Abstract

Ion transport and regulation were studied in two, alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from Drosophila melanogaster. These exchangers, designated CALX1.1 and CALX1.2, differ by five amino acids in a region where alternative splicing also occurs in the mammalian Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, NCX1. The CALX isoforms were expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes and characterized electrophysiologically using the giant, excised patch clamp technique. Outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents, where pipette Ca2+ o exchanges for bath Na+ i, were examined in all cases. Although the isoforms exhibited similar transport properties with respect to their Na+ i affinities and current–voltage relationships, significant differences were observed in their Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent regulatory properties. Both isoforms underwent Na+ i-dependent inactivation, apparent as a time-dependent decrease in outward exchange current upon Na+ i application. We observed a two- to threefold difference in recovery rates from this inactive state and the extent of Na+ i-dependent inactivation was approximately twofold greater for CALX1.2 as compared with CALX1.1. Both isoforms showed regulation of Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity by Ca2+ i, but their responses to regulatory Ca2+ i differed markedly. For both isoforms, the application of cytoplasmic Ca2+ i led to a decrease in outward exchange currents. This negative regulation by Ca2+ i is unique to Na+-Ca2+ exchangers from Drosophila, and contrasts to the positive regulation produced by cytoplasmic Ca2+ for all other characterized Na+-Ca2+ exchangers. For CALX1.1, Ca2+ i inhibited peak and steady state currents almost equally, with the extent of inhibition being ≈80%. In comparison, the effects of regulatory Ca2+ i occurred with much higher affinity for CALX1.2, but the extent of these effects was greatly reduced (≈20–40% inhibition). For both exchangers, the effects of regulatory Ca2+ i occurred by a direct mechanism and indirectly through effects on Na+ i-induced inactivation. Our results show that regulatory Ca2+ i decreases Na+ i-induced inactivation of CALX1.2, whereas it stabilizes the Na+ i-induced inactive state of CALX1.1. These effects of Ca2+ i produce striking differences in regulation between CALX isoforms. Our findings indicate that alternative splicing may play a significant role in tailoring the regulatory profile of CALX isoforms and, possibly, other Na+-Ca2+ exchange proteins.

Keywords: Drosophila melanogaster, sodium-calcium exchange, regulation, alternative splicing

introduction

Sodium-calcium exchange plays a major role in Ca2+ homeostasis in a wide variety of tissues (Lederer et al., 1996). In cardiac muscle, for example, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is the primary mechanism for transarcolemmal Ca2+ efflux enabling cardiac relaxation (Bers, 1991). Similarly, in neuronal tissue, the exchanger may play an important role in Ca2+ efflux and, thus, excitation–secretion coupling (Blaustein et al., 1996). Calcium removal is accomplished by coupling the energy in the Na+ electrochemical gradient to the uphill movement of Ca2+. Moreover, as a reversible transporter, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger may also mediate Ca2+ entry, a role recently postulated for excitation of cardiac muscle (Leblanc and Hume, 1990; Levi et al., 1994).

Two forms of ionic regulation have been characterized extensively for the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, NCX1, using the giant, excised patch clamp technique (Hilgemann et al., 1992a , 1992b ). These regulatory processes are controlled by Na+ and Ca2+ and are most readily observed for outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents, where extracellular Ca2+ exchanges for intracellular Na+. Upon application of Na+ i to evoke an outward exchange current, the current peaks and then decays to lower, steady state levels (Hilgemann, 1990). The extent and rate of current inactivation depends upon the concentration of applied Na+ i, a process referred to as Na+ i-induced (I1)1 inactivation (Hilgemann et al., 1992a ). Calcium-induced (I2) regulation describes the stimulatory influence of cytoplasmic Ca2+ on outward exchange currents, evident at submicromolar Ca2+ i concentrations (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ). Outward exchange currents can be nearly eliminated in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i, despite approaching infinite electrochemical gradients favoring exchange (Hilgemann, 1990). Interactions are observed between Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-mediated regulatory mechanisms. Most prominent is the observation that increasing regulatory Ca2+ i can eliminate the Na+ i-induced inactivation in NCX1 (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ). Mutations targeting Ca2+ i-dependent regulation also influence the behavior of I1 inactivation and vice versa (Matsuoka et al., 1993, 1995, 1997). The physiological significance of these ionic regulatory mechanisms remains largely unknown.

The Drosophila Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, CALX1.1, also exhibits the two forms of ionic regulation observed with NCX1 (Hryshko et al., 1996). However, it is unique among members of this multigene family of transporters in that it is inhibited by cytoplasmic Ca2+. All other characterized Na+-Ca2+ exchangers are stimulated by Ca2+ i.

Sodium-calcium exchange activity is mediated by a single, integral membrane protein modeled to contain 11 transmembrane-spanning segments. Approximately one half of the protein mass resides in a large, intracellular loop located between transmembrane segments five and six (Nicoll et al., 1990; Hryshko and Philipson, 1997). Structure–function studies of NCX1 have identified discrete regions within this loop with important roles in the regulation of Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity (Matsuoka et al., 1993, 1995, 1997). For example, the XIP region near the NH2 terminus of the intracellular loop is involved in Na+ i-induced regulation of exchange activity. Mutations within this 20 amino acid region can accelerate or eliminate the I1 inactivation process (Matsuoka et al., 1997). Similarly, the regulatory Ca2+ i binding site has been localized to a large central portion of the loop where two clusters of acidic amino acids are prominent (Levitsky et al., 1994). Mutation of residues within these clusters leads to substantial reductions in the affinity for regulatory Ca2+ i (Matsuoka et al., 1995).

Recent studies have identified unique gene products and alternatively spliced isoforms of Na+-Ca2+ exchangers in a wide array of tissues. (Lee et al., 1994; Kofuji et al., 1994; Lederer et al., 1996; Quednau et al., 1997; Barnes et al., 1997). At least two splice variants of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from Drosophila melanogaster have been identified (Ruknudin et al., 1997; Schwarz and Benzer, 1997). The existence of tissue-specific, alternatively spliced isoforms, as well as unique gene products, suggests that exchange function might be specifically tailored to the Ca2+ homeostasis requirements of individual tissues. However, experimental evidence supporting this notion is lacking. In this study, we characterized the ionic regulatory properties of two splice variants from Drosophila using the giant, excised patch clamp technique and show, for the first time, that alternative splicing produces substantial differences in the characteristics of Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-mediated regulation.

methods

Preparation of Xenopus laevis Oocytes

Xenopus laevis were anaesthetized in 250 mg/liter ethyl p-aminobenzoate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in deionized ice water for 30 min, the oocytes were then removed and washed in solution A containing (mM): 88 NaCl, 15 HEPES, 2.4 NaHCO3, 1.0 KCl, 0.82 MgSO4, pH 7.6. The follicles were teased apart, the oocytes (≈5 ml) transferred to 5 ml solution A containing 80 mg collagenase (Type II; Worthington Biochemical Corp., Freehold, NJ) and incubated for 40–45 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. The oocytes were washed free of collagenase in solution B (solution A plus 0.41 mM CaCl2 and 0.3 mM Ca(NO3)2 containing 1 mg/ml BSA) (Fraction V; Sigma Chemical Co.), transferred to 5 ml of 100 mM K2HPO4 containing 1 mg/ml BSA and incubated for 11–12 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. After several washes in solution B plus BSA, defolliculated stage V and VI oocytes were selected and incubated at 16°C overnight in solution B.

