low |

PET scan

Sperti et al. 53 have suggested that 18-FDG PET may be better than CT and tumour marker assays in the preoperative evaluation of patients with cystic pancreatic lesions, as a positive result strongly suggests malignancy, and hence surgery, while a negative result implies a benign lesion that may be treated by limited resection or, in selected high- risk patients, with biopsy, follow-up, or both.

Management

The treatment of cystic pancreatic tumours depends on the probable diagnosis, as the likelihood of malignancy is closely related to the type of histology. The possibility of malignancy in a serous cystic tumour is as low as 3% 54, while main duct IPMNs have a 70% chance of being malignant 55. Mucinous cystic tumours can be best considered as premalignant.

With the increased diagnosis of incidental tumours because of high quality imaging, we are now also faced with the decision of whether to operate these patients with lesions < 3 cm. While Sahani et al. 56 have found that lesions < 3 cm are usually benign, Kiely et al. 57 have stressed the need for enucleation even in patients with lesions < 2 cm, as long as the patient can withstand the surgery. This recommendation is based on a high incidence of false negatives seen in investigations. Allen et al. 58 in a recent large series of 539 cases spanning 10 years have concluded that selected patients with cystic lesions <3 cm in diameter and without a solid component may be followed radiographically with a malignancy risk that approximates the risk of mortality from resection. This is based on the premise that small mucinous lesions are unlikely to be malignant.

The currently accepted guidelines are that for SCAs, an organ-preserving resection should be carried out, although there are proponents of a conservative line of management 59,60. A fair consensus is that lesions that are asymptomatic and/or <4 cm in size can be followed up at yearly intervals, while surgery should be offered to patients with symptomatic lesions and tumours >4 cm, because they have been seen to grow at a rate of almost 1.98 cm/year 61.

In the case of mucinous tumours, a more radical resection is advised 59. This is based on the understanding of its malignant potential. As these tumours usually occur in the fifth decade, the likelihood of a malignant transformation is also high. In the presence of predictors of malignancy, such as large tumour size, mural nodules and egg-shell calcification, spleen-preserving techniques should be avoided to obtain a correct oncological lymph node dissection 55,62.

In the case of IPMN, where the tendency is for the tumour to grow along the ducts rather than radially into the parenchyma, the resection margins must be examined by frozen section intraoperatively to confirm the clearance of the margins. The current recommendation is to resect all main duct and mixed variant IPMNs as long as the patient is a good surgical candidate with a reasonable life expectancy 55. Routine total pancreatectomy is not indicated and should be performed only for obvious extensive, but resectable, histologically confirmed disease involving the entire gland 63.

The issue of management of pure branch-type IPMNs remains to be resolved, with conflicting data on whether a conservative approach 64 or an anatomic resection should be performed 63. The IAP consensus for management of IPMNs 55 has attempted to put some of these doubts to rest by recommending surgery for symptomatic lesions. However, they have added that other indications could include patients willing for surgery and unlikelihood of follow-up. This remains an option only if a safe pancreatic resection is available. The ideal management of branch-duct IPMNs > 30 mm and without main duct dilation or mural bodies awaits further evidence.

Intraoperative ultrasonography can assist in differentiating a pseudocyst from a cystic neoplasm 12, although a preoperative history of severe acute pancreatitis coupled with the imaging showing intracystic septae and nodules should make the differentiation easier. Caution is required because inflammatory precipitations may mimic the neoplastic features. In contrast, some cystadenocarcinomas lack the characteristics of malignancy and even gross inspection may lead to a misdiagnosis 65,66.

For lesions located at the pancreatic body and tail (Figure 4), a segmental or distal pancreatectomy, with preservation of the spleen where possible, is recommended 67,68,69,70,71. In case of cystic masses that are malignant or potentially malignant in the head of the pancreas, a pancreaticoduodenectomy is the preferred option, but an enucleation can be performed if there is an accurate diagnosis of a benign lesion.

