Abstract

Single-channel and [3H]ryanodine binding experiments were carried out to examine the effects of imperatoxin activator (IpTxa), a 33 amino acid peptide isolated from the venom of the African scorpion Pandinus imperator, on rabbit skeletal and canine cardiac muscle Ca2+ release channels (CRCs). Single channel currents from purified CRCs incorporated into planar lipid bilayers were recorded in 250 mM KCl media. Addition of IpTxa in nanomolar concentration to the cytosolic (cis) side, but not to the lumenal (trans) side, induced substates in both ryanodine receptor isoforms. The substates displayed a slightly rectifying current–voltage relationship. The chord conductance at −40 mV was ∼43% of the full conductance, whereas it was ∼28% at a holding potential of +40 mV. The substate formation by IpTxa was voltage and concentration dependent. Analysis of voltage and concentration dependence and kinetics of substate formation suggested that IpTxa reversibly binds to the CRC at a single site in the voltage drop across the channel. The rate constant for IpTxa binding to the skeletal muscle CRC increased e-fold per +53 mV and the rate constant of dissociation decreased e-fold per +25 mV applied holding potential. The effective valence of the reaction leading to the substate was ∼1.5. The IpTxa binding site was calculated to be located at ∼23% of the voltage drop from the cytosolic side. IpTxa induced substates in the ryanodine-modified skeletal CRC and increased or reduced [3H]ryanodine binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles depending on the level of channel activation. These results suggest that IpTxa induces subconductance states in skeletal and cardiac muscle Ca2+ release channels by binding to a single, cytosolically accessible site different from the ryanodine binding site.

Keywords: sarcoplasmic reticulum, imperatoxin activator, substates, scorpion toxin, [3H]ryanodine binding

introduction

Ca2+ release channels (CRCs),1 also known as ryanodine receptors (RyRs), mediate the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular membrane compartment, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), into the cytoplasm in striated muscle cells. The CRC has been purified as a 30 S protein complex and shown to be composed of four large RyR polypeptides of ∼5,000 amino acid residues and four immunophilins (FK506 binding protein) of ∼100 amino acid residues each. Three tissue-specific isoforms of RyR have been identified. The conductances and pharmacological properties of the three isoforms are, to a large extent, similar (for reviews, see Meissner, 1994; Sutko and Airey, 1996).

Traditionally, venom from many poisonous snakes, lizards, and scorpions has been a rich source of peptide toxins that target various voltage- and ligand-gated channels including the CRCs (Furukawa et al., 1994; Morrissette et al., 1995, 1996). Recently, from the venom of the African scorpion Pandinus imperator, two factors, imperatoxin activator (IpTxa) and imperatoxin inhibitor (IpTxi), were isolated that selectively activated and inhibited, respectively, the CRCs (Valdivia et al., 1992; El-Hayek et al., 1995). IpTxa is a 33 amino acid peptide that activated the skeletal CRC in [3H]ryanodine binding and single channel studies. It did not exert a significant effect on cardiac CRC (Valdivia et al., 1992; El-Hayek et al., 1995; Zamudio et al., 1997a ). IpTxi has been shown to be a heterodimeric protein (subunits of 108 and 27 amino acid residues covalently linked by a disulfide bond) with lipolytic action, and it inhibited both skeletal and cardiac CRCs by generating a lipid product (Valdivia et al., 1992; Zamudio et al., 1997b ).

Here, we show that IpTxa induces voltage- and concentration-dependent subconductance states in both skeletal and cardiac CRCs when added to the cytosolic side. Analysis of voltage and concentration dependence and stochastic analysis of the events suggests that the induction of subconductance states corresponds to reversible, voltage-dependent binding and unbinding of IpTxa at a single, cytosolically accessible site located in the voltage drop across the channel. IpTxa also induced a subconductance state in the ryanodine-modified skeletal muscle CRC and affected [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles depending on the level of channel activation. These results provide evidence for the binding of IpTxa to a channel site different from that of ryanodine.

materials and methods

Phospholipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Preparation of SR Vesicles, and Purification and Reconstitution of Ca2+ Release Channels

SR vesicle fractions enriched in [3H]ryanodine binding and Ca2+ release channel activities were prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors from rabbit skeletal and canine cardiac muscle as described (Meissner, 1984; Meissner and Henderson, 1987). The CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamido-propyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate)-solubilized skeletal or cardiac muscle 30 S Ca2+ release channel complex was purified and reconstituted into proteoliposomes by removal of CHAPS by dialysis (Lee et al., 1994).

Purification and Synthesis of IpTxa

IpTxa was purified from P. imperator scorpion venom in three chromatographic steps as described (Valdivia et al., 1992; El-Hayek et al., 1995; Zamudio et al., 1997a ). Synthetic IpTxa was prepared as described (Zamudio et al., 1997a ).

Single Channel Measurements and Analysis

Single channel recordings of purified rabbit skeletal muscle or canine cardiac muscle CRCs incorporated into planar lipid bilayers were carried out as described (Tripathy et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1996). Preliminary experiments suggested that the rate of IpTxa-induced subconductance state formation depends on channel open probability (P o) (see Fig. 4 for a quantitative description). Therefore, experiments were conducted under “P o-clamp” conditions with P o values kept in the range of 0.75–1.0. For the skeletal CRC, in most cases 1–2 mM ATP was added to the cis bilayer chamber that also contained ∼5 μM free Ca2+ to bring the P o in the required range. For the cardiac CRC, where no determination of the kinetic constants was attempted, one set of experiments was conducted using cytosolic contaminant Ca2+ (∼4 μM) (P o = 0.3–0.5). In a second set, conducted under optimally activating conditions (10 μM cytosolic Ca2+), the P o was in the range of 0.8–1. Channel activities were recorded and analyzed using commercially available instruments and a software package (Axopatch 1D, Digidata 1200, and “pClamp 6.0.3;” Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA). Recordings were filtered at 2 or 4 kHz through an eight-pole low pass Bessel filter (Frequency Devices Inc., Haverhill, MA) and digitized at 10 or 20 kHz. The current values for the full and subconductance states at different holding potentials were obtained by constructing all point amplitude histograms and subsequent Gaussian fits of data from at least 2 min of channel recording. The probability of substate occurrence (P substate) was calculated as time spent in substate divided by the total recording time. Another parameter CRCsubstate/CRCfull state was calculated as time spent in substate divided by the time in full conductance state. The durations of the bursts (when the channel was in normal gating mode between the closed and full conductance levels) and subconductance states were obtained by manual positioning of the cursors.

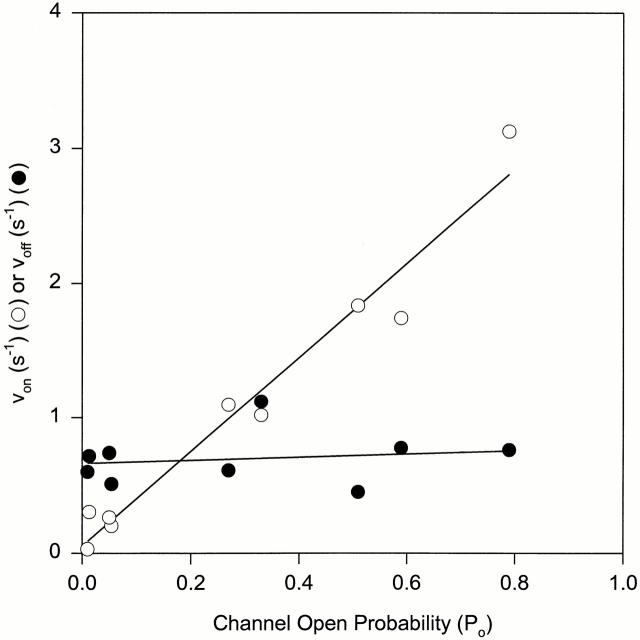

Figure 4.

