Abstract

Strong depolarization and dihydropyridine agonists potentiate inward currents through native L-type Ca2+ channels, but the effect on outward currents is less clear due to the small size of these currents. Here, we examined potentiation of wild-type α1C and two constructs bearing mutations in conserved glutamates in the pore regions of repeats II and IV (E2A/E4A-α1C) or repeat III (E3K-α1C). With 10 mM Ca2+ in the bath and 110 mM Cs+ in the pipette, these mutated channels, expressed in dysgenic myotubes, produced both inward and outward currents of substantial amplitude. For both the wild-type and mutated channels, we observed strong inward rectification of potentiation: strong depolarization had little effect on outward tail currents but caused the inward tail currents to be larger and to decay more slowly. Similarly, exposure to DHP agonist increased the amplitude of inward currents and decreased the amplitude of outward currents through both E2A/E4A-α1C and E3K-α1C. As in the absence of drug, strong depolarization in the presence of dihydropyridine agonist had little effect on outward tail currents but increased the amplitude and slowed the decay of inward tail currents. We tested whether cytoplasmic Mg2+ functions as the blocking particle responsible for the rectification of potentiated L-type Ca2+ channels. However, even after complete removal of cytoplasmic Mg2+, (−)BayK 8644 still potentiated inward current and partially blocked outward current via E2A/E4A-α1C. Although zero Mg2+ did not reveal potentiation of outward current by DHP agonist, it did have two striking effects, (a) a strong suppression of decay of both inward and outward currents via E2A/E4A-α1C and (b) a nearly complete elimination of depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail currents. These results can be explained by postulating that potentiation exposes a binding site in the pore to which an intracellular blocking particle can bind and produce inward rectification of the potentiated channels.

Keywords: voltage-dependent potentiation, dihydropyridine agonist, gating

INTRODUCTION

Voltage-gated calcium channels are present in a wide variety of cell types and mediate numerous vital cellular processes including neurotransmitter release, neurite outgrowth, regulation of gene expression, exocytosis, and muscle contraction. One class of these channels, L-type calcium channels, plays a crucial role in excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. The cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel is a complex of proteins including the pore-forming α1C subunit and the auxiliary β and α2δ subunits. These cardiac channels are subject to a number of different kinds of regulation, which lead to an increase in Ca2+ current magnitude. One of these pathways is the cAMP-dependent phosphorylation cascade that is activated by β-adrenergic agonists (Tsien et al., 1986; McDonald et al., 1994). Additionally, a train of repetitive depolarizations or a strongly depolarizing prepulse can cause the cardiac Ca2+ channel to enter a mode of increased open probability, a process termed either facilitation or potentiation depending on the protocol used to measure it. To measure “depolarization-induced facilitation,” a strong conditioning depolarization is followed by a 50–150 ms repolarization to the holding potential, followed by a subsequent moderate depolarization. This conditioning paradigm elicits a Ca2+ channel current that is about twofold larger than that measured in the absence of the conditioning depolarization (Bourinet et al., 1994; Cens et al., 1998; Altier et al., 2001). This mechanism of facilitation suggests an alteration in channel gating that persists after channel closure (which occurs during repolarization to the holding potential). Another form of altered gating, “depolarization-induced potentiation,” is measured when a strong depolarization is followed immediately by repolarization to an intermediate potential. This potentiation protocol results in a mode of gating characterized at the single-channel level by high open probability and long open times, which is also referred to as “mode 2” gating (Pietrobon and Hess, 1990). Like depolarization-induced potentiation, dihydropyridine (DHP)* agonists also promote “mode 2” gating (Hess et al., 1984, Nowycky et al., 1985). Although the cardiac L-type channel is potentiated both by strong depolarization and by DHP agonists, these two types of potentiation occur by two distinct mechanisms (Wilkens et al., 2001).

Nearly all studies of the potentiation and facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels have focused on inward currents, although these channels also produce small outward currents for sufficiently strong depolarizations. Thus, the goal of our work was to compare the potentiation of inward and outward L-type Ca2+ currents in response to either strong depolarization or DHP agonists. Analysis of outward currents via native (α1C containing) channels is hampered by the small size of these currents and the need for excessively strong depolarizations in order to elicit them. Thus, for most of our experiments we used mutants of α1C with alterations of conserved glutamates in the pore region, which are known to be critical determinants for the divalent versus monovalent selectivity of the channel (Yang et al., 1993; Sather and McCleskey, 2003). Single or multiple mutations of these glutamate residues can alter channel permeability such that the channels exhibit smaller inward currents carried by Ca2+ and greater outward currents carried by monovalent cations (Yang et al., 1993).

We used two different mutants of α1C for this study: (a) E2A/E4A-α1C in which the glutamate residues of α1C in domains II and IV were replaced by alanine residues, and (b) E3K-α1C in which the glutamate residue in domain III was replaced by a lysine residue. When expressed in dysgenic myotubes (null for α1S), both mutants produced smaller inward currents, and much larger outward currents, compare with wild-type α1C. For the wild-type channel and both mutants, inward tail currents were larger and decayed more slowly after a strong depolarization (≥90 mV) than after a more moderate depolarization. However, when the cells were repolarized to a voltage at which the tail currents were outward, there was little effect of the prior strong depolarization. Moreover, for both of the mutant channels, application of DHP agonist greatly increased inward currents but actually reduced outward currents. To test whether block by intracellular Mg2+ was responsible for this apparent rectification of the potentiated state, measurements were made using a pipette solution with Mg2+ buffered to a very low level. Even after the removal of cytoplasmic Mg2+, DHP agonist potentiated inward but not outward current. Thus, Mg2+ does not function as a blocking particle responsible for this rectification. Together, our results are consistent with the idea that strong depolarization or DHP agonist alters the pore configuration of L-type channels, such that outward, but not inward, currents are blocked by a cytoplasmic particle of unknown identity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of cDNA in Dysgenic Myotubes

Primary cultures of myotubes were prepared from skeletal muscle of newborn dysgenic mice, which lack an endogenous α1S subunit, as described previously (Beam and Knudson, 1988). All experiments were performed 8–10 d after the initial plating of myoblasts and were performed at room temperature. 1 wk after plating, the myotubes were microinjected in single nuclei with cDNA encoding α1C, or the α1C pore mutants E3K-α1C or E2A/E4A-α1C (200 ng/μl). The cDNAs encoding E3K-α1C and E2A/E4A-α1C were a gift from Dr. William Sather. Although these pore mutants produced a reduced density of current compared with wild-type α1C, their expression in dysgenic myotubes resulted in currents of sufficient size to allow straightforward analysis. Myotubes expressing α1C, E3K-α1C, or E2A/E4A-α1C were usually identified by coinjection of 20–50 ng/μl of a cDNA expression plasmid encoding an enhanced green fluorescent protein (provided by Dr. P. Seeburg), which was modified as described in Grabner et al. (1998). 36–52 h after injection, expressing myotubes were identified by green fluorescence and used for electrophysiology.

