Abstract

We describe the kinetic consequences of the mutation N217K in the M1 domain of the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) α subunit that causes a slow channel congenital myasthenic syndrome (SCCMS). We previously showed that receptors containing αN217K expressed in 293 HEK cells open in prolonged activation episodes strikingly similar to those observed at the SCCMS end plates. Here we use single channel kinetic analysis to show that the prolonged activation episodes result primarily from slowing of the rate of acetylcholine (ACh) dissociation from the binding site. Rate constants for channel opening and closing are also slowed but to much smaller extents. The rate constants derived from kinetic analysis also describe the concentration dependence of receptor activation, revealing a 20-fold shift in the EC50 to lower agonist concentrations for αN217K. The apparent affinity of ACh binding, measured by competition against the rate of 125I-α-bungarotoxin binding, is also enhanced 20-fold by αN217K. Both the slowing of ACh dissociation and enhanced apparent affinity are specific to the lysine substitution, as the glutamine and glutamate substitutions have no effect. Substituting lysine for the equivalent asparagine in the β, ε, or δ subunits does not affect the kinetics of receptor activation or apparent agonist affinity. The results show that a mutation in the amino-terminal portion of the M1 domain produces a localized perturbation that stabilizes agonist bound to the resting state of the AChR.

Keywords: single channel kinetics, acetylcholine binding site

introduction

The acetylcholine receptor (AChR)1 from vertebrate skeletal muscle is a pentamer of homologous subunits with compositions α2βγδ in fetal or α2βεδ in adult muscle (Mishina et al., 1986). Each subunit contains an amino-terminal extracellular domain of approximately 210 residues followed by four candidate transmembrane domains (M1-M4). The five subunits are packed pseudosymmetrically to form a cylindrical structure containing two acetylcholine binding sites coupled to a central ion channel. The binding sites are thought to lie approximately 30 Å above the plane of the membrane (Unwin, 1993; Valenzuela et al. 1994), formed by extracellular domain portions of αγ, αδ, or αε subunit pairs (Blount and Merlie, 1989, 1991; Sine, 1993), whereas the transmembrane domains are thought to be encompassed within the membrane where the M2 domain forms the cation-selective channel (Unwin, 1993, 1995). The essential function of the AChR is to transduce a local perturbation caused by binding of agonist into movement of the remote M2 domains that opens the channel.

To understand the essential function of the AChR, investigators have worked to establish structure-function relationships for the various structural domains. Thus it is clear that agonist binds to two sites in the extracellular domain, that the M2 domains from each subunit form the ion permeation pathway, and that binding triggers twisting of the M2 domains from the center to the perimeter of the channel to cause opening (Unwin, 1995). On the other hand, the contribution of the M1 domain is not as well understood as that of the M2 domain. In particular, the secondary structure of M1, its disposition relative to the membrane or the binding sites, and its contribution to AChR function are not established. M1 is unique among transmembrane domains in that it is poised in the linear sequence between binding site residues in the extracellular domain and the M2 channel lining. It is readily identified as a 26 residue hydrophobic segment flanked by the palindromic sequences PLYF . . . FYLP (Table I). Whether M1 is a β sheet or an α helix is not known, but in either configuration its length is more than adequate to span the membrane. The presence of a conserved proline (P221) in the middle of M1 suggests a discontinuous structure (Suchnya et al., 1993), perhaps dividing it into two types of structural and functional domains. Labeling studies with a hydrophobic reagent revealed accessible residues in the middle of M1 (C222, L223, F227, and L228), perhaps accessible through the lipid bilayer (Blanton and Cohen, 1994), whereas these same residues (C222 and L223) mutated to cysteine are not labeled by hydrophilic sulfhydryl reagents. On the other hand, several residues in the amino-terminal third of M1 (between P211 and P221) are accessible to hydrophilic sulfhydryl reagents when mutated to cysteine, and the pattern of accessibility suggests an unordered structure of this segment (Akabas and Karlin, 1995). Thus, approximately the carboxyl-terminal two-thirds of M1 may be folded in the membrane while the amino-terminal third may extend above it.

Table I.

Comparison of Sequences of M1 Domains

| Human subunits | ||

|---|---|---|

| α | PLYFIV N VIIPCLLFSFLTGLVFYLP | |

| β | PLFYLV N VIAPCILITLLAIFVFYLP | |

| δ | PLFYII N ILVPCVLISFMVNLVFYLP | |

| ɛ | PLFYVI N IIVPCVLISGLVLLAYFLP | |

| α subunits | ||

| human α3 | PLFYTI N LIIPCLLISFLTVLVFYLP | |

| human α4 | PLFYTI N LIIPCLLISCLTVLVFYLP | |

| human α7 | TLYYGL N LLIPCVLISALALLVFLLP | |

| rat α2 | PLFYTI N LIIPCLLISCLTVLVFYLP | |

| rat α3 | PLFYTI N LIIPCLLISFLTVLVFYLP | |

| rat α4 | PLFYTI N LIIPCLLISCLTVLVFYLP | |

| rat α6 | PMFYTI N LIIPCLFISFLTVLVFYLP | |

| rat α7 | TLYYGL N LLIPCVLISALALLVFLLP | |

| rat α9 | SSFYIV N LLIPCVLISFLAPLSFYLP | |

| mutant | K | |

| | | | | ||

| 211 217 236 |

Recent insights into structure-function relationships have come from mutations in human AChR that cause congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMS). In the cases described to date, the mutant residue is conserved across species and in some cases across all members of the superfamily, and pathogenicity can be traced to a change in a specific step in receptor activation (Ohno et al., 1995; Sine et al., 1995; Ohno et al., 1996). We recently described a mutation in the synaptic third of the M1 domain of the α subunit (αN217K) that causes a CMS (Engel et al., 1996). αN217 is conserved across all species and subtypes of α subunits and is present in the equivalent position in the β, ε, and δ subunits (Table I). When expressed in 293 HEK cells, receptors containing αN217K activate in prolonged episodes strikingly similar to those observed at the CMS end plates. Here we use single channel recording to examine the kinetics of activation of AChRs containing αN217K. We show that the prolonged activation episodes are due primarily to slowing of the rate of ACh dissociation from the binding site. The results reconfirm the importance of agonist binding affinity in governing the duration of the synaptic response and show that the M1 domain contributes to binding site affinity.

