Abstract

Bacteriophage Xp10-encoded transcription factor p7 interacts with host Xanthomonas oryzae RNA polymerase β′ subunit and prevents both promoter recognition by the RNA polymerase holoenzyme and transcription termination by the RNA polymerase core. P7 does not bind to and has no effect on RNA polymerase from E. coli. Here, we use a combination of biochemical and genetic methods to map the p7 interaction site to within four β′ amino acids at the N-terminus of X. oryzae RNAP β′. The interaction site is located in an area that is close to the promoter spacer in the open complex and to the upstream boundary of the transcription bubble in the elongation complex, providing possible explanation as to how a small protein can affect both transcription initiation and termination by binding to the same RNA polymerase site.

Keywords: RNA polymerase, transcription antitermination, promoter recognition, transcription factor, bacteriophage

In bacteria, the regulation of activity of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RNAP), the key enzyme of transcription, is often accomplished through interactions with protein transcription factors. The RNAP core enzyme (subunit composition α2β β′ω) is catalytically proficient (i.e., it can perform transcription elongation and terminate transcription on intrinsic terminators) but cannot initiate transcription from promoters. When a σ subunit binds the core, an RNAP holoenzyme capable of specific initiation from promoters is formed.

Most bacteriophages rely on RNAP of their host bacteria for expression of their genes during the infection process. Coordinate expression of various classes of viral genes is accomplished through the action of bacteriophage-encoded transcription factors that bind to and regulate the properties of host RNAP. Bacteriophage Xp10 (1,2) infects Xanthomonas oryzae, a rice pathogen (3). A 73-amino-acid-long Xp10 protein p7 binds to and inhibits X. oryzae RNAP (4) and therefore may be responsible for the shut-off of host transcription that is known to occur during Xp10 infection (5). P7 is a novel protein, with no similarity to proteins of known functions in public databases. P7 interacts with the X. oryzae RNAP β′ subunit (4). Like the E. coli bacteriophage T7-encoded gp2 protein, another small transcription inhibitor that binds to the β ′ subunit of host RNAP (6), p7 prevents the recognition of the −10/−35 class promoters, has less effect on the recognition of the extended -10 class promoters, and has no effect on preformed promoter complexes (4). Unlike T7 gp2, whose binding has no effect on a large-scale conformational change in σ70 that occurs upon the holoenzyme formation and that increases the distance between σ70 DNA-binding domains (7), p7 significantly decreases the distance between DNA-binding domains of σ in the holoenzyme (4). This effect is likely responsible for the inhibitory effect of p7 on promoter complex formation. The most striking difference between T7 gp2 and Xp10 p7 is the ability of the latter but not the former to prevent transcription termination (4). P7 abolishes transcription termination at all intrinsic terminators tested irrespective of promoter from which transcription is initiated or of the transcribed sequence in front of the terminator. In this respect, p7 is clearly distinct from well-studied bacteriophage λ antiterminators N and Q that require specific RNA and DNA binding sites, respectively, to function (8). The antitermination activity of p7 appears to be physiologically relevant, as late transcription of Xp10 genes by host RNAP is controlled at the level of transcription antitermination (5).

Since p7 forms a 1:1 complex with RNAP (our unpublished observations), the inhibition of promoter recognition and transcription antitermination by p7 is likely to be caused by the same protein-protein interaction. Mapping of the interaction site on the RNAP molecule should help define molecular mechanisms responsible for regulatory consequences of p7 binding. However, the task is complicated due to the large size of RNAP subunits; indeed to date only a handful of RNAP-transcription factor interactions have been mapped with precision (reviewed in 9). In this report, we show that the p7 RNAP binding site is located within just four amino acids at the very N-terminus of X. oryzae β′, the first instance when an RNAP site interacting with a transcription antitermination factor has been mapped. Structural analysis allows us to put forward a testable hypothesis about molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of p7 on transcription initiation and transcription termination.

