Abstract

Background

The hydrogenosomes of the anaerobic ciliate Nyctotherus ovalis show how mitochondria can evolve into hydrogenosomes because they possess a mitochondrial genome and parts of an electron-transport chain on the one hand, and a hydrogenase on the other hand. The hydrogenase permits direct reoxidation of NADH because it consists of a [FeFe] hydrogenase module that is fused to two modules, which are homologous to the 24 kDa and the 51 kDa subunits of a mitochondrial complex I.

Results

The [FeFe] hydrogenase belongs to a clade of hydrogenases that are different from well-known eukaryotic hydrogenases. The 24 kDa and the 51 kDa modules are most closely related to homologous modules that function in bacterial [NiFe] hydrogenases. Paralogous, mitochondrial 24 kDa and 51 kDa modules function in the mitochondrial complex I in N. ovalis. The different hydrogenase modules have been fused to form a polyprotein that is targeted into the hydrogenosome.

Conclusion

The hydrogenase and their associated modules have most likely been acquired by independent lateral gene transfer from different sources. This scenario for a concerted lateral gene transfer is in agreement with the evolution of the hydrogenosome from a genuine ciliate mitochondrion by evolutionary tinkering.

Background

Hydrogenosomes are membrane-bounded organelles of anaerobic unicellular eukaryotes that produce hydrogen and ATP. These elusive organelles were discovered in trichomonad flagellates, and eventually identified in quite a number of only distantly related unicellular anaerobes such as flagellates, amoeboflagellates, chytridiomycete fungi and ciliates [1-9]. Hydrogenosomes are phylogenetically related to both mitochondria and the various rudimentary, "mitochondrial-remnant" organelles collectively called "mitosomes" [7,9]. The latter organelles are found in organisms previously considered devoid of mitochondria, that were once named "archaezoa" by Cavalier-Smith [10], although one of them, Trichomonas vaginalis, actually was already known to contain a hydrogenosome.

The hydrogenosomes of the anaerobic ciliate Nyctotherus ovalis possess a mitochondrial genome and parts of an electron-transport chain on the one hand, and a hydrogenase on the other hand [11,12]. Because of this combination of features they cannot be classified as being either a hydrogenosome or a mitochondrion. It is likely that this organelle evolved from a ciliate mitochondrion by the expression of a hydrogenase that enables the ciliate to use protons as electron acceptors in order to maintain its metabolic homeostasis under anaerobic conditions. A crucial aspect of this hypothesis is the evolutionary origin of the N. ovalis hydrogenase itself. This is still a matter of debate since phylogenetic analyses suffer from a lack of statistical support due to an insufficient sampling of hydrogenases [13-16].

Here we present evidence that the [FeFe] hydrogenase of N. ovalis does not belong to the clade of "ancient eukaryotic" hydrogenases that also include the non-hydrogen producing NARF's, (nuclear prelamine A recognition factors, [17]). The analysis of the H-cluster of 19 novel hydrogenases from rumen ciliates that were recovered in a metagenomic approach, reveals the existence of another clade of [FeFe] hydrogenases from both bacterial and eukaryotic organisms, including the one of N. ovalis, but excluding hydrogenases from other ciliates and eukaryotes.

The [FeFe] hydrogenase of N. ovalis is unique because, by a fusion with two NADH dehydrogenase subunits, it is predicted to be capable of reoxidizing NADH directly. The two accessory domains responsible for this are homologous to the 24 kDa and 51 kDa subunits of the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) and to the bacterial "small hydrogenases" hoxF and hoxU [11,16,18]. Supporting the origin of the hydrogenase by Horizontal Gene Transfer we show here that the accessory domains are not closely related to the N. ovalis complex I subunits, but rather appear to have been acquired by lateral gene transfer from bacterial ancestors that possess a [NiFe] hydrogenase.

Results and Discussion

The 24 kDa/NuoE/hoxF – and 51 kDa/NuoF/hoxU – like regions of the [FeFe] hydrogenase polyprotein

