Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Nephroureterectomy with excision of a cuff of bladder remains the standard for managing upper tract transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Increasing use of diagnostic upper tract endoscopy has underlined the importance of obtaining a pre-operative histological diagnosis in order to avoid under-treating high-grade or multifocal disease and over-treating low-grade disease, which could, in selected cases, be managed conservatively. We review nephroureterectomy at our institution over a 10-year period with particular reference to a pre-operative histological diagnosis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Nephroureterectomy was performed in 113 patients from February 1994 to February 2004. Of these cases, 58 were for upper tract TCC and 50 of these 58 had intravenous urography (IVU): 9 had only IVU, 28 had an additional CT scan, 5 had an additional ultrasonography and 8 had additional CT + ultrasonography for pre-operative work-up. Thirty-four of the 58 cases had retrograde pyelography. Nineteen (32.7%) of the 58 cases had a pre-operative ureteroscopy (URS) and biopsy; 14 of these had rigid URS for tumours in the lower (11) and middle (3) thirds of the ureter and 5 had flexible URS for pelvicalyceal tumours by an experienced endourologist. Thirty-one (53%) of the 58 tumours were within the pelvicalyceal system and 27 within the ureter (upper, 5; middle, 3; lower, 19). Forty-eight patients underwent a total nephroureterectomy: 40 had a two incision approach and 8 had an endoscopic resection of the lower ureter. Five of the 58 cases had a sub-total nephroureterectomy and 5 a laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with open excision of lower ureter.

RESULTS

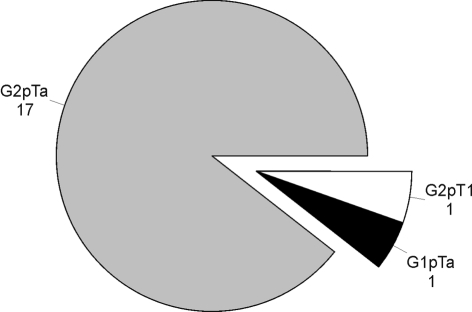

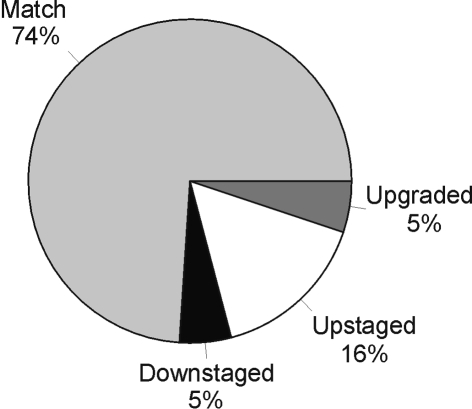

Nineteen (32.7%) of the 58 patients had a pre-operative histological diagnosis – 17 G2pTa, 1 G1pTa, and 1 G2pT1. Fourteen (74%) biopsies matched the final postoperative histology, but 1 was down-staged, 3 up-staged and 1 up-graded compared to the original histology. Five (12.8%) of 39 patients without pre-operative histology had no TCC in the final surgical specimen: 4 (10.25%) had benign pathology such as capillary haemangioma, urothelial cysts and reactive urothelial changes while one had renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