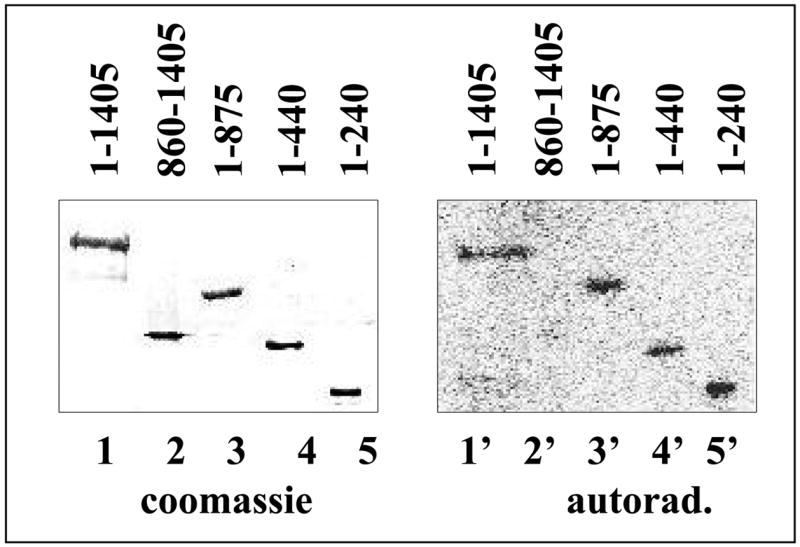

Experiments involving interspecies (X. oryzae/E. coli) RNAP hybrids demonstrated that p7 interacts with the X. oryzae RNAP β′ subunit (4). To further map the p7 interaction site, we used far-Western blotting analysis. Previously, such an approach was used to map a β′ site interacting with the RNAP σ subunit (10). P7 was genetically fused to the N-terminal heart muscle kinase (HMK) tag, radioactively labelled (phosphorylated) with HMK, and used to probe blots of SDS gels containing RNAP subunits or subunit fragments using the general conditions described in Ref. 10. Preliminary experiments indicated that neither the HMK tag nor its phosphorylation has any effect on p7 activities in in vitro transcription (data not shown). The results of initial far-Western experiments (data not shown) established that 32P-HMK-p7 interacted with X. oryzae β′ but not with X. oryzae β or E. coli β and β′, in agreement with previous results obtained using hybrid RNAPs (4). We next used recombinant X. oryzae β′ fragments to further narrow down the interaction site. The results are presented in Fig. 1. As can be seen, a C-terminal fragment containing β′ residues 860-1405 did not bind p7, while an N-terminal fragment containing residues 1-875 did (compare lanes 2′ and 3′, correspondingly). We therefore conclude that the interaction site is N-terminal to the β′ residue 875. Shorter N-terminal fragments of ββ (residues 1-440 and 1-240) also efficiently interacted with p7 (lanes 4′ and 5′, correspondingly). Thus, the far-Western analysis localizes the p7 interaction site N-terminal to X. oryzae β′ residue 240.

Figure 1. Mapping of p7 interaction site using far-Western blotting.

On the left, a coomassie-stained SDS gel showing the results of separation of indicated recombinant fragments of X. oryzae β′ is shown (lane 1 is a full-sized β′). Shown on the right are the results of far-Western blotting of a gel identical to the one shown on the left, with radioactively labelled p7.

