Abstract

Psychological stressors have a prominent effect on sleep in general, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in particular. Disruptions in sleep are a prominent feature, and potentially even the hallmark, of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Ross et al., 1989). Animal models are critical in understanding both the causes and potential treatments of psychiatric disorders. The current review describes a number of studies that have focused on the impact of stress on sleep in rodent models. The studies are also summarized in Table 1, summarizing the effects of stress in 4-hr blocks in both the light and dark phases. Although mild stress procedures have sometimes produced increases in REM sleep, more intense stressors appear to model the human condition by leading to disruptions in sleep, particularly REM sleep. We also discuss work conducted by our group and others looking at conditioning as a factor in the temporal extension of stress-related sleep disruptions. Finally, we attempt to describe the probable neural mechanisms of the sleep disruptions. A complete understanding of the neural correlates of stress-induced sleep alterations may lead to novel treatments for a variety of debilitating sleep disorders.

Keywords: Amygdala, corticotropin-releasing factor, stress, sleep, REM, PTSD

Stress, although a potentially confusing term (see Day, 2005), is believed to be a significant factor in a variety of health problems (Korte et al., 2005). A reasonable definition of stress is a stimulus or situation that challenges homeostasis and induces a multi-system response (Day, 2005). Stress research historically has focused on physiological changes in an organism after exposure to some stress-inducing procedure. Levels of corticosterone, the major adrenocortical glucocorticoid hormone in rodents, are often used as an index of acute stress (Brennan et al., 2000; Ottenweller et al., 1989), as are plasma levels of epinephrine (Lundberg, 2005). Exposure to stress in humans is related to increased incidences of a number of psychiatric illnesses, including posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] (Brady & Sinha, 2005) and other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance-related disorders.

While other anxiety disorders and depression may be induced or exacerbated by stress, PTSD by definition only occurs after exposure to a severe stressor (DSM-IV, 1994). This is not to say that stress alone leads to the development of psychiatric disorders. For example, approximately only one-third of patients who have been exposed to a traumatic stressor develop long-term PTSD (Zatzick et al., 1997). Animal models can provide an understanding of how organisms respond to stress, and the nature of inter-individual differences in the stress response. Given the importance of sleep disturbances in the PTSD symptom complex, both animal and pre-clinical studies of the effects of stress on sleep may have particular relevance to this disorder.

PTSD is an Axis I anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to a traumatic event (Schnurr & Green, 2004). It has a number of clinical features, and it can be severely debilitating. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, 4th Edition- Revised (1994) lists a number of major diagnostic criteria, which include autonomic, behavioral, and somatic symptoms. Of all the chronic symptoms associated with PTSD, the changes in sleep may be the most debilitating. We have previously argued that the sleep disturbance in PTSD is, in fact, the hallmark of the disorder (Ross et al., 1989). This is based on several related pieces of evidence; first, the prevalence of anxiety dreams in patients with PTSD is high (Harvey et al., 2003). Second, no other psychiatric disorder is characterized by repetitive, stereotypical anxiety dreams. Since dreams with the highest emotional and aggressive content occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (McNamara et al., 2005), it is logical to look for REM sleep abnormalities in PTSD patients, and these have been reported by our group (Ross et al., 1994) and others (e.g., Mellman et al., 1997). It should be noted that the sleep disturbances in PTSD are not limited to REM sleep (see Neylan et al., 2006).

A report from Mellman and colleagues (1995) is particularly interesting in that PTSD patients showed reductions in REM sleep time, while patients with major depression did not. This suggests that REM sleep changes may be a divergent marker for these two disorders, which otherwise have many overlapping features. Apart from a reduction in the total amount of REM sleep, there have been reports of other changes in REM sleep. Mellman et al. (1995) and Ross et al. (1994) reported an increase in REM density (number of rapid eye movements/REM sleep time) in combat-related PTSD. Interestingly, REM density appears to be related to the intensity of mental activity during sleep (Smith et al., 2004). A decrease in average REM sleep episode length within a month of psychological traumatization has been shown to predict the severity of symptoms of PTSD at follow-up in one study (Mellman et al., 2002). This suggests that understanding the changes in sleep that occur early in the pathogenesis of the disorder may lead to prevention strategies and perhaps improved therapies.

Our plan in the current paper is to review the literature on stress-induced changes in sleep in rats and mice. We will first review studies using immobilization, a common stress procedure, before considering studies that utilized electric shock. Next we will describe some of our work and the work of others on how conditioned stimuli associated with stressors produce changes in sleep similar to the stressors themselves. Finally, we will review some potential physiological mechanisms that may mediate the sleep changes.

Rodent Models of Stress-Induced Changes in Sleep

In recent years there have been a number of studies of the effects of stress on sleep in rats and mice. We have chosen to review the studies by stressor type, before drawing global conclusions. Further, we have chosen not to address the significant number of studies that have used either total sleep or REM sleep deprivation as a stressor (see McEwen, 2006, for a review). This is because a sleep or REM sleep rebound could confound the direct effect of stress. In fact, investigations of the effects of stress on sleep evolved from sleep deprivation studies. Jouvet (1994) noted that a prominent hypothesis explaining the increase in sleep following sleep deprivation needed to take account of the stress inherent in the deprivation procedure. It was therefore in his laboratory (Rampin et al., 1991) that an early study was conducted looking directly at the effect of stress on sleep.

Since Rampin’s seminal study in 1991, there have been numerous investigations of the effects of stress on the sleep of rodents. The primary stressors used in these studies have been immobilization and mild electric shock, with few reports using other modalities. More recently, this work has been expanded to include not only unconditioned stressors but conditioned stressors as well. Numerous strains of both rats and mice have been used, and laboratories generally have not utilized identical or even highly similar stressor paradigms. As this field moves forward, it will become important to understand the differences that strain and stressor paradigms play in the sleep/wakefulness [S/W] response of rodents to stress. To begin to define the current landscape, we have summarized the salient methods and results from all studies of which we are aware. This summary is presented as Table 1. For clarity, we have decided to describe the significant results of each study in a uniform manner whenever possible. Thus, we divided both the light and dark phases of the S/W cycle into 4-hour blocks (early, mid, and late), and we describe changes in terms of these periods for each study.

Table 1.

| Reference/Study | Stressor | Species | Strain | Stress Paradigm | Stress Timing | Effects on Total Sleep | Effects on NREM Sleep | Effects on REMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHOCK STRESS | ||||||||

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 1 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | None | None | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 2 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | None | None | Mid light phase decrease and late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 3 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | None | None | Mid light phase decrease and late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 4 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Late light phase increase. | Late light phase increase | Mid light phase decrease and late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 1 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid light phase decrease | Mid light phase decrease. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 2 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid light phase decrease | None | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 3 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid light phase decrease | Mid light phase decrease. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 4 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid light phase decrease | Mid light phase decrease and early dark phase decrease. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 1 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | None | None | None |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 2 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Late dark phase decrease | Mid dark phase increase and late dark phase decrease. | Late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 3 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid dark phase increase then late dark phase decrease. | Mid dark phase increase then late decrease. | Late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 4 Cued shock training - 15 tone-footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec shocks | Training within 2 h after light onset | Mid light phase increase and late increase/late dark phase increase then decrease | Mid light phase increase late light phase decrease/mid dark phase increase then late dark phase decrease. | Late light phase decrease/mid dark phase increase and late dark phase decrease. |

| Vazquez-Palacious & Velazquez-Moctezuma 2000 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Unavoidable footshocks, 5 min, 1 /sec, 0.2 sec, 3 mA shocks | Just before light onset | Middle dark phase increase. | None. | Early through mid light phase decrease/middle dark phase increase. |