Characterization of Ionic Currents

Macroscopic Ca2+ currents were measured using the whole-cell patch-clamp method (Hamill et al., 1981). Patch pipettes of borosilicate glass had resistances of 1.8–2.2 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution containing (mM): 110 CsCl, 3 MgCl2, 10 Cs2EGTA, 10 HEPES, 3 Mg-ATP and 0.6 GTP, pH = 7.4 with CsOH. Some recordings made use of a Mg2+-free intracellular solution, which contained (mM): 125 Cs-aspartate, 5 CsCl, 10 Cs2EGTA, 10 Cs2EDTA, 10 HEPES, pH = 7.4 with CsOH. The external bath solution contained (mM): 10 CaCl2, 145 TEA-Cl, 0.003 tetrodotoxin, and 10 HEPES, pH = 7.4 with TEA-OH. Working solutions of +SDZ 202–791 (Sandoz) were diluted in the recording solution from a 10 mM stock solution made in 100% EtOH. (−)BayK 8644 was diluted in the recording solution from a 1 mM stock solution (in 50% EtOH, 50% H2O). To measure L-type current, myotubes were stepped from the holding potential (−80 mV) to −30 mV for 1 s (to inactivate endogenous T-type current), repolarized to −50 mV for 30–50 ms, depolarized to varying test potentials (Vtest) for 200 ms, repolarized to −50 mV for 125 ms, and then returned to the holding potential. Alternatively, the 200-ms test potential was followed by a 50-ms step to varying potentials before the 125-ms step to 50 mV. Test currents were corrected for linear components of leak and capacitive current by digitally scaling and subtracting the average of 10 control currents elicited by a hyperpolarizing step to −100 mV delivered from the holding potential before each test pulse. Cell capacitance was determined by integration of the capacity transient resulting from these control pulses and was used to normalize current amplitudes (pA/pF) obtained from different myotubes. Current-voltage curves were fitted using the following Boltzmann expression:

|

where I is the current for the test potential V, Vrev is the reversal potential, Gmax is the maximum Ca2+ channel conductance, V1/2 is the half maximal activation potential, and kG is the slope factor. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

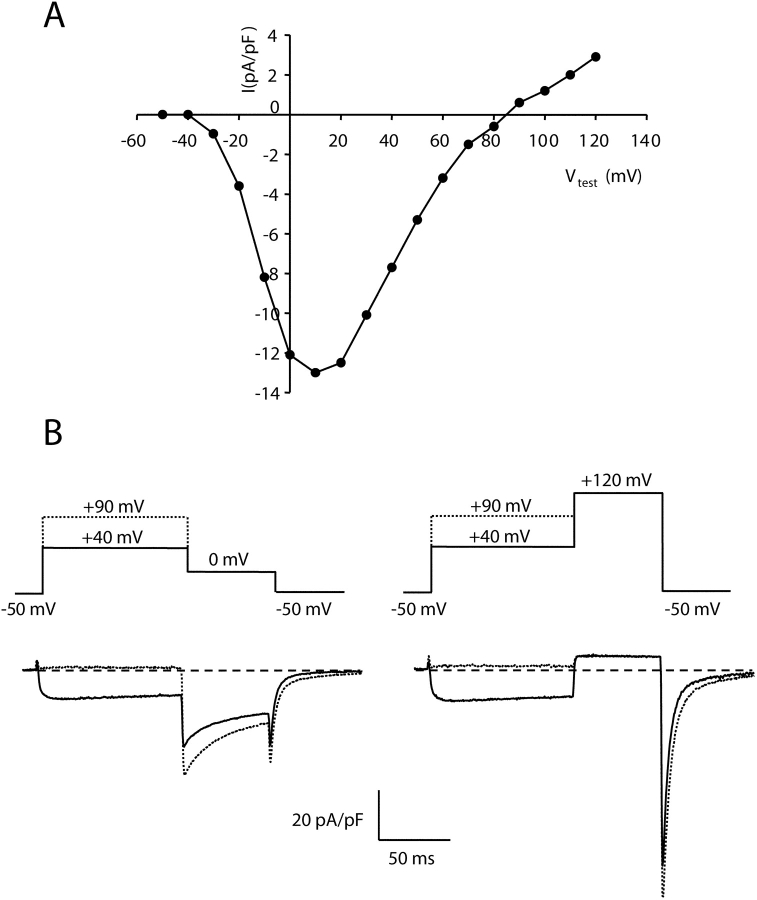

Preferential Potentiation of Inward Currents via Wild-type α1C

Fig. 1 A illustrates the peak current-voltage relationship measured in a dysgenic myotube expressing wild-type α1C. The wild-type cardiac channel produced inward Ca2+ currents for test potentials ranging from −20 to 70 mV, and small outward currents for test potentials >90 mV. Fig. 1 B, left, demonstrates for this same cell that a strong depolarizing prepulse (to 90 mV) caused potentiation of the inward current measured upon repolarization to 0 mV (dashed trace) compared with the current seen upon repolarization to 0 mV after a weaker depolarization (40 mV, continuous trace), but still sufficient to fully activate α1C (Wilkens et al., 2001). This potentiation of inward current induced by strong depolarization is similar to that described previously for L-type currents in cardiac ventricular myocytes (Pietrobon and Hess, 1990). Interestingly, as shown in the Fig. 1 B, right, strong depolarization failed to cause potentiation of the outward current at 120 mV. However, even after the additional time spent at +120 mV (which presumably promoted increased potentiation), the inward tail current upon repolarization to −50 mV was larger when preceded by the earlier pulse to 90 mV (dashed trace) compared with that after a pulse to 40 mV. Thus, the channels appeared to “remember” that they were potentiated even though the outward current was no different at 120 mV.

Figure 1.

Strong depolarization preferentially potentiates inward currents via wild-type α1C. (A) Peak current vs. voltage relationship measured in a dysgenic myotube expressing α1C. (B) Strong depolarization potentiates inward but not outward currents via α1C. Tail currents were measured after a 200-ms depolarization to either 40 or 90 mV (traces illustrated with continuous or dashed lines, respectively). Upon subsequent repolarization to 0 mV, the inward tail current (left) was much larger after the 90-mV depolarization, whereas the outward tail current upon further depolarization to 120 (right) was little affected. Note that even though the current at 120 appeared identical after the 40 or 90 test steps, subsequent repolarization to −50 mV revealed residual potentiation of inward tail current as a consequence of the 90-mV step.

