Abstract

Trauma-hemorrhage leads to prolonged immune suppression, sepsis, and multiple organ failure. The condition affects all compartments of the immune system, and extensive studies have been carried out elucidating the immunological events following trauma-hemorrhage. The immune alteration observed following trauma-hemorrhage is gender dependent in both animal models and humans, though some studies in humans are contradictory. Within 30 min after trauma-hemorrhage, splenic and peritoneal macrophages, as well as T-cell function, are depressed in male animals, but not in proestrus females. Studies have also shown that the survival rate and the induction of subsequent sepsis following trauma-hemorrhage are significantly higher in males and ovariectomized females compared with proestrus females. These and other investigations show that sex hormones form the basis of this gender dichotomy, and administration of estrogen can ameliorate the immune depression and increase the survival rate after trauma-hemorrhage. This review specifically elaborates the studies carried out thus far demonstrating immunological alteration after trauma-hemorrhage and its modulation by estrogen. Also, estrogen was shown to produce its salutary effects through nuclear as well as extranuclear receptors. Estrogen rapidly activates several protein kinases and phosphatases, as well as the release of calcium in different cell types. The results of the studies exemplify the promise of estrogen as a therapeutic adjunct in treating adverse pathophysiological conditions following trauma-hemorrhage.

INTRODUCTION

The increased longevity of women (1) and their resilience to septic complications following injury are well described in the literature. The protection from complications and mortality associated with injury, trauma, and sepsis in females (2–5) is mostly attributed to the female sex hormone, estrogen (E2). On the contrary, women are more susceptible to several autoimmune diseases compared with men (6). It is suggested that increased propensity to inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis in women, is due to a more active immune system than in men—who are more prone to infections following injury (6). This is supported by observations such as the following: female mice produce more antibody and stronger T-cell response than males in response to immunizations (7,8); females mount stronger humoral immune responses to vaccines and reject allograft more rapidly than males (9,10); and there are significantly higher numbers of CD4+ T cells in females (11). Several studies demonstrate a naturally occurring sex difference in immune responses which persists after traumatic injury (4,12). Male sex and age are reported to be risk factors for development of sepsis and multiple organ failure after trauma (13–19). E2 plays a significant role in the sex dichotomy seen in response to injury or onset of autoimmune disease. In 1898, Calzolari observed an enlargement of the thymus when rabbits were castrated before sexual maturity, and documented a relationship between sexual environment and immunity (20). Exogenous E2 replacement in animals and humans promoted wound healing, and hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women was reported to prevent the development of chronic wounds (21–23). Also, E2 supplementation has been shown to reduce or reverse trauma-hemorrhagic shock–induced organ dysfunction in animal models (4,12).

ESTROGEN, MECHANISM OF ACTION

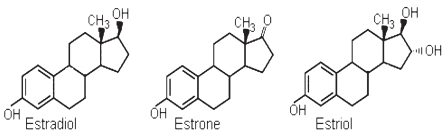

E2, the female hormone, is mainly produced by the ovaries and the placenta. The three major estrogens in women are estradiol, estriol, and estrone (Figure 1). Estrogens are synthesized from androgens by the loss of C-19 angular methyl group and the formation of an aromatic A ring. Whereas estradiol is derived from testosterone, estrone is derived from androstenedione. The main form of E2 in women before menopause is estradiol. E2 mainly mediates its action through its intracellular receptors, called E2 receptors (ER). ER-α and ER-β are the two major forms of ER, belonging to a large family of transcription factors, the nuclear receptor family, and are located mostly in the intracellular compartment. Several isoforms exist within each ER subtype and are present in almost all cells, though each cell may have a predominant subtype expression. E2 binding leads to activation and dimerization of ER followed by translocation into the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA segments of the estrogen-responsive genes. The metabolic and physiologic effects of E2 were previously known to be mediated by nuclear E2 receptors. Further, there is evidence indicating that mitochondria-localized ERs alter mitochondrial gene expression (24).

Figure 1.

Structure of estrogens: estradiol, estrone, and estriol.

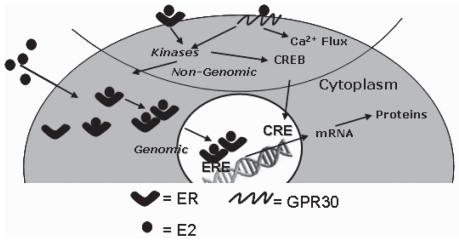

Apart from the genomic actions of E2, nongenomic actions (also termed extranuclear functions) are also described (25). A cell surface receptor, G-protein coupled receptor (GPR) 30, is described to have affinity to E2 (26–30) (Figure 2). Studies have shown that GPR30 over-expression in breast cancer cells deficient in ER-α and ER-β restores the activation of adenyl cyclase by E2. Additionally, silencing of GPR30 expression with small interfering RNA (siRNA) prevents E2-mediated cAMP-dependent signaling in keratinocytes and in SKBR3 breast cancer cells that lack ER-α and ER-β (29). The GPR30-mediated effect is distinct from the ER-mediated salutary effect of E2, and the former is also called a nongenomic effect (Figure 2). Nongenomic effects are usually measured as increase in phosphorylation of proteins, or increase in intracellular calcium (31). Compared with the conventional genomic effect, which constitutes intracellular binding of E2 to ER and gene activation, there is a more rapid (milliseconds to minutes) effect due to the nongenomic pathway which is initiated at the plasma membrane by E2 binding to GPR30 (28,30). Plasma membrane–associated ERs and their responsiveness to E2 have also been reported. They have been implicated in PI-3K/Akt activation and the rapid release of NO in endothelial cells (29,32). Therefore, the functional effect of estrogen is not necessarily mediated through processes that require gene transcription, but can also be immediate through its extranuclear effect by mobilizing key cytosolic enzymes (25,30).