| Papale et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 1 Unavoidable footshocks - 2 mA, 0.25 sec, 4–6 random shocks per min | 2–3 and 9–10 h after light onset. | No change. | No change | No change. |

| Papale et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 2 Unavoidable footshocks - 2 mA, 0.25 sec, 4–6 random shocks per min | 2–3 and 9–10 h after light onset. | No change. | No change | General dark phase increase. |

| Papale et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 3 Unavoidable footshocks – 2 mA, 0.25 sec, 4–6 random shocks per min | 2–3 and 9–10 h after light onset. | General light phase decrease. | General light phase decrease. | General light phase decrease/general dark phase increase. |

| Papale et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 4 Unavoidable footshocks – 2 mA, 0.25 sec, 4–6 random shocks per min | 2–3 and 9–10 h after light onset. | General light phase decrease. | General light phase decrease. | General light phase decrease/general dark phase increase. |

| Pawlyk et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Sprague Dauley | Day 1 Postraining Contextual shock training - 5 random 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 30 minutes | 3–3.5 h after light onset 24 h before recording period | Mid light phase increase (only 4 hr of recording). | No change (only 4 hr of recording) | Mid light phase increase (only 4 hr of recording). |

| Pawlyk et al. 2005 | Shock | Rat | Sprague Dauley | Day 2 Posttraining Contextual shock training , 5 random 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 30 minutes | 3–3.5 h after light onset 48 h before recording period | Mid light phase increase (only 4 hr of recording). | Mid light phase increase (only 4 hr of recording). | Mid light phase increase (only 4 hr of recording). |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 1 Controllable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | Decrease during entire day. | n.r. | Decrease during entire day. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 2 Controllable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | Decrease during entire day. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 3 Controllable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | Decrease during entire day. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 7 Controllable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 14 Controllable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 1 - Controllable footshock | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | Increase during entire day. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 2 - Controllable footshock | Throughout day | Increase during entire day. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 7 - Controllable footshock | Throughout day | Increase during entire day. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 1 Uncontrollable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | Decrease during entire day. | n.r. | Decrease during entire day. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 2 Uncontrollable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 3 Uncontrollable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 7 Uncontrollable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 14 Uncontrollable footshock - 280 trials/day of 5 sec each of 0.16 mA, 0.32 mA, 0.65 mA, 1.3 mA, 2.6 mA | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 1 - Uncontrollable footshock | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 2 - Uncontrollable footshock | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Kant et al. 1995 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Recovery Day 7 - Uncontrollable footshock | Throughout day | No change. | n.r. | No change. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | No change. | Increase late light phase. | Decrease mid light phase/decrease late dark phase. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 2 – Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | No change. | No change. | Decrease mid light phase. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 3 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Increase late light phase. | Increase late light phase. | Decrease mid light phase. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Day 4 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Increase late light phase/decrease late dark phase. | Increase late light phase. | Decrease mid light phase. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | No change. | No change. | Mid to late light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 2 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Decrease mid light. | Decrease mid light. | Late light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 3 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | No change. | No change. | Late light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 4 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Decrease early dark. | Decrease early dark. | Mid light phase decrease/mid to late dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Mid and late light phase decreases. | Mid light phase decrease. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 2 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Mid light phase decrease. | Mid light phase decrease. | Might light phase decrease/mid dark phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 3 - Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | Mid light phase decrease. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Shock | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Day 4 – Contextual shock training, 15 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | Within first 2–2.25 h of light | No change. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease/mid dark phase decrease. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Fischer | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | No change. | No change. | General increase throughout dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Fischer | Day 2 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | General increase throughout dark phase. | No change. | General increase throughout dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Lewis | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | General increase throughout dark phase. | General increase throughout dark phase. | General decrease throughout light phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Lewis | Day 2 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | No change. | General increase throughout dark phase. | General decrease throughout light phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 1 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | General increase throughout dark phase/general decrease throughout light phase. | General increase throughout dark phase. | General decrease throughout light phase/general increase throughout dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Day 2 - Contextual shock training, 20 0.2mA, 0.5 sec footshocks over 20 min | Fifth hour after lights on. | General increase throughout dark phase/general decrease throughout light phase. | General increase throughout dark phase/general decrease throughout light phase. | General decrease throughout light phase/general increase throughout dark phase. |

| Adrien et al. 1990 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 0 Training (Helpless) - Inescapable footshock, 60 randomized 0.8 mA, 15 sec footshocks every min +/− 15 sec | Early morning. | No change. (n.r. after 3 hr) | Decrease (SWSI) mid light phase (n.r. after 3 hr) | Decrease mid light phase (n.r. after 3 hr) |

| (Control) | No change. (n.r. after 3 hr) | No change. (n.r. after 3 hr) | No change (n.r. after 3 hr) | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 1 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | No change. | General increase (SWS1) throughout dark. | No change. |

| (Control) | No change | No change | No change | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 2 Posttraining (Helpless) - Shuttle box testing 1 | Early morning. | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3 h) | Increase (SWSII) mid light phase (n.r. after 3 h) | No change. |

| (Control) | No change. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease (n.r. after 3 hr) | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 3 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | No change. | No change. | No change. |

| (Control) | No change. | No change. | No change. | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 4 Posttraining (Helpless) - Shutte box testing 2 | Early morning. | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3 h) | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3 h) |

| (Control) | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 7 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | General dark phase decrease. | No change. | General dark phase decrease. |

| (Control) | No change. | No change. | General dark phase decrease. | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 8 Posttraining (Helpless) - Shuttle box testing 3 | Early morning. | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | Mid light phase increase (SWS2) (n.r. after 3 hr) | Increase mid light phase (n.r. after 3 hr) |

| (Control) | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3h) | Mid light phase increase (SWS2) (n.r. after 3 hr) | No change (n.r. after 3 h) | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 9 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | General decrease during dark. | No change. | General decrease during dark. |

| (Control) | No change. | No change. | General decrease during dark. | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 10 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | General increase during light and dark. | General increase (SWS2) during light. | General decrease during dark. |

| (Control) | General decrease during dark. | General decrease (SWS2) during dark. | General decrease during dark. | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 11 Posttraining (Helpless) - Shuttle box testing 4 | Early morning. | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3 h) | Mid light phase increase (SWS2) (n.r. after 3 h) | No change (n.r. after 3h) |

| (Control) | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 3 h) | Mid light phase increase (SWS2) (n.r. after 3 h) | No change (n.r. after 3h) | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 14 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | General increase during light. | General increase (SWS2) during light. | General decrease during dark. |

| (Control) | General increase during light. | General increase (SWS2) during light. | General decrease during dark. | |||||

| Adrien et al. 1991 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 15 Posttraining (Helpless) | Early morning. | General increase during dark. | General decrease (SWS1) during light; general increase (SWS2) during light. | General decrease during dark. |

| (Control) | General increase during dark. | General decrease (SWS1) during light. | General decrease during dark. | |||||

| Sanford et al. 2001 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 1 Cued shock training - 15 light:footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | 4.5 h after lights on | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | Decrease mid light phase (n.r. after 4 h) |

| Sanford et al. 2001 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 2 Cued shock training - 15 light:footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | 4.5 h after lights on | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | Decrease mid light phase (n.r. after 4 h) |

| Sanford et al. 2001 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 3 Cued shock training - 15 light:footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | 4.5 h after lights on | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | No change (n.r. after 4 h) |