Construction of Calx1.2

A λ phage partial clone containing the Calx1.2 alternative exon was kindly provided by Dr. E. Schwarz (Columbia University, New York). DNA was PCR amplified from the phage using as primers GGTGATCGACGATGACGTATTTG (forward-1) and TCGCTTTTGCCACCAGCTTG (reverse-1). The PCR product was subcloned into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, CA) and sequenced. One clone, I, contained the Calx1.2 alternative exon encoding for the sequence STHYP. There were two additional base changes in the part of the PCR product that was used to construct the full length Calx1.2. Neither change (C to T at position 1990 or A to G at position 2083) altered the predicted translation product, but the second change deleted a BglII restriction enzyme site. The BglII restriction site was reintroduced in a second round of PCR using clone I as template and forward-1 primer with reverse-2 primer (GGTCAGATCTTGAACGGG). The resulting PCR product was subcloned into pCR2.1 and sequenced. The isolated clone, 2f, contained a BglII site and no additional mutations. The full length Calx1.2 was constructed by subcloning the EagI-BglII fragment from 2f into the Calx1.1 full length clone. The resulting clone contains only the alternative exon encoding STHYP and no other amino acid changes relative to CALX1.1.

Synthesis of CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 cRNAs

Complementary DNAs encoding CALX1.1 (previously referred to as Calx; Hryshko et al., 1996) and CALX1.2 were inserted into pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, CA), linearized with NotI (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, MA), and cRNA was synthesized using T7 mMessage mMachine in vitro transcription kits (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After injection with ≈5 ng of cRNA encoding CALX1.1 or CALX1.2, oocytes were maintained at 16°C. Electrophysiological measurements were typically obtained from day 4 to 6 postinjection.

Measurement of Na+-Ca2+ Exchange Activity

Outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents were obtained using the giant, excised membrane patch technique, as described (Hilgemann, 1990; Hryshko et al., 1996; Trac et al., 1997). Borosilicate glass pipettes were pulled and polished to a final inner diameter of ≈20–30 μm and coated with a Parafilm™ (American National Can, Greenwich, CT):mineral oil mixture to enhance patch stability and reduce electrical noise. After removal of the vitellin layer by dissection, oocytes were placed in a solution containing (mM): 100 KOH, 100 MES, 20 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, pH 7.0 at 30°C with MES (morpholine ethanesulfonic acid), and GΩ seals formed via gentle suction. Membrane patches (inside-out configuration) were excised by progressive movements of the pipette tip. Rapid (i.e., ≈0.2 s) bath solution (i.e., intracellular) changes were accomplished using a custom-built, computer-controlled, 20-channel solution switcher. Hardware and software (Axopatch 200a and Axotape, respectively; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) were used for data acquisition and analysis. Pipette (i.e., extracellular) solutions contained (mM): 100 NMG (N-methyl-d-glucamine)-MES, 30 HEPES, 30 TEA (tetraethyl ammonium)-OH, 16 sulfamic acid, 8 CaCO3, 6 KOH, 0.25 ouabain, 0.1 niflumic acid, 0.1 flufenamic acid, pH 7.0 at 30°C with MES. Outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents were elicited by switching from Li+ i- to Na+ i-based bath solutions containing (mM): 100 [Na+ + Li+]-aspartate, 20 MOPS, 20 TEA-OH, 20 CsOH, 10 EGTA, 0–2.3 CaCO3, 1.0–1.5 Mg(OH)2, pH 7.0 at 30°C with MES or LiOH. Magnesium and Ca2+ were adjusted to yield free concentrations of 1.0 mM and 0–30 μM, respectively, using MAXC software (Bers et al., 1994). All experiments were conducted at 30 ± 1°C. All data reported are mean ± SEM unless indicated otherwise.

results

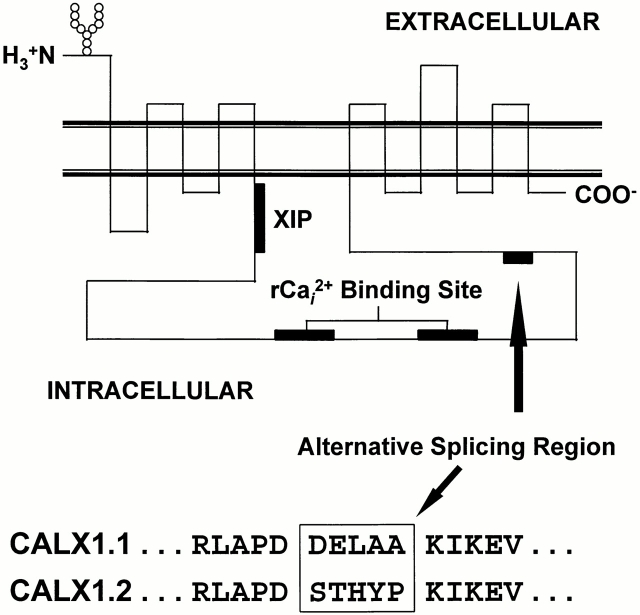

We characterized the transport and regulatory properties of two Drosophila Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoforms, CALX1.1 and CALX1.2. Putative regions of functional importance for ionic regulation (Philipson et al., 1996), analogous to those identified in NCX1, are shown in Fig. 1. The location and amino acid sequence of the alternatively spliced region for the CALX isoforms is shown. The amino acid sequences (confirmed by dideoxy sequencing) conform to those reported by Schwarz and Benzer (1997) and differ from those reported by Ruknudin et al. (1997). Specifically, Schwarz and Benzer (1997) report that the amino acid sequences of the alternative splice variants are DELAA and STHYP for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2, respectively, whereas Ruknudin et al. (1997) found that the alternative splice variants encode for the amino acid sequences DGLAA and STHYR, respectively. It is not clear whether the reported differences are due to the presence of additional splice variants or to strain differences, although the latter seems more likely.

Figure 1.

The putative topological organization of Na+-Ca2+ exchangers. Relative positions of the NH2 and COOH termini, N-linked glycosylation site, transmembrane-spanning domains, XIP region, regulatory Ca2+ i binding site, and location of the alternative splicing region are shown. The five amino acids that differ between CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 (verified by dideoxy sequencing) are shown boxed below using single-letter amino acid code.

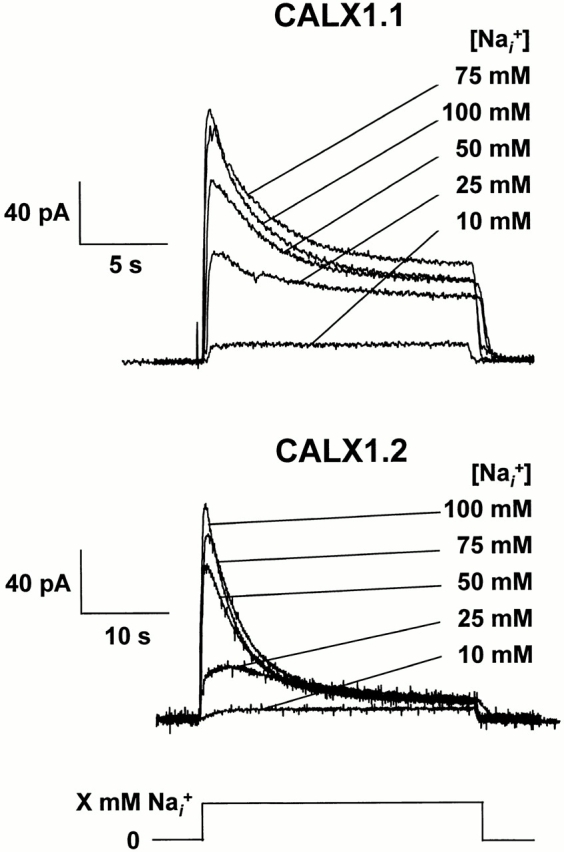

Na+ i Dependence of Na+-Ca2+ Exchange

We examined the Na+ i dependence of outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents in excised membrane patches from oocytes expressing CALX1.1 and CALX1.2. Fig. 2 shows current traces from single patches for each isoform in which currents were elicited by the application of various concentrations of Na+ i. Calcium in the pipette, to be transported, was 8 mM and all currents were activated in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i. Except for the lowest concentration of Na+ i examined (10 mM), currents rise rapidly to a peak, followed by a slow decay until steady state levels are attained. The accelerated decay of current with increasing Na+ i reflects the Na+ i-induced inactivation process (Hilgemann et al., 1992a ). Note that the extent of inactivation is greater for CALX1.2 than for CALX1.1. On the other hand, the rate of inactivation of CALX1.1 consistently exceeded that of CALX1.2. For currents activated by 100 mM Na+ i, for example, the decay rate constants, λ (see Appendix), for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 were 0.49 ± 0.19 s−1 (mean ± SD, n = 74) and 0.22 ± 0.05 s−1 (mean ± SD, n = 38), respectively. Differences in the current–voltage relationships of the CALX isoforms were not observed (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The Na+ i dependence of outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents for CALX isoforms. Overlapping current traces for both CALX isoforms are shown. Outward currents were activated in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i by application of the indicated concentrations of Na+ i, maintained until a steady state was attained, followed by switching back to a Li+ i-based bath solution.