Figure 2.

Genomic and nongenomic effects of estrogen. When estrogen (E2) binds estrogen receptors (ER) in the cytoplasm, they undergo homodimerization, translocation to the nucleus, and bind to estrogen responsive element (ERE) of genes and initiate specific gene transcriptions, acting like a transcription factor. Alternatively, the E2-bound GPR30 may initiate activation of protein kinases such as PKA, PKB, and PKC. This may be followed by the activation of intracellular E2-bound ER (30), other transcription factors such as cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB) or mobilization of intracellular calcium stores. The latter processes which are independent of ER, also known as nongenomic effect, facilitate a rapid response to stimuli. CREB binds to cAMP response element (CRE) to initiate transcription. A subset of ERs also associate with plasma membrane and interact with transmembrane growth factor receptors such as insulin-like growth factor receptor I, and epidermal growth factor receptor to induce nongenomic effects by protein–protein interactions (129). Recently it has been shown that PKA activation and Bcl-2 expression in the liver of E2-treated trauma-hemorrhage rats are initiated by E2 binding to GPR30 (130).

SEX DICHOTOMY IN TRAUMA OUTCOME

Multiple injuries and major hemorrhage induce marked dysregulation of the systemic immune response, end organ damage, and death (33–38). In patients with multiple injuries who are at risk for infectious complications, outcome is believed to be determined by the interrelationship of various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors after the trauma (36,39–47). Several studies have demonstrated that a profound deterioration of immune functions, characterized by a prolonged immune suppression, is initiated within the first hour of severe trauma or surgical procedures (14,17,42,48,49). The immunosuppression paves the way for secondary complications of sepsis and multiple organ failure. Following trauma-hemorrhagic shock, cardiovascular, hepatic, and immune functions are depressed in males as well as ovariectomized and aged females, but not in proestrus females, and remain depressed despite fluid resuscitation (17,50–54). However, administration of E2 was found to restore cardiovascular, hepatocellular, and immune functions following trauma-hemorrhage in male rodents (55,56).

In a study of 84 patients who sustained blunt injuries, a sex-specific regulation of leukocyte function was demonstrated in patients within the early posttraumatic period (39). In another study of 584 patients who underwent abdominal surgery, factors contributing to 30-day mortality in patients aged ≤50 years was found to differ between males and females (57). Studies show that more men died of myocardial infarction before reaching the hospital, though the 28-day mortality for men and women was the same (14,58). In a recent study of 5192 patients at a level I trauma center (59), Deitch et al. found that hormonally active women have a better physiologic response to similar degrees of shock and trauma than do their male counterparts. Though several clinical studies demonstrated the influence of sex in the outcome following trauma, several studies were unable to identify any such association (3,60–62). One of the reasons for contradictory or less convincing evidence for the influence of sex postinjury, and in sepsis in some studies in the human, may be heterogeneity of the population studied in relation to their hormonal status. The prevailing hormonal milieu at the time of injury, and not subsequently, appears to be of paramount importance, as this determines whether the patient will maintain immunocompetence and organ function or develop immunocompromise and organ dysfunction following injury. If such is the case, the lack of consideration of this parameter in clinical studies might contribute to confusing and unreliable results. However, a more pronounced and convincing sex-associated difference has been observed in animal studies under well-controlled conditions such as hormonal and nutritional status, preexisting conditions, and genetic homogeneity.

IMMUNE ALTERATIONS AFTER TRAUMA-HEMORRHAGE AND THE ROLE OF ESTROGENS

Both cardiovascular and immune functions are maintained in proestrus females following trauma-hemorrhage, but females in the other stages of the estrus cycle are not protected (17). In rodents, E2 levels are lowest during estrus and metestrus, gradually increasing during diestrus, and reaching a peak at proestrus stage (63). It has been demonstrated that female hormones, E2 and prolactin, modulate immune responsiveness in adult mice and that the proestrus state of the estrus cycle is characterized by a more vigorous immune response compared with the diestrus state (64–67). The observed restoration of organ function following trauma-hemorrhage after flutamide administration was also found to be estrogen-mediated, owing to increases in estrogen levels by increasing the conversion of testosterone to estrogen (68). Similarly, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) also has protective effects following trauma-hemorrhage, which are mediated through estrogen receptors (69). Several studies in animal models show that E2 administration is beneficial in males as well as females in maintaining organ function following trauma-hemorrhage.

Prolonged immune suppression, initiated shortly after injury, persists despite fluid resuscitation. This is characterized by a decrease in T- and B-cell function, depressed splenic dendritic cell function, depressed macrophage antigen presentation function, and altered cytokine release (4,17,70,71). In a recent study, significant decreases in splenic dendritic cell antigen presentation capacity, MHC class II expression, LPS-induced IL-12 production, and LPS- or IL-12–induced IFN-γ production were observed after trauma-hemorrhage (70). This immunological alteration could contribute to the host’s enhanced susceptibility to sepsis following trauma-hemorrhage. Although antigen presentation function is depressed in all populations of macrophages, including splenic and peritoneal, after trauma-hemorrhage, Kupffer cell proinflammatory cytokine production is increased. The cytokine release capacity of splenic and peritoneal macrophages is also decreased. These events are reversed by estrogen administration. In addition to immune perturbations, cardiac functions are significantly depressed in male mice and rats after trauma hemorrhage, whereas they are maintained on estrogen supplementation or in proestrus females. The mRNA and protein expression of both ER-α and ER-β were found to be decreased in cardiomyocytes after trauma-hemorrhage, and flutamide was found to normalize the ER expression (72). Extensive studies, as reviewed below, have been conducted to address the impact of trauma-hemorrhage on individual immune compartments and the effect of estrogen administration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Immunological alterations after trauma-hemorrhage and effect of estrogen in restoring the altered functions.