| Sanford et al. 2001 | Shock | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Day 4 Cued shock training - 15 light:footshock pairings, 0.5 mA, 0.5 sec footshocks | 4.5 h after lights on | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | No change (n.r. after 4 h) | Decrease mid light phase (n.r. after 4 h) |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Cued shock training, 1 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on | n.r. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Cued shock training, 1 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on, 24 h before recording | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Cued shock training, 15 tone:footshock pairings 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on | n.r. | Mid light phase decrease; late dark phase increase. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Cued shock training, 15 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on, 24 h before recording | n.r. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 3 Posttraining - Cued shock training, 15 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on. | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 5 Posttraining - Cued shock training, 15 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on. | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Shock | Mouse | BalbC | Day 7 Posttraining - Cued shock training, 15 tone:footshock pairing 0.2 mA, 0.5 sec footshock | Within first 2 h of lights on. | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Palma et al. 2000 | Shock | Rat | Wistar | Unavoidable footshocks, 1 h, 2 mA, 0.1 s, 4–6 shocks /min, variable inter-shock interval | Started 2–2.5 h after lights on | Decrease mid light (data for 6 h post-shock only) | No change (data for 6 h post-shock only). | Decrease mid light (data for 6 h post-shock only). |

| FEARFUL CUES | ||||||||

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Fearful audio cues from 4 day of shock training (WHEN PRIOR????) | At 4 h after light onset | None. | None. | Mid light phase decrease/early dark phase decrease.. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Fearful audio cues from 4 day of shock training | At 4 h after light onset | None. | Late dark phase increase. | Mid light phase decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003a | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Fearful audio cues from 4 day of shock training | At 4 h after light onset | Mid light phase increase. | Mid light phase increase. | Decrease throughout dark phase.. |

| Pawlyk et al 2005 | Fearful audio cues | Rat | Sprauge Dauley | Fearful contextual cues from 1 day of shock training 24-h prior | 3 h after light onset | Mid light phase decrease (only 4 hr of recording) | No change (only 4 hr of recording) | Mid light phase decrease (only 4 hr of recording). |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Contextual cues | Mouse | C57Bl6 | Fearful contextual cues from 4 days of shock training 5–6 days prior | Within first 2 h of light | No change. | No change. | Mid light decrease/late dark decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Contextual cues | Mouse | BalbC | Fearful contextual cues from 4 days of shock training 5–6 days prior | Within first 2 h of light | No change. | Late dark increase. | Mid light decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003b | Contextual cues | Mouse | C57Bl6/BalbC F1 | Fearful contextual cues from 4 days of shock training 5–6 days prior | Within first 2 h of light | Mid light decrease. | Mid light decrease. | Mid light decrease/mid dark decrease. |

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 6 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of single-shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 7 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | No change. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 13 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of single-shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 14 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | No change. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 20 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of single-shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 21 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | No change. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 27 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of single-shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 28 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | No change. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 34 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of single-shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 35 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | No change. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 6 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (15) shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 7 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | Early dark phase decrease. | Late light phase decrease. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 13 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (15) shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | Late light phase increase. | No change. |

| Day 14 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | Early dark phase decrease. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 20 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (15) shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 21 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | Early dark phase decrease. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 27 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (15) shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 28 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | Early dark phase decrease. | No change. | ||||

| Sanford et al. 2003c | Fearful audio cues | Mouse | BalbC | Day 34 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (15) shock training | 4 h after light onset | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Day 35 Posttraining | 24 h after exposure to cues | n.r. | Early dark phase decrease. | No change. | ||||

| Tang et al. 2005b | Fearful contextual cues | Rat | Fisher | Day 1 Posttraining - 30 minutes in fearful contextual from 2 days of contextual training | Fifth hour after lights on. | No change. | No change. | General increase throughout dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Fearful contextual cues | Rat | Lewis | Day 1 Posttraining - 30 minutes in fearful contextual from 2 days of contextual training | Fifth hour after lights on. | General increase throughout light phase. | No change. | General decrease throughout light phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005b | Fearful contextual cues | Rat | Wistar | Day 1 Posttraining - 30 minutes in fearful contextual from 2 days of contextual training | Fifth hour after lights on. | General decrease throughout light phase/general increase throughout dark phase. | General decrease during light phase/general increase throughout dark phase. | General decrease throughout light phase. |

| Jha et al. 2005 | Fearful audio cues | Rat | Sprauge Dauley | Day 1 Posttraining - Fearful audio cues from 1 day of multiple (5) tone:footshock pairings | 3 h after light onset | No change (n.r. after 4 h). | n.r. | Mid light phase decrease (n.r. after 4 h) |

| Jha et al. 2005 | Explicitly unpaired audio cues | Rat | Sprauge Dauley | Day 1 Posttraining - Explicitly unpaired audio cues from tone:footshock control group | 3 h after light onset | No change (n.r. after 4 h). | n.r. | Mid light phase increase (n.r. after 4 h) |

| IMMOBILIZATION | ||||||||

| Meerlo et al. 2001 | Immobilisation stress | Mouse | C57Bl6 | 1 h immobilisation. | 6 h after light onset | n.r. | Early and late dark phase increases. | Mid light phase decrease and late light phase increase/Increase throughout dark phase. |

| Meerlo et al. 2001 | Immobilisation stress | Mouse | BalbC | 1 h immobilisation. | 6 h after light onset | n.r. | Late light increase/early to mid dark phase increase. | Mid light phase decrease/Early to mid dark phase increase. |

| Vazquez-Palacious & Velazquez-Moctezuma 2000 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 2 hr immobilisation. | 2 h before light onset. | Early and late light phase increases/early through late dark phase increases. | Increases throughoutlight and dark phases. | Late light phase increase/increase throughout dark. |

| Papale et al 2005 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 22 h/day immobilisation, 1 h breaks 9.00 and 16.00 – Day 1 | Near continuous. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General light and dark phase decreases. |

| Papale et al 2005 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 22 h/day immobilisation, 1 h breaks 9.00 and 16.00 – Day 2 | Near continuous. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General dark phase decreases. |

| Papale et al 2005 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 22 h/day immobilisation, 1 h breaks 9.00 and 16.00 – Day 3 | Near continuous. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General light and dark phase decreases. | General light and dark phase decreases. |

| Papale et al 2005 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 22 h/day immobilisation, 1 h breaks 9.00 and 16.00 – Day 4 | Near continuous. | General light phase decrease. | General light phase decrease. | General light and dark phase decreases. |

| Dewasmes et al 2004 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 1.5 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | n.r. | Increase throughout dark phase. | Early and mid dark phase increases/late light phase increase. |

| Bonnet et al 1997 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | Early dark phase decrease and mid to late dark phase increases (n.r. light phase) | Early dark phase decrease, late dark phase increases (n.r. light phase) | Early dark phase decreases and mid dark phase increase. (n.r. light phase) |

| Vazquez-Palacious et al 2004 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights on. | Mid to late light phase increase/increase throughout dark phase. | Mid to late light phase increase/increase throughout dark phase. | Mid to late light phase increase/increase throughout dark phase. |

| Rampin 1991 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | Day 1 – 2 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | No change (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) | Increase throughout the remaining dark period. (n.r. light phase) |

| Rampin 1991 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | Day 2 – 2 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | Increase throughout remaining dark period (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) | Increase throughout the remaining dark period. (n.r. light phase) |

| Rampin 1991 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | Day 3 – 2 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | Increase throughout remaining dark period (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) |

| Rampin 1991 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | Day 4 – 2 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | No change (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) | No change. (n.r. light phase) |