Dependence of von and voff on the skeletal CRC open probability. The P o was varied by varying free Ca2+ in the cis bilayer chamber from <0.1 to 20 μM and in some cases adding 1–2 mM ATP. 20 nM synthetic IpTxa was added to the cis bilayer chamber and channel activities were recorded at a holding potential of −40 mV. The data are from three experiments. von (○) and voff (•) were obtained from exponential fits of dwell-times in the burst and subconductance state (see Fig. 6, legend). The coefficients of determination of the linear regression lines through the von and voff data points were 0.98 and 0.17, respectively.

[3H]Ryanodine Binding

[3H]Ryanodine binding experiments were carried out with rabbit skeletal and canine SR vesicles (protein: 150–250 μg/ml) in 0.25 M KCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 0.2 mM Pefabloc, 20 μM leupeptin, 0.1 mM EGTA, and [CaCl2] necessary to set the free [Ca2+] in the range of 0.1 μM to 10 mM. After incubation for 24 h at 24°C, bound radioactivity was determined by a filter assay as described (Tripathy et al., 1995). Nonspecific binding was determined with a 1,000-fold excess of unlabeled ryanodine.

Other Data Analysis and Conventions

Results are given as means ± SD with the number of experiments in parentheses. The SD is included within the figure symbol or indicated by error bars if it is larger. Significance of differences was analyzed with Student's paired t test. Differences were considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

results

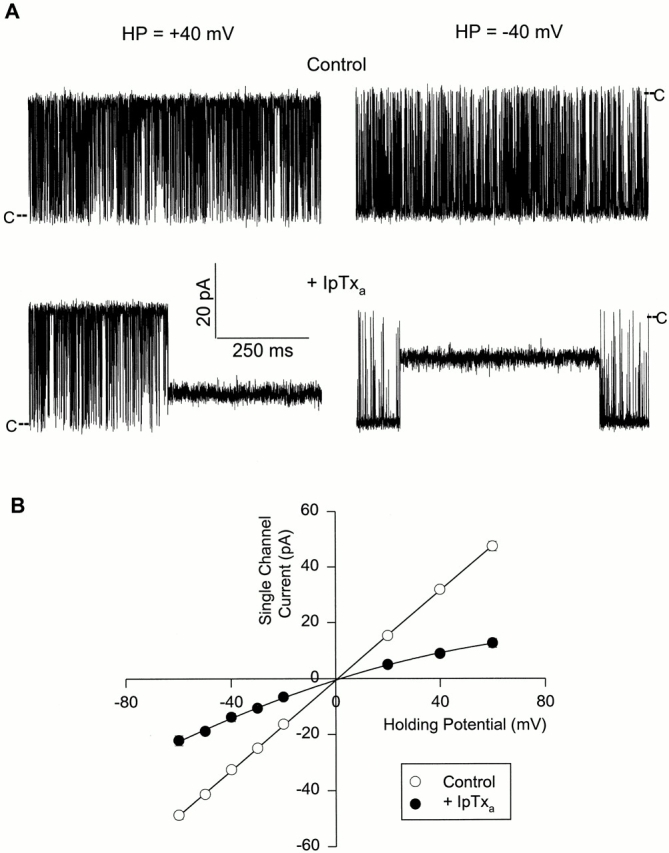

IpTxa Induces Subconductance States in Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle CRCs

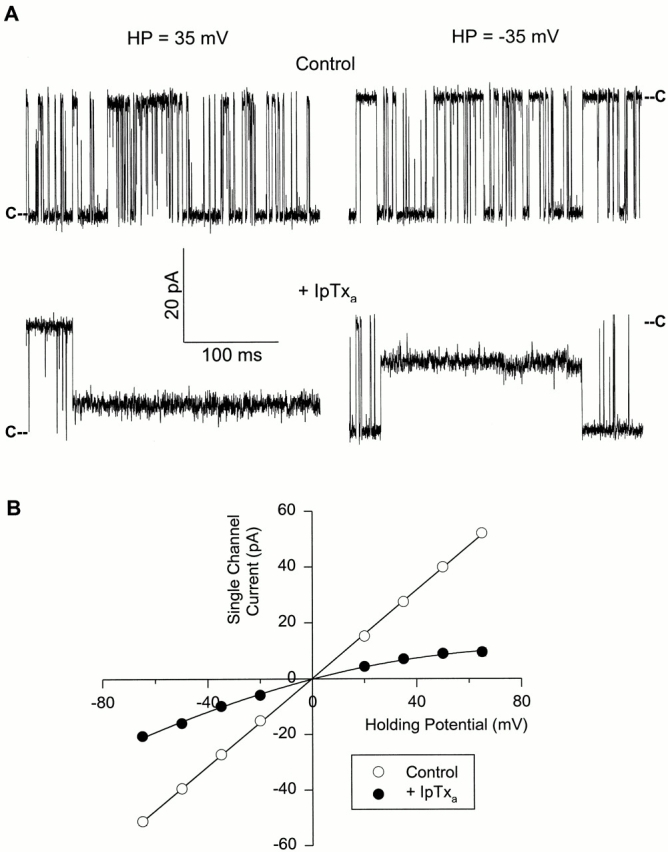

The skeletal and cardiac CRCs have been shown to conduct monovalent ions more efficiently than Ca2+ and to be essentially impermeant to Cl−. In 250 mM KCl solution, the single channel conductances of both isoforms are ∼770 pS (Meissner, 1994; and this study). When 15 nM native IpTxa was added to the cytosolic side (cis bilayer chamber) of a single skeletal CRC, the channel frequently entered a subconductance state (Fig. 1 A, left and right). In contrast to the linear current–voltage relationship of the unmodified CRC, the IpTxa-modified channel showed a slightly rectifying behavior (Fig. 1 B). The chord conductance at −40 mV holding potential was 344 ± 37 pS (∼43% of the full conductance state) and that at +40 mV was 221 ± 17 pS (∼28% of the full conductance state) (n = 8). Addition of up to 100 nM IpTxa to the lumenal side (trans bilayer chamber) had no effect (data not shown). This suggested that IpTxa induced subconductance states by interacting with the channel at a site accessible from the cytosolic side of the skeletal CRC. Occasionally, the CRC entered into conductance levels smaller than the main subconductance state. However, because of their very infrequent occurrences, these were not analyzed.

Figure 1.