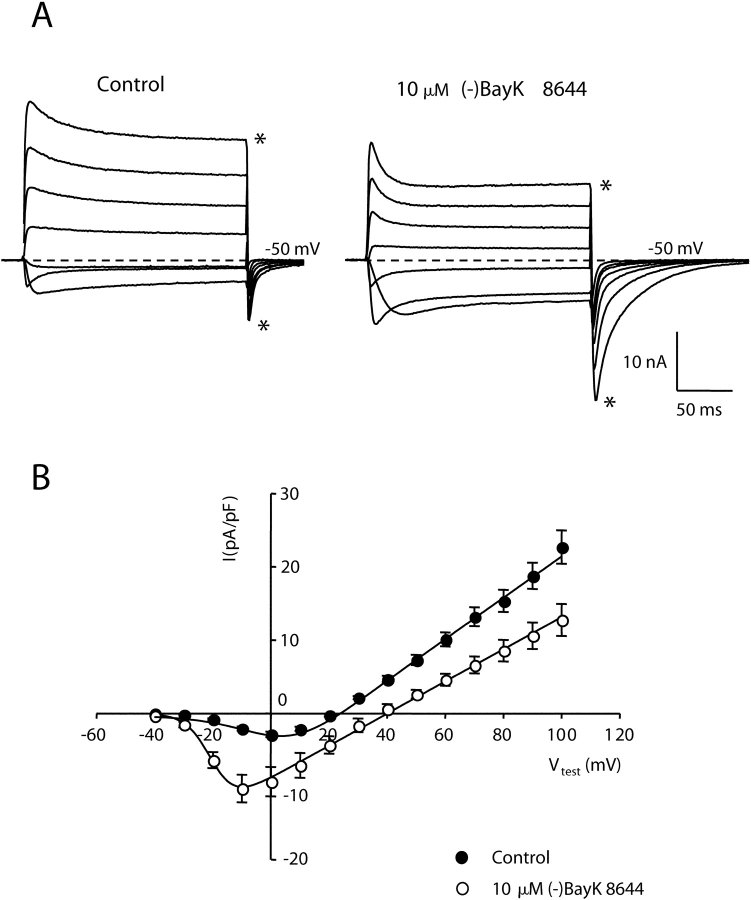

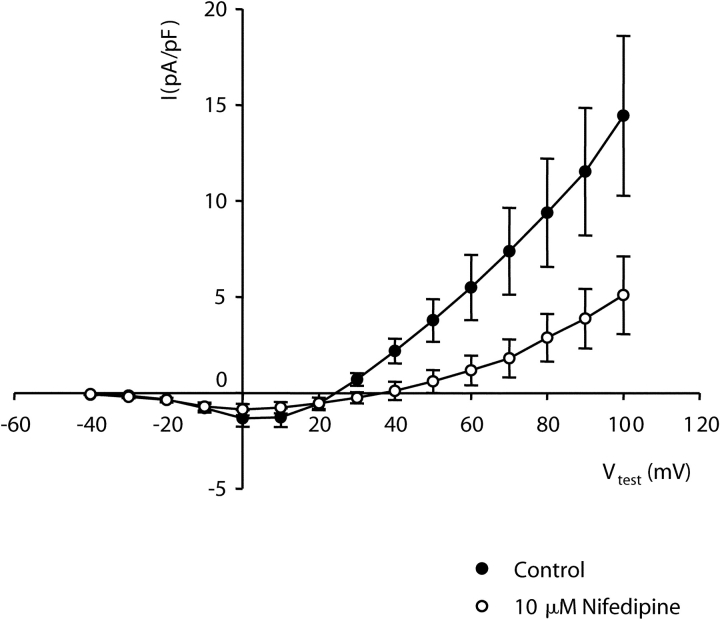

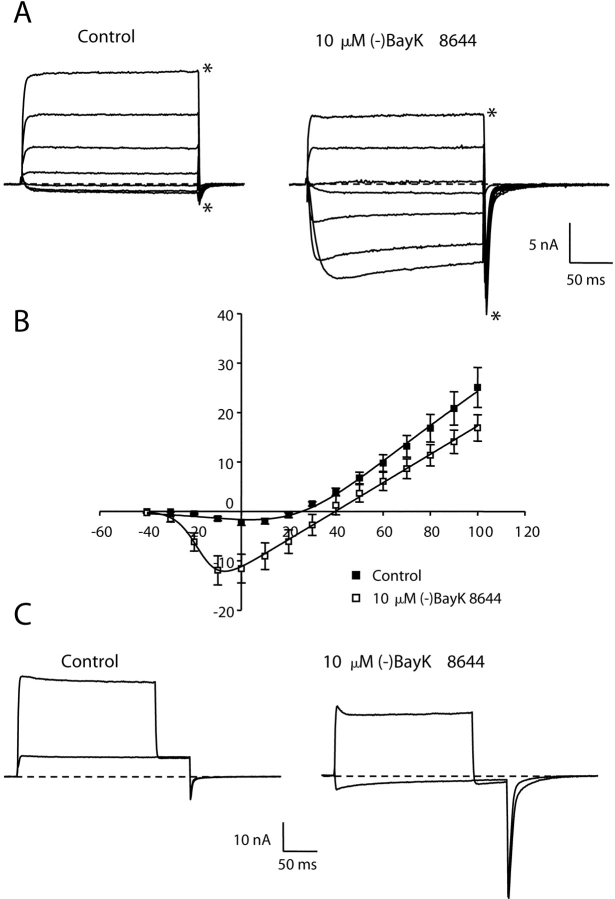

A DHP Agonist Potentiates Inward, but Not Outward, Currents via E2A/E4A-α1C

Although the experiment illustrated in Fig. 1 suggests preferential potentiation of inward current through α1C, the small size of outward currents through wild-type cardiac channels makes it difficult to quantify small effects on outward currents. Thus, we next characterized potentiation of L-type currents via α1C constructs that contain mutations in conserved pore domain glutamates that cause mutant channels to produce outward currents of appreciable size (Yang et al., 1993). Fig. 2 A shows currents from α1C channels in which conserved glutamate residues in the pore regions of both repeats II and IV were mutated to alanines (E2A/E4A-α1C). With a bath solution containing 10 mM Ca2+ and an internal solution containing 110 mM Cs+, E2A/E4A-α1C channels supported inward current for potentials more negative than 20 mV with a peak inward current at 0 mV. For potentials greater than 20 mV, these mutant channels produced a rapidly activating outward current. The addition of the DHP agonist (−)BayK 8644 (10 μM) increased the amplitude of the inward current and shifted the potential causing maximum inward current by −10 mV. In contrast, (−)BayK 8644 caused a decrease in peak amplitude of the outward current and a 20-mV depolarizing shift in the reversal potential (Fig. 2 B). Furthermore, the decay of currents during the test pulse was accelerated by (−)BayK 8644 (see also Fig. 7). Significantly, both the amplitude and decay time of inward tail currents upon repolarization to −50 mV were increased by (−)BayK 8644. This effect was especially pronounced after stronger depolarizations. For example, the amplitude of the tail current after the test pulse to 100 mV was more than twofold larger in the presence of (−)BayK 8644, even though the steady-state outward current just before repolarization was 1/3 smaller than control (compare traces with asterisk in Fig. 2 A). In summary, the currents produced by E2A/E4A-α1C are generally similar to those of wild-type α1C, but the increased magnitude of outward currents facilitates comparison of the effects of potentiating stimuli on both inward and outward currents. Moreover, both the inward and outward currents were attributable to the mutant channel since both were reduced by 10 μM nifedipine (Fig. 3) , although this reduction was less than for currents via native α1C (Lee and Tsien, 1983). From the data in Fig. 2, it appears that channels potentiated by DHP agonist have different conductive properties than those of nonpotentiated channels because (a) the reversal potential is positively shifted and (b) outward currents are decreased by DHP agonist, whereas inward tail currents are increased.

Figure 2.

