Abstract

An adult female Toggenburg goat with a history of acute vaginal bleeding and death was presented for postmortem examination. Necropsy, histologic examination, and immunohistochemical staining revealed the presence of a leiomyoma that originated from the uterine cervix, occupied most of the vaginal lumen, and had a bleeding, frayed artery in the caudal end.

Résumé

Léiomyome cervical chez une chèvre âgée conduisant à une hémorragie massive et à la mort. Une chèvre Toggenbourg adulte ayant une histoire de saignement vaginal aigu et de mort a été présentée pour examen post-mortem. La nécropsie, l’histologie et la coloration immunohistochimique ont révélé la présence d’un léiomyome provenant du col de l’utérus. La tumeur occupait la plus grande partie de la lumière vaginale et montrait une artère hémorragique déchirée à l’extrémité caudale.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

A 17-year-old of female, nonpregnant Toggenburg goat was presented for postmortem examination with a history acute (6 h) profuse vaginal bleeding and death. A large mass had been palpated in the vagina before death by the submitting veterinarian.

Case description

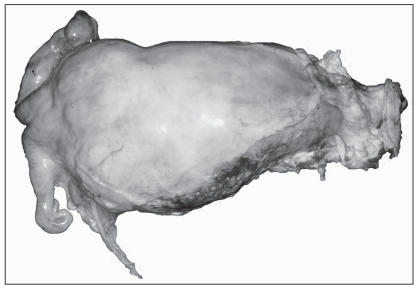

A postmortem examination was performed. Necropsy revealed a carcass in a fresh state of postmortem preservation and in good nutritional condition, but with most organs and tissues showing diffuse pallor. A discrete, firm, whitish polypoid mass that originated from the uterine cervix occupied most of the vaginal lumen and was covered by a thick fibrous capsule. The mass showed no adherences to the vagina, which, except for the distention and the presence of blood clots, looked grossly unremarkable. The tumor was roughly oval, measured 30 cm by 25 cm, weighed approximately 2 kg (Figure 1) and showed a 4-cm irregular area of hemorrhage on its ventral surface at its caudal end. Within this area, a superficial artery, approximately 0.5 cm in diameter, was frayed (Figure 2) and a large blood clot was adherent to its torn edges. Large blood clots were present in the caudal part of the vagina and the perineal area was extensively matted with blood. The uterine horns and body had a normal appearance. Multiple atretic follicles were seen in both ovaries. No distant metastases or other gross changes were observed.

Figure 1.

Leiomyoma arising from the uterine cervix of a goat and occupying most of the vagina. The vagina is unopened.

Figure 2.

Leiomyoma from the uterine cervix of a goat. The vagina is open and the tumor has been cut longitudinally, showing a frayed artery on the caudo-ventral area of the tumor (arrows).

Samples from the mass in the vagina, uterine body and horns, ovaries, liver, kidney, heart, and lung were collected, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, routinely processed and sectioned for microscopic examination and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Selected sections of the vaginal mass were stained with Van Kosa, orcein, and Masson’s trichrome, and processed by an avidin biotin conjugate (ABC) immunostaining method by using a commercial kit (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA), for smooth muscle actin, vimentin, desmin, S-100 protein, and cytokeratin.

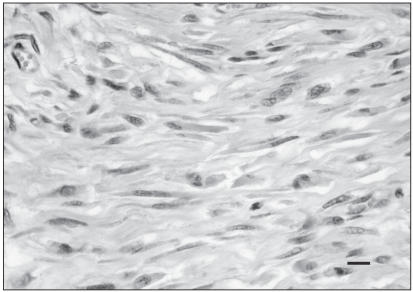

Histological examination of the tumor revealed densely packed spindle-shaped cells arranged in broadly woven fascicles and bundles (Figure 3). The cells were supported by a moderate fibrous stroma containing numerous capillaries. The neoplastic cells were large, moderately monomorphic, and had ill-defined cell borders. They had large quantities of eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm and a large, centrally placed, cigar-shaped vesicular nucleus (Figure 3). Severe focal hemorrhage was observed in the area corresponding grossly to the frayed artery, but no significant inflammatory reaction or necrosis was seen in this area. The mitotic rate was less than 1 mitosis per high power (magnification ×400) microscopic field. The cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells stained red with Masson’s trichrome stain. Immunohistochemical staining of the tumor revealed diffuse cytoplasmic staining with smooth muscle actin, vimentin, desmin, and S-100 protein antibodies, but the neoplastic cells did not react with cytokeratin antibodies. No histological alterations were observed in blood vessels within the neoplasm, except for the frayed blood vessel described grossly. This vessel showed ruptured edges with fibrin attached to its intima and to the torn edges. Diffuse hemorrhage was observed in the arterial wall close to the torn edges. No inflammatory infiltrate or calcium deposits were observed in the arterial wall and no alterations of the elastic fibers were evident. No histological changes were seen in the other organs examined.

