Abstract

Stress-like elevations in plasma glucocorticoids rapidly inhibit pulsatile LH secretion in ovariectomized sheep by reducing pituitary responsiveness to GnRH. This effect can be blocked by a nonspecific antagonist of the type II glucocorticoid receptor (GR) RU486. A series of experiments was conducted to strengthen the evidence for a mediatory role of the type II GR and to investigate the neuroendocrine site and cellular mechanism underlying this inhibitory effect of cortisol. First, we demonstrated that a specific agonist of the type II GR, dexamethasone, mimics the suppressive action of cortisol on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH pulses in ovariectomized ewes. This effect, which became evident within 30 min, documents mediation via the type II GR. We next determined that exposure of cultured ovine pituitary cells to cortisol reduced the LH response to pulse-like delivery of GnRH by 50% within 30 min, indicating a pituitary site of action. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that suppression of pituitary responsiveness to GnRH in ovariectomized ewes is due to reduced tissue concentrations of GnRH receptor. Although cortisol blunted the amplitude of GnRH-induced LH pulses within 1–2 h, the amount of GnRH receptor mRNA or protein was not affected over this time frame. Collectively, these observations provide evidence that cortisol acts via the type II GR within the pituitary gland to elicit a rapid decrease in responsiveness to GnRH, independent of changes in expression of the GnRH receptor.

ASSOCIATED WITH EXPOSURE to many types of stress are impairment of reproductive neuroendocrine function (1,2,3) and simultaneous activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in enhanced glucocorticoid secretion (4,5,6). Although glucocorticoids are considered important mediators of the suppression in reproductive activity, the neuroendocrine site and mechanism of action remain unclear. Recent studies have determined that increased secretion of cortisol is necessary for rapid (within 30 min) suppression of pituitary responsiveness to GnRH in sheep exposed to an acute psychosocial stress (7). This effect is blocked by antagonism of the type II glucocorticoid receptor (GR), providing initial evidence that cortisol action is mediated via this receptor (8).

Here, we present a series of experiments to investigate the neuroendocrine site and cellular mechanism of cortisol action. First, because previous evidence for mediation via the type II GR was obtained using RU486, a nonspecific antagonist, we sought to confirm the relevance of this receptor by determining whether a specific type II GR agonist mimics the effect of cortisol in decreasing responsiveness to GnRH. Next, we used an ovine pituitary cell culture system to determine whether cortisol can elicit this action directly on pituitary cells. This was deemed important in light of recent evidence that the effect of cortisol on responsiveness to GnRH is not expressed if the hypothalamus is surgically disconnected from the pituitary (9), raising the possibility that cortisol acts indirectly via a central mechanism. Finally, because chronic exposure to cortisol can inhibit expression of the GnRH receptor (10), we tested the hypothesis that the rapid inhibitory action of cortisol on responsiveness to GnRH results from reduced GnRH receptor mRNA and protein.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mature Suffolk ewes were ovariectomized at least 5 months before each experiment and maintained under standard husbandry conditions at the Sheep Research Facility near Ann Arbor, MI. The ewes were fed hay and alfalfa pellets and had free access to water and mineral licks. All procedures were approved by the Committee for the Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

Experiment 1: does a type II GR agonist mimic the inhibitory action of cortisol on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH?

Animal model and design.

We employed a pituitary clamp model used previously to demonstrate the inhibitory action of cortisol on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH (8,11). Specifically, pulsatile GnRH secretion was chronically blocked in ovariectomized ewes by constant delivery of a luteal-phase level of estradiol via a 3-cm sc SILASTIC brand (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) implant during seasonal anestrus (12). Physiological GnRH pulses (5 ng/kg, iv, over 6 min; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) were infused hourly via a timer-regulated pump for 6 d to reactivate the gonadotrope and stabilize pituitary responsiveness to GnRH. On d 7 of pulsatile GnRH treatment, blood was sampled via jugular cannula at 12-min intervals for 12 h to assess LH pulse amplitude as an index of pituitary responsiveness to the exogenous GnRH pulses. For the first 6 h, no additional treatment was applied. During the next 6 h, cortisol (0.125 mg/kg·30 min, Solu-Cortef, hydocortisone sodium succinate; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) (n = 4 ewes) or dexamethasone (0.125 mg/kg·30 min, dexamethasone sodium phosphate; American Pharmaceutical Partners, Inc., Schaumburg, IL) (n = 7 ewes), suspended in 1 ml sesame oil, was injected sc every 30 min in an area of loose skin on the back. A vehicle or time control was not included due to limited resources and our repeated previous observation that neither vehicle nor time during the sampling period influenced plasma cortisol concentrations or the response to GnRH in this pituitary clamp model (8,11) (also see results of experiment 3 of this study).

Data analysis.

Amplitudes of GnRH-induced LH pulses (peak minus preceding nadir) were averaged before and during cortisol or dexamethasone treatment and analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA (rmANOVA) to determine whether these glucocorticoids reduce responsiveness to GnRH. Mean plasma cortisol concentrations before and during treatment were analyzed by rmANOVA. Hormone values were log transformed before statistical analysis to adjust for heterogeneity of variance. Significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Experiment 2: can cortisol act directly upon pituitary cells to inhibit responsiveness to GnRH?

Tissue culture.