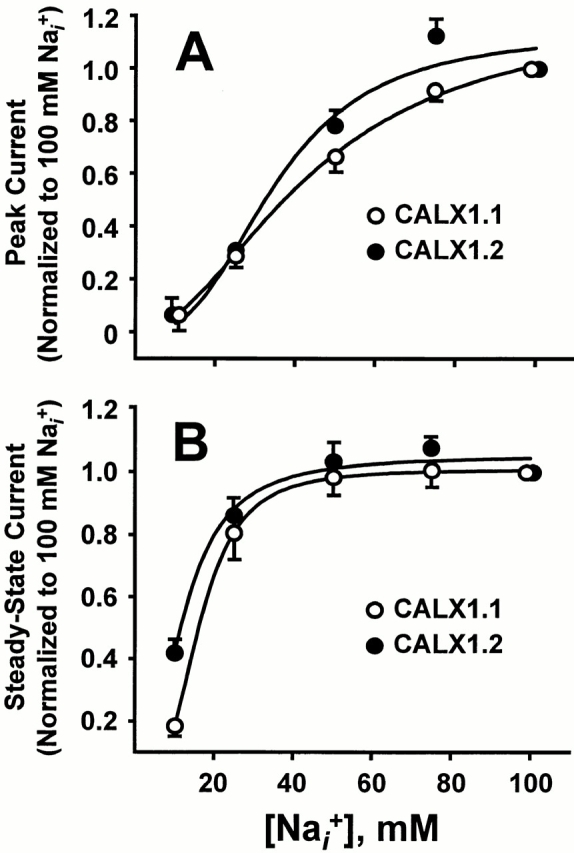

Pooled data from seven Na+ i titration experiments for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 are summarized in Fig. 3. Values for peak and steady state currents were obtained by curve-fitting individual current transients to a single-exponential function (Appendix, Eq. A4). Averaged data were normalized to peak (Fig. 3 A) or steady state (Fig. 3 B) currents obtained in response to 100 mM Na+ i, followed by curve-fitting to the Hill equation (Appendix, Eq. A7) to determine the Na+ i concentrations producing half-maximal (i.e., K d values) peak and steady state exchange currents. The apparent values for peak K d were essentially the same for both exchangers (35.2 ± 2.3 and 34.2 ± 1.1 mM for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2, respectively), whereas the steady state K d value for CALX1.2 was slightly lower than that of CALX1.1 (16.6 ± 1.0 and 11.6 ± 0.7 mM for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2, respectively).

Figure 3.

The Na+ i dependence of peak and steady state outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents for CALX isoforms. Data from seven patches for each exchanger were normalized to the peak (A) and steady state (B) currents generated by application of 100 mM Na+ i in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i. Data were “best-fit” to the Hill equation by least-squares regression analysis.

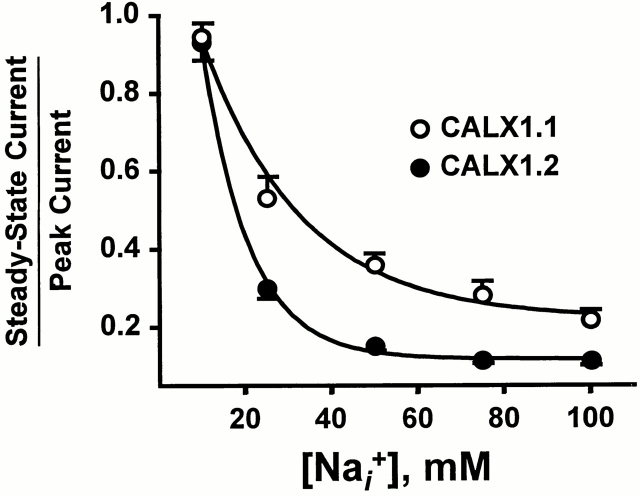

The most obvious difference between the CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 responses to Na+ i application was the extent to which they underwent I1 inactivation (Fig. 2). This is quantitated in Fig. 4, where the ratios of steady state to peak exchange currents, Fss, are plotted against Na+ i (see also Fig. 2). The ratio, Fss, serves as a measure of the extent of Na+ i-dependent inactivation (see Appendix). For all Na+ i concentrations above 10 mM, the extent of inactivation was clearly greater for CALX1.2 than for CALX1.1. For example, for currents obtained in response to 100 mM Na+ i application, Fss values for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 were 0.26 ± 0.06 (mean ± SD, n = 74) and 0.14 ± 0.04 (mean ± SD, n = 38). In the simplest case, these differences might reflect accelerated entry into, or impeded exit from, the Na+ i-induced inactive state for CALX1.2 as compared with CALX1.1.

Figure 4.

The Na+ i dependence of Fss, the ratio of steady state to peak currents, for CALX isoforms. The Na+ i dependence of the ratio of steady state to peak outward currents for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 is shown. Values are mean ± SEM of six to seven determinations for CALX1.1 and four to six determinations for CALX1.2.

