Abstract

Objective. We conducted a study to examine recent trends in population-based utilization rates for liver resection surgery in England, to help identify potentially unmet healthcare need and to help inform future service planning. Materials and methods. Hospital Episodes Statistics data were analysed for the 5-year period 2000–1 to 2004–5 to identify episodes of care relating to liver resection surgery (defined as OPSC IV codes J21 to J24, J31, J38 and J39). Results. In England, the liver excision surgery population access rate was 1.82 and 2.95/100 000 general population in 2000–1 and 2004–5, respectively – a 62% increase during the 5-year study period, or a mean 12% annual increase. About two-thirds of all liver resection surgery (69%) related to metastatic liver disease. Between English regions, utilization rates ranged from 0.5 to 4.5/100 000 general population in 2000–1; and from 0.8 to 4.6/100 000 general population in 2004–5. Discussion. In recent years, a rapid increase in liver resection surgery activity has been observed. Most of the activity was related to metastatic disease. There was substantial regional variation in population utilization rates within the same country. This variation is unlikely to represent regional differences in disease burden and healthcare need.

Introduction

Liver resection surgery has historically had a narrow spectrum of indications. Increasingly over recent years, evidence suggests that liver resection surgery could be an effective intervention for certain patients suffering from metastatic liver disease. This is particularly true for colorectal liver metastases, where 5-year survival rates of between 30% and 47% have been reported 1,2,3,4. In this respect, metastatic liver disease is rather unique among common presentations of malignant disease, as among surgically treatable patients it has cure rates that exceed those observed in many other primary cancers of solid organs (e.g. oesophageal or pancreatic cancers).

Further advances in operative and haemostatic techniques over recent years are believed to have made liver resection surgery both safer and more effective, and may have increased the proportion of patients for whom surgical resection is possible by up to 20% 5. Preoperative portal vein embolization, two-stage hepatectomy (i.e. resection of different affected parts of the liver during more than one operation) and administration of preoperative ‘down-staging’ chemotherapy, may have also rendered operable a patient subgroup previously thought to be ineligible for surgery 5,6,7. Conversely, advances in imaging techniques (e.g. positron emission tomography (PET) and PET-CT imaging) may have diminished the ‘pool’ of potentially eligible patients, because of better detection of previously undetectable disseminated disease, or may do so in the future. Therefore, there is currently some uncertainty about the percentage of patients presenting with metastatic liver disease who have surgically treatable illness.

Liver surgery is dependent on the availability of relevant surgical expertise, which has historically been limited. It could therefore be postulated that diffusion of liver resection surgery might have been slow, and that provision of this type of surgery may have been below the healthcare need levels that could be theoretically expected. A previous study from an English liver surgery unit has indicated a theoretical healthcare need of approximately 3.9 liver resection surgery episodes for metastatic disease of the liver from colorectal primaries per 100 000 general population 8. However, this evidence relates to only one study and research setting and to metastatic liver disease from colorectal primaries alone, i.e. excluding other potentially important indications, such as metastatic disease from other primary sites and primary liver neoplasms. We therefore conducted a survey using routine data to examine historical and recent utilization levels, comparing them to theoretically expected healthcare need, and to examine whether there was variation over time in population access rates by region.

Materials and methods

Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data were analysed for the period 2000–1 to 2004–5 to identify episodes of care relating to liver resection surgery (defined as episodes of care with OPSC IV codes J21 to J24, J31, J38 and J39 in the primary procedure position). The HES dataset contains information about clinical episodes of care that take place in English hospitals of the National Health Service (NHS) 9. For relevant episodes of care as defined above, the following information was also obtained: regional office of patient residence, age, sex and diagnosis (defined as the International Classifications of Diseases-10 diagnostic code in the primary diagnosis field). Office for National Statistics data were used in the denominators, for calculation of general population access rates. Descriptive analysis was subsequently undertaken.

Results

Among residents in England who were treated in NHS hospitals, there were overall 896 care episodes relating to liver resection surgery in 2000–1, increasing to 1451 such episodes in 2004–5. For the whole of England, the population access rate for liver excision surgery increased from 1.82/100 000 general population in 2000–1 to 2.23, 2.33, 2.83 and 2.95/100 000 general population in the years 2001–2, 2002–3, 2003–4 and 2004–5, respectively (Table I). This represents a 62.09% increase during the 5-year study period (2004–5 over 2000–1), or a mean 12.42% annual increase, for each year of the study period.