Ovine pituitary glands, obtained from a local abattoir (Wolverine Packing Co., Detroit, MI; December to March), were enzymatically dissociated using a two-step collagenase-viokase digestion procedure (Sigma) (13). Dispersed cells were plated (5.0 × 105 cells per well) in DMEM, supplemented with l-glutamine (1 ml/liter), gentamycin (400 μl/liter), fungisone (1 ml/liter), 10% horse serum, and 2.5% fetal calf serum (all reagents obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Cultures were maintained at 37 C under 5% CO2. On d 5, medium was changed to serum-free DMEM, and LH responses to repeated hourly boluses of GnRH were determined in the presence or absence of cortisol. To simulate GnRH pulses in vitro, cultures were exposed to medium devoid of GnRH for 50 min followed by medium containing GnRH (4 ng/ml; Sigma) for 10 min. After each 10-min GnRH bolus, medium was removed and stored at −20 C for LH assay. This GnRH exposure was designed to approximate the duration and concentration of a natural GnRH pulse in pituitary portal blood of ovariectomized ewes (14). A preliminary study confirmed the efficacy of 10 min exposure to increasing concentrations of GnRH (0.25, 1.0, and 4.0 ng/ml) in enhancing LH release into the medium (3.0 ± 1.6, 5.6 ± 1.0, 8.8 ± 0.9 ng/ml increase over basal values, respectively; n = 2 independent experiments each performed in sextuplicate).

Experimental design.

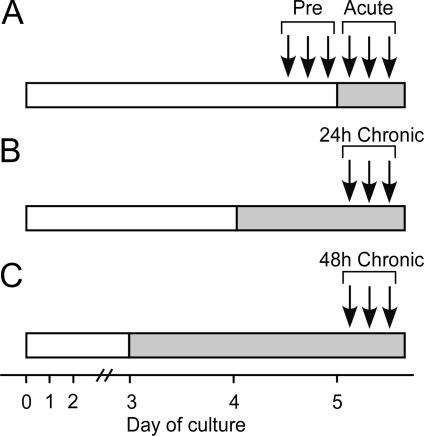

To determine the effect of acute cortisol exposure on responsiveness to GnRH in vitro, cultures were challenged with six hourly boluses of GnRH (4.0 ng/ml, 10 min) on d 5 of culture. For the first three boluses, no additional treatment was applied (Fig. 1A, pre period). Beginning 30 min after the third GnRH bolus and continuing for the next three hourly GnRH boluses (acute period), cells were cultured in medium containing 150 ng/ml cortisol (Pharmacia & Upjohn) or medium alone. To investigate effects of chronic cortisol, additional cells were treated with medium containing cortisol or medium alone during the final 24 or 48 h of culture before testing responsiveness to three hourly GnRH boluses (Fig. 1, B and C, 24- or 48-h chronic period). The cortisol concentration in medium mimicked maximal plasma cortisol levels in ewes during an acute immune/inflammatory stress (15). Basal LH concentrations were determined at corresponding times in medium of untreated cultures and subtracted from GnRH-stimulated LH responses before data analysis.

Figure 1.

Design for primary ovine pituitary cell culture experiment. Time is depicted as day of culture. Open horizontal bar indicates treatment with medium alone. Shaded horizontal bar depicts initiation of treatment with cortisol (150 ng/ml) before testing responsiveness to GnRH on d 5. Arrows designate timing of repeated, hourly boluses of GnRH (4 ng/ml, 10 min). A, GnRH boluses were administered before (pre) and immediately after treatment onset with cortisol or medium alone (acute); B and C, GnRH boluses were administered either 24 or 48 h, respectively, after chronic treatment with cortisol or medium alone.

Data analysis.

Results represent the mean ± sem of four independent experiments (n = 4) each performed in sextuplicate. Hourly LH responses (increase over basal values) were log transformed, averaged within each 3-h time period and analyzed by rmANOVA (pre vs. 3-h acute cortisol) to determine effects of acute cortisol or one-way ANOVA (medium alone vs. 24- or 48-h chronic cortisol) to determine effects of chronic cortisol. The rapidity of cortisol action was determined by comparing individual LH responses during the acute cortisol period to the pretreatment mean by rmANOVA.

Experiment 3: does cortisol reduce pituitary concentrations of GnRH receptor?

Part 1 (endogenous GnRH pulse model).

During the nonbreeding season, blood was collected from 14 ovariectomized ewes via jugular cannula for 6 h at 10-min intervals for assessment of LH pulse amplitude. For the first 3 h, no treatment was applied. During the final 3 h of sampling, vehicle (sesame oil) or cortisol (0.125 mg/kg in vehicle; Pharmacia & Upjohn) was administered by sc injection every 30 min (n = 7 per group). Immediately after sampling, ewes were injected with a barbiturate overdose (Fatal Plus; Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI), and the pituitary gland was removed, divided midsagittally, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 C for measurement of GnRH receptor protein and pituitary LH.

Part 2 (pituitary clamp model).

Part 1 demonstrated that cortisol lowered LH pulse amplitude but not tissue concentrations of the GnRH receptor. Part 2 was conducted to confirm this finding using a more powerful animal model that allowed precise control of the GnRH stimulus and to analyze acute cortisol effects on GnRH receptor gene expression as well as protein content.