| Immune compartment | Function | Trauma-hemorrhage | Estrogen administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | KC production | ↑ | → |

| Tissue infiltration | ↑ | → | |

| Macrophages (PBMC, spleen, peritoneal cavity) | Antigen presentation | ↓ | → |

| IL-Iβ, IL-6, and TNF-α production | ↓ | → | |

| Dendritic cells (spleen) | Maturation | ↓ | → |

| Antigen presentation | ↓ | ||

| IL-6, and TNF-α production | ↓ | ||

| Kupffer cells | |||

| Antigen presentation | ↓ | → | |

| IL-6 and TNF-α production | ↑ | → | |

| T cells | |||

| T-cell proliferation | ↓ | → | |

| T-cell function | ↓ | → | |

| Apoptosis | ↑ | ND | |

↑ , enhanced/upregulated; ↓, decreased/downregulated; →, restored.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils play an important role in inflammation in the liver, small intestine, and lung in low-flow states (73,74). The proinflammatory milieu following trauma-hemorrhage recruits neutrophils into tissues, thereby increasing leukocyte trafficking and tissue permeability (75–77). Neutrophils can release superoxide anions and proteolytic enzymes, which diffuse across the endothelium and injure parenchymal cells. Alternatively, neutrophils can leave the microcirculation, and migrate and adhere to matrix proteins or other cells (78). After trauma-hemorrhagic shock, inflammatory products exit the gut via mesenteric lymph, prime neutrophils, and predispose to lung injury. It has been observed that plasma from male rats subjected to trauma-hemorrhage primes neutrophil respiratory burst, but plasma from proestrus females subjected to trauma-hemorrhage does not (79). Intraluminal nafamostat (serine protease inhibitor) reduced trauma-hemorrhage–induced gut and lung injury as well as neutrophil-activating ability, demonstrating that neutrophil-derived serine proteases play an important role in trauma-hemorrhage–induced gut and lung injury (80). Ischemic gut is a major source of factors that lead to neutrophil activation (81). A striking sexual dimorphism in neutrophil activation was also observed after trauma-hemorrhage, as estrogen limited trauma-induced neutrophil activation whereas testosterone potentiated it (82). It has also been shown that keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), a chemoattractant for neutrophils, is up-regulated after trauma-hemorrhage, and KC was found to play a critical role in the induction of systemic inflammation and tissue damage after trauma-hemorrhage (83). This was further substantiated by studies which showed that administration of the anti-KC antibody before trauma-hemorrhage prevented increases in KC plasma levels, which was accompanied by amelioration of neutrophil infiltration and edema formation in lung and liver after trauma-hemorrhage (83). E2 prevents end organ infiltration of neutrophils, and this is possibly mediated through the demonstrated inhibitory effect of E2 on KC (84). Further, mice with functional TLR4 expression showed elevated lung neutrophil infiltration following trauma-hemorrhage, which was not observed in TLR4 mutant mice, suggesting the role of neutrophils in mediating the inflammatory response following trauma-hemorrhage (85). It was also found that E2 administration after trauma-hemorrhage reduces tissue neutrophil sequestration in male rodents, and the salutary effects of E2 administration on tissue neutrophil sequestration following the trauma are receptor subtype- and tissue-specific (74).

Macrophages and Dendritic Cells

The depression of immune response normally observed in male animals following trauma-hemorrhage can also be prevented by precastration or administration of flutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist (86–88). In addition, the administration of 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) to female mice depressed the splenic and peritoneal macrophage immune response after trauma-hemorrhage to levels comparable to those seen in males under such conditions (89,90). Similarly, a significant decrease in the release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 by splenic macrophages and peritoneal macrophages was observed in DHT-treated castrated male mice following trauma-hemorrhage (91). MHC class II expression was also shown to be decreased in peritoneal and splenic macrophages after trauma-hemorrhage (92). Estrogens have been shown to increase the resistance of host animals to infections and also stimulate macrophage functions, suggesting that female sex steroids should improve macrophage function in contrast to the immunodepressive effects of male sex steroids (93–95). The administration of ER-α agonist propyl pyrazole triol (PPT), but not ER-β agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN), following trauma-hemorrhage was as effective as E2 in preventing the suppression in splenic macrophage cytokine production (96). Therefore, it appears that ER-α plays the predominant role in mediating the salutary effects of E2 on splenic macrophage cytokine production following trauma-hemorrhage and that such effects are likely mediated via normalization of MAPK, but not NF-κB signaling pathways (96). When trauma-hemorrhage animals were treated with a cell-impermeable E2 conjugated with BSA (E2-BSA) to study the effect on splenic macrophages, E2-BSA was found to be equally effective as E2, demonstrating nongenomic effects of E2 (97) (Figure 2).

Dendritic cells are known to be professional antigen-presenting cells. When the role of dendritic cells in depressed immune function after trauma-hemorrhage was investigated, it was observed that splenic dendritic cell antigen presentation capacity, MHC class II expression, and cytokine production (IL-12 and IFN-γ) were significantly decreased following trauma-hemorrhage (70). This depression in antigen presentation could contribute to the host’s enhanced susceptibility to sepsis following trauma-hemorrhage (70). However, E2 as well as PPT prevented the depression in splenic dendritic cells, but not DPN, ER-β agonist, following trauma-hemorrhage (98). As observed for macrophages, the salutary effects of E2 on splenic dendritic cell functions are therefore mediated predominantly via ER-α (98).