methods

Construction of Mutant AChR cDNAs and Expression in 293 HEK Cells

Mouse AChR subunit cDNAs were generously provided by Drs. John Merlie, Norman Davidson (α, β, and δ subunits; referenced in Sine, 1993), and Paul Gardner (ε subunit, Gardner, 1990) and were subcloned into the CMV-based expression vector pRBG4 (Lee et al. 1991) for expression in 293 HEK cells. Mutations were constructed either by bridging restriction sites with synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides or by overlap PCR. For the αN217K, αN217Q, and αN217E mutations a 31-bp oligonucleotide bridged from a HincII to a SapI site. For βN217K, a 43-bp oligonucleotide bridged from a HincII to a BbsI site. For εN217K, a 130-bp fragment harboring the mutation was constructed by overlap PCR and ligated between MspI and NheI sites. For δN217K, a 230-bp fragment harboring the mutation was constructed by overlap PCR and ligated between Bst1107I and KpnI sites. The presence of each mutation and the absence of unwanted mutations was confirmed by dideoxy sequencing. Human embryonic kidney fibroblast cells (293 HEK) were transfected with mutant or wild-type AChR subunit cDNAs using calcium phosphate precipitation as described (Bouzat et al., 1994).

Patch-clamp Recordings from AChRs Expressed in HEK Cells

Recordings were obtained in the cell-attached configuration (Hamill et al., 1981) at a membrane potential of −70 mV and a temperature of 22°C (Bouzat et al., 1994). Bath and pipette solutions contained (mM): KCl 142, NaCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.7, HEPES 10, pH 7.4. Single channel currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200A at a bandwidth of 50 kHz, digitized with a PCM adapter at 94 kHz (VR-10B; Instrutech Corp., Great Neck, NY), transferred to a Macintosh computer using the program Acquire (Instrutech Corp.), and detected by the half-amplitude threshold criterion using the program MacTac (Instrutech Corp.) at a final bandwidth of 9 kHz. Data acquisition typically commenced within 1 min of seal formation. Open and closed duration histograms were constructed using a logarithmic abscissa and square root ordinate (Sigworth and Sine, 1987). For analysis of currents recorded at limiting low ACh concentrations, the histograms were fitted by the sum of exponentials by maximum likelihood. The resulting time constants and relative areas were used to calculate the rate constants α2, β2, and k−2 in scheme SI (see results).

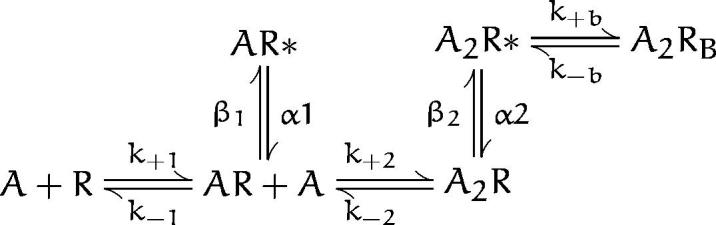

Scheme I.

Currents elicited by intermediate and high ACh concentrations were analyzed to obtain estimates of all the rate constants in schemes i and ii (see results). Clusters of events corresponding to a single channel were identified as a series of closely spaced openings preceded and followed by closings longer than a specified duration; this duration was taken as the point of intersection of the predominant closed time component in the histogram and the succeeding closed time component. A uniform filter bandwidth of 9 kHz and a dead time of 22 μs were imposed for all recordings. For each recording, kinetic homogeneity was determined by computing the mean open duration (τo) and open probability (Popen) of each cluster and plotting their distributions for visual inspection (Sine and Steinbach, 1987; Auerbach and Lingle, 1987). Typically the distributions contained a dominant, approximately Gaussian component, as well as minor contributions of clusters with very different properties. Clusters of events belonging to the dominant component were systematically selected for further analysis by accepting clusters with τo and Popen within two standard deviations of the mean of the major component. The selection process typically retained >90% of the original clusters for further analysis.

The resulting open and closed intervals, from single patches at several ACh concentrations, were transferred to an IBM RS6000 computer, and analyzed according to either scheme SI or ii using an interval-based maximum likelihood method that incorporated corrections for missed events (Qin et al., 1996). Briefly, the method computes the likelihood, or joint probability of obtaining the experimental series of open and closed dwell times given the kinetic scheme, and maximizes the likelihood by optimizing parameters in the scheme (Ball and Sansom, 1989). The likelihood was maximized using a forward-backward recursive procedure to calculate the likelihood function and its derivatives with respect to model parameters (Qin et al., 1997) and an optimizer that combined calculation of the approximate inverse Hessian matrix of second derivatives of the likelihood function and an exact line search with adaptive step sizes (Fletcher, 1981). After fitting, standard errors of the rate constants were determined from the curvature of the likelihood function at its maximum; these were obtained as the diagonal elements of the approximate inverse Hessian matrix generated by the optimizer. Standard errors calculated in this manner assume a quadratic form of the likelihood function near its maximum, and correspond to standard errors determined by the half-likelihood-interval method (Colquhoun and Sigworth, 1995).

Probability density functions of open and closed durations were calculated from the fitted rate constants and instrumentation dead time and superimposed on the experimental dwell time histograms as described by Qin et al. (1996). To check the final set of rate constants, open and closed intervals were simulated according to scheme SI, the fitted rate constants and dead time (Clay and DeFelice, 1983), binned into histograms and compared with the theoretical probability density functions.

For wild-type, αN217Q , and αN217E receptors, recordings included in the analysis were obtained at the following ACh concentrations (μM): 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, and 300. For the αN217K receptor, recordings for analysis were obtained at the following ACh concentrations (μM): 0.3, 1.0, 2, 3, 5, 10, 20, 30, 100, and 300. For each ACh concentration, the number of kinetically homogeneous clusters ranged from 17 to 62, and the corresponding numbers of events ranged from 1,400 to 4,000.