Figure 3.

Leiomyoma of the uterine cervix of a goat. Hematoxylin and eosin. Bar = 10 μm.

Liver and kidney (cortex) samples were digested with nitric acid and analyzed for lead (Pb), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), molybdenum (Mo), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and cadmium (Cd) by inductively coupled argon plasma emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) (ARL, Accuris Model; Thermo Optek Corporation, Franklin, Massachusetts, USA). Accuracy of ICP was measured by analyzing standard reference materials (SRM), such as bovine liver (National Bureau of Standards and Technology, SRM 1577b) and lobster hepatopancreas (National Research Council of Canada TORT-2). Data were accepted if analyzed standard reference material values were within 2 standard deviations of the certified reference value. Metal concentrations were determined on a wet weight basis.

The liver and kidney metal concentrations were within acceptable ranges for goats. In particular, liver and kidney copper concentrations were 60.5 ppm and 3.1ppm, respectively.

Discussion

A presumptive diagnosis of leiomyoma was made, based on the histologic appearance of the neoplasia; the diagnosis was confirmed by the positive staining for smooth muscle alpha actin, vimentin, desmin, and S-100 protein antibodies, and by the positive staining in the Masson’s trichrome preparation. The cause of death of the animal was established to be hypovolemic shock as a consequence of massive hemorrhage, based on the clinical history and gross postmortem changes.

Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle neoplasias (1) that occur in a variety of organs, including the reproductive system (2). Although these tumors are the most common uterine neoplasias in humans (3) and are relatively frequent in other animal species (4,2), occurrence of leiomyomas in domestic ruminants is rare (5–8). Hemorrhage is a common feature of leiomyomas in humans (3) and other animal species (2); it has also been described in cases of leiomyosarcoma of goats (9,10). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, hemorrhage has not been described in cases of leiomyoma of goats (6,8).

Among other domestic animal species, uterine leiomyomas are regularly reported in dogs (2) and these tumors are also common in mares, in which hemorrhage has also been reported (17). Other regularly reported uterine tumors in the domestic species include uterine lymphosarcoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma, both of which are most commonly observed in cows (2), and endometrial adenocarcinoma in rabbits (4). However, uterine tumors are rarely reported in goats (8). Solitary leiomyoma of the cervix (8) and the body of the uterus (7) have been reported previously in 2 old goats. Another case of leiomyoma of the cervix associated with abdominal straining was reported in a goat (6). In the latter case, the tumor extended cranially and caudally into the uterus and vagina, respectively; the authors suggested that the straining was caused by the pressure of the mass on the pelvic inlet activating the pelvic reflex that occurs during parturition. In the present case, no straining or other clinical signs, except for the massive bleeding, were observed. This was probably due to the total intravaginal location of the neoplasm.

The microscopic appearance of this tumor was similar to that of the 2 cases of goat cervical leiomyomas previously described (6,8), with the exception that necrosis was not observed in the present case. Two patterns of necrosis have been characterized in human smooth muscle tumors to enhance differentiation between benign and malignant tumors. The 1st consists of neoplastic cells that gradually become increasingly hyaline with nuclear karyolysis and is designated “infarct-type” necrosis (12,13). Necrosis of this type is commonly observed in human uterine leiomyomas. The 2nd pattern is referred to as “coagulative tumor cell” necrosis; this occurs in most human uterine leiomyosarcomas, but rarely in leiomyomas. It is characterized by a sudden transition from viable neoplastic cells to necrotic cell debris (12).

Vulvar bleeding was reported in 3 cases of caprine genital leiomyosarcomas of a series of 7 goats with this neoplasm (10) and in another goat with leiomyosarcoma (9). Hemorrhage is usually a feature of malignant neoplasia and it is therefore not surprising that vulvar hemorrhage was observed in the described leiomyosarcoma cases (9,10). This case is a benign neoplasm in which necrosis was not observed and hemorrhage was seen only focally in the area where a large blood vessel was torn.