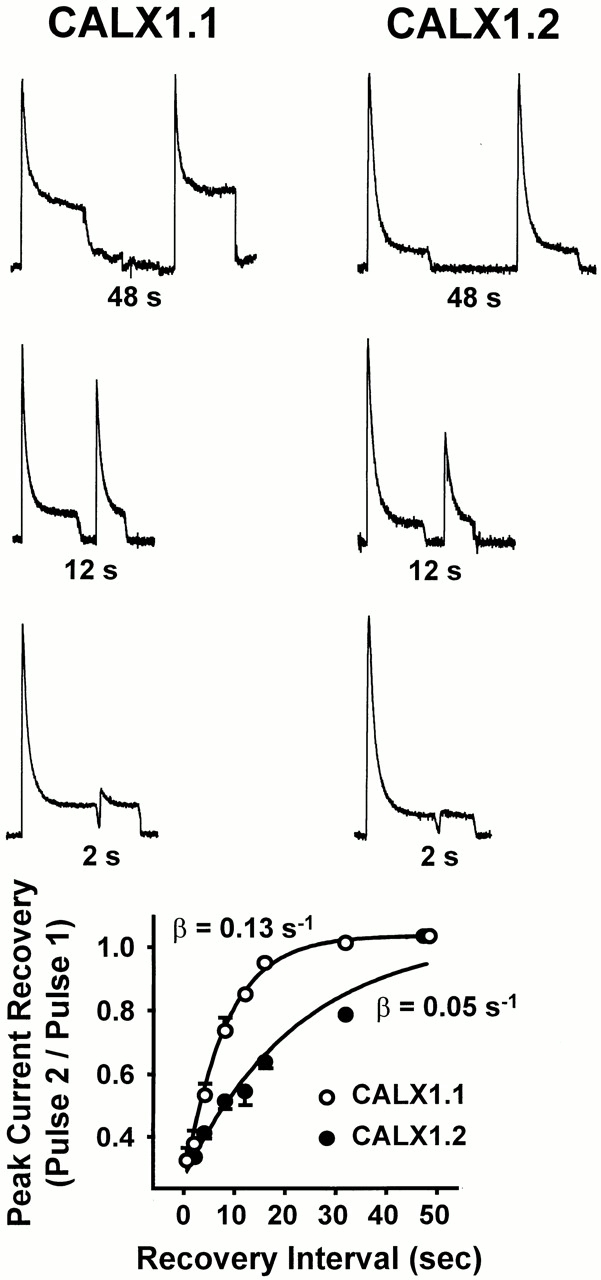

To further investigate the differences in Na+ i-induced inactivation between the two CALX isoforms, we performed paired-pulse experiments to determine the rates of recovery from the I1 inactive state. Typical traces from experiments of this type are shown in Fig. 5 (top three panels). Currents were activated by applying 100 mM Na+ i until a steady state current level was achieved. Intracellular Na+ was then removed for a variable recovery period (0.5–48 s) before the delivery of a second pulse of 100 mM Na+ i. The magnitude of the second peak reflects the extent to which the exchanger population has recovered from Na+ i-induced inactivation, analogous to paired-pulse experiments for ion channels (Hille et al., 1984; Hilgemann et al., 1992a ). Note that complete recovery is observed at longer intervals (e.g., 48 s), whereas little to no recovery is evident at shorter intervals (e.g., 2 s). Fig. 5 (bottom) summarizes data obtained from 13 patches of CALX1.1 and 5 of CALX1.2 spanning 0.5–48-s recovery intervals. Data were curve-fitted to Eq. A6 (see Appendix) and the recovery rate constants, β, were determined as 0.13 ± 0.01 s−1 and 0.05 ± 0.01 s−1 for CALX1.1 and CALX1.2, respectively. These results show an approximately threefold reduction in the rate of recovery from I1 inactivation for CALX1.2 as compared with CALX1.1, indicating greater stability of the I1 inactive state of CALX1.2. As we have no direct experimental means of obtaining discrete values for α or f 3ni, we do not report values for entry into the I1 inactive state. A complete description of the rate constants α, β, and λ, and the analytical approach used, is given in Appendix.

Figure 5.

The rate of recovery from Na+ i-induced inactivation of peak outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents for CALX isoforms. The top three panels show representative current traces obtained from paired-pulse experiments with 48-, 12-, and 2-s recovery intervals. Currents were activated by 100 mM Na+ i, in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i, and maintained until a steady state level was obtained (i.e., Pulse 1). Current was then deactivated by rapidly switching to 100 mM Li+ i. After a recovery period of 0.5–48 s, a second pulse of 100 mM Na+ i was delivered (i.e., Pulse 2). The bottom summarizes data obtained from 13 patches of CALX1.1 and 5 of CALX1.2 spanning recovery intervals of 0.5–48 s. Data were “best-fit” to a single-exponential function via least-squares regression analysis.

Ca2+ i Regulation of Na+-Ca2+ Exchange Currents

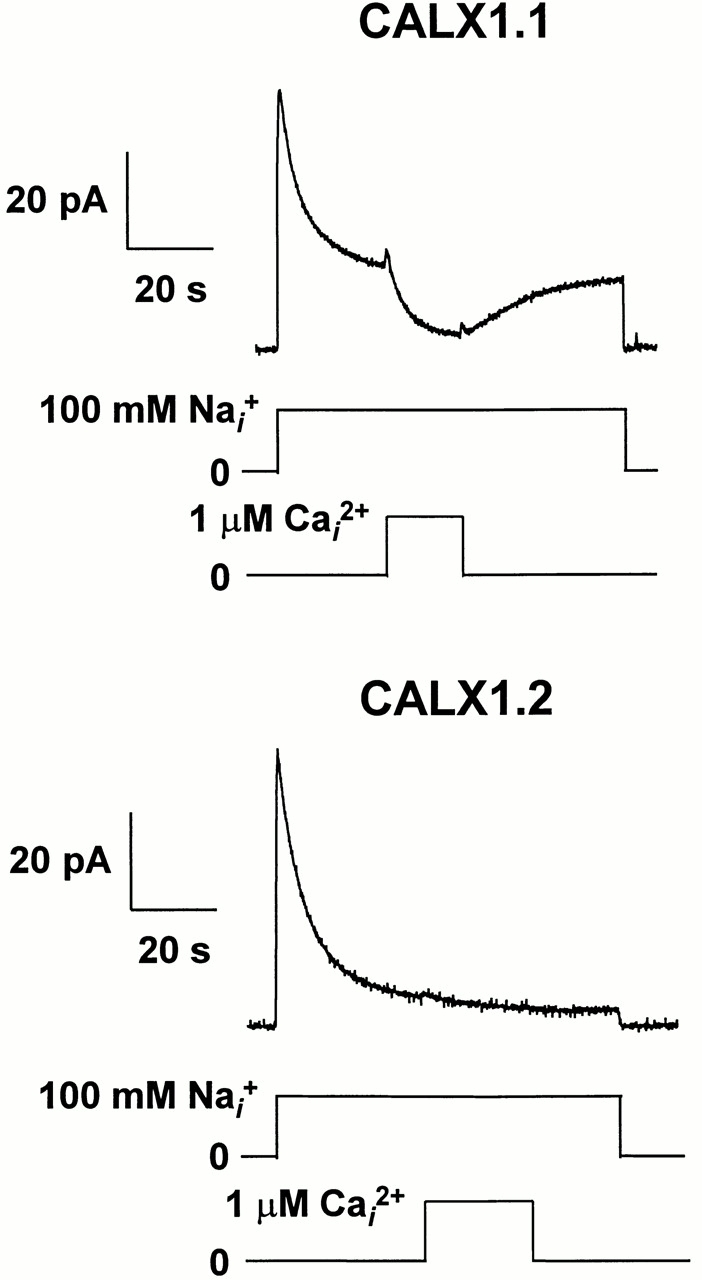

All native Na+-Ca2+ exchangers examined to date are influenced by regulatory Ca2+ i. So far, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from Drosophila, CALX1.1, is unique in exhibiting a negative regulatory influence of cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Hryshko et al., 1996). Here, we show that both isoforms of the Drosophila Na+-Ca2+ exchanger exhibit negative regulation by Ca2+ i. However, there are substantial differences in the nature of this inhibition. In Fig. 6, outward currents were activated by applying 100 mM Na+ i. After steady state current levels were achieved, 1 μM regulatory Ca2+ i was applied, and then removed. For CALX1.1, the application of regulatory Ca2+ i leads to a substantial inhibition of current that then recovers to steady state levels upon Ca2+ i removal. In contrast, regulatory Ca2+ i is nearly without effect on steady state currents from CALX1.2. Nine patches for CALX1.2 were studied using this protocol and we observed small increases or decreases (≈5%) or no change in response to the application of 1 μM Ca2+ i. In contrast, the inhibition observed with CALX1.1 is typical for 41 patches. These traces show striking differences in the response to regulatory Ca2+ i between the two isoforms. Nevertheless, both exchangers are inhibited by regulatory Ca2+ i, as described below.

Figure 6.

The effect of regulatory Ca2+ i on steady state Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents for CALX isoforms. Representative data are shown illustrating outward currents generated by CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 in response to the application of 100 mM Na+ i. Regulatory Ca2+ i (1 μM) was applied in the middle of the current record (near steady state), and then removed as indicated. Note that currents are substantially inhibited by regulatory Ca2+ i for CALX1.1 but not for CALX1.2.