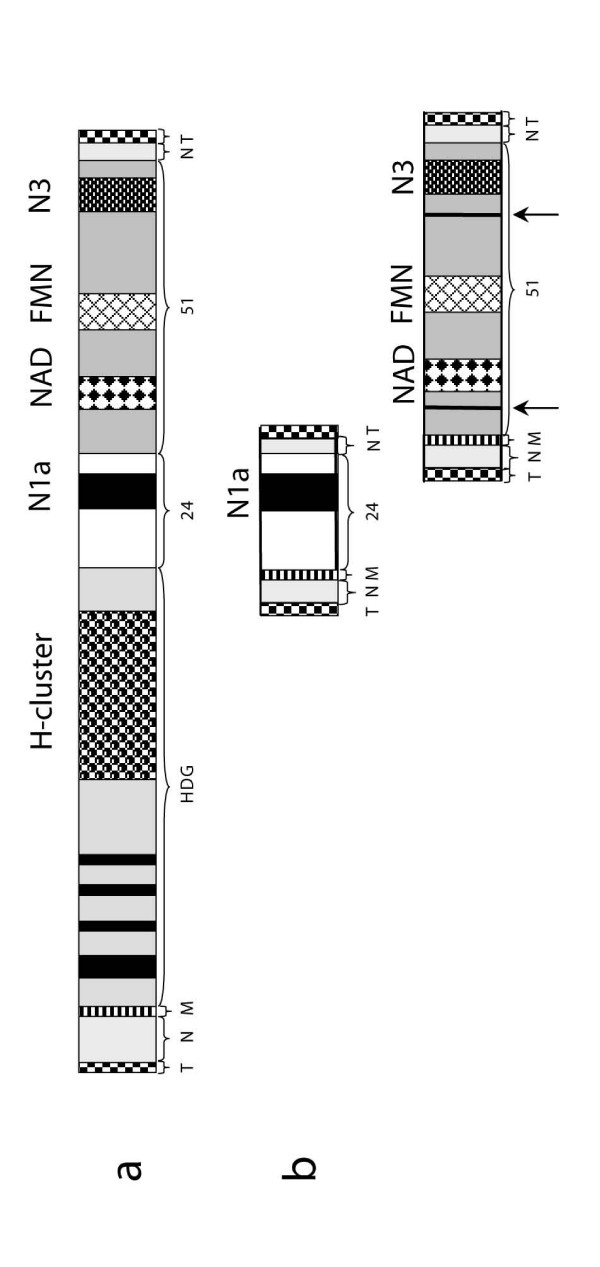

The hydrogenase of N. ovalis is a polyprotein, consisting of a long-type [FeFe] hydrogenase and two (C-terminal) modules with similarity to the 24 kDa (NuoE) and 51 kDa (NuoF) subunits of complex I of mitochondrial and eubacterial respiratory chains (Fig. 1a) [13,14,18,19]. Complex I, the NADH-quinone oxidoreductase, consist of 14 subunits in eubacteria and of up to 46 subunits in (human) mitochondria [20,21]. It catalyzes the electron transfer from NADH to the quinone pool through a series of redox centers. The 24 and 51 kDa subunits are two important modules of the hydrophilic (soluble) NADH dehydrogenase part of mitochondrial complex I. The 51 kDa subunit contains a [4Fe-4S]-cluster (also known as "N3") and binding sites for NADH and FMN. The 24 kDa subunit contains a [2Fe-2S]-cluster ("N1a") [22,23].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the minichromosomes encoding the hydrogenase (a) and the "mitochondrial" 24 and 51 kDa genes (b). The macronuclear minichromosomes are capped by telomeres (T) and contain non-coding DNA sequences (N) at the N- and C-terminal parts of the chromosome. A mitochondrial targeting signal (M) is found at the N terminal part of the coding sequence. 1. a. The hydrogenase is chimeric, i.e. it consists of a long-type [FeFe] hydrogenase with 4 FeS clusters (black bars in HDG), a 24 kDa (hoxF) module ("24") with an N1a type FeS cluster, and a 51 kDa (hoxU) ("51") module with a N3-type [4Fe-4S] cluster plus a FMN and a NAD binding site. 1. b. The subunits of the "mitochondrial" complex I are localized on individual minichromosomes. They each possess a mitochondrial targeting signal (M) and upstream and downstream non-coding DNA (N). The "mitochondrial" 51 kDa module possesses two small introns (arrows) that are absent from the correspondent hydrogenase module.

In N. ovalis two different types of 24/51 kDa genes are found: (i) a hydrogenase variant, in which both subunits are fused with each other and with a [FeFe] hydrogenase, and (ii) a "mitochondrial" variant, in which the 24 kDa and 51 kDa genes are located on separate minichromosomes (Fig. 1b). As usual for N. ovalis and some other ciliates, the genes are located on single gene containing macronuclear minichromosomes that are capped with telomeres, making it unlikely that the genes are a contamination. Consistent with their putative function in the "mitochondrial" (hydrogenosomal) complex I (see below), these genes possess N-terminal leader sequences that likely function as a mitochondrial targeting signal. In contrast, the hydrogenase consists of a fusion of the hydrogenase, the 24 kDa and the 51 kDa subunits. Obviously, this "operon" encodes a polyprotein, since it is located on a single minichromosome, and, notably, it possesses only one (N-terminal) "mitochondrial" targeting signal (Fig 1). In contrast, both "mitochondrial" 24 kDa and 51 kDa possess their individual mitochondrial targeting signal. In addition, the "mitochondrial" 51 kDa variant contains two small introns (not shown) that are absent in the fused variant.

A multiple sequence alignment of the "mitochondrial" complex I subunits and 24 kDa/hoxF and 51 kDa/hoxU -like sequences of the hydrogenases of several N. ovalis species reveals that the hydrogenase modules are more similar to the nuoE and nuoF genes of a bacterial complex I than to a mitochondrial complex I (Supplementary Material). The 24 kDa-like module of the N. ovalis hydrogenase possesses only three of the four conserved cysteine residues that bind the [2Fe-2S] cluster N1a found in both mitochondrial 24 kDa subunits and bacterial NuoE's. The fourth cysteine residue of the hydrogenosomal [2Fe-2S] cluster has been replaced consistently by a tryptophane in all N. ovalis 24 kDa subunits sequenced (Additional File 1). Stereochemical considerations and mutagenisation studies in bacterial nuoE genes have suggested that this C/W replacement most likely does not interfere with the ferredoxin-like function of the hydrogenosomal 24 kDa module [24]. The 51 kDa-like region of both the hydrogenase domain and the putative mitochondrial complex I subunits contain a NADH binding domain with four conserved glycine residues. In addition, also a FMN binding site with its conserved glycine and proline residues, and the four conserved cysteine residues of the [4Fe-4S] cluster N3 are found in both the 51 kDa subunits of mitochondrial complex I and its bacterial NuoF homologues (Fig. 1b; supplementary material).