CONCLUSIONS

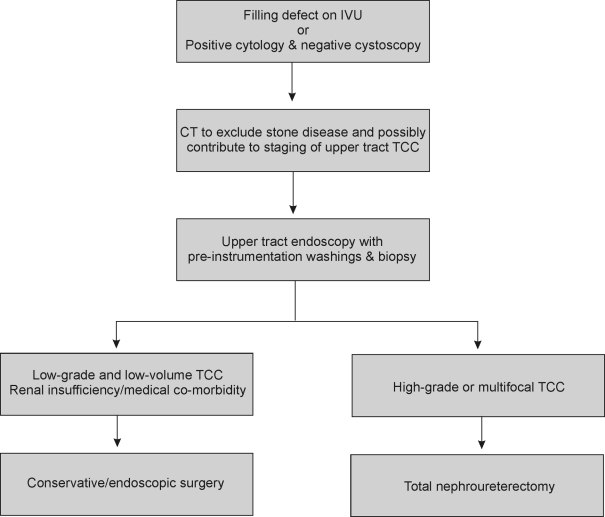

This study underlines the importance of obtaining a pre-operative histological diagnosis in cases with presumed upper tract TCC. Failure to do so can result in unnecessary ablative surgery for benign disease. Such an approach can also help identify multifocality and grade of disease so that treatment of upper tract TCC can be tailored more appropriately with ablative surgery for high-grade or multifocal disease and conservative (endoscopic) therapy for low-grade disease in selected cases. Patients with suspected TCC of the upper tract should be managed at centres where facilities for the comprehensive evaluation of such tumours exist.

Keywords: Transitional cell carcinoma, Ureter, Nephroureterectomy, Ureteroscopy, Histology

Nephroureterectomy with excision of bladder cuff has remained the standard of care in the management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).1 In recent years, laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with open excision of the lower ureter is replacing this procedure as the new gold standard.2–6 Whilst advances in flexible fibre-optic instruments and improvements in laser technology have made organsparing endoscopic management of low-grade TCC a realistic option in high-grade or multifocal disease, based on principles of surgical oncology, nephroureterectomy remains the preferred management option.

Until fairly recently, nephroureterectomy was performed based on pre-operative imaging such as intravenous urography (IVU), CT, retrograde pyelography (RGP) and abnormal selective urine cytology. With advances in instrument technology and the regular use of flexible ureteroscopy for diagnostic purposes, establishing a pre-operative histological diagnosis of upper tract TCC has become possible. Therefore, ablative surgery for upper tract TCC without histological confirmation can be avoided in most cases. Equally, a more aggressive approach with early ablative therapy can be recommended for patients identified as having high-grade or multifocal disease.

We reviewed nephroureterectomy at our institute over the last 10 years with particular reference to a pre-operative histological diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

A total of 113 nephroureterectomies were performed at our institute from February 1994 to February 2004 and 103 case notes were available for review. Of these, 58 were performed for upper tract TCC. The male:female ratio was 39:19 with a mean age of 75.5 years. Haematuria was the presenting symptom in all patients and in 75% it was painless. Twelve (20.7%) patients also had loin pain on the ipsilateral side. Six patients (10.3%) had a previous history of bladder tumour. Renal function was impaired in 33 of the 58 (43%) patients. Pre-operative urine cytology was available in 23 of the 58 (39.7%) cases: it was abnormal in 11 (47.8%), normal in 8 (34.8%) and atypical in 4 (17.4%). Pre-operative cytology was not available in all 58 patients. It was not part of the routine work-up earlier in the series and was then, and is still, used selectively. Four of 6 patients with a previous history of TCC of the bladder under regular surveillance had their upper tract TCC diagnosed on follow-up IVU, which was performed every 2 years in this patient group. Two of the 6 had their upper tract TCC detected on IVU triggered earlier than usual by recurrent haematuria.

Of the 58 patients, 50 had IVU as a part of their pre-opera-tive diagnostic work-up: 9 had IVU on its own, 28 had IVU + CT, 5 had IVU + ultrasonography and 8 had IVU + CT + ultrasonography. For the 8 patients who did not have an IVU, an ultrasound scan raised the possibility of an upper tract lesion and these patients went directly for a CT scan, rather than IVU. Of the 58 patients, 34 had retrograde pyelography (RGP) to aid a pre-operative diagnosis. Only 19 of these 58 cases (34.7%) had ureteroscopy (URS) and biopsy to establish a histological diagnosis. Fourteen had a semirigid ureteroscopy for tumours within the distal two-thirds of the ureter and five had a flexible ureteroscopy for tumours within the proximal ureter and kidney. Ureteroscopy was not performed in all cases. This study ran over a 10-year period; experience with ureteroscopy was limited in the early stages and we did not have a flexible ureteroscope. Our attitude towards ureteroscopy in this situation evolved as our experience grew and instrument technology improved.