ACh Binding Measurements

3 d after transfection, intact HEK cells were harvested by gentle agitation in PBS plus 5 mM EDTA. The esterase inhibitor diisopropylphosphofluoridate (1 μM) was added to the PBS/EDTA solution, and the cells were incubated for 15 min. Cells were briefly centrifuged, resuspended in high potassium Ringer's solution (140 mM KCl, 5.4 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.7 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, 30 mg/liter BSA, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 10–11 mM NaOH), and divided into aliquots for measurements of ACh binding. Specified concentrations of ACh were added 30 min before addition of 125I-labeled α-bungarotoxin (5 nM), which was allowed to bind for 30 min to occupy approximately half of the surface receptors. The binding reaction was stopped by adding potassium Ringer's solution containing 300 μM d-tubocurarine, followed by filtration using a cell harvester (Brandel Inc.). Radioactivity retained by the glass fiber filters (GF-B, 1 μm cutoff; Whatman Inc., Clifton, NJ) was measured with a gamma counter. The initial rate of 125I-α-bungarotoxin binding was determined to yield fractional occupancy of sites by ACh (Sine and Taylor, 1979). Competition measurements were analyzed according to the Hill equation.

|

where Y is fractional occupancy by ACh and K ov is an overall dissociation constant.

results

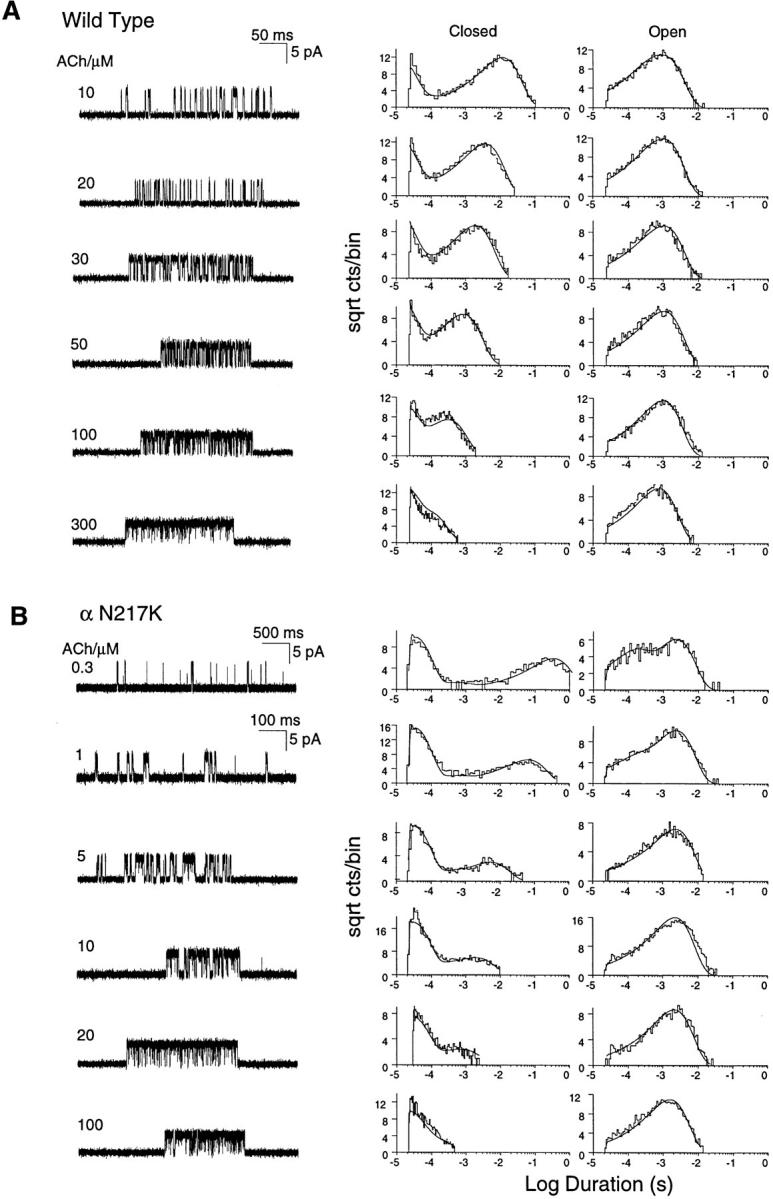

To investigate the kinetic basis of the prolonged activation episodes of the αN217K AChR, we recorded single channel currents from 293 HEK cells transfected with either wild-type or mutant α plus complementary β, ε, and δ subunit cDNAs. Currents were elicited by a range of desensitizing concentrations of ACh, as this allows identification of clusters of events due to a single AChR channel (Sakmann et al., 1980). For the αN217K AChR, openings appear in readily recognizable clusters at concentrations as low as 0.3 μM ACh, whereas for the wild type AChR, clustering requires concentrations of at least 3 μM. The channel traces show that closed intervals within clusters become more brief with increasing ACh concentrations and that they are more brief at a given concentration for the αN217K compared to the wild-type AChR (Fig. 1). Qualitatively, the briefer closed intervals observed with αN217K indicate a change in the rate of one or more of the following steps governing reopening of the channel: agonist association, agonist dissociation, or opening of the doubly occupied channel.

Figure 1.

Kinetics of activation of wild-type and αN217K AChRs. (A) Individual clusters of single channel currents recorded from HEK cells expressing mouse wild-type AChR (α2βεδ) at the indicated ACh concentrations. Currents are displayed at a bandwidth of 9 kHz, with channel openings as upward deflections (left column). The corresponding histograms of closed and open durations are shown with the results of the fit to scheme SI superimposed (center and right columns). (B) Individual clusters of single channel currents recorded from HEK cells expressing the mouse αN217K AChR at the indicated ACh concentrations (left column). The corresponding histograms of closed and open durations are shown with the results of the fit to scheme SI superimposed (center and right columns). The fitted rate constants are given in Table II.

To identify kinetic steps affected by αN217K, we analyzed the kinetics of channel opening and closing according to the following activation scheme:

where two agonists (A) bind to the receptor in the resting state (R) with association rates k +1 and k +2 and dissociate with rates k −1 and k −2. Receptors occupied by one agonist open with rate β1 and close with rate α1, while receptors occupied by two agonists open with rate β2 and close with rate α2. To account for channel block by high concentrations of ACh, we included the blocked state A2RB with the blocking and unblocking rate constants k +b and k −b. To estimate the set of rate constants, scheme SI was fit to the data by computing the likelihood of the experimental series of open and closed times given a set of trial rate constants and changing the rate constants to maximize the likelihood; the fitting analysis included dwell times obtained for the entire range of ACh concentrations. The advantage of fitting recordings obtained at multiple rather than single ACh concentrations is all the states in scheme SI are represented over a range of concentrations. In addition, for wild-type receptors, β2 was constrained to the value obtained from measurements at limiting low ACh concentrations described below. This constraint was necessary because the wild-type receptor opens very rapidly and is blocked at ACh concentrations similar to its intrinsic affinity (Table II), so closings due to gating and blocking become indistinguishable at high ACh concentrations. The simultaneous fit to all of the data, shown as smooth curves superimposed on the open and closed duration histograms, reasonably describes the kinetics of wild-type and αN217K AChRs (Fig. 1).

Table II.