IpTxa induces a subconductance state in skeletal CRC. (A) Shown are four recordings from one experiment at the indicated holding potentials. Single channel currents, shown as downward or upward deflections from closed levels (C), were recorded in symmetrical 0.25 M KCl, 10 mM KHepes, pH 7.3. The cis solution also contained ∼5 μM free Ca2+ and 1 mM ATP. The top current traces were obtained under control conditions and the bottom traces after addition of 15 nM native IpTxa to the cis solution. (B) Mean current values of the full conductance (○) and IpTxa-induced subconductance (•) states vs. holding potential. Data points are mean ± SD of eight experiments. The solid line through the full state current values is the linear regression line. The line through the substate current values was drawn by eye.

Fig. 2 shows similar experiments carried out with the cardiac CRC. Cytosolic addition of 15 nM IpTxa induced a substate (Fig. 2 A) with a magnitude and rectifying current–voltage relationship (Fig. 2 B) very similar to that of skeletal CRC. As was the case with skeletal CRC, addition of IpTxa to the lumenal side of cardiac CRC was without effect.

Figure 2.

IpTxa induces a subconductance state in cardiac CRC. (A) Shown are four recordings from one experiment at indicated holding potentials. Single channel currents, shown as downward or upward deflections from closed levels (C), were recorded in symmetrical 0.25 M KCl, 20 mM KHepes, pH 7.4. The cis and trans chamber solutions contained contaminant-free Ca2+ (∼4 μM). The top recordings were obtained under control conditions and the bottom recordings after addition of 15 nM native IpTxa to the cis solution. (B) Mean current values of the full conductance (○) and IpTxa-induced subconductance (•) states vs. holding potential. Data points are mean ± SD of three experiments. The solid line through the full state current values is the linear regression line. The line through the substate current values was drawn by eye.

With symmetrical 250 mM KCl and lumenal 25 mM Ca2+, the current carrier through the CRC is mostly Ca2+ at a holding potential of 0 mV. Under such recording conditions, IpTxa-induced subconductance states were observed for both the skeletal and cardiac muscle CRCs (data not shown). The substate conductances were ∼30% of the control full conductance values in both cases. Thus, induction of subconductance states in the CRCs by IpTxa does not depend upon the current carrier species. From hereon, we shall describe experiments carried out on the skeletal CRC. Channel conductances and IpTxa binding constants (see below) of the cardiac CRC are summarized and compared with the skeletal CRC in Table I.

Table I.

Channel Conductances and IpTxa Binding Constants of RyR1 and RyR2

| RyR1 | RyR2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −IpTxa | +IpTxa | −IpTxa | +IpTxa | |||||

| g−40 (pS) | 795 ± 26(8) | 344 ± 37(8) | 791 ± 11(3) | 298* | ||||

| g+40(pS) | 795 ± 26(8) | 221 ± 26(8) | 791 ± 11(3) | 187* | ||||

| K m (nM) | — | 20(5)‡ | — | 6.7(1)§ | ||||

| K d (nM) | — | 18.2(4)‡ | — | ND | ||||

| zδ | 1.49 ± 0.25(9)‖ ¶ | 1.32 ± 0.06(3)‡ ¶ | ||||||

| zδ | 1.54 ± 0.21(4)‖ ** | ND | ||||||

| zδ1 | 0.48 ± 0.04(4)‖ ** | ND | ||||||

| zδ2 | 1.06 ± 0.21(4)‖ ** | ND | ||||||

The data are mean ± SD of the number of experiments given in parentheses.

Estimated values at ±40 mV from the mean currents vs. voltage curve (Fig. 2 B).

and

Obtained with native and synthetic IpTxa, respectively. The K m and K d values of native IpTxa binding to skeletal CRC refer to values in 250 mM KCI medium and −20 mV holding potential. The K m of synthetic IpTxa binding to the cardiac CRC was obtained in 250 mM KCI medium and at −25 mV holding potential.

Mean values of experiments carried out with either native or synthetic IpTxa.

Obtained from Boltzmann fit of CRCsubstate/CRCfull state vs. holding potential curves.

Obtained from dwell-time analysis of bursts and substates.

Voltage, Concentration, and Po Dependence of IpTxa-induced Substates

The appearance of IpTxa-induced substates was highly voltage dependent. The probability of substate occurrence (P substate) was ∼0.05 at a holding potential of −60 mV. As the holding potential was made less negative, P substate increased and reached a value close to 1 at positive holding potentials (40–60 mV) (data not shown).

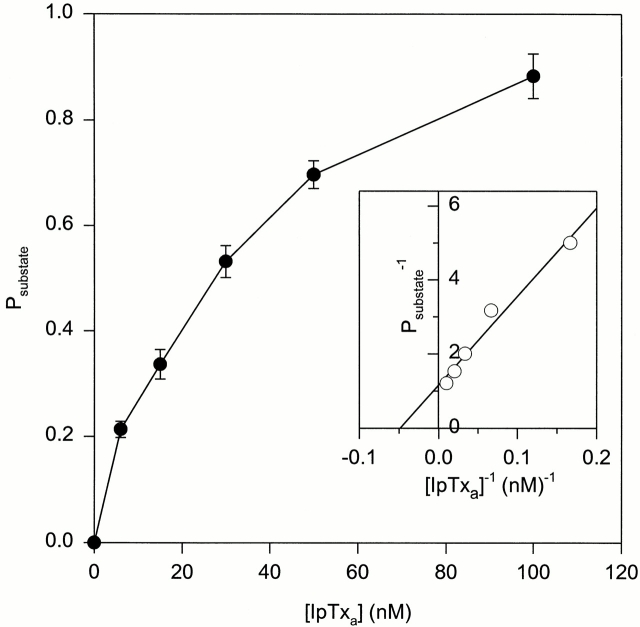

The concentration dependence of IpTxa effects on skeletal CRC was investigated at a holding potential of −20 mV by adding increasing concentrations of native IpTxa (from 6 to 100 nM) to the cis bilayer chamber. As shown in Fig. 3, P substate reached a value of 0.8 and greater as IpTxa concentration was raised to 100 nM. A Lineweaver-Burk plot (Fig. 3, inset) indicated that the data could be described by Michaelis-Menten-type kinetics with a P substate, max close to 1 and a K m of 20 nM. Under the same recording conditions, a lower K m value (∼2 nM) was observed when experiments were carried out on skeletal CRC using synthetic IpTxa (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of IpTxa-induced substate. P substate vs. native [IpTxa] for the skeletal CRC. Channel activities were recorded as in Fig. 1 A at a holding potential of −20 mV. Increasing concentrations (6–100 nM) of native IpTxa were added to the cis chamber solution. P substate was calculated at each [IpTxa]. Data points are mean ± SD of five experiments. A Lineweaver-Burk plot of the mean data is shown in the inset, giving a K m of 20 nM and a P substate, max of 0.91. Linear regression line drawn through the data points had a coefficient of determination of 0.97.

The rate of IpTxa-induced substate formation was dependent on channel open probability. Fig. 4 examines this question quantitatively by displaying the rates of subconductance state appearance and disappearance (see next section for the determination of IpTxa association and dissociation rates) as a function of P o. The subconductance states were rarely observed when the channel was closed, and the rate of their appearance increased linearly with P o. In contrast, IpTxa dissociation rate from the CRC was independent of P o.