The pituitary clamp model described in experiment 2 was employed here. Eighteen ovariectomized ewes received hourly GnRH boluses for 6 d to stabilize gonadotrope responsiveness. Beginning 3 h before blood sampling on d 7, the ewes were disconnected from the GnRH pump, and the hourly boluses of GnRH were delivered manually (over 20 sec) via jugular cannula. This allowed sampling at more precise times relative to delivery of a GnRH pulse. While continuing to receive pulsatile delivery of GnRH, blood was sampled via jugular catheter at 10-min intervals for 5 h. For the first 3 h, all ewes (n = 18) received continuous infusion of vehicle (saline). During the latter 2 h, half the ewes received continuous infusion of cortisol (0.40 mg/kg·h; Pharmacia & Upjohn) (n = 9 per group). Cortisol was administered by continuous iv infusion (as opposed to sc injection used in part 1) to decrease the latency in achieving a target plasma cortisol level of approximately 125 ng/ml. Thirty minutes after the final GnRH injection, ewes were euthanized, and the pituitary was collected for measurement of GnRH receptor protein and mRNA as described for part 1.

Isolation and quantification of mRNA.

Total cellular RNA was obtained from one half of each pituitary gland using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Integrity of the RNA was determined by OD absorption ratio OD260nm:OD280nm between 1.7 and 2.0. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg total RNA with iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

PCR primers to detect the ovine GnRH receptor were designed from the known ovine sequence (GenBank accession nos. L43841, L43842, and L42937) reported by Campion et al. (16). Forward and reverse primers for the ovine GnRH receptor were 5′-ACCAGGCCTCTAGCAGTGAA-3′ and 5′-CTTTTTCACCTTCAGCTGCC-3′, respectively. Forward and reverse primers for actin (housekeeping gene) were 5′-TCTGGCACCACACCTTCTAC-3′ and 5′-GGTCATCTTCTCACGGTTGG-3′, respectively. Each primer pair was validated to ensure amplification of the proper size DNA fragment and that no amplification of genomic DNA occurred. PCR products were subcloned into pGemT Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and the plasmids were sequenced to confirm the identity of both ovine GnRH receptor and actin DNA fragments.

Real-time PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad iCycler under the following conditions: 95 C for 3 min, followed by 36 cycles of 95 C for 30 sec, 59 C for 30 sec, and 72 C for 60 sec. Separate reactions were made to amplify GnRH receptor and actin and consisted of 10% of the cDNA synthesis reaction added to 300 nm of each primer in iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). A standard curve for each primer set consisted of four serial dilutions (1:10) of sequenced PCR product. All samples were tested in duplicate within a single run. Values for GnRH receptor gene were standardized to actin and expressed as relative units. A melting curve analysis was performed to confirm that a single amplicon was generated in each reaction, and its size (226 and 105 bp, GnRH receptor and actin, respectively) was verified by gel electrophoresis.

GnRH receptor protein analysis.

One half of each pituitary gland was used to prepare individual partially purified membrane fractions from which GnRH receptor concentration was quantified according to the standard curve technique of Nett et al. (17). Briefly, a standard curve was generated by incubating increasing quantities of a bovine pituitary membrane pool with 0.2 nm [125I]d-Ala6-GnRH-Pro9-ethyl-amide ([125I]d-Ala6). The amount of specifically bound [125I]d-Ala6 in each pituitary membrane preparation was compared with the standard curve, and the concentration of GnRH receptor was calculated. All samples within part 1 or 2 were run in duplicate in a single assay. Results are expressed as total receptor concentration (free plus bound) per milligram pituitary.

Data analysis.

Pituitary concentrations of LH, GnRH receptor protein, and GnRH receptor mRNA were compared by one-way ANOVA to assess an effect of cortisol. LH pulse amplitude, frequency, and mean LH concentration before and during treatment in each ewe were compared by rmANOVA. In part 1, endogenous LH pulses were identified using the Cluster pulse-detection algorithm (18). Cluster sizes for peaks and nadirs were set at 1 and the t statistic used to identify a significant increase and decrease was 2.6. Hormone values were log transformed, and square root transformation of pulse frequencies was preformed before statistical analysis.

Hormone analyses

LH concentrations were determined in duplicate aliquots (25–100 μl) of plasma, cell culture medium, or pituitary homogenate using a modification (19) of a previously described RIA (20,21). Values for plasma and cell culture medium are expressed in terms of NIH-oLH-S12. Mean intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 4.0 and 6.0%, respectively; assay sensitivity averaged 0.60 ng/ml (32 assays). Values for pituitary homogenates were determined in a single assay and are expressed in terms of NIH-oLH-S24; intraassay coefficient of variation was 5.0%, and assay sensitivity was 0.61 ng/ml. Total plasma cortisol concentrations were determined in duplicate 50-μl aliquots of unextracted plasma using the Coat-A-Count cortisol assay kit (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA), validated for use in sheep (6). Mean intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 7.1 and 9.8%, respectively (14 assays); assay sensitivity averaged 0.51 ng/ml.

Results

Experiment 1: does a type II GR agonist mimic the inhibitory action of cortisol on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH?