In humans, uterine hemorrhage due to leiomyomas are frequently related to pregnancy, delivery, and puerperium (14), although spontaneous hemorrhage of these neoplasms in non-pregnant women also occur. In the present study, no pre-existing histological lesions were observed in the ruptured blood vessel or in other vessels within the tumor, and no hemosiderosis was seen within the tumor. These findings suggest that the rupture of the vessel and the bleeding were possibly the consequence of an acute traumatic accident. It cannot be ruled out, however, that a pre-existing condition of the blood vessels within the tumor, not evident on histological examination, was present. Occasionally, acute arterial ruptures in ruminants follow abnormal mineralization or degenerative changes (arteriosclerosis) of vascular walls, but most ruptures are idiopathic. No degenerative changes were observed in any of the blood vessels of this goat, including the ruptured artery on the surface of the cervical neoplasia. Copper deficiency has been suggested to be responsible for vascular fragility leading to rupture in pigs and perhaps other animal species (15). However, the liver and kidney copper concentration in the present case was considered acceptable for goats.

A relationship between leiomyomas and steroidal receptors has been studied extensively in humans and dogs. In both species, it has been shown that smooth muscle tumors of the genital tract express steroid hormone receptors (16). Further, a genetic basis for leiomyomas has been established in the Eker rat, a strain in which spontaneous leiomyomas arise with a high frequency (17). By using this animal model system, it has been established that smooth muscle tumor development is dependent on steroid hormones and that sensitivity to estrogen is enhanced in leiomyomas (17). If this is also the case in goats, it is possible that estrogen was at least partly responsible for vessel fragility and bleeding in this case.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. E.J. Hurley and Ms. S. Kwiek for excellent technical assistance, Mr. A. Uzal for the photographs, and Mrs. S.J. Uzal and Dr. D. Read for editorial assistance. CVJ

Footnotes

Author contributions

Dr. Uzal performed the gross and microscopic studies and wrote the initial version of the manuscript. Dr. Puschner performed the heavy metal analysis, wrote the corresponding part of the manuscript, and provided input into the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hulland TJ. Tumors of the muscle. In: Moulton JE, editor. Tumors of Domestic Animals. Los Angeles: Univ California Pr; 1990. pp. 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy PC, Miller RB. The female genital system. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, editors. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 3. Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic Pr; 1993. pp. 249–470. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crum PC. The female genital tract. In: Cotran RS, Jumar V, Collins T, editors. Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. pp. 1035–1091. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene HSN. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine fundus in the rabbit. Ann NY Acad Sc. 1958;75:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb44573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson LJ, Sandison AT. Tumors of the female genitalia in cattle, sheep and pigs found in a British abattoir survey. J Comp Pathol. 1969;79:53–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(69)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockroft PD, McInnes EF. Abdominal straining in a goat with a leiomyoma of the cervix. Vet Rec. 1998;142:171. doi: 10.1136/vr.142.7.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damodaran S, Parthasarathy KR. Neoplasms of goats and sheep. Indian Vet J. 1972;49:649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadan RO, El Hassan AM. Leiomyoma in the cervix and hyperplastic ectopic mammary tissue in a goat. Aust Vet J. 1975;51:362. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb15949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan MJ. Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus in a goat. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:389–390. doi: 10.1177/030098588001700314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitney KM, Valentine BA, Schlafer DH. Caprine genital leiomyosarcoma. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:89–94. doi: 10.1354/vp.37-1-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandstetter LR, Doyle-Jones PS, Mckenzie HC. Persistent vaginal haemorrhage due to a uterine leiomyoma in a mare. Equine Vet Educ. 2005;17:156–158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell SW, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Problematic uterine smooth muscle neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 213 cases. Am J Surg Path. 1994;18:535–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart WR. Problematic uterine smooth muscle neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:252–255. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199702000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akrivis CH, Varras M, Bollou A, et al. Primary postpartum haemorrhage due to a large submucosal nonpedunculated uterine leiomyoma: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Obst Gynecol. 2003;30:156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson W. The cardiovascular system. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, editors. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 4. Vol. 3. San Diego: Academic Pr; 1993. pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millan Y, Gordon A, de los Monteros AE. Steroid receptors in canine and human female genital tract tumors with smooth muscle differentiation. J Comp Pathol. 2007;136:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker CL. Role of hormonal and reproductive factors in the etiology and treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:277–294. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]