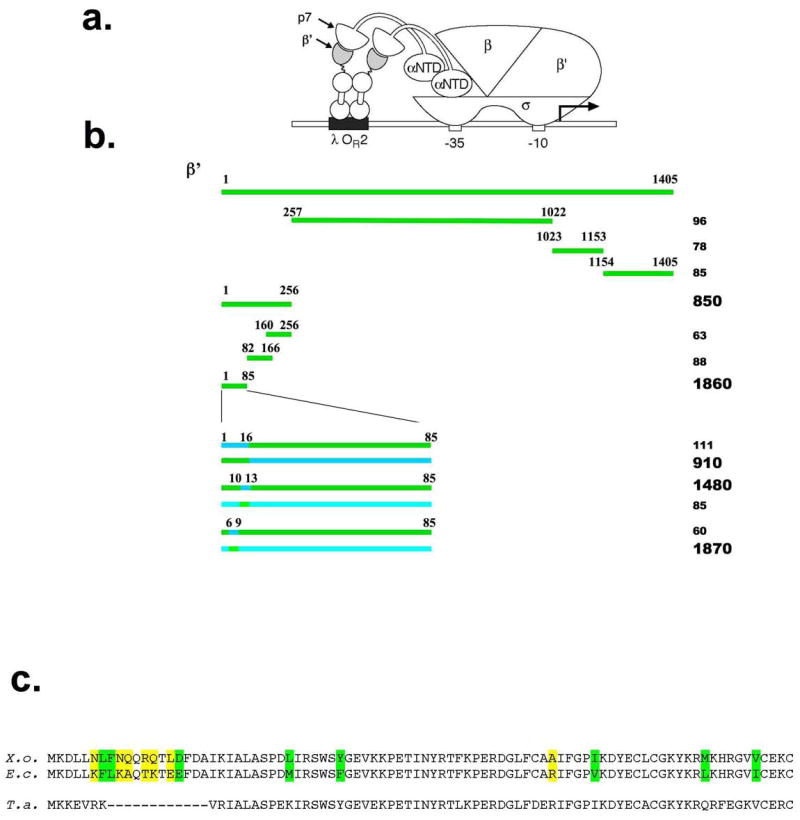

As a complementary approach, we used a bacterial two-hybrid system developed in the Hochschild laboratory (11) to map the p7 interaction. Our two-hybrid plasmids expressed full-sized p7 fused to the α subunit of E. coli RNAP and fragments of X. oryzae β′ fused to bacteriophage λ cI repressor (Fig. 2A). Cells harbouring the α–p7 fusion plasmid and a plasmid encoding cI fusion to N-terminal β′ fragment containing residues 1-256 produced high levels of β-galactosidase (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no stimulatory effect on β-galactosidase production was observed in cells harboring the α–p7 fusion plasmid and plasmids expressing cI fusions to β′ residues 257-1022, 1023-1153, or 1154-1405 (Fig. 2B). Thus, the results of two-hybrid analysis agree with far-Western analysis results. To further map the p7 interaction site, plasmids expressing fusions between λ cI repressor and various fragments of X. oryzaeβ′ contained within the N-terminal interacting fragment were created and the ability of cells carrying these plasmids to produce β-galactosidase in the presence of the α-p7 fusion plasmid was determined. In this way, the site of p7 interaction was narrowed down to β′ amino acids 1 to 85 (Fig. 2B). As expected, the corresponding fragment of E. coliβ′ did not interact with p7 in the two-hybrid assay. Comparison of the first 85 amino acids of X. oryzae β′ with the E. coli sequence revealed a total of 15 amino acid differences. Most nonconservative differences (6 out of 7) were concentrated within a stretch between amino acid positions 6-16 (Fig. 2C). To determine if this area of greatest variability between the X. oryzae and E. coliβ′ is responsible for specificity of interaction with p7, we created a two-hybrid construct encoding a chimeric fragment whose first 16 amino acids corresponded to initial amino acids of X. oryzae β′, while the rest corresponded to E. coli β′ residues 17-85 (a reciprocal construct expressing a fusion of the X. oryzae β′ fragment whose first 16 amino acids matched those of E. coli β′ was also created). The results of two-hybrid analysis showed that in the presence of the α-p7 fusion plasmid production of β-galactosidase was activated in cells harbouring the first plasmid, but not in cells harbouring the reciprocal construct, indicating that the p7 binding site is indeed located within the first 16 amino acids of β′ (Fig. 2B). More precise mapping was performed by creating two sets of chimeric β′1-85-cI two-hybrid constructs, in which X. oryzae and E. coli β′ amino acids 6-9 or 10-13 were exchanged, and testing their abilities to support β-galactosidase production in the presence of the α-p7 fusion plasmid. The results indicated that amino acids 6-9 of the X. oryzae β′ subunit were important for interaction with p7; amino acids 10-13 were not (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Mapping of p7 interaction site using bacterial two-hybrid system.

a. Replacement of the RNAP α subunit C-terminal domain by the p7 sequence permits detection of the interaction between p7 and the β′ fragment moiety of a λcI-β′ fusion protein bound to DNA upstream of a test promoter placOR2-62, which bears the λ operator OR2 centered 62 bps upstream from the transcriptional start site of the lac core promoter. The test promoter is located on the chromosome and drives the expression of a linked lacZ gene.