A Kinetic Scheme of IpTxa and CRC Interaction, and Testing Its Predictions

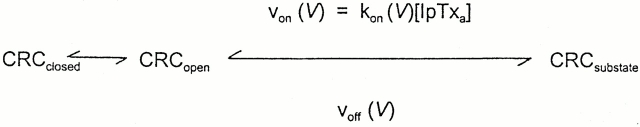

The concentration, voltage, and P o dependence of IpTxa action suggested that IpTxa binds to the open channel at a single site located in the voltage drop across the channel. Following published procedures (Strecker and Jackson, 1989; Moczydlowski, 1992; Tinker et al., 1992a ), we modeled the interaction of IpTxa with CRC according to Scheme SI.

Scheme I.

In Scheme SI, V refers to voltage across the membrane, von (V) and kon (V) are the observed microscopic voltage-dependent association rate and rate constant of IpTxa binding to the channel, respectively. The velocity of IpTxa dissociation from the subconductance state, voff (V) is a unimolecular microscopic rate constant, koff, and is also voltage dependent. Assuming a Boltzmann distribution between the full and subconductance states, we can write CRCsubstate/CRCfull state = exp [(zδFV − G 0)/ RT], where CRCsubstate/CRCfull state refers to time spent in the subconductance state divided by the time spent in the full conductance state of the CRC.

The explicit dependence of kon and koff on voltage can be expressed as follows: kon(V) = kon(0)exp(zδ1 FV/ RT), and koff(V) = koff(0)exp(−zδ2 FV/RT), where z is the valence of the blocking particle, δ (= δ1 + δ2) is the fractional electrical distance of the binding site from the reference state at the cytosolic side, δ1 is the distance between the transition state and the reference state, and R, T, and F have their usual meanings.

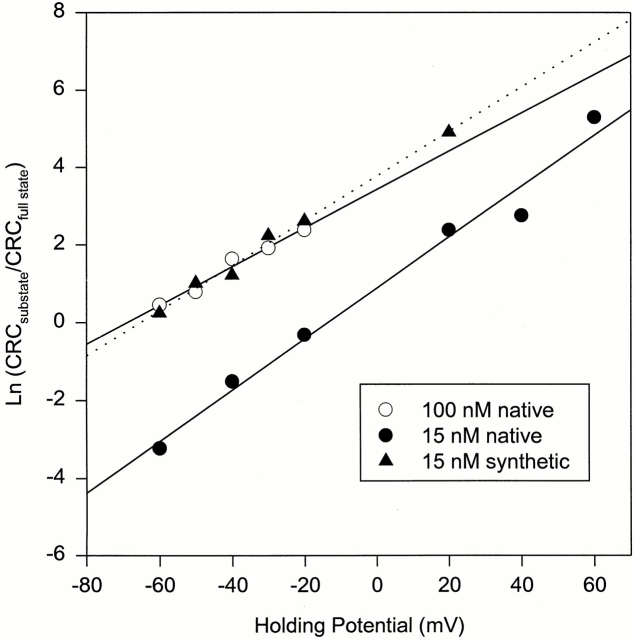

Channel activities of skeletal CRC were recorded in the presence of two different concentrations (15 and 100 nM) of native and one concentration (15 nM) of synthetic IpTxa at various holding potentials. Ln (CRCsubstate/ CRCfull state) values from one experiment in each condition are plotted against holding potential in Fig. 5. As predicted, the data followed Boltzmann distribution. The mean zδ values at 15 and 100 nM native IpTxa were 1.44 ± 0.28 (n = 4) and 1.42 ± 0.28 (n = 3), respectively. The mean zδ from two experiments at 15 nM synthetic IpTxa was 1.66. When all the data were pooled, the mean zδ was 1.49 ± 0.25 (n = 9) (Table I).

Figure 5.

Plots of the natural logarithms of CRCsubstate/CRCfull state vs. holding potential for the skeletal CRC. Channel activities were recorded as in Fig. 1 A at holding potentials of −60 to +60 mV. IpTxa concentrations in the cis chamber solution were: 15 nM native (•), 100 nM native (○), and 15 nM synthetic (▴). The coefficients of determination and zδ values, respectively, were as follows: 15 nM native, 0.97 and 1.65; 100 nM native, 0.98 and 1.25; and 15 nM synthetic, 0.99 and 1.47.

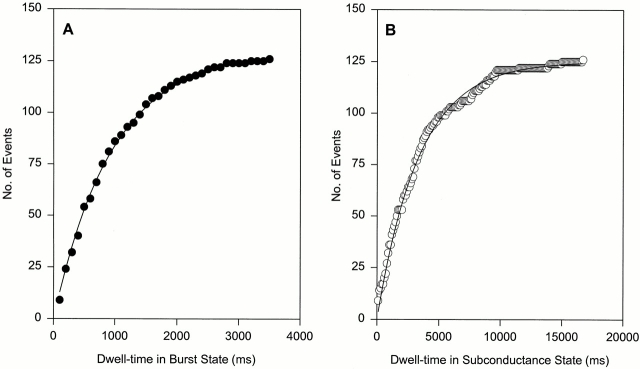

The voltage dependence of kon and koff was investigated for the skeletal CRC at 100 nM native and 15 nM synthetic IpTxa at holding potentials varying from −60 to −20 mV. Dwell times corresponding to the substate and the burst mode were calculated from single channel records containing 30–150 events for each state. Following the predictions of Scheme SI, the distribution of dwell times in each state followed a single exponential (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Single exponential fits of dwell-time data. Data from an experiment with skeletal CRC at a holding potential of −20 mV and 100 nM cytosolic native IpTxa. (A) Exponential fit of dwell-times in the burst state. Data were sorted into histograms of 100-ms bin width in the cumulative binning mode and fitted to the probability distribution function F(t) = A(1 − exp[−t/τ]) (solid line), where total number of events (A) was 130 and the time-constant τ was 965 ms. (B) Exponential fit of dwell-times in the subconductance state. Data were sorted and fitted (solid line) as in A. The time-constant τ was 3,376 ms.

Plots of the natural logarithms of kon and koff (obtained from exponential fits of dwell-time data) from four experiments against the holding potential followed Boltzmann distribution (not shown). The mean zδ1 and zδ2 from four experiments (two at 100 nM native and two at 15 nM synthetic IpTxa) were 0.48 ± 0.04 and 1.06 ± 0.21, respectively, with a mean zδ of 1.54 ± 0.21. This latter value is almost identical to the mean zδ value of 1.49 ± 0.25, which was obtained from the plots of the natural logarithms of CRCsubstate/CRCfull state vs. holding potential (Fig. 5 and Table I). The data further show that the unbinding rate is twice as voltage dependent as the binding rate. The mean kon increased e-fold per +53.3 (±5.6 mV, n = 4) of applied holding potential. The mean koff and mean K d decreased e-fold per +24.7 (±4.9 mV, n = 4) and +17.4 (±2.3 mV, n = 4) of applied holding potential, respectively.