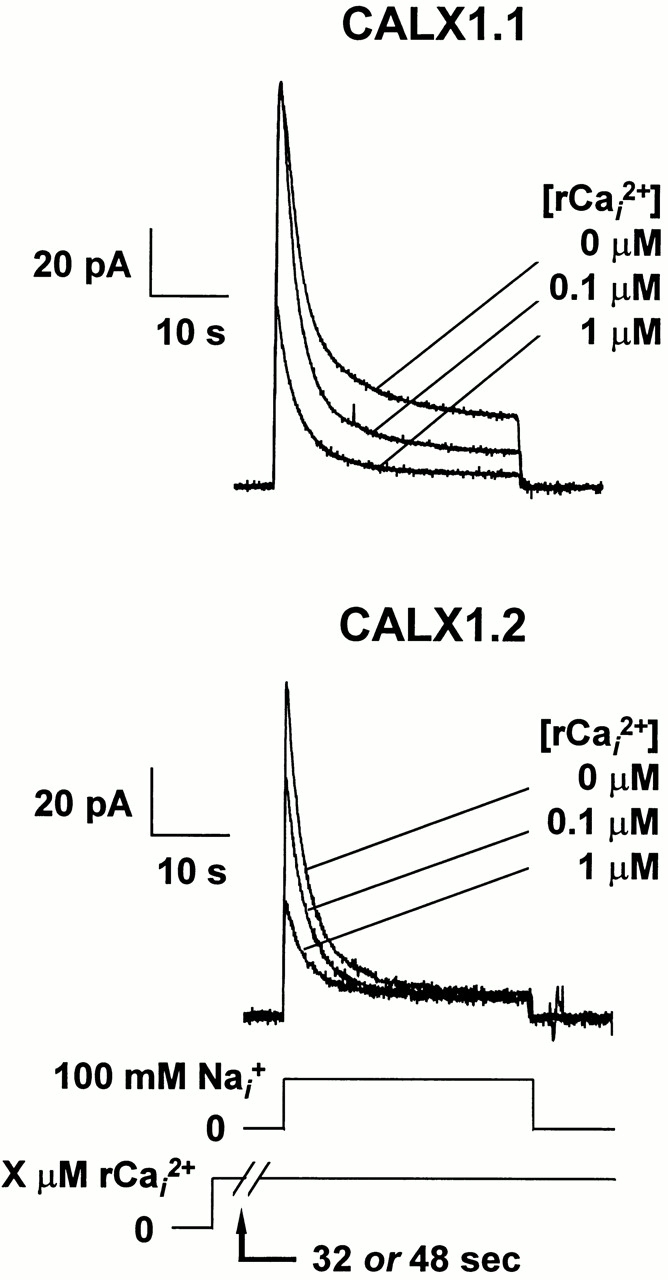

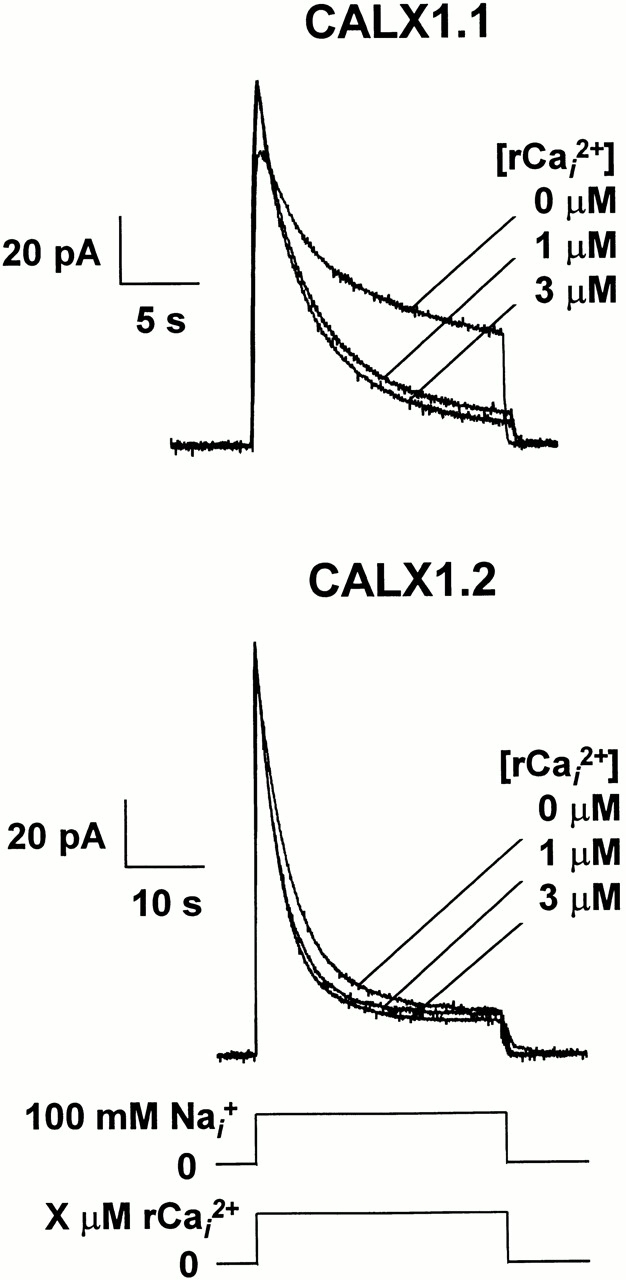

The influence of regulatory Ca2+ i on peak current generated by CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 is shown in Fig. 7. Currents were activated by the rapid application of 100 mM Na+ i in the absence or presence of various concentrations of regulatory Ca2+ i. Regulatory Ca2+ i at the indicated concentrations was present before and during current activation, and transported Ca2+ o in the pipette was constant at 8 mM. Note that both exchangers exhibit a decrease in current magnitude in the presence of regulatory Ca2+ i (i.e., negative Ca2+ i regulation). However, two major differences between these isoforms can be seen from the current traces. First, Ca2+ i exhibits pronounced effects on both peak and steady state currents for CALX1.1, as previously reported (Hryshko et al., 1996). In contrast, the effects of regulatory Ca2+ i are prominent on peak currents but much less pronounced for steady state currents for CALX1.2. Second, though less obvious from these traces, is the observation that regulatory Ca2+ i exerts effects at much lower concentrations for CALX1.2 than for CALX1.1. These relationships are most apparent from the pooled data shown below.

Figure 7.

The effect of preincubation with regulatory Ca2+ i on Na+-Ca2+ exchange current transients for CALX isoforms. Representative data are shown for outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents activated by 100 mM Na+ i. Regulatory Ca2+ at the indicated concentrations was present before and during current activation.