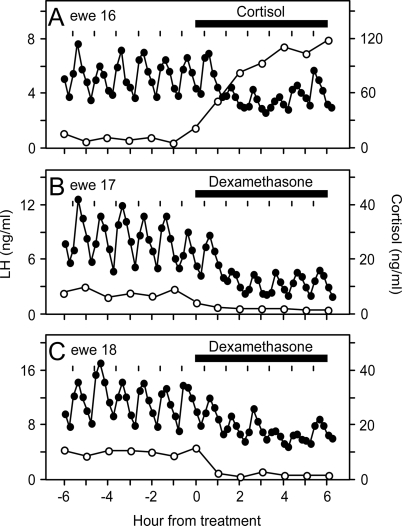

Figure 2 illustrates plasma profiles of cortisol and LH in one representative ewe that received cortisol and two representative ewes that received dexamethasone. Before treatment, cortisol was low and stable (8.1 ± 2.7 vs. 4.3 ± 0.8 ng/ml for cortisol and dexamethasone groups, respectively). Injection of cortisol every 30 min elevated plasma cortisol concentrations within 2 h to 86.6 ± 15.2 ng/ml. Injection of dexamethasone every 30 min reduced plasma cortisol to 1.4 ± 0.7 ng/ml (P < 0.001) during the 6-h treatment period, confirming dexamethasone evoked negative feedback within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via the type II GR (22,23).

Figure 2.

LH (•) and cortisol (○) responses in one representative ewe that received cortisol (A) and two representative ewes that received dexamethasone (B and C) in experiment 1. Horizontal bar depicts the 6-h period of twice-hourly sc injection of cortisol or dexamethasone. Tick marks indicate time of administration of hourly GnRH (5 ng/kg, iv) boluses to induce each LH pulse. Note, cortisol scale for ewes receiving dexamethasone is expanded to visualize the decrease in plasma cortisol concentration during treatment.

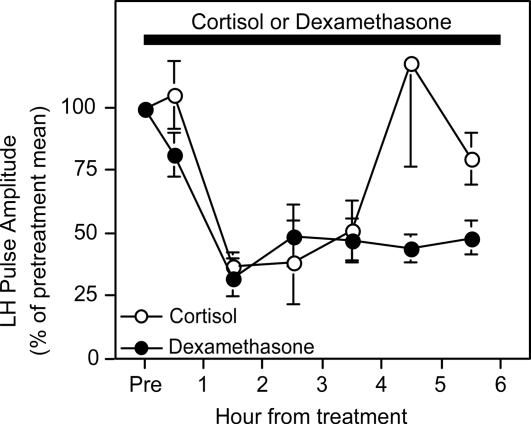

In all ewes, each exogenous GnRH bolus induced an LH pulse. No extraneous LH pulses were observed, confirming complete blockade of endogenous GnRH pulses in the pituitary clamp model. As determined previously (8,11), cortisol reduced the amplitude of GnRH-induced LH pulses (P < 0.05 before vs. during cortisol treatment). This response was evident in individual ewes (Fig. 2A) and by composite presentation expressing the amplitude of each LH pulse after treatment onset as percentage of pretreatment mean (Fig. 3). Maximal suppression to about 30% of pretreatment values occurred within 90 min. Dexamethasone also significantly suppressed the amplitude of GnRH-induced LH pulses (Figs. 2, B and C, and 3; P < 0.05). As for cortisol, maximal reduction during dexamethasone was to about 30% of pretreatment values at 90 min. Although the duration of suppression appeared to be greater in ewes receiving dexamethasone, this was not documented statistically by a significant treatment × time interaction in the rmANOVA (P > 0.1).

Figure 3.

LH pulse amplitude in response to hourly GnRH (5 ng/kg, iv) boluses during exposure to cortisol (○) or dexamethasone (•) in experiment 1. Amplitude is expressed as a ratio of each hourly LH response during cortisol or dexamethasone treatment to the pretreatment mean (±sem). Horizontal bar depicts the 6-h period of twice hourly sc injection of cortisol or dexamethasone.

Experiment 2: can cortisol act directly upon pituitary cells to inhibit responsiveness to GnRH?