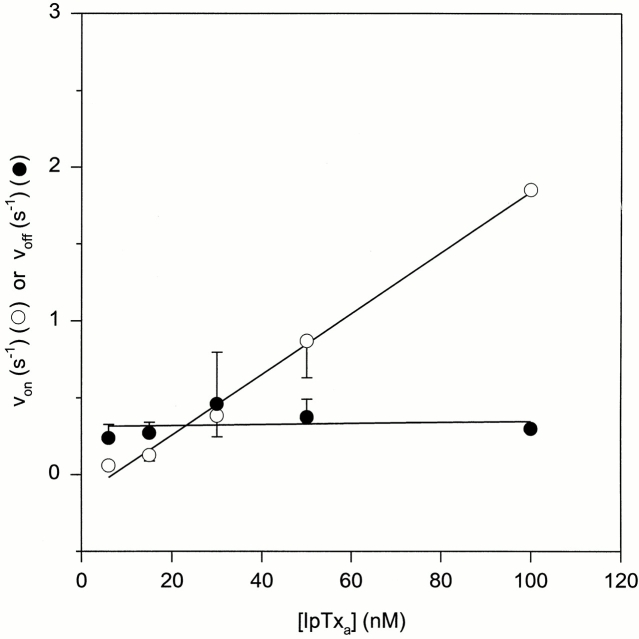

Next, we tested the predictions pertaining to the IpTxa concentration dependence of von and voff (Fig. 7). Skeletal CRC channel activities were recorded at a holding potential of −20 mV at five different native IpTxa concentrations varying from 6 to 100 nM. The regression lines drawn through the mean von and voff data points have coefficients of determination of 0.99 and 0.02, respectively, thus supporting the prediction that von is linearly dependent on IpTxa concentration and voff is independent of it. From the data, a kon (von/[IpTxa]) value of 1.7 × 107 M−1 s−1 and a koff value of 0.31 s−1 were obtained, which gave a K d (koff/kon) of 18.2 nM. This K d value is very close to the K m value of 20 nM that was obtained from the Michaelis-Menten analysis of P substate vs. native [IpTxa] curve under identical recording conditions (−20 mV holding potential and 250 mM KCl medium) (Fig. 3 and Table I).

Figure 7.

Dependence of von and voff on [IpTxa]. Increasing concentrations (6–100 nM) of native IpTxa were added to the cis solution and channel activities were recorded at −20 mV. The data are mean ± SD of three to four experiments except at 100 nM IpTxa, which is mean of two experiments. The coefficients of determination of the linear regression lines through the mean von (○) and voff (•) data points were 0.99 and 0.02, respectively.

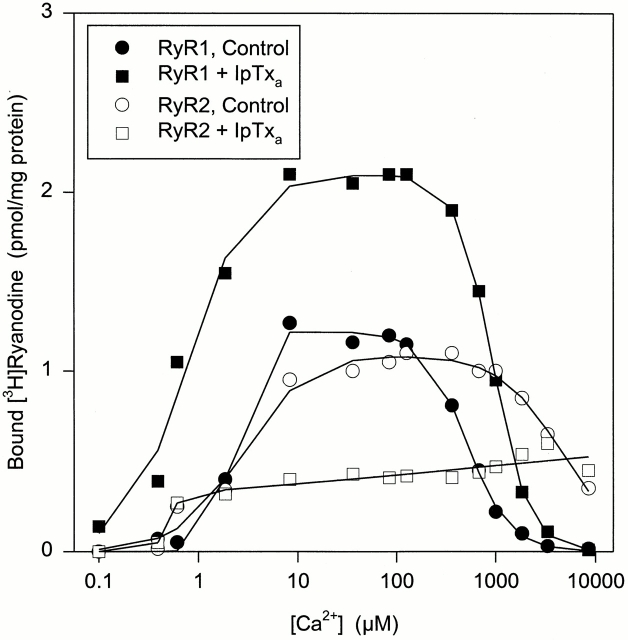

IpTxa Modifies [3H]Ryanodine Binding to Skeletal and Cardiac SR Vesicles

Previous studies had suggested that IpTxa preferentially binds to and activates the skeletal CRC and that cardiac CRC is a poor target of IpTxa (Valdivia et al., 1992; El-Hayek et al., 1995; Zamudio et al., 1997a ). Since we observed that IpTxa induces subconductance states in both the skeletal and cardiac CRCs, we reexamined the effects of IpTxa in [3H]ryanodine binding experiments using skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles. Fig. 8 shows the Ca2+ activation profiles of CRCs as measured by [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles in the absence and presence of 30 nM synthetic IpTxa. As observed previously (Valdivia et al., 1992; El-Hayek et al., 1995; Zamudio et al., 1997a ), IpTxa increased [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal SR vesicles. Activation occurred at all tested Ca2+ concentrations with the possible exception of 10 mM, where [3H]ryanodine binding levels were close to background. In contrast to its effect on skeletal SR vesicles, IpTxa decreased [3H]ryanodine binding to the cardiac SR vesicles up to twofold at a Ca2+ concentration of 10 μM–1 mM. At low (<1 μM) and high (>1 mM) Ca2+ concentration, it was without a noticeable effect.

Figure 8.

Effect of IpTxa on [3H]ryanodine binding to SR vesicles. Specific [3H]ryanodine binding to rabbit skeletal (•, ▪) or canine cardiac (○, □) SR vesicles in the absence (•, ○) or presence (▪, □) of 30 nM synthetic IpTxa was determined as described in materials and methods. The data are from one of three similar experiments with skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles.

[3H]ryanodine binding measurements have been and are extensively used as indicators of the number of channels and their activities (Meissner, 1994). We did not observe an increase in P o of the skeletal CRC nor a decrease in P o of cardiac CRC in bilayer experiments after addition of IpTxa (data not shown). Therefore, we were surprised to find that IpTxa affected the [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal and cardiac CRCs so differently. To gain further insights, we performed Scatchard analysis of [3H]ryanodine binding to both CRC isoforms in the presence and absence of IpTxa (data not shown). IpTxa (30 nM, synthetic) decreased the K d of [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal SR vesicles approximately threefold (Table II). A small increase in maximum binding (Bmax) (from 13.5 to 17.5 pmol/mg) was also observed after IpTxa treatment. In contrast, 30 nM IpTxa increased the K d of [3H]ryanodine binding to cardiac SR ∼3.5-fold without an appreciable effect on the Bmax value. The above experiments were carried out at 100 μM free Ca2+. The cardiac CRC is nearly fully active at this [Ca2+] (Xu et al., 1996), whereas in the absence of other activating ligands, 100 μM Ca2+ cannot fully activate the skeletal CRC. To test if the different effects of IpTxa on skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles were due to the different activation levels of CRCs, we performed Scatchard analysis of [3H]ryanodine binding using maximally activating conditions (100 μM Ca2+ and 5 mM AMP-PCP) for both CRC isoforms. Under these conditions, IpTxa affected the [3H]ryanodine binding to the skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles in a similar manner. The K d of [3H]ryanodine binding to the skeletal SR vesicles increased ∼1.3-fold and that for the cardiac SR vesicles ∼4.5-fold without a change in the Bmax values in both cases (Table II).

Table II.

[3H]Ryanodine Binding to Skeletal and Cardiac SR Vesicles

| Composition of assay media | Bmax (pmol/mg protein) | K d (nM) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −IpTxa | +IpTxa | −IpTxa | +IpTxa | |||||||

| RyR1 | 100 μM Ca2+ | 13.5 ± 0.9 | 17.5 ± 2.1* | 16.6 ± 6.0 | 6.1 ± 2.7* | |||||

| 100 μM Ca2+ + 5 mM AMP PCP | 17.5 ± 2.1 | 16.2 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 1.5* | ||||||

| RyR2 | 100 μM Ca2+ | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 0.7* | |||||

| 100 μM Ca2+ + 5 mM AMP PCP | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 8.1 ± 1.0* | ||||||

The experiments were carried out using 30 nM synthetic IpTxa. The data are mean ± SD of three experiments.