b. The results of analysis of interaction between the α-p7 chimera and λcI-β′ chimeras containing the indicated X. oryzae and E. coli β′ fragments are presented. E. coli cells harbouring indicated two-hybrid plasmids were grown and assayed for the β-gal activity as described in Ref. 21. The numbers at the right hand side show the β-gal activity measured in Miller units and are representative of activity values obtained in three independent experiments. Green color indicates X. oryzae β′ sequence; cyan -corresponding E. coli sequence.

c. At the top, the sequence of the first 85 amino acids of X. oryzae β′ (labelled “X.o.”) is aligned with the corresponding sequence from E. coli (“E.c.”) and Thermus aquaticus (“T.a.”). Amino acid differences between the X. oryzae and E. coli sequences are highlighted in colour; green colour indicates conservative changes, yellow - nonconservative changes.

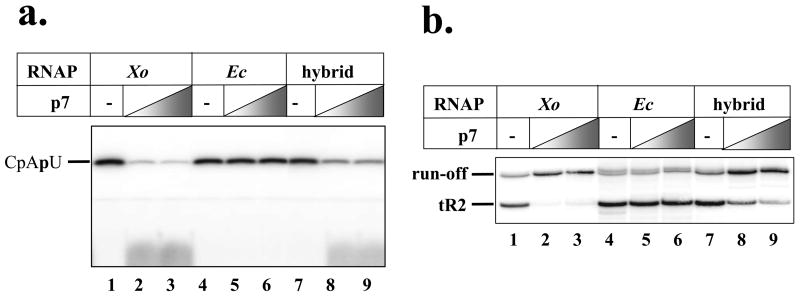

The sequence Asn6 Leu7 Phe8 Asn9 in X. oryzae is changed to an Lys6 Phe7 Leu8 Lys9 sequence in E. coli. Evidently, one (or several) of the amino acids changes between the X. oryzae and E. coli sequences is responsible for the absence of interaction of p7 with the E. coli β′ two-hybrid construct. To show that amino acids 6-9 of the X. oryzae β′ are also sufficient for p7 binding to and regulation of RNAP, we used site-specific mutagenesis of the pRL663 E. coli rpoC expression plasmid (10) to create a derivative in which rpoC codons 6–9 were changed to the corresponding codons of X. oryzae rpoC. The resultant plasmid supported the growth of the E. coli 397C rpoCts strain (12) at the restrictive temperature of 42 °C, though the colonies formed were clearly smaller than those formed by control cells harbouring pRL663 (data not shown). Thus, the mutant rpoC can be the sole source of β′ in E. coli, though the mutant RNAP appears to be somewhat defective, at least a 42 °C. Since pRL663 and its derivatives express β′ with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag, RNAP harbouring the mutant, plasmid-borne, β′ was separated from RNAP harbouring the wild-type, untagged, β′ using Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography and then purified to homogeneity (13). The ability of the mutant enzyme to respond to p7 in vitro was next determined alongside with X. oryzae (positive control) and E. coli (negative control) RNAPs. The results are shown in Fig. 3. As can be seen, and as was shown previously (4), abortive transcription initiation or transcription termination by the E. coli RNAP was unaffected by the addition of p7, while X. oryzae RNAP responded to the presence of the protein by decreased transcription initiation (Fig. 3A) and decreased transcription termination (Fig. 3B). The mutant E. coli enzyme behaved as X. oryzae RNAP (though it required higher concentrations of p7 for full inhibition of transcription initiation and termination). We therefore conclude that X. oryzae β′ amino acids 6-9 are indeed the primary determinants of specific p7 binding; other X. oryzae RNAP amino acids may increase the binding efficiency.