Kupffer Cells

Kupffer cells, the largest population of tissue-fixed macrophages in the body, located in the liver sinusoids, produce increased amounts of IL-6, IL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) when exposed to and activated by pathogens, and contribute significantly to the systemic levels of these cytokines (99–101). Incidentally, studies in rodents have demonstrated that severe hypoxia, in the absence of blood loss or tissue trauma, produces a profound systemic inflammatory response and severe immunodepression, similar to that observed after trauma-hemorrhage—a condition associated with regional tissue hypoxia (99,100). It was observed that following trauma-hemorrhage there is a marked stimulation of IL-6 and TNF-α production by Kupffer cells (102). IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, peaked at 2 h after the insult. Kupffer cell depletion before trauma-hemorrhage reduced plasma IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels, whereas treatment with anti–IL-10 after trauma-hemorrhage increased IL-6 and TNF-α levels (102–104). Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) is a potential mechanism for release of these inflammatory factors. In a murine model of hypoxia, it was found that hypoxia increases Kupffer cell IL-6 production by p38 MAPK activation via Src-dependent pathway (105,106). Src kinases are a family of nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) that are expressed either ubiquitously or predominantly in specific immune competent cells. Animals treated with progesterone showed significantly reduced levels of the TNF-α, IL-6, and transaminases, as well as reduced myeloperoxidase activity in the liver. Further, in vitro treatment of Kupffer cells with progesterone decreased TNF-α synthesis (107). In a recent study, it was found that Kupffer cell TLR4, iNOS, IL-6, and TNF-α production capacities were increased; and ATP, Tfam, and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI) levels were decreased following trauma-hemorrhage, whereas E2 administration normalized these levels (108). Furthermore, the decreased Kupffer cell ATP and mtCOI levels were not observed in TLR4 mutant mice following trauma-hemorrhage, suggesting that downregulation of TLR4-dependent ATP production is critical to E2-mediated immunoprotection in Kupffer cells following trauma-hemorrhage (108). Activation of TLR4 initiates an inflammatory cascade involving activation of p38 MAPK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and NF-κB, leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines (109–111). Administration of E2 following trauma-hemorrhage in wild-type mice decreased Kupffer cell TLR4 expression, as well as prevented the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and NF-κB, suggesting that the protective effect of estradiol on Kupffer cell function is mediated via downregulation of TLR4-dependent p38 MAPK and NF-κB signaling following trauma-hemorrhage—which prevents the systemic release of cytokines (109,110). Upon activation of TLR, MyD88, an adaptor protein that is shared by all TLR pathways, is recruited to TLR receptor domains and links TLR with the downstream intracellular signaling cascades (112,113). Hypoxia increased Kupffer cell TLR-4 expression in both males and proestrus females (114). However, expression of MyD88 and Src was down-regulated in Kupffer cells from proestrus females, whereas Src expression and phosphorylation were increased in Kupffer cells from males after hypoxia. So MyD88 likely plays the central role in IL-6 release in Kupffer cells from proestrus females, whereas Src is responsible for the production of IL-6 by Kupffer cells from males following hypoxia (114). A regulatory role of E2 on Kupffer cells is further confirmed by the presence of high-affinity E2 receptors on Kupffer cells and their significantly decreased expression after ovariectomy (115).

T Cells

Severe impairment in the functions of immune-competent cells has been observed following trauma and hemorrhage (4,116,117). The cytokines and chemokines released during trauma and hemorrhagic shock disrupt T-lymphocyte functions, and immune responses are suppressed in males, but not in proestrus females, after trauma-hemorrhage. When male C3H/HeN mice were castrated 2 weeks before the induction of soft-tissue trauma, splenocyte proliferation, splenocyte interleukin IL-2 and IL-3 release were significantly depressed in sham-castrated animals following trauma-hemorrhage, but not in precastrated males (118). Both androgen and estrogen receptors are present in T cells (119). Androgens, in particular, have been found to depress the release of the Th1 cytokine IL-2 by splenocytes following trauma-hemorrhage (87,89). In male animals, the enhanced release of the anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokine, IL-10, following trauma-hemorrhage also contributes to the depressed immune response under such conditions. Increased thymocyte apoptosis was also evident in males but not in proestrus females following trauma-hemorrhage (120). Angele et al. (121) demonstrated that male and female sex steroids differentially affect the release of Th1 and Th2 cytokines following trauma-hemorrhage. They observed a significant depression of splenocyte Th1 cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ) in DHT-treated castrated animals, DHT-treated females, and untreated males following trauma-hemorrhage, as opposed to maintained Th1 cytokine release in E2-treated males and females (121). The release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was markedly increased in DHT-treated mice and males subjected to trauma-hemorrhage compared with shams, but decreased in E2-treated mice and females, suggesting that male and female sex steroids differentially affect the release of Th1 and Th2 cytokines following trauma-hemorrhage (121).

Splenic T lymphocytes not only possess receptors for E2 but also contain enzymes involved in E2 metabolism. Analysis for aromatase and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases indicated increased E2 synthesis and low conversion into estrone in T lymphocytes of proestrus but not of ovariectomized mice (122). It is suggested that the immunoprotection of proestrus females is associated with enhanced reductase function of the enzyme, whereas in males, decreased expression of oxidative isomer type IV, which impairs catabolism of DHT, probably augments immunosuppression (122). When T cells were stimulated in vitro in the presence of DHEA and a variety of hormone antagonists, the stimulatory effect of DHEA on splenocyte proliferation was unaltered by the testosterone receptor antagonist flutamide, whereas the E2 antagonist tamoxifen completely abrogated its effect (123). In addition, DHEA administration normalized the elevated serum corticosterone level typically seen following injury, indicating that DHEA improves splenocyte function after trauma-hemorrhage by directly stimulating T cells, and also by preventing a rise in serum corticosterone (123). The activity of 26s proteasome from CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ splenic T lymphocytes was enhanced following trauma-hemorrhage, which was associated with increased expression of NF-κB and STAT1 (124). PPT, but not DPN, administration following trauma-hemorrhage was as effective as E2 in preventing T-cell suppression (87,125). So it appears that ER-α plays a predominant role in mediating the salutary effects of 17β-estradiol on T cells following trauma-hemorrhage, and that such effects are likely mediated via normalization of MAPK, NF-κB, and AP-1 signaling pathways (125).