Dihydropyridine agonist potentiates E2A/E4A-α1C currents. (A) Representative whole-cell ionic currents obtained from dysgenic myotubes expressing E2A/E4A-α1C before (left) and after (right) application of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644. The illustrated currents were elicited by 200-ms depolarizations to potentials (Vtest) ranging from −20 to 100 mV in increments of 20 mV, followed by a repolarization to −50 mV. The dashed lines represent the zero current level. Asterisks indicate the currents for a Vtest of 100 mV. (B) Average peak current versus voltage relationship for E2A/E4A-α1C in the absence (closed symbols, n = 19) or presence (open symbols, n = 9) of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644. The smooth curves represent best fits of the Boltzmann expression (see materials and methods) to the average data resulting in the values (control; BayK), Gmax = 281 nS/nF; 219 nS/nF, Vrev = 22.8 mV; 40.2 mV, V1/2 = 2.9 mV; −19.9 mV, kG = 9.5 mV; 4.2 mV.

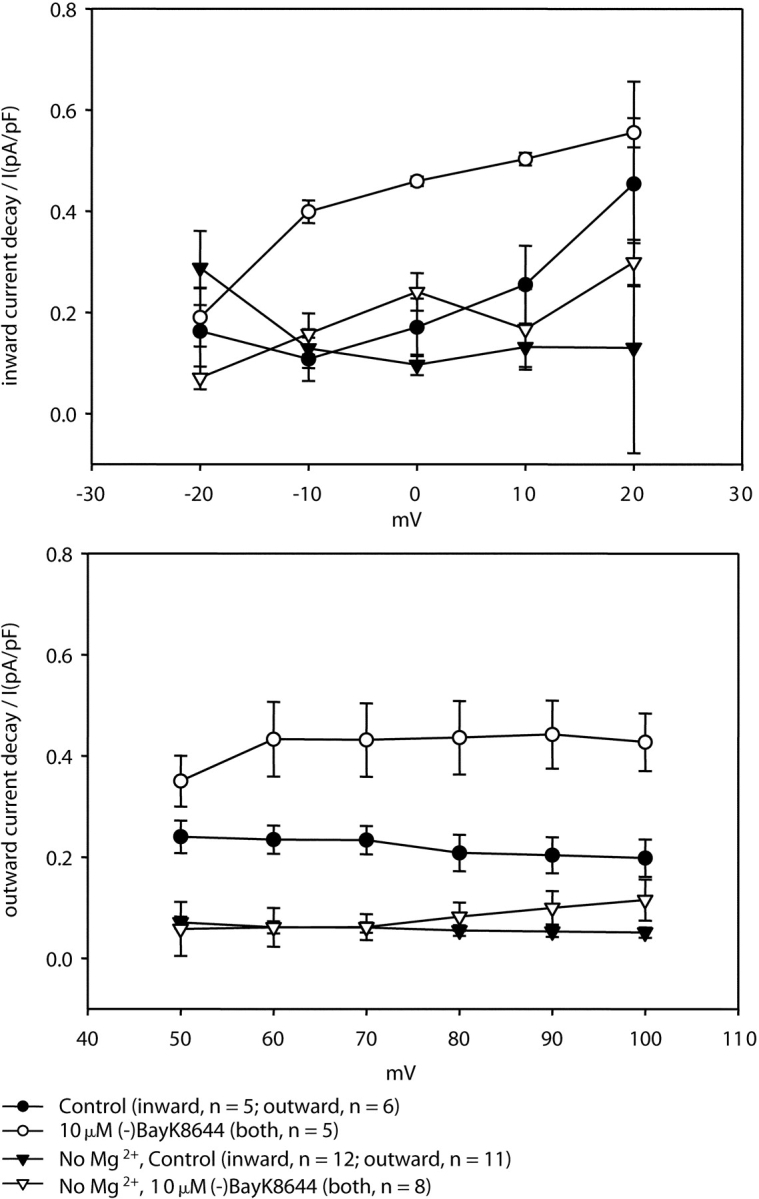

Figure 7.

Removal of intracellular Mg2+ greatly reduces fractional decay of both inward and outward currents via E2A/E4A-α1C. Fractional decay of current was measured as the difference between the peak and steady-state current amplitudes divided by the peak current amplitude and is shown for both inward (top panel, Vtest of −20 to 20 mV) and outward (bottom panel, Vtest of 50–100 mV) currents. Data are shown for a pipette solution containing Mg2+ (circles) and for a Mg2+-free pipette (triangles). Both in the absence (filled symbols) and presence (open symbols) of (−)BayK 8644, the Mg2+-free pipette solution almost completely eliminated the decay of inward and outward currents.

Figure 3.

Inward and outward currents mediated by E2A/E4A-α1C are significantly reduced by DHP antagonist. Average peak currents versus test potential measured in six cells before (closed symbols) and after (open symbols) the addition of 10 μM nifedipine.

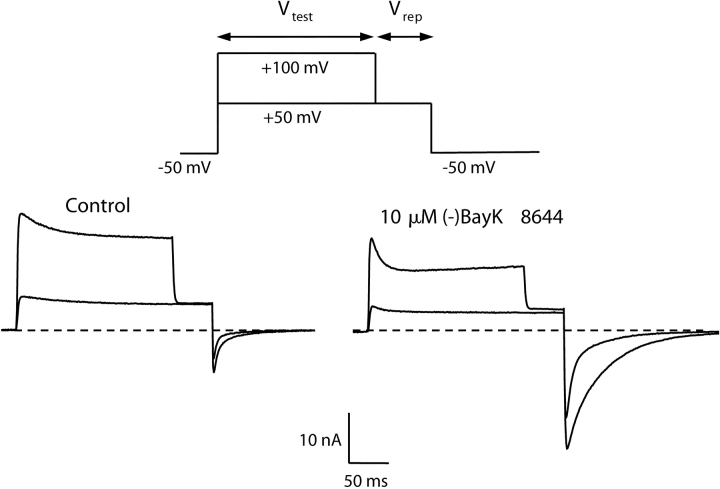

Strong Depolarization Potentiates Inward, but Not Outward, Currents via E2A/E4A-α1C

Fig. 4 illustrates the protocol used to compare the effects of depolarization-induced potentiation on the magnitude of outward (repolarization to 50 mV) and inward (repolarization to −50 mV) tail currents. Under control conditions, a strong depolarization to 100 mV (Vtest) increased the amplitude, and slowed the decay, of inward tail currents and had little effect on outward tail current magnitude. Likewise, in the presence of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644, strong depolarization also had little effect on outward tail current but potentiated inward tail current. In fact, the slowing of decay and increase of amplitude of inward tail current after strong depolarization were both amplified in the presence 10 μM (−)BayK 8644.

Figure 4.

Depolarization-induced potentiation of E2A/E4A. To measure voltage-dependent potentiation, the cell was depolarized for 200 ms to a Vtest of either 50 or 100 mV, then stepped to a repolarization potential (Vrep) of 50 mV and then to a final potential of −50 mV. Whole-cell currents elicited by this protocol are shown for a myotube expressing E2A/E4A before (left) and after (right) application of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644.