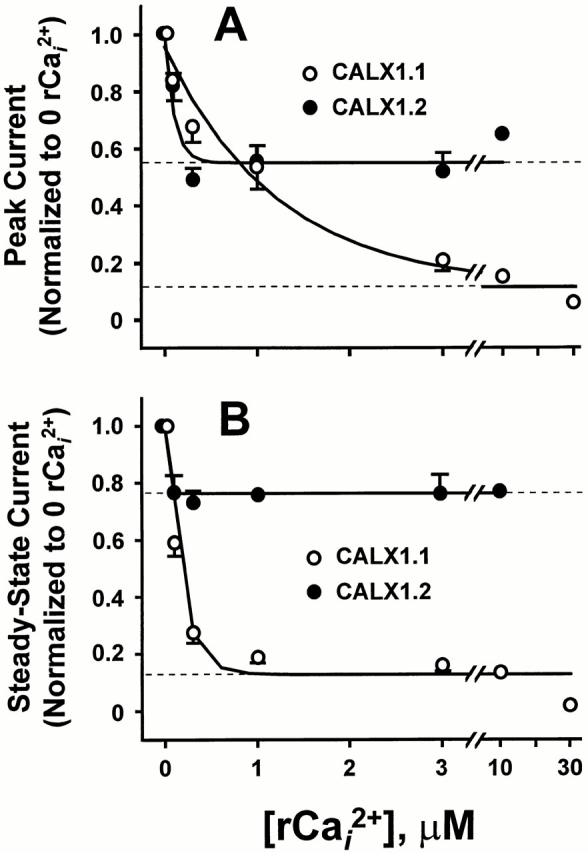

Fig. 8 illustrates results from 10 patches for CALX1.1 and 8 for CALX1.2. Peak and steady state currents were normalized to the values obtained in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i. Note that for peak currents, the affinity for Ca2+ i regulation is greater for CALX1.2, but the extent of inhibition is considerably less. In contrast, CALX1.1 shows lower affinity but greater efficiency for negative Ca2+ i regulation. For steady state currents, large differences in the extent of negative Ca2+ i regulation are observed between the splice variants. The affinity for negative Ca2+ i regulation is also higher for CALX1.2, with the effect being essentially complete at 300 nM Ca2+ i. This high affinity, low efficiency effect partially accounts for the minimal influence of regulatory Ca2+ i application shown in Fig. 5 above. In contrast, the lower affinity, higher efficiency effects of regulatory Ca2+ i on CALX1.1 are seen in this graph and Fig. 5.

Figure 8.

The effect of regulatory Ca2+ i on peak and steady state Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents for CALX isoforms. Peak (A) and steady state (B) currents for CALX1.1 (10 patches) and for CALX1.2 (8 patches) generated in experiments in which giant patches were incubated with the indicated concentrations of regulatory Ca2+ i (rCai 2+), as in Fig. 7, were normalized to the peak or steady state currents obtained in the absence of rCa2+ i. Values are mean ± SEM of four to six determinations for CALX1.1 (except at 10 and 30 μM rCai 2+, which are from one and two determinations, respectively) and four to eight for CALX1.2 (except at 10 μM rCai 2+, which is from a single determination). Data were “best-fit” to a two-parameter, single-exponential function via least-squares regression analysis. Dotted lines represent the estimated minimum values of peak and steady state currents.

To gain further insight into these differences, we examined the influence of regulatory Ca2+ i using two additional protocols. First, we examined how regulatory Ca2+ i influenced outward currents if applied at the same time as Na+ i to activate the current. That is, regulatory Ca2+ i was absent before current activation. Under these conditions, the exchanger population should be maximally available as the inhibitory influences of both Na+ i and Ca2+ i are absent before current activation. For both exchangers, this appeared to be the case, as shown in Fig. 9. Here, both CALX isoforms show similar peak currents, independent of the concentration of regulatory Ca2+ i applied during the pulse. That is, the initial current peak reflects the maximal number of exchangers producing current before inhibition by regulatory Ca2+ i. The resultant waveforms then slowly decay to steady state values, appropriate for the concentration of regulatory Ca2+ i present. This indicates that negative regulation by Ca2+ i for Drosophila exchangers is a relatively slow process. In contrast, activation of exchange current by regulatory Ca2+ i is extremely rapid (i.e., within solution switch time of ≈0.2 s) for the cardiac exchanger, NCX1 (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ). Also, the large difference between CALX1.1 and CALX1.2 for the effects of regulatory Ca2+ i on steady state currents is apparent.

Figure 9.

The effect of regulatory Ca2+ i on Na+-Ca2+ exchange current transients for CALX isoforms. Representative data are shown for outward Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents activated by 100 mM Na+ i. Regulatory Ca2+ at the indicated concentrations was present during current activation only.

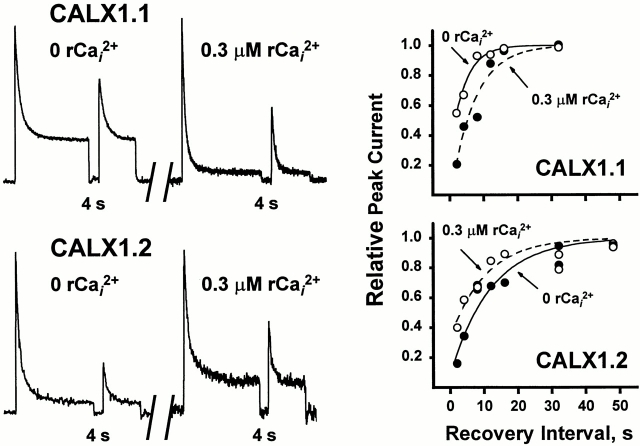

The second approach investigated the influence of Ca2+ i in paired-pulse experiments to determine how regulatory Ca2+ i influenced recovery from Na+ i-induced inactivation. Fig. 10 (left) shows paired pulses for 4-s recovery intervals, with or without regulatory Ca2+ i present, for both CALX isoforms. For ease of comparison, currents were normalized to the height of the first peak of each pair. This normalization obscures the inhibitory effects of regulatory Ca2+ i but allows for simple comparison of recovery behavior. All currents were activated by 100 mM Na+ i and regulatory Ca2+ i was either absent or present at 300 nM. For CALX1.1, the rate of recovery is clearly decreased when regulatory Ca2+ i is present. This is exactly opposite to that observed for NCX1, where increasing regulatory Ca2+ i accelerates I1 recovery (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ; data not shown). Recovery from Na+ i-induced inactivation for CALX1.2 is increased in the presence of regulatory Ca2+ i. Thus, the behavior of CALX1.2 is directionally similar to that of NCX1 and opposite to that of CALX1.1.

Figure 10.

The effect of regulatory Ca2+ i on rates of recovery from Na+ i-induced inactivation for CALX isoforms. (left) Outward Na+-Ca2+ current traces were obtained from a single patch of each isoform in paired-pulse experiments with 4-s recovery intervals (see Fig. 5) in which the effects of 0 and 300 nM regulatory Ca2+ i were assessed. The condition of 0 or 300 nM Ca2+ i was initiated before delivery of the first pulse of 100 mM Na+ i, and maintained throughout activation, recovery, and activation of the second pulse. Currents were normalized to the height of the first, control Na+ i pulse to allow for simple comparison of recovery behavior. (right) Graphs summarize the data from these two patches obtained for the full range of recovery intervals (i.e., 0.5–48 s) in the absence and presence of 300 nM Ca2+ i. Data were normalized to the height of the first peak of each pair and “best-fit” to a single-exponential function (Eq. A6) via least-squares regression analysis.

This effect of regulatory Ca2+ i is shown for a range of recovery intervals for the CALX isoforms (Fig. 10, right). The results are from single patches where the complete range of recovery intervals were obtained in the absence and presence of 300 nM regulatory Ca2+ i. Although we could not routinely complete the entire protocol at two Ca2+ i concentrations (which requires that the giant membrane patch remains viable for 30– 45 min), we observed this increase in recovery rate for CALX1.2 in five patches and the decrease for CALX1.1 recovery in three patches. Thus, CALX1.2 responds oppositely to CALX1.1 with respect to the influence of Ca2+ i on recovery from I1 inactivation. This behavior, in conjunction with the diminished I2 effects (Figs. 7 and 8), provides a reasonable account as to why regulatory Ca2+ i has virtually no effect on CALX1.2 steady state currents (Fig. 6). For CALX1.2, the small decrease in current mediated by negative Ca2+ i regulation is offset by a reduction in Na+ i-induced inactivation.

discussion

We have shown that two alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from Drosophila exhibit substantial differences in ionic regulation by Na+ i and Ca2+ i. While numerous splice variants have been identified for Na+-Ca2+ exchangers using molecular biological techniques, this is the first demonstration of functional differences in ionic regulatory properties between two such isoforms. That ionic regulatory mechanisms have been targeted by nature for modification is suggestive of the importance of these mechanisms in tissue-specific physiological function.