Alterations in B-cell repertoire have also been studied following hemorrhage. When no changes in the total number of splenocytes or of splenic B cells were found after hemorrhage, decreases of >40% in the total number of Ig-producing cells—as well as in the numbers of B cells secreting IgM, IgA, and IgG2b—were found during the period of 2 to 96 h posthemorrhage (126).

According to Abraham and colleagues (127,128), hemorrhage produces marked alterations in pulmonary and intestinal B cell repertoires, which are suggested to contribute to postinjury abnormalities in host defenses.

CONCLUSION

Animal models clearly demonstrate a sex-dependent immune response following trauma-hemorrhage. Some of the contradicting reports in humans might be due to unknown hormonal status, preexisting disease conditions, varying nutritional status, and genetic heterogeneity of the patients. There is marked immune suppression within the first hour following trauma-hemorrhage in experimental animals, and the prolonged immune suppression leads to sepsis and multiorgan failure. As discussed above, specific immunological components such as antigen-presenting cells, T cells, and Kupffer cells are significantly affected by trauma-hemorrhage. The sex hormones, androgens, and estrogens play a major role in the immune alteration seen in the animal model, and the adverse effects can be largely restored by E2 administration. Estrogen, therefore, appears to be a useful therapeutic adjunct for the treatment of trauma-hemorrhage complications, and consequently for preventing the subsequent septic complications and mortality rates under those conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a USPHS grant NIH GM 37127.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Shrestha LB. Life Expectancy in the United States. 2005. CRS Report RL32792, US Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitcher JM, Wang M, Tsai BM, Kher A, Turrentine MW, Brown JW, Meldrum DR. Preconditioning: gender effects. J Surg Res. 2005;129:202–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberholzer A, Keel M, Zellweger R, Steckholzer U, Trentz O, Ertel W. Incidence of septic complications and multiple organ failure in severely injured patients is sex specific. J Trauma. 2000;48:932–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Hubbard WJ, Kerby JD, Rue LW, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Gender differences in acute response to trauma-hemorrhage. Shock. 2005;24 (Suppl 1):101–6. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000191341.31530.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caruso JM, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Dayal SD, Deitch EA. The female gender protects against pulmonary injury after trauma hemorrhagic shock. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2001;2:231–40. doi: 10.1089/109629601317202713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ansar AS, Penhale WJ, Talal N. Sex hormones, immune responses, and autoimmune diseases: mechanisms of sex hormone action. Am J Pathol. 1985;121:531–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein Y, Ran S, Segal S. Sex-associated differences in the regulation of immune responses controlled by the MHC of the mouse. J Immunol. 1984;132:656–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eidinger D, Garrett TJ. Studies of the regulatory effects of the sex hormones on antibody formation and stem cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1972;136:1098–116. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.5.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karpuzoglu-Sahin E, Zhi-Jun Y, Lengi A, Sriranganathan N, Ansar AS. Effects of long-term estrogen treatment on IFN-gamma, IL-2 and IL-4 gene expression and protein synthesis in spleen and thymus of normal C57BL/6 mice. Cytokine. 2001;14:208–17. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graff RJ, Lappe MA, Snell GD. The influence of the gonads and adrenal glands on the immune response to skin grafts. Transplantation. 1969;7:105–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amadori A, et al. Genetic control of the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio in humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:1279–83. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacs EJ, Messingham KA, Gregory MS. Estrogen regulation of immune responses after injury. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;193:129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong LB, Lekawa M, Navarro RA, McGrath J, Cohen M, Margulies DR, Hiatt JR. Pedestrian-motor vehicle trauma: an analysis of injury profiles by age. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kher A, et al. Sex differences in the myocardial inflammatory response to acute injury. Shock. 2005;23:1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000148055.12387.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bone RC. Toward an epidemiology and natural history of SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) JAMA. 1992;268:3452–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGowan JE, Jr, Barnes MW, Finland M. Bacteremia at Boston City Hospital: occurrence and mortality during 12 selected years (1935–1972), with special reference to hospital-acquired cases. J Infect Dis. 1975;132:316–35. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angele MK, Schwacha MG, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Effect of gender and sex hormones on immune responses following shock. Shock. 2000;14:81–90. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frink M, Pape HC, van Griensven M, Krettek C, Chaudry IH, Hildebrand F. Influence of sex and age on MODS and cytokines after multiple injuries. Shock. 2007;27:151–6. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239767.64786.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuzzocrea S, et al. The protective role of endogenous estrogens in carrageenan-induced lung injury in the rat. Mol Med. 2001;7:478–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calzolari A. Recherches experimentales sur un rapport probable entre la fonction du thymus et celle des testicules. Arch Ital Biol. 1898;30:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pirila E, et al. Wound healing in ovariectomized rats: effects of chemically modified tetracycline (CMT-8) and estrogen on matrix metalloproteinases-8, -13 and type I collagen expression. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:281–94. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashcroft GS, Greenwell-Wild T, Horan MA, Wahl SM, Ferguson MW. Topical estrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing in aged humans associated with an altered inflammatory response. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis DJ, Knauss J, Bilker W. Hormone replacement therapy and prevention of pressure ulcers and venous leg ulcers. Lancet. 2002;359:675–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JQ, Delannoy M, Cooke C, Yager JD. Mitochondrial localization of ERalpha and ER-beta in human MCF7 cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E1011–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00508.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:726–41. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–32. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob J, et al. Membrane estrogen receptors: genomic actions and post transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW. Membrane- initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:1–19. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Nongenomic effects of estrogen: why all the uncertainty? Steroids. 2006;71:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriarty K, Kim KH, Bender JR. Minireview: estrogen receptor-mediated rapid signaling. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5557–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuckerbraun BS, McCloskey CA, Gallo D, Liu F, Ifedigbo E, Otterbein LE, Billiar TR. Carbon monoxide prevents multiple organ injury in a model of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Shock. 2005;23:527–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purcell EM, Dolan SM, Kriynovich S, Mannick JA, Lederer JA. Burn injury induces an early activation response by lymph node CD4+ T cells. Shock. 2006;25:135–40. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000190824.51653.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shukla A, Hashiguchi N, Chen Y, Coimbra R, Hoyt DB, Junger WG. Osmotic regulation of cell function and possible clinical applications. Shock. 