Figure 3. X. oryzae β′ amino acids 6-9 confer p7-senstivity to E. coli RNAP.

a. The results of in vitro abortive synthesis of the CpApU abortive transcript from the T7 A1 promoter by X. oryzae RNAP (“Xo”), E. coli RNAP (“Ec”), and an E. coli enzyme containing X. oryzae amino acids in β′ positions 6-9 (“hybrid”) in the presence or in the absence of p7 are presented.

b. The results of in vitro transcription by the indicated enzymes from a template containing the T7 A1 promoter fused to the λ tR2 terminator are presented. Transcription complexes stalled at position 20 of the template were first prepared by nucleotide deprivation, supplied, where indicated, with p7, and transcription elongation was resumed by the addition of all four NTPs.

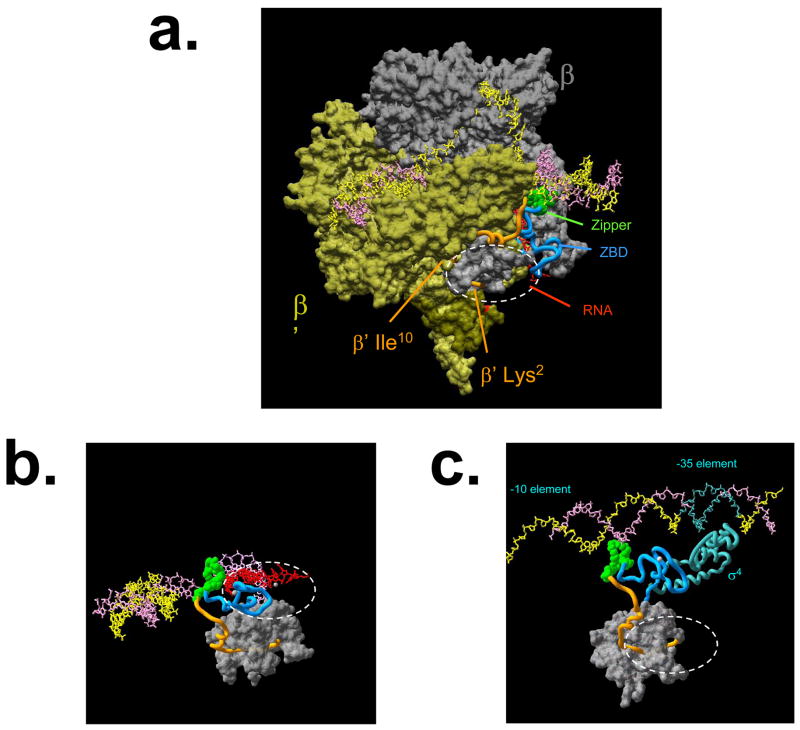

The structures of several complexes formed by RNAPs from thermophilic bacteria of the Thermus genus have recently been determined, including a medium-resolution structure of a promoter-like complex formed by T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme (14) and a high-resolution structure of an artificially assembled elongation complex formed by T. thermophilus RNAP core (15). These two structures are relevant for the understanding of the dual mechanism of p7 function as inhibitor of promoter recognition and inhibitor of transcription termination. Unfortunately, amino acids that constitute the p7 binding site are missing from Thermus RNAPs β′ subunits (Fig. 2C) (and Thermus RNAP is unaffected by p7, data not shown), making it impossible to precisely pinpoint the location of the p7 binding site on available structures. Nevertheless, the general area of p7 binding (indicated by a dashed circle in Fig. 4) can be deduced with high confidence. As can be seen, from the alignment presented in Fig. 2C, the last amino acids of T. aquaticus β′ that can be aligned to X. oryzae β′ are Val8 Arg9 Ile10 (correspond to Ile19 Lys20 Ile21 in X. oryzae β′). Of these three amino acids, only Ile10 is partially exposed on the surface (Fig. 4), while the more N-terminal amino acids are buried under portions of β and β′. Thermus β′ N-terminus and charged residues immediately after it are exposed at the surface. We assume that a 12-amino acid insertion in X. oryzae β′ that contains the p7 binding site is surface-exposed (to make the interaction possible) and forms a loop around the area where the N-terminus of Thermus β′ (around amino acids 4) emerges at the enzyme surface. On Fig. 4, the location of p7 interaction loop on the structure of transcription elongation complex formed by Thermus RNAP is indicated by a dashed oval. Though p7 is a very small protein, its structure is not known and so it is not known how far away from the binding site it can reach. With these uncertainties in mind, one can see that the site of p7 binding is quite consistent with the known biochemical effects of this protein on transcription. The site of p7 binding is close to the Zn-binding site formed by the evolutionary conserved segment A of β′ (cyan on Fig. 4) and to the β′ zipper element (green). It is also close to the exit path of the nascent RNA (Figs 4AB). Direct, or indirect (through repositioning of the N-terminal surface-exposed region of β′ indicated by orange color on the figure) effects of p7 on either of these structural elements may be responsible for the antitermination effect of p7. The Zn-binding element is in close proximity to the RNA exit channel; p7 may thus influence transcription termination by altering the Zn-binding element interactions with RNA. In this scenario, the p7 mechanism of action would be similar to transcription antitermination by the phage HK022 put element, which acts by affecting the Zn-binding element interactions with the transcript (17). The β′-zipper is located at the upstream edge of transcription bubble, where the non-template DNA strand controls transcription termination efficiency by displacing the RNA from the RNA-DNA hybrid (18). An RNAP mutant lacking the β′-zipper has decreased transcription termination efficiency (NZ, YY, and KS, in preparation). Thus, p7 may also influence transcription termination by affecting the β′-zipper.

