Abstract

X-ray diffraction data were collected from frozen crystals (100°K) of the KcsA K+ channel equilibrated with solutions containing barium chloride. Difference electron density maps (Fbarium − Fnative, 5.0 Å resolution) show that Ba2+ resides at a single location within the selectivity filter. The Ba2+ blocking site corresponds to the internal aspect (adjacent to the central cavity) of the “inner ion” position where an alkali metal cation is found in the absence of the blocking Ba2+ ion. The location of Ba2+ with respect to Rb+ ions in the pore is in good agreement with the findings on the functional interaction of Ba2+ with K+ (and Rb+) in Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Neyton, J., and C. Miller. 1988. J. Gen. Physiol. 92:549–567). Taken together, these structural and functional data imply that at physiological ion concentrations a third ion may interact with two ions in the selectivity filter, perhaps by entering from one side and displacing an ion on the opposite side.

Keywords: potassium channel, barium, ion channel, ion selectivity, ion conduction

INTRODUCTION

To a K+ channel, the alkaline earth metal Ba2+ is like a divalent K+ ion. Barium's size allows it to fit into the selectivity filter, but its charge apparently causes it to bind too tightly. When it is bound in the filter, Ba2+ prevents the rapid flow of K+.

The K+ channel inhibitory properties of Ba2+ have been analyzed in detail (Armstrong and Taylor 1980; Eaton and Brodwick 1980; Armstrong et al. 1982; Vergara and Latorre 1983; Benham et al. 1985; Miller 1987, Neyton and Miller 1988a,Neyton and Miller 1988b; Zhou et al. 1996; Harris et al. 1998; Vergara et al. 1999). Neyton and Miller 1988a,Neyton and Miller 1988b showed through single channel studies of Ca2+-activated K+ channels that Ba2+ inhibition is sensitive to the presence of K+ ions in the pore. They observed that the mean blocking dwell time of Ba2+ depended on the K+ concentration on both sides of the membrane. Low external (extracellular side of the membrane) K+ ion concentrations (0.01 mM) tended to prevent Ba2+ from exiting to the external side, while higher concentrations (500 mM) actually caused Ba2+ to dissociate more rapidly to the internal side (intracellular side of the membrane) as if it could be pushed through. These phenomena were attributed to the presence of two K+ ion sites located between the blocking Ba2+ ion and the external solution. The presence of K+ at the first of these sites, termed the external lock-in site, would obstruct barium's outward movement. Occupancy of both sites by K+ (the site closest to Ba2+ was termed the enhancement site) would destabilize Ba2+ and speed its exit to the inside. By evaluating a series of different ions, the lock-in and enhancement sites were shown to be highly selective for alkali metal ions that permeate K+ channels such as K+ and Rb+, but not Na+. An additional monovalent ion site, termed the internal lock-in site, was hypothesized to lie between the position of Ba2+ and the internal entryway; this site became occupied with an affinity constant around 10 mM. In contrast to the sites lying external to Ba2+, the internal lock-in site was not very selective for K+ when compared with Na+.

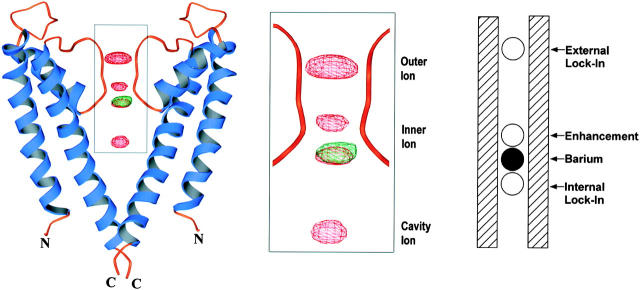

The membrane voltage dependence of lock-in and enhancement effects exerted by K+ on Ba2+ provided an estimate of the electrical distance that K+ must travel through the channel to reach a specific site. Ions in the pore presumably move in a somewhat concerted fashion, making the electrical distance a complicated quantity without a simple structural interpretation. Nevertheless, electrical distances for the K+ sites were informative. The external lock-in and enhancement sites appeared to reside ∼15 and 50%, respectively, of the way across the membrane electric potential difference relative to the outside, and the internal lock-in site appeared to reside ∼70% of the way (i.e., 30% of the electrical distance from the internal solution). These experiments supported the picture in Fig. 1, right. Following the Neyton and Miller 1988a,Neyton and Miller 1988b analysis of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, similar results were obtained by Vergara et al. 1999 and by Harris et al. 1998 in their studies of the voltage-dependent Shaker K+ channel.

Figure 1.