2004;21:391–400. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shelley O, Murphy T, Paterson H, Mannick JA, Lederer JA. Interaction between the innate and adaptive immune systems is required to survive sepsis and control inflammation after injury. Shock. 2003;20:123–9. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000079426.52617.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porta F, et al. Effects of prolonged endotoxemia on liver, skeletal muscle and kidney mitochondrial function. Crit Care. 2006;10:R118. doi: 10.1186/cc5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harbrecht BG, Doyle HR, Clancy KD, Townsend RN, Billiar TR, Peitzman AB. The impact of liver dysfunction on outcome in patients with multiple injuries. Am Surg. 2001;67:122–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majetschak M, Christensen B, Obertacke U, Waydhas C, Schindler AE, Nast-Kolb D, Schade FU. Sex differences in posttraumatic cytokine release of endotoxin-stimulated whole blood: relationship to the development of severe sepsis. J Trauma. 2000;48:832–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1355–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He W, Fong Y, Marano MA, Gershenwald JE, Yurt RW, Moldawer LL, Lowry SF. Tolerance to endotoxin prevents mortality in infected thermal injury: association with attenuated cytokine responses. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:859–64. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobbe P, Vodovotz Y, Kaczorowski D, Mollen KP, Billiar TR, Pape HC. Patterns of cytokine release and evolution of remote organ dysfunction after bilateral femur fracture. Shock. 2007 Nov 8; doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815d190b. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotani J, Avallone NJ, Lin E, Goshima M, Lowry SF, Calvano SE. Tumor necrosis factor receptor regulation of bone marrow cell apoptosis during endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation. Shock. 2006;25:464–71. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209544.22048.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor, other cytokines and disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:317–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, Wang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 rediscovered as a cytokine. Shock. 2001;15:247–53. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang R, et al. Anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody ameliorates gut barrier dysfunction and improves survival after hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med. 2006;12:105–14. doi: 10.2119/2006-00010.Yang. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter JJ, Whelan RL. The immunologic consequences of laparoscopy in oncology. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10:655–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ordemann J, Jacobi CA, Schwenk W, Stosslein R, Muller JM. Cellular and humoral inflammatory response after laparoscopic and conventional colorectal resections. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:600–8. doi: 10.1007/s004640090032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang P, Ayala A, Dean RE, Hauptman JG, Ba ZF, DeJong GK, Chaudry IH. Adequate crystalloid resuscitation restores but fails to maintain the active hepatocellular function following hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 1991;31:601–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang P, Chaudry IH. Crystalloid resuscitation restores but does not maintain cardiac output following severe hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 1991;50:163–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90241-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaudry IH, Ayala A, Ertel W, Stephan RN. Hemorrhage and resuscitation: immunological aspects. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R663–78. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.4.R663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ayala A, Ertel W, Chaudry IH. Trauma-induced suppression of antigen presentation and expression of major histocompatibility class II antigen complex in leukocytes. Shock. 1996;5:79–90. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ananthakrishnan P, Cohen DB, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Deitch EA. Sex hormones modulate distant organ injury in both a trauma/hemorrhagic shock model and a burn model. Surgery. 2005;137:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizushima Y, Wang P, Jarrar D, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Estradiol administration after trauma-hemorrhage improves cardiovascular and hepatocellular functions in male animals. Ann Surg. 2000;232:673–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokoyama Y, Schwacha MG, Samy TS, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Gender dimorphism in immune responses following trauma and hemorrhage. Immunol Res. 2002;26:63–76. doi: 10.1385/ir:26:1-3:063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harten J, McCreath BJ, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Kinsella J. The effect of gender on postoperative mortality after emergency abdominal surgery. Gend Med. 2005;2:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(05)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sonke GS, Beaglehole R, Stewart AW, Jackson R, Stewart FM. Sex differences in case fatality before and after admission to hospital after acute cardiac events: analysis of community based coronary heart disease register. BMJ. 1996;313:853–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7061.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deitch EA, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Monaghan SF, Bongu A, Machiedo GW. Hormonally active women tolerate shock-trauma better than do men: a prospective study of over 4000 trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:447–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318148566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.George RL, McGwin G, Jr, Metzger J, Chaudry IH, Rue LW., III The association between gender and mortality among trauma patients as modified by age. J Trauma. 2003;54:464–71. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000051939.95039.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Napolitano LM, Greco ME, Rodriguez A, Kufera JA, West RS, Scalea TM. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:274–80. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200102000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.George RL, McGwin G, Jr, Windham ST, Melton SM, Metzger J, Chaudry IH, Rue LW., III Age-related gender differential in outcome after blunt or penetrating trauma. Shock. 2003;19:28–32. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshinaga K, Hawkins RA, Stocker JF. Estrogen secretion by the rat ovary in vivo during the estrous cycle and pregnancy. Endocrinology. 1969;85:103–12. doi: 10.1210/endo-85-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krzych U, Strausser HR, Bressler JP, Goldstein AL. Quantitative differences in immune responses during the various stages of the estrous cycle in female BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1978;121:1603–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krzych U, Strausser HR, Bressler JP, Goldstein AL. Effects of sex hormones on some T and B cell functions, evidenced by differential immune expression between male and female mice and cyclic pattern of immune responsiveness during the estrous cycle in female mice. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1981;1:73–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1981.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Angele MK, Frantz MC, Chaudry IH. Gender and sex hormones influence the response to trauma and sepsis: potential therapeutic approaches. Clinics. 2006;61:479–88. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322006000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokoyama Y, Kitchens WC, Toth B, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Upregulation of hepatic prolactin receptor gene expression by 17beta-estradiol following trauma-hemorrhage. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2530–6. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00681.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsieh YC, Yang S, Choudhry MA, Yu HP, Bland KI, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. Flutamide restores cardiac function after trauma-hemorrhage via an estrogen-dependent pathway through up-regulation of PGC-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H416–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00865.