Na+ i-induced Inactivation

Sodium-induced inactivation of Na+-Ca2+ exchange currents is a process that appears to be analogous to inactivation of ion channels (Hilgemann et al., 1992a ). In the simplest case, this inactivation reflects removal of a fraction of the population of exchangers available for transport (see Appendix). Evidence supporting altered transport properties for the entire population of exchangers is lacking (Hilgemann et al., 1992a ), and recent studies indicate that exchangers partition between fully active and inactive states (Hilgemann, 1996). Consequently, steady state current levels occur when entry into and exit from the inactive state are equal. As described by Hilgemann et al. (1992a), entry into the I1 inactive state occurs from the 3 Na+ i-loaded form of the exchanger with transport sites facing the cytoplasmic side. Elevations in cytoplasmic Na+ augment inactivation by increasing the fraction of exchangers in the 3 Na+ i-bound configuration. We have used this model of I1 inactivation to interpret differences in Na+ i-induced inactivation between the two Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoforms from Drosophila.

Compared with CALX1.1, CALX1.2 exhibits substantially greater Na+ i-dependent inactivation based on all criteria examined. We have used Fss, the ratio of steady state to peak current, as a measure of the extent of steady state inactivation. This value reflects the population of exchangers contributing to steady state current compared with that producing peak current. There is a substantial decrease in steady state current levels for CALX1.2 as compared with CALX1.1. These changes in Fss could reflect either an increased entry rate into, or a decreased recovery rate from, the I1 inactive state. To discriminate between these possibilities, we conducted paired-pulse experiments. Within the framework of the I1 inactivation model, these experiments isolate the rate of recovery from inactivation since Na+ i is absent during recovery periods and, therefore, entry into the I1 state cannot occur (see Appendix). We observed that the rate of recovery from inactivation is decreased nearly threefold for CALX1.2, indicating that the stability of the I1 inactive configuration is much greater for CALX1.2 than for CALX1.1. Although the exact mechanism of Na+ i-induced inactivation remains unknown, a reasonable picture is beginning to emerge based on structure–function studies and electrophysiological analyses. Mutations within the XIP region of NCX1 lead to marked changes in Na+ i-dependent inactivation that can either accelerate or eliminate I1 inactivation (Matsuoka et al., 1997). Our initial structure–function studies for CALX1.1 have revealed that analogous mutations produce regulatory phenotypes analogous to those of NCX1 (Dyck et al., 1997). Both NCX1 and CALX1.1 are inhibited by the exogenous application of the peptide inhibitor, XIP (Li et al., 1991; Hryshko et al., 1996). We speculate that exogenous application of XIP inhibits exchange currents by mimicking the inactivation process. By analogy to mechanisms well-described for ion channels, the XIP region may represent an inhibitory domain that plays a prominent role in the transition from active to inactive states of the exchanger. Electrophysiological studies of Na+ i-dependent inactivation strongly support the notion that inactivation reflects such a transition (Hilgemann et al., 1992b; Hilgemann, 1996). The present data indicate that the alternatively spliced region serves a role in establishing the extent and rapidity of Na+ i- dependent inactivation, since marked changes in this property are observed between isoforms. It remains to be determined how this region influences Na+ i-dependent inactivation.

Ca2+ i-dependent Regulation

Calcium-dependent regulation of the cardiac exchanger, NCX1, appears as the augmentation of outward exchange currents in response to the application of micromolar levels of cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Hilgemann, 1990; Hilgemann et al., 1992b ; Matsuoka et al., 1995). Regulatory Ca2+ i affects at least two processes. First, it strongly influences Na+ i-dependent inactivation. At higher Ca2+ i concentrations (e.g., 10 μM), Na+ i-dependent inactivation can be eliminated and current traces no longer exhibit decay. Second, regulatory Ca2+ i activates the exchanger population directly. Removal of Ca2+ i favors a slow (i.e., seconds) entry into the I2 inactive state. Conversely, exit from the I2 state by addition of regulatory Ca2+ i is extremely rapid and occurs within solution switch times for NCX1.

Structure–function studies (using mutagenesis and electrophysiology experiments) and biochemical studies (using fusion protein and 45Ca-overlay experiments) have identified a protein region comprising the high affinity, regulatory Ca2+ i binding site of NCX1 (Levitsky et al., 1994; Matsuoka et al., 1995). This region encompasses amino acids 371–508 and is modeled to reside near the middle of the large intracellular loop between transmembrane segments five and six. Prominent within this region are two well-conserved, highly acidic clusters of amino acids. Mutations within these acidic clusters lead to significant alterations in the affinity for Ca2+ i regulation in both NCX1 and CALX1.1, as assessed by the giant excised patch technique (Matsuoka et al., 1995; Dyck et al., 1997).

The two, alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from Drosophila are unique among all characterized mammalian exchangers in that they exhibit negative regulation by cytoplasmic Ca2+ i. Alternative splicing does not change the negative regulatory phenotype, although considerable differences are observed in the properties of Ca2+ i regulation. Specifically, CALX1.1 shows considerably greater inhibition by regulatory Ca2+ i, albeit at higher concentrations. While CALX1.2 shows high affinity for Ca2+ i regulation, the extent of inhibition is small. Maximum inhibition for both steady state and peak currents is only ≈20–40% as compared with >80% for CALX1.1. This difference is most obvious for steady state currents that show only marginal inhibition by Ca2+ i for CALX1.2. These data indicate that alternative splicing influences both Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent regulatory mechanisms.

Interactions between Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent Regulation

The interactions between Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent regulation are best described for the native Na+-Ca2+ exchanger from measurements of sarcolemmal membrane “blebs” (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ). However, this interaction is also evident using the Xenopus oocyte expression system and the cloned cardiac exchanger, NCX1 (Matsuoka et al., 1995; Trac et al., 1996). In both assay systems, it was observed that regulatory Ca2+ i could completely eliminate Na+ i-dependent inactivation and that the extent of Na+ i-dependent inactivation was graded progressively by regulatory Ca2+ i levels. From extensive modeling, it appears that regulatory Ca2+ i accelerates exit from and reduces entry into the I1 inactive state for NCX1 (Hilgemann et al., 1992b ). Structurally, it remains unknown how this interaction occurs. In this study, we examined the interaction between Na+ i-dependent inactivation and regulatory Ca2+ i using Ca2+ i preincubation and paired-pulse experiments. Surprisingly, we observed exactly opposite results for CALX1.1 than those reported for NCX1. That is, Ca2+ i stabilized the I1 inactive state of CALX1.1. Also, both CALX isoforms react to Ca2+ i application slowly (over seconds), whereas NCX1 responds within solution switch times. Furthermore, Na+ i-dependent inactivation for CALX1.2 was alleviated by the addition of regulatory Ca2+ i, similar to NCX1 and opposite to CALX1.1. These striking differences between exchangers may prove important towards understanding the transduction of the regulatory Ca2+ binding signal.