Kinetic Parameters for AChRs Containing Wild-type or Mutant α Subunits

| k − | k + | K/μM | β1 | α1 | Θ1 | β2 | α2 | Θ2 | k +block | k −block | K B/mM | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| scheme SI | 21,900 | 129 | 170 | 216 | 3,320 | 6.5E-2 | 48,900 | 1,660 | 29.5 | 9.67 | 74,100 | 7.67 | ||||||||||||

| (±438) | (±2) | (±21) | (±350) | (±3,960) | (±21) | (±0.71) | (±3,370) | |||||||||||||||||

| scheme SII | 21,900 | 129 | 170 | 216 | 3,320 | 6.5E-2 | 48,900 | 1,660 | 29.5 | 9.67 | 74,100 | 7.67 | ||||||||||||

| (±3,140) | (±23) | (±21) | (±220) | (±3,960) | (±157) | (±0.67) | (±3,120) | |||||||||||||||||

| αN217K | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| scheme SI | 1,890 | 116 | 16.2 | 72.4 | 7,640 | 9.5E-3 | 31,400 | 873 | 35.9 | 10.7 | 74,530 | 7.0 | ||||||||||||

| (±35) | (±1.7) | (±2.8) | (±390) | (±350) | (±9.8) | (±1.1) | (±4,740) | |||||||||||||||||

| scheme SII | 1,838 | 115 | 16.0 | 70.6 | 7,700 | 9.2E-3 | 28,500 | 816 | 34.8 | 13.2 | 78,800 | 6.0 | ||||||||||||

| (±52) | (±1.6) | (±2.5) | (±360) | (±4,700) | (±32) | (±0.8) | (±4,760) | |||||||||||||||||

| αN217Q | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| scheme SI | 26,300 | 128 | 205 | 106 | 7,370 | 1.4E-2 | 61,700 | 2,300 | 27 | 8.8 | 57,700 | 6.6 | ||||||||||||

| (±610) | (±2.3) | (±13.4) | (±910) | (±3,100) | (±36) | (±0.54) | (±2,620) | |||||||||||||||||

| scheme SII | 26,300 | 127 | 207 | 107 | 7,380 | 1.4E-2 | 61,700 | 2330 | 27 | 8.8 | 57,700 | 6.6 | ||||||||||||

| (±1130) | (±2.2) | (±9.4) | (±700) | (±3100) | (±250) | (±0.6) | (±5,940) | |||||||||||||||||

| αN217E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| scheme SI | 25,600 | 77.9 | 328 | 91.6 | 4,560 | 2.0E-2 | 55,600 | 1,507 | 37 | 14.0 | 74,000 | 5.3 | ||||||||||||

| (±550) | (±1.3) | (±9.0) | (±570) | (±930) | (±20) | (±0.6) | (±1,730) | |||||||||||||||||

| scheme SII | 23,300 | 72.3 | 320 | 96.9 | 457 | 2.1E-1 | 55,600 | 1,770 | 31 | 13.9 | 76,400 | 5.5 | ||||||||||||

| (±580) | (±1.2) | (±8.0) | (±19) | (±930) | (±140) | (±0.7) | (±5,990) |

Rate constants are as defined in schemes i and ii (left column, see text), in units of μM−1 s−1 for association rate constants, and s−1 for all others. Values are results of a global fit of each scheme to data obtained over a range of ACh concentrations, with standard errors in parenthesis (see methods). Channel open equilibrium constants, Θ, are ratios of the corresponding opening to closing rate constants, β/α. Association and dissociation rate constants are presented on a per site basis because of the constraint of equivalent binding sites (see text). In all but one case, the fitting was carried out with the value of β2 fixed to that obtained from analysis of data obtained at low ACh concentrations (Table III); the exception was the fit of scheme SI to the αN217K data where the value of β2 from the global fit was essentially the same as that obtained at low ACh concentrations.

Focusing on the kinetic steps governing closed durations, we see that the rate of ACh dissociation is greatly slowed by αN217K (Table II). ACh dissociates from the wild-type receptor at a rate similar to the rate of channel opening, predicting approximately two openings per activation episode after brief exposure to agonist. By contrast, ACh dissociates from the αN217K AChR 10- to 20-fold more slowly, allowing greater than ten openings per activation episode. The initial fitting analysis allowed dissociation rate constants for the two binding sites to be free parameters, but the fit was not significantly better than with the constraint of equal dissociation rate constants for the two sites. For both the constrained and unconstrained analyses, the two binding sites showed essentially equivalent dissociation rate constants for both αN217K and wild-type receptors. Unequal dissociation rate constants have been described for Torpedo (Sine et al., 1990) and fetal mouse (Zhang et al., 1995) receptors; features of those data indicating nonequivalent dissociation rate constants were biexponential distributions of the major concentration-dependent closings at intermediate but not high ACh concentrations. In the present study, αN217K and wild-type receptors show monoexponential distributions of the major concentration-dependent closings over the range of ACh concentrations examined (Fig. 1); Akk and Auerbach (1996) also observed equal dissociation rate constants for adult mouse receptors. The overall data suggest that differences in the agonist dissociation rate constants for the two sites depend on species and on whether the α subunit pairs with the γ, δ, or ε subunit.

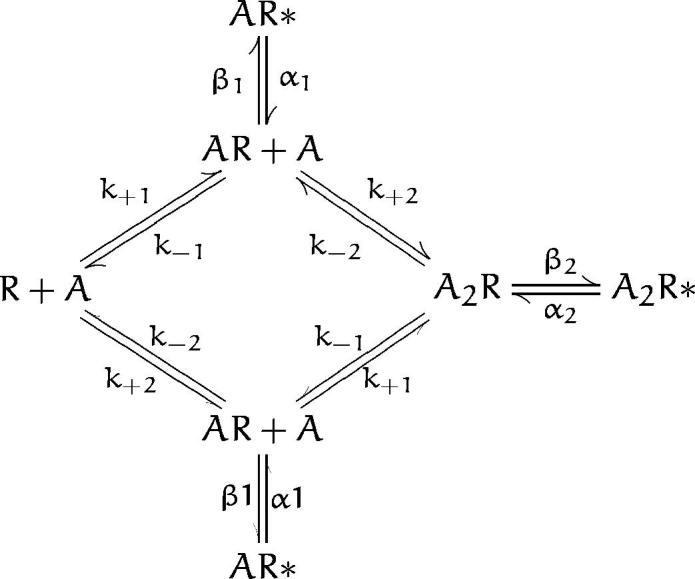

We further examined equivalence of the dissociation rate constants by expanding scheme SI to allow independent binding of ACh to each site.