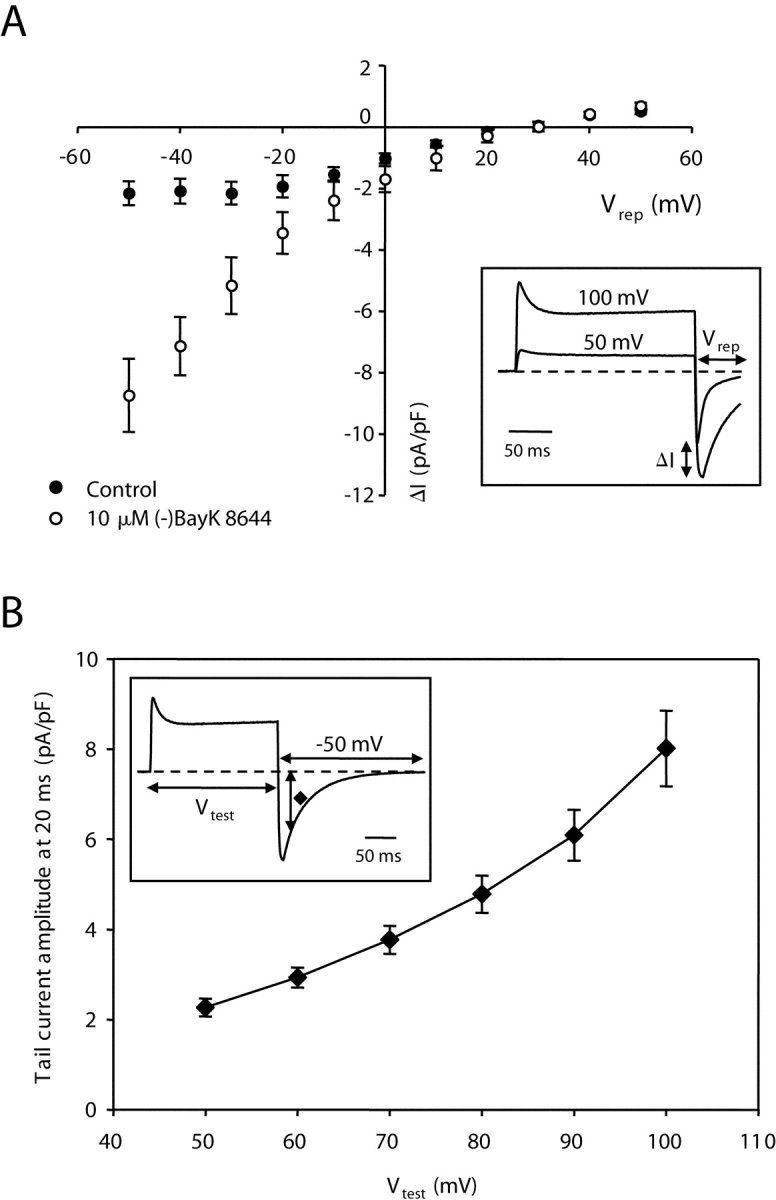

Fig. 5 A illustrates, as a function of repolarization potential (Vrep), the amplitude of the potentiated current (ΔI), defined as the difference between tail current amplitudes after a Vtest of 100 and 50 mV, respectively (see inset). Thus, negative values represent potentiation of inward current and positive values represent potentiation of outward current. However, because ΔI was measured isochronally in each cell (7–9 ms after onset of repolarization), its value represents an over-estimate of potentiation for outward currents and an underestimate for inward tail currents. The underestimate is particularly significant for the rapidly decaying, inward tail currents at hyperpolarized potentials in control cells. Nonetheless, it appears that current potentiation in response to strong depolarization displays rectification: despite strong depolarization-induced potentiation of inward current there is little or no potentiation of outward current, particularly in the presence of (−)BayK 8644.

Figure 5.

Amplitude of potentiated tail current as a function of repolarization (Vrep) and the dependence of potentiated tail current amplitude on the prior test potential (Vtest). (A) Depolarization-induced increase of tail current amplitude as a function of Vrep (ranging from −50 to 50 mV) using the general protocol described in Fig. 4 in the absence (closed symbols, n = 10) and presence (open symbols, n = 8) of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644. The voltage-dependent increase in tail current amplitude (ΔI) at each Vrep was determined by subtracting the amplitude measured following the Vtest to 50 mV from that measured after the Vtest to 100 mV (see inset). (B) Tail current amplitude measured 20 ms after repolarization to −50 mV was measured as a function of Vtest (inset) in the presence of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 (n = 6).

Fig. 5 B shows the voltage dependence of entry into the potentiated state during the 200-ms test pulse. These experiments were performed with a bath solution containing 10 μM (−)BayK 8644, which slowed the decay of tail current and therefore made it easier to measure depolarization-induced potentiation. As a means of partially isolating the component of tail current attributable to depolarization-induced potentiation, tail current amplitude was measured 20 ms after repolarizing to −50 mV. The rationale for this approach is twofold. First, the tail current in the presence of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 has decayed substantially (∼70%) at 20 ms of repolarization after a Vtest of 50 mV (compare Fig. 4). Because still stronger depolarization caused a substantial slowing of decay, the current amplitude 20 ms after repolarization is dominated by the component of current that had undergone depolarization-induced potentiation. Second, under conditions that eliminate depolarization-induced potentiation (see the following section), decay of tail currents at −50 mV is nearly complete at 20 ms after repolarization to −50 mV, even in the presence of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 (see Fig. 6 A). The apparent voltage dependence of depolarization-induced potentiation measured as just described is in rough agreement with that reported by Pietrobon and Hess (1990) for cardiac L-type channels in the absence of DHP agonist (their Fig. 3).

Figure 6.

An Mg2+-free pipette solution abolishes voltage-dependent potentiation of inward current. (A) Representative whole-cell currents measured with a Mg2+-free pipette solution (see materials and methods) from a dysgenic myotube expressing E2A/E4A-α1C before (left) and after (right) application of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644. The illustrated currents were elicited by 200-ms depolarizations to potentials ranging from −20 to 100 mV in increments of 20 mV, followed by repolarization to −50 mV. (B) Average peak current versus voltage relationship for E2A/E4A-α1C in the absence (closed symbols, n = 12) or presence (open symbols, n = 9) of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 with a Mg2+-free pipette solution. The smooth curves represent best fits of the Boltzmann expression (see materials and methods) yielding the values (control; BayK), Gmax = 330 nS/nF; 287 nS/nF, Vrev = 25.7 mV; 39.8 mV, V1/2 = 23.6 mV; −17.4 mV, kG = 16.6 mV; 4.7 mV. (C) Absence of depolarization-induced potentiation of E2A/E4A-α1C currents with a Mg2+-free pipette solution. Whole cell currents, elicited by the same protocol as that described in Fig. 4, are shown for a myotube expressing E2A/E4A-α1C before (left) and after (right) application of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644. There is very little potentiation of the inward tail current at −50 mV following a 100-mV depolarization. Note that because of the shift in Vrev, the tail current at 50 mV is outward in the control and inward in (−)BayK 8644.