Significance

Our results indicate that Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent regulatory mechanisms are altered in the alternatively spliced Na+-Ca2+ exchanger isoforms from Drosophila. This is the first demonstration of alterations in regulatory mechanisms for splice variants of Na+-Ca2+ exchangers. Our data suggest that alternative splicing may provide an efficient means of modifying behavior, possibly to fulfill specific tissue requirements. That alternative splicing alters regulatory properties implies that these mechanisms may be important in the physiological function of the multi-gene family of Na+-Ca2+ exchangers. We have also identified differences in ionic regulation between tissue-specific, alternatively spliced mammalian exchangers from kidney, heart, and brain (Hnatowich, M., C. Dyck, A. Omelchenko, B. Quednau, K.D. Philipson, and L.V. Hryshko, manuscript in preparation). These data provide increasing support for the possibility that ionic regulation fulfills a role in physiological Na+-Ca2+ exchange function. Alternative splicing may contribute to this role.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada, the Manitoba Health Research Council, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (to L.V. Hryshko) and by National Institutes of Health grants HL-48509 and HL-49101 (to K.D. Philipson and D.A. Nicoll). C. Dyck is supported by a studentship from the Manitoba Health Research Council and L.V. Hryshko by a scholarship from the Medical Research Council of Canada.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- I1

Na+ i-induced

- I2

Ca2+ i-induced

appendix

Following the two-step Na+ i-dependent inactivation model proposed by Hilgemann et al. (1992a , 1992b ), we consider that entry into the I1 inactive state is related to the fraction of exchangers loaded with 3 Na+ i, termed f 3ni, and recovery from I1 inactivation is a simple, time-dependent (i.e., first-order) process. The fraction, χ, of the entire exchanger population being in an active state is given by the equation:

|

A1 |

where α is an inactivation rate constant and β is a recovery (from I1 inactivation) rate constant. For CALX isoforms, the maximal population of active exchangers, χo, is assumed to be available only in the absence of regulatory Ca2+ i and before Na+ i application. Under these conditions, entry into Na+ i- and Ca2+ i-dependent inactive states cannot occur. Thus, with CALX isoforms, it is possible to study Na+ i-dependent inactivation in the absence of modulating influences by regulatory Ca2+ i. The solution to Eq. A1 is:

|

A2 |

where λ = αf 3ni + β, is a current decay rate constant, and χ∞• = β/λ, is the steady state fraction of active exchangers.

Since the rate of inactivation is much slower (i.e., seconds) than the transport rate and the rate at which the Na+ i concentration can be altered (i.e., ≈0.2 s; Collins et al., 1992), all current transients will reflect the time-dependent process of inactivation and recovery. Therefore, the expressions for the peak, I peak, and steady state currents, I ss, are given by:

|

A3 |

where N is the number of exchangers and i is the elementary current of the fully active individual Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. An expression for the time dependence of outward exchange current, reflecting Na+ i-dependent changes in the population of active exchangers, is obtained by combining Eqs. A2 and A3 to give:

|

A4 |

This equation was used for fitting current transients obtained from single-pulse experiments.

The ratio of steady state current to the initial peak current, F ss, can serve as a measure of exchange current inactivation. The smaller the value of F ss, the greater the extent of inactivation. In terms of the current decay rate constant, λ, and the recovery from inactivation rate constant, β, we can write (from Eqs. A2 and A3):

|

A5 |

The transition between inactive and active exchanger states occurring during the recovery period of paired-pulse experiments can be also described by Eq. A1, with the only difference being that entry into the I1 inactive state cannot occur since f 3ni = 0 at [Na+]i = 0. Therefore, the dependence of peak current during the second pulse, I t R peak on the recovery interval, t R, reads:

|

A6 |

Here I peak corresponds to the peak current during the first Na+ i application (i.e., after full recovery from I1 inactivation after ≈48 s). It can be seen from Eq. A6 that paired-pulse experiments reveal the rate constant of recovery, β, alone, while the current decay rate, λ, obtained from single-pulse experiments, represents the sum of both inactivation, α, and recovery, β, rate constants.

Half-saturating Na+ i concentrations, K d, indicative of the apparent Na+ i affinities of Na+-Ca2+ exchange for peak and steady state currents (both designated in Eq. A7 as I), were obtained by fitting the Na+ i dependence of the corresponding currents to the Hill equation, as follows:

|

A7 |

where [Na i] is the Na+ i concentration, I max is the fitted peak or steady state exchange current at [Na i] → ∞•, and X is the Hill coefficient.

references

- Barnes KV, Cheng G, Dawson MM, Menick DR. Cloning of cardiac, kidney, and brain promoters of the feline ncx1gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11510–11517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers, D.M. 1991. Excitation–Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Kluwer Academic Publications, London, UK. 71–92.

- Bers DM, Patton CW, Nuccitelli R. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+buffers. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;40:3–29. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP, Fontana G, Rogowski RS. The Na+– Ca2+exchanger in rat brain synaptosomes: kinetics and regulation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;779:300–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Somlyo A, Hilgemann DW. The giant cardiac membrane patch method: stimulation of outward Na/Ca exchange current by MgATP. J Physiol (Camb) 1992;454:37–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck C, Buchko J, Hnatowich M, Trac M, Hryshko LV. Structure-function studies of Calx, the Na+–Ca2+exchanger from Drosophila, reveal conservation of regulatory sites. Biophys J. 1997;72:63a. . (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW. Regulation and deregulation of cardiac Na+–Ca2+exchange in giant excised sarcolemmal membrane patches. Nature. 1990;344:242–245. doi: 10.1038/344242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW. Unitary cardiac Na+, Ca2+exchange current magnitudes determined from channel-like noise and charge movements of ion transport. Biophys J. 1996;71:759–768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79275-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange: sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 1992a;100:905–932. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Collins A, Matsuoka S. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange: secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J Gen Physiol. 1992b;100:933–961. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 1984. Ionic Channels of Exitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates Inc. Sunderland, MA.

- Hryshko LV, Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, Weiss JN, Schwarz EM, Benzer S, Philipson KD. Anomolous regulation of the Drosophila Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by Ca2+ . J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:67–74. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryshko LV, Philipson KD. Na+-Ca2+exchange: recent advances. Basic Res Cardiol. 1997;92:45–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00794067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji P, Lederer WJ, Schulze DH. Mutually exclusive and cassette exons underlie alternatively spliced isoforms of the Na/Ca exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5145–5149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Hume JR. Sodium current-induced release of calcium from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1990;248:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.2158146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer WJ, He S, Luo S, DuBell W, Kofuji P, Kieval R, Neubauer CF, Ruknudin A, Cheng H, Cannel MB, Rogers TB, Schulze DH, The molecular biology of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and its functional roles in heart, smooth muscle cells, neurons, glia, lymphocytes, and nonexcitable cells Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;779:7–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Yu ASL, Lytton J. Tissue-specific expression of Na+-Ca2+exchanger isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14849–14852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi AJ, Spitzer KW, Kohmoto O, Bridge JHB. Depolarization-induced Ca entry via Na-Ca exchange triggers SR release in guinea pig cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1422–H1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky DO, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Identification of the high affinity Ca2+-binding domain of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22847–22852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Nicoll DA, Collins A, Hilgemann DW, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Weiss JN, Tomich JM, Philipson KD. Identification of a peptide inhibitor of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1014–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, He Z, Philipson KD. Regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+exchanger by the endogenous XIP region. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:1–14. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, Hryshko LV, Levitsky DO, Weiss JN, Philipson KD. Regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by Ca2+: mutational analysis of the Ca2+binding domain. J Gen Physol. 1995;105:403–420. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, Reilly RF, Hilgemann DW, Philipson KD. Initial localization of regulatory regions of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+exchanger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3870–3874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll DA, Longoni S, Philipson KD. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+exchanger. Science. 1990;250:561–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1700476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson KD, Nicoll DA, Matsuoka S, Hryshko LV, Levitsky DO, Weiss JN. Molecular regulation of the Na+-Ca2+exchanger. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;779:20–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednau BD, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Tissue specificity and alternative splicing of the Na+/Ca2+exchanger isoforms NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 in rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1250–C1261. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruknudin A, Valdivia C, Kofuji P, Lederer WJ, Schulze DH. Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in Drosophila: cloning, expression, and transport differences. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C257–C265. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EM, Benzer S. Calx, a Na-Ca exchanger gene of Drosophila melanogaster. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10249–10254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trac M, Dyck C, Hnatowich M, Omelchenko A, Hryshko LV. Transport and regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: comparison between Ca2+ and Ba2+ . J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:361–369. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]