Abstract

Deficiencies in early complement components are associated with the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and therefore early complement components have been proposed to influence B lymphocyte activation and tolerance induction. A defect in apoptosis is a potential mechanism for breaking of peripheral B cell tolerance, and we hypothesized that the lack of the early complement component C4 could initiate autoimmunity through a defect in peripheral B lymphocyte apoptosis. Previous studies have shown that injection of a high dose of soluble antigen, during an established primary immune response, induces massive apoptotic death in germinal centre B cells. Here, we tested if the antigen-induced apoptosis within germinal centres is influenced by early complement components by comparing complement C4-deficient mice with C57BL/6 wild-type mice. We demonstrate that after the application of a high dose of soluble antigen in wild-type mice, antibody levels declined temporarily but were restored almost completely after a week. However, after antigen-induced apoptosis, B cell memory was severely limited. Interestingly, no difference was observed between wild-type and complement C4-deficient animals in the number of apoptotic cells, restoration of antibody levels and memory response.

Keywords: apoptosis, complement, memory, SLE, tolerance

Introduction

Early components of the complement system (C1q, C2, C3 and C4) play an important role in the activation of an immune response and of B lymphocytes, and possibly in the maintenance of tolerance [1,2].

One example of failure in tolerance induction is the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is characterized by B lymphocytes producing high-affinity antibodies against self-antigens. Susceptibility to SLE is predicted by deficiency in early complement factors of the classical pathway (C1, C4 and C2) [3], which has been documented in animal models of complement deficiency [4,5] (reviewed in [6,7]).

To avoid the formation of autoreactive cells during the development of B lymphocytes, B cells must pass several checkpoints [8]. If this physiologically strictly regulated selection process is disturbed, B cells with receptors that recognize autoantigens may arise. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the correlation between complement deficiency and the genesis of autoimmunity [5,7,9]. One model postulates that lack of complement directly initiates autoimmunity by disrupting tolerance induction in B cells. This is based on the fact that the B cell co-receptor CD21 requires complement for activation [4] (reviewed in [10]). Indeed, there are several indications that failure in tolerance induction of B cells results in SLE [11,12]. Using the HEL-Ig/sHEL double-transgenic model, it was shown that induction of anergy in HEL-binding self-reactive B cells required expression of complement component C4 and the complement receptors CD21 and CD35 [4]. It is generally assumed that the process of peripheral tolerance induction is impaired in SLE [13], and it is possible that this process is altered by the lack of complement.

Apoptosis, i.e. programmed cell death, is an important mechanism for eliminating autoreactive cells during the germinal centre reaction [14–16]. B cells with low affinity or autoreactive receptors are eliminated via this mechanism. These late apoptotic cells are marked, like cells in early necrosis, by complement components [17].

During germinal centre reaction, antigen-induced apoptosis is an important type of apoptosis [18]. Previous studies have shown that the injection of a high dose of soluble antigen, during an established primary immune response (suicide experiment), induces massive apoptotic death in germinal centre B cells [18–20]. Furthermore, reduced levels of 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP)-binding IgG1− B lymphocytes, originating from the germinal centre, as well as NP-specific memory precursor cells, have been reported after this treatment [21]. However, it is not clear if NP-specific antibody production is inhibited completely during the suicide experiment.

We investigated the effects of the suicide experiment on tolerance induction in wild-type mice, and addressed whether antigen-induced splenic B cell apoptosis during germinal centre reactions is complement C4-dependent. If a lack of complement induces apoptotic defects, it would provide an opportunity for autoreactive B cells, arising from somatic hypermutation, to escape selection and induce an autoimmune response.

Methods

Mice

Mice with a targeted disruption of complement gene C4 (C4–/–) [2] and wild-type mice were used. The genetic background of the wild-type and C4–/– mice was C57BL/6 (purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Maine, USA). The C4-deficiency was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Healthy female animals between 8 and 10 weeks old were used for the studies in both groups. The German Ministry of Agriculture and Environment, Schleswig-Holstein approved all animal studies.