Scheme SII predicts a fourth closed time component, which can be distinguished if the two binding sites are neither equivalent nor widely different in their ACh affinities. Fitting scheme SII to the data, however, revealed equivalent dissociation rate constants for each binding site (Table II).

Scheme II.

Association rate constants are not affected by αN217K (Table II) and are close to the diffusion limited values reported previously from single channel kinetic analysis of Torpedo and adult mouse AChRs (Sine et al., 1990; Akk and Auerbach, 1996). As observed for the agonist dissociation rate constants, association rate constants are equivalent at each binding site for both wild-type and αN217K AChRs; allowing the association rate constants for the two sites to be free parameters gave no better fit than when they were constrained to be equal. Several features of the closed duration histograms indicate that αN217K slows ACh dissociation without a change in association: the long duration component of closed times is roughly equally dependent on ACh concentration for both receptor types, but the mean of this component is always more brief at a given concentration for αN217K than for wild type. Thus the overall effect of αN217K on affinity of the resting state of the receptor is a 10-fold decrease in the dissociation constant for ACh binding.

The rate of opening of the doubly occupied AChR, β2, though very fast for both mutant and wild type, is slowed by ∼50% by αN217K (Table II). The reduced β2 leads to a longer mean duration of the doubly occupied closed receptor, approximately (β2 + k −2)−1, which is seen in the closed duration histograms as an increase in the time constant of the major component of brief closings (Fig. 1). For the wild-type receptor, β2 was determined from analysis of currents obtained at limiting low ACh concentrations, so the results of the global fit demonstrate its consistency across a range of concentrations. For the αN217K receptor, the slower rate of ACh dissociation, combined with the slower rate of channel opening, allows β2 to be estimated even at high ACh concentrations. Although β2 is slowed by αN217K, opening is still rapid enough to elicit multiple reopenings per activation episode, as the other pathway away from the doubly occupied closed state, agonist dissociation, is slowed even more.

The life time of the doubly occupied open channel is increased about twofold by αN217K, owing to slowing of the closing rate α2 (Table II). A second class of briefer openings is detected at the lowest but not at the highest ACh concentrations, and is therefore ascribed to opening of singly occupied receptors. Owing to the predominance of the doubly occupied open channel during synaptic activity, the slower closing rate would double the duration of an activation episode, compounding the effect of the increase in the number of openings per episode.

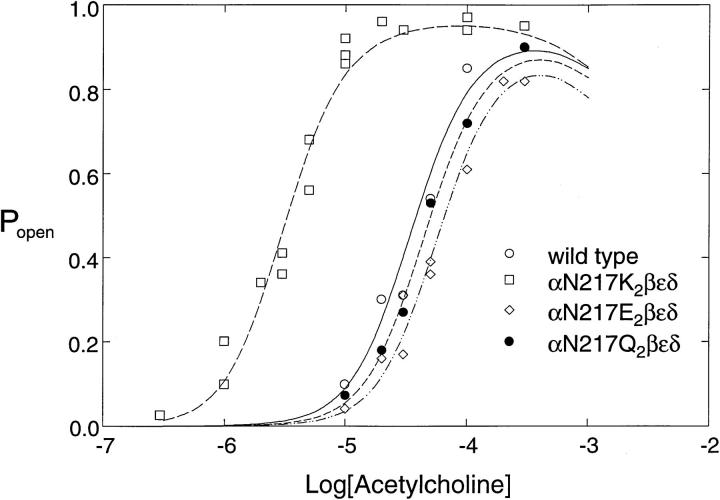

To confirm the rate constant estimates and to illustrate the overall consequences of αN217K, we determined the mean open probability within clusters at each concentration of ACh and compared it with the dose-response relationship calculated from the kinetically determined rate constants. The calculated dose-response curves superimpose upon the Popen measurements, supporting the rate constant estimates and revealing a 20-fold decrease in the EC50 for activation of the αN217K AChR (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Agonist concentration dependence of the channel open probability. For receptors containing the indicated α subunits, the mean fraction of time the channel is open during a cluster (Popen) was determined at the indicated concentrations of ACh. The probability of being in the A2R* open state in scheme SI was calculated from the kinetically determined rate constants given in Table II and superimposed on the Popen measurements.

Structural Basis of Kinetic Effect of αN217K

The preceding results establish that replacing asparagine with lysine at α217 slows the rate of agonist dissociation from the binding site. To gain insight into the structural basis of this effect, we made the glutamine and glutamate mutations at position 217 of the α subunit. We again recorded single channel currents over a range of desensitizing concentrations of ACh and analyzed the kinetics using schemes i and ii. The analysis reveals virtually indistinguishable sets of activation rate constants for αN217Q and wild-type receptors, showing that introducing a larger side chain alone is not responsible for the kinetic effect of αN217K (Table II). Introducing the negatively charged glutamate with αN217E also produces activation rate constants similar to those of wild type; the association rate constants are slowed with αN217E, leading to somewhat lower agonist affinity of each binding site (Table II). The dose-response relationship calculated from the kinetic parameters reasonably describes the measured Popen values, confirming that αN217Q and αN217E cause little or no change in activation properties of the receptor (Fig. 2). Thus introducing a negatively charged or an enlarged side chain at position 217 of the α subunit fails to slow the rate of agonist dissociation, suggesting that the structural basis of αN217K is introduction of a positive charge.

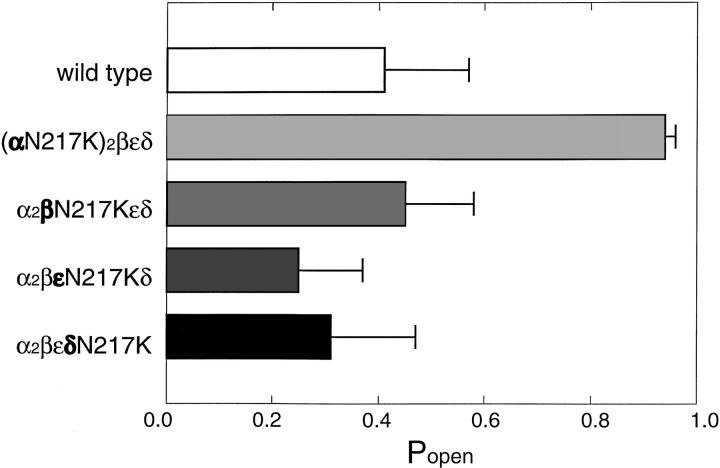

N217 is conserved not only across α subunits of all species, but also across the β, ε, and δ subunits (Table I). To determine whether the effect of the αN217K mutation is specific to the α subunit, and is therefore localized, we mutated the equivalent asparagine in the β, ε, and δ subunits. We recorded single channel currents elicited by 30 μM ACh and determined the mean open probability within clusters of openings. We chose a concentration of 30 μM because it is close to the EC50 for the wild-type receptor and therefore should be sensitive to changes in activation parameters (see Fig. 2). The measured open probabilities for receptors containing either βN217K, εN217K, or δN217K are within the range obtained for wild type, and are clearly lower than obtained for αN217K (Fig. 3). Thus slowing of ACh dissociation by the N217K mutation is specific to the α subunit, indicating a local rather than a global perturbation.