Figure 4. Structural context of the p7 binding site.

a. A structure of the bacterial transcription elongation complex obtained by superposition of a high-resolution structure of an artificial T. thermophilus RNAP transcription elongation complex lacking upstream DNA (16) and a model of the complete transcription elongation complex formed by the T. aquaticus RNAP (15) is presented. The structure presented lacks several features, such as non-conserved domains of β′, to increase clarity. The β subunit is gray, the bulk of β′ is olive. The relevant parts of the structure are: template DNA - pink, non-template DNA - yellow, nascent transcript - red, N-terminus of β′ (amino acids 2-28) - orange ribbon, the β′ zipper domain (amino acids 29-40) - green, spacefill representation, the β′ zinc finger (amino acids 41-86) -cyan ribbon. The dashed oval indicates the position of bound p7.

b. In this view of the elongation complex, most of RNAP has been removed to make the relationships between the nascent RNA and the upstream boundary of the transcription bubble with the p7 binding site clearer.

c. The position of the p7 binding site in the open complex (after 14). Most of RNAP has been removed for clarity. The -35 promoter element and the RNAP σ subunit region 4 are indicated by cyan.

The site of p7 binding is consistent with its effects in transcription initiation, since both the β′-zipper and the Zn-binding element interact with the spacer region of the promoter (Fig. 4C). Binding of p7 in the vicinity of these structural elements may affect these interactions and thus weaken or abolish promoter utilization. In line with this hypothesis we showed that deletion of β′-zipper weakens or even abolishes the recognition of certain bacterial promoters (NZ, YY, and KS, in preparation).

Biophysical data show that in the holoenzyme, the distance between σ regions 2 and 4 changes upon the binding of p7 binding (4). The p7 binding site is close enough to σ region 4 to indirectly influence its interactions with the -35 promoter consensus element by changing the position of neighboring structural elements of β′. A similar indirect mechanism of promoter-specific inhibition of transcription initiation was proposed for bacteriophage T4 antisigma AsiA (19).