Significantly different from control conditions (−IpTxa).

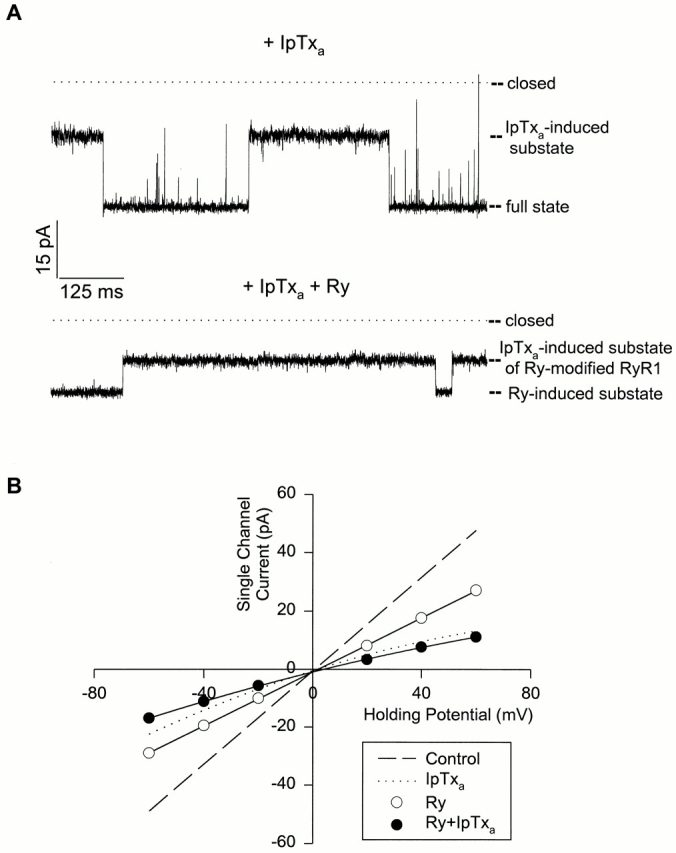

IpTxa Induces Substates in Ryanodine-modified Skeletal Muscle CRC

In Fig. 9, we explored the cointeraction of IpTxa and ryanodine with the skeletal CRC at the single channel level. After addition of 100 nM IpTxa to the cis bilayer chamber, the channel current fluctuated between the full conductance and IpTxa-induced subconductance states (Fig. 9 A, top). After further addition of 5 μM ryanodine to the cis chamber, the channel current fluctuated between two new levels (Fig. 9 A, bottom). The current–voltage relationships in presence of both IpTxa and ryanodine are shown in Fig. 9 B. The higher subconductance state had linear current–voltage characteristics and was identified as the ryanodine-modified subconductance state of the CRC (Lai et al., 1989). The less conducting IpTxa-induced substate of the ryanodine-modified CRC had a rectifying current–voltage characteristic. For comparison, the control and the IpTxa-induced substate current–voltage curves (in the absence of ryanodine) from Fig. 1 B are redrawn as a dashed and dotted line, respectively, in Fig. 9 B. The new substate conductance in the presence of both IpTxa and ryanodine was significantly smaller than the IpTxa-induced substate (in the absence of ryanodine) at all applied holding potentials.

Figure 9.

Effects of IpTxa and ryanodine on skeletal CRC. (A) IpTxa-induced subconductance states in the absence and presence of ryanodine. Shown are two current traces recorded at −40 mV. Single channel currents, shown as downward deflections from closed levels, were recorded in media as given in Fig. 1 A, legend, but with 100 nM cytosolic native IpTxa. The top current trace was obtained before and the bottom trace after addition of 5 μM ryanodine to the cis solution. The current levels of the different states are indicated. (B) Current–voltage curves of skeletal CRC in presence of both IpTxa and ryanodine. Channels were recorded as in A. The ryanodine- induced substate currents (○) and IpTxa-induced substate currents in the presence of ryanodine (•) are shown. The data are mean ± SD of three experiments. The dashed and dotted lines are the control and IpTxa-induced substate current– voltage curves, respectively, in the absence of ryanodine, and are same as in Fig. 1 B.

discussion

The present studies explored the effects of IpTxa on purified CRCs in single channel experiments, and on SR vesicles in [3H]ryanodine binding experiments. In these studies, we provide the first evidence that IpTxa directly interacts with both skeletal and cardiac CRCs to induce voltage- and concentration-dependent subconductance states in both isoforms by binding at a single site, located in the voltage drop across the channel. Second, we show that IpTxa affects the [3H]ryanodine binding characteristics of the two isoforms depending on the level of channel activation.

Interaction of IpTxa with CRCs as Revealed by Single-Channel Experiments

We modeled the interaction of IpTxa with the CRC as outlined in Scheme SI. Briefly, we envisaged that when the channel opened, an IpTxa molecule entered the conductance pathway from the cytosolic side to bind at an internal site. The model presented us with some testable predictions that were all satisfied. The distribution of dwell-times in each state (burst and subconductance) followed a single exponential. The reciprocal mean dwell-time in the burst state was linearly dependent on, and the reciprocal mean dwell-time in the subconductance state was independent of, IpTxa concentration. A K d value of IpTxa binding to skeletal CRC could be calculated from the dwell-time analysis, and it was very close to that obtained from the Michaelis-Menten-type concentration-dependence curve under identical conditions.

The effective valence of the reaction leading to substate formation was determined to be ∼1.5 for the skeletal CRC (the value for cardiac CRC was ∼1.3). From the known amino acid sequence of IpTxa (Zamudio et al., 1997a ) and using the program “Isoelectric” of the GCG suite (Genetics Computer Group, Inc., Madison, WI), we calculated a net charge of 6.5 at pH 7.3. Dividing the effective valence by this number gives an electrical distance of ∼0.23 from the cytosolic side for the location of IpTxa binding site. This is based on the assumption that all the charges of IpTxa enter the CRC conduction pathway. The unbinding reaction of IpTxa from the CRC has a twofold higher voltage dependence than the binding reaction. Higher voltage dependence for the unbinding rate has also been observed in case of tetrabutyl ammonium (TBA+)–induced substate in the cardiac CRC (Tinker et al., 1992a ) and curare-induced subconductance state in the acetylcholine receptor channel (Strecker and Jackson, 1989).

IpTxa is a relatively small peptide of 3,765 D with three pairs of cysteine residues that would stabilize the three-dimensional (3-D) conformation and help it assume a compact globular form by forming disulfide bridges (Zamudio et al., 1997a ). Preliminary modeling work suggests that IpTxa structure can be roughly approximated as a sphere of ∼2.5 nm in diameter. The selectivity filter of the skeletal CRC has a diameter of ∼0.7 nm, as choline+, Tris+, and glucose can permeate through the channel (Meissner, 1986; Smith et al., 1988), while sucrose cannot (G. Meissner, unpublished observations). Therefore, IpTxa cannot enter the selectivity filter of the CRC. On the other hand, studies with large tetraalkyl ammonium ions (Tinker et al., 1992a ) and charged local anesthetics (Tinker and Williams, 1993) have suggested that the sheep cardiac CRC has a relatively large vestibule facing the cytosolic side. Theoretical considerations have suggested that a significant proportion of the voltage drop may fall over the wide vestibule of a channel (Jordan, 1986). Our studies showed that the vestibule has to be at least 2–2.5-nm wide to accommodate IpTxa, and at least ∼23% of the voltage falls over the vestibule. Interestingly, 3-D cryo-electron micrographic reconstruction of the skeletal muscle CRC (Radermacher et al., 1994; Serysheva et al., 1995) shows a central opening of ∼5 nm in the cytoplasmic domain (facing the transverse tubule), and thus supports the presence of a wide vestibule facing the cytoplasmic side of the CRC.