Figure 3.

Subunit specificity of the N217K mutation. The mean probability of channel opening (Popen) within a cluster was determined at the intermediate concentration of 30 μM ACh for receptors with the indicated mutant subunits (in bold type) replacing the corresponding wild-type subunit. The Popen values displayed were obtained from the following numbers of events and clusters: wild type, 2,464 events, 17 clusters; αN217K, 702 events, 25 clusters; βN217K, 4,170 events, 47 clusters; εN217K, 5,162 events, 47 clusters; δN217K, 3,924 events, 51 clusters.

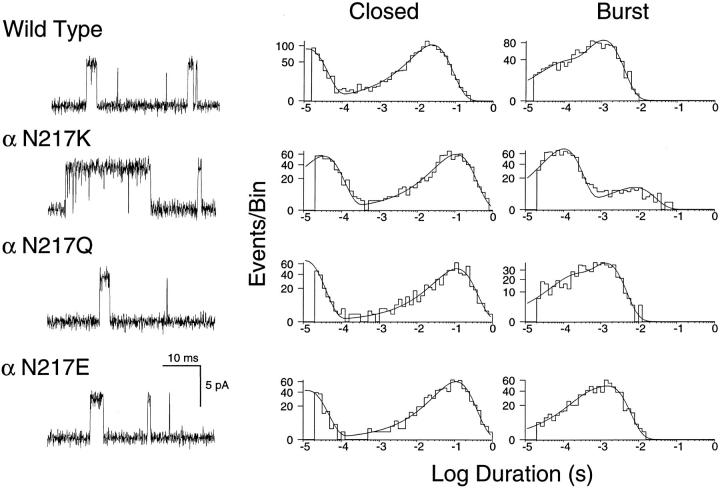

Kinetic Parameters Obtained at Low Concentrations of ACh

We also estimated the parameters α2, β2, and k −2 from currents elicited by limiting low concentrations of ACh. Estimating these three rate constants relies on choosing a concentration of ACh low enough so reopening after agonist dissociation is very slow. Thus we used ACh at concentrations of 1 μM for wild type, αN217Q , and αN217E and 50 nM for αN217K; these concentrations elicit threshold responses as shown by the dose-response measurements (Fig. 2). The traces obtained at low ACh concentrations show that wild-type, αN217Q , and αN217E receptors open one or two times per activation episode, whereas αN217K receptors open many times per episode (Fig. 4). For all four receptor types, closed duration histograms are described as the sum of two exponentials, with a long duration component due to periods between activation episodes elicited by different channels and a brief component due to transient interruptions of episodes due to a single channel. The corresponding burst duration histograms are described as the sum of two exponentials, with the long duration component due to receptors with two bound agonists and the brief component to receptors with a single bound agonist. Qualitatively, the presence of αN217K prolongs the activation episode by increasing the number of openings per burst.

Figure 4.

Analysis of currents elicited by low concentrations of ACh for receptors containing the indicated α subunits. Currents elicited by 1 μM (wild type), 50 nM (αN217K ), 1 μM (αN217Q ), and 1 μM (αN217E ) ACh are shown filtered at 10 kHz (left column). The corresponding closed and burst duration histograms are shown fitted by the sum of exponentials (center and right columns). Bursts are defined as a series of closely spaced events preceded and followed by closed intervals greater than a specified duration; this duration was taken as the point of intersection of the brief and long closed time components. Fitted parameters for the closed duration histograms are: wild type, τfast = 10.3 μs, afast = 0.52, τslow = 24.5 ms, total detected events, 1,510; αN217K: τfast = 30.8 μs, afast = 0.493, τslow = 106 ms, total detected events, 1,240; αN217Q: τfast = 13.8 μs, afast = 0.44, τslow = 113 ms, total detected events, 702; αN217E: τfast = 14.6 μs, afast = 0.334, τslow = 110 ms, total detected events, 796. Fitted parameters for the burst duration histograms are: wild type: τ0 = 89.4 μs, a0 = 0.209, τburst = 1.13 ms, total number of bursts, 1,195; αN217K: τ0 = 100 μs, a0 = 0.883, τburst = 8.04 ms, total number of bursts, 793; αN217Q: τ0 = 130 μs, a0 = 0.251, τburst = 1.32 ms, total number of bursts, 584; αN217E: τ0 = 360 μs, a0 = 0.218, τburst = 1.72 ms, total number of bursts, 700.

The measured parameters obtained at low agonist concentrations are related to steps in scheme SI as follows. The mean duration of brief closings equals (β2 + k −2)−1, and the number of brief closings per burst of long duration openings equals β2/k −2. Omitting the negligible contribution of brief closings in A2R, the mean burst duration equals (1 + β2/k −2)/α2. Estimates of α2 and k −2 obtained from these relationships are presented in Table III; they agree closely with the estimates obtained from the global kinetic analysis (Table II). The estimate of β2 obtained from low ACh concentrations was used as a fixed parameter in the global fitting analysis to constrain the range of parameters for receptors with low affinity and rapid rates of opening (Fig. 1 and Table II); this consistency across a wide range of ACh concentrations supports the accuracy of β2 for these receptors. For the αN217K AChR, essentially identical estimates of β2 were obtained independently from the low concentration and global analyses. Thus the parameters estimated at low ACh concentrations confirm that αN217K primarily slows the rate of agonist dissociation and that the kinetic effect is due to the positively charged lysine.

Table III.