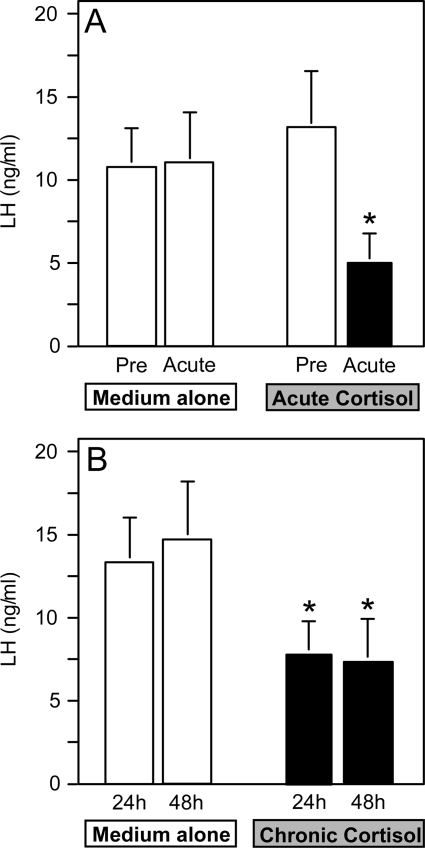

Figure 4 illustrates average LH release (over basal values) from pituitary cell cultures in response to three hourly boluses of GnRH administered during exposure to medium containing cortisol or medium alone. In cells cultured in medium alone, the magnitude of LH release did not differ between the first three and final three GnRH boluses (Fig. 4A). In contrast, exposure to cortisol during the 3-h acute period blunted the response to GnRH to approximately 30% of pretreatment values (pre vs. acute cortisol, P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). This suppression was evident by the first GnRH bolus administered 30 min after cortisol onset, illustrating the rapidity of the response to cortisol in vitro (pre vs. 0.5-h acute LH response: 13.3 ± 4.8 vs. 5.9 ± 1.5 ng/ml; P < 0.05). Chronic exposure to cortisol for either 24 or 48 h produced a similar reduction in responsiveness to the three hourly GnRH boluses (medium alone vs. 24- or 48-h chronic cortisol, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

LH release from ovine pituitary cells in response to three hourly boluses of GnRH (4 ng/ml, 10 min) in experiment 2. A, Cells were challenged with GnRH before (pre) and after (acute) exposure to medium alone or medium containing cortisol (150 ng/ml) on d 5 of culture; B, responsiveness to GnRH was tested on d 5 of culture after exposure to medium alone or 24 or 48 h chronic cortisol. Results represent the mean ± sem of four independent experiments each performed in sextuplicate. *, P < 0.05: A, pre vs. acute; B, medium alone vs. 24- or 48-h chronic cortisol.

Experiment 3: does cortisol reduce pituitary concentrations of GnRH receptor?

Part 1 (endogenous GnRH pulse model).

Plasma cortisol levels remained low and stable during the pretreatment period in all ewes and through the end of sampling in ewes receiving vehicle (overall mean, 5.0 ± 1.3 ng/ml). Twice-hourly injections of cortisol elevated plasma concentrations within 2 h to 106.5 ± 6.7 ng/ml.

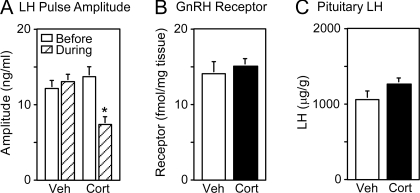

As observed previously in ovariectomized ewes (8,11) and in contrast to vehicle, cortisol reduced LH pulse amplitude by about 50% (P< 0.01; Fig. 5A). Statistical analysis also revealed inhibition of mean LH concentration but no change in pulse frequency (before vs. during cortisol, mean LH and frequency, respectively: 31.5 ± 3.9 vs. 26.7 ± 3.0 ng/ml, P < 0.01; 4.4 ± 0.3 vs. 4.4 ± 0.2 pulses/3 h, P > 0.1). In contrast to the reduction in LH pulse amplitude, concentrations of GnRH receptor protein or pituitary LH content were not significantly affected by cortisol (P > 0.1; Fig. 5, B and C, respectively).

Figure 5.

A, Mean ± sem. LH pulse amplitude in ewes before (white bars) and during (striped bars) exposure to cortisol or vehicle in experiment 3, part 1; B and C, mean ± sem GnRH receptor and pituitary LH (B and C, respectively) in ewes exposed to cortisol (black bars) or vehicle (white bars). Cortisol and vehicle were administered by twice-hourly sc injection for 3 h. *, P < 0.01, before vs. during cortisol.

Part 2 (pituitary clamp model).

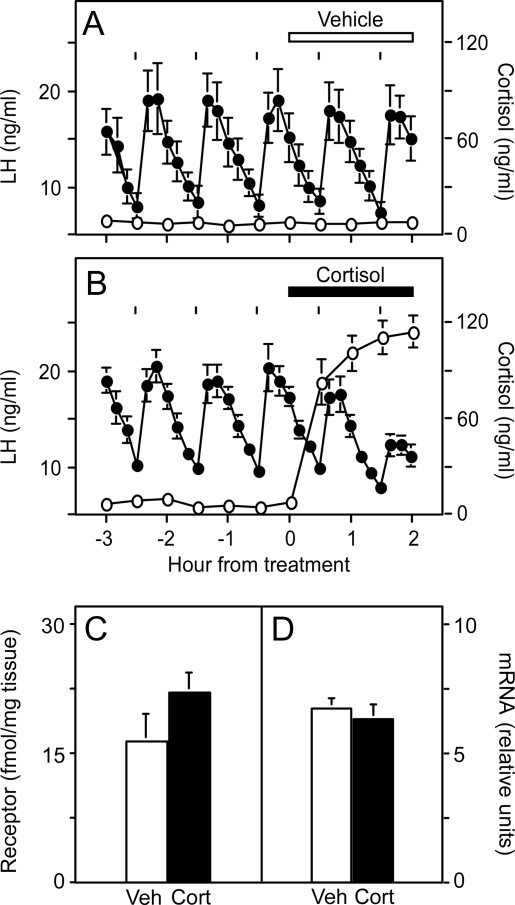

Figure 6 displays average plasma LH values during delivery of five pulses of GnRH and mean plasma cortisol concentrations in vehicle- or cortisol-treated ewes. Plasma cortisol remained less than 10 ng/ml in ewes that received vehicle and in ewes before cortisol administration (Fig. 6A); continuous infusion of cortisol elevated plasma concentrations to approximately 110 ng/ml during the final 2 h of sampling (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Mean ± sem plasma LH (•) and cortisol (○) concentration in ewes receiving a continuous 2-h infusion of vehicle (A) or cortisol (B) in experiment 3, part 2. Tick marks indicate time of administration of hourly GnRH (5 ng/kg, iv) boluses to induce each LH response. Results are mean ± sem of GnRH receptor protein (C) and GnRH receptor mRNA (D) in ewes exposed to cortisol (black bars) or vehicle (white bars). No sem indicates value is smaller than data point.