Induction of apoptosis

An immune response against the NP antigen and antigen-induced apoptosis were produced as described previously [18]. The experimental groups and group sizes are described in Table 1. Mice were immunized with a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 50 µg NP-(36)-CGG (36 molecules of NP bound to chicken gamma globulin; Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA, USA) precipitated with alum. On day 9 after the first immunization, 4 mg of soluble NP-(24)-bovine serum albumin (BSA) (24 molecules of NP bound to BSA; Biosearch Technologies) were administrated as a single i.p. injection. Isoprotenerol hydrochloride was injected (150 µg/kg body wt) with the NP-BSA to prevent anaphylactic reactions. Some mice were killed after 8 h and their spleens harvested, whereas other animals were bled after several days for serum analysis.

Table 1.

Scheme for size of experimental groups, treatments and analysing methods.

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | 20 wild-type | 9 wild-type | 9 wild-type | 5 wild-type | 20 C4–/– | 8 C4–/– | 8 C4–/– | 5 C4–/– |

| Day 0 (50 μg NP-CGG in alum i.p.) | 1. injection | 1. injection | – | – | 1. injection | 1. injection | – | – |

| Day 9 (4 μg NP-BSA i.p.) | 2. injection | – | 2. injection | – | 2. injection | – | 2. injection | – |

| Analysis, day 9 (spleen) | 8 wild-type | 4 wild-type | 4 wild-type | 2 wild-type | 8 C4–/– | 4 C4–/– | 4 C4–/– | 2 C4–/– |

| Analysis until day 30 (ELISA) | 12 wild-type | 5 wild-type | 5 wild-type | 3 wild-type | 12 C4–/– | 4 C4–/– | 4 C4–/– | 3 C4–/– |

| Day 180 (100 μg NP-BSA i.p.) | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection | 3. injection |

| Analysis after day 180 (ELISA) | 9 wild-type | 4 wild-type | 3 wild-type | 3 wild-type | 9 C4–/– | 3 C4–/– | 3 C4–/– | 3 C4–/– |

NP-CGG: 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl-chicken gamma globulin; i.p.: intraperitoneal; BSA: bovine serum albumin; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

For the memory experiment, an immune response against NP was established and apoptosis was induced as described previously [18] (Table 1). On day 180, mice of all groups were injected i.p. with 100 µg of soluble NP-(24)-BSA.

Detection of apoptotic cells

For detection of apoptotic cells the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) nick end labelling (TUNEL) technique [22] and immunohistochemical detection of activated-caspase-3 was performed.

For immunohistochemistry experiments, one half of each spleen was snap-frozen in embedding medium followed by cryosectioning. Tissue sections were stained using a TUNEL kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), followed by application of a specific stain (Fast Blue, Sigma, Mannheim, Germany) together with the counterstain peanut agglutinin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Sigma) for detection of germinal centre B cells. For caspase-3 staining, tissue sections were stained with a caspase-3 antibody (rabbit; Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) and a secondary antibody anti-rabbit-IgG R-phycoerythrin (RPE) after treatment with Triton-X100 and blocking with normal mouse serum (DakoCytomaticon, Glostrup, Denmark). For counterstaining peanut agglutinin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Sigma) was used. Negative controls were stained without the specific enzyme component/specific antibody. Apoptotic cells were counted by light-microscopy (TUNEL technique) or flouorescence microscopy (caspase-3 staining).

Splenic B cells for flow cytometric analysis were isolated using a lymphocyte separation medium (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria) as a first step. In a second step, T cells and macrophages were removed using magnetic beads conjugated to anti-CD11b, anti-CD90 and anti-CD11c (all Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The isolated B cells were stained with a TUNEL kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) and their purity verified by B220 and CD19-staining.