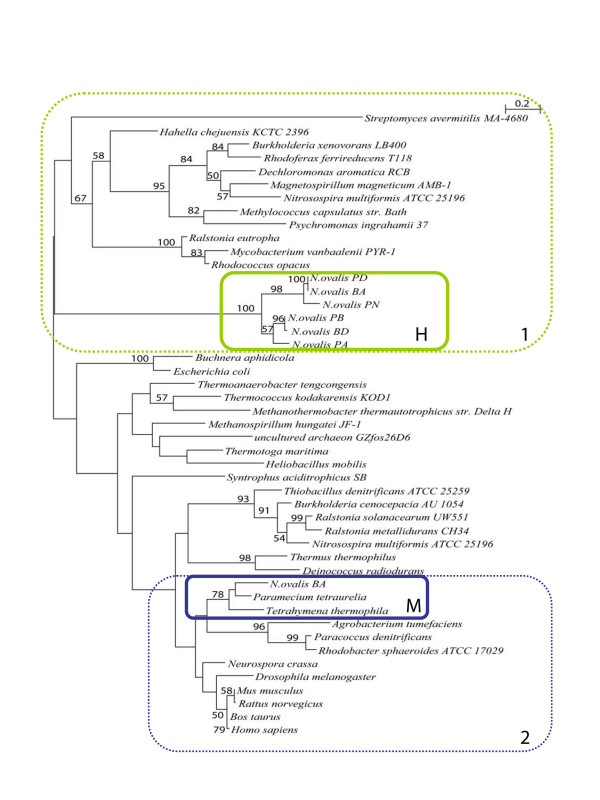

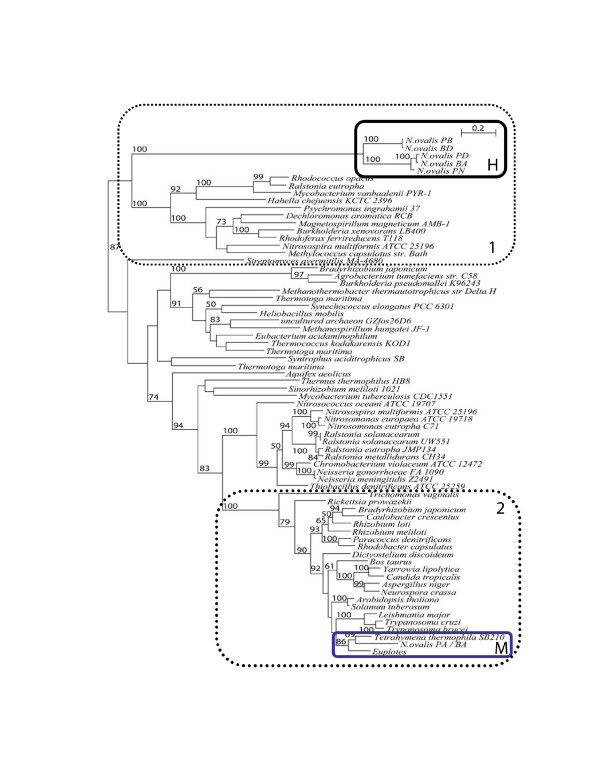

Phylogenetic analysis of the 24 kDa-like region of the N. ovalis hydrogenase is hampered by a lack of data, especially from ciliates and other protozoa. Nevertheless, it shows clearly that this module of the N. ovalis hydrogenase has a bacterial rather than a mitochondrial ancestry (Fig. 2). The 24 kDa-like module from the hydrogenase clusters with its homologues from beta- and gamma-proteobacteria and the hoxF subunits of soluble NAD-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenases of beta-proteobacteria, and not with its mitochondrial paralogues. All 24 kDa-like genes belonging to this clade are fused with their corresponding 51 kDa modules supporting the assumption of a close phylogenetic relation (with the exception of Nitrosospira multiformis). The mitochondrial 24 kDa (NuoE) subunit of N. ovalis, on the other hand, clusters closely with its homologues from aerobic, mitochondriate ciliates. This clade belongs to a mitochondrial/alpha-proteobacterial sample of sequences that are only distantly related to 24 kDa sequences from beta- and gamma- proteobacteria and archaebacteria. None these sequences is fused with a 51 kDa gene.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the 24 kDa-like module of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis, mitochondrial complex I 24 kDa subunits, bacterial NuoE, and bacterial hydrogenase subunits. See methods for the Accession Numbers and how the tree was calculated. H: N. ovalis hydrogenase, M: ciliate mitochondrial. Bootstraps are only indicated in the tree if they are ≥ 50. Box 1 marks 24 kDa modules that are fused with their corresponding 51 kDa modules (with the exception of Nitrosospira multiformis). All bacteria in this box (with the exception of Nitrosospira multiformis) have a [NiFe] hydrogenase. The mitochondrial/alpha-proteobacterial 24 kDa modules are not fused with their 51 kDa counterparts (Box 2).

Similar to the phylogeny of the 24 kDa modules, phylogenetic analysis of the 51 kDa module of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis shows that it is closely related to the hoxF subunits of soluble NAD-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenases of beta-proteobacteria such as Rhodococcus opacus and Ralstonia eutropha, and the fused variants from beta- and gamma-proteobacteria (Fig. 3). The hydrogenase module of N. ovalis is more distantly related to the nuoF and 51 kDa genes of the various representatives of alpha-proteobacterial or mitochondrial complex I genes. In contrast, the mitochondrial 51 kDa subunit of N. ovalis clusters with high support with its homologues from aerobic (mitochondriate) ciliates and many other eukaryotes and alpha-proteobacteria. It is also clearly distinct from the corresponding NADP/formate reducing hydrogenases of certain archaea and alpha proteobacteria (Fig. 3). These observations unequivocally exclude a mitochondrial or alpha-proteobacterial origin of the 24 and 51 kDa modules of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the 51 kDa-like module of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis, mitochondrial complex I 51 kDa subunits, bacterial NuoF, and bacterial hydrogenase subunits. See methods for how the tree was calculated. H: N. ovalis hydrogenase, M: ciliate mitochondrial. Only bootstraps ≥ 50 are indicated in the tree. Box 1 marks the fused modules (with the exception of Nitrosospira multiformis), Box 2 the non-fused modules of mitochondrial and alpha-proteobacterial origin. All bacteria in Box 1 (with the exception of Nitrosospira multiformis) have a [NiFe] hydrogenase.