Table I. Number and rate (per 100 000 general resident population) of liver surgery resection operations, by year of operation and English region, 2000–1 to 2004–5.

| 2000–1 |

2001–2 |

2002–3 |

2003–4 |

2004–5 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Population | Number of operations | Rate per 100 000* | Number of operations | Rate per 100 000* | Number of operations | Rate per 100 000* | Number of operations | Rate per 100 000* | Number of operations | Rate per 100 000* |

| East Midlands | 4 172 179 | 61 | 1.46 | 80 | 1.92 | 99 | 2.37 | 119 | 2.85 | 111 | 2.66 |

| Eastern | 5 388 154 | 45 | 0.84 | 34 | 0.63 | 50 | 0.93 | 64 | 1.19 | 73 | 1.35 |

| London | 7 172 036 | 127 | 1.77 | 194 | 2.70 | 215 | 3.00 | 216 | 3.01 | 248 | 3.46 |

| North East | 2 515 479 | 114 | 4.53 | 134 | 5.33 | 64 | 2.54 | 62 | 2.46 | 72 | 2.86 |

| North West | 6 729 800 | 98 | 1.46 | 130 | 1.93 | 170 | 2.53 | 243 | 3.61 | 225 | 3.34 |

| South East | 8 000 550 | 169 | 2.11 | 186 | 2.32 | 189 | 2.36 | 246 | 3.07 | 298 | 3.72 |

| South West | 4 928 458 | 26 | 0.53 | 28 | 0.57 | 30 | 0.61 | 37 | 0.75 | 39 | 0.79 |

| West Midlands | 5 267 337 | 114 | 2.16 | 123 | 2.34 | 161 | 3.06 | 188 | 3.57 | 155 | 2.94 |

| Yorkshire–Humberside | 4 964 838 | 142 | 2.86 | 189 | 3.81 | 166 | 3.34 | 217 | 4.37 | 230 | 4.63 |

| Grand total | 49 138 831 | 896 | 1.82 | 1098 | 2.23 | 1144 | 2.33 | 1392 | 2.83 | 1451 | 2.95 |

*General population.

Of all liver excision surgery episodes during the study period, 55.51% were in men, and 44.46% in women. The mean age of patients treated with liver resection was 57.18, 57.56, 59.19, 59.10 and 59.27 years for the years 2000–1 to 2004–5, respectively.

Of all liver excision surgery episodes during the study period, 68.68% had a diagnosis of metastatic disease (Table II); 11.55% had a diagnosis of primary liver cancer; 4.80% had a diagnosis of either a benign neoplasm or a neoplasm of uncertain or unknown behaviour; 1.15% had a diagnosis of congenital malformations of the hepatobiliary system; 0.89% had a diagnosis of traumatic injury and 12.92% had other diagnoses.

Table II. Breakdown and proportion (in relation to all procedures) of metastatic liver disease coded diagnosis among patients treated with liver resection surgery, 2000–1 to 2004–5.

| ICD-10 code | Description of code | Number of episodes | %* |

|---|---|---|---|

| C78 | Secondary malignant neoplasm of respiratory and digestive organs | 3698 | 61.83 |

| C18 | Malignant neoplasm of colon | 117 | 1.96 |

| C23 | Malignant neoplasm of gallbladder | 65 | 1.09 |

| C19 | Malignant neoplasm of rectosigmoid junction | 60 | 1.00 |

| C20 | Malignant neoplasm of rectum | 40 | 0.67 |

| C80 | Malignant neoplasm without specification of site | 20 | 0.33 |

| C25 | Malignant neoplasm of pancreas | 15 | 0.25 |

| C16 | Malignant neoplasm of stomach | 13 | 0.22 |

| C26 | Malignant neoplasm of other and ill-defined digestive organs | 12 | 0.20 |

| C64 | Malignant neoplasm of kidney, except renal pelvis | 13 | 0.22 |

| C74 | Malignant neoplasm of adrenal gland | 8 | 0.13 |

| C17 | Malignant neoplasm of small intestine | 7 | 0.12 |

| C79 | Secondary malignant neoplasm of other sites | 7 | 0.12 |

| C49 | Malignant neoplasm of other connective and soft tissue | 5 | 0.08 |

| C15 | Malignant neoplasm of oesophagus | 4 | 0.07 |

| C56 | Malignant neoplasm of ovary | 4 | 0.07 |

| C77 | Secondary and unspecified malignant neoplasm of lymph node | 5 | 0.09 |

| C48 | Malignant neoplasm of retroperitoneum and peritoneum | 3 | 0.05 |

| C67 | Malignant neoplasm of bladder | 2 | 0.03 |

| D01 | Carcinoma in situ of other and unspecified digestive organs | 2 | 0.03 |

| C08 | Malignant neoplasm of other and unspecified major salivary glands | 1 | 0.02 |

| C34 | Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | 1 | 0.02 |

| C43 | Malignant melanoma of skin | 1 | 0.02 |

| C45 | Mesothelioma | 1 | 0.02 |

| C61 | Malignant neoplasm of prostate | 1 | 0.02 |

| C66 | Malignant neoplasm of ureter | 1 | 0.02 |

| C68 | Malignant neoplasm of other and unspecified urinary organ | 1 | 0.02 |

| D03 | Melanoma in situ | 1 | 0.02 |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases-10.