Twenty-seven TCCs were on the right side and 31 on the left hand side. Thirty-one of the 58 primary tumours (53%) were in the pelvicalyceal system and 27 (47%) were in the ureter: 5 in the upper third, 3 in the middle third and 19 in the lower third of the ureter. Of the 31 cases with pelvicalyceal lesions and 5 cases with upper third ureteric lesions, only 5 patients (5/36) had a pre-operative biopsy. This was because most of the procedures were done at the time when upper tract endoscopy with the flexible URS was not standard practice due to the lack of availability of both the endoscope and surgical expertise.

Total nephroureterectomy was performed in 48 cases: 40 had a two-incision approach and 8 patients underwent endoscopic resection of the lower end of the ureter. Five patients underwent subtotal nephroureterectomy via a single flank incision: of these, 1 had an inoperable pelvic mass; the remaining 4 patients were frail with primary lesions in the pelvicalyceal system. In these patients, the distal ureter and the bladder cuff were not included in the specimen (hence termed subtotal nephroureterectomy), the aim being to reduce postoperative morbidity.

Five patients had a laparoscopic nephrectomy as a part of the nephroureterectomy with open excision of the lower ureter and bladder cuff.

Results

Of the 58 patients, 19 had a pre-operative histological diagnosis confirmed with ureteroscopic biopsy – 17 had G2pTa (89.4%), 1 had G1pTa and 1 had G2pT1 disease (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Pre-operative histology available on ureteroscopic biopsies.

Of 19 biopsies, 14 (74%) matched their final postoperative histology (Fig. 2), 1 was down-graded and down-staged, 3 were up-staged (from G2pTa to G2pT1 in two and to G2pT3 in one) and 1 up-graded (from G2pT1 to G3pT1). Of the 39 patients without a pre-operative histological diagnosis, five patients (12.8%) did not have any TCC on the final histology despite a radiological diagnosis of suspected upper tract TCC (Table 1). Four (10.25%) had benign pathology that would not warrant ablative surgery and one patient had renal cell carcinoma. The radiological abnormality in these cases was reported as a filling defect consistent with a TCC – none had this confirmed with ureteroscopy and biopsy. In the remaining 53 patients with histologically confirmed TCC, the commonest grade and stage was G2pTa (22/53; 41.5%) and the pattern ranged from G1pTa to G3pT4 (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Match between pre-operative and postoperative histology.

Table 1.

Types of benign/non-transitional cell carcinoma pathologies noted on final surgical specimen

| Type of benign pathology | Number |

|---|---|

| Capillary haemangioma | 1 |

| Benign urothelial cysts | 1 |

| Reactive urothelial changes | 2 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 |

Table 2.

Distribution of various grades and stages seen in definitive surgical specimens in 53 patients with upper tract transitional cell carcinoma

| Grade and stage of tumour | Number |

|---|---|

| G1pTa | 2 |

| G2pTa | 22 |

| G2pT1 | 14 |

| G2pT3 | 1 |

| G3pTa | 3 |

| G3pT1 | 3 |

| G3pT2/3 ± pTis | 7 |

| G3pT4 | 1 |

Postoperative follow-up consisted of out-patient check cystoscopy in all patients with upper tract TCC except those who had no tumour in the final specimen.

Follow-up upper tract imaging, namely IVU, was performed in 25 of 53 patients at 12-or 24-month intervals or in the event of recurrent haematuria.

Forty-three of the 53 patients had no evidence of vesical recurrence during follow-up. In all, 10 patients developed bladder recurrences – 8 within tumour-naive bladders and 2 with previous history of TCC of the bladder.