Visualization of barium in the KcsA K+ channel by x-ray crystallography and in a Ca2+-activated K+ channel by analysis of single channel function. (Left) A ribbon diagram showing two subunits of the KcsA K+ channel (blue and orange) with difference electron density showing the positions of Rb+ (red mesh) and Ba2+ (green mesh) in the pore. (Middle) Magnified view of the boxed region on the left. The Rb+ difference maps were calculated at 3.8-Å resolution and contoured at 9.0 σ. Three ion positions are labeled outer, inner, and cavity ion. The inner ion shows two peaks reflecting alternative positions. The Ba2+ difference map was calculated at 5.0-Å resolution and contoured at 10.0 σ; Ba2+ is located at the innermost position of the inner ion. (Right) Diagram adapted from Neyton and Miller (1988) depicting the relative locations of Ba2+ and K+ or Rb+ sites (external lock-in, enhancement, and internal lock-in) as determined by examination of single-channel records. The ions are positioned according to their electrical distance across the membrane potential difference. The figure was prepared using Ribbons (Carson 1997).

X-ray structure determination of the KcsA K+ channel showed that it contains multiple permeant ions in its pore (Doyle et al. 1998). Given the high degree of amino acid sequence conservation in the pore-forming regions of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel, the Shaker K+ channel, and the KcsA K+ channel, we expect their three-dimensional structures to be conserved. In this study, we determined the position of Ba2+ in the pore of the KcsA K+ channel. The results allow a comparison of the ionic configuration deduced by structural (x-ray crystallographic) and functional (electrical analysis of single channels) methods.

METHODS

The KcsA K+ channel was purified and crystallized as described (Doyle et al. 1998). The Ba2+-containing crystals were prepared by first washing crystals in a solution of 50% PEG400, 200 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM LDAO, 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and then soaking them in an otherwise identical solution containing 100 mM CaCl2 and 100 mM BaCl2 for 1 h. Crystals were frozen in a cold nitrogen stream (∼100°K) and stored in liquid nitrogen–cooled propane. Data were collected at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, A1 station, and processed with DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski 1993; Otwinowski and Minor 1997). The electron density of Ba2+ in the channel was calculated from the Fourier transformation of (Fbarium − Fnative) e −iφ, where Fbarium and Fnative are the observed structure factors for the Ba2+-containing and native crystals, respectively, and φ is the experimental (MIR, solvent-flattened, averaged) phase. Due to crystal damage during the soaking procedure, data were useful only to 5.0-Å resolution.

RESULTS

Crystals of the KcsA K+ channel were equilibrated in solutions containing 100 mM BaCl2. Ionic strength was kept constant by replacing CaCl2 present in the crystal growth solution with BaCl2. At the same time, 150 mM KCl was replaced by an equal amount of NaCl. It was necessary to lower the K+ concentration to observe Ba2+ in the pore. We assume that K+, at high concentrations, displaces Ba2+ from the pore.

The location of Ba2+ in the pore is well defined in a difference Fourier map (Fbarium − Fnative) calculated at 5.0-Å resolution (Fig. 1, left and center, green mesh). Electron density for Ba2+ is compared with that for Rb+ ions determined in a separate experiment (red mesh). The Rb+-difference Fourier map, calculated at 3.8-Å resolution, shows two ions in the selectivity filter and one in the cavity at the membrane center, below the selectivity filter (Doyle et al. 1998). The two ions in the selectivity filter are called the outer and inner ions. The outer ion is near the extracellular entryway and the inner ion is closer to the cavity and can be at either of two positions. The Ba2+ ion very clearly binds at the location of the inner ion closest to the central cavity.

DISCUSSION

The consistency of structural data on the KcsA K+ channel with functional data on Ca2+-activated K+ channels is quite remarkable. The external lock-in effect implied the existence of a first ion binding site external to Ba2+. This site had to be highly selective for permeant alkali metal cations and very near the extracellular solution, because external lock-in is a weakly voltage-dependent process. The outer ion in the KcsA selectivity filter fulfills these criteria. The external enhancement effect implied a second site, also external to Ba2+ and highly selective for permeant ions. The stronger voltage dependence of its apparent occupancy suggested that the enhancement site is deeper in, closer to the Ba2+ ion. The effective K d for achieving the enhancement configuration of two K+ ions external to Ba2+ is nearly 500 mM, indicating that it is a relatively unstable configuration. In the structure, the outermost peak of the inner ion is too close to Ba2+ to be the precise site of the enhancement ion. However, the structure of the selectivity filter provides several potential ion binding sites external to Ba2+.