| Gonzalez et al. 1995 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | General increase throughout dark (n.r. light) | General increase throughout dark (n.r. light) | General increase throughout dark (n.r. light) |

| Bouyer et al. 1998 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley (LR) | 1 h immobilisation | 5 h after light onset (14:10 light:dark) | decrease at late dark and following early/mid light phase | decrease early and late dark phase and in following mid light phase | increase early/mid dark phase |

| Bouyer et al. 1998 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley (HR) | 1 h immobilisation | 5 h after light onset (14:10 light:dark) | general increase throughout light phase and dark phase, but not following light | no change | general increase throughout light and dark phases, but not following light phase |

| Marinesco et al. 1999 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 0.5 h immobilistation | Beginning of lights off. | n.r. | increase during remaining dark phase (n.r. light phase) | increase during remaining dark phase (n.r. light phase) |

| Marinesco et al. 1999 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | n.r. | increase during remaining dark phase (n.r. light phase) | increase during remaining dark phase (n.r. light phase) |

| Marinesco et al. 1999 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 2 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | n.r. | no change (n.r. light phase) | increase during remaining dark phase (n.r. light phase) |

| Marinesco et al. 1999 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | OFA | 4 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | n.r. | no change (n.r. light phase) | no change. |

| Koehl et al. 2002 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights off. | Increase through dark phase/early light decrease. | Increase throughout dark phase/early light phase decrease. | Mid to late dark phase increase. |

| Koehl et al. 2002 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | 1 h immobilisation | Beginning of lights on. | Late light phase increase/early to mid dark phase increase. | Increase throughout light phase/early dark phase increase. | Late light phase increase/early to mid dark phase increase. |

| Tiba et al. 2003 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | Control handling - 1 h immobilisation | 1.5 h after light onset | Decrease mid light/Increase throughout dark. | Decrease mid light, increase late light/increase early dark. | Decrease mid light/increase early dark. |

| Tiba et al. 2003 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | Early handling as pups - 1 h immobilisation | 1.5 h after light onset | Decrease mid light/Increase throughout dark. | Decrease mid light, increase late light/Increase throughout dark. | Decrease mid light, increase late light/increase throughout dark. |

| Palma et al. 2000 | Immobilisation stress | Rat | Wistar | 1 h immobilisation | 2–2.5 h after light onset | Increase mid light (data for 6 h post-shock only). | Increase mid light (data for 6 h post-shock only). | Increase mid light (data for 6 h post-shock only). |

| MISC STRESS | ||||||||

| Bodosi et al. 2000 | Ether stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | 1 min exposure to ether vapor | 30–45 min before lights on. | n.r. | No change (n.r. dark phase) | Mid light phase increase (n.r. dark phase). |

| Bodosi et al. 2000 | Ether stress | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | 1 min exposure to ether vapor | 30–45 min before lights off. | n.r. | No change (n.r. light phase) | Early through late dark phase increase. (n.r. light phase). |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Cage change | Rat | F334 | Cage change | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | No change. | Late increase during light. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Cage change | Rat | Lewis | Cage change | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | No change. | Late increase during light/increase in middle of dark. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Cage change | Rat | Wistar | Cage change | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | Mid dark phase increase. | Late increase during light. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Cage change | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Cage change | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | No change. | Mid light phase decrease/mid dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Open field | Rat | F334 | Open field - 30 min | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | Late light phase increase. | Late light phase increase/early dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Open field | Rat | Lewis | Open field - 30 min | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | Mid light phase decrease, late light phase increase. | Late light phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Open field | Rat | Wistar | Open field - 30 min | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | Increase throughout dark. | Middle light phase decrease, late light phase increase/increase early to mid dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2005a | Open field | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Open field - 30 min | 2 h after lights on. | n.r. | Late light phase increase. | Increase late light phase/increase early to mid dark phase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | C57BL/6 | Open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on | n.r. | No change. | Late light phase increase/mid dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | BALB/c | Open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on | n.r. | No change. | Mid light-phase decrease, early dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | DBA/2 | Open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on | n.r. | Early light phase decrease/early to mid dark phase increase. | Mid light phase decrease/early to mid dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | F1 cross of C57/Balb | Open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on | n.r. | Early light phase decrease/early to mid dark phase increase. | Late might increase/early to mid dark phase increase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | C57BL/6 | Day after open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on 24-h prior to testing | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | BALB/c | Day after open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on 24-h prior to testing | n.r. | No change. | No change. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | DBA/2 | Day after open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on 24-h prior to testing | n.r. | Mid light phase decrease/early to mid dark phase increase. | Early light phase decrease/mid dark increase. |

| Tang et al. 2004 | Open field | Mouse | F1 cross of C57/Balb | Day after open field - 30 min | 2.5 h after lights on 24-h prior to testing | n.r. | Early dark phase increase. | No change. |

Immobilization Stress

A common procedure for inducing stress in rodents is immobilization (Table 1). Immobilization is considered primarily as a “psychological” stressor because there is no pain involved; it is the inability to escape that induces psychological stress. In the initial report (Rampin et al., 1991), 2 hr of immobilization at the beginning of the dark phase produced an increase in REM sleep. A subsequent study replicated this finding, with 1 hr of immobilization leading to increases in both slow-wave sleep [SWS] and REM sleep (Gonzalez et al., 1995). The increase in sleep was reduced, but not eliminated, by chemical lesions of the noradrenergic nucleus, the locus coeruleus [LC] (Gonzalez et al., 1995), indicating a role for the noradrenergic system in stress-induced increases in sleep.

The finding that immobilization stress increases sleep has been replicated a number of times (Table 1). Bonnet et al. (1997) also reported increases in both SWS and REM sleep for up to 8 hr after the termination of the stressor. However, this may simply represent recovery sleep, as the stressed animals did not sleep at all during the restraint while the controls slept during this period (Bonnet et al., 1997). This raises the inverse of the question first posed by Jouvet: are stress effects on sleep simply a result of sleep deprivation?

One study has examined the effect of restraint stress on the sleep of BALB and C57BL mice (Meerlo et al., 2001). BALB mice are more anxious and sleep less at baseline than C57BL mice (Tang et al., 2005). Following restraint stress, there was a decrease in REM sleep for 2–3 hr in both mouse strains, followed by an increase, which was greater in C57BL mice than in BALB mice. Interestingly, the increases in plasma corticosterone [CORT] levels for both strains in response to restraint stress were similar, while the increase in plasma prolactin level was greater in the C57BL strain.

Bouyer et al. (1998) classified rats as either High Responding [HR] or Low Responding [LR] based on their activity in a mildly stressful open field test. HR animals slept less and had less slow-wave sleep [SWS] than LR animals at baseline. REM sleep was increased for both groups after a 1-hr restraint session. HR animals showed a longer corticosterone recovery and increased REM sleep compared to baseline. LR animals, on the other hand, showed a decrease in sleep (Bouyer et al., 1998). These data indicate, as might be expected, that animals’ initial stress reactivity may influence how stress affects their sleep.

Marinesco et al. (1999) manipulated the length of time that rats were immobilized before having their sleep recorded. Animals immobilized for up to 2 hr showed the typical increase in SWS. However, a group restrained for 4 hr showed no subsequent SWS increase. These investigators made a strong case for involvement of the HPA axis in the absence of a sleep increase in the 4-hr group. First, adrenalectomized animals compared to controls showed a significantly larger increase of SWS after 1 hr of restraint. Second, animals that were exposed to the 4-hr immobilization had higher CORT levels than animals exposed to the 1-hr session. The more intense stress, associated with longer restraint and higher CORT levels, eliminated the sleep increase.