Mechanism of Subconductance State Formation

We considered it unlikely that IpTxa would produce subconductance states by a surface charge mechanism (Green and Andersen, 1991). The estimated decrease in local [K+] using the Guoy-Chapman double-layer theory (McLaughlin, 1977) was only approximately fourfold (assuming zero net surface charge near the cytosolic face of the CRC and the IpTxa net positive charge of 6.5 spread out over a sphere of ∼2.5-nm diameter). This decrease (from 250 to 62.5 mM) was not sufficient to cause the subconductance state as the K d of K+ for the cardiac CRC has been shown to be ∼20 mM (Tinker et al., 1992b ). However, if the positive charges of IpTxa are clustered in a much smaller area (leading to a higher charge density), the local [K+] could be much lower, which may explain the formation of subconductance state. The above possibility is also not very likely as the ratios of subconductance to full conductance values were similar, and there was no indication of any relief of block, when the [KCl] in the bilayer chambers was increased symmetrically from 250 to 500 mM (data not shown). However, we observed an increase in the K d of IpTxa binding to CRC when [KCl] was raised from 250 to 500 mM (our unpublished studies). Similar effects of increasing [KCl] on K d have been observed by other investigators studying other toxins (Anderson et al., 1988; Lucchesi and Moczydlowski, 1990).

In our experiments with the purified CRCs in bilayer experiments, substates of different amplitudes are sometimes observed even in control recordings. These substates show linear current–voltage relationships. Therefore, it is conceivable that IpTxa preferentially binds to and stabilizes a normally occurring CRC substate. However, we think this to be an unlikely mechanism as the IpTxa-induced substates had different conductances at positive and negative holding potentials (Figs. 1 and 2, and Table I).

How then does IpTxa reduce channel conductance? Is it by partial occlusion of the channel pore or by a conformational change? Tetrabutyl and tetrapentyl ammonium–induced substates in the cardiac CRC have been explained in terms of partial occlusion of the conduction pathway (Tinker et al., 1992a ). Convincing arguments have been put forward in favor of partial block of acetylcholine receptor channel by curare (Strecker and Jackson, 1989) and complete block of a maxi Ca2+-activated K+ channel by charybdotoxin (Anderson et al., 1988; MacKinnon and Miller, 1988). In the former case, displacing curare from the agonist binding sites of acetylcholine receptor channel had no effect on the kinetics of subconductance state occurrence. In the latter case, enhancement of external toxin dissociation by internal K+ and competition for the toxin-binding site by external tetraethylammonium ions gave strong support to the occlusion model. On the other hand, Zn2+-induced substates in canine cardiac sarcolemma sodium channel (Schild et al., 1991) and proton and deuterium ion-induced substates in a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (Prod'hom et al., 1987; Pietrobon et al., 1989) have been explained in terms of conformational changes; as in the above two cases, voff was dependent on the blocker concentration. Furthermore, in case of dendrotoxin-I (DTX-I)-induced substate formation in a maxi Ca2+-activated K+ channel, a conformational change mechanism was also favored as the toxin converted the linear control current–voltage relationship to a rectifying one, though in this case von and voff were linearly dependent on and independent of the toxin concentration (Lucchesi and Moczydlowski, 1990). In the present case, IpTxa binding converted an ohmic CRC to a rectifying one. Furthermore, IpTxa-modified CRCs (both skeletal and cardiac) had higher K ds of [3H]ryanodine binding under fully activating conditions (conditions similar to bilayer recording conditions) (see below for further discussion on this aspect). These observations favor an IpTxa-induced conformational change in both the skeletal and cardiac CRCs as the mechanism causing the subconductance state. Alternatively, resultant conformational changes by the membrane electric field may cause IpTxa to differentially occlude the CRC at positive and negative holding potentials to produce substates of different conductances. Regardless of whether partial occlusion of the pore or a conformational change is the mechanism causing subconductance state formation, our studies strongly suggest the existence of a cytosolically accessible IpTxa binding site in the conductance pathway of both the skeletal and cardiac CRC.

Difference in Potency Between Native and Synthetic IpTxa

Most of our experiments were conducted using native, purified IpTxa. In some experiments carried out using synthetic IpTxa, we observed that the synthetic toxin was ∼10-fold more effective in inducing substates in skeletal and cardiac CRCs than its native counterpart. The reasons for this difference are not clear. One possibility is that during purification the native toxin lost part of its biological activity.

Cointeraction of IpTxa and Ryanodine with CRCs

[3H]ryanodine binding correlates reasonably well with CRC activation levels. Because of its simplicity and convenience, it is extensively used to explore the effects of many drugs/toxins on CRC. But as this study shows, direct measurements of channel activity can provide insights that might not be detected by [3H]ryanodine binding measurements. When the effects of IpTxa were assessed at 100 μM free Ca2+, an increase in [3H]ryanodine binding level for the skeletal but a decrease for the cardiac SR vesicles was observed (Fig. 8), though the net effect is the formation of subconductance states in both isoforms in bilayer experiments. Furthermore, using purified skeletal CRC, we demonstrated that IpTxa can still bind and induce substates of slightly smaller conductances in the ryanodine-modified channel (Fig. 9, A and B). Similar paradoxical results were observed in studies exploring the effects of polyamines on the CRCs. Polyamines increased [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal SR vesicles approximately fivefold (Zarka and Shoshan-Barmatz, 1992). However, in single-channel studies, it caused a blockade of the cardiac CRC, and no increase in P o was observed (Uehara et al., 1996). Though [3H]ryanodine binding and single channel experiments were done on different CRC isoforms, the above experiments and the present study call for caution in interpreting [3H]ryanodine binding results in the presence of other drugs and toxins.

The apparently paradoxical effects of IpTxa on skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles in [3H]ryanodine binding measurements led us to investigate its effects in detail. At 100 μM Ca2+, IpTxa caused a decrease in K d (with a small increase in Bmax) for the skeletal SR vesicles, but an increase in K d with little or no change in Bmax for the cardiac SR vesicles (Table II). The affinity of [3H]ryanodine binding to SR vesicles correlates with the CRC activation level, suggesting that ryanodine binds to an open channel (Meissner, 1994). The IpTxa-induced long-lived substates in the skeletal CRC would thus provide a favorable environment over the rapidly gating control low channel activity (at 100 μM Ca2+) for ryanodine entry into the CRC interior and subsequent binding. For the cardiac CRC, which is maximally active at 100 μM Ca2+, the substates provided no further improvement. On the contrary a decrease was observed, probably because the IpTxa-modified channel may have reduced affinity for ryanodine. In favor of this idea, we observed that under maximally activating conditions for both CRC isoforms (100 μM Ca2+ and 5 mM AMP-PCP), IpTxa decreased the K ds of [3H]ryanodine binding to both skeletal and cardiac SR vesicles (Table II). Furthermore, IpTxa increased [3H]ryanodine binding to cardiac SR vesicles under minimally activating conditions (∼1 μM Ca2+) just as it increased [3H]ryanodine binding to skeletal SR vesicles under suboptimally activating conditions (100 μM Ca2+) (our unpublished studies). Thus, our data show that the IpTxa-modified CRC (both skeletal and cardiac) has a K d of [3H]ryanodine binding intermediate between those of the minimally and maximally activated channel.