Kinetic Parameters from Measurements at Low ACh Concentrations

| Number of patches | β2 (s−1) | k −2(s−1) | α2(s−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 6 | 48,950 ± 3,960 | 37,450 ± 1,930 | 2,100 ± 390 | ||||

| αN217K | 3 | 28,250 ± 4,700 | 4,728 ± 660 | 790 ± 130 | ||||

| αN217Q | 2 | 61,680 ± 3,100 | 34,610 ± 2,140 | 2,250 ± 80 | ||||

| αN217E | 2 | 55,620 ± 930 | 37,910 ± 2,780 | 1,640 ± 330 |

Note that k−2 is an overall rate constant, and should be divided by 2 for comparison with the per site values of k − in Table II.

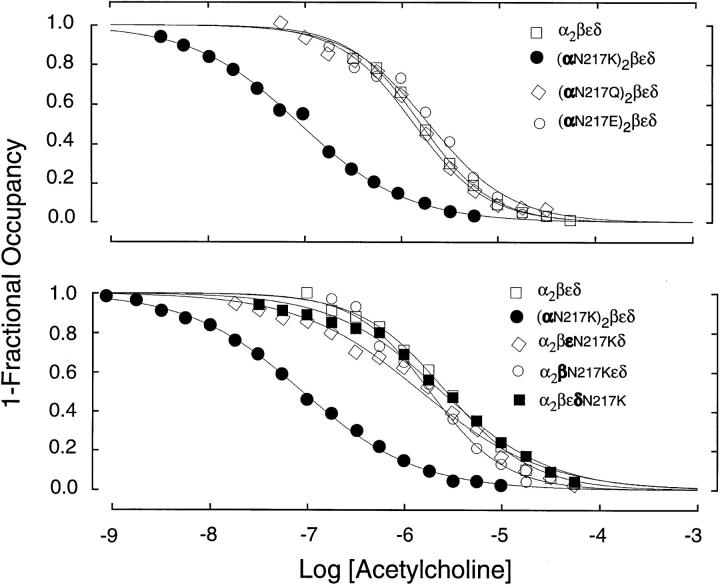

Measurements of Equilibrium Binding of ACh

We further examined the consequences of αN217K by measuring equilibrium binding of ACh by competition against the initial rate of 125I-α-bungarotoxin binding (Sine and Taylor, 1979). The wild-type AChR binds ACh with micromolar apparent affinity, whereas the αN217K AChR binds 20-fold more tightly (Fig. 5 A). Receptors containing either αN217Q or αN217E bind with affinities similar to wild type, as observed for their gating kinetics, confirming that the effect of αN217K is due to the presence of the positively charged lysine. Similarly, substitution of βN217K, εN217K, or δN217K for the corresponding wild-type subunit does not affect the apparent affinity for ACh, again confirming that the consequences of the N217K mutation are specific to the α subunit (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

Equilibrium binding of acetylcholine to receptors containing mutant and wild type subunits. (top) ACh binding was measured by competition against the initial rate of α-bungarotoxin binding (see methods) to receptors containing the indicated α subunits and complementary wild-type subunits. The curves are fits to the Hill equation with the following parameters: wild type, K equil = 1.6 μM, nH = 1.2; αN217K, K equil = 0.089 μM, nH = 0.8; αN217Q, K equil = 1.4 μM, nH = 1.1; αN217E, K equil = 2.0 μM, nH = 1.0. (bottom) Comparison of ACh binding to receptors containing the indicated mutant subunits and complementary wild-type subunits. The curves are fits to the Hill equation with the following parameters: wild type, K equil = 2.7 μM, nH = 1.0; αN217K, K equil = 0.089 μM, nH = 0.7; βN217K, K equil = 1.9 μM, nH = 1.1; εN217K, K equil = 1.5 μM, nH = 0.7; δN217K, K equil = 2.5 μM, nH = 0.8.

Binding of ACh at equilibrium is determined by contributions of the resting, open channel, and desensitized states of the receptor, each of which binds agonist with different affinity (for review see Changeux, 1990). While the increased affinity of the resting state contributes to the increase in equilibrium binding affinity of the αN217K receptor, changes in ACh affinity for the desensitized state or the allosteric constant governing the distribution of resting and desensitized states may also contribute. Our preliminary experiments indicate that αN217K does not affect the affinity of the desensitized state for ACh. Assuming a wild-type value of 40 nM for the affinity of the desensitized state (Sine et al., 1995), we computed the allosteric constant for desensitization using our measured parameters for activation (Table II). The results indicate a marked increase in the allosteric constant for desensitization from a wild-type value of 4 × 10−4 to 0.5 for αN217K.

discussion

We previously showed that αN217K causes a slow channel congenital myasthenic syndrome by prolonging the elementary activation episode elicited by ACh (Engel et al., 1996). Here we trace the kinetic defect to slowing of the rate of ACh dissociation from the binding site; prolonged occupancy by ACh allows the channel to open repeatedly before it can dissociate. Rate constants for channel opening and closing are also slowed but to much smaller extents. The kinetic fingerprint of αN217K is strikingly similar to that of our previously described SCCMS mutation αG153S, which is near residues in the extracellular domain that contribute to the binding site (Sine et al., 1995). The present results are surprising because αN217K is in the M1 transmembrane domain, whereas its primary effect is at the binding site, some 30 Å above the plane of the membrane (Unwin, 1993; Valenzuela et al. 1994). The kinetic effect of αN217K results from introduction of the positively charged lysine side chain and is not observed when lysine is introduced into the corresponding positions of the β, ε, or δ subunits. Thus slowing of agonist dissociation is not due to a global perturbation but rather to a local perturbation of the linkage between the M1 domain of the α subunit and the binding site. The results have implications for structure-function relationships of AChR and for how agonist binding affinity affects the time course of the synaptic response.

Present understanding of the topology of the M1 domain points to an allosteric rather than a direct effect of αN217K in slowing agonist dissociation. The available data indicate that approximately the carboxyl-terminal two-thirds of M1 may be folded in the membrane while the amino-terminal third may extend above it. Thus αN217 appears to lie just outside the membrane, where it is accessible to hydrophilic sulfhydryl reagents when mutated to cysteine (Akabas and Karlin, 1995). Exposure of residue 217 to aqueous solution would render a lysine side chain at this position positively charged at physiological pH. αN217 is also four residues amino-terminal to the conserved P221, which borders a stretch of four residues accessible to a hydrophobic labeling agent (Blanton and Cohen, 1994). If P221 is the most amino-terminal residue of M1 embedded in the membrane, the intervening four residues are not long enough to extend N217 30 Å to the binding site. Thus αN217 likely comprises part of the inner wall of extracellular vestibule and contributes to the linkage between the channel gating apparatus and the binding site.