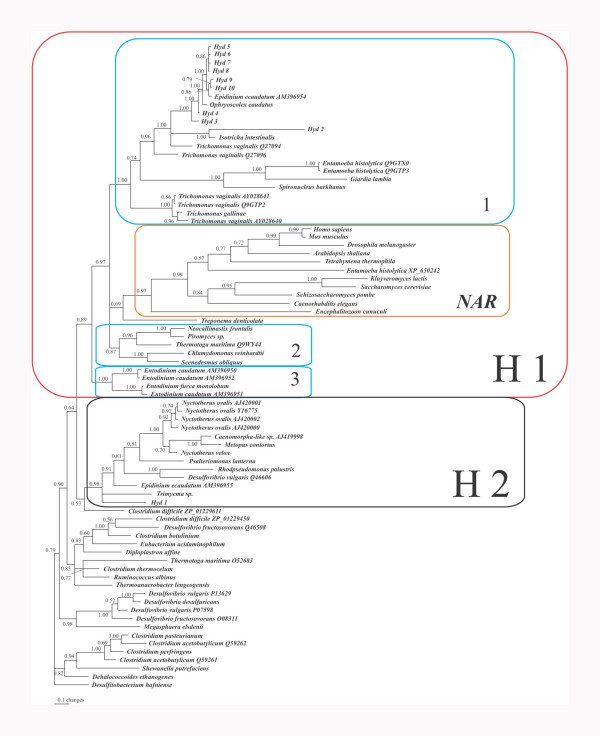

The phylogenetic analysis of the complete hydrogenase of N. ovalis is hampered by the high sequence conservation and the modular organisation of the bacterial and eukaryotic [FeFe] hydrogenases [15,19]. This implicates that only the "H-cluster", a rather small piece of the total hydrogenase, can be used in a phylogenetic analysis that includes all eukaryotic [FeFe] hydrogenases. Also, the very limited sampling of eukaryotic hydrogenases restricts the phylogenetic reconstruction, suggesting an unresolved, deep eukaryotic origin for most of these hydrogenases [13-16]. Therefore, we undertook a metagenomic approach to retrieve hydrogenase-encoding DNA sequence information from the highly diverse and numerous community of anaerobic ciliates thriving in the rumen of cattle, sheep, and goat [25,26]. Using primers directed against conserved regions of the H-cluster (that is shared by all [FeFe] hydrogenases and the functionally unrelated NAR's [15]) we sequenced 10 clones derived from the total rumen ciliate DNA. In addition, we determined the homologous DNA sequences from 9 validated type strains of rumen ciliates. Phylogenetic analysis of this extended data set reveals the existence of two clades of eukaryotic [FeFe] hydrogenases, indicated by H1 and H2 in Figure 4. The H1 clade contains the majority of the eukaryotic sequences, including the NAR'S.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the H-cluster of [FeFe]-hydrogenases and NARs or NARs-like proteins. Accession numbers of sequences are indicated when more than one sequence from a species is included. The numbers at the nodes represent the posterior probability resulting from a Bayesian inference. Hyd 1–10: H-clusters recovered from a metagenomic approach using DNA from total ciliate population in the rumen of a cow. The H1 block marks the "classical " [FeFe] hydrogenases and NAR's. Block 1 is characterized by the clade of Trichomonas vaginalis (long and short – type) hydrogenases. It hosts also the majority of the rumen sequences plus the hydrogenases from the type-strain rumen ciliates Epidinium ecaudatum, Ophryoscolex caudatus, and Isotricha intestinalis. Block 2 marks the long-type hydrogenases from the anaerobic chytridiomycetes Neocallimastix and Piromyces and the (short) plastidic hydrogenases from the algae Chlamydomonas and Scenedesmus. Block 3 marks H-clusters from rumen ciliates that are likely to lack hydrogenosomes. Block H2 marks a well supported clade of Fe hydrogenases dominated by N. ovalis. Besides N. ovalis and its close relatives, this clade consists of hydrogenases from the amoeboflagellate Psalteriomonas lanterna, the rumen ciliate Epidinium ecaudatum, the free-living ciliate Trimyema sp. and the rumen (meta) sequences Hyd 1. A fusion of the H-cluster with the 24 and 51 kDa modules has so far only been observed for the N. ovalis clade. The Psalteriomonas hydrogenase has no fused 24/51 kDa modules.

The H2 clade comprises all hydrogenase sequences from N. ovalis and its intestinal and free-living relatives. In addition, the H-clusters from two rumen ciliates, one amoeboflagellate, and the ciliate Trimyema sp. belong to this clade – besides sequences from the delta-proteobacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris and the alpha-proteobacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. A bacterial, i.e. endo/episymbiotic origin of the sequences derived from the two rumen ciliates and the ciliate Trimyema cannot be excluded at the current state of information. The ciliate origin of the N. ovalis sequences has been confirmed by their assignment to gene-sized macronuclear chromosomes that are characteristic for Nyctotherus and its relatives. Furthermore, the codon usage is characteristic for N. ovalis (see below). The hydrogenase of the amoeboflagellate Psalteriomonas lanterna, on the other hand has recently been recovered from cDNA thereby revealing the absence of C-terminal 24/51 kDa modules (unpublished). Thus, the existence of two different eukaryotic hydrogenase clades is clearly supported, with a clustering of the N. ovalis sequence with those from Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Rhodopseudomonas palustris. The relationship of both clades to other bacterial hydrogenases remains poorly resolved, but there is no evidence for any close relationship to those bacterial taxa that are supposed to be the source for the hydrogenosomal 24/51 kDa modules.(Fig. 2, 3,), indicating an independent origin for the hydrogenase on the one hand and the 24/51 kDa modules on the other hand.

The [FeFe] hydrogenase of N. ovalis is chimeric and has been acquired by lateral gene transfer

As shown above, the 24 kDa and 51 kDa modules of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis are neither of mitochondrial nor of alpha-proteobacterial origin. Given the presence of paralogues of genuine mitochondrial descent that encode constituents of a functional mitochondrial/hydrogenosomal complex I [11], an acquisition of the whole hydrogenase by lateral gene transfer from different sources is very likely.

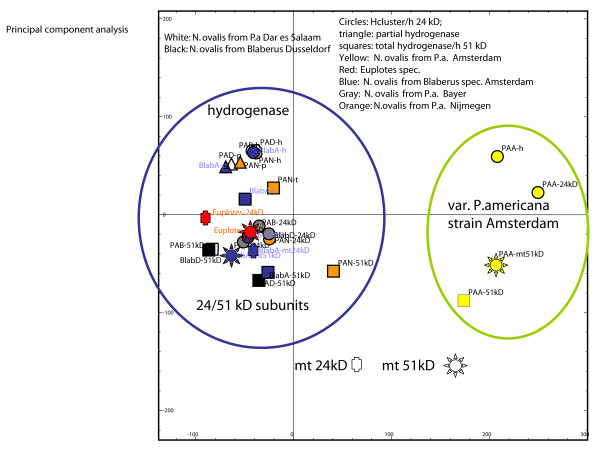

Both the 24 kDa and 51 kDa modules might have been acquired from beta-proteobacteria similar to Rhodococcus or Ralstonia, which possess [NiFe] hydrogenase modules, rather than [FeFe] hydrogenases [19]. Notably, in Rhodococcus or Ralstonia the 24 kDa and 51 kDa subunits belong to a rather oxygen-resistant [NiFe] hydrogenase, which is not homologous to the [FeFe]-hydrogenases [13-16,18,19,27,28]. An analysis of the codon usage of the various hydrogenase components and their mitochondrial orthologues (Fig. 5) reveals that (1) the hydrogenase modules have acquired the host-specific codon-usage, (2) hydrogenase modules cluster with hydrogenase modules, and (3) mitochondrial genes with mitochondrial genes.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis of the codon-usage of the hydrogenase and mitochondrial 24/51 kDa modules. While most of the N. ovalis strains exhibit only slight differences in codon-preference, the isolate N. ovalis from the host cockroach P. americana strain Amsterdam has a substantially different codon-usage. In both cases, the bacterial-derived 24 and 51 kDa modules acquired the typical ciliate codon-usage that is not significantly different from the one used for the (nuclear-encoded) mitochondrial modules. Even the top-down distribution shows a complete ameliorisation of the modules.