Intracellular Mg2+ Is Required for Voltage-dependent Potentiation of Inward Currents and Enhanced Outward Current Decay

The potentiation of inward but not outward currents by both DHP agonist and strong depolarization raises the possibility that the potentiated state of L-type channels rectifies, which could be due to block of outward current by an intracellular cation. To test the possibility that Mg2+ serves this function, we examined potentiation of E2A/E4A-α1C using a pipette solution that contained no added Mg2+ together with 10 mM EDTA to chelate endogenous Mg2+. With this Mg2+-free pipette solution, control currents in the absence of DHP agonist showed a voltage dependence (Fig. 6, A and B) similar to that of currents measured with a Mg2+-containing pipette solution (compare Fig. 2). Furthermore, the application of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 caused potentiation of inward current, a reduction of outward current, and a positive shift of reversal potential (Fig. 6, A and B) similar to those observed with a Mg2+-containing pipette solution. Thus, block by intracellular Mg2+ does not account for the preferential potentiation of inward current by DHP agonist. Surprisingly, however, the Mg2+-free pipette solution strongly suppressed the depolarization-induced potentiation of inward current. Thus, although inward tail currents were significantly increased by 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 (Fig. 6 A, compare left and right), the inward tail currents at −50 mV in the presence of this drug did not show a slowing of decay after a strong Vtest (Fig. 6 A, right) similar to that observed for the currents measured with a Mg2+-containing solution (Fig. 2 A, right). The Mg2+-free reduction of depolarization-induced potentiation was also observed directly by comparing tail currents after a Vtest of either 50 or 100 mV (Fig. 6 C, left). The depolarization-induced augmentation of inward tail current at −50 mV (ΔI measured as illustrated in the inset to Fig. 5 A) was much smaller for the Mg2+-free solution compared with the control solution (ΔI was −0.7 ± 0.1 pA/pF, n = 10 and 2.2 ± 0.4 pA/pF, n = 10 in the absence and presence of Mg2+, respectively). Nevertheless, (−)BayK 8644 caused an ∼4-fold increase in ΔI in both conditions (in the presence of (−)BayK 8644 ΔI was −3.2 ± 0.4 pA/pF, n = 7 and 8.7 ± 0.4 pA/pF, n = 8 in the absence and presence of Mg2+, respectively).

In addition to suppressing depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail current, the extent of decay of outward current via E2A/E4A-α1C was attenuated by the Mg2+-free pipette solution (compare Figs. 2 and 6), raising the possibility that these two phenomena are causally related. One hypothesis that could account for such a causal relationship would be to suppose that the potentiated state of the channel strongly rectifies in the inward direction such that entry into the potentiated state during strong depolarization is reflected as a decay of outward current. Two observations would appear to support this idea. First, both the decay of outward current and the extent of depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail current are amplified in the presence of 10 μM (−)BayK 8644 and intracellular Mg2+ (Fig. 4). Second, a Mg2+-free pipette solution greatly reduced both the decay of outward current (Fig. 6 A) and depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail current (Fig. 6 C). However, the reduction in decay of outward current by a Mg2+-free pipette solution appears to reflect a more general phenomenon since the decay of both inward and outward currents was greatly reduced (Fig. 7 , top and bottom, respectively). Moreover, the fractional decay of outward current varied little between 50 and 100 mV (Fig. 7, bottom). By contrast, the amplitude of inward tail current (measured 20 ms after repolarization to −50 mV) increased almost fourfold over this same voltage range (Fig. 5 B). Thus, the depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail current (using a Mg2+-containing pipette solution) does not appear to be causally related to the decay of outward current.

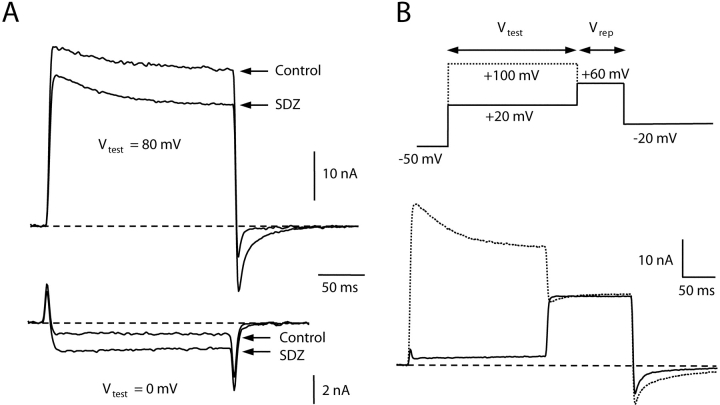

Potentiation Also Displays Inward Rectification for α1C Bearing a Single Mutation in the Pore Region of Repeat III

To verify that the preferential potentiation of inward current was not simply a peculiarity of E2A/E4A-α1C channels, we also examined the behavior of a distinct α1C mutant, E3K-α1C. In E3K-α1C, a conserved glutamate residue in the pore region of repeat III was mutated to a positively charged lysine residue. With the same pipette and bath solutions as used for the experiments illustrated in Figs. 2 and 4, E3K-α1C channels produce rapidly activating inward currents for test potentials more negative than 10 mV and large outward currents for test potentials >20 mV (Dirksen and Beam, 1999). Fig. 8 shows representative current traces from an E3K-α1C-expressing dysgenic myotube before and after application of 1 μM +SDZ 202–791. As for E2A/E4A-α1C, application of DHP agonist caused an increase in inward current via E3K-α1C and a decrease in the amplitude of outward currents through the channel (Fig. 8 A). Fig. 8 B illustrates the effects of strong depolarization on E3K-α1C tail currents in the presence of +SDZ 202–79. Outward tail currents for a step to 60 mV were similar after a 200-ms Vtest to either 20 or 100 mV, whereas the inward current for repolarization to −20 mV showed both an increased amplitude and slowed decay after a strong depolarization (Vtest = 100 mV). Similar results were obtained in five additional cells. Thus, potentiation of both E2A/E4A-α1C and E3K-α1C shows strong inward rectification.

Figure 8.

Another α1C pore mutant, E3K-α1C, also displays preferential potentiation of inward currents by dihydropyridine agonist and strong depolarization. (A) Representative inward (Vtest = 0 mV) and outward currents (Vtest = 80 mV) recorded from a dysgenic myotube expressing E3K-α1C before and after application of 1 μM +SDZ 202–791. At the end of the 200-ms Vtest, the cell was repolarized to −50 mV. Inward current amplitude during the test pulse was increased by the agonist and outward current was decreased. Note that even though +SDZ 202–791 caused a decrease in outward current during the test pulse to 80 mV, inward tail currents were still potentiated upon repolarization to −50 mV. (B) After a Vtest to 20 or 100 mV, an E3K-α1C–expressing myotubes (bathed in 1 μM +SDZ 202–791) was stepped to 60 mV for 125 ms and then repolarized to −20 mV. Note that compared with the Vtest of 20 mV, the Vtest of 100 mV had little effect on the outward current at 60 mV, but substantially increased inward tail current amplitude following subsequent repolarization to −20 mV.