Our findings show that the perturbation caused by αN217K propagates to the binding pocket to enhance the fit of ACh for the resting state of the receptor. Although it is clear that the binding site and channel gate are functionally coupled to produce rapid and efficient gating, the results presented here are the first to show spread of a perturbation in a transmembrane domain to the binding sites in the extracellular domain. The results suggest the presence of a structure that physically links the binding site and channel gating apparatus. Because the perturbation is due to the positively charged lysine side chain, in the wild-type receptor αN217 may serve as a hydrogen bond acceptor for a positively charged donor.

The findings reconfirm the importance of ACh binding affinity in governing the time course of the synaptic response (Sine et al., 1995). Magleby and Stevens (1972) showed that the decay of the end plate current is governed by properties intrinsic to the post synaptic AChR. The time constant for decay approximately equals the mean channel open time multiplied by the number of openings per activation episode, or (1/α2)(1 + β2/k −2). At the normal synapse, β2 is very fast to provide fast onset of the response, but k −2 is similarly fast to rapidly terminate the response ( Jackson, 1989). By contrast, synapses harboring the αN217K receptor show a prolonged end plate current primarily because the number of openings per activation episode is increased due to slowing of k −2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants to S.M. Sine (NS31744), A. Auerbach (NS23513), and A.G. Engel (NS6277).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; CMS, congenital myasthenic syndromes.

references

- Akabas M, Karlin A. Identification of acetylcholine receptor channel-lining residues in the M1 segment of the α-subunit. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12496–12500. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Auerbach A. Inorganic monovalent cations compete with agonists for the transmitter binding site of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biophys J. 1996;70:2652–2658. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79834-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A, Lingle C. Activation of the primary kinetic modes of large- and small-conductance cholinergic ion channels in Xenopus myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;393:437–466. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball FG, Sansom MSP. Ion channel gating mechanisms: model identification and parameter estimation from single channel recordings. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1989;236:385–416. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1989.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton M, Cohen J. Identifying the lipid-protein interface of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: secondary structure implications. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2859–2872. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Merlie JP. Molecular basis of the two nonequivalent ligand binding sites of the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1989;3:349–357. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Merlie JP. Characterization of an adult muscle acetylcholine receptor subunit by expression in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14692–14696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzat C, Bren N, Sine SM. Structural basis of the different gating kinetics of fetal and adult acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 1994;13:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP. Functional architecture and dynamics of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: an allosteric ligand gated channel. Fida Research Foundation Neuroscience Award Lectures (New York) 1990;4:21–168. [Google Scholar]

- Clay J, DeFelice L. Relationship between membrane excitability and single channel open-close kinetics. Biophys J. 1983;42:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, D., and F.J. Sigworth. 1995. Fitting and statistical analysis of single channel records. In Single-Channel Recording, 2nd edition. B. Sakmann and E. Neher, editors. Plenum Press, New York. 483–587.

- Engel A, Ohno K, Milone M, Wang H, Nakano S, Bouzat C, Pruitt J, Hutchinson D, Brengman J, Bren N, et al. New mutations in acetylcholine receptor subunit genes reveal heterogeneity in the slow channel myasthenic syndrome. Hum Mol Gen. 1996;5:1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. 1981. Practical methods of optimization. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, UK.

- Gardner P. Nucleotide sequence of the ε-subunit of the mouse muscle nicotinic receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6714. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch clamp technique for high resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflüg Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. Perfection of a synaptic receptor: kinetics and energetics of the acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2199–2203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BS, Gunn RB, Kopito RR. Functional differences among nonerythroid anion exchangers expressed in a transfected human cell line. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11448–11454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby KL, Stevens CF. A quantitative description of end-plate currents. J Physiol (Lond) 1972;223:173–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishina M, Takai T, Imoto K, Noda M, Takahashi T, Numa S, Methfessel C, Sakmann B. Molecular distinction between fetal and adult forms of muscle acetylcholine receptor. Nature (Lond) 1986;321:406–411. doi: 10.1038/321406a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Hutchinson DO, Milone M, Brengman JM, Bouzat C, Sine SM, Engel AG. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by prolonged acetylcholine receptor channel openings due to a mutation in the M2 domain of the ε subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:758–762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Wang H-L, Milone M, Bren N, Brengman JM, Nakano S, Quiram P, Pruitt JN, Sine SM, Engel EG. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by decreased agonist binding affinity due to a mutation in the acetylcholine receptor ε subunit. Neuron. 1996;17:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Auerbach A, Sachs F. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch clamp data containing missed events. Biophys J. 1996;70:264–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Auerbach A, Sachs F. Maximum likelihood estimation of aggregated Markov processes. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1997;264:375–383. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, Patlak J, Neher E. Single acetylcholine-activated channels show burst-kinetics in the presence of desensitizing concentrations of agonist. Nature (Lond) 1980;286:71–73. doi: 10.1038/286071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigworth F, Sine SM. Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single-channel dwell time histograms. Biophys J. 1987;52:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM. Molecular dissection of subunit interfaces in the acetylcholine receptor: identification of residues that determine curare selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9436–9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Claudio T, Sigworth FJ. Activation of Torpedo acetylcholine receptors expressed in mouse fibroblasts: single channel current kinetics reveal distinct agonist binding affinities. J Gen Physiol. 1990;96:395–437. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Ohno K, Bouzat C, Auerbach A, Milone M, Pruitt JN, Engel AG. Mutation of the acetylcholine receptor α subunit causes a slow-channel myasthenic syndrome by enhancing agonist binding affinity. Neuron. 1995;15:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Steinbach JH. Activation of acetylcholine receptors on clonal BC3H-1 cells by high concentrations of agonist. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;385:325–359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine SM, Taylor P. Functional consequences of agonist-mediated state transitions in the cholinergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3315–3325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchnya T, Xu L, Gao F, Fourtner C, Nicholson B. Identification of a proline residue as a transduction element involved in voltage gating of gap junctions. Nature (Lond) 1993;365:847–849. doi: 10.1038/365847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 9 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:1101–1124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Acetylcholine receptor imaged in the open state. Nature (Lond) 1995;373:37–43. doi: 10.1038/373037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela C, Weign P, Yguerabide J, Johnson D. Transverse distance between the membrane and agonist binding sites on the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor: a fluorescence study. Biophys J. 1994;66:674–682. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80841-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen J, Auerbach A. Activation of recombinant mouse acetylcholine receptors by acetylcholine, carbamylcholine, and tetramethylammonium. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;486:189–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]