In conclusion, the present work demonstrates a direct, high affinity interaction of IpTxa with both the skeletal and cardiac CRCs. The use of IpTxa should aid in the structural elucidation of the ion-conductance pathway of the skeletal and cardiac muscle CRCs. Furthermore, we show that experiments exploring effects of drugs/toxins on CRCs by [3H]ryanodine binding measurements must be interpreted with caution and be correlated with measurements of channel activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant HL-55438 and Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (to H.H. Valdivia) and NIH grants AR-18687 and HL-27430 (to G. Meissner).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CRC

Ca2+ release channel

- IpTxa

imperatoxin activator

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

Footnotes

The authors express their appreciation to Dan Pasek for carrying out the [3H]ryanodine binding experiments and Ling Gao for help with the GCG program.

references

- Anderson C, MacKinnon R, Smith C, Miller C. Charybdotoxin inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+channels. Effects of channel gating, voltage, and ionic strength. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91:317–333. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hayek R, Lokuta AJ, Arevalo C, Valdivia HH. Peptide probe of ryanodine receptor function. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28696–28704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K-I, Funayama K, Ohkura M, Oshima Y, Tu AT, Ohizumi Y. Ca2+ release induced by myotoxin a, a radio-labellable probe having novel Ca2+release properties in sarcoplasmic reticulum. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN, Andersen OS. Surface charges and ion channel function. Annu Rev Physiol. 1991;53:341–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.C. 1986. Ion channel electrostatics and the shapes of channel proteins. In Ion Channel Reconstitution. C. Miller, editor. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York. 37–55.

- Lai FA, Mishra M, Xu L, Smith HA, Meissner G. The ryanodine receptor–Ca2+release channel complex of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Evidence for a cooperatively coupled, negatively charged homotetramer. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16776–16785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-B, Xu L, Meissner G. Reconstitution of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor-Ca2+release channel protein complex into proteoliposomes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13305–13312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi K, Moczydlowski E. Subconductance behavior in a maxi Ca2+-activated K+channel induced by dendrotoxin-I. Neuron. 1990;2:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90450-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R, Miller C. Mechanism of charybdotoxin block of the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+channel. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91:335–349. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S. Electrostatic potentials at membrane-solution interfaces. Curr Top Membr Trans. 1977;9:71–144. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G. Adenine nucleotide stimulation of Ca2+-induced Ca2+release in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:2365–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G. Ryanodine activation and inhibition of the Ca2+release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6300–6306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Henderson GS. Rapid calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles is dependent on Ca2+ and is modulated by Mg2+, adenine nucleotide and calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G. Ryanodine receptor/Ca2+release channels and their regulation by endogenous effectors. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:485–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette J, Kratzschmar J, Haendler B, El-Hayek R, Mochca-Morales J, Martin BM, Patel JR, Moss RL, Schleuning W-D, Coronado R, Possani LD. Primary structure and properties of helothermine, a peptide toxin that blocks ryanodine receptors. Biophys J. 1995;68:2280–2288. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80410-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette J, Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Coronado R. Purification and characterization of ryanotoxin, a peptide with actions similar to those of ryanodine. Biophys J. 1996;71:707–721. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczydlowski E. Analysis of drug action at single-channel level. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:791–806. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07056-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon D, Prod'hom B, Hess P. Interactions of protons with single open L-type calcium channels. pH dependence of proton-induced current fluctuations with Cs+, K+, and Na+as permeant ions. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:1–21. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prod'hom B, Pietrobon D, Hess P. Direct measurement of proton transfer rates to a group controlling the dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+channel. Nature. 1987;329:243–246. doi: 10.1038/329243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radermacher M, Rao V, Grassucci R, Frank J, Timerman AP, Fleischer S, Wagenknecht T. Cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction of the calcium release channel/ryanodine receptor from skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:411–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serysheva II, Orlova EV, Chiu W, Sherman MB, Hamilton SL, van Heel M. Electron cryomicroscopy and angular reconstitution used to visualize the skeletal muscle calcium release channel. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:18–24. doi: 10.1038/nsb0195-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Ravindran A, Moczydlowski E. Zn2+-induced subconductance events in cardiac Na+channels prolonged by batrachotoxin. Current–voltage behavior and single-channel kinetics. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:117–142. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Imagawa T, Ma J, Fill M, Campbell K, Coronado R. Purified ryanodine receptor from rabbit skeletal muscle is the calcium-release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:1–26. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker GJ, Jackson MB. Curare binding and the curare-induced subconductance state of the acetylcholine receptor channel. Biophys J. 1989;89:795–806. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82726-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutko JL, Airey JA. Ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels: does diversity in form equal diversity in function? . Physiol Rev. 1996;76:1027–1071. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker A, Lindsay ARG, Williams AJ. Large tetraalkyl ammonium cations produce a reduced conductance state in the sheep cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel. Biophys J. 1992a;92:1122–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81922-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker A, Lindsay ARG, Williams AJ. A model for ionic conduction in the ryanodine receptor channel of sheep cardiac muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Gen Physiol. 1992b;100:495–517. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker A, Williams AJ. Charged local anesthetics block ionic conduction in the sheep cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release channel. Biophys J. 1993;65:852–864. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy A, Xu L, Mann G, Meissner G. Calmodulin activation and inhibition of skeletal muscle Ca2+release channel. Biophys J. 1995;69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79880-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara A, Fill M, Velez P, Yasukochi M, Imanaga I. Rectification of rabbit cardiac ryanodine receptor current by endogenous polyamines. Biophys J. 1996;71:769–777. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia HH, Kirby MS, Lederer WJ, Coronado R. Scorpion toxins targeted against the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12185–12189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Mann G, Meissner G. Regulation of cardiac Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) by Ca2+, H+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides under normal and simulated ischemic conditions. Circ Res. 1996;79:1100–1109. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio FZ, Gurrola GB, Arevalo C, Sreekumar R, Walker JW, Valdivia HH, Possani LD. Primary structure and synthesis of imperatoxin A (IpTxa), a peptide activator of Ca2+release channels/ryanodine receptors. FEBS Lett. 1997a;405:385–389. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio FZ, Conde R, Arevalo C, Becerril B, Martin BM, Valdivia HH, Possani LD. The mechanism of inhibition of ryanodine receptor channels by imperatoxin I, a heterodimeric protein from the scorpion Pandinus imperator. . J Biol Chem. 1997b;272:11886–11894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarka A, Shoshan-Barmatz V. The interaction of spermine with the ryanodine receptor from skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1108:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]