Why acquire a [FeFe]-only hydrogenase?

We have shown recently that the hydrogenosome of N. ovalis is a ciliate-type mitochondrion that produces hydrogen [11]. The presence of a mitochondrial genome, mitochondrial complex I and II dependent respiratory-chain activity, in combination with a kind of fumarate-respiration identifies the N. ovalis hydrogenosome as an intermediate stage in the evolution of mitochondria to hydrogenosomes [11,12]. But why acquire a [FeFe]hydrogenase at all? It is likely that the ancestral mitochondrion of N. ovalis oxidised NADH via an electron transport chain – as indicated by the presence of genes encoding components of mitochondrial complex I and II. An adaptation to anaerobic environments might be greatly facilitated by the acquisition of a hydrogenase, which could use NADH. It is obvious that the use of fumarate alone as endogenous electron acceptor requires a well-controlled balance between the various catabolic and anabolic reactions in the cell. Depending on the metabolic state of the cell, the NADH pool might be subject to large fluctuations. The presence of alternative oxidases in anaerobic mitochondria provides a means for the cell to cope with such fluctuations in the NADH pool [29]. Such an alternative oxidase appears to be absent in N. ovalis, and the hydrogenase could fulfil the task to regulate the NADH pool. The chimeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase of N. ovalis is tailored for this requirement since it allows a direct re-oxidation of NADH, due to the presence of the 24 and 51 kDa modules. Other [FeFe] hydrogenases, e.g. those of Trichomonas vaginalis, require ferredoxin for hydrogen production from PFO-generated reduction equivalents, and a diaphorase to reoxidise NADH. Thus, a hydrogenase like the one found in N. ovalis, provides many advantages for an organism adapting to anaerobic environments. Since there is no evidence for the presence of hydrogenases in mitochondria/protomitochondria [30,31], the scenario for the evolution of the hydrogenosomes of N. ovalis from ciliate mitochondria as described here, is likely to have involved complex lateral gene transfer and the fusion of functional domains. The fusion of genes of different origin has at least two advantages: guaranteeing the synthesis of all components in equimolar amounts, and facilitating the flow of electrons from NADH to H+ in a single molecule. Lastly, the evolution of a hydrogenosomal polyprotein requires only the acquisition of a single mitochondrial targeting signal, which can be acquired easily as demonstrated by the frequent retargeting of proteins in the evolution of the eukaryotic cell [31,32].

Hydrogenases and the origin of mitochondria

The scenario depicted here for the origin of the N. ovalis hydrogenase, in which a hydrogenase was added to an aerobic mitochondrion does not necessarily hold for other hydrogenosomes, because they have evolved independently of N. ovalis and because they are metabolically less similar to mitochondria than is the N. ovalis organelle, e.g. in the way they metabolise pyruvate. N. ovalis uses a "mitochondrial" pyruvate dehydrogenase that reduces NAD, which can subsequently be reoxidized by the hydrogenase that has acquired NADH-oxidizing domains. In contrast, the hydrogenosome of Trichomonas species metabolise pyruvate via a pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase[1] and the anaerobic chytrids metabolise it via a pyruvate formate-lyase[33]. The proteins in the hydrogenosomes of anaerobic chytrids are phylogenetically related to the proteins in the mitochondria of aerobic fungi, suggesting also here the evolution of the hydrogenosome as a secondary adaptation to anaerobic circumstances. Trichomonas, however, appears in many-sequence based phylogenies at the root of the eukaryotic tree and does not have aerobic, mitochondria containing relatives. A scenario as depicted in the hydrogen hypothesis of Martin and Müller [34], in which the ancestral organelle of all mitochondria and hydrogenosomes had both a respiratory chain and a hydrogenase can therefore not be ruled out. It should thereby be noted that T. vaginalis, just like N. ovalis has the NADH oxidizing elements of complex I, but, in contrast to N. ovalis, does not have the other proteins of this complex [35], and is with respect to complex I more like Schizosaccharomyces pombe [21].

Conclusion

N. ovalis acquired its unique [FeFe] hydrogenase by lateral gene transfer from two different sources. Given that N. ovalis performs a kind of fumarate respiration allowing survival under anaerobic conditions, the acquisition of this peculiar [FeFe] hydrogenase allows an additional regulation of the NADH pool, which is crucial for maintaining the metabolic homeostasis under anaerobic conditions.

Methods

Isolation (and culture) of the ciliates

N. ovalis was isolated from the hindgut of the cockroaches Periplaneta americana strains Amsterdam (PA), Bayer (PB), Dar es Salaam (PD), Nijmegen(PN) and Blaberus sp. strains Düsseldorf (BD) and Amsterdam (BA) taking advantage of the unique anodic galvanotaxic behaviour of N. ovalis [36].Euplotes sp. was grown in Erlenmeyer flasks containing 500 ml artificial seawater (465 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 53 mM MgCl2, 28 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM CaCl2, and 0.23 mM NaHCO3). Since Euplotes sp. requires living bacteria for growth, E. coli XL1-blue was supplied at regular intervals. Alternatively, a small piece of beef-steak (approximately 1 cm3) was placed into the culture medium to allow the growth of food bacteria. Euplotes sp. cells were harvested 28 days after the start of a new culture by filtration through a 4 μm plankton gaze.

Rumen ciliates were isolated by electromigration from the rumen fluid of a grass-fed, fistulated Holstein-Friesian cow, and lysed immediately after the isolation in a 8 M solution of guanidinium chloride and stored at minus 25°C until use.

DNA isolation, total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

DNA of N. ovalis and Euplotes sp. was isolated according to van Hoek et al. [37]. Total rumen ciliate DNA was prepared after purification on a hydroxyapatite column (BioRad) using standard methods. Total RNA of N. ovalis was isolated using the RNeasy Plant mini-kit (Qiagen). Adaptor-ligated cDNA was prepared according to the SMART™ RACE cDNA Amplification kit (Clontech).

Isolation of the H-cluster, the 24 kD (hoxF) and 51 kD (hoxU) modules of the hydrogenase gene, and mitochondrial-type 24 kDa and 51 kDa subunits of mitochondrial complex I

H-clusters of Fe-hydrogenases were amplified from total rumen ciliate DNA using PCR with primers described earlier [15]. In addition, DNA from type-strain rumen ciliates, kept by the ERCULE consortium was used as template for PCR.