Intravesical cytotoxic chemotherapy or immunotherapy was administered to all 10 patients following TUR for recurrent superficial bladder tumours diagnosed during the postoperative follow-up period. One patient had a palliative cystectomy for intractable bleeding from post-radiation cystitis following radiotherapy for a G2pT2 bladder TCC in the past. There was no incidence of contralateral upper tract TCC recurrence in our series.

Thirty-seven (69.8%) of the 53 patients with proven TCC are alive at the time of writing this manuscript. Sixteen (30.2%) have died since their surgery, with a median survival of 7 years; of these 16 patients, only 5 died as a direct result of their TCC.

Discussion

Radical nephroureterectomy with excision of a cuff of the bladder wall is established as the standard treatment for transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract in the presence of a normal contralateral kidney.1 In all cases, it is vital to confirm the diagnosis prior to ablative surgery. Excretory urography and retrograde pyelography have been the conventional diagnostic tools used for this purpose with a CT scan reserved for further regional/nodal staging.7 There are conflicting reports in the literature concerning the diagnostic and staging value of CT7,8 as well as reports of its limitations9 in accurately staging the lower stages (Ta to T2).10 MRI is reported to have a higher positive predictive value and sensitivity than CT for diagnosis of TCC.11 Urine cytology on a voided sample has reduced sensitivity, as it is grade-dependent and likely to miss low-grade tumours.12 Cytology is expensive and the pick-up rate or yield is low. It is, therefore, often reserved for cases where all other tests are normal and as part of a follow-up protocol for all urothelial malignancies.

Ureterorenoscopy is recommended in the evaluation of upper tract haematuria of unknown aetiology.13 Ureterorenoscopy combined with exfoliated cell cytology and multiple biopsies has been found to be the most accurate (89%) way to confirm the diagnosis with up to a 78% match between preoperative biopsy and surgical pathological grade but not so accurate in predicting the stage, as the lamina propria is sampled in only 66% of biopsies.14,15 Although endoscopic biopsies are small, they are often sufficient to make a pathological diagnosis of the tumour grade.16 If there is a radiological abnormality, we recommend endoscopic evaluation and biopsy irrespective of the cytology result.

In a reported series,16 most biopsies (20/21, i.e. 95%) unfortunately lacked muscle, making it difficult to evaluate tumour stage, so vital to the management plan. However, pathological grading of the surgical specimens and biopsy sample correlated well with 90% accuracy17,18 and the biopsy grade reflected the pathological grade and stage;14 hence, the reliance on the pre-operative biopsy in management. For more accurate preoperative staging though, a CT/MRI scan in addition to ureteroscopic biopsy would seem to be more appropriate in view of the up-staging (3/19; 15.7%) and also down-staging (1/19; 5.2%) noted on final histology in our series.

Ureteroscopic biopsy has been found to be safe and accurate provided a sufficient sample has been obtained.17,18 Endoscopic brush cytology, although a more specific (94%) and sensitive (72%) sampling method than catheterised or irrigated urine for cytology (48%), has low diagnostic yield in dysplasia or carcinoma in situ as well as in low-grade lesions.19 Endoluminal ultrasonography is another instrument that has proved useful in evaluation of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the upper urinary tract.20 However, the sonographic or endoscopic appearances have not been reliable and one series reports up to 30% inaccuracy based solely on visual assessment of the upper tract tumour and recommends that biopsies are essential for accurate grading of upper tract TCC.21

With increasing experience of endoscopic techniques, namely safety and efficacy, it has become possible to enhance pre-operative diagnostic accuracy with pathological confirmation of precise tumour grade and stage.22 There has been no demonstrable added risk of local recurrence due to tumour seeding attributable to this procedure.23 There has, however, been a report of a single case of pyelovenous/lymphatic migration of renal TCC following flexible URS24 and a case report of renal pelvic explosion during ureteroscopic fulguration of upper tract TCC.25 Diagnostic ureterorenoscopy has no clinically apparent adverse effect on long-term or disease-specific survival of these patients with upper tract TCC.26

The aim of performing these investigations is to make a definitive diagnosis of TCC before proceeding with extirpative surgery and so avoid unnecessary removal of the kidney – a vital organ. In the present series, 4 patients (10.25%) had benign pathology in the final specimen and so had undergone an unnecessary nephroureterectomy.