Vehicle did not alter the amplitude of the LH pulses driven by the exogenous hourly GnRH boluses (Fig. 6A). In contrast, cortisol significantly blunted responsiveness to GnRH boluses administered 30 and 90 min after cortisol onset (P < 0.05, mean suppression reached 38% at 90 min; Fig. 6B). As in part 1, this acute suppression in LH was not associated with reduced pituitary concentrations of GnRH receptor protein (Fig. 6C). Similarly, cortisol did not lower GnRH receptor mRNA (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Recent work has determined that acute psychosocial stress inhibits pituitary responsiveness to GnRH in sheep (7,24) and that the accompanying increase in cortisol, possibly acting via the type II GR, is essential for this suppression of reproductive neuroendocrine function (8). In the present study, we observed that the selective type II GR agonist, dexamethasone, mimics the inhibitory action of cortisol on pituitary responsiveness to GnRH, strengthening the evidence that this inhibitory action of cortisol is mediated via the type II GR. Furthermore, the present findings permit two novel conclusions regarding the site and cellular mechanism of cortisol action. First, the rapid action of cortisol can be expressed directly upon pituitary cells. Second, the acute reduction in pituitary responsiveness to GnRH occurs independent of changes in GnRH receptor number or gene expression. The latter finding is interesting in light of the observation that chronic cortisol reduces pituitary concentrations of GnRH receptor in sheep when administered in the presence of estradiol (10). These different findings with respect to the GnRH receptor most likely reflect the acute (present study) vs. chronic (10) exposure to cortisol rather than the presence of estradiol, because the lack of an effect of acute cortisol on GnRH receptor was observed here in both the absence and presence of estradiol (experiment 3, part 1 vs. part 2).

Although previous studies revealed direct inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on response to GnRH in primary bovine and porcine pituitary cell culture (25,26), the present study extends those observations by showing the direct action of cortisol can be elicited within a rapid time frame and that it reduces the response to pulse-like stimulation by GnRH. We observed this rapid response both in vitro and in vivo. Specifically, the inhibitory effect of cortisol in dispersed ovine pituitary cells exposed to pulse-like GnRH stimulation occurred within 30 min, and possibly earlier because this was the first time point monitored. Consistent with this response in vitro, cortisol blunted responsiveness to physiological GnRH boluses within 30 min (12% reduction) in ovariectomized sheep in which endogenous GnRH pulses were blocked. Of interest, this inhibition was enhanced (38%) during administration of the subsequent GnRH bolus that occurred 90 min after cortisol onset. This increase in suppression may reflect greater efficacy of the higher plasma cortisol concentration (∼80 ng/ml at 30 min vs. ∼110 ng/ml at 90 min) and/or the latency for maximal suppression of GnRH-induced LH release. Taken together, these results identify a rapid and direct effect of cortisol at the pituitary level and warrant further work to identify the cellular mechanism responsible for this effect.

With regard to cellular mechanisms, increasing evidence suggests the mode of cortisol action is dependent on the duration of cortisol exposure. For example, glucocorticoids reduced gonadotropin gene expression in LβT2 cells (27) and blocked the estrogen-dependent increase in GnRH receptor expression in vivo(10), but both of these effects were observed after 24–48 h. Taking into account that the suppression in responsiveness to GnRH observed here was evident within 30 min and was independent of reduced pituitary LH content and GnRH receptor number or gene expression, it seems reasonable to consider a nongenomic glucocorticoid effect. In this regard, studies in rat and pig pituitary cell cultures suggest glucocorticoids can inhibit signaling mechanisms downstream of the GnRH receptor, including protein kinase C and cAMP (28,29). Furthermore, recent evidence in a human pituitary cell line suggests glucocorticoids activate the MAPK pathway within 30 min, via a nongenomic mechanism involving the type II GR (30). The possibility of such a mechanism is particularly interesting in light of recent evidence that another steroid hormone, estradiol, can inhibit GnRH-induced LH release in ovariectomized ewes via a pathway independent of genomic action (31,32). Therefore, a fruitful area of future research will be to determine whether cortisol acts rapidly by a nongenomic mechanism to inhibit responsiveness to GnRH via the type II GR.