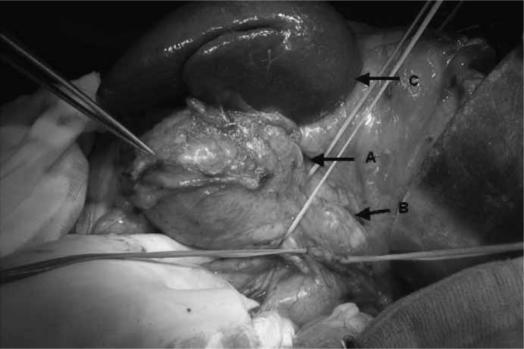

Figure 4. .

Intraoperative picture of cystic tumour in the body and tail of the pancreas. Arrows indicate: A, cystic tumour; B, normal body of the pancreas; C, spleen.

Indications for a ‘wait and see’ policy in MCNs and IPMNs include 55: (1) symptomatic cysts without main duct dilatation (>6 mm), (2) those without mural bodies, and (3) those < 30 mm in size. The ideal investigations for monitoring such patients would be CT or MRCP and EUS.

The suggested interval between follow-up examinations would appear to be yearly for lesions < 10 mm in size, 6–12 monthly follow-up for lesions between 10 and 20 mm, and 3–6 monthly follow-up for lesions > 20 mm. The interval can be lengthened after 2 years of stationary findings. Indications for giving up the conservative management would include the appearance of symptoms, and findings contrary to those listed above.

The overall 5-year survival nears 100% for SCA and even MCA where the resection margins are clear and there is no evidence of transmural invasion 8,14. Even in IPMNs containing carcinoma, 5-year survival is over 50% 72.

Walsh et al. 73 have even suggested that with the increasing incidence of ‘incidentally’ detected asymptomatic pancreatic cysts, if a mucinous neoplasm can be excluded with confidence, an EUS-guided aspiration can be done and the patient can be followed up clinically and with interval imaging. One of the reasons for EUS aspiration is that it permits the detection of mucin extrusion seen in a case of a mucinous neoplasm.

A few reports exist on the use of chemotherapy, and occasionally, radiotherapy in the adjuvant setting. The indications enlisted have been evidence of tissue invasiveness 74,75 in the pathological specimen, liver metastasis (chemoembolization) 76, unresectable tumour (radiotherapy) 77, large tumours (neoadjuvant chemotherapy to downsize the tumour for surgery) 78, and with aneuploid neoplasms 79. Sarr et al. have suggested a role for adjuvant treatment even in the absence of lymph node metastasis 28. The role of chemoradiation, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, requires more studies to prove the efficacy. Maire et al. 80 have suggested that in the absence of current evidence for adjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer, patients with locally advanced malignant cystic neoplasms, especially IPMNs, should be included in the same protocols assessing adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens as patients with ductal adenocarcinoma.

The authors have published their own institutional review of SPENP 81. They reported good outcomes with a median survival of 36 months following resectional surgery of this tumour. They concluded that an increased awareness of this subgroup of pancreatic tumours is important.

Summary

Cystic neoplasms constitute an important group of pancreatic neoplasias with a good prognosis if diagnosed early and managed appropriately. MRCP is now emerging as the diagnostic modality of choice for IPMN, in addition to being able to differentiate IPMN from MCN and chronic pancreatitis. CT scan is an important modality in the diagnostic armamentarium. Cyst fluid analysis obtained using EUS following aspiration is another diagnostic modality that may help to differentiate the various cystic neoplasms. Mucinous tumours should be resected radically due to the risk of malignant potential. IPMN should be subjected to frozen section to confirm clearance of tumour intraoperatively so as to decide on the pancreatic remnant.

In case of doubt, it is best that cystic tumours are resected in centres of pancreatic surgery, as they carry a better prognosis compared with other pancreatic tumours.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

No disclosures.