Although there were none in our series, fibro-epithelial polyps are amongst many other causes of filling defects in the upper ureter (Table 3). They should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of upper tract TCC,27 and ruled out by ureteroscopy and biopsy to avoid unnecessary radical surgery.

Table 3.

Various causes of filling defects in the pelvicalyceal system seen on radiological imaging

|

Our study has clearly demonstrated the value, where possible, of obtaining a pre-operative histological diagnosis prior to ablative surgery for presumed TCC of the upper urinary tract. Some of our patients were offered ablative surgery on the basis of radiology with or without cytology alone and proved to have benign disease.

Close correlation between pre- and postoperative histology has been demonstrated15–18,21,28,29 and this supports the view that a biopsy taken endoscopically can accurately predict grade and stage of the tumour and influence decisions regarding conservative (nephron-sparing) or ablative surgery. The present series had significantly fewer higher stage and higher grade upper tract TCC (Table 2) compared to the series reported by Stewart et al.30 in which upper tract TCCs had a significantly higher grade and stage of the disease compared to the bladder lesions.

Distal ureterectomy/segmental resection has been an acceptable method of managing patients with TCC involving the distal/lower ureteric segment with the intent to avoid lifelong dialysis in patients with a solitary kidney or compromised renal function on the contralateral side. In these cases, it could be argued that pre-operative flexible ureteroscopy and CT are of paramount importance to rule out the possibility of multifocal/high-grade tumour in the proximal ureter as well as a high-stage tumour, because, in both circumstances, it may be more appropriate to employ a radical approach such as nephroureterectomy and life-long dialysis.

An algorithm, as outlined in Appendix 1, may help in the evaluation of patients with suspected upper tract tumours.The information obtained will help counsel the patient regarding best treatment option be this conservative (nephron sparing) or, ultimately, ablative therapy.

We feel that patients with presumed upper tract TCC should be managed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), which should include a uroradiologist, uro-oncologist, uropathologist and an endo-urologist. The endo-urologist would take the lead role in the comprehensive evaluation of these patients such that treatment can be tailored to the individual patient.

Conclusions

This study underlines the importance of obtaining a preoperative histological diagnosis in patients with presumed upper tract TCC. Failure to do so can result in unnecessary ablative surgery for benign disease. Such an approach can also help identify multifocality and grade of disease so that treatment of upper tract TCC can be tailored more appropriately with ablative surgery for high-grade or multifocal disease and conservative (endoscopic) therapy for low-grade disease in selected cases.

APPENDIX 1 Algorithm for management of suspected upper tract transitional cell carcinoma