Bodosi et al. (2000) exposed rats to ether for 1 min. Their S/W in the first hour after exposure was not different from their S/W at the same clock time on any other day. Rats exposed to ether at the start of either the light or the dark period displayed increases in REM sleep throughout the remainder of the light or dark period, respectively. As there was no sleep loss induced by the brief stressful ether exposure itself, the REM sleep increase can be attributed to stress and not sleep deprivation in this paradigm. Bodosi et al. (2000) also demonstrated that there is an increase in the cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] level of prolactin following ether exposure. Such increases have also been observed following immobilization (Akema, 1995). Furthermore, Bodosi et al. (2000) showed that immunoneutralization of central prolactin prevented the ether-induced increase in REM sleep. However, immunoneutralization of central prolactin also decreased REM sleep in non-ether-exposed animals, and this complicates interpretations of the role of prolactin in ether-mediated increases in REM sleep.

Subsequent papers have teased apart different aspects of the immobilization stress/sleep relationship. Vazquez-Palacios and Velazquez-Moctezuma (2000) reported a typical increase in both SWS and REM sleep in the period after immobilization, while exposure to electric footshocks led to no increase in either REM sleep or SWS. Interestingly, footshock led to longer latencies to both SWS and REM sleep, while immobilization did not. Finally, a third group was injected with CORT to simulate the rise associated with stress. CORT injections had little effect on sleep, except for an increase in REM sleep latency similar to that produced by footshock. It was subsequently shown that the increases in SWS and REM sleep induced by immobilization are completely blocked by the opioid antagonist naltrexone. Naltrexone alone had no effect on sleep (Vazquez-Palacios et al., 2004). Further, naltrexone had no effect on the CORT response to stress, although it completely eliminated the sleep changes. These data suggest that the increases in sleep associated with relatively brief periods of restraint stress are mediated by endogenous opioid systems.

Other studies have focused on various parametric issues pertaining to restraint and sleep. Koehl et al. (2002) reported that 1 hr of immobilization at either light onset or offset led to an increase in REM sleep, always in the subsequent dark period. Tiba et al. (2003) demonstrated that rat pups exposed to early handling, which often reduces adult stress responses (see Champagne and Meaney, 2001, for a review), had sleep changes similar to those of controls after 1 hr of immobilization. This provides further support for the notion that brief restraint is not highly stressful to an animal. Dewasmes et al. (2004) reported that the increase in REM sleep after a 90-min immobilization was due to enormous increases in sequential REM sleep episodes (sREM). REM sleep in the rat can be bimodally divided into REM sleep periods that are separated by less than 3 min (sREM), and REM sleep periods separated by more than 3 min away from another REM sleep period (isolated, iREM)(Amici et al., 2005).

Finally, a recent paper from Papale et al. (2005) supports our contention that stress intensity influences subsequent sleep alterations. Rats were subjected to 22 hr of immobilization stress each day for 4 consecutive days. The subjects were allowed only two 1-hr periods each day to move about freely, eat and drink. Under this highly stressful condition, the animals showed large decreases in sleep efficiency (total sleep time/total recording time), SWS, and REM sleep. These changes persisted through the four days of recording. Thus, extremely long periods of immobilization were associated with decreases in REM sleep and SWS.

Shock Stress

Exposure to electric shock is another very common method for inducing stress in rodents (Table 1). Exposure to shock has typically been associated with a decrease in subsequent REM sleep (Kant et al., 1995; Palma et al., 2000; Vazquez-Palacios and Velazquez-Moctezuma, 2000). Kant and colleagues (1995) carried out a long-term study of the effects of chronic stress on physiology and behavior. Their animals lived for two weeks in operant chambers and were required to pull a chain to escape or avoid shock. There was also a yoked group that could not control shock termination, but was “yoked” to an escape animal. The procedure continued 24 hr/day for two weeks. Both stress groups showed a reduction in total sleep and REM sleep times during the first day. Further, the group that could control shock had reduced REM sleep on days 2 and 3. This appears contrary to the voluminous literature showing that controllable, compared to uncontrollable, stress in general has smaller physiological effects (reviewed in Peterson et al., 1993). It may be that the stress associated with the intense performance requirement (24 hr of responding) overwhelmed any positive effects of controllability. Alternatively, the decrease in sleep may be a primary response due to the necessity of maintaining a high level of wakefulness throughout a 24 hr period. A combination of the two is also possible.

Vazquez-Palacios and Velazquez-Moctezuma (2000) exposed rats to 5-min of intermittent, uncontrollable footshock. Sleep was recorded over the subsequent 24 hr. Both sleep latency (time to sleep onset) and REM sleep latency (time from sleep onset to the onset of the first REM sleep period) were increased, and REM sleep percent (REM sleep time as a percent of total sleep time) was significantly reduced for 9 hr in the shocked group. Our group has also previously reported that there is a REM sleep-selective suppression of sleep in the period immediately following a training session with light–shock pairings in rats (Sanford et al., 2001).

Palma et al. (2000) exposed animals to either 1 hr of immobilization or 1 hr of intermittent footshock. The two procedures produced mirror image sleep patterns. Restraint caused the typical increases in SWS and REM sleep. Intermittent shock led to decreases in total sleep time and total REM sleep time. Separate groups of animals were sacrificed immediately after the stress procedures. Although both groups compared to controls showed CORT elevations (approximately 20–25 μg/dl), no difference in CORT was evident between immobilized and shocked animals. However, shocked animals had significantly higher ACTH levels, indicating stronger HPA activation.

ACTH levels can differ due to the number of different compounds that elicit ACTH release (Romero & Sapolsky, 1996). Data from our laboratory indicated that 2 hr of immobilization leads to plasma CORT levels of approximately 10 μg/dl, while 2 hr of intermittent footshock produces levels of approximately 30 μg/dl (Brennan et al., 2006). Comparing the results of Palma et al. (2000) and Brennan et al. (2006) indicates that the CORT response to 1 hr of immobilization stress is greater than the response to 2 hr of immobilization.

Decreases in REM sleep also have been reported in the period immediately following passive avoidance learning (Mavanji et al., 2003). Sanford and colleagues (2003) have described the effects of electric shock presentation in several mouse strains. Within the first 24 hr following tone–shock pairings, REM sleep suppression was observed. Thus, it appears that across species the direct effect of shock exposure, unlike that of immobilization, is to suppress REM sleep for a number of hours. The difference is likely related to stressor intensity.

Fear-Conditioned Changes in Sleep

Although it is interesting that the stress of mild electric footshock transiently suppresses REM sleep, a viable animal model of the sleep changes after stress should also address the long-term changes that can persist for years after exposure to traumatic stress in humans. PTSD symptoms appear to be maintained at least in part by classical conditioning (see Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006, for a review). To that end, we have utilized a fear conditioning procedure to study the effect of cues associated with stress on sleep parameters. We have reported similar REM sleep reductions in rats with reexposure to either a cue associated with shock (Jha et al., 2005) or to situational reminders of the context in which shock had been administered in the absence of any explicit cues (Pawlyk et al., 2005). Situational reminders evoked a change in sleep architecture that resembled the immediate effects of footshock in rats (Sanford et al., 2001; Vazquez-Palacios et al., 2000).