Anti-NP-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Mice were bled on days 0, 8, 9, 16, 23 and 30 (for the memory experiment on days 180, 183, 187, 194 and 201) and the sera stored at −80°C until the ELISAs were performed. Microtitre plates (CAT RPN 4905; Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) were coated with NP-(29)-KLH (Biosearch Technologies), blocked and incubated with mouse sera at various dilutions [and aliquots of polyclonal IgG or IgM (B-18) as standards] as described previously [23]. Monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgG1 (X56), IgG2a (R19-15), IgG2b (R12-3), IgG3 (R40-82) (all from Pharmingen) and polyclonal anti-IgM (Sigma) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase were used as secondary antibodies. p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma) was used as a substrate and the absorbance measured at 405 nm.

Results

Primary and secondary immune responses in wild-type and C4-deficient mice

Before analysing the effect of C4-deficiency on B cell apoptosis, ELISA was used to measure the primary and secondary immune responses elicited by the hapten antigen NP in wild-type and C4–/– mice. To exclude the possibility of an immune response against the carrier, NP was conjugated to different proteins for the 1st and 2nd injections, as well for the analysis [chicken gamma globulin (CGG), BSA and keyhole-limpet haemocyanine (KLH)].

The immune response of both mouse strains consisted primarily of the Ig-subclasses IgM, IgG1 and partly IgG2b (data not shown). Analysis of these Ig-subclasses showed that during the primary immune response, IgM production occurred independently of complement C4. However, IgG production was reduced significantly in the C4–/– mice (Fig. 1). During the secondary immune response, there was no difference in the dominant subclass (IgG1) between C4–/– and wild-type mice (Fig. 1). Only the levels of the subclass IgG2b were significantly reduced in the C4–/– mice when compared with wild-type mice.

Fig. 1.

Primary and secondary immune response in wild-type and C4–/– mice measured by anti-4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP)-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Experimental groups (see also Table 1) were treated differently on day 0 and 9: (a) (wild-type) and (e) (C4–/–): suicide experiment [injection of 50 µg NP-chicken gamma globulin (CGG) in alum intraperitoneally (i.p.) on day 0 and of 4 mg NP-bovine serum albumin (BSA) i.p. on day 9], (b) (wild-type) and (f) (C4–/–): injection of an immunogenic dose of antigen (50 µg NP-CGG precipitated in alum i.p) on day 0, (c) (wild-type) and (g) (C4–/–): injection of a high dose of antigen (4 mg NP-BSA i.p) on day 9, (d) (wild-type) and (h) (C4C4–/–): no treatment before day 180. All mice were injected with 100 µg NP-BSA on day 180. IgG production was significantly reduced in the C4–/– mice, but during the secondary immune response there was no difference in the dominant subclass IgG1 between C4–/– and wild-type mice (a, b, e and f). We also show here that the antigen dose used for inducing the secondary immune response did not induce a significant IgG production in untreated mice, besides the mice that had previously undergone a primary immune response. A single injection of a high dose of antigen did not induce an immune response in wild-type and C4–/– mice. Injected with 100 µg NP-BSA on day 180, the mice reacted as previously untreated mice did, showing no sign of a secondary immune response (c and g).

We show here that the antigen dose used for the induction of the secondary immune response did not induce a significant IgG production in untreated mice. However, the dose did induce a secondary immune response in mice that had previously undergone a primary immune response, even though the extent of this secondary immune response did not reach the level of the primary response (Fig. 1). This is explained by the fact the antigen had been alum precipitated before the first injection, which enhances the response, but the alum precipitation step was omitted before the second injection.

High-zone tolerance in wild-type and C4-deficient mice

A single injection of a high dose of antigen (4 mg, groups C and G) did not induce an antigen-specific immune response in the wild-type and C4–/– mice, in contrast to mice injected with an immunogenic dose of antigen (100 µg NP-CGG, data not shown). Injected with 100 µg NP-BSA on day 180, the mice reacted as did previously untreated mice, showing no sign of a secondary immune response (Fig. 1).