The internal lock-in effect required a site internal to Ba2+ that, in contrast to the external sites, exhibits little ion selectivity. The cavity ion in the crystal structure, being fully hydrated and not in direct contact with protein functional groups, fulfills the requirements of the internal lock-in site completely. Even the relatively weak voltage dependence of internal lock-in is consistent with the idea that a large fraction of the membrane voltage falls across the narrow selectivity filter (Doyle et al. 1998).

Given the high affinities of the external and internal lock-in sites, it seems likely that they would contain a K+ most of the time at physiological ion concentrations. Therefore, the picture of the pore with three ions (two in the selectivity filter and one in the cavity), derived from the crystal structure, is probably not very different from a snapshot of what the conducting channel looks like in the membrane. The external enhancement effect is interesting because it suggests that a fourth ion enters the pore (that is, a third ion in the selectivity filter) to push the queue along (and Ba2+ out). The affinity for the enhancement site is low, and corresponds reasonably well to the concentration range over which the conductance increases as K+ concentration is raised (0.3–1.0 M, depending on the K+ channel). This enhancement configuration would not have been abundant in the crystal bathed in only 150 mM KCl (or RbCl). Further experiments are needed to test this possibility.

The idea that K+ channels have multiple ions in their pore is as old as the ion channel field itself (Hodgkin and Keynes 1955). The mind's eye picture of multiple ions in a queue earned K+ channels the name “long-pore channels” because it seemed that multiple ions with a large separation between them would require a long pore. When mutational analysis of K+ channels identified a short pore-region sequence, and even shorter signature sequence forming the selectivity filter, the result seemed contradictory (Heginbotham et al. 1994). How could so few amino acids form a long enough pore to accommodate the queue of ions? The K+ channel structure answers this question. And ironically, in the answer, we see that the long pore is not very long at all: three ions are compressed into a distance of roughly 15 Å—about half the membrane thickness. The close spacing is probably not happenstance; it allows for strong interactions between ions in the pore. Ionic interactions, mediated by electrostatics and perhaps by the structure of the selectivity filter itself, offer a solution to the apparent paradox of simultaneous high turnover and high selectivity in K+ channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joao Morais Cabral for helpful discussions and Christopher Miller and Jacques Neyton for manuscript criticism.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM47400. R. MacKinnon is an Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Y. Jiang is a Postdoctoral Associate in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Armstrong C.M., Swenson R.P., Taylor S.R. Block of squid axon K channels by internally and externally applied barium ions. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;80:663–682. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.5.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C.M., Taylor S.R. Interaction of barium ions with potassium channels in squid giant axons. Biophys. J. 1980;30:473–488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham C.D., Bolton T.B., Lang R.J., Takewaki T. The mechanism of action of Ba2+ and TEA on single Ca2+-activated K+-channels in arterial and intestinal smooth muscle cell membranes. Pflügers Arch. 1985;403:120–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00584088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M. Ribbons. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:493–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D.A., Morais Cabral J.H., Pfuetzner R.A., Kuo A., Gulbis J.M., Cohen S.L., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channelmolecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton D.C., Brodwick M.S. Effect of barium on the potassium conductance of squid axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 1980;75:727–750. doi: 10.1085/jgp.75.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R.E., Larsson H.P., Isacoff E.Y. A permanent ion binding site located between two gates of the Shaker K+ channel. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1808–1820. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(98)77891-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L., Lu Z., Abramson T., MacKinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys. J. 1994;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin A.L., Keynes R.D. The potassium permeability of a giant nerve fibre. J. Physiol. 1955;128:61–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. Trapping single ions inside single ion channels. Biophys. J. 1987;52:123–126. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83196-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyton J., Miller C. Discrete Ba2+ block as a probe of ion occupancy and pore structure in the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel J. Gen. Physiol. 92 1988. 569 586a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyton J., Miller C. Potassium blocks barium permeation through a calcium-activated potassium channel J. Gen. Physiol. 92 1988. 549 567b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. 1993. In Data Collection and Processing. L. Sawyer and S. Bailey, editors. Science and Engineering Research Council, Daresbury Laboratory, Daresbury, UK. 56–62.

- Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C., Alvarez O., Latorre R. Localization of the K+ lock-in and the Ba2+ binding sites in a voltage-gated calcium-modulated channel. Implications for survival of K+ permeability. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;114:365–376. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C., Latorre R. Kinetics of Ca2+-activated K+ channels from rabbit muscle incorporated into planar bilayers. Evidence for a Ca2+ and Ba2+ blockade. J. Gen. Physiol. 1983;82:543–568. doi: 10.1085/jgp.82.4.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Chepilko S., Choe H., Palmer I.G., Sackin H. Mutations in the pore region of ROMK enhance Ba2+ block. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C1949–C1956. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.6.C1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]