DISCUSSION

We have examined the potentiation by dihydropyridine agonists and strong depolarization on inward and outward whole-cell currents through L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in dysgenic myotubes. Because of the very positive reversal potential (around 90 mV) and small outward currents for wild-type cardiac (α1C-containing) L-type channels, most of the experiments were performed with α1C mutated to replace conserved pore-loop residues, either the glutamates in repeats II and IV with alanine (E2A/E4A-α1C) or the glutamate in repeat III with lysine (E3K-α1C). In agreement with previous results (Yang et al., 1993), we found that with external Ca2+ and internal Cs+ these mutated channels when expressed in dysgenic myotubes produced both inward and outward currents of substantial amplitude. Specifically for E2A/E4A-α1C, currents were inward for test potentials ranging from −20 to 10 mV and outward for potentials of ≥30 mV. Depolarization-induced potentiation was measured by comparing tail currents after a 200-ms pulse that was either moderately (20–50 mV) or strongly (90–100 mV) depolarizing. For both wild-type and mutated channels, strong depolarization had little effect on outward tail currents but caused inward tail currents to be larger and to decay more slowly. Because of this strong inward rectification, a reversal potential was difficult to determine for the component of tail current augmented by strong depolarization. However, the reversal potential of the potentiated component of tail current for E2A/E4A-α1C was shifted ∼10 mV in the depolarizing direction compared with that of nonpotentiated currents. In cells expressing E2A/E4A-α1C or E3K-α1C, exposure to DHP agonist (−BayK 8644 or +SDZ 202–791) increased the amplitude of inward currents and decreased the amplitude of outward currents, and also caused an ∼20-mV depolarizing shift in the reversal potential. Since the differential effect of DHP agonist on inward and outward currents might simply be a consequence of a dependence of the drug's action on test potential, we also examined depolarization-induced potentiation (comparing tail currents after either moderate or strong depolarization) in the presence of agonist. Just as in the absence of agonist, strong depolarization in the presence of DHP agonist had little effect on outward tail currents but increased the amplitude and slowed the decay of inward tail currents, both of which effects were more pronounced than that observed in the absence of drug.

The slowing of the decay of inward tail currents by strong depolarization in E2A/E4A-α1C– and E3K-α1C–expressing myotubes and the potentiation of these effects by DHP agonists are compatible with the idea that the potentiated channels enter into a long-lived open state. Indeed, single-channel recordings of native cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels demonstrate that DHP agonists (Hess et al., 1984) and strong depolarization (Pietrobon and Hess, 1990) cause the channels to shift from a gating pattern characterized by low open probability (termed mode 1) into a gating pattern characterized by a higher open probability and longer open times (termed mode 2). Interestingly, Kuo and Hess (1992) reported that long open-duration outward currents were not observed in cell-attached patches of cardiac myocytes or PC12 cells (Kuo and Hess, 1993a) bathed in +SDZ 202–791, even though long-duration inward currents can be routinely observed under these circumstances. This result provides additional support for the conclusion from our whole-cell measurements of pore mutant cardiac channels, that the potentiated state of the channel shows strong inward rectification. Interestingly, Kuo and Hess (1992)(1993a) found that although long duration inward, monovalent cation (Na+, Cs+, Li+) currents could be observed in cell-attached patch recordings, long open-duration outward currents could be observed only after patch excision or cell destruction (see below). With respect to long duration openings promoted by strong depolarization, Josephson et al. (2002b) found that channels displaying mode 2 gating had a 70% greater conductance than channels displaying predominantly mode 1 gating. This significant alteration of permeation is interesting in light of our observation that E2A/E4A-α1C channels potentiated by strong depolarization or DHP agonist display a positively shifted reversal potential compared with nonpotentiated channels, as if the potentiated channels have an altered selectivity. Peculiarly, the reversal potential was also positively shifted after addition of the DHP antagonist nifedipine (Fig. 3), a result that is difficult to reconcile with a mechanism whereby the only effect of the antagonist is to block channels.

As described above, Kuo and Hess (1992)(1993a) reported that long open-duration outward currents could be obtained from cardiac myocytes and PC12 cells bathed in DHP agonist, either after patch excision or after destruction of the integrity of the cell surrounding the patch. This result suggests that rectification of mode 2 openings is a consequence either of freely diffusible cytoplasmic constituents or of an intrinsic part of the channel that is rapidly modified after loss of cellular integrity. By analogy, rectification of inwardly rectifying potassium channels depends upon block by cytoplasmic Mg2+ (Matsuda et al., 1987; Vandenberg, 1987) and polyamines (Ficker et al., 1994; Lopatin et al., 1994). Indeed, Kuo and Hess (1993a)(b) suggested that divalent cytoplasmic ions in intact cells prevent the appearance of outward, unitary currents, and showed that both Ca2+ and Mg2+ blocked channels after patch excision or cell destruction. Furthermore, alteration of intracellular Mg2+ has been shown to affect the magnitude of macroscopic cardiac L-type Ca2+ current (Pelzer et al., 2001; Yamaoka et al., 2002). On the basis of these observations, we tested whether cytoplasmic Mg2+ functions as a blocking particle responsible for the rectification of potentiated L-type Ca2+ channels. This did not appear to be the case for DHP agonist, because even after the removal of cytoplasmic Mg2+, (−)BayK 8644 still potentiated inward current and partially blocked outward current via E2A/E4A-α1C. Because potentiation by DHP agonist showed rectification when both Ca2+ and Mg2+ were strongly chelated (by the combined presence of 10 mM EDTA and 10 mM EGTA), it seems that even though these divalent ions can block Ca2+ channels, neither is responsible for rectification of potentiation. Although zero Mg2+ did not reveal potentiation of outward current by DHP agonist, it did have two striking effects, (a) a strong suppression of the decay of both inward and outward currents via E2A/E4A-α1C and (b) a nearly complete elimination of depolarization-induced potentiation of inward tail currents. This result suggests that there is some mechanistic connection between the decay of current during the test pulse and the appearance of potentiation upon repolarization (for example, that the decay of outward current represents entry into the potentiated state). However, this hypothesis is inconsistent with the observation that increasing Vtest from 50 to 100 mV greatly increases entry into the potentiated state (Fig. 5 B), without much effect on the fractional decay of outward current (Fig. 7, bottom). Thus, the influence of intracellular Mg2+ on depolarization-induced potentiation may be independent of its effect on decay of current during the Vtest. In any case, our experiments do not address whether these actions of Mg2+ are directly on the channel or involve second messenger pathways involving, for example, kinases (Pelzer et al., 2001).