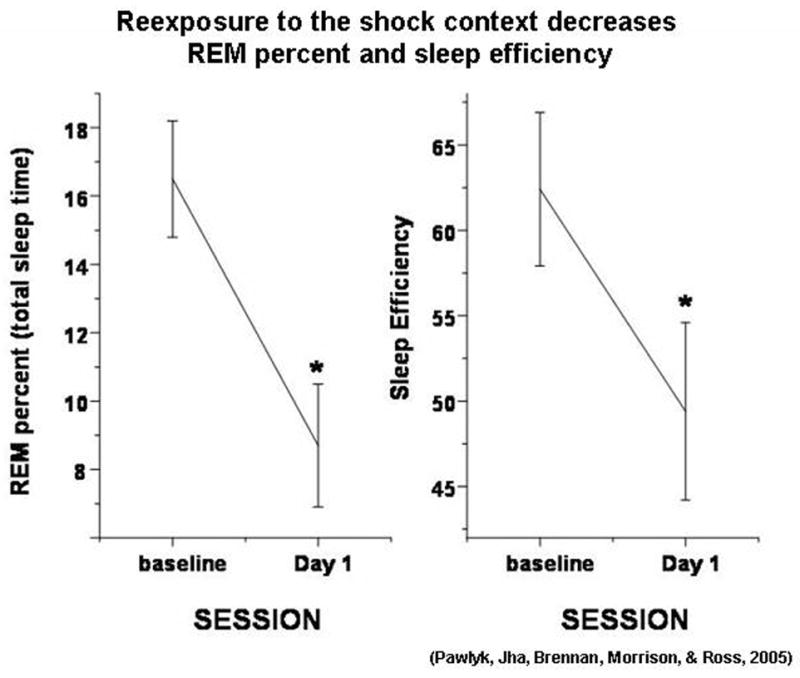

In our contextual fear conditioning study (Pawlyk et al., 2005) a group of rats was first habituated to the cable hookup over a number of days. On the training day, subjects were exposed to 5 mild electric footshocks (0.5 mA, 0.5 sec) every 3–6 min, over the course of 30 min in a different, training context. No shocks were given during the animal’s initial 3 min in the training chamber so that contextual conditioning could occur (see Lattal and Abel, 2001). Twenty-four hr later, rats were exposed to situational reminders (specific lighting intensity, previous day’s bedding). The data are presented in Figure 1. There were striking decreases in REM sleep percent, total time spent in REM sleep, and sleep efficiency. These were accompanied by corresponding increases in REM sleep latency and amount of wake time. We studied three of the seven shock-trained animals for a second day in the presence of situational reminders of the training context. This small number of rats also displayed REM sleep suppression. This suggests that the fearful memory is not extinguished during the first exposure to situational reminders of the training context.

Figure 1.

The effect of reexposure to the shock context 24 hr after conditioning on REM sleep percent (of total sleep time) and sleep efficiency (total sleep time/total recording time). N = 7. Data analyzed via a repeated measures ANOVA, * p < 0.05, different from baseline.

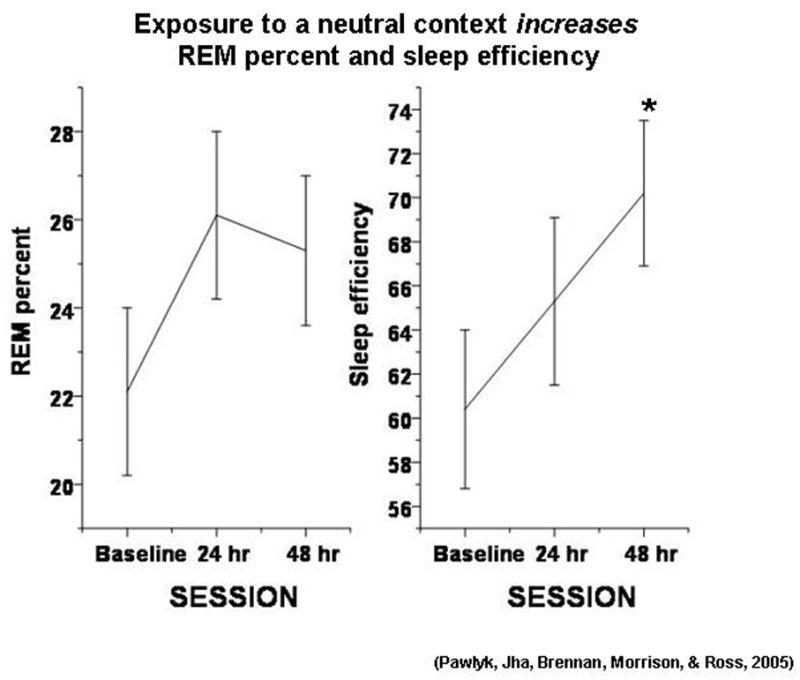

A separate group of animals was trained identically except that they were studied in a neutral context 24 hr after training. This control group was run to verify that the dramatic effects we had observed were due to fear conditioning and was not a residual effect of shock exposure. Somewhat surprisingly, as displayed in Figure 2, this group showed significant increases in sleep efficiency and time in REM sleep, and a decrease in wake, which led us to study the animals again 48 hr after training. On the second day following the training procedure, there was a non-selective increase in sleep. The increase in REM was roughly the same as that 24 hr post-training, but greater variability precluded significance.

Figure 2.

The effect of exposure to the neutral context 24 hr and 48 hr after conditioning on REM sleep percent (of total sleep time) and sleep efficiency (total sleep time/total recording time). N = 8. Data analyzed via a repeated measures ANOVA, * p < 0.05, different from baseline.

We postulated several possible explanations for the total sleep and REM sleep increases in the group studied in the neutral context. As described above, exposure to immobilization leads to a rebound in sleep in general and REM sleep in particular. It is possible that shock exposure led to a decrease in sleep immediately after training and that what we observed in the group studied in the neutral context was a sleep rebound. It is conceivable that exposure to the fearful context disrupted this rebound.

However, another possibility exists. Returning an animal to a chamber where it received footshocks the previous day induces freezing and other measures indicative of conditioned fear. Thus, the decrease in REM sleep and increase in wake that we have seen in such animals’ likely result from conditioned fear of the chamber. This stimulates an interesting interpretation of the animals studied in the neutral context, which showed large increases in REM sleep and total sleep. It is possible that the increases in REM sleep in animals returned to a neutral context reflect an inhibitory conditioning process. Moving an animal is presumably a powerful cue that elicits memories of the previous day’s shock session. When the animal is then placed in the neutral chamber, where shock was never received, a REM rebound results. We will describe this idea more fully in the description of our next study.

We conducted another experiment using a conditioned fear procedure with a discrete, as opposed to contextual, CS (Jha et al., 2005). So-called cued fear conditioning is mediated by neural systems different from those underlying contextual fear conditioning (Phillips & LeDoux, 1992). Subjects were habituated to the cable hookup over a period of days, and a baseline sleep recording was carried out. On the training day, subjects received five pairings of a tone CS and a co-terminating 1-sec footshock. A control group also experienced five tones and five shocks, but in an explicitly unpaired manner. Twenty four hr later all subjects were placed in a neutral environment and were presented with five tones. Strikingly, the fear-conditioned group showed a decrease in REM sleep percent from baseline, while the unpaired group showed an increase. These data are similar to the contextual fear conditioning data and raise analogous interpretative issues. The unpaired procedure may be producing inhibitory conditioning, in that the tones specifically predict a shock-free period. However, the fact that our other study (Pawlyk et al., 2005) demonstrated that recording in a neutral context also elevates REM sleep does not permit us to argue definitively that the tones were the cause of the REM sleep increase in the absence of other control groups. These data still support the notion that the decreases in sleep in both fear-conditioned groups, cued and contextual, result from conditioned fear, while the increases in sleep in the unpaired and neutral context groups, respectively, may result from inhibitory conditioning. Future studies to definitively determine whether inhibitory conditioning is relevant to the increased REM sleep in the group studied in the neutral context may be important for guiding behavioral therapy interventions.