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimizu T, Szalay L, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Rue LW, III, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Mechanism of salutary effects of androstenediol on hepatic function after trauma-hemorrhage: role of endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G244–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00387.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawasaki T, et al. Trauma-hemorrhage induces depressed splenic dendritic cell functions in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:4514–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abraham E. T- and B-cell function and their roles in resistance to infection. New Horiz. 1993;1:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu HP, Yang S, Choudhry MA, Hsieh YC, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Mechanism responsible for the salutary effects of flutamide on cardiac performance after trauma-hemorrhagic shock: upregulation of cardiomyocyte estrogen receptors. Surgery. 2005;138:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu DZ, Lu Q, Adams CA, Issekutz AC, Deitch EA. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced up-regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules is blunted by mesenteric lymph duct ligation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:760–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114815.88622.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu HP, Shimizu T, Hsieh YC, Suzuki T, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. Tissue-specific expression of estrogen receptors and their role in the regulation of neutrophil infiltration in various organs following trauma-hemorrhage. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:963–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abraham E. Alterations in cell signaling in sepsis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41 (Suppl 7):S459–64. doi: 10.1086/431997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vaday GG, et al. Combinatorial signals by inflammatory cytokines and chemokines mediate leukocyte interactions with extracellular matrix. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abraham E, et al. Peripheral blood neutrophil activation patterns are associated with pulmonary inflammatory responses to lipopolysaccharide in humans. J Immunol. 2006;176:7753–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olanders K, et al. The effect of intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury on ICAM-1 expression, endothelial barrier function, neutrophil tissue influx, and protease inhibitor levels in rats. Shock. 2002;18:86–92. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adams JM, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the activation of neutrophils by shock mesenteric lymph. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2003;4:37–44. doi: 10.1089/109629603764655263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deitch EA, Shi HP, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Xu DZ. Serine proteases are involved in the pathogenesis of trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced gut and lung injury. Shock. 2003;19:452–6. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000048899.46342.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deitch EA, Shi HP, Feketeova E, Hauser CJ, Xu DZ. Hypertonic saline resuscitation limits neutrophil activation after trauma-hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2003;19:328–33. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deitch EA, Ananthakrishnan P, Cohen DB, Xu DZ, Feketeova E, Hauser CJ. Neutrophil activation is modulated by sex hormones after trauma-hemorrhagic shock and burn injuries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1456–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frink M, Hsieh YC, Hsieh CH, Pape HC, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. Keratinocyte-derived chemokine plays a critical role in the induction of systemic inflammation and tissue damage after trauma-hemorrhage. Shock. 2007;28:576–81. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31814b8e0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Frink M, Thobe BM, Hsieh YC, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. 17beta-Estradiol inhibits keratinocyte-derived chemokine production following trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L585–91. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00364.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frink M, Hsieh YC, Thobe BM, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. TLR4 regulates Kupffer cell chemokine production, systemic inflammation and lung neutrophil infiltration following trauma-hemorrhage. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2625–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Angele MK, Wichmann MW, Ayala A, Cioffi WG, Chaudry IH. Testosterone receptor blockade after hemorrhage in males: restoration of the depressed immune functions and improved survival following subsequent sepsis. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1207–14. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430350057010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wichmann MW, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Male sex steroids are responsible for depressing macrophage immune function after trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1335–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wichmann MW, Angele MK, Ayala A, Cioffi WG, Chaudry IH. Flutamide: a novel agent for restoring the depressed cell-mediated immunity following soft-tissue trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 1997;8:242–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Angele MK, Ayala A, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Testosterone: the culprit for producing splenocyte immune depression after trauma hemorrhage. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1530–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Angele MK, Ayala A, Monfils BA, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Testosterone and/or low estradiol: normally required but harmful immunologically for males after trauma-hemorrhage. J Trauma. 1998;44:78–85. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Angele MK, Knoferl MW, Schwacha MG, Ayala A, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Sex steroids regulate pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages after trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C35–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mayr S, et al. Castration prevents suppression of MHC class II (Ia) expression on macrophages after trauma-hemorrhage. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:448–53. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Friedman D, Netti F, Schreiber AD. Effect of estradiol and steroid analogues on the clearance of immunoglobulin G-coated erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:162–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI111669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nicol T, Bilbey DL, Charles LM, Cordingley JL, Vernon-Roberts B. Oestrogen: the natural stimulant of body defence. J Endocrinol. 1964;30:277–91. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0300277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamamoto Y, Saito H, Setogawa T, Tomioka H. Sex differences in host resistance to Mycobacterium marinum infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4089–96. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4089-4096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suzuki T, Shimizu T, Yu HP, Hsieh YC, Choudhry MA, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Estrogen receptor-alpha predominantly mediates the salutary effects of 17beta-estradiol on splenic macrophages following trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C978–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00092.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suzuki T, Yu HP, Hsieh YC, Choudhry MA, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Estrogen-mediated activation of non-genomic pathway improves macrophages cytokine production following trauma-hemorrhage. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:662–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kawasaki T, Choudhry MA, Suzuki T, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. 17beta-Estradiol’s salutary effects on splenic dendritic cell functions following trauma-hemorrhage are mediated via estrogen receptor-alpha. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:376–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ertel W, Morrison MH, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Hypoxemia in the absence of blood loss or significant hypotension causes inflammatory cytokine release. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R160–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.1.R160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Knoferl MW, Jarrar D, Schwacha MG, Angele MK, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Severe hypoxemia in the absence of blood loss causes a gender dimorphic immune response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C2004–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wisse E. Kupffer cell reactions in rat liver under various conditions as observed in the electron microscope. J Ultrastruct Res. 1974;46:499–520. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(74)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yokoyama Y, Kitchens WC, Toth B, Schwacha MG, Rue LW, III, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Role of IL-10 in regulating proinflammatory cytokine release by Kupffer cells following trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G942–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00502.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schneider CP, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. The role of interleukin-10 in the regulation of the systemic inflammatory response following trauma-hemorrhage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ghezzi P, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor as a pharmacological target. Methods Mol Med. 2004;98:1–8. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-771-8:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen XL, Xia ZF, Wei D, Han S, Ben DF, Wang GQ. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in Kupffer cell secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines after burn trauma. Burns. 2003;29:533–9. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thobe BM, Frink M, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Src family kinases regulate p38 MAPK-mediated IL-6 production in Kupffer cells following hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C476–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00076.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Haggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–70. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hsieh YC, et al. Downregulation of TLR4-dependent ATP production is critical for estrogen-mediated immunoprotection in Kupffer cells following trauma-hemorrhage. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:364–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hsieh YC, et al. 17beta-Estradiol down-regulates Kupffer cell TLR4-dependent p38 MAPK pathway and normalizes inflammatory cytokine production following trauma-hemorrhage. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Olsson S, Sundler R. The role of lipid rafts in LPS-induced signaling in a macrophage cell line. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maung AA, Fujimi S, Miller ML, MacConmara MP, Mannick JA, Lederer JA. Enhanced TLR4 reactivity following injury is mediated by increased p38 activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:565–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jordan MS, Singer AL, Koretzky GA. Adaptors as central mediators of signal transduction in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:110–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0203-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.O’Neill LA. Toll-like receptor signal transduction and the tailoring of innate immunity: a role for Mal? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zheng R, et al. MyD88 and Src are differentially regulated in Kupffer cells of males and proestrus females following hypoxia. Mol Med. 2006;12:65–73. doi: 10.2119/2006-00030.Zheng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vickers AE, Lucier GW. Estrogen receptor levels and occupancy in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial and Kupffer cells are enhanced by initiation with diethylnitrosamine and promotion with 17alpha-ethinylestradiol in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1235–42. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fan J, et al. Hemorrhagic shock induces NAD(P)H oxidase activation in neutrophils: role of HMGB1-TLR4 signaling. J Immunol. 2007;178:6573–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Levy RM, et al. Systemic inflammation and remote organ injury following trauma require HMGB1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1538–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00272.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wichmann MW, Zellweger R, DeMaso CM, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Mechanism of immunosuppression in males following trauma-hemorrhage: critical role of testosterone. Arch Surg. 1996;131:1186–91. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430230068012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Samy TS, Schwacha MG, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Androgen and estrogen receptors in splenic T lymphocytes: effects of flutamide and trauma-hemorrhage. Shock. 2000;14:465–70. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Angele MK, et al. Gender dimorphism in trauma-hemorrhage-induced thymocyte apoptosis. Shock. 1999;12:316–22. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Angele MK, Knoferl MW, Ayala A, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Testosterone and estrogen differently effect Th1 and Th2 cytokine release following trauma-haemorrhage. Cytokine. 2001;16:22–30. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Samy TS, Knoferl MW, Zheng R, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Divergent immune responses in male and female mice after trauma-hemorrhage: dimorphic alterations in T lymphocyte steroidogenic enzyme activities. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3519–29. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Catania RA, Angele MK, Ayala A, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Dehydroepiandrosterone restores immune function following trauma-haemorrhage by a direct effect on T lymphocytes. Cytokine. 1999;11:443–50. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Samy TS, Schwacha MG, Chung CS, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Proteasome participates in the alteration of signal transduction in T and B lymphocytes following trauma-hemorrhage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1453:92–104. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Suzuki T, Shimizu T, Yu HP, Hsieh YC, Choudhry MA, Chaudry IH. Salutary effects of 17beta-estradiol on T-cell signaling and cytokine production after trauma-hemorrhage are mediated primarily via estrogen receptor-alpha. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C2103–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00488.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abraham E, Freitas AA. Hemorrhage in mice induces alterations in immunoglobulin-secreting B cells. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1015–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Abraham E, Chang YH. Hemorrhage in mice produces alterations in intestinal B cell repertoires. Cell Immunol. 1990;128:165–74. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90015-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Robinson A, Abraham E. Hemorrhage in mice produces alterations in pulmonary B cell repertoires. J Immunol. 1990;145:3734–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pietras RJ, Marquez-Garban DC. Membrane-associated estrogen receptor signaling pathways in human cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4672–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hsieh YC, Yu HP, Frink M, Suzuki T, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. G protein-coupled receptor 30-dependent protein kinase A pathway is critical in nongenomic effects of estrogen in attenuating liver injury after trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1210–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]