References

- 1.Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic tumours of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:1001–16. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46742-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Borgne J. Cystic tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1998;85:577–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li BDL, Minnard E, Nava H. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas – a review. J La State Med Soc. 1998;150:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasslander T, Arnelo U, Albiin N, Permert J. Cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Dis. 2001;19:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000050654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda M, Sato T, Morozumi A, Fujino MA, Yoda Y, Ochiai M, et al. Morphologic changes in the pancreas detected by Screening Ultrasonography in a mass survey, with special reference to Main Duct Dilatation, Cyst Formation, and Calcification. Pancreas. 1994;9:508–12. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, Kiely JH, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg. 2004;239:651–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124299.57430.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarr MG, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM, Thompson GB, Farley DR, Farnell MB. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Benign to malignant epithelial neoplasms. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:497–509. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski L, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumours of the pancreas: new clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432–43. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199010000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas; what a clinician should know. Cancer Treatment Rev. 2005;31:507–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang HL, Shih SC, Chang WH, Wang TE, Chen J, Chan YJ. Solid pseudo-papillary tumour of the pancreas: clinical experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1403–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kehagias D, Smyrniotis V, Kalovidouris A, Gouliamos A, Kostopanagiotou E, Vessiliou J, et al. Cystic tumours of the pancreas: preoperative imaging, diagnosis and treatment. Int Surg. 2002;87:171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton SR, Altonen LA. IARC Press; Lyon: 2000. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Tumours of the digestive system; pp. 234–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarr MG, Murr M, Smyrk T, Yeo CJ, Fernandez-Del-Castillo C, Hawes RH, et al. Primary cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: neoplastic disorders of emerging importance – current state-of-the art and unanswered questions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:417–28. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grieshop NA, Wiebke EA, Kratzer SS, Madura JA. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am Surg. 1994;60:509–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim SJ, Alasadi R, Wayne JD, Rao S, Rademaker A, Bell R, et al. Preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions: cost benefit analysis and proposed management algorithm. Surgery. 2005;138:672–80. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, Wilson SD, Pitt HA. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: resect or enucleate? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:890–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-003-0035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Calan L, Levard H, Hennet H, Fingerhut A. Pancreatic cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: diagnostic value of preoperative morphological investigations. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung KL, Lau WY, Cooper JE, Li AK. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas: an uncommon presentation with hemobilia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:632–4. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baruch M, Levy Y, Goldsher D, Munichor M, Eidelman S. Massive haematemesis –presenting symptoms of cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:42–4. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.759.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raffel A, Cupisti K, Krausch M, Braunstein S, Trobs B, Goretzki PE, et al. Therapeutic strategy of papillary cystic and solid neoplasm (PSCN): a rare non-endocrine neoplasm of the pancreas in children. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi K, Ogawa Y, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Mucin hypersecreting tumours of the pancreas: assessing the grade of malignancy preoperatively. Am J Surg. 1996;171:427–31. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis RM, Jang N. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome associated with pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1380–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panwels M, Delcenserie R, Yzet T, Duchmann JC, Capron JP. Pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:485–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199709000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zamboni G, Scarpa A, Bogina G, Iacono C, Bassi C, Talamini G, et al. Mucinous cystic tumours of the pancreas: clinicopathological, features, prognosis, relationship to other mucinous cystic tumours. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:410–22. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goh BK, Tan YM, Cheow PC, Chung YF, Chow PK, Wong WK, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with mucin-production. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furukawa T, Takahashi T, Kobari M, Matsuno S. The mucus-hypersecreting tumor of the pancreas. Development and extension visualized by three-dimensional computerized mapping. Cancer. 1992;70:1505–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1505::aid-cncr2820700611>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarr MG, Carpenter HA, Prabhakar LP, Orchard TF, Hughes S, van Heerden JA, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of 84 mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas – can one reliably differentiate benign from malignant (or premalignant) neoplasms? Ann Surg. 2000;231:205–12. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adsay NV, Longnecker DS, Klimstra DS. Pancreatic tumours with cystic dilatation of the ducts: intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and intraductal papillary oncocytic neoplasms. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:16–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura A, Horinouchi M, Goto M, Nagata K, Sakoda K, Takao S, et al. New classification of pancreatic intraductal mucinous tumour by mucin expression: its relationship with potential for malignancy. J Pathol. 2002;197:201–10. doi: 10.1002/path.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adsay NV, Conlon CK, Zee SY, Brennan MF, Klimstra DS. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of in-situ and invasive carcinomas in 28 patients. Cancer. 2002;94:62–77. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furukawa T, Kloppel G, Volkan Adsay N, Albores-Saavedra J, Fukushima N, et al. Classification of types of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a consensus study. Virchows Arch. 2005;447:794–9. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohan H, Bal A, Punia RP, Attri AK. Solid and cystic papillary and epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:141–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasem A, Ali Z, Ellul J.Papillary cystic and solid tumour of the pancreas: report of a case and literature review World J Surg Oncol 2005;3:62.(online). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lew JI, Hart J, Michelassi F. Natural history of mucinous ductal ectasia of the pancreas: a case report and review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2127–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivera JA, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Pins M, Compton CC, Lewandrowski KB, Rattner DW, et al. Pancreatic mucinous ductal ectasia and intraductal papillary neoplasms. A single malignant clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg. 1997;225:637–46. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199706000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman AC, Lichtenstein JE, Dachman AH. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: radiological-pathological correlation. Radiology. 1983;149:45–50. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.1.6611949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itoh S, Ishiguchi T, Ishigaki T, Sakuma S, Maruyama K, Senda K. Mucin-producing pancreatic tumor: CT findings and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1992;183:81–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.1.1312735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curry CA, Eng J, Horton KM, Urban B, Siegelman S, Kuszyk BS, et al. CT of primary cystic pancreatic neoplasms: can CT be used for patient triage and treatment? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:99–103. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Procacci C, Megibow AJ, Carbognin G, Guarise A, Spoto E, Biasutti C, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumour of the pancreas: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 1999;19:1447–63. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no011447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koito K, Namieno T, Ichimura T, Yama N, Hareyama M, Morita K, et al. Mucin-producing pancreatic tumours: comparison of MR-cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1998;208:231–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.1.9646818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Megibow AJ, Lavelle MT, Rofsky NM. Cystic tumours of the pancreas. The radiologist. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:489–95. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taouli B, Vilgrain V, Vullierme MP, Terris B, Denys A, Sauvanet A, Hammel P, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: helical CT with histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000;217:757–64. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc24757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carbognin G. Springer Verlag; New York: 2003. Serous cystic tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeny PC, Weinstein CJ, Taft DA, Allen FH. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: new angiographic and ultrasonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;131:795–802. doi: 10.2214/ajr.131.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiersema MJ, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, Chang KJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: diagnostic accuracy and complication assessment. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1087–95. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arcidiacono PG, Carrara S. Endoscopic ultrasonography: impact on diagnosis, staging, and management of pancreatic tumours. An overview. J Pancreas (online) 2004;5:247–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brugge W, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sedlack R, Affi A, Vasquez-Sequeiros E, Norton ID, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ. Utility of EUS in the evaluation of cystic pancreatic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:543–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alles AJ, Warshaw AL, Southern JF, Compton CC, Lewandrowski KB. Expression of CA 72-4 (TAG – 72) in the fluid contents of pancreatic cysts. A new marker to distinguish malignant pancreatic cystic tumours from benign neoplasms and pseudocysts. Ann Surg. 1994;219:131–4. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199402000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassi C, Salvia R, Gumbs AA, Butturini G, Falconi M, Perderzoli P. The value of standard tumour markers in differentiating mucinous from serous cystic tumours of the pancreas: CEA, CA 19-9, CA 125, CA15-3. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:281–5. doi: 10.1007/s00423-002-0324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Chierichetti F, Liessi G, Ferlin G, Pedrazzoli S. Value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the management of patients with cystic tumours of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2001;234:675–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strobel O, Z'graggen K, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Friess H, Kappeler A, Zimmermann A, et al. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion. 2003;68:24–33. doi: 10.1159/000073222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sahani DV, Saokar A, Hahn PF, Brugge WR, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Pancreatic cysts 3 cm or smaller: how aggressive should treatment be? Radiology. 2006;238:912–19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, Wilson SD, Pitt HA. Cystic pancreatic neoplasias: enucleate or resect? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:890–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-003-0035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen PJ, D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Jaques DP, Coit DG, Jarnagin WR, et al. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:572–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237652.84466.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siech M, Thumerer SU, Henne-Bruns D, Beger HG. Cystic tumours of the pancreas – radical or organ-preserving resection? Chirurg. 2004;75:615–21. doi: 10.1007/s00104-004-0842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bassi C, Salvia R, Molinari E, Biasutti C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World J Surg. 2003;27:319–23. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumour growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413–21. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179651.21193.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Talamini MA, Moesinger R, Yeo CJ, Poulouse B, Hruban RH, Cameron JL, et al. Cystadenomas of the pancreas: is enucleation an adequate operation? Ann Surg. 1998;227:896–903. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Van de Velde CJ, Peros G. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a surgical perspective. Surg Oncol. 2005;14:155–78. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salvia R, Festa L, Butturini G, Tonsi A, Sartori N, Biasutti C, et al. Pancreatic cystic tumours. Minerva Chir. 2004;59:185–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Compagno J, Oertel JE. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with overt and latent malignancy (cystadenocarcinomas and cystadenoma): a clinicopathologic study of 41 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:573–80. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Centeno BA, Lewandrowski KB, Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Southern JF. Cyst cytologic analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:483–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Warren KW, Athanassiades S, Frederick P, Kune GA. Surgical treatment of pancreatic cysts: review of 183 cases. Ann Surg. 1966;163:886–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196606000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iacono C, Bortolasi L, Serio G. Is there a place for central pancreatectomy in pancreatic surgery? Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:509–16. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lurkish JR, Rothstein JH, Petruziello M, Kitely R, Denobile J, Soballe P. Spleen-preserving pancreatectomy for cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Am Surg. 1999;65:596–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kimura W, Fuse A, Hirai I, Suto K, Suzuki A, Moriya T, et al. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with preservation of the splenic artery and vein for intraductal papillary mucinous tumour (IPMT) Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2242–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Molino D, Perotti P, Antropoli C, Bottino V, Napoli V, Fioretto R. Central segmental pancreatectomy in benign and borderline neoplasms of the pancreatic isthmus and body. Chir Ital. 2001;53:319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chari ST, Yadav D, Smyrk TC, DiMagno EP, Miller JP, Raimondo M, et al. Study of recurrence after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1500–7. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walsh RM, Vogt DP, Henderson M, Zuccaro G, Vargo J, Dumot J, et al. Natural history of indeterminate pancreatic cysts Surgery 2005;138:665–70; discussion 670–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doberstein C, Kirchner R, Gordon L, Silberman AW, Morgenstern L, Shapiro S. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Mt Sinai J Med. 1990;57:102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.George DH, Murphy F, Michalski R, Ulmer BG. Serous cystadenocarcinomas of the pancreas – a new entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:61–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsuda Y, Imai Y, Kawata S, Nishikawa M, Miyoshi S, Saito R, et al. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with multiple hepatic metastases: a case report. Gastroenterol Jap. 1987;22:379–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02774265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fried P, Cooper J, Balthazar E, Fazzini E, Newall J. A role for radiotherapy in the treatment of solid and papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Cancer. 1985;56:2783–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851215)56:12<2783::aid-cncr2820561211>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Das G, Bhuyan C, Das BK, Sharma JD, Saikia BJ, Purkystha J. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for papillary solid and cystic neoplasm of pancreas. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:188–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brenin DR, Talamonti MS, Tang EY, Sener SF, Haines GK, Joehl RJ, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study including DNA flow cytometry. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1048–54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430100026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maire F, Hammel P, Terris B, Paye F, Scoazec JY, Cellier C, et al. Prognosis of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas after surgical resection. Comparison with pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2002;51:717–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.5.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patil TB, Shrikhande SV, Kanhere HA, Saoji RR, Ramadwar MR, Shukla PJ. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a single institution experience of 14 cases. HPB. 2006;8:148–50. doi: 10.1080/13651820510035721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]