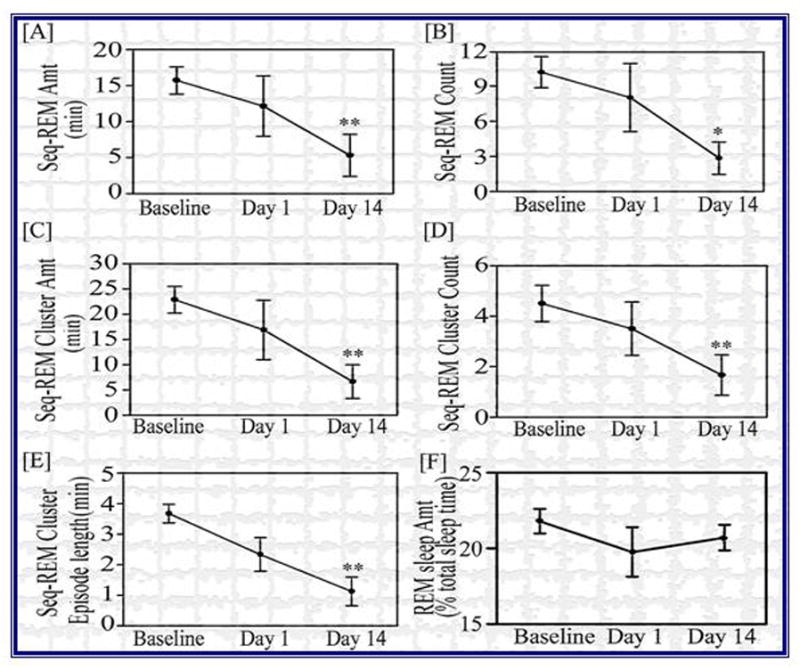

PTSD is a disorder that can persist for decades after the trauma(s) which initiate it (Roy-Byrne et al., 2004). To begin to model these long-term effects, we have in recent studies reexposed the animals to the fearful cues both 24 hr and 2 weeks after initial training (Madan et al., 2007). Figure 3 depicts sequential REM sleep data, as well as REM percent. Of particular note, even though there were no changes in REM sleep percent (bottom right) both sREM sleep and clusters of sREM sleep (which includes the NREM sleep periods in between the REM sleep periods) were reduced from baseline to Day 1, and significantly reduced on Day 14. Both the number of sREM sleep episodes and clusters were reduced, as well as the amount of both, and the average time of a cluster (Figure 3). The changes were larger on Day 14 than on Day 1, despite Day 1 being essentially an extinction session. These data appear to indicate that we have a model of the long-term changes in sleep characteristic of PTSD, which can be examined at longer intervals after initial insult.

Figure 3.

The effect of reexposure to the shock cues 24 hr and 14 days on: [A] sequential REM amount (min); [B] sequential REM count; [C] sequential REM cluster amount (min); [D] sequential REM cluster count; [E] sequential REM cluster episode length (min); [F] REM sleep amount (percent of total sleep time). N = 6. Data analyzed via a repeated measures ANOVA, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, different from baseline.

Sanford and colleagues (2003) have performed a number of experiments looking at reexposure to fear-inducing cues in mice (see Table 1). They found that reexposure to a tone previously paired with shock reduced REM sleep to a degree comparable to that seen after tone-shock pairings (Sanford et al., 2003). These data, in association with our findings in rats, point to the importance of conditioned factors in sleep changes and provide a possible mechanism for the changes in sleep that occur long after stressor termination. In the Conclusions, we discuss the potential relationship of long-term, conditioned changes in sleep in animals to PTSD symptoms in humans.

Neural and Pharmacological Mechanisms of S/W Changes

Elucidation of the neural and pharmacological mechanisms responsible for the observed changes in sleep following stress is clearly a way to develop treatments for the myriad sleep disorders that are influenced by stress. We will, therefore, attempt to synthesize information from studies of the neurobiology of the stress-sleep relationship.

The standard index of the stress response in animals is activation of the HPA axis, as indicated by plasma CORT level. CORT levels have been measured during stress procedures used to alter sleep, and the evidence indicates that for mild stressors CORT is not causally linked to the sleep changes. We make this statement in part because systemic injections of CORT intended to produce hormone levels associated with stress had little impact on sleep (Vazquez-Palacios & Velazquez-Moctezuma, 2000). Also, it has been shown that post-immobilization changes in REM sleep are completely eliminated by systemic injection of the opioid antagonist naltrexone (Vazquez-Palacios et al., 2004) and naltrexone had no effect on CORT changes, appearing to preclude HPA activation as a mechanism for the increase in REM seen after immobilization stress. It appears that the relatively mild stress associated with brief immobilization leads to opioid and noradrenergic activation, which then produces a rebound in REM post-stressor (Vazquez-Palacios et al., 2004). Several reports have also implicated stress-induced prolactin release as potentially mediating the effect of stress on sleep (e.g., Bodosi et al., 2000). We hope the current review will prompt research into the potential roles for these systems that have received less attention.

The picture changes significantly with more intense, and therefore perhaps more PTSD-relevant stressors. Exposure to longer immobilization or to footshock stress leads to the activation of a plethora of sleep-related neurotransmitter systems, including corticotrophin-releasing factor [CRF], dopamine, serotonin [5-HT], and norepinephrine (McEwen, 2004). CRF, apart from being the initial component of the peripheral HPA response, also functions centrally as a neurotransmitter (Owens & Nemeroff, 1991). CRF may be the key compound in mediating stress-induced changes in sleep (Opp, 1995). We have recently reported that a low dose (1 ng) of CRF infused bilaterally into the main output nucleus of the amygdala, the central nucleus, reduced REM sleep over the subsequent 4 hr (Pawlyk et al., 2006). Thus, the central effects of CRF may be as important as its role in HPA axis activation and the stimulation of CORT release.

Opp and colleagues have extensively studied the role of CRF in sleep changes (see Chang & Opp, 2001, for a review). Astressin, an antagonist at the CRF1 receptor, injected i.c.v. reduced the increase in wake, but not the decrease in REM sleep, induced by a period of restraint stress (Chang & Opp, 2002). Of interest for the following discussion, i.c.v. pretreatment with the CRF antagonist α-helical CRF blocked 5-HT-induced changes in temperature, but did not alter the effect of 5-HT on S/W in rats (Imeri et al., 2005). This suggests that 5-HT affects S/W systems independently of CRF, and leads us to a discussion of the role of 5-HT in stress-induced sleep changes.

5-HT is an excellent candidate for a neurotransmitter at least partially responsible for the REM sleep changes associated with stress. Beginning with the classic lesion work of Jouvet (reviewed in 1999), 5-HT has been accorded a prominent role in sleep. 5-HT neurons in the dorsal raphé nucleus [DRN] decrease their firing rate from wake through non-REM sleep into REM sleep, when they are basically silent (Ursin, 2002). The absence of 5-HT activity may allow cholinergic REM sleep generating cells to initiate REM sleep. Thus, overactive 5-HT systems should have an inhibitory effect on REM sleep. Our group has shown that infusions of the 5-HT1a agonist 8-OH DPAT into the pedunculopontine tegmental [PPT] region of cats reduced entrances into REM sleep; Sanford et al. (1994) proposed that postsynaptic 5-HT1a receptor mechanisms act to inhibit REM sleep.