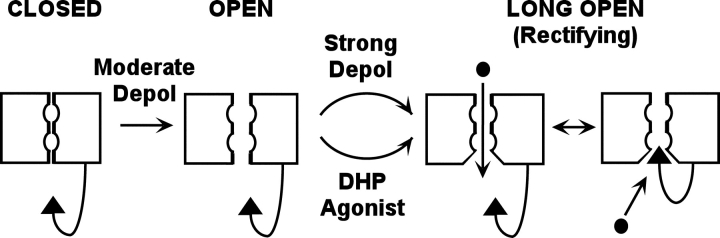

Fig. 9 illustrates a model that can account for inward rectification of channels potentiated by either agonist or strong depolarization. In principle, this model predicts that entry of channels into the potentiated state should not only increase the magnitude of inward current but also decrease the magnitude of outward current. This prediction appears to be met for DHP agonist, but not for potentiation in response to strong depolarization because Fig. 7 shows that there is little change in the fractional decay of current as a function of increasing depolarizations over the range that caused a large increase in the potentiation of inward current (Fig. 5 A). However, it is important to note that our macroscopic measurements do not allow an estimate of the fraction of all channels converted from mode 1 to mode 2 gating. Thus, it may well be that the large potentiation observed for inward current may represent the conversion of only a relatively small fraction of channels to mode 2 gating during a 200-ms strong depolarization. This would produce only a small decrement of outward current and yet a substantial increase in potentiated inward current (since mode 2 openings have a much higher Po than mode 1 openings). According to the model in Fig. 9, only depolarization and DHP agonist govern entry into mode 2, whereas Josephson et al. (2002a) reported than entry into mode 2 is influenced by the permeant ions (concentration, Ca2+ vs. Ba2+). The model in Fig. 9 is not meant to exclude this possibility. However, it seems difficult to explain our results on the basis only of permeation-dependent entry into the mode 2 open state. Specifically, the current upon repolarization to 50 mV is nearly identical whether or not it is preceded by a 200-ms depolarization to 100 mV, suggesting that the permeant ions do not differ much (see Fig. 4). Nonetheless, the channels were in fact potentiated by the prior 100-mV depolarization, as indicated by the increased magnitude and slowed decay of inward tail currents upon subsequent repolarization to −50 mV. Thus, the altered conformation induced by the step to 100 mV must have been present during the time spent at 50 mV.

Figure 9.

Model to account for preferential potentiation of inward current via L-type Ca2+ channels. Moderate depolarization causes the channel to enter an open state characterized by brief open times (mode 1 gating). Strong depolarization or DHP agonist causes the channel to enter an open state having higher open probability and longer open times (mode 2 gating). The model postulates that the long open-duration conformation differs from the short open-duration in that a site is exposed which allows entry of a cytoplasmic blocking particle. The blocking particle could be part of the channel (as depicted), or could be a diffusible cytoplasmic molecule.

In conclusion, we have found that both DHP agonists and strong depolarization promote an open state of L-type Ca2+ channels that rectifies strongly in the inward direction. This inward rectification was not a consequence of block of outward current by cytoplasmic Mg2+ because even after elimination of intracellular Mg2+ inward, but not outward, currents were potentiated by DHP agonist. By an as yet unknown mechanism, the removal of cytoplasmic Mg2+ suppressed the time-dependent decay of inward and outward currents, as well as the potentiation of inward current by strong depolarization. An important goal of future experiments will be to identify the mechanisms whereby Mg2+ regulates both current decay and depolarization-induced potentiation. Likewise, it will be important to identify the physical basis for rectification of the potentiated open state.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Parsons for performing the tissue culture.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant NS24444 to K.G. Beam and by the Foundation pour la Recherche Médicale to V. Leuranguer.

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviation used in this paper: DHP, dihydropyridine.

References

- Altier, C., R.L. Spaetgens, J. Nargeot, E. Bourinet, and G.W. Zamponi. 2001. Multiple structural elements contribute to voltage-dependent facilitation of neuronal alpha 1C (CaV1.2) L-type calcium channels. Neuropharmacology. 40:1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beam, K.G., and C.M. Knudson. 1988. Calcium currents in embryonic and neonatal mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 91:781–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet, E., P. Charnet, W.J. Tomlinson, A. Stea, T.P. Snutch, and J. Nargeot. 1994. Voltage-dependent facilitation of a neuronal alpha 1C L-type calcium channel. EMBO J. 13:5032–5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cens, T., S. Restituito, A. Vallentin, and P. Charnet. 1998. Promotion and inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation by distinct domains of the subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18308–18315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen, R.T., and K.G. Beam. 1999. Role of calcium permeation in dihydropyridine receptor function: Insights into channel gating and excitation-contraction coupling. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker, E., M. Taglialatela, B.A. Wible, C.M. Henley, and A.M. Brown. 1994. Spermine and spermidine as gating molecules for inward rectifier K+ channels. Science. 266:1068–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner, M., R.T. Dirksen, and K.G. Beam. 1998. Tagging with green fluorescent protein reveals a distinct subcellular distribution of L-type and non-L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in dysgenic myotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:1903–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, O.P., A. Marty, E. Neher, B. Sakmann, and F.J. Sigworth. 1981. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 391:85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, P., J.B. Lansman, and R.W. Tsien. 1984. Different modes of Ca2+ channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca2+ agonists and antagonists. Nature. 311:538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, I.R., A. Guia, E.G. Lakatta, and M.D. Stern. 2002. a. Modulation of the gating of unitary cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels by conditioning voltage and divalent ions. Biophys. J. 83:2575–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, I.R., A. Guia, E.G. Lakatta, and M.D. Stern. 2002. b. Modulation of the conductance of unitary cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels by conditioning voltage and divalent ions. Biophys. J. 83:2587–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.C., and P. Hess. 1992. A functional view of the entrances of L-type Ca2+ channels: estimates of the size and surface potential at the pore mouths. Neuron. 9:515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.C., and P. Hess. 1993. a. Ion permeation through the L-type Ca2+ channel in rat phaeochromocytoma cells: two sets of ion binding sites in the pore. J. Physiol. 466:629–655. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.C., and P. Hess. 1993. b. Block of the L-type Ca2+ channel pore by external and internal Mg2+ in rat phaeochromocytoma cells. J. Physiol. 466:683–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.S., and R.W. Tsien. 1983. Mechanism of calcium channel blockade by verapamil, D600, diltiazem and nitrendipine in single dialysed heart cells. Nature. 302:790–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatin, A.N., E.N. Makhina, and C.G. Nichols. 1994. Potassium channel block by cytoplasmic polyamines as the mechanism of intrinsic rectification. Nature. 372:366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H., A. Saigusa, and H. Irisawa. 1987. Ohmic conductance through the inwardly rectifying K channel and blocking by internal Mg2+. Nature. 325:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, T.F., S. Pelzer, W. Trautwein, and D.J. Pelzer. 1994. Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Physiol. Rev. 74:365–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowycky, M.C., A.P. Fox, and R.W. Tsien. 1985. Long-opening mode of gating of neuronal calcium channels and its promotion by the dihydropyridine calcium agonist Bay K 8644. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82:2178–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer, S., C. La, and D.J. Pelzer. 2001. Phosphorylation-dependent modulation of cardiac calcium current by intracellular free magnesium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281:H1532–H1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobon, D., and P. Hess. 1990. Novel mechanism of voltage-dependent gating in L-type calcium channels. Nature. 346:651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather, W.A., and E.W. McCleskey. 2003. Permeation and selectivity in calcium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65:133–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien, R.W., B.P. Bean, P. Hess, J.B. Lansman, B. Nilius, and M.C. Nowycky. 1986. Mechanisms of calcium channel modulation by β-adrenergic agents and dihydropyridine calcium agonists. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 18:691–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, C.A. 1987. Inward rectification of a potassium channel in cardiac ventricular cells depends on internal magnesium ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:2560–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, C.M., M. Grabner, and K.G. Beam. 2001. Potentiation of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel (α1C) by dihydropyridine agonist and strong depolarization occur via distinct mechanisms. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:495–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka, K., T. Yuki, K. Kawase, M. Munemori, and I. Seyama. 2002. Temperature-sensitive intracellular Mg2+ block of L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282:H1092–H1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., P.T. Ellinor, W.A. Sather, J.F. Zhang, and R.W. Tsien. 1993. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 366:158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]