*In relation to all procedures, whatever the ICD-10 diagnosis.

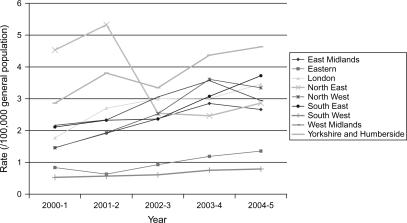

There was considerable variation in population rates of liver resection surgery per 100 000 general population between different English regions during the study period (Figure 1 and Table I). Rate ratios between the highest and lowest (in terms of utilization rates) English regions were 8.6 (absolute rate range = 0.5–4.5/100 000 general population) in 2000–1 and 5.9 in 2004–5 (absolute rate range = 0.8–4.6/100 000 general population).

Figure 1. .

Rate of liver excision surgery (100 000 general population) by English region and year (2000–1 and 2004–5).

Discussion

In England and during a recent time period, evidence of a relatively rapid increase in liver resection surgery activity has been observed. There was little change in the mean age of operated patients. About two-thirds of all activity was related to metastatic disease of the liver, and about four-fifths of all activity was related to cancer (secondary or primary). Substantial regional differences in population access rates to liver surgery activity were observed, and persisted during the study period.

About two-thirds of liver resection surgery activity related to metastatic liver disease. The nature and source of the data used (HES dataset) make it impossible to have a precise estimate of the proportion of such activity relating to metastatic disease from colorectal cancer primaries. However, even if one assumes that all metastatic liver disease presentations among patients treated with liver resection surgery did relate to metastatic disease from colorectal primaries, this would have meant that the liver resection activity actually observed for colorectal liver metastases was about half the previously theoretically predicted population rate levels, i.e. 3.9/100 0000 8.

A considerable degree of variation in relation to population-based utilization rates was observed between the populations of different English regions. Given this many-fold variation, this is very unlikely to be associated with regional differences in disease burden. Therefore, it most likely reflects differences either in care pathways and clinical management practices (e.g. primary and secondary care physicians not always either choosing or being able to refer patients to liver surgery centres) and/or differences in relation to capacity and availability of surgical expertise. However, it is impossible to answer this question with empirical evidence, given the retrospective nature of this study and the data available. Nevertheless, given that the variation in utilization rates is unlikely to represent differences in disease burden, this inequitable distribution should inform and be addressed by future policy initiatives.

Using HES, we calculated that during the same study period (2000–1 to 2004–5), about 1000 pancreatic excision surgery procedures were carried out annually in the UK (data not shown). This means that the volume of liver resection surgery currently exceeds that of pancreatic excision surgery. Pancreatic and liver surgery are usually, but not always, served by the same surgical subspecialty. Pancreatic surgery in the UK has undergone a great degree of centralization to tertiary centres over recent years, following the 2001 Improving Outcomes Guidance for Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers 10. This important policy document did not include any reference to liver surgery, which therefore remains bereft of any authoritative national or professional guidance about the appropriate minimum annual activity and population catchment size for each centre, in order to both quality assure outcomes and to optimize the cost-effectiveness of services. Recent guidelines have not stipulated such requirements to the level of detail required for service planning 11. We argue that a national policy for appropriate designation of liver surgery services is necessary to help best accommodate the recent and potential future growth in healthcare need for this potentially life-saving surgical intervention.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

No disclosures.

References

- 1.Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:982–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei AC, Greig PD, Grant D, Taylor B, Langer B, Gallinger S. Survival after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: a 10-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:668–76. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leporrier J, Maurel J, Chiche L, Bara S, Segol P, Launoy G. A population-based study of the incidence, management and prognosis of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:465–74. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjovall A, Jarv V, Blomqvist L, Singnomklao T, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, et al. The potential for improved outcome in patients with hepatic metastases from colon cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:834–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fusai G, Davidson BR. Strategies to increase the resectability of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Dig Surg. 2003;20:481–96. doi: 10.1159/000073535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam R, Lucidi V, Bismuth H. Hepatic colorectal metastases: methods of improving resectability. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:659–71. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vauthey JN, Zorzi D, Pawlik TM. Making unresectable hepatic colorectal metastases respectable – does it work? Semin Oncol. 2005;32(6 Suppl 9):S118–S122. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majeed AW, Price C. Resource and manpower calculations for the provision of hepatobiliary surgical services in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:91–5. doi: 10.1308/003588404322827455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health. Hospital Episodes Statistics. http://www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Statistics/HospitalEpisodeStatistics/fs/en(accessed February 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidance on Commissioning Cancer Services Improving Outcomes in Upper Gastro-intestinal Cancers. The Manual. Department of Health. http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/02/78/04080278.pdf(accessed February 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garden OJ, Rees M, Poston GJ, Mirza D, Saunders M, Ledermann J, et al. Guidelines for resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 3):iii1–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]