Finally, our finding that cortisol can act directly on anterior pituitary cells to cause rapid inhibition of responsiveness to GnRH needs to be reconciled with recent observations that this glucocorticoid failed to inhibit the response to GnRH if the pituitary is surgically disconnected from the hypothalamus of gonadectomized sheep. In the hypothalamo-pituitary-disconnect (HPD) sheep model, cortisol did not reduce the amplitude of LH pulses driven by repeated pulse-like boluses of exogenous GnRH (9). One interpretation of that finding is cortisol acts indirectly via the hypothalamus to elicit a mediator that acts on the pituitary to inhibit its response to GnRH, a mediator akin to the gonadotropin-inhibiting factor recently suggested to exist in birds and mammals (33,34,35). A second explanation is that undisturbed communication with the hypothalamus is required to maintain cells in the anterior pituitary responsive to regulatory molecules, such as cortisol. In HPD sheep treated with GnRH, activity of the gonadotrope is reinstated, but other pituitary cell types may remain compromised and unable to respond to cortisol due to the prolonged absence of other hypophysiotropic stimuli. In this regard, our finding that cortisol evokes a rapid reduction in responsiveness to GnRH in cultured ovine pituitary cells indicates cortisol can act directly at the level of the pituitary, but it does not address whether the gonadotrope is the target for this action of cortisol. The present conclusion that cortisol can act acutely at the pituitary level to inhibit responsiveness to GnRH is substantiated by recent in vivo evidence that cortisol does, in fact, inhibit GnRH-induced LH release in HPD sheep if they are also treated with estradiol (36). Collectively, these observations encourage future work to investigate pituitary cell types and mechanisms by which cortisol acts to inhibit responsiveness to GnRH.

In summary, the present studies indicate a stress-like increment in plasma cortisol can act directly upon the pituitary gland via the type II GR to elicit a rapid decrease in responsiveness to GnRH independent of changes in GnRH receptor expression. We recently determined that this action of cortisol is physiologically relevant in that it is necessary for the suppression of pituitary responsiveness to GnRH induced by psychosocial stress. We emphasize, however, that stress also activates central pathways that inhibit pulsatile GnRH secretion (3,4,37,38), and it is likely that factors other than cortisol mediate this inhibition because cortisol itself does not inhibit GnRH pulse frequency or amplitude in the ovariectomized ewe in the absence of gonadal steroids. Overall, these observations provide support for a mechanism whereby glucocorticoids contribute to the acute suppression of reproductive function during stress.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Doug Doop, Jim Lee, Gary McCalla, Chris McCrum, and Andrew Pytiak for their contribution to the completion of this study; to Drs. Heather Billings, Lique Coolen, and Robert Thompson for their help in the preparation of the manuscript; and to Drs. Audrey Seasholtz, Alan Tilbrook, and Elizabeth Young for helpful discussions regarding the design and interpretation of the present work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IOB0520597 to F.J.K.; National Institutes of Health Grants HD30773 to F.J.K., HD051360 to K.M.B.; and U.S. Department of Agriculture Grant 2005-35203-15376 to T.M.N.

Preliminary reports have appeared in the 38th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction, 2005 [Biol Reprod 72(Suppl 1):137 and 648] and the 39th Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction, 2006 [Biol Reprod 74(Suppl 1):423].

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 25, 2007

Abbreviations: GR, Glucocorticoid receptor; HPD, hypothalamo-pituitary-disconnect; rmANOVA, repeated-measures ANOVA.