Influence of the suicide experiment on the primary and secondary immune response

In order to determine whether antigen-induced apoptosis is an important mechanism for inducing tolerance in the germinal centre, we investigated the effect of the suicide experiment on the primary and secondary immune responses against NP in wild-type mice. Our data from wild-type mice show that application of a high dose of soluble antigen on day 9 of a primary immune response resulted in an interruption of the immune response, measured by a decline in the levels of NP-specific IgM, IgG1 and IgG2b. However, the production of specific antibodies was not completely abrogated, as IgG1 levels reached up to 85% and IgG2b levels reached up to 50% of the undisturbed immune response 1 week after the application of the high antigen dose (Fig. 1, group A versus group B).

No antibodies were detectable after 6 months, prior to the induction of a secondary immune response.

The IgM-production during the secondary immune response was not influenced by the interruption of the primary immune response in the suicide experiment (data not shown). However, the data showed that after 6 months, B cell memory function was reduced significantly as a result of antigen-induced apoptosis, as judged by the production of IgG subclasses (Fig. 1).

To assess whether complement C4-deficiency influenced B lymphocyte apoptosis, we measured antibody production after the suicide experiment in C4–/– and wild-type mice. The absolute antibody titre in the complement-deficient mice was reduced in comparison to wild-type mice. Therefore, we calculated the re-increase after the antigen-induced interruption on day 9 as percentage of the antibody level on day 8 (normal primary immune response). The calculated values represent an indirect marker for the apoptosis rate of antigen-specific B cells in mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Re-increase in 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP)-specific antibody levels after the suicide experiment in wild-type and C4–/– mice as an indirect marker for the apoptosis of antigen-specific B cells measured by anti-NP-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The left graph shows the IgG1 response, while the right graph shows IgG2b. Both groups (wild-type and C4–/–) were injected on day 0 with 50 µg NP-chicken gamma globulin (CGG) in alum intraperitoneally (i.p.), and on day 9, at the high of the immune response, with 4 mg NP-bovine serum albumin (BSA) i.p. Specific B cells were not eliminated completely, because their IgG1 and IgG2b levels re-increased after 1 week (*p < 0·05).

In C4–/– mice, following antigen-induced apoptosis, the IgG-antibody levels reached up to 44% for IgG1 and up to 40% for IgG2b of an undisturbed immune response. Only on day 16 did the C4–/– mice show a significantly reduced IgG1 response when compared to wild-type mice. After the suicide experiment, the C4–/– mice produced even more NP-specific IgM-class antibodies than wild-type mice (data not shown).

In order to measure the effects of antigen-induced apoptosis on a secondary immune response, we compared the secondary immune responses of wild-type and C4–/– mice 180 days after the animals had undergone the suicide experiment during their first immune response. Under these conditions, we found no decrease in memory response in the C4–/– mice when compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1).

A direct analysis of the number of apoptotic B cells in wild-type and C4-deficient mice

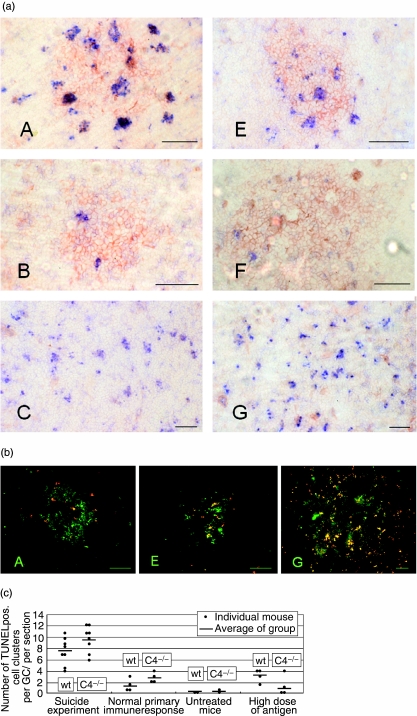

In a parallel approach, we measured the number of apoptotic B cells in the different groups of wild-type and C4–/– mice by immunohistochemical (Fig. 3) and flow cytometric analyses of the spleens (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