Serotonergic systems are also known to be activated during stress (reviewed in Chaouloff et al., 1999). Rueter and Jacobs (1996) reported an increase in 5-HT release in the amygdala of rats (the precise region was unspecified) with a variety of behavioral/environmental manipulations, including tail pinch. Exposure to footshock stress in rats induced a 70% increase in 5-HT in the cortex (Dazzi et al., 2005). In another study in rats, 5-HT was elevated in the amygdala both after a conditioning session involving tone-shock presentations and after reexposure to the tone alone the following day (Yokoyama et al., 2005). Although Rueter and Jacobs (1996) suggested that there was little specificity to the 5-HT response to environmental perturbations, subsequent work has shown differences. Inescapable shock in rats produced large increases in 5-HT release in projection areas including the basolateral amygdala, while physically identical escapable shock did not (Amat et al., 1998). Studies measuring expression of immediate early genes such as c-fos indicate that exposure to tailshock (Takase et al., 2004), immobilization (de Medeiros et al., 2005), or even social defeat (Gardner et al., 2005) activate dorsal raphé neurons. On the basis of these data it is not surprising that exposure to stress, particularly intense stress, is associated with REM sleep disturbances (Akerstedt, 2006). This work suggests that activation of the DRN plays a key role in mediating 5-HT increases in target regions rather than pre-synaptic auto or heteroreceptor modulation.

Summary and Conclusions

Stress can modulate sleep, both directly as well as by contributing to the development of depressive and anxiety disorders. The development of animal models of stress-induced changes in sleep is critical to both fully understand the disorders, as well as to pre-clinically evaluate potential treatments. Of particular interest to our group has been the etiology of PTSD as a consequence of exposure to intense stress in humans (Brady & Sinha, 2005). Of all the chronic symptoms associated with PTSD, the changes in sleep may be the most debilitating. Thus, the primary purpose of this review has been to describe and assess potential animal models of stress-induced changes in sleep over the last 16 years since the seminal work of Rampin et al. (1991), with a particular emphasis on their potential application as models of the sleep disturbances of PTSD.

Immobilization is a frequently used stressor in rodents and was the first stressor applied in sleep studies. Relatively brief (<4 hr) periods of immobilization are associated with subsequent increases in sleep (e.g., Rampin et al., 1991). The changes in sleep associated with mild stressors appear to be associated with noradrenergic (Gonzalez et al., 1995) and endogenous opioid activation (Vazquez-Palacios et al., 2004), and not CORT. A longer, and presumably more stressful, 4-hr immobilization is associated with higher CORT levels, and no subsequent increase in SWS or REM sleep. Finally, 22 hr of immobilization is associated with a prominent decrease in all sleep parameters observed (Papale et al., 2005). Although the extended immobilization produced decreases in REM, it appears that overall immobilization stress is a poor model for PTSD.

Exposure to electric shock reliably reduces REM sleep (Kant et al., 1995; Palma et al., 2000; Vazquez-Palacios and Velazquez-Moctezuma, 2000), and thus seems like a more viable model of the sleep changes in PTSD than immobilization. Electric shock and other more intense stressors activate CRF and 5-HT neurotransmission, as well as other systems that are inhibitory to sleep in general and REM sleep in particular (McEwen, 2004). Further, we (Madan et al., 2007; Sanford et al., 2003) have demonstrated the powerful role of conditioned aversive stimuli in maintaining the sleep disturbance over several weeks. A conditioning model provides one mechanism whereby the effects of PTSD could persist for a long time after the initial trauma. In PTSD the sleep disruption is chronic, often persisting for decades after the trauma (Harvey et al., 2003). Conditioning, together with a deficit in extinction, has received a great deal of attention recently as a causal factor in PTSD (e.g., Quirk, 2006). Thus, we feel it is the shock paradigms that have the greatest potential for animal models relevant to the sleep disturbances of PTSD.

Understanding the neurobiology of the sleep changes induced by stress, as well as the changes induced by conditioned stimuli associated with stress, will enable us to better understand and treat the sleep problems associated with routine stress in humans as well as the development of depressive and anxiety disorders in humans. We believe that this review has summarized the current work in the field and highlights areas of needed preclinical future research. We believe the most needed area of research in this area is to elucidate further the pharmacological and neural substrates involved in mediating stress’ effects on sleep by applying a combination of pharmacological, lesion, and transgenic approaches to the behavioral paradigms that have been described. This will greatly enhance preclinical research in potential pharmacotherapeutics, and possibly enable a significant number of psychiatric patients to regain normal sleep patterns, and lead more normal lives.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adrien J, Dugovic C, Martin P. Sleep-wakefulness patterns in the helpless rat. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:257–262. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90041-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akema T, Chiba A, Oshida M, Kimura F, Toyoda J. Permissive role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the actue stress-induced prolactin release in female rats. Neurosci Lett. 1995;198:146–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerstedt T. Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat J, Matus-Amat P, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Escapable and inescapable stress differentially alter extracellular levels of 5-HT in the basolateral amygdala of the rat. Brain Res. 1998;812:113–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici R, Jones C, Perez E, Zamboni G. A physiological view of REM sleep structure. In: Parmeggiani PL, Velluti RA, editors. The physiologic nature of sleep. London: Imperial College Press; 2005. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bodosi B, Obal J, Gardi J, Komlodi J, Fang J, Krueger JM. An ether stressor increases REM sleep in rats: possible role of prolactin. Am J Physiol Reg, Int Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1590–R1598. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.5.R1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet C, Leger L, Baubet V, Debilly G, Cespuglio R. Influence of a 1 h immobilization stress on sleep states and corticotrophin-like intermediate lobe peptide (CLIP or ACTH18–39, Ph-ACTH18–39) brain contents in the rat. Brain Res. 1997;751:54–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer JJ, Vallee M, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Mayo W. Reaction of sleep-wakefulness cycle to stress is related to differences in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;804:114–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00670-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sinha R. Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobiological effects of chronic stress. Am J Psych. 2005;162:1483–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FX, Beck KD, Servatius RJ. Predator Odor Exposure Facilitates Acquisition of a Leverpress Avoidance Response in Rats. Neuropsych Dis Treat. 2006;2:65–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FX, Ottenweller JE, Seifu Y, Zhu G, Servatius RJ. Persistent stress-induced elevations of urinary corticosterone in rats. Physiol Behav. 2000;71:441–6. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff F, Berton O, Mormede P. Serotonin and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:28S–32S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Meaney MJ. Like mother, like daughter: evidence for non-genomic transmission of parental behavior and stress responsivity. Prog Brain Res. 2001;133:287–302. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)33022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FC, Opp MR. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) as a regulator of waking. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:445–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FC, Opp MR. Role of corticotrophin-releasing hormone in stressor-induced alterations of sleep in rat. Am J Physiol Reg, Int Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R400–R407. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00758.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day TA. Defining stress as a prelude to mapping its neurocircuitry: No help from allostasis. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psych. 2005;29:1195–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi L, Seu E, Cherchi G, Biggio G. Chronic administration of the SSRI fluvoxamine markedly and selectively reduces the sensitivity of cortical serotonergic neurons to footshock stress. Euro J Neuropsychopharm. 2005;15:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Medeiros MA, Reis LC, Mello LE. Stress-Induced c-Fos Expression is Differentially Modulated by Dexamethasone, Diazepam and Imipramine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1246–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewasmes G, Loos N, Delanaud S, Dewasmes D, Ramadan W. Pattern of rapid-eye movement sleep episode coccurrence after an immobilization stress in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]