References

- Ferin M 1999 Stress and the reproductive cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:1768–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson H, Smith RF 2000 What is stress, and how does it affect reproduction? Anim Reprod Sci 60–61:743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook AJ, Turner AI, Clarke IJ 2002 Stress and reproduction: central mechanisms and sex differences in non-rodent species. Stress 5:83–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Rivest S 1991 Effect of stress on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis: peripheral and central mechanisms. Biol Reprod 45:523–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook AJ, Turner AI, Clarke IJ 2000 Effects of stress on reproduction in non-rodent mammals: the role of glucocorticoids and sex differences. Rev Reprod 5:105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia DF, Bowen JM, Krasa HB, Thrun LA, Viguié C, Karsch FJ 1997 Endotoxin inhibits the reproductive neuroendocrine axis while stimulating adrenal steroids: a simultaneous view from hypophyseal portal and peripheral blood. Endocrinology 138:4273–4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Oakley AE, Pytiak AV, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Karsch FJ 2007 Does cortisol acting via the type II glucocorticoid receptor mediate suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in response to psychosocial stress? Endocrinology 148:1882–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Stackpole CA, Clarke IJ, Pytiak AV, Tilbrook AJ, Wagenmaker ER, Young EA, Karsch FJ 2004 Does the type II glucocorticoid receptor mediate cortisol-induced suppression in pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone? Endocrinology 145:2739–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackpole CA, Clarke IJ, Breen KM, Turner AI, Karsch FJ, Tilbrook AJ 2006 Sex differences in the suppressive effect of cortisol on pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone in sheep. Endocrinology 147:5921–5931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams TE, Sakurai H, Adams BM 1999 Effect of stress-like concentrations of cortisol on estradiol-dependent expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor in orchidectomized sheep. Biol Reprod 60:164–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Karsch FJ 2004 Does cortisol inhibit pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion at the hypothalamic or pituitary level? Endocrinology 145:692–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Cummins JT, Thomas GB, Clarke IJ 1987 Steroid feedback inhibition of pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ewe. Biol Reprod 36:818–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Leung KE, Convey EM 1982 Ovarian steroids modulate the self-priming effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone on bovine pituitary cells in vitro. Endocrinology 110:717–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Dahl G, Evans NP, Manning JM, Mayfield KP, Moenter SM, Foster DL 1993 Seasonal changes in gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the ewe: alteration in response to the negative feedback action of estradiol. Biol Reprod 49:1377–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus N, Breen KM, Barrell GK, Billings HJ, Brown M, Young EA, Karsch FJ 2002 Does cortisol mediate endotoxin-induced inhibition of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion? Endocrinology 143:3748–3758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion CE, Turzillo AM, Clay CM 1996 The gene encoding the ovine gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor: cloning and initial characterization. Gene 170:277–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett TM, Crowder ME, Moss GE, Duello TM 1981 GnRH-receptor interaction. V. Down-regulation of pituitary receptors for GnRH in ovariectomized ewes by infusion of homologous hormone. Biol Reprod 24:1145–1155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML 1986 Cluster analysis: a simple, versatile and robust algorithm for endocrine pulse detection. Am J Physiol 250:E486–E493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauger RL, Karsch FJ, Foster DL 1977 A new concept for control of the estrous cycle of the ewe based on the temporal relationships between luteinizing hormone, estradiol and progesterone in peripheral serum and evidence that progesterone inhibits tonic LH secretion. Endocrinology 101:807–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Midgley Jr AR, Reichert Jr LE 1968 Radioimmunologic studies with murine, ovine and porcine luteinizing hormone. In: Rosenborg E, ed. Gonadotropins. Los Altos, CA: GERON-X; 299–306 [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Reichert Jr LE, Midgley Jr AR, Nalbandov AV 1969 Radioimmunoassay for bovine and ovine luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology 84:1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MA, Kim PJ, Kalman BA, Spencer RL 2000 Dexamethasone suppression of corticosteroid secretion: evaluation of the site of action by receptor measures and functional studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 25:151–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Spencer RL, Pulera M, Kang S, McEwen BS, Stein M 1992 Adrenal steroid receptor activation in rat brain and pituitary following dexamethasone: implications for the dexamethasone suppression test. Biol Psychiatry 32:850–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackpole CA, Turner AI, Clarke IJ, Lambert GW, Tilbrook AJ 2003 Seasonal differences in the effect of isolation and restraint stress on the luteinizing hormone response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone in hypothalamopituitary disconnected, gonadectomized rams and ewes. Biol Reprod 69:1158–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PS 1987 Effect of cortisol or adrenocorticotropic hormone on luteinizing hormone secretion by pig pituitary cells in vitro. Life Sci 41:2493–2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Keech C, Convey EM 1983 Cortisol inhibits and adrenocorticotropin has no effect on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-induced release of luteinizing hormone from bovine pituitary cells in vitro. Endocrinology 112:1782–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray SM, Thackray VG, Coss D, Mellon PL 2007 Activin and glucocorticoids synergistically activate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene expression in the immortalized LβT2 gonadotrope cell line. Endocrinology 148:762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PS 1994 Modulation by cortisol of luteinizing hormone secretion from cultured porcine anterior pituitary cells: effects on secretion induced by phospholipase C, phorbol ester and cAMP. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 349:107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DE, Schwartz NB, Ringstrom SJ 1988 Dual role of glucocorticoids in regulation of pituitary content and secretion of gonadotropins. Am J Physiol 254:E595–E600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solito E, Mulla A, Morris JF, Christian HC, Flower RJ, Buckingham JC 2003 Dexamethasone induces rapid serine-phosphorylation and membrane translocation of annexin 1 in a human folliculostellate cell line via a novel nongenomic mechanism involving the glucocorticoid receptor, protein kinase C, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology 144:1164–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreguin-Arevalo JA, Nett TM 2006 A nongenomic action of estradiol as the mechanism underlying the acute suppression of secretion of luteinizing hormone in ovariectomized ewes. Biol Reprod 74:202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreguin-Arevalo JA, Nett TM 2005 A nongenomic action of 17β-estradiol as the mechanism underlying the acute suppression of secretion of luteinizing hormone. Biol Reprod 73:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui K, Saigoh E, Ukena K, Teranishi H, Fujisawa Y, Kikuchi M, Ishii S, Sharp PJ 2000 A novel avian hypothalamic peptide inhibiting gonadotropin release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 275:661–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley GE, Perfito N, Ukena K, Tsutsui K, Wingfield JC 2003 Gonadotropin-inhibitory peptide in song sparrows (Melospiza meodia) in different reproductive conditions, and in house sparrows (Passer domesticus) relative to chicken-gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Neuroendocrinol 15:794–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsfeld LJ, Mei DF, Bentley GE, Ubuka T, Mason AO, Inoue K, Ukena K, Tsutsui K, Silver R 2006 Identification and characterization of a gonadotropin-inhibitory system in the brains of mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2410–2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BN, Clarke IJ, Breen KM, Karsch FJ, Rivalland ETA, Caddy DJ, Tilbrook AJ 2007 Estradiol enables the direct pituitary actions of cortisol to suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-induced LH secretion in ovariectomized hypothalamo-pituitary disconnected (HPD) ewes during the breeding season. Biol Reprod 76(Suppl 1): 184 (Abstract 430) [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Battaglia DF, Breen KM, Debus N, Harris TG 2002 Mechanisms for ovarian cycle disruption by immune/inflammatory stress. Stress 5:101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmaker ER, Breen KM, Oakley AE, Tilbrook AJ, Karsch FJPsycho-social stress acts centrally to reduce amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulses. Program No. 732.23. 2007 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience, 2007 (online) [Google Scholar]