As is also the case with gp2, another phage-encoded inhibitor that interacts with the β′ subunit of host RNAP, the interaction site is formed by non-essential amino acids that are highly variable in evolution and differ even between RNAPs from closely related species. The fact that host bacteria maintain these amino acids, which are required for development of lytic phages (and therefore killing of the host) but not for host viability, is rather surprising. Though Xanthomonas phages closely related to Xp10 (and, therefore, encoding p7-like proteins) may be quite common (20), the evolutionary pressure from such phages on their host apparently is not large enough to offset the loss of fitness caused by mutations in the target RNAP site. While the reason of decreased viability exhibited by E. coli cells with β′ harbouring substitutions in residues that constitute the p7 binding site (as revealed by in experiments involving E. coli 397C tester strain, above) is not known, it is tempting to speculate that cellular termination/antitermination factors may also interact with this area of RNAP. Be that as it may, the availability of a mutant E. coli RNAP that is sensitive to p7 opens the way for mechanistic analysis of this novel transcription factor using the highly sophisticated assays that have been developed in recent years.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH GM grant R01 59295, Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium program in Molecular and Cellular Biology new groups grant, and Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in Biomedical Sciences to (KS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kuo TT, Huang T, Wu R, Yang C. Characterization of three bacteriophages of Xanthomonas oryzae. Dawson Bot Bull Acad Sinica. 1967;8:246–257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuzenkova Y, Nechaev S, Berlin J, Rogulja D, Kuznedelov K, Schloss M, Inman R, Mushegian R, Severinov K. Genome of Xanthomonas oryzae bacteriophage Xp10: an odd T-odd phage. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:735–748. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White FF, Chittoor JM, Leach JE, Young SA, Zhu W. Molecular analysis of the interaction between Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and rice. Rice Genetics III; Proc. Int. Rice Genet. Symp., 3rd; IRRI, Manila, Philippines. 1995. pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nechaev S, Yuzenkova Y, Niedziela-Majka A, Heyduk T, Severinov K. A novel bacteriophage-encoded RNA polymerase binding protein inhibits transcription initiation and abolishes transcription termination by host RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:11–22. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenova E, Djordjevic M, Shraiman B, Severinov K. The tale of two polymerases: Transcription profiling and gene expression strategy of bacteriophage Xp10. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:764–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nechaev S, Severinov K. Inhibition of E. coli RNA polymerase by bacteriophage T7 gene 2 protein. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:815–826. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuznedelov K, Minakhin L, Niedziela-Majka A, Dove SL, Rogulja D, Nickels BE, Hochschild A, Heyduk T, Severinov K. The RNA polymerase core flap domain triggers conformational switch in the σ subunit to allow promoter recognition. Science. 2002;295:855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1066303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts JW, Yarnell W, Bartlett E, Guo J, Marr M, Ko DC, Sun H, Roberts CW. Antitermination by bacteriophage lambda Q protein. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:319–325. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nechaev S, Severinov K. Bacteriophage-induced modifications of host RNA polymerase. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:301–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur TM, Burgess RR. Localization of a sigma 70 binding site on the N terminus of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase beta′ subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31381–31387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dove SL, Joung JK, Hochschild A. Activation of prokaryotic transcription through arbitrary protein-protein contacts. Nature. 1997;386:627–630. doi: 10.1038/386627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nedea EC, Markov D, Naryshkina T, Severinov K. Localization of E. coli rpoC mutations that affect RNA polymerase assembly and activity at high temperature. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2663–2665. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2663-2665.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashlev M, Nudler E, Severinov K, Borukhov S, Komissarova N, Goldfarb A. Histidine-tagged RNA polymerase of Escherichia coli and transcription in solid phase. Methods Enzymol. 1996;274:326–334. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science. 2002;296:1285–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1069595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassylyev DG, Vassylyeva MN, Perederina A, Tahirov TH, Artsimovitch I. Structural basis for transcription elongation by bacterial RNA polymerase. Nature. 2007;448:157–162. doi: 10.1038/nature05932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korzheva N, Mustaev A, Kozlov M, Malhotra A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Darst SA. A structural model of transcription elongation. Science. 2000;289:619–625. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King R, Markov D, Severinov K, Weisberg RA. A universally conserved zinc binding site in the largest subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase modulates transcription termination and antitermination but does not stabilize the elongation complex. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:1143–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JS, Roberts JW. Role of DNA bubble rewinding in enzymatic transcription termination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4870–4875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600145103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory B, Nickels BE, Garrity S, Severinova E, Minakhin L, Bieber Urbauer RJ, Urbauer JL, Heyduk T, Severinov K, Hochschild A. A regulator that inhibits transcription by targeting an intersubunit interaction of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4554–4559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400923101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CN, Lin JW, Chow TY, Tseng YH, Weng SF. A novel lysozyme from Xanthomonas oryzae phage varphiXo411 active against Xanthomonas and Stenotrophomonas. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;50:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dove SL, Hochschild A. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on transcription activation. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:231–46. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]