(a) Immunohistochemical staining for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) nick end labelling (TUNEL) (blue, detection of apoptotic cells) and peanut agglutinin (red, staining of germinal centre B cells) of the murine spleen (the bar corresponds to 50 µm). Images are labelled according to experimental group (D and H data not shown). In groups A (wild-type) and E (C4–/–) (suicide experiment) several apoptotic cell cluster occurred within the germinal centres. In groups B (wild-type) and F (C4–/–) (normal primary immune response) fewer TUNEL positive clusters were observed. In groups C (wild-type) and G (C4–/–), which had received only a high dose of antigen without any previous immunization, apoptotic cells were found throughout the red and white pulp of their spleens. (b) Immunohistochemical staining for caspase 3 (red, detection of apoptotic cells) and peanut agglutinin (green, staining of germinal centre B cells) of the murine spleen (the bar corresponds to 50 µm). Images are labelled according to experimental group. In groups A (wild-type) and E (C4–/–) (suicide experiment) several apoptotic cell cluster occurred within the germinal centres. In groups C (wild-type, data not shown) and G (C4–/–), which had received only a high dose of antigen without any previous immunization, apoptotic cells were found throughout the red and white pulp of their spleens. (c) Number of apoptotic cell clusters in wild-type and C4–/– mice (number of TUNEL positive cell clusters per GC/per section in immunohistochemistry). After the injection of a high dose of antigen during an established immune response (suicide experiment) many apoptotic cells were present in the splenic germinal centres. In the spleens of mice on day 9 of an ongoing immune response of untreated mice and of mice which received only a high dose of antigen, no significant difference (P < 0·05) could be identified in the number of apoptotic cells in the germinal centres between the C4–/– and the wild-type mice.

These data confirm that many apoptotic cells were present in the splenic germinal centres after the injection of a high dose of antigen during an established immune response.

In the spleens of untreated mice, of mice on day 9 of an ongoing immune response and of mice in which the immune response had been interrupted on day 8 (suicide experiment), no significant differences could be identified in the number of apoptotic cells in the germinal centres between the C4–/– and the wild-type mice (Fig. 3c).

Interestingly, mice that had received only a high dose of antigen without any previous immunization (C4–/– and wild-typet) had apoptotic cells throughout the red and white pulp of their spleens (groups C and G). This effect could be seen using TUNEL technique as well as activated caspase-3 staining for detection of apoptotic cells (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

The influence of early complement components (C1q, C4 and C3) on the activation of a specific immune response [1], as well as the susceptibility to autoimmune diseases through deficiencies in these components [6,7], are well known. One hypothesis for the correlation between complement deficiency and autoimmunity postulates that early complement components are required for the induction and maintenance of peripheral tolerance. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that lack of the complement receptors CD21/CD35 or complement C4 leads to a defect in B cell anergy or increased autoreactivity in two independent models (lpr/lpr and the HEL-Ig/sHEL double-transgenic model) [4]. On the other hand, in C1q–/– mice these results could not be confirmed in the HEL-Ig/sHEL double-transgenic model [24].

Self-reactive B cells arising from somatic hypermutation in the germinal centre die by apoptosis, making apoptosis a critical mechanism for inducing tolerance [16]. However, the signals that determine the faith of B cells have not yet been characterized fully. One proposed mechanism is antigen-induced apoptosis [18], whereby B cells whose receptors recognize a soluble, plentiful antigen die. Previous studies suggest that the application of a high dose of soluble antigen, before, during or after induction of an immune response against this antigen, induces a specific form of tolerance [21,25,26]. An experimental model for these events is the suicide experiment (injection of a high dose of antigen during an established immune response against the antigen [18–20]). The importance of other apoptosis-inducing mechanisms, such as stimulation via a death-receptor (Fas/CD95), remains a matter of controversy [16,27].

The present study was designed to define the role of complement C4 in antigen-induced apoptosis, and its effects on primary and secondary immune responses. This approach was chosen to test the hypothesis that lack of the early complement component C4 could initiate autoimmunity through a defect in antigen-induced apoptosis in peripheral B lymphocytes.

First, we compared the primary and secondary immune responses of wild-type and C4–/– mice against NP, a hapten antigen coupled to the T cell-dependent carrier protein, NP-CGG.

Our data showed that the immune responses of both mice strains affected mainly the Ig-subclasses IgM, IgG1 and partially IgG2b, consistent with previously reported data [28]. As expected, the primary IgG immune response against NP-CGG, precipitated with alum, was lower in C4–/– animals when compared to wild-type mice, probably a result of reduced CD21 co-stimulation. However, during the secondary immune response to the NP antigen, the IgG1 production of C4–/– mice was similar to that observed in wild-type mice, and not reduced as a consequence of the complement-deficiency. These results conflict with several reports showing reduced primary [2] and secondary [29–31] immune responses in complement-deficient mice (C3–/–, C4–/– or Cr2–/–). However, our data are consistent with a new study showing the number and function of memory B cells are normal in Cr2–/– mice [32]. The antigen used for the induction of the primary immune response in this study was precipitated with alum. The enhancing effect of alum precipitation was not sufficient to induce similar antibody levels in wild-type and C4–/– mice during the primary antibody response. None the less, it is possible that alum precipitation activates other pathways for generation of memory B cells, independent of complement [33], for instance, via T cell help and activation of the CD40 ligand [34]. Alternatively, our results suggest that reactivation of memory B cells during a secondary immune response does not require co-stimulation of CD21 by complement C4. The phenotype of memory B cells (whether or not they bear CD21) remain controversial. Some studies indicate that different memory-populations express CD21 at high or low levels [35,36]. In conclusion, we confirm that a primary immune response is dependent upon complement C4, even if an alum-precipitated antigen is used for immunization, whereas complement C4 appears not to be required for inducing and maintaining a B cell memory response.

Next, we analysed and compared the primary and secondary immune responses of C4–/– mice with wild-type mice in response to a single high antigen dose. A single dose of 4 mg NP-BSA was used for the primary immunization and it triggered massive apoptosis in the spleen within 8 h. The apoptotic cells were distributed evenly in the red and white pulp of the spleen, and these did not seem to be NP-specific B cells, as the mice had not encountered the antigen previously. The high antigen dose did not induce NP-specific antibody production, nor did it initiate the formation of memory B cells. This observation could be explained by the well-documented effect of high-zone tolerance [37–39]. Again, no difference was observed between C4–/– and wild-type mice with respect to number of apoptotic cells and antibody response. However, the specific mechanisms triggering apoptosis following a high antigen dose, in the absence of specific antigen receptors, remain unclear.

Finally, we perturbed an ongoing immune response against NP-CGG precipitated with alum by injection of a high dose of NP-BSA, and analysed the effect of lack of complement C4 on apoptosis induction within the spleen and on antibody production. The experiments confirm that within germinal centres clusters of cells die by apoptosis within 8 h of injection of a high antigen dose. However, direct immunohistochemical (TUNEL) and flowcytometric analysis showed no difference in the number of apoptotic cells in the splenic germinal centres of wild-type and C4–/– mice.

In addition to induction of apoptosis, we observed a significant decrease in NP-specific antibodies in sera from both C4–/– and wild-type mice, which was followed by a partial regain during the following days. These results prove that the decrease was temporary. This can be explained by an interaction between the injected antigen and the circulating antigen-specific antibodies. As the antibody levels regained, we speculate that only a part of the NP-specific B cells died during antigen-induced apoptosis. Thus, the antigen-induced apoptosis model may not represent an essential role for induction of B cell tolerance, once an immune response is initiated. The fact that we did not find a significant difference between C4–/– and wild-type mice suggests that mediators of antigen-induced apoptosis are independent of complement, unless there is an alternative complement activation.

In contrast, after 6 months, the memory function of B cells was reduced significantly, although not completely absent in mice which had received a high antigen dose. Again, no difference was observed between C4–/– and wild-type mice. This suggests that evolving memory B cells are the main target of apoptosis, and that by day 8 the antibody secreting cells have already left the germinal centre. This idea is supported by previous studies documenting reduced numbers of NP-specific memory precursor cells [21].

In conclusion, we have confirmed that a primary antibody response is diminished in the absence of complement C4, and that this complement component appears non-essential for a secondary immune response.

On day 8, following an injection of a high antigen dose, the initial humoral immune response was abrogated and a massive induction of apoptosis was observed within germinal centres of wild-type and C4–/– mice. However, within a few days, the antibody levels increased to near normal levels. By contrast, the high dose of antigen was able to reduce the memory response significantly in both mice strains,suggesting that evolving memory B cells are the main target of apoptosis and that antibody-secreting cells have left the germinal centre by day 8.

We conclude that antigen-induced apoptosis acts independently of complement C4. This is based on two observations: wild-type and C4–/– animals showed similar declines and increases in antibody levels after an injection of a high antigen dose, and they had similar levels of apoptotic cells.

Therefore, it is unlikely that tolerance induction of B cells in germinal centres is influenced by early complement components, mediated by defects in antigen-induced apoptosis. Taken together, these results suggest that the checkpoint leading to loss of tolerance, in the absence of early complement components, does not involve direct interaction of antigen with a B cell receptor or the co-receptors CD21/CD35. Consequently, other features of the complement system must be responsible for the loss of tolerance, perhaps a waste disposal defect [7] or the induction of interferon alpha [40].

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful for excellent technical assistance to Kirsten Jacobsen. This study has been supported by the science programme of the medical faculty, University of Luebeck.

References

- 1.Pepys MB. Role of complement in induction of the allergic response. Nat New Biol. 1972;237:157–9. doi: 10.1038/newbio237157a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer MB, Ma M, Goerg S, et al. Regulation of the B cell response to T-dependent antigens by classical pathway complement. J Immunol. 1996;157:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson JP. Complement deficiency: predisposing factor to autoimmune syndromes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1989;7(Suppl. 3):S95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prodeus AP, Goerg S, Shen LM, et al A. critical role for complement in maintenance of self-tolerance. Immunity. 1998;9:721–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botto M, Dell'Agnola C, Bygrave AE, et al. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agnello V. Lupus diseases associated with hereditary and acquired deficiencies of complement. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1986;9:161–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manderson AP, Botto M, Walport MJ. The role of complement in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:431–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodnow CC, Adelstein S, Basten A. The need for central and peripheral tolerance in the B cell repertoire. Science. 1990;248:1373–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2356469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz LE, Herrmann M, Gaipl US. An impaired clearance of dying cells can lead to the development of chronic autoimmunity. Z Rheumatol. 2005;64:370–6. doi: 10.1007/s00393-005-0769-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gommerman JL, Carroll MC. Negative selection of B lymphocytes: a novel role for innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:120–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917312.x. 120–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.William J, Euler C, Primarolo N, Shlomchik MJ. B cell tolerance checkpoints that restrict pathways of antigen-driven differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:2142–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan J, Mamula MJ. B and T cell tolerance and autoimmunity in autoantibody transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 2002;14:963–71. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.William J, Euler C, Leadbetter E, Marshak-Rothstein A, Shlomchik MJ. Visualizing the onset and evolution of an autoantibody response in systemic autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:6872–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roark JH, Kuntz CL, Nguyen KA, Caton AJ, Erikson J. Breakdown of B cell tolerance in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1157–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathmell JC, Cooke MP, Ho WY, et al. CD, 95 (Fas)-dependent elimination of self-reactive B cells upon interaction with CD4+ T cells. Nature. 1995;376:181–4. doi: 10.1038/376181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch S, Boyd M, Malone B, Gonye G, Schwaber J, Schwaber J. Fas-mediated apoptosis eliminates B cells that acquire self-reactivity during the germinal center response to NP. Cell Immunol. 2000;203:103–10. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaipl US, Sheriff A, Franz S, et al. Inefficient clearance of dying cells and autoreactivity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;305:161–76. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29714-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han S, Zheng B, Dal Porto J, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl) acetyl. IV. Affinity-dependent, antigen-driven B cell apoptosis in germinal centers as a mechanism for maintaining self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1635–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulendran B, Kannourakis G, Nouri S, Smith KG, Nossal GJ. Soluble antigen can cause enhanced apoptosis of germinal-centre B cells. Nature. 1995;375:331–4. doi: 10.1038/375331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shokat KM, Goodnow CC. Antigen-induced B cell death and elimination during germinal-centre immune responses. Nature. 1995;375:334–8. doi: 10.1038/375334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nossal GJ, Karvelas M, Pulendran B. Soluble antigen profoundly reduces memory B cell numbers even when given after challenge immunization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3088–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darzynkiewicz Z, Juan G, Li X, Gorczyca W, Murakami T, Traganos F. Cytometry in cell necrobiology: analysis of apoptosis and accidental cell death (necrosis) Cytometry. 1997;27:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachrau B, Finke D, Kropf K, Gosink HJ, Kirchner H, Goerg S. Antigen localization within the splenic marginal zone restores humoral immune response and IgG class switch in complement C4-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1685–90. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutler AJ, Cornall RJ, Ferry H, Manderson AP, Botto M, Walport MJ. Intact B cell tolerance in the absence of the first component of the classical complement pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2087–93. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2087::aid-immu2087>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claman HN, Bronsky EA. Production of tolerance in immunized mice and the effects of immunosuppression. J Allergy. 1966;38:208–14. doi: 10.1016/0021-8707(66)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulendran B, Karvelas M, Nossal GJ. A form of immunologic tolerance through impairment of germinal center development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2639–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rathmell JC, Goodnow CC. Effects of the lpr mutation on elimination and inactivation of self-reactive B cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:2831–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jack RS, Imanishi-Kari T, Rajewsky K. Idiotypic analysis of the response of C57BL/6 mice to the (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl) acetyl group. Eur J Immunol. 1977;7:559–65. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830070813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottger EC, Metzger S, Bitter-Suermann D, Stevenson G, Kleindienst S, Burger R. Impaired humoral immune response in complement C3-deficient guinea pigs: absence of secondary antibody response. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:1231–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830161008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Da Costa XJ, Brockman MA, Alicot E, et al. Humoral response to herpes simplex virus is complement-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12708–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrington RA, Pozdnyakova O, Zafari MR, Benjamin CD, Carroll MC. B lymphocyte memory: role of stromal cell complement and FcgammaRIIB receptors. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1189–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gatto D, Pfister T, Jegerlehner A, Martin SW, Kopf M, Bachmann MF. Complement receptors regulate differentiation of bone marrow plasma cell precursors expressing transcription factors Blimp-1 and XBP-1. J Exp Med. 2005;201:993–1005. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Jiang N, Fang YF, et al. Impaired affinity maturation in Cr2–/– mice is rescued by adjuvants without improvement in germinal center development. J Immunol. 2000;165:3119–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siepmann K, van Skok JED, Harnett M, Gray D. Rewiring of CD40 is necessary for delivery of rescue signals to B cells in germinal centres and subsequent entry into the memory pool. Immunology. 2001;102:263–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obukhanych TV, Nussenzweig MC. T-independent type II immune responses generate memory B-cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:305–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindsten T, Yaffe LJ, Thompson CB, et al. The role of complement receptor positive and complement receptor negative B cells in the primary and secondary immune response to thymus independent type 2 and thymus dependent antigens. J Immunol. 1985;134:2853–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matis LA, Glimcher LH, Paul WE, Schwartz RH. Magnitude of response of histocompatibility-restricted T-cell clones is a function of the product of the concentrations of antigen and Ia molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6019–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swinton J, Schweitzer AN, Anderson RM. Two signal activation as an explanation of high zone tolerance: a mathematical exploration of the nature of the second signal. J Theor Biol. 1994;169:23–30. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weigle WO. Immunological unresponsiveness. Adv Immunol. 1973;16:61–122. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finke D, Randers K, Hoerster R, et al. Elevated levels of endogenous apoptotic DNA and Interferon alpha in complement C4 deficient mice: implications for induction of SLE. Eur J Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/eji.200636719. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]