References

- 1.Reservitz GB. A historic review of nephroureterectomy. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1967;125:853–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razdan S, Johannes J, Cox M, Bagley DH. Current practice patterns in urologic management of upper-tract transitional cell-carcinoma. J Endourol. 2005;19:366–71. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalhav AL, Portis AJ, McDougall EM, Patel M, Clayman RV. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy. A new standard for the surgical management of upper tract transitional cell cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2000;27:761–73. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rassweiler JJ, Schulze M, Marrero R, Frede T, Palou Redorta J, Bassi P. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: is it better than open surgery? Eur Urol. 2004;46:690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalhav AV, Dunn MD, Portis AJ, Elbahnasy AM, McDougall E, Clayman RV. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy for upper transitional cell cancer: the Washington University experience. J Urol. 2000;163:1100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill IS, Sung GT, Hobart MG, Savage SJ, Neraney AM, Schweizer DK, et al. Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract transitional cell carcinoma: Cleveland Clinic experience. J Urol. 2000;164:1513–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planz B, George R, Adam G, Jaske G, Planz K. Computed tomography for detection and staging of transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Eur Urol. 1995;27:146–50. doi: 10.1159/000475147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron RL, McClennan BL, Lee JK, Lawson TL. Computed tomography of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter. Radiology. 1982;144:125–30. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.1.7089243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scolieri MJ, Paik ML, Brown SL, Resnick MI. Limitations of computed tomography in the preoperative staging of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2000;56:930–4. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00800-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy JG, Honda H, Reznicek M, Williams RD. Computerised tomography for detection and staging of localized and pathologically defined upper tract urothelial tumours. J Urol. 1991;146:1500–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CL, Liu GC, Sheu RS, Huang CH. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography of transitional cell carcinoma of renal pelvis and ureter. Gaoxiong Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 1994;10:194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia TL. Cytologic diagnostic value of voided urine in 60 cases of primary transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1989;27:753–5. 782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yazaki T, Kamiyama Y, Tomomasa H, Shimizu H, Okano Y, Iiyama T, et al. Int J Urol. 1999;6:219–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.1999.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skolarikos A, Griffiths TR, Powell PH, Thomas DJ, Neal DE, Kelly JD. Cytologic analysis of ureteral washings is informative in patients with grade 2 upper tract TCC considering endoscopic treatment. Urology. 2003;61:146–50. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guarnizo E, Pavlovich CP, Seiba M, Carlson DL, Vaughan ED, Sosa RE., Jr Ureteroscopic biopsy of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: improved diagnostic accuracy and histopathological considerations using a multi-biopsy approach: J Urol. 2000;163:52–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoller ML, Gentle DL, McDonald MW, Reese JH, Tacker JR, Carroll PR, et al. Endoscopic management of upper tract urothelial tumours. Tech Urol. 1997;3:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiraishi K, Eguchi S, Mohri J, Kamiryo Y. Role of ureteroscopic biopsy in the management of upper urinary tract malignancy. Int J Urol. 2003;10:627–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daneshmand S, Quek ML, Huffman JL. Endoscopic management of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: long term experience. Cancer. 2003;98:55–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodd LG, Johnston WW, Robertson CN, Layfield LJ. Endoscopic brush cytology of the upper urinary tract. Evaluation of its efficacy and possible limitations in diagnosis. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:377–84. doi: 10.1159/000332528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu JB, Bagley DH, Conlin MJ, Merton DA, Alexander AA, Goldberg BB. Endoluminal sonographic evaluation of ureteral and renal pelvic neoplasms. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:515–21. doi: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.8.515. quiz 523–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Hakim A, Weiss GH, Lee BR, Smith AD. Correlation of ureteroscopic appearance with histologic grade of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 2004;63:647–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam JS, Gupta M. Ureteroscopic management of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:115–28. doi: 10.1016/S0094-0143(03)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulp DA, Bagley DH. Does flexible ureteropyeloscopy promote local recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma? J Endourol. 1994;8:111–3. doi: 10.1089/end.1994.8.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim DJ, Shattuck MC, Cook WA. Pyelovenous lymphatic migration of transitional cell carcinoma following flexible ureterorenoscopy. J Urol. 1993;149:109–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews PE, Segura JW. Renal pelvic explosion during conservative management of upper tract urothelial cancer. J Urol. 1991;146:407–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendin BN, Streem SB, Levin HS, Klein EA, Novick AC. Impact of diagnostic ureteroscopy on long-term survival in patients with upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1999;161:783–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams TR, Wagner BJ, Corse WR, Vestevich JC. Fibroepithelial polyps of the urinary tract. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:217–21. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keeley FX, Kulp DA, Bibbo M, NcCue PA, Bagley DH. Diagnostic accuracy of ureteroscopic biopsy in upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1997;157:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy DM, Zincke H, Furlow WL. Primary grade 1 transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter. J Urol. 1980;123:629–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart GD, Bariol SV, Grigor KM, Tolley DA, McNeill SA. A comparison of the pathology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and upper urinary tract. BJU Int. 2005;95:791–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]