To isolate the (nuclear-encoded) 24 kD (hoxF) and 51 kD (hoxU) -like genes, the primer-design was based on the H-cluster and the 24 kD (hoxF) and 51 kD (hoxU) region of the hydrogenase of N. ovalis PN [18]. Their sequences are 5'-gtnatggcntgyccngghgghtg-3' (H-cluster forward primer) and 5'-ccntcyctrcadggnacrcaytg-3' (51 kDa reverse primer 1). Sequence-specific internal primers were designed to isolate the termini of the gene-sized chromosomes in combination with a telomere-specific primer using the telomere suppression PCR method [38,39].

To isolate the (nuclear) genes encoding the 24 kDa and 51 kDa subunits of mitochondrial complex I, respectively, primers were based on conserved amino-acid regions of mitochondrial complex I genes. Their sequences are 5'-tgyggwachachccwtg-3' (24 kDa forward primer), 5'-ccnarrcaytcdacytc-3' (24 kDa reverse primer), 5'-gmhgargghgarccwgghac-3' (51 kDa forward primer), and 5'-cangwcatytcytcytcnac-3' (51 kDa reverse primer). The ORFs were completed as described above.

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences of the H-cluster were aligned using Clustal × 1.81 [40]. The program Gblocks [41] was used to identify regions of defined sequence conservation and exclude ambiguously aligned positions from the alignment. The phylogenetic analysis of the sequences were performed with the program MRBAYES version 3.1.2 [42]. Markov chain Monte Carlo from a random starting tree was initiated and run for 2 million generations. In these analyses, the JTT model of amino acid substitution and four gamma distributed rates of evolution were applied. Trees were sampled every 1000th generation. The first 25% of the samples were discarded as 'burn-in', and the rest of the samples were used for inferring a Bayesian tree. Examination of the log-likelihood and the observed consistency with the similar likelihood values between the two independent runs suggest that the run reached stationarity and that these burn-in periods were sufficiently long.

The accession numbers of the sequences used to calculate this tree are Nyctotherus ovalis BA AY608627; N. ovalis PN CAA76373; the sequences from rumen ciliates have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AM396939 – AM396957

For the 24kD/51kD domains less sequences had to be included to delineate the evolution, allowing a "manual" sequence alignment and phylogeny approach. Alignments of representative sequences from the 24kD/51kD domains were generated with MUSCLE [43]. Sequences were edited and the most relevant parts from the alignments were selected manually using Seaview [44]. Phylogenies were subsequently derived using the program PHYML [45] using the JTT model and an estimated number of invariable sites with four substitution rate categories. 100 bootstraps were performed; they are only indicated in the tree if they are ≥ 50.

The accession numbers of the used 24 kDa subunit/NuoE/hoxF sequences are [Agrobacter tumefaciens PIR:D97514, Bos taurus Swiss-Prot:P04394, Buchnera aphidicola Swiss-Prot:P57255, Burkholderia cenocepacia AU 1054 REFSEQ:YP_621511.1, Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 REFSEQ:YP_555778.1, Dechloromonas aromatica RCB GenBank:AAZ45735.1, Deinococcus radiodurans REFSEQ:NP_295224, Drosophila melanogaster GenBank:AAL68189, Escherichia coli Swiss-Prot:P33601, Hahella chejuensis KCTC 2396 REFSEQ:YP_431454.1, Heliobacillus mobilis EMBL:CAJ44288.1, Homo sapiens REFSEQ:NP_066552, Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 REFSEQ:YP_422756.1, Methanospirillum hungatei JF-1 REFSEQ:YP_502735.1, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus str. Delta H GenBank:AAB86022.1, Methylococcus capsulatus str. Bath REFSEQ:YP_115124.1, Mus musculus Swiss-Prot:Q9D6J6, Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 REFSEQ:ZP_01205720.1, N. ovalis BA (24 kDa) GenBank:AY628688, N. ovalis BD GenBank:AY608628, N. ovalis PA GenBank:AY608629, N. ovalis PB GenBank:AY608630, N. ovalis PD GenBank:AY608631, N. ovalis PN GenBank:CAA76373, Neurospora crassa Swiss-Prot:P40915, Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 REFSEQ:YP_411790.1, Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 REFSEQ:YP_412360.1, Nyctotherus ovalis BA GenBank:AY608627, Paracoccus denitrificans Swiss-Prot:P29914, Paramecium tetraurelia Swiss-Prot:Q6BFW6, Psychromonas ingrahamii 37 REFSEQ:ZP_01348563.1, Ralstonia eutropha GenBank:AAC06140, Ralstonia metallidurans CH34 REFSEQ:YP_583086.1, Ralstonia solanacearum UW551 REFSEQ:ZP_00943354.1, Rattus norvegicus Swiss-Prot:P19234, Rhodobacter sphaeroides ATCC 17029 REFSEQ:ZP_00918830.1, Rhodococcus opacus Swiss-Prot:P72304, Rhodoferax ferrireducens T118 REFSEQ:YP_525088.1, Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 REFSEQ:NP_823011.1, Syntrophus aciditrophicus SB REFSEQ:YP_461127.1, Tetrahymena thermophila Swiss-Prot:Q23LJ5, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis GenBank:AAM24146, Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1 DDBJ:BAD85803.1, Thermotoga maritima REFSEQ:NP_227828, Thermus thermophilus Swiss-Prot:Q56221, Thiobacillus denitrificans ATCC 25259 REFSEQ:YP_314904.1, uncultured archaeon GZfos26D6 GenBank:AAU83055.1]

The accession numbers of the 51 kDa subunit/NuoF/hoxU sequences are [Agrobacterium tumefaciens Swiss-Prot:Q8U6U9, Aquifex aeolicus Swiss-Prot:O66841, Arabidopsis thaliana Swiss-Prot:Q8LAL7, Aspergillus niger Swiss-Prot:Q92406, Bos taurus GenBank:AF092131, Bradyrhizobium japonicum DDBJ:BAC48402, DDBJ:BAC50177, Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 REFSEQ:YP_555778.1, Candida tropicalis Swiss-Prot:Q96UX4, Caulobacter crescentus Swiss-Prot:Q9A6X9, Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC 12472 REFSEQ:NP_900616.1, Dechloromonas aromatica RCB GenBank:AAZ45735.1, Dictyostelium discoideum REFSEQ:XP_636489.1, Eubacterium acidaminophilum EMBL:CAC39230.1, Euplotes sp. GenBank:AY608636, Hahella chejuensis KCTC 2396 REFSEQ:YP_431454.1, Heliobacillus mobilis EMBL:CAJ44288.1, Leishmania major Swiss-Prot:Q9U4M2, Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 REFSEQ:YP_422756.1, Methanospirillum hungatei JF-1 REFSEQ:YP_502736.1, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus str. Delta H GenBank:AAB86023.1, Methylococcus capsulatus str. Bath REFSEQ:YP_115124.1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis Swiss-Prot:P95176, Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 REFSEQ:ZP_01205720.1, N. ovalis BA (51 kDa) GenBank:AY608632, N. ovalis BD GenBank:AY608628, N. ovalis PA (51 kDa) GenBank:AY608635, N. ovalis PB GenBank:AY608630, N. ovalis PD GenBank:AY608631, N. ovalis PN GenBank:CAA76373, Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA 1090 REFSEQ:YP_208779.1, Neisseria meningitidis Z2491 EMBL:CAB83334.1, Neurospora crassa Swiss-Prot:P24917, Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707 GenBank:ABA59013.1, Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718 EMBL:CAD85683.1, Nitrosomonas eutropha C71 REFSEQ:ZP_00669832.1, Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 REFSEQ:YP_411791.1, REFSEQ:YP_412360.1, Nyctotherus ovalis BA GenBank:AY608627, Paracoccus denitrificans Swiss-Prot:P29913, Psychromonas ingrahamii 37 REFSEQ:ZP_01348563.1, Ralstonia eutropha GenBank:AAC06140, Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 GenBank:AAZ60345.1, Ralstonia metallidurans CH34 REFSEQ:YP_583087.1, Ralstonia solanacearum EMBL:CAD15764.1, Ralstonia solanacearum UW551 REFSEQ:ZP_00943355.1, Rhizobium loti Swiss-Prot:Q98BW8, Swiss-Prot:Q98KR0, Rhizobium meliloti Swiss-Prot:P56912, Swiss-Prot:P56913, Rhodobacter capsulatus Swiss-Prot:O07948, Rhodococcus opacus Swiss-Prot:P72304, Rhodoferax ferrireducens T118 REFSEQ:YP_525088.1, Rickettsia prowazekii Swiss-Prot:Q9ZE33, Solanum tuberosum Swiss-Prot:Q43840, Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 REFSEQ:NP_823011.1, Synechococcus elongatus PCC 6301 EMBL:CAA73873.1, Syntrophus aciditrophicus SB REFSEQ:YP_461127.1, Tetrahymena thermophila SB210 GenBank:EAR96899.1, Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1 DDBJ:BAD85803.1, Thermotoga maritima Swiss-Prot:O52682, Swiss-Prot:Q9WXM5, Swiss-Prot:Q9WY70, Thermus thermophilus Swiss-Prot:Q56222, Thiobacillus denitrificans ATCC 25259 REFSEQ:YP_314905.1, Trypanosoma brucei REFSEQ:XP_824451.1, Trypanosoma cruzi GenBank:EAN82122.1, uncultured archaeon GZfos26D6 GenBank:AAU83054.1, Yarrowia lipolytica Swiss-Prot:Q9UUU2]

Multivariate Comparative Analysis

The codon usage of the genes investigated in this study was subjected to a multivariate analysis by means of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualise the genetic diversity of the ciliate species. PCA was performed using the GeneMaths XT software package (Applied Maths BVBA, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium [46]).

Authors' contributions

GR, SYMVDS and GWMVDS designed the phylogenetic analyses and performed the computional sequence analysis

AHAMVH and NRME performed the codon-usage analyses

BB, AHAMVH, ES, GWMVDS, TAVA, RMDG, GC, MK, isolated and cloned the various – hydrogenase and complex I – genes.

TM, JPJ, NRME, CJN and PP established ciliate cell lines for DNA extraction

BB, GR, SYMVDS, AHAMVH, NRME, CJN, MAH, and JHPH participated in drafting the manuscript

JHPH and MAH initiated and coordinated the study, and JHPH wrote the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Multiple sequence alignment of the 24/51 kDa modules

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. TM Embley for providing the Trimyema sequence and the referees for their comments. The work has been supported by the EU 5th framework projects ERCULE (QLRI-CT-2000-01455) and CIMES (QLK3-2002-02151)

Contributor Information

Brigitte Boxma, Email: Brigitte.Boxma@intervet.com.

Guenola Ricard, Email: guenola@cmbi.kun.nl.

Angela HAM van Hoek, Email: angela.vanhoek@wur.nl.

Edouard Severing, Email: edouard.severing@wur.nl.

Seung-Yeo Moon-van der Staay, Email: SMoonvds@aol.com.

Georg WM van der Staay, Email: GvanderStaay@aol.com.

Theo A van Alen, Email: T.vanAlen@science.ru.nl.

Rob M de Graaf, Email: exorest@sci.kun.nl.

Geert Cremers, Email: cremers.geert@gmail.com.

Michiel Kwantes, Email: kwantes@mpiz-koeln.mpg.de.

Neil R McEwan, Email: nrm@aber.ac.uk.

C Jamie Newbold, Email: cjn@aber.ac.uk.

Jean-Pierre Jouany, Email: Jouany@Clermont.inra.fr.

Tadeusz Michalowski, Email: t.michalowski@ifzz.pan.pl.

Peter Pristas, Email: pristas@saske.sk.

Martijn A Huynen, Email: huynen@cmbi.kun.nl.

Johannes HP Hackstein, Email: j.hackstein@science.ru.nl.

References

- Müller M. The hydrogenosome. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2879–2889. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger AJ. Reconstructing Early Events in Eukaryotic Evolution. Am Nat. 1999;154:S146–S163. doi: 10.1086/303290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstein JHP, Akhmanova A, Voncken F, van Hoek A, van Alen T, Boxma B, Moon-van der Staay SY, van der Staay G, Leunissen J, Huynen M, Rosenberg J, Veenhuis M. Hydrogenosomes: convergent adaptations of mitochondria to anaerobic environments. Zoology. 2001;104:290–302. doi: 10.1078/0944-2006-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Hoffmeister M, Rotte C, Henze K. An overview of endosymbiotic models for the origins of eukaryotes, their ATP-producing organelles (mitochondria and hydrogenosomes), and their heterotrophic lifestyle. Biol Chem. 2001;382:1521–1539. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley TM, van der Giezen M, Horner DS, Dyal PL, Bell S, Foster PG. Hydrogenosomes, mitochondria and early eukaryotic evolution. IUBMB Life. 2003;55:387–395. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001592834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarlett N, Hackstein JHP. Hydrogenosomes: One organelle, multiple origins. Bioscience. 2005;55:657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Embley TM, Martin W. Eukaryotic evolution, changes and challenges. Nature. 2006;440:623–630. doi: 10.1038/nature04546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley TM. Multiple secondary origins of the anaerobic lifestyle in eukaryotes. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci. 2006;361:1055–1067. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstein JHP, Tjaden J, Huynen M. Mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes: products of evolutionary tinkering! Curr Genet. 2006;50:225–245. doi: 10.1007/s00294-006-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:953–994. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.953-994.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxma B, de Graaf RM, van der Staay GWM, van Alen TA, Ricard G, Gabaldon T, van Hoek AHAM, Moon-van der Staay SY, Koopman WJH, van Hellemond JJ, Tielens AGM, Friedrich T, Veenhuis M, Huynen MA, Hackstein JHP. An anaerobic mitochondrion that produces hydrogen. Nature. 2005;434:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature03343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W. The missing link between hydrogenosomes and mitochondria. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner DS, Foster PG, Embley TM. Iron hydrogenases and the evolution of anaerobic eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1695–1709. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner DS, Heil B, Happe T, Embley TM. Iron hydrogenases–ancient enzymes in modern eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voncken FGJ, Boxma B, van Hoek AHAM, Akhmanova AS, Vogels GD, Huynen M, Veenhuis M, Hackstein JHP. A hydrogenosomal [Fe]-hydrogenase from the anaerobic chytrid Neocallimastix sp. L2. Gene. 2002;284:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstein JHP. Eukaryotic Fe-hydrogenases – old eukaryotic heritage or adaptive acquisitions? Trans Biochem Soc. 2005;33:47–50. doi: 10.1042/BST0330047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton RM, Worman HJ. Prenylated prelamin A interacts with Narf, a novel nuclear protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30008–30018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova AS, Voncken FGJ, van Alen TA, van Hoek AHAM, Boxma B, Vogels GD, Veenhuis M, Hackstein JHP. A hydrogenosome with a genome. Nature. 1998;396:527–528. doi: 10.1038/25023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignais PM, Billoud B, Meyer J. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:455–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich T, Böttcher B. The gross structure of the respiratory complex I: a Lego system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1608:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldon T, Rainey D, Huynen MA. Tracing the evolution of a large protein complex in the eukaryotes, NADH : Ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Complex I) J Mol Biol. 2005;348:857–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis D, Weidner U, Conzen C, Azevedo JE, Nehls U, Röhlen D, Vander Pas J, Sackmann U, Schneider R, Werner S, Weiss H. Primary structures of two subunits of NADH:ubiquinonereductase from Neurospora crassa concerned with NADH-oxidation. Relationship to a soluble NAD-reducing hydrogenase of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1190:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90049-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Finel M, Korolik V, Mendz GL. Characteristics of the aerobic respiratory chains of the microaerophiles Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter pylori. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s002030000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. Ferredoxins of the third kind. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AG, Coleman GS. The rumen protozoa. New York: Springer Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Regensbogenova M, Pristas P, Javorsky P, Moon-van der Staay SY, van der Staay GWM, Hackstein JHP, Newbold CJ, McEwan NR. Assessment of ciliates in the sheep rumen by DGGE. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;39:144–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EA, van der Giezen M, Horner DS, Embley TM, Howe CJ. An [Fe] hydrogenase from the anaerobic hydrogenosome-containing. fungus Neocallimastix frontalis. 2002;296:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleijlevens B, Buhrke T, van der Linden E, Friedrich B, Albracht SPJ. The auxiliary protein HypX provides oxygen tolerance to the soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase of Ralstonia eutropha H16 by way of a cyanide ligand to nickel. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46686–46691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens AGM, van Hellemond JJ. Anaerobic mitochondria: properties and origins. In: Martin WF, Müller M, editor. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2007. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldon T, Huynen MA. Reconstruction of the proto-mitochondrial metabolism. Science. 2003;301:609–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1085463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldon T, Huynen MA. Shaping the mitochondrial proteome. Biochim Biophys Acta-Bioenerg. 2004;1659:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.07.011. Sp. Iss. SI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser C, Ahmadinejad N, Wiegand C, Rotte C, Sebastiani F, Gelius-Dietrich G, Henze K, Kretschmann E, Richly E, Leister D, Bryant D, Steel MA, Lockhart PJ, Penny D, Martin W. A genome phylogeny for mitochondria among alpha-proteobacteria and a predominantly eubacterial ancestry of yeast nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1643–1660. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxma B, Voncken F, Jannink S, van Alen T, Akhmanova A, van Weelden SW, van Hellemond JJ, Ricard G, Huynen M, Tielens AG, Hackstein JH. The anaerobic chytridiomycete fungus Piromyces sp. E2 produces ethanol via pyruvate:formate lyase and an alcohol dehydrogenase E. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Müller M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature. 1998;392:37–41. doi: 10.1038/32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy I, Hirt RP, Dolezal P, Bardonova L, Foster PG, Tachezy J, Embley TM. Trichomonas hydrogenosomes contain the NADH dehydrogenase module of mitochondrial complex I. Nature. 2004;432:618–622. doi: 10.1038/nature03149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek AHAM, Sprakel VS, van Alen TA, Theuvenet AP, Vogels GD, Hackstein JHP. Voltage-dependent reversal of anodicgalvanotaxis in Nyctotherus ovalis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek AHAM, van Alen TA, Sprakel VSI, Hackstein JHP, Vogels GD. Evolution of anaerobic ciliates from the gastrointestinal tract: Phylogenetic analysis of the ribosomal repeat from Nyctotherus ovalis and its relatives. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1195–1206. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis EA, Landweber LF. Evolution of gene scrambling in ciliate micronuclear genes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;870:349–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert PD, Chenchik A, Kellogg DE, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov SA. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1087–1088. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.6.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmougin F, Thompson JD, Gouy M, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:403–405. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.applied-maths.com

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multiple sequence